Another of my Holocaust stories is featured here. Joe Boin tells his story of defiance and survival.

A not-so-average Joe tells his Holocaust story of survival

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Jewish Press

It’s not as if Joe Boin hadn’t spoken about his Holocaust survivor tale before. He shared his story for the Shoah Visual History Project. He’s told it to school groups. He helped form Nebraska Survivors of the Holocaust to raise awareness and to commission public memorials as reminders of what happened.

But until now the Berlin, Germany native never laid out his story for publication. The time seemed right. The 87-year-old widower resides at the Rose Blumkin Home, where he scoots around in his motorized wheelchair with aplomb, American and Go Big Red flags affixed to the back. The amiable man makes friends easily and lives a credo of looking ahead, not back, but the searing memories never dim. Alone with his thoughts, his odyssey is always near.

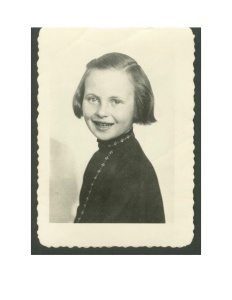

His wife Lilly, a fellow survivor he met and married after the war, passed away 14 years ago. A Vienna, Austria native, she told her survivor tale in her 1989 book, My Story. Everyone close to her died in the Shoah.

Remarkably, Joe’s entire immediate family made it out alive. His parents are long gone and his only two siblings live in Israel. Palestine is where Joe, Lilly, his sisters and eventually his folks migrated after the war. Joe and Lilly’s two children, Heni Alice and Gustav Daniel, were born and raised in Israel. Joe suffered wounds in the fight for Israel’s independence. The couple’s children preceded them to America and Joe and Lilly followed in 1966.

After hopskotching the country to be near their children, Joe and Lilly made it to Nebraska in the late-1970s, residing first in Lincoln before settling in Omaha.

Today, Joe lives for his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He sees them when he can but they all live out of state. He’s spending Hanukkah and New Year in Phoenix with his daughter and her family.

Joe insists his story is nothing special. “I’m not too interesting,” he says through his thick accent. “I’m not important.” But Joe knows better. He knows that while every survivor story shares certain commonalities, each is its own wonder, even miracle, of fortitude and fate. He knows, too, it’s his obligation to bear witness.

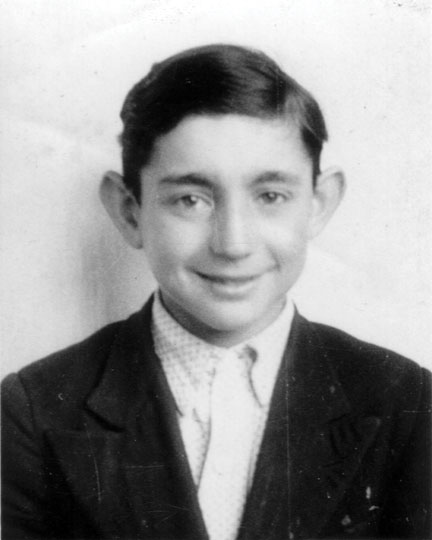

Born Joachim Boin, he was the only son of Arthur and Bianca Boin, an educated Orthodox Jewish couple whose roots were in Germany and Poland, respectively. Joe’s father was a World War I veteran who fought in the German Army. He had his own accounting firm. Joe’s younger sisters, Ruth and Gisela, soon followed.

The family lived in a mixed district of Berlin where Jews and Christians lived and did business together. Next door was a Christian family, the Kruegers, who were old friends. They took an active hand in helping the Boins once the Nazi’s anti-Jewish laws took effect. They even ended up hiding Gisela during the war.

Before the rein of terror, Joe’s early childhood was idyllic. “It didn’t last long but it gave me a taste of what life could be or can be,” he said. “I had dreams but it became impossible for me to even follow them after Hitler came — that all went.”

Growing up in Berlin, Joe witnessed the fascist fervor in its huge rallies and parades that kindled the worst kind of nationalism. The mass public displays included virulent anti-Semetic screeds, all meant to sway the Aryan citizenry, to inflame hatred, to intimidate Jews and other supposed enemies of the state. The Nazi regime tapped the fears of a shaken people by offering security and scapegoats.

“Like everywhere in the world Germany was in a very deep depression, people were out of work and they had big families,” noted Joe, “and so Hitler came and said, ‘Well, if you elect me as your leader I will put bread on your table and I will make sure you have enough money to pay your bills and rent.’ Of course, everybody went for it.”

