Archive

Life Itself XI: Sports Stories from the 2000s

Life Itself XI:

Sports Stories from the 2000s

Giving a helping hand to Nebraska greats

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/08/giving-a-helping…-nebraska-greats/

The State of Volleyball: How Nebraska Became the Epicenter of American Volleyball

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/21/the-state-of-vol…rican-volleyball/

Huskers’ Winning Tradition: Surprise Return to the Top for Nebraska Volleyball

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/21/huskers-winning-…raska-volleyball/

An Omaha Hockey Legend in the Making: Jake Guentzel Reflects on Historic Rookie Season

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/07/10/an-omaha-hockey-…ic-rookie-season

Boxing coach Jose Campos molds young men

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/02/01/boxing-coach-jos…-molds-young-men

From couch potato to champion pugilist

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/11/22/from-couch-potat…hampion-pugilist

Living legend Tom Osborne still winning game of life at 79

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/10/27/living-legend-to…me-of-life-at-79/

The end of a never-meant-to-be Nebraska football dynasty has a school and a state fruitlessly pursuing a never-again-to-be-harnessed rainbow

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/03/26/the-end-of-a-nev…arnessed-rainbow/

Baseball and Soul Food at Omaha Rockets Kanteen

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/23/baseball-and-soul-food/

Soul food eatery Omaha Rockets Kanteen conjures Negro Leagues past and pot liquor love menu

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/11/17/soul-food-eatery…liquor-love-menu

A case of cognitive athletic dissonance

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/03/17/a-case-of-cognit…letic-dissonance/

Thoughts on recent gathering of Omaha Black Sports Legends

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/09/29/thoughts-on-rece…k-sports-legends/

From left, Bob Gibson, Marlin Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers and Ron Boone pose for a picture during a special dinner “An Evening With the Magician” honoring Marlin Briscoe at Baxter Arena on Thursday.

Marlin Briscoe: The Magician Finally Gets His Due

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/12/27/marlin-briscoe-t…lly-gets-his-due/

UPDATE TO: Marlin Briscoe finally getting his due

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/09/20/marlin-briscoe-f…-getting-his-due/

Marlin Briscoe: Still making history

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/12/10/marlin-briscoe-n…-of-fame-be-next/

Marlin Briscoe – An Appreciation

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/13/marlin-briscoe-an-appreciation

Pad man Esau Dieguez gets world champ Terence Crawford ready

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/04/25/pad-man-esau-die…e-crawford-ready

Some thoughts on the HBO documentary “My Fight” about Terence Crawford

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/07/12/some-thoughts-on…terence-crawford

Omaha warrior Terence Crawford wins again but his greatest fight may be internal

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/21/omaha-warrior-te…-may-be-internal

Terence “Bud” Crawford is Nebraska’s most impactful athlete of all-time

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/12/09/terence-bud-craw…lete-of-all-time/

.jpg)

©Photo by Mikey Williams/Top Rank

TERENCE CRAWFORD STAMPS HIS PLACE AMONG OMAHA GREATS

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/24/terence-crawford…ong-omaha-greats

This is what greatness looks like. Terence Crawford: Forever the People’s Champ

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/07/24/terence-crawford…he-peoples-champ

New approach, same expectation for South soccer

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/04/14/new-approach-sam…for-south-soccer/

South High soccer keeps pushing the envelope

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/06/south-high-socce…ing-the-envelope

Masterful: Joe Maass leads Omaha South High soccer evolution

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/04/24/masterful-joe-ma…soccer-evolution

The Chubick Way comes full circle with father-son coaching tandem at Omaha South

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/03/03/the-chubick-way-…m-at-omaha-south

A good man’s job is never done: Bruce Chubick honored for taking South to top

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/07/19/a-good-mans-job-…ing-south-to-top

Bruce Chubick builds winner at South: State title adds capstone to strong foundation

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/03/18/bruce-chubick-bu…trong-foundation

Storybook hoops dream turns cautionary tale for Omaha South star Aguek Arop

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/09/18/storybook-hoops-…-star-aguek-arop/

What if Creighton’s hoops destiny team is not the men, but the women?

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/08/what-if-creighto…en-but-the-women

Diversity finally comes to the NU volleyball program

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/11/14/diversity-finall…lleyball-program

Ann Schatz on her own terms – Veteran sportscaster broke the mold in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/03/30/ann-schatz-on-he…he-mold-in-omaha/

The Silo Crusher: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Trev Alberts

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/08/27/the-silo-crusher…ove-trev-alberts

Former Husker All-American Trev Alberts Tries Making UNO Athletics’ Slogan, ‘Omaha’s Team,’ a Reality

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/10/15/former-husker-al…s-team-a-reality

Omaha North superstar back Calvin Strong overcomes bigger obstacles than tacklers; Record-setting rusher poised to lead defending champion Vikings to another state title

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/08/29/omaha-north-supe…ther-state-title/

Having Survived War in Sudan, Refugee Akoy Agau Discovered Hoops in America and the Major College Recruit is Now Poised to Lead Omaha Central to a Third Straight State Title

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/03/01/having-survived-…ight-state-title

Dean Blais Has UNO Hockey Dreaming Big

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/01/29/dean-blais-has-u…key-dreaming-big

Gender equity in sports has come a long way, baby; Title IX activists-advocates who fought for change see much progress and the need for more

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/06/11/gender-equity-in…he-need-for-more

Omaha fight doctor Jack Lewis of two minds about boxing

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/06/21/omaha-fight-doct…nds-about-boxing

An Ode to Ali: Forever the Greatest

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/06/04/an-od-to-ali-forever-the-greatest

A Kansas City Royals reflection

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/06/01/a-kansas-city-royals-reflection

Bob Boozer, basketball immortal, posthumously inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/20/bob-boozer-baske…all-hall-of-fame/

Firmly Rooted: The Story of Husker Brothers

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/09/firmly-rooted-th…usker-brothers-2

Sparring for Omaha: Boxer Terence Crawford Defends His Title in the City He Calls Home

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/01/08/sparring-for-oma…ty-he-calls-home

The Champ looks to impact more youth at his B&B Boxing Academy

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/14/the-champ-looks-…ations-expansion/

The Champ Goes to Africa: Terence Crawford Visits Uganda and Rwanda with his former teacher, this reporter and friends

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/06/26/the-champ-goes-t…rter-and-friends

My travels in Uganda and Rwanda, Africa with Pipeline Worldwide’s Jamie Fox Nollette, Terence Crawford and Co.

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/08/01/my-travels-in-ug…-crawford-and-co

Omaha conquering hero Terence Crawford adds second boxing title to his legend; Going to Africa with The Champ; B&B Boxing Academy builds champions inside and outside the ring

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/04/21/omaha-conquering…outside-the-ring/

UNO hockey staking its claim

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/03/06/uno-hockey-staking-its-claim

Austin Ortega leads UNO hockey to new heights

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/03/05/austin-ortega-le…y-to-new-heights

Homegrown Joe Arenas made his mark in college and the NFL

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/03/05/homegrown-joe-ar…lege-and-the-nfl/

High-flying McNary big part of Creighton volleyball success; Senior outside hitter’s play has helped raise program stature

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/10/24/high-flying-mcna…-program-stature

Doug McDermott’s magic carpet ride to college basketball Immortality: The stuff of jegends and legacies

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/06/doug-mcdermotts-…nds-and-legacies/

UNO resident folk hero Dana Elsasser’s softball run coming to an end: Hard-throwing pitcher to leave legacy of overcoming obstacles

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/04/28/uno-resident-fol…coming-obstacles

HOMETOWN HERO TERENCE CRAWFORD ON VERGE OF GREATNESS AND BECOMING BOXING’S NEXT SUPERSTAR

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/23/hometown-hero-te…s-next-superstar

Terence “Bud” Crawford in the fight of his life for lightweight title: top contender from Omaha’s mean streets looks to make history

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/25/terence-bud-craw…-to-make-history

In his corner: Midge Minor is trainer, friend, father figure to pro boxing contender Terence “Bud” Crawford

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/07/30/in-his-corner-mi…nce-bud-crawford

Giving kids a fighting chance: Carl Washington and his CW Boxing Club and Youth Resource Center

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/12/03/giving-kids-a-fi…-resource-center/

JOHN C. JOHNSON: Standing Tall

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/14/john-c-johnson-standing-tall

Deadeye Marcus “Mac” McGee still a straight shooter at 100

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/03/15/deadeye-marcus-m…t-shooter-at-100

