Archive

Jesuit photojournalist Don Doll of Creighton University documents the global human condition – one person, one image at a time

Supremely talented photojournalist Don Doll, a Jesuit at Creighton University in Omaha, has been documenting the human condition around the world for five decades, shooting assignments for national magazines and for the Society of Jesus. He’s also a highly respected educator and benevolent mentor. The handful of times I have communicated with him over the years invariably finds him just returned from or prepping for his next jaunt to some faraway spot for his work. Now in his 70s, he has more than kept up with the technological revolution, he’s been on the leading edge of it in his own field, where he long ago went all digital and began practicing the much buzzed about convergence journalism that now routinely sees him file assignments in stills and video and for print, broadcast, and Web applications. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is from a few years ago and is one of a few pieces I’ve done on him and his work that I’m posting on this blog.

Jesuit photojournalist Don Doll of Creighton University documents the global human condition – one person, one image at a time

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

When noted photojournalist Don Doll leaves Omaha on assignment, he generally goes to document the travails of poor indigenous peoples in some Third World nation and what his fellow Jesuits do to help alleviate their misery. The all-digital artist shoots both stills and video. Last spring the Creighton University journalism professor, named 2006 “Artist of the Year” (in Nebraska) by the Governor’s Arts Awards, reported on peasant conditions in Ecuador and Colombia with writer-photographer Brad Reynolds, whom he’s collaborated with for National Geographic stories.

Always the teacher, Doll will share his expertise in a Saturday Joslyn Art Museum class from 9 a.m to noon in conjunction with the Edward Weston exhibit. His work can currently be seen at: the Boone County Bank in Albion, Neb., where photos he shot along the historic Lewis & Clark trail are on display; and the Sioux City (Iowa) Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center, where his Vision Quest, 76 images of men, women and sacred sites of the Sioux Nation, shows now through August. His work is included in the permanent collection of the Joslyn, among other museums.

Many of the images he’s filed in recent years chronicle the work of the Jesuit Refugee Service, which ministers to exiles around the world. Doll’s traveled to many JRS sites. He’s captured the human toll exacted by land mines in Angola and Bosnia and the wrecked lives left behind by civil strife in Sri Lanka. He returned to Sri Lanka again last year to record the devastation of the tsunami and efforts by Jesuit Relief Service to aid families. He’s borne witness in Cambodia, Belize, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador and other remote locales. In 2005 he went to Uganda, where his words and photos revealed the “terrible” atrocities visited upon the Night Commuters of Gulu by the Lord’s Resistance Army. Doll estimates 15 million people are displaced from their homes by the war and the LRA. The human rights crisis there is but a small sample of a global problem.

“We don’t even know how many refugees there are in the world,” he said. “There’s probably 20 million internally displaced people and another 20 million who have been forced to leave their countries. I go to these terrible places in the world and try to tell the stories of people who have no other way to have their stories told.”

Making images of hard realities has “an effect” on him. “What does it do to you to photograph in these situations? I think it does something irreparable,” he said. “I mean, you carry those people inside all the time. It makes you aware of how poor people are and what awful things they go through.”

Even amid the horror of lost limbs and lives, hunger, torture, fear, there’s hope. He recalled an El Salvadorian woman who recounted how gunmen killed her daughter and four sons, yet declared, “‘I have to forgive them because I want God to forgive me.’ Well, the tears started coming down my eyes,” he said. “Here’s this poor, unlettered woman who lost five of her children in the El Salvador war and she’s saying, ‘I forgive them.’ Oh, my God, the insights the poor have.”

Balance for him comes in the form of the humanitarian work he sees Jesuits do.

“I try to tell what Jesuits are doing around the world in their work with the poorest of the poor. Not many people know this story of Jesuits in 50 different countries helping refugees. I’m so proud of being a Jesuit. I’m so impressed by these men,” said Doll, who celebrated 50 years as a Jesuit in 2005.

Two colleagues exemplify the order’s missionary work. One, Fr. Tony Wach, is the former rector at Omaha Creighton Prep. Wach aids refugees in Uganda, where he hopes to start a primary school and a secondary school and provide campus ministry for a nearby university. Doll tells his story in a new Jesuit Journeys magazine article titled “Fr. Tony’s Dream.” “He’s amazing,” Doll said.

The other priest, the late Fr. Jon Cortina, built the refugee town of Guarjila in El Salvador and began a program, Pro-Busqueda, to reunite war-displaced children with their families. Doll profiled his friend and ex-classmate on a “Nightline” special. Cortina educated many, even Archbishop Oscar Romero, to the plight of the poor. “Jon used to say, ‘We have the privilege of working with the poorest of the poor to help them.’ That’s what he loved about working up in Guarjila,” Doll said. “He loved those people and they loved him. He really lived the idea of liberation theology.”

Doll came to photography in the late 1950s-early 1960s as a young priest on the Rosebud (South Dakota) Sioux reservation, “where,” he said, “I discovered how to teach.” He said the experience of living and working with Native Americans, whom he made the subjects of two photo books, Crying for a Vision and Vision Quest, “changed my life. There’s something wonderful about being in another culture, being a minority and experiencing the values. It gives you a different perspective on your own culture because it enables you to see in a kind of bas relief your own cultural values and you can either recommit to them or reject them.”

The new values he’s assimilated give him a new understanding of family. “The whole kinship is a really beautiful thing about the Lakota people and how they hold one another in a very close relationship. That’s what you don’t see when you drive through ‘a rez,’ past a tar paper shack surrounded by cars that won’t run — you don’t see the powerful, beautiful relationships inside.”

Doll, who owns a tribal name given him by the Lakota Sioux, maintains ties with Native Americans, photographing an annual Red Cloud Indian School calendar featuring tribal children in traditional dress and mentoring students off ‘the rez’ at Creighton, where he’s proud of the school’s significant native population. He’s proud, too, of native students who’ve gone on to win major awards and jobs.

As much as he enjoys teaching, the pull of far away is always there. “I love to travel. My passion is to make pictures and to document visually what’s going on in the world,” he said. There are many places yet to visit. “I haven’t been to Russia, nor China, nor Australia, but I’ll get there.” His rich Jesuit journey continues.

Check out Doll’s work on his website magis.creighton.edu.

Related articles

- Spain indicts Salvadorans for 1989 Jesuit slayings (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Jesuit Block and Estancias of Córdoba (nty2010.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Address by Cuban Archbishop Jaime Ortega Sounds Hopeful Message that Repression in Cuba is Lifting (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Documents Provide Key Evidence in Jesuit Case Arrest Warrant (nsarchive.wordpress.com)

Chef Mike Does a Rebirth at the Community Cafe

Mike Whitner is one of several small business owners fighting the good fight by trying to inject some new commerce into the economically depressed northeast Omaha community. His Chef’s Mike Community Cafe is the type of going concern the district desperately needs but is woefully lacking. As with anybody, he has a story. Specifically, there’s a story behind how and why he became a chef and located his business in the heart of an area with great, though as yet unrealized promise, a situation that’s defined the area since its decline in the 1960s and ’70s. My story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) appeared shortly after Chef Mike opened his place. The good news is he’s still in business and the area is targeted for massive redevelopment. The bad news is that much of that development is still some years away. But every little anchor and magnet business like his can make a difference, especially if there becomes a critical mass of them.

