Archive

Hadley Heavin’s Idiosyncratic Journey as a Real Rootin-Tootin, Classical Guitar Playing Cowboy

I first met Hadley Heavin 20 years ago. He was one of the first profile subjects I wrote about as a freelance journalist. I loved telling his story then, and I always knew I would return to it. I did a few years ago. Upon catching up with him, I found him and his story just as intriguing as I had before. It’s not often you find someone who combines the passions he does, namely competing in rodeo and performing classical guitar. He is a singular man whose twin magnificent obsessions make him one of my favorite and most unforgettable characters.

Hadley Heavin’s Idiosyncratic Journey as a Real Rootin-Tootin, Classical Guitar Playing Cowboy

©by Leo Adam Biga

Versions of this long story originally appeared in Nebraska Life Magazine and The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Traditional Spanish classical guitar follows certain lines. It flows most directly from the source of this passionate art form, Francisco Tarrega, the father of Spanish classical guitar at the turn of the last century. Tarrega passed on his legacy to his musical progeny, a few prized pupils, who in turn taught it to select disciples, and so on down the line.

Improbably, this line of maestros, the great interpreters of Spanish classical guitar, includes a longtime area resident and an American to boot, Hadley Heavin. He grew up a cowboy, jock and blues-rock lead guitar player in Baxter Springs, Kansas. He learned guitar at 5, began riding horses soon after, adding rodeo, football, basketball, track and baseball. The Vietnam combat vet has been a University of Nebraska at Omaha music instructor since 1982.

Beginning in the late ‘70s, Heavin became the primary student of the late Segundo Pastor. Decades-before, Pastor was the favorite student of Daniel Fortea, once the anointed disciple of Tarrega himself. So it is this direct Spanish line goes from Tarrega to Fortea to Pastor to Heavin.

“… there’s a real lineage that goes to the source of classical guitar in Spain that’s been handed down to me, almost by rote. Not even Spaniards have that,” Heavin said. “That’s why Spanish music is it for me. And when I play Spanish music I play it very much probably how Tarrega played it, because it was passed down that way. I’m probably just one of a handful of people in the world that got that experience.

“It isn’t so much about reading the notes and learning the music as it how the music is played.”

As if not’s unusual enough an American should be part of that rare Spanish line, then consider that at age 59 Heavin still competes in rodeos and horse shows around his busy teaching-performing schedule. The fact he’s both a concert-level artist and competitive roper never fails to surprise.

“It’s so odd to people that I do these two things,” he said.

He and his daughter Kaitlin share a small, white, wood-frame house on a 25-acre spread he rents in Valley, Neb.. He’s at home there with his dogs, horses and steers. There are barns for storing hay and boarding horses as well as pens, a round and an arena, complete with box and chute, for working stock and practicing roping. He has a horse trailer and a truck parked there. His precious guitars, a Brune for classical and a Cordoba for Flamenco, always near.

Much like his boyhood home, when impromptu family concerts broke out, the sound of Heavin playing and Kaitlin singing often blend with the music of cicadas, crickets, meadow larks, steers and horses.

In a kind of dual life he alternately spends weekends playing paying guitar gigs or riding-roping for prize money. One weekend might find him performing solo or with his new Latin-influenced band, Tablao, at trendy Omaha spots like Espana and the Corkscrew. Kaitlin is Tablao’s lead vocalist. Another weekend might find him competing in American Quarter Horse Association or Professional Rodeo Cowboy Association team-roping events in such Nebraska backyards as Wilber and Burwell.

At home in his frayed tank-top undershirt, dusty jeans and worn boots, he’s the Marlboro Man. For a big guy he sits light in the saddle. The way he expertly handles a horse makes clear he’s no weekend warrior playing cowboy. He’s the Real McCoy. With a pull of the reins, a bump of his spurs or the command of his voice, his old bay, Champ, obeys instantly as he puts the animal through its paces, starting at a walk, building to a trot, then going at a full gallop. Rough stock is in his blood.

Cut to Heavin, the artist, this time in a freshly-pressed flowered shirt, clean jeans and polished boots, making love with his guitar at the Espana tapas bar in Benson. As he sits on stage, cradling and stroking the instrument like a woman in his thickly-muscled arms, he is every inch the maestro. His posture erect, his fingering precise, his feel for the music complete, he makes the expressive sounds his own. From soft, gentle trills to full crescendo runs, it is a seduction. Given his roots in the music, when Heavin plays, one hears echoes of past maestros Tarrega, Fortea and Pastor, a privileged connection he’s ever conscious of.

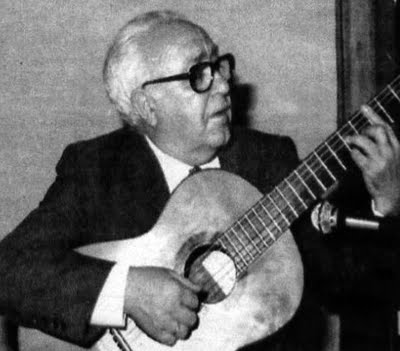

Hadley Heavin

His sound is so much like Pastor’s, he said, a good friend from Spain named Pedro once got upset that a gringo like him should be able to master it.

Pastor entered Heavin’s life at a key juncture. The then-angry young American was not long removed from a war that “scarred” him. Then, his father, “an incredible guitarist,” died at 47. “And there was no music anymore…” he said.

At the time Heavin worked a job unloading trucks in Springfield, Mo.. On a whim one night he went to see a classical guitarist perform, and Heavin’s life changed.

“I was enthralled and it just came over me like that,” he said, snapping his fingers. “Right then and there I knew what I was going to do with my life. The feeling that came over me fulfilled me more than anything else ever had up to that time.”

Why?

“Well, for a lot of reasons. A part of it was the war had scarred me and right after that my father passed away, and I needed something,” he said. “Classical guitar was the thread that gave me something to hang onto just to get through life and the pain I had lived with. The guitar was my salvation.”

He began by teaching himself via recordings and books. When he exhausted those he found an instructor, who soon did all he could for such a prodigy.

“I worked really hard,” Heavin said. “As soon as my hands could take it I was practicing six to eight hours a day and working a full-time job.”

He then brashly convinced the music dean at then-Southwest Missouri State University (now Missouri State) to start a degree guitar program with him as its first student.

“I had such a passion for it that I was going to find a way…whatever it took.”

Then, a meeting changed his life. Pastor was touring the U.S. and saw Heavin play a late ‘70s concert on campus. Pastor asked to meet Heavin.

Mind you, Heavin was just a beginner in classical guitar, yet the maestro plucked him from obscurity to make Heavin his sole student and the privileged inheritor of a rich music lineage he now passes onto his own students.

Heavin and Pastor enjoyed a decades-long friendship that saw the American study under the maestro in the U.S. and Spain. Heavin arranged for Pastor to perform UNO and Creighton concerts. They toured together. Heavin once performed with him at Carnegie Hall. Their friendship deepened.