To the Christian majority Hitler appealed to widespread prejudice in blaming the Jews for Germany’s decline since World War I. For most Jews, the rhetoric and restrictions aimed at them seemed nothing they hadn’t seen or heard before.

“In the very beginning when he was elected he organized the political police and then when people found out what really was going to happen it was too late, they couldn’t do much about it,” said Joe.

A strapping, athletic young man, Joe competed as an elite Maccabi club tennis player, boxer and gymnast, yet Jews like him were ostracized from German national teams and games by the Nazi regime’s racial policies. This exclusion was a bitter pill to swallow for Jewish athletes when Berlin hosted the 1936 Olympics.

“It was pretty painful, I’ll tell you that.”

Amid unprecedented propaganda and pageantry the Nazis attempted to gloss over their campaign of hate against Jews and while some observers saw through the facade most of the world did not. As far back as the Berlin Olympics, Joe’s family was warned of the impending danger facing them.

“In 1936 my mother’s brother, who lived in Berlin, too, came to my dad and said, ‘Arthur, now is the time to leave this country.’ My dad looked at him and said, ‘I was in World War I, I pay my taxes, I have a legitimate business, why should I leave?’ If anybody had any idea what was going to happen, they would have left,” said Joe, but the Boins like most people could not conceive that what seemed another pogrom would become the systematic genocide known as The Final Solution.

Until the fall of 1938 things were tolerable. Jews couldn’t go where and when they pleased as easily as they once could, owing to growing restrictions on their movements and activities, but they didn’t fear for their safety. Clearly, though, life was far from normal and things were getting more tense. Roving gangs of Nazi Brown Shirts were becoming a menace and the mere fact of being a Jew, identified by a Yellow Star, made you a target of these thugs.

The Kruegers, the Christian family who lived next door to the Boins, became a lifeline. “Our neighbors were very nice people and they supplied us with some food and so on, sometimes without taking payment, so that we could live a little,” said Joe.

When he was 15 he and his family moved to a town, Cottbus, where Joe’s father felt they would be more insulated from the Nazi grip. They did find there some kind Christians who lent aid just as the Kruegers had.

“Like everywhere else there were wonderful people that were kind to Jews, that tried to help,” said Joe.

But there ultimately was no escaping the threat. Things took a turn for the worse on Kristallnacht, Nov. 9, 1938. Nazi goons came to the Boin home to take Joe and his father away to the town square where other Jewish residents had been rounded up and their homes and businesses vandalized.

“They took us to a marketplace where they had us surrounded by Nazis and by private citizens and they put dogs on one side and they gave us a spoon and we had to pick up the crap. We got beaten pretty bad. A lot of people got killed there, too. They put bodies in the synagogue and afterwards they burned it.”

For Joe, the nightmarish incident marked the end of his boyhood innocence and the start of a cruel new reality based on instinct, chance and survival.

“My life as a child (ended). I had two years of high school before Hitler kicked us out.” From then on out, life was a harrowing affair. “We were treated like animals, not as human beings, we had to walk on the street, we couldn’t walk on the sidewalks, we couldn’t go into certain stores.”

More and more, Jews found themselves targeted, isolated, marginalized. Then, in 1939, the year Germany invaded Poland and Czechoslovakia and instigated World War II, the family was forcibly split up. A band of Nazis came to the Boin home, this time demanding only Joe come with them. He described what happened:

“At midnight they knocked on our door, shouting, ‘We want your boy Joachim.’ I came to the door and asked, ‘What do you want?’ ‘We have come for you,’ they said, and they grabbed me and hit me and put me on a truck. ‘Where are we going; do I have to take something?’ ‘No, where we’re going you don’t need nothing.’”

The ominous reply presaged the unfolding horror of the next six years, a black time when he and his family were separated from everything they knew, including each other, as each endured his or her own survival odyssey. Joe, his father, his mother and his sister Ruth all ended up in either labor or death camps.

Only his baby sister Gisela was spared. She was hidden by the Kruegers in the Christian family’s Berlin home, where for three-and-a-half years she passed a secreted-away life that if discovered would have meant certain death for her and her benefactors.

“My dad always said to them (the Kruegers), ‘You know, if the authorities find out they’re going to kill you too,’ and they said, ‘We are responsible to God, not to him (Hitler), and we feel if there’s any way to help somebody and to do something that prevents anybody from getting killed, we do it.’”

This courageous attitude struck a chord in Joe, who has tried living up to the kindnesses people bestowed on him and his family.

