Archive

In case you missed it: Hot Movie Takes November 15, 2017 through March 12, 2018

Hot Movie Takes – “A Perfect Day” (2015)

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

The 2015 dark comedy “A Perfect Day” is the first film I’ve seen by acclaimed Spanish writer-director Fernando León de Aranoa and I don’t need to see anything else by him to know that he has major filmmaking chops. This is easily one of the better films I’ve seen from the past few years with its funny, ironic, disturbing and moving portrayal of international aid workers encountering a series of surreal but all too human situations in the uneasy peace and devastation of the ethnic fueled Balkans War, Working with an excellent international cast headed up by Benicio del Toro, Tim Robbins, Mélanie Thierry, Olga Kurylenko and Fedja Štukan and employing a largely Spanish creative crew led by cinematographer Alex Catalán, editor Nacho Ruiz Capillas and composer Arnau Bataller, Aranoa has created a seering companion piece to David O. Russell’s classic “Three Kings.” Where that earlier film set during the Gulf War in Iraq is filled with excessive violence amidst its satire of a disparate team finding more than they bargained for in a vainglorious looting adventure turned humanitarian mission, we do not see a single act of violence committed in “A Perfect Day.” But we do see its aftermath, along with dark intimations that the horrors, atrocities and divisions are still close at hand and might erupt again at any moment.

The movie begins with our four main protagonists, Mambru (del Toro), B (Robbins), Damir ((Stukan) and Sophie (Thierry) stuck for a solution on how to remove a corpse that’s been dumped in a fresh water well that area rural residents depend on for their drinking and cooking supply . As head of security for this Aid Across Borders mission, Mambru is in charge of the operation. His assigned interpreter Damir helps as best he can. Mambru’s colleague B brings Sophie, a sanitary water expert, to the site. But nothing is easy in conditions where basic infrastructure and civility have broken down. Even getting rope for the unpleasant job proves next to impossible. Then the team is warned by higher authorities that the corpse cannot be touched. Political jurisdictional protocols take precedence over practical realities. All this gets ratcheted up to a new level when Katya (Kurylenko) arrives, ostensibly to shut down the entire mission, but ends up stuck with the others in the wilds of the Balkan hinterlands. Adding to the tension, Mumbru and Katya once had a fling. Then Sophie witnesses something she shouldn’t and for the first time she understands the extent of the human toll. Along for the ride is an orphaned boy Mumbru befriends and shields from unimaginable tragedy. The team travels in a two-jeep caravan across treacherous mountain roads made more dangerous by mines buried in the dirt. Every encounter with the conflict’s survivors is fraught with anxiety because life has turned into bitter hardship, distrust, exploitation and trauma.

Benicio del Toro is perfect as the world-weary but still good-hearted and impassioned Mambru. Tis engaging character wants to make a difference despite all the regulations and restrictions that often tie his hands. Robbins is also just right as the free-spirited B. He always tries to find the humor in the carnage. As a native of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Yugoslavia, Stukan Damir could not be any more authentic as Damir. He brings a stoic yet empathetic presence that counterbalances the overt sensibilities of del Toro and Robbins. As the sweet yet feisty Sophie, Thierry creates an indelible portrait of a stubborn idealist whose naivete is shattered but whose commitment remains unchanged. As the calculating Russian bureaucrat Katya, Kurylenko transforms her from cold and superficial to more humanistic. Katy’s experience on the ground with this makeshift team and the challenges they happen upon opens her eyes to how much more needs to be done before survivors’ lives can return to any semblance of normality.

The filmmaker, León de Aranoa, and his team do an excellent job immersing us in this no-man’s land where everyone must find his or her accommodation with evil and indifference. The story reminds us how hard it is to do humanitarian work in war ravaged countries where ethnic divides persist, basic services may not exist, threats loom around every corner, the native people may not even want you there and red tape often prevents you from lending aide. Defying all that to try and do the right thing anyway takes some chutzpah. In keeping with the story’s irony, the team is once and for all foiled in their efforts to extricate the corpse from the well only to have a force greater than themselves do it for them.

“A Perfect Day” is available on Netflix.

https://www.traileraddict.com/a-perfect-day-2015/trailer

Hot Movie Takes – “Black Panther”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Five days after seeing “Black Panther” and my head is still reeling from the sheer volume of ideas bound up in it. It’s hard to know where to begin, so let me just start by saying that this film absolutely works as an intellectually and visually engaging dramatic story whether or not you’re a fan of the superhero fantasy genre and have any familiarity with the comic book characters on which it’s based. I am a moderate fan of superhero movies. I have never seen a Black Panther comic. I’d never even heard of this particular character until the movie came out. So I went into Black Panther only knowing it was based on a Marvel character whose front and back stories are replete with African and African-American themes and that it was a word-of-mouth, must-see phenomenon. Upon seeing the film adaptation for myself, I can see why people are so excited about this picture. First off, it is refreshing to see a black superhero and universe depicted with such love on the big screen. And to have such a strong central character, T-Chailia (Chadwick Boseman), ruling over such a technologically advanced mythical kingdom (Wakanda) that resists white colonial encroachment and corruption is a truly empowering thing. I love that the Wakandans have secret agents working all over the world to monitor goings-on as an early warning system about any potential threats to the kingdom, Having T-Chailia’s uncle, N’Jobu, working undercover in urban, African-American-centric Oakland, Calif. is very thought-provoking, as is N’Jobu feeling that his people should be sharing rather than hiding their advanced ways, especially with their oppressed brethren in places like America. Then there are the sub-plots. Racist white South African smuggler Ulysses Klaus (Andy Serkis) has stolen a quantity of the precious Wakandan resource, vibranium, and uses it for his own criminal gain. He’s also attempting to make it available to the highest bidder, believing it’s wasted in hands of the Wakandans, whom he regards as savages. The most potent subplot of all is the emergence of N’Jadaka (Michael B. Jordan), the step-brother that T-Chailia never knew he had, who is intent on claiming the throne he believes is his to take. Growing up in Oakland as the unacknowledged heir to the Wakanda throne, N’Jadaka works up a lifelong hatred for having been abandoned. Experiencing firsthand how African-Americans are an oppressed people makes him despise the way Wakanda chooses to withhold its power from the the black diaspora. Straight out of a Shakespearean drama, he plots to overthrow his step-brother and to assert his place at the royal table. Not content with stopping there, he also intends unleashing the weapons of Wakanda by putting them in the hands of black brethren and thus leading a resistance against white colonizers everywhere. The ensuing conflict is classic stuff.

Providing further fuel to the drama’s fire is our protagonist’s independent former lover, the War Dog Nakia, played by Lupita Nyong’o, and the fiercely loyal Okoye (Danai Guirra) as the head of the all-female special forces. Shuri (Letitia Wright) is T’Challa’s sweet, saucy and brilliant sister who is the lead technology designer for the nation. M’Baku (Winston Duke) is a proud mountain tribe leader caught between tradition and progress whose attempt at wresting control doesn’t mean he’s disloyal, only ambitious and looking out for his own people’s interests.

Then there is the whole subplot involving CIA operative Everett K. Ross (Martin Freeman), who eventually gets directly caught up in the fight to save Wakanda from a fate worse than death.

The cast is superb. Boseman has the strength and grace needed for T’Challa. Angela Bassett doesn’t have much to do as his mother, but she’s appropriately regal, wounded and indefatigable. Jordan has the right resentment and rage as the wronged sibling. Serkis is a bit over the top for my tastes as the villain but he does make it easy to hate his character, which is the point. But it’s the three young women who play the characters of Nakia, Okoye and Shuri that I will remember most from this film. They are strong, smart, beautiful black women whose loving, selfless acts help preserve a nation.

