Archive

Life Itself XVI: Social justice, civil rights, human services, human rights, community development stories

Life Itself XVI:

Social justice, civil rights, human services, human rights, community development stories

Unequal Justice: Juvenile detention numbers are down, but bias persists

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/09/unequal-justice-…ut-bias-persists

To vote or not to vote

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/06/01/to-vote-or-not-to-vote/

North Omaha rupture at center of PlayFest drama

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/04/30/north-omaha-rupt…f-playfest-drama/

Her mother’s daughter: Charlene Butts Ligon carries on civil rights legacy of her late mother Evelyn Thomas Butts

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/28/her-mothers-daug…lyn-thomas-butts/

Brenda Council: A public servant’s life

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/26/brenda-council-a…ic-servants-life

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/11/17/the-urban-league…-strong-in-omaha/

Park Avenue Revitalization and Gentrification: InCommon Focuses on Urban Neighborhood

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/02/25/park-avenue-revi…ban-neighborhood/

Health and healing through culture and community

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/11/17/health-and-heali…re-and-community

Syed Mohiuddin: A pillar of the Tri-Faith Initiative in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/09/01/syed-mohiuddin-a…tiative-in-omaha

Re-entry prepares current and former incarcerated individuals for work and life success on the outside

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/10/re-entry-prepare…s-on-the-outside/

Frank LaMere: A good man’s work is never done

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/07/11/frank-lamere-a-g…rk-is-never-done

Behind the Vision: Othello Meadows of 75 North Revitalization Corp.

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/27/behind-the-visio…italization-corp

North Omaha beckons investment, combats gentrification

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/25/north-omaha-beck…s-gentrification

SAFE HARBOR: Activists working to create Omaha Area Sanctuary Network as refuge for undocumented persons in danger of arrest-deportation

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/29/safe-harbor-acti…rest-deportation

Heartland Dreamers have their say in nation’s capitol

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/24/heartland-dreame…-nations-capitol/

Of Dreamers and doers, and one nation indivisible under…

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/21/of-dreamers-and-…ndivisible-under/

Refugees and asylees follow pathways to freedom, safety and new starts

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/21/refugees-and-asy…y-and-new-starts

Coming to America: Immigrant-Refugee mosaic unfolds in new ways and old ways in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/10/coming-to-americ…ld-ways-in-omaha

History in the making: $65M Tri-Faith Initiative bridges religious, social, political gaps

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/25/history-in-the-m…l-political-gaps

A systems approach to addressing food insecurity in North Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/08/11/a-systems-approa…y-in-north-omaha

No More Empty Pots Intent on Ending North Omaha Food Desert

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/13/no-more-empty-po…t-in-north-omaha

Poverty in Omaha:

Breaking the cycle and the high cost of being poor

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/01/03/poverty-in-omaha…st-of-being-poor/

Down and out but not done in Omaha: Documentary surveys the poverty landscape

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/11/03/down-and-out-but…overty-landscape

Struggles of single moms subject of film and discussion; Local women can relate to living paycheck to paycheck

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/10/24/the-struggles-of…heck-to-paycheck

Aisha’s Adventures: A story of inspiration and transformation; homelessness didn’t stop entrepreneurial missionary Aisha Okudi from pursuing her goals

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/07/10/aisha-okudis-sto…rsuing-her-goals

Omaha Community Foundation project assesses the Omaha landscape with the goal of affecting needed change

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/10/omaha-community-…ng-needed-change/

Nelson Mandela School Adds Another Building Block to North Omaha’s Future

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/01/24/nelson-mandela-s…th-omahas-future

Partnership 4 Kids – Building Bridges and Breaking Barriers

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/06/03/partnership-4-ki…reaking-barriers

Changing One Life at a Time: Mentoring Takes Center Stage as Individuals and Organizations Make Mentoring Count

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/01/05/changing-one-lif…-mentoring-count/

Where Love Resides: Celebrating Ty and Terri Schenzel

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/02/where-love-resid…d-terri-schenzel/

North Omaha: Voices and Visions for Change

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/29/north-omaha-voic…sions-for-change

Black Lives Matter: Omaha activists view social movement as platform for advocating-making change

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/08/26/black-lives-matt…ng-making-change

Change in North Omaha: It’s been a long time coming for northeast Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/08/01/change-in-north-…-northeast-omaha/

Girls Inc. makes big statement with addition to renamed North Omaha center

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/23/girls-inc-makes-…rth-omaha-center

NorthStar encourages inner city kids to fly high; Boys-only after-school and summer camp put members through their paces

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/06/17/northstar-encour…ough-their-paces/

Big Mama, Bigger Heart: Serving Up Soul Food and Second Chances

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/10/17/big-mama-bigger-…d-second-chances/

When a building isn’t just a building: LaFern Williams South YMCA facelift reinvigorates community

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/08/03/when-a-building-…-just-a-building/

Identity gets new platform through RavelUnravel

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/03/20/identity-gets-a-…ugh-ravelunravel/

Where Hope Lives, Hope Center for Kids in North Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/where-hope-lives…s-in-north-omaha/

Crime and punishment questions still surround 1970 killing that sent Omaha Two to life in prison

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/03/30/crime-and-punish…o-life-in-prison/

A WASP’s racial tightrope resulted in enduring book partially set in 1960s Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/28/a-wasps-racial-t…t-in-1960s-omaha/

Gabriela Martinez:

A heart for humanity and justice for all

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/08/16878

Father Ken Vavrina’s new book “Crossing Bridges” charts his life serving others

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/29/father-ken-vavri…e-serving-others/

Wounded Knee still battleground for some per new book by journalist-author Stew Magnuson

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/04/20/wounded-knee-sti…or-stew-magnuson

‘Bless Me, Ultima’: Chicano identity at core of book, movie, movement

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/09/14/bless-me-ultima-…k-movie-movement

Finding Normal: Schalisha Walker’s journey finding normal after foster care sheds light on service needs

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/07/18/finding-normal-s…on-service-needs/

Dick Holland remembered for generous giving and warm friendship that improved organizations and lives

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/08/dick-holland-rem…ations-and-lives/

Justice champion Samuel Walker calls It as he sees it

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/30/justice-champion…it-as-he-sees-it

![[© Ellen Lake]](https://i0.wp.com/www.crmvet.org/crmpics/64fs_gulfport1.jpg)

Photo caption:

Walker on far left of porch of a Freedom Summer

El Puente: Attempting to bridge divide between grassroots community and the system

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/22/el-puente-attemp…y-and-the-system

All Abide: Abide applies holistic approach to building community; Josh Dotzler now heads nonprofit started by his parents

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/12/05/all-abide-abide-…d-by-his-parents/

Making Community: Apostle Vanessa Ward Raises Up Her North Omaha Neighborhood and Builds Community

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/13/making-community…builds-community/

Collaboration and diversity matter to Inclusive Communities: Nonprofit teaches tools and skills for valuing human differences

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/09/collaboration-an…uman-differences

Talking it out: Inclusive Communities makes hard conversations the featured menu item at Omaha Table Talk

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/02/talking-it-out-i…omaha-table-talk/

Everyone’s welcome at Table Talk, where food for thought and sustainable race relations happen over breaking bread together

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/16/everyones-welcom…g-bread-together/

Feeding the world, nourishing our neighbors, far and near: Howard G. Buffett Foundation and Omaha nonprofits take on hunger and food insecurity

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/11/22/feeding-the-worl…-food-insecurity

Rabbi Azriel: Legacy as social progressive and interfaith champion secure

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/15/rabbi-azriel-leg…-champion-secure

Rabbi Azriel’s neighborhood welcomes all, unlike what he saw on recent Middle East trip; Social justice activist and interfaith advocate optimistic about Tri-Faith campus

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/09/06/rabbi-azriels-ne…tri-faith-campus/

Ferial Pearson, award-winning educator dedicated to inclusion and social justice, helps students publish the stories of their lives

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/25/ferial-pearson-a…s-of-their-lives/