Chef Mike Does a Rebirth at the Community Cafe

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.threader.com)

“I’m doing a rebirth,” said Mike Whitner, a.k.a. Chef Mike, as he pointed to the colorful sidewalk/window signs outside his Community Cafe in the Family Housing Advisory Services building at 24th and Lake in north Omaha. “I’m taking what I learned from my roots and putting it in like a nouvelle style kind of soul food. I keep it traditional, but I add the new wave in it, like using a lot of smoked turkey in my greens (instead of ham hocks), where it’s going to be healthy for you.”

A solid block of a man who brightens his white chef’s smock with Pollock splattered pants and jaunty berets, Whitner grew up in a rough section of far northeast Omaha’s “Flatlands.” He ran with a gang. He learned to defend himself. As the youngest of seven siblings he spent a lot of time watching his mother cook. He paid close attention. He’ll tell you the secret to soul food is made-from-scratch cooking whose deeply imbued flavors build in stages, over time.

“It’s a process,” he said. One that can’t be rushed. No shortcuts please.

Another “mentor” is Charles Hall, owner/head cook of the now defunct Fair Deal Cafe on North 24th Street. Whitner’s smothered pork steak is a homage to Hall’s classic smothered pork chop.

“I slow cook it like he used to,” Whitner said. “I cook it in its juices with peppers and onions. When you do it right, it just melts in your mouth, baby.”

As a kid Whitner earned extra money making sandwiches/dinners and hawking them to working men on the north side. Before becoming a chef though, he had some living to do. He played college and semi-pro football, bounced at clubs, provided personal security to clients and collected for others. Once, a guy pulled a gun and shot him. A bullet grazed his head. He still managed to break the shooter’s wrist down, wrest the gun away and beat him with it.

Incidents like these convinced him “it was time to grow up and get away from all that and stop taking care of other people’s business. My mother slept better.”

He got a taste of the restaurant game working at Boston Sea Party and L and N Seafood Grill. A move to Denver in the early 1990s launched him on his career. He learned the trade at the famed Wynkoop Brewing Company, which sponsored his training in the Chefs de Cuisine Association. Working chef’s license in hand, he helped Wynkoop become an anchor of the Mile High City’s trendy LoDo district.

Back home by the mid ‘90s, he entered the Omaha catering scene. He was on the team that opened Rick’s Boatyard Cafe. A parting of the ways found him catering again, this time out of trucks doing a tidy trade on the streets. When the spot he’s in now came open, he went after it.

“One of the promises I made when I became a chef,” he said, “was to bring everything I learned back to the Flatlands. I wanted to be here.”

His fusion of soul with gourmet adds new twists to old favs: sauteed baby bay shrimp with collard greens; roast beef with a demi-glace or mirepoix-based sauce; and jalapeno cheddar corn bread. Every day he does theme dishes — from blackened beef or fish to pasta to tacos to soul food staples to whole catfish filets. He has his signature Black Angus dogs, reubens, gyros and Philly steak and cheese. Some items, like his sweet potatoes, are from his own garden. He buys from local growers.

Open weekdays for breakfast, when you can get grits and biscuits, and lunch, most meals there run well under $6. The one day he’s open late, Fridays, he offers a prime rib or salmon dinner for $13, with live jazz by Hopie Bronson. The cafe’s “transformed” then into an intimate club with low lights, linen table cloths, votive candles. There’s free parking in an adjacent lighted lot.

For Whitner, who still has his own catering biz, his place is a symbol of what he sees as North 24th’s rebirth.

“This area was rich in jazz and blues. In those days businesses were booming. Everybody was coming down here enjoying 24th Street. That’s what I want again,” he said.

It’s why his menu is a melange of old and new.

“I want to represent where I come from,” he said of his soul food roots. But, he added, “you gotta mix it up. It’s an area that’s been heavy with soul food places. You can’t eat soul food every day. It’s not good for you. You gotta give this area food it’s never had before…that’s different. Folks love being able to have that kind of cuisine down here.”

Business isn’t as brisk as he’d like, but he’s set on staying to help spark a renaissance.

“Eventually this area is going to be the educational, arts, music district” of north Omaha, he said. “That’s where’s it’s going. You can feel it. When you get the jazz and blues down here you can feel it coming. It’s coming for sure.”

The Community Cafe, 2401 Lake St., is open Monday through Friday, 7:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. Breakfast from 7:30 to 11 a.m. and lunch then on. Friday dinners with live jazz from 7 to 11 p.m. For details and take out orders, call 964-2037.

Related articles

- Big Mama’s Keeps It Real, A Soul Food Sanctuary in Omaha: As Seen on ‘Diners, Drive-ins and Dives’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A. Marino Grocery Closes: An Omaha Italian Landmark Calls It Quits (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Community and Coffee at Omaha’s Perk Avenue Cafe (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- All Trussed Up with Somewhere to Go, Metropolitan Community College’s Institute for Culinary Arts Takes Another Leap Forward with its New Building on the Fort Omaha Campus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Rev. Everett Reynolds Gave Voice to the Voiceless (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Frederick Brown’s journey through art: Passage across form and passing on legacy

UPDATE: The subject of this story, artist Frederick Brown, passed away in the spring of 2012.

An Omaha cultural venue that has never enjoyed the attendance it deserves is the Loves Jazz & Arts Center. Then again, poor marketing efforts by the center help explain why so few venture to this diamond in the rough resource. The fact it’s located in a perceived high-risk, little-to-see-there area doesn’t help, but without the promotional initiative to drive people in numbers there it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of folks avoiding the area like the plague. All of which is a shame because the center’s programming, while lacking full professional follow-through, has a lot to offer. An example of some very cool LJAC programs from a few years ago were workshops that noted artist Frederick Brown conducted there in conjunction with an exhibition of his work at Joslyn Art Museum. Some of Brown’s paintings of jazz and blues legends ended up on display at the center. I interviewed Brown during his Omaha visit and I think I managed capturing in print his spirit. The story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Frederick Brown’s journey through art: Passage across form and passing on legacy

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Leading contemporary American artist Frederick Brown offered a glimpse inside the ultra-cool, super-sophisticated New York salon and studio scene during a June visit to Omaha in conjunction with his current exhibition at Joslyn Art Museum. Showing through September 4, Portraits of Music I Love is a selection of Brown’s huge, ever expanding body of work devoted to jazz and blues artists under whose influence he came of age in the American avant garde movement of the 1960s and ‘70s.

The Georgia-born Brown was raised in Chicago, where he was steeped in the Delta Blues tradition that seminal figures like Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Dixon and Jimmy Reed, neighbors and friends, brought from the South. He grew up with Anthony Braxton. Later, in New York, he fell under the spell of jazz masters Ornette Coleman and Chet Baker. His intimate circle also encompassed the who’s-who of post-modern American painters, including his mentor, Willem deKooning. It was in this rarefied atmosphere of appreciation and collaboration Brown blossomed. He observed. He absorbed. He shared. The only condition for hanging with this heady crew, he said, was to “be unique — to bring something to the table.”

“At that time one of the nice things about living in an artist’s community like SoHo was that you had these people all around you who were at the top of their game and of the avant garde scene and of the aesthetic thing. I didn’t have to invent the wheel. The standard was set. Plus, right in front of me, I saw the work ethic. You could go to their studio or they could come to yours, and you could partake in whatever you wanted to partake in and discuss aesthetics at the highest level. You had all this kind of wisdom, information, feedback and back-and-forth,” he said.

