Archive

SkyVu Entertainment pushes “Battle Bears” brand to sky’s-the-limit vision of mobile games, TV, film, toys …

Omaha’s young creatives community is the subject of much press and buzz, as this blog is in part a testament to, and SkyVu Entertainment is one of the more interesting stories on this burgeoning scene. The self-desccribed transmedia company that does animation and designs mobile games is led by a visionary named Ben Vu who is completely serious when he says he views SkyVu as the Pixar of mobile games and as a mini-Disney. The following profile of Ben and his company will be appearing in an upcoming issue of B2B Magazine. I am sure to be revisiting his story and his company’s story again in the near future.

SkyVu Entertainment pushes “Battle Bears” brand to sky’s-the-limit sision of mobile games, TV, film, toys …

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in B2B Magazine

With Battle Bears reaching 14 million downloads and counting, maker SkyVu Entertainment is a Player in the mobile games world.

“We created an entertainment distribution platform through not something like Facebook or Twitter but something like a brand. We like to see ourselves as the Pixar of mobile games. A mini-Disney,” says Ben Vu, co-founder of SkyVu with his brother Hoa.

The transmedia company, which launched here rather than Asia thanks to Nebraska Angels support, has designs on making a feature-length Battle Bears film and is negotiating a television series and toy line. SkyVu began as an animation shop before entering the games field.

A graduate of Disney-founded Cal Arts, Ben worked on the stop-motion feature Coraline and has made a study of the Walt Disney Company. He notes parallels between the Brothers Vu and Midwesterners Walt and Roy Disney.

“I see a lot of how myself and my brother are in how Walt and Roy Disney played off of each other,” says Ben. “Roy was the money guy and Walt more the creative visionary, and a lot of times the creative visionary wanted all the resources he needed to fulfill that vision while the other one watched out for the road ahead.”

Ben’s the creative mastermind. Hoa, who heads up the Singapore office, is the tight-fisted numbers wonk. This yin-yang finds them often butting heads. Their conflicting personalities are the models for two Bears characters, Oliver (Ben) and Riggs (Hoa). “They’re always at odds but somehow every episode of every game they find a way to work together to accomplish the mission,” says Vu. “This is how Ben and Hoa work.”

The only children of Vietmanese refugee parents, the Vus grew up in Norfolk, Neb. and graduated from Omaha Creighton Prep. Both were fascinated with movies, games and drawing. Their skill sets meshed with the new digital age.

“We’re an entertainment company and we use technology to entertain, but boy do we love technology,” says Ben, “because it allows us to compete at a high level, reaching millions of people within a short amount of time at a fraction of what it used to cost. With the advent of the iPhone followed by the iPad and the growth of Android we could not be in a better place right now.”

He says their signature game “combines cute with a bit of violence in a compelling story about a family of robotic bears trying to save the world but learning from each other in the process.” Its put SkyVu in elite company with EA, THQ, Sony, Nintendo, even Microsoft. “They all want a piece of the mobile pie.”

He says big companies have more resources but SkyVu has its own advantages.

“Because of our careful attention to character and story, first and foremost, we build engaging games. Something we’ve learned in a short amount of time and that we’re good at is providing a snack bite size quality experience coupled with a very appealing character and story. The magic is those two things coming together.

“We’re one of the unique studios in the world that has an animation and a games studio all under the same roof driven by the same creative force.”

Fans keep coming back for more at the App Store.

“We don’t talk about users or players, we deal in building loyal fans and taking care of them.”

Bigger audiences await.

“The (film) studios and networks are now looking at mobile games as a rich source of content,” says Vu, who feels SkyVuis well-poised to seize the day. “As the mobile game experience becomes more rich, as these phones get faster, as tablets start to invade the living room more, the production quality rises and SkyVu needs to scale itself up appropriately to be ahead of the curve.”

Getting there requires more capital, perhaps a partner, and he says SkyVu is attracting serious offers. The team’s multi-skilled animators and coders allow flexibility.

“We’re in mobile right now but there’s no doubt in my mind you’ll be experiencing our brands in the living room, possibly in the airplane and the car, certainly in theaters.”

He keeps a shoebox full of story-character concepts in his office, which doubles as the war room. White boards display a calligraphy of brainstorms. “There’s no shortage of ideas.”

SkyVu’s 14-person team is all local and Vu’s confident Nebraska will continue filling its needs. In January he strategically relocated SkyVu to Ak-Sar-Ben Village to be near the Scott Technology Center, Peter Kiewit Institute and UNO College of Business.

He says SkyVu offers a rare Midwest opportunity for “talented young people to create stuff seen and experienced by millions of people.” He’s committed to staying put. “The team we built here got us to where we are, so why would we abandon that? We can be competitive with any region in the country, with any country, as long as we maintain our innovation and creation.”

“It’s really daring what we’re trying to do here, but we’re actually doing good, we’re making traction. If the TV series becomes a reality things are going to go crazy. We’re just breaking even now and profitability is our number one priority because we have to grow.” ”

He anticipates adding 60-plus employees in two years to accommodate new ventures.

The next big thing may only be a shoebox away.

Related articles

- Battle Bears Royale – SkyVu Pictures (itunes.apple.com)

- Tapjoy has 25m monthly active users (mobile-ent.biz)

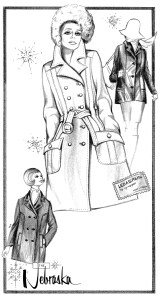

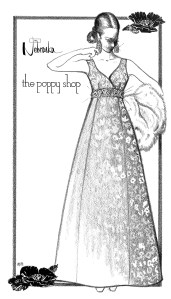

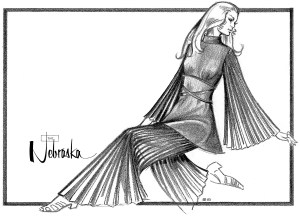

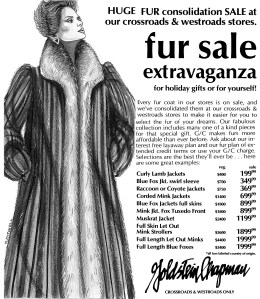

Timeless Fashion Illustrator Mary Mitchell: Her Work Illustrating Three Decades of Style Now Subject of New Book and Exhibition

Fashion illustrator Mary Mitchell of Omaha is about to enjoy the kind of rediscovery few artists rarely experience in their own lifetime. Selections from Mitchell’s 1,000-plus fashion illustrations, an archive that sublimely represents decades of style, are the subject of a forthcoming book and exhibition that will expose her work to a vast new audience. No less a fashion icon than famed designer Oscar de la Renta has high praise for her work in the foreword to the book, Drawn to Fashion: Illustrating Three Decades of Style by Mary Mitchell. The soon to be published book explores her work in words and images and is a complement to the same titled exhibition opening the end of January and continuing through the spring at the Durham Museum in Omaha. My story below, which will appear in the February edition of the New Horizons newspaper, charts her rich life and career. The story also reveals how her illustrations may have never been rediscovered if not for the discerning eye and persistent follow through of her friends Anne Marie Kenny and Mary Joichm. You can see more of Mitchell’s work and order the book at http://www.drawntofashion.com. A short video about Mitchell on the Drawn to Fashion website is narrated by Oscar-winner Alexander Payne, a family friend from the Greek-American community they share in common in Omaha. Clearly, Mary and her husband John Mitchell have made many good friends and it’s only fitting that her work of a lifetime is finally getting its just due on a stage large enough to encompass her immense talent.

NOTE: My profile of the aforementioned Anne Marie Kenny, a cabaret singer and entrepreneur, can be found on this blog, where you can also find my extensive work covering Alexander Payne. Mary Mitchell’s reemergence as a fashion illustrator comes as the Omaha fashion scene is enjoying its own renaissance, and my stories about that burgeoning scene and its all-the-rage Omaha Fashion Week can also be found here.

Mary Mitchell in her studio, @photo Jim Scholz

Timeless Fashion Illustrator Mary Mitchell: Her Work Illustrating Three Decades of Style Now Subject of New Book and Exhibition

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to be published in the New Horizons

Fashion illustration revived

Just as good art is timeless, so are the artists who make it.

