Archive

Passion, vision, defined mission make nonprofits click

Passion, vision, defined mission make nonprofits click

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the May 2019 edition of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Nonprofits thrive when they find a community niche no one else serves. Next comes getting influencers and supporters to catch their vision and invest in the mission. The entrepreneurs behind the six Omaha nonprofits featured here don’t lead the largest or the most well-known organizations. But each oversees a distinct work borne of passion and vision that serves a specific population. Each entity stands apart from the crowded nonprofit field by filling a need or gap that otherwise wouldn’t be satisfied.

Sweat and soul make these nonprofits click. It all starts and ends with the people who dreamed them up. Each founder is still at the helm, refining the vision, steadying the course, and retelling the story.

The Bike Union and Coffee

As mentoring efforts go, Bike Union and Coffee follows an unconventional path not unlike that of founder-executive director, Miah Sommer.

For starters, its human services are intentionally scaled-down to serve a handful of young people. Bigger isn’t always better the way Sommer sees it.

“There’s a point of diminishing returns,” he said. “Do we want numbers to feel good about how many we’re serving or do we want results? We’ll only grow if we feel that makes the most sense.”

Union-Coffee mentors mainly young adults who’ve aged out of foster care. Most have a history of trauma. They struggle reentering society as independent young men and women. Devoting attention to a few clients, Sommer said, “hasn’t been real popular with some funders, but I really think that’s the only way to tackle trauma. I want to make relationship-based programming. In some way that’s what I was lacking at their age – meaningful adult mentor relationships.”

Clients learn social-job skills working alongside staff and volunteers and dealing with customers at this combo repair shop and coffeehouse at 1818 Dodge Street. Experts provide GED preparation, reading comprehension, financial literacy and other services.

Mindfulness meditation and cooking-nutrition classes are offered participants.

Bike repair and coffee revenues help fund operations.

Though Sommer was never in the system, he grew up adrift and estranged. He dropped out of high school, only earning his GED at 27. He majored in history and religion at college. He turned a serious cycling passion into a retail career that spawned a recreational trek biking program for inner city youth, BUMP. It’s now part of his social entrepreneurship mentoring endeavor.

“I left my job to start this in 2015 with a month’s salary, a wife, kids and a house, so I had to make it happen. I blinded myself to all the challenges of starting a nonprofit that is also a business.”

Employment program participants are referred by Project Everlast and Bridge to Independence. Originally designed for new cohorts of four mentees to graduate every 12 months, real life dictates a looser timetable.

“Now we understand this is a for-keeps relationship we need to stay involved in. We might have five in the program right now, but ten might come through the door each week needing services. Some don’t go through the 12 months. They just aren’t ready to work on themselves or they exit early when they find another job. Others stay 16 months until they’re ready to move on.”

“Until they’re ready” is the new mantra.

There are breakthroughs and setbacks. The camaraderie and training, including peer-to-peer mentoring, keep drawing participants in.

“Some just come to hang around. Others need help with problems they’re having. Even the kids that have been fired still come back. It’s a safe place for them, It’s a place where they feel accepted. It’s like a big family.”

Illegal or threatening behaviors are not tolerated.

“Generally, those kids are weeded out at about three months,” Sommer said. “They usually end up leaving on their own free will.”

For those who stick it out, there’s no hard and fast goal.

“The programming is designed to achieve what they want to achieve. There’s no, you’ll do this, this, this and this. It’s like, where do you see yourself? It works differently for different people.”

The focus is on getting participants to overcome doubts, face fears and achieve realistic goals.

“They come from a place where they’ve been told they can’t do things or they tell themselves they can’t do things. We’re all about telling them you can do this thing. They end up with all these small victories.”

Rites of passage moments like getting a driver’s license, opening a bank account, graduating high school, getting a GED, starting college and finding steady employment are celebrated, he said, because those “are huge” considering where clients have been.

“Each is a step in the right direction and makes them feel more connected to society,” he said. “Belonging and connecting and doing things that are societal norms is real important. Everybody has a need to belong and the people we serve are no different. They want the same things everybody else does. It’s not a question of ability, it’s a question of opportunity.”

The public can support the effort just by bringing in a bike, buying coffee and interacting with participants.

“It’s great to like us on Facebook” Sommer said, “but this doesn’t work if people don’t come in.”

Just don’t confuse what happens there with charity.

“We don’t do this out of pity. We do this out of solidarity and standing on the margins with young people whose resilience to keep moving forward is pretty pronounced.”

Visit http://www.thebikeunion.org.

Saving Grace Perishable Food Rescue

Beth Ostdiek Smith was a 59-year-old former travel industry professional and nonprofit executive when she launched an organization poised at the intersection of food waste, hunger, access and healthy eating.

The core mission of Saving Grace Perishable Food Rescue (SGPFR) is capturing and redistributing fresh and prepared edibles – 1.6 million pounds and counting since 2013.

“We’re not taking it for us. We don’t warehouse anything,” Smith said.” As fresh as everything we get, our clients get it.”

Four refrigerated trucks wrapped in the logo of an urchin girl holding a spoon un on a tight schedule. Professional drivers-food handlers make all the pickups-deliveries.

“In this perishable food business,” she said, “you have to show up when you say you’ll show up.”

Her service redirects some metro food waste – an estimated 40 percent of food ends up in landfills – to people who need it, including an estimated 20 percent of children who otherwise go to bed hungry.

She started Grace to bridge the excess-want gap.

“I noticed there was always excess food at events. I asked around Omaha and nobody was doing food rescue at scale. I took a leap of faith and put Saving Grace together. It’s a nonprofit business that provides a charitable service to our community.”

She based it on an Arizona food rescue program– hiring away its operations director, Judy Rydberg.

Smith’s networking has gotten hotels, conventions centers, restaurant chains, grocers and wholesale food suppliers to consistently donate their excess.

“That’s the movement we’re trying to have happen. It takes the community to do that. My expertise is really bringing people together I’m a builder and entrepreneur.”

The organization also has a mission to raise awareness around food waste and hunger. As it’s neither a pantry nor a food bank, Smith said, “it’s a different model than everybody’s used to.” It’s why she spends much time “explaining who we are and what we do.”

She recruits most food donors but more are calling her. Major recipients include pantries.

“We get the right food to them by doing a food match based on client needs. They’re not having to go out and source all this food. We bring it to them.”

Heart Ministry Center Pantry in North Omaha is a primary user. Grace will supply even more food there once the center’s expanded pantry opens.

“For some of our larger nonprofit partners we are just a small portion of the food they give out because they purchase from Food Bank of the Heartland. Others don’t qualify for the Food Bank because they’re too small and so we are their only source for food.”

Education efforts encourage people to make better choices in shopping for food in order to reduce waste.

“We’re trying to deliver those messages through our Food for Thought programs,” Smith said.

A recent program partnered with Hillside Solutions on excess food as composte.

Saving Grace is also identifying “on that whole food chain where excess should go and ways to get it to more people,” Smith said, including those who don’t quality for a panty but need food assistance.

Smith plans visiting perishable food rescues to assess what they do and envisions a national food rescue consortium for sharing best practices.

She doesn’t want o grow just for growth’s sake.

“We’ll always be lean and mean. We get a lot of in-kind donations.”

Grants tend to follow SGPFR’s clear, easy-to-track outcomes. Smith would like more multi-year grants to fund a reserve or endowment. She’s looking to build a revenue stream by partnering with a local brewer who would make beer out of excess bread and retail it.

A September 30 dinner and wine pairing at Dante Pizzeria will celebrate Saving Grace’s sixth anniversary.

Smith acknowledges her efffort is one piece in a collaborative mosaic addressing food insecurity.

“We cant be everything to everyone. We don’t do all of it. But we have a model that works for a lot of it.”

Visit savinggracefoodrescue.org.

Intercultural Senior Center

After years learning how nonprofits work at One World Community Health, Carolina Padilla ran the Latino Resource Center, which assists young women and families. When some women requested services for their aging immigrant mothers isolated by language and transportation barriers, she realized the organization was ill-equipped to do so. Wanting to address this community need going unmet, she left to found the Intercultural Senior Center (ISC) in 2009 with help from the Eastern Nebraska Office on Aging.