Upon This Rock: Husband and Wife Pastors John and Liz Backus Forge Dynamic Ministry Team at Trinity Lutheran

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/02/upon-this-rock-h…trinity-lutheran/

Gravitas – Gravity Center for Contemplative Activism founders Christopher and Phileena Heuertz create place of healing for healers

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/04/01/gravitas-gravity…ling-for-healers/

Art imitates life for “Having Our Say” stars, sisters Camille Metoyer Moten and Lanette Metoyer Moore, and their brother Ray Metoyer

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/05/art-imitates-lif…ther-ray-metoyer

Color-blind love:

Five interracial couples share their stories

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/06/color-blind-love…re-their-stories

A Decent House for Everyone: Jesuit Brother Mike Wilmot builds affordable homes for the working poor through Gesu Housing

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/09/a-decent-house-f…ugh-gesu-housing

Bro. Mike Wilmot and Gesu Housing: Building Neighborhoods and Community, One House at a Time

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/04/27/bro-mike-wilmot-…-house-at-a-time/

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/04/01/omaha-native-ste…of-omaha-central/

Anti-Drug War manifesto documentary frames discussion:

Cost of criminalizing nonviolent offenders comes home

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/02/01/an-anti-drug-war…nders-comes-home

Documentary shines light on civil rights powerbroker Whitney Young: Producer Bonnie Boswell to discuss film and Young

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/03/21/documentary-shin…e-film-and-young

Civil rights veteran Tommie Wilson still fighting the good fight

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/05/07/civil-rights-vet…g-the-good-fight

Rev. Everett Reynolds Gave Voice to the Voiceless

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/18/rev-everett-reyn…to-the-voiceless/

Lela Knox Shanks: Woman of conscience, advocate for change, civil rights and social justice champion

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/04/lela-knox-shanks…ocate-for-change

Omahans recall historic 1963 march on Washington

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/12/omahans-recall-h…ch-on-washington

Psychiatrist-Public Health Educator Mindy Thompson Fullilove Maps the Root Causes of America’s Inner City Decline and Paths to Restoration

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/04/psychiatrist-pub…s-to-restoration/

A force of nature named Evie:

Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/16/a-force-of-natur…e-advocate-at-99

Home is where the heart Is for activist attorney Rita Melgares

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/20/home-is-where-th…ey-rita-melgares/

Free Radical Ernie Chambers subject of new biography by author Tekla Agbala Ali Johnson

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/12/05/free-radical-ern…bala-ali-johnson

Carolina Quezada leading rebound of Latino Center of the Midlands

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/03/carolina-quezada…-of-the-midlands/

Returning To Society: New community collaboration, research and federal funding fight to hold the costs of criminal recidivism down

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/02/returning-to-soc…-recidivism-down

Getting Straight: Compassion in Action expands work serving men, women and children touched by the judicial and penal system

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/05/22/getting-straight…and-penal-system

OneWorld Community Health: Caring, affordable services for a multicultural world in need

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/09/oneworld-communi…al-world-in-need

Dick Holland responds to far-reaching needs in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/dick-holland-res…g-needs-in-omaha/

Gender equity in sports has come a long way, baby; Title IX activists-advocates who fought for change see much progress and the need for more

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/06/11/gender-equity-in…he-need-for-more/

Giving kids a fighting chance: Carl Washington and his CW Boxing Club and Youth Resource Center

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/12/03/giving-kids-a-fi…-resource-center/

Beto’s way: Gang intervention specialist tries a little tenderness

http://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/28/betos-way-gang-i…ittle-tenderness/

Saving one kid at a time is Beto’s life work

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/01/24/saving-one-kid-a…-betos-life-work

Community trumps gang in Fr. Greg Boyle’s Homeboy model

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/21/community-trumps…es-homeboy-model/

Born again ex-gangbanger and pugilist, now minister, Servando Perales makes Victory Boxing Club his mission church for saving youth from the streets

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/12/19/born-again-ex-ga…from-the-streets/

Turning kids away from gangs and toward teams in South Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/17/turning-kids-awa…s-in-south-omaha/

“Paco” proves you can come home again

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/09/paco-proves-you-…-come-home-again

Two graduating seniors fired by dreams and memories, also saddened by closing of school, St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/05/11/two-graduating-s…igh-in-omaha-neb/

St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High: A school where dreams matriculate

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/st-peter-claver-…eams-matriculate/

Open Invitation: Rev. Tom Fangman engages all who seek or need at Sacred Heart Catholic Church

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/01/09/an-open-invitati…-catholic-church/

Outward Bound Omaha uses experiential education to challenge and inspire youth

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/26/outward-bound-om…nd-inspire-youth

After steep decline, the Wesley House rises under Paul Bryant to become youth academy of excellence in the inner city

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/27/after-a-steep-de…n-the-inner-city

Freedom riders: A get on the bus inauguration diary

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/10/21/get-on-the-bus-a…-ride-to-freedom/

The Great Migration comes home: Deep South exiles living in Omaha participated in the movement author Isabel Wilkerson writes about in her book, “The Warmth of Other Suns”

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/03/31/the-great-migrat…th-of-other-suns/

When New Horizons dawned for African-Americans seeking homes in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/01/17/when-new-horizon…ericans-in-omaha/

Good Shepherds of North Omaha: Ministers and churches making a difference in area of great need

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/04/the-shepherds-of…ea-of-great-need

Academy Award-nominated documentary “A Time for Burning” captured church and community struggle with racism

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/12/15/a-time-for-burni…ggle-with-racism/

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/03/08/letting-1000-flo…in-the-maelstrom

Coloring History:

A long, hard road for UNO Black Studies

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/25/coloring-history…no-black-studies

Two Part Series: After Decades of Walking Behind to Freedom, Omaha’s African-American Community Tries Picking Up the Pace Through Self-Empowered Networking

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/13/two-part-series-…wered-networking

Power Players, Ben Gray and Other Omaha African-American Leaders Try Improvement Through Self-Empowered Networking

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/09/power-players-be…wered-networking/

Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/04/native-omahans-t…n-their-hometown

Overarching plan for North Omaha development now in place: Disinvested community hopeful long promised change follows

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/29/overarching-plan…d-change-follows/

Standing on Faith, Sadie Bankston Continues One-Woman Vigil for Homicide Victim Families

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/standing-on-fait…-victim-families/

Forget Me Not Memorial Wall

North Omaha champion Frank Brown fights the good fight

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/01/15/north-omaha-cham…s-the-good-fight/

Man on fire: Activist Ben Gray’s flame burns bright

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/09/02/ben-gray-man-on-fire/

Strong, Smart and Bold, A Girls Inc. Success Story

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/strong-smart-and…-girls-inc-story

What happens to a dream deferred?

John Beasley Theater revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun”

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/14/what-happens-to-…aisin-in-the-sun

Brown v. Board of Education:

Educate with an Even Hand and Carry a Big Stick

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/07/brown-v-board-of…arry-a-big-stick/

Fast times at Omaha’s Liberty Elementary: Evolution of a school

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/05/fast-times-at-om…tion-of-a-school/

New school ringing in Liberty for students

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/06/new-school-ringi…rty-for-students

Nancy Oberst: Pied Piper of Liberty Elementary School

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/06/nancy-oberst-the…lementary-school/

Tender Mercies Minister to Omaha’s Poverty Stricken

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/tender-mercies-m…poverty-stricken/

Community and coffee at Omaha’s Perk Avenue Cafe

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/community-and-co…perk-avenue-cafe/

Whatsoever You Do to the Least of My Brothers, that You Do Unto Me: Mike Saklar and the Siena/Francis House Provide Tender Mercies to the Homeless

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/01/whatsoever-you-d…t-you-do-unto-me/

Gimme Shelter: Sacred Heart Catholic Church Offers a Haven for Searchers

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/gimme-shelter-sa…en-for-searchers