Born in Buffalo, New York, fashion illustrator Mary Mitchell has seen art movements come and go through the years, but quality work, no matter what it is called or when it is en vogue, endures.

Much to her surprise, finely articulated fashion illustrations she made in the late 1960s, 1970s and 1980s are finding new admirers inside and outside the world of design. Friends and experts alike appreciate how Mitchell’s work stands the test of time while offering revealing glimpses into the lost art of fashion illustration she practiced.

She worked as an in-house illustrator for an elite Omaha clothing store, “The Nebraska,” for four years. She then decided to become a freelance illustrator, which found her illustrating men’s, women’s, and children’s fashions for several leading Omaha stores. Her illustrations appeared in the Omaha World-Herald, the Sun Newspapers, the Lincoln Journal-Star and various suburban papers and local magazines.

When there was no longer a demand for fashion illustration, she moved onto other things. Her originals – meticulously rendered, carefully preserved black and white fashion illustrations – no longer had a use and so she put them away in her studio at home. Untouched. Unseen. Forgotten.

That all changed in 2010 when, suddenly, Mary found her work from that period the subject of renewed interest. It happened this way:

Two good friends visited Mary and her husband, John Mitchell, in Longboat Key, Florida, where the couple reside half the year. When guests Anne Marie Kenny and Mary Jochim asked Mary what she used to do for a living the artist showed a portfolio of her work. Kenny and Jochim were instantly captivated by Mitchell’s handiwork. The guests were so impressed that en route home they conceived the idea for an exhibition. The women formed an organizing committee and after many meetings and much planning, the right venue for the exhibition was found at the Durham Museum.

The resulting exhibition and book, Drawn to Fashion: Illustrating Three Decades of Style by Mary Mitchell, marks the first time and most certainly not the last that the artist’s work will be exhibited. The show opens January 28 and runs through May 27. Omaha-based Standard Printing Company designed and printed the book. The University of Nebraska Press is distributing it.

What so captured her friends’ fancy?

For starters, Kenny appreciates “the intricate detail and attitude, crafted in a superb drawing technique,” “the graceful lines” and “the exquisite flair” that run through Mary’s work. She adds, “The exhibit and new book devoted exclusively to her fashion illustration demonstrate her unique expression of a genre that is awesome to behold, highly collectable, and more relevant today than ever.”

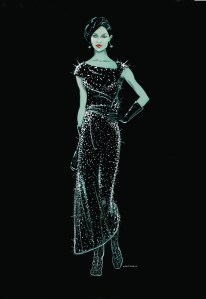

Jochim, too, is struck by “the intricate strokes, down to the individual hairs in a fur coat, a herringbone weave, or the sparkle in a glittering evening jacket.” She said Mitchell “breathes life into the illustrations. The models in her drawings seem to all have a story to tell which makes you curious.”

Fashion designer icon Oscar de la Renta writes in his foreword to Drawn to Fashion: “Mary is a true artist, elegant and masterful. Her illustrations have enriched the experience of fashion in our time, and brought joy to the mind’s eye.”

Academics sing her praises as well.

Dr. Barbara Trout, a professorat the University of Nebraska Lincoln’s Department of Textiles, Clothing and Design, which is contributing original garments for the exhibition, said Mitchell’s work “marked technical excellence through the fine articulation of garment details. Her ability to mimic the hand of the fabric, its distinct structure, and the projected movement allowed the consumer to envision themselves in those garments…Mary’s fine examples of illustration are truly a benchmark of their time.”

“Mary Mitchell’s fashion drawings reveal the confident hand of the experienced illustrator, one who brings to her work an editor’s ability to subtract and to refine, and an artist’s to enhance and to glamorize,” said Michael James, chair and Ardis James professor in the UNL Department of Textiles, Clothing and Design.

©Mary Mitchell

The rediscovery of Mitchell’s stunning cache of some 1,000 illustrations not only prompted the book and accompanying exhibition, it inspired the artist herself to create new fashion illustrations for the first time in years.

“I thought I probably would never have done any more fashion illustrations if it were not for Anne Marie Kenny and Mary Jochim. They showed so much interest in my work, it inspired me to start drawing in color, since all my work previously was in black and white to be printed in local papers,” said Mitchell.

Her new work now graces the book and the exhibit displays alongside her older work. She makes the new illustrations not for any client or acclaim, but purely for her own enjoyment and pleasure.

She throws herself into the work, creating without the burden of client restrictions or project deadlines.

“I get so excited about this that now I go down to my studio and work for hours to create another piece of art.”

She’s experimenting with other mediums, such as acrylic paints and watercolors, to draw fashions. Perhaps most pleasing of all, she feels she hasn’t lost her artistic touch. Her eye for detail, sharp as ever.

One should not assume Mitchell halted her creative life after the fashion illustration market dried up in the 1980s when clients and publishers abandoned hand-drawn illustrations for photographs.

No, her artistic sensibility and creativity infuse everything she does. It always has. It is revealed in the tasteful way she decorates her contemporary home, in how her hair is styled just so, in the stylish clothes she wears.

She is, as Jochim puts it, “a natural beauty” whose “graciousness and glamour” seem effortless.

Kenny said, “Mary lives and breathes art in every aspect of her life – her beautiful home, her elegant manner, her exquisite fashion illustrations, her glamorous style. Mary brings beauty to all that she touches.”

When fashion illustration was no longer a career option, Mitchell found other avenues of expression to feed her creativity, She became vice president of an advertising agency called Young & Mitchell, where she continued her graphic art. During this time she designed billboards, posters, and stationery logos, she called on clients, she made presentations, created television story boards and camera cards, wrote copy, and created advertising campaigns.

Her husband had bought several radio stations in Omaha and throughout Nebraska. The station general managers began asking Mary to create logos and to handle advertising for them. She then became a hands-on vice president with Mitchell Broadcasting Company. She created logos, designed all magazine and newspaper layouts, and bus signs for the stations, and handled creative projects for station promotions and concerts.

She seamlessly went from the intimacy of fashion illustration to the, by comparison, epic scale of signs and billboards.

“It was a different style of art needed for commercial advertising. I used to draw intricate, delicate drawings and now I was doing big, bold designs. Of course, that’s not fashion, it’s advertising, but it’s all a matter of design.

“It was a lot of fun. The people that worked in that environment each had their own personality – the DJs, the sales people, the managers.”

The passion of this accomplished woman would not be denied , certainly not suppressed. It is a trait she displayed early on growing up in Buffalo, New York as the only child of Greek immigrant parents, John and Irene Kafasis.

©Mary Mitchell

Where it all began

Born Mary Kafasis, she inherited determination from her folks, who ventured to America from Siatista in northern Greece. Her father arrived in the States at age 16 with $11 in his pocket. After a succession of menial jobs he worked on the railroad as part of a track maintenance crew. The work paid well enough but was miserable, backbreaking labor.

Her father and a buddy of his saved up enough to buy a candy shop. Greek-Americans up and down the East Coast and all around the U.S. used confectionaries and restaurants as their entree to the American Dream. She said her father was pushing 30 and still single when he wrote his parents asking that they find a suitable bride for him in the Old Country.

“My mom was from the same village in Greece as my dad. They married and he brought her back to the States, and she worked very hard with him in their candy store,” said Mary.

When Mary was about age 8 she spent an idyllic three months in Greece with her mother, visiting the village in which her mother was born and raised.

“It’s a beautiful little village surrounded by mountains. We stayed with my grandmother and I met all my aunts and uncles and I had fun playing with all my cousins. It was a lovely time.”

The small family carved out a nice middle class life for themselves. “My parents did well, but they worked long hours and very hard.”

Everything revolved around the family business located in South Buffalo. The family lived upstairs of the shop.

“My mom would hand dip chocolate candies, such as nut and fruit clusters. Dad would make homemade ice cream and sponge taffy. For Easter and Valentine’s Day they would make candy bunnies, baskets, and hearts and fill them with delicious chocolates and decorate them with colorful flowers and ribbons. My job was to fill the baskets and Valentine’s hearts with the chocolates.”