“I found what I really wanted to do,” said Padilla. “I thought, I have to do this and I’m going to make this happen whatever it takes. Then I realized I could do it.”

Working with immigrant and migrant elders appealed to Padilla because in her native Guatemala she lost her own mother at age 6 and was raised by aged aunts.

“They made my life. I always felt strongly that one day I will give back in some way.”

She also identified with the challenges newcomers face having moved to the U.S. with her husband and children. Thus, she created “a place where people share what it means coming to a different country and having to adjust to many cultural differences.”

“They come to share their thoughts and their lives.”

The center started exceedingly small – Padilla did everything herself – and operated from leased South Omaha sites always short on space.

Her mentor and former One World boss, Mary Lee Fitzsimmmons, guided the center in obtaining its 501 C3 status and finding donors.

“Great foundations have been behind us helping us grow our membership, programs and services,” Padilla said. “When we started, we focused just on the basics serving maybe five or ten people a day and 20 to 25 in a week. Right now we have 60, 80 even 100 people a day and 400 a week.”

There’s no participation or membership fee. As the numbers have grown, so has diversity, especially since ISC added senior refugees to its service outreach. On any given day, this melting pot accommodates seniors from two dozen or more nations.

Center programs include:

ESL classes

Basic computer skill classes

Health-wellness classes

Yoga

Case managed social work

A monthly pantry

Door to door transportation

Interpreters help breech language divides.

After four sites in nine years Padilla asked her board to lead a $6.3 million capital campaign to give ISC a home of its own.

“They helped me get that dream.”

ISC moved into its new 22,000 square foot home at 5545 Center Street in March after extensive remodeling to the structure. There’s more room than ISC has ever had, including dedicated spaces for classes and

private conference rooms for social services .

“I’m so happy and proud of what we have.”

More meaningful than the facilities, Padilla said, participants “have each other.” “This center gets them out of isolation. It provides opportunities to learn, to stay active. It becomes people’s second home.

“Coming here lets them see they still have so much to do. It helps them not become a burden to their families.

People are really happy here. They feel welcomed. It’s a warm place. Our staff is welcoming. They love our seniors. Sure, we have programming and a structure, but it’s more about the way people feel here.”

ISC partners create intergenerational opportunities between seniors and young people.

“We work very closely with UNO’s Service Learning program. Students come here and get involved in different activities and programs year-round. Elementary, middle and high school students participate in those projects. Youth interact with seniors making art, exercising, playing games, sharing stories.

“College and university nursing students work with seniors in our wellness program. It’s a way for students to put their skills into practice and learn what it is to be around diversity.”

Longtime ISC partner Big Garden is moving raised beds from the center’s previous site to the new location “so our seniors can garden again,” Padilla said. “We’re a grassroots organization. We depend on partnerships. Partnering allows us to better serve the community. That’s the beauty of doing things together.

“What we have built is the base and we’re just trying to get better. There’s still so many things to do to improve serving the aging population.”

She’d like to add physical therapy and additional wellness components.

Padilla is banking on ISC receiving accreditation from the National Council on Aging.

“I think this will help our organization to be seen in a different way, so we can bring more resources to the center

Though she has a staff of 18, she personally keeps close tabs on operations.

“I am hands-on in every single thing that goes on here.”

Padilla said working with seniors sparks “a new appreciation for life.”

“It’s an honor to serve this community. It’s a mission I feel. It’s not a job – it’s part of me.”

Making it all worthwhile is having octogenarians become citizens. learn to write their name, develop English fluency and earn their GED.

“That’s big and we are making that possible.”

If the center’s diversity has taught her anything, she said, it’s that “regardless of educational-cultural backgrounds and financial stability, all of our seniors have amazing stories of happiness, struggles and hard work and they all have the need to be loved and to hold someone’s hand.”

Then there’s the balancing act seniors who are transplants to America must negotiate in terms of assimilation versus holding onto native cultural identities. Padilla said the center helps promote mutual respect and understanding of cultures. It’s all about welcoming the stranger and adjusting to new ways.

“It’s difficult, but they do it.”

ISC’s August 22 World Bash fundraiser is at St Robert Bellarmine Church.

Visit http://www.interculturalseniorcenter.org.

Heartland Workers Center

Guatemala native Sergio Sosa won victories for meatpackers as an Omaha Together One Community labor organizer in the early 2000s. He advised Latinos in the packing and hospitality industries in staging mass demonstrations for immigration reform. Flush with success among this constituency, he launched Heartland Workers Center (HWC) in 2009.

“The vision was to improve the lives of Latino-Latina immigrants in the Heartland,” said Sosa, “Our strategic mission’s major programs are leadership development, workers rights and civic engagement.”

Sosa and his team of community organizers conduct their work in the streets, in people’s homes, at community centers, churches and schools.

“We do not provide services. If we do, it’s only to affect what we do for people who will be part of the solution of their own problems. Our rule number one is never do for others what they can for themselves.”

With lead organizer Abbie Kretz, Sosa “built the capacity of the center, got the trust of major funders, went from a couple employees to almost 20 and expanded from one site, in South Omaha, to offices across the state.”

The first ever South Omaha Political Convention followed in 2015. The biennial event is expected to draw 1,000 participants when it happens again November 10.

Year-round civic engagement revolves around statewide Get Out the Vote (GOTV) efforts that mobilize minorities to register, vote and run for elected office.

A major emphasis, Sosa said. is “bringing leaders from rural and urban areas together to think of this as one state.” “Economically,” he said, “the goal is to find investments to improve communities in terms of housing, infrastructure, education.”

Another focus is advocating immigration reform and workers rights issues in the Unicameral.

“We train people how to testify before state legislators and how the Unicameral works,” he said.

Recently, HWC activists supported bills preserving SNAP benefits and increasing worker’s wages from tips and granting protection from employer retaliation.

Before Gabriela Pedroza became a HWC organizer, Sosa said, she never even visited Lincoln. “But now she’s testified, trained others to testify and knows the ins and outs of the Unicameral. Next year she will be in charge of the Unicameral effort.

“That’s how change happens,” said Sosa, adding, “Women are becoming a major voice and catalyst for change. The traditional institutions are not reinventing themselves. That’s why they’re dying. Youth and women-led movements are spawning new institutions with grassroots political power.”

The Center cultivates new leaders. “We teach organizers where they can find leaders,” he said. “It can be through canvassing neighborhoods.” Once captured, HWC “mentors, teaches and activates them.”

On the micro level, he said, “It’s about people investing in their own neighborhoods and communities and being the agents of change themselves rather than waiting for the city to act.” South Omaha’s Brown Park had fallen into disrepair and a coalition of neighbors “are now working with leaders to fix it.”

“People have to learn how to act for themselves,” Abbie Kretz said. “Otherwise, they create dependency on organizers to do those things. It’s learning how processes and power work and building relationships with public officials and nonprofit leaders. You have more capacity and power when you do it collectively.”

In Schuyler, Nebraska, HWC-led efforts increased voter participation by the Latino majority and resulted in

four Latinos in public office, Kretz said. Parents there demanded dual language programs and “a collective of folks from the schools and the community working together got one started.”

“That’s what democracy is all about,” Sosa said. It’s a very patient work, but in the end it pays off.”

HWC has established itself with that steady work.

“By building relationships with people over time they understand who we are and what we do,” Kretz said,

“and that’s helped to build bridges versus burn them.”

“Rural Nebraska doesn’t see us as foreign outsiders coming to their small towns,” Sosa said, “because we hire people from those towns.”

Inroads for inclusive leadership and representation are happening statewide. In Columbus, HWC partners with entrenched organizations on community-wide events. Latinos in Grand Island are now part of the Nebraska State Fair planning committee. Traditional Latino celebrations and memorials are embraced by more towns as part of the fabric of life there.

“So, it’s changing,” said Sosa, who sees it as proof that “if you combine love with power, you get social justice.”

