Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Wrestling is a proving ground. In an ultimate test of will and endurance, the wrestler first battles himself and then his opponent until one is left standing with arms raised overhead in victory. In a life filled with mettle-testing experiences both inside and outside athletics, Don Benning has made the sport he became identified with a personal metaphor for grappling with the challenges a proud, strong black man like himself faces in a racially intolerant society.

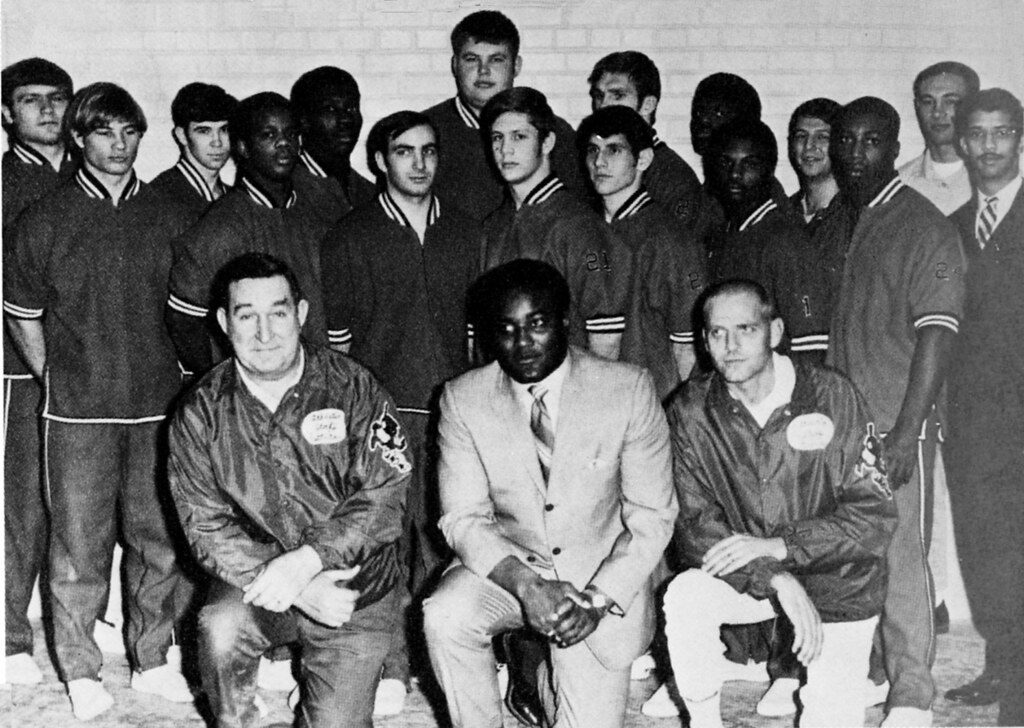

A multi-sport athlete at North High School and then-Omaha University (now UNO), the inscrutable Benning brought the same confidence and discipline he displayed as a competitor on the mat and the field to his short but legendary coaching tenure at UNO and he’s applied those same qualities to his 42-year education career, most of it spent with the Omaha Public Schools. Along the way, this man of iron and integrity, who at 68 is as solid as his bedrock principles, made history.

At UNO, he forged new ground as America’s first black head coach of a major team sport at a mostly white university. He guided his 1969-70 squad to a national NAIA team championship, perhaps the first major team title won by a Nebraska college or university. His indomitable will led a diverse mix of student-athletes to success while his strong character steered them, in the face of racism, to a higher ground.

When, in 1963, UNO president Milo Bail gave the 26-year-old Benning, then a graduate fellow, the chance to he took the reins over the school’s fledgling wrestling program, the rookie coach knew full well he would be closely watched.

“Because of the uniqueness of the situation and the circumstances,” he said, “I knew if I failed I was not going to be judged by being Don Benning, it was going to be because I was African-American.”

Besides serving as head wrestling coach and as an assistant football staffer, he was hired as the school’s first full-time black faculty member, which in itself was enough to shake the rafters at the staid institution.

“Those old stereotypes were out there — Why give African-Americans a chance when they don’t really have the ability to achieve in higher education? I was very aware those pressures were on me,” he said, “and given those challenges I could not perform in an average manner — I had to perform at the highest level to pass all the scrutiny I would be having in a very visible situation.”

Benning’s life prepared him for proving himself and dealing with adversity.

