Walter Reed: Former hidden child survives Holocaust to fight Nazis as American GI

About nine years ago I was given the opportunity to meet and profile Walter Reed, whose story of escaping the Final Solution as a Hidden Child in his native Belgium and then going on to fight the Nazis as an American GI a few years later would make a good book or movie. Here is a sampling of his remarkable story now, more or less as it appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). You’ll find many more of my Holocaust survival and rescue stories on this blog.

Walter Reed: From out of the past – Former hidden child survives Holocaust to fight Nazis as American GI

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Imagine this: The time is May 1945. The place, Germany. The crushing Allied offensive has broken the Nazi war machine. You’re 21, a naturalized American GI from Bavaria. You’re a Jew fighting “the goddamned Krauts” that drove you from your own homeland. Five years before, amid anti-Jewish fervor erupting into ethnic cleansing, you were sent away by your parents to a boys’ refugee home in Brussels, Belgium. Eventually, you were harbored with 100 other Jewish boys and girls in a series of safe houses. You are among 90 from the group to survive the Holocaust.

Relatives who emigrated to America finagle you a visa and, in 1941, you go live with them in New York. You abandon your heritage and change your name. Within two years you’re drafted into the U.S. Army. At first, you’re a grunt in the field, but then your fluency in German gets you reassigned to military intelligence, attached to Patton’s 95th Division, interrogating German POWs. If this were a movie, you’d be the avenging Jewish angel meeting out justice, but you don’t. “The whole mental attitude was not, Hey, I’m a Jew, I’m going to get you Nazi bastard,” said Walter Reed, whose story this is. “I had no idea of revenging my parents. We were really more concerned about our survival and getting the information we needed.”

By war’s end, you’re in a 7th Army unit rooting out hardcore Nazis from German institutions. You don’t know it yet, but your parents and two younger brothers have not made it out alive. You borrow a jeep to go to your village. Your family and all the other Jews are gone. You demand answers from the cowed Gentiles, some you know to be Nazi sympathizers. You intend no harm, but you want them scared.

“I wasn’t the little Jewish boy anymore,” said Reed. “Now, they saw this American staff sergeant with a steel helmet on and with a carbine over his shoulder. At that point, we were the conquerors and those bastards better knuckle under or else. I asked, What happened to my family and to the other Jewish people? They told me they were sent to the east into a labor camp. That’s about all I could find out.”

It is only later you learn they were rounded-up, hauled away in wagons, and sent to Izbica, a holding camp for the Sobidor and Belzec death camps, one or the other of which your family was killed in, along with scores of friends and neighbors.

Walter Reed, now 79, is among a group of survivors known as the Children of La Hille, a French chateau that gave sanctuary to he and his fellow wartime refugees. A resident of Wilmette, Il., Reed and his story have an Omaha tie. After the war, he graduated from the prestigious University of Missouri School of Journalism and it was as a fund raising-public relations professional he first came to Omaha in the mid-1950s when he led successful capital drives at Creighton University for a new student center and library. “Part of me is in those buildings,” he said.

More recently, he began corresponding with Omahan Ben Nachman, who brings Shoah stories to light as a board member with the local Hidden Heroes of the Holocaust Foundation. A friend of Nachman’s — Swiss scholar and author Theo Tschuy — led him to accounts of La Hille and those contacts led him to Reed. In Reed, Nachman found a man who, after years of burying his past, now embraces his survivor heritage. With Reed’s help, Tschuy, the author of Dangerous Diplomacy: The Story of Carl Lutz and His Rescue of 62,000 Jews, is researching what will be the first full English language hardcover telling of the children’s odyssey.

On an April 30 through May 2 Hidden Heroes-sponsored visit to Nebraska, Reed shared the story of he and his comrades, about half of whom are still alive, in presentations at Dana College in Blair, Neb. and at Omaha’s Beth El Synagogue and Field Club, where Reed, a Rotary Club member, addressed fellow Rotarians. A dapper man, Reed regales listeners in the dulcet tones of a newsman, which is how he approaches the subject.