Change starts from within.

“If you don’t change you, nothing around you is going to change. You have to give yourself that permission to dream big,” he said.

Gabriela Pedroza knows from experience.

“That awakening keeps me going,” she said. “Realizing who you are and having that relationship with yourself is hard work and it takes time. But once you start, you want to do it with others. You want others to know you have more power than you think.”

Despite how polarized the U.S. is, Sosa said, “we still have open political spaces that provide an opportunity for compromise and change – and we better be active now in teaching others to do it so we don’t lose it.”

Visit http://www.heartlandworkerscenter.org.

Young Black & Influential/I Be Black Girl

Omaha native Ashlei Spivey has generated two buzz-worthy black-centric empowerment movements that reflect her late mother’s passion.

“My mom and I spent a lot of time talking about, what do you want your life to mean? what does that look like? how do you create impact for folks? So I think I’ve always had that embedded in me,” said Spivey. “Growing up there was a lot of systemic inequity happening around me. There was the richness of the black community but due to racism and oppression also lack of jobs and those things.”

Her father was incarcerated most of her life.

“My mom wanted to protect me from the situation surrounding me and made sure I had every opportunity. I was fortunate to have a parent who really poured into me in a way that added value. She saw all the potential I had.”

Spivey went to college down South, returning to Omaha eight years ago following her mother’s death. “It was very sudden. That was really hard. We were very close. I came back to be the guardian to my sister, who was 12.”

Spivey’s grandmother helps raise her 5-year-old son.

Working at College Possible and Heartland Family Service led to Spivey’s current post at Peter Kiewit Foundation. Wherever she’s worked, she’s been the only or first African-American. “Thinking about empowerment for the people on the receiving end of inequity” led to Young Black & Influential (YBI) in 2015 and I Be Black Girl (iBBG) in 2017.

“YBI was created to say we can affirm black folks doing things for the black community based on our own definition. You don’t have to look, talk, have certain experiences in order to be deemed an influencer. The people we recognize may have a degree or not, may work in a corporate setting or not. may have been incarcerated or not. There’s the whole spectrum

“It’s about supporting, acknowledging and showing leadership in different ways. It’s about creating your own narrative and owning it and affirming this is who I am and no one can take that away or negate that.”

Influencers from the community are recognized at a YBI awards banquet – The next is June 30 at The Living Room in The Mastercraft.

“There are some dynamic folks doing awesome work under the radar. We also do leadership development at the grassroots level. We’ve launched a board training program to get black folks on nonprofit boards. We’re really trying to build power.”

IBBG’s name riffs off the best-selling children’s book Be Boy Buzz celebrating what black boys can be. Spivey sees IBBG as “changing narratives and creating space for black women to have access to different spaces.”

The organization “holds networking events and does programming around things that affect black women and girls,” such as a recent screening of Little.

IBBG’s advisory committee intentionally includes women workIng in philanthropy, Spivey views it as “disrupting power structures.” “We feel like this might be a place where we are creating philanthropists that don’t look like Omaha’s very old, white, male philanthropists now.”

An IBBG Giving Circle with a goal of $10,000 raised $50,000. In May, IBBG is awarding $35,000 in grants to innovative approaches that advance black girls and women. Grant awards will be made annually. New Giving Circle donations are being accepted.

The funding, Spivey said, “is all about making possible seats at the table and building an institution you have to check in with before you do service delivery or interventions for black women and girls in the community.”

Both IBBG and YBI are tapping into “a restored pride in being black, in how we take care of community and how we make decisions about community,” she said. “This is a way people can engage and add value with whatever their investment in the community is.”

Adding stability to these changemaker efforts is fiscal sponsor Women’s Fund of Omaha. “They have been great partners. Allyship is important.”

Spivey’s exploring the addition of entrepreneurship and youth leadership development programs.

“My energy and effort is really building power that not only addresses racism but other intersecting isms people may encounter based on their identity,”

She feels her movements align well with where Black America’s arrived.

“Our people have always wanted to pursue their own vision of success and to help raise up our community. The issue has been access, resources and opportunity – that’s what it’s about. Now people are reenergized on how to have ownership over their community.

“A lot of young leaders are not concerned with assimilating or wanting to perpetuate patriarchy. They want to do things radically different and I think radical change is key. We were always ready – we just didn’t know we were ready. Now people are focused on that collective agenda on how things can be black-led.”

IBBG hosts a June 23 celebratory event at The Venue.

Visit http://www.ibbgomaha.com and http://www.ybiomaha.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

Omaha Area Sanctuary Network: Caring cohort goes the distance for undocumented residents caught in the immigraton vice grip

From Japanese-American Internment Camp to Boys Town: Christmas and Other Bittersweet Memories During World War II

From Japanese-American Internment Camp to Boys Town

Christmas and Other Bittersweet Memories During World War II

Story by Leo Adam Biga

Photography provided by Boys Town

Originally appeared in the Nov-Dec 2018 issue of Omaha Magazine

(http://omahamagazine.com/articles/from-japanese-american–internment–camp)

Xenophobic fears ran wild after the Empire of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The U.S. promptly entered World War II, and nearly 120,000 Japanese-Americans were relocated or incarcerated in internment camps across the country.

The Rev. Edward Flanagan, the founder of Boys Town, strived to calm the hysteria in part—while alleviating the trauma falling upon his fellow Americans—by sponsoring approximately 200 Japanese-Americans from internment camps to stay at his rural Nebraska campus for wayward and abandoned youths.

Among them were James and Margaret Takahashi and their three children.

They joined the individuals and families escaping to Boys Town from prison-like internment camps. Flanagan offered dozens of families a place to live and work until the war’s conclusion. Some remained in Nebraska long after the war. Many used Boys Town as a stopover before World War II military service or moving to other American cities and towns, says Boys Town historian Tom Lynch.

Few outsiders knew Boys Town was a safe harbor for Nisei (the Japanese word for North Americans whose parents were immigrants from Japan) who lost their homes, livelihoods, and civil rights in the fear-driven, government-mandated evacuation of Japanese-Americans from the West Coast.

The oldest Takahashi child, Marilyn, was almost 6 when her family was uprooted from their Los Angeles home and way of life. Her gardener father lost his agricultural nursery.

“It was a very disruptive thing,” she recalls. “I was very upset by all of this. I can remember being confused and wondering what was going on and where are we going. I couldn’t understand all of it.”

She and her family joined hundreds of others in a makeshift holding camp at the Santa Anita Assembly Center, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards. Stables at the converted race track doubled as spare barracks. Food riots erupted.

By contrast, at Boys Town, the Takahashis were treated humanely and fairly, as the full citizens they were, with all the comforts and privileges of home.

“We felt welcomed and did not have fears about our environment. The German farmers nearby were friendly and kind,” remembers Marilyn Takahashi Fordney.

The Takahashis were provided their own house and garden within the incorporated village of Boys Town’s boundaries. James, father of the family, worked as the grounds supervisor. The children attended school. The family celebrated major holidays—including unforgettable, bittersweet Christmases—in freedom, but still far from home.

None of it might have happened if Maryknoll priest Hugh Lavery, at a Japanese-American Catholic parish in L.A., hadn’t written Flanagan advocating on behalf of his congregation then being relocated in camps. Flanagan recognized the injustice. He also knew the internees included working-age men who could fill his war-depleted employee ranks. He had the heart, the need, the facilities, and the clout to broker their release from the Civil Exclusions Order signed into law by President Franklin

Delano Roosevelt.

Helping identify “good fits for Boys Town” was Patrick Okura, who ended up there himself, Lynch says. “It sort of started a pipeline to help bring people out,” and Flanagan “eventually took people of all different faiths,” not just internees from the Catholic parish that started the effort. “People from that parish went to the camps, and they met other Japanese-Americans, and they started communicating about this opportunity at Boys Town to get out of the camps.”

During her family’s four-month camp confinement, Marilyn’s parents heard that the famous Irish priest in Nebraska needed workers. James sent a letter making the case for himself and his family to come.

