Archive

John Beasley has it all going on with new TV series, feature film in development, plans for new theater and possible New York stage debut; Co-stars with Cedric the Entertainer and Niecy Nash in TVLand’s “The Soul Man”

Film-television-stage actor John Beasley is someone I’ve been writing about for the better part of a decade or more, and I expect I’ll be writing about him some more as time goes by. You may not know the name but you should definitely recognize his face and voice from films like Rudy and The Apostle and from dozens of episodic television guest star bits. His already high profile is about to be enhanced because of his recurring role in the new Cedric the Entertainer sit-com, The Soul Man, for TVLand. The show premieres June 20. The following story, soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com), has him talking about this project with the kind of enthusiasm that whets one’s appetite for the show. It’s one of several irons in the fire he has at an age – almost 70 – when many actors are slowing down. In addition to the series he has a feature film in development that he’s producing, a new theater he plans opening in North Omaha, and the possibility of making his New York stage debut in a new Athol Fugard play. On this blog you’ll find several stories I’ve written over the years about the actor and his current theater in Omaha, the John Beasley Theater & Workshop.

John Beasley has it all going on with new TV series, feature film in development, plans for new theater and possible New York stage debut

Co-stars with Cedric the Entertainer and Niecy Nash in TVLand’s “The Soul Man”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In his notable screen acting career John Beasley has done his share of television both as a one-off guest star (Detroit 1-8-7, Boston Legal, CSI: Miami, NCIS) and recurring player (Everwood, Treme).

But in the new TVLand series The Soul Man (formerly Have Faith) he has his biggest featured role to date, and in a comedy no less starring Cedric the Entertainer. The original show from the producers of Hot in Cleveland and Grimm premieres June 20 at 9 p.m.

“I’m third on the cast list and I’m getting a lot of work on the series, so I’m definitely happy about that,” Beasley says. “It’s a quality show. It’s very funny. The writing is really very good. We have the writers from Hot in Cleveland, one of the hottest shows on cable. Phoef Sutton is the show runner. He won two Emmys with Cheers. Plus, Cedric has got a really good sense of comedic timing. What he brings to the table is tremendous.

“And then Stan Lathan, the director, has worked on a lot of the great four-camera shows, as far back as the Red Foxx show Sanford and Son. A very good director.

“So we’re in very good hands.”

This native son, who’s continued making Omaha home as a busy film-TV character actor, has his career in high gear pushing 70. Besides the show there’s his long-in-development Marlin Briscoe feature film, plans for a North Omaha theater and the possibility of making his New York theater debut.

Beasley, who raised a family and worked at everything from gypsy cab driver to longshoreman, before pursuing acting, plays another in a long line of authority figures as retired minister Barton Ballentine. After years leading the flock at his St. Louis church he’s stepped aside for the return of his prodigal son, Rev. Boyce “The Voice” Ballentine (Cedric). Boyce is a former R&B star turned Las Vegas entertainer who, heeding the call to preach, has quit show biz to minister to his father’s church. He returns to the fold with his wife Lolli (Niecy Nash) and daughter Lyric (Jazz Raycole), who’ve reluctantly left the glitter for a humble lifestyle.

As Barton, Beasley’s an “old school” man of God who disapproved of his son’s former high life and racy lyrics and now holding Boyce’s inflated ego in check with fatherly prodding and criticism.

Speaking to The Reader by phone from L.A. where he’s in production on the series through mid-summer at Studio City, Beasley says Cedric’s character “can never live up to his father’s expectations – the father is always going to put him down no matter what he does, but he’s got a hustler brother who’s even worse.” Beasley adds, “In the pilot episode the parishioners are filing out after church, telling Boyce, ‘Great service, nice sermon,’ and then I come up to him and say, ‘I would have given it a C-minus. The bit near the end was decent but I would have approached it more from the Old Testament. But that’s just me. God’s way is the right way.’ That’s my character and that’s his relationship with his son.”

Praised by other actors for his ability to play the truth, Beasley says, “What I bring to the table is I kind of ground the show in reality. It allows the other actors to be able to go over the top a little bit, to play for the laughs. I don’t play for the laughs. I treat this character just like I would an August Wilson character. In fact one of the characters he’s patterned after is Old Joe from Gem of the Ocean.

“I was doing Gem of the Ocean at the theater (his John Beasley Theater in Omaha) when I got the call for this. Generally Tyrone (his son) and I will put my audition on tape and send it out to L.A. A lot of times it will take us five-six takes to get really what I want but with this character it was like one take and we both agreed that was it. We did another one for safety and sent it out, and the next day I got the call…”

A chemistry reading in L.A. sealed the deal.

For Beasley, who’s worked with Oprah Winfrey (Brewster Place), James Cromwell (Sum of All Fears), Kathy Bates (Harry’s Law) and Robert Duvall (The Apostle), working with Cedric marks another milestone.

“We play off each other so well. The chemistry between us is really good. I’m seeing it in the writing. I’m getting a lot of stuff written for me. Cedric has a lot to do with the show and he’ll say, ‘John’s character needs this,’ or ‘We should give him this,’ so he’s really very giving and a great person to work with. As is Niecy Nash.

“We’ve only got five members in the cast and it just feels like family. I don’t think theres a weak link.”

Season one guest stars include Anthony Anderson, Robert Forster, Kim Coles, Tamar and Trina Braxton, Phelo and Sherri Shepherd.

Beasley’s adjusted well to the four-camera, live audience, sit-com format.

“Having a good theater background has prepared me for this because the camera is almost like a proscenium -–you gotta play to the cameras, you’ve got to know where you’re camera is so that you can open up to it. But you also have the feedback from the audience. For instance, in the first episode we did I appeared and Cedric and I just stopped and looked at each other because of the situation and the audience went on and on, so we had to wait for the audience to finish. That kind of thing happens.

“Sometimes Cedric or somebody forgets their lines or he ad-libs and the audience is with you all the way. It’s a lot of fun. It’s really like doing stage and I’m having a great time with it.”

Beasley’s invigorated, too, by how the writers keep tweaking things.

“The writers continue to write right up until taping and if something doesn’t work then they huddle up and they come back with something else and by the time we finish with it it’s working.”

It’s his fondest desire Soul Man gets picked up for a second season but Beasley has something more pressing on his mind now and, ironically, the show may prove an obstacle. On March 23 at the University of North Carolina Beasley and Everwood star Treat Williams did a staged reading of famed South African playwright Athol Fugard‘s new drama, The Train Driver. Fugard was there and Beasley says the writer made it clear he wants them for the play’s August 14-Sept. 23 run at the Romulus Linney Courtyard Theatre, part of the fabled Signature Theatre, in New York.

Trouble is, Soul Man doesn’t wrap till July 29. “I told the play’s producers, ‘Listen, nobody can do this better than I can. I want to do this. And so whatever we can do to work it out let’s do that.’ That’s where we left it,” says Beasley.

Whether it happens or not, he’s convinced Soul Man is a career-changer.

“I really feel this is going to be a difference-maker just as The Apostle was because people aren’t used to seeing me do comedy, so it’ll give them a different look at me as a performer and that’s really all I can ask.”

“It’s been quite a journey” to come from Omaha and find the success he has and still be able to reside here. And the best may yet be ahead.