Given all the time he’s spent with musicians, it’s perhaps inevitable Brown speaks in the idiom of a jazzman. That is to say he patters away in a hip, improvisational riff that sings with the eloquence of his thoughts, the musicality of his language and the richness of his associations, stringing words and ideas together like notes.

New York was the start of his being consumed with making it as an artist. “Total immersion. 24/7. Total commitment. Either I make it or die. A total spartan kind of situation,” he said, adding the artists befriending him “accepted and encouraged me.” Art is not only his inspiration but a legacy he must carry on. A set of musicians he was tight with, including Magic Sam and Earl Hooker, made him pledge long ago that after they were gone he’d preserve their heritage through his work. Then, after emerging as a bright new force in New York, his chronically troubled tonsils grew infected, but Brown had neither the insurance nor the cash to pay for an operation. He was resigned to dying when an anonymous benefactor stepped forward to foot the bill. It was 20 years before he learned his musician friends had ponied up to save his life. Ever since then, he’s felt a debt to further the art of jazz. His paintings at Joslyn represent a fraction of the music portraits he’s done as the fulfillment of that “promise.” At his 30,000-square foot studio in Carefree, Arizona he’s working on a 450-work National Portrait Gallery-curated series of jazz icons that will tour the world under the aegis of the U.S. State Department.

Jazz and blues artist Frederick J. Brown displays his painting “Stagger Lee,” in Kansas City, Mo.

Architecture was Brown’s first field, but when painting began speaking to him more deeply, he chose the life of an artist. He hit the ground running upon his 1970 arrival in New York, where he was immediately embraced for his talent, intellect and curiosity and for the fluidity of his technique and the originality of his vision.

“I’ve always had an innate ability to look at something or hear something and then do it. I could always paint in every style. If styles are languages, then I’m fluent in all of them. I never felt like any were above me or below me,” he said.

In amazingly short order, his work was exhibited in the Whitney Biennial, the Marlboro Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

He first made his mark in the realm of abstract expressionism, but always looking to stay “10 years ahead of the curve,” he changed directions to more figurative work and is often credited with helping bring back the figure in contemporary art. The small selection of his paintings at Joslyn are expressionistic figurative portraits that employ iridescent colors and bold brush strokes to evoke the singular essence and creative spark of such artists as Count Basie, Coleman Hawkins, Billy Holiday, Billy Eckstine, Bessie Smith, Dinah Washington and the late Ray Charles.

The prolific and versatile Brown is that rare artist with the ability to produce at the highest level while churning out a prodigious volume of pieces in quick succession. He’s tackled ambitious series’, massive single works, “mosaics” that fill entire rooms and themes ranging from the history of art to the Assumption of Mary. Still indefatigble at age 60, he can paint for hours without a break, as he did 13 hours straight during celebrated tours of China in the late ‘80s, and complete a fully realized work in the span of a musical cut or joint, something he’s done on countless occasions at rehearsals and recording sessions with musicians. Hanging with “the cats” at those jams, Brown does his thing and paints while they do their thing and play. Together, in harmony, each gives expression to the other.

“When you have people expressing, live, their spirit — in music, dance, poetry — these elements are cross pollinating the whole environment and gives the place another spirit and vibe and rhythm, too,” he said. “I’ve always painted very quickly. I can paint in the same rhythm and motion as the music. In fact, I can do one painting while they do one tune. So, every day doing that, doing that, for like 15 years — 30-40 paintings a day — every day, every day for all those years, you get to a certain level where it’s just like natural and you forget that it’s anything special.”

His experiences with performing and visual artists have prompted him to explore the mysteries of capturing music on canvas via color. “To hear Ed Blackwell play, it sounded like it was raining on the drums,” he said. “So, how do you translate that into color?” To get it right, Brown embarked on a study of color theories, harmonies and contrasts. “It’s like what color do you put next to another color to make that color brightest? It’s the same kind of thing you have in music. They’re all just notes. It made me have to think about this, where before it was just instinctual. Once I got it down, I didn’t have to think about it. It became subliminal again. And then I was just reacting to the sounds…and seeing the music.”

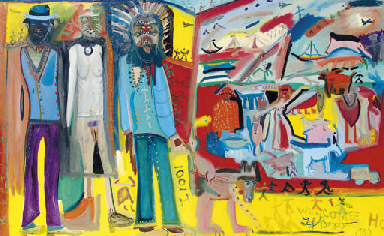

Welcome Home by Frederick Brown

In a series of cooperative workshops Brown conducted at the new Loves Jazz & Arts Center on North 24th Street, he simulated the fertile environs of the haute couture salons and loft studios he’s so familiar with. As his workshop students applied brush to canvas, bongo players beat out a driving rhythm, life models struck dance poses and Brown, turned out smartly in suit and shades, navigated the room, stopping at each easel to offer insight and encouragement to the students, who included some of Omaha’s best known artists. It was a sensual, visceral experience.

Brown’s painted this way for decades, using music as a channel for summoning his muse. “I always have music when I’m painting. I listen to a whole spectrum of music.” It’s about setting a mood for ushering in the shamanistic spirit he feels he possesses. Art as communion. “It’s like doing a jazz solo. You’re in that stream. It’s like a total zone you’re in and it just happens. You’re not conscious of it. In one sense my painting is like automatic writing,” he said. “No one can reproduce it, either.” It’s how he goes about painting his portraits of singers or musicians.

“When I’m doing this stuff I have their music playing or I have a photograph of them out,” he said. “Their spirit has to agree to come into that painting. In essence, I provide a painterly body for their spirit to inhabit. I’m a vehicle or a conduit for this information to pass through. Until the painting has a soul or a spirit, then it’s just paint on canvas. I just work on it until their spirit is satisfied,” he said. “You have to get in this like protective, almost out-of-body experience. With some people, like Johnny Hodges, you can express everything about them very quickly and simply. Others, like (Thelonious) Monk, are more complex. But sometimes you can catch the most complex situation in the fewest strokes.

“People always say, How do you know when you’re finished? Because it won’t allow you to touch it. The thing is complete. It doesn’t need any more brush strokes.”

Brown made his Omaha workshops a vehicle for exposing participants to new “possibilities” — “pushing” artists beyond self-imposed “limits” by having them, for example, create 24 paintings in a single night. He also made the classes a means for imbuing the Loves Center, whose mission is to be a venue where all the arts meet, with a synergistic “energy” open to all forms of expression. “What it comes down to is one person expressing themselves in a certain way and being inspired by different mediums. It’s getting more people involved. It’s opening minds, just like Ornette and them did for me.”

Related articles

- When Jazz Married Art (doublelattebooks.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Yolonda Ross Takes It to the Limit (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Camille Metoyer Moten, A Singer for All Seasons (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Frederick J. Brown, Painter of Musicians, Dies at 67 (nytimes.com)

- Eddith Buis, A Life Immersed in Art (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- For Love of Art and Cinema, Danny Lee Ladely Follows His Muse (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jazz-Plena Fusion Artist Miguel Zenon Bridges Worlds of Music (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Peter Buffett Completes the Circle of Life Furthering the Legacy of Kent Bellows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Many Worlds of Science Fiction Author Robert Reed

I am consistently amazed at the talent surrounding me. Until I saw an item about Robert Reed in the local daily I had no idea that one of the preeminent science fiction authors of his time was from Omaha and still lived in the area – 50 miles away in Lincoln, Neb. I promptly sought out his work and was blown away by his gift, and soon thereafter arranged an interview with him. The resulting story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) appeared in the wake of Reed having won the Holy Grail of his profession, the Hugo Award, for his novella A Billion Eves. My very short piece hardly does the prolific justice to Reed, whose work is included in countless Best Of collections and anthologies, which is why I pine to do another story about him, hopefully one of some length. He is up for another major prize by the way, as a finalist for the Theodore Sturgeon Award for his novella, Dead Man‘s Run.

