What makes someone a hero? Does it require exposing oneself to physical danger? Or is it taking an action, any action, that no else is willing or able to take in order to save a life or at least remove someone from harm’s way? If you agree, as I do, that doing the right thing, whether there’s the threat of bodily harm attached or not, constitutes heroism, then the late Grand Island, Neb. businessman David Kaufmann qualifies. He repeatedly signed letters of affidavit that allowed family members to leave Nazi Germany for America and freedom. By acting as their sponsor, he not only helped give them new lives here, he essentially saved their lives by getting them away from the clutch of Nazis bent on The Final Solution. When Omaha authors Bill Ramsey and Betty Shrier collaborated on a book about Kaufmann titled Doorway to Freedom I ended up writing several stories about Kaufmann and his actions. Two of those stories follow. These are among some two dozen Holocaust-related articles I’ve written over the years, several of which, including profiles of survivors, can be found on this blog.

Holocaust rescue mission undertaken by immigrant Nebraskan comes to light:

How David Kaufmann saved hundreds of family members from Nazi Germany

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Nebraska Life Magazine

Grand Island, Neb. Jewish German emigre David Kaufmann is recalled as a Holocaust hero today despite the fact he never fired a shot, never hid anyone, never bribed officials, never forged documents. What he did do was sign letters of affidavit from 1936 to the start of World War II that enabled scores of famly members to escape genocide in Nazi Germany. With strokes of a pen this private citizen did more than some entire states in responding to the Nazis’ systematic eradication of Jews.

As the Holocaust unfolded an ocean away, he extended a lifeline from the middle of America to endangered family in his homeland. His sponsorship booked them safe passage, thus sparing them from near certain death. What makes this rescue effort unlike others from that grim time is that this merchant-entrepeneur managed it all from the small Midwest town he adopted as his own and made his fortune in.

“Yeah, Nebraska’s one of the last places one would think of to find a guy like that,” said retired Omaha Rabbi Myer Kripke, who presided over Kaufmann’s 1969 funeral in Grand Island. After years of ill health, Kaufmann did at age 93, his rescue work little known outside his extended family.

Kaufmann undertook this humanitarian mission at the height of his success as a business-civic leader with retail, banking and movie theater interests. Known as “Mr. Grand Island,” he’s best remembered for Kaufmann’s Variety Store there, the anchor for a south-central Nebraska chain of five-and-dimes.

But he did not act alone. The first family he got out of harm’s way were cousins Isi and Feo Kahn in 1936. With his help the young couple fled Germany for America. They headed straight for Grand Island, where their daughter Dorothy Kahn Resnick was born and raised. Resnick, who lived and worked in Omaha for a time, now resides in Greeley, Col. Her father worked in Kaufmann’s store until opening a used car dealership. Her mother was a “key” confidant of Kaufmann’s in the conspiracy of hearts that evolved. She kept in touch with family abroad and fed Kaufmann new names needing affidavits of support. Feo even brought Kaufmann the forms to sign.

Anti-Semitism made life ever more restrictive for Europe’s Jews, targets of discrimination, violence, imprisonment and death. People were desperate. Official, legal channels for visas dwindled. You needed a sponsor to get out. Dorothy said her mother went back repeatedly to Uncle David, as he’s referred to out of respect, saying, “‘Here’s someone else.’ Some were very distant relations. But she told me he never questioned her. He never wanted to know who they were and how they were related. He relied on her. He trusted her. He put his faith in her that if she said it was OK, he signed it. Uncle David and my mom just did the right thing. Maybe the simplicity of it is what’s so beautiful.”

“While Mr. Kaufmann had the wherewithal to do what he did, God bless him, it never would have happened without Feo,” said family survivor Guinter Kahn. “It was Feo’s doing — her persuasion — that got his agreement to get the others over.”

Kaufmann’s aid even extended after the war to those displaced by the carnage.

No one’s sure of the exact number he rescued. How he delivered people to freedom and therefore a new lease on life is better known. Escaping the Holocaust meant somehow securing the proper paperwork, making the right connections and scraping together enough money. No easy task. Even family living abroad was no assurance of a way out. It was the rare family that had someone who could take on the legal-financial burden of sponsorship. Then there were the shameful restraints imposed by governments, including the U.S., that made obtaining visas difficult. Nationalism, isolationism and anti-Semitism ruled. Apathy, timidity, fear and appeasement closed borders, sealing the fate of millions.

Few stepped forward to offer safe harbor in this crisis. One who dared was Kaufmann. On regular visits and correspondence home this self-made man kept abreast of the worsening conditions and made a standing offer to help family leave. When Isi and Feo took him up on his offer, they became liaisons between him and asylum seekers. Not all chose to leave. Most who didn’t perished.