Related articles

- Cedric the Entertainer Stars In The New TV Land Sitcom ‘The Soul Man’ Premieres June 2012 (video) (harlemworldmag.com)

- Cedric The Entertainer Talks New Sitcom, “The Soul Man” With Super Snake (1015jamz.cbslocal.com)

- TV Land Summer Line-Up Includes Original Programming, Shirley MacLaine Special and Launch of ‘That ’70s Show’ (tvbythenumbers.zap2it.com)

- Niecy Nash sees the light (mnn.com)

Bill Cosby Speaks His Mind on Education

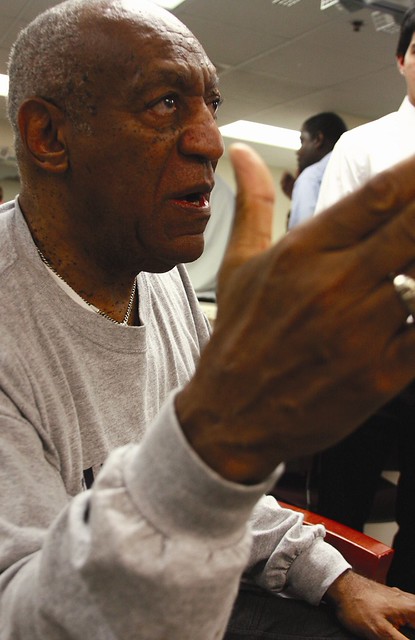

This is yet another story, the third by the way, that I wrote after my recent encounters with comedy legend Bill Cosby. Here, he tells it like he sees it about the state of education in America. Like many of us he has strong views on the topic and he isn’t afraid he will step on somebody’s toes from the weight of his celebrity when it comes to saying what he believes. Like what he says or not, he has a consistent message on the topic and has the courage of his convictions to keep right on talking even when there’s strong push-back from various quarters to some of what he states about schools, teachers, and parents. Most of the quotes from Cosby came out of phone interviews I did with him. The photos below came from a visit to his dressing room before his May 6 show in Omaha, where some visitors from Boys Town gave him another chance to sound-off on education and for me to record his comments and interaction with his guests. It was a privileged opportunity to glimpse an intimate, off-the-cuff Cosby speaking his heart and his mind on things he cares deeply about.

Bill Cosby Speaks His Mind on Education

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

By now America’s accustomed to King of Comedy Bill Cosby turning serious about topics he usually mines humor from. Expressing his celebrity opinions he sometimes touches a nerve, as when he asserted “parenting is not going on” in poor inner city black homes during a 2004 NAACP speech.

The Reader got three doses of Cosby opining before his May 6 Omaha concert. In each he revealed different facets of himself. In a phone interview he recalled in his avuncular storyteller way his slacker youth in Philadelphia public housing projects and schools. How it took “a rude awakening” for the high school drop-out to become motivated to learn. A “kickoff” moment convinced him “yes, you can do.”

His transformation began in the U.S. Navy, where he earned his GED. At Temple University a professor encouraged his talent as a comic writer, reading his work aloud in class to appreciative laughter.

“Had it not been for the positive influence of this professor, without him reading that out loud and my hearing the class laugh, who knows, I may be at this age a retired gym teacher, well loved by some of his students.”

Emboldened, Cosby left school short of graduating to pursue his stand-up career, certain, he says, “I was on track with what I wanted to do.” He famously returned to complete his bachelor’s degree and to earn his master’s and Ed.D in education.

He became “a born again, want-to-be-a-teacher.” No wonder then he’s made education a subject for his advocacy and critique. His strong views don’t make him an expert. He doesn’t claim to be one. And, to be fair, The Reader asked him to weigh-in on the topic for a second phone interview. He gladly did, too, only this time going off on a rail.

Two weeks later in his Orpheum Theater dressing room he addressed child rearing and education with a captive audience of fans, friends and media. When he gets on a roll like this he’s equal parts storyteller and lecturer, blustery one moment, nostalgic the next, probing and cajoling, his mischievous inner-child never far away.

To some, he’s a voice of old school wisdom and tough love. To others, an out-of-touch relic. No matter how you feel about his straight talk, it’s clear he’s concerned about education. His words carry weight because he’s fixed in the collective conscience as America’s father from The Cosby Show (1986-1994) and all the family routines he’s done in concerts, on albums, et cetera.

So when Cosby proclaims, as he did to The Reader, “In education, things are broken,” you listen. He believes the brokenness is systemic. “However,” he adds, “there are paradigms and they are not secrets. Paradigms meaning they work, they are accessible, you can look at them, and they don’t cost super extra money. Because it has been proven that to teach and to make interesting to the students all you need is a good teacher and all that teacher needs is a good principal and all that good principal needs is a good superintendent.”

“And they can work on a dirt floor, given students who every year come in perhaps disliking school, perhaps ill-mannered, and still get students to learn,” he says. “These people who can teach – and I don’t mean the ones who win awards, I mean teachers who can teach, who want to teach – are being held back on purpose by rules in the system. Many of these rules have to do with piling on what’s in the practicum, in the technical aspects of it, not giving the teacher enough time because there are sayings like, ‘If the student fails, then we fail.’

“In my eyes and ears there are too many people who don’t care and they need to go and the people who can work it need to teach…because this United States of America is being talked about in terms of not being what it used to be and that’s an embarrassment.”

Cosby was just getting started.

“Some people can’t teach and don’t know how, they don’t have an inventive bone in their body and they just need to get another job some place, and I won’t embarrass the people by saying what kind of jobs they should have.

“But if you care, if you care about these children and you want to be a teacher and you want to be a principal and you want to be an administrator, a superintendent, then I advise you go to college, get ready to demonstrate, get ready to call out every ill-positioned person…They can’t forever get away with this.

“I am appalled because I feel the grownups who are in charge really don’t understand how they’re ruining our future adults and they at times have not been taught well how to teach.”

Then he got around to youth not being supervised and supported at home. How many teachers are unprepared to deal with the issues kids present. Some of those same kids end up as truants, dropouts, functional illiterates, even criminals.

“Many times the teacher may represent the only reasonable thing in life this child will see or feel. Without an education we send more kids out to the street alone because many of them don’t have proper parenting at home. Education happens to be, along perhaps with the church and some programs, the difference between a kid committing a crime, hurting someone, and getting the idea that I would like to read, I would like to write, I would like to know how to figure things out, I would like to see more than just the neighborhood I live in.”

A failed education, he says, can be measured in lowered earnings, welfare payouts and the costs to incarcerate criminal offenders.

“It would seem to me taxpayers would be in arms to say, ‘We want better education, we demand better education for our children'” to help youth become productive, contributing citizens.

He admits he doesn’t have “remedies.” He does call for “activism” by parents, educators, private enterprise and public policymakers to give schools the resources they need and replicate what works.

Cut to his dressing room, where Boys Town family teachers Tony and Simone Jones brought nine youths in their charge, including their two sons. “You live with them?” asked Cosby. “Why? You were not drafted to look after these boys. OK, then tell me, why are you living there with them?”

“Because we feel it’s our responsibility to take care of the kids, not only our own youth but youth in society,” Simone said.

“But what made that a responsibility for you? They’re not your children,” he pressed.

Tony said, “Mr. Cosby I’ll answer just very simply: My mom passed when I was 12 years old, and I went to Boys Town to live…” Cosby erupted with, “Oh, really! Now you’re starting to tell me stories, you see what I’m talking about (to the boys), you guys understand me? Huh?” Several boys nodded yes. “The story is coming, huh? What did Boys Town do for him?” Cosby asked. One boy said, “Helped him out, gave him a place to stay.” Another said, “Gave him a second chance.”

“Well, more than a second chance,” Cosby replied. “it took care of him,” a boy offered. “And made him take care of himself…and that’s why he’s living with you now – he’s trying to build you.”

Noting “the hard knock life” these kids come from, he said youth today confront different challenges than what he faced as a kid.

“When I was coming up we didn’t have Omaha, Neb. ranked high in teenage boys murdering each other. Am I making sense? We didn’t have the guns being placed in our neighborhoods. We had guys who made guns…but now we have real guns and good ones too. It’s in the home.”

Where there are caring adults and good opportunities kids make good choices.

“The idea is where are these boys coming from and what places they may have to get to. We’ve got to do more with fellows like these for them to do shadowing…in hospitals, in factories, in businesses, so that these young males begin to understand what they can do.”

Cosby told Tony and Simone he can see “the joy of these boys knowing that you guys care.”

“It’s about showing them the possibilities,” Simone told him.

Cosby knows all about the difference a teacher’s encouragement can make.

Before seeing his guests out, Tony and Simone got a private moment with Cosby. She says, “He pulled us aside and told us, ‘You really need to push children hard to get them to do what they should do. You can’t let them slide. Sometimes you have to make a choice for them.’ We appreciated his words of advice and wisdom.”

Meeting the legend, she says, “was a remarkable experience,” adding, “He was really concerned with our kids and what we do. I know every kid that was there took away something that’s magical that they’ll hold with them for the rest of their lives.”