Summers and after school found her working in the shop. She began as a dishwasher before she was entrusted to wait on customers. Her penchant for drawing surfaced early on.

“I remember when I was little I would get a pad, colored pencils or crayons or paints and start drawing figures and designing dresses. That’s when I decided I wanted to be an artist. My mom was so encouraging. She also had me take piano and dancing lessons.”

Mary went to great lengths to pursue her art passion. “I was required to attend South Park High School. It didn’t have an art program, so after my freshman year I wanted to transfer to another school outside my district, clear on the other side of town – Bennett High School. It was renowned for its excellent art program. My girlfriend Shirley Fritz and I went to City Hall and obtained special permission to attend Bennett High. We really felt strong about it.”

Going to that far-off school meant waking up earlier and coming home much later. The extra time and effort were worth it, she said. “My art teacher at Bennett was phenomenal. She had a great gift of teaching and got me involved in several national contests. I won national awards in poster design and an award from Hallmark cards for my design of a greeting card. I also designed the covers of two school year books.”

Then tragedy struck. Just two months before Mary’s high school graduation her mother died. “She had been ill for a long time and in the hospital. She was only 39.” Losing her mother at 17 was a terrible blow for the only child.

“I was scheduled to go to Syracuse University, but my dad would not let me go. He insisted I go to secretarial school instead of art school. He said, ‘You’re a woman, you’re going to get married, what do you need to go to art school for?’ It was an (Old World) Greek mentality. I know if my mother were there, she would have insisted I go to college and art school.

“He also said he would not pay for my tuition to college or art school. Luckily, my mother left a savings account in my name, so I used that for my tuition, and of course lived at home with my dad.”

She decided to attend the University of Buffalo in conjunction with the Albright Art School and graduated as a fashion illustrator. Her original intent was to be a magazine illustrator, but she was advised against that male-dominated field and steered into fashion illustration.

©Mary Mitchell

“One of the courses I took was life drawing, which teaches you the structure of the body’s bones and muscles. It’s very important to have that if you’re going to do fashion figures, to get the proportions and movements right, and to know how clothing is draped on the body.”

She learned, too, how elements like light and shadow “make a big difference” when sketching different fabrics and textures.

“After graduating I took my portfolio to all the department stores in Buffalo, where I kept running into resistance: ‘Do you have experience?’ ‘No, I just graduated.’ ‘Well, call me when you get experience.’

“So after several months of job hunting I took a job as a sign painter for the display department at a Flint & Kent department store, knowing that the fashion illustrator was pregnant and would be leaving in a few months. Lo and behold, they called me when she left and I got my first job as a fashion illustrator. I was in Seventh Heaven.”

©Mary Mitchell

New directions

Then John came into her life. They met as delegates at a Cleveland, Ohio convention of the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association, a service organization closely allied with the Greek Orthodox Church. Like her parents, John’s mother and father were from Greece, only from Athens. His family’s name, Mitsopoulos, was Americanized by his dad to Mitchell. His folks settled first in Kansas City before moving to the south central Nebraska town of Kearney.

John was a recent Georgetown University law graduate with an eye on practicing law in Kearney and plans for pursuing a political career. He wooed Mary from afar, the two got engaged, and in 1951 they married in Buffalo before starting a new life together in Kearney. Leaving home was bittersweet for Mary.

“Kearney in those days was a town of only 13,000, with no opportunities for me to work as an artist. With no family or friends, it was very difficult. So I decided to go back to school (at then-Kearney State Teachers College). I took two years of French, English literature, and psychology and during that time I would venture into the art department and talk to the art teachers. They said they needed more teachers and asked if I would join the faculty. I finally said yes and started teaching Art 101 and Art Appreciation.

“I was asked to design brochures for the college and I was also commissioned to redesign the interior of the student union.”

More interior design jobs followed in later years. Finally getting to apply her craft made her feel “a little better” about the move West.

While in Kearney Mary gave birth to her and John’s only child, John Charles Mitchell II, who is now a gastrointestinal physician in Omaha and married to M. Kathleen Mitchell of Red Cloud, Neb. They have two grown children, John Bernard Mitchell and Emily Suzanne Mitchell.

Meanwhile, her husband’s law practice flourished and his political career took off. He became state Democratic party chairman in the 1960s. It was a heady time.

“We got involved in local, state, and national politics. We got to meet Lyndon Johnson and John F. Kennedy. When JFK came to Kearney for a political event we met him with our young son and he held Johnny. We met both Teddy and Bobby Kennedy. John was very close to Hubert Humphrey. It was a very busy and exciting time.”

©Mary Mitchell

©Mary Mitchell

©Mary Mitchell

Mary Mitchell’s halcyon fashion illustration days

Mary pined to work full-time and to have her own professional identity. John, by the way, “supported anything I wanted to do,” she said. The opportunity to fulfill her creative hunger finally came when the family moved to Omaha in 1968. Scouring the classifieds she saw an ad that read, “Fashion illustrator wanted, Nebraska Clothing.” A venerable clothing store then, “The Nebraska” was renowned for its quality brand name selections. She called, made an appointment to interview for the job, and got hired on the spot.

She enjoyed her four years with “The Nebraska” very much, but she reached a point where becoming a freelance artist made sense. She resigned from Nebraska Clothing in December 1971 and went into business for herself, calling her boutique design firm Mary Mitchell Studio. “Freelancing,” she said, “was the best career thing I did. It was a little scary at first, but people started calling me to design their ads and illustrate their garments. It was so wonderful to be independent and to work at my own pace. Each year kept getting better.”

Her client roster grew to include: TOPPs of Omaha; Goldstein Chapman; Herzbergs; Zoobs; Natelson’s; Parsow’s; Wolf Bros.; I. Eugene’s Shoes; Hitching Post; Crandell’s; The Wardrobe for Men, Backstage, Ltd.

“My general attitude is, whenever I sit down to create an ad or drawing I will try my best to achieve the attributes of the client’s business. I want it done as perfectly as possible.”

Creating a finished advertisement for a newspaper or magazine is a several step process. It begins with the client deciding the size of the ad, which determines its cost. Then the layout is made, the drawing of the garment is executed, and the ad copy written. Whether a suit, a dress, or a pair of shoes, there are usually instructions that go along with it. For instance, a client might want an 18 year-old look for one item and a 30 year-old look for another. A Girl-Next-Door vibe here, a sophisticated image there. A relaxed stance in one ad, a formal posture in another.

“The article was given to me to sketch and I created the look of the individual it would appeal to,” she said.

When doing fashion illustration ads, there is always a space limitation to work within, based on column inches. And, of course, there are always deadlines.

Once the parameters of the job were known, Mitchell arrayed the tools of her trade: pencils, pens, brushes, inks, paints, drawing paper. Her job then became animating the apparel and the figure wearing it to accentuate the fashion.

She started with a rough layout.

“There were two methods of drawing for reproduction at that time,” she said. “One used a fluorographic solution mixed with India ink to obtain various shades of gray and painting with a fine brush or drawing with a pen. The other used a No. 935 pencil to draw on textured paper to obtain various shades of gray to black. Different techniques produced different effects.

“If you have a dress with lace on it, you used a very fine quill pen, with a fine point. The way you handle the light and shade for materials and patterns depends on the amount of wash you use with your brush, dark to light.”

By mixing more water with a wash and by adjusting her brush stroke she approximated velvet, taffeta, fur or leather.

It’s all in the details, particularly in black and white. “The more you show the detail the better the garment looks. You try to approximate the article as close as possible.”

Depicting the essence of a garment requires great skill.

“The skilled fashion illustrator must be able to reduce the architecture of a garment to its essentials while amplifying its hedonic appeal. This is no small task when the means she has to do this are a few marks of pencil or pen or brush on paper. She must interpret the designer’s stylistic signature, but to be convincing she must render with her own authoritative style,” said UNL’s Michael James.

