Omowale Akintunde’s in-your-face race film for the new millennium, “Wigger,” introduces America to new cinema voice

Over the past 20 years I have had the opportunity of stumbling upon some filmmakers from my native Nebraska whose work has inspired me and many others. I first became aware of Alexander Payne back when I was programming art films in the late 1980s-early 1990s. This was before he’d directed his first feature. I read something about him somewhere and I ended up booking his UCLA thesis film, The Passion of Martin, for screenings by the nonprofit New Cinema Cooperative. Hardly anyone came, but his work was unusually mature for someone just out of college. That lead to my interviewing him in the afterglow of his feature debut, Citizen Ruth, and his making Election. I’ve gone on to interview him dozens of times and to write extensively about his work. I even spent a week on the set of Sideways. I almost made it to Hawaii for a couple days on the set of his film, The Descendants. I may be spending weeks on the set of his next film, Nebraska. It’s been an interesting ride to chart the career of someone who has become one of the world’s preeminent filmmakers.

More recently, I was fortunate enough to get in on the evolving young career of Nik Fackler, whose feature debut, Lovely, Still, shows him to be an artist of great promise.

More recently still I discovered Charles Fairbanks, a true original whose short works, including Irma and Wrestling with My Father, defy easy categorization. He is someone who will be heard from in a major way one day.

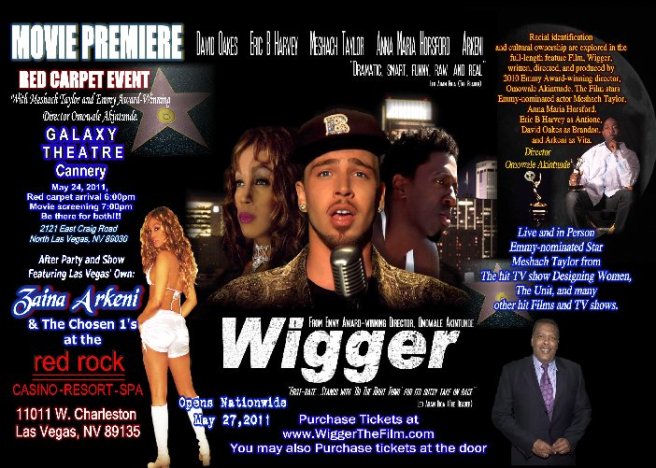

In between Fackler and Fairbanks I was introduced to Omowale Akintunde, an academic and artist whose short film Wigger became the basis for his feature of the same name. Akintunde and Wigger are the subjects of the following story, which appears in The Reader (www.thereader.com). The small indie film, made entirely in Omaha, is getting some theater exposure around the country.

This blog contains numerous stories about these filmmakers and others I’ve had the pleasure to interview and profile.

Omowale Akintunde’s in-your-face race film for the new millennium, “Wigger,” introduces America to new cinema voice

©by Leo Adam Biga

As published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Make no mistake about it, filmmaker Omowale Akintunde intends for his 2010 racially-charged Omaha-made feature, Wigger, to provoke a strong response.

After premiering here last year, and in limited theatrical release around the country, the dynamic looking and sounding film returns for a 7 p.m., July 28 red carpet screening at the Twin Creek Cinema. It’s back just in time for Native Omaha Days (July 27-August 1), the biennial African-American heritage celebration.

The film, definitively set in North Omaha, plays off a young white man, Brandon (David Oakes), so enamored with African-American culture he’s adopted its trappings. He pursues a R & B career amid skeptics, users and haters. His interracial relationships, both platonic and romantic, are tinged with undercurrents.

“He feels he has transcended whiteness,” says Akintunde, chair of the University of Nebraska at Omaha Department of Black Studies. “On the other hand, his father is a very overt racist who calls people nigger, talks about fags and Jews. He’s very open about his biases. So Brandon sees himself as disconnected from his father.”

Brandon’s best friend, Antoine, is black. As pressures build, the two have a falling out, each accusing the other of racism, unintentionally setting in motion a tragedy.

“There’s just some things you learn in a black household you don’t get in a white household, and vice versa,” says Eric Harvey, who plays Antoine and co-produced the film, “so that line between them keeps them from being as close as they really want to be. They’re both in denial of self-conscious racism.

“It’s not a bad thing, it’s a reality. We do things without thinking about it. Seriously, it’s been embedded for so long it’s just the norm.”

This is the prism through which Akintunde, who produced, wrote and directed the film, examines polarizing attitudes. Nearly everyone in the film exhibits some prejudice or engages in some profiling. Race and privilege cards abound.