“It’s amazing in a situation like this that you find people that have a different way of thinking and they feel it’s immoral for others to be killed or whatever just because they’re Jewish. People helped even though they knew if they got caught they would get shot. Despite the risk, they said, ‘No, we have a responsibility to God, but not to Mr. Hitler, and whatever happens, happens,’ and that’s why quite a few Jewish people had a chance to live.”

From the time Joe was taken away in the middle of the night to the war’s end, six years passed before he was reunited with his family. He would survive six camps in four countries, counting the displaced persons and refugee camps he ended up in after the war, before the ordeal was over.

“The first camp I was in was Sachsenhausen — it was a concentration camp close to Berlin where all kinds of political prisoners, religious people were together, gypsies too. Just a very, very interesting group of people, and then from there they distributed them to the other camps.”

He didn’t know anyone at Sachsenhausen.

“I didn’t want to know anybody because in a situation like this it’s very difficult to trust people you don’t know. Sometimes you had to, but unfortunately you had a lot of Jewish people who tried to inform the Nazis of what was going on, hoping they might have a better life, which didn’t happen.”

Upon his arrival, Joe was consumed with anger over the injustice of it all.

“I was 17-years-old and the only crime I’d committed was I was born to a Jewish mother. That’s why I could never understand why I had to go through all this. I wasn’t thinking about anything else but why I’m here. I didn’t steal anything, I didn’t murder anyone — why am I here, what’s the reason? Why couldn’t I get my education so I could become somebody and get further on in life later? Why? — because I was Jewish. I could not get over that.”

Then some things happened those first 24 hours in camp to change his outlook.

“I was so mad that when we came in the barracks in the evening I said, ‘I think if I ever by any chance come out of this place I will kill every German that comes in my way.’ Somebody tapped me on my shoulder and said, ‘No my son, if you do this you’re not any better than the Nazis.’” It started him thinking.

“The next morning we had to stand in a roll call and an elderly man fell down and, of course, I bent down trying to help him and one soldier came and shoved this rifle in my back and so I fell down, too. We were carried into the barracks and the older prisoners told me, ‘If you want to stay alive you don’t see anything around you.’ Well I was a person that wanted to see what life was all about and I was trying to live a little longer if I could, and so I followed this advice.”

Joe was also befriended by an elderly Catholic priest whose selfless example made a big impact on him. When the meager bread ration was given out, Joe said, the old priest gave away his portion to Joe and other young people. “He told us, ‘You need it more than I do, I have nothing to look forward to, it’s God’s will.’ It taught me there are people who really care for other people.”

After two years at Sachsenhausen Joe was transported to Buchenwald in 1941.

“Buchenwald was horrible for me because I was delegated to be on the railroad platform as trains came in from Holland and Belgium. I would pick up the suitcases and possessions people carried. The hardest thing for me was seeing women come with little children in their arms and the children, some not even a year old, were taken away and thrown on the platform. Some guards did much more worse — they used them as target practice. I still have nightmares about this.”

It took all of Joe’s self-discipline to not respond, not intervene, not retaliate.

“I was strong enough I could probably have killed some guards but that wouldn’t do me any good because two minutes later people would be shot on the spot. It doesn’t help me or nobody else either. It was a hard decision to make but unfortunately that’s the way it worked.”

Living conditions were abysmal in every concentration camp, but he said the treatment by the Buchenwald guards was particularly harsh.

“The guys that watched us were much more brutal in Buchenwald than they were in Sachsenhausen. They got a bottle of whiskey in the morning to drink to get them in the mood of tormenting us. They were specially trained, they had only one thing in mind, make sure the people don’t get out of here alive.”

As part of the Nazi program of humiliating prisoners, he said, inmates were given absurd tasks meant to break their mind and spirit.

“We had to do idiotic things, like they had a room that needed to be cleaned and they give us a toothbrush to clean the walls. It made you feel degraded. This is the evil of the world — to not treat us like human beings. They didn’t want you to feel as a human being anymore — well, they didn’t have any luck with me.”

Death, hunger, toil and beatings became every day occurrences.

“In our barracks we had bunk beds, with maybe four or five people laying there in a clump, and very often when you woke up in the morning somebody was dead. It took me a long time to get over those deaths,” he said.

Hardening himself to his reality became a necessary thing.

“I always thought a little bit different — that I’m in a situation where I have to do certain things and I’m looking for a loophole maybe somewhere to improve my situation. Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. I was able to be pretty open with the people that were surrounding me in trying to explain how important it was for our little group here to hold together and not go to the Nazis, that we had to stick together and try to improve our lives — that was the only way to make it happen. Some of them did and some of them didn’t.