Kaufmann didn’t need the risk of assuming responsibility for the welfare of distant relations during the Great Depression, when riches were easily lost. Not wanting publicity for his actions, which went against the tide of official and popular sentiment to keep “foreigners” out, he carried on his campaign in near secrecy. Despite all the reasons not to get involved, he did. This unflinching sense of duty makes him a laudable figure, say Omahans Bill Ramsey and Betty Dineen Shrier, authors of a forthcoming book on Kaufmann called Out of Darkness.

In their research the pair found a handful of signed affidavits of the many they determined Kaufmann signed. The affidavits represent perhaps dozens, if not hundreds of lives Kaufmann saved. He apparently left no record of how many he aided nor any explanation of why he did it. His legacy as a rescuer went largely untold outside family circles until a couple years ago. Kaufmann rarely, if ever, spoke of it. There are no press accounts. No mention in books. No journal-diary entries. Other than a letter he wrote a family he helped flee Germany, scant documentation exists.

Related by blood or marriage, the refugees included the Kahns, the Levys and other families. Most settled outside Nebraska. The few that began their new lives in Grand Island or Omaha eventually left to live elsewhere. The only ones to stay in-state were Isi and Feo Kahn, who in later life moved from Grand Island to Omaha, and Marcel and Ilse Kahn, whose two sons were born and raised in Omaha. The two Kahn couples saw more of Uncle David than their relatives and came to know a man who loved to entertain at his comfortable stone home, which sat on well-landscaped grounds. At sit-down dinners and backyard picnics he and his second wife Madeline gave, the couple regaled visitors with tales from their world travels.

Family, for this benevolent patriarch, was everything. Wherever family settled, he kept tabs on them. Upon their arrival in America, each received a $50 check from him. His support was far from perfunctory, just as the affidavits he endorsed were far from idle strokes of the pen. As their sponsor, he was responsible for every man, woman and child listed on the documents and liable for any and all debts they incurred. As the story goes, no one abused his trust.

As if to please him, Kaufmann’s charges distinguished themselves. “We’ve not met or talked to anyone yet that wasn’t very successful. There are doctors, lawyers, researchers. I mean, they were driven by this legacy. He gave them a chance to do something with their dreams and they made the most of it,” Ramsey said.

Underscoring this rich legacy of accomplishment is the fact none of it would have been possible without Kaufmann’s intervention. “The common thread is, If it wasn’t for him. we wouldn’t be here — our lives would have been lost. And they’re eternally grateful. That’s the message that goes through the whole story. They love this man. It just comes through,” Ramsey said.

“You needed someone to sponsor you and it took someone who had the resources, and Kaufmann was a king among kings in Grand Island,” Marcel Kahn said.

Kaufmann leveraged his wealth against his faith the refugees would succeed despite limited education and few job prospects. He vouched for them. If they failed, he was obliged to bail them out. “Keep in mind, it was the 1930s, a time of dust storms and depression,” Kahn said. “And for him to take the initiative that he did to sponsor as many as he did, it was just unreal.”

In February 1938 Marcel Kahn came over at age 6 with his brother Guinter and their parents on the maiden voyage of the New Amsterdam ocean liner. Months later the former Ilse Hessel made the crossing with her parents on the same ship.

The Kahns settled in Omaha. The Hessels in Astoria, New York, where she first recalls meeting The Great Man. “There was such excitement that Uncle David was coming,” she said, adding “if the President himself” came there wouldn’t have been more anticipation. “Whenever he would come we would put on the highest level of adoration you could imagine.” The best china was laid out. A lavish meal prepared. Everyone dressed in their go-to-synagogue finest. While always gracious, Kaufmann carried an “executive” air, Marcel said, that made others defer to him in all things.

On the eve of Uncle David’s 80th birthday, in 1956, Ilse and her aunt Frieda Levy discussed how the family might express their thanks to him.

“We knew we wanted to do something to honor this man because of what he had done for us,” Ilse said. “He gave us our lives. We talked about it for a while and we came up with a Tree of Life. I found an artist who painted it.” The painting included the names of families Kaufmann rescued. Trees were planted in Israel to symbolize the gift of life they’d been given. In return, Kaufmann planted two trees in Israel for every one his family did.

To Grand Islanders, Kaufmann was a businessman-philanthropist. To his family, he was a savior. Few knew he was both.