Director-cowriter Ryan Coogler (“Fruitvale Station,” “Creed”) deserves major props as does co-writer Joe Robert Cole, cinematographer Rachel Morrison, production designer Hannah Beachler, the art direction teams headed by Alan Hook, set decorator Jay Hart, costumer designer Ruth E. Carter, the makeup department and, of course, the entire visual effects team. They’ve taken the spirit of the comic and all its evolutions over the years and brought it to life in a way that makes it work for general audiences even with its strong black nationalist and pan-African themes. Mainly, though, it has universal humanist themes that speak to us all. And in the Black Lives Matter era, no superhero, comic-book inspired movie could be more timely than this.

https://www.traileraddict.com/black-panther-2018/trailer

Hot Movie Takes – “The Gift”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Hands-down, the best film I’ve seen from the past few years is “The Gift,” a superb psychological thriller that is nearly the equal of Hitchcock’s masterpieces. This stunning 2015 feature directional debut by actor Joel Edgerton, who wrote the intelligent screenplay and delivers a haunting central performance as the enigmatic Gordon and elicited fine performances by his co-stars Jason Bateman and Rebecca Hall, is pretty much right there with the best ever directed films by artists known primarily as actors – joining the ranks of Robert Duvall’s “The Apostle” and Robert Redford’s “Ordinary People.” I’m tempted to say it’s equal to Charles Laughton’s “The Night of the Hunter,” but the only reason I hesitate to put it in that company (and it’s the same reason I’m slightly reluctant to compare it to the best by Hitchcock) is that while it is visually sophisticated it doesn’t stretch the medium the way Hitch and Laughton did.

But that’s quibbling over small stuff. “The Gift” is available on Netflix and all I can say is that it is required viewing for anyone who loves cinema and appreciates a good suspense-mystery. Truthfully, this film defies categorization though. It has thriller elements that reminded of the classics “Shadow of a Doubt,” “Strangers on a Train,” “Cape Fear” and “Seven, but it also works equally well as a domestic drama whose married couple protagonists Simon (Bateman) and Robyn (Hall) are in a relationship that appears perfect on the surface but begins devolving when Gordon, an old high school classmate of Simon’s, suddenly appears in their lives. Gordon is socially awkward but sweet. We learn that Simon and Robyn are starting anew after she lost a fetus and developed a prescription drug habit. They have a gorgeous new home and he’s in line for a huge promotion at work. When Gordon begins a pattern of giving the couple inappropriately extravagant gifts, Simon is alarmed and Robyn is charmed. Things get very strange and strained as Simon believes Gordon is obsessed with his wife and Robyn intuits he’s been breaking into their house. Or has she been imagining things? It increasingly appears as if Gordon is unhinged and meaning to do them harm. But the real sociopath may be Simon. A series of creepy, nerve-wracking confrontations occur that heighten our sense of dread even though nothing overtly violent or horrible unfolds.

Edgerton has created an intoxicating, edge-of-your-seat drama through brilliant intimation and a twist so delicious that it’s bound to be much imitated. Kudos for casting Bateman as ambitious Simon, whom his wife begins catching in lies that reveal an ugly truth he’s concealed. His real nature and something that happened between him and his old classmate decades ago in high school is what drives the story to its emotionally devastating conclusion. Simon thinks he’s put behind him the incident that transpired. But as Gordon tells him, “The past isn’t through with you.”

Edgerton is mesmerizing as Gordon, whom he plays as a sinister innocent. He reminds me of a cross between John Savage and Michael Shannon. Bateman has never been better as Simon, who’s a real SOB. Hall has a knack for playing characters like Robyn who are on the edge of a nervous breakdown.

The cinematography by Eduard Grau, editing bLuke Doolan and music byDanny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans heighten the sense of impending dread.

Hot Movie Takes – “Mudbound”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

After finally watching “Mudbound” on Netflix the other night, I was left somewhat underwhelmed. It’s a good film, mind you, but it’s a long way from anything revelatory. In no way does it break any new narrative or thematic ground and while its direction, production values and performances are very solid, they’re not anything special. I will say that “Mudbound” may compact more Southern Gothic dysfunction and racism into a single film than I’ve seen before, but I actually think that’s where this picture sort of lost me along the way. I thought the story tried taking too much on and would have been better served to focus on less and thereby derive more impact in the end. As it stands, the film does work as a sensitive, honest and harrowing evocation of the weird twinning that played out between white land owners and black tenants in the American South. The story is set in mid-20th century rural Mississippi – from just before the start of World War Ii to just after its conclusion.

The best narrative device about “Mudbound” is its parallel depiction of a black family and a while family bound to each other and the land by circumstance and custom. The Jacksons are black tenant farmers or sharecroppers who’ve worked the land for generations but have never been land owners and thus have little to show for their blood, sweat and tears. Given the exigencies of the Jim Crow South, the Jacksons lead a subsistence life and are saving every penny just so they can one day get a place and a plot of their own. Until that happens, they work at the behest of white owners. Hap (Rob Morgan) is the proud patriarch. Florence (Mary J. Blige) is his devoted wife. And Ronsel (Jason Mitchell) is their headstrong oldest child. The McAllans are a white family who become the new owners of the land. For Henry (Jason Clarke), it means he’s the boss whose requests he expects them to obey like orders. For his father Pappy (Jonathan Banks) it means they are the overseers of the Jacksons, whom he clearly regards as inferior and hates with every fiber of his being, and he treats them no better than slaves. For Henry’s progressive younger brother Jamie (Garrett Hedlund) and for Henry’s empathetic wife Laura (Carey Mulligan), the Jacksons are not less-than servants but fellow humans struggling to provide for themselves the same as they are. The dramatic core of the story unfolds when Ronsel enlists in the Army and goes off to serve in the tank corps under Patton in the fight to free Europe. Meanwhile, his father suffers a fall back home that puts him out of commission and forces Florence to work the fields and to help Laura with childcare and domestic duties. In keeping with the parallel stories, Jamie becomes a B-25 bomber pilot in the war while Henry and Laura grow apart and their farm undergoes hard times. Having fought for his country and seen the world, Ronsel returns an emboldened young man unwilling to accept Jim Crow. Having endured his own shattering combat trauma, Jamie returns a broken man unable to adjust to civilian life. The two returned war veterans strike up an unlikely friendship that ultimately nearly gets them both killed.

if there is a message behind the film, it’s that racism is a poison that damages everyone infected by it and that sometimes the only way to move forward is to move on and break the shackles of convention. The movie shows that some people will be forever stuck in their misguided beliefs and narrow life horizons and others will escape and break free from the muck and mire. But there is a price to pay either way. In the end, we’re all brothers and sisters under the skin bound by circumstances, some of which are beyond our control. It’s what we choose to do and in some cases what fate allows that determines our destinies and legacies.

In adapting the Hilary Jordan novel by the same title, writer-director Dee Rees and co-writer Virgil Williams have honed a powerful work that, again, could have been even more powerful with a sharper focus. I actually think the naturalistic yet heightened look that cinematographer Rachel Morrison achieved with the hardscrabble Mississippi scenes may be the single best element of the film. The brief but important scenes overseas come off (for my sensibilities anyway) as asides or throwaways, which I believe diminish their impact. Better to have not had them there at all than to have given them less gravity than the stateside scenes.

The best performance in the bunch is by Morgan as Hap, followed closely by Mulligan as Laura, Mitchell as Ronsel and Clarke as Henry. Blige is sturdy as Florence but I think her minimalist approach might have detracted rather than added to her character. Banks is appropriately evil as Pappy but his pathological racism seems out of proportion to how his own two sons relate to blacks. Henry is a racist for sure but he’s nothing like his father. Jamie comes to despises his father and what he represents enough to commit patricide.

I think “Mudbound” is an important addition to the pantheon of race films. Depending on your point of view, it may or may not measure up to, say, “Intruder in the Dust,” “Nothing But a Man,'” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?,” “Killer of Sheep,” “To Sleep with Anger,” “Do the Right Thing,” “Monster’s Ball,” “Crash”(2004), “12 Years a Slave” and “Free State of Jones” but it certainly goes to some dark, deep places and for that it must be commended.

Hot Movie Takes – “Up in the Air”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

In our ever expanding universe of catching up with good movies we missed upon their original release, Pam and I thoroughly enjoyed 2009’s “Up in the Air” the other night on Netflix. This film by writer-director Jason Reitman plays a lot like an Alexander Payne film. Indeed, Reitman shares a very similar satiric, yet sweet sensibility with Payne. Their respective work shares a lot in common in terms of the way they frame characters and situations, use music and show places. They even utilize some of the same creative collaborators. Here, George Clooney delivers a deeply felt performance as protagonist Ryan Bingham, who is the star handler for a fictitious Omaha-based company that other companies hire to implement their downsizings. He spends two-thirds of every year flying to other cities to do the dirty work of telling people they’re fired. In turns out there’s a real art to it and he’s the best at it. it helps that he doesn’t get emotionally involved – with anyone – and never makes it personal. Yet, he does show great sensitivity for and insight into the people he’s letting go by giving them the breathing space to exit with some dignity and hope as well as a portable philosophy for turning this trauma into opportunity.