Related articles

- Bill Cosby, On His Own Terms (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Bill Cosby Coming to Omaha to Perform Comedy Concert May 6 (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Outward Bound Omaha Uses Experiential Education to Challenge and Inspire Youth (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Evangelina “Gigi” Brignoni Immerses Herself in Community Affairs (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Bill Cosby on his own terms: Backstage with the comedy legend and old friend Bob Boozer

UPDATE: It is with a heavy heart I report that hoops legend Bob Boozer, whose friendship with Bill Cosby is glimpsed in this story, passed away May 19. Photographer Marlon Wright and I were in Cosby’s dressing room when Boozer appeared with a pie in hand for the comedian. As my story explains, the two went way back, as did the tradition of Boozer bringing his friend the pie. This blog also contains a profile I did of Boozer some years ago as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. For younger readers who may not know the Boozer name, he was one of the best college players ever and a very good pro. He had the distinction of playing in the NCAA Tournament, being a gold medal Olympian, and winning an NBA title.

My Bill Cosby odyssey continued in unexpected ways the first weekend in May.

After interviewing him by phone for two-plus hours in advance of his Sunday, May 6 show, I secured a face to face interview with him in his dressing room. Photographer Marlon Wright accompanied me. Only moments before our meeting, however, it appeared there would be no face time with the legend. Word of our backstage interview somehow hadn’t reached Cosby and as we walked into his Orpheum Theater dressing room he was unsuccessfuly trying to confirm things with his PR handler. That’s when I assured him I was the same reporter who had talked to him by phone at length. When he gave me a look that said, “Do you know how many reporters I talk to?” I blurted out, “I’m the remedial man,” referring to our shared past of testing into remedial English in college, something that became a recurring joke between us during that marathan phone interview. “Why didn’t you say so?” he said, and just like that we were in.

After 15 minutes or so I was prepared to thank him for his time when an assistant came back to announce that Cosby’s old Omaha friend, Bob Boozer, who was a college All-American. Olympic gold medalist and NBA titlist, was outside. Cosby’s face lit up. Marlon and I exchanged a quick look that said, ‘Let’s stick around,” and so we did. What played out next was an intimate look at how a King of Comedy holds court before going on. Boozer brought a sweet potato pie his wife Ella baked.

Cosby was obviously touched and kidded his friend with, “I appreciate you not getting into it.” These two former athletes traded good-natured jibes about each others’ ailments and at one point Cosby placed his hands on Boozer’s knees and intoned, like a faith healer, “Heal.”

Then the assistant popped in again with memorabilia fans had brought for Cosby to sign, which he did, and not long after that a contingent from Boys Town was ushered in to meet The Cos. Family teachers Tony and Simone Jones, along with their son and nine young men who live with them, plus some BT staffers, all filed in and Cosby greeted each individually. What played out right up until his curtain call was a scene in which Cosby peppered the adults and kids with probing questions, sometimes kidding with them, sometimes dead serious with them. It turned into a mini lecture or seminar of sorts and a very cool opportunity for these young people, who might as well have been The Cosby Kids from Fat Albert or from his family sit-coms.

By the time we all said goodbye our expected 15 minutes with Cosby had turned into 45 minutes and we’d gotten a neat glimpse into how relaxed and down to earth the entertainer is and just how well and warmly he interacts with people. I stayed for the show of course and it was more of the same, only a more animated Cosby was revealed.

©photo by Marlon Wright, mawphotography.net

©photo by Marlon Wright, mawphotography.net

Bill Cosby on his own terms: Backstage with the comedy legend and old friend Bob Boozer

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to appear in the New Horizons

Holding court in his Orpheum Theater dressing room before his May 6 Omaha show, comedy legend Bill Cosby was thoroughly, authentically, well, Bill Cosby.

The living legend exuded the easy banter, sharp observations and occasional bluster that defines his comedic brand. He was variously lovable curmudgeon, cantankerous sage and mischievous child.

He appeared tired, having played Peoria just the night before, but his energy soared the more the room filled up.

With his concert start nearing and him blissfully unaware of the time, he played host to this reporter, photographer Marlon Writght, old chum Bob Boozer and the family teachers and youth residents of a Boys Town family home.

By turns Cosby was entertainer, lecturer, father-figure and cut-up as he shook hands, autographed items and told stories.

He’s made the world laugh for 50 years now as a standup comedian, though these days he performs sitting down. He said colleagues of his, including jazz musician Eubie Blake, have accused him of not having an act. Cosby simply tells stories, with occasional clips from his TV shows projected on an overhead screen.

“Eubie wasn’t angry when he said it, he was just jealous. He’s from the days of vaudeville where guys had set ups and then the punchline,” said Cosby. “I think he was looking for the set up and the punchline and all I was doing was the same thing when he’s at my house.”

By that Cosby means talking. He talks about everything and nothing at all. His genius is that he makes none of it seem designed, though his stories are based on written material he writes himself. What makes his riffs seem extemporaneous is his impromptu, conversational delivery, complete with pauses, asides and digressions, just like in real life. Then there are the hilarious faces, voices and sounds he makes to animate his stories. What sets him apart from just anyone talking, he said, “is the performance in the storytelling.”

His enduring appeal is his persona as friend or neighbor, and these days uncle or grandfather, regaling us with tales of familiar foibles. He invites us to laugh at ourselves through the prism of true-to-life missteps and adventures in growing up, courting, parenting and endless other touchstone experiences. Making light of the universal human condition makes his humor accessible to audiences of any age or background.

“That’s the whole idea of the writing – everybody identifying with it,” he said.

That’s been his approach ever since he began taking writing seriously as a student at Temple University in his native Philadelphia. He found his voice as a humanist observer while penning creative writing compositions for class.

“I was writing about the human experience. Who told me to do it? Nobody. I just wrote it. Was I trying to be funny? No. Was I reading any authors who inspired me? No.”

It’s not exactly true he didn’t have influences. His mother read Mark Twain to him and his younger brothers when he was young. Just as she could spin a yarn or two, he was himself a born storyteller amusing friends and teachers. He also admired such television comics as Sid Caesar and Jack Benny, among many others, he drew on to shape his comic alter ego.

He may never have done anything with his gifts if not for a series of events that turned his life around. The high school drop out earned his GED, went to college, then left early to embark on his career, but famously returned to not only finish his bachelor’s degree but to go on and earn a master’s and a Ed.D in education.

He’s sreceived numerous honorary degrees and awards, including the Kennedy Center Honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and The Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. There have been dark days too. His only son Ennis was murdered in 1997. The comic’s alleged infidelity made headlines.

Through it all, he’s made education his cause, both as advocate and critic. His unsparing views on education and parenting have drawn strong criticism from some but he hasn’t let the push back silence him.

He said growing up in a Philadelphia public housing project he was a bright but indifferent student, devoting more time to sports and hanging out than studying. He recalls only two teachers showing real interest in him.

“I wasn’t truant, I just didn’t care about doing anything. I was just there, man. I was still in the 11th grade at age 19.”

He describes what happened next as “divine intervention.” The high school drop-out joined the U.S. Navy., Cosby hated it at first. “That was a very rude epiphany.” He stuck it out though, working as a medical aide aboard several ships, and obtained his high school equivalency. “I spent four years revamping myself.”

He marveled a GED could get him into college. Despite awful test scores Temple University accepted him on an athletic scholarship in 1960.

“I was the happiest 23-year-old in the world. They put me in remedial everything and I knew I deserved it and I knew I was ready to work for it. I knew what I wanted to be and do. I wanted to become a school teacher. I wanted to jump those 7th and 8th grade boys who had this same idea I had of just sitting there in class.

“Being in remedial English, with the goal set, that’s the thing that began to make who I am now.”

Fully engaged in schoolwork for the first time, he threw himself into creative writing assignments. He wrote about pulling his own tooth as a kid and the elusive perfect point in sharpening a pencil.

The day dreaming that once hampered his studies became his ticket to fame. He said the idea for one of his popular early bits, “The Toss of the Coin,” came during Dr. Barnett’s American History class at Temple.

“I began to drift as he was talking about the Revolutionary War.”

Cosby imagined war as a sporting contest with referees, complete with captains from each team – the ragtag settlers and the professional British army. A coin toss decided sides. In the bit the referee instructs the settlers, “You will wear fur hats and blend into the forest and hide behind rocks and trees.” To the Red Coats, the referee says, “You will wear red and march in a straight line and play drums.”