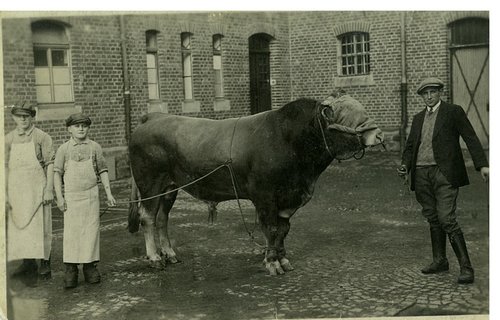

Before he was a hero, he was a dreamer. In Germany, his rural Orthodox family was in the cattle and meat business in Munsterifel, near Cologne. He left home for the city and found success as a retailer. He came to America in 1903, at age 27, with no prospects and unable to speak English. As an immigrant in New York he mastered the language and entered the retail trade. Then his path crossed with a man who changed his life — S.N. Wolbach. A native New Yorker, Wolbach followed Horatio Alger’s “Go west, young man” advice and found his pot of gold in Grand Island, where he owned a department store and bank. On a 1904 buying trip back east he visited the Abrams and Strauss store in Brooklyn, where the industriousness of a young clerk named David Kaufmann caught his eye. Wolbach convinced him his fortune lay 1,500 miles away working for him at Wolbach and Sons. Flattered, Kaufmann accepted an offer as floorwalker and window trimmer.

No sooner did he get there, than he wanted out. Ramsey and Shrier have come upon letters he exchanged with his brother in Germany in which David bemoans “the lack of pavement, the all-too frequent dust storms and the unimposing buildings.” Shrier said Kaufmann even asked his brother to find him a retail opening back in their homeland. By the time his brother wrote back saying he’d found a position for David, things had changed. “There was something about the old town that made me like it,” Kaufmann reflected years later in print. “There were no big buildings, but that doesn’t make a town. It’s the people who live in a place that make you love it. There was something about those old-timers and the ones who came after me that made me like Grand Island. There was something about the businessmen and the people…their willingness to cooperate in all worthwhile undertakings, that makes it a pleasure to work with them.”

Only a few years after his arrival, he went in business for himself, opening his store in 1906. He was a young man on the move and he’d let nothing stop him. “Some people would make a success at anything. All they need is an opportunity,” Marcel Kahn said. “I’m sure he would have been a success at just about any endeavor.”

Ramsey sees S.N. as “The Great Man model” Kaufmann aspired to. “Kaufmann was a doer and Wolbach was a doer as well,” Ramsey said. “He did a lot of charitable work. He was a well-to-do, respected person. And you get the feeling Kaufmann looked up to this man and figured maybe this is how you become a success.”

There is a perfect symmetry to the story. Just as Wolbach helped Kaufmann realize the classic immigrant-made-good success story and American Dream, Kaufmann helped his family achieve the same. The fact he brought them over at a time of peril makes it all the more poignant.

It may be, as survivor Joseph Khan surmises, “doing this good deed might not have been a big deal” to Kaufmann. “I’m not suggesting or implying it wasn’t. It was. Perhaps he was motivated to bring people over here so they could enjoy the same fruits of their labor as he did. That might have been as much a reason as anything.”

“The man came over with nothing and succeeded and he shared his success with his brothers, his cousins, his neighbors, his friends,” said Erwin Levy, of Palm Desert, Cal., who along with his brother Ernie survived the death camps before coming to America under the auspices of the Jewish aid agency Hais. The brothers were offered help by Kaufmann, though distantly related to him by marriage.

Survivors fully recognize what Kaufmann did was extraordinary.

“Mr. Kaufmann had the money…was in the United States…had the possibilities. Mr. Kaufmann used those possibilities and didn’t hold back at all. For this, he must be given credit. A rare person. An uncommon man. In the early 1930s he saw what was happening” in Germany and “he got us over. He really saved these families, including mine, and there’s no way we can express that thanks,” said Guinter Kahn.

No one asked Uncle David why he did it. For a man of such “humility,” it seemed an imposition. Ilse and Marcel Kahn have many questions today. She asks, “What did he know about the world war and Hitler? What thoughts did he have on the situation in Europe?” Marcel wonders, “Do you suppose he knew more than us?” He also wonders, “What made him do it, realizing there would be a lot of dollars involved if we were to default? And what did we display to make him confident to do such a thing?” He suspects Uncle David knew the family’s attitude of — “Just give us the opportunity” — mirrored his own enterprising spirit. They only needed a chance like the one S.N. gave him. “That’s all we were asking at the time,” he said.

As “he never talked about it,” Dorothy Kahn Resnick said, we’re left to guess. A great-nephew, Mayo Clinic researcher Scott Kaufmann, speculates Uncle David’s actions may have had something to do with “the upbringing” his great-uncle had in Germany. “His parents may have raised him with the idea that this is what you do for family.” He said the patriarchal role Uncle David filled was ironic given he had no children of his own, but the nephew recalls him as “always gracious and happy to see family members,” especially children.