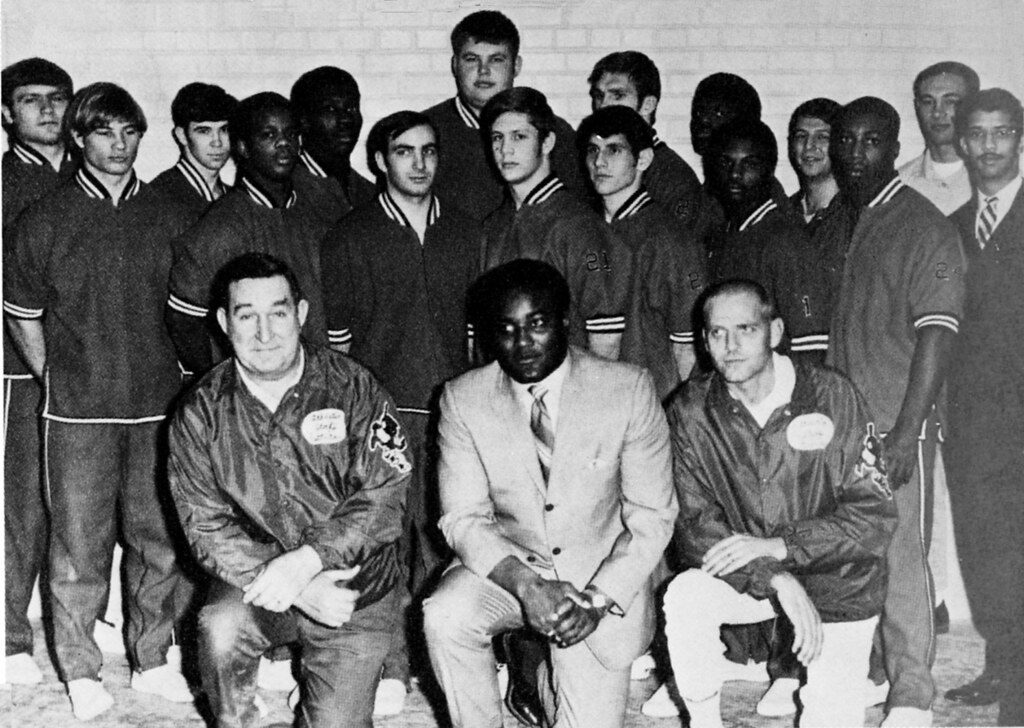

UNO wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/03/17/uno-wrestling-dy…-social-change-2

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/02/a-brief-history-…apher-rudy-smith/

Hidden In plain view: Rudy Smith’s camera and memory fix on critical time in struggle for equality

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/hidden-in-plain-…gle-for-equality/

Small but mighty group proves harmony can be forged amidst differences

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/11/14/small-but-mighty…idst-differences/

Winners Circle: Couple’s journey of self-discovery ends up helping thousands of at-risk kids through early intervention educational program

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/couples-journey-…-of-at-risk-kids

A Mentoring We Will Go

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/18/a-mentoring-we-will-go

Abe Sass: A mensch for all seasons

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/02/abe-sass-a-mensch-for-all-seasons

Shirley Goldstein: Cream of the Crop – one woman’s remarkable journey in the Free Soviet Jewry movement

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/05/shirley-goldstei…t-jewry-movement/

Flanagan-Monsky example of social justice and interfaith harmony still shows the way seven decades later

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/flanagan-monsky-…y-60-years-later/

A Contrary Path to Social Justice: The De Porres Club and the fight for equality in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/01/a-contrary-path-…quality-in-omaha/

Hey, you, get off of my cloud! Doug Paterson is acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed founder Augusto Boal and advocate of art as social action

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/03/hey-you-get-off-…as-social-action/

Doing time on death row: Creighton University theater gives life to “Dead Man Walking”

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/01/10/doing-time-on-de…dead-man-walking/

“Walking Behind to Freedom” – A musical theater examination of race

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/21/walking-behind-t…mination-of-race/

Bertha’s Battle: Bertha Calloway, the Grand Lady of Lake Street, struggles to keep the Great Plains Black History Museum afloat

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/11/berthas-battle

Leonard Thiessen social justice triptych deserves wider audience

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/01/21/leonard-thiessen…s-wider-audience/

Gabriela Martinez: A heart for humanity and justice for all

Gabriela Martinez: A heart for humanity and justice for all

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in a February 2018 issue of El Perico ( http://el-perico.com/ )

Like many young Omaha professionals, Gabriela Martinez is torn between staying and spreading her wings elsewhere.

The 2015 Creighton University social work graduate recently left her position at Inclusive Communities to embark on an as yet undefined new path. This daughter of El Salvadoran immigrants once considered becoming an immigration lawyer and crafting new immigration policy. She still might pursue that ambition, but for now she’s looking to continue the diversity and inclusion work she’s already devoted much of her life to.

Unlike most 24-year-olds. Martinez has been a social justice advocate and activist since childhood. She grew up watching her parents assist the Salvadoran community, first in New York, where her family lived, and for the last two decades in Omaha.

Her parents escaped their native country’s repressive regime for the promise of America. They were inspired by the liberation theology of archbishop Oscar Romero, who was killed for speaking out against injustice. Once her folks settled in America, she said, they saw a need to help Salvadoran emigres and refugees,

“That’s why they got involved. They wanted to make some changes, to try to make it easier for future generations and to make it easier for new immigrants coming into this country.”

She recalls attending marches and helping out at information fairs.

In Omaha, her folks founded Asociación Cívica Salvadoreña de Nebraska, which works with Salvadoran consulates and partners with the Legal immigrant Center (formerly Justice for Our Neighbors). A recent workshop covered preparing for TPS (Temporary Protected Status) ending in 2019.

“They work on getting people passports, putting people in communication with Salvadoran officials. If someone is incarcerated, they make sure they know their rights and they’re getting access to who they need to talk to.”

Martinez still helps with her parents’ efforts, which align closely with her own heart.

“I’m very proud of my roots,” she said. “My parents opened so many doors for me. They got me involved. They instilled some values in me that stuck with me. Seeing how hard they work makes me think I’m not doing enough. so I’m always striving to do more and to be the best version of myself that I can be because that’s what they’ve worked their entire lives for.”

Martinez has visited family in El Salvador, where living conditions and cultural norms are in stark contrast to the States.

She attended an Inclusive Communities camp at 15, then became a delegate and an intern, before being hired as a facilitator for the nonprofit’s Table Talk series around issues of racism and inequity. She enjoyed “planting seeds for future conversations” and “giving a voice to people who think they don’t have one.”

Inclusive Communities fostered personal growth.

“People I went to camp with are now on their way to becoming doctors and lawyers and now they’re giving back to the community. I’m most proud of the youth I got to work with because they taught me as much as I taught them and now I see them out doing the work and doing it a thousand times better than I do.

“I love seeing how far they’ve come. Individuals who were quiet when I first met them are now letting their voices be heard.”

Martinez feels she’s made a difference.

“I love seeing the impact I left on the community – how many individuals I got to facilitate in front of and programs I got to develop.”

She’s worked on Native American reservations, participated in social justice immersion trips and conferences and supported rallies.

“I’m most proud when I see other Latinos doing the work and how passionate they are in being true to themselves and what’s important to them. There’s a lot of strong women who have taken the time to invest in me. Someone I really look up to for her work in politics is Marta Nieves (Nebraska Democratic Party Latino Caucus Chair). I really appreciate Marta’s history working in this arena.”

Martinez is encouraged that Omaha-transplant Tony Vargas has made political inroads, first on the Omaha School Board, and now in the Nebraska Legislature.

As for her own plans, she said, “I’m being very intentional about making sure my next step is a good fit and that i’m wanting to do the work not because of the money but because it’s for a greater good.”

Though her immediate family is in Omaha, friends have pursued opportunities outside Nebraska and she may one day leave to do the same.

“I’d like to see what I can accomplish in Omaha, but I need a bigger city and I need to be around more diversity and people from different backgrounds and cultures that I can learn from. I think Omaha is too segregated.”