The day dreams that used to land him in trouble were getting him noticed in the rights way. He recalls the impact it made when the professor held up his papers as shining examples and read them aloud in class to appreciative laughter.

“That was the kickoff. That’s when my mind started to go into another area of, Yes you can do, and I began to think, Gee whiz, I could write for comedians. And all my life from age 23 on, I was born again…in terms of what education and the value is. To study, to do something and be proud of it – an assignment.”

He’s well aware his life could have been quite different.

“Had it not been for the positive influence of this professor, without him reading that out loud and my hearing the class laugh, who knows, I may be at this age a retired gym teacher, well loved by some of his students.”

While a Temple student he worked at a coffee house and he first performed his humorous stories there. Then he began filling in for the house comic at a Philly club and warming-up the audience of a local live radio show.

Those early gigs helped him arrive at his signature style.

“When I was looking for that style I saw it a Chinese restaurant. It was a party of eight white people and there was a fellow talking and everybody was just laughing. Women were folding napkins up to cover their faces. This was not a professional performer. Upon analyzing it I noted three things. First of all, he’s a friend of the other seven. Secondly, he’s talking about something they all know that happened. Thirdly, it happened to him and they are enjoying listening to his experience from his viewpoint

“And so I decided that’s who I want to be, that’s the style, because my storytelling is the same thing, whether I’m talking about pulling my own tooth or sharpening a pencil until it’s nothing but metal and rubber.”

Or the vicissitudes of being a father or son.

Not everyone recognized Cosby’s talents.

“I showed this comedian working in a nightclub a thing I wrote about Clark Kent changing clothes in a phone booth. In the bit a cop shows up and says, ‘What are you doings?’ and Kent says, ‘I”m changing clothes into Superman,’ and the cop says, Look, come out of there.’ ‘No, I’m Superman, can’t you see this red S on my chest?’ And the cop says, ‘You’re going to have a red S and a black eye.’ The comic read it and said, ‘This is not funny’ Within a couple years it was on my first album.”

Cosby ventured to New York City and followed the stand-up circuit. Then came his big break on The Tonight Show. Sold out gigs and Grammy-winning recordings followed.

Along with Dick Gregory, Nipsey Russell and Godfrey Cambridge, Cosby was among a select group of black comics who crossed over to give white audiences permission to laugh at themselves. None enjoyed the breakout success of Cosby. Without his opening the doors, Flip Wilson, Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy would have found it more difficult to enjoy their mainstream acceptance.

“I would imagine it was something brand new for an awful lot of people – to see this black person talking and making a connection and laughing because, Yeah, that happened to me.”

The iconic comic’s raconteur style has translated to best selling albums and books, where he mines his favorite themes of family, fatherhood and children. His warm, witty approach has made him a television and film star.

In his dressing room he appeared fit and comfortable in the same simple, informal attire he wore on stage: gray sweatshirt with the words Thank You printed on it and gray sweatpants with a draw string. The only thing missing from his stage outfit was his flip-flops. He spoke to us in his socks.

Totally in his element, with light bulb-studded mirrors, a soft leather sofa and bottles of Perrier water within easy reach, he captivated the audience of two dozen inside the dressing room just as expertly as he did the 1,500 souls in the auditorium.

For a few minutes photographer Marlon Wright and I had The Cos all to ourselves.

Two weeks earlier I conducted a long phone interview with the comic in which he discussed the “born again” experience that led to his path as a writer-performer. We hit it off and I struck a real chord when I shared that, like him, I tested into remedial English as a college freshman.

“Hey, man, we’re remedial,” became our running private joke.

He agreed to a photo shoot. Only when Marlon and I arrived at the Orpheum his aide informed us the appointment wasn’t booked on “Mr. Cosby’s” schedule. Escorted to his dressing room, I found Cosby trying to reach his publicist to confirm things. I reminded him of our phone interview from a couple weeks back and he shot me an exasperated look that said, Do you know how many reporters I talk to?

Determined not to blow this opportunity, I blurted out, “I’m the remedial man.” “Oh, why didn’t you say so?” he said, smiling broadly and inviting me to sit down. Just then, the phone rang. It was the PR person he’d tried earlier. “Yes, yes, I got him here.” he told her. “He finally said the key word, remedial, so I let him in.”

In the weeks preceding his concert Cosby did a local media blitz to try and boost lagging ticket sales. Sitting across from him in his dressing room, less than an hour before his performance, he expressed disappointment at the low number of tickets sold but pragmatically attributed it to the show’s 2 p.m. Sunday slot.

Asked what it is that still drives him to continue performing at age 74 and he answered, “I am still in the business. I’m still thinking, I’m still writing, I’m still performing extraordinarily well, and in a master sense.” It echoed something he said by phone about going on stage with a plan but being crafty enough to go where his instincts take him.

“Once I pass that threshold from those curtains to come out and sit down I know what I would like to do but I keep it wide open. I don’t know which way it’s going to shift, and a part of it has to do with the audience and the other part has to do with me – where am I at that time and what’s the brain connecting with in terms of being excited about something.

“I did a show in Tyler, Texas and I started out with enthusiasm talking about something and then I didn’t like what I was doing and I shifted the material to nontrends to trends until finally they began to click in. In other words, some audiences are and are not, and you have to go out there and find that, find what keeps and what works. It’s 50 years now. I know exactly where to mine and what to do.”

He knows he’ll eventually hit the sweet spots. As an American Instiution he has the luxury too of having audiences in the palm of his hand.

“Now, we already have a relationship that’s wonderful because people already know I’m funny, so there’s no guessing there, but on a given day, they are or they aren’t. Are they trusting you? Do I feel that way? It’s very complex but because I’m a master at it I think you want me in that driver’s seat to turn you on.”

It takes confidence, even courage to go out on that stage.

“Yes sir, and you need that, no matter what, I don’t care if you’re a driving instructor or what. If your confidence goes bad in comedy…” he said, his voice trailing off at the thought. “Whether you’re writing or getting ready to perform or sitting with friends and talking you have to have that confidence.”

He can’t conceive of slowing down when he still has the physical energy and mental edge to perform in peak fashion. Besides, he pointed out he’s not alone pursuing the comic craft at his age. Don Rickles, Bob Newhart, Mort Sahl. Bill Dana, Dick Gregory, Dick Cavett and Joan Rivers are older yet and still performing at the top of their game.

He said he fully intends returning to Omaha and selling out next time.

“So there I am talking about coming back – see?”

Besides, comics never retire unless their mind goes or body fails. The way he looks, Cosby might be at this for decades more.

Asked if he has any favorite routines or rituals backstage, he said aside from resting and signing memorabilia, he generally does what’s made him famous – talk. He bends the ears and tickles the funny bones of theater staffers, promoters, personal assistants, friends, acquaintances, fans.

Then, as if on cue, his aide Daniel popped in to say Bob Boozer was outside. Cosby immediately lit up, saying, “Ahhhh, all right, bring Bobby in and tell him he cannot come in without my you know what.” Boozer, the hoops legend, lumbered in bearing a sweet potato pie his wife Ella baked.

“Here’s Ella’s contribution to 2012 Cosby,” Boozer said handing the prized dessert to Cosby, who accepted it with a covetous grin that would do Fat Albert proud.

“I appreciate that you didn’t get in it,” Cosby teased Boozer, who for decades has made a tradition of bringing the entertainer Ella’s home-made sweet potato pie whenever he performs here.

Boozer confided later, “He loves it. I never will forget one time at Ak-Sar-Ben he had the pie on-stage with him and somebody in the crowd asked if they could get a slice, and he he draped his arms over it and said, ‘Heavens no, this pie is going back on the plane with me…'”

The two men go way back, to when Boozer played for the Los Angeles Lakers and Cosby was shooting I Spy. A teammate of Boozer’s, Walt Hazzard, was a Philly native like Cosby and Hazzard introduced Cos to Boozer and they hit it off.

A coterie of black athletes and entertainers would gather at Cosby’s west coast pad for marathon rounds of the card game Bid Whist and free-flowing discussions.

“We usually would have a hilarious time,” Boozer recalled.

When the Lakers were on the road and Cosby was performing in the same town Boozer said he, Hazzard and Co. “would always show up at his performances and visit with him about old times and that kind of thing.”

