Archive

Cathy Hughes proves you can come home again

Cathy Hughes proves you can come home again

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the July 2018 issue of New Horizons

Nebraskans take pride in high achieving native sons and daughters, Some doers don’t live to see their accomplishments burnished in halls of history or celebrated by admirers. This past spring, however, Cathy Hughes, 71, personally accepted recognition in the place where her twin passions for communication and activism began, North Omaha.

The mogul’s media holdings include the Radio One and TV One networks.

During a May 16-19 homecoming filled with warm appreciation and sweet nostalgia, Urban One chair Hughes reunited with life-shaping persons and haunts. An entourage of friends and family accompanied Hughes, who lives in the Washington D.C. area where her billion dollar business empire’s based. Her son and business partner Alfred Liggins Jr., who was born in Omaha, basked in the heartfelt welcome.

Being back always stirs deep feelings.

“Every time I come I feel renewed,” Hughes said. “I feel the love, the kindred spirit I shared with classmates, friends, neighbors. I always leave feeling recharged.”

With part of Paxton Boulevard renamed after her, a day in her honor officially proclaimed in her hometown and the Omaha Press Club making her a Face on the Barroom Floor, this visit was extra special.

“It was so emotionally charged for me. It’s like hometown approval.”

During the street dedication ceremony at Fontenelle Park, surrounded by a who’s-who of North O, Hughes said, “I cannot put into words how important this is to me. This is the memory I will take to my grave. This is the day that will stand out. When you come home to your own and they say to you job well done, there’s nothing better than that.”

Photo Courtesy of Cathy Hughes

Cathy Hughes’ mother, Helen Jones Woods with the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, circa 1940

Welcoming home an icon

Good-natured ribbing flowed at the park and at the Press Club, where she was roasted.

The irony of the Press Club honor is that when Hughes was young blacks were unwelcome there except as waiters, bartenders and kitchen help. The idea of a street honoring a person of color then was unthinkable.

“This community has progressed,” Hughes told an overflow Empowerment Network audience at the downtown Hilton. “An empowerment conference with this many people never could have taken place in my childhood in Omaha. This is impressive.”

Empowerment Network founder-president Willie Barney introduced her by saying, “She is a pioneer. She is one of the best entrepreneurs in the world. She is a legend.”

Nebraska Heisman Trophy-winner Johnny Rodgers helped organize the weekend tribute for the legend.

“I think Cathy Hughes is the baddest girl on the planet,” Rodgers said. “She’s historical coming from Omaha all the way up to be this giant radio and TV mega producer and second richest black lady in the country. It’s just fantastic she’s a product of this black community. I want to make sure all the kids in our community realize they can be what Cathy’s done. Anything’s possible.

“I want hers to be a household name.”

Some felt the hometown honors long overdue. Everyone agreed they were well-deserved.

A promising start

People who grew up with her weren’t surprised when she left Omaha in 1972 as a single mother and realized her childhood dream of finding success in radio.

She had it all growing up – sharp intellect, good looks, gift for gab, disarming charm, burning ambition and aspirational parents. Her precocious ways made her popular and attracted suitors.

“She’s very personable,” lifelong friend Theresa Glass said. “She’s been a gifted communicator all the time. My grandmother Ora Glass was her godmother and she always believed Cathy was destined for great things.”

Radio veteran Edward L. “Buddy” King said, “She had this thing about her. Everybody projected she would be doing something real good. She knew how to carry herself. Cathy’s a beautiful woman. She’s smart, too.”

Glass recalled, “Cathy was always an excellent student. She’s always used her intellect in various pursuits. She was always out in the working world. Cathy used all the education and skills she learned and then she built on those things. So when she went to D.C, she was prepared to work hard and to do something out of the ordinary for women and for African Americans to do.”

Members of the De Porres Club in 1948

Cathy’s parents were pioneers themselves.

Her mother Helen Jones Woods, 94, played trombone in the all-girl, mixed-race swing band the International Sweethearts of Rhythm. Helen’s adoptive father, Laurence C. Jones. founded the Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi, which Helen attended. Cathy and her family lived in Jim Crow Mississippi for two years. She’s a major supporter of the school today.

Cathy’s late father, William A. Woods, was the first black accounting graduate at Creighton University. He and Cathy’s mother were active in the Omaha civil rights group the De Porres Club, whose staunchest supporter was Omaha Star publisher Mildred Brown.

“Very young, I marched,” recalled Cathy Hughes, who’s the oldest of four siblings. “I was maybe 6-years old when we picketed the street car (company) trying to get black drivers. I remember vividly being slapped on the back of my head by my mother to ‘hold the sign up straight.’ I remember demonstrating but most importantly I heard truth being spoken.”

“Cathy’s parents were community-oriented people,” King said. “They cared about their community. They were well-to-do in their circles. Cathy grew up in that but she never lost her street savvy.”

While attending private schools (she integrated Duschene Academy), she said, “The nuns would send notes home to my mother saying I had delusions of grandeur, I talked all the time, and I was very opinionated. I bragged I would be the first black woman to have a nationally syndicated program.

“I was good and grown before I found out that had already been accomplished.”

Her penchant for speaking her mind stood her apart.

“When I was growing up black folks didn’t verbalize their feelings and particularly children didn’t.”

Mildred Brown gave her father an office at the Star. Cathy did his books and sold classified ads for the paper. Her father also waited tables at the Omaha Club and on the Union Pacific passenger rail service between Omaha and Idaho. She sometimes rode the train with her father on those Omaha to Pocatello runs.

She found mentors in black media professionals Brown and Star reporter-columnist, Charlie Washington. The community-based advocacy practiced by the paper and by radio station KOWH, where she later worked, became her trademark.

“We had a militancy existing in Omaha and when you’re a child growing up in that you just assume you’re supposed to try to make life better for your people because that’s what was engrained in us. We didn’t have to wait to February for black history. We were told of great black accomplishments on a regular basis at church, in school, in social gatherings. Black folks in Omaha have a nationalist pride.

“I was imbued with community service and activism. I don’t know any different. My mother on Sunday would go to the orphanage and bring back children home for dinner. We were living in the Logan Fontenelle projects and one chicken was already serving six and she would bring two or three other kids and so that meant we got a piece of a wing because Daddy always got the breast.”

During her May visit she recalled the tight-knit “village” of North Omaha where “everybody knew everybody.”

In the spirit of “always doing something to improve your community and family,” she participated in NAACP Youth Council demonstrations to integrate the Peony Park swimming pool.