The Many Worlds of Science Fiction Author Robert Reed

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Omaha native Robert Reed’s 2007 Hugo Award-winning novella A Billion Eves imagines devices called “rippers” that punch holes in the fabric of the space-time continuum. People and places get propelled from one world to some infinity of alternate worlds. The prospect of man playing God in new edens plentiful with women proves a Pandora’s Box of male fantasy run amok. The Fathers of these frontiers may be false prophets.

Eves is a cautionary tale about staking claims in facsimile worlds that may have short life spans and be susceptible to human contamination. Better to begin with a clean slate, suggests Reed, a prolific science fiction author. Speculative musings about the fallout of using quantum mechanics as an instrument of Manifest Destiny consume Reed. He has great fun, too, with the divergent creation stories bound to be promulgated in such Instant Ready, up-for-grabs universes. Whose account of “In the beginning…” you believe depends on who you are within the tribe. History, we’re reminded, is the prerogative of the historian.

Reed, who lives in Lincoln, Neb. with his wife Leslie and their daughter Jessie, has largely survived on his writing earnings since 1987. There’ve been lean times when he’s lived off savings. But it’s never been so tight he’s thought of going back on the line at Mapes Industries in Lincoln, where he did the human automaton thing to support his habit. His fertile imagination and solid craft have paid off. His work has been called grim for envisioning horrific end-of-world scenarios and dire consequences of human folly.

“I’m astonished how little fright I have of my own imagination,” he said. “It really does baffle me that I don’t get more scared because I’m capable of thinking up things that are so awful. On any given day I can imagine the worst.”

Robert Reed

He’s heeded the dark side of his imagination since childhood. Already an avid reader as a kid, he tried writing a novel at 12 or 13 — filling spiral notebooks with violent monsters conjured from somewhere deep within. Playing with his buddies in a wooded area near his childhood home he’d concoct elaborate tales of creatures. At home he’d devise intricate maps of water worlds, drawing on his interest in biology, and create fantastic universes out of his head.

“I just don’t perceive things quite as other people do,” he said.

Years passed between his first stab at writing fiction and his taking it up again at Nebraska Wesleyan University. He’d stopped writing in the interim, but he never stopped reading and imagining. Ideas filled him.

“I would say, yes, they were working on me for years and years,” he said of all the stirrings that pricked at him.

It’s perhaps why when he did resume writing tales poured out of him. They’ve kept coming, too. He’s up to 160 stories and 11 novels. When someone finds the success Reed has — published in all the major SF anthologies and nominated for the field’s top prizes — one asks why he isn’t a household name?

“I’m pleased by my following, what there is of it, but science fiction is really a rather tiny business compared with its giant cousin, which is fantasy,” he said.

Then there’s the fact that while some Reed works have been optioned by filmmakers, none have made it to the screen. He doesn’t much seem to care. He doesn’t do book tours and he attends few SF conventions. And, unlike most successful SF writers whose work is tenaciously grounded in some consistent vision of the future, Reed is apt to apply entirely new suppositions from story to story.

“It doesn’t help build a fan base doing that. There’s many ways in which I’ve separated myself from the rest of the business and from my readers,” he said, adding one advantage to being an outsider is — “I think I often come up with fresh perspectives on old storylines.”

It’s true this avid long distance runner prefers to stay apart from the pack, but then there’s his big, loud web site, www.robertreedwriter.com, that two huge fans created and maintain. Reed said he doesn’t feel he would have won the coveted Hugo without the site’s props. A Billion Eves, which appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction, can be read there. A complete bibliography of his work is available online.

Related articles

- NPR’s New Poll: “Best Science Fiction, Fantasy Books? You Tell Us” (underwordsblog.com)

- The Joy of Alt Fiction (paulcornell.com)

- The sword is mightier than the laser gun – or is it? from Stargazer’s World (stargazersworld.com)

A. Marino Grocery closes: An Omaha Italian landmark calls it quits

One of the last of the old line ethnic grocery stores in my hometown of Omaha closed down a few years ago. The small Italian market is one my family and I shopped at quite a bit. It was the last of its kind, that is among Italian grocers. Truth be told, there are many ethnic grocers in business here today, only the owners are from the new immigrant enclaves of Latin America and Africa and Asia rather than Europe. The owner of the now defunct A. Marino Grocery, Frank Marino, inherited the business from his father. It was a throwback place little changed from back in the old days. My piece about Frank finally deciding to retire and close the place appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

On this blog you can find more stories by me related to other aspects of Omaha’s Italian-American culture, including ones on the Sons of Italy hall’s pasta feeds and the annual Santa Lucia Festival.

A. Marino Grocery closes: An Omaha Italian landmark calls it quits

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader

The final days of A. Marino Grocery at 1716 South 13th Street were akin to a wake. The first week of October saw old friends, neighbors and customers file in to say goodbye to proprietor Frank Marino, 80, whose late Sicilian immigrant father, Andrea, a sheepherder back in Carlentini, opened the Italian store in 1919.

News of the closing leaked out days before the local daily ran a story about the store’s end. As word spread Marino was deluged with business. Lines of cars awaited him when he arrived one morning. Orders poured in. He and his helpers could hardly keep up. Those who hadn’t heard were disappointed by the news. Some wondered aloud where’d they get their sausage from now on.

A Navy veteran of World War II, Marino long talked of retiring but nobody believed him. Still, decades of 50-60 hour weeks take their toll. When he got an attractive offer for the building he took it. The new owner plans to renovate the space into an interior decorating office on the main level and a residence above it.

Folks stopping by for a last visit knew the store’s passing meant the loss of a prized remnant of Omaha’s ethnic past. Housed in a two-story brick structure whose upstairs apartment the family lived in and Marino was born in, the store represented the last of the Italian grocers serving Omaha’s Little Italy. While the neighborhood’s lost most vestiges of its Italian-Czech heritage, time stood still at the small store. Its narrow aisles, vintage fixtures, wood floors, solid counters, ornate display cabinets and antique scales bespoke an earlier era.

It was a living history museum of Old World charms and ways. No sanitary gloves. Meats and cheeses comingled, but regulars figured it just added to the flavor.

An aproned Marino would often be behind the deli case in back, hovering over the butcher’s block to cut, season, grind and encase choice cuts of beef for the popular sausage he made. He sold hundreds of pounds a week. He carried a full line of imported foods. Parmigiano reggiano, romano, provolone, mozzarella and fresh ricotta cheese. Prosciutto, mortadella, salami, capicolla and pepperoni. Various olives — plain or marinated. Meatballs. Homemade ravioli and other stuffed pastas. Canned tomatoes, packaged pastas, assorted peppers, et cetera. At Christmas he sold specialty candies and baccala, a salted cod used in Italian holiday dishes.

Marino rang up your purchases on an old-style cash register and engaged you in crackle barrel conversation from behind the massive front counter his father had made to order in 1932. Behind the counter, whose built-in drawers stored 20-pound cases of pasta, he’d light up his trademark pipe and shoot the breeze.

“I love being here and I love being around people,” he said.