Together again at the Orpheum the pair reminisced. They share much in common as black men of the same age who helped integrate different spheres of American culture. They were both athletes, though at vastly different levels. Cosby was a fair track and field competitor in high school, the U.S. Navy and at Temple University. Boozer was an all-state basketball player at Omaha Tech High, an All-American at Kansas State, a member of the 1960 gold medal-winning U.S, Olympic team and the 6th man for the 1971 NBA champion Milwaukee Bucks.

When Boozer entered the then-fledgling National Basketball Association in 1960 blacks were still a rarity in the league. When he retired in ’71 he became one of the first black corporate executives in his hometown of Omaha at Northwestern Bell.

Cosby’s such a staple today that it’s easy to forget he helped usher in a soft revolution. At the same time his good friend Sidney Poitier was opening doors for African-Americans on the big screen, Cosby did the same on the small screen. He became the first black leading man on network TV when he teamed with Robert Culp in the groundbreaking episodic series, I Spy (1965-1968).

Cosby broke more ground with his TV specials, talk-variety show appearances and his innovative educational children’s program, The Electric Company (1971-1973). He was the first black man to headline his own series, The Cosby Show (1969-1971). But it was his second sit-com, also called The Cosby Show (1984-1992), that became a national sensation for its popular, positive portrayals of black family life. The series made Cosby a fortune and a beloved national figure.

The two men have know each other through ups and downs. So when these two old war horses reunite there’s an unspoken rapport that transcends time.

Like any ex-athletes of a certain age they live with aches and pains. At one point Cosby placed his hands on Boozer’s knees and intoned, “Heal, heal.” Later, I asked Boozer if it did any good, and he said, “No, I wish it would though.”

Pie wasn’t the only thing Boozer brought that day. The Nebraska Board of Parole member volunteers with youth at Boys Town. A family home there he’s become particularly “attached to” is headed by family teachers Tony and Simone Jones, who at Boozer’s invitation arrived with the nine boys that live with them. Cosby went down the half-circle line of boys one by one to meet them – clasping hands, getting their names, asking questions, horsing around.

Cosby with words of wisdom for Carvel Jones

Cosby with words of wisdom for Carvel Jones

Boozer and Cosby listening to Boys Town guests, ©photos by Marlon Wright, mawphotography.net

Boozer and Cosby listening to Boys Town guests, ©photos by Marlon Wright, mawphotography.net

When told that Tony and Simone are in charge of them all Cosby saw a teachable moment and asked, “You live with them? Why? You were not drafted to look after these boys. OK, then tell me, why are you living there with them?”

“Because we feel it’s our responsibility to take care of the kids, not only our own youth but youth in society,” said Simone.

“But what made that a responsibility for you? They’re not your children,” probed Cosby.

Tony next gave it a try, saying, “Mr. Cosby I’ll answer just very simply: My mom passed when I was 12 years old, and I went to Boys Town to live…” Cosby erupted with, “Oh, really! Now you’re starting to tell me stories, you see what I’m talking about (to the boys), you guys understand me? Huh?” Several of the boys nodded yes. “The story is coming, huh? What did Boys Town do for him?” Cosby asked them. One boy said, “Helped him out, gave him a place to stay.” Another said, “Gave him a second chance.”

“Well, more than a second chance,” Cosby replied. “it took care of him,” a boy offered. “And made him take care of himself, because you can see he’s eating well,” Cosby teased the stout Jones. “And that’s why he’s living with you now – he’s trying to build you,” Cosby told the kids.

The conversation then turned to what Cosby called “the hard knock life” these kids come from. He noted that youth today confront different challenges than what he or Boozer faced growing up and that Boys Town provides healthy mediation.

“We lived with our biological parents. Now my father drank too much and said he didn’t want any responsibility, which left the whole job on my mother, so we lived in a housing project. Yet we didn’t have the pressures these guys have, the insanity that exists today, and by insanity I mean not normal. Yes, there is a normal. What is normal? Normal is, ‘Don’t do that’ – ‘OK.’ Abnormal is, ‘Don’t do that.’ ‘No, I’m going to do it because you said don’t do it.’

“When I was coming up we didn’t have Omaha, Neb. ranked high in teenage boys murdering each other. Am I making sense? We didn’t have the guns being placed in our neighborhoods. We had guys who made guns but you had better than a 70-30 chance that gun would blow up in his hands. But now we have real guns and good ones too. It’s in the home.”

Cosby said it comes down to caring and making good choices.

“The first black to score a point in the NBA, Earl Lloyd, wrote a book and he tells the story of being 14-15 years old and he comes home and his mother says, ‘Where’ve you been?’ He’s stammering, he knows he’s caught with something, avoiding telling her he’s been in a place she doesn’t want him. She says, ‘You were with those boys on that corner.’ and he says, ‘But Mama, I wasn’t doing anything.’ And his mother says, ‘If you’re not in the picture, you cant be framed,’ and if you don’t understand what I just said someone will explain it to you.

“But the idea is where are these boys coming from and what places they may have to get to. There’s a place called Girard College in my hometown. You need to look it up. Forty-three acres. I call it the 10th Wonder of the World.”

The college, where Cosby gave the commencement speech last year, has a largely African-American student enrollment and graduates a high percentage of its students, most of whom come from at-risk circumstances. He said it’s a shining example of what can be.

“What’s missing in this society for black people and people of color is to own something, a small business to build upon. Many of you because of your color you will get the feeling, Yeah I can study and I can be but once I step away from college and go outside of that there are too many people that look at my color and listen to my language and they wont really welcome me. And all of you here know exactly what that feels like.”

Then, turning to Tony and Simone and referring to the boys, he said, “We’ve got to do more with fellows like these for them to do shadowing, to find business people willing to allow the boys to not go get coffee or to tie their shoes but to shadow, and it can happen in hospitals, it can happen in factories, businesses, so that these young males begin to understand what they can do.”

Cosby clearly admires the difference that adults like Tony and Simone make, saying he can see “the joy of these boys knowing that you guys care.”

“It’s about showing them the possibilities,” said Simone.

And with that, the legend bid his guests goodbye. As the entourage filed out with smiles, handshakes and break-a-leg well wishes this reporter was reminded of what Cosby said about the possibilities he began to see for himself once his college English professor took notice.

“I knew I was on track with what I wanted to do.”

Things have come full circle now and Cosby embraces the each-one-to-teach-one position of inspiring young people to live their dreams, to realize their potential.

“Hey, hey, hey…”

Related articles

- Bill Cosby Coming to Omaha to Perform Comedy Concert May 6 (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Fat Albert And The Cosby Kids: The Complete Series (werd.com)

- Bill Cosby: “We’ve Got To Get The Gun Out Of The Hands… (alan.com)

- Did Bill Cosby change how America views African American families? (tammymv.wordpress.com)

- Bill Cosby Visits Drexel’s Family Health Services Center Ahead Of Expansion (philadelphia.cbslocal.com)

- Bill Cosby Speaks His Mind on Education (wordpressreport.wordpress.com)

Dena Krupinsky makes Hollywood dreams reality as Turner Classic Movies producer

Whether you’re a regular or occasional visitor to this blog you have by now probably noticed that I like to write about Nebraskans in Film. That is a function of my being a Nebraskan, a film buff who just happens to be a journalist. Naturally, I seek every opportunity I can find to write about fellow natives of this place who have and are doing great things in the world of cinema. It’s not only filmmakers and actors I profile either. You’ll find pieces about many different aspects of the industry as well as about people who don’t make films but instead showcase them for our entertainment and education. Take the subject of this profile, Dena Krupinsky, for example. When I wrote this article seven or eight years ago she was a producer at Turner Classic Movies in Atlanta, where she was one of the key figures behind those Private Screenings Q&A’s that host Robert Osborne does with legends. It was a dream job for her because she’s been in love with the movies for as long as she can remember and that gig put her in close contact with some of the biggest names in Hollywood history. She’s since moved on to teach at a university but her cinema obsession remains intact. I too have had the distinct pleasure of interviewing and in some cases meeting Hollywood royalty, past and present, including Robert Wise, Patricia Neal, Debbie Rynolds, Robert Duvall, James Caan, Danny Glover. I am hoping for an interview with Jane Fonda in the near future because she’s coming to Omaha for a July program at Film Streams that will have Alexander Payne interview her live on stage. Of course, Payne is someone I’ve interviewed dozens of times over the years and because of that relationship I’ve had the chance to interview Laura Dern, Matthew Broderick, Paul Giamatti, Thomas Haden Church, Sandra Oh, Virginia Madsen, producers Michael London, Albert Berger, and Jim Burke, screenwriter Jim Taylor, and cinematographer Phedon Papamichael.