“He was like a father and a mentor to me. He not only gave me a career, he gave me back myself,” Heavin said.

It’s not unlike how Heavin became a vessel for his father’s and his family’s legacies.

In his small hometown fast on the Oklahoma-Missouri border, Heavin was weaned on Ozarks culture. Music, horses and sports were family inheritances. From early childhood he excelled at them all.

His father, Ernest played with such bands as Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. Several uncles played, too. Heavin played trumpet and drums in bands his father led, traveling to gigs at VFW post and American Legion hall dances, performing swing, jazz, ragtime and country. The family home was alive with music, too.

“Making music,” Heavin said, “was just something we did. I grew up with music and I was a little freak because I could play really well. I grew up in an environment thinking everybody was like this. I couldn’t believe it when a kid couldn’t sing or carry a tune or do something with music.”

The life he leads today balancing music with rodeo is not so different than the one he knew as a youth. Heavin’s father paid him for the band gigs he played as a boy. Child or not, young Hadley was expected to carry his own weight.

“I remember about midnight I’d start falling asleep,” he said. “My dad would start to feel the time dragging and see me nodding. Then he’d flick me on the head with his fingertip and wake me up, and I’d speed up again.”

The paying dates made Heavin rich compared to his friends. “I’d be sitting with $20 in my pocket where everybody else would have a quarter.”

The grind of playing “got to be a chore.” He flirted with blues-rock groups for a time, but got “burned out” on music.

Classical was not even a possibility. Early ‘60s rural Kansas had few outlets for it. Heavin still recalls the first time he heard it. A Rachmaninoff concerto playing over a music store loudspeaker enraptured him on the spot. That was about the extent of his exposure until years later.

Sports and horses became his new means of expression. Athletics, like music, were another Heavin family forte. An uncle, Charles “Frog” Heavin, played minor league ball with Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle. Heavin’s own mother was a catcher in the women’s pro circuit immortalized in A League of Their Own.

He was introduced to horses courtesy his grandfather — a horse shoer and blacksmith — and youth rodeos. His first brush with rodeo came at age 12, an experience as dramatic for him as when he first heard classical guitar.

“I was at the fairgrounds and these guys were bucking out stock. Just practicing. I was sitting on the fence watching and I asked if I could ride one. They said sure. The first animal I rode was a bare back bronc, Mae Etta. I sat on her and I was kind of nervous and they told me what to do and that horse came out and started bucking and I rode her about three jumps and got bucked off.

“I just jumped up and said, ‘I gotta try that again.’ And I tried it again. I couldn’t wait…It was like the biggest rush I ever had in my life. Then I rode a bull. I loved that, too. That’s where it started.”

He progressed from Little Britches events to amateur competitions on up, earning his spurs along the way riding bulls and bare back broncs.

His folks “didn’t understand it,” he said. But he stuck with it. He’d found something of his own. “The thing I remember as a teenager is…I wasn’t really sure who I was, and rodeo really gave me a defining sort of picture of…what I needed for my own life. And that’s why I still do it on some level.”

As a teen he moved with his family to Lawrence. Kansas, where he lost himself in sports. He possessed enough talent that he owned state sprint records and got a look from Kansas University as a football halfback.

“I played every sport in high school but rodeo was my favorite. Once I got into roping and horses, I’ve just never gone back,” he said.

He enrolled at KU in 1967 with the military draft on his mind. He walked-on for football and made the freshman team.

The huge campus and sea of strange faces were “a major culture shock.” He took his chances with the draft and in ‘68 had the bad luck to be an Army conscript in an increasingly unpopular war.

Heavin was in-country 1969-70 as a forward observer and artillery fire officer with the 1st Field Force. He was shuttled from one LZ to another — wherever it was hot.

“I was what they called a ‘bastard.’ I would work with all different units. They would just send me wherever they needed me. I was on hill tops, some I can remember like LZ Lily. I was at Dactau and Ben Het during the siege. We were surrounded for like 30 days. I was in so many places I can’t remember them all. I was in the jungle the whole time…mostly in the north, in Two Corps, close to the border of Laos and Cambodia. I saw base camp twice,” he said.

Wounded by an AK47 round in a fire fight, he came home to recover. Stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, he impulsively entered the bare back at a local rodeo.

“I drew a pretty rank horse, plus I hadn’t ridden in years and I was still sore from my war injuries.” he said. “The horse came out and was bucking and bucked towards the fence and my spur hung in the fence and hung me upside down, facing the opposite way. He was kicking me in the back as he was bucking away from me. I got hurt. I could hardly walk that night. When I got back to the base they were mad at me because I couldn’t pull my duty. Here I was a decorated combat vet, and they were going to court-martial me.”

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed and the incident forgotten.

Back home he struggled with memories of the war and his father’s death. He floundered, looking to get his head right. He’d seen cruelty in the jungle. Fraggings. Buddies killed. Rapes, mutilations and killings of innocent Vietnamese women and children. “Emotionally, I was a mess from the war,” he said. “I had some years there where I had a hard time because I felt I was part of something that was wrong.”

He felt angry over what he viewed as U.S. betrayal of the South Vietnamese people. He wanted to forget it all, but couldn’t. He’d prefer to put it behind him today.

“When people find out I was in Vietnam they start asking a lot of questions and I find myself not wanting to deal with that issue at this point in my life,” he said.

He harbors hard feelings about U.S. military adventurism. “I’m not as patriotic as most people,” he said, “and that’s the one thing that gets me in trouble with my cowboy friends.”

He was in such a funk after the war he quit music, roping and riding for a time. He rediscovered music first or as he prefers to think of it, music found him.

It all began with Heavin’s classical guitar epiphany. But the real journey commenced when Pastor heard Heavin play in college and the great man befriended the green American. The Spaniard was unlike anyone he’d met before.

“I was introduced to this little old man who couldn’t speak English. He was very kind but very formal, very upper-crust European society. There was a definite respect one had to acquire. I spent an entire afternoon playing for him. He was helping me, showing me some things, and then he’d play. I think he saw in me that I was wide-eyed and open and very grateful that he would spend this time with me.”

More than Heavin could dream came next.

“He played a concert that night and it was awesome. He dedicated a song to me,” Heavin said. “Before he left he said, ‘When I get to Spain I’m going to send you some music.’ About two weeks later I got a big stack of music I started working on. He came back the following year and this time he worked with me for 10 days in Springfield. All this music I’d worked on I played for him. I studied some more. And at the end of the 10 days he said, ‘If you come to Spain, I’ll teach you for nothing. You’ll be my only student,’ and I was.”

At the time though, Heavin said, “I didn’t know what this meant or how it was going to work out.” A university official aided Heavin’s overseas studies by finding grant monies for him. But Heavin still had no inkling his apprenticeship would turn out to be, “with the exception of my daughter’s birth,” he said, “one of the most wonderful experiences of my life.” Off to Madrid he went.