“People could leave if they had somewhere to go,” Marilyn says. “Permission didn’t come right away. It took writing back and forth for several months. Then, when we were all about to be moved to Amache [Granada War Relocation Center] in Colorado, the head of our camp sent a telegram to the War Relocation Authority. He received a telegram back with the necessary permission. We were released to Boys Town Sept. 5, 1942.”

Boys Town became legal sponsor for the new arrivals.

“It was very radical helping these people,” Lynch says. “Father thought it was his duty because they were good American citizens who should be treated well. But it wasn’t universally accepted. What made Boys Town unique is that we were way out in the country, so we were our own little bubble. Visitors really wouldn’t see the internees much. The men worked the farm or grounds. The women tended house. The kids were in school. But they were there all throughout the village.”

A similar effort unfolded at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where 100-plus Nisei students continued their college studies after the rude interruption caused by the “evacuation.”

During her Boys Town sojourn, Marilyn first attended a nearby one-room public school. She later attended a school on campus for workers’ children taught by a Polish Franciscan nun. Besides the standard subjects, the kids learned traditional Polish folk dances and crafts.

The Takahashis started their new life in an old farmhouse they later shared with other arrivals. Then Boys Town built a compound of brick houses for the workers and their families. “Single men lived in a dormitory on campus,” Lynch says. “Boys Town didn’t host many single women because Father would find jobs for them in Omaha, where they would stay with families they worked for as domestics.”

From Santa Anita, the Takahashi patriarch was allowed to go to L.A. to retrieve his truck and what stored family belongings he could transport. James drove to Nebraska to meet Margaret and the kids, who went ahead by train.

Marilyn’s initial impression of Flanagan was of Santa Claus with a cleric’s collar: “Father came to meet us at the station. He had this big brown bag of candy. I will always remember that candy. It was so thoughtful of him to give us that special treat.”

According to the Takahashi family’s file in the archives of the Boys Town Hall of History, Margaret said she was taken by Flanagan’s humanity, that she “could feel this warmth. I’ve never felt that from another human being. He was so full of love that it radiated out of him.”

According to Lynch, Flanagan considered the newcomers “part of the family of Boys Town.” They could access the entire campus or go into town freely.

Leaving altogether, though possible, was not a realistic option.

“They could leave at any time, if they really wanted to, but there was nowhere to go [without authorization]. They would have been detained and returned,” he says.

Marilyn’s experience of losing her home and living in a camp was dreadful. Going halfway across the country to live at Boys Town was an adventure. Her fondest memories there involve Christmas.

“Christmas and midnight Mass was very special at Boys Town,” she says. “It was something we looked forward to. I will always remember getting bundled up to face the blizzard-like winds. My father would carry each one of us to the truck. We would head off in the dead of night in that blasted cold to get to the church, which was dark except for the altar lights. The boys would be in a long line in their white and black cassocks, with red bows, each holding a big lit candle. They would begin to sing and come down the main aisle. It was an awesome sight and a special experience. The choir was exceptional. There was always one singer with a high-pitched voice who did a solo. It was amazing.”

Father Flanagan and children during Christmastime

Flanagan is part of her holiday memories, she says, as “he always made a point to come to our Christmas plays, and we would always take a photograph with him.” For the resident boy population, Flanagan “played” Santa by visiting their apartments and handing out gifts.

“We were happy at Christmas,” Marilyn says. “In the farmhouse, my father would cut a pine tree and bring it in, and the decorations were handmade and hand-painted cones with popcorn strung. He always did the final placement of things so that it looked perfect. We had wonderful Christmas days even though it was difficult to get toys because many things were not available due to the war.”

She continues: “We built an ice rink and would skate in front of the farmhouse or in front of the brick house. We even made an igloo one time. It got so tall the adults came out to help us close the top with the snow blocks because we were too little to reach it.”

Weather always factored in.

“The summers were extremely hot and the winters so severely cold,” she says. “We had never experienced snow. That was a tremendous adjustment for my parents. But, as children, we delighted in it. We’d run out and eat the snow with jam and build snowmen.”

Marilyn recalls visiting Santa at J.L. Brandeis & Sons department store in downtown Omaha with its fabulous Christmas window displays and North Pole Toy Land.

The Takahashis were content enough in their new life that they arranged for family and friends to join them there. Marilyn and family remained in Omaha for two years after the war (and anti-Japanese hysteria) ended.

“Eventually, my parents decided they couldn’t withstand that cold, and we headed back to California in 1947,” she says.

They endured tragedy at Boys Town when Marilyn’s younger brother contracted measles and encephalitis, falling into a coma that caused severe brain damage. His constant care was a burden for the poor family.

Another motivating factor for the family to leave was the father’s desire to work for himself again.

Leaving Boys Town just shy of age 12 was hard for Marilyn.

“I was heartbroken because I loved the snow and cold and all my friends there,” she says. “I did not want to go to California and live three families to a house and struggle. I knew what was coming. I also had a pet cat I was sad to leave. My pet dog Spunky that Boys Town gave me had passed on.”

Her parents had also bonded with some of the resident boys, and with some adult workers and their families.

“We went by Father Flanagan’s residence to say farewell, and he came out to bless us and to bless the truck we drove to the West Coast,” she says.

As an adult, Marilyn shared her story with archivists just as her parents did earlier.

“We considered ourselves fortunate,” Margaret told interviewer Evelyn Taylor with the California State University Japanese American Digitization Project in 2003. (This article for Omaha Magazine merged excerpts from that oral history with original interviews conducted over the telephone and

e-mail correspondence.)

There are occasions when Marilyn’s internment past comes up in casual conversation. “It is amazing how few people know about this,” she says. “It is now mentioned in history books in schools, but it wasn’t for a long time.”

When she brings up her Boys Town interlude, she says, “It is always a surprise and I am asked many questions.”

The retired medical assistant, educator, and author now runs family foundations supporting youth activities. She credits her many accomplishments to what the wartime years took away and bestowed.

“The internment made me an overachiever. Because I was the eldest and experienced so much, I have become actually the strongest of the siblings,” she says. “Nothing can stop me from reaching my goals.”

Her late parents also felt that the experience strengthened the family’s resilience. Margaret said, “I think from then on we were very strong. I don’t think anything could get us down.”

The kindness shown by Boys Town to relieve their plight made a deep impact.

“We are forever grateful Father Flanagan hired my father to take care of the grounds,” Marilyn says, “because it enabled us to get out of that internment situation.”

She came to view what Flanagan did for her family and others who had been interned as a humanitarian “rescue.”

Then there were the scholastic and life lessons learned.

“A Boys Town education gives you the tools needed to succeed in life,” she says.

Even though discrimination continued after the war, the lessons she learned during the internment and the Boys Town reprieve emboldened her.

“I am grateful that I went through the experience because it made me who I am today,” she adds.

Internees were granted reparations by the U.S. government under the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Marilyn received $20,000, and she gave it all away.

She divided the reparations money into equal parts for four recipients: two younger siblings who also grew up in poverty (but did not experience the internment camps of World War II), to create the Fordney Foundation (for helping future generations of ballroom dancers), and Boys Town.

Forty-four years after the Takahashis left their safe haven in Nebraska, Marilyn returned to Boys Town in 1991. During the visit, she made her donation to the place that gave her family a temporary home and renewed faith in mankind.

Uchiyamada and Takahashi families with Father Flanagan in March 1944

James Takahashi’s Letter to Father Flanagan

Soon after arriving at Santa Anita Assembly Center, James Takahashi learned that Father Flanagan was hiring individuals with certain skills to work at Boys Town.

James hand-wrote an appeal to Flanagan asking to be considered. He provided references. The priest wrote Takahashi back requesting more information, including how many were in his family, and checked his references, all of whom spoke highly of “Jimmy,” as he was called, in letters they sent Flanagan.

Here is the text of the original letter James wrote (references excluded):

Dear Father Flanagan,

Today in camp I heard that you are asking for some Japanese gardeners. I am very interested as I have been a gardener and nurseryman in Los Angeles for the past five years.