“I thought this story…was the perfect premise to get into some real deep stuff,” says Akintunde. “It’s about these two characters with this improbable dream. This white boy who loves black culture and wants to be accepted comes from a background that says, why would you want to be like THEM? And then them telling him you’re not one of US. And how does one make that fit?”

The film suggests a post-racial world is a fallacy short of some deep reckoning or ongoing discussion. It’s message is that not confronting or deconstructing our racial hangups has real consequences. Akintunde can spout rhetoric with the best, but his film never devolves into preaching.

He does something else in offering a raw, authentic slice of black inner city life here with glimpses of Native Omaha Days, the club scene, neighborhoods, church. He avoids the misrepresentations of another urban drama set here, Belly (1998).

“This is the first film that really deals with North Omaha and attempts to make icons of the things that have become emblematic of it,” says Akintunde. “I really did want to show this city and that community some big love. It was very intentional I made the location a character in this film.”

Rare for any small independent, even more so for a locally produced one, Wigger is managing theatrical bookings at commercial houses, albeit mostly one-night engagements, coast to coast. In classic roadshow fashion, the filmmaker is brokering screenings through his own Akintunde Productions. He pitches exhibitors and when he sells a theater or chain on the flick he often appears, film in hand, to help promote it. He often does a post-show Q & A.

Meshach Taylor

In May the film got national mention when co-star Meshach Taylor plugged it on The Wendy Williams Show.

The success is the latest affirmation for Akintunde, who has a solid reputation as a serious artist and scholar. His 2009 nonfiction film, An Inaugural Ride to Freedom, which charts the bus trek a group of Omahans made to the Obama presidential inauguration, won a regional Emmy as Best Cultural Documentary.

The Alabama native has heeded his creative and academic sides for as long as he can remember. “I always wanted to be a university professor and I always wanted to make films,” he says. “I wanted to make films because there are so many people who will never attend a university, who will never be involved in a high level ivory tower discussion, and movies reach everybody. What I always wanted to do is to meld those two worlds — to use film to teach academics.”

In a career that’s seen him widely published on issues like white privilege and diversity, he’s penned academic texts, short stories, a novel and a children’s book. He says he always conceives his stories cinematically. Well into his professional career though, the cinephile still hadn’t realized his dream of filmmaking.

“It was one of those things you always wanted to do but everyone discouraged you from because they felt you needed a real job,” he says. “No one ever thought that was a credible goal. I finally reached a point where I realized credibility was determined by me, and if I had a passion for filmmaking I needed to do what…makes me happy. That was one of the missing things in my life.”

During a sabbatical he attended the New York Film Academy‘s Conservatory Filmmaking Program. His thesis project was a short version of Wigger. Another of his shorts, Mama ‘n ‘Em, was selected for the Hollywood Black Film Festival.

An expanded Wigger script became his feature debut. He and producer Michael Murphy financed the film themselves. Akintunde imported principal cast and crew from outside Nebraska, including film-television actors Meshach Taylor (who was in the short) and Anna Maria Horsford, cinematographer Jean-Paul Bonneau and composers Andre Mieux and Chris Julian.

“I didn’t follow any of the traditional methodologies in terms of even making Wigger, much less how I promote it and get it out there.”

David Oakes

Kim de Patri (Kim Patrick), who plays Antoine’s girlfriend Shondra, says the script’s unvarnished truth grabbed her.

“It said every single thing most people think (about race) but would never actually say. It was the way it was said and the voice it was speaking from, these characters. It was so real and so honest and it came from a very genuine place.”

Taylor, a big advocate of Akintunde’s, says he likes how the film “challenges people’s concepts of what racism really is” by dealing with “the reality of institutionalization racism,” adding, “It’s not an overt thing, it’s really built into the system.” He says he and Akiintunde just click. “I like what he’s trying to do. It’s really wonderful to have someone who has an intellectual approach to filmmaking but still has the artistic sensibility to make it fun and interesting to watch.”

To date, Akintunde has arranged limited bookings in mid and major markets, ranging from Minneapolis and Birmingham to Denver, Las Vegas and Los Angeles. It’s one continuous run was at the Edge 12 in Birmingham, the home of Tim Jennings, who has a supporting role. Akintunde says an Edge Theaters official “became a big fan and supporter” of the film and offered a one-week run.

Future screenings are scheduled in Chicago, Atlanta, Washington D.C. and New York City. He’s negotiating with Edge for new, multi-date runs.

Anna Maria Horsford

With Wigger, he’s taken a subject and set of conventions rife with stereotype and exploitation possibilities and dramatized them as an extension of his scholarship. His goal is as much to frame a dialogue as to make a profit.

“My biggest objective here was to really put a story out there that would compel people to talk about institutionalized bias in a way that I don’t think we’ve had. I really wanted to have a national conversation about this.”