“When I arrived there was an apartment for me. The maestro’s wife was like my mom. His son was like my brother. And I realized shortly after I got there that I was his only student,” he said. “He rarely took them. There were Spanish boys waiting in line to study with him.”

Heavin immersed himself in all things Spanish. “I lived in the culture. I wasn’t with Americans at all. My friends were all Spanish. I taught them English, they taught me Spanish.” Ironically, the one thing this former bull rider didn’t care for was bullfighting, yet he lived a block from the Plaza de Toros, the bullfighting arena, and next door to the hospital for bullfighters. He’d watch the injured fighters come out “all bandaged up,” but felt even worse for the bulls.

Mostly his life revolved around the music.

Mostly his life revolved around the music.

“During the 10 months I was there I had a lesson from Segundo almost every day,” he said. “He put all of himself into that one student. That’s why he didn’t take on many. It was really like a fairy-tale…”

To this day Heavin’s unsure what Pastor saw in him to make such a commitment. “Maybe it was my sound,” he speculates. He feels it must have also had something to do with “the fact I loved Spain and I loved to play guitar and I loved that music.” Even when Heavin struggled to get the music right, “he never gave up on me.”

“The thing that’s odd about it is that I had only been playing about a year when the maestro invited me to Spain,” he said. “It was confusing because there were Spanish boys who could play better than I.”

It nagged at Heavin the whole time he was there.

“I kept asking him, ‘Why did you pick me?’ And he would never answer it. The last night I was there he knocked on my door and we went to the university in Madrid. It was one of those romantic Spanish evenings. We were walking down a wet, cobblestone street and he put his arm up on my shoulder and he squeezed it and said, ‘You keep asking me this question. True, the Spanish boys are good guitarists, but you’ll be a great guitarist.’ You see, I was too naive to know if I was any good or not. But he knew. It gave me everything I needed to go forward.”

Not only did Pastor give him a career, Heavin said, “he gave me back myself.”

Pastor’s high praise for his student — “A brilliant guitarist…he likes to make poetry out of music” — has been seconded by others.

After graduating from Southwest Missouri State Heavin received a fellowship from the University of Denver and after getting his master’s there he joined the UNO music department. Wherever Heavin lived, he continued to visit Pastor in Spain and to spend time with him in the states.

Segundo Pastor

In 1993 Pastor fell ill. Heavin flew to Madrid to be with him. When he got there he found the maestro confined to a wheelchair — weak and having not spoken for weeks. Heavin said when Pastor’s wife announced, “‘Look, maestro, Hadley’s here,’ his face just lit up. It was great. That night I slept on the other side of the wall from him. The next night I walked in his room, and as I was standing over him, looking at him, he awoke with a start. He rolled over on his back, pulled my face down to his chest and patted my head. He started talking. He said, ‘You know I love you. I hope some day you’re blessed like I have been with a woman. When my mind clears I’m going to write a great piece for you.” Those sentiments were the last words the maestro uttered. He died within a couple weeks.

Pastor’s gone now but Heavin keeps alive the tradition. He said the students who excel under him today are the ones who appreciate the gift Pastor gave him that he now passes onto them.

“It’s not just me they’re getting it from, they’re getting it from all of us in the line. The students that figure that out and treasure that are the ones that go off to other schools and blow everybody away,” he said.

One such student is 2002 UNO grad Mike Cioffero, an award-winning player and now a teacher at the prestigious New York City Guitar School.

“To have that direct connection is so important and wonderful,” Cioffero said. “Hadley definitely establishes that.”

Heavin’s “day job” is at UNO. He works one-on-one with students and ensembles and serves as a graduate lecturer. Some students have gone on to a good bit of success, like Cioffero. Teaching is something he loves. He’s not so fond of navigating academia’s politics and personalities. “I’ve stayed,” he said, “because of my students.”

In his 30s Heavin resumed roping and riding. “I started missing the horses, the competition and my cowboy friends,” he said. Without them, he was incomplete. As “the Good Lord saw fit to give me an extra shot of adrenalin,” he said, he needs both extremes in his life.

“Playing the guitar is a very disciplined, very quiet, very by-yourself, very sedentary thing. Mentally it isn’t, but physically it is. I couldn’t just sit on my ass and play guitar all the time — it’s too boring. When I was back from the war and just playing guitar, I was a little crazy, a little anti-social. For me, rodeo satisfied something in me that made it possible for me to play guitar. I think it helps me play a lot better.”

At first glance it appears as if he leads dual lives. Yet so intertwined are these pursuits with who he is, he can’t separate them. Each is an expression of himself.

“For me that’s my balance,” he said. “One balances out the other.”

Then there’s his hell-bent for leather nature. “I’ve learned to try anything,” he said, “but it wasn’t like I chose those things, it was like those things chose me. I was meant to do those things.”

He doesn’t just dally in one endeavor or the other. He’s trained by masters in each and performs at “a high level” whether in the concert hall or the horse arena.

His maestro, Pastor, toured the world as “Spain’s representative on guitar.” He had his own television show in his homeland. He was the subject of books. One book, printed only in Spanish, devotes a chapter to the Pastor-Heavin relationship.

Similarly, Heavin was schooled by roping-riding gurus D.K. Hewitt, Kent Martin and Jim Brinkman, “some of the best in these parts or anywhere,” according to Heavin.

Knowing the proper way of doing things is no small matter for a man whose art depends on his hands and yet who puts them at risk in a sport where injuries are common. Whereas, he said, “a lot of my friends are missing a thumb or fingers,” he’s never seriously hurt his digits. “I’ve skimmed up my little finger a few times heeling. Those coils are the dangerous things. It just cauterizes it when it burns through.” Every time he ropes he puts his music career in jeopardy.

“Lots of people tried to talk me out of roping,” he said. Pastor was not among them. He actually fancied his cowboy ways. “ He thought it was cool,” Heavin said.

Despite the hazards, Heavin’s confident in his training.

“If I was going to lose a finger it probably would have been the first year I was roping,” he said. “But for me the secret is being a good enough horseman. Like one time I was heading and the rope was wrapped around my wrist and I felt it coming tight against the horns. It would have broken my wrist pretty badly but I just kicked the horse up so I could get it (rope) undone, which saved me. Most guys when they get pain they stop their horse. Your horsemanship is the key… I’ve learned to do it correctly. There’s an art to it.”

He’s so adept he once qualified for the AQHA world horse show finals in Oklahoma City.

Plus, he’s never found anything like the thrill of running down a steer on horseback, swinging his rope high overhead, throwing it with a quick snap of his wrist and hitting his mark with a perfect figure-eight loop.