“The fact of the matter is,” he said, “minorities have more difficult roads to travel to achieve the American Dream than the majority in our society. We’ve never experienced a level playing field. It’s always been crooked, up hill, down hill. To progress forward and to reach one’s best you have to know what the barriers or pitfalls are and how to navigate them. That adds to the difficulty of reaping the full benefits of our society but the absolute key is recognizing that and saying, ‘I’m not going to allow that to deter me from getting where I want to get.’ That was already a motivating factor for me from the day I got the job. I knew good enough wasn’t good enough — that I had to be better.”

Shortly after assuming his UNO posts his Pullman Porter father and domestic worker mother died only weeks apart. He dealt with those losses with his usual stoicism. As he likes to say, “Adversity makes you stronger.”

Toughing it out and never giving an inch has been a way of life for Benning since growing up the youngest of five siblings in the poor, working-class 16th and Fort Street area. He said, “Being the only black family in a predominantly white northeast Omaha neighborhood — where kids said nigger this or that or the other — it translated into a lot of fights, and I used to do that daily. In most cases we were friends…but if you said THAT word, well, that just meant we gotta fight.”

Despite their scant formal education, he said his parents taught him “some valuable lessons scholars aren’t able to teach.” Times were hard. Money and possessions, scarce. Then, as Benning began to shine in the classroom and on the field (he starred in football, wrestling and baseball), he saw a way out of the ghetto. Between his work at Kellom Community Center, where he later coached, and his growing academic-athletic success, Benning blossomed.

“It got me more involved, it expanded my horizons and it made me realize there were other things I wanted,” he said.

But even after earning high grades and all-city athletic honors, he still found doors closed to him. In grade school, a teacher informed him the color of his skin was enough to deny him a service club award for academic achievement. Despite his athletic prowess Nebraska and other major colleges spurned him.

At UNO, where he was an oft-injured football player and unbeaten senior wrestler, he languished on the scrubs until “knocking the snot” out of a star gridder in practice, prompting a belated promotion to the varsity. For a road game versus New Mexico A&M he and two black mates had to stay in a blighted area of El Paso, Texas — due to segregation laws in host Las Cruces, NM — while the rest of the squad stayed in plush El Paso quarters. Terming the incident “dehumanizing,” an irate Benning said his coaches “didn’t seem to fight on our behalf while we were asked to give everything for the team and the university.”

Upon earning his secondary education degree from UNO in 1958 he was dismayed to find OPS refusing blacks. He was set to leave for Chicago when Bail surprised him with a graduate fellowship (1959 to 1961). After working at the North Branch YMCA from ‘61 to ‘63, he rejoined UNO full-time. Still, he met racism when whites automatically assumed he was a student or manager, rather than a coach, even though his suit-and-tie and no-nonsense manner should have been dead giveaways. It was all part of being black in America.

To those who know the sanguine, seemingly unflappable Benning, it may be hard to believe he ever wrestled with doubts, but he did.

“I really had to have, and I didn’t know if I had it at that particular time, a maturity level to deal with these issues that belied my chronological age.”

Before being named UNO’s head coach, he’d only been a youth coach and grad assistant. Plus, he felt the enormous symbolic weight attending the historic spot he found himself in.

“You have to understand in the early 1960s, when I was first in these positions, there wasn’t a push nationally for diversity or participation in society,” he said. “The push for change came in 1964 with the Civil Rights Act, when organizations were forced to look at things differently. As conservative a community as Omaha was and still is it made my hiring more unusual. I was on the fast track…

“On the academic side or the athletic side, the bottom line was I had to get the job done. I was walking in water that hadn’t been walked in before. I could not afford not to be successful. Being black and young, there was tremendous pressure…not to mention the fact I needed to win.”

Win his teams did. In eight seasons at the helm Benning’s UNO wrestling teams compiled an 87-24-4 dual mark, including a dominating 55-3-2 record his last four years. Competing at the NAIA level, UNO won one national team title and finished second twice and third once, crowning several individual national champions. But what really set UNO apart is that it more than held its own with bigger schools, once even routing the University of Iowa in its own tournament. Soon, the Indians, as UNO was nicknamed, became known as such a tough draw that big-name programs avoided matching them, less they get embarrassed by the small school.

The real story behind the wrestling dynasty Benning built is that he did it amid the 1960s social revolution and despite meager resources on campus and hostile receptions away from home. Benning used the bad training facilities at UNO and the booing his teams got on the road as motivational points.