Rich Boys Town sports legacy recalled

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/rich-boys-town-s…-legacy-recalled/

The series and the stadium: CWS and Rosenblatt are home to the Boys of Summer

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/06/25/the-series-and-t…e-boys-of-summer

Hoops legend Abdul-Jabbar talks history

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/08/09/hoops-legend-abd…ar-talks-history

The man behind the voice of Husker football at Memorial Stadium

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/06/20/the-man-behind-t…memorial-stadium

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum exhibits on display for the College World Series;

In bringing the shows to Omaha the Great Plains Black History Museum announces it’s back

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/17/negro-leagues-ba…nounces-its-back

Steve Rosenblatt: A legacy of community service, political ambition and baseball adoration

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/27/steve-rosenblatt…seball-adoration/

Houston Alexander, “The Assassin”

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/22/houston-alexander-the-assassin

The Pit Boxing Club is Old-School Throwback to Boxing Gyms of Yesteryear

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/01/04/the-pit-boxing-c…ms-of-yesteryear

The Last Hurrah for Hoops Wizard Darcy Stracke

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/17/the-last-hurrah-…rd-darcy-stracke/

Going to Extremes: Professional Cyclist Todd Herriott

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/11/25/going-to-extreme…st-todd-herriott/

Danny Woodhead, The Mighty Mite from North Platte Makes Good in the NFL

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/10/05/danny-woodhead-t…-good-in-the-nfl/

Kenton Keith’s long and winding journey to football redemption

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/04/kenton-keiths-lo…tball-redemption/

One Peach of a Pitcher: Peaches James Leaves Enduring Legacy in the Circle as a Nebraska Softball Legend

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/10/one-peach-of-a-p…-softball-legend

Green Bay Packers All-Pro Running Back Ahman Green Channels Comic Book Hero Batman and Gridiron Icons Walter Payton and Bo Jackson on the Field

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/12/05/green-bay-packer…son-on-the-field

Ron Stander: One-time Great White Hope still making rounds for friends in need

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/ron-stander-stil…-friends-in-need

Buck O’Neil and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City Offer a Living History Lesson about the National Pastime from a Black Perspective

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/27/buck-o’neil-and-…lack-perspective

Memories of Baseball Legend Buck O’Neil and the Negro Leagues Live On

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/11/memories-of-buck…-leagues-live-on

My Midwest Baseball Odyssey Diary

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/11/my-midwest-baseball-odyssey-diary

Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/20/lifetime-friends…-black-citizenry

A Good Deal: George Pfeifer and Tom Krehbiel are the Ties that Bind Boys Town Hoops

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/a-good-deal-geor…-boys-town-hoops/

Tom Lovgren, A Good Man to Have in Your Corner

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/03/tom-lovgren-a-go…e-in-your-corner/

Omaha’s Fight Doctor, Jack Lewis, and His Boxing Cronies Weigh-in On Omaha Hosting the National Golden Gloves

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/20/omahas-fight-doc…al-golden-gloves/

The Fighting Hernandez Brothers

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/06/the-fighting-hernandez-brothers/

Redemption, A Boys Town Grad Tyrice Ellebb Finds His Way

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/06/redemption

Wright On, Adam Wright Has it All Figured Out Both On and Off the Football Field

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/06/wright-on

A Rosenblatt Tribute

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/19/a-rosenblatt-tribute

The Little People’s Ambassador at the College World Series

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/26/the-little-peopl…ege-world-series/

The Two Jacks of the College World Series

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/26/the-two-jacks-of…ege-world-series

UNO wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/03/17/uno-wrestling-dy…-social-change-2

Requiem for a Dynasty: UNO Wrestling

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/28/requiem-for-a-dy…ville-university/

UNO Wrestling Retrospective – Way of the Warrior, House of Pain, Day of Reckoning

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/21/a-three-part-uno…day-of-reckoning/

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/04/01/omaha-native-ste…of-omaha-central/

It’s a Hoops Culture at The SAL, Omaha’s Best Rec Basketball League

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/06/its-a-hoops-cult…asketball-league/

Born again ex-gangbanger and pugilist, now minister, Servando Perales makes Victory Boxing Club his mission church for saving youth from the streets

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/12/19/born-again-ex-ga…from-the-streets/

Fight Girl Autumn Anderson

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/fight-girl/

Brotherhood of the Ring, Omaha’s CW Boxing Club

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/19/brotherhood-of-the-ring/

Harley Cooper, The Best Boxer You’ve Never Heard Of

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/05/harley-cooper-th…e-never-heard-of/

Requiem for a Heavyweight, the Ron Stander Story

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/requiem-for-a-heavyweight/

When We Were Kings, A Vintage Pro Wrestling Story

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/04/when-we-were-kin…-wrestling-story/

Heart and Soul, A Mutt and Jeff Boxing Story

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/04/heart-and-soul/

The Downtown Boxing Club’s House of Discipline

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/04/the-downtown-box…se-of-discipline

Making the case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/03/27/making-the-case-…rts-hall-of-fame/

OUT TO WIN – THE ROOTS OF GREATNESS: OMAHA’S BLACK SPORTS LEGENDS

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/12/20/out-to-win-the-r…k-sports-legends/

Opening Installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness

An exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/10/from-my-series-o…k-sports-legends

Closing Installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness

An appreciation of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/10/closing-installm…k-sports-legends/

Bob Gibson, A Stranger No More (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/16/bob-gibson-a-stranger-no-more

Bob Gibson, the Master of the Mound remains his own man years removed from the diamond (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/18/bob-gibson-the-m…from-the-diamond/

My Brother’s Keeper, The competitive drive MLB Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson’s older brother, Josh, instilled in him (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/04/30/my-brothers-keep…instilled-in-him/

Johnny Rodgers, Forever Young, Fast, and Running Free (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/18/johnny-rodgers-f…ots-of-greatness/

Ron Boone, still an Iron Man after all these years (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/18/ron-boone-still-…ots-of-greatness

The Brothers Sayers: Big legend Gale Sayers and little legend Roger Sayers (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/15/the-brothers-say…end-roger-sayers/

Bob Boozer, Basketball Immortal (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/14/bob-boozer-basketball-immortal

Prodigal Son: Marlin Briscoe takes long road home (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/13/prodigal-son-mar…e-long-road-home/

Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/17/don-benning-man-…ots-of-greatness

Dana College Legend Marion Hudson, the greatest athlete you’ve never heard of before (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/14/marion-hudson-th…ots-of-greatness/

Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/12/09/soul-on-ice-man-…ots-of-greatness/

The Boxers – Sweet Scientists from The Hood (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win Series: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/08/11/from-my-series-o…ts-from-the-hood/

The Wrestlers – Masters in the Way of the Mat (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win Series: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/08/11/from-my-series-o…e-way-of-the-mat

A Brief History of Omaha’s Black, Urban, Inner-City Hoops Scene (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/06/25/from-my-series-o…city-hoops-scene/

Neal Mosser, A Straight-Shooting Son-of-a-Gun (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/06/16/from-my-series-o…ing-son-of-a-gun

Alexander the Great’s Wrestling Dynasty – Champion Wrestler and Coach Curlee Alexander on Winning (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/17/from-my-series-o…ander-on-winning

Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/10/from-the-series-…ark-in-athletics

Bob Boozer, basketball immortal, posthumously inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame

Bob Boozer, basketball immortal, posthumously inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame

I posted this four years ago about Bob Boozer, the best basketball player to ever come out of the state of Nebraska, on the occasion of his death at age 75. Because his playing career happened when college and pro hoops did not have anything like the media presence it has today and because he was overshadowed by some of his contemporaries, he never really got the full credit he deserved. After a stellar career at Omaha Tech High, he was a brilliant three year starter at powerhouse Kansas State, where he was a two-time consensus first-team All-American and still considered one of the four or five best players to ever hit the court for the Wildcats. He averaged a double-double in his 77-game career with 21.9 points and 10.7 rebounds. He played on the first Dream Team, the 1960 U.S. Olympic team that won gold in Rome. He enjoyed a solid NBA journeyman career that twice saw him average a double-double in scoring and rebounding for a season. In two other seasons he averaged more than 20 points a game. In his final season he was the 6th man for the Milwaukee Bucks only NBA title team. He received lots of recognition for his feats during his life and he was a member of multiple halls of fame but the most glaring omisson was his inexplicable exclusion from the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. Well, that neglect is finally being remedied this year when he will be posthumously inducted in November. It is hard to believe that someone who put up the numbers he did on very good KSU teams that won 62 games over three seasons and ended one of those regular seasons ranked No. 1, could have gone this long without inclusion in that hall. But Boozer somehow got lost in the shuffle even though he was clearly one of the greatest collegiate players of all time. Players joining him in this induction class are Mark Aguirre of DePaul, Doug Collins of Illinois State, Lionel Simmons of La Salle, Jamaal Wilkes of UCLA and Dominique Wilkins of Georgia. Good company. For him and them. Too bad Bob didn’t live to see this. If things had worked out they way they should have, he would been inducted years ago and gotten to partake in the ceremony.