“The fact is I’ve tried everything. I mean, I’ve tried racquetball, golf, every sport, just so I wouldn’t take a chance on losing a finger, but nothing works for me,” he said. “When I’m running full-speed on a horse it’s exciting as hell. No matter how long you do it it’s always a rush.”

There’s a shared ebb-and-flow, give-and-take to his pursuits. “Music is like that, riding is like that, roping is like that,” he said. “It’s knowing when to be aggressive and when to back off.” In music, it’s as much knowing when the silence needs to be there between the notes as it is filling the silence. In the saddle, it’s letting a horse circle around or move forward or backward before getting him settled in the box for a run. For team roping, it’s the timing of the heeler working in tandem with the header to rope the bull.

“It’s figuring out when to do what,” he said.

There’s no where Heavin would rather be than home. At the end of a long day riding, roping, baling hay, caring for animals, he relaxes with his guitar. The instrument and the music he makes on it provide the counterbalance he craves.

“I pick up my guitar at night, when it’s quiet, and it calms me right down.”

Related Articles

- Spanish Fandango, classical/blues nexus (hermenaut.org)

- Could Chicago Guitar Festival in October 2010 Boost Local Scene? (thecontrapuntist.com)

- Guitar music that justifies the guitar. (ask.metafilter.com)

- Classical Guitar – Summer Listening List (kenekaplan.wordpress.com)

- Tarrega’s Gran Vals – The Nokia tune (merlinsnewrags.wordpress.com)

University of Nebraska at Omaha Wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

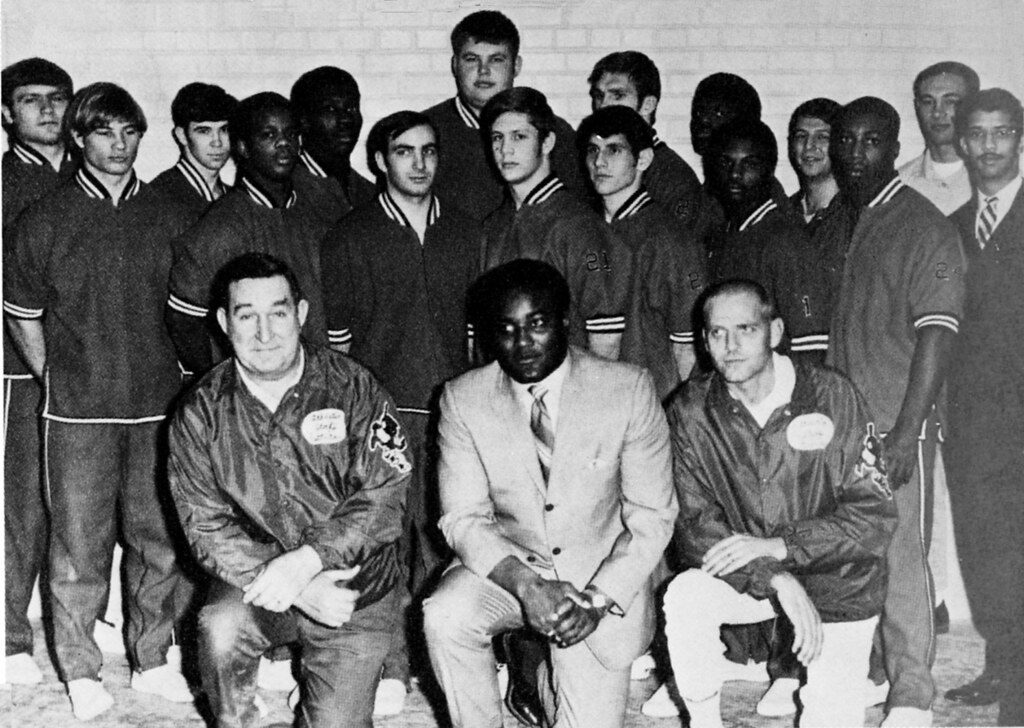

Don Benning, center front row, with his magnificent wrestling team

THE LATEST: Requiem for a Dynasty will be the headline, if I get an assignment to write the story that is, for what transpired as expected with the UNO wrestling program. As anticipated and despite the most heartfelt efforts of the program’s coaches, student-athletes, alums, and supporters the NU Board of Regents approved UNO’s proposed move to the Summit League and NCAA Division I competition and with it the elimination of the wrestling and football programs. It’s a sad day for UNO when its administrators can discard history and tradition so easily for the sake of convenience. In this disposable culture two programs were thrown out as if they were useless refuse. Losing football hurts, but the rationale for excising it ultimately makes sense because it was never going to come close to making money. Dumping wrestling though to purportedly be in better alignment with the Summit League is pure hogwash. It’s really UNO and NU leaders saying that they don’t give a rat’s ass about wrestling, that they don’t really care about all the championships, the scores of All-Americans, the prestige, the community service, the lessons learned, the incredibly strong and tight family bond built up across generations. They don’t care that UNO hosted multiple national championships and the largest single day annual wrestling tournament in the country. Why not give a damn about those things universities are there to provide its student-athletes and constituents? My take is that no matter how much UNO wrestling achieved, and it achieved so very much, it was never accorded the respect or due it deserved. Not by the regents, not by administrators, not by major university donors, not by the media, not by the general public. It was always considered marginal and therefore expendable. When things got tight, UNO wrestling was an easy target despite being a dynasty. That sends a disturbing, dysfunctional message to anyone really paying attention.

Getting rid of wrestling was painless for the regents because it was done in the abstract. By the time the UNO wrestling community appeared before them to plead their case that the program be retained, by the time all the appeals and messages had been made via email and phone, the regents had already made up their minds. The March 25 hearing was perfunctory. It was a show to merely let wrestling vent and have its say in an open forum. If the regents had bothered to actually visit the UNO wrestling room and to see first-hand the sweat and blood and tears and love and joy that went into making the dynasty, then the program might have had a fair day in court, so to speak. If the regents had seen for themselves the championship banners and the roll calls of All-Americans and soaked up the atmosphere of excellence imbued in that room, it might have been a different story. Or not. This was a business decision made by UNO and given the thumbs up by the regents. Cold, calculated business. The administrators and the regents simply didn’t get it or didn’t want to get it. They would not be moved by emotion or history. To the end, the UNO wrestling family fought gallantly, never breaking ranks, always showing class, the bonds that hold them together more powerful than any bureaucratic decree, extending beyond the now ended program. UNO wrestling may be gone, but its spirit lives on. The relationships between the men forged in that room and in those duals and tournaments and in all the time spent on the road and cutting weight and hanging out will endure.