The dynamic sense of flow or movement in Mitchell’s work, then and now, is intentional. “I don’t want it just to be a static figure, I want it to be active.” Besides, to show off the clothes in their best light, she said, “you’re not going to draw the body straight forward, you’re going to give it movement.”

A file of fashion magazines offer her ideas to extrapolate from. Perhaps a certain facial type or expression that catches her attention. Or the way a model’s hair blows in the wind. Or the way a hand is gestured.

“Fashion illustration figures are always elongated,” she said. “We were taught that the human figure is eight heads high but illustrative figures should be nine heads high or tall because that gives a more dramatic and elegant look.”

When she did fashion illustration for her livelihood she made a habit of studying fashion ads. “I certainly admired the Sunday New York Times fashion ads and those in the Chicago and L.A. papers as well.” Staying abreast of the latest trends meant she frequented local fashion shows. “I modeled, too, for some of the stores that I did ads for when I was thinner and younger,” said the still petite Mitchell.

As a freelancer she not only completed the artwork but the entire layout and the copy as well. All of it a very tactile, labor, and time intensive process.

“I would do the layout, then draw the article, type the copy, give it to a typesetter, and order certain fonts, and when I got it back I would cut it out with an X-acto knife and paste it up with rubber cement. It was the only way it was done then – no computers.”

From there, it went to the printer, and the next time Mitchell saw it, it was in print.

Then the industry changed and the services of commercial fashion illustrators like herself became expendable.

“Instead of retailers hiring a graphic artist to draw their clothes or their shoes or whatever, they began taking photographs. It was less expensive. And so they no longer used fashion illustrations. Not even in big cities like Chicago and New York.

“I would say it became a lost art.”

©Mary Mitchell

Reinventing herself

The timeless beauty and the scarcity of commercial fashion illustrations explain why they are collectible artworks today and featured in fashion books and on fashion blogs. The Fashion Illustration Gallery in London is devoted entirely to the work of master fashion illustrators .

Denied her fashion illustration outlet, she continued designing in a new guise as vice president and art director of Young & Mitchell Advertising and as vice president of Mitchell Broadcasting.

Mary said she and John sold their Nebraska stations, which included Sweet 98 and KKAR,, just “as the big boys started coming in, like Clear Channel,” adding, “We sold them at the right time.”

Another whole segment of her design work is interior design. John and Mary became part owners of Le Versaille restaurant and ran that for several years. They decided to change the decor and Mary redesigned it from a red velvet and mirrored interior to a black, green, silver, and white decor with large photographs of French vineyards. She also designed the Blue Fox restaurant. She executed the concept and theme for the Golden Apple of Love Restaurant.

“It was incredible,” she said of these all-encompassing projects and the large canvas they gave her to work on.

Her home is another epic canvas she has poured her passion into.

“It’s indeed a pleasure to create your own space,” she said, referring to her chic residence that reflects her “contemporary” design palette. “I like clean lines and not a lot of frills. Basically black and white with some beautiful colors.”

©photo Jim Scholz

A well-designed life comes full circle

She and John have traveled to Greece several times. They took their son there when he was 11. The couple have remained close to their Greek heritage in other ways, too. They are longtime members of Omaha’s Greek Orthodox Church.

“I do speak Greek on occasion, and with my Greek friends, and so does my husband. We cook Greek foods for special occasions, as does my son and his family.”

After the sale of the radio stations in 2000, her life proceeded like that of many retirees, as she divided her days between travel, shopping, decorating, and spending time with John and Kathleen and their two grandchildren, John B. and Emily. She never expected the work she did way back when to be the focus of an exhibition and a book.

When still active as a fashion illustrator, it never crossed her mind to exhibit her work, she said, because commercial art was generally not considered museum or gallery worthy. That attitude has turned around in recent years. She is very much aware that the graphic art form she specialized in is making “a comeback” with young and old alike.

She has a collection of fashion illustration books and has her heart set on one day visiting London’s Fashion Illustration Gallery.

“I’d love to see it.”

Her illustrations might never have seen the light of day again if Anne Marie Kenny and Mary Jochim had not persevered and shown so much interest to exhibit them. Mary Mitchell is flattered by all the interest in this art form from so long ago.

There would be no exhibition or book if she had not preserved the original illustrations. She held onto enough that her personal collection numbers about 1,000 illustrations. It adds up to a life’s work.

The way she had carefully mounted the illustrations on framed and covered poster board panels and in portfolio books indicates the importance they have always held for her. Just as there was nothing haphazard in the way she created the works, she took great pains in preserving them for posterity.

Still, the illustrations would likely have remained tucked away in her home studio if not for the unexpected series of events that led to the book and exhibition.

Now, these valuable artworks and artifacts have a second life and Mary Mitchell suddenly finds herself the subject of renewed interest.

Harper’s Bazaar editor Glenda Bailey writes, “I love that Mary Mitchell brought such a high caliber of artistry to the local level. I was in fashion school in London in the 1980s, but when I look at the work of Mary drew for the women of Omaha at that time, her level of detail puts me right into the moment. To the casual viewer, Mary’s work appears effortless. But when you look more closely you see the precision and intention behind each brushstroke. She elevates each drawing to a tactile experience. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but a Mary Mitchell illustration is worth a thousand rustles of silk and crisp snaps of tweed.”

Mary never expected such a fuss, but she welcomes it. The timelessness of Mary Mitchell and her art now resonate with old and new audiences. The rediscovery of her work should ensure it lasts for generations to come.

To view more of Mary’s art and to buy her book, visit www.drawntofashion.com. For details on the Durham exhibition, visit www.durhammuseum.org.

Related articles

- Fashion Illustration (evawilsonart.wordpress.com)

- Iconic Fashion Illustrations – The Epherma Friends Watercolors are Stunning (TrendHunter.com) (trendhunter.com)

- Illustrated Elizabeth Taylor (fashionising.com)

- 100 Years of Fashion Illustration Reviews (fclothes.com)

- Fashion Illustrated: Kareem Iliya (thelookbookphilosophy.com)

- feeling bookish (thecolorkaleidoscope.com)

- The Art Of The Fashion Illustration (justbeestylish.wordpress.com)

- Go Figure: New Fashion Illustration @ the Fashion Space Gallery (irenebrination.typepad.com)

Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Never is anyone simply what they appear to be on the surface. Deep rivers run on the inisde of even the most seemingly easy to peg personalties and lives. Many of those well guarded currents cannot be seen unless we take the time to get to know someone and they reveal what’s on the inside. But seeing the complexity of what is there requires that we also put aside our blinders of assumptions and perceptions. That’s when we learn that no one is ever one thing or another. Take the late Charles Bryant. He was indeed as tough as his outward appearance and exploits as a one-time football and wrestling competitor suggested. But as I found he was also a man who carried around with him great wounds, a depth of feelings, and an artist’s sensitivity that by the time I met him, when he was old and only a few years from passing, he openly expressed.

My profile of Bryant was originally written for the New Horizons and then when I was commissioned to write a series on Omaha’s Black Sports Legends entitled, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, I incorporated this piece into that collection. You can read several more of my stories from that series on this blog, including profiles of Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, and Johnny Rodgers.

Charles Bryant at UNL

Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons and The Reader (www.thereader.com)

“I am a Lonely Man, without Love…Love seems like a Fire many miles away. I can see the smoke and imagine the Heat. I travel to the Fire and when I arrive the Fire is out and all is Grey ashes…

–– “Lonely Man” by Charles Bryant, from his I’ve Been Along book of poems

Life for Charles Bryant once revolved around athletics. The Omaha native dominated on the gridiron and mat for Omaha South High and the University of Nebraska before entering education and carving out a top prep coaching career. Now a robust 70, the still formidable Bryant has lately reinvented himself as an artist, painting and sculpting with the same passion that once stoked his competitive fire.

Bryant has long been a restless sort searching for a means of self-expression. As a young man he was always doing something with his hands, whether shining shoes or lugging ice or drawing things or crafting woodwork or swinging a bat or throwing a ball. A self-described loner then, his growing up poor and black in white south Omaha only made him feel more apart. Too often, he said, people made him feel unwelcome.