It was the same way with his father. The two worked side by side for half-a-century. They had their spats, but the disagreements always blew over. There was, after all, a business to run and people to serve. His papa taught him well.

“It’s service-oriented. You’ve got to hand-wait on everybody,” Marino said.

In some cases he waited on three generations in the same family. He enjoyed the association and interaction. “I’ll miss that. There was a lot of closeness, you know.”

Mary Cavalieri of Omaha shopped there all her life. “It’s really sad,” she said, adding she felt she was losing “a tradition” and “a friend” in the process.

Oakland, Iowa resident Anna D’Angelo was among many who came some distance to shop there. Asked what she’ll miss most, she said, “The sausage and all the Italian specialties, and Frank. He knows everybody by name. He knows what you like. Frank never needs to see my ID. It’s that personal touch you don’t get anymore.”

Omahan Leo Ferzley, an old chum of Marino’s, said, “You hate to see it go, but what do you do? Everybody will miss it. A lot of memories.”

Marino is worried what he’ll do with all his free time. He and his wife plan their first trip to Italy. “That’s all we’ve ever talked about,” he said. One man told him that if the opportunity comes, “whatever you do, don’t pass it up.”

Customers, some whose names he didn’t even know, wished him and his wife well. One wrote a $100 check for the Marinos to treat themselves to a night on the town. As Mary Cavalieri said, “He deserves some retirement time.”

No regrets.

As Marino told someone, “It’s the end of the line. 88 years we’ve been here. Since before I was born. It’s been good to us. But I’m 80-years-old. I think it’s time.” Besides, he said, “I’m wore out.”

Related articles

- Favorite Sons, Weekly Omaha Pasta Feeds at Sons of Italy Hall in, Where Else?, Little Italy (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Actress Yolonda Ross is a talent to watch

One of my favorite “discoveries” from the past decade is fellow Omaha native Yolonda Ross, a supremely talented actress whose work back here has gone largely unnoticed for some reason. I caught up with her the first time, for the story that follows, not long after her breakthrough starring role in the HBO women’s prison movie Stranger Inside brought her to the attention of the television/film industry and just before Antwone Fisher was released and her small but telling role as Cousin Nadine made an impression. She’s proved a daring artist in her choice of material and is exploring writing-directing opportunities in addition to acting gigs. My story below appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and a later profile I did on her for that same publication can also be found on this blog.

NOTE: More recently, Yolonda’s had a recurring role as Dana Lyndsey on the acclaimed HBO drama Treme. Another Omaha actor of note, John Beasley, just nabbed a recurring role on the same series. Small world.

Yolonda Ross is a talent to watch

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader

With her sweet-sassy voice, orange-tinged Afro, almond-shaped eyes, real-women-have-curves bod and cool hip-hop vibe, Yolonda Ross gets her groove-on exploring a seemingly boundless creativity.

The Omaha native left town soon after graduating Burke High School in the early 1990s to work in the New York fashion industry before carving out a career on stage and in front of the camera. This rising young film/television actress with a penchant for essaying gritty urban sistas is on the verge of break-out success between her acclaimed star turn in the 2001 HBO women’s prison drama Stranger Inside and supporting performances in two new high-profile films slated for release this winter. Due out first is Antwone Fisher, the directorial debut of Oscar-winner Denzel Washington. Next, is The United States of Leland, a project produced by Oscar-winner Kevin Spacey. She’s now looking to develop a script she wrote into a feature she would also appear in.

Whatever happens with her career, this confident woman of color has an array of artistic flavas to explore. “I like creating in a lot of ways — writing, painting, making clothes, singing, acting,” the New York resident said upon a recent swing-through Omaha to visit family. It was that way even growing-up with her three sisters. “I’ve always been into fashion. I would be up in the middle of the night making things to wear to school the next day. It’s a creative thing to be able to start and finish something and say that you made it. It’s just something I really like to do — that and interior design.” And music. “Me and all my sisters were always musical. I always liked to sing. I didn’t get really serious about it until I was in New York. A roommate who’s a producer had me cut a Billie Holiday cover.” Before long, she said, Ross had her own three-piece band and got offered a Motown demo deal. “I didn’t go for it,” she said. “They were trying to change my jazz into something else.”

New York sustains and energizes Ross. “When you’re in New York you’re always hustling, you’re always doing a variety of things to see which breaks. There’s always stuff happening and you can just literally walk into things,” she said. One gig would lead to another, making her early years there “growing and learning…not really so much struggling.” Prior to 9/11 she lived near the World Trade Center. She was in L.A. when the tragedy occured and took her time moving back. New York is where she feels “at home” again. “I like being on the street with people. I hate driving. I like walking and being a part of it. I’m a downtown person. It works for me.”

When she first went to the Big Apple, she didn’t know a soul there. Undeterred, she stayed to fulfill a long-held vow “to go to New York.” Within a few years there she transitioned from working as a buyer for trendy Soho botiques to modeling (Black Book) to fronting her own band in Greenwich Village gigs to appearing in music videos for the Beastie Boys, L.L. Cool J and Raphfael Saadiq and D’Angelo.

After honing her dramatic skills in classes, she began acting in small theater productions, appearing in recurring roles on Saturday Night Live and daytime shows and getting guest leads in TV series (a cop in New York Undercover, a beleaguered mother in Third Watch). She said she learned more about acting from singing than formal training.

“I’ve taken classes…but it was like being on stage with people you didn’t really like and saying words you didn’t really feel. When I started singing is when I understood that key of emotion and emoting through different characters. Behind everything I do is music. Now, when I do something, it’s not me anymore. I mean, you get a little bit of me with it, but I’m just the conveyor of the writer’s and director’s vision.”

Then along came the part of her young life. On the strength of her TV work, the script for Stranger came her way and after reading it Ross felt the role of Treasure Lee was meant for her.

“I thought it was amazing. I understood it so well. I knew where she was coming from and everything. I was like, I’ve got to get this part. I went in and auditioned. There were a lot of other girls there. I just did my thing and left and I got a call back. I ended up getting a call back three times. The producers flew me out to L.A., where it was like a month of auditioning, and I ended up getting it.”

Written and directed by black-lesbian filmmaker Cheryl Dunye, Stranger takes the conventions of Hollywood prison films and applies a feminist-dyke twist to them, offering a raw depiction of women’s life inside the pen. Ross portrays the troubled Lee, a desperate young woman trying to forge a bond with the mother she never knew, Brownie, a lifer and queenpin behind bars. Her work earned her the 2001 IFP Gotham Award for Breakthrough Actor, a Best Debut Performance nomination from the Independent Spirit Awards and an Outfest Screen Idol Award nomination for Best Performance By an Actress in a Lead Role. In 2001, she was named one of Variety’s “10 Actors to Watch.”

Photo credit: Jack Zeman

While never tackling a role as large or demanding as Treasure before — in one scene she endures a full nude body search and in another is pleasured with oral sex by a fellow inmate — she embraced the challenge, fully aware of just how juicy a part it was.

“To be able to do Treasure and to do everything that was in that script — I welcomed it — I really did — because I knew I had this chance that a lot of people don’t get and I wasn’t about to mess it up.”

Making the part resonate for Ross was its reality.

“Treasure, to me, was like a real person, not just a movie person. With a lot of scripts you read the characters don’t really evolve. The thing I like about Stranger is the characters aren’t one-dimensional. They’re good, strong female characters that let you see other sides.”