His diverse teams reflected the times in that they were comprised, like the ranks of Vietnam War draftees, of poor white, black and Hispanic kids. Most of the white athletes, like Bernie Hospodka, had little or no contact with blacks before joining the squad. The African-American athletes, empowered by the Black Power movement, educated their white teammates to inequality. Along the way, things happened — such as slights and slurs directed at Benning and his black athletes, including a dummy of UNO wrestler Mel Washington hung in effigy in North Carolina — that forged a common bond among this disparate group of men committed to making diversity work in the pressure-cooker arena of competition.

“We went through a lot of difficult times and into a lot of hostile environments together and Don was the perfect guy for the situation,” said Hospodka, the 1970 NAIA titlist at 190 pounds. “He was always controlled, always dignified, always right, but he always got his point across. He’s the most mentally tough person you’d ever want to meet. He’s one of a kind. We’re all grateful we got to wrestle for Don. He pushed us very hard. He made us all better. We would go to war with him anytime.”

Brothers Roy and Mel Washington, winners of five individual national titles, said Benning was a demanding “disciplinarian” whom, Mel said, “made champions not only on the mat but out there in the public eye, too. He was more than a coach, he was a role model, a brother, a father figure.” Curlee Alexander, 115-pound NAIA titlist in 1969 and a wildly successful Omaha prep wrestling coach, said the more naysayers “expected Don to fail, the more determined he was to excel. By his look, you could just tell he meant business. He had that kind of presence about him.”

Away from the mat, the white and black athletes may have gone their separate ways but where wrestling was concerned they were brothers rallying around their perceived identity as outcasts from the poor little school with the black coach.

“It’s tough enough to develop a team to such a high skill level that they win a national championship if you have no other factors in the equation,” Benning said, “but if you have in the equation prejudice and discrimination that you and the team have to face then that makes it even more difficult. But those things turned into a rallying point for the team.

“The white and black athletes came to understand they had more commonalities than differences. It was a sociological lesson for everyone. The key was how to get the athletes to share a common vision and goal. We were able to do that. The athletes that wrestled for me are still friends today. They learned about relationships and what the real important values are in life.”

His wrestlers still have the highest regard for him and what they shared.

“I don’t think I could have done what I did with anyone else,” Hospodka said. “Because of the things we went through together I’m convinced I’m a better human being. There’s a bond there I will never forget.” Mel Washington said, “I can’t tell you how much this man has done for me. I call him the legend.” The late Roy Washington, who changed his name to Dhafir Muhammad, said, “I still call coach for advice.” Alexander credits Benning with keeping him in school and inspiring his own coaching/teaching path.

After establishing himself as a leader Benning was courted by big-time schools to head their wrestling and football programs. Instead, he left the profession in 1971, at age 34, to pursue an educational administration career. Why leave coaching so young? Family and service. At the time he and wife Marcidene had begun a family — today they are parents to five grown children and two grandkids — and when coaching duties caused him to miss a daughter’s birthday, he began having second thoughts about the 24/7 grind athletics demands.

Besides, he said, he was driven to address “the inequities that existed in the school system. I thought I could make a difference in changing policies and perhaps making things better for all students, specifically minority students. My ultimate goal was to be superintendent.”

Working to affect change from within, Benning feels he “changed attitudes” by showing how “excellence could be achieved through diversity.” During his OPS tenure, he operated, just like at Omaha University, “in a fish bowl.” Making his situation precarious was the fact he straddled two worlds — the majority culture that viewed him variously as a token or a threat and the minority culture that saw him as a beacon of hope.

But even among the black community, Benning said, there was a militant segment that distrusted one of their own working for The Man.

“You really weren’t looked upon too kindly if you were viewed as part of the system,” he said. “On the other side of it, working in an overwhelmingly majority white situation presented its own particular set of challenges.”

What got him through it all was his own core faith in himself. “Evidently, some people would say I’m a confident individual. A few might say I’m arrogant. I would say I’m highly confident. I can’t overemphasize the fact you have to have a strong belief in self and you also have to realize that a lot of times a leader has to stand alone. There are issues and problems that set him or her apart from the crowd and you can’t hide from it. You either handle it or you fail and you’re out.”

Benning handled it with such aplomb that he: brought UNO to national prominence, laying the foundation for its four-decade run of excellence on the mat; became a distinguished assistant professor; and built an impressive resume as an OPS administrator, first as assistant principal at Central High School, then as director of the Department of Human-Community Relations and finally as assistant superintendent.