Just before the evacuation, I was gardener at St. Mary’s Academy in Los Angeles. I re-landscaped the grounds and put in several lawns.

I am 30 years old of Japanese ancestry but was born and educated in this country. I was converted to the Catholic faith by my wife, who is half Irish and half Japanese.

I studied soil, plants, insect control, and landscape architecture at Los Angeles City College, and am confident that I would be able to handle any gardening problem.

I would be so grateful if you would consider me for this position.

Very sincerely,

James Takahashi

Visit csujad.com for more information about the California State University Japanese-American History Digitization Project.

Visit boystown.org for more information about Boys Town.

This article was printed in the November/December 2018 edition of 60Plus in Omaha Magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.

Toshio “James” and Margaret Takahashi with their children at the Boys Town Farm, 1944

The healthcare war: Round and round it goes again, and where it stops, nobody knows

The healthcare war:

Round and round it goes again, and where it stops, nobody knows

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the August 2017 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

As we go to press with this issue, the Republican-led attempt to repeal and replace Obamacare struggles on..

One of the most controversial things the GOP plan broached was severely cutting Medicaid, the nation’s largest health care program. Critics see it as an entitlement grown far beyond its original scope. Most recipients are children, mothers, the disabled and the elderly. The proposed $770 billion cut – spread out over several years – would have impacted millions, particularly the working poor in rural regions, who account for many of those added to the rolls through the ACA’s Medicaid expansion.

One World Community Health Centers CEO Andrea Skolkin said far from an automatic hand-out, qualifying for Medicaid is actually “very difficult.” She added, “There’s a lot of myths about Medicaid and who’s eligible to be enrolled. If you’re an able-bodied adult, you’re not really eligible. You really have to be an advocate for yourself in getting enrolled with all the paperwork because you have to prove your income. It’s an arduous process.”

The program, said Skolkin, places severe limits on not only eligibility, but coverage for certain things. Any tightening of eligibility and reduction of spending, she said, would result in even less access to care.

“As Medicaid ratchets down what it pays to providers, providers are less likely to want to accept Medicaid and so this vulnerable population doesn’t have as much choice of provider of where to get care, and that’s a problem.”

Currently, one in five Americans is enrolled in the program. In Nebraska, which refused Medicaid expansion, one in eight or some 230,000 people are enrolled. Skolkin estimates about 70,000 Nebraskans fall in the gaps – either not eligible for the marketplace or not covered by a private plan or by Medicaid.

Nebraska Methodist Health System vice president and CFO Jeff Francis was most troubled that “draconian cuts” to Medicaid were even on the table for so long.

“The thing that still looms out there that bothers me is that there wasn’t much budge on that,” Francis said. “I understand the partisan divisions on that, but at the end of the day that degree of cut to Medicaid is going to really impact individuals and individuals’ coverage. In Nebraska we get a bit of a double whammy, no matter what happens with the cuts because, one, we weren’t a Medicaid expansion state, so we’ve not benefited at all from some of the expanded coverage in federal dollars that went along with that. And, two, historically we’ve been lower on the Medicaid spending spectrum, and so as that translates into cuts and block grants for the states, Nebraska’s going to get hit pretty hard.”

Medicaid is crucial for millions getting treatment for maladies, and Skolkin said, “It also has an impact on long-term care in a tremendous way.”

Low weight new babies, infant mortality, STD and teen pregnancy rates are at crisis levels. The opioid epidemic got highlighted in the recent care plan debates. Mental illness is increasingly recognized as an acute public health problem. In the proposed Medicaid cut, some public schools would have lost funding for screenings and other care that students from low income families rely on.

In this high needs scenario, cutting access to care means some people will delay or defer treatment, and those with conditions that could be prevented or controlled will get sicker, while others will seek care in emergency rooms, all of which puts more pressure on providers. The system’s closely interwoven nature is such that pulling hard on one strand, like public health, will fray or undo other strands in this fragile crazy quilt.

“The tapestry doesn’t work without all the threads,” said One World pediatric nursing practitioner Sara Miller.

Nebraska Medicine CEO Dr. Daniel DeBehnke appreciates how those outside the industry often fail to see just what a tightly-knit fabric it is.

“I don’t know if it’s a disconnect or just a reflection of the complexity of it,” DeBehnke said.

In the event of cuts, he said, “low income individuals are going to need to make really tough choices about how to pay for a roof over their head and feed their family and pay for healthcare, and some may put off healthcare, and that has several domino effects. People become less healthy and when they do access healthcare, they require more services. Once they do require services, a lot of that financial burden gets shifted to the facilities caring for them, be it a local clinic, provider or large health system.”

Sara Miller envisions “life expectancy decreasing because you don’t have the opportunity to intervene in the early years, especially for kids to have healthy habits, and to do preventive medicine, so that folks don’t have diabetes or high cholesterol by the time they’re in their mid-20s.” She added, “My fear most is for the families that it affects and their deciding between food and electricity and healthcare. That’s a decision nobody should ever have to make.”

Exacerbating it all, DeBehnke said, is the “skyrocketing” cost of care.

“We should be focusing on that as well and not just in cutting the dollars that go for healthcare – but how can we decrease the cost of healthcare, the cost of prescription drugs driving a lot of the cost. How can we drive healthcare systems like ours and others to be more efficient and cost-conscious. We’re working on that every single day because we know that’s how we’re going to be paid in the future,” DeBehnke said. “But there are all those other things we should be working on as well so that we pay less for healthcare as opposed to just giving less money for healthcare.”

No matter where this all lands, he said, “When we talk about Nebraska Medicine and our mission, we’ll take care of anybody that walks in our door. That’s who we are and that’s what we do and we’re big enough to be able to do that.”

As a Federally Qualified Health Center, One World takes anyone, too, but it doesn’t have as deep of pockets as Nebraska Medicine.

“When we have increases in numbers like we have seen – we cared for over 18,000 patients last year who were uninsured, which is more than half of all of our patients – that’s an increasing burden as an organization in trying to leverage other funds so we can take care of all people,” Skolkin said. “If Medicaid reduces what it reimburses for certain services, again that’s a reduction to every provider, including us. So, whether you need an x-ray or some lab work. as things get reduced we get less payment for that and then it just has a ripple effect.

“So, cuts do impact us and at some point we won’t be able to provide the extent of care we provide. I would hate to see that happen, but at some point you have to be able to make your budget.”

DeBehnke said no matter what happens, “there’s going to be people left behind,” adding, “The idea that I hope legislators are thinking about is how do we leave the least amount behind.”

Jeff Francis said this is no time to be complacent even as Nebraska Methodist Health System is “operating well under the Affordable Care Act.” He added, “It took some time for us to be able to understand it. We’re now into the fourth year of the federal exchanges and the insurance aspects of it. Other parts of it we’ve been operating under for about six years. And so it’s going on. We’re seeing better outcomes because the focus is on quality and outcomes as opposed to just the fee for service or being paid for services.”

But just as the ACA was never meant to be a panacea for all the system’s faults, Francis said major cuts to public health would have negative consequences.

“To the extent there are less insured and so people are doing less preventive, that would be a step backwards from a public health standpoint. We still have the vulnerable populations – those with chronic conditions, in some cases multiple chronic conditions, those with mental health challenges, the working poor.”

Methodist Health and others are working to fill the gaps where they can.

“We’re reaching out to try and address that,” Francis said “by opening up a community health center in downtown Omaha to work with other entities-services to reach vulnerable populations. That center is going to have Lutheran Family Services associated with it to try to deal with that behavioral health component.”

The center is part of the Kountze Commons project on the former KETV site at 26th and Douglas. It’s an expansion of existing Kountze Memorial Lutheran Church health and food services.

Andy Hale, Vice President of Advocacy for the Nebraska Hospital Association, said his organization has been lobbying the state’s congressional delegation to “ensure all Americans can access the compassionate, patient-centered and affordable healthcare they deserve.”

“Nebraska’s hospitals serve as the safety net in each of their communities,” Hale said.