She said playing a profane, violent, overtly sexual woman was liberating. “The freedom to be able to get things out through her and to stretch through her was something I looked forward to. As Yolonda, I’m not going to act the way Treasure would — not that I don’t have it inside me — but I need to get those things out and use them and caress them and fine-tune them.”

Researching the role brought Ross to some California women’s prisons, where she met inmates. The film was shot at the “eerie” abandoned Cybil Brand Prison. Rehearsals lasted four weeks, which she welcomed. “You see, I’m not one of those ad-lib people. I like to know exactly what I’m doing. Sometimes, in rehearsal, little things come up and you find things. I feel once you hit it, you should leave it alone until you shoot it.”

She said filming was such a blast “I didn’t want it to end.” As for the finished film, she feels Dunye captured the truth without compromise. “It wasn’t glossed up. It didn’t get sliced up. All the emotions came through. I thought it was a great job and I’m proud of it.” The only downside to making Treasure her first lead, Ross said, is that without much of a track record behind her casting directors “didn’t know how much of it was acting and how much of it was me.”

Even though it meant playing another “bad girl,” Ross jumped at the chance to be in Fisher. The film is based on the best-selling book, The Antwone Fisher Story, in which Fisher, who adapted his own book to the screen, details his real life odyssey of childhood abandonment, foster care abuse, adult rage and — with the help of a good woman and a psychiatrist (played by Washington) — overcoming trauma to emerge a successful husband, father and artist.

Ross portrays Cousin Nadine, a foster family abuser in Fisher’s life. When she read the script, she said she doubted “if I can do this. But the negative things my character does you don’t actually see, and so once I figured that out then it was all right. I sent in my audition on tape. I was out in L.A. to do a 24 and one day I get a call on Melrose, and I’m trying to hold the reception. I’m like (to passersby), ‘OK, wait, I’ve got Denzel on the phone — walk around me. I’m not moving. I’m not going to lose this one.’ He called to say he loved it (her audition),” hiring her on the spot. “Oh, man, that was crazy.” The film was largely shot in Cleveland, where the events depicted actually took place.

Photo by Christopher Logan-

On working with Washington, she said, “He’s so focused…He knew what he wanted. He had his vision and he just did it.” With no rehearsal this time, she discovered the character of Nadine on the set. “We just did the scenes and did ‘em different ways and he used what he wanted.” Of Fisher, she said, “He is the sweetest man. Soft-spoken, low-key. His family is beautiful.” She avoided reading his book before filming “because I didn’t want to try to be exactly something that he wrote. I wanted to come to it with what I have. The crazy thing was, after reading it, my interpretation was just like the character.”

The film, which follows Fisher up to his being reunited with his biological family, is ultimately an inspirational story. “Out of what he endured in his life…all this positive has come out of it,” Ross said. She likes how the film doesn’t sensationalize the events it dramatizes but rather shows them as part of a whole. “It isn’t like a Hollywood movie even though Fox Searchlight did it. It’s like how life is. How a lot of times not much is happening but then some craziness will happen and then, like, OK, you’re back to this place.” The film, starring newcomer Derek Luke, features unknowns, which she feels works to its advantage. “Because you’re not having stars shadow the story, the story is the star. It just works beautifully.”

Besides a one-act play she’s preparing to appear in in New York, Ross awaits her next acting job. Hardly idle, she’s busy schmoozing-up a production deal for her script, which she describes as “a slice of life set in New York” dealing with the romantic entanglements of two couples.

“It’s one of those things where you’ve been with somebody for a while and somebody just comes out of nowhere and blows your mind. Is it real? Is it not? Do you jump and go off with this person or do you stay with your steady in a not so happy but safe relationship?”

She wrote it because “there just aren’t a lot of great parts out there for black women. I mean, you’re the crack head or the welfare mom or the girlfriend. It’s like you can never just stand alone and be a character. So, if there’s something I want to do and I can write it, then I might as well do that. Why wait?”

In United States, premiering at Sundance in January, Ross plays the girlfriend of Don Cheadle in a story examining the impact a death has on a community. Her part was added after principal photography wrapped. She also appears this fall on PBS in an American Film Institute short, The Taste of Dirt. Meanwhile, she’s campaigning for the role of jazz singing legend Billie Holiday. “There’s an amazing script out there I really want. It’s not at the point where there’s anybody behind it, but I’m trying to make sure I’m more than in the running when it comes to that.”

So, how does a young woman from Omaha stay real in the spotlight? “My sisters. My sisters keep me real. They won’t go run and do stuff for me. It’s like, ‘No, do it yourself.’” What’s important to her? “My family — we’re really close. My health. Paying attention to things around me and appreciating them. I’m very much an earthy kind of person.” Still, as her marquee value rises, Ross has her eyes fixed on the perks fame can bring and, for now anyway, forgoes thoughts of long term romantic attachments, saying unabashedly, “There’s things that I want, and I need to get them, and I can’t let things get in the way of that. I’m so focused on working.”

What does the 20-something crave? “A place of my own in Manhattan. A house in upstate New York. To be settled…to be able to have a little bit under my belt. I’d like to be producing movies that I would be in.”

If Fisher nets the same enthusiasm it did in September at the Toronto Film Festival, where Ross said it got a standing ovation, then hers may soon be a household name. “Exactly,” she said, delighted at the notion of being THE new one-name soul sista. “Not Diana, not Halle…Yolonda. Mmmm, hmmm. We’ll see.” Go, girl, go.

Related articles

- Yolonda Ross Takes It to the Limit (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kevyn Morrow’s Homecoming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Life is a Cabaret, the Anne Marie Kenny Story: From Omaha to Paris to Prague and Back to Omaha, with Love (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

A stitch in time builds world-class quilt collection and center-museum

Among the more impressive art venues in Nebraska I’ve visited is the International Quilt Study Center & Museum in Lincoln. Everything at the facility is done at a high level, and in fact, bespeaking its name, is done at a world-class level. That includes the design and outfitting of the building, the way the quilts are stored, handled, and displayed., and of course the magnificent quilts themselves. If you’re a quilter or quilt lover, I don’t need to explain why these objects are not only things of beauty but fascinating and illuminating. If you’re among the uninitiated or skeptics, I’m confident that upon viewing the quilts at this center you will come away with a new appreciation for the form and the craft. My story about the center for The Reader (www.thereader.com) appeared just as it was opening. It’s a must-see attraction to round out the usual tourist stops here.

This blog contains a couple other stories related to quilts and quilting: a profile of Nancy Kirk, an antique quilt expert and restorer known for and her late husband’s The Kirk Collection; and stories about John Sorensen and his The Quilted Conscience documentary.

A stitch in time builds world-class quilt collection and center-museum

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The next time you look at that quilt hanging on your wall or covering your bed, try reading it. Every quilt, you see, tells a story.

Nebraska’s newest world class arts venue, the International Quilt Study Center & Museum, opened six weekends ago in Lincoln to 1,500 visitors, including many enthusiasts from the state’s tight-knit quilting community.

Among the throng were two special guests, Robert and Ardis James, a pair of native Nebraskans who envisioned the center years ago. The New York-based couple built a fabulous collection of quilts beginning in the 1970s. Their 1996 donation of 950 quilts to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, whose College of Education and Human Sciences is the center’s academic home, led to the center’s creation in 1997. For its first decade the institution operated from cramped, shared quarters in the Home Economics building on UNL’s east campus. The museum is allied with the college’s Department of Textiles, Clothing and Design.