Dena Krupinsky makes Hollywood dreams reality as Turner Classic Movies producer

Dena Krupinsky makes Hollywood dreams reality as Turner Classic Movies producer©by Leo Adam Biga

Orignally appeared in the Jewish Press

For most of us, childhood dreams remain just that — the unfulfilled musings of our starry-eyed youth. But for Omaha native Dena Krupinsky, an associate director with Turner Classic Movies (TCM) in Atlanta, her long-harbored fantasy of working with Hollywood greats has become reality. Since joining TCM in 1994, the year the national cable network launched, Krupinsky has produced dozens of special programs featuring stars and other notables from Hollywood’s Golden Age. Even a cursory glance at her producing credits reveals a Who’s-Who of movie royalty she has worked with — from Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Tony Curtis, James Garner and Rod Steiger to June Allyson, Leslie Caron and Liza Minnelli.

Whether in a digital editing suite or in a sound recording booth or in a television studio, she gets on intimate terms with some of the very luminaries she’s idolized. She might be producing a Private Screenings session in which James Garner recalls his career or she might be pruning a feature with Liza Minnelli discussing her father and his films or she might be recording a voice-over track in which Carol Burnett pays homage to Lucille Ball. “Do I wake up in the morning excited to go to work? Yeah,” Krupinsky said. “I feel like I’m doing exactly what I knew I’d be doing. It is a dream come true.” She has, in the course of putting together various programs, met dozens of Hollywood legends as well as many more obscure but no less significant film industry professionals. “I do feel lucky meeting these people. They were part of that Old Hollywood, which was an exclusive, elite world. And now that I’m part of it, I’m so excited. When I watch the Oscars I’ll see these people up there and go, ‘Yeah, know him, met him. Nice guy.’” That goes for screenwriter Ernest Lehman, a 2001 honorary Oscar recipient whom Krupinsky met while taping a program in which Lehman discussed how scenes from his script for North By Northwest were brought to inspired life by director Alfred Hitchcock.

Somehow, even as a little girl, Krupinsky knew she was destined to work in film or television. Growing up in the Rockbrook Park neighborhood, she was the oddball kid on her block who much preferred watching TV hour upon hour to playing outside with her friends. So enamored was she with whatever the magic box displayed that she would kvetch with her mother for extra viewing privileges. Although her parents, Jean Ann and Jerry Krupinsky, could not then see how such a steady diet of old movies, sitcoms, dramas, game shows, variety shows, soap operas and commercials could possibly benefit their daughter, it undoubtedtly has — embuing in her a deep affinity for popular entertainment that, if not a prerequisite for working at TCM, certainly helps. “It does. It definitely does,” said the perky Krupinsky during a June visit to Omaha for her 20th high school class reunion. She is a 1981 graduate of Westside High School and a former student at Temple Israel Synagogue. “I just always loved television and movies and I’ve just always known I wanted to be in them.”

During her recent visit from her home in Decatur, GA., a community near Atlanta, where she works, Krupinsky, who is single, wore a bright red dress that matched the burning intensity she has for her job. That job entails producing segments for the network’s (Channel 55 on Cox) Private Screenings, Star of the Month, Director of the Month and Spotlight features as well as producing special projects related to individual films, figures or themes, such as a new half-hour documentary, Memories of Oz, which has been well-reviewed in the national press for its informative and fun take on the making of The Wizard of Oz. She has worked with everyone from impish Mickey Rooney to serious method actor Rod Steiger and tackled themes from Religion in the Movies to the Art of the Con. Her work has been recognized in the industry with Telly awards for Private Screenings segments on Tony Curtis and Leslie Caron. a 1999 Gracie Allen Award for a Carol Burnett On Lucille Ball special and the 21st Annual American Women in Radio and Television Award for a series of interstitials (promotional links) on women in film.

Many of the stars that Krupinsky, a graduate of the prestigious University of Missouri School of Journalism, has worked with have since passed away, most recently Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau. A Private Screenings installment she did with Lemmon and Matthau remains one of her favorites, if for no other reason than she was enchanted with the man who originated the role of Oscar Madison on stage and on screen. “That was something that I loved to do. Walter Matthau was the greatest, funniest guy I ever met. I loved him. At one point, I was walking with him to show him where the Green Room is and he grabbed my hand. He was so sweet. He called me Charlotte the whole time. I’d be like, ‘No, it’s Dena.’ And he’d go, ‘No, no, I had a girlfriend named Charlotte, and you’re just like her.’ When he died I remembered this line he said that I loved during our taping session: ‘Dear, oh dear, I have a queer feeling they’ll be a strange face in heaven in the morning.’ And I thought of him and that line. Bless his heart.” Krupinsky invited her parents to attend the Lemmon-Matthau taping. She said she often tries sharing her Insider’s position with less experienced co-workers by letting them listen in on phone interviews. “I always like to have people listen because it’s too great a learning experience not to have your co-workers there.”

On one occasion, Krupinsky gathered a phalanx of Liza Minnelli fans in her office for a scheduled phone interview with the star only to have the diva surprise everyone by inviting the producer up to her place instead. “She said, ‘I’d love it if you could come to my house — I really don’t like to do phone interviews.’ And I was like, ‘Well, Liza, I’m in Atlanta and you’re in New York.’ She goes, ‘I’ll fly you up.’ So, I checked with my bosses and they said, ‘Go for it.’ I went to her house in New York and hanging on the walls were these big Andy Warhol prints — one of her, one of her mother and one of her father. Staring at those prints reminded me I was with a member of Hollywood royalty, and that her mother really was Judy Garland and her father really was Vincente Minnelli. She was as easy as an old friend, but I was in awe the whole time. It was great.”

Not at all jaded even after hobnobbing with scores of celebrities, the star struck Krupinsky said she still gets butterflies every time she meets one. “I’m always a little nervous, but the minute they start talking you kind of forget you’re scared.”

She said the stars are real troopers who go out of their way to make her and her colleagues feel comfortable being around them. “So far, they’ve all been so easy to work with and I think it’s because they want to tell their stories. They’re proud. They don’t do it for the money. They do it because they want to do it.” She said stars are put through their paces on a typical Private Screenings production day, which entails a three to three-and-a-half hour taping session, promotional intros and press interviews. “It’s an exhausting process, but never have we had problems. I’ve never had anyone complaining that it’s taking too long or demanding star treatment. They’re totally professional. When we bring them on to the set, they’re not worried or anxious. They just say, ‘I got it. I know what to do.’ And they love it. I feel like they have as much fun with us as we do with them. I mean, they even sit with the crew and eat lunch.”

With stars flying in to Atlanta for the tapings, opportunities abound for Krupinsky to hang with the screen legends. “We usually take them out to dinner the night before. Tony Curtis, whom we’ve worked with a lot, came with his wife Jill. We took them to dinner and shopping. Tony is a lot of fun. This is a guy who doesn’t want to rest. He wants to go out at night. He has fun with his celebrity. He gladly signs autographs.” Following a Private Screenings session with Best Actor Oscar winner Rod Steiger, Krupinsky was asked to escort the actor to a Florida film festival in his honor and she witnessed first-hand the respect and adulation audiences feel for this “very intense and very passionate” man.

One of the toughest parts of her job, she said, is trying to whittle down the star interviews from several hours to the one hour or less allotted for airing. For several months now she has been working on the edit for an August 2 scheduled James Garner Private Screenings segment. “James Garner’s has been one of the hardest to cut because he told so many good stories. I cut and cut on paper first and when I went to edit I thought for sure I‘d be fine but it was still too long. Cutting stories is the hardest part. Editing is a long process.” In preparing to tape a Private Screenings or to produce a special project like the Memories of Oz documentary, Krupinsky immerses herself in the project, gathering and reviewing reams of materials on the subject, including published interviews, biographies, tapes of movies and archival photos, with the help of staff researchers. “I become totally absorbed in my subject. For three months I can tell you everything about Tony Curtis or James Garner because I study them and I learn about these guys. I’ll know everything — dates, times, movies — you name it. But then once a project’s done that information goes away as I move on to the next one. The thing I love about my job is that I’m learning all the time. I feel like I’m still in school. It’s like having advanced film classes with experts talking about how they approach screenwriting or directing or acting.”