“I’m a journalist by training. All I want is the facts,” he said, adding he’s accumulated deportation and arrest records of his family, along with anecdotal accounts of his family’s exile. “I’m simply overwhelmed by the wealth of information that exists and that’s still coming out. In the last 10 years I’ve found out an awful lot of what happened. I don’t have any great details, but I have vignettes. So, my feeling when I find out new things is, Hey, that’s terrific, and not, Oh, I can’t handle it. None of that. Long, long ago I got over all the trauma many survivors feel to their death. I vowed this stuff would never disadvantage me.”

As he’s pieced things together, a compelling story has emerged of how a network of adults did right amid wrong. It’s a story Nachman and Reed are eager for a wider public to know. “It shows how a dedicated group of people, most of whom were not Jewish, coordinated their actions to prevent the Nazis from getting at these Jewish children,” said Nachman, who paved the way for the upcoming publication of a book by a La Hille survivor. “They chose to do so without promise of any reward but out of sheer humanitarian concern. It’s a story tinged in tragedy because the children did lose their families, but one filled with hope because most of the children survived to lead productive lives.”

It was 1939 when Reed made the fateful journey that forever separated him from his parents and brothers. Born Werner Rindsberg in the rural Bavarian village of Mainstockheim, Reed was the oldest son of a second-generation winemaker-wine merchant father and hausfrau mother. His was among a few dozen Jewish families in the village, long a haven for Jews who paid local land barons a special tax in return for protection from the anti-Semitic populace. Reed said Jews enjoyed unbothered lives there until 1931-1932, when Nazism began taking hold.

“I was aware of the growing menace and danger when I was about 8 or 9 years old. I recall constant conversations between my parents and their Jewish peers about Hitler. The Nazis marched up and down our main street with their swastika flags and their torches at night, singing their songs. This was a very close-knit community of about 1,000 inhabitants and you knew which kid had joined the Hitler Youth and whose dad was a son-of-a-bitch Nazi. Pretty soon, the kids began to chase us in the street and throw stones at us and call us dirty names. Then, the first (anti-Jewish) decrees came out about 1934 and increasingly got stricter.”

Pogroms of intimidation began in earnest in the mid-1930s. Reed remembers his next door neighbor, a prominent Jewish entrepreneur, taken away to Dachau by authorities “to scare the hell out of him. It saved his life, too,” he said, “because that hastened his decision to get the hell out of Germany. This stuff was going on in other towns and villages where I had relatives. In those places, including where my mother’s brothers and sisters lived, the local Nazis were more rabid and…they hassled the Jews so much they left, and it saved their lives.”

Things intensified in November 1938 when, in retaliation for the assassination of a German diplomat by an expatriate Polish Jew outraged by the mistreatment of his people, the Nazis unleashed a terror campaign now known as Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass). Roving gangs of brown-shirted thugs attacked and detained Jewish males, vandalizing, looting, burning property in their wake. Reed, then 14, and his father were dragged from their home and thrown into a truck with other captives. As the truck rumbled off, Reed recalls “thinking they were going to take us down to the river and shoot us or beat the hell out of us.” The boys among the prisoners were confined in the jail of a nearby town while the men were taken to Dachau. Reed was freed after three nights and his father after several weeks.

|

| The barn near Toulouse, France, where Walter Reed stayed as part of a children’s rescue colony |

In that way time has of bridging differences, Reed’s recent search for answers led him to a group of school kids in Gunzenhausen, a Bavarian town whose Jewish inhabitants met the same fate as those in his birthplace. The kids, whose grandparents presumably sanctioned the genocide as perpetrators or condoned it as silent witnesses, have studied the war and its atrocities. Reed began corresponding with them and then last year he and his wife Jean visited them. He spoke to the class, and to two others in another Bavarian town, and found the students a receptive audience.

“Frankly,” he said, “I find these encounters very worthwhile and uplifting. I was told by the teachers and principals it was quite a moving experience for the students to come face-to-face with history. My visit is now on the web site created by one class. On it, the students say they were especially moved by my stated conviction that the most important lesson of these events is to hold oneself responsible for preventing a repetition anywhere in the world and that each of us must bear that responsibility.”

When his father returned from Dachau, Reed recalls, “He looked awful. Emaciated. He wasn’t the same man. When we asked him what it was like he just said he’s not going to talk about it.” It was in this climate Reed’s parents decided to send him away. He does not recollect discussions about leaving but added, “I recently found a letter my father wrote to somebody saying, ‘I finally persuaded Werner to leave,’ so I must have been reluctant to go.”