I originally wrote this profile of Boozer for my Omaha Black Sports Legends Series: Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. You can access that entire collection at this link–

https://leoadambiga.com/out-to-win-the-roots-of-greatness-…/

I also did one of the last interviws Boozer ever gave when he unexpectedly arrived back stage at the Orpheum Theater in Omaha to visit his good buddy, Bill Cosby, with whom I was in the process of wrapping up an interview. When Boozer came into the dressing room, the photographer and I stayed and we got more of a story than we ever counted on. Here is a link to that piece–

Bill Cosby on his own terms: Backstage with the comedy legend and old friend Bob Boozer

JOHN C. JOHNSON: Standing Tall

None of us is perfect. We all have flaws and defects. We all make mistakes. We all carry baggage. Fairly or unfairly, those who enter the public eye risk having their imperfections revealed to the wider world. That is what happened to one of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends, John C. Johnson, who along with Clayton Bullard, led Omaha Central to back to back state basketball titles in the early 1970s. Both players got Division I scholarships to play ball: Johnson at Creighton and Bullard at Colorado. John C. had a memorable career for the Creighton Bluejays as a small forward who could play inside and outside equally well. He was a hybrid player who could slide and glide in creating his own shot and maneuver to the basket, where he was very adept at finishing, even against bigger opponents, but he could also mix it up when the going got tough or the situation demanded it. He was good both offensively and defensively and he was a fiine team player who never tried to do more than he was capable of and never played outside the system. He was very popular with fans.His biggest following probably came from the North Omaha African-American community he came out of and essentially never left. He was one of their own. That’s not insignificant either because CU has had a paucity of black players from Omaha over its long history. John C. didn’t make it in the NBA but he got right on with his post-collegiate life and did well away from the game and the fame. Years after John C. graduated CU his younger brother Michael followed him from Central to the Hilltop to play for the Jays and he enjoyed a nice run of his own. But when Michael died it broke something deep inside John C. that triggered a drug addction that he supported by committing a series of petty crimes that landed him in trouble with the law. These were the acts of a desperate man in need of help. He had trouble kicking the drug habit and the criminal activity but that doesn’t make him a bad person, only human. None of this should diminish what John C. did on and off the court as a much beloved student-athlete. He is a good man. He is also human and therefore prone to not always getting things right. The same can be said for all of us. It’s just that most of us don’t have our failings written or broadcast for others to see. John was reluctant to be profiled when I interviewed him and his then-life partner for this story about seven or eight years ago. But he did it. He was forthright and remorseful and resolved. After this story appeared there were more setbacks. It happens. Wherever you are, John, I hope you are well. Your story then and now has something to teach all of us. And thanks for the memories of all that gave and have as one of the best ballers in Nebraska history. No one can take that away.

NOTE: This story is one of dozens I have written for a collection I call: Out to Win – The Roots of Greatness: Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. You can find it on my blog, leoadambiga.com. Link to it directly at–

OUT TO WIN – THE ROOTS OF GREATNESS: OMAHA’S BLACK SPORTS LEGENDS

JOHN C. JOHNSON: Standing Tall

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

“I got tired of being tired.”

Omaha hoops legend and former Creighton University star John C. Johnson explained why he ended the pattern of drug abuse, theft and fraud that saw him serve jail and prison time before his release last May.

From a sofa in the living room of the north Omaha home he shares with his wife, Angela , who clung to him during a recent interview, he made no excuses for his actions. He tried, however, to explain his fall from grace and the struggle to reclaim his good name.

“Pancho” or “C,” as he’s called, was reluctant to speak out after what he saw as the media dogging his every arrest, sentencing and parole board hearing. The last thing he wanted was to rehash it all. But as one of the best players Omaha’s ever produced, he’s newsworthy.

“I had a lot of great players,” said his coach at Omaha Central High School, Jim Martin, “but I think ‘C’ surpassed them all. You would have to rate him as one of the top five players I’ve seen locally. He’d be right up there with Fred Hare, Mike McGee, Ron Kellogg, Andre Woolridge, Kerry Trotter… He was a man among boys.”

The boys state basketball championship Central won this past weekend was the school’s first in 31 years. The last ones before that were the 1974 and 1975 titles that Johnson led the Eagles to. Those clubs are considered two of the best in Omaha prep history. In the proceeding 30 years Central sent many fine teams down to Lincoln to compete for the state crown, but always came up short — until this year. It’s that kind of legacy that makes Johnson such an icon.

He’s come to terms with the fact he’s fair game.

“Obscurity is real important to me right now,” Johnson said. “I used to get mad about the stuff written about me, but, hey, it was OK when I was getting the good pub, so I guess you gotta take the good with the bad. Yeah, when I was scoring 25 points and grabbing all those rebounds, it’s beautiful. But when I’m in trouble, it’s not so beautiful.”

As a hometown black hero Johnson was a rarity at Creighton. Despite much hoops talent in the inner city, the small Jesuit school’s had few black players from Omaha in its long history.

There was a rough beauty to his fluid game. It was 40 minutes of hell for opponents, who’d wilt under the pressure of his constant movement, quick feet, long reach and scrappy play. He’d disrupt them. Get inside their heads. At 6-foot-3 he’d impose his will on guys with more height and bulk — but not heart.

“John C.’ s heart and desire were tremendous, and as a result he was a real defensive stopper,” said Randy Eccker, a sports marketing executive who played point guard alongside him at Creighton. “He had a long body and very quick athletic ability and was able to do things normally only much taller players do. He played more like he was [6-foot-6]. On offense he was one of the most skilled finishers I ever played with. When he got a little bit of an edge he was tremendous in finishing and making baskets. But the thing I remember most about John C. is his heart. He’d always step up to make the big plays and he always had a gift for bringing everybody together.”

Creighton’s then-head coach, Tom Apke, calls Johnson “a winner” whose “versatility and intangibles” made him “a terrific player and one of the most unique athletes I ever coached. John could break defenses down off the dribble and that complemented our bigger men,” Apke said. “He had an innate ability on defense. He also anticipated well and worked hard. But most of all he was a very determined defender. He had the attitude that he was not going to let his man take him.”

Johnson took pride in taking on the big dudes. “Here I was playing small forward at [6-foot-three] on the major college level and guarding guys [6-foot-8], and holding my own,” he said in his deep, resonant voice.

When team physician and super fan Lee “Doc” Bevilacqua and assistant coach Tom “Broz” Brosnihan challenged him to clean the boards or to shut down opponents’ big guns, he responded.

He could also score, averaging 14.5 points a game in his four-year career (1975-76, 1978-79) at CU. Always maneuvering for position under the bucket, he snatched offensive rebounds for second-chance points. When not getting put-backs, he slashed inside to draw a foul or get a layup and posted-up smaller men like he did back at Central, when he and Clayton Bullard led the Eagles to consecutive Class A state titles.

He modeled his game after Adrian Dantley, a dominant small forward at Notre Dame and in the NBA. “Yeah, A.D., I liked him,” Johnson said. “He wasn’t the biggest or flashiest player in the world, but he was one of the hardest working players in the league.” The same way A.D. got after it on offense, Johnson ratcheted it up on defense. “I was real feisty,” he said. “When I guarded somebody, hell if he went to the bathroom I was going to follow him and pick him up again at half-court. Even as a freshman at Creighton I was getting all the defensive assignments.”

Unafraid to mix it up, he’d tear into somebody if provoked. Iowa State’s Anthony Parker, a 6-foot-7, high-scoring forward, made the mistake of saying something disparaging about Johnson’s mother in a game.

“When he said something about my mama, that was it,” Johnson said. “I just saw fire and went off on him. Fight’s done, and by halftime I have two or three offensive rebounds and I’m in charge of him. By the end, he’s on the bench with seven points. Afterward, he came in our locker room and I stood up thinking he wanted to settle things. But he said, ‘I’m really sorry. I lost my head. I’m not ever going to say anything about nobody’s mama again. Man, you took me right out of my game.’”