Remarks from an acceptance speech Uncle David made may reveal a clue into what made him reach out to others. “Most of us have more good thoughts than we have bad ones,” he said, “and all we have to do is follow the good thoughts. The handicap is, the good thoughts are often not followed by required action.”

What makes his actions historic is that they may constitute the largest Holocaust rescue operation staged by a lone American. Omahan Ben Nachman has researched the Holocaust for decades and he’s sure what Kaufmann did is unique. He learned of Kaufmann’s deeds as an interviewer for the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Project filmmaker Steven Spielberg launched after Schindler’s List.

“After having learned of the rescue of a family by David Kaufmann I began a search in an attempt to learn if any other American had done anything near what Kaufmann had done,” Nachman said. “In this search I was unable to find anyone who had” brought “as many families out of Germany, to this country…Additionally, I could not find anyone who had brought this many people out and assumed total responsibility for them. All of this done quietly with no publicity for his actions. If only there had been more David Kaufmanns.”

“The story is important, for Kaufmann was one of the ‘silent heroes’ who made it possible for over 100,000 Jews to be saved immediately before and after the Shoah,” said Jonathan Sarna, the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braum professor of American history at Brandeis University. “These heroes provided guarantees, jobs and funds — often for people they had never met, and usually with no thought that they would be reimbursed. We know all too little about these people. Most of the literature concerning America and the Holocaust describes what was not done. Happily, the Kaufmann story reminds us of what was done.”

Survivors were motivated to do well as repayment of the debt owed Uncle David. There’s no doubt of “the gratitude” survivors like Marcel Kahn say they feel for being what his wife Ilse calls “the recipients of his goodness.”

Marcel’s brother, Guinter Kahn, a Florida physician and the inventor of Rogaine, said, “Had he not done what he did, we probably all would have been gassed. It’s incredible. What luck. Talk about hanging from fine threads…Everybody has their saints, and he’s ours.” Guinter said there’s no way to repay such a gift but to make good on it. “I’ve always thought, I’ll do as well as I can, because I’ve been given a chance.” “No one went on the public dole. He never had to support any of the people he sponsored,” said Joseph Kahn of Pennsylvania. Joseph was 8 when he came with his twin brother Hugo, sister Therese, parents and grandfather. The Khans settled in Omaha, where Joseph and Hugo attended school.

“I realize he signed an affidavit of support for me and was responsible for me. But in no way did I want him to be that,” said Fred Levy, who immigrated from Israel, where he and his family fled before the worst of the Holocaust. “I felt an obligation when I came to this country to meet him and thank him in person.” It was Levy’s way of telling him he would carry his own weight.

Ilse Kahn said the family “was too proud” to ever ask for “charity.” This, despite “the tough time” they faced getting along, Marcel Kahn said. “Most of us, fortunately, became successes. Certainly, the second generation really did well in terms of financial success. But without that opportunity, my goodness, we’d be nothing more than a pile of bones or ashes,” he said. “One would assume our successes made him that much happier.”

Success was indeed enough, said Ilse Levy Weiner, an Illinois resident who came with her folks on the S.S. Washington courtesy of Uncle David. “He told my father once that as many as he brought to the United States nobody ever bothered him for one nickel,” she said. “I never forgot that. He was so proud of everybody he brought to this country because they all worked really hard and nobody ever asked him for anything.” “He just wanted them to find their way, get settled and become good citizens,” said Kansas City resident Joe Levy, who was a boy when he, his brother and their parents arrived here. The Levys lived in Omaha for a time.

The kindness Uncle David showed his family was consistent with his giving nature.

“At the center of the book is the generosity and the goodness of this man,” said author Bill Ramsey. Uncle David’s good will extended to caring for a sister struck down by polio, arranging for Grand Island restaurants to feed the homeless on holidays and setting up a Self-Help-Society that supplied hard-on-their-luck folks food and clothing in exchange for work. Long before it was common, he paid sales staff commissions and offered employee sick benefits.

He led drives and made donations to build and improve the community. “He was involved with the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, St. Francis Hospital…and every board he served on he rose to be the chairman,” Ramsey said. Even in death he keeps giving via the Kaufmann-Cummings Foundation begun by his second wife, Madeline. It awards scholarships to Grand Island area students and recently made a donation to help with the restoration of the Grand Theatre the couple owned.