“Because we were disciplined and strategic, there was a calm and deliberate delivery of demands on our part. I don’t know if it was youth naivete or pure unadulterated optimism, but we didn’t think we would fail.”

Peony Park gave into the pressure.

Opposing injustice, she said, “instilled in me a certain level of fearlessness, purpose and accomplishment I carried with me for the rest of my life.”

“It taught me the lesson that there’s power in unity.”

Her passion once nearly sparked an international incident on a University of Nebraska at Omaha Black Studies tour to Africa.

“The first day we arrived in Addis Ababa, Eithiopia, the students at Haile Selassie University #1 were staging demonstrations that ultimately led to the dethroning of emperor Haile Selassie. Well, we almost got put out of the country because when I heard there was a demonstration I left the hotel and ran over to join the picket line with the Eithiopian students. My traveling companions were like, ‘No, you cant do that in a foreign country, they’re going to deport us.’ Hey, I never saw a demonstration I didn’t feel like i should be a part of.”

Charlie Washington

The influence of her mentors went wherever she went.

“Mildred Brown unapologetically published Charlie Washington’s rants, exposes, accusations, evidence. She didn’t censor or edit him. If Charlie felt the mayor wasn’t doing a good job, that’s what you read in the Omaha Star. It took the mute button off of the voice of the black community. It promoted progress. It also provided information and jobs. It’s always been a vehicle for advocacy, inspiration and motivation.

“That probably was the greatest lesson I could have witnessed because one of the reasons some folks don’t speak out in the African-American community is they’re afraid of being financially penalized or losing their job, so they just remain silent. Mildred and Charlie did not remain silent and she was still financially successful.”

Both figures became extended family to her.

“Charlie Washington became like my godfather. He was the rabble rouser of my youth. He had the power of the pen. Charlie and the Omaha Star actually showed me the true power of the communications industry. I saw with Charlie you can tell the truth about the needs and the desires of your community without being penalized” even though he wrote “probably some of the most militant articles in the United States.”

“That’s the environment I grew up in. So the combination of Charlie always writing the truth and Mildred being able to keep a newspaper in Omaha solvent were both sides of my personality – the commitment side and the entrepreneurial side.”

Today, Hughes inspires young black communicators with her own journey of perseverance and imagination in pushing past barriers and redefining expectations.

No turning back

As an aspiring media professional. Hughes most admired Mildred Brown’s “dogged determination.”

“When somebody told Mildred no, they weren’t going to take an ad, she saw it as an opportunity to change their mind, she never saw it as a rejection. She didn’t take no seriously. No to her meant. Oh, they must not have enough information to come to the right conclusion because no is not the right conclusion.

“Nothing stopped Mildred.”

Nothing stopped Hughes either.

“When I was 17 I became a parent. I realized I was on the brink of becoming a black statistic. My son Alfred was the motivation for me to think past myself. It was the defining moment in my life direction because for the first time I had a priority I could not fail. I was like, We’ll be okay, I’m not going to disappoint you, don’t worry about it. It was Alfred who actually kept me going.”

Her first ever radio job was at Omaha’s then black format station, KOWH.

“KOWH fed into my fasciation with having a voice. I think it is truly a blessing to have your voice amplified. I wasn’t even thinking about being an entrepreneur then. I was thinking about being able to express. I wasn’t at an age yet where had come into who I was destined to be.”

She left for D.C. to lecture at Howard University at the invite of noted broadcaster Tony Brown, whom she met in Omaha. It’s then-fledgling commercial radio station, WHUR, made her the city’s first woman general manager.

Leaving home took guts. Staying in D.C. with no family or friends, sleeping on the floor of the radio station and resisting her mother’s long-distance pleas to come back or get a secure government job, showed her resolve.

“Omaha provided me a safe haven. Once in D.C., I had to rely on and call forth everything I had learned in Omaha just to survive and move forward. If I had not left, I probably would not have become a successful entrepreneur because I had a certain comfort level in Omaha. I was the apple of several individuals’ eyes. They saw potential in me, but I think their love and support would not have pushed me forward the way I had to push myself once I moved into a foreign land.”

She feels Nebraska’s extreme weather toughened her.

“It builds a certain strength in you that you may or may not find in other cities.”

If sweltering heat, high winds and subzero cold couldn’t deter her, neither could man-man challenges.

“You learn that determination that you can’t let anything turn you around. When I went to D.C. and realized there weren’t people of color doing what I wanted to do, I just kept my eye on the prize. I refused to let anyone turn me around. When you learn to persevere in all types of elements, then business is really a lot easier for you.”

Mildred Brown

Brown was her example of activist entrepreneur.

“The Star was to Omaha what Jet and Ebony were to the black community nationwide. It’s why I have this media conglomerate. When you’re 10 years old and you’re looking up to this bigger-than-life woman, she was a media mogul in my mind. She had a good looking man and wardrobe and all the trappings.”

Just as Hughes would later help causes in D.C., Brown, she said, “was kind of a one-woman social agency before social agencies became in vogue.”

“She helped a lot of people. My father graduated from college and didn’t have a place to open an office and she opened her lobby for him. He was just one of many. Charlie Washington had a very troubled background and yet because of her he rose to being respected as one of the great journalists of his time in Omaha. Dignitaries would come and sit on Charlie’s stoop and talk to him about what was going on. He was considered iconic because of Mildred Brown.

“She put students through school and raised hell to keep them there. When my mother was short my Duschene tuition, Mildred told them, ‘You’re going to get your money, but don’t be threatening to put her out.’ She literally walked the walk as well as talked the talk. She didn’t tell folks what they needed to do, she helped them do it. She continued to inspire and advise and mold me.”

Full circle

Howard’s School of Communications is named after Hughes, who never graduated college. Decades after first lecturing there, she’s a lecturer there again today.

“They say I am their most successful graduate who never matriculated. I wasn’t prepared to be the first woman general manager of a radio station in the nation’s capital. That’s why Howard sent me to Harvard to take a six-week course in broadcast management and to the University of Chicago to learn psychographic programming. I went to various seminars and training sessions. Howard literally groomed me. They were proud of the fact I was the first woman in the position they had placed me in “

Hughes readily admits she hasn’t done it by herself.

“I have been blessed by the individuals placed in my life. They sharpened me, prepared me, educated me, schooled me, nurtured me, mentored me. I have been blessed so many times to be in the right place at the right time and with the right people.”