Like many millennials, she feels there are too many barriers to advancement for people of color here.

“This community is still heavily dominated by non-people of color.”

Wherever she resides, she said “empowering and advocating” for underserved people “to be heard in different spaces”.will be core to her work.

Despite gains made in diversity and inclusion, she feels America still has a long way to go. She’s seen too many workplaces let racism-sexism slide and too many environments where individuals reporting discrimination are told they’re “overreacting” or “too ‘PC.'” That kind of dismissive attitude, she said, cannot stand and she intends to be a voice for those would be silenced.

Her mother’s daughter: Charlene Butts Ligon carries on civil rights legacy of her late mother Evelyn Thomas Butts

Her mother’s daughter:

Charlene Butts Ligon carries on civil rights legacy of her late mother Evelyn Thomas Butts

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in February 2018 issue of the New Horizons

Chances are, you’ve never heard of the late Evelyn T. Butts. But you should know this grassroots warrior who made a difference at the height of the civil rights movement in the Jim Crow American South.

A new book, Fearless: How a poor Virginia seamstress took on Jim Crow, beat the poll tax and changed her city forever, written by her youngest daughter, Charlene Butts Ligon of Bellevue, Neb. preserves the legacy of this champion for the underserved and underrepresented.

Defying odds to become civil rights champion

Evelyn (Thomas) Butts grew up with few advantages in Depression Era Virginia. She lost her mother at 10. She didn’t finish high school. Her husband Charlie Butts came home from World War II one hundred percent disabled. To support their three daughters, Butts, a skilled seamstress, took in day work. She made most of her girls’ clothes.

When not cooking, cleaning, caring for the family, she volunteered her time fighting for equal rights, She became an unlikely force in Virginia politics wielding influence in her hometown of Norfolk and beyond. Both elected officials and candidates curried her favor.

She fought for integrated schools, equal city services and fair housing. Her biggest fight legally challenged the poll tax, a registration fee that posed enough of a financial burden to keep many poor blacks from exercising their right to cast a ballot. The Twenty-fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had ruled poll taxes illegal in federal elections but the practice continued in southern state elections as a way to disenfranchise blacks. Butts’ case, combined with others. made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. in 1966, Thurgood Marshall argued for the plaintiffs. In a 6-3 decision, the court abolished the poll tax in state elections and Butts went right to work registering thousands of voters.

Devoted daughter documents mom’s legacy in book

More than 50 years since that decision and 25 years since her mother’ death in 1993, Ligon has written and published a book that chronicles Evelyn Butts’ life of public service that inspired her and countless others.

Ligon and her husband Robert are retired U.S. Air Force officers. The last station of their well-traveled military careers was at Offutt Air Force Base from 1992 to 1995. When they retired, the couple opted to make Nebraska their permanent home. They are parents to three grown children and five grandchildren.

By nature and nurture, Ligon, inherited her “mama’s” love of organized politics, community affairs and public service. She’s chair of the Sarpy County Democrats and secretary of the Nebraska State Democratic Party. As the party’s state caucus chair, she led a nationally recognized effort that set up caucuses in all 93 counties and developed an interactive voting info website.

Former Nebraska Democratic Party executive director Hadley Richters knows a good egg when she sees one.

“In politics, you learn quickly the people who will actually do the work are few, and even fewer are those who strive to do it even better than before. Charlene Ligon is definitely a part of that very few. I have also learned those few, like Charlene, are who truly uphold our democracy. Charlene works tirelessly to further participation in the process, selflessly driven by rare and deep understanding of what’s at stake. She is a champion for voices to be heard, and when it comes to protecting the democratic process, defending fairness, demanding access, and advocating for what is right, I can promise you Charlene will be present, consistent, hard-working and fearless.”

Ligon is a charter member of Black Women for Positive Change, a national policy-focused network whose goals are to strengthen and expand the American middle-working class and change the culture of violence.

Besides her mother, she counts as role models: Barbara Jordan, Shirley Chisholm and Dorothy Height.

In addition to participating in lots of political rallies, she’s an annual Omaha Women’s March participant.

Like her mother before her. she’s been a Democratic National Convention delegate, she’s met party powerbrokers and she’s made voting rights her mission.

“It all goes back to that – access and fairness. That’s how I see it.”

Even today, measures such as redistricting and extreme voter ID requirements can be used to suppress votes. She still finds it shocking the lengths Virginia and other states went to in order to suppress the black vote.

“Virginia’s really shameful in the way it did voting,” she said. “At one time, they had what they called a blank sheet for registration. When you went to register to vote you had to know ahead of time what identifying information you needed to put on there. It wasn’t a literacy test. By law, the registrar could not help people, so people got disqualified. Well, the black community got together and started having classes to educate folks what they needed to know when they went to register.”

The blank sheet was on top of the poll tax. An unintended effect was the disqualification of poor and elderly whites, too. In a majority white state, that could not hold and so a referendum was organized and the practice discontinued.

“The history books tell you they did it because of white backlash, not because of black backlash,” Ligon said.

Virginia’s regerettable record of segregation extended to entire school districts postponing school and some schools closing rather than complying with integration

“It always amazes me they did that,” she said.

Speaking her mind and giving others a voice

As a Norfolk public housing commissioner, Butts broke ranks with fellow board members to publicly oppose private and public redevelopment plans whose resulting gentrification would threaten displacing black residents.

“She really gave them a fit because they weren’t doing what they should have been doing for poor neighborhoods and she told them about it. They weren’t really ready for her to bring this out,” Ligon said of her mother’s outspoken independence.

“Mama could be stubborn, too. She was authoritarian sometimes.”

Butts became the voice for people needing an advocate.

“They called her for all kinds of things. They called her when they needed a house, when they were having problems with their landlord. They called her and called her. They knew to call Mrs. Butts and that if you call Mrs. Butts, she’ll help you. Nine times out of ten she could get something for them. She had that reputation as a mover and shaker and they knew she wasn’t going to sell them out because it wasn’t about money for her.”

Ligon fights the good fight herself in a different climate than the one her mother operated in. It makes her appreciate even more how her mom took on social issues when it was dangerous for an African-American to speak out. She admires the courage her mother showed and the feminist spirit she embodied.

“My mama always spoke up. She didn’t cow. She talked kind of loud. I got that from her. She looked them in the eye and said, ‘Yeah, this is the way it needs to be.’ They didn’t always pay attention to her, but she just always was ready to say what needed to be said. Of course, the establishment didn’t want to hear it. But she actually won most people’s respect.”

Growing up, Ligon realized having such a bigger-than-life mother was not the norm.

“She stood out in my life. I started to understand that my mom was different than most people’s moms. She was always doing something for the neighborhood. There were so many things going on in the 1950s through the early 1960s that really got her going.”

Her mother was at the famous 1963 March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. Charlene wanted to go but her mother forbade it out of concern there might be violence. Being there marked a milestone for Evelyn – surpassed only by the later Supreme Court victory.

“It meant a lot to her. That was the movement. That was what she believed,” Ligon said. “And it was historic.”

Long before the march, Butts saw MLK speak in Petersburg, Virginia. He became her personal hero.

“She was already moving forward, but he inspired her to move further forward.”

Decades later, Ligon attended both of Obama’s presidential inaugurations. She has no doubt her mother would have been there if she’d been alive.

“I wish my mom could have been around to see that, although electing the nation’s first black president didn’t have the intended effect on America I thought it would. It gave me faith though when he was elected that the process works, that it could happen. He could not have won with just black votes, so we know a lot of white people voted for him. We should never forget that.

“It just really made me proud.”

Ligon shook hands with President Obama when he visited the metro. She’s met other notable Democrats, such as Joe Biden, Hilary Clinton, Bill Clinton, Jim Clybern, Doug Wilder, Ben Nelson and Bob Kerrey.

The day the Supreme Court struck down the poll tax, her mother got to meet Thurgood Marshall – the man who headed up the Brown vs. Board of Education legal team that successfully argued for school desegregation.