“They considered themselves better than I. The pain and resentment are still there.” Too often his own ornery nature estranged him from others. “I didn’t fit in anywhere. Nobody wanted to be around me because I was so volatile, so disruptive, so feisty. I was independent. Headstrong. I never followed convention. If I would have known that then, I would have been an artist all along,” he said from the north Omaha home he shares with his wife of nearly hald-a-century, Mollie.

Athletics provided a release for all the turbulence inside him and other poor kids. “I think athletics was a relief from the pressures we felt,” he said. He made the south side’s playing fields and gymnasiums his personal proving ground and emotional outlet. His ferocious play at guard and linebacker demanded respect.

“I was tenacious. I was mean. Tough as nails. Pain was nothing. If you hit me I was going to hit you back. When you played across from me you had to play the whole game. It was like war to me every day I went out there. I was just a fierce competitor. I guess it came from the fact that I felt on a football field I was finally equal. You couldn’t hide from me out there.”

Even as a youth he was always a little faster, a little tougher, a little stronger than his schoolmates. He played whatever sport was in season. While only a teen he organized and coached young neighborhood kids. Even then he was made a prisoner of color when, at 14, he was barred from coaching in York, Neb., where the all-white midget-level baseball team he’d led to the playoffs was competing.

Still, he did not let obstacles like racism stand in his way. “Whatever it took for me to do something, I did it. I hung in there. I have never quit anything in my life. I have a force behind me.”

Bryant’s drive to succeed helped him excel in football and wrestling. He also competed in prep baseball and track. Once he came under the tutelage of South High coach Conrad “Corney” Collin, he set his sights on playing for NU. He had followed the stellar career of past South High football star Tom Novak — “The toughest guy I’ve seen on a football field.” — already a Husker legend by the time Bryant came along. But after earning 1950 all-state football honors his senior year, Bryant was disappointed to find no colleges recruiting him. In that pre-Civil Rights era athletic programs at NU, like those at many other schools, were not integrated. Scholarships were reserved for whites. Other than Tom Carodine of Boys Town, who arrived shortly before Bryant but was later kicked off the team, Bryant was the first African-American ballplayer there since 1913.

No matter, Bryant walked-on at the urging of Collin, a dandy of a disciplinarian whom Bryant said “played an important role in my life.” It happened this way: Upon graduating from South two of Bryant’s white teammates were offered scholarships, but not him; then Bryant followed his coach’s advice to “go with those guys down to Lincoln.’” Bryant did. It took guts. Here was a lone black kid walking up to crusty head coach Bill Glassford and his all-white squad and telling them he was going to play, like it or not. He vowed to return and earn his spot on the team. He kept the promise, too.

“I went back home and made enough money to pay my own way. I knew the reason they didn’t want me to play was because I was black, but that didn’t bother me because Corney Collin sent me there to play football and there was nothing in the world that was going to stop me.”

Collin had stood by him before, like the time when the Packers baseball team arrived by bus for a game in Hastings and the locals informed the big city visitors that Bryant, the lone black on the team, was barred from playing. “Coach said, ‘If he can’t play, we won’t be here,’ and we all got on the bus and left. He didn’t say a word to me, but he put himself on the line for me.”

Bryant had few other allies in his corner. But those there were he fondly recalls as “my heroes.” In general though blacks were discouraged, ignored, condescended. They were expected to fail or settle for less. For example, when Bryant told people of his plans to play ball at NU, he was met with cold incredulity or doubt.

“One guy I graduated with said, ‘I’ll see you in six weeks when you flunk out.’ A black guy I knew said, ‘Why don’t you stay here and work in the packing houses?’ All that just made me want to prove myself more to them, and to me. I was really focused. My attitude was, ‘I’m going to make it, so the hell with you.’”

Bryant brought this hard-shell attitude with him to Lincoln and used it as a shield to weather the rough spots, like the death of his mother when he was a senior, and as a buffer against the prejudice he encountered there, like the racial slurs slung his way or the times he had to stay apart from the team on road trips.

As one of only a few blacks on campus, every day posed a challenge. He felt “constantly tested.” On the field he could at least let off steam and “bang somebody” who got out of line. There was another facet to him though. One he rarely shared with anyone but those closest to him. It was a creative, perceptive side that saw him write poetry (he placed in a university poetry contest), “make beautiful, intricate designs in wood” and “earn As in anthropolgy.”

Bryant’s days at NU got a little easier when two black teammates joined him his sophomore year (when he was finally granted the scholarship he’d been denied.). Still, he only made it with the help of his faith and the support of friends, among them teammate Max Kitzelman (“Max saved me. He made sure nobody bothered me.”) professor of anthropology Dr. John Champe (“He took care of me for four years.”) former NU trainers Paul Schneider and George Sullivan (who once sewed 22 stitches in a split lip Bryant suffered when hit in the chops against Minnesota), and sports information director emeritus Don Bryant.

“I always had an angel there to take care of me. I guess they realized the stranger in me.”

Charles Bryant’s perseverance paid off when, as a senior, he was named All-Big Seven and honorable mention All-American in football and all-league in wrestling (He was inducted in the NU Football Hall of Fame in 1987.). He also became the first Bryant (the family is sixth generation Nebraskan) to graduate from college when he earned a bachelor’s degree in education in 1955.

He gave pro football a try with the Green Bay Packers, lasting until the final cut (Years later he gave the game a last hurrah as a lineman with the semi-pro Omaha Mustangs). Back home, he applied for teaching-coaching positions with OPS but was stonewalled. To support he and Mollie — they met at the storied Dreamland Ballroom on North 24th Street and married three months later — he took a job at Brandeis Department Store, becoming its first black male salesperson.

After working as a sub with the Council Bluffs Public Schools he was hired full-time in 1961, spending the bulk of his Iowa career at Thomas Jefferson High School. At T.J. he built a powerhouse wrestling program, with his teams regularly whipping Metro Conference squads.

In the 1970s OPS finally hired him, first as assistant principal at Benson High, then as assistant principal and athletic director at Bryan, and later as a student personnel assistant (“one of the best jobs I’ve ever had”) in the TAC Building. Someone who has long known and admired Bryant is University of Nebraska at Omaha wrestling Head Coach Mike Denney, who coached for and against him at Bryan.

Said Denney, “He’s from the old school. A tough, hard-nosed straight shooter. He also has a very sensitive, caring side. I’ve always respected how he’s developed all aspects of himself. Writing. Reading widely. Making art. Going from coaching and teaching into administration. He’s a man of real class and dignity.”

Bryant found a new mode of expression as a stern but loving father — he and Mollie raised five children — and as a no-nonsense coach and educator. Although officially retired, he still works as an OPS substitute teacher. What excites him about working with youth?

“The ability to, one-on-one, aid and assist a kid in charting his or her own course of action. To give him or her the path to what it takes to be a good man or woman. My great hope is I can make a change in the life of every kid I touch. I try to give kids hope and let them see the greatness in them. It fascinates me what you can to do mold kids. It’s like working in clay.”

Since taking up art 10 years ago, he has found the newest, perhaps the strongest medium for his voice. He works in a variety of media, often rendering compelling faces in bold strokes and vibrant colors, but it is sculpture that has most captured his imagination.

“When I’m working in clay I can feel the blessings of Jesus Christ in my hands. I can sit down in my basement and just get lost in the work.”

Recently, he sold his bronze bust of a buffalo soldier for $5,000. Local artist Les Bruning, whose foundry fired the piece, said of his work, “He has a good eye and a good hand. He has a mature style and a real feel for geometric preciseness in his work. I think he’s doing a great job. I’d like to see more from him.”

Bryant has brought his talent and enthusiasm for art to his work with youths. A few summers ago he assisted a group of kids painting murals at Sacred Heart Catholic Church. He directs a weekly art class at Clair Memorial United Methodist Church, where he worships and teaches Sunday School.

Much of Bryant’s art, including a book of poems he published in the ‘70s, deals with the black experience. He explores the pain and pride of his people, he said, because “black people need black identification. This kind of art is really a foundation for our ego. Every time we go out in the world we have to prove ourselves. Nobody knows what we’ve been through. Few know the contributions we’ve made. I guess I’m trying to make sure our legacy endures. Every time I give one of my pieces of art to kids I work with their eyes just light up.”