She grew ad revenues and listeners at WHUR. A program she created, “The Quiet Storm,” popularized the urban format nationally. With ex-husband Dewey Hughes she worked wonders at WOL in D.C. After their split, she built Radio One.

Upon arriving in D.C., Hughes found an unlikely ally in Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham. She met Graham through Susan Thompson Buffett, the wife of investor Warren Bufffett, and part owner of the paper.

“Susie was staying at the Grahams’ house. At that time Susie was a singer with professional entertainment aspirations and I was her manager. Katharine Graham took an interest in me and because she had this interest in me other people, including the folks at Howard University, embraced me.”

Networking

Hughes parlayed connections to advance herself.

“Part of my innate abilities since childhood has been to recognize an opportunity and take full advantage of it.”

Her first allegiance was to listeners though. Thus, she lambasted Graham’s Post for unfair portrayals of blacks, even encouraging listeners to burn copies of the paper.

Hughes has succeeded in a male-dominated industry.

“I never thought about being a woman in a male field. First of all. I was black. I’ve never put woman first. I was black first and a woman second. I had a goal I wanted to achieve, an objective that had to be accomplished. I didn’t see it as proving something to the old boys network. I was not intimidated by being the only female.

“I was naive. I really thought there would be a whole proliferation of black women owning and managing radio stations. Women have made more progress in professional basketball – they own and coach teams – than they have in the broadcasting industry.”

Men have played a vital role in her business success.

The two black partners in Syndicated Communications, Herbert Wilkins and Terry Jones, loaned her her first million dollars to build Radio One. Wilkins has passed but Jones and his wife Marcella remain close friends.

When things were tough early on, it was Jones who instructed a downcast Hughes to change her mindset.

“He said to me when people ask you how are you doing they can’t be hearing you complaining or saying I don’t know. You’ve got to say it was a great day because the first person that hears the lie is you. Tell yourself your business is doing good. Tell yourself you’re going to make it. Everyone’s going to start agreeing with you. He told me to change my terminology, which changed my thinking, and guess what, one day it was no longer a lie, it became my truth,” she shared in Omaha.

Friends and family true

Theresa Glass said success has not changed Hughes, who looks keeping it real.

“She’s the kind of friend who’s always your friend and we always can start off where we last left off. I never have to do a whole bunch of catch up with her. We immediately go into friend mode and are able to talk to one another. A lot of times you’ve been away from somebody for a long time or your lives have really shifted and they’re not even close to being the same, and you feel awkward, and that’s not happened for us.”

Hughes acknowledges her success is not hers alone. “I didn’t do it on my own. Right time, right place, right people.” She leans on staff she calls “family.” She believes in the power of prayer she practices daily. She credits her son’s immeasurable contributions.

“Radio One was me. TV One was totally Alfred. He decided he wanted his own path. Our expansion, our going public, all of that, was in fact Alfred. He does the heavy lifting and I get to take all the bows.”

Not every mother-son could make it work.

“Alfred and I had to go to counseling, alright, because one of us was going to die during those early years. It was not happy times – and it was basically my refusal (to relinquish control),” she said at the Hilton.

Alfred Liggins acknowledges their business partnership ultimately worked.

“It was my mother’s willingness to want to see me succeed as a human being and as a business person and unselfish ability to share her journey with me. When it came time to let me fly the plane, she was more than willing to do that.”

He recognizes how special her story is.

“I could always recognize and appreciate her drive, tenacity and lessons. We didn’t let any of the mother-son-family potential squabbles disintegrate that partnership, so I guess we’ve always been a team since the day I was born.”

Challenges and opportunities

“Buddy” King. who’s had his own success in satellite radio, is happy to share a KOWH tie with Hughes.

“I’ve always admired Cathy. We KOWH alums are all proud of her success because her success shines light on what we did in Omaha.”

King further admires Radio One continuing to thrive in an increasingly unstable broadcast environment.

“iHeart media and Cumulus, two of the largest broadcast owners in the country, are both in bankruptcy, but Cathy is still chugging along. Her son has done an excellent job since making it a publicly-traded company. As the stock market fluctuates, they’ve able to survive.”

Diversification into online services and, more recently, the gaming industry, has kept Urban One fluid.

The changing landscape extends to Me Too movement solidarity around survivors of sexual harassment in the entertainment field.

“Was I subjected to it? Yes, absolutely,” Hughes said, “and I’m so glad women are stepping forward. Now we have a voice. The reality is we need more than a voice, we need to have action. Just talking about it doesn’t change it. I mean, how long have black folks talked about disparity and a whole host of things.

“It’s great that women are speaking out but we have to put pressure on individuals and on systems. Wherever we can find an opening. we must apply pressure to change it. Let’s start with education.”

She despairs over what she perceives as the dismantling of public education and how it may further erode stagnant income of blacks and the lack of inherited wealth among black families. She shared how “disturbed” she was by how Omaha’s North 24th Street has declined from the Street of Dreams she once knew.

Mrs. Marcella Jones, Alfred Liggins, III and his mother Cathy Hughes

Black media

Voices like hers can often only be found in black media.

“Black radio is still the voice of the community. Next to the black church, black-owned media is the most important institution in our community,” she said.

She embraces technology opening avenues and fostering change, but not at the expense of truth.

“I pray that truth prevails in all of these advancements we’re making. I see a world of opportunity opening, particularly for young people. I’m so impressed with this young generation behind the millennials. These kids are awesome because they’re not interested in just celebrity status. They’re interested in real change and I think the technology will be a definite part of that and I think with it comes a different level of responsibility for media than we’ve had in the past.

“Information is power. Mildred Brown understood that and it wasn’t just about a business for her – it was about a community service.”

Hughes credits an unlikely source with unifying African-Americans today.

“President Trump has single-handedly reignited activism, particularly in the black community. That did not occur in the Clinton administration, nor the Obama administration. But Trump has got people riled up, which is good. He has made people so mad that people are willing to do things, voice their opinion, and that’s why black radio is so important. You are able to say and hear things that you couldn’t get anywhere else.”

The Omaha Star is in its eighth decade. Hughes maintains its survival is “absolutely critical – because again it’s the voice of the people,” adding, “It’s our story from our perspective.” She still reads every issue. “It’s how I know what’s going on. The first thing I do is read Ernie Chambers’ editorial comments.”

Hughes is adamant blacks must retain control over their own message.