Doing whatever it took — fighting, hustling, hitting a key shot — was Johnson’s way. “That’s just how I approached the game,” he said. He faced some big-time competition, too. He shadowed future NBA all-stars Maurice “Mo” Cheeks, a dynamo with West Texas State College; Mark Aguirre, an All-American with DePaul; and Andrew Toney, a scoring machine with Southwest Louisiana State. A longtime mentor of Johnson’s, Sam Crawford said, “And he was right there with them, too.”

He even had a hand in slowing down Larry Bird. Johnson and company held Larry Legend to seven points below his collegiate career scoring average in five games against Indiana State. The Jays won all three of the schools’ ’77-78 contests, the last (54-52) giving them the Missouri Valley Conference title. But ISU took both meetings in ’78-79, the season Bird led his team to the NCAA finals versus Magic Johnson’s Michigan State.

When “C” didn’t get the playing time he felt he deserved in a late season game his freshman year, Apke got an earful from Johnson’s father and from Don Benning, Central’s then-athletic director and a black sports legend himself. If the community felt one of their own got the shaft, they let the school know about it.

Expectations were high for Johnson — one of two players off those Central title teams, along with Clayton Bullard, to go Division I. His play at Creighton largely met people’s high standards. Even after his NBA stint with the Denver Nuggets, who drafted him in the 7th round, fizzled, he was soon a fixture again here as a Boys and Girls Club staffer and juvenile probation officer. That’s what made his fall shocking.

Friends and family had vouched for him. The late Dan Offenberger, former CU athletic director, said then: “He’s a quality guy who overcame lots of obstacles and got his degree. He’s one of the shining examples of what a young man can accomplish by using athletics to get an education and go on in his work.”

What sent Johnson off the deep end, he said, was the 1988 death of his baby brother and best friend, Michael, who followed him to Creighton to play ball. After being stricken with aplastic anemia, Michael received a bone marrow transplant from “C.” There was high hope for a full recovery, but when Michael’s liver was punctured during a biopsy, he bled to death.

“When he didn’t make it, I kind of took it personally,” Johnson said. “It was a really hard period for our family. It really hurt me. I still have problems with it to this day. That’s when things started happening and spinning out of control.”

He used weed and alcohol and, as with so many addicts, these gateway drugs got him hooked on more serious stuff. He doesn’t care to elaborate. Arrested after his first stealing binge, Johnson waived his right to a trial and admitted his offenses. He pleaded no contest and offered restitution to his victims.

His first arrests came in 1992 for a string of car break-ins and forgeries to support his drug habit. He was originally arrested for theft, violation of a financial transaction device, two counts of theft by receiving stolen propperty and two counts of criminal mischief. His crimes typically involved a woman accomplice with a fake I.D. Using stolen checks and credit cards, they would write a check to the fake name and cash it soon thereafter. He faced misdemanor and felony charges in Harrison County Court in Iowa and misdemeanor charges in Douglas County. He was convicted and by March 2003 he’d served about eight years behind bars.

He was released and arrested again. In March 2003 he was denied parole for failing to complete an intensive drug treatment program. Johnson argued, unsuccessfully, that his not completing the program was the result of an official oversight that failed to place his name on a waiting list, resulting in him never being notified that he could start the program.

Ironically, a member of the Nebraska Board of Parole who heard Johnson’s appeal is another former Omaha basketball legend — Bob Boozer, a star at Technical High School, an All-American at Kansas State and a member of the 1960 U.S. Olympic gold medal winning Dream Team and the 1971 Milwaukee Bucks NBA title team. Where Johnson’s life got derailed and reputation sullied, Boozer’s never had scandal tarnish his name.

After getting out on in the fall of 2003, Johnson was arrested again for similar crimes as before. The arrest came soon after he and other CU basketball greats were honored at the Bluejays’ dedication of the Qwest Center Omaha. He only completed his last stretch in May 2005. His total time served was about 10 years.

He ended up back inside more than once, he said, because “I wasn’t ready to quit.” Now he just wants to put his public mistakes behind him.

What Johnson calls “the Creighton family” has stood by him. When he joined other program greats at the Jays’ Nov. 22, 2003 dedication of the Qwest Center, the warm ovation he received moved him. He’s a regular again at the school’s old hilltop gym, where he and his buds play pickup games versus 25-year-old son Keenan and crew. He feels welcome there. For the record, he said, the old guys regularly “whup” the kids.

“It feels good to be part of the Creighton family again. They’re so happy for me. It’s kind of made me feel wanted again,” he said.

Sam Crawford, a former Creighton administrator and an active member of the CU family, said, “I don’t think we’ll ever give up on John C., because he gave so much of himself while he was there. If there’s any regret, it’s that we didn’t see it [drug abuse] coming.” Crawford was part of a contingent that helped recruit Johnson to CU, which wanted “C” so bad they sent one of the school’s all-time greats, Paul Silas, to his family’s house to help persuade him to come.

Angela, whom “C” married in 2004, convinced him to share his story. “I told him, ‘You really need to preserve the Johnson legacy — through the great times, your brief moment of insanity and then your regaining who you are and your whole person,’” she said. Like anyone who’s been down a hard road, Johnson’s been changed by the journey. Gone is what’s he calls the “attitude of indifference” that kept him hooked on junk and enabled the crime sprees that supported his habit. “I’ve got a new perspective,” he said. “My decision-making is different. It’s been almost six years since I’ve used. I’m in a different relationship.

Having a good time used to mean getting high. Not anymore. Life behind “the razor wire” finally scared him straight. ”They made me a believer. The penal system made me a believer that every time I break the law the chances of my getting incarcerated get greater and greater. All this time I’ve done, I can’t recoup. It’s lost time. Sitting in there, you miss events. Like my sister had a retirement party I couldn’t go to. My mother’s getting up in age, and I was scared there would be a death in the family and I’d have to come to the funeral in handcuffs and shackles. My son’s just become a father and I wouldn’t wanted to have missed that. Missing stuff like that scared the hell out of me.”

Johnson’s rep is everything. He wants it known what he did was out of character. That part of his past does not define him. “I’ve done some bad things, but I’m still a good person. You’ll find very few people that have anything bad to say about me personally,” he said. “You’ll mostly find sympathy, which I hate.” But he knows some perceive him negatively. “I don’t know if I’m getting that licked yet. If I don’t, it’s OK. I can’t do anything about that.”

He takes full responsibility for his crimes and is visibly upset when he talks about doing time with the likes of rapists and child molesters. “I own up to what I did,” he said. “I deserved to go to prison. I was out of control. But as much trouble as I’ve been in, I’ve never been violent. I never touched violence. The only fights I’ve had have been on the basketball court, in the heat of battle.”

He filled jobs in recent years via the correction system’s work release program. Shortly before regaining his freedom in May, he faced the hard reality any ex-con does of finding long-term work with a felony conviction haunting him. When he’d get to the part of an application asking, “Have you ever been convicted of a felony?” — he’d check, yes. Where it said, “Please explain,” he’d write in the box, “Will explain in the interview.” Only he rarely got the chance to tell his story.

Then his luck changed. Drake Williams Steel Company of Omaha saw the man and not the record and hired him to work the night shift on its production line. “I really appreciate them giving me an opportunity, because they didn’t have to. A lot of places wouldn’t. And to be perfectly honest, I understand that. This company is employee-oriented, and they like me. They’re letting me learn things.”

He isn’t used to the blue-collar grind. “All my jobs have been sitting behind a desk, pretty much. Now I’m doing manual labor, and it’s hard work. I’m scratched up. I work on a hydro saw. I weld. I operate an overhead crane that moves 3,000-pound steel beams. I’m a machine operator, a drill operator…”

The hard work has brought Johnson full circle with the legacy of his late father, Jesse Johnson, an Okie and ex-Golden Gloves boxer who migrated north to work the packing houses. “My father was a hard working man,” he said. “He worked two full-time jobs to support us. We didn’t have everything but we had what we needed. I’ve been around elite athletes, but my father, he was the strongest man I’ve ever known, physically, emotionally and mentally. He didn’t get past the 8th grade, but he was very well read, very smart.”

His pops was stern but loving. Johnson also has a knack with young people — he’s on good terms with his children from his first marriage, Keenan and Jessica — and aspires one day to work again with “kids on the edge.”