“She was really thrilled to meet him.”

Then-U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy was in the courtroom for the poll tax ruling and Evelyn got to meet the future presidential candidate that day as well.

Butts was vociferous in her pursuit of justice but not everyone in the movement could afford to be like her.

“As I look back on the other prominent people in the movement,” Ligon said, “they had their ways of contributing but there were a lot of people who had what they considered something to lose. For instance, teachers just wouldn’t say a word because they were afraid for their jobs. There were lots of people that wouldn’t say anything.”

Her mother exuded charisma that drew people to her.

“People liked her. Mama was an organizer. She was the person that got them all together and she was inspirational to them, I’m sure. She had a group of ladies who followed her. They were like, “Okay. Mrs. Butts, what are we going to do today? Are we going to register voters? Are we going to picket?”

Evelyn Butts formed an organization called Concerned Citizens for Political Education that sought to empower blacks and their own self-determination. It achieved two key victories in the late 1960s with the election of Joseph A. Jordan as Norfolk’s first black city council member since Reconstruction and electing William P. Robinson as the city’s first African-American member of the state House of Delegates.

Charlene marveled at her mother’s energy and industriousness.

“I was always proud of her.”

Having such a high profile parent wasn’t a problem.

“I never felt uncomfortable or had a negative feeling about it.”

Even when telling others what she felt needed to be done, Ligon said her mother “treated everybody with respect,” adding “The Golden Rule has always been my thing and I’m sure my mom taught me the Golden Rule.”

Telling the story from archives and memories

As big a feat as it was to end the poll tax, Ligon felt her mother’s accomplishments went far beyond that and that only a book could do them justice. So, in 2007, she and her late sister Jeanette, embarked on the project.

“We thought people needed lo know the whole story.”

Ligon’s research led her to acclaimed journalist-author Earl Swift, a former Virginian Pilot reporter who wrote about her mother. He ended up editing the book. He insisted she make it more specific and full of descriptive details. Poring through archives, Ligon found much of her mother’s activities covered in print stories published by the Pilot as well as by Norfolk’s black newspaper, the New Journal and Guide. Ligon also interviewed several people who knew her mother or her work.

Writer Kietryn Zychal helped Ligon pen the book.

Much of the content is from Charlene and her sister’s vivid memories growing up with their mom’s activism. As a girl, Charlene often accompanied her to events.

“She took me a lot of places. I was exposed.”

Those experiences included picketing a local grocery store that didn’t hire blacks and a university whose athletics stadium restricted blacks to certain sections

“The first time i remember attending a political-social activism meeting with Mama was the Oakwood Civic League about 1955 during the same time the area was under annexation by the city of Norfolk. My next memory is attending the NAACP meeting at the church on the corner from our house concerning testing to attend integrated schools. I have vivid memories of attending the court proceedings of a school desegregation case. Mama took me to court every day. She was called to testify by the NAACP lawyers.”

Charlene joined other black teenage girls as campaign workers under the name the Jordanettes, for candidate Joe Jordan. Her mom made their matching outfits.

“We passed out literature, campaign buttons, bumper stickers at picnics, rallies and meetings. Hanging out with my mom and doing the campaign stuff definitely had an influence. I was always excited to tag along.”

At home, politics dominated family discussions.

“My mom did what she did all the time and she talked about it all the time, and so I always knew what was going on, She involved us. She would update my dad. We were always in earshot of the conversation. My sisters and I were expected to be aware of what was happening in our community. We were encouraged to read the newspaper. We participated in some picketing.”

Always having Evelyn’s back was the man of the house.

“He was behind her a hundred percent,” Ligon said of her father, who unlike Evelyn was quiet and reserved. He didn’t like the limelight but, Charlene said, “he never fussed about that – he was in her corner.”

“He might not have done that (activism) personally himself but yeah he was proud she was out there doing that. As long as she cooked his dinner.”

Because Evelyn Butts was churched, she saw part of her fighting the good fight as the Christian thing to do.

“We attended church but my mama wasn’t really a church lady. She just always believed in what the right thing to do would be. I guess that inner thing was in all of us as far as social justice.

“She taught me there wasn’t anything I couldn’t do if I put my mind to it. She taught me not to be afraid of people because I was different.”

When it came time for Ligon to title her book, the word fearless jumped out.

“That’s what she was.”

Where did that fearless spirit come from?

After her mother died, she was raised by her politically engaged aunt Roz. But headstrong Evelyn took her activism to a whole other level.

“I remember Roz telling mama to be careful. She said, ‘Evelyn, you better watch out, they’re going to kill you.'”

The threat of violence, whether implied or stated, was ever present.

“That’s just the way it was. In Virginia, we had some bad things happen, but it wasn’t like Mississippi and the civil rights workers getting killed. We had a few bombings and cross burnings. It still amazes me how she was able to put up with what she did. A lot of people were frightened. Not far from where we lived. racists were bombing houses near where she was picketing. She wasn’t frightened about that and she always made us feel comfortable that things were going to be okay.”

Butts drew the ire of those with whom she differed, white and black. For example, she called out the Virginia chapter of the NAACP for moving too slowly and timidly.

“My mom was considered militant back in the day, but she was also pragmatic about it. There was so much ground to cover. There’s still a lot of ground to cover.”

Progress won and lost in a never-ending struggle

Ligon rues that today’s youth may not appreciate how fragile civil rights are, especially with Donald Trump in office and the Republicans in control of Congress.

“I don’t think young people realize we’re losing ground. They aren’t paying attention. They take things for granted, I’m old enough to remember when everything was segregated and how restrictive it was. I may not want to go anywhere then someplace where all the people look like me, but I need to have that choice.

“We’ve lost almost all the ground we made when Barack Obama was president. People who wanted change said we don’t need the status quo and I would say, yes we do, we need to hold it a little bit.”

She’s upset Obama executive orders are under assail. Protections for DACA recipients are set to end pending a compromise plan. Obamacare is being undone. Sentences for nonviolent drug offenders are being toughened and lengthened.

Perhaps it’s only natural the nation’s eyes were taken off the prize once civil rights lost an identifiable movement or leader. But Ligon chose a Corretta Scott King quotation at the front of her book as a reminder that when it comes to preserving rights, vigilance is needed.

Struggle is a never ending process. Freedom is never really won –you earn it in every generation.

“I think the struggle is always going to be there for us minorities, specifically for African-Americans,” Ligon said. “It’s my belief we’re always going to have it. Each generation has to continue to move forward. You can’t just say, ‘We have it now.'”

She’s concerned some African-Americans have grown disillusioned by the overt racism that’s surfaced since Trump emerged as a serious presidential candidate and then won the White House.

“With the change that’s happened in the United States, I think a lot of them have lost faith. They seem to have given up. They say America is white people’s country. I remind them it’s our country. Do you know how much blood sweat and tears African-Americans have invested in America? Somewhere down the line we did not instill that this is our country. It’s okay to be patriotic and call them out every day. You can do both.”

How might America be different had MLK lived?

“Hopefully, we would be a little bit further along in having a more organized movement,” said Ligon.

She’s distressed a segment of whites feel the gains made by blacks have come at their expense.

“Some white people feel something has been taken from them and given to the minorities, which is sad, because it’s not really so. But they feel that way.”

She feels the election of Trump represented “a backlash” to the Obama presidency and his legacy as a progressive black man in power.

If her mother were around today, Charlene is sure she would be out registering voters and getting them to the polls to ensure Trump and those like him don’t get reelected or elected in the first place.

In her book’s epilogue, Charlene suggests people stay home from the polls because they believe politics is corrupt and dirty but she asserts Mama Butts would have something to say about that.

If my mother could, I know she’d say this: If you don’t vote, you can be assured that corrupt politicians will be elected.

“And that’s the truth,” Ligon said.

Drawing strength from a deep well

Just where did her mother get the strength to publicly resist oppression?