“You cannot ever depend on a culture that enslaved you to accurately portray you. That just cannot happen. I think too often African Americans have looked to mainstream media to tell our story. Well, all stories go through a filter process based on the news deliverer’s experience and perception and so often our representation has not been accurate.

“The reality is we have to be responsible for the dissemination of our own information because that’s the only time we can be reasonably assured it’s going to be from the right perspective, that it’s going to be from the right experience, and for the right reasons.”

Yet, she feels blacks do not support black media or other black business segments as much as they should.

A challenge she addressed in Omaha is black media not getting full value from advertisers.

“My son and I are not going for that. We want full value for our black audience and we insist on that with advertisers. I learned that from Mildred Brown. She did not allow y’alll to be discounted because it was a black weekly newspaper. She wanted the black readership of the Omaha Star to have the same value as a white readership to the Omaha World-Herald.

“I learned at the Omaha Star you don’t take a discount for being black.”

Still learning

Six decades into her media career and Hughes said, “I’m still learning. I’m not totally prepared for some of the responsibilities and charges I’m being blessed with now. Like I’m just learning how to produce a movie (her debut project, Media, premiered on TV One in 2017). I want to learn how to direct a movie. I want to learn how to do a series. Thank God we went into cable, which has given me an opportunity to learn the visual side.”

She’s searching for a new project to produce or direct.

“I’m reading everything I can get my hands on. I am just so thankful to the individuals in my life who have loved and nurtured me that I keep acquiring new skill sets at this age. I’m still growing and learning. which is kind of my hobby.”

Hughes is often approached about a documentary or book on her life. If there’s to be a book, she said, “I don’t want someone else interpreting who I am. I don’t want someone else telling my story from their perspective. I want to tell my own story.”

Lasting impact and legacy

Her staff is digitally archiving her career. There’s a lot to capture, including her Omaha story.

“I thank Omaha. Nothing’s better than making your mark in your hometown.”

Getting all those accolades back here is not her style.

“In Omaha, we just don’t get carried away with a whole bunch of fanfare and hero-worshiping. Again, it’s how I grew up. That’s our way of life in Omaha and I thank God for that because it’s made a big difference. It’s a whole different mentality and way of life quite frankly.”

Omaha’s impact on her is incalculable.

“It touched me probably a lot more deeply and seriously than I realized for many decades. When you’re trying to build your business you don’t have a lot of time to reflect on how did I get here and the people who influenced me. I went through a couple decades working on my career and my personal and professional growth and development before I realized the impact the Omaha Star had had on me and what a positive influence Omaha has been on me.”

“Buddy” King said he always knew if from afar.

“Even when she was a young single parent, Cathy was a fighter. It all to me comes back to her Omaha roots.”

Though Alfred Liggins and his mom have been back several times, with this 2018 visit, he said, “you feel like you finally made it and made good and you’re making you’re community proud.”

“It’s about meaning and legacy. That’s why this is hugely different. It really is the culmination of a journey I’ve shared with my mother trying to elevate ourselves and in the process elevating the community from which we came. I’m proud to have been part of what my mother embarked on and I feel like I am being recognized alongside her.

“And it is a deserving honor for her. She’s got guts, grit and she still has a ton of energy. She always gives me lots of praise and lots of love – until I do something she doesn’t like. But it has kept me on the up-and-up and to have my nose to the grindstone.”

At the close of her Empowerment Network talk, Hughes articulated why coming back to acclaim meant so much.

“I think Omaha teaches you to best your best and practices tough love. If you have the nerve to leave here and go someplace else, you better hope you do good because if you come home, you don’t want to hear (about returning a failure). But it’s really love telling you, You should have done better, you should have been more persistent.

“That whole village concept sometimes is not comfortable but it’s so productive because it pushes you to best your best. It teaches you that when you come home one day … they may hang a sign and name a boulevard in your honor.”

As she told a reporter earlier, “My picture’s on the floor of the Press Club, okay It don’t get no better than that.”

Visit https://urban1.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

A series commemorating Black History Month – North Omaha stories Part IV

A series commemorating Black History Month – North Omaha stories Part III

Native Omaha Days 2017: A Homecoming Like No Other

Here is the Reader (www.thereader.com) story I did previewing Native Omaha Days 2017. From all reports, the celebration was a great success. Pam and I made it down to a few different Native Omaha Days events and we thoroughly enjoyed ourselves, too. If you’ve never been, you’ve got to sample this authentiic slice of Omaha.

Native Omaha Days 2017: A homecoming like no other

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The African-American diaspora migration from the South helped populate Omaha in the 20th century. Railroad and packing house jobs were the lure. From the late 1960s on, a reverse trend has seen African-Americans leave here en mass for more progressive climes. A variant to these patterns finds thousands returning each odd-numbered August for a biennial community reunion known as Native Omaha Days.

The 21st reunion happens July 31 through August 7.

If you’ve not heard of it or partaken in it, you’re probably not black or some of your best friends are not black, because this culture-fest is in Omaha’s Afrocentric DNA. But organizers and participants emphasize everyone’s welcome to join this week-long party.

Featured events range from gospel and jazz concerts to talks and displays to a parade to a ball.

Nobody’s quite sure how many native Omahans living outside the state head home for it to rekindle relationships and visit old haunts.

There are as many takes on it as people engaging in it.

Thomas Warren, president-CEO of the Urban League of Nebraska, which this year hosts its 90 anniversary gala during Omaha Days, may put it best:

“People make it a purpose to come back.”

Reshon Dixon left Omaha for Atlanta 24 years ago and she’s been coming back ever since, except when military commitments prevented it. She hopes to free up her schedule for this year’s fest.

“I’m trying to. I usually plan a year ahead to come back.”

She said she brought her children for it when they were young because “that’s pretty much where our roots are from.” She’s delighted her now grown kids are “planning to come back this year.”

Serial nonprofit executive Viv Ewing said Omaha Days touches deep currents.

“People look at this event very fondly. In the off-year it’s not being held, people ask when is it happening again and why isn’t it every year because it’s such a great time bringing the community together with family and old friends. People look forward to it.

“There are people who have moved away who plan their vacations so that they come back to Omaha during this particular time, and that says a lot about what this event means to many people across the country.”

Even Omaha residents keep their calendars open for it.

“I’ve cut business trips as well as vacations short in order to make sure I was at home during this biennial celebration,” Warren said.

Sheila Jackson, vice president of the nonprofit that organizes it, said, “It’s one big reunion, one big family all coming together.”

