Archive

Kindred spirits Giamatti and Payne to revisit the triumph of ‘Sideways’ and the art of finding truth and profundity in the holy ordinary

Kindred spirits Giamatti and Payne to revisit the triumph of ‘Sideways’ and the art of finding truth and profundity in the holy ordinary

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the August 2019 edition of The Reader (thereader.com)

Go-to character actor Paul Giamatti brings élan to his screen gallery of nerdy sidekicks and beleaguered Everyman types. It’s rare for someone with his hangdog looks to be a romantic interest. But in Alexander Payne’s Sideways (2004), he melts hearts with earnest desire and neurotic angst as lovelorn Miles.

He’s the sad half of a dysfunctional buddy team with Jack (Thomas Haden Church), whose frivolity masks hurt. Their on-the-road odyssey of regret, self-pity and debauchery is tempered by redeeming love. The Indiewood project surprised its makers by becoming a serious box office success and major awards contender.

Payne’s taking time from trying to get a new feature off the ground to join Giamatti for an August 25 public conversation accented by clips. This eighth iteration of the Film Streams Feature Event fundraiser unspools in the Holland Performing Arts Center at 7 p.m.

Sideways, celebrating its 15th anniversary, remains a highlight of the two men’s respective careers.

“It was a gorgeous experience,” Giamatti said by phone. “It was so much fun. It was joyous. And I think the movie feels that way because we were just making a movie for the love of making a movie – and that’s what was great about it. None of us felt we were making anything anybody would even care about that much. We cared about it. So much of that came from Alexander and his simple joy of being with actors and crew.”

By Sideways, each was a name with an identity – Giamatti’s animated sad-sack persona and Payne’s down-but-not-out milieu of misfits and searchers – that meshed well.

These cinema kindred spirits with a gift for understated wit that segues into broad comedy or high drama found themselves at parallel points in their artistic lives.

Giamatti hit his stride as a supporting player in the late-1990s. Payne made some waves with his debut feature, Citizen Ruth (1996), before fully getting on critics’ radar with Election, a 1999 cult classic enjoying retrospective adulation 20 years later. It’s the film that first brought Payne to Giamatti’s attention.

In Sideways Giamatti believably goes to the dark side of longing. Where childlike Jack is all about immediate gratification, reflective Miles broods over losses and Giamatti digs deep to mine this despair.

Giamatii and Church first met in-person on location in Santa Barbara wine country – after breaking the ice on the phone – where they had several days to bond before production began.

“I cast each independently,” Payne said. “But to have them develop some chemistry – because if no one believes the friendship between those two unlikely men then the film would not work – I had them come to location for two weeks before shooting, so we could rehearse together. But, more important, so they could hang out to play golf, see a movie, eat together. And they did.”

In the film the characters get involved with women they betray. Vain Jack, a former soap star, cheats on his bride-to-be with free-spirit Stephanie (Sandra Oh), who doesn’t know he’s engaged. Nebbish Miles, a teacher and writer reeling from a failed marriage and a book not finding a publisher, discovers in sensitive Maya (Virginia Madsen) a love he didn’t think possible anymore.

Church nails the self-absorbed miscreant Jack. Giamatti is dead-on as the yearning, naysaying Miles who wears his funk like a cloak. But, as Giamatti said, it is Miles who “opens up as a person through the movie in a really lovely, believable way.” Payne intuitively gives Giamatti the camera and the actor’s highly praised performance moves one to tears and laughter.

Giamatti’s work in Sideways established him as a character lead who can carry a film.

Producer Michael London brokered a package deal for the project. He optioned the film rights for the Rex Pickett novel. Payne and Jim Taylor wrote the script on spec. John Jackson cast for fit, not box-office .”Then,” Payne said, “we approached the studios and said. ‘Here is the screenplay, the director, the cast, and the budget – in or out?’ A couple studios said, ‘Why can’t you have bigger stars?’ Fox Searchlight rolled the dice and won.”

Giamatti is grateful Payne didn’t budge.

“He went back to the studio to tell them he wanted me and I think he anticipated he’d get a fight about that and he did get fights. But he stuck by it – me and Tom and Virginia and Sandra. These are the people he wanted.”

The ensemble made magic.

“Fifteen years later that movie is present in people’s minds as if it just came out last year,” Giamatti said. “It’s got amazing power.”

It marked a peak for Giamatti.

“I felt like if I couldn’t act again for some reason, my acting life would have been fulfilled having done this movie because it was such a purely pleasurable experience. Alexander’s a true filmmaker and that’s what makes him special.”

Payne’s admiration of Giamatti, whom he calls “my favorite actor,” runs deep.

“He’s just the perfect actor. He knows all of his dialogue backwards and forwards and can do it any which way – each take truthful, each take different. He could make bad dialogue work. When he read for me, I remember thinking he was the very first actor reading the lines almost exactly how I’d heard them in my head while writing them — and better.”

“He’s just a lovely guy and extremely well-read.”

Giamatti gushes over Payne’s directing methodology..

“He has the exceptional skill of being able to talk to each actor the way they need to be talked to,” he said. “Everybody has different needs or approaches and he is an incredibly sensitive human being to know what each person needs to get out of them what he wants.

“He’s a benevolent dictator as well. He’s in complete and utter control of everything going on, but you’d never know it he’s such a sweet and laid-back guy on the set.”

Then there’s the way Payne engages others.

“What I feel made a huge difference and sets him apart from any other director I’ve worked with,” Giamatti said, “is his choice to not use a video monitor during takes.”

Both men dislike the isolation of actors and crew working in one area while director, cinematographer and producers huddle around a video assist in another area.

Giamatti said Payne “doesn’t have a hierarchal way of thinking.” Thus, everyone’s “on the same playing field.” “To him, everybody is important, everybody’s a part of the experience. It’s unique. But that’s him.”

It helps, Giamatti said, that Payne “likes actors.”

“I can tell you the experience of being directed by him is amazing because he’s there with you. There’s a lot of stuff where I’m alone in a room in that movie. He would stand there, watch me, and talk to me. The connection I developed with him I’ve never experienced again with a film director. As great as a lot of the people I’ve worked with are, nobody’s ever done anything like that.

“The connection you feel because of that is unbelievable. I love him, I really do.”

The actor’s eager to visit Payne’s home turf and muse.

“Indeed, yeah, I’m very curious to see Omaha and how it has informed Alexander and vice versa.”

Payne may just wing it with him here, saying, “We get along so well, I may not prepare that much. We could go out on stage and just start talking.”

Surprisingly, Sideways is the only time they’ve worked together. They nearly re-teamed in 2008 when Payne first tried setting up Downsizing. He cast Giamatti as the lead, Paul. But the free-fall economic recession put the high-concept comedy on hold. By the time Payne sought financing again the suits insisted on a marquee name to hedge their big-budget risk. Enter Matt Damon.

This Omaha reunion will not be the last time the actor and director collaborate if they have their way.

“I wish we could find an opportunity to work again,” Giamatti said.

“We definitely will,” said Payne, who has a script and part in mind for him.

“I know there is something. but I fear it may not work out. It’s all timing,” Giamatti said, sounding just like Miles.

Film Streams is screening a repertory series of Giamatti’s feature work at the Dundee Theater. On August 26 and 28 Sideways shows at the north downtown Ruth Sokolof Theater. There’s also a second repertory series of favorite Giamatti films not his own.

Visit filmstreams.org for schedules and tickets.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

Metro class series features guest filmmakers and their films

Metro class series features guest filmmakers and their films

OMAHA, NE––If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to watch a film with its maker, then a summer Metropolitan Community College class series is your ticket to that cinema insider experience.

Filmmakers and Their Films is the name of the six-class series running weekly on Saturdays from June 15 through July 20 at MCC’s North Express in the Highlander Accelerator Building.

The non-credit adult Continuing Education class, which meets from 1 to 4 p.m., is taught by Omaha film author-journalist-blogger Leo Adam Biga (“Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”). Biga has secured guest appearances by at least one Oscar-winner in retired film editor Mike Hill and a mix of narrative and documentary filmmakers. All are Nebraskans.

A work by each guest will be screened followed by a moderated discussion with the maker. Students will have the opportunity to ask questions.

The Filmmakers and Their Films schedule:

June 15

Mike Hill

“Rush”

Oscar-winning editor Mike Hill worked in Hollywood for many decades as one of two primary cutters on Ron Howard’s feature films. Hill shared the Academy Award for his work on “Apollo 13.” The now retired Hill will discuss his career and specifically his work on Howard’s 2013 Formula One race car drama, “Rush.”