In the tradition of Do the Right Thing and A Time for Burning, which was shot in Omaha 45 years ago, Wigger makes a full-frontal assault on our expectations.

“Obviously, I chose a very provocative and incendiary title because I want it to evoke a very strong, visceral response. I want to incite people. I want to grab America by the collar and just shake them,” he says. “The title itself is very problematic for people because we live in a society where we won’t even pronounce the word nigger. It becomes the “n word” in any context in which we use it.

“In many of the (Q & A) discussions we talk about why I gave the film such a provocative title — it’s because I want people to stop and think. Certain words are simple, symbolic representations of a much deeper social problem that we tend to mask by using silly euphemisms, as if we do not know what they mean, instead of looking at why the actual word bothers us.”

The film deftly handles topics usually glossed over or overdone without becoming pedantic or sensationalistic, though it does get melodramatic. As an “ethnic” genre pic, it draws largely black audiences, but enough of a mix that Akintunde is able to gauge how it plays to black and white viewers.

“There has not been a huge disparity in response and I think that’s because Wigger takes on multiple kinds of institutionalized biases. What I find is people see in a sense the mirror being held up to themselves.”

If nothing else, he hopes the film encourages viewers to see past the taboo or race.

“In our society we’re taught the way you demonstrate you’re not racist is to pretend you don’t know race exists. Because of this color blind mentality we’re all supposed to be adopting, we have come to a point where we can’t discuss the 600 pound gorilla in the room, and what Wigger does is give people an opportunity to discuss the 600 pound gorilla.

“But it goes beyond that — to our gender, our class, our sexuality, our religious beliefs. These are so interwoven and so inextricably bound that it is impossible to construct yourself in any of those domains without taking into consideration the others.”

Omowale Akintunde

Wigger shows how racism, sexism and other isms thrive in both white and black culture. Everyone is guilty of some kind of bias.

“I try not to make a compelling argument of black versus white,” says Akintunde, “but about what it means to be either and how we can transcend these boundaries, these ridiculous social constructions, these radicalized expectations that keep us divided. I believe we have the ability to cross these boundaries and truly become a society resolute in its solidarity.

“I think the reason people don’t leave that film feeling as if they’re more divided is because of the way the film is structured. I think you cant help but see how really alike we are. It’s hard to walk away from this movie seeing the world in, no pun intended, black and white.”

Relegating someone to a narrow category or box, he says, diminishes that person and in the process only widens the gulf between individuals and groups.

“I don’t think they are things that exist on their own. I don’t think people are born heterosexist or are racist or Christian. We are taught these positions, we are taught these ideologies, and we reinforce them in our social context in such discreet ways that we’re formed and shaped into opinions and ideas long before we understand that’s what has happened to us.

“Nobody can be plugged comfortably into one of these slots. It ain’t that damn simple. It never has been that simple. It’s a very complex thing.”

The film unabashedly “goes there” by unearthing the fear and anger alternative lifestyles generate, from gay revelations to interracial affairs to wigger mainfestations.

“Society paints a picture of what it wants to see and some people just don’t want to see certain things,” says de Patri (Patrick).

Overcoming these barriers, in Akintunde’s view, starts with recognizing them for what they are and how complicit we are in maintaining them.

“The thing I want to get across to people is that it’s all of our problem. Even if you think you’re just a victim, you’re not, you are a participant. It’s not a white problem, and it’s not a black problem, and it’s not a gay problem. It is a human problem.”

Akintunde enjoys the canvass film provides for expressing multi-layered themes.

“I’m very attracted to film as a way of telling that story because I think it allows you more complexity.”

Wigger marks the beginning for what he hopes is a string of films, but for now, he says, “it’s the fruition of my life’s work.” He’s justifiably proud the film’s getting seen.

“For an independent filmmaker to even get a film to run continuously anywhere for any length of time is an extraordinary achievement, and I got that to happen.”

The exhibition schedule is being revised as new screening opportunities surface.

“I had this carefully laid out plan, man, with absolute linearity, and instead things are happening in the moment.”

He says the film’s well received wherever it plays and is invited back in some cases for additional screenings, including Las Vegas and Birmingham.

“Obviously, I would love to see the movie in an even larger roll out and I think that that is happening,” he says. “I didn’t plan that Edge Theaters was going to pick up the movie. I didn’t plan these people in Vegas and Birmingham would want me to come back. I’m going to go with what happens in that moment and just enjoy it. I’m sort of like riding the wave.”

He says there’s been preliminary talk about Rave Theaters pickiing up Wigger. He’s also following up a lead about potential interest from BET in acquiring the film for network broadcast. Wigger will eventually go to Blu-Ray and DVD.