“Some didn’t have the will (to live) anymore. One guy told me, ‘What difference does it make?’ Some people had a little bit of sense left. I had the will to live. I prayed to God, ‘I know if you want you will give me the strength to fight back in a way to keep my mouth shut when I should,’ instead of saying something that would give them the opportunity to beat me or to restrict food from me.”

That resolve and restraint, he said, “was not very easy because when you work hard 10-12 hours a day with nothing to eat your mind is mush. I tried to get rest as much as I could because I knew that’s what I needed. Somehow I still kept on going.”

He kept alert for work details that might provide a scrap more food or be out of harm’s way. “If somebody was really weak I jumped in and told them, ‘I’ll do it.’” That may have saved his life when he got to Auschwitz-Birkenau in late ’44.

“I ended up in Auschwitz,” whose dark reputation, he said, preceded it — “somehow it went from camp to camp what happened there. I knew if I would stay there that would be it. My strength was down, we were beaten every day, we had no good food, we had to work. I wasn’t Superman, I just was a simple human being who can take only so much. I was lucky to get out of there.”

It just so happened a work detail was formed and Joe was in the right place at the right time to be assigned it. “I was there three weeks and then some officer came and he saw me and put me to work in the stone quarries on the Polish-German border, near Hindenburg. There was a big forest around us. We slept in tents.”

In early 1945 the quarry camp came under bombardment from advancing Russian forces and Joe and some fellow prisoners used the cover of chaos to flee.

“There were about 10 of us and we said, ‘Let’s go, no matter what.’ We escaped in the big forest there. Some of us were pretty weak. We were afraid the guards might set their dogs on us, so we tried to put as much distance between us and them, but most of the guards had fled — they didn’t want to get in the Russians’ hands.”

After foraging on the road for six or seven days Joe and his mates were liberated by Russian Army troops. “We were lucky,” he said, “there was a Jewish major in their ranks who spoke Yiddish and he warned us not to eat the uncooked bacon the Russians spread out to feed us. He said after what we’d been through it would kill us.”

The major didn’t warn about the bottled drinks the Russians offered.

“It looked like water to me, I was so thirsty, so I drank and I almost died — it was 100 percent vodka,” said Joe, who can smile about it now.

Joe weighed 82 pounds when rescued. He spent two months in a Russian military hospital. Once he regained his strength, he made his way to Holland, mostly by hitching rides with G.I. transports. His family had agreed to meet there if they were ever separated during the war. His mother’s brother had fled there. He hoped his family had survived but he had no real expectation of seeing them again.

Amazingly, he said, “we all came out of it. We were lucky. Slowly but surely everybody made their way to Holland.” His mother had survived as a laundress for the German military, his father escaped a camp before being pressed into duty making military roads, Ruth worked in a labor munitions camp and Gisela remained hidden.

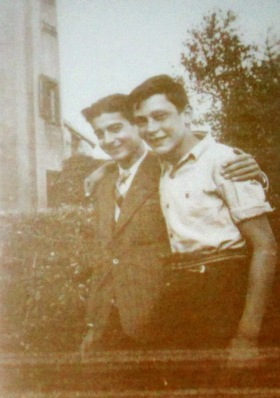

The Boins spent the next year in a D.P. camp, where Joe met the woman who became his wife, the former Lilly Engelmann Margulies. She was a survivor of Theresienstadt (Terezin). Having lost her husband, parents and siblings, Lilly was all alone and the Boins became her protectors and friends. There was a considerable age difference between Joe and Lilly but the attraction was mutual.

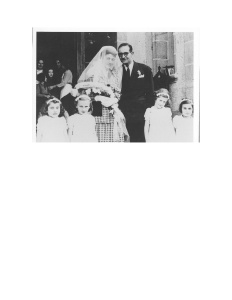

“We liked each other. Then, of course, I asked her one day ‘will you marry me?’ and she looked at me and said, ‘no,’ and I didn’t take no for an answer, I wanted an explanation. So she told me, ‘Well, I’m 14 years older than you,’ and I said, ‘So what?’ So we got married in Amsterdam and we were married 50 years.”

With no prospects or permits for starting a new life in war-ravaged Europe, the couple, along with Ruth and Gisela, embarked on an epic journey to reach the promised land of Palestine. Traveling with no visas, they made their way to France and Belgium.