Hospital programs benefit the state, he said, by “providing free care to individuals unable to pay, absorbing the unpaid costs of public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid,” as well as “subsidizing health services reimbursed at amounts below the cost of providing the care … and incurring bad debt from individuals that choose not to pay their bills,” according to Hale.

Hale said hospitals serving more rural regions typically to treat “older, poorer, sicker populations” who tend to be on Medicare or Medicaid.

“Medicaid plays a critical role for Americans who live in small towns and rural areas,” Hale said. “Almost half of all children living in small towns and rural areas receive their health coverage through Medicaid. Research shows Medicaid provides families with access to necessary health services.”

He said any drastic cuts will be felt most in rural areas.

“Many hospital margins are already thin, but when you begin cutting reimbursement rates, it hits their bottom lines and drives those hospitals to significant losses.”

One World’s Andrea Skolkin said even in this repeal and replace mania, vital aspects of public care should not be lost in the shuffle.

“The expansion of Medicaid funding for children through CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) expires on September 30. All of these things are tied together.”

DeBehnke would like whatever process follows this latest effort to undo the ACA to be deliberate.

“President Trump said at the beginning of all this, ‘Who would have thought this was so complex?’ Well, we’ve all known it’s this complex and we’ve been trying to warn it’s this complex all along,” DeBehnke said. “As opposed to rushing to try to get something done because it was a campaign promise lawmakers made to their constituents, let’s take our time and try to figure it out and get it right. Obamacare wasn’t perfect either. There are good things we can pull from there that are in the right direction.”

Behind-the-scenes, executives like DeBehnke and Francis are bending elected officials’ ears.

“We’re wanting to make sure legislators and policymakers keep that longer view perspective. I think that’s coming out in some of the town halls the senators and congressman are hearing,” Francis said.

Meanwhile, the leadership of Nebraska Medicaid is in transition. Longtime director Calder Lynch left for a federal job in May. Former deputy director Rocky Thompson is serving as interim head until a permanent replacement is found.

Andrea Skolkin is unsettled, too, by the unknown but feels something like universal care will emerge and retain a public health haven.

“We are having those conversations – trying to make our representatives aware of the patient base we care for and what the impacts of cuts would be. Many of our patients, almost all of them, fall into this vulnerable bracket. If you cut too hard, then that social compact becomes less available for the people that need it most.

“I do believe there will be something for everyone. I think Medicaid is still going to be there. There’s a lot of argument-dialogue going around right now. It hasn’t been as productive as it could be. But I am hopeful it will end in the right place. Whether the Affordable Care Act is repealed or not, there has to be a safety net in place for people who are more vulnerable.”

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

Life Itself XVI: Social justice, civil rights, human services, human rights, community development stories

Life Itself XVI:

Social justice, civil rights, human services, human rights, community development stories

Unequal Justice: Juvenile detention numbers are down, but bias persists

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/09/unequal-justice-…ut-bias-persists

To vote or not to vote

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/06/01/to-vote-or-not-to-vote/

North Omaha rupture at center of PlayFest drama

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/04/30/north-omaha-rupt…f-playfest-drama/

Her mother’s daughter: Charlene Butts Ligon carries on civil rights legacy of her late mother Evelyn Thomas Butts

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/28/her-mothers-daug…lyn-thomas-butts/

Brenda Council: A public servant’s life

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/26/brenda-council-a…ic-servants-life

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/11/17/the-urban-league…-strong-in-omaha/

Park Avenue Revitalization and Gentrification: InCommon Focuses on Urban Neighborhood

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/02/25/park-avenue-revi…ban-neighborhood/

Health and healing through culture and community

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/11/17/health-and-heali…re-and-community

Syed Mohiuddin: A pillar of the Tri-Faith Initiative in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/09/01/syed-mohiuddin-a…tiative-in-omaha

Re-entry prepares current and former incarcerated individuals for work and life success on the outside

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/10/re-entry-prepare…s-on-the-outside/

Frank LaMere: A good man’s work is never done

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/07/11/frank-lamere-a-g…rk-is-never-done

Behind the Vision: Othello Meadows of 75 North Revitalization Corp.

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/27/behind-the-visio…italization-corp

North Omaha beckons investment, combats gentrification

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/25/north-omaha-beck…s-gentrification

SAFE HARBOR: Activists working to create Omaha Area Sanctuary Network as refuge for undocumented persons in danger of arrest-deportation

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/29/safe-harbor-acti…rest-deportation

Heartland Dreamers have their say in nation’s capitol

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/24/heartland-dreame…-nations-capitol/

Of Dreamers and doers, and one nation indivisible under…

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/21/of-dreamers-and-…ndivisible-under/

Refugees and asylees follow pathways to freedom, safety and new starts

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/21/refugees-and-asy…y-and-new-starts

Coming to America: Immigrant-Refugee mosaic unfolds in new ways and old ways in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/10/coming-to-americ…ld-ways-in-omaha

History in the making: $65M Tri-Faith Initiative bridges religious, social, political gaps

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/25/history-in-the-m…l-political-gaps

A systems approach to addressing food insecurity in North Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/08/11/a-systems-approa…y-in-north-omaha

No More Empty Pots Intent on Ending North Omaha Food Desert

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/13/no-more-empty-po…t-in-north-omaha

Poverty in Omaha:

Breaking the cycle and the high cost of being poor

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/01/03/poverty-in-omaha…st-of-being-poor/

Down and out but not done in Omaha: Documentary surveys the poverty landscape

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/11/03/down-and-out-but…overty-landscape

Struggles of single moms subject of film and discussion; Local women can relate to living paycheck to paycheck

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/10/24/the-struggles-of…heck-to-paycheck

Aisha’s Adventures: A story of inspiration and transformation; homelessness didn’t stop entrepreneurial missionary Aisha Okudi from pursuing her goals

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/07/10/aisha-okudis-sto…rsuing-her-goals

Omaha Community Foundation project assesses the Omaha landscape with the goal of affecting needed change

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/10/omaha-community-…ng-needed-change/

Nelson Mandela School Adds Another Building Block to North Omaha’s Future

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/01/24/nelson-mandela-s…th-omahas-future

Partnership 4 Kids – Building Bridges and Breaking Barriers

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/06/03/partnership-4-ki…reaking-barriers

Changing One Life at a Time: Mentoring Takes Center Stage as Individuals and Organizations Make Mentoring Count

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/01/05/changing-one-lif…-mentoring-count/

Where Love Resides: Celebrating Ty and Terri Schenzel

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/02/where-love-resid…d-terri-schenzel/

North Omaha: Voices and Visions for Change

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/29/north-omaha-voic…sions-for-change

Black Lives Matter: Omaha activists view social movement as platform for advocating-making change

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/08/26/black-lives-matt…ng-making-change

Change in North Omaha: It’s been a long time coming for northeast Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/08/01/change-in-north-…-northeast-omaha/

Girls Inc. makes big statement with addition to renamed North Omaha center

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/23/girls-inc-makes-…rth-omaha-center

NorthStar encourages inner city kids to fly high; Boys-only after-school and summer camp put members through their paces

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/06/17/northstar-encour…ough-their-paces/

Big Mama, Bigger Heart: Serving Up Soul Food and Second Chances

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/10/17/big-mama-bigger-…d-second-chances/

When a building isn’t just a building: LaFern Williams South YMCA facelift reinvigorates community

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/08/03/when-a-building-…-just-a-building/

Identity gets new platform through RavelUnravel

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/03/20/identity-gets-a-…ugh-ravelunravel/

Where Hope Lives, Hope Center for Kids in North Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/where-hope-lives…s-in-north-omaha/

Crime and punishment questions still surround 1970 killing that sent Omaha Two to life in prison

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/03/30/crime-and-punish…o-life-in-prison/

A WASP’s racial tightrope resulted in enduring book partially set in 1960s Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/28/a-wasps-racial-t…t-in-1960s-omaha/

Gabriela Martinez:

A heart for humanity and justice for all

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/08/16878

Father Ken Vavrina’s new book “Crossing Bridges” charts his life serving others

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/29/father-ken-vavri…e-serving-others/