June 22

Lew Hunter & Lonnie Senstock

“Once in a Lew Moon”

Lew Hunter was a network television executive who wrote and produced landmark TV movies. His book about screenwriting became a bible to aspiring scenarists. A UCLA class he taught included future filmmakers. Lonnie Senstock’s documentary captures hLew’s bigger-than-life personality and appetite for life.

June 29

Mele Mason

“I Dream of an Omaha Where”

Documentary and network news photographer Mele Mason travels the nation and world for her work. She also trains her eye locally, “I Dream of an Omaha Where” follows the collaboration between performance artist Daniel Beaty and Omaha families affected by gun violence in the creation of an original work of theater.

July 6

Nebraska Filmmakers Showcase

Sample the screen work of Nik Fackler, Omowale Akintunde, John Beasley, Camille Steed, Mauro Fiore, Tim Christian and other Nebraskans who make films. Some of these professionals will be on hand to discuss their work in front of the camera or behind the camera. Camille Steed will share her documentary “A Street of Dreams” about Omaha’s North 24th Street and Vikki White will share two of her short films.

July 13

Jim Fields

“Preserve Me a Seat”

During efforts to save the Indian Hills Theatre, Jim Fields documented the passion of historic preservationists, film industry professionals and movie fans. He then expanded the story to document similar efforts around the nation that turn into classic clashes between grassroots groups and big business interests.

July 20

Brigitte Timmerman

“The Omaha Speaking”

The few fluent speakers left in the Omaha Tribe are featured in this audience favorite documentary at film festivals, Brigitte Timmerman presents the urgency that fluent speakers and educators have in preserving and passing on this rich cultural legacy before it’s too late.

urprise film guests can be expected.

The registration fee is $10 per class or $60 for the entire series. Register at: https://coned.mccneb.edu/wconnect/ace/CourseStatus.awp?&course=19JUCOMM201A.

The class meets in Suite 306 of.Metro’s North Express at the Highlander Accelerator, 2112 North 30th Street, in North Omaha.

Local Black Filmmakers Showcase: Next up – short films by Jason Fischer on Tuesday, March 5 at 6 p.m.

Local Black Filmmakers Showcase

A February-March 2019 film festival @ College of Saint Mary, 7000 Mercy Road

6 p.m. | Gross Auditorium in Hill Macaluso Hall

Featuring screen gems by Omaha’s own Omowale Akintunde and Jason Fischer

Support the work of these African-American community-based cinema artists

Next up – three short films by Jason Fischer

Screening on Tuesday, March 5:

•The art film “I Do Not Use” pairs searing, symbolic images to poet Frank O’Neal’s incendiary words.

•The documentary “Whitney Young: To Become Great” uses the civil rights leader’s life as a model for kids and adults to investigate what it takes to be great.

•And the award-winning “Out of Framed: Unseen Poverty in the Heartland” documents people living on the margins in Omaha.

Screenings start at 6 p.m.

Followed by Q & A with the filmmaker moderated by Leo Adam Biga.

Tickets and parking are free and all films are open to the public.

For more information, call 402-399-2365.

Still to come – a screening of Omowale Akintunde’s award-winning documentary “An Inaugural Ride to Freedom” about a group of Omahans who traveled by bus to the first Obama inauguration. Plus a bonus documentary on the second Obama inauguration. Followed by Q&A with the filmmaker moderated by Leo Adam Biga. Date and time to be determined. Watch for posts announcing this wrap-up program in the Local Black Filmmakers Showcase.

Sandhills life gets big screen due thanks to filmmaker Georg Joutras and his “Ocean of Grass”

Sandhills life gets big screen due thanks to filmmaker Georg Joutras and his “Ocean of Grass”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the March-April 2019 edition of Omaha Magazine

This decade has found Nebraska’s wide open spaces pictured on the big screen more than ever before. First came the melancholic, madcap road trip of Alexander Payne’s Nebraska in 2013. Then, in 2018, came the Coen Brothers’ Western anthology fable The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Earlier that same year Georg Joutras debuted his documentary Ocean of Grass about a year in the life of a Sandhills ranch family.

Where Payne and the Coens use Nebraska landscapes and skyscapes as metaphoric backdrops for archetypal but fictional portraits of Great Plains life, Joutras takes a deeply immersive, reality-based look at rural rhythms. Joutras celebrates the people who work the soil, tend the animals and endure the weather.

As Hollywood dream machine products by renowned filmmakers, Nebraska and Buster Scruggs enjoyed multi-million dollar budgets and national releases. Ocean of Grass, meanwhile. is a self-financed work by an obscure, first-time filmmaker whose small but visually stunning doc is finding audiences one theater at a time.

For his truly independent, DIY passion project, he spent countless hours at the McGinn ranch north of Broken Bow, Aside from an original music score by Tom Larson, Joutras served as a one-man band – handling everything from producing-directing to cinematography to editing. He’s releasing the feature-length doc via his own Reconciliation Hallucination Studio. In classic road-show fashion he delivers the film to each theater that books it and often does Q&As.

A decade earlier Joutras self-published a photo illustration book, A Way of Life, about the same ranch. The 56-year-old is a lifelong still photographer who feels “attuned to nature”. He operated his own gallery in Lincoln, where he resides. A chance encounter there with Laron McGinn, who makes art when not running the four-generation family ranch, led to Joutras visiting that expanse and becoming enamored with The Life.

Joutras, who grew up in Ogallala from age 11 on, had never stayed on a ranch or stopped in the Sandhills until the book. Those were places to drive past or through. That all changed once he spent time there.

Ogallala became his home when he moved there with his family after stints in his native New Jersey, then Florida and Texas, for his sales executive father’s jobs.

Joutras is not the first to create a film profile of a Nebraska ranch family, A few years before he moved to Ogallala, a caravan of Hollywood rebels arrived. In 1968, Francis Ford Coppola, along with a crew that included George Lucas and a cast headed by Robert Duvall, James Caan and Shirley Knight, shot the final few weeks of Coppola’s dramatic feature The Rain People. That experience introduced Duvall to an area ranch-rodeo family, the Petersons, who became the subjects of his 1977 documentary We’re Not the Jet Set, which filmed in and around Ogallala.

The McGinns’ ranching ways may have never been lensed by Joutras if not for his meeting Laron McGinn. Joutras had left a successful tech career that saw him develop a Point of Sale system for Pearl Vision and an automated radio system (PSI) acquired by Clear Channel. Having made his fortune, he retired to focus on photography. He did fine selling prints of his work. Then he met McGinn and produced A Way of Life – one of several photo books he produced.

Joutras only got around to doing the film after his family gifted him with a video camera. He began documenting things on the ranch. After investing in higher-end equipment he decided to ditch the year’s worth of filming he’d shot with his old gear to begin anew.

“It was evident immediately the picture quality was so much better than what I had shot the prior year that I was going to have to shoot it all again. So I put another year into shooting everything that goes on out there,” Joutras says. “I basically worked alongside the folks at the ranch. When something happened I thought I should capture, then I’d go into cinematographer mode.”

Upon premiering the film in Kansas City and Broken Bow, he discovered it resonates with folks, Sold-out screenings there have been followed by many more across Nebraska. The reviews are ecstatic.

“People are getting something out of this film,” he says, “They say it reflects the Nebraska ethos. I never did this film anticipating I’d make even one dollar on it. I just had this story I really wanted to tell. It’s certainly achieved much more than I thought it would. It’s done well enough that I’ve recouped pretty much what I put into it.”

Joutras believes his film connects with viewers because of how closely it captures a certain lifestyle. The rapport he developed and trust he earned over time with the McGinns paid dividends.

“I got the footage I did by being around enough and being embedded with them and being part of the crew that works out there. I wanted to earn my keep a little bit and they let me feed cows and run fence and check water. You have to be around enough to where you’re nothing special – you just kind of blend into the background.”

His depiction of a people and place without adornment or agenda is a cinema rarity.

“What I was really trying to capture was the feeling of this place – what it feels like to be out there among the people, the cows, the wind, the sun, the cold. Everything that makes it special. You’re seeing the real thing. Everything in the film is as it happened. Nothing was staged.

“These people are authentic. What they’re doing is authentic. Pretty much everyone you come in contact with in the ranching environment is their own boss. People don’t have to fake who they are. It’s really the American story of hard work trumps everything.”

The film makes clear these are no country bumpkins.