A question that’s dogged Reed is why his parents didn’t get out or why they didn’t send his brothers off. It’s only lately he’s discovered, via family letters he inherited, his folks tried.

“Those letters tell a story,” he said. “They tell about their efforts to try and get a visa to America. My dad traveled to the American consulate in Stuttgart and waited with all the other people trying to get out. They gave my parents a very high number on the waiting list, meaning they were way down on the queue. There are anguished letters from my father to relatives referencing their attempts to get my brothers out, but that was long after it was too late. In no way am I castigating my parents for making the wrong decision, but they could have sent my brothers (then 11 and 13) because in that home in Brussels we had boys as young as 5 and 6 whose parents sent them.”

|

| Walter Reed, third from right in the front row, at the chateau in La Hille, France, where a smaller group of children were transferred from the barn near |

Home Speyer, in the Brussels suburb of Anderlecht, is where Reed’s journey to freedom began in June 1939. Sponsored by the city and afforded assistance by a Jewish women’s aid society, the home was a designated refugee site in the Kinder transport program that set aside safe havens in England, The Netherlands and Belgium for a quota of displaced German-Austrian children. Where the transport had international backing and like rescue efforts had the tacit approval of German-occupied host countries, others were illegal and operated underground. Reed said the only precautions demanded of the La Hille kids were a ban on speaking German, lest their origins betray them as non-French, and a rule they always be accompanied outside camp grounds by adult staff. Despite living relatively in the open, the children and their rescuers faced constant danger of denouncement.

The boys at Home Speyer, like the girls at a mirror institution whose fates would soon be mingled with theirs, arrived at different times and from different spots but all shared a similar plight: they were homeless orphans-to-be awaiting an uncertain future. Reed doesn’t recall traveling there, except for changing trains in Cologne, but does recall life there. “For a young boy from a small Bavarian farm village,” he said, “Brussels was an exciting city with its large buildings, department stores, parks and museums. We made excursions into the beautiful Belgian countryside. And there was no more anti-Semitic persecution.”

This idyll ended in May 1940 when German forces invaded Belgium. Reed said the director of the girls home informed the boys’ home director she’d secured space on a southbound freight train for both contingents of children.

“We packed what we could carry and took the streetcar to the train station,” he notes. “Late that night two of the freight cars were filled by the 100 boys and girls as the train began its journey to France.”

Adult counselors from the homes came with them. The escape was timely, as the German army reached Brussels two days later. En route to their unknown destination, Reed said the roads were choked with refugees fleeing the German advance. Unloaded at a station near Toulouse, the children were trucked to the village of Seyre, where a two-story stone barn belonging to the de Capele family quartered them the next several months. It appears, Reed said, the de Capeles had ties to the Red Cross, as the children’s homes did, which may explain why that barn was chosen to house refugees.

“It lacked everything as a place to live or sleep,” he said. “No beds, no mattresses, no running water, no sanitary facilities, no cooking equipment. Food was scarce, Pretty soon we ran out of clothes and shoes. Everything was rationed. A lot of us had boils, sores and lice.”

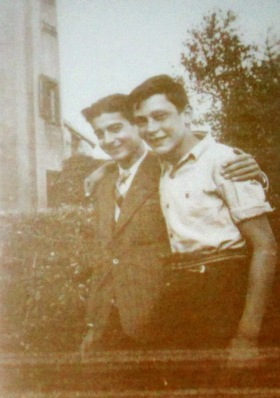

|

| Walter Reed with a close friend who would perish not long thereafter |

With 100 kids under tow in primitive, cramped conditions, the small staff struggled. “They were trying to manage this rambunctious group of kids, who played and fought and caused mischief. The older kids, myself included, were deputized to sort of manage things. We taught classes out in the open. We worked on nearby farms in the hilly, rolling countryside, cutting brush…digging potatoes. For compensation we got food to bring back. It was like summer camp, except it was no picnic,” he said. “We all grew up fast. We learned about survival, self-reliance and cooperation for the common good.”

It was not all bad. First amours bloomed and fast friendships formed. Reed struck up a romance with Ruth Schuetz Usrad, whose younger sister Betty was also in camp. He also found a best friend in Walter Strauss.