These days Bryant is devoting most of his time to his ailing wife, Mollie, the only person who’s really ever understood him. He can’t stand the thought of losing her and being alone again.

“But I shall not give in to loneliness. One day I shall reach my True Love and My fire shall burn with the Feeling of Love.”

–– from his poem “Lonely Man”

Related articles

- A Family Thing, Bryant-Fisher Family Reunion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Green Bay Packers All-Pro Running Back Ahman Green Channels Comic Book Hero Batman and Gridiron Icons Walter Payton and Bo Jackson on the Field (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

A Passion for Conservation: Tara Kennedy

I normally wouldn’t seek out a story about paper conservation, but when I read a reference by the hosts of national public radio’s The Book Guys to paper conservator Tara Kennedy, whom they described in very engaging terms, I was intrigued enough to seek her out for an interview. I’m glad I did because she proved every bit as engaging as advertised and the following profile I wrote about her is the result.

A Passion for Conservation: Tara Kennedy

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Every object passing through the hands of Tara Kennedy, the fetching paper conservator at Omaha’s Gerald R. Ford Conservation Center, is filled with what she calls “life history.” That’s certainly the case with three historic Meriwether Lewis and William Clark documents she’s now conserving. She’s preparing the documents, which accompanied the explorers’ on their 1804-06 Journey of Discovery, for a July 30 through August 3 public exhibition at Fort Atkinson State Historical Park. The display is one of many area events being held in conjunction with the 200th anniversary of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

The materials belong to the Oklahoma State Historical Society. One is a Lewis and Clark signed account of an address delivered by Lewis to a band of Yankton Sioux Indians at Calumet Bluff in present-day northeastern Nebraska. Another is a peace medal certificate signed by the explorers and presented to an Otoe warrior, Big Ax, at Fish Camp — an expedition bivouac south of today’s Dakota City, Neb. The third is a letter in French, signed by Thomas Jefferson, inviting tribal leaders of the Otoe-Missouria and other Indian nations to visit him in Washington, D.C.

Kennedy’s assessment of the documents’ condition — revealing varied wear and damage — determined what conservation to do or not do. “I must have an informed cultural respect for the items I work with, such as the history of the period and the materials used then,” she said. The letter’s in bad enough shape she’s doing a wash to remove tape and acidic residue. The other pieces require less work. The well-traveled Calumet Bluff piece, complete with original binding, “tells its life history,” she said. “It wasn’t something that laid around in a drawer or hung on a wall. It was carried by horseback…stuffed into pockets. It got wet, and then for decades it was bundled up in a trunk. It’s a well-loved document.”

As conservators go, Kennedy’s anything but the shy, retiring type associated with her profession. Away from her job at the Ford Center, this self-described “extrovert” acts in local community theater productions. Her stage work ranges from quirky roles at the Shelterbelt to playing perky Nellie Forbush, the object of Some Enchanted Evening seduction in a Chanticleer Theater staging of South Pacific. She’s currently appearing in the Ralston Community Theatre production of Into the Woods at the Bellevue Little Theatre. She also enjoys singing, playing guitar and piano and listening to jazz, blues, swing, punk and indie rock.

“I can’t live without music and art,” said Kennedy, who exudes the bonhomie of a Bohemian beat poet with her chic looks, casual clothes and earthy charms.

When not living-out-loud, she’s content toiling away alone in the center’s paper conservation laboratory, an open, airy, antiseptic-looking space broken up by storage cabinets, sinks, tables, vents and examination instruments. There, in the sterile isolation of her lab, she applies her training in paper technology and art history to the conservation of rare and precious paper objects. Only the music blaring from a boom box belies her more animated side.

As this region’s only paper conservator, she tends to such objects as birth certificates, works of art, maps, books, manuscripts, newspapers, photos, documents and “pretty much anything on paper” collectors or curators need preserved. A division of the Nebraska State Historical Society, the center devotes much of its resources to the NSHS’s collections.

Describing her work, Kennedy points out the difference between conservation and restoration. “In conservation, we try to stabilize an object — to retain the information that’s there. We’re not interested necessarily in what I like to say is ‘tarting it up’ — in making it look like it did when it was first created. That’s restoration,” she said. “In some cases, that is what the client wants. We try to dissuade them from that because it’s almost like you’re falsifying the piece. I mean, the piece had a history. It may be 150 years old. It’s not going to look brand new.”

Sometimes, she added, “the only way to improve a piece’s condition and appearance is to use artists’ techniques to disguise damage.” For those occasions, she keeps a ready supply of pastels, paints and other art materials.

She said “the marriage of art and science” that is her work “is what attracted me in the first place to make it my career path. I enjoyed chemistry in high school, but I didn’t want to be a chemist. I always enjoyed objects of history and I used to wonder how things were preserved. As a girl I remember looking inside an exhibit case at Monticello (Thomas Jefferson’s historic Virginia estate) and wondering about the objects and their condition. These objects had been unearthed on the property and I remember wondering, How’d they get all the dirt off them?”

But it was acting, not conservation, she originally pursued. Growing up in Kingston, New York, West Caldwell, New Jersey and Southington, Connecticut, she acted “rabidly” in youth theater and enrolled in Northwestern University’s prestigious dramatic arts program. After “really enjoying” some art history courses, she switched majors. “I thought there was no way I could combine the arts, history and chemistry until I visited this conservation lab. It was sort of like a bolt of lightning.” Cinching the deal was her studying abroad in Europe, followed by post-grad work at the University of Texas-Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, an internship at the National Archives and a fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution.

When she heard about the opening at the Ford Center in Omaha, she said, “I had to look it up on a map. Conservators are snobs. Nobody wants to leave the east coast. I still think the east coast is the place to be. I’m terribly biased in that respect. I applied here (the Ford Center) and at the New York Public Library, and they both offered me a job. But this job was far superior to that one. So, no-brainer, I was going to Omaha. Why not? And, so, here I am.”

As much satisfaction as she derives from conserving the splendid paper objects entrusted to her, she enjoys leaving the lab to slake her thirst for art at far-flung exhibits or to heed the extrovert in her. Whether greeting visitors, leading tours or making appearances on the nationally syndicated public radio show, The Book Guys, she displays her characteristic high energy, sharp wit and engaging laugh. One of the appealing things to her about the post, which she came to from the Smithsonian in 2001, is the multifaceted work and “the public face” it allows her.

“It’s a real diverse job. I get bored with things pretty easily. I have to have a million things to do. Here, I do the behind the scenes work that makes up a lot of conservation work, but I also get to go out and give lectures and do assessments at cultural institutions. And, being a regional center, a variety of people come in with a variety of materials. I get to have more contact with the public, and I enjoy interacting with people,” she said. “It’s an element you don’t normally get with other conservation positions.”

Then there’s The Book Guys gig. When the show came to tape at the W. Dale Clark Library in the spring of 2003, then-Library Foundation Director Marcy Cotton hooked Kennedy up with hosts/producers Allan Stypeck and Mike Cuthbert, who were taken with her. “They put me on the air and sprang me with some weird questions,” Kennedy said. “They asked me about the use of kitty litter in removing odor from books and they were impressed I knew the answer. And they liked my laugh…and so they decided I would be the official preservation-conservation consul for The Book Guys. I think the conservators they’d encountered were not extroverted.” Since her debut, she’s been called on again to answer queries, and it was during one of these segments when Cuthbert referred on-air to the single, 20-something Kennedy as “a hottie from Omaha,” a designation she feigns to be upset by. “Here I am trying to be this serious professional and, yeah, now I’m the Omaha hottie. Thanks guys.”

Programs like The Book Guys and PBS’s Antiques Road Show have “really increased appreciation and awareness in the preservation of artifacts,” she said. No sooner does she say that, however, than she comes back with, “I don’t watch it (Antiques) myself. I’d rather watch forensics science shows.”