Then something strange happens to him as he finds himself emotionally involved with four women. One is a new colleague, the anal Natalie (Anna Kendrick), a fresh out of college climber whose idea to replace in-person firing with virtual-firing and her utter lack of understanding of what her company and its star performer actually does angers Bingham. When their boss Craig (Jason Bateman) suggests she hit the road with Bingham to learn the ropes, Bingham initially resists having her tag along. But he eventually sees the benefit of having her experience up close and personal how delicate and complex the work is. He also begins to see that beneath her cold, hard exterior is a naive, insecure girl in desperate need of affirmation and affection. Meanwhile. Bingham has started up a casual relationship with fellow frequent air business traveler Alex (Vera Farmiga). After seeing her a few times he really falls for her, only he miscalculates what his heart and head are telling him and misreads the signals she’s giving off. He then heads home to attend his little sister’s wedding. This prodigal son and brother has been estranged and largely absent from the family. Reuniting with his sisters is strained and awkward. They love him but also resent him for his fast, free and loose lifestyle that only rarely finds him visiting, only to swoop right back out of their lives again. But fate gives him the chance to do a graceful thing for his sisters and he comes through. Then, when things go wrong with him and Alex and when Natalie abruptly quits her job after a downsized employee does something drastic, Bingham gets two more chances to do the right thing and he once again steps up to deliver.

Bingham’s also made a name for himself as a motivational speaker whose branded message is all about living a fluid, on-the-go, backpack life without attachments. But when the very things and persons he’s become attached to abandon him, he’s left rootless and vulnerable – his only “home” the airports, planes and hotels he frequents. Its a devastating statement about the price of disconnection and isolation and to his credit Clooney honors, never sends up or makes maudlin his character’s fragile, conflicted feelings. The best line in the film comes when Bingham has finally hit the coveted super exclusive ten million miles club on the airline he prefers and he gets to have a one-on-one chat with the pilot while in mid-air. The pilot, played by Sam Elliott, asks Bingham where he’s from and he fumbles for a second before answering, “I’m from here,” which is to say he’s an air bum or gypsy whose only home is this transitory conveyance 35,000 feet up in the air.

All the other players are equally effective, especially Farmiga as Alex. She and Clooney have a real chemistry together. Kendrick is very good as Natalie, who is unsympathetic most of the way through, but she makes us feel sorry for the real mess that Natalie is beneath her confident exterior. Playing against type, Bateman makes a fine cynical boss more concerned about numbers than people. JK Smmons has a scene-stealing turn as an axed employee who finds redemption with the help of Bingham’s informed perspective.

In many ways, this is a very sad film about the cost of people not making real human connections with each other and a sober reminder that even when they do there’s the risk of getting hurt. Putting yourself and your feelings out there always invites the possibility of rejection and disappointment. A poet said, “Tis better to have loved and lost, than never to have loved at all.” The movie seems to agree with that sentiment but to also ask if it’s true for everyone. Whatever lifestyle one chooses, marriage, commitment and family or single and free-agent, no one escapes unscathed. Infidelity, abandonment and loneliness are not exclusive to one lifestyle or the other. In the end, it’s whatever you make of things that counts.

“Up in the Air” shot for a couple days in Omaha at the Eppley Airfield passenger terminal and in the Old Market. Soon thereafter Clooney worked with Nebraska’s own Alexander Payne on the filmmaker’s under-appreciated “The Descendants,” which I think is an even better film than this, only it was made far away from the Midwest in Hawaii. With those Omaha connections intact, I’m still waiting for Payne to bring Clooney here for a Film Streams Feature Event at the Holland.

Hot Movie Takes – “Grace of Monaco”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Pam and I keep finding films on Netflix that are much better than the critical consensus would have you believe, The most recent of these is “Grace of Monaco,” an exquisitely rendered 2014 picture that dramatically interprets a critical juncture in the experience of former Hollywood star Grace Kelly in the fairy tale new life she assumed as Princess Grace-Serene Highness of Monaco. This international production took great pains to get the locations just right and to strike just the right aesthetic look and feel for its early 1960s setting amid the Euro rich and famous. The story quite rightly emphasizes that in marrying Prince Rainier, Kelly undertook the most demanding role of her lifetime. Her social breeding, grace, charm, high ambition and thespian skills gave her some unique advantages in pulling off this audacious change of status from Hollywood royalty to real life royalty. But there was nothing to prepare her for the Machiavellian rivalries, political inner workings, intense scrutiny and withering pressure that came with the title and the responsibility of being the wife of a monarch, the mother to his heir and the symbol for a nation.

I am not a royal-phile and I’m not even that fond of Kelly’s body of work as an actress, but I found this a compelling take on the personal journey of a very famous and somewhat naive woman getting in over her head, being very unhappy and then rising to the occasion to become a princess in more than name and image only.

Nicole Kidman is superb as Kelly. Except for a key speech she gives near the end, she never really tries to imitate the actress but rather, wisely, elects to express her essence, and clearly Kelly possessed enormous strength of will. Only an extraordinary woman could have done what Kelly did within full view of the world. It took real guile and guts. The supporting cast is excellent as well: Tim Roth as the cunning, rather cold-blooded Rainier, desperate to save his empire, Frank Langella as the confidante priest, Tuck, Parker Posey as the stern secretary Madge, and Derek Jacobi as the Professor Higgins-like Count.

Olivier Dahan brings Arash Amel’s script to life, though apparently Amel was upset with is meddling and interpretation of the screenplay. The Weinstein Company also apparently didn’t entirely like what Duhan did and released a version of the film that was cut against his wishes. Nevertheless, the film I saw stands on its own as engrossing, entertaining drama.

Hot Movie Takes – “Where the Heart Is”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

John Boorman has directed some of the most visually stunning narrative feature films ever made:

Point Blank

Hell in the Pacific

Deliverance

Zardoz

Exorcist II: The Heretic

Excalibur

The Emerald Forest

Hope and Glory

He often chooses provocative dramatic storylines to go along with those sumptuous, sometimes surreal visuals. At its best, his work is sensual, revelatory and moving. At its worst, naive and awkward. One of his least known and rarest seen pictures is among his greatest – “Where the Heart Is” (1990) Unusual for Boorman, it’s a social satire. It manages to combine the anarchic spirit and innate goodness of a Frank Capra screwball comedy with the issues-laden gravity and explicit criticism of an Oliver Stone treatise. All that is wrapped in a Coen Brothers and Pedro Almodovar package to create this totally original vision of American capitalism on the skids and the enduring salvation of the family when all else fails. The story centers around the McBains, a privileged contemporary New York City family who get a rude comeuppance that actually saves them in the end.

Family patriarch Stewart McBain (Dabney Coleman) is a self-made man who owns his own highly successful demolition and development company that’s publicly traded on the stock market. He represents the American preponderance for tearing down the old and building up the new – history and aesthetics be damned. His wife Jean (Joanna Cassidy) is a shallow consumer too preoccupied with her city brownstone and country estate to appreciate the merry-go-round her husband is on. The couple’s spoiled young adult children have it too good at home to leave. Chloe (Suzy Amis) is an aspiring visual artist. Daphne is a certified free spirit without an ounce of practicality in her bones. Jimmy (David Hewlett) is a sweet young man obsessed with computer video games and intent on getting laid. When Papa McBain is thwarted in his effort to build a skyscraper by preservationists who save an old building on the proposed site from being razed, he devises a plan to force his lazy, leeching children out of the house by staking them to live in the building. When their front money is exhausted, they’ll have to find ways to make it on their own. Maybe even get jobs. This tough love tactic freaks them out. But little by little the three misfits make the cavernous wreck into a creative studio and salon. They recruit four more lost souls into their space: fashion designer diva-in-the-making Lionel (Crispin Glover), who secretly pines for Chloe; down and out ex-magician Shitty (Christopher Plummer), who brings a grit and grace to the house; crass stockbroker Tom (Dylan Walsh), who thinks he wants Chloe but ultimately falls for Daphne; and ditzy but earnest spiritual seeker Sheryl (Sheila Kelley).

Between Chloe’s elaborate painted backgrounds and having her siblings and friends pose as body paint models, Jimmy’s cyber video game obsession. Lionel’s emerging fashion designs, Shitty’s enigmatic sayings and magical tricks and Sheryl’s communing with spirits, the house is A Midsummer Night Dream idyll.