NEW UPDATE: With each passing day any window of opportunity for UNO wrestling to be saved grows smaller. Unless something dramatic should happen between now and March 25th, it appears likely then that the NU Board of Regents will approve the plan advanced by University of Nebraska at Omaha Chancellor John Christensen and Athletic Director Trev Alberts for UNO to move to Division I and to drop football and wrestling in the process. As a graduate of UNO, as a former Athletic Department staffer, as a UNO sports fan, and as a writer I have a perspective to offer many don’t. Football certainly has a longer tradition than wrestling at the school, but when it comes to sustained success there’s no comparison. Don’t get me wrong, I will miss UNO football. I variously kept stats at and cheered at probably a hundred home games over the years. Caniglia Field is a great venue to watch a game at and UNO consistently plays at a high standard . UNO football’s been one of the best entertainment bargains in the city. But the sad truth is the program rarely drew well and even if IUNO football came along for the ride to D-I there’s little reason to expect it would draw any better at that level. UNO football has had its share of winning but it’s never won a national title and generally failed in the post-season, on the biggest of stages. UNO wrestling is a whole different story. It has been an elite program for more than 40 years. It’s won multiple national titles, produced scores of All-Americans, and basically been the best D-II program over the past 20 years. No, it’snot a big draw, although by wrestling standards it does quite well, but in terms of national prestige UNO is one of the best things the university has going for it, period. The crazy thing is that the UNO administration makes clear it’s not finances driving the proposed elimination of wrestling and football, which gets at the heart of it: UNO administrators don’t care about the excellence that UNO football and particularly UNO wrestling represents. It’s inconceivable it is prepared to walk away from something so successful, but that is what is about to happen.

Therefore, it seems like a good idea to look back at the wrestling program’s early years in order to gain an appreciation for where it came from and the significance it had at a tempestuous time in the university’s and in the city’s and in the nation’s history. The story of what Don Benning and his wrestlers did to put UNO on the map and to make UNO wrestling a champion is one of the great legacies of the university, and one it has never really embraced or celebrated to the extent it deserves. Sadly, wrestling at the school has always been viewed as marginal and expendable, and the words and actions of the UNO administration today bear that out. So check out the story below — it’s my take on the tide of social change that UNO’s glorious wrestling program is built on. I wrote it early last year for The Reader, as UNO prepared to defend its national title, which it did, and did again this year. It’s sad to think the story may now be the Requiem for a Dynasty.

UPDATE: Trev Alberts has been putting his stamp on the University of Nebraska at Omaha Athletic Department since his from left-field arrival in the job of athletic director two years ago. Chancellor John Christensen hand-picked Alberts to lead a revitalization of UNO athletics and Alberts has surprised many by just how bold his moves have been — from hiring Dean Blais as head hockey coach to getting major donors whose support had waned to ante up big again for capital improvements. And now as the Omaha World-Herald is reporting Alberts and Christensen are about to shake the foundation of the school and the athletic department by moving UNO into Division I competition across the board — pending University of Nebraska Board of Regents approval — by joining the Summit League. The news of going D-I isn’t that big a surprise in and of itself, as UNO has made clear for more than a decade that is where it wanted to go, but what is is UNO doing it so soon and its decision that in order to make it work long-term it must sacrifice the school’s two winningest sports — football and wrestling. Alberts and Christensen say they and others have worked the numbers and the only way UNO can justify the leap into the big-time is by dropping the heavy financial burden of football, whose weight would only increase with the increased scholarships and improved facilities D-I necessitates. Besides, where football is a revenue generator at many schools it is not at UNO and even the prospect of D-I would likely do little for the program’s mass appeal given the shadow of Big Red. But the real shocker is that UNO is prepared to jettison its shining star, wrestling, whose program just captured its eighth national title over the March 11-12 weekend. UNO could choose to go independent in wrestling but the school is opting not to do that, which is odd because it’s perhaps the least financially onerous men’s program in terms of scholarships, equipment, travel, facilities. But more to the point — how do you just dismiss the incredible success that UNO wrestling has achieved? I would hope that UNO finds a way to preserve the wrestling program. For a look at some of its remarkable history, see my story below about how the UNO wrestling dynasty is built on a tide of social change. You can also find on this blog my stories about Don Benning, the coach who began UNO’s wrestling dynasty, and about Trev Alberts, who may go down as the man who took down that same dynasty.

It may be a moot point in the end, but the UNO wrestling program is not going down without a fight. Coaches, student athletes, alums, fans, and boosters gathered at UNO Sunday, March 13 in the wake of the startling announcement that the wrestling program will be disbanded. Coach Mike Denney was seen calmly addressing the gathering and coalescing support. In an interview he gave a local TV sports reporter he pointed out that some schools in the Summit League that UNO has been invited to join do have wrestling programs. Denney asked the question a lot of people are asking: If they can be in that league and keep wrestling, then why can’t we do it? UNO Chancellor John Christensen and Athletic Director Trev Alberts apparently came to this decision without consulting Denney or the UNO wrestling community or UNO student leaders. The two men are undoubtedly acting out of good intentions and in the long term interests of the school but to spring this decision without warning and without giving Denney and his assistant coaches and student-athletes the opportunity to weigh in and argue against it is cruel and ill-advised. I would not be surprised if Don Benning adds his voice to the chorus of disapproval over Christensen’s and Albert’s decision to throw away the history and tradition that UNO wrestling represents.

________________________________________________________________________________

In my view, one of the most underreported stories coming out of Omaha the last 50 years was what Don Benning achieved as a young black man at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. At a time and in a place when blacks were denied opportunity, he was given a chance as an educator and a coach and he made the most of the situation. The following story, a version of which appeared in a March 2010 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com), charted his accomplishments on the 40th anniversary of making some history that has not gotten the attention it deserves.

One of the pleasures in doing this story was getting to know Don Benning, a man of high character who took me into his confidence. I shall always be grateful.

University of Nebraska at Omaha Wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

©by Leo Adam Biga

Version of story published in a March 2010 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

As the March 12-13 Division II national wrestling championships get underway at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, it’s good to remember wrestling, not hockey, is the school’s true marquee sport

Host UNO has been a dominant fixture on the D-II wrestling scene for decades. Its No. 1-ranked team is the defending national champs and is expected to finish on top again under Mike Denney, the coach for five of UNO’s six national wrestling titles. The first came 40 years ago amid currents of change.

Every dynasty has a beginning and a narrative. UNO’s is rooted in historic firsts that intersect racial-social-political happenings. The events helped give a school with little going for it much-needed cachet and established a tradition of excellence unbroken now since the mid-1960s.

It all began with then-Omaha University president Milo Bail hiring the school’s first African-American associate professor, Don Benning. The UNO grad had competed in football and wrestling for the OU Indians and was an assistant football coach there when Bail selected him to lead the fledgling wrestling program in 1963. The hire made Benning the first black head coach of a varsity sport (in the modern era) at a predominantly white college or university in America. It was a bold move for a nondescript, white-bread, then-municipal university in a racially divided city not known for progressive stances. It was especially audacious given that Benning was but 26 and had never held a head coaching position before.