Indeed, her work is not so different from a crime scene investigator’s as she explores, with gloved hands, the composition, age and condition of fragile objects and the best ways for conserving the integrity of those pieces. Showing a visitor around the center’s labs one day, Kennedy quipped, “It’s a regular CSI in here,” as she strode about the microscopes, lights, scalpels, cotton swabs, brushes, acid solutions, water baths, fumidors and elephant venting trunks arrayed about her.

“We have a microscopy lab in which we can actually do microscopic examination of fibers, inks…that sort of thing. I’ve had to do technical exams on pieces to find out, for example, what kind of pulp was used to make a paper. Usually, it’s to determine age, as part of an authentication process, although it can also be a method of deciding what kind of treatment to do. I extract micro pieces from a document and take them in the microscopy lab and identify…if it’s wood or linen or cotton. We have different kinds of light sources — infrared, ultraviolet — to use for examination. That’s usually to find inconsistencies in the paper.”

Often times, the documents she treats require removing tape. Different methods, including heat and solvents, are used with different kinds of adhesives.

The conservation called for by a project can find her doing everything from tamping down loose pieces of a collage to removing an insect infestation from a print. In the case of the collage, she said, “the artist used a spray adhesive that over time lost its tack, resulting in pieces popping up. So, I had to go in basically and tack them back down. A lot of times, artists will use materials that aren’t necessarily the most stable.” With the print, she said, “the glazing on the framing package was plexiglass, which has a lot of static, and the insects might have got sucked in during framing. I don’t think they were actually alive.”

The objects she examines and treats may be valued at anywhere from a few bucks to millions of dollars, although, she said, there can be no favorites. “We are expected to treat all objects exactly the same. We have to take great care with everything because it means something to someone, whatever it might be.”

But applying the same dispassionate approach to the priceless Louisiana Purchase Proclamation, which she examined at the center, or to a Jean Miro print, which she conserved last year, as she does, say, to just another birth certificate, is not easy. “It’s hard to separate out your emotions sometimes. But no matter what the monetary value of a piece, I’m still like, ‘Oh, it’s only a piece of paper.’” The exception, she said, comes “if I have a particular passion for an artist. Then, I think it would be very hard for me to do treatment. I almost have to remain detached.”

For the Thomas Jefferson-signed Louisiana Purchase Proclamation, owned by Walter Scott, Jr. of Omaha, Kennedy did a technical exam to authenticate it. “I took very, very tiny pieces from the document and examined them to determine what kind of paper pulp was used. It was a certain kind of paper I would not have expected in a document from 1803, so I was a little suspect at first. But it turns out it was an extremely early version of what’s called wove paper. The determining factor was a water mark on the paper. We did research on water marks, and there was an English manufacturer of paper that Thomas Jefferson did use and so that became a direct link to him. That really solidified it on top of the fact the paper was made of the right material and there were no inconsistencies in the writing and other types of tests I did, including whether any fillers used might be modern.”

The bound, 16-leaf Proclamation was treated by other conservators over the years, sometimes to its detriment. “A ribbon once woven through three binding holes had been removed and the holes filled…and that’s a shame,” she said, “because that’s lost information. That’s the kind of information that as a conservator you want to retain because it’s part of the object. And considering what it is and the history of it, you want all its pieces intact.” Despite its pedigree, Kennedy said the document is “very unassuming…only because it’s the proclamation for the Louisiana Purchase, which basically means it was a fancy press release.”

More Jeffersonian documents came her way when she was commissioned to assess and conserve the Lewis and Clark papers she’s now working with. “We’re thrilled to have these documents in her hands and to have them conserved in a way that gets them in appropriate condition for exhibition,” said Jeff Briley, assistant director of the Oklahoma State Historical Museum in Oklahoma City.

Then there was the painting she treated by contemporary realist Andrew Wyeth, a superstar among artists. “That was pretty intimidating, but very exciting, too,” she said. “Fortunately, I didn’t have to do a very invasive treatment on it. It’s great to see an artist’s work up close like that. Wyeth actually roughed up the paper and made it almost three-dimensional by scraping and cutting it to bring out the grasses. It’s things like that I need to be sensitive to because that means there are some undulations in the paper and I have to see that’s an artist’s technique that needs to be maintained in the piece, even if that means I’m not able to do certain things that might help conserve the object overall.

“If it’s an artist I’m not familiar with, I will take time to find out more about that artist’s working techniques before I proceed with treatment.”

Prestige, big-ticket items like the Wyeth painting used to make her anxious, but now they are par for the course. “I don’t get nervous anymore about it. Besides, I can’t really be frozen in fear. I have to do my work no matter what. But something’s sure to come along that will make me nervous.” She already knows which artist’s work would test her composure. French post-impressionist Edouard Vuillard, a leader of the avant-garde Nabi movement, “is an artist I adore,” said Kennedy, keenly aware a private collection of his work is in Iowa. “His compositions are very warm. He worked in really horrible media, though, so I’m not sure I’d want to treat one. It would be an incredible challenge.”

Her affection for Vuillard, who used oils, inks, washes on everything from boards, panels and screens to theater programs, is such she recently traveled to a retrospective of his work at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. “I venture to go see particular works of art I haven’t seen in person. For example, I make it my life’s ambition to see every Vermeer before I die. A couple years ago I went to London to see one at the Kenwood House. I sat there and cried staring at this piece. The serenity in his figures is just unbelievable. I’m amazed at how anyone can capture that. Nothing prepares you for the beauty of something in person you’ve only seen in books.”

Epiphanies like those only reinforce why she’s dedicated to preserving, as conservators like to say, the cultural heritage. “I feel very good and proud about what I do every day,” she said. “It doesn’t necessarily define me, but it fulfills me.”

Related articles

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne – Portrait of a Young Filmmaker (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Lit Fest: ‘People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Exhibit by photographer Jim Krantz and his artist grandfather, the late David Bialac engages in an art conversation through the generations

A few weeks ago I mentioned I would be posting a story about another photographer you should know about, and here it is. His name is Jim Krantz and he does work of the highest order, so high in fact that he was named Advertising Photographer of the Year by the International Photography Awards in 2010 and International Photographer of the Year at the IPAs Lucie Awards. Jim has an exhibition opening in his hometown of Omaha on Nov. 4 that has deep meaning for him because it displays his work alongside that of the man who first inspired and nurtured his artistic leanings and who gave him his first camera – his late grandfather David Bialac, who was an artist himself. Look for my story in next week’s The Reader (www.thereader.com). If you’re into photography and to stories about the journeys that photographers make in their life and work, then you’ll find plenty of captivating things to see and read on this blog. You’ll find stories here on such noted photographers as Larry Ferguson, Don Doll, Monte Kruse, Pat Drickey, Jim Hendrickson, Rudy Smith, and Ken Jarecke. You can choose their stories individually by clicking on their names in the Categories listing on the right or just choose Photography. Or you can search for my stories about them in the search box.

NOTE: The Krantz-Bialac show is called Generations Shared and it runs Nov. 4-27 at the Anderson O’Brien Gallery in Omaha’s Old Market.

Exhibit by photographer Jim Krantz and his artist grandfather, the late David Bialac engages in an art conversation through the generations

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to be published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

An aesthetic conversation that began decades ago continues in Generations Shared. The Nov. 4 through 27 exhibition features work by internationally renowned photographer Jim Krantz alongside that of his late maternal grandfather, David Bialac, an Omaha painter, sculptor and fine furniture-maker who was Krantz’s first and perhaps most important artistic mentor.

Krantz, who assisted Bialac for a time, says, “My grandpa had a very good reputation.” Krantz believes Bialac (1905-1978) should be better known and more appreciated today. He views the new exhibition at Anderson O’Brien Gallery in the Old Market as a tribute to the man he credits with kindling his own creative passion.

The tribute subject owned Dave Bialac Builders in northeast Omaha. At his 52nd and Hamilton Streets home studio he developed an alchemy-like enameling process that involved arranging multi-colored glass shards and powder on glass and copper plates and then firing them in a kiln. The bonded-fused objects took on trippy abstract patterns. His distinctive work adorned custom kitchens and decorative installations and sculptures he designed for some of Omaha’s most distinctive homes and public-private spaces, such as the Mutual of Omaha lobby.