Meanwhile, things go haywire for the father’s business and overnight his over-leveraged and exposed company collapses. His anal associate Harry (Maury Chaykin) grows desperate and angry. His snarky banker Hamilton (Ken Pogue) circles like a shark smelling blood. Stewart and Jean are devastated and left with nothing. Homeless, they have no other option but to move in with their kids, who were counting on Chloe’s calendar project and Lionel’s first collection to put them all on easy street. With no one else to turn to, this extended family turns to each other and they all band together to finish Chloe’s and Lionel’s projects by variously posing and sewing. Then this tribe suffers another reversal of fortune when they get evicted and the building is boarded up. That’s when Stewart puts his demo expertise to use and reaps the assets they need to show Lionel’s collection to big buyers, who naturally are agog about his work.

The only film I can compare this to is Wes Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums” but this is more a cutting edge cautionary about the perils of greed and more of a sweet valentine to the enduring power of family and love. The entire cast is strong but special shouts out go to Coleman, who portrays a wide dramatic-comedic arc from mendacity to hysteria to vulnerability, and to Plummer, who is almost unrecognizable because of the extreme look and voice he chose for his enigmatic character. Boorman’s incisive eye found a playground of rich images to fill the screen with – from NYC excess to detritus and from corporate calculations to artistic expressions. He and his late daughter Telsche Boorman co-wrote this wonderfully whimsical film.

NOTE: Don’t confuse this 1990 gem with a 2000 film by the same title.

The Big Brothers who police the Web are increasingly taking down uploads of things like this movie, so all I can say is search for it on YouTube and hope that it’s still there. If it is, watch it while you still can.

https://www.vidimovie.com/movies/film/where-the-heart-is-1990

Hot Movie Takes – “Rising Son”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

It continues to amaze me the quality films one can find uploaded on YouTube for free and in full. Just watched a 1990 cable movie that marked Matt Damon’s screen debut – “Rising Son” – which stars Brian Dennehy as a Willy Loman-like father who makes life hell for his two sons because he can’t let go of dreams he has for them that they don’t have for themselves. Dennehy has the right intimidating physical frame and emotional gravitas to bring his gruff character of Gus to life. Gus is a middle-aged workingman World War Ii combat vet in charge of production at an automobile parts manufacturing plant on its way out in the Rust Belt of early 1980s America. Damon is his younger son Charlie, who’s come back to town after dropping out of pre-med at Penn State. He’s questioning what he wants to do with his life. Only he can’t bring himself to tell his father that he wants no part of his father’s dream for him to be a doctor. That’s because Gus doesn’t like anyone bucking him or telling him he’s wrong. Gus has created a false narrative about himself and his family that he refuses to acknowledge is a cover for his own sense of failure and guilt. Knowing he can’t live up to what people have come to believe about him, Gus has forced his sons to pursue studies and careers they don’t care anything about. His oldest son, Des, hates him for it. Charlie resents him for it.

Damon is very good as the troubled coming of age Charlie. The actor obviously had star quality written all over him. It’s an impressive debut by any measure. The depth of talent in the cast is also impressive. Jane Adams co-stars as Charlie’s empathetic girlfriend from college, Piper Laurie plays his long-suffering mother, Richard Jenkins is the weak former owner of the plant who’s sold-out, Ving Rhames is a principled foreman and union rep at the plant and Graham Beckel is a hot-headed production floor manager who most keenly feels the sting and betrayal of the factory’s closing.

One issue I have with the film is that it has trouble fixing on whose story is paramount in the proceedings. Is it the father’s? The son’s? The workers? Or the dying town’s? They’re all equally compelling stories and they’re all dealt with to one extent or another. I also laud the writer (Bill Phillips) and director (John David Coles) for taking on such richly textured material and exploring these different layers of social-cultural-familial conflicts and issues. It all works well together but I just thought that things might have worked even better had one of these themes been developed more. To be fair, in the end, it’s the family-son dynamic that comes most into focus. And aside from Gus having a change of heart and head at the end that seemed a bit too sudden to be fully believed, this is a superior TV movie that would play very well in theaters. The performances are that strong and supporting them is evocative cinematography by Sandi Sissel, production design by Dan Leigh and set decoration by Leslie Rollins. The creators really captured the grit and grime and desolation of the town.

Though Dennehy has won a Golden Globe and other awards, he’s somehow never won an Emmy or Oscar, and this has to be one of the worst oversights in the annals of screen acting. This powerhouse actor certainly deserved recognition for his performance in “Rising Son.”

https://movienightseries.com/movies/id/726622/Rising-Son-1990.pl

Hot Movie Takes – “The Hurt Locker”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Until watching it on Netflix the other night, it had been a decade since I last saw “The Hurt Locker,” the acclaimed 2008 dramatic war film directed by Kathryn Bigelow. Her helming of the film made her the first woman to win the Academy Award for Best Direction. She remains the only woman to receive Oscar recognition in that category. The film had the same effect on me this time that it did ten years ago with its intense, spare, unrelenting portrayal of the work done by a U.S. explosive ordinance disposal team in Iraq. Jeremy Renner is superb as James, an ex-Army Ranger who replaces the team’s previous leader, Matthew (Guy Pearce) who’s killed by an IED (improvised explosive device). On James’ very first mission with his new team, he proceeds to challenge the way the veteran members, Sanborn, played by Anthony Mackie, and Owen, played by Brian Garaghty, are used to operating out in the field. Where they act with caution. preferring whenever possible to let the engineers and Rangers deal with hairy situations, James wades right in by himself with cover from his teammates. Sanborn and Owen regard James as reckless for exposing himself and them to unnecessary risks. Indeed, James has an unhealthy need for the adrenalin fix that comes with intentionally walking into harm’s way in order to uncover and defuse bombs that can rip his body to shreds. All he has between himself and oblivion is a bomb suit that can only provide a measure of protection and won’t save him if a device goes off in his hands. What compels him to endanger himself time after time?

The film’s writer, Mark Boal, was a journalist embedded with U.S. troops in Iraq, where he even spent time with a bomb disposal unit. These experiences led him to write a magazine story that he later adapted into the original screenplay for “The Hurt Locker’ that Bigelow directed. He earlier wrote the screenplay for another military drama, “In the Valley of Elah,” also based on reporting he did. “Valley” was directed by Paul Haggis. Boal later went on to write and produce “Zero Dark Thirty” and to script “Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare” Bigelow directed “Zero” and she also directed Boal’s script for her latest feature, “Detroit,” making her and Boal one of Hollywood’s top collaborative teams.

What makes “Hurt Locker” so effective is that it almost never leaves the high stress trauma at the core of the story. In the characters of James, Sanborn and Owen we see three very different yet related responses to repeated exposure to life and death situations. No one comes out of that experience unscathed. The bomb suit that Renner dons becomes a symbol for the armor – both literal and figurative – that combat troops wear to guard against physical and emotional injury. It can only ward off so much hurt though. What it can’t deflect, soldiers internalize. Bigelow and Boal keep the focus intimately trained on this personal radius of pain. Even when the men leave the strict confines of their assignment, they encounter only more pain. By nature or nurture, James has the ability to detach from the hurt and horror, but he’s only human and bound to break.

The cinematography by Barry Ackroyd and the editing by Chris Innis and Bob Murawski serve to heighten our immersion in the shit and the tension that comes with it. This movie helped establish new standards in realism for the depiction of warfare. Intense, urgent, graphic. The close confines of soldiers under extreme duress and eminent danger create a visceral experience for us watching helplessly on. But to Bigelow’s credit, she doesn’t go over the top, with the possible exception of a body bomb surgically implanted in a boy that our protagonist feels compelled to remove. Believing he knows the boy who died from the butchery that placed the explosive inside him, James seeks vengeance against those responsible. In this instance and in others, the story reveals how lines get crossed when emotions and prejudices take hold, making it even harder than it already is to tell foe from friend, combatant from civilian, ugly American from war criminal.

Hot Movie Takes – “Aguirre, the Wrath of God”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Werner Herzog’s films insert you into hypnotic worlds of obsession that elicit visceral responses to the dark, disturbing, hallucinatory images you can’t stop watching. A good example is one of his early masterpieces, “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” (1972), which amazingly is available in a superb upload on YouTube. This is one of those essential movies for understanding just how extreme filmmakers and their companies of cast and crew can go in order to create indelible experiences that defy logic in pursuit of capturing art and truth.