“They are some of the smartest people I know,” Joutras says. “They know how things work and are very articulate expressing their beliefs. By the end of the film I think you understand and admire them,”

He feels viewers fall under the same Sandhills spell that continues captivating him.

“The quality of life I think is exceptional. The pace of life slows down. You get to see real Americans doing real hands-on, get-in-the-mud work.”

He tried conveying in the film what he feels there.

“Out there I feel more in touch with nature and what’s important in life. I feel more grounded. I feel I can breath better. It’s really just a feeling of peace.”

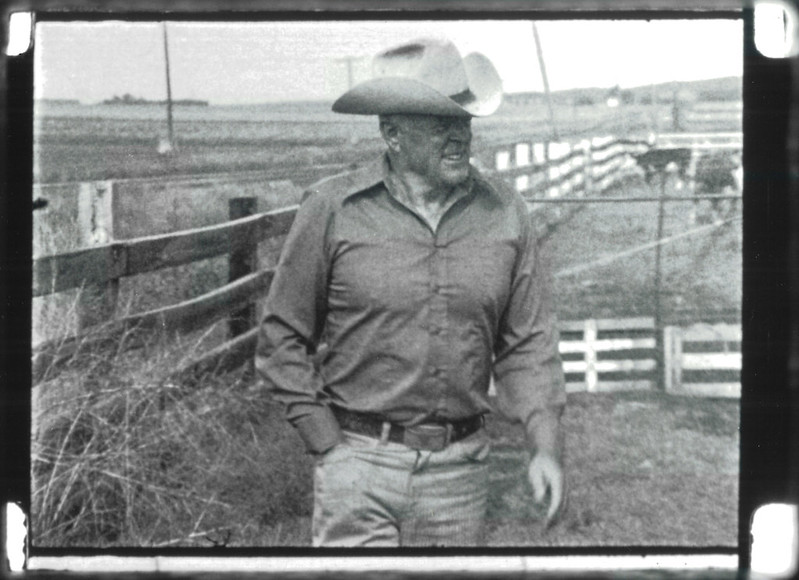

The rough-hewn spirit and soul of it is perhaps best embodied by family patriarch Mike McGinn.

“Mike’s a great guy. He’s sneaky funny. There’s nothing I enjoy more than being in a pickup with him going out to feed cows, which can take half the day or more. He was always reluctant to talk on camera. His was the last interview we got, and it’s just gold. He has all the great lines in the film.

“We got him to watch the film and at the end he turned to me and said, ‘That’s my entire life right there.’ That was a great moment for me.”

Rather than hire a narrator to frame the story, the only voices heard are those of the ranchers.”because they said it better than anyone,” Joutras says.

Beyond the McGinns and their hands, the film’s major character is the Sandhills.

“From a visual standpoint there’s nothing that gets me more excited than attempting to capture really interesting and varied scenic shots that speak to people. The Sandhills are beautiful beyond belief in all their details – from the grass to the slope of the hills to the clouds coming across the prairie to the sound of the wind. It all works together.”

He acquired evocative overhead shots by mounting cameras to drones. The aerial images give the film an epic scope.

Ocean’s visuals have made him a cinematographer for hire. He’s contributing to three films, including a documentary about the women of Route 66.

Future Nebraska-based film projects he may pursue range from rodeo to winemaking.

Meanwhile, he’s pitching Film Streams to screen Ocean.

“We’ll get it into Omaha one way or another.” More out-of-state screenings are in the worked.

Nebraska Educational Television has expressed interest. PBS is not out of the question.

Joutras is just glad his “little film that can” is getting seen, winning fans and giving the Sandhillls their due.

Visit the film’s website at http://www.oceanofgrassfilm.com.

Watch the trailer at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hNV6E5ihjP0.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

| 8.24 | FRI | 7:00 p.m. |

| 8.25 | SAT | 3:00 p.m. |

Local Black Filmmakers Showcase continues tonight with “Wigger”

Local Black Filmmakers Showcase featuring screen gems by Omaha’s own Omowale Akintunde and Jason Fischer

Support the work of these African-American community-based cinema artists

February-March 2019

College of Saint Mary

6 p.m. | Gross Auditorium in Hill Macaluso Hall

The work of award-winning Omaha filmmakers Omowale Akintunde and Jason Fischer highlight this four-day festival at College of Saint Mary.

Next up:

“Wigger” (2010)

From writer-director-producer:

Omowale Akintunde

Screening tonight – Thursday, February 28 @ 6 p.m.

Followed by a Q&A with flmmaker Omowale Akintunde.

Moderated by Omaha fllm author-journalist-blogger Leo Adam Biga.

Shot entirely in North Omaha, “Wigger” explores racism through the prism of a white dude whose strong identification with black culture ensnares and empowers him amidst betrayal and tragedy.”Wigger” is a spellbinding urban drama, which chronicles the life of a young, White, male (Brandon) who totally emulates and immerses himself in African American life and culture. Brandon is an aspiring R&B singer struggling to overcome the confines of a White racist, impoverished family headed by a neo-Nazi father who is absolutely appalled by his son’s total identification with Black culture. Additionally, he is oft times reminded of his position of privilege by virtue of being White in a White, racist society despite his adamant efforts to transcend “Whiteness”, institutionalized racism, and find a place for himself in a world in which he rejects Whiteness but is not always fully embraced by African American culture. Ultimately, this is the story of a young White, inner-city, male caught up in an emotional, psychological, experiential, and racial “Catch 22” determined to be granted acceptance in the life and culture with which he chooses to identify.

The Festival continues on Tuesday, March 5 with three short films by Jason Fischer taking center stage. The art film “I Do Not Use” pairs searing, symbolic images to poet Frank O’Neal’s incendiary words. The documentary “Whitney Young: To Become Great” uses the civil rights leader’s life as a model for kids and adults to investigate what it takes to be great. “Out of Framed: Unseen Poverty in the Heartland”documents people living on the margins in Omaha.

NOTE: The March 5 Jason Fischer program was originally scheduled for February 25 but was postponed due to inclement weather.

The February 26 program featuring Omowale Akintunde’s Emmy-award winning documentary “An Inaugural Ride to Freedom” was also postponed due to weather and will be rescheduled at a date to be determined later.

All films begin at 6 p.m. and will be screened in Gross Auditorium in Hill Macaluso Hall at College of Saint Mary, 7000 Mercy Road.

A Q & A with the filmmaker follows each screening.

Tickets and parking are free and all films are open to the public.

For more information, call 402-399-2365.

Holiday book sale: “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Holiday book sale:

“Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

by Leo Adam Biga

For you and/or the film lover in your life

Retails at $26

Now on sale for $20 directly from me

(while supplies last)

Acclaimed filmmaker Alexander Payne uses satire to take the measure of his times. Award-winning writer Leo Adam Biga draws on 20 years covering the writer-director to take the measure of this singular cinema artist and his work.

Film scholar-author Thomas Schatz (“The Genius of the System”) said:

“This is without question the single best study of Alexander Payne’s films, as well as the filmmaker himself and his filmmaking process. In charting the first two decades of Payne’s remarkable career, Leo Adam Biga pieces together an indelible portrait of an independent American artist.This is an invaluable contribution to film history and criticism – and a sheer pleasure to read as well.”

National film critic Leonard Maltin said: “Alexander Payne is one of American cinema’s leading lights. How fortunate we are that Leo Biga has chronicled his rise to success so thoroughly.”

Available at this special sale price only by contacting me here or at:

402-445-4666 or leo32158@co.net

If you want a copy mailed to you, send a check for $25 (includes shipping and handling) made out to Leo A. Biga, along with your return address, to:

Leo A. Biga

10629 Cuming St.

Omaha, NE 68114

Please indicate if you wish a signed copy.

Nebraska Screen Gems – Rediscover Oscar-winning 1983 film “Terms of Endearment” on Wednesday, Oct. 24

Screening-discussion of the most decorated of all the Screen Gems Made in Nebraska:

Screening-discussion of the most decorated of all the Screen Gems Made in Nebraska:

“Terms of Endearment” (1983)

The James L. Brooks film became a critical and box office smash. It brought legendary stars Jack Nicholson and Shirley MacLaine to the state along with then-newcomer stars Debra Winger and Jeff Daniels. Nearly two decades later, Nicholson would return to Nebraska to star in Alexander Payne’s Omaha-shot “About Schmidt.”

“Terms of Endearment” shot extensively in and around Lincoln, Nebraska.

Wednesday, October 24, 5:45 p.m.