The barn’s occupants were pushed to their limits by “the harsh winter of 1940,” Reed said. They got some relief when the group’s Belgian director, Alex Frank, got the Swiss Children’s Aid Society, then aligned with the Swiss Red Cross, to put Maurice and Elinor Dubois in charge of the Seyre camp, which they soon supplied with bedding, furniture and Swiss powdered milk and cheese.

With the Nazi noose tightening in the spring of 1941 the Dubois relocated the children to an even more remote site — the abandoned 15th century Chateau La Hille, near Foix in the Ariege Province — where, Reed said, “they were less likely to be detected.” It was here the children remained until either, like Reed, they got papers to leave or, like others, they dispersed and either hid or fled across the border. Some 20 children came to the states with the aid of a Quaker society.

As chronicled in various published stories, Reed said that in 1942, a year after he left, 40 of the children, including his girlfriend Ruth, were arrested by French militia and imprisoned at nearby Le Vernet. Inmates there were routinely transported to the death camps and this would have been the children’s fate if not for the intervention of Roseli Naef, a Swiss Red Cross worker and the then La Hille director, who bicycled to Le Vernet to plead with the commandant for their release. When her entreaties fell on deaf ears, she alerted Maurice Dubois, who bluffed Vichy authorities by threatening the withdrawal of all Swiss aid to French children if the group was not freed.

The officials gave in and the children spared. Reed said he has copies of records documenting Naef’s termination by the Swiss Red Cross for her role as a rescuer of Jews, the kind of punitive disapproval the Swiss were known to employ with other rescuers, such as diplomat Carl Lutz.

In getting out when he did, Reed realizes he “was one of the lucky ones,” adding, “Others had to use more extraordinary means to escape, like my friend Walter Strauss. He tried escaping across the Swiss border with four others. They were caught. He was sent back and was later arrested and killed in Auschwitz.” Ruth left La Hille and led a hidden life in southern France, joining the French Underground. She reportedly had many narrow escapes before fleeing across the Pyrenees into Spain and then Israel, where she helped found a kibbutz and worked as a nurse.

It was at a 1997 reunion of Seyre-La Hille children in France that Reed saw Ruth and his former companions for the first time in 50-plus years. Keen on not being a “captive” of his past, he’d dropped all links to his childhood, including his Jewish identity and name. Other than his wife, no one in his immediate family or among his friends knew his survivor’s tale, not even his three sons.

For Reed, the reunion came soon after he first revealed his “camouflaged” past for the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History project. Then, when his turn came to tell his biography before a Rotary Club audience, he asked himself — “Do I step out of my closet or do I keep hiding from my past?” Opting to “go through with it,” he shared his story and “everything flowed from there.” After attending the ‘97 La Hille reunion, Reed and his wife hosted a gathering for survivors in Chicago and another in France in 2000.

On the whole, the survivors fared well after the war. Two Seyre-La Hille couples married. A pair enjoyed music careers in Europe — one as a teacher and the other as a performer. Nine of the adult camp directors-counselors have been honored for their rescue efforts as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in Israel. Reed has visited many of the sites and principals involved in this conspiracy of hearts. The Chateau La Hill is still a haven, only now instead of harboring refugees as a rustic hideout it shelters tourists as a trendy bed-and-breakfast.

For Reed, taking ownership of his past has brought him full circle.

“Even though our lives have taken many different paths all over the globe, nearly all my surviving companions feel a strong bond with each other. Many have strong ties to the places and persons that gave us refuge during those dangerous and turbulent years of our youth. I think a lot of things happened then that shaped me as a whole. It inculcated in me certain attributes I still have — of taking responsibility and running things.”

Above all, he said, the experience taught him “to resist oppression and discrimination,” something he and his wife do as parents of a child with cerebral palsy. “For me, recrimination and anger are not a suitable response. It’s important we strive for reconciliation and understanding. Then we live the legacy.”

Related articles

- Art Trumps Hate: ‘Brundinar’ Children’s Opera Survives as Defiant Testament from the Holocaust (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- David Kaufmann: A Holocaust Rescuer from Afar (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

-

June 12, 2018 at 11:29 pmLife Itself V: Jewish-themed and related stories from 1998-2018 | Leo Adam Biga's My Inside Stories

-

August 11, 2018 at 4:30 pmLife Itself XV: War stories | Leo Adam Biga's My Inside Stories