“It probably came from a long line of strong women. My grandmother’s sisters, including Roz, who raised my mom, and women from the generation before. The men, I suspect, were pretty strong too. You just had to know my mom and the other family ladies, and the conclusion would be something was in the genes that made them fighters. They were fighters, no doubt. They all were civic-minded, too.”

Going back even earlier in the family tree reveals a burning desire for freedom and justice.

“My great-great-grandfather Smallwood Ackiss was a slave who ran away from the plantation during the Civil War after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and went to Norfolk. He went on to fight for the Union for two years,” Ligon said. “In 1865, he came back to the plantation. John Ackiss II, who was the plantation owner and his owner, had been fighting for the Confederacy at the same time. We do know Smallwood was given 30 acres of land. He lost the property, but we still have a family cemetery there that’s now on a country club in a real exclusive area of Virginia Beach.”

From Smallwood right on down to her mother and herself, Charlene is part of a heritage that embraces freedom and full participation in the democratic process.

“I guess I was always interested and Mom always took me with her. I always saw it. Even in the military, when stationed in South Dakota, I chaired the NAACP Freedom Fund in Rapid City.

“It’s always been there.”

She feels her time in the service prepared her to take charge of things.

“The military strengthens leadership. It’s geared for you to get promoted to become a leader.”

Then there’s the fact she is her mother’s daughter.

Entering the service in the first place – as a 26-year-old single mother of two young children – illustrated her own strong-willed independence. It was 1975 and the newly initiated all-volunteer military was opening long-denied opportunities for women.

“I was divorced, had two kids and I needed child care and a regular salary. I didn’t want to have to depend on anyone else for it but me. It was difficult entering the military as a single parent, but I saw it as security for me and my kids. I was really fortunate I met a great guy whom I married and we managed to finish out our careers together.”

Ligon made master sergeant. She worked as a meteorologist.

“I didn’t want a traditional job. I didn’t want to be an administrative clerk in an office.”

She ended her career as a data base programmer and since her retirement she’s done web development work. She also had her own lingerie boutique, Intimate Creations, at Southroads Mall. Democratic Party business takes up most of her time these days.

Charlene’s military veteran father died in 1979. He supported her decision to serve her country.

Bittersweet end and redemption

While off in the military, Charlene wasn’t around to witness her mother falling out of favor with a new regime of leaders who distanced themselves from her. Mama Butts lost bids for public office and was even voted out of the Concerned Citizens group she founded. This, after having received community service awards and being accorded much attention.

Personality conflicts and turf wars come with the territory in politics.

“For a long time, my mom didn’t let those things stop her.”

Then it got to be too much and Evelyn dropped out.

Upon her death, Earl Swift wrote:

Evelyn Butts’ life had become a Shakespearean tragedy. She’d dived from the heights of power to something very close to irrelevance. This is someone who should have finished life celebrated, rather than forgotten. History better be kind to this woman. Evelyn Butts was important.

The family agreed her important legacy needed rescue from the political power grabs that tarnished it.

“The Democratic Party really was not nice to my mom. That was another reason I wrote the book – because I wanted that to be known,” Charlene said. “I didn’t know all that had gone on until 1993 when she died. I wanted to present who she was. how she came to be that way and the lessons you can learn from her life. I think those lessons are really important for young people because we need to move forward, we need to stay focused and know that we can’t give up – the struggle is still there.

“People need to vote. That’s what they really need to do. They need to participate. Voting is their force and they don’t realize it, and that’s really disheartening. Even in Norfolk, my hometown, the registered voter numbers and turnout for elections among blacks is horrible – just like it is here. In north and south Omaha, they don’t turn out the way they could – 10 to 15 percent less than the rest of the city. That should not be.

“When John Ewing ran for Congress he lost by one and a half points. A little bit of extra turnout in North Omaha would have put him over the top. The same thing happened when Brenda Council ran for mayor of the City of Omaha. If they had turned out for Brenda, Brenda would have been elected. That discourages me because they feel like they’re only a small percentage of the population. Yes, it’s true, but you can still make a difference and when you make that difference that gives you a voice. When you can swing an election, candidates and elected officials pay attention. When black voters say ‘they don’t care about us,’ well I guess not, if you don’t have a voice.”

If anything, the work of Evelyn Butts proved what a difference one person can make in building a collective of activated citizens to make positive change.

To Ligon’s delight, her mother is fondly remembered and people want to promote her legacy. A street and community center are named after her. A church houses a tribute display. Endorsements for the book came from former Virginia governor and senator Chuck Robb and current Norfolk mayor Kenneth Cooper Alexander, who wrote the foreword.

Ligon was back home in Norfolk in January for a book signing in conjunction with MLK Day. She’s back there again for more book signings in February for Black History Month.

In Omaha, Fearless is available at The Bookworm, other fine bookstores and select libraries.

Fittingly, the book has been warmly received by diverse audiences. Long before intersectionality became a thing, Ligon writes in her book, her mother practiced it.

She was black. She was a woman. She was poor. She had dropped out of high school. She was overweight and she spoke loudly with confidence in her opinions in a voice that disclosed her working-class, almost rural upbringing. But this large, black poor woman was in the room with politically powerful white people, making policy and advocating for the poor, and it drove some suit-wearing, educated, well-heeled, middle-class male ministers nuts. Some wanted her place. Or, they believed her place should be subservient to a man.

When her public career ended, my mother retreated to private life … She occupied her time by being a mother, a grandmother, a caregiver, a homemaker and a fantastic cook. To say that her post-political years were tragic is to miss how much strength and satisfaction she drew from those roles. She may have retreated, but she was not defeated.

We will never come to consensus on why Evelyn Butts lost her political power. There will always be people in Norfolk who thought her ‘style’ made her unelectable, that she brought about her own demise … Whatever her failings, her legacy is not in dispute. She will always exist in the pages of the U.S. Supreme Court case, in brick and mortar buildings that she helped to create, and in the memories of people …

For me, her last surviving daughter, Evelyn Butts will always be a great American hero.

If there’s a final lesson Charlene said she’s taken from her mother it’s that “there are things bigger than yourself to fight for – and so I do what I do for my kids and grandkids.”

She’s sure her mom would be proud she followed in her footsteps to become a much decorated Democratic Party stalwart and voting rights champion.

“I haven’t thought about a legacy for myself. I hope people will remember me as a hard worker and as a pragmatic, fair fighter for social justice and civil rights.”

Visit evelyntbutts.com or http://www.facebook.com/evelyntbutts.

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

The November issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com) features my story on an old-line but still vital social action organization celebrating 90 years in Omaha.

The Urban League. The name may be familiar but the role it plays not. Since the National Urban League’s 1910 birth from the progressive social work movement, it’s used advocacy over activism to promote equality. The New York City-based NUL encouraged the creation of affiliates to serve blacks leaving the South in the Great Migration. One of its oldest continuously operating affiliates is the Urban League of Nebraska. The local non-profit started in 1927 as the Omaha Urban League and so operated until changing to Urban League of Nebraska (ULN) in 1968.

This century-plus national integrationist organization is anything but a tired old outfit living off 1950s-1960s Freedom Movement laurels. Its mission today within the ongoing movement is “to enable African-Americans to secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights.” Ditto for ULN, which marks 90 years in 2017. At various times the local office made housing, jobs and health priorities. Today, it does advocacy around juvenile justice, education and child welfare reform and is a service provider of education, youth development, employment and career services programs. It continues a long-standing scholarships program.

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the November 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The Urban League.

The name may be familiar but the role it plays not. Since the National Urban League’s 1910 birth from the progressive social work movement, it’s used advocacy over activism to promote equality. The New York City-based NUL encouraged the creation of affiliates to serve blacks leaving the South in the Great Migration. One of its oldest continuously operating affiliates is the Urban League of Nebraska. The local non-profit started in 1927 as the Omaha Urban League and so operated until changing to Urban League of Nebraska (ULN) in 1968.