“He signed his pieces,” says Bialac. “There was a lot of pride and craftsmanship in what he did. He did custom woodworking for a living but his real passion was his artwork.”

Every Saturday morning Krantz, the devoted young grandson, joined Bialac in his home studio for what the old man jokingly called “baking cookies.” The self-taught abstract expressionist and his boy apprentice made this a ritual for years. After Bialac suffered a severe stroke he gave Jimmy access to an expressive tool all his own via the studio camera he kept to document his work: a Minolta SR-T 101.

Krantz recalls his grandfather’s wizened admonition: “Jimmy, I want you to work with this camera. Make some pictures, but remember the kinds of things we did in the studio.” It proved an irresistible invitation for the protege. Out of obligation to his elder and his own curiosity Krantz experimented. The camera might as well have been a new appendage as inseparable as he and the Minolta became.

Their contract called for Krantz to return the camera once Bialac recovered, so they could resume working together. Bialac never got better. “It was a shame because he was an amazing, vital, creative force trapped in his body after the stroke. It’s got to be the most debilitating thing because his mind was racing and there was no way to respond. So all I was left with was memories and a camera,” says Krantz, who went on to study photography and earn a design degree.

As a professional Krantz gained a rep as a visual stylist who makes any shoot, regardless of subject matter, a rigorous exploration of light, space, form, shadow. He conquered the Omaha ad market before moving to Chicago 12 years ago.

Today, Krantz enjoys a high-end career as a advertising, documentary and art photographer traveling the world for Fortune 500 clients and personal projects. His signature commercial work came on a Marlboro tobacco campaign. His post-modern The Way of the West imagery earned him International Photography of the Year prizes as 2010’s best advertising photographer and top overall photographer.

The Way of the West, ©photo by Jim Krantz

More recently his images from inside the forbidden zone of Russia’s Chernobyl nuclear disaster have captured attention via his book and exhibition, Homage: Remembering Chernobyl. His Chernobyl work comes to KANEKO in April.

The Chicago-based Krantz, who retains strong Omaha ties, loves the idea of showing his work with that of his Saturday morning studio session mentor. More than most exhibits, the show examines creativity as legacy, a theme much on Krantz’s mind as his career’s reached new heights and he’s recognized how indebted he is to teachers like his grandfather.

He speaks of feeling connected to Bialac and sensing his guiding hand. As a kid, he never considered those weekend idylls with “Poppy” as classes, but in retrospect they were. Among the lessons taught: focus and discipline.

“He was a very warm and loving guy but he was very concentrated on this stuff,” says Krantz.

As the boy alchemist’s helper, Krantz says he’d studiously watch his grandfather manipulating “threads of glass on a plate, then staring at it, and with tweezers moving it in such a nuance of a move” before transferring them to the kiln. “I had no idea what he was doing — all I knew was this was serious shit.”

“My grandpa was a very eccentric man, I have to say, doing very abstract, very unusual things. I’m telling you, this guy was out there, but he had this quality of craftsmanship. He’d take his copper enameling and then he’d build big huge installations of wood furniture and whatever and they’d all be applied to the furniture. His work’s amazing. Really quite strong. Really beautifully crafted.”

The Krantz family possesses a nice collection of Bialac’s work, but many pieces have been lost to time.

Krantz describes Bialac as someone who straddled the Old World and Modern Age as a creative.

“He was from another generation,” says Krantz. “I don’t even know where he got his initial inspiration because he came from working class type people and he got sidetracked somehow deep into very abstract thinking, concepts, art, color and design, and then it evolved into sculpture with natural elements and all of these things — brass, rock, metal, glass, enamel.”

The studio where he and Bialac bonded over art is fixed in Krantz’s mind.

“I remember it so well. It was an immaculately beautiful space, really organized. A very busy shop. You could just tell he was really meticulous and thoughtful about everything he did. I remember the work that came out of it was so different than the setting. I’m not saying clinical but it’s funny how the space did not feel like the product, which was kind of very free form and organic. That’s why process was so important to him.”

As time goes by Krantz feels ever more the reverberations of Bialac’s work in his own.

“Over the years I’ve been looking back at my work and his work and it’s like the parallels are so strikingly similar, even in our own visual vocabulary, and I know it’s all from just literally every Saturday standing by this guy’s side watching him work. It’s just part of me.”

Most of their communication was nonverbal, with Kranz observing his grandfather communing with pieces, responding to subtle variations, tweaking this or that. And while they never formally discussed methodology, Krantz gleaned some direction for his own artistry and field of vision. He realizes now he adopted, intuitively, from Bialac a way of apprehending the world.

“I did the same thing with the camera he did pushing those little things around. I was always aware of everything I saw in the viewfinder because he always told me, ‘What you see on this plate — how do all these things fit?’I put a camera to my eye and I see a rectangle. There’s a tree branch here and a rock there and a person over here. All of these things become abstract shapes.

“It isn’t so much documenting, it’s arranging. So I started to learn at an early age that I can look through this camera just like I looked at that plate. Once you have the shapes in the right spot then you can relate to them on a more personal level. The thing that was wired into me early was I knew how to put things on that plate and I could transfer it to the rectangle of a camera.”

He doesn’t know why his grandfather offered him the camera but suspects he noted in him a kindred spirit. “It’s possible he was predisposed to it, I was predisposed to it,” and the camera served as connective medium. Whatever the reason, Krantz found in photography what he’d never had before and gladly lost himself in.

In his artist’s statement he writes, “My camera became a part of me and I photographed everything I saw…and have never stopped.” Like Bialac’s work, photography is a process. It begins with a camera and subject, then knowing where to stand and when to shoot, taking the shot and finally developing and printing the image. Not so different than what goes into making a three-dimensional art object. Leaving oneself open to interpreting and discovering things is key.

As Krantz writes, “Photography, too, had the familiar quality of surprise I was accustomed to when the enameled ‘cookies’ would emerge from the kiln.”

Photography gave this “dorky kid” a potent process to call his own. “All of a sudden I had a little bit of an identity. Everybody loves to have something you do.” He says his open-minded parents (his family owns Allen Furniture) provided the freedom to pursue his passion “as far as photography could carry me. They knew I loved it. They encouraged me.” At 18 Krantz was so enthralled by the expressive possibilities he built his own darkroom at home and began educating himself.

He described his magnificent obsession to Rangefinder Magazine:

“I was amazed by the process in the darkroom and was swept up by the art and science of photography. I searched out books and images from every source and grew very attracted to the West Coast photographers, studying the work of (Ansel) Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Wynn Bullock, Minor White…”

A very young Jim Krantz with an iconic mentor, Ansel Adams, ©photo Jim Krantz

His parents agreed to his driving his Renault, alone, to Calif. to take a workshop from the great Yosemite documenter, Ansel Adams. Krantz had just graduated from Westside High. On his website, www.jimkrantz.com, is a picture of Krantz, looking even younger than his years, posed beside the icon’s home mailbox. Other pictures show the acolyte with the veteran imagemaker in candid moments.

The first day Krantz met Adams he ended up printing images with him in his state-of-the-art darkroom. “I was nervous, I was unsure of myself.” He recalls few details other than the bearded sage offering critiques of his beginner’s work.

Krantz felt compelled to learn everything he could and venturing off to seek a master’s advice was part of that. “I just had the sense this was something I had to do,” he says. In Adams he found a grandfather surrogate.

“It was very familiar. Adams talked about arrangement, shape, form, tonality. I thought, ‘This is the same thing I learned from my grandpa.’ Both were very passionate, focused, attached.”

The icon’s approach to nature informed how Krantz treated grand landscapes. Krantz repeated that 1970s trek west multiple times to work with Adams. “I’d drive out there, take a workshop, and come home all inspired. I was always the youngest one in the class.” “Now,” adds Krantz, who’s continued taking workshops from other photographers, “I’m the oldest guy in class.”

The workshops are intensive immersion experiences he throws himself into and comes out of reinvigorated. “I continue to go and I continue to learn.”