Krupinsky followed a logical route to TCM, working in local television promotion before graduating to the network level. Once out of college — and with her sights dead set on a career in TV — she took an entry-level job, as a secretary, at CBS affiliate WAGA-TV in Atlanta, where she was soon promoted to associate producer status — developing image campaigns and teasers for the station’s news and entertainment divisions. Even with the new position, she said, it was hard to get by on her small salary. “I was broke. I ate a lot at Taco Bell.” After a brief stint with a station in Knoxville, TN, she landed a spot as a writer-producer with Turner Network Television Latin America, which equaled a step-up on her career path but which also presented a dead-end since she did not speak a word of Spanish or Portugese. Then, in 1994, she heard about the formation of TCM and promptly applied for and won her current post. When she began at TCM, media mogul Ted Turner was still taking a hands-on approach with the fledgling network unlike today, when various mergers have taken Ted’s folksy presence out of the picture and replaced it with corporate suits. “Ted would always come by. One day, we had a meeting with him and he was wearing a cartoon tie and he was just hilarious,” she recalled. “Other times, he’d walk by the office and say, ‘Hey guys, what are you doing?’ Everyone who worked for Ted has this feeling for him because he did a great job. Thank God I was there for that regime.”

Before joining the ranks of film buffs and cinephiles at TCM, Krupinsky acknowledges she was a bit out-of-step with her workmates because even though she loved movies, she lacked a deep knowledge of their history and lore. As an example, she points to Warner Brothers tough guy John Garfield, someone she was assigned to do a feature piece on and knew next to nothing about. “Before I did John Garfield I didn’t know who he was to be honest. I told my mom who I was profiling and she said, ‘Oh, John Garfield, he’s great. You’ll fall in love with him.’ I said, I will?’ And sure, enough, I did. You almost fall in love with all these people.”

The Garfield project led Krupinsky to the late actor’s daughter Julie Garfield, an actress, who provided personal insights into the man, and to former director Vincent Sherman, who directed Garfield in the 1943 drama Saturday’s Children and who worked with many other Warners greats in the 1930s and ‘40s. Krupinsky played matchmaker of sorts when she arranged for the two to meet. “I brought Julie and Vincent together for lunch and it was great to sit back and let him tell her stories about her dad that she didn’t know. I was kind of proud myself because I brought these two together.” Krupinsky feels privileged getting the inside scoop from veterans like Sherman, who at 95, is one of the last surviving directors from Hollywood’s classic studio era. Sherman knew everyone on the Warners lot and hearing him talk about the old days and the old stars is like getting the Holy Scripture from the prophet himself. “I had lunch with him and he was telling me stories about Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, and I’m sitting there thinking, ‘Oh, God, I’m sitting here with a man who worked with these legends.’ I mean, it is very cool. Vincent’s become a friend of our network’s.”

A large part of her producing chores involves developing scripts, which generally include narration read by a star or stars who have some relationship with or enthusiasm for the subject. For example, to promote a month-long salute to the late producer-director Stanley Kramer, Krupinsky hit upon the idea of having comic Jonathan Winters, who appeared in Kramer’s It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, wax nostalgic about the filmmaker, with whom he was quite close. She interviewed Winters by phone and developed a script from his comments that adhered very closely to his own words. The resulting Winters’ salute was a surprisingly sober, reflective and personal reminiscence. When it comes time for the star to record the narration, as in the case of Winters, leeway is given for the star to go off-script and improvise. “They’ll paraphrase and add their own little things,” Krupinsky said, “and so it almost sounds like it’s off-the-cuff, and a lot of times it is.”

Among new and proposed projects, Krupinsky is now brainstorming ideas to promote TCM’s scheduled Coming of Age theme in October. She would like to get a Matt Dillon or Diane Lane or Reese Witherspoon to host the Coming of Age festival. Another idea she has is to get Dustin Hoffman alone or as part of a reunion of the cast of The Graduate. Other projects she would like to see happen range from a special on the Marx Brothers (she recently interviewed Carl Reiner on that comedy team) to Private Screenings segments with Shirley MacLaine, Elizabeth Taylor, James Coburn and Jerry Lewis. She is also busy thinking of some project that would be a good fit for Steve Martin to host/narrate.

Pitching projects is part of what Krupinsky or any producer does. She feels fortunate having superiors who value her input. “The cool part about my job is that as producers we have a lot to say. It’s not like, ‘Hey, Dena, your next assignment is…’ It’s more like, ‘Hey, Dena, here’s the programming we’re thinking of doing and we want you to come up with ideas.’ I can come back and say, ‘Let’s try this,’ and they’ll say yes or no, but a lot of times they say yes. That’s why I love my job. Like the Lemmon-Matthau Private Screenings. That was mine. I wanted to do something on comedy teams and I thought of Lemmon-Matthau and I did it. And the cool thing is you get to do this stuff with people you’ve always admired and wanted to meet.”

For now, Krupinsky is content at TCM, but she can see herself moving on, perhaps to produce feature-length documentaries. “I think about it all the time and I do feel like I am making a slow progression towards it. I’m doing great stuff now but I always feel like there’s something else I could be doing out there. I don’t want to ever get away from this work. Even if I moved on I still want something to do with Older Hollywood. Right now, though, I’m happy where I am.”

Related articles

- TCM fest calls film buffs and others (variety.com)

- Classic Stars Trash Hollywood (foxnews.com)

- Penelope Andrew: TCM Fest 2012:Liza Minnelli, Kim Novak, Robert Wagner, Debbie Reynolds Walk Red Carpet (huffingtonpost.com)

- Lucille Ball’s 100th birthday celebrated (cbsnews.com)

- Que Sera Sera! Happy Belated Birthday Doris Day! (pbenjay.wordpress.com)

- Casablanca Again On The Silver Screen: 70th Anniversary (morningerection.wordpress.com)

The wonderful world of entertainment talent broker Manya Nogg

Behind virtually every television commercial, corporate training video, TV show, music video, movie, stage show, and lifestyle print ad is someone like Omaha-based Manya Nogg, whose job is to locate or identify talent and a lot of other things for producers and creative directors. Without her, the show or project does not go on, or only does so after a big headache because she serves to expedite things that take valuable time in a field where time is money. She’s been doing this talent broker thing for decades, and it’s just one manifestation of a lifelong enchantment with show biz, entertainment, and the arts that has seen fill all sorts or roles, as writer, director, producer, editor, casting director, makeup artist, production assistant, and on and on. She’s worked in film, TV, theater. She writes articles and reviews. She teaches. No spring chicken either, she’s still quite active juggling a multi-faceted career. That was true when I profiled her a half-dozen years ago or so, and it’s still true today.

The wonderful world of entertainment talent broker Manya Nogg

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Jewish Press

Who am I this time?

It’s a question brassy, breezy Manya Nogg might well ask given the chameleon-like life she leads and endless ways she reinvents herself. There’s Manya the wife and mother, the entrepreneur, the writer, the teacher, the motivational speaker, roles that overlapped her work as a makeup artist, television crew member, ad agency hack, city film commissioner and race horse owner.

In her current guise as founder-manager of the talent brokerage house Actors Etc. and of the dramatic presenting group Theater-to-Go, both of which she operates with her son, Randy, she wears many hats in trying to please clients and audiences alike. A day-in-the-life of Manya Nogg is sure to find her working the phone and perhaps rounding up human or animal talent, scouring salvage or thrift stores for one-of-a-kind props, searching far and wide for just-the-right locations, organizing-designing events and maybe even filling-in for an actor unable to go on.

She’s a whirling-dervish, hell-on-wheels, one-woman band with enough chutzpah, guile and wit to hold her own with anyone. Whether hanging with Teamsters on a set or meeting with button-down execs in a conference room, she can joke, quip and swear with the best of them and outlast them pulling all-nighters.