Juanita Johnson, an Omaha transplant from Chicago, is impressed by the intentionality with which “people come together to embrace their commonality and their love of North Omaha.” She added, “It instills pride. It has a lot of excitement, high spirits, energy and enthusiasm.”

As president of the Long School Neighborhood Association and 24th Street Corridor Alliance, Johnson feels Omaha Days could play a greater role in community activation and empowerment.

“I think there’s an opportunity for unity to develop from it if it’s nurtured beyond just every two years.”

Empowerment Network director of operations Vicki Quaites-Ferris hopes it can contribute to a more cohesive community. “We don’t want the unity to just be for seven days. We want that to overflow so that when people leave we still feel that sense of pride coming from a community that really is seeing a rebirth.”

Ewing said even though it only happens every two years, the celebration is by now an Omaha tradition.

“It’s been around for four decades. It’s a huge thing.”

No one imagined it would endure.

“I never would have dreamt it’d be this big,” co-founder Bettie McDonald said. “I feel good knowing it got started, it’s still going and people are still excited about it.”

She said it’s little wonder though so many return given how powerful the draw of home is.

“They get emotional when they come back and see their people. It’s fun to see them greet each other. They hug and kiss and go on, hollering and screaming. It’s just a joyous thing to see.”

Dixon said even though she’s lived nearly as long in Atlanta as she did in Omaha, “I’m a Cornhusker first and a Peach second.”

Likewise for Paul Bryant, who also left Omaha for Atlanta, there’s no doubt where his allegiance lies.

“Omaha will always be home. I’m fifth generation. I’m proud of my family, I’m proud of Omaha. Native Omaha Days gives people another reason to come back.”

A little extra enticement doesn’t hurt either.

“We really plan things for them to make them want to come back home,” said McDonald. She drew from the fabled reunion her large family – the Bryant-Fishers – has held since 1917 as the model for Omaha Days. Thus, when her family convenes its centennial reunion picnic on Sunday, August 13, it will cap a week’s worth of events, including a parade and gala dinner-dance, that Omaha Days mirrors.

Bryant, a nephew of McDonald, is coming back for the family’s centennial. He’s done Omaha Days plenty of times before. He feels both Omaha Days and reunions like his family’s are ways “we pass on the legacies to the next generation.” He laments “some of the younger generations don’t understand it” and therefore “don’t respect the celebratory nature of what goes on – the passing of the torch, the knowing who-you-are, where-you-come-from. They just haven’t been taught.”

Sheila Jackson said it takes maturity to get it. “You don’t really appreciate Omaha Days until you get to be like in your 40s. That’s when you really get the hang of it. When you’re younger, it’s not a big thing to you. But when you get older. it seems to mean more.”

Sometime during the week, most celebrants end up at 24th and Lake Streets – the historic hub for the black community. There’s even a stroll down memory lane and tours. The crowd swells after hours.

“It’s almost Omaha’s equivalent of Mardi Gras, where you’ll have thousands people just converge on the intersection of 24th and Lake, with no real plans or organized activities,” Warren said. “But you know you can go to that area and see old friends, many of whom you may not have seen for several years. It gives you that real sense of community.”

Fair Deal Village Marketplace manager Terri Sanders, who said she’s bound to run into old Central High classmates, called it “a multigenerational celebration.”

Touchstone places abound, but that intersection is what Warren termed “the epicenter.”

“I’m always on 24th and Lake when I’m home,” said homegrown media mogul Cathy Hughes, who will be the grand marshall for this year’s parade. “I love standing there seeing who’s coming by and people saying, ‘Cathy, is that you?’ I always park at the Omaha Star and walk down to 24th and Lake.”

“I do end up at 24th and Lake where everybody else is,” Dixon said. “You just bump into so many people. I mean, people you went to kindergarten with. It’s so hilarious. So, yes, 24th and Lake, 24th Street period, is definitely iconic for North Omahans.”

That emerging art–culture district will be hopping between the Elks Club, Love’s Jazz & Arts Center, the Union for Contemporary Art, Omaha Rockets Kanteen, Jesse’s Place, the Fair Deal Cafe and, a bit southwest of there, the Stage II Lounge.

Omaha Days’ multi-faceted celebration is organized by the Native Omahans Club, which “promotes social and general welfare, common good, scholarships, cultural, social and recreational activities for the inner city and North Omaha community.” Omaha Days is its every-other-year vehicle for welcoming back those who left and for igniting reunions.

The week includes several big gatherings. One of the biggest, the Homecoming Parade on Saturday, August 6, on North 30th Street, will feature drill teams, floats and star entrepreneur Cathy Hughes, the founder-owner of two major networks – Radio One and TV One. She recently produced her first film, the aptly titled, Media.

Hughes is the latest in a long line of native and guest celebrities who’ve served as parade grand marshall: Terence Crawford, Dick Gregory, Gabrielle Union.

During the Days, Hughes will be honored at a Thursday, August 3 ceremony renaming a section of Paxton Blvd., where she grew up, after her. She finds it a bit surreal that signs will read Cathy Hughes Boulevard.

“I grew up in a time when black folks had to live in North Omaha. Never would I have assumed that as conservative as Omaha, Neb. is they would ever consider naming a street after a black woman who happened to grow up there. And not just a black woman, but a woman, period. When I was young. Omaha was totally male-dominated. So I’m just truly honored.”

“Omaha Days does not forget people that are from Omaha,” Reshon Dixon said. “They acknowledge them, and I think that’s great.”

During the Urban League’s Friday, August 4 gala concert featuring national recording artist Brian McKnight at the Holland Performing Arts Center, two community recognition awards will be presented. The Whitney M. Young Jr. Legacy Award will go to Omaha Economic Development Corporation president Michael Maroney. The Charles B. Washington Community Service Award will go to Empowerment Network president Willie Barney.

Maroney and Barney are key players in North Omaha redevelopment-revitalization. Warren said it’s fitting they’re being honored during Omaha Days, when so many gathering in North O will have “the opportunity to see some of those improvements.”

Quaites-Ferris said Omaha Days is a great platform.

“It’s an opportunity to celebrate North Omaha and also the people who came out of North Omaha. There are people who were born in North Omaha, grew up in North Omaha and have gone on to do some wonderful things locally and on a national level. We want to celebrate those individuals and we want to celebrate individuals who are engaged in community.

“It’s a really good time to celebrate our culture.”

“I really admire the families who are so highly accomplished but have never left, who have shared their talents and expertise with Omaha,” said Hughes. She echoes many when she expresses how much it means returning for Omaha Days.