Here, he went to extraordinary lengths in visualizing the misadventures of a group of Spanish conquistadores inin search of the legendary city of gold, El Dorado. After months of preproduction work and scouting, Herzog brought his entire cast and crew into the Peruvian rainforest of Machu Picchu and the Amazon River tributaries of the Ucayali region for an arduous and hazardous five-weeks shoot. The cautionary story reminds one of the 1948 John Huston classic “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” and anticipates Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” for its jaundiced look at men destroying themselves in the reckless pursuit of wealth and power. At the core of each story is a madman hellbent on exploiting the natural landscape and its indigenous peoples regardless of the costs.

Herzog used a combination German, Spanish and South American cast who lend great authenticity to the story. The late Klaus Kinski portrayed the demented warrior title character, Lope de Aguirre, who hijacks the expedition when the journey begins to look lost and its leader orders they turn back. Aguirre has the party’s commander, Don Pedro de Ursua, shot and shackled and he encourages nobleman Don Fernando de Guzman to claim the title of emperor over this uncharted land. The deeper the expedition journeys into the forest and down the river, the more threats and dangers materialize and one by one the members fall from illness, execution, attacks by Indians until Aguirre, who by then is completely lost in his delusions of grandeur, is left alone, only with monkeys as his subjects.

The visual storytelling is spellbinding and haunting. It’s a work of pure cinema that relies little on words and instead shows how the overwhelming forces of nature dominate man’s folly in the attempt to play God. Kinski is as usual a magnetic, maniacal dynamo and even though not all the performances by the other actors are as strong as they might be they are naturalistic and thus help anchor the film in reality even as the story grows ever more bizarre. Herzog and Kinski enjoyed one of the great if troubled collaborative teamings in film history. As extreme as “Aguirre” was to realize, they outdid themselves on the subsequent “Fitzcarraldo” about a rubber baron who had a steamship hauled across mountainous Peruvian jungle. Herzog being Herzog, he recreated this epic, herculean effort without benefit of any special effects.

Herzog is a fearless, some say reckless and manipulative artist who puts himself and others at great risk in making his films. His methodologies may be suspect but it’s hard to argue with the results. Whatever you may think of what he puts up on the screen and how he managed to achieve it, you won’t be able to get the images he captures out of your mind.

Hot Movie Takes – “44 Minutes: The North Hollywood Shootout”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

As a sheer act of anarchy, the 1997 North Hollywood shootout ranks right up there with real-life modern urban American nightmares. Two bank robbers swathed in body armor brazenly, wantonly fired their arsenal of fully automatic weapons at dozens of citizens and L.A. police officers in what turned out to be a 44 minute ordeal. Much of it was captured on camera by a helicopter news team and other journalists on the scene. This was before cell phone cameras were around or else the video documenting the horrific event would have been exponentially greater. Enough footage was shot to give the makers of this dramatic interpretation of the incident a play by play blueprint for recreating the chaos and carnage that, miraculously, only resulted in the deaths of the two perpetrators. This made for Fox television movie is not great but it’s actually a quite ambitious and impressive take on what went down in broad daylight that winter day inside and outside the Bank of America branch the armed robbers chose at random.

The movie takes us inside the lives and routines of some key participants, including a veteran cop and his trainee, a male-female patrol team, a detective, a SWAT officer, a bank manager and assistant and the two bad guys.The best thing the movie does is capture the surreal experience of what starts out as a normalday turning chaotic in an instant and no one being prepared for two maniacs taking on a small army of law enforcement officers and willfully shooting to kill anyone standing in their way. This sudden, unpredictable fury erupted in full view of nearby business owners, residents, shoppers, bystanders and passerby, Anyone caught at the scene in this storm of gunfire became engaged in the horror and danger because that’s just how out of control it became. No one in the vicinity was safe. Everyone was a potential target and casualty.

I recall feeling sickened and angered watching the event play out on camera because here were two guys armed to the teeth standing off and dominating a much larger but woefully ill-equipped professional police presence. In the end, the police did take them out, but for a long time it appeared as if the gunmen had the upper hand and that nothing short of a military strike force would do. As crazy as that sounds, a military option would have been necessary had the gunmen used or commandeered an armored vehicle for their attempted escape. I mean, I gotta believe that nothing short of a tank blast or a rocket propelled grenade would have stopped them. Again, this was way before drones were around. Anyway, I got the same feelings all over again watching the dramatization, but at least this time I knew how it was going to end.

Director Yves Simoneau, writer Tim Metcalfe, cinematographer David Franco and editor William B. Stich deserve props for creating a taut thriller. The actors playing the lead cops responding to the incident all do a good job of making us feel what it was like to be there during that frightening and chaotic firefight. Michael Madsen portrays Detective Frank McGregor, a fictitious character who’s an amalgam of real life officers, while Ron Livingston plays SWAT officer Donnie Anderson and Ray Baker, Douglas Spain and Mario Van Peebles also play characters drawn from an amalgam of real-life officers.

The movie is available (or was) in full and for free in an excellent YouTube upload.

Hot Movie Takes – “The Pistol: The Birth of a Legend”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

As a sports movie connoisseur, I was surprised that I had never heard of a 1991 drama about the early life of the late great basketball legend “Pistol” Pete Maravich. I found the film on YouTube in a decent upload and decided to give it a look. I found it to be a well-made but by no means classic sports film. The thing that makes it worth watching is that the story centers entirely on one key year in Maravich’s childhood, when his passion for the game could no longer be contained and he showcased for the first time his talents on a stage bigger than the local playground or his driveway. at home Thus, it focuses on the birth of his legend and the incalculable drive and work he put into becoming the greatest showman the game’s ever seen. The tale takes place in 1959-1960 South Carolina, where Maravich, then 13, was already an eight year disciple of the holy hard-court gospel of his father Press, who coached the Clemson University team at the time. His dream to be the best player in the world took hold then and he wouldn’t let it go for almost 20 years, until his body and mind couldn’t take the pressure anymore.

The boy cast as the young Pistol, Adam Guier, actually learned many of the demanding training regimens Maravich dedicated himself to under the tutelage of his father and mastered some of the precocious skills that made the Pistol such a sensation, including behind the back, through the legs and no-look passes and acrobatic shotsHaving the actor portraying young Pete perform those passes and shots adds a layer of realism that’s hard to beat even if the basketball sequences aren’t always staged at the pace and with the physicality or urgency needed to really sell the action. There’s also a crucial hoops sequence near the very end that falls way short of what it could have been due to some lazy editing. But what this movie really hangs on and does a great job of is telling the story of a father and son. Press and Pete were both obsessed with changing the sport from its tired old conventions into something new and dynamic. Nick Benedict is very good as Press – a hard, disciplined man with a soft heart who used his son to live out his own unrealized dreams and to prove his unpopular concepts. Guier never acted before this and he brings a nice naturalism to the part as the hero worshiping son devoted to fulfilling this father’s expectations of him. Millie Perkins is fine as the exasperated mother-wife who worries that Pistol is too consumed with hoops for his own good. Boots Garland is a hoot as the crusty high school coach who reluctantly accepts the 5-2, 90-pound eighth grader named Peter onto his varsity basketball team knowing that he has a once in a lifetime talent on his roster but he’s too afraid and stubborn to play him the first several games of the season because he represents a threat to everything he holds dear about the sport.

An important theme in the movie is to embrace being different even though it may cause you angst. Maravich received a lot of push back for his revolutionary style of play and he paid a price for it. No one had seen anyone outside the Harlem Globetrotters, and certainly no white player, style on the court the way he did. In college, where his father insisted he play for him at Louisiana State University and encouraged him to take upwards of 40 shots a game, Pete became the NCAA’s all-time leading scorer alright but there were times when his self-absorbed play had little to do with the team and more to do with him. From a purist’s standpoint, he should have had much higher assist totals than he did given his knack for seeing the floor and ability to draw defenders and to deliver the ball to teammates. He should have made more simple, fundamentally sound plays and tried fewer creative stunts in pursuit of wins over thrills. Those same showboat tendencies did not translate well with teammates and coaches in the NBA until he learned to adapt his game to the greater good. Not long after he became a complete team player though his body started giving out. Before physically, mentally and emotionally burning out from his candle burning at both ends way of life, he did establish himself as one of the league’s 50 greatest players of all time. None of this is shown in the movie, which stops at the conclusion of that pivotal year in his youth, but it is what happened and then, after abusing alcohol and drugs, losing his mother to suicide and retiring from the game adrift and angry, he found Christ and he devoted his life to his faith and family. He cared for his ailing father, who died in his arms. Pete, who by the end of his life found great peace and a bigger purpose, died far too young at age 40, suffering a massive heart attack after a pickup basketball game. There are documentaries on YouTube that detail all that befell him after his youth. the transformation he made and the tragic death that took him too soon. The docs serve as strong complements to the dramatic movie.