“I am still seeking a distribution deal.”

Considering its small marketing budget, he’s pleased with the film’s performance.

“We sell out the house wherever we play. I’m not making a killing, but certainly making back the money invested to bring the movie to these theaters. I have a real job, so for me it’s not so pressing my movie makes a lot of money, Of course, I want it to make money if for no other reason then to allow me to make more films.”

His unpublished novel, Waiting for the Sissy Killer, is the basis for a new feature he’s planning. The partly autobiographical story concerns a young black man trying to cope with identity issues in the 1960s South. Akintunde hopes to begin pre-production in the fall. He plans shooting the project in his native Alabama.

Omaha rapper ASO headlines the 6:30 p.m. Wigger pre-show at Twin Creek Cinema. Performing at the Blue Martini after-party is co-composer Andre Mieux.

Tickets are $20 for the screening, pre-show and party and available at http://www.WiggerThe Film.com, Youngblood’s Barber Shop, Loves Jazz & Arts Center and Twin Creek.

Related articles

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Rich Music History Long Untold is Revealed and Celebrated at the Omaha Black Music Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Rev. Everett Reynolds Gave Voice to the Voiceless (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Luigi’s Legacy, The Late Omaha Jazz Artist Luigi Waites Fondly Remembered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Get Crackin’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Film Dude, Nik Fackler, Goes His Own Way Again, this Time to Nepal and Gabon (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Vincent Alston’s Indie Film Debut, ‘For Love of Amy,’ is Black and White and Love All Over (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

-

July 21, 2011 at 12:18 pmSize Matters: The Return of Alexander Payne, Not that He was Ever Gone « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 21, 2011 at 12:23 pm‘Every day I’m not directing, I feel like I die a little,’ Alexander Payne: After a Period Largely Producing-Writing Other People’s Projects, the Filmmaker Sets His Sights on His Next Feature « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 21, 2011 at 12:43 pmWhen Omaha’s North 24th Street Brought Together Jews and Blacks in a Melting Pot Marketplace that is No More « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 21, 2011 at 2:15 pmOmaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 21, 2011 at 5:36 pmOnce More With Feeling, Loves Jazz & Arts Center Back from Hiatus « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 22, 2011 at 11:54 amMartin Landau and Nik Fackler Discuss Working Together on ‘Lovely, Still,’ and Why They Believe So Strongly in Each Other and in the New Film « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 22, 2011 at 9:36 pmGabrielle Union, A Star is Born « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 23, 2011 at 11:39 amWhen Boys Town Became the Center of the Film World « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 23, 2011 at 11:53 am‘Lovely, Still,’ that Rare Film Depicting Seniors in All Their Humanity, Earns Writer-Director Nik Fackler an Independent Spirit Award Nomination for Best First Screenplay « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 23, 2011 at 12:33 pmComing to America: The Immigrant-Refugee Mosaic Unfolds in New Ways and in Old Ways In Omaha « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 23, 2011 at 12:38 pmGood Shepherds of North Omaha: Ministers and Churches Making a Difference in Area of Great Need « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 23, 2011 at 12:41 pmNative Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

July 23, 2011 at 4:55 pmKooky Swoosie: Actress Swoosie Kurtz Conquers Broadway, Film, Television « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

August 11, 2011 at 1:48 pmOverarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

August 17, 2011 at 10:59 amThe Film Dude, Nik Fackler, Goes His Own Way Again, this Time to Nepal and Gabon « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

August 20, 2011 at 1:21 pmLifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

August 22, 2011 at 12:08 pmFilmmaker Nik Fackler’s Magic Realism Reaches the Big Screen in ‘Lovely, Still’ « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

August 28, 2011 at 3:24 pmSoon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

August 29, 2011 at 12:24 pmA Filming We Will Go: Gail Levin Follows Her Passion « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

September 16, 2011 at 8:29 pmEveryone’s Welcome at Table Talk, Where Food for Thought and Sustainable Race Relations Happen Over Breaking Bread Together « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

October 5, 2011 at 6:06 am‘A Time for Burning,’ Academy Award-Nominated Documentary Made in Omaha Captured a Church and Community’s Struggle with Racism « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

November 27, 2011 at 1:22 pmOmaha’s Film Reckoning Arrives in the Form of Film Streams, the City’s First Full-Fledged Art Cinema « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

December 26, 2011 at 11:00 pm‘Lovely, Still’ is that Rare Film Depicting Seniors in All Their Humanity « Leo Adam Biga's Blog

-

February 26, 2019 at 2:50 pmCommemorating Black History Month – Links to North Omaha stories (Part III of four-part series) | Leo Adam Biga's My Inside Stories