“Every time I come, I feel renewed,” she said. “I feel the love, the kindred spirit I shared with so many of my classmates, friends, neighbors. I always leave feeling recharged. I can’t wait.”

The celebration evokes strong feelings.

“What’s most important to me about Omaha Days is reuniting with old friends, getting to see their progression in life, and getting to see my city and how it’s rebuilt and changed since I left,” Dixon said. “You do get to share with people you went to school with your success.”

“It’s a chance to catch up on what’s going in everybody’s life,” Quaites-Ferris said.

Juanita Johnson considers it. among other things,

“a networking opportunity.”

Paul Bryant likes the positive, carefree vibe. “There we are talking about old times. laughing at each other, who got fat and how many kids we have. It’s 1:30-2 o’clock in the morning in a street crowded with people.”

“By being native, many of these individuals you know your entire life, and so there’s no pretense,” Warren said.

Outside 24th and Lake, natives flock to other places special to them.

“When I come back,” Dixon said, “my major goal is to go to Joe Tess, get down to the Old Market, the zoo, go through Carter Lake and visit Salem Baptist Church, where I was raised. My absolute favorite is going to church on Sunday and seeing my Salem family.”

Some pay respects at local cemeteries. Dixon will visit Forest Lawn, where the majority of her family’s buried.

Omaha Days is also an activator for family reunions that blend right into the larger event. Yards, porches and streets are filled with people barbecuing, chilling, dancing. It’s one contiguous party.

“It’s almost like how these beach communities function, where you can just go from house to house,” Hughes said.

The Afro-centric nature of Omaha Days is undeniable. But participants want it understood it’s not exclusive.

“It just happens to be embedded in the African-American community, where it started,” Dixon said. “Anyone can come, anyone can participate. It has become a little bit of a multicultural thing – still primarily African-American.”

Some believe it needs to be a citywide event.

“It’s not like it’s part of the city,” Bryant said. “It’s like something that’s going on in North Omaha. But it’s really not city-accepted. And why not?”

Douglas Country Treasurer John Ewing agrees. “Throughout its history it’s been viewed as an African-American event when it really could be something for the whole community to embrace.”

His wife, Viv Ewing, proposes a bigger vision.

“I would like to see it grow into a citywide attraction where people from all parts come and participate the way they do for Cinco de Mayo. I’d like to see this event grow to that level of involvement from the community.”

Terri Sanders and others want to see this heritage event marketed by the city, with banners and ads, the way it does River City Roundup or the Summer Arts Festival.

“It’s not as big as the College World Seriesm but it’s significant because people return home and people return that are notable,” Sanders said.

Her daughter Symone Sanders, who rose to fame as Bernie Sanders’ press secretary during his Democratic presidential bid, may return. So may Gabrielle Union.

Vicki Quaites-Ferris sees it as an opportunity “for people who don’t live in North Omaha to come down and see and experience North Omaha.” She said, “Sometimes you only get one peripheral view of North Omaha. For me, it’s an opportunity to showcase North Omaha. Eat great food, listen to some wonderful music, have great conversation and enjoy the arts, culture, business and great things that may be overlooked.”

John Ewing values the picture if offers to native returnees.

“It’s a great opportunity for people who live in other places to come back and see some of the progress happening in their hometown.”

Recently completed and in-progress North O redevelopment will present celebrants more tangible progress than at anytime since the event’s mid-1970s start. On 24th Street. there’s the new Fair Deal Village Marketplace, the renovated Blue Lion Center and the Omaha Rockets Kanteen. On 30th, three new buildings on the Metro Fort Omaha campus, the new mixed-use of the former Mister C’s site and the nearly finished Highlander Village development.

For some, like Paul Bryant, while the long awaited build-out is welcome, there are less tangible, yet no less concerning missing pieces.

“I think the development is good. But I truly wish in Omaha there was more opportunity for African-American people to be involved in the decision-making process and leadership process. But that takes a conscious decision,” Bryant said.

“What I’ve learned from Atlanta is that unlike other cites that wanted to start the integration process with children, where school kids were the guinea pigs, Atlanta started with the professions – they started integrating the jobs. Their slogan became “We’re a city too busy to hate.” So they started from the top down

and that just doesn’t happen in Omaha.”

He worked in Omaha’s for-profit and non-profit sectors.

“A lot of things happen in Omaha that are not inclusive. This isn’t new. Growing up, I can remember Charlie Washington, Mildred Brown, Al Goodwin, Bob Armstrong, Rodney S. Wead, talking about it. The story remains the same. We’re on the outside running nonprofits and we’ve got to do what we have to do to keep afloat. But leadership, ownership, equity opportunities to get involved with projects are few and far between. If you’re not able to share in the capital, if your piece of the equation is to be the person looking for a contribution, it’s hard to determine your own future.”

Perhaps Omaha Days could be a gateway for African-American self-determination. It’s indisputably a means by which natives stay connected or get reconnected.

“I think its’ critical,” said Cathy Hughes, who relies on the Omaha Star and her Omaha Days visits to stay abreast of happenings in her beloved North O.

She and John Ewing suggest the celebration could play other roles, too.

“I think it’s a good way to lure some natives back home,” Hughes said. “As they come back and see the progress, as they feel the hometown pride, it can help give them the thought of, ‘Maybe I should retire back home in Omaha.'”

“I think Omaha could do a better job of actually recruiting some of those people who left, who are talented and have a lot to offer, to come back to Omaha,” Ewing said, “and if they’re a business owner to expand or invest in Omaha. So there’s some economic opportunities we’ve missed by not embracing it more and making it bigger.”

Ewing, Sanders and others believe Omaha Days infuses major dollars in hotels, restaurants, bars and other venues. The Omaha Convention and Visitors Bureau does not track the celebration’s ripple effect, thus no hard data exists..

“I don’t think it’s accurately measured nor reflected in terms of the amount of revenue generated based on out-of-town visitors,” Warren said. “I suspect it has a huge impact on commerce and activity.”

Some speculate Omaha Days could activate or inspire homegrown businesses that plug into this migration,

“I think it can certainly be a spark or a catalyst,” Warren said. “You would like to see the momentum sustained.

You hope this series of events may stimulate an idea where a potential entrepreneur or small business owner sees an opportunity based on the activity that occurs during that time frame. Someone could launch a business venture. Certainly, I think there’s that potential.”