Ebony Magazine celebrated the achievement in a March 1964 spread headlined, “Coach Cracks Color Barrier.” Benning had been on the job only a year. By 1970 he led UNO to its first wrestling national title. He developed a powerful program in part by recruiting top black wrestlers. None ever had a black coach before.

Omaha photographer Rudy Smith was a black activist at UNO then. He said what Benning and his wrestlers did “was an extension of the civil rights activity of the ’60s. Don’s team addressed inequality, racism, injustice on the college campus. He recruited people accustomed to challenges and obstacles. They were fearless. Their success was a source of pride because it proved blacks could achieve. It opened the door for other advancements at UNO by blacks. It was a monumental step and milestone in the history of UNO.”

Indeed, a few years after Benning’s arrival, UNO became the site of more black inroads. The first of these saw Marlin Briscoe star at quarterback there, which overturned the myth blacks could not master the cerebral position. Briscoe went on to be the first black starting QB in the NFL. Benning said he played a hand in persuading UNO football coach Al Caniglia to start Briscoe. Benning publicly supported efforts to create a black studies program at UNO at a time when black history and culture were marginalized. The campaign succeeded. UNO established one of the nation’s first departments of Black Studies. It continues today.

Once given his opportunity, Benning capitalized on it. From 1966 to 1971 his racially and ethnically diverse teams went 65-6-4 in duals, developing a reputation for taking on all comers and holding their own. Five of his wrestlers won a combined eight individual national championships. A dozen earned All-America status.

That championship season one of Benning’s two graduate assistant coaches was fellow African-American Curlee Alexander. The Omaha native was a four-time All-American and one-time national champ under Benning. He went on to be one of the winningest wrestling coaches in Nebraska prep history at Tech and North.

Benning’s best wrestlers were working-class kids like he and Alexander had been:

Wendell Hakanson, Omaha Home for Boys graduateRoy and

Mel Washington, black brothers from New York by way of cracker GeorgiaBruce “Mouse” Strauss, a “character” and mensch from back East

Paul and Tony Martinez, Latino south Omaha brothers who saw combat in Vietnam

Louie Rotella Jr., son of a prep wrestling legend and popular Italian bakery family

Gary Kipfmiller, a gentle giant who died young

Bernie Hospokda, Dennis Cozad, Rich Emsick, products of south Omaha’s Eastern European enclaves.

Jordan Smith and Landy Waller, prized black recruits from Iowa

Half the starters were recent high school grads and half nontraditional students in their 20s; some, married with kids. Everyone worked a job.

The team’s multicultural makeup was “pretty unique” then, said Benning. In most cases he said his wrestlers had “never had any meaningful relationships” with people of other races before and yet “they bonded tight as family.” He feels the way his diverse team came together in a time of racial tension deserves analysis. “It’s tough enough to develop to such a high skill level that you win a national championship with no other factors in the equation. But if you have in the equation prejudice and discrimination that you and the team have to face then that makes it even more difficult. But those things turned into a rallying point for the team. The kids came to understand they had more commonalities than differences. It was a social laboratory for life.”

“We were a mixed bag, and from the outside you would think we would have a lot of issues because of cultural differences, but we really didn’t,” said Hospodka, a Czech- American who never knew a black until UNO. “We were a real, real tight group. We had a lot of fun, we played hard, we teased each other. Probably some of it today would be considered inappropriate. But we were so close that we treated each other like brothers. We pushed buttons nobody else better push.”

“We didn’t have no problems. It was a big family,” said Mel Washington, who with his late brother Roy, a black Muslim who changed his name to Dhafir Muhammad, became the most decorated wrestlers in UNO history up to then. “You looked around the wrestling room and you had your Italian, your whites, your blacks, Chicanos, Jew, we all got together. If everybody would have looked at our wrestling team and seen this one big family the world would have been a better place.”

If there was one thing beyond wrestling they shared in common, said Hospodka, it was coming from hardscrabble backgrounds.

“Some of the kids came from situations where you had to be pretty tough to survive,” said Benning, who came up that way himself in a North O neighborhood where his was the only black family.

The Washington brothers were among 11 siblings in a sharecropping tribe that moved to Rochester, N.Y. The pair toughened themselves working the fields, doing odd-jobs and “street wrestling.”

Dhafir was the team’s acknowledged leader. Mel also a standout football lineman, wasn’t far behind. Benning said Dhafir’s teammates would “follow him to the end of the Earth.” “If he said we’re all running a mile, we all ran a mile,” said Hospodka.

Having a strong black man as coach meant the world to Mel and Dhafir. “Something I always wanted to do was wrestle for a black coach. It was about time for me to wrestle for my own race,” said Mel. The brothers had seen the Ebony profile on Benning, whom they regarded as “a living legend” before they ever got to UNO. Hospodka said Benning’s race was never an issue with him or other whites on the team.

Mel and Dhafir set the unrelenting pace in the tiny, cramped wrestling room that Benning sealed to create sauna-like conditions. Practicing in rubber suits disallowed today Hospodka said a thermostat once recorded the temperature inside at 110 degrees and climbing. Guys struggled for air. The intense workouts tested physical and mental toughness. Endurance. Nobody gave an inch. Tempers flared.

Gary Kipfmiller staked out a corner no one dared invade. Except for Benning, then a rock solid 205 pounds, who made the passive Kipfmiller, tipping the scales at 350-plus, a special project. “I rode him unmercifully,” said Benning. “He’d whine like a baby and I’d go, ‘Then do something about i!.” Benning said he sometimes feared that in a fit of anger Kipfmiller would drop all his weight on him and crush him.

Washington and Hospodka went at it with ferocity. Any bad blood was left in the room.

“As we were a team on the mat, off the mat we watched out for each other. Even though we were at each other’s throats on the wrestling mat, whatever happened on the outside, we were there. If somebody needed something, we were there,” said Paul Martinez, who grew up with his brother Tony, the team’s student trainer-manager, in the South O projects. The competition and camaraderie helped heal psychological wounds Paul carried from Vietnam, where he was an Army infantry platoon leader.

An emotional Martinez told Benning at a mini-reunion in January, “You were like a platoon leader for us — you guided us and protected us. Coming from a broken family, I not only looked at you as a coach but as a father.” Benning’s eyes moistened.

Joining them there were other integral members of UNO’s 1970 NAIA championship team, including Washington and Hospodka. The squad capped a perfect 14-0 dual season by winning the tough Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference tournament in Gunnison, Colo. and the nationals in Superior, Wis. It was the first national championship won by a scholarship team at the school and the first in any major sport by a Nebraska college or university.

Another milestone was that Benning became the first black coach to win an integrated national championship in wrestling and one of the first to do so in any sport at any level. He earned NAIA national coach of the year honors in 1969.