Out on the Mediterranean Sea they risked being turned back by authorities or being turned in by mercenaries, but enough angels helped their cause. Making the trip more hazardous was Lilly’s pregnancy. They arrived in Haifa on a Turkish coal boat in 1946. Among the early Holocaust survivors in Palestine, their testimony of the genocide they witnessed fell on deaf ears at first.

“When we first went to Israel, our own people didn’t believe us. They said, ‘Oh you just want sympathy,’ until some of their relatives came and told them. It’s something people couldn’t imagine, that human beings can do this to other human beings, and to children.”

Like many survivors Joe was angry the world largely turned a blind eye to the plight of millions. He said while some lost their faith, he did not.

“Many people said, ‘Where was God? I don’t believe in God anymore.’ That’s your privilege, but let me tell you something, it had nothing to do with God — people are the ones who did it, you can’t blame everything on God. What happened, happened, I cannot repair it, I have to go with what I have now. You have to live with it and you have to make the best you can to keep on living.”

He joined the Israeli Army and was shot in the stomach during a rescue mission. A doctor told Lilly he wouldn’t make it.

“Here I am,” said Joe, the perpetual survivor. He worked odd jobs overseas. In the U.S. he was a botanical gardens curator before going into business as a locksmith. His picks can open anything but safes.

His wife Lilly died in 1995 after a long illness that saw him care for her at home. “I thought my life came to an end,” he said, “but there’s a reason for everything. I never want anybody to feel sorry for me. I’m grateful for what I have.”

He’s dismayed atrocities still go on around the world. “People killing in the name of I don’t know what. How is that possible? Why didn’t people learn and see what comes out of this? You have to sit down with people and talk to them — there always is a way if you have the will to do it.”

A supporter of Omaha’s TriFaith Initiative, Joe counts Christians and Muslims among his friends and he believes the more interfaith, multicultural dialogue there is, the less likely it is genocide will occur. He does not allow his survivor past to define him but instead uses the experience to practice and preach tolerance.

“You know, the memories are fading away, but this is something that’s inside you. I will never forget what happened, but I am a person that looks forward, I don’t want to look back. I learned not to hate anymore. It gives me more of a reason to try to see that other people are treated like human beings,” he said.

“Try to help whoever you can because you never know – someday you might need help and they will help you. I love life, I love people. I believe in live-and-let-live. Enjoy life as much as you can and do good as much as you can. If you’re a good person and trying to live in the world you have to respect other people’s beliefs, and I try to do that.”

The Kripke Library’s copy of Lilly’s book contains an inscription Joe could have written hmself: “Experience is a hard teacher because she gives the test first, the lesson afterwards.”

He’s written his own Holocaust reflections, including a prayer:

“I am thankful that I could see life from every angle. I learned how to be rich and how to be poor, how to give orders and how to take orders, how to live in a big family with a lot of friends and how it is to be completely alone. I learned to appreciate health, so I could endure pain. I met the ugly, so I was able to enjoy the beauty. I know how to live in a mansion, but be content to live in a bathroom … to own a Mercedes and to walk barefoot the dusty, stony road. When I was in prison I realized the value of freedom …

“I have met people who found consolation. In helping those who could not help themselves they had put their own life in danger…I saw goodness at its best and bestiality at its worst … I got the taste of almost unbearable disaster and I was blessed to have again a wonderful family, who brought so much happiness into my life … Thank you God … for all the experiences I had in two ways of life.”

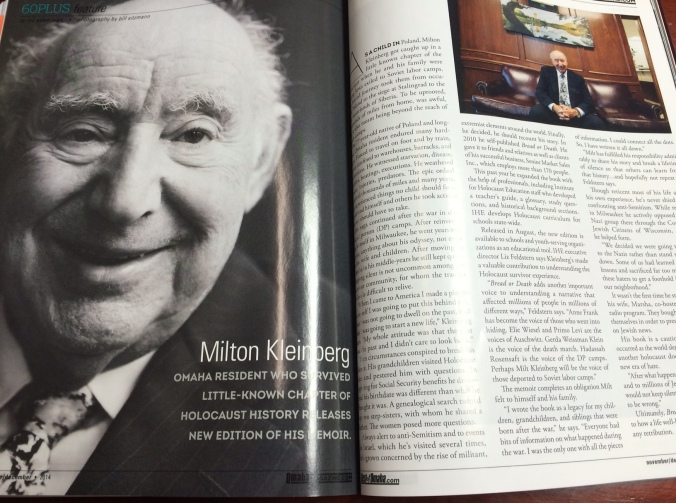

Milton Kleinberg

Milton Kleinberg