The makeshift accommodations proved inadequate for an organization with an ever-expanding collection and reputation. Until now the center lacked its own dedicated space for preservation, much less exhibition. Staff worked with quilts and prepared exhibits only as rooms became available. Shows had to be mounted at a succession of galleries on campus. Storage was limited. Photographing the rather large objects posed extreme difficulties.

Despite these less than ideal conditions the center’s gained cachet for its: temporary and traveling exhibits; research-publication efforts, including a collection catalogue in the works; savvy acquisitions; and major grants. It’s well-established as a must-see for scholars, historians and quilt-lovers.

The James’s articulated a goal shared by center administrators and supporters for a permanent site that addressed the physical shortcomings and maximized the institution’s already proven strengths. The couple next had to convince UNL officials. With a gift of $5 million from the James’s and the contributions of hundreds more donors, many of the $50 or $100 variety, the dream of a new facility has turned reality in little more than a decade.

Now in their 80s, the James’s were prominent among the special guests at the Mar. 30 dedication ceremony and Mar. 31 donor events. The couple have a unique appreciation for how far the center’s come in such a short time.

“It’s unbelievable that we have this impressive building built. We feel good about what we’ve done but it couldn’t have been done without the university. We’re proud to be able to work with the university. It was not easy for them to make this commitment,” Robert James said by phone from New York.

When he and his wife began seeking a permanent home for their collection in the 1990s they met with many museums-galleries but, he said, “none had a concept of what needed to be done other than the university.” The preservation, study and collection of quilts, he said, is a never ending process that requires dedicated resources. The couple would not entrust their quilts to anyone until $3 million was pledged toward an endowment for the collection’s ongoing care, research and growth. When UNL fulfilled that stipulation it signaled to the couple they’d found the caretakers they’d long sought. A deal was struck and the result is what Art and Antiques magazine recently termed one of America’s “top 100 treasures.”

For center director Patricia Crews the new facility culminates a journey that’s seen her put Nebraska’s love affair with quilts on the map. Her work with the Nebraska Quilt Project, organized by the Lincoln Quilters Guild in the 1980s, led to her authoring Nebraska Quilts and Quiltmakers, an acclaimed book that caught the attention of the James’s and set in motion their support.

“Patricia put together a wonderful compendium on Nebraska quilts. Practically every state’s done a book like that but hers was clearly the best,” James said. “Pat also has something that’s very important when you do something like this — an expertise in textile conservation.”

He admires her ability to garner support, adding, “she’s gotten some great gifts from not just us but the Getty (Foundation) and others.” He said Crews has surrounded herself with a fine staff and attracted a large corps of volunteers. Trained docents lead guided tours at the museum.

While the center’s long offered guided tours and education programs, such as lectures and symposia, they were off site. Now everything’s under one roof.

“It is absolutely fabulous to be in this stunning new facility,” Crews said, “and to have dedicated space for everything — exhibition, study and care of the collection. It’s a huge difference in our efficiency of operation, a huge expansion in our capacity to do research and to care for the collection”

The new building’s amenities include: a state-of-the-art, climate controlled conservation work room and a large storage vault with automated storage systems; an education seminar room; a photography studio that resembles a surgical suite; and an interactive virtual gallery that enables visitors to remotely view the collection as well as record their own quilt stories and histories. Visitors can also access the collection online.

Virtual access is key as only a fraction of the holdings — 40 to 60 quilts — can be physically displayed at any one time due to the fragility of textiles, which must be rested at regular intervals.

Unquestionably, the center’s 2,300-plus quilts hailing from 24 countries and spanning four centuries is the star attraction. The quilts range fromworks made for decorative or utilitarian purposes to those made by studio artists for gallery display.

The two inaugural exhibitions showcase the breadth and depth of the collection and the elements that tie quilts together. Quilts in Common explores the art form in groupings of three, showing how quiltmakers have used similar patterns across eras and cultures. The quilts are juxtaposed with other art objects of similar designs. Nancy Crow: Cloth, Culture, Context showcases works by this acclaimed American quilter drawn from the center’s own collection and other sources.

As sublime as the quilts are the Robert A.M. Stern Architects of New York-designed building is a jewel, too. The structure’s organic shapes and materials express quilt characteristics. The bowed steel and glass east face features curvaceous, soft-lines representing the sensuous, sweeping flow of unfurled fabric. The facade’s cross-hatched windows articulate quilts’ complex patterns. The pale, patterned brick that completes the exterior continues the artesian craft motif.

The interior accentuates what senior architect Robert Stern calls the building’s glass lantern and brick-clad box structure. The box is the central, working core of the museum where quilts are stored and cared for, where the staff office, et cetera. The lantern is the transparent facade that acts as a reflective window to the outside world, opening up an otherwise shuttered, compact interior. A winding terrazzo staircase follows the contours of the undulating front, climbing from the ground floor to a grand second story reception space whose window panels overlook the landscaped plaza below. This magisterial gathering area leads into the galleries, thus serving as a bridge to the treasures on display.

As light is the enemy of quilts, a series of filters, scrims and screens are in place to dampen the ilumination entering the adjoining galleries. The Green building’s already subdued natural and artificial light is further lensed down as visitors wend their way by elevator or stairs from the ground floor to the galleries upstairs.

The spacious galleries, with their white walls and maplewood floors, offer a blank slate for the explosion of colors, patterns and textures that jump out at visitors.

Crews said the museum is a suitable embodiment of the elevated place quilts now hold in the art world.

“It is true that it is only since the 1970s that there has been a growing appreciation for the quilt as an art form and this building certainly is an expression of the greater appreciation that many people have for quilts.”

“There is a connection that almost everyone feels to a quilt,” she said, whether inherited or gifted, covering a bed or adorning a wall. She said visitors are bound to find some quilt at the museum they feel “a connection to because it reminds them of one in their family’s history. One of the wonderful things a visit here can do is to inspire visitors to delve deeper into learning more about themselves and their families and then, in turn, their past.”

It only takes some interest to learn what quilts have to say.

The center, located at 1523 N. 33rd St., is open every Tuesday through Saturday, from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.m and Sundays from 1 to 4 p.m. Admission is $5 for adults, $3 for youths 5 to 18 and free for children under five. For details, call 402-472-6549 or visit www.quiltstudy.org.

Related articles

- Unravelling secrets in crafty stitchwork (telegraph.co.uk)

- Caring for the Lost Heroes Art Quilt (blogsouthwest.com)

- Quilt National 2011, Dairy Barn Arts Center, Athens, Ohio Now – September 5th, 2011 (aboutquilts.wordpress.com)

- Summer Quilt Whisperer 101 Class Offered! ” Feathered Fibers (dreamzhappenquiltz.wordpress.com)

- Stitching sky (stitchinglife2.wordpress.com)

Nomad Lounge, An Oasis for Creative Class Nomads

Nick Hudson is one of several Omaha transplants who have come here from other places in recent years and energized the creative-cultural scene. One of his many ventures in Omaha is Nomad Lounge, which caters to the creative class through a forward-thinking aesthetic and entrepreneurial bent and schedule of events. This Metro Magazine (www.spiritofomaha.com) piece gives a flavor for Hudson and why Nomad is an apt name for him and his endeavor. Three spin-off ventures from Nomad that Hudson has a major hand in are Omaha Fashion Week, Omaha Fashion Magazine, and the Halo Institute. You can find some of my Omaha Fashion Week and Omaha Fashion Magazine writing on this blog. And look for more stories by me about Nick Hudson and his wife and fellow entrepreneur Brook Hudson.