Props to director Frank C. Schröder and writer Darrel Campbell for working from Maravich’s autobiography and creating a good family film that deserves to be more widely seen and known. Pete, who died 30 years ago this coming summer, did not live to participate in the making of the project, but I have to think that he and his wife and children are proud of the portrayal. Though he died in 1988, he lives on in the way the game is played today. He was a true pioneer who opened the sport up to a creative, expressive style that permeates every level of hoops. This movie reveals the origins of his legend while helping continue to burnish it.

https://www.pistol-pete-videos.com/product/the-pistol-the…

Hot Movie Takes – “Our Souls at Night”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

The much talked about re-teaming of Robert Redford and Jane Fonda for the 2017 Netflix original film “Our Souls at Night” is mostly deserving of the acclaim and attention it’s receiving. This is a sweet, understated, contemporary adult romantic drama about two widowed octogenarians in a small Colorado town who start up a friendship in their 80s that grows in intimacy and survives life interruptions. These seasoned actors have a good if not great chemistry together but what really makes their union work in this film is how minimalistic they are at this stage of their careers. Each has always underplayed things and with age and experience they’ve become even sparer and more simple and that translates into a pleasing naturalism they wear with ease and grace. It helps, too, that they’re both icons whose bodies of work inform whatever they do. They’ve part of our collective consciousness and we have grown up and with or grown old with them.

The hook of this story has Fonda’s character Addie show up at the home of her neighbor Louis Waters (Redford) one day with a seemingly audacious proposal: that they sleep together. Not for sex – but for companionship. Share a bed and some conversation in in order to help each other get through the night. He asks if he can think it over and, of course, upon reflection this seemingly provocative idea is actually quite pragmatic and he agrees to give it a try. I mean, who wouldn’t, if the fellow senior citizen asking you were Jane Fonda? She looks better and fitter than most 50 and 60 year olds. Not that it’s all about physical attraction. Their characters have mutual regard for each other, even though they really never knew each other. But it’s easy to believe they would find the notion attractive and stand a good chance of partnering or pairing well together. After an awkward first few nights, their shared need for genuine human connection can’t be bought or faked or ignored. Neither can the spark of feelings for each other. Their arrangement finds them engaging each other with more and more tenderness, vulnerability, transparency, honesty, desire, affection and compassion.

Both Addie and Louis are scarred by past traumas. She lost a son when he was hit by a car and afterwards her relationship with her other son and with her husband were never the same. Louis briefly abandoned his wife and child for another woman and when he went back toresume his life with his family, he found something irreparably broken. Both Addie and Louis have survived their spouses and after years living alone have hit upon this sleepover arrangement.

Then things get complicated when Addie’s 7 year old grandson comes to live with her. She and Louis have a great time giving the boy what his father won’t or can’t emotionally provide him. But Addie’s son resents Louis in her and his boy’s life. He regards Louis as an intruder imposing himself into the family and he purposely tries driving a wedge between them. In keeping with the film’s tone, no blowups happen. It’s a film about deep interior spaces and implosions, not explosions.

Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber adapted the novel the film is based on and Ritesh Natra directed their screenplay with the sensitivity to match their subtlety. The ending may not be the satisfying feel-good some expect or want but it once again works in step with everything that precedes it.

Hot Movie Takes – “Poolhall Junkies”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

While no great shakes of a film, “Poolhall Junkies” (2002) is a very entertaining diversion with some nice performances by star-writer-director Mars Callahan and supporting heavyweights Chaz Palminteri, Christopher Walken and Rod Steiger. Rick Shroder is also good in a supporting role. There aren’t that many films where billiards is the main storyline and this one certainly falls short of the two most famous pool hall flicks, “The Hustler” and “The Color of Money.” But it’s not nearly the misfire than the aggregator review scores you find online lead you to believe and it should have done much better at the box office than the $500,000 it earned in a limited release. The considerable presence alone of Palminteri, Walken and Steiger should have draw in audiences. But for whatever reasons, the film didn’t register, though it has earned something of a cult following since it died at theaters. With a more charismatic lead, a sharper script and better direction, this film could have really been something, but even as is it’s pretty damn good.

Callahan was apparently a pool hustler growing up, as was co-writer Chris Corso, so the film is very well informed about that subculture. He plays Johnny, who’s been groomed from childhood on to be a hustler by Joe (Palminteri), his low life, bad news handler. Comes the day when Johnny, now all grown up and tired of marching to Joe’s orders, finally breaks with him. Johnny actually sets him up to take a beating from some thugs and you just know there’s going to be hell to pay for that some day. Johnny’s girlfriend (played by Allison Eastwood) is an upper crust law student who disapproves of his hustling ways. He tries going straight and leaving the stick behind but the pull is too great. His younger brother and the gang down at the pool hall allidolize him. Even though he hungers to get back in the game, he can’t fully commit himself again – at first. The pool hall’s proprietor, Nick (Steiger) tells him that being the best pool player in the world is his destiny and he needs to go after it. Meanwhile, he meets Uncle Mike, a rich guy who appreciates Johnny’s talent. When Joe comes back looking to settle the score with his stickman in tow (Schroder) and Johnny no where to be seen, Johnny’s brother takes the challenge and gets messed up in the process. That’s when Johnny steps up to take down Joe and his pro with the help of Uncle Mike’s bankroll.

The characters and settings ring real. The acting is strong. But where the film loses its punch is its inability to balance its drama and humor. There seem to be two distinctly different films – one a drama and the other a comedy – vying or struggling for predominance here and Callahan couldn’t or wouldn’t decide which it should be. There’s nothing wrong with having it be both as long as each aspect complements the other, but in this case the drama jars with the comedy and the comedy undercuts the drama. And that’s a problem. The other problem is that Callahan seemed hell bent on mimicking the work of Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Spike Lee. His homages to them in storytelling, tone, energy, dialogue and even camera angles makes his film too obviously derivative.It’s actually a distraction.The other thing that makes it seem like we’ve seen all this before is that Callahan drew on just about every cliche and stereotype out there for this subject matter. Better that he and Corso had drawn on personal, specific anecdotes from their own experiences in that world than stock situations and characters we’ve seen before. Finally, Callahan has way too much business going on with minor characters who should have remained far more in the background.

What the film lacks in finesse and modulation, it almost makes up for in heart and color, it reminded me of two wildly different features – “Rounders” and “Boondock Saints” – about similar subcultures. The former is a slicker but not much better film. The latter is a rawer but not much better film. Both of those were commercial hits. This, as I indicated above, was an outright failure. Hard to understand how that’s possible, but i totally understand why “Poolhall Junkies” subsequently found its audience through rentals and streaming. It deserves to be seen. I think most people that watch it will enjoy it.

The triple threat Callahan is an intriguing cat. He’s not a great actor or writer or director, but he’s good enough at each that he gets your attention and keeps it. I read that he’s endured some serious health problems in recent years and that may help explain why we haven’t heard or seen much from him since this movie.

By the way, I think a better title for the film would have been “Poolshark Junkies.”

“Poolhall Junkies” is available in a good upload on YouTube. Check it out while it lasts.

https://www.movie-trailer.co.uk/trailers/2002/poolhall-junkies

Hot Movie Takes – “In Bruges”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

This British equivalent of “Pulp Fiction” is a deliriously funny and poignant 2008 dark comedy about two Irish assassins sent to Bruges, Belgium by their employer after the newbie of the pair fouls up a job back home. Brendan Gleeson is superb as the wise, veteran hit man, Ken, and Colin Farrell has never been better as his brash protege, Ray. Wonderfully sinister as their psychotic contractor Harry is Ralph Fiennes, whose call they nervously await.

Our oil and water protagonists have two weeks to kill in Bruges, where the laid-back Ken wants to take in the sights, soak up the history and make the most of being on the lam. High strung Ray wants to get out of Bruges as quickly as possible because he doesn’t appreciate any of its charms and is guilt-ridden over having accidentally killed a boy on the last job. Then Ray gets smitten with a local girl and he suddenly finds a reason to stay besides hanging around for the call Harry’s supposed to make. When Harry finally does call, he has an assignment – but it’s for only one of them. The rest of the movie finds the three men dancing with death.