He led drives and made donations to build and improve the community. “He was involved with the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, St. Francis Hospital…and every board he served on he rose to be the chairman,” Ramsey said. Even in death he keeps giving via the Kaufmann-Cummings Foundation begun by his second wife, Madeline. It awards scholarships to Grand Island area students and recently made a donation to help with the restoration of the Grand Theatre the couple owned.

For Ramsey, the book project is “a labor of love.” The manuscript has made the rounds with editors and publishers, attracting much interest, but so far no deal has been struck. Ramsey and co-author Betty Shrier are in search of funds to underwrite the cost of printing enough books to provide one in every school and library in Nebraska. Nebraska Educational Television is weighing a possible documentary based on the book.

Family members who owe their lives to Kaufmann appreciate the fact this chapter in history will be preserved. “Because of this book I’ve learned a lot more details about Uncle David and his involvement in the community, civic responsibilities, duties, charitable causes and so on,” Marcel Kahn said, “and just how great of an individual he really was. It’s probably a story that should be told for generations.”

A Man Apart: David Kaufmann’s Little Known Rescue of Hundreds of Jews

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

As the shadow of the coming Holocaust darkened Europe, those sensing the dangers ahead looked for any means of escape. But getting away meant somehow securing the proper paperwork, making the right connections and scraping together enough money. No easy task. Even family living abroad was no assurance of a way out. It was the rare family that had someone who could take on the legal-financial burden of sponsorship. Then there were the shameful restraints imposed by governments, including the U.S., that made obtaining visas and entering another country difficult. Nationalism, isolationism and anti-Semitism ruled the day. Apathy, timidity, fear and appeasement closed borders, sealing the fate of millions.

Few stepped forward to offer safe harbor in the looming humanitarian crisis. One who dared was the late Jewish-German emigre David Kaufmann, a prominent business-civic leader in Grand Island, Neb. When others looked on or averted their eyes, he reached out and offered a lifeline to those facing persecution and peril. Recalled fondly as a philanthropist, he used the wealth and position acquired from his variety stores to spearhead community betterment projects. But he was far more than a good citizen. He was a hero unafraid to act upon his convictions.

David Kaufmann is pictured behind the lunch counter of Kaufmann’s Variety Store in Grand Island with one of his employees and a customer reading the menu. For more information on this photograph or other Hall County history, contact the Curatorial Department of Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer, 3133 W. Highway 34, Grand Island, NE 68801; 385-5316; research@stuhrmuseum.org; orwww.stuhrmuseum.org.

Courtesy photo

From 1936 until America’s engagement in World War II, Kaufmann responded to the growing threat overseas by endorsing affidavits of support for perhaps 250 or more people. The documents provided safe passage here under his patronage and his guarantee the refugees were sound risks. Affidavits were issued individuals, couples, siblings and entire families. His help extended to the post-war years as well, when he sponsored war victims displaced by the hostilities.

Kaufmann’s rescue of oppressed people from near certain imprisonment and probable death went untold outside his own family until last year. He rarely, if ever, publicly spoke of it. There were no press accounts. No mention in books. No radio-television interviews to shed light on it. Other than a letter he wrote a family he helped flee Germany, scant documentation exists, except for the few surviving affidavits of support he signed. More powerfully, there is the testimony of the men and women, now in their 70s, 80s and 90s, who found sanctuary here thanks to Kaufmann’s efforts to remove them from harm’s way.

These survivors came as children or young adults. Those that came during the Nazi reign of terror were fully aware of the terrible fate they avoided through his good graces. Some didn’t make it to the U.S. during the war. They escaped on their own or with the aid of family to havens like Palestine, where Kaufmann sent for them. Those that didn’t get out endured years of physical and emotional torture as prisoners, then more privation in refugee camps, before Kaufmann’s helping hands caught up with them and secured their travel to America.

Once here, the refugees received money and counsel from Kaufmann.

Some ended up in Grand Island and worked at his store. Others settled in Omaha. Most opted for big cities — New York, New Orleans, Chicago, et cetera. Wherever they went, Kaufmann kept tabs on how them. Over time, the family tree grew. Their American ranks must now number in the high hundreds. They own a rich legacy in America, too, where many members have distinguished themselves.

David Kaufmann’s gift of life only grows larger with each new birth and each new generation. Yet his name and good works remain obscure outside the clan and his adopted home. That’s about to change, however. The righteous actions of Kaufmann are the subject of a book-in-progress by Omaha authors William Ramsey and Betty Dineen Shrier that details all he did to ensure his family’s survival in the Shoah. Nebraska Educational Television producers are considering a documentary film on the subject. There is urgency in having the story recorded soon, as with each passing year fewer and fewer of the original Kaufmann wards survive.