This century-plus national integrationist organization is anything but a tired old outfit living off 1950s-1960s Freedom Movement laurels. Its mission today within the ongoing movement is “to enable African-Americans to secure economic self-reliance, parity, power and civil rights.” Ditto for ULN, which marks 90 years in 2017. At various times the local office made housing, jobs and health priorities. Today, it does advocacy around juvenile justice, education and child welfare reform and is a service provider of education, youth development, employment and career services programs. It continues a long-standing scholarships program.

Agency branding says ULN aspires to close “the social economic gap for African-Americans and emerging ethnic communities and disadvantaged families in the achievement of social equality and economic independence and growth.”

The emphasis on education and employment as self-determination pathways became more paramount after the Omaha World-Herald’s 2007 series documenting the city’s disproportionately impoverished African-American population. ULN became a key partner of a facilitator-catalyst for change that emerged – the Empowerment Network. In a decade of focused work, North Omaha blacks are making sharp socio-economic gains.

“It was a call to action,” current ULN president-CEO Thomas Warren said of this concerted response to tackle poverty. “This was the first time in my lifetime I’ve seen this type of grassroots mobilization. It coincided with a number of nonprofit executive directors from this community working collaboratively with one another. It also was, in my opinion, a result of strategically situated elected officials working cooperatively together with a common interest and goal – and with the support of the donor-philanthropic community.

“The United Way of the Midlands wanted their allocations aligned with community needs and priorities – and poverty emerged as a priority. Then, too, we had support from our corporate community. For the first time, there was alignment across sectors and disciplines.”

Unprecedented capital investments are helping repopulate and transform a long neglected and depressed area. Both symbolic and tangible expressions of hope are happening side by side.

“It’s the most significant investment this community’s ever experienced,” said Warren, a North O native who intersected with ULN as a youth. He said the League’s always had a strong presence there. He came to lead ULN in 2008 after 24 years with the Omaha Police Department, where he was the first black chief of police.

“I was very familiar with the organization and the importance of its work.”

He received an Urban League scholarship upon graduating Tech High School. A local UL legend, the late Charles B. Washington, was a mentor to Warren, whose wife Aileen once served as vice president of programs.

Warren concedes some may question the relevance of a traditional civil rights organization that prefers the board room and classroom to Black Lives Matter street tactics.

“When asked the relevance, I say it’s improving our community and changing lives,” he said, “We prefer to engage in action and to address issues by working within institutions to affect change. As contrasted to activism, we don’t engage much in public protests. We’re more results-oriented versus seeking attention. As a result, there may not be as much public recognition or acknowledgment of the work we do, but I can tell you we have seen the fruits of our efforts.”

“We’re an advocacy organization and we’re a services and solutions provider. We’re not trying to drum up controversy based on an issue,” said board chairman Jason Hansen, an American National Bank executive. “We talk about poverty a lot because poverty’s the powder keg for a lot of unrest.”

Impacting people where they live, Warren said, is vital if “we want to make sure the organization is vibrant, relevant, vital to ensuring this community prospers.”

“We deal with this complex social-economic condition called poverty,” he said. “I take a very realistic approach to problem-solving. My focus is on addressing the root causes, not the symptoms. That means engaging in conversations that are sometimes unpleasant.”

Warren said quantifiable differences are being made.

“Fortunately, we have seen the dial move in a significant manner relative to the metrics we measure and the issues we attempt to address. Whether disparities in employment, poverty, educational attainment, graduation rates, we’ve seen significant progress in the last 10 years. Certainly, we still have a ways to go.”

The gains may outstrip anything seen here before.

Soon after the local affiliate’s start, the Great Depression hit. The then-Omaha Urban League carried out the national charter before transitioning into a community center (housed at the Webster Exchange Building) hosting social-recreational activities as well as doing job placements. In the 1940s, the Omaha League returned to its social justice roots by addressing ever more pressing housing and job disparities. When the late Whitney Young Jr. came to head the League in 1950, he took the revitalized organization to new levels of activism before leaving in 1953. He went on to become national UL executive director, he spoke at the March on Washington and advised presidents. A mural of him is displayed in the ULN lobby.

Warren’s an admirer of Young, “the militant mediator,” whose historic civil rights work makes him the local League’s great legacy leader. In Omaha, Young worked with white allies in corporate and government circles as well as with black churches and the militant social action group the De Porres Club led by Fr. John Markoe to address discrimination. During Young’s tenure, modest inroads were made in fair hiring and housing practices.

Long after Young left, the Near North Side suffered damaging blows it’s only now recovering from. The League, along with the NAACP, 4CL, Wesley House, YMCA, Omaha OIC and other players responded to deteriorating conditions through protests and programs.

League stalwarts-community activists Dorothy Eure and Lurlene Johnson were among a group of parents whose federal lawsuit forced the Omaha Public Schools to desegregate. ULN sponsored its own community affairs television program, “Omaha Can We Do,” hosted by Warren’s mentor, Charles Washington.

Mary Thomas has worked 43 years at ULN, where she’s known as “Mrs. T.” She said Washington and another departed friend, Dorothy Eure, “really helped me along the way and guided me on some of the things I got involved in in civil rights. Thanks to them, I marched against discrimination, against police brutality, for affirmative action, for integrated schools.”

Rozalyn Bredow, ULN director of Employment and Career Services, said being an Urban Leaguer means being “involved in social programs, activism, voter rights, equal rights, women’s rights – it’s wanting to be part of the solution, the movement, whatever the movement is at the time.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, ULN changed to being a social services conduit under George Dillard.

“We called George Dillard Mr. D,” said Mrs. T. “A very good, strong man. He knew the Urban League movement well.”

She said the same way Washington and Eure schooled her in ciivl rights, Dillard and his predecessor, George Dean, taught her the Urban League movement.

“We were dealing with a multiplicity of issues at that particular time,” Dillard said, “and I imagine they’re still dealing with them now. At the time I took over, the organization had been through two or three different CEOs in about a five year period of time. That kind of turnover does not stabilize an organization. It hampers your program and mission.”

Dillard got things rolling. He formed a committee tasked with monitoring the Omaha Public Schools desegregation plan “to ensure it did not adversely affect our kids.” He implemented a black community roundtable for stakeholders “to discuss issues affecting our community.” He began a black college tour.

After his departure, ULN went through another quick succession of directors. It struggled meeting community expectations. Upon Thomas Warren’s arrival, regaining credibility and stability became his top priority. He began by reorganizing the board.

“When I started here in 2008 we had eight employees and an operating budget of $800,000, which was about $150,000 in the red,” Warren said. “Relationships had been strained with our corporate partners and with our donor-philanthropic community, including United Way. My first order of business was to restore our reputation by reestablishing relationships.”

His OPD track record helped smooth things over.

“As we were looking to get support for our programs and services, individuals were willing to listen to me. They wanted to know we would be administering quality services. They wanted to know our goals and measurable outcomes. We just rolled up our sleeves and went to work because during the recession there was a tremendous increase in demand for services. Nonprofits were struggling. But we met the challenge.

“In the first five years we doubled our staff. Tripled our budget. Currently, we manage a $3 million operating budget. We have 34 full-time employees. Another 24 part-time employees.”

Under Warren. ULN’s twice received perfect assessment scores from on-site national audits.

“It’s a standard of excellence for our adherence to best practices and compliance with the Urban League’s articles of affiliation,” he said.

Financially, the organization’s on sound footing.

“We’ve done a really admirable job of diversifying our revenue stream. More than 85 percent of our revenue comes from sources other than federal and state grants,” said board chair Jason Hansen. “We have a cash reserve exceeding what the organization’s entire budget was in 2008. It’s really a testament to strong fiscal management – and donors want to see that.”

“It was very important we manage our resources efficiently,” Warren said.

Along the way, ULN itself has been a jobs creator by hiring additional staff to run expanding programs.

“The growth was incremental and methodical,” Warren said, “We didn’t want to grow too big, too fast. We wanted to be able to sustain our programs. Our ability to administer quality programs got the support of our donor-philanthropic-corporate-public communities.