Metro North Express at the Highlander

Non-credit Continuing Ed class

Part of fall Nebraska Screen Gems film class series

Register for the class at:

https://coned.mccneb.edu/wconnect/ace/ShowSchedule.awp?&Criteria…

This class in my fall Nebraska Screen Gems series will screen and discuss a film that established James L. Brooks as a feature writer-director to be reckoned with following his success in television.

Brooks stamped himself a modern movie comedy master with his 1983 adaptation of the Larry McMurtry novel “Terms of Endearment.” This feature film directorial debut by Brooks came after he wrote the movie “Starting Over,” which Alan J. Pakula directed, and after he conquered television by creating “Room 222,” “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and “Taxi.” For his first film as writer-director, Brooks wonderfully modulates the comedy and drama in a story about a young wife-mother whose marriage is falling apart and her widowed mother who unexpectedly finds new romance. Infidelity and terminal cancer get added to the high stakes. In what could have been a maudlin soap opera in lesser heads plays instead as a raw, raucous slice of life look at well-meaning people stymied by their own flaws and desires and by events outside their own control.

The film was partially shot in Nebraska. The exteriors intended to be in Des Moines, Iowa, Kearney, Nebraska, and Lincoln, Nebraska, were all filmed in Lincoln. Many scenes were filmed on or near the University of Nebraska-Lincoln campus, During filming in Lincoln, Debra Winger met the then-governor of Nebraska, Bob Kerrey, and wound up dating him for two years.

To a man and woman, the principal characters are unapolegetically their own strong-willed people. MacLaine is the vain, severe Aurora Greenway, whose fierce love and criticism of her daughter Emma (Winger) drives a wedge between them that their devotion to each other overcomes. Daniels plays Emma’s unfaithful professor husband Flap. Nicholson plays Garrett Breedlove, the carousing ex-astronaut neighbor of Aurora who, unusual for him, finds himself falling for a woman his own age when he discovers that his neighbor is not the brittle bitch he thought.

During the period “Terms” was in production, MacLaine and Nicholson were the two big names in the cast, but the lead, Winger, had only just become a star by virtue of her performance in “An Officer and a Gentleman” (1982). DeVito was a TV star from “Taxi.” Lithgow was still better known for his stage work than his screen work. Daniels was a newcomer.

The strong ensemble cast is headed by Nicholson and MacLaine, who inhabit their roles so fully that it’s hard to imagine anyone else in them.

Veteran Omaha stage actor Tom Wees has a speaking part as a doctor and ably holds his own with the heavyweight stars.

Of all the films ever made in Nebraska, “Terms” is by far the most honored. It was nominated for 11 Oscars and won five (for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay and MacLaine as Best Actress and Nicholson as Best Supporting Actor.) The picture also won four Golden Globes: Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Actress in a Drama (MacLaine), Best Supporting Actor (Nicholson) and Best Screenplay (Brooks).

Brooks followed this film with two more instant comedy classics: “Broadcast News” and “As Good as It Gets” and added to his TV legend by creating “The Simpsons.”

Here is a link to register for the class:

https://coned.mccneb.edu/wconnect/ace/ShowSchedule.awp?&Criteria…

Film Connections Interview with Francis Ford Coppola about the making of “The Rain People”

Film Connections

Interview with Francis Ford Coppola about the making of “The Rain People”

In 1968 the future Oscar-winning filmmaker and his cast and crew ended up in Nebraska for the last few weeks shooting on an intimate road picture he wrote and directed titled “The Rain People.” A very young George Lucas was along for the ride as a production associate whose main task was to film the making of the movie.

Coppola’s indie art film starring Shirley Knight, James Caan and Robert Duvall was released in 1969. The experience forged strong personal and professional bonds. It not only resulted in the Lucas documentary “The Making of The Rain People,” but it’s how Lucas came to cast Duvall to star in his debut feature “THX-1138,” which Coppola produced. Coppola also produced his protege’s second film, “American Grafitti.” The two also co-founded American Zoetrope. Meanwhile. Coppola cast Duvall and Caan in his crowing achievement, “The Godfather.” From obscurity in 1969. Coppola and Lucas became start filmmakers who helped usher in the New Hollywood.

The experience of “The Rain People” also introduced Duvall to a Nebraska ranch-rodeo family, the Petersons. he came to make the subjects of his own first directorial effort, “We’re Not the Jet Set.”

I am documenting this little-known chapter Nebraska Screen Gem as part of my Nebraska Screen Heritage Project, in a college class I’m teaching this fall and in articles I’m writing and in posts I’m making. On this blog you can also find my interviews with Knight, Caan and Duvall. I have also interviewed several others who were part of this confluence of talent and vision and I will be posting those over time.

My next step is to bring back as many of the principals involved in these three films for screenings and discussions.

Here is my interview with Francis Ford Coppola:

LAB: The Rain People is very much a road picture, and you and your small cast and crew traveled in cars and, I think I read somewhere, a mini-bus from Long Island to the South and then to the Midwest to capture the journey Shirley Knight’s character makes. Did you happen to shoot the film largely in sequential order?

FFC: “Generally I tried to shoot in sequential order, though if there was an opportunity to save money to shoot slightly out of it, I would.”

LAB: Is it true you hadn’t finished the screenplay when shooting began?

FFC: “I had a complete screenplay, but was prepared to make any changes if we encountered something interesting along the way.”

LAB: And so I take it that you hadn’t scouted all the locations beforehand but instead left yourself open to discovering places and events you then integrated into the story and captured on film?

FFC: “Exactly. We had a route, and wasn’t sure of exact location, But my associate Ron Colby was scouting a little ahead of us and we were in communication.”

LAB: What about Ogallala, Neb. – was it by design or chance that you ended up there?

FFC: “By chance. but once there, I think we felt at home and there were many good place that suited our story. And the people were nice and there was a nice little picnic grounds. And I remember a big steak cost about $6, so we’d have barbecues and we were all happy there.”

LAB: It was your first time working with the three principal cast members. At that point in your careers, Shirley was probably the best known of anyone on the project. I read somewhere that you met her at the Cannes Film Festival, when she was there with Dutchman, and that you saw her crying after a confrontation with a journalist and you consoled her with, ‘Don’t cry, I’m going to write a film for you.’ Is that right?

FFC: “Yes, that story is true. I think I was influenced by the notion of Europeans working with leading ladies, Monica Vitti or Goddard’s Anna Karinia, and so yes, I said that to her.”

LAB: You obviously admired her work.

FFC: “I liked Dutchman very much, where I also admired (her co-star) Al Freeman Jr.”

LAB: What about Jimmy and Bobby – did you know them before the project, and did any of their previous work make an impression on you?

FFC: “I had chosen Jimmy, and in fact before I even had the money or arrangement to make The Rain People, George Lucas and I went east and shot some ‘second unit’ footage at a football game and different images.”

LAB: Bobby mentioned that he might have replaced another actor who had originally been cast in his role, is that right?

FFC: “Original. For the rehearsals we had Rip Torn, but had as part of his deal that we give him the Harley motorcycle so he could learn to drive it well. We did, and he parked it in front of his house in New York City, and it was stolen. He came back to us and said it was his deal to have a Harley, so we had to buy him another. But all we could afford was a good quality secondhand one -– which then he said wasn’t his deal. It was supposed to be a good one. So later in the production, when Ron Colby called him to say we needed him to get his shoe and calf measured for the boots, he said, ‘That’s it’! and quit. I had seen Bobby in a movie (Countdown’ he made with Jimmy Caan for TV that Robert Altman had directed. I thought both of them were fantastic. So true and real in that kind of movie, so I offered the part to Duvall.”

LAB: I understand that in preproduction you like to rehearse or to at least do table reads with cast, or at least that’s how you preferred to do things then. Did you do anything like that for Rain People?

FFC: “Yes, I had been a theater major in college, and so I was very used to a few weeks of rehearsal and, yes, I did a rehearsal period for The Rain People and I’ve done it for every film after that.”

LAB: As you know, Jimmy and Bobby became fast friends with a local ranch-rodeo family there, the Petersons. They were this loud, rambunctious bunch. Did you meet any of the clan, particularly the patriarch, B.A., who is the central figure in the documentary Duvall made about the family, We’re Not the Jet Set?

FFC: “I remember the family, and Bobby’s interest in them. He was always interested in things that were ‘real’ authentic, as opposed to the fake reality of people in movies and TV shows, and thus he made We’re Not the Jet Set. I remember the song he wrote (?).”

LAB: What about another area ranch-rodeo family Jimmy and Bobby came to know, the Haythorns, did you meet any of them, particularly patriarch Waldo Haythorn?