For Omaha Days history and event details, visit nativeomahacub.org.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com,

North Omaha: Where for art thou?

North Omaha: Where for art thou?

©by Leo Adam Biga

Our fair city has a curious case of tunnel vision when it comes to North Omaha.

What constitutes North Omaha is different depending on who you talk to. Officially or technically speaking, it is one of four geographic quadrants. North O itself is made up of a diverse number of neighborhoods, many of which are not generally considered part of it. For example. most of us don’t include the Dundee business district and surrounding neighborhood around Underwood Avenue as North O when in fact it is. The same for Happy Hollow, Country Club, Benson, Cathedral, Gold Coast, Florence and many others well north of Dodge that have their own stand-alone names, designations, associations and identities. When North O is referenced by many individuals and organizations, what they’re really referring to is Northeast Omaha. For many, North O has come to mean one narrow set of characteristics and conditions when in reality it is much more diverse geographically, socio-economically, racially and every other way than any tunnel vision prism does justice to. Why does this happen so persistently to North O? Well, there are many agendas at work when defining or designating North O as one thing or another. When viewed in a racialized way, North O is suddenly a black-centric district. When viewed as prime development territory. North O’s either a distressed area or a great investment opportunit. When viewed in historical terms, North O’s variously a military outpost, a Mormon encampment, a bustling Street of Dreams or the site of riots and urban renewal disruption and the downward spiral that followed. When measured statistically and comparatively, North O often comes out as the epicenter of poverty, underemployment, educational disparity, STDs, gang violence and other disproportionately occuring ills when in fact in totality, taking into account all its neighborhoods, North O is doing well. When viewed in redevelopment terms, North O is s collection of revitalized commercial and residential areas and of pockets still in need of redos. How you see it doing and where you see it going, what you count as part it or not, the amount of monies that flow in or out and the types of projects, initatives and developments that happen and dont have to do with what people are predisposed to think about it and expect from it. When it comes to North O, your perception of it and engagement with it conforms to your own ideas, attitudes, beliefs, visions, plans, experiences. For some, it represents an avenue of opportunity and for others a plaee of stagnation. Some see it and treat it as a social services mission district, while others see it as a wellspring of commerce, entrepreneurship and possibility. People living there surely have very different takes on it as a community, even on what makes North O, North O. Certainly, people living outside the area have very different takes on it than the people residing there. If there is an essential North O identity it is one of diversity and aspiration, hard work, no frills and pride. North O never has been and never will be just one thing or another. You can reduce to it a tag or a headline and to a segment or a section if you want but that will never reflect the large, complex mosaic of cultures and influences, assets and resources that comprise it. North O ha for too long been stereotyped and compartmentalized, stigmatized and marginalized. It has too long been misunderstood. Instead of only seeing it in its parts, what if we began looking at it as a whole? Maybe if we started thinking in terms of how everything that happens in one neighborhood affects everything else, then perhaps future quality of life development can be more organic and inclusive.

North Omaha contains some of the metro’s oldest, most compelling history. Long established neighborhoods, parks, boulevards, buildings and other public spaces have roots in diverse peoples and events that helped shape the city. Despite this rich heritage, mass media depictions tend to emphasize a narrow, negative view of North O as a problematic place of despair and neglect.

Problems exist, but North O has been a place of great aspirations and successes. One of its historic main drags, North 24th Street, has inspired many names. Jews called it the Miracle Mile. African-Americans dubbed it the Street of Dreams. More informally, it went by the Deuce or the Deuce Four. Other districts within North O, such as Florence, Benson and Dundee, each have their own vibrant histories. These neighborhoods, along with the North 24th and North 30th Street corridors, are undergoing major revivals.

North O’s history extends way back:

A Great Plains army installation, Fort Omaha, was the site of an historic ruling about the nature of man was rendered in the Trial of Chief Standing Bear. The fort’s grounds are now the main campus for Omaha’s fastest growing higher education institution, Metropolitan Community College, and for the Great Plains Theatre Conference. An annual pow wow is held there.

The Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition brought the nation and world to this once frontier outpost turned fledgling city. The Trans-Miss site is where Kountze Park and many stately homes stand.

Pioneering Mormon families trekked to and encamped in what is now North O. They later disembarked there for far western travels to the Great Salt Lake. Area Mormon artifacts and historic sites abound.

Diversity may not be the first thing you think of when it comes to North O, but it is a blend of many different peoples and places. A wide range of immigrants and migrants have settled there over time. Jews, Italians, Germans, Irish, Africa-Americans, Africans, Asians, Hispanics.

Its strong faith community includes a wide variety of Christian churches, Some of the churches have rich histories dating back to the early 20th century. Many older worship places have undergone restoration. Several buildings in North O own national historic preservation status, including the Webster Telephone Exchange that later saw use as a community center and the home of Greater Omaha Community Action until James and Bertha Calloway used grant money to convert it into the Great Plains Black History Museum.