University of Washington scholar John C. Walter devotes a chapter to Benning’s historymaker legacy in a soon-to-be-published book, Better Than the Best. Walter said Benning’s “career and situation was a unique one” The mere fact Benning got the opportunity he did, said Walter, “was extraordinary,” not to mention that the mostly white student-athletes he taught and coached accepted him without incident. Somewhere else, he said, things might have been different.

“He was working in a state not known for civil rights, that’s for sure,” said Walter. “But Don was fortunate he was at a place that had a president who acted as a catalyst. It was a most unusual confluence. I think the reason why it happened is the president realized here’s a man with great abilities regardless of the color of his skin, and for me that is profound. UNO was willing to recognize and assist a young black man trying hard to distinguish himself and make a name for his university. That’s very important.”

Walter said it was the coach’s discipline and determination to achieve against all odds that prepared him to succeed.

Benning’s legacy can only be fully appreciated in the context of the time and place in which he and his student-athletes competed. For example, he was set to leave his hometown after being denied a teaching post with the Omaha Public Schools, part of endemic exclusionary practices here that restricted blacks from obtaining certain jobs and living in many neighborhoods. He only stayed when Bail chose him to break the color line, though they never talked about it in those terms.

“It always puzzled me why he did that knowing the climate at the university and in K-12 education and in the community pointed in a different direction. Segregation was a way of life here in Omaha. It took a tremendous amount of intestinal fortitude of doing what’s right, of being ready to step out on that limb when no other schools or institutions would touch African-Americans,” said Benning. He can only surmise Bail “thought that was the right thing to do and that I was the right person to do it.”

In assuming the burden of being the first, Benning took the flak that came with it.

“I flat out couldn’t fail because I would be failing my people. African-American history would show that had I failed it would have set things back. I was very aware of Jackie Robinson and what he endured. That was in my mind a lot. He had to take a lot and not say anything about it. It was no different for me. I had tremendous pressure on me because of being African-American. A lot of things I held to myself.”

Washington said though Benning hid what he had to contend with, some of it was blatant, such as snubs or slights on and off the mat. His white wrestlers recall many instances on the road when they or the team’s white trainer or equipment manager would be addressed as “coach” or be given the bill at a restaurant when it should have been obvious the well-dressed, no-nonsense Benning was in charge.

Hospodka said at restaurants “they just assumed the black guy couldn’t pay. They hesitated to serve us or they ignored us or they hoped we would go away.”

Washington could relate, saying, “I had a feeling what he was going through — the prejudice. They looked down on him. That’s why I put out even more for him because I wanted to see him on top. A lot of people would have said the heck with this, but he’s a man who stood there and took the heat and took it in stride.”

“He did it in a quiet way. He always thought his character and actions would speak for him. He went about his business in a dignified way,” said Hospodka.

UNO wrestlers didn’t escape ugliness. At the 1971 nationals in Boone, N.C., Washington was the object of a hate crime — an effigy hung in the stands. Its intended effect backfired. Said Washington, “That didn’t bother me. You know why? I was used to it. That just made me want to go out there more and really show ’em up.” He did, too.

“We were booed a lot when we were on the road,” Hospodka said. “Don always said that was the highest form of flattery. We thrived on it, it didn’t bother us, we never took it personal, we just went out and did our thing. You might say it (the booing) was because we were beating the snot out of them. I couldn’t help think having a black coach and four or five black wrestlers had something to do with it.”

Hospodka said wherever UNO went the team was a walking social statement. “When you went into a lot of small towns in the ’60s with four or five black wrestlers and a black coach you stuck out. It’s like, Why are these people together?” “There were some places that were awfully uncomfortable, like in the Carolinas,” said Benning. “You know there were places where they’d never seen an African-American.”

At least not a black authority figure with a group of white men answering to him.

The worst scene came at the Naval Academy, where the cold reception UNO got while holed up three days there was nothing compared to the boos, hisses, catcalls and pennies hurled at them during the dual. In a wild display of unsportsmanlike conduct Benning said thousands of Midshipmen left the stands to surround the mat for the crucial final match, which Kipfmiller won by decision to give UNO a tie.

The white wrestling infrastructure also went out of its way to make Benning and his team unwelcome.

“I think there were times when they seeded other wrestlers ahead of our wrestlers, one, because we were good and, two, because they didn’t look at it strictly from a wrestling standpoint, I think there was a little of the good old boy network there to try and make our road as tough as possible,” said Hospodka. “I think race played into that. It was a lot of subtle things. Maybe it wasn’t so subtle. Don probably saw it more because of the bureaucracy he had to deal with.”

“Some individuals weren’t too happy with me being an African-American,” said Benning. “I served on a selection committee that looked at different places to host the national tournament,. UNO hosted it in ’69, which was really very unusual, it broke a barrier, they’d never had a national championship where the host school had an African-American coach. That was pretty strange for them.”

He said the committee chairman exhibited outright disdain for him. Benning believes the ’71 championship site was awarded to Boone rather than Omaha, where the nationals were a big success, as a way to put him in his place. “The committee came up with Appalachian State, which just started wrestling. I swear to this day the only reason that happened was because of me and my team,” he said.

He and his wrestlers believe officials had it in for them. “There was one national tournament where there’s no question we just flat out got cheated,” said Benning. “It was criminal. I’m talking about the difference between winning the whole thing and second.” Refs’ judgements at the ’69 tourney in Omaha cost UNO vital points. “It was really hard to take,” said Benning. UNO had three individual champs to zero for Adams State, but came up short, 98-84. One or two disputed calls swung the balance.

Despite all the obstacles, Benning and his “kids” succeeded in putting UNO on the map. The small, white institution best known for its Bootstrapper program went from obscurity to prominence by making athletics the vehicle for social action. In a decade defined by what Benning termed “a social revolution,” the placid campus was the last place to expect a historic color line being broken.

The UNO program came of age with its dynamic black coach and mixed team when African-American unrest flared into riots across the country, including Omaha. A north side riot occurred that championship season. UNO’s black wrestlers, who could not find accommodations near the UNO campus, lived in the epicenter of the storm. Black Panthers were neighbors. Mel Washington, his brother Dhafir and other teammates watched North 24th St. burn. Though sympathetic to the outrage, they navigated a delicate line to steer clear of trouble but still prove their blackness.

A uniformed police cadet then, Washington said he was threatened once by the Panthers, who called him “a pig” and set off a cherry bomb outside the apartment he shared with his wife and daughter.

“I found those guys and said, ‘Anybody ever do that to my family again, and you or I won’t be living,’ and from then on I didn’t have no more problems. See, not only was I getting it from whites, but from blacks, too.”

Benning, too, found himself walking a tightrope of “too black or not black enough.” After black U.S. Olympians raised gloved fists in protest of the national anthem, UNO’s black wrestlers wanted to follow suit. Benning considered it, but balked. In ’69 Roy Washington converted to Islam. He told Benning his allegiance to Black Muslim leader Honorable Elijah Muhammad superseded any team allegiance. Benning released him from the squad. Roy’s brother Mel earlier rejected the separatist dogma the Black Muslims preached. Their differences caused no riff.