Wounded Knee still battleground for some per new book by journalist-author Stew Magnuson

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/04/20/wounded-knee-sti…or-stew-magnuson

‘Bless Me, Ultima’: Chicano identity at core of book, movie, movement

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/09/14/bless-me-ultima-…k-movie-movement

Finding Normal: Schalisha Walker’s journey finding normal after foster care sheds light on service needs

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/07/18/finding-normal-s…on-service-needs/

Dick Holland remembered for generous giving and warm friendship that improved organizations and lives

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/08/dick-holland-rem…ations-and-lives/

Justice champion Samuel Walker calls It as he sees it

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/30/justice-champion…it-as-he-sees-it

![[© Ellen Lake]](https://i0.wp.com/www.crmvet.org/crmpics/64fs_gulfport1.jpg)

Photo caption:

Walker on far left of porch of a Freedom Summer

El Puente: Attempting to bridge divide between grassroots community and the system

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/22/el-puente-attemp…y-and-the-system

All Abide: Abide applies holistic approach to building community; Josh Dotzler now heads nonprofit started by his parents

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/12/05/all-abide-abide-…d-by-his-parents/

Making Community: Apostle Vanessa Ward Raises Up Her North Omaha Neighborhood and Builds Community

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/13/making-community…builds-community/

Collaboration and diversity matter to Inclusive Communities: Nonprofit teaches tools and skills for valuing human differences

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/09/collaboration-an…uman-differences

Talking it out: Inclusive Communities makes hard conversations the featured menu item at Omaha Table Talk

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/02/talking-it-out-i…omaha-table-talk/

Everyone’s welcome at Table Talk, where food for thought and sustainable race relations happen over breaking bread together

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/16/everyones-welcom…g-bread-together/

Feeding the world, nourishing our neighbors, far and near: Howard G. Buffett Foundation and Omaha nonprofits take on hunger and food insecurity

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/11/22/feeding-the-worl…-food-insecurity

Rabbi Azriel: Legacy as social progressive and interfaith champion secure

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/15/rabbi-azriel-leg…-champion-secure

Rabbi Azriel’s neighborhood welcomes all, unlike what he saw on recent Middle East trip; Social justice activist and interfaith advocate optimistic about Tri-Faith campus

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/09/06/rabbi-azriels-ne…tri-faith-campus/

Ferial Pearson, award-winning educator dedicated to inclusion and social justice, helps students publish the stories of their lives

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/25/ferial-pearson-a…s-of-their-lives/

Upon This Rock: Husband and Wife Pastors John and Liz Backus Forge Dynamic Ministry Team at Trinity Lutheran

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/02/upon-this-rock-h…trinity-lutheran/

Gravitas – Gravity Center for Contemplative Activism founders Christopher and Phileena Heuertz create place of healing for healers

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/04/01/gravitas-gravity…ling-for-healers/

Art imitates life for “Having Our Say” stars, sisters Camille Metoyer Moten and Lanette Metoyer Moore, and their brother Ray Metoyer

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/05/art-imitates-lif…ther-ray-metoyer

Color-blind love:

Five interracial couples share their stories

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/06/color-blind-love…re-their-stories

A Decent House for Everyone: Jesuit Brother Mike Wilmot builds affordable homes for the working poor through Gesu Housing

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/09/a-decent-house-f…ugh-gesu-housing

Bro. Mike Wilmot and Gesu Housing: Building Neighborhoods and Community, One House at a Time

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/04/27/bro-mike-wilmot-…-house-at-a-time/

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/04/01/omaha-native-ste…of-omaha-central/

Anti-Drug War manifesto documentary frames discussion:

Cost of criminalizing nonviolent offenders comes home

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/02/01/an-anti-drug-war…nders-comes-home

Documentary shines light on civil rights powerbroker Whitney Young: Producer Bonnie Boswell to discuss film and Young

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/03/21/documentary-shin…e-film-and-young

Civil rights veteran Tommie Wilson still fighting the good fight

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/05/07/civil-rights-vet…g-the-good-fight

Rev. Everett Reynolds Gave Voice to the Voiceless

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/18/rev-everett-reyn…to-the-voiceless/

Lela Knox Shanks: Woman of conscience, advocate for change, civil rights and social justice champion

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/04/lela-knox-shanks…ocate-for-change

Omahans recall historic 1963 march on Washington

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/12/omahans-recall-h…ch-on-washington

Psychiatrist-Public Health Educator Mindy Thompson Fullilove Maps the Root Causes of America’s Inner City Decline and Paths to Restoration

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/04/psychiatrist-pub…s-to-restoration/

A force of nature named Evie:

Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/16/a-force-of-natur…e-advocate-at-99

Home is where the heart Is for activist attorney Rita Melgares

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/20/home-is-where-th…ey-rita-melgares/

Free Radical Ernie Chambers subject of new biography by author Tekla Agbala Ali Johnson

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/12/05/free-radical-ern…bala-ali-johnson

Carolina Quezada leading rebound of Latino Center of the Midlands

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/03/carolina-quezada…-of-the-midlands/

Returning To Society: New community collaboration, research and federal funding fight to hold the costs of criminal recidivism down

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/02/returning-to-soc…-recidivism-down

Getting Straight: Compassion in Action expands work serving men, women and children touched by the judicial and penal system

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/05/22/getting-straight…and-penal-system

OneWorld Community Health: Caring, affordable services for a multicultural world in need

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/09/oneworld-communi…al-world-in-need

Dick Holland responds to far-reaching needs in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/dick-holland-res…g-needs-in-omaha/

Gender equity in sports has come a long way, baby; Title IX activists-advocates who fought for change see much progress and the need for more

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/06/11/gender-equity-in…he-need-for-more/

Giving kids a fighting chance: Carl Washington and his CW Boxing Club and Youth Resource Center

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/12/03/giving-kids-a-fi…-resource-center/

Beto’s way: Gang intervention specialist tries a little tenderness

http://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/28/betos-way-gang-i…ittle-tenderness/

Saving one kid at a time is Beto’s life work

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/01/24/saving-one-kid-a…-betos-life-work

Community trumps gang in Fr. Greg Boyle’s Homeboy model

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/21/community-trumps…es-homeboy-model/

Born again ex-gangbanger and pugilist, now minister, Servando Perales makes Victory Boxing Club his mission church for saving youth from the streets

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/12/19/born-again-ex-ga…from-the-streets/

Turning kids away from gangs and toward teams in South Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/17/turning-kids-awa…s-in-south-omaha/

“Paco” proves you can come home again

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/09/paco-proves-you-…-come-home-again

Two graduating seniors fired by dreams and memories, also saddened by closing of school, St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/05/11/two-graduating-s…igh-in-omaha-neb/

St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High: A school where dreams matriculate

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/st-peter-claver-…eams-matriculate/

Open Invitation: Rev. Tom Fangman engages all who seek or need at Sacred Heart Catholic Church

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/01/09/an-open-invitati…-catholic-church/

Outward Bound Omaha uses experiential education to challenge and inspire youth

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/26/outward-bound-om…nd-inspire-youth

After steep decline, the Wesley House rises under Paul Bryant to become youth academy of excellence in the inner city

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/27/after-a-steep-de…n-the-inner-city

Freedom riders: A get on the bus inauguration diary

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/10/21/get-on-the-bus-a…-ride-to-freedom/

The Great Migration comes home: Deep South exiles living in Omaha participated in the movement author Isabel Wilkerson writes about in her book, “The Warmth of Other Suns”

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/03/31/the-great-migrat…th-of-other-suns/

When New Horizons dawned for African-Americans seeking homes in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/01/17/when-new-horizon…ericans-in-omaha/

Good Shepherds of North Omaha: Ministers and churches making a difference in area of great need

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/04/the-shepherds-of…ea-of-great-need

Academy Award-nominated documentary “A Time for Burning” captured church and community struggle with racism

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/12/15/a-time-for-burni…ggle-with-racism/

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/03/08/letting-1000-flo…in-the-maelstrom

Coloring History:

A long, hard road for UNO Black Studies

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/25/coloring-history…no-black-studies

Two Part Series: After Decades of Walking Behind to Freedom, Omaha’s African-American Community Tries Picking Up the Pace Through Self-Empowered Networking

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/13/two-part-series-…wered-networking

Power Players, Ben Gray and Other Omaha African-American Leaders Try Improvement Through Self-Empowered Networking

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/09/power-players-be…wered-networking/

Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/04/native-omahans-t…n-their-hometown

Overarching plan for North Omaha development now in place: Disinvested community hopeful long promised change follows

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/29/overarching-plan…d-change-follows/

Standing on Faith, Sadie Bankston Continues One-Woman Vigil for Homicide Victim Families

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/standing-on-fait…-victim-families/

Forget Me Not Memorial Wall

North Omaha champion Frank Brown fights the good fight

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/01/15/north-omaha-cham…s-the-good-fight/

Man on fire: Activist Ben Gray’s flame burns bright

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/09/02/ben-gray-man-on-fire/

Strong, Smart and Bold, A Girls Inc. Success Story

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/strong-smart-and…-girls-inc-story

What happens to a dream deferred?