Nomad Lounge, An Oasis for Creative Class Nomads

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Metro Magazine (www.spiritofomaha.com)

Another side of Omaha’s new cosmopolitan face can be found at Nomad Lounge, 1013 Jones St. in the historic Ford Warehouse Building. The chic, high-concept, community-oriented salon captures the creative class trade. Tucked under the Old Market’s 10th St. bridge, Nomad enjoys being a word-of-mouth hideaway in a shout-out culture. No overt signs tout it. The name’s stenciled in small letters in the windows and subtly integrated into the building’s stone and brick face.

The glow from decorative red lights at night are about the only tip-off for the lively goings-on inside. That, and the sounds of pulsating music, clanking glasses and buzzing voices leaking outdoors and the stream of people filing in and out.

Otherwise, you must be in-the-know about this proper gathering spot for sophisticated, well-traveled folks whose interests run to the eclectic. It’s all an expression of majority owner Nick Hudson, a trendy international entrepreneur and world citizen who divides his time between Omaha and France for his primary business, Excelsior Beauty. Nomad is, in fact, Hudson’s nickname and way of life. The Cambridge-educated native Brit landed in Omaha in 2005 in pursuit of a woman. While that whirlwind romance faded he fell in love with the town and stayed on. He’s impressed by what he’s found here.

“I’m blown away by what an amazingly creative, enterprising, interesting community Omaha is,” he said. He opened Excelsior here that same year — also maintaining a Paris office — and then launched his night spot in late 2006.

If you wonder why a beauty-fashion industry maven who’s been everywhere and seen everything would do start-up enterprises in middle America when he could base them in some exotic capital, you must understand that for Hudson the world is flat. Looking for an intersection where like-minded nomads from every direction can engage each other he opted for Omaha’s “great feeling, great energy.”

“We’re all nomadic, were all on this journey,” he said, “but there are times when nomads come together, bringing in different experiences to one central place and sharing ideas in that community. And that’s exactly what it is here. Nomad’s actually about a lifestyle brand and Nomad Lounge is just the event space and play space where that brand comes to life for the experimental things we do.”

He along with partners Charles Hull and Clint! Runge of Archrival, a hot Lincoln, Neb. branding-marketing firm, and Tom Allisma, a noted local architect who’s designed some of Omaha’s cutting-edge bars-eateries, view Nomad as a physical extension of today’s plugged-in, online social networking sites. Their laidback venture for the creative-interactive set is part bar, part art gallery, part live performance space, part small business incubator, part collaborative for facilitating meeting-brainstorming-partnering.

“That whole connecting people, networking piece is really exciting to us because it’s not just being an empty space for events, we’re actually playing an active role in helping the creative community continue to grow,” said Hudson.

Nick Hudson

Social entrepreneurship is a major focus. Nomad helps link individuals, groups and businesses together. “It’s a very interesting trend that’s going to be a big buzz word,” Hudson said. “Nomad is a social enterprise. It’s all about investing in and increasing the social capital of the community, creating networks, fostering creativity. My biggest source of passion is helping people achieve their potential.”

“He’s definitely done that for me,” said Nomad general manager-events planner Rachel Richards. “He’s seen my passion in event planning and he’s opened doors I never thought I’d get through.”

The Omaha native was first hired by Hudson to coordinate Nomad’s special events through her Rachel Richards Events business. She’s since come on board as a key staffer. With Hudson’s encouragement she organized Nomad’s inaugural Omaha Fashion Week last winter, a full-blown, first-class model runway show featuring works by dozens of local designers. “That was always a dream of mine,” she said.

Under the Nomad Collective banner, Hudson said, “the number of social entrepreneurs and small enterprises and venture capitalist things that are coming from this space from the networking here is just phenomenal. Increasingly that’s going beyond this space into start-up businesses and all sorts of things.” Nomad, he said, acts as “a greenhouse for ideas and businesses to expand and grow.”

Nomad encourages interplay. Massive cottonwood posts segment the gridded space into 15 semi-private cabanas whose leather chairs and sofas and built-in wood benches seat 8 to 20 guests. Velvet curtains drape the cabanas. It’s all conducive to relaxation and conversation. Two tiny galleries display works by local artists.

There’s a small stage and dance floor. The muted, well-stocked bar features international drink menus. Video screens and audio speakers hang here and there, adding techno touches that contrast with the worn wood floors, the rough-hewn brick walls and the exposed pipes, vents and tubes in the open rafters overhead. It all makes for an Old World meets New World mystique done over in earth tones.

Hudson embraces Nomad’s flexibility as it constantly evolves, reinventing itself. In accommodating everything from birthdays/bachelorettes to release/launch parties to big sit-down dinners to more intimate, casual gatherings to social enterprise fairs and presenting everything from sculptures and paintings to live bands and theater shows to video projection, it’s liable to look different every time you visit. Whatever the occasion, art, design, music and fashion are in vogue and celebrated.

Dressed-up or dressed-down, you’re in synch with Nomad’s positive, chic vibe.

“It’s this whole thing about being premium without being pretentious,” said Hudson. “Nomad is stylish, it’s trendy, it’s great quality. All our drinks are very carefully selected. But it’s still made affordable.”

In addition to staging five annual premiere events bearing the Nomad brand, the venue hosts another 90-100 events a year. Richards offers design ideas to organizations using the space and matches groups with artists and other creative types to help make doings more dynamic, more stand-alone, more happening.

Clearly, Nomad targets the Facebook generation but not exclusively. Indeed, Hudson and Richards say part of Nomad’s charm is the wide age range it attracts, from 20-somethings to middle-agers and beyond.

Nomad fits into the mosaic of the Old Market, where the heart of the creative community lives and works and where a diverse crowd mixes. Within a block of Nomad are The Kaneko, the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, the Blue Barn Theatre and any number of galleries, artist studios, fine restaurants and posh shops. Nomad’s a port of call in the Market’s rich cultural scene.

“It’s such a great creative community. We want to help make our little contribution to that and keep building on all the great things going on,” said Hudson.

Besides being a destination for urban adventurers looking to do social networking or conducting business or celebrating a special occasion or just hanging out, Nomad’s a site for charitable fundraisers. Hudson and Richards want to do more of what he calls “positive interventions” with nonprofits like Siena/Francis House. Last year Nomad approached the shelter with the idea for Concrete Conscience, which placed cameras in the hands of dozens of homeless clients for them to document their lives. Professional photographers lent assistance. The resulting images were displayed and sold, with proceeds going to Siena/Francis.

New, on Wednesday nights, is Nomad University, which allows guests to learn crafts from experts, whether mixing cocktails or DJing or practically anything else. It’s a chance for instructors to market their skills and for students to try new things, all consistent with a philosophy Hudson and Richards ascribe to that characterizes the Nomad experience: Do what you love and do it with passion.

Related articles

- A Change is Gonna Come, the GBT Academy in Omaha Undergoes Revival in the Wake of Fire (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Grows in New Directions (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Where Hope Lives, Hope Center for Kids in North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Social Media Fashion PR: Geek Chic – Fashion Nomad App For Travelling Fashionistas (piercemattiepublicrelations.com)

- Alice’s Wonderland, Former InStyle Accessories Editor Alice Kim Brings NYC Style Sense to Omaha’s Trocadero (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Separated Siblings from Puerto Rico Reunited in Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)