Collaborators on two previous books, Ramsey and Shrier were approached with the idea for the Kaufmann book by Ben Nachman, a retired Omaha dentist who’s devoted the past 30 years to Holocaust research. In the course of Nachman serving as an interviewer for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Visual History Project in the early 1990s, he came upon survivors aided by Kaufmann. He knew it was a story that must be shared. Ramsey and Shrier agreed, accepting the assignment. They began work on it last year and have since interviewed dozens of figures touched by Kaufmann.

Collaborators on two previous books, Ramsey and Shrier were approached with the idea for the Kaufmann book by Ben Nachman, a retired Omaha dentist who’s devoted the past 30 years to Holocaust research. In the course of Nachman serving as an interviewer for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Visual History Project in the early 1990s, he came upon survivors aided by Kaufmann. He knew it was a story that must be shared. Ramsey and Shrier agreed, accepting the assignment. They began work on it last year and have since interviewed dozens of figures touched by Kaufmann.

“This sounded like a big story. A national or international story. And I thought it was a story that had gone untold too long. That’s what really drove me,” said Ramsey, a well-known public relations man. “People of all backgrounds are moved by what happened in the Holocaust. And with it being the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II and the liberation of the death camps, the timing was perfect.”

For co-author Shrier, the sheer humanity of it all hooked her. “I think that I have never come across anyone who was so generous across the board to so many different people as David Kaufmann was,” she said. “And he didn’t discriminate with race or creed or philosophy. It made no difference to him. He was good to everybody. And I’ve never met anybody or heard of anybody with that kind of openness. The thing about it is, he was a great businessman. He was stern when it came to business principles, but he still knew how to give.”

Good works defined Kaufmann’s life. The entrepreneur was among a handful of Jewish residents in the south central Nebraska town, yet he assisted all kinds of people in need. His largess extended to everyone from relatives and friends to complete strangers. His contributions to various building committees helped transform Grand Island into a modern city.

Kaufmann kept his most personal good works quiet. Until the Grand Island Independent began reporting last winter on the book project, which has led the authors on repeated research trips there, few residents knew Kaufmann’s name and fewer still his legacy as a Holocaust rescuer. Before he became a hero, he was a man on a mission — hell-bent on improving himself and the lot of his family.

Uncle David, as he’s called in family circles, epitomized the great American success story. He came to this country in 1903 not knowing the language, but through his industriousness he mastered English, he worked his way up the retail trade, first in New York and then in Grand Island, and he soon went into business for himself. Only a few years after arriving here, he’d built a thriving chain of five-and-dimes and put his imprint on all aspects of community life. As Grand Island’s leading citizen, he didn’t need the hassle of vouching and assuming responsibility for the welfare of a sizable number of distant relations. He especially didn’t need the risk to his riches and reputation in the Great Depression, when fortunes and good names were easily lost. Not wanting publicity for his actions, which went against the tide of official and popular sentiment to keep “foreigners” outside the nation’s borders, he carried on his rescue campaign in near secrecy. Despite all the reasons not to get involved, he did. This unflinching sense of duty makes Kaufmann a compelling and laudable figure and is the focus of Ramsey and Shrier’s book.

“At the center of the book is the generosity and the goodness of this man,” said Ramsey. Kaufmann’s good will towards his family, including caring for a sister struck down by polio, was part of a pattern of kindnesses he exhibited in his lifetime. For example, he arranged for Grand Island restaurants to feed the homeless on holidays, reimbursing the eateries himself. He set up a Self-Help-Society that supplied hard-on-their-luck folks food and clothing in exchange for work. He sprung for free sundaes — preparing them himself — when employees did inventory on weekends. Long before it was common, he paid sales staff commissions and offered employee sick benefits. He hosted backyard picnics that fed small armies of friends, neighbors and workers. He led drives and made donations to build and improve the communities he lived in and did business in. “He was called Mr. Grand Island by many. He was involved with the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, St. Francis Hospital…and every board he served on he rose to be the chairman,” Ramsey said.

Kaufmann died in 1969, but even in death he keeps on giving via the Kaufmann-Cummings Foundation started by his second wife, Madeline.

Then there’s the ripple effect his good works have had. Ramsey, Shrier and Nachman say that almost without exception the people he sponsored, as well as their descendants, have been high achievers, motivated to do well as repayment of the debt owed Uncle David for affording them America’s opportunities.