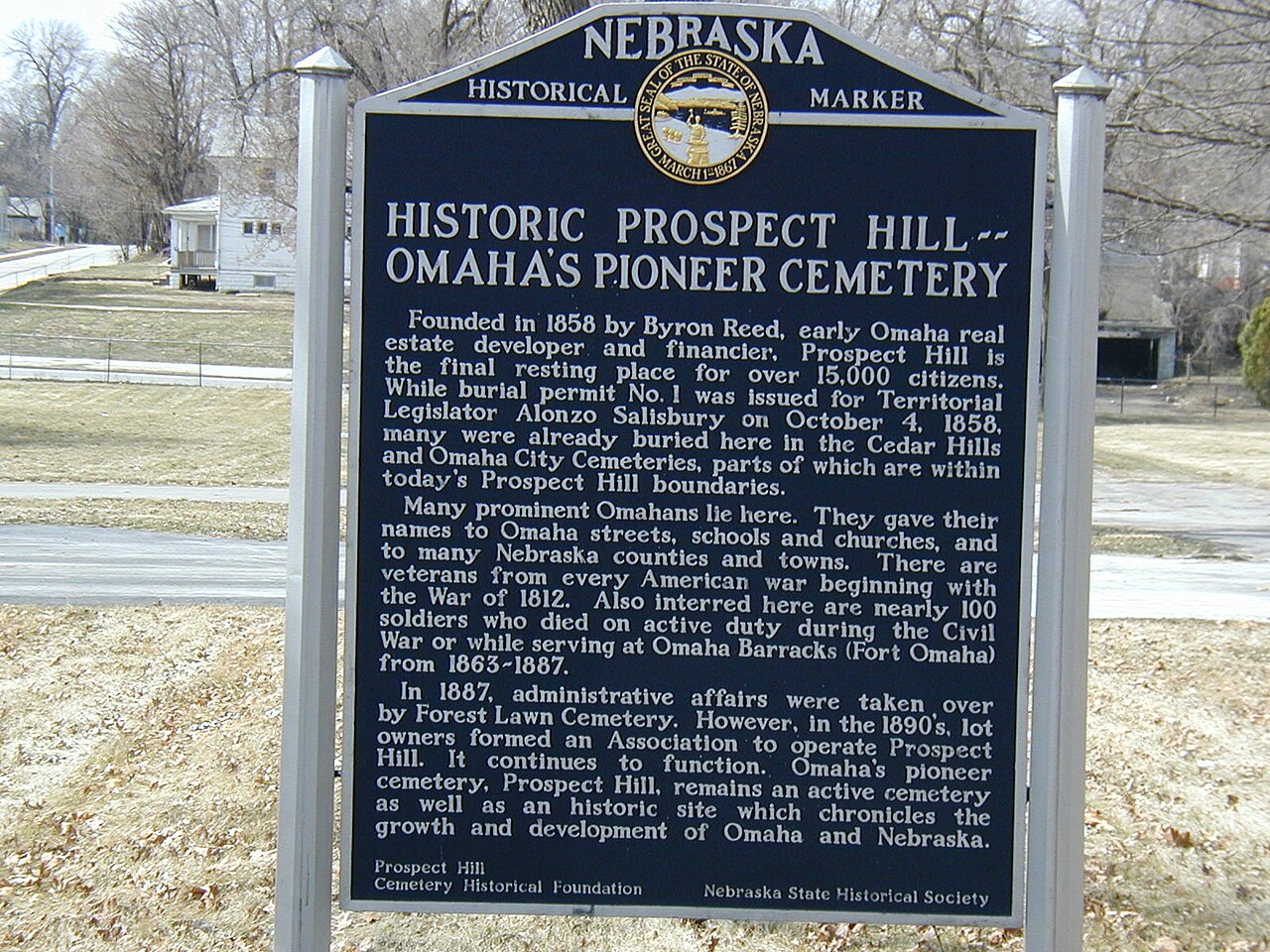

Among the historic spots to visit in North O are Prospect Hill Cemetery where many city founders are buried, and the Malcolm X Memorial Birthsite where slain social activist Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little.

African-Americans built a strong community through their toil as railroad porters and packinghouse workers and through their education in all black schools. North O encompassed a leading vocational school, Technical High. The district continues to support quality public and private elementary schools and public secondary schools. It is home to one of the Midwest’s top post-secondary institutions in Creighton University and to a thriving community college in Metro.

North O is also home to some of the city’s oldest, most distinguished neighborhoods, including Dundee, Benson, Bemis, Gold Coast, Cathedral, Walnut Hill, Kountze Place, Minne Lusa and Florence. Blacks were denied the opportunity to live in many of those neighborhoods until discriminatory housing practices ended.

Bounded by the Missouri River on the east. 72nd Street on the west, Cuming-Dodge Streets on the south and Interstate 680 on the north, North O is a varied landscape of attractive flatlands, hills, woods, parks and tree-lined boulevards. There are promontories and overlooks with stunning views of the bluffs across the river and of downtown.

The area’s fertile soil has produced notables in film (Monty Ross), television (Gabrielle Union), theater (John Beasley), music (Buddy Miles), literature (Wallace Thurman, Tillie Olsen), media (Cathy Hughes), sports (Bob Gibson), finance (Warren Buffett), politics (George Wells Parker) and social activism (Malcolm X). It is where the interracial social action organization the De Porres Club made equality stands a decade before the civil rights movement. Black plaintiffs later forced school integration in the public schools.

North O hosts long-lived and proud chapters of the NAACP and the Urban League as well as dynamic local affiliates of the Boys and Girls Club, YMCA, Campfire and Girl Inc.

The area does have high poverty pockets but it’s home to hard-working people, many with higher education and vocational training. It encompasses blue collar and white collar professionals, laborers, entrepreneurs and grassroots activists. It is a community of families, neighborhoods, small businesses and major manufacturers.

The ties that bind run deep there. For decades Native Omaha Days has brought together thousands from around the country for a week-long slate of events reuniting former and current residents who share North O as their birthplace and coming of age place.

The infrastructure of this inner city does have its challenges. There is still a disproportionate number of substandard houses, abandoned homes. vacant lots and food deserts. But an influx of projects is adding new residential units and commercial properties that are putting in place stable, sustainable improved quality of life features.

North O is the wellspring and nexus of strong community revitalization efforts such as those of the Empowerment Network, Omaha Economic Development Corporation, Family Housing Advisory Services and Omaha Small Business Network working to strengthen the community.

Redevelopment underway in northeast Omaha is in direct response to decades of economic inertia that set in after civil disturbances laid waste to the historic North 24th Street.hub. Urban renewal also severed the community, thus disrupting neighborhoods, creating isolated segments and diverting commercial development.

There was a time when North O possessed all the amenities it needed. Back in the day the dynamic entertainment scene acted as a launching pad for talented local musicians and a stopover for top touring artists. It was a destination place with its clubs, bars and restaurants featuring live music. Some of that same spirit and activity is being recaptured again. Harder to get back might be all the professional services that could be had within a few blocks but as more people move back to North O and set up shop, that could change, too.

Today’s revitalized North 24th mirrors similar community building endeavors on North 30th, North 16th, the Radial Highway, Ames Avenue, Hamilton Street, Lake Street, Maple Street and elsewhere. Business thoroughfares and residential blocks pockmarked by neglect are starting to sprout new roots and roofs.

An anchor through it all has been the Omaha Star. It continues a long legacy as a black woman owned and operated newspaper that gives African-Americans a platform for calling out wrongdoers in the face of injustice and celebrating positive events.

Decades before the Black Lives Matter movement, vital voices for self-determination were raised by North O leaders, including Mildred Brown, Whitney Young, Charlie Washington, Ray Metoyer, Dorothy Eure and Ernie Chambers. No one’s spoken out against injustice more than Chambers. He’s been a constant force in his role as a legislator and enduring watchdog for the underdog. His mantel is being taken up by dynamic new leaders such as Sharif Liwaru and Ean Mikale.