If war is hell, then where does heaven or spirituality come into the picture during armed conflict? The question is apt when considering the career of retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel John Nagl, who squared his strong faith with his extensive combat and military strategy experience while becoming the U.S. Army’s counterinsurgency guru. The Omaha native is a graduate of his hometown’s Creighton Prepatory School , where the Jesuit education he received gave him values and philosiphies that have guided him through war and peace. Read my cover story profile of Nagl that will be appearing in the new issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com). In it, he reflects on his roles as a man for others, a patriot, a military strategist, a combat leader, and a scholar and educator.

John Nagl

Retired warrior, lifetime scholar John Nagl vecame U.S. Army counterinsurgency guru

by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in The Reader (www.the reader.com)

Two years since the U.S. pulled troops out of Iraq Americans still slog it out in Afghanistan — a full 12 years since its start. The dual wars for which so many paid a heavy price will forever be analyzed by the likes of Omaha native John Nagl, managing editor of the official U.S. Army-Marine Corps Counter insurgency Manual.

The retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel was not only a military wonk under General David Petraeus but a warrior for whom the wars the U.S., waged in the wake of 9/11 were both object lessons and hard realities.

Millions of people have been touched directly or indirectly by the conflicts. Thousands of combatants and hundreds of thousands of noncombatants have died, many more have suffered physical damage and emotional trauma. The material costs run into the trillions. The intangible costs are incalculable.

Nagl is well aware that America and the world is sharply divided on the question of whether the wars were just or unjust, necessary or unnecessary, moral or immoral. Weighing such questions is nothing new for Nagl, who is steeped in Jesuit values gleaned from his education at Omaha Creighton Prep. He was a Golden Boy who graduated West Point, became a Rhodes Scholar and studied at Oxford. He served in both the first Gulf War, where he led a tank platoon, and the Iraqi Freedom campaign, where he led armor regiments.

Like some Templar Knight on a crusade this warrior-scholar has been imbued with a sense of nationalistic duty to defend his country from all enemies and with a faithful devotion to do God’s will as he sees it.

Nagl found no contradiction serving his fellow man and doing combat. He’s comfortable too squaring his humanist ideals and Christian faith with having influenced the Army’s adoption of controversial counterinsurgency (COIN) techniques.

“The sense of being a man for others, your life being a gift and it being your responsibility to invest that gift wisely for the greater glory of God, for the furthermost of his purposes here on Earth, that’s part of what certainly drove me to West Point and to a career in the military,” says Nagl, who was near the top of his 1988 West Point class.

Long on a rising star track in the military industrial complex – he received the George C. Marshall Award as the top graduate of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College – he seemingly went “rogue” when he advanced the use of COIN strategies in his master’s dissertation. He borrowed his work’s title, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife, from a T.S. Lawrence observation about the difficulties of responding to insurgencies.

“I read that and I thought, man, that captures it, I now understand how hard this kind of war is. And then I went to Al Anbar (Iraq) and tried it and it was a whole lot harder than I thought it was.”

The impetus for his infatuation with COIN was the U.S. military’s dominance of Iraqi forces in the Gulf War and his conviction that future enemies would avoid direct confrontations.

“I became convinced the military might of the United States which had cut through the Iraqi army, the fourth largest in the world, like a hot knife through butter, was so overwhelming that future enemies wouldn’t confront us conventionally in force on force, tank on tank battles, they’d fight us as irregular warriors, as insurgents and terrorists.”

Nagl was a voice in the wilderness, due in no small part to the fact that “after Vietnam,” he says, “we consciously turned away from counterinsurgency as a nation and as an army, and pretty much literally burned the books and decided we weren’t going to do that anymore.” Yet there was Nagl calling on the ghosts of wars’ past.

“I was very lonely in the mid-1990s doing that. Everybody else was studying the revolution in military affairs and Shock and Awe and the idea that the U.S. military would triumph rapidly using precision weaponry. I was convinced that wasn’t the case.

“It was a discouraging time. Nobody was interested in counterinsurgency until after the attacks of September 11th (2001), when suddenly everybody was interested in counterinsurgency.”

Nagl’s dissertation found a publisher and his advocacy of COIN that before fell on deaf ears got the attention of a well-placed general, David Petraeus, who embraced Nagl’s writings. Petraeus, who’d been a professor of Nagl’s at West Point, eventually became the lead commander prosecuting the war in Iraq, where he changed the rules of engagement, partly through the use of COIN tactics in the field.

“It was the first time I felt I’d found someone in a position of authority who really understood the need. He was the right guy in the right place at the right times,” Nagl says of Petraeus.

Nagl, who was twice posted to the 24th Infantry Division at Fort Riley, Kansas, contributed to a new counterinsurgency field manual and tested out his theories in combat.

“I was sent to Iraq to do the research and to conduct counterinsurgency in Al Anbar in 2003 and 2004. We were rediscovering lessons consigned to very dusty bookshelves and I was just the guy who’d blown the dust off of those books. And then having read the books I tried to implement it in a particularly challenging place and quite frankly failed pretty miserably, so that when I came back from Al Anbar I wrote a short piece about how I thought I’d done, calling it, Spilling Soup on Myself. That became the preface to the paperback version of my dissertation.