FFC: “No, I don’t remember them. but perhaps I met them.”

LAB: I know that Duvall has often sought your opinion on the projects he’s directed – did he do so for We’re Not the Jet Set, and assuming you’ve seen the film what do you think of it?

FFC: “Over the years, he’d come visit me and bring me his films and ask for my reaction. I was pleased to be of any help I could be, especially after he did me the great favor of appearing in a tiny role in The Conversation.”

LAB: When you worked with Duvall on Rain People and later on the first two Godfather pictures and The Conversation, did you sense he had a directorial sensibility about him?

FFC: “I didn’t think about it. Iv’e always known that actors make the best directors among all the crafts – writing, editing, assistant directors, et cetera. There’s a long list of actors who became fine directors.”

LAB: After Rain People did you know you wanted to work with Caan and Duvall again? When you got The Godfather did you immediately think of them?

FFC: “I liked working with them very much, and yes, they were on all the early lists of names for The Godfather.'”

LAB: The Rain People production team also included two key collaborators in George Lucas and Mona Skager. The film came at an interesting juncture in your young careers. You had wanted to be an independent director but soon found yourself being a studio wonk. After Finian’s Rainbow it appears you intentionally set out to liberate yourself from the studio apparatus with Rain People, is that right?

FFC: “Yes. George Lucas was, and still is, like a younger brother to me. I knew early on that he was a great talent, and though a different personality to my own, one that was very helpful to me, and stimulating to me. hH’s a fine, very generous person, so bright and talented.Ii am very proud of him. Mona was the first ‘key associate’ I had, starting out as a secretary and blossoming into an all-around associate in the entire process.”

LAB: I believe that you, Lucas and Skager formed American Zoetrope not long after the project. Did the idea for Zoetrope come to you during the making of the film or did the experience of that film point you in the direction of launching your own studio?

FFC: “The idea for American Zoetrope really came from the theater club that I was president (or executive producer) of in college, called ‘The Spectrum Players.’ It still exists at Hofstra University in Long Island, and I was the founder and merely took many of the ideas of a creative entity that attempted to create art works with it’s own means. George was essentially a co-founder, and Mona was what they called in those days ‘the Girl Friday’ – today a production supervisor who was involved in all we were trying to do.”

LAB: Rain People certainly fits the vision you had for Zoetrope in terms of small, personal art films. which Godfather I and II, Apocalypse Now and subsequent pictures took you away from for many years before you returned to this model the last few years. Do you still regard Rain People warmly after all these years?

FFC: “Yes, very much. I wish Warner Bros. would allow me to buy it back, as there’s not even a DVD available about it (there is now). It has value, I think, beyond being an early film of mine but as one of the first films to touch on the theme of ‘women’s liberation’.”

LAB: The documentary Lucas made about the making of the film captures you and the others before you became so well known, which makes it a very interesting time piece, don’t you think?

FFC: “George’s film is excellent, if I may say, and he caught the spirit of this exciting trip, which for us was an adventure into filmmaking.”

LAB: In addition to working again with Caan, Duvall, Lucas and Skager, you also ended up working again with Rain People cinematographer Bill Butler, and so that film really forged some key relationships didn’t it?

FFC: “Bill Butler did a terrific job, and it was a pleasure to work with him.”

LAB: And, of course. Lucas ended up casting Duvall in his first feature, THX-1138, which you produced.

FFC: “Yes, George got to meet Bobby and knew he should be in THX-1138.”

LAB: The confluence of talent and connections that arose out of Rain People has always fascinated me, as has the fact that within a few years of its making you and Lucas helped usher in the New Hollywood and became kingpins in the industry. But you tried to escape the constraints and weight of studio filmmaking over the next few decades, and you finally have regained the independence you found on Rain People, all thanks to your wine company. You’ve kind of come full circle, haven’t you?

FFC: “I hope so. With the conclusion of the ‘student’ films I just made, Youth Without Youth, Tetro and Twixt, I feel ready to tackle a new and much bigger project. I feel blessed in my life, and of course hI ope I’m able to enjoy the freedom and autonomy enjoyed in those last three, on the new one, which will need a much bigger budget. I hope fate allows me to do it, as I don’t yet feel i’ve achieved what I long to do in film.”

LAB: As you know, Lucas has long talked about freeing himself from his corporate machine, CGI endeavors and Star Wars franchises to make small experimental films. Have you nudged him at all to say, ‘Hey, look, I did it, you can too’?

FFC: “George is so talented, anything he attempts will be a pleasure to see. Yes, I always ask him to quit fooling with the Star Wars ‘franchise’ and go back to what he and I always wanted: to make personal — experimental films. I have no doubt that he will succeed.”

Nebraska Screen Gems – “The Rain People” & “We’re Not the Jet Set”

Rare screening-discussion of two Screen Gems Made in Nebraska:

Rare screening-discussion of two Screen Gems Made in Nebraska:

“The Rain People” (1969) & “We’re Not the Jet Set” (1977)

Francis Ford Coppola’s dramatic road film “The Rain People” & Robert Duvall’s cinema verite documentary “We’re Not the Jet Set”

Both films shot in and around Ogallala, Nebraska

Wednesday, October 17, 5:45 p.m.

Metro North Express at the Highlander

Non-credit Continuing Ed class

Part of fall Nebraska Screen Gems film class series

Register for the class at:

coned.mccneb.edu/wconnect/CourseStatus.awp?&course=18SECOMM178A

This class in my fall Nebraska Screen Gems series will screen and discuss a pair of films made in Nebraka by Hollywood legends before they were household names.

An unlikely confluence of remarkable cinema talents descended on the dusty backroads of Ogallala, Neb. in the far southwest reaches of the state in the summer of 1968.

None other than future film legend Francis Ford Coppola led this Hollywood caravan. He came as the producer-writer-director of The Rain People, a small, low-budget drama about a disenchanted East Coast housewife who, upon discovering she’s pregnant, flees the conventional trappings of suburban homemaking by taking a solo car trip south, then north and finally west. With no particular destination in mind except escape she gets entangled with two men before returning home.

Coppola’s creative team for this road movie included another future film scion in George Lucas, his then-protege who served as production associate and also shot the documentary The Making of The Rain People. The two young men were obscure but promising figures in a changing industry. With their long hair and film school pedigree they were viewed as interlopers and rebels. Within a few years the filmmakers helped usher in the The New Hollywood through their own American Zoetrope studio and their work for established studios. Coppola ascended to the top with the success of The Godfather I and II. Lucas first made it big with the surprise hit American Graffiti, which touched off the ’50s nostalgia craze, before assuring his enduring place in the industry with the Star Wars franchise that made sci-fi big business.

Rain People cinematographer Bill Butler, who went on to lens The Conversation for Coppola and such projects as One Few Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Jaws and The Thorn Birds, was the director of photography.

Heading the cast were Shirley Knight, James Caan and Robert Duvall. Though they enjoyed solid reputations, none were household names yet. Caan’s breakthrough role came two years later in the made-for-television sensation Brian’s Song (1970). The pair’s work in Coppola’s The Godfather elevated them to A-list status. Rain People was not the last time the two actors collaborated with the filmmakers. Duvall starred in the first feature Lucas made, the science fiction thriller THX-1138. The actor went on to appear in Coppola’s first two Godfather pictures as well as The Conversation and Apocalypse Now. After his star-making performance as Sonny Corleone in The Godfather Caan later teamed up with Coppola for the director’s Gardens of Stone.

Among Rain People’s principals, the most established by far then was Knight, already a two-time Best Supporting Actress Oscar nominee (for The Dark at the Top of the Stairs and Sweet Bird of Youth).

The experience of working together on the early Coppola film forged relationships that extended well beyond that project and its small circle of cast and crew. Indeed, this is a story about those connections and their reverberations decades later.

For example, Duvall and Caan were already horse and Old West aficionados when they were befriended by a couple of Nebraska ranch-rodeo families, the Petersons and Haythorns. The interaction that followed only deepened the artists’ interest in riding and in Western lore. This convergence of New York actors and authentic Great Plains characters produced some unexpected spin-offs and helped cement enduring friendships. Duvall and Caan remain best buddies to this day.

Duvall became so enamored with the colorful, cantankerous Peterson clan, a large, boisterous family of trick riders led by their late patriarch, B.A. Peterson, that he made a documentary about them and their lifestyle called We’re Not the Jet Set. The actor returned to Nebraska several times to visit the family and to shoot the film with a skeleton crew. It was his first film as a director and it’s easy to find resonance in it with his future directorial work (Angelo My Love, The Apostle, Assassination Tango).