Dhafir (Roy) rejoined the team in December after agreeing to abide by the rules. He won the 150-pound title en route to UNO capturing the team title over Adams, 86-58. Hospodka said Dharfir still expressed his beliefs, but with “no animosity, just pride that black-is-beautiful. Dharfir’s finals opponent, James Tannehill, was a black man married to a white woman. Hospodka said it was all the reason Dharfir needed to tell Tannehill, “God told me to punish you.” He delivered good on his vow.

It was also an era when UNO carried the “West Dodge High” label. Its academic and athletic facilities left much to be desired. “The university didn’t have that many things to feel proud of,” said Benning. Wrestling’s success lifted a campus suffering an inferiority complex to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Wrestling was one area where UNO could best NU, whose NCAA wrestling program paled by comparison.

“Coach Benning and his wrestling teams elevated UNO right to the top, shoulder-to-shoulder with its big brother’s football team down the road,” said UNO grad Mary Jochim, part of a wrestling spirit club in 69-’70. “They gave everyone at the school a big boost of pride. The rafters would shake at those matches.”

“You’d have to say it was the coming-together of several factors that brought about a genuine excitement about wrestling at UNO in the late 1960s,” said former UNO Sports Information Director Gary Anderson. He was sports editor of the school paper, The Gateway, that championship season. “There were some outstanding athletes who were enthusiastic and colorful to watch, a very good coach, and UNO won a lot of matches. UNO had the market cornered. Creighton had no team and Nebraska’s team wasn’t as dominant as UNO. It created a perfect storm.”

Benning said, “It was more important we had the best wrestling team in the state than winning the national championship. Everybody took pride in being No. 1.” Anderson said small schools like UNO “could compete more evenly” then with big schools in non-revenue producing sports like wrestling, which weren’t fully funded. He said as UNO “wrestled and defeated ‘name’ schools it added luster to the team’s mystique.

NU was among the NCAA schools UNO beat during Benning’s tenure, along with Wyoming, Arizona, Wisconsin, Kansas and Cornell. UNO tied a strong Navy team at the Naval Academy in what Hospodka called “the most hostile environment I ever wrestled in.” UNO crowned the most champions at the Iowa Invitational, where if team points had been kept UNO would have outdistanced the big school field.

“We didn’t care who you were — if you were Division I or NAIA or NCAA, it just didn’t matter to us,” said Hospodka, who pinned his way to the 190-pound title in 1970. The confidence to go head-to-head with anybody was something Benning looked for in his wrestlers and constantly reinforced.

Said Hospodka,”Don always felt like we could compete against anybody. He knew he had talent in the room. He didn’t think we had to take a back seat to anybody when it came to our abilities. He had a confidence about him that was contagious.”

The sport’s bible, Amateur Wrestling News, proclaimed UNO one of the best teams in the nation, regardless of division. UNO’s five-years of dominance, resulting in one national championship, two runner-up finishes, a third-place finish and an eighth place showing, regularly made the front page of the Omaha World-Herald sports section.

The grapplers also wrestled with an aggression and a flair that made for crowd-pleasing action. Benning said his guys were “exceptional on their feet and exceptional pinners.” It wasn’t unusual for UNO to record four or five falls per dual. Washington said it was UNO’s version of “showtime.” He and his teammates competed against each other for the most stylish or quickest pin.

Hospodka said “the bitter disappointment” of the team title being snatched away in ’69 fueled UNO’s championship run the next season, when UNO won its 14 duals by an average score of 32-6. It works out to taking 8 of every 10 matches. UNO posted three shut outs and allowed single digits in seven other duals. No one scored more than 14 points on them all year. The team won every tournament it competed in.

Everything fell into place. “Nobody at our level came even close to competing with us,” said Hospodka. “The only close match we had was Athletes in Action, and those were all ex-Big 8 wrestlers training for the World Games or the Olympics. They were loaded and we still managed to pull out a victory (19-14).” At nationals, he said, “we never had a doubt. We had a very solid lineup the whole way, everybody was at the top of their game. We wrapped up the title before the finals even started.” Afterwards, Benning told the Gateway, “It was the greatest team effort I have ever been acquainted with and certainly the greatest I’ve ever seen.”

Muhammad won his third individual national title and Hospodka his only one. Five Mavs earned All-America status.

The foundation for it all, Hospodka said, was laid in a wrestling room a fraction the size of today’s UNO practice facility. “I’ve been in bigger living rooms,” he said. But it was the work the team put in there that made the difference. “It was a tough room, and if you could handle the room then matches were a breeze. The easy part of your week was when you got to wrestle somebody else. There were very few people I wrestled that I felt would survive our wrestling room.”

“It was great competition,” said Jordan Smith. “One thing I learned after my first practice was that I was no longer the toughest guy in the room. There were some recruits who came into that room and practiced with us for a few days and we never saw them again. I was part of something that really was special. It was a phenomenal feeling.”

This band of brothers is well represented in the Maverick Wrestling and UNO Halls of Fame. The championship team was inducted by UNO and by the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference. Benning, Mel Washington, Dhafir Muhammad and Curlee Alexander are in the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame. But when UNO went from NAIA to NCAA Division II in ’73 it seemed the athletic department didn’t value the past. Tony Martinez said he rescued the team’s numerous plaques and trophies from a campus dumpster. Years later he reluctantly returned them to the school, where some can be viewed in the Sapp Fieldhouse lobby.

UNO’s current Hall of Fame coach, Mike Denney, knows the program owes much to what Benning and his wrestlers did. The two go way back.

Benning left coaching in ’71 for an educational administration career with OPS. Mike Palmisano inherited the program for eight years, but it regressed.

When Denney took over in ’79 he said “my thing was to try to find a way to get back to the level Don had them at and carry on the tradition he built.” Denney plans having Benning back as grand marshall for the March of All-Americans at this weekend’s finals. “I have great respect for him.” Benning admires what Denney’s done with the program, which has risen to even greater heights. “He’s done an outstanding job”

As for the old coach, he feels the real testament to what he achieved is how close his diverse team remains. They don’t get together like they once did. When they do, the bonds forged in sweat and blood reduce them to tears. Their ranks are thinned due to death and relocation. They’re fathers and grandfathers now, yet they still have each other’s backs. Benning’s boys still follow his lead. Hospokda said he often asks himself, “What would Don want me to do?”

At a recent reunion Washington told Benning, “I’m telling you now in front of everyone — thank you for bringing the family together.”

Related Articles

- FBI tracked Alabama Crimson tide, Paul ‘Bear’ Bryant, documents show (sports.espn.go.com)

- University regents approve Nebraska-Omaha’s D-I move (sports.espn.go.com)

- Dean Blais Has UNO Hockey Dreaming Big (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)