Archive

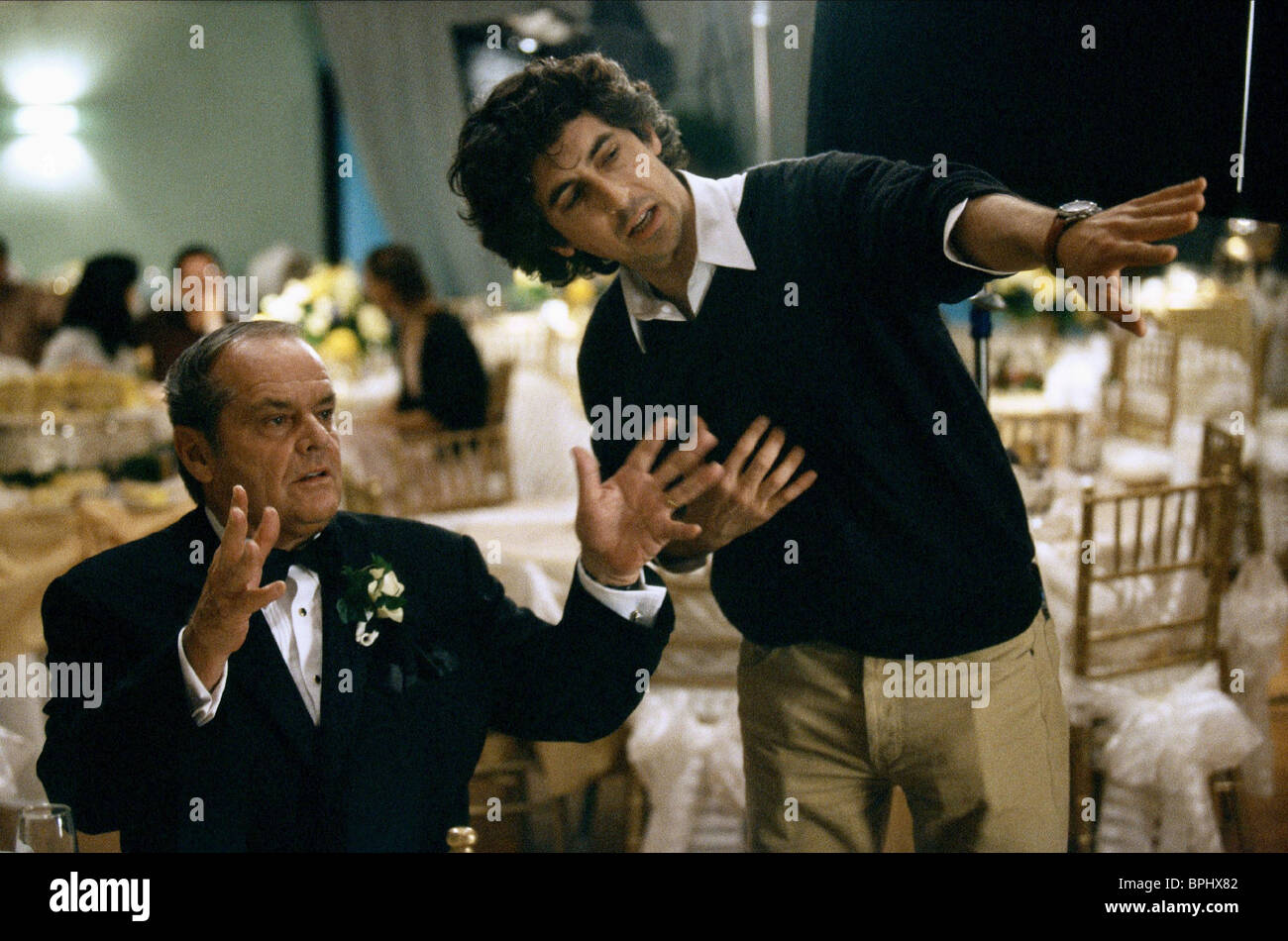

Alexander Payne on working with Jack Nicholson

Alexander Payne on working with Jack Nicholson

©by Leo Adam Biga

Drawn from my book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film

As I wade through the edit on the new edition of my Alexander Payne book, I am coming across some things that I am selectively posting, including this aggregation of quotes and musings in which Payne refers to working with Jack Nicholson on About Schmidt. Getting Nicholson to star in the film, in a part that requires he be on screen for virtually its entire duration, was a huge turning point in Payne’s career trajectory but what really catapulted Payne to the upper echelon of cinema was the great performance he elicited from Nicholson in the lead part of a killer script that Payne co-wrote with Jim Taylor and that Payne brought to the screen as the film’s director. Payne grew up watching Nicholson’s work in that decade of 1970s American film that was so foundational for the filmmaker and his own work as a writer-director. It meant a lot to Payne to have Nicholson deliver the goods in what was Payne’s biggest film, in terms of budget, prestige and risk, up to that point.