The irreverent, sardonic tone of the film is perfectly embodied by Ken and Ray, who have a kind of father-son, big brother-little brother relationship. These two guys are hired killers but they love each other. Ken is forever trying to teach Ray a little culture and moderation and Ray is forever champing at the bit for action. Ken sees right through Ray’s bravado and impatience and realizes he has a sweet if rough around the edges man-child on his hands who’s not cut out to be a hit man. He also knows that Ray is haunted by what happened with the boy on the botched job. Meanwhile, Ray feels forever constrained and criticized by his too overly cautious mentor who, to his embarrassment and frustration, plays wet nurse to his childish antics.

Gleeson strikes just the right vibe as the smart, slightly world-weary sort who doesn’t like making waves or mistakes. The actor has a real solidity and honesty about him that fits his no bullshit character. Farrell brings the appropriate nervous energy, quick temper and mercurial personality to his brio-filled character. Where Ken is refined and restrained, Ray follows his street sense sensibilities. Both have a weird loyalty to the job, to their employer and to each other and it’s that last fidelity that gets tested in the end. Meanwhile, Fiennes throws himself into the role of the cunning and volatile Harry, who can’t let anything go. Writer-director Martin McDonagh has great fun with the personal codes these monsters live b. Even through all the carnage they engage in they’re always portrayed as charming if unredeemable blokes out on a romp whose closed circuit of mayhem must lead to their own mutually assured destruction. Thankfully, the fatalism is never bogged down by sentimentality. McDonagh has this trio intersect with the world the rest of us live in but no matter how much they try to be normal human beings, their violent, killing ways catch up to them, and they accept this as the price they pay.

I actually prefer this film to “Pulp Fiction” because as good as that film is this one doesn’t call attention to its dialogue, which is far more naturalistic, or to its visuals, which eschew style for clarity and tension – both comedic and dramatic.

The production values are very high for this great looking and sounding film made in Bruges and London. Cinematographer Eigl Bryld, production designer Michael Carlin, art director Chris Lowe, set decorator Anna Lynch-Robinson, editor Jon Gregory and composer Carter Burwell really create a verisimilitude of place that fills your senses.

“In Bruges” is available in full and for free in a pristine upload on YouTube. Catch it while it lasts.

Hot Movie Takes – “The Godfather”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

What I am about to say may be heresy or fighting words to some, but I always regarded “The Godfather” to be somewhat overrated and after seeing it again recently I feel even more convinced of it. This is a film that lives more on reputation than merits. Don’t get me wrong, this is a very good American film, just not a great one. If it is, you’d have to make an awfully strong case why, for example, it’s superior to the 1946 Bogart-Hawks classic “The Big Sleep” or the 1958 Orson Welles classic “Touch of Evil,” the first of which is narratively more imaginative and the second of which is visually more interesting and inventive. Certainly, “The Godfather” is not the masterpiece many make it out to be. Like a fair number of cineastes, I prefer the 1974 sequel, “The Godfather II,” to the 1972 movie. I think writer-director Francis Ford Coppola made two more superior films to boot – “The Conversation” and “Apocalypse Now.” Those are very original works that have little or no antecedent cinematically-speaking. “The Godfather,” on the other hand, doesn’t really break any new ground in the medium. Indeed, at its core it’s a pretty standard, even old-fashioned gangster film. Granted the film does transcend the genre through its focus on family and the somewhat epic scale of the story. The stellar cast sets it apart to a certain degree as well. There are other crime films with strong principals and supporting players who form a great ensemble only just not in the same quantity because “The Godfather” does have an unusual number of speaking parts by highly accomplished actors. But the script, cinematography, settings, productions design and direction in “The Godfather’ are nothing revelatory or even that special, even within the genre. I prefer some more ballsy crime films that came out in the same era as “The Godfather” but that didn’t get nearly the love and didn’t do nearly the business it did:

“The Friends of Eddie Coyle”

“Charley Varrick”

“Night Moves”

A film from that same time span that I also prefer butthat did score well with audiences and critics is:

“Chinatown”

For me, those four films have more texture and life than “The Godfather,” which seems rather slow and dull, even shallow, by comparison.

I also think more highly of several later crime films, including:

“Straight Time”

“The Long Good Friday”

“Thief”

“The Black Marble”

“True Confessions”

“Once Upon a Time in America”

“Goodfellas”

“One False Move”

“The Devil in a Blue Dress”

“A Simple Plan”

“Heat”

“The Departed”

The Limey”

As for earlier ones, I would put the following at least on par with if not ahead of “The Godfather”:

“The Roaring Twenties”

“The Big Sleep”

“Ride the Pink Horse”

“The Asphalt Jungle”

“White Heat”

“The Big Combo”

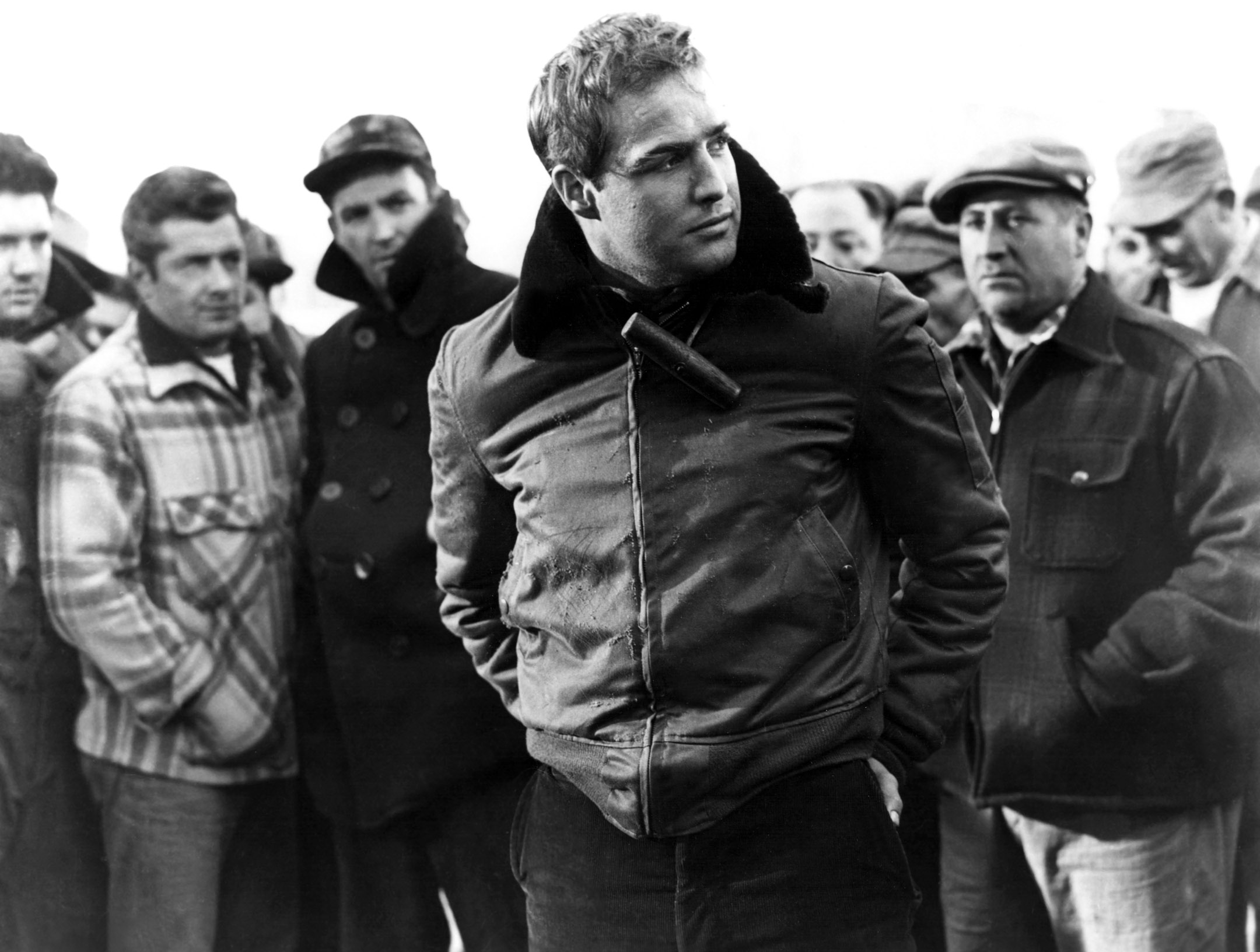

“On the Waterfront”

“Touch of Evil”

“Murder Inc.”