“We have been able to maintain our workforce and sustain our programs. The credit is due to our staff and to the leadership provided by our board of directors.”

Warren’s 10 years at the top of ULN is the longest since Dillard’s reign from 1983 to 2000. Under Warren, the organization’s back to more of its social justice past.

Even though Mrs. T’s firebrand activism is not the League’s style, sometimes causing her to clash with the reserved Warren, whom she calls “Chief,” she said they share the same values.

“We just try to correct the wrong that’s done to people. I always have liked to right a wrong.”

She also likes it when Warren breaks his reserve to tell it like it is to corporate big wigs and elected officials.

“When he’s fighting for what he believes, Chief can really be angry and forceful, and they can’t pull the wool over his eyes because he sees through it.”

Mrs. T feels ULN’s back to where it was under Dillard.

“It was very strong then and I feel it’s very strong now. In between Mr. D and Chief, we had a number of acting or interim directors and even though those people meant well, until you get somebody solid, you’ve got a weakness in there.”

Pat Brown agrees. She’s been an Urban Leaguer since 1962. Her involvement deepened after joining the ULN Guild in 1968. The Guild’s organized everything from a bottillon to fundraisers to nursing home visits.

“Things were hopping. We had everything going on and everything running smoothly taking part in community things, working with youth, putting on events.”

She sees it all happening again.

Kathy J. Trotter also has a long history with the League. She reactivated the guild, which is ULN’s civic engagement-fundraising arm. She said countless volunteers, including herself, have “grown” through community service, awareness and leadership development through Guild activities. She chaperoned its black college tour for many years.

Trotter likes “to share our vision that a strong African- American community is a better Nebraska” with ULN’s diverse collaborators and partners.

Much of ULN’s multicultural work happens behind-the-scenes with CEOs, elected officials and other stakeholders. ULN volunteers like Trotter, Mrs. T and Pat Brown as well as Warren and staff often meet notables in pursuit of the movement’s aims.

“I don’t think people realize the amount of work we do and the sheer number of programs and services we provide in education, workforce development, violence prevention,” Jason Hansen said. “We have programs and services tailored to fit the community.”

Most are free.

“When you talk about training the job force of tomorrow, it begins with youth and education,” Hansen said. “We’ve seen a significant rise of African-Americans with a four-year college degree. That’s going to provide a better pipeline of talent to serve Omaha.”

Warren devised a strategic niche for ULN.

“We narrowed our focus on those areas where we not only felt we have expertise but where we could have the greatest impact,” he said. “If we have clients who need supportive services, we simply refer them.”

Some referrals go to neighbors Salem Baptist Church, Charles Drew Health Center, Family Housing Advisory Services, Omaha Small Business Network and Omaha Economic Development Corporation.

“We feel we can increase our efficiency and capacity by collaboration with those organizations.”

EDUCATION

Since refocusing its efforts, ULN regularly lands grants and contracts to administer education programs for entities like Collective for Youth.

ULN works closely with the Omaha Public Schools on addressing truancy. It utilizes African-American young professionals as Youth Attendance Navigators to mentor target students in select elementary and high schools to keep them in school and graduating on time.

Community Coaches work with at-risk youth who may have been in the juvenile justice system, providing guidance in navigating high school on through college.

ULN also administers some after school programs.

“Many of these kids want to know someone cares about their fate and well-being,” Warren said. “It’s mentoring relationships. We can also provide supportive services to their families.”

The Whitney Young Jr. Academy and Project Ready provide students college preparatory support ranging from campus tours to applications assistance to test prep to essay writing workshops to financial aid literacy.

“Many of them are first-generation college students and that process can be somewhat demanding and intimidating. We’re going to prepare the next generation of leaders here and we want to make sure they’re ready for school, for work, for life.”

Like other ULN staff, Academy-Project Ready coordinator Nicole Mitchell can identify with clients.

“Growing up in the Logan Fontanelle projects, I was just like the students I work with. There’s a lot I didn’t get to do or couldn’t do because of economics or other barriers, so my heart and passion is to make sure that when things look impossible for kids they know that anything is possible if you put the work and resources behind it. We make sure they have a plan for life after high school. College is one focus, but we know college is not for everyone, so we give them other options besides just post-secondary studies.”

“We want to make sure we break down any barrier that prevents them from following their dreams and being productive citizens. Currently, we have 127 students, ages 13 to 18, enrolled in our academy.”

Whitney Young Jr. Academy graduates are doing well.

“We currently have students attending 34 institutions of higher education,” said ULN College Specialist Jeffrey Williams. “Many have done internships. Ninety-eight percent of Urban League of Nebraska Scholarship recipients are still enrolled in college going back to 2014. One hundred percent of recipients are high school graduates, with 79% of them having GPAs above 3.0.”

Warren touts the student support in place.

“We work with them throughout high school with our supplemental ed programs, our college preparatory programs, making sure they graduate high school and enroll in a post-secondary education institution. And that’s where we’ve seen significant improvements.

“When I started at the Urban League, the graduation rate for African-American students was 65 percent in OPS. Now it’s about 80 percent. That’s statistically significant and it’s holding. We’ve seen significant increases in enrollment in post-secondary – both in community colleges and four-year colleges and universities. UNO and UNL have reported record enrollments of African-American students. More importantly, we’ve seen significant increases in African-Americans earning bachelor degrees – from roughly 16 percent in 2011 to 25 percent in 2016.”

With achievement up, the goal is keeping talent here.

TALENT RETENTION

A survey ULN did in partnership with the Omaha Chamber of Commerce confirmed earlier findings that African-American young professionals consider Omaha an unfavorable place to live and work. ULN has a robust young professionals group.

“It was a call to action to me personally and professionally and for our community to see what we can do cultivate and retain our young professionals,” Warren said. “The main issues that came up were hiring and promotions, professional growth and development, mentoring and pay being commensurate with credentials. There was also a strong interest in entrepreneurship expressed.

“Millenials want to work in a diverse, inclusive environment. If we don’t create that type of environment, they’re going to leave. We want to use the results as a tool to drive some of these conversations and ultimately have an impact on seeing things change. If we are to prosper as a community, we have to retain our talent as a matter of necessity.We export more talent than we import. We need to keep our best and brightest. It’s in our own best interest as a community.”

The results didn’t surprise Richard Webb, ULN Young Professionals chair and CEO of 100 Black Men Omaha.

“I grew up in this community, so I definitely understand the atmosphere that was created. We’ve known the problems for a long time, but it seemed like we never had never enough momentum to make any changes. With the commitment and response we’ve got from the community, I feel there’s a lot of momentum now for pushing these issues to the front and finding solutions.”

“Corporate Omaha needs to partner with us and others on how we make it a more inclusive environment,” Jason Hansen said.

With the North O narrative changing from hopeless to hopeful, Hansen said, “Now we’re talking about how do we retain our African-American young talent and keep them vested in Omaha and I’d much rather be fighting that problem than continued increase in poverty and violence and declining graduation rates.

Webb’s attracted to ULN’s commitment to change.

“It’s representing a voice to empower people from the community with avenues up and out. It gathers resources and put families in better positions to make it out of The Hood or into a situation where they’re -self-sustaining.”

CAREER READINESS

On the jobs front, ULN conducts career boot camps and hosts job fairs. It runs a welfare to work readiness program for ResCare.

“We administer the Step-Up program for the Empowerment Network,” Warren said. “We case managed 150-plus youth this past summer at work sites throughout the city. We provide coaches that provide those youth with feedback and supervise their performance at the worksites.”

Combined with the education pieces, he said, “The continuum of services we offer can now start as early as elementary school. We can work with youth and young adults as they go on through college and enter into their careers. Kids who started with us 10 years ago in middle school are enrolled in college now and in some cases have finished school and entered the workforce.”

The Urban League maintains a year-round presence in the Community Engagement Center at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

Olivia Cobb is part of another population segment the League focuses on: adults in adverse circumstances looking to enhance their education and employability.

Intensive case management gets clients job-school ready.