NOTE: The new edition of Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film releases September 1. It is the only comprehensive treatment of the Oscar-winning Payne in print or online. It is a collection of articles and essays I have written about Payne and his work over a 20-year span. I have basically covered him from the start of his filmmaking career through today. The book takes the reader through the arc of his filmmaking journey and puts you deep inside his creative process. There is much from Payne himself in the pages of the book since most of the content is drawn from interviews I have done with him and from observations I have made on his sets. I also have a good amount of material from some of his key collaborators.

I self-pubished the book in late 2012. It has received strong reviews and endorsements. I am releasing a new edition this summer with the help of a boutique press here, River Junction Press, and its publisher Kira Gale. The new edition features major content additions, mostly related to Payne’s Nebraska and Downsizing. It will also feature, for the first time, a Discussion Guide and Index, because we believe the book has potential in the education space with film studies programs, instructors, and students. But I want to emphasize that the book is definitely written with the general film fan in mind and it has great appeal to anyone who identifies as a film buff, film lover, film critic, film blogger. It has also been well received by filmmakers,

Kira and I feel hope to put the book in front of the wider cinema community around the world, including producers, directors, screenwriters, festival organizers, art cinema programmers. We feel it will be warmly embraced because Payne is one of the world’s most respected film artists and everyone wants to work with him. People inside and outside the industry want to learn his secrets and insights about the screen trade and about what makes him tick as an artist.

Alexander Payne on working with Jack Nicholson

NOTE: These excerpts are from 2001-2002 articles I wrote and that appear in my book

Alexander Payne derives much of his aesthetic from the gutsy, electric cinema of the 1970s and therefore having the actor whose work dominated that decade, Jack Nicholson, anchor his film About Schmidt is priceless.

“One thing I like about him appearing in this film is that part of his voice in the ‘70s kind of captured alienation in a way,” Payne said, “and this is very much using that icon of alienation, but not as someone who is by nature a rebel, but rather now someone who has played by the rules and is now questioning whether he should have. So, for me, it’s using that iconography of alienation, which is really cool.”

Beyond the cantankerous image he brings, Nicholson bears a larger-than-life mystique born of his dominant position in American cinema these past thirty-odd years. “He has done a body of film work,” Payne said. “Certainly, his work in the ‘70s is as cohesive a body of work as any film director’s. He’s been lucky enough to have been offered and been smart enough to have chosen roles that allow him to express his voice as a human being and as an artist. He’s always been attracted to risky parts where he has to expose certain vulnerabilities.”

The film’s title character, Warren Schmidt, is a man adrift in a late life crisis where the underpinnings of his safe world come unhinged, sending him reeling into an on-the-road oblivion that becomes a search for redemption. Because the story is really about a man’s inner journey or state of mind the film is not so much driven by traditional narrative as it is subtext.

“This film isn’t so much about the story because there isn’t really much of a story. It’s about a man and kind of about a way of life,” Payne said. “And it’s a way of life I kind of witnessed in Omaha. Not that it doesn’t exist elsewhere and not that many different lives don’t exist in Omaha. But, from time to time, it has a whiff of something that’s very genuine. It’s just a feeling, and I’d be hard-pressed to describe it beyond that.”

As an artist, Payne does not like limiting himself to expository narrative. He understands how seemingly whimsical, quirky or incidental elements, like the moon serenade in Citizen Ruth or the lesbian romance in Election, have value too.

“One thing Hollywood filmmaking urges you always to do is tell the story. If it’s not germane to the story, then leave it out. And I kind of disagree with that,” he said. “I mean, I like stories. I like seeing movies that tell stories. I like my movies to tell stories. But films don’t operate only on a story level. There’s a quote I like that says, ‘A story exists only as an excuse to enter into the realm of the cinema.’ Films operate on emotions, moods, sub-themes and maybe even poetry, if you’re lucky enough to have a bit of mystery and poetry in your film.”

If the screenplay is any guide, then reading it reveals Schmidt as a man who has built his life around convention and conformity but who, along the way, has lost touch with what he really is and wants. The things in his well-ordered life have become his identity. His actuarial job with Woodmen of the World Life Insurance. His office. His home. His routine. His marriage. When, in short order, he retires, his wife dies and his estranged daughter prepares to marry a man he does not like, he realizes he is alone, at odds, angry and restless to find answers to why his supposedly full life seems so empty.

What makes Schmidt’s dilemma more complex is that he is not a wholly likable man. He is a square, a miser, a malcontent. Payne is drawn to such richly shaded and often unsympathetic characters because they are more interesting, more real, more truthful. Just think of inhalant addict mother-to-be Ruth Stoops in Citizen Ruth or arrogant, spiteful teacher Jim McAllister in Election. Neither is totally a shit, though. Stoops is brave, outspoken, independent. McAllister is sincere, caring, dedicated. And, so, Schmidt is solicitous, careful, reflective. As he begins defining a new life for himself without a job or wife, he begins behaving in ways that defy family-societal expectations.

In this way, the film is an indictment