With this class I am trying to bring this story to light and to help revive interest in these films, particularly We’re Not the Jet Set. Recently, Turner Classic Movies added The Rain People to its rotating gallery of films shown on the cable network. But Jet Set remains inaccessible. I would also like to see the Lucas documentary, The Making of the Rain People, revived since it is a portrait of the early Coppola and his methods a full decade before his wife Eleanor shot the documentary Hearts of Darkness about the anguished making of Apocalypse Now. The story I’m telling is also an interesting time capsule at a moment in film history when brash young figures like Coppola, Lucas, Duvall, and Caan were part of the vanguard for the New Hollywood and the creative freedom that artists sought and won.

With their reputation as expert horsemen and women preceding them, several of the Petersons ended up in the film industry as wranglers, trainers and stunt people, boasting credits on many major Hollywood projects. One member of the family, K.C. Peterson, even ended up working on a film Duvall appeared in, Geronimo, An American Legend.

We’re Not the Jet Set has rarely been seen since its late 1970s release owing to rights issues, which is a real shame because it’s a superb film that takes an authentic look at some real American types. Duvall is justly proud of what he captured in his directorial debut. Don’t miss this chace to see what is a true gem.

Here is a link to register for the class:

coned.mccneb.edu/wconnect/CourseStatus.awp?&course=18SECOMM178A

Hollywood Dispatch: On the set with Alexander Payne – A Rare, Intimate, Inside Look at Payne, His Process and the Making of ‘Sideways’

Hollywood Dispatch

Taking Alexander Payne up on his invitation to view the making of Sideways, his first movie made outside Nebraska, my America West early bird special from Omaha to Phoenix, Ariz. the Monday morning of Oct. 27 I have plenty of time to think. From Phoenix, I catch a commuter flight to Santa Barbara, Calif., the nearest city to the Sideways shoot and the start of wine country.

In this $17 million project lensed for Fox Searchlight Pictures that began filming Sept. 29 and wrapped Dec. 6, Payne is once again exploring the animus of dislocated characters running away from their problems and seeking cures for their pain.

Coming off About Schmidt, the 2002 hit that played more sad than funny for many viewers, but that garnered critical plaudits, a juried Cannes screening, a handful of Oscar nods and the biggest box-office take yet for any of his films – an estimated $106 million worldwide – one might expect Payne to lighten up a bit.

After all, his films have thus far fixed a withering satiric-ironic eye on human frailties.

Citizen Ruth, Election and About Schmidt heralded him as an original auteur, a considered observer and a strong voice in the emerging post-modern cinema.

One only has to recall: paint-sniffing Ruth Stoops, the unlikely poster girl for the embattled-exploitative abortion camps, in Citizen Ruth; student election-rigging teacher Jim McAllister acting out his frustrations against the blind ambition of student Tracy Flick in Election; or the existential crisis of Warren Schmidt, an older man undone and yet strangely liberated by his own feelings of failure inSchmidt, a funny film that still felt more like a requiem than a comedy.

While Sideways will never be confused with a Farrelly brothers film, it’s a departure for Payne in its familiar male-bonding structure, its few but priceless slapstick gags and its romantic, albeit dysfunctional, couplings. Its surface contours are that of a classic buddy movie, combined with the conventions of a road pic, yet Sideways still fits neatly within the Payne oeuvre as another story of misfit searchers.

In Sideways, the search revolves around two longtime California friends, the shallow Jack and the intellectual Miles, who ostensibly set off on a fun, weeklong wine-tasting tour in the verdant rolling coastal hills northwest of Santa Barbara. Their trip soon turns into something else, a walkabout, pilgrimage, forced march and purging all in one, as they confront some ugly truths about themselves en route. The buddy pairing is built on a classic opposites-attract formula.

If, as they say, casting is most of a film’s success, then Payne’s home free. After seriously considering filling the rich parts with mega-stars George Clooney (Jack) and Edward Norton (Miles), he went with “the best actors for the roles” and found perfect fits. Jack, played by Thomas Haden Church (best known for the 90s TV series Wings), is the dashing, skirt-chasing extrovert, a former soaps actor reduced to voice-over work. Now in his 40s, he’s about to be married for the first time, and this inveterate womanizer goes on the wine tour not to enjoy the grape but so he can go on one last fling.

As he tells his well-moneyed bride-to-be, “I need my space.”

Code words for philandering.

Miles, essayed by Paul Giamatti (American Splendor), is the smart, neurotic introvert – a failed writer unhappily stuck as a junior high English teacher and still obsessing over the ex-wife he cheated on. Miles concocts the tasting tour as much to indulge his own seemingly perfect passion for wine, which he still manages to corrupt with his excessive drinking, as to treat Jack to some final bachelor debauchery. When Jack announces his intention to get he and Miles laid, it’s clear that as much as the repressed Miles expresses dismay and outrage at Jack’s libidinous behavior, he lives vicariously through his friend. And as much as Jack is irritated by Miles’ depression, often on the verge of, as Jack says, “going to the dark side,” and by Miles’ warnings that he curb his unbridled sexual appetite, Jack understands his friend’s dilemma and appreciates his concern.

Eventually the two hook up with a pair of eager women whose presence upsets the balance in the buddies’ relationship and redirects the tour. Jack loses his mind over Stephanie, a hottie party girl of a wine pourer played by Sandra Oh, a darling of indie cinema. Longtime companions, Payne and Oh were married in January. Miles tentatively feels things out with Maya, a nurturing waitress and fellow wine buff portrayed by Virginia Madsen, a veteran of features and television.

In classic road picture fashion, the foursome traverse a string of wineries, diners, motels and assundry other stops on the highways and byways in and around Santa Barbara, Los Olivos, Solvang and Buellton. Along the way, relations heat up with the gals before a reckoning – or is it bad karma? – causes things to come crashing down on the guys. Each has his own cathartic rude awakening. A pathetic, repentant Jack goes through with the wedding. A wizened Miles, perhaps finally outgrowing Jack and exorcising his own demons, takes a hopeful detour at the end.

I was about to take my own detour.

During a brief layover in the Phoenix airport, where faux southwestern themes dominate inside and tantalizing glimpses of real-life mesas tease me outside, my fellow travelers and I are reminded of the raging California wildfires when flights to Monterey are postponed due to poor visibility. On the hop from Sun City to Santa Barbara, sheets of smoke roll below us and billowing plumes rise from ridges on the far horizon beyond us.

I’ve arranged for the Super Ride shuttle to take me to Solvang, the historic Danish community I’ll be staying in the next six nights. At the wheel of the Lincoln Town car is James, a former merchant mariner who describes the Marine Layer that drifts in from the Pacific, which along with moderate temps and transverse valleys, makes the area prime ground for its many vineyards.

We cut over onto U.S. 154 and then into Buellton, home of Anderson’s Split Pea Soup, passing an apple orchard and ostrich farm en route to the kitschy, friendly tourist trap of Solvang and its gingerbread architecture. Everything is Danish, except the Latino help. Michael Jackson’s Neverland ranch is nor far from here and I’m told the veiled pop star is a familiar sight in town. After settling into a low-rent motel where most of the crew stays, I unwind with a walk through the commercial district, ending on the outskirts of town, where a mini-park overlooks the Alisal River Course below and oak tree-studded hillsides beyond. The brushed, velvety blue-green hills resemble a Bouguereau painting of French wine country. All that’s missing are the peasant grape-pickers. Wildfire smoke filters a screen of sunlight across the hills, obscuring outlying ridge lines in a ragged gray silhouette.

After a Danish repast in the afternoon and a burger-malt combo at night, I make last minute preps in my room for tomorrow, my first day on the set.

It breaks a sun-baked Monday. As I soon learn, mornings start chilly, afternoons heat up and nights cool down again out here. On what becomes my daily ritual, I take a morning constitutional walk to the overlook.At 8:30, the publicist assigned to escort me, Erik Bright, arrives. He sports the cool, casual, hip vibe and ambitious animus of a Hollywood PR functionary, a sort of modern equivalent of the hungry press agent Tony Curtis plays in Sweet Smell of Success. He’s eager to please.We drive directly to the set, the location of which these first two days is the nearby River Course. Once parked, Bright commandeers a golf cart to transport us on set, where a semi-circle of crew and cast is arrayed on a fairway, not unlike painters considering subjects in a park. As we approached at a whisper, a take unfolded. After intoning “Cut” in a businesslike tone, Payne’s band of grips, gaffers, ADs and PAs busily attended to setting up the next take of this scene.Seeing me out of the corner of his eye, Payne halts what he’s doing to come over and greet me. “Welcome,” he says, shaking my hand, before excusing himself to resume work. It’s the official seal of approval for me, the outsider. He seems totally in his element, directing with calm acuity. The closest he comes to raising his voice is when he politely asks the set to be quieted, explaining, “I’ve got to focus here.”