“I shine around kids,” he said. “I can talk to them at their level. I listen. There’s very few things a kid can talk about that I wouldn’t be able to relate to. I just hope I didn’t burn too many bridges. I would hate to think my life would end without ever being able to work with kids again. That’s one of my biggest fears. I really liked the Boys Club and the probation work I did, and I really miss that.”

He still has a way with kids. Johnson and a teammate from those ’74 and ’75 Central High state title teams spoke to the ‘05-’06 Central squad before the title game tipped off last Saturday. “C” told the kids that the press clippings from those championship years were getting awfully yellow in the school trophy case and that it was about time Central won itself a new title and a fresh set of clippings. He let them know that school and inner city pride were on the line.

He’s put out feelers with youth service agencies, hoping someone gives him a chance to . For now though he’s a steel worker who keeps a low profile. He loves talking sports with the guys at the barbershop and cafe. He works out. He plays hoops. Away from prying eyes, he visits Michael’s grave, telling him he’s sorry for what happened and swearing he won’t go back to the life that led to the pen. Meanwhile, those dearest to Johnson watch and wait. They pray he can resist the old temptations.

Crawford, whom Johnson calls “godfather,” has known him 35 years. He’s one of the lifelines “C” uses when things get hairy. “I know pretty much where he is at all times. I’m always reaching out for him … because I know it is not easy what he’s trying to do. He dug that hole himself and he knows he’s got to do what’s necessary. He’s got to show that he’s capable of changing and putting his life back together. He’s got to find the confidence and the courage and the faith to make the right choices. It’s going to take his friends and family to encourage him and provide whatever support they possibly can. But he’s a good man and he has a big heart.”

Johnson is adamant his using days are over and secure that his close family and tight friends have his back. “Today, my friends and I can just sit around and have a good time, talking and laughing, and it doesn’t have nothing to do with drugs or alcohol. There used to be a time for me you wouldn’t think that would be possible. I still see people in that lifestyle and I just pray for them.”

Besides, he said, “I’m tired of being tired.”

Alexander the Great’s Wrestling Dynasty – Champion Wrestler and Coach Curlee Alexander on Winning (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

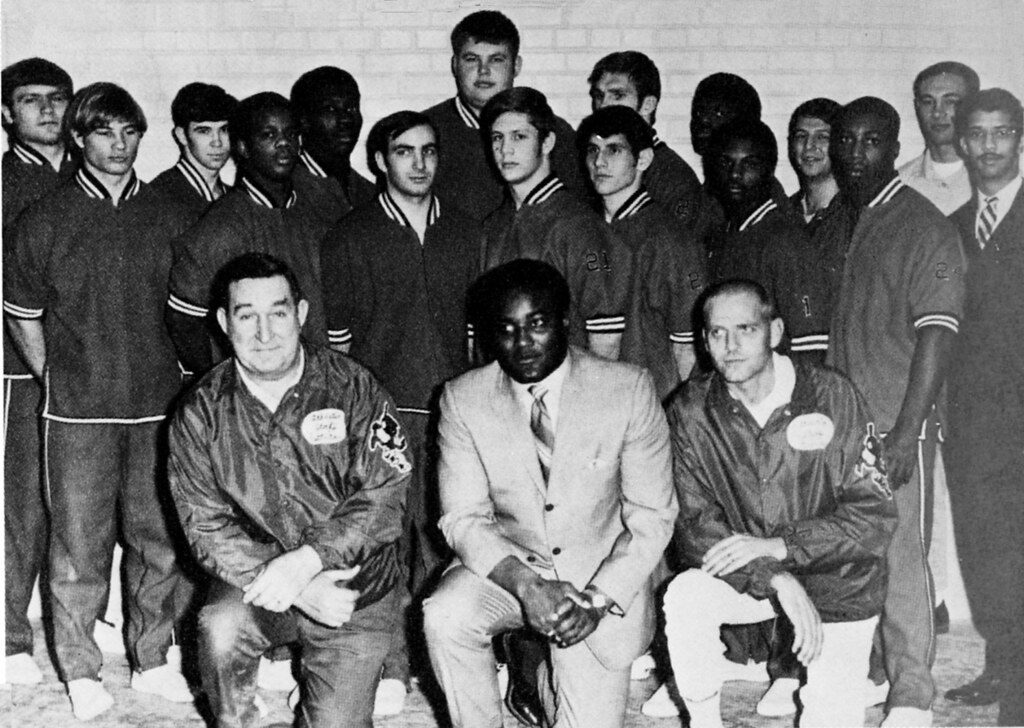

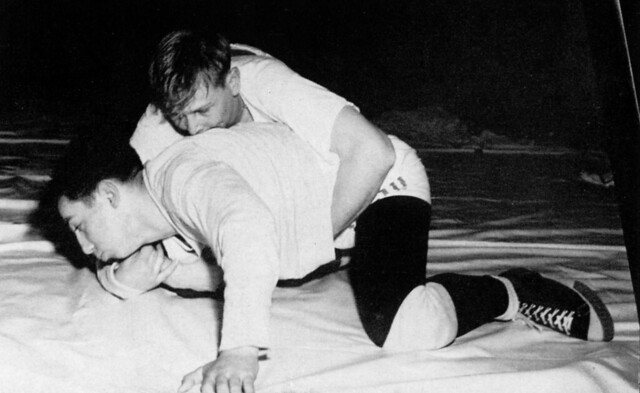

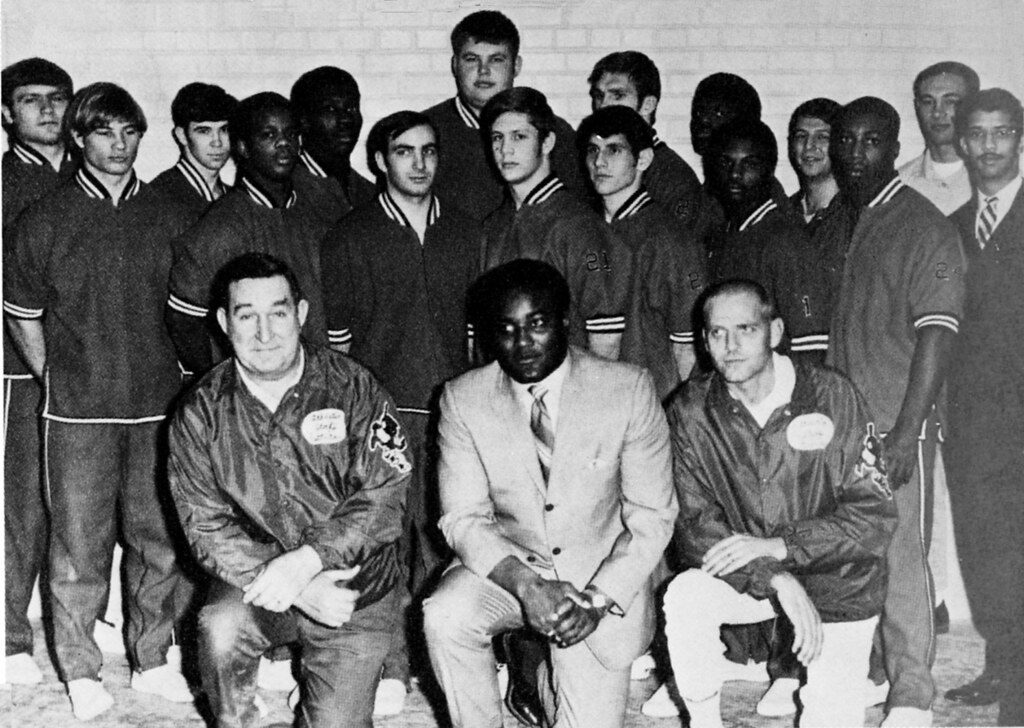

I first met up with Curlee Alexander for the following story, which appeared about eight years ago as part of my series on Omaha Black Sports Legends titled, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. Alexander was a top-flight collegiate wrestler for his hometown University of Nebraska at Omaha but he really made his mark as a high school coach, leading his teams to state championships at two different schools – his alma mater Technical (Tech) High School and North High School. He is inducted in multiple athletic hall of fames. Then, about three years ago I caught up with him again in working on a profile of his younger cousin Houston Alexander, a mixed martial arts fighter Curlee trains. You can find on this blog most every installment from the Out to Win series as well as that profile I did on Houston Alexander. More recently yet Curlee came to mind when I did a piece on the 1970 NAIA championship UNO wrestling team he helped coach as a graduate assistant and that he helped lay the foundation for as a wrestler under coach Don Benning. You’ll find that story and a profile of Benning, who is one of Alexander’s chief mentors, on this blog. The UNO wrestling program made a great impact on the sport locally, regionally, and nationally but sadly the program was eliminated a year and a half ago and now the legacy built by Alexander, Benning, and later Mike Denney and Co. can only found in record books and memories and news files. My story about the end of the program is also featured on this blog.