“One of the criticisms I make of myself in that preface is that there’s sort of a blithe sense in my book that once you understand the principles it’s comparatively easy to apply them and, boom, everything will work out. Yeah not so much, not so much…Conventional combat is hard enough but counterinsurgency is conventional combat cubed. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever tried to do in my life.”

During Nagl’s 2003-2004 deployment he became an Army celebrity.

“A journalist named Peter Maas embedded with my unit wrote a very substantial New York Times Magazine piece called ‘Professor Nagl’s War’ that popularized some of my ideas to a pretty big audience.”

He says his profile was also enhanced “being at the center of the storm” as military assistant for then deputy secretary of defense Paul Wolfowitz in the Pentagon “as the Iraq war was going rapidly downhill in 2005 and 2006.”

As COIN became in vogue as a new approach his reputation as a counterinsurgency guru got him invited on the Charlie Rose Show and The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. Nagl’s a natural for the media to glom onto. He’s handsome, articulate, passionate. He can banter with the best. He cuts a dashing figure in or out of uniform and embodies the whole “be all you can be” slogan with aplomb and panache.

On Charlie Rose he took part in a roundtable discussion about Vietnam, Iraq and counterinsurgency that he says “was intellectually stimulating and engaging and I hope helpful to the American public.”

“The Daily Show was a different experience entirely,” he notes. “The field manual had been published by the University of Chicago. I was back at Fort Riley, Kansas and was literally running a machine gun range when I got a phone call from someone purporting to be from the show asking if I could come on later that week. I didn’t believe it really was them. Well, it really was, and I said yes. Then I had to convince the Army to let me go. The Army actually cut orders, it was official business, so I wore my uniform.”

Nagl’s sure what proceeded was “the funniest discussion Jon Stewart has ever had on camera about an army field manual.” This hawk’s appearance on a show synonymous with cool, anti-establishment satire, he says, makes his “credibility go way up” when talking to student audiences. “They don’t care I’ve been shot at in a couple of wars, but trading words with Jon Stewart, that is an honor right there.”

COIN strategy came under sharp criticism within and outside senior military command beginning in 2008, He retired from the Army that same year.

In his immediate post-Army life he served as president of the Center for a New American Security from 2009 to 2012. This summer he assumed the headmaster role at the exclusive all-boys Haverford School in Penn., where his son Jack started the 6th grade.

After his Army retirement there was speculation he’d left because he found his path for advancement blocked due to his close association with counterinsurgency. He denies it.

“My retirement had nothing to do with having been passed over. I hadn’t been. If I had been, I wouldn’t have been positioned to continue rising up the ranks,” he says.

He adds that his retirement also had nothing to do “with counterinsurgency strategy falling out of favor,” adding, “It hadn’t when my retirement was announced in January 2008 or when I retired in October 2008.” In fact, he argues, counterinsurgency “was still ascendant in 2009 when the President twice increased force levels in Afghanistan to conduct COIN.”

No, it turns out Nagl walked away from the service he loves for, well, love. He and his wife Susi Varga, whom he met at Oxford, have a young son together and she wasn’t so keen on being an Army bride.

In an email, he wrote, “The decision was a personal one that was perhaps inevitable when I fell in love with a Hungarian Oxford student of literature and the arts and brought her on repeated tours to Kansas. The Army life had relatively little appeal for her and never really let her find her footing and spread her wings. I’m hoping that our new life together at the Haverford School will provide soil in which she flowers.”

That doesn’t mean he’s made a complete break with the military world, which after all was all he knew for more than two decades.

“I miss the Army every day. I loved being in the Army, being part of an organization that has global reach, that is composed of talented, dedicated young professionals, that boasts such a proud history, that makes history. I like to think that I’m still helping my army and my nation as a civilian – writing, educating, serving on the Defense Policy Board and the Reserve Forces Policy Board. But I still miss strapping on my tanker boots every morning.”

During his time in the military he did his best to both live the Jesuit motto “for the greater glory of God” and to train for and wage war. He says the two things never posed a moral conflict for him.

“I never saw any conflict between being a product of a Jesuit education and serving in the U.S. military. The Jesuits taught me the difference between jus ad bellum and jus in bello; the first, whether a war is fought for a just cause, is the business of politicians. How that war is fought, or jus in bello, is the business of soldiers. The first Gulf War, Operation Desert Storm, was clearly a just and necessary war, fought to free a conquered people and restore international order, and it was fought in a just manner.

“My second war, Iraqi Freedom, I did not then and do not now believe was necessary. However, it was fought according to the laws of war on our side, and we punished violations of those laws that did occur. I also worked to help the Army fight it more wisely and cause less harm to the Iraqi people through the writing of the U.S. Army-Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual. The Jesuits must have thought that on balance, I worked Ad majorem Dei gloriam (For the greater glory of God) as they named me Alumnus of the Year for 2012 and included my rank on the award.”