Nearing middle-age, he certainly looks the part of the legendary artist with his intense gaze, his piercing intelligence, his shock of black hair, now peppered with gray, his lithe body, his grace under fire and his immersion in every aspect of the process, from fiddling with props to getting on camera. Then, there is the relaxed Mediterranean way he has about him, indulging his huge appetites for life and film. He burns with boundless curiosity and energy and embodies a generous La Dolce Vita spirit that makes work seem like play. Clearly the journey for him is the joy.

The Producers

By the time I meet the film’s producer Michael London and co-producer/first AD George Parra, a few takes are in the can. The elegant London, often seen on his cell phone, takes a laissez-faire approach to this project. The strapping Parra, often in radio contact with crew, acts as Payne’s right-hand man and gentle enforcer.

“OK, AP, we’re ready, sir. Let’s go. Rolling.” That’s Parra talking, overseeing the production’s moment-by-moment organization, efficiency and schedule. Because time is big money in film, his job boils down to “keeping Alexander on track.”

“What stands out for me is how much he loves the actual day-to-day process of filmmaking,” said Sideways producer Michael London (Forty Days and Forty Nights), “and how much he loves the camaraderie with people on the set. Filmmaking has become this kind of process to be endured. And it’s the opposite with Alexander. He actually loves the details. It’s wonderful – his enthusiasm and appreciation and work ethic. He’s so happy when he’s in his element, and the pleasure he takes out of it is so palpable to everybody. This is kind of what he was born to do.”

Amid the disaffected posturings, digital imaginings and non-linear narratives employed by so many hip young filmmakers, Payne is something of a throwback. Steeped in film history and classical technique, he eschews neo-genre stylistics to storytelling. Rather than bury a scene in sharp camera moves or extreme angles, special effects and draw-attention-to-itself editing, he’s confident enough in his screenplay and in his direction to often let a scene play out, interrupted by few cutaways or inserts. It’s an apt style for someone attuned to capturing the real rhythms and ritualistic minutiae of everyday life.

It’s all part of the aesthetic he’s developed. “Alexander has an evolving philosophy he’s begun to articulate a lot more clearly in the wake of About Schmidt, which is that contemporary movies have begun to focus more and more on extraordinary characters and situations,” London said, “and that filmmakers have lost touch with their ability to tell stories about real daily life, real people, real issues, real feelings, real moments.

“Where most filmmakers would run screaming from anything that reminds people of every day life, he loves the fact you can film every day life and have people take a look at themselves in a different context than what they’re accustomed to. And I think it’s really important and admirable. It’s also a very humble skill.

“Instead of trying to imagine and exaggerate, it’s really just observing. It’s a more writerly craft and a more European sensibility. I think it’s an underrated gift. I don’t think people realize how difficult it is to create that kind of verisimilitude on screen. That’s why he’s always at war with all the conventions of the movie world aimed at glamorizing people.”

Upon casually saying “Action,” Payne watches takes with quiet intensity, afterwards huddling with actors to add a “Let’s try it faster” comment here or a “Why don’t we try it this way?” suggestion there and listening to any insights they may impart. Reacting with bemused delight to a performance, he says, “That’s funny” or flashes a smile at no one in particular. After announcing “Cut,” he typically says “Good” or “Excellent” if pleased or “Let’s try one more” if not. Takes, which can be spoiled by anything from planes flying overhead and car engines firing in the background to missed cues and flubbed lines to the film running out or a camera motor breaking down, are also opportunities to refine a scene. As the takes mount, Payne remains calm. As he likes saying, “Filming is just all about harvesting shots for editing.”Payne speaks with the actors about a moment when they confront other golfers, going over various physical actions.

“Let’s see how real that feels,” he tells Haden Church, who carries the brunt of the action. “Now, knowing all these options, just follow your instinct. You’re a Medieval knight. Be big.”

“Be bold,” Haden Church replies, before screaming profanities and brandishing his club.

Several times during the two-day golf shoot, stretching from early morning through late afternoon and encompassing several set-ups, the PanaVision-Panaflex cameras are reloaded after their film magazines run out, often spoiling takes. A film magazine has 1,000 feet or 10 to 11 minutes of film. At one point Payne asks for “Camera reports?” and when none are forthcoming calls for “a little tighter” shot. The camera dollies are moved closer. Payne later tells me the shoot was “slightly more unbridled” than normal for him, meaning he shot more coverage than usual.

By afternoon, the sun and heat grow fierce. With little or no natural shade, people seek protection in golf carts or under various flags and screens used to bounce light off actors. Sun screen is liberally applied, and bottled water greedily consumed. Heat-related or not, a camera’s motor gives out, rendering it inoperable. A replacement is ordered.

Payne, who enjoys a sardonic give-and-take with director of photography Phedon Papamichael, says, “I brought you this far, now make it brilliant.”

The DP responds, “I want my second camera back.”

When the situation calls for it, Payne maintains a professional, disciplined demeanor. Setting up a shot, he gives precise directions while inviting input from collaborators, especially Papamichael (Identity), a native of Greece with whom he enjoys a lively working relationship. Papamichael says they take turns getting on camera to view set-ups, each prodding the other with ideas and inevitably admitting, “We pretty much end up where we started.” Before the cast arrives on set, Payne often acts out the physical action himself for the benefit of Papamichael and crew. He checks cheat sheets, including his “sides,” a printed copy of the script pages being shot each day, and his “shot list,” a personal breakdown of what he’s after in terms of camera, lighting, movement, motivation and mood.

Before filming, he often has actors run through scenes in rehearsals. Sometimes, surreptiously, he has ADs and PAs shush the throng of crew and extras while signaling the cameras to roll, hoping to pick up more natural, unaffected performances that way.

Payne acknowledges Papamichael’s influence on his visual sense: “I’m working with a DP who calls for that [lush] stuff more easily than my previous crew did. Sometimes, early on, I would say to him, ‘It’s too pretty,’ and he’d go, ‘No, it’s just another side of yourself you’re afraid of.’ So, what the hell, it’s another side of myself and I’m just going with it.”

Papamichael’s also pushed Payne, albeit less successfully, to steer away from his favored high camera angles to more eye-level shots.

“He was accusing me the first couple weeks of always wanting to go high, as though I’m God or something, to look down on characters,” Payne said. “I don’t know, sometimes I get bored looking at people straight-on, so I go higher or lower. It just makes the angle more interesting to me, unless I’m missing something unconscious in myself about some hideous superiority complex.”

Papamichael, a favorite cinematographer of Wim Wenders, is working with Payne for the first time though they’ve known each other for years. The cinematographer said it takes awhile for a director and DP to mesh but that “every picture finds its own language pretty quickly. You can sort of talk about it in theory, but then very often it happens. The picture will sort of tell you what needs to be done. This show has not had the extent of coverage and camera movement we usually have on shows because we’re playing a lot of things in-close and letting the actors operate within that frame. It sort of seems to be playing better with simpler shots.”

During a lull, I learn from London and Payne that the owner of a location slated for use in the film is refusing to honor a signed agreement, thereby trying to hold up the production for more money. London slips off to deal with the problem.

Lunch break finds cast and crew descending on base camp a few blocks away. Here, the caravan of Sideways trailers and trucks are parked, along with a mobile catering service doling out huge varieties of freshly prepared food. An American Legion post hall serves as the cafeteria, with people sitting and eating at rows of long tables.

After eating very little, Payne said, “Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to take my nap,” a daily ritual he’s followed since Election.”

Tuesday is a reprise of Monday’s heat, schedule and location.

Payneful Reality

That night, I interview Payne over dinner at the Los Olivos Cafe, an intimate spot reeking of laid-back California chic and, de rigueur for this region, an extensive wine list. It’s where the film shoots the next three days. As usual, his careful attention to my questions and to his answers is surprising given all that’s on his mind. Like any good director he has the gift for focusing on whomever he’s with and whatever he’s doing at any given time.