Alexander the Great’s Wrestling Dynasty – Champion Wrestler and Coach Curlee Alexander on Winning (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Short in stature and sleek of build, Curlee Alexander still manages casting a huge shadow in Nebraska wrestling circles even though the largely retired educator is now a co-head coach. Seven times as head coach he led his prep teams to state championships, six at Omaha North and one at Omaha Tech. Twice, his North squads were state runners-up. Four more times his Vikings finished third. Dozens of his athletes won individual state titles, including three by his son Curlee Alexander Jr., and many had successful college careers on and off the mat.

In the wrestling room, Alexander’s word is law because his athletes know this former collegiate national champion wrestler once made the same sacrifice he asked of them. Following an undistinguished high school wrestling career at Omaha Tech, his persistence in the sport paid off when he blossomed into a four-time All-American for then-Omaha University. UNO wrestling’s rise to prominence under coach Don Benning was rewarded when the team won the 1970 NAIA team title and Alexander took the 115-pound individual title in the process.

Like most ex-wrestlers, Alexander’s keeps in tip-top shape and, even pushing 60, he still demonstrates some of his coaching points on the mat with his own wrestlers — going body to body with guys less than a third his age and often outweighing him. In the old days, he pushed guys to the limit and, in wrestling vernacular, “beat up on ‘em,” to see how they responded. It was all about testing their toughness and their heart. It’s the way he came up.

Proving himself has been the theme of Alexander’s life. He grew up in a north Omaha neighborhood, near the old Hilltop Projects, filled with fine athletes. Being a pint-sized after-thought who “was always trying to catch up” to the other guys in the hood, he searched for a sport he could shine in. “I was small and weak and slow. I had to start from scratch to develop my athletic skills,” he said. “Wrestling was about the only thing I could do and I was really not very good.” To begin with.

He learned the sport from Tech coach Milt Hearn. In classic apprentice fashion, he started at the bottom and worked his way up. “When he got me started wrestling, I was used as a doormat,” Alexander said. “All I was required to do was save the team points by not getting pinned. If I could do that, than I did my job. As a junior, I got beat out by two freshmen. I was always fighting an uphill battle. I could never let up. I could never be comfortable. I knew I had to work hard. I knew I had to work harder than most of ‘em just to be successful.” Despite this less than promising debut, Alexander said he “kept getting after it. I started buying a lot of weight training-body building books and started weight lifting. By the time I got to be a senior I didn’t wrestle anybody that was any stronger than me. I finished second in every tournament I entered my senior year. I never won a championship in high school. The first championship I won was when I reached college.”

Sparking his evolution from designated mop-up guy to legitimate contender was the motivation others gave him. “I had a lot of good role models, one of which was my father. He always preached athletics to us.” Where his father encouraged him, his brother dis’d him. “My brother was a much better athlete than I was, so I was always trying to do things, more or less, to impress him. I’d come home after losing and my brother would make comments like, ‘I knew you weren’t going to win,’ and so I picked up the I’m-going-to-show-you attitude. I was never the athlete he was, but I accomplished a lot more in the athletic arena than he ever dreamed of.”

Then there were the studs he grew up with in the hood, guys like Ron Boone, Dick Davis, Joe Orduna and Phil Wise, all of whom went onto college and pro sports careers. If that wasn’t motivation enough to hurry up and make his own mark, there were the reminders he got from friend and Omaha U. classmate Marlin Briscoe, who was making a name for himself in small college football. “I tried out for the wrestling team and there was a returning wrestler who beat me out. I saw Marlin at the student center and he asked, ‘How’d you do?’ I told him I got beat by this guy and he said, ‘Man, that guy’s no good…he got beat all the time last year.’” And that guy never beat me again. All I needed to hear were little things like that.”

Fast forward a few years later to Alexander’s national semi-final match in Superior, Wis. His opponent had him in a good lock and was preparing to turn him when Alexander recalled something former Tech High teammate, Ralph Crawford, told him about the winning edge. “He told me, with emphasis, ‘Give him nothing,’ and because of that little inspiration I knew I had a little extra to do, and it made a difference in my winning that match and going on to be a national champion.”

There was also the example set by his UNO teammates, Roy and Mel Washington, a pair of brothers who won five individual national titles (three by Roy and two by Mel) between them. “Probably the one I learned the most from, as far as determination, was the late Roy Washington,” who later changed his name to Dahfir Muhammad. He was just a great leader. Phenomenal. I watched him. Everything he did I tried to do and it made all the difference in the world. He knew how to work. He knew what it took. He just refused to get beat. He was real mentally tough,” Alexander said. “If you’re weak-minded, you can forget it.”

Finally, there’s Don Benning, whom Alexander credits for giving him the opportunity and direction to make something of himself. “He’s the reason I have a college degree and was able to go on and teach and coach for 30-odd years. He gave me a chance where I had no other chance,” he said. “He made you believe you could achieve. I wouldn’t have been able to achieve nearly as much success if I hadn’t been under his tutelage. As far as coaching, I basically followed his philosophy. Hard work. Refuse to lose. Being the best on your feet. I built on that foundation.”

Surrounded by superb tacticians, Alexander drew on this rich vein of knowledge, as well as his own from-the-bottom-to-the-top experience as a wrestler, to inform his coaching. “I took a little bit from everybody and applied it. In dealing with kids I tell them I know what it’s like to be weak and not have any athletic ability, and yet go to the top. I teach kids what they need to do in order to improve, to stay dedicated, to be successful and to be champions. What I strive to do as a coach is lead by example. I work out with them to show I’m not afraid to work.”

Much like Benning, whom he coached under as a graduate assistant, Alexander doesn’t try fitting athletes into a box. He lets them develop their own style. “If I’ve got a kid who’s got some decent ability I don’t tell him he’s got to wrestle this way or that way. We try to get what he’s got and improve on it and try to impress upon him to keep working until he understands what it takes to be a champion.”

A young Curlee Alexander in his UNO wrestling singlet, ©UNO Criss Library

Champions. He’s coached numerous team and individual titlists. As satisfying as the team wins are, he said, they “don’t compare to the individual ones. The kids put so much effort into it.” He said a coach must be a master motivator to figure out what makes each individual tick. “All the time, I’m looking for angles to get into a kid’s head to get him to believe,” he said. “What separates a lot of coaches is getting those kids to believe your philosophy is correct. It boils down to being able to communicate and to have kids want to succeed for you and themselves.”

He makes clear he expects nothing less than champions. “I’ve got a lot of guys that have placed at state, but if they didn’t win a state championship, their picture does not go up on the wall in my office. That might be kind of harsh, but it’s reality. That’s what we’re trying to get our kids to strive for and win. Championships are what it’s all about.” He said his favorite moments come from kids who aren’t talented, yet get it done anyway and claim a championship that lasts a lifetime. North High heavyweight Brandon Johnson is an example. “He wasn’t really a good athlete. Overweight. He had to cut down to 275. But he was a hard worker and he had a big heart,” Alexander said. “And, boy, when he won state in 2001, I had tears in my eyes for the first time. I didn’t even cry when my son won, because it was understood he was going to win. But with this guy, it really wasn’t expected. It was just a culmination of all the hard work he gave.”

The hardest part of coaching is seeing “kids do all that hard work and then, when they get right there to the doorstep” of a championship, “they don’t win it.”

The heralded prep coach began as an assistant at Tech, whose wrestling program he took over in the mid’70s. He remained at Tech until it closed in 1984, when he went to North, where he’s remained until retiring from teaching full-time in 2002. The next year he stepped down as head coach to serve as associate head coach and lately he’s added Dean of Students to his duties. As co-head coach, he’s freed himself from all the red-tape to just work with the wrestlers. When his mentor, Don Benning, recently expressed surprise at how much passion Alexander still has for the sport, the former student replied, “I still enjoy it. I enjoy the strategy. I enjoy the competition. I enjoy working with the kids. They keep you young.” He said matching Xs and Os with coaches during a match never gets old. “I really think I’m very good at it and, boy, when I’m successful at it, it’s exhilarating.”