“We’ve not met or talked to anyone yet that wasn’t very successful. There’s doctors, lawyers, researchers. I mean, they were driven by this legacy. I think they felt their lives were saved, and they probably were. He gave them a chance to do something with their dreams and they made the most of it,” Ramsey said. “I think they were trying hard to please him because he sponsored them and they didn’t want to be a burden on him or on the United States. That was part of each affidavit he signed. It said he was responsible for these people if they don’t make it here. He was putting his name and fortune and everything else on the line.”

The only recompense Kaufmann wanted for his assistance was the assurance his wards were not a drag on society. That alone was reward enough for him said Bourbonnais, Ill. resident Ilse Weiner, who was 17 when she and her parents, Ludwig and Frieda Levy, came on the S.S. Washington courtesy their affidavit of support from Kaufmann. “He told my father once that as many as he brought to the United States nobody ever bothered him for one nickel,” she said. “I never forgot that. He was so proud of everybody he brought to this country because they all worked really hard and nobody ever asked him for anything.”

The gratitude felt by Kaufmann’s charges made them strive to please him. “I realize he signed an affidavit of support for me and was responsible for me. But in no way did I want him to be that,” said Fred Levy, whose affidavit from Kaufmann enabled him to immigrate from Israel, where he and his family fled before the Final Solution.

“I felt an obligation when I came to this country to meet him and thank him in person.” It was Levy’s way of telling him he would carry his own weight.

Even after her family established themselves here, Weiner said, he would visit them on buying trips to Chicago, always bearing gifts and making sure they were getting on OK, offering help with anything they needed. She said once when her father had trouble finding work, Kaufmann put in a good word for him. She said Kaufmann even aided a friend of the family, no blood relation at all, in relocating to America.

Survivors hold Kaufmann in the highest esteem. “They love this man. It just comes through,” Ramsey said. Weiner said, “He was a warm man. Thoughtful. He gave good advice. When we arrived in The States, he sent gifts and a check for $50. He was very generous. He was fantastic to us. He was such a good person. How should I say? We looked up to him like if he was God, because he saved our lives. What more can I say? He saved our lives.” The most famous family survivor, Rogaine inventor and medical doctor Guinter Kahn, has said, “Everybody has their saints, and he’s ours.”

Example of an Affidavit of Support

On his 80th birthday, Kaufmann was presented “a family tree” that relatives commissioned an artist to paint. It includes the names of those he rescued and refers to trees planted in Israel to commemorate his life saving legacy.

If Kaufmann was inspired in his good deeds by anyone, it may have been S.N. Wolbach, the figure responsible for bringing him to Grand Island. A native New Yorker, Wolbach went west himself as a young man and found his pot of gold on the prairie, where he opened a department store and held banking interests. On a 1904 buying trip back east he visited the Abrams and Strauss store in Brooklyn, where he was impressed by the salesmanship and work ethic of a young clerk named David Kaufmann. Wolbach convinced Kaufmann his fortune lay 1,500 miles away working for him at Wolbach and Sons. Flattered, Kaufmann accepted an offer as floorwalker and window trimmer. Only nine months after his arrival in America, the enterprising emigre headed west to meet his destiny.

No sooner did he get there, than he wanted out. Authors Ramsey and Shrier have come upon letters Kaufmann exchanged with his brother in Germany in which David bemoans “the lack of pavement, the all-too frequent dust storms and the unimposing buildings.” Shrier said Kaufmann even asked his brother to find him a retail opening back in their homeland. By the time his brother wrote back saying he’d found a position for David, things had changed. “There was something about the old town that made me like it,” Kaufmann reflected years later in print. “There were no big buildings, but that doesn’t make a town. It’s the people who live in a place that make you love it. There was something about those old-timers and the ones who came after me that made me like Grand Island. There was something about the businessmen and the people…their willingness to cooperate in all worthwhile undertakings, that makes it a pleasure to work with them.”

Ramsey speculates Kaufmann’s mentor, Wolbach, “was The Great Man model” he aspired to. “Wolbach was a doer as well. He did a lot of charitable work. He was a well-to-do, respected person. And you get the feeling Kaufmann looked up to this man and figured maybe this is how you become a success,” Ramsey said.

As the Nazis came to power in Germany, Kaufmann was already a self-made man. In his occasional visits and regular correspondence home he kept abreast of the worsening conditions for Jews there and made a standing offer to help family leave. His first affidavit got Isi and Feo Kahn out in 1936. The young couple moved to Grand Island, where their daughter Dorothy Kahn Resnick was born and raised.

Dorothy said her mother was a “key” conduit and emissary in the conspiracy of hearts that evolved, staying in touch with family abroad and feeding Kaufmann new names needing affidavits of support. She even brought him the forms to sign.