“Bonnie and Clyde”

In my opinion, a mythology has grown up around “The Godfather” and its meta-Method cast. As good as Brando, Pacino, Caan, Duvall, Cazale and Co. are, there are narrative holes in their characters and their back stories that no amount of acting talent can fill. Much of what they’re left to give and we’re left to receive is behavioral business that doesn’t really reveal a whole lot beyond surface things. Mind you, it’s compelling characterization, but there’s very little meat there. It’s largely body language and intonation. Exposition and deep insights, not so much. I mean, what really motivated Michael to break away from the family to go off to college and war in the first place? What made Fredo so weak? How is it that Tom got taken in as a surrogate brother into this secret society of an Italian mob family? And what made the Don the way he is? Well, starting with that last question, of course, the much richer sequel provides answers. This is why Coppola later re-edited the two films to combine them into a somewhat seamless epic that actually does make the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

At the risk of being guilty myself of the cult around the cast, “The Godfather” is at its best whenever Brando is on the screen. It’s not that he’s the only actor who could have played the character, but he is the only one who could have brought such dimension to Don Corleone. Good thing, too, because he didn’t have nearly as much to work with as Robert De Niro did portraying the young Don in “The Godfather II.”

I’ve personally always likened the mafia subculture depicted in “The Godfather” to an underground vampire society whose blood lust is the source of familial, generational and rival conflicts in which no one is spared. It is a dark, perverse universe animated by creatures of the night who steal the life and soul of everyone they encounter. The only escape is death.

Also, the women characters in “The Godfather” are stunningly, annoyingly weak. It would have been a far richer film if Coppola and Puzo had developed each female character more as fully realized human beings.

On a purely visceral level, “The Godfather” suffers in comparison to other quality crime films even of the same era. It is a victim of it’s own internal weight and slow pace, which four and a half decades ago seemed magisterial and grand, but today plays as plodding and ponderous. I would suggest that what Coppola attempted in “The Godfather” he mostly achieved in the melding of “Godfather I and II,” but those films were not released and seen as a unified whole until years later. I don’t mention “Godfather III” because it’s not worthy of discussion here. Sergio Leone actually managed to accomplish the epic gangster story in a single compelling film – the director’s cut or long version of his “Once Upon a Time in America,” whose narrative textures and tones are more finely calibrated and complex than those of “The Godfather.”

“The Godfather” is still a deeply satisfying work but I’m not prepared to automatically confer greatness on it just because that’s the popular, even critical assessment that’s grown up around it. Unlike, say, “Citizen Kane” or “The Best Years of Our Lives” or “It’s a Wonderful Life” or “Paths of Glory” or “To Kill a Mockingbird,” the film resonates far less, not more, over time, which is to say it seems much less special now than it did 46 years ago.

https://www.movie-trailer.co.uk/trailers/1972/the-godfatherß

Hot Movie Takes – “Control” (2004)

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

You never know where or when you’re going to find a new movie gem. Last night, it was via an excellent YouTube upload of the 2004 straight to video crime thriller “Control” starring Ray Liotta, Willem Dafoe and Michelle Rodriguez, which I found better than many a highly touted, big box office grossing picture of the same genre. It’s not great, mind you, but it will hold your attention right through to the end. Tim Hunter, a once hot feature director who’s mainly worked in television the last 25 years, directed this clever, gritty piece that melds crime thriller, science fiction and horror conventions into a real ride. The main reason to see this is the performance by Liotta. He channels the danger and rage of his “Something Wild” breakthrough to play sociopathic killer Lee Ray Oliver. Liotta went to some deep, dark place to find the savagery and brutality he portrays and it makes the film’s hook all the more powerful.

The hook is that pharmaceutical researcher Dr. Michael Copeland, played by Dafoe, has found a drug that specifically acts on brain chemistry to reduce aggression and ideally in humans will promote feelings of empathy and remorse. Up till now, the drug has only been tested in animals. An unholy deal is struck by the mega company Copeland works for, the warden where Lee Ray has been on death row and the local coroner to fake Oliver’s lethal injection execution and place him in a human test trial on the drug. Under secure, close observation, Lee Ray shows no signs of his violent tendencies decreasing, at first, but after a short time he begins to change, especially under greater dosage and it isn’t long before he’s put on supervised release to see how he handles life on the outside. This behavior modification through science scenario has been around a long time in fiction and so there’s nothing original here. and this film certainly doesn’t have the ambition of, say, “A Clockwork Orange.” But it does make the case that the stakes for all involved are extremely high. Should Lee Ray be discovered alive or revert back to his violent, homicidal ways, he’s a dead man because the company can’t afford to be exposed participating in this illegal experiment. The movie skirts lots of details and leaves too many questions unanswered and uses too many cliches to be fully satisfying on an intellectual level, but it still works.

Not surprisingly, Lee Ray’s violent past catches up with him. Soon on his trail is a Russian mob hit man sent to avenge the murder of the gang-leader’s son whom Le Ray killed while robbing a drug dealing outfit. Also stalking him is the brother of an innocent man left brain impaired by head shots inflicted by Lee Ray when fleeing the scene of the aforementioned incident. Meanwhile, Lee Ray starts to get involved with a woman (Rodriguez) he meets at his car wash job. As all this plays out, Copeland gets far more emotionally wrapped up than he should in Lee Ray’s transformation. He’s convinced that Lee Ray is living proof the drug works. His boss and the security detail assigned to monitor Lee Ray are less sure. The final third of the film finds Lee Ray pushing the boundaries of this second chance while fending off the two men hellbent on killing him. A late twist is revealed that debunks the effectiveness of the drug. By the end, Lee Ray is hunted by not only the revenge seekers but by the security agents now tasked with eliminating him and his only protection is Copeland, whose conflict of ego and responsibility, arrogance and remorse, is not unlike that of Dr. Frankenstein with the monster in the Mary Shelley classic.

The story is an kind of update on the 1968 film “Charly” in which a drug is found that makes a developmentally disabled man a genius. This is a better film than that. In “Control” Hunter has a good script to work with from Todd Slavkin and Darren Swimmer. The pair were the creative and producing talents behind the small screen series “Smallville.” Hunter is very familiar with the dark material of “Control” because it’s the same kind of territory he explored so well in the films that first brought him to the attention of the world (“Tex,” “River’s Edge,” “The Fort of Saint Washington”), though this is unusually violent material for him. He makes good use of a strong cast and interesting settings. The ending may not be to everyone’s tastes, but it works within the framework of the overall design.

Apparently, “Control” was an international production and perhaps for tax reasons the film was shot in Bulgaria, though the story is entirely set in America. I don’t know why this film never got a theatrical release because it had the star power, story hooks and production chops to become a box office success if given the chance. Anyway, the movie has been finding its audience ever since and it’s well worth your time if you’re looking for a fast-paced, thinking man’s thriller that still satisfies at the most visceral level.

https://www.traileraddict.com/control-2004/trailer

Hot Movie Takes – “50 Years Ago: Saluting 1968 Movies”

@By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

1968 wasn’t a great year for English-speaking films but there were just enough memorable pictures released that year to inspire this post. My personal Best of Year list for 1968 is limited to films from that year I’ve actually seen in their entirety. From a quick survey I did courtesy the Web, I think I’ve seen most of ’68s well-regarded pics with the exception of “The Thomas Crown Affair” and a few others.

This was one of the awkward transition years for the industry between the collapse of the old contract studio factory system and the emergence of the New Hollywood. Feature filmmaking was still in the hands of some old-time moguls but was quickly being taken over by brash new executives with college degrees, television hot shots and film school grada. A great mix of old and new talents made for a lively scene, though the emphasis was still heavy on tried and true genre projects. There were still lots of Westerns, crime pics, war movies and comedies being cranked out. Even though musicals were just about played out, the studios still produced some big ones. There were a few science fiction and horror entries, including some notable, groundbreaking ones. And there were some attempts at youth-counterculture stories. But the stripped down realism, humanism and risk taking that the 1970s would be known for had yet to hit the mainstream. It would be a few years yet, too, before the disaster and blockbuster movie trends would start. Nearly a decade would pass before a full slate of Vietnam War films would appear.