Alexander’s been a pioneer in much the same way Don Benning was at UNO in the ‘60s and Charles Bryant was at Abraham Lincoln High School (Council Bluffs) in the ‘70s. Each man became the first black head coach at their predominantly white schools, where they established wrestling dynasties. In more than 75 years of competition, Alexander is the only black head coach in Nebraska to lead his team to a state wrestling title (and he’s done it at two different schools). Along the way, he built a dynasty at North, which in all the years previous to his arrival had won but a single state wrestling championship. He had six as head coach. Through it all, he’s defied expectations and overturned stereotypes by doing it his way.

Related articles

- Closing Installment from My Series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From My Series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Can Houston Alexander Break Gilbert Yvel? (mmaggregate.wordpress.com)

Closing installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An appreciation of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

Here is the closing installment from my 2004-2005 series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. In this and in the recently posted opening installment I try laying out the scope of achievements that distinguishes this group of athletes, the way that sports provided advancement opportunities for these individuals that may otherwise have eluded them, and the close-knit cultural and community bonds that enveloped the neighborhoods they grew up in. It was a pleasure doing the series and getting to meet legends Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers, et cetera. I learned a lot working on the project, mostly an appreciation for these athletes’ individual and collective achievements. You’ll find most every installment from the series on this blog, including profiles of the athletes and coaches I interviewed for the project. The remaining installments not posted yet soon will be.

Closing installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness,

An Appreciation of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Any consideration of Omaha’s inner city athletic renaissance from the 1950s through the 1970s must address how so many accomplished sports figures, including some genuine legends, sprang from such a small place over so short a span of time and why seemingly fewer premier athletes come out of the hood today. As with African-American urban centers elsewhere, Omaha’s inner city core saw black athletes come to the fore, like other minority groups did before them, in using sports as an outlet for self-expression and as a gateway to more opportunity.

As part of an ongoing OWR series exploring Omaha’s Black Sports Legends, this installment looks at the conditions and attitudes that once gave rise to a singular culture of athletic achievement here that is less prevalent in the current feel-good, anything-goes environment of plenty and World Wide Web connectivity.

The legends and fellow ex-jocks interviewed for this series mostly agree on the reasons why smaller numbers of youths these days possess the right stuff. It’s not so much a lack of athletic ability, observers say, but a matter of fewer kids willing to pay the price in an age when sports is not the only option for advancement. The contention is that, on average, kids are neither prepared nor inclined to make the commitment and sacrifice necessary to realize, much less pursue, their athletic potential when less demanding avenues to success abound.

“Kids today are changed — their attitudes about authority and everything else,” says Major League Baseball Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson, an Omaha Tech High grad who grew up in the late’40s-early ‘50s under the stern but steady hand of coaches like his older brother, Josh. “They’re like, I’m not going to let somebody tell me what to do, where we had no problem with that in our day.”

Gibson says coaches like Josh, a bona fide legend on the north side, used to be viewed as an extension of the family, serving, “first of all,” as “a father figure,” or as Clarence Mercer, a top Tech swimmer, puts it, as “a big brother,” providing discipline and direction to that era’s at-risk kids, many from broken homes.

Josh Gibson, along with other strong blacks working as coaches, physical education instructors and youth recreation directors in that era, including Marty Thomas, John Butler, Alice Wilson and Bob Rose, are recalled as superb leaders and builders of young people. All had a hand in shaping Omaha’s sports legends of the hood, but perhaps none more so than Gibson, who, from the 1940s until the 1960s, coached touring baseball-basketball teams out of the North Omaha Y. “Josh was instrumental in training most of these guys. He was into children, and into developing children. He carried a lot of respect. If you cursed or if you didn’t do what he wanted you to do or you didn’t make yourself a better person, than you couldn’t play for him,” says John Nared, a late ‘50s-early ’60s Central High-NU hoops star who played under Gibson on the High Y Monarchs and High Y Travelers. “He didn’t want you running around doing what bad kids did. When you came to the YMCA, you were darn near a model child because Josh knew your mother and father and he kept his finger on the pulse. When you got in trouble at the Y, you got in trouble at home.”

Old-timers note a sea change in the way youths are handled today, especially the lack of discipline that parents and coaches seem unwilling or unable to instill in kids. “You see young girls walking around with their stuff hanging out and boys bagging it with their pants around their ankles. In our time, there were certain things you had to do and it was enforced from your family right on down,” says Milton Moore, a track man at Central in the late ‘50s.

The biggest difference between then and now, says former three-sport Tech star and longtime North Omaha Boys Club coach Lonnie McIntosh, is the disconnected, permissive way youths grow up. Where, in the past, he says, kids could count on a parent or aunt or neighbor always being home, youths today are often on their own, in a latchkey home, isolated in their own little worlds of self-indulgence.

“What’s missing is a sense of family. People living on the same street may not even know each other. Parents may not know who their kids are running with. In our day, we all knew each other. We were a family. We would walk to school together. Although we competed hard against one another, we all pulled for one another. Our parents knew where we were,” McIntosh says.

“There were no discipline problems with young people in those days,” Mercer adds somewhat apocryphally.

Former Central athlete Jim Morrison says there isn’t the cohesion of the past. “The near north side was a community then. The word community means people are of one mind and one accord and they commune together.” “There’s no such thing as a black community anymore,” adds John Nared. “The black community is spread out. Kids are everywhere. Economics plays a part in this. A lot of mothers don’t have husbands and can’t afford to buy their kids the athletic shoes to play hoops or to send their kids to basketball camps. Some of the kids are selling drugs. They don’t want a future. We wanted to make something out of our lives because we didn’t want to disappoint our parents.”

The close communion of days gone by, says Nared, played out in many ways. Young blacks were encouraged to stay on track by an extended, informal support system operating in the hood. “The near north side was a very small community then…so small that everybody knew each other.” In what was the epitome of the it-takes-a-village-to-raise-a-child concept, he says the hood was a community within a community where everybody looked out for everybody else and where, decades before the Million Man March, strong black men took a hand in steering young black males. He fondly recalls a gallery of mentors along North 24th Street.

“Oh, we had a bunch of role models. John Butler, who ran the YMCA. Josh Gibson. Bob Gibson. Bob Boozer. Curtis Evans, who ran the Tuxedo Pool Hall. Hardy “Beans” Meeks, who ran the shoe shine parlor. Mr. (Marcus “Mac”) McGee and Mr. (James) Bailey who ran the Tuxedo Barbershop. All of these guys had influence in my life. All of ‘em. And it wasn’t just about sports. It was about developing me. Mr. Meeks gave a lot of us guys jobs. In the morning, when I’d come around the corner to go to school, these gentlemen would holler out the door, ‘You better go up there and learn something today.’ or ‘When you get done with school, come see me.’

“Let me give you an example. Curtis Evans, who ran the pool hall, would tell me to come by after school. ‘So, I’d…come by, and he’d have a pair of shoes to go to the shoe shine parlor and some shirts to go to the laundry, and he’d give me two dollars. Mr. Bailey used to give me free haircuts…just to talk. ‘How ya doin’ in school? You got some money in your pocket?’ I didn’t realize what they were doing until I got older. They were keeping me out of trouble. Giving me some lunch money so I could go to school and make something of myself. It was about developing young men. They took the time.”

Beyond shopkeepers, wise counsel came from Charles Washington, a reporter-activist with a big heart, and Bobby Fromkin, a flashy lawyer with a taste for the high life. Each sports buff befriended many athletes. Washington opened his humble home, thin wallet and expansive mind to everyone from Ron Boone to Johnny Rodgers, who says he “learned a lot from him about helping the community.” In hanging with Fromkin, Rodgers says he picked-up his sense of “style” and “class.”

Super athletes like Nared got special attention from these wise men who, following the African-American tradition of — “each one, to teach one” — recognized that if these young pups got good grades their athletic talent could take them far — maybe to college. In this way, sports held the promise of rich rewards. “The reason why most blacks in that era played sports is that in school then the counselors talked about what jobs were available for you and they were saying, ‘You’ll be a janitor,’ or something like that. There weren’t too many job opportunities for blacks. And so you started thinking about playing sports as a way to get to college and get a better job,” Nared says.

Growing up at a time when blacks were denied equal rights and afforded few chances, Bob Gibson and his crew saw athletics as a means to an end. “Oh, yeah, because otherwise you didn’t really have a lot to look forward to after you got out of school,” he says. “The only black people you knew of that went anywhere were athletes like Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson or entertainers.” Bob had to look no further than his older brother, Josh, to see how doors were closed to minorities. The holder of a master’s degree in education as well as a sterling reputation as a coach, Josh could still not get on with the Omaha Public Schools as a high school teacher-coach due to prevailing hiring policies then.