During his 26-year OPS career he spearheaded Omaha’s smooth desegregation plan, formed the nationally recognized Adopt-a-School business partnership and advocated for greater racial equity within the schools through such initiatives as the Minority Intern Program and the Pacesetter Academy, an after school program for at-risk kids. Driving him was the responsibility he felt to himself, and by extension, fellow blacks, to maximize his and others’ abilities.

“I had a vision and a mission for myself and I set about developing a plan so I could reach my goal, and that was basically to be the best I could be. As a coach and educator what I have really enjoyed is helping people grow and reach their potential to be the best they can be. That’s my goal, that’s my mission, and I try to hold to it.”

His OPS career ended prematurely when, in 1997, he retired after being snubbed for the district’s superintendency and being asked by current schools CEO John Mackiel to reapply for the assistant superintendent’s post he’d held since 1979. Benning called it “an affront” to his exemplary record and longtime service.

About his decision to leave OPS, he said, “I could have continued as assistant superintendent, but I chose not to because who I am and what I am is not negotiable.” A critic of neighborhood schools, he did not bend on a practice he deems detrimental to the quality of education for minorities. “I compromised on a lot of things but not on those issues. The thing I’ve tried not to do, and I don’t think I have, is negotiate away my integrity, my beliefs, my values.”

Sticking to his guns has exacted a toll. “I’ve battled against the odds all my life to achieve the successes I have and there’s been some huge prices to pay for those successes.”

Curlee Alexander

His unwavering stances have sometimes made him an unpopular figure. His staunch loyalty to his hometown has meant turning down offers to coach and run school districts elsewhere. His refusal to undermine his principles has found him traveling a hard, bitter, lonely road, but it’s a path whose direction is true to his heart.

“I found out long ago there were things I would do that didn’t please every one and in those types of experiences I had to kind of stand alone or submit. I developed a strong inner being where I somewhat turned inward for strength. I kind of said to myself, I just want to do what I know to be right and if people don’t like it, well, that’s the way it is. I was ready to deal with the consequences. That’s the personality I developed from a very young age.”

Those who’ve worked with Benning see a man of character and conviction. Former OPS superintendent Norbert Schuerman described him as “proud, determined, disciplined, opinionated, committed, confident, political,” adding, “Don kept himself very well informed on major issues and because he was not bashful in expressing his views, he was very helpful in sensitizing others to race relations. His integrity and his standing in the community helped minimize possible major conflicts.”

OPS Program Director Kenneth Butts said, “He’s a very principled man. He’s very demanding. He’s very much about doing what is right rather than what is politically expedient. He cares. He’s all about equity and folks being treated fairly.”

After the flap with OPS Benning left the job on his own terms rather than play the stooge, saying, “The Omaha Public Schools situation was a major disappointment to me…To use a boxing analogy, it staggered me, but it didn’t knock me down and it didn’t knock me out. Having been an athlete and a coach and won and lost a whole lot in my life I would be hypocritical if I let disappointment in life defeat me and to change who I am. I quickly moved on.”

Indeed, the same year he left OPS he joined the faculty at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he is coordinator of urban education and senior lecturer in educational administration in its Teachers College. In his current position he helps prepare a new generation of educators to deal with the needs of an ever more diverse school and community population.

Even with the progress he’s seen blacks make, he’s acutely aware of how far America has to go in healing its racial divide.

“This still isn’t a color-blind society. I don’t say that bitterly — that’s just a fact of life. But until we resolve the race issue, it will not allow us to be the best we can be as individuals and as a country,” he said.

As his own trailblazing cross-cultural path has proven, the American ideal of epluribus unum — “out of many, one” — can be realized. He’s shown the way.

“As far as being a pioneer, I never set out to be a part of history. I feel very privileged and honored having accomplished things no one else had accomplished. So, I can’t help but feel that maybe I’ve made a difference in some people’s lives and helped foster inclusiveness in our society rather than exclusiveness. Hopefully, I haven’t given up the notion I still can be a positive force in trying to make things better.”

Related Articles

- Coaching diversity slowly rising at FBS schools (thegrio.com)

- University regents approve Nebraska-Omaha’s D-I move (sports.espn.go.com)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Tremendous things here. I am very satisfied to peer your post.

Thanks a lot and I’m looking ahead to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

LikeLike

Excellent blog you have got here.. It’s difficult to find good quality writing like yours nowadays. I seriously appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

LikeLike

Spot on with this write-up, I really believe this website needs much more

attention. I’ll probably be back again to read through more, thanks for the information!

LikeLike

Hi, every time i used to check blog posts here early in the morning, since i enjoy to learn more and more.

LikeLike