John Beasley Theater revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun”

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/14/what-happens-to-…aisin-in-the-sun

Brown v. Board of Education:

Educate with an Even Hand and Carry a Big Stick

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/07/brown-v-board-of…arry-a-big-stick/

Fast times at Omaha’s Liberty Elementary: Evolution of a school

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/05/fast-times-at-om…tion-of-a-school/

New school ringing in Liberty for students

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/06/new-school-ringi…rty-for-students

Nancy Oberst: Pied Piper of Liberty Elementary School

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/06/nancy-oberst-the…lementary-school/

Tender Mercies Minister to Omaha’s Poverty Stricken

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/tender-mercies-m…poverty-stricken/

Community and coffee at Omaha’s Perk Avenue Cafe

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/community-and-co…perk-avenue-cafe/

Whatsoever You Do to the Least of My Brothers, that You Do Unto Me: Mike Saklar and the Siena/Francis House Provide Tender Mercies to the Homeless

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/01/whatsoever-you-d…t-you-do-unto-me/

Gimme Shelter: Sacred Heart Catholic Church Offers a Haven for Searchers

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/gimme-shelter-sa…en-for-searchers

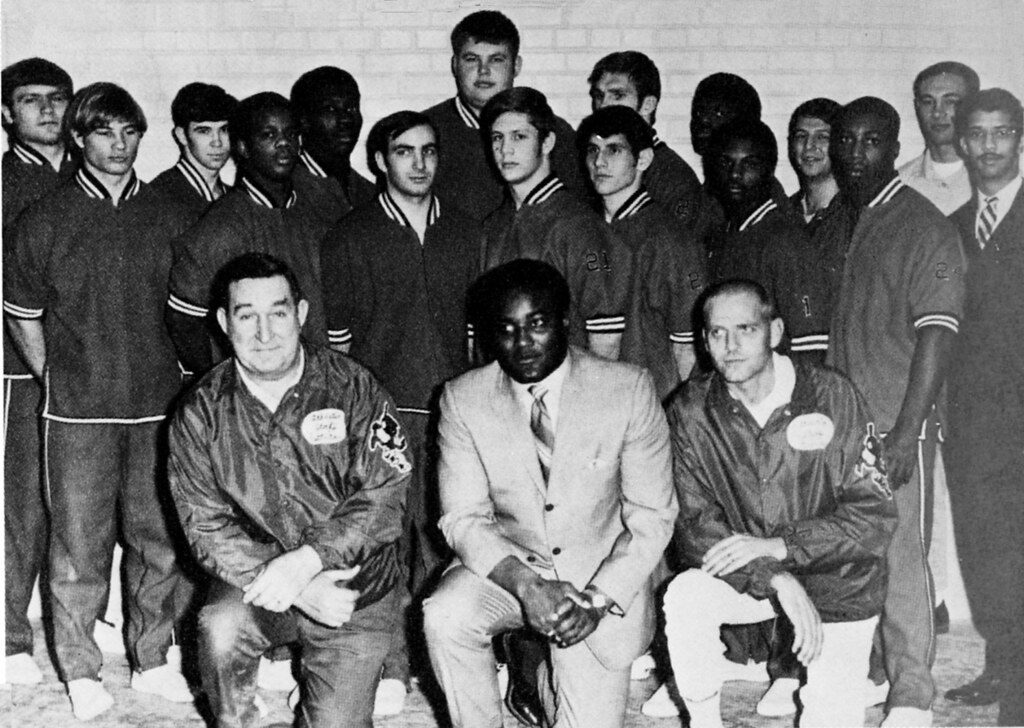

UNO wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/03/17/uno-wrestling-dy…-social-change-2

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/02/a-brief-history-…apher-rudy-smith/

Hidden In plain view: Rudy Smith’s camera and memory fix on critical time in struggle for equality

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/hidden-in-plain-…gle-for-equality/

Small but mighty group proves harmony can be forged amidst differences

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/11/14/small-but-mighty…idst-differences/

Winners Circle: Couple’s journey of self-discovery ends up helping thousands of at-risk kids through early intervention educational program

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/couples-journey-…-of-at-risk-kids

A Mentoring We Will Go

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/18/a-mentoring-we-will-go

Abe Sass: A mensch for all seasons

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/02/abe-sass-a-mensch-for-all-seasons

Shirley Goldstein: Cream of the Crop – one woman’s remarkable journey in the Free Soviet Jewry movement

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/05/shirley-goldstei…t-jewry-movement/

Flanagan-Monsky example of social justice and interfaith harmony still shows the way seven decades later

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/flanagan-monsky-…y-60-years-later/

A Contrary Path to Social Justice: The De Porres Club and the fight for equality in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/01/a-contrary-path-…quality-in-omaha/

Hey, you, get off of my cloud! Doug Paterson is acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed founder Augusto Boal and advocate of art as social action

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/03/hey-you-get-off-…as-social-action/

Doing time on death row: Creighton University theater gives life to “Dead Man Walking”

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/01/10/doing-time-on-de…dead-man-walking/

“Walking Behind to Freedom” – A musical theater examination of race

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/21/walking-behind-t…mination-of-race/

Bertha’s Battle: Bertha Calloway, the Grand Lady of Lake Street, struggles to keep the Great Plains Black History Museum afloat

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/11/berthas-battle

Leonard Thiessen social justice triptych deserves wider audience

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/01/21/leonard-thiessen…s-wider-audience/

Journalist-author Genoways takes micro and macro look at the U.S, food system

Journalist-author Genoways takes micro and macro look at the U.S, food system

©by Leo Adam Biga,

Originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Food & Spirits Magazine (http://fsmomaha.com)

It should come as no surprise that a writer who chronicled a year in the life of a Nebraska farm family, exposed the dangers of a broken American food system and is now researching Mexico’s tequila industry has always marched to the beat of a different drummer.

Growing up, Ted Genoways was encouraged to read books well beyond his years by his natural museum administrator father, Hugh H. Genoways. That was okay with the youngster because he liked reading, even though it took his dad makiing a bargain with him to replace comic books with classics.

The great American interpreter of the common man’s struggles, author John Steinbeck, became an inspiration for Genoways and remains so today. The exposes of muckrakers such as Upton Sinclair further lit a fire in him – that still burns – to stand up for the underdog.

“I just recently got fascinated by the work done by the ‘Stunt Girls,’ the forerunners of the muckrakers and the first undercover investigators. Their whole notion was to get into spaces hidden from public view and write about what was going on there in order to bring public pressure to bear and change conditions.”

Following in the footsteps of these socially conscious writers, Genoways has documented the hardships facing small farmers, migrants and immigrants and he’s explored the effects of big ag on towns and families.

Storytelling has captivated him for as long as he can remember. “Strangely fascinated” by the stories others told him, Genoways developed a habit of writing them down and illustrating them, a precursor to the student journalism he practiced in high school and college and to his career today as journalist and author.