As the Nazis clamped down ever more, “people were desperate,” Ramsey said. “They could see what was happening.” Official, legal channels for visas dwindled. Affidavits of support, forged documents or bribes were the only routes out. Dorothy said her mother went back repeatedly to Uncle David with new names, saying, “‘Here’s someone else.’ Some were very distant relations. But she told me he never questioned her. He never wanted to know who they were and how they were related. He relied on her. He trusted her. He put his faith in her that if she said it was OK, he signed it. Uncle David and my mom just did the right thing. They just did it. Maybe the simplicity of it is what’s so beautiful.”

As “he never talked about it,” Dorothy said, we’re left guessing why he acted. Remarks from an acceptance speech he gave may be as close as we’ll ever get to knowing what made him do it. “Most of us have more good thoughts than we have bad ones,” he said, “and all we have to do is follow the good thoughts. The handicap is, the good thoughts are often not followed by required action.” Hundreds lived because Kaufmann heeded his better self to take action.

Share this: Leo Adam Biga's Blog

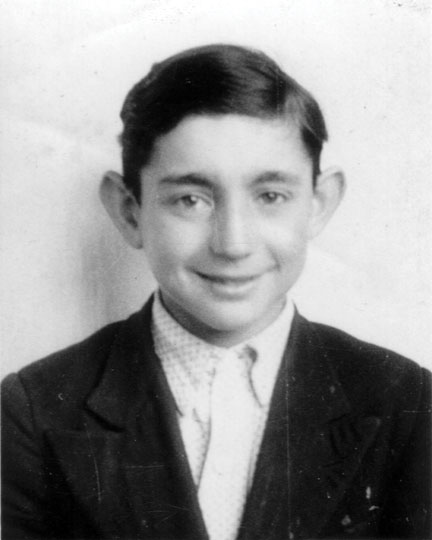

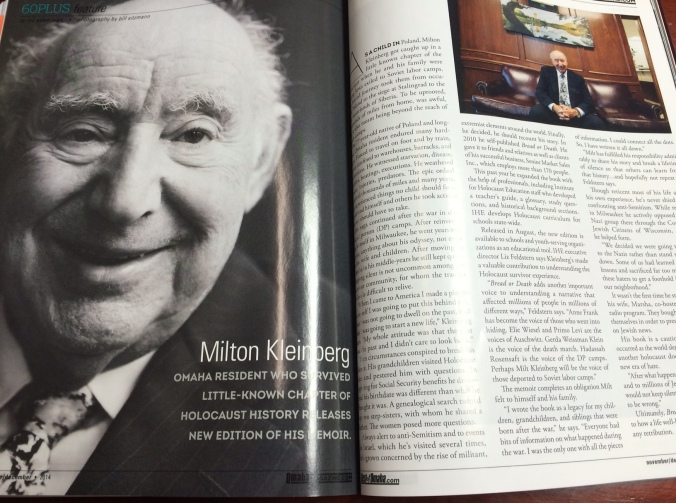

Milton Kleinberg

Milton Kleinberg

He led drives and made donations to build and improve the community. “He was involved with the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, St. Francis Hospital…and every board he served on he rose to be the chairman,” Ramsey said. Even in death he keeps giving via the Kaufmann-Cummings Foundation begun by his second wife, Madeline. It awards scholarships to Grand Island area students and recently made a donation to help with the restoration of the Grand Theatre the couple owned.

He led drives and made donations to build and improve the community. “He was involved with the Salvation Army, the American Red Cross, St. Francis Hospital…and every board he served on he rose to be the chairman,” Ramsey said. Even in death he keeps giving via the Kaufmann-Cummings Foundation begun by his second wife, Madeline. It awards scholarships to Grand Island area students and recently made a donation to help with the restoration of the Grand Theatre the couple owned.

Collaborators on two previous books, Ramsey and Shrier were approached with the idea for the Kaufmann book by Ben Nachman, a retired Omaha dentist who’s devoted the past 30 years to Holocaust research. In the course of Nachman serving as an interviewer for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Visual History Project in the early 1990s, he came upon survivors aided by Kaufmann. He knew it was a story that must be shared. Ramsey and Shrier agreed, accepting the assignment. They began work on it last year and have since interviewed dozens of figures touched by Kaufmann.

Collaborators on two previous books, Ramsey and Shrier were approached with the idea for the Kaufmann book by Ben Nachman, a retired Omaha dentist who’s devoted the past 30 years to Holocaust research. In the course of Nachman serving as an interviewer for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Visual History Project in the early 1990s, he came upon survivors aided by Kaufmann. He knew it was a story that must be shared. Ramsey and Shrier agreed, accepting the assignment. They began work on it last year and have since interviewed dozens of figures touched by Kaufmann.