Though the haze of war is full of tragedies and atrocities, Nagl holds to the classical warrior’s view that duty to country and God are the same. This fervent patriot and devout Christian swears allegiance to both.

“Military service is completely compatible with the values I learned at Prep. Some of the finest men for others I have ever known were those who laid down their lives for their friends that we could all live in peace and freedom. We must build a country that is worthy of their sacrifice.”

As a military academy product and teacher (he taught at West Point and the Strategic Studies Institute at the United States Army War College), Nagl knows Army history and thus takes a long view of things when it comes to COIN.

“Counterinsurgency is always going to be messy and slow, but if you’re trying to defeat an insurgency, it’s the least bad option. I’ve always said counterinsurgency is hard, that it’s not guaranteed to work by any means. What I always ask the skeptics is, ‘What do you recommend instead?’

“And the fact is with the American withdrawal from Iraq, the pending continuing drawdown in Afghanistan, the United States has decided not to engage itself in what we call big footprints –, tens or hundreds of thousands of American troops counterinsurgency-camping. But we’re still engaged in supporting insurgencies in places like Syria and supporting countries fighting against insurgencies not just in Afghanistan and Pakistan but also in the Philippines, Somalia, Yemen, the list goes on.

“So it isn’t that insurgency and counterinsurgency have gone away but America’s not convinced you get what you pay for, and that I think is a fair question.”

In many ways, the beat goes on in the places where Nagl and his fellow soldiers saw action.

“Big footprint counterinsurgency continues in Iraq but it’s Iraqi troops rather than American troops who are conducting that campaign. We were able to build up the Iraqi forces and tamp down the fires of sectarian conflict sufficiently to pass that one off to Iraq and say, ‘Good luck guys,. over to you.’

“The campaign in Afghanistan is more complicated. Afghanistan has never been as important a country for U.S. interests as Iraq was

and the real epicenter of this struggle is not Afghanistan at all, but Pakistan, which is the current home of Al Qaeda central, what remains of it, and I believe still today is the most dangerous country in the world for the United States. The biggest global threat we face comes from Pakistan.”

When it comes to military affairs these days Nagl is an interested and well-informed bystander. As closely as he still observes what’s happening in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere, he’s more concerned today with leading a school and preparing its students than with war analysis and strategy. At Haverford he feels he’s found a real home.

“In a lot of ways it’s a secular version of Creighton Prep. It’s a K-12 with about a thousand boys, with a great history. It started in 1884, a hundred years before I graduated from Prep. When I visited the school there were two things engraved in the fabric of the school that really sang to me. One was over the gymnasium and it said a sound mind and a sound body in Latin and those are principles I believe in pretty strongly.”

He says engraved just over the entrance of the upper school building is Teddy Roosevelt’s Man in the Arena quotation, whose credo of service and action is one that Nagl’s lived by.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

“To fight the world’s fight, I believe in that responsibility,” says Nagl. “The Jesuits taught me that, my mom and dad taught me that. So it really seemed like this was a place after my own heart.”

0.000000

0.000000

Share this: Leo Adam Biga's Blog

Forty-plus interviews were captured nationwide, mostly with veterans ranging across different military branches and racial-ethnic backgrounds. Some saw combat. Some didn’t. Civilians were also interviewed about their contributions and sacrifices, including women who lost spouses in the war. Even stories of conscientious objectors were cultivated. Subjects shared stories not only of the war, but of surviving the Great Depression that preceded World War II.

Forty-plus interviews were captured nationwide, mostly with veterans ranging across different military branches and racial-ethnic backgrounds. Some saw combat. Some didn’t. Civilians were also interviewed about their contributions and sacrifices, including women who lost spouses in the war. Even stories of conscientious objectors were cultivated. Subjects shared stories not only of the war, but of surviving the Great Depression that preceded World War II.

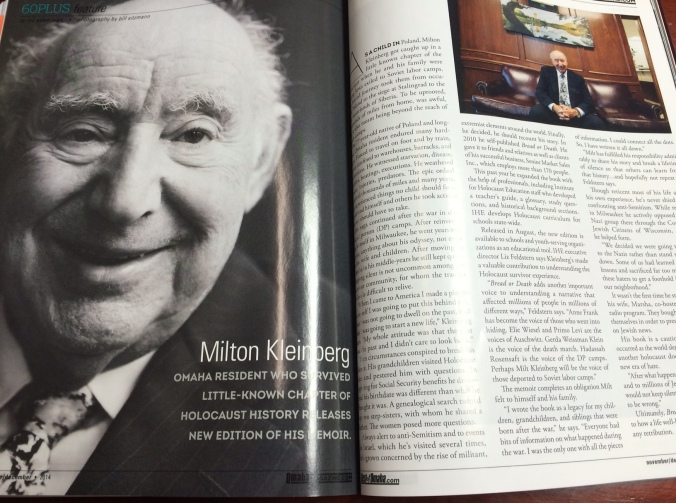

Milton Kleinberg

Milton Kleinberg