All of which brings us back to, Who is Manya Nogg anyway? “Anchor me down, honey? It’s like trying to catch the wind,” she tells a visitor to her Omaha home. “You can call me a broad, you can call me fat, but if you call me old, I will find out where you live.” A clue to what makes her tick is the joy her variegated work brings. “Being able to take an idea and bring it to fruition…to fulfill your own artistic vision…to have an idea and see where you can go with it, that creative part of taking something from nothing has always been very exciting to me. I love that.”

Actors Etc. is nearing its 30th anniversary as a media production supplier furnishing producers of commercials, TV movies, feature films and industrials with everything from actors and crafts people to props to caterers to location scouting services. Theater-to-Go presents live performances of original Who-Done-It mystery party games and TV-movie parodies at receptions, conventions, meetings and seminars.

Her search for new identities began during the post-World War II boom, when no sooner did she graduate from Central High School than the former Manya Friedel boarded the train to California as another starry-eyed Midwest girl pursuing silver screen dreams. “I graduated on Friday and left for Hollywood on Sunday,” is how she describes the start of her adventure. She was only 17. And the shy girl known then as “Doc” was following through on her long-held ambition “to be an actress.”

Aside from a one-time desire to be a nurse, Nogg’s what-do-I-want-to-be-when-I-grow-up visions were always golden-hued, like her wish to be a professional ice skater. “I don’t march to the same drummer as a lot of people,” she says.

Her movie aspirations were fired by the hours she spent watching movies, especially at the neighborhood Lothrup Theater, where her parents deposited her once a week while they played cards with the theater’s owners across the street. There, in the darkened cinema, basking in the glimmer of bigger-than-life images emblazoned before her, a young girl’s show business dreams took flight under the spell of stars like Bette Davis in Now, Voyager and character actresses like Agnes Moorehead in The Magnificent Ambersons and Judith Anderson in Rebecca.

But Nogg, who grew up an only child of practical parents that owned both a garage and the Omaha Broom Company, was not putting her eggs all in one basket. In school, she learned a more down-to-earth facet of show biz that became her backup for breaking into the movies. “Central High School had a marvelous theatrical makeup department and I just fell in love with it,” she says. “I started taking stage makeup and it became so much part of me I ended up becoming the student makeup mistress. I did this for three years. As a matter of fact, the teacher got married during the school year and was gone a week, and I taught the class.”

Still, she had little more than pluck when she made the trip west. Amazingly, her parents let her go without much of a fuss. “In retrospect, it kind of blows my mind they let me do what I did,” she says. “It took a lot of guts.” Easing their fears was the fact Nogg would be rooming with a friend who’d earlier ventured out there. Soon after arriving, reality set in. First, a Hollywood strike was on, meaning jobs were scarcer than usual in a ruthless town filled with wannabes. Next, she was unschooled and unprepared for the ins-and-outs of getting noticed. She had no agent, no head shots, no nothing except her naked ambition.

Embarking from the one-room apartment she shared in “a not so good part of downtown L.A.,” she made the rounds at the studios and the central casting office and “found out right away” she “couldn’t get in for an interview or audition” as an acting hopeful. Worse, she discovered women were shut out of makeup artist jobs and instead confined to hair stylist jobs, but in order to qualify she needed “a hair degree” from a cosmetology school, which she didn’t have.

Then, her beating-the-pavement paid off when she wandered into the offices of something called Stage Eight Productions, which turned out to be her gateway into the embryonic but soon-to-be burgeoning TV industry.

“Its head, Patrick Michael Cunning, was literally one of the pioneers of television in this country. He had one of the first production companies. He was one of the first directors. Edgar Bergen was a partner,” says Nogg, who didn’t know any of this when she arrived. “They were over on Sunset (Boulevard) and I walked in and Cunning was looking for a production assistant. The fact I knew makeup appealed to him and so I went to work for Stage Eight, and it was the Harvard of experiences. They wrote and produced everything themselves.”

Under Cunning’s guidance, Nogg did makeup, film editing, writing and assistant directing for some of TV’s earliest live dramatic programs, including its signature series of Tom Sawyer shorts, which were first done live and then redone on film. The films’ players worked as an ensemble troupe. “I was blessed that he let me write for them. What I would do is…be at every rehearsal and take down everything in short-hand, and go home and distill a script they would all be a little familiar with. They worked so well together they did not need tons of rehearsal. They could take my skeleton script and improvise. Then, eventually, I got to direct the Tom Sawyer Kids.” She counts Cunning among the “mentors” she’s been “lucky enough to have” who were “so professional and taught me so much about the business.” The only drawback was the less-than-living wage paid.

Cunning allowed her to get the acting bug out of her system and to find her true creative calling behind the scenes. “He knew I wanted to be an actress and he let me do some acting. I was doing a dramatic scene once that called for me to go from frightened to hysterical,” she recalls. “Well, I ended up being hysterical, not from anything in the scene, but because I realized I didn’t want to be the very thing I went out there to do. I was introverted and shy enough, and nobody knew this, that I wasn’t comfortable sharing me or putting myself out there. That’s when I went behind the camera, and I loved it. I love being behind the camera.”

Although Stage Eight proved a good “training ground,” Nogg became “frustrated in California” with the low pay and her inability to “make a dent in the film industry” and she sought a new start in Chicago, where she worked at Paramount Pictures-owned WBKB-TV, “one of the first genuine television stations in the country. By then, they were doing really hot stuff. They were on the air pretty much all day long. Kukla, Fran and Ollie started there. Marlin Perkins’ Zoo Time, the forerunner of Wild Kingdom, started there. I was technically a publicity assistant but my duties spilled over into working as a film editor, makeup artist, assistant director and writer. I did live interviews from Arlington Park.”

Life then threw her a curve when her father died. After a period of mourning in Omaha, she went back to Chicago, but soon returned here to be with her mother. With all that experience gained in Hollywood and Chicago, the indefatigable, unsinkable “Manya Brown” had no trouble starting over and selling herself again. In quick succession, she nabbed jobs at Universal Advertising and KBON Radio and snagged a husband in businessman Alvin Nogg, son of the late Nathan Nogg, whose Nogg Paper Company is still going strong today. She raised the couple’s two children, Randy and Sharon, and took part in managing some of her husband’s many other business interests, including the company that became Lancer Label and the family’s stable of racing and show horses. From the 1960s through the early ‘70s, she whet her creative appetite by doing makeup, props and costumes at the Omaha Community Playhouse and by working as a Docent at the Joslyn Art Museum, whose women’s association she was active in. The Noggs numerous civic activities extended to the downtown Kiwanis chapter, which her husband headed, and to the Knights of Ak-Sar-Ben, where the couple’s daughter, Sharon, was a princess.

All this time, Nogg kept her hand in the media world as a freelance makeup artist and jack-of-all-trades in support of local commercial/industrial shoots. Her wealth of experience and keen networking skills gave her contacts in theater, TV/film production and the service industries that few others could match. When a TV client called with what seemed a tall order — “He said, ‘I want a guy to be able to walk around with a sandwich board on, but I want it to be a vault that will open up and that kids can reach into and grab candy’” — Nogg replied, “I’ve got just the guy for you.” That guy was Tom Casker, the then-set designer for the Omaha Community Playhouse. She called and a conversation ensued with Casker’s wife, Diane Casker, who was also working in local film production.

“By the time we got done talking, we had formed a new company. Between she and Tom and myself, we had done everything.”

Nogg and Diane Casker formed Illusions Unlimited, the predecessor of Actors Etc. “She was a wonderful gal, and we did magic together,” Nogg says of her late partner. She recalls that as women officing from home they encountered flak from the then-male-dominated ad agency ranks until they unloaded with some what-does-where-we-office-have-to-with-our work? straight talk.

The intent with Illusions was to offer location services for out-of-town and local production companies. To announce themselves with more pizzazz than the usual card or brochure, the partners stole an idea from TV’s Mission Impossible by recording a dramatic pitch on an audio playback machine, complete with a mock self-destructing tape, and delivering it to prospective clients. Nogg explains, “Our recording went, ‘Dear agency director…this is your mission, and should you choose to accept it,” and it said who we were and how we could be contacted. Then, at the end, and I don’t know how he did it, Tom inserted a powder package and when the tape ended, smoke poofed out. We could only afford one tape recorder, so we dropped it off one company at a time. We called a day or two later to ask if we could come visit. And, of course, we had hooked them with that.” Nogg says she and Casker only had to pull the stunt a few times before bagging a big client.