Nothing’s too simple or small to escape Payne’s attention, “Well, all I can say is details are everything. I don’t really conceive of broad strokes. If you’re kind of operating from a type of filmmaking that sees art as a mirror of life and film as the most capable and verisimilar mirror, than you’ve got to pay a lot of attention to details, and I kick myself when I miss them.”

For him, it’s a philosophy that informs, at the most basic level, the very nature of his work.

“You want things to ring true to the audience, and you want to inspire in the audience what literature does and what poetry sometimes does, which is the shock of recognition – having something pointed out to you which you’ve lived or intuited or thought on an unconscious level and suddenly the writer brings it to your consciousness. I just love that: the recognition of until this moment, of an articulated truth. I’m not saying my films are doing that on a very profound level, but at least in the minutiae I want those things right. Again, it’s all about the details, and a lot of times story operates within those details. I don’t know if it’s just story, because I’m acting instinctively, but it’s probably all these things – story, character and then the texture of the reality you’re recreating, presenting.”

In pursuit of the real, Payne vigorously resists, or as London puts it, “crusades” against the glam apparatus of the Hollywood Dream Factory. “You have to fight a couple things. One, is the almost ideology – it’s that deeply entrenched – in American filmmaking that things have to be made beautiful … more beautiful than they appear in real life in order to be worthy to be photographed, and I just oppose that,” Payne said. “And you have to really oppose it intensively because there are people around you, hired with the best of intentions … who are trained to brush lint off clothes, straighten hair, erase face blemishes, and I just think, ‘Why?’ And then you have to fight against Kodak film stock – we’re mostly shooting Fuji on this one – and against lenses that make things look too pretty.

“Now, having said that, this film is going to be a lot more beautiful than my previous films have been because of the locales. It’s pretty. And it’s a bit more of a romantic film, at least it’s kind of turning out that way.”

Dailies from the first few weeks of shooting confirm a warm golden hue in interior and exterior colors, which may come as a relief to critics who’ve decried the heretofore dull, flat, washed-out look of his work.

Not to be confused with dramadies, a hybrid form languishing in limbo between lame comedy and pale drama, Payne films resemble more the sublime bittersweet elegies of, say, James L. Brooks and the late Billy Wilder. Like these artists, he does not so much distinguish between comedy and drama as embrace these ingredients as part of the same flavorful stew, the savory blending with the pungent, each accenting the other. With the possible exception of Schmidt, which as London said – in paraphrasing Payne – “defaulted to drama,” Payne films use comedy and drama as intrinsic, complementary lenses on human nature.

“I don’t separate them. It’s all just what it is,” Payne said. “I tend to make comedies based in painful human situations that are filled with ferocious emotions. I find ferocious emotions exciting. The actor and director have to trust the writer that the absurdity or the comedy is there in the writing. You all know it’s there, but you don’t play it.

“Sometimes, I think, in my films I’ve so not wanted to play the comedy of it that it gets too subtle, where then people don’t get that it’s funny. I mean, some do, like my friends. Like I think people tookAbout Schmidt much too seriously sometimes, and I don’t know if it’s because they’re Americans and Americans are literal and non-ironic, or what. I’m also afraid of being too broad … of having caricatures. Not so much on this film, but on previous films.”

It should come as no surprise then that Payne and writing partner Jim Taylor, with whom he adapted the Sideways screenplay from the unpublished Rex Pickett novel of the same name, draw on characters’ angst as the wellspring for their humor since tragedy is just the other side of comedy, and vice versa.

Payne’s finally leaving Nebraska to film was inevitable.

Tempted as he is to go elsewhere, including his ancestral homeland of Greece, he said, “I don’t think I would have been prepared to shoot in California or anywhere had I not first shot in Nebraska.”

Despite proclamations he would not film here again for awhile, he may return as soon as next fall to direct a screenplay set in north-central Nebraska. It, too, is about a journey. It chronicles an old man under the delusion he is a winner in the Ed McMahon sweepstakes. Enlisting his reluctant son as his driver, the man sets off on a quest from his home in Billings, Mont., to claim his “winnings” at the home office in Lincoln, Neb.

Along the way, the two get sidetracked — first, in Rapid City, S.D., and then in rural Nebraska, where the codger revisits the haunts and retraces the paths of his youth, meeting up with a Jaramusch-esque band of eccentric Midwesterners. Payne plans shooting in black-and-white Cinemascope.

“I’m happy to come back to Nebraska,” he said, adding, “You know, I feel like Michael Corleone – every time you try to get out, they just pull you right back in.”

Payne’s clearly here to stay, just as his connection to Nebraska, where he may direct an opera, remains indelible. After dinner he gives me a ride back to my motel in his new white convertible sports car, handling the curves with aplomb.

There’s an ebb and flow to a working movie crew. Everybody has a job to do, from the Teamsters grips and gaffers to the ADs and PAs to the personal assistants to the heads of wardrobe, makeup, et cetera. As a set-up is prepared, a flurry of activity unfolds on top of each other, each department’s crew attending to its duties at the same time, including dressing the set, rigging lights, changing lenses, loading film, laying track, moving the dolly.Amid all this movement and noise, Payne goes about conferring with actors or discussing the shot with his DP or else squirrels himself away to focus on his shot list. A palpable energy builds until the time shooting commences, when nonessential personnel pull back to the sidelines and calls for “Quiet” enforce a collective hush and rigid stillness over the proceedings. As the take plays out, an anticipatory buzz charges the air and when “Cut” is heard, the taut cast and crew are released in a paroxysm of relaxation.Chalk it up to his Greek heritage or to some innate humanism, but Payne creates a warm, communal atmosphere around him that, combined with his magnetic, magnanimous “je ne sais quoi” quotient, engenders fierce devotion from staff.Evan Endicott, a personal assistant and aspiring director, said, “I really don’t want to work for anyone else.”

Tracy Boyd, a factotum with feature aspirations, noted, “Alexander always pays attention to the process of the whole family of collaborators that go into making the film. His sets reflect a whole lifestyle.”

My challenge proves staying out of the way while still watching everything going on. The first couple of days, I sense the crew views me as a curiosity to be tolerated. I feel like an interloper. By the end of my stay I feel I blend in as another crewmate, albeit a green one. I become one with the set.

Payne periodically comes up to me, asking, “What do you find interesting?” or “Are you getting what you need?”

I tell him it’s all instructive – the waiting, the setups, the camera moves, the takes – fun, fascinating, exhausting, exhilarating all in one.

Wednesday morning Erik drives us, via the Santa Rosa Road, to the Sanford Winery, a rustic spot nestled among melon fields and wildflower meadows on one side and gentle hills on the other. The landscape has a muted beauty. The small tasting room, with its Old Westy outpost look, and its charismatic pourer, Chris Burroughs, with his shoulder-length hair, Stetson hat and American Indian jewelry, appear in a scene where Miles tries educating Jack about wine etiquette, only to have his buddy commit the unpardonable sin of “tasting” wines while chewing gum.

Sanford is famous for its Pinot Noir, the variety about which Miles is most passionate about.

It was here and at other wineries Payne visited in prepping the film that he, like Pickett before him, discovered California’s wine culture. On our visit, it isn’t long before spirited discussions ensue between Chris and customers on the mystique of wine characteristics, vintages, blends, trends and tastes.

Rejoining the production, I’m deposited in the town of Los Olivos for three days and nights of shooting in and around the Los Olivos Cafe. Space is tight inside the eatery, with crew, cameras, lighting and sound mixer Jose Antonio Garcia’s audio cart crammed around the fixtures. For this sequence, which finds “the boys” meeting two women for a let’s-get-to-know-you dinner and drinks icebreaker, Payne breaks up the shooting into segments – from Jack forcing Miles to screw up his courage to their entrance to joining the girls at the table to the foursome exchanging small talk. Payne later pulls the camera in tight to pick up a series of reaction shots and inserts for his “mosaic” of a montage that will chart the progression of the evening and of Miles’ panic. As this is played without sound, Payne directs the actors as they improvise before the camera, tweaking things along the way. Much attention is paid to the moments when the drunk Miles shambles off to the rest room and, slipping over “to the dark side,” detours to a pay phone to make an ill-advised call to his ex-wife, before arriving back shit-faced.

Like any experience bringing people together in a close, intense way, a film set is replete with affairs and alliances emerging from the shared toil and passion. Cliques form. Asides whispered. Inside jokes exchanged.

Payne and his new bride, Oh, one of Sideways’ two female leads, manage being discreetly frisky. While he shows remarkable equanimity in interacting with everybody, he keeps around him a small stable of trusted aides in whom he confides.