“Back in the ‘50s and early ‘60s the racial climate was such we had nothing else to really look forward to except to excel as black athletes,” says Marlin Briscoe, the Omaha South High School grad who made small college All-America at then-Omaha University and went on to be the NFL’s first black quarterback. “We were told, ‘You can’t do anything with your life other than work in the packing house.’ We grew up seeing on TV black people getting hosed down and clubbed and bitten by dogs and not being able to go to school. So, sports became a way to better ourselves and hopefully bypass the packing house and go to college.”

Besides, Nared, says, it wasn’t like there was much else for black youths to do. “Back when we were coming up we didn’t have computers, we didn’t have this, we didn’t have that. The only joy we could have was beating somebody’s ass in sports. One basketball would entertain 10 people. One football would entertain 22 people. It was very competitive, too. In the neighborhood, everybody had talent. We played every day, too. So, you honed in on your talents when you did it every day. That’s why we produced great athletes.”

With the advent of so many more activities and advantages, Gibson says contemporary blacks inhabit a far richer playing ground than he and his buddies ever had, leaving sports only one of many options. “In our time, if you wanted to get ahead and to get away from the ghetto or the projects, you were going to be an athlete, but I don’t know if that’s been the same since then. I think kids’ interests are other places now. There’s all kinds of other stuff to think about and there’s all kinds of other problems they have that we never had. They can do a lot of things that we couldn’t do back then or didn’t even think of doing.”

Milton Moore adds, “It used to be you couldn’t be everything you were, but you could be a baseball player or you could be a football player. Now, you can be anything you want to be. Kids have more opportunities, along with distractions.”

Ron Boone, an Omaha Tech grad who went to become the iron man of pro hoops by playing in all 1,041 games of his combined 13-year ABA-NBA career, finds irony in the fact that with the proliferation of strength training programs and basketball camps “the opportunities to become very good players are better now than they were for us back then,” yet there are fewer guys today who can “flat out play.” He says this seeming contradiction may be explained by less intense competition now than what he experienced back in the day, when everyone with an ounce of game wanted to show their stuff and use it as a steppingstone.

If not for the athletic scholarships they received, many black sports stars of the past would simply not have gone on to college because they were too poor to even try. In the case of Bob Gibson, his talent on the diamond and on the basketball court landed him at Creighton University, where Josh did his graduate work.

By the time Briscoe and company came along in the early ‘60s, they made role models of figures like Gibson and fellow Tech hoops star Bob Boozer, who parlayed their athletic talent into college educations and pro sports careers. “When Boozer went to Kansas State and Gibson to Creighton, that next generation — my generation — started thinking, If I can get good enough…I can get a scholarship to college so I can take care of my mom. That’s the way all of us thought, and it just so happened some of us had the ability to go to the next level.”

Young athletes of the inner city still use sports as an entry to college. The talent pool may or may not be what it was in urban Omaha’s heyday but, if not, than it’s likely because many kids have more than just sports to latch onto now, not because they can’t play. At inner city schools, blacks continue to make up a disproportionately high percentage of the starters in the two major team sports — football and basketball. The one major team sport that’s seen a huge drop-off in participation by blacks is baseball, a near extinct sport in urban America the past few decades due to the high cost of equipment, the lack of playing fields and the perception of the game as a slow, uncool, old-fashioned, tradition-bound bore.

Carl Wright, a football-track athlete at Tech in the ‘50s and a veteran youth coach with the Boys Club and North High, sees good and bad in the kids he still works with today. “There’s a big change in these kids now. I’ll tell a kid, ‘Take a lap,’ and he’ll go, ‘I don’t want to take no lap,’ and he’ll go home and not look back. I’ve seen kids with talent that can never get to practice on time, so I kick them off the team and it doesn’t mean anything to them. They’ve got so much talent, but they don’t exploit it. They don’t use it, and it doesn’t seem to bother them.”

On the other hand, he says, most kids still respond to discipline when it’s applied. “I know one thing, you can tell a kid, no, and he’ll respect you. You just tell him that word, when everybody else is telling him, yes, and they get to feeling, Well, he cares about me, and they start falling into place. There’s really some good kids out there, but they just need guidance. Tough love.”

Tough love. That was the old-school way. A strict training regimen, a heavy dose of fundamentals, a my-way-or-the-highway credo and a close-knit community looking out for kids’ best interests. It worked, too. It still works today, only kids now have more than sports to use as their avenue to success.

Related articles

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Hoops Legend John C. Johnson: Fierce Determination Tested by Repeated Run-Ins with the Law (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- One Peach of a Pitcher: Peaches James Leaves Enduring Legacy in the Circle as a Nebraska Softball Legend (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Great Migration Comes Home: Deep South Exiles Living in Omaha Participated in the Movement Author Isabel Wilkerson Writes About in Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Opening installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

Here is the opening installment from my 2004-2005 series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. Look for the closing installment in a separate post. In these two pieces I try laying out the scope of achievements that distinguishes this group of athletes, the way that sports provided advancement opportunities for these individuals that may otherwise have eluded them, and the close-knit cultural and community bonds that enveloped the neighborhoods they grew up in. It was a pleasure doing the series and getting to meet legends Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers, et cetera. I learned a lot working on the project, mostly an appreciation for these athletes’ individual and collective achievements. You’ll find most every installment from the series on this blog, including profiles of the athletes and coaches I interviewed for the project. The remaining installments not posted yet soon will be.

Opening installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness,

An exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Omaha’s African American community has produced a heritage rich in achievement across many fields, but none more dramatic than in sports, Despite a comparatively small populace, black Omaha rightly claims a legacy of athletic excellence in the form of legends who’ve achieved greatness at many levels, in a variety of sports, over many eras.

These athletes aren’t simply neighborhood or college legends – their legacies loom large. Each is a compelling story in the grand tale of Omaha’s inner city, both north and south. The list includes: Bob Gibson, a major league baseball Hall of Famer. Bob Boozer, a member of Olympic gold medal and NBA championship teams. NFL Hall of Famer Gale Sayers. Marlin Briscoe, the NFL’s first black quarterback. Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers. Pro hoops “iron man” Ron Boone. Champion wrestling coach Don Benning

“Some phenomenal athletic accomplishments have come out of here, and no one’s ever really tied it all together. It’s a huge story. Not only did these athletes come out of here and play, they lasted a long time and they made significant contributions to a diversity of college and professional sports,” said Briscoe, a Southside product. “I mean, per capita, there’s probably never been this many quality athletes to come out of one neighborhood.”

An astounding concentration of athletic prowess emerged in a few square miles roughly bounded north to south, from Ames Avenue to Lake Street, and east to west from about 16th to 36th. Across town, in south Omaha, a smaller but no less distinguished group came of age.

“You just had a wealth of talent then,” said Lonnie McIntosh, a teammate of Gibson and Boozer at Tech High.

Many inner city athletes resided in public housing projects. Before school desegregation dispersed students citywide, blacks attended one of four public high schools – North, Tech, Central or South. It was a small world.

During a Golden Era from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s, all manner of brilliant talents, including future all-time greats, butted heads and rubbed shoulders on the same playing fields and courts of their youth, pushing each other to new heights. It was a time when youths competed in several sports instead of specializing in one.

“In those days, everybody did everything,” said McIntosh, who participated in football, basketball and track.

Many were friends, schoolmates and neighbors, often living within a few doors or blocks of each other. It was an insular, intense, tight-knit athletic community that formed a year-round training camp, proving ground and mutual admiration society all rolled into one.

“In the inner city, we basically marveled at each other’s abilities. There were a lot of great ballplayers. All the inner city athletes were always playing ball, all day long and all night long,” said Boozer, the best player not in the college hoops hall of fame. “Man, that was a breeding ground. We encouraged each other and rooted for each other. Some of the older athletes worked with young guys like me and showed us different techniques. It was all about making us better ballplayers.”

NFL legend Gale Sayers said, “No doubt about it, we fed off one another. We saw other people doing well and we wanted to do just as well.”

The older legends inspired legends-to-be like Briscoe.

“We’d hear great stories about these guys and their athletic abilities and as young players we wanted to step up to that level,” he said “They were older and successful, and as little kids we looked up to those guys and wanted to emulate them and be a part of the tradition and the reputation that goes with it.”

The impact of the older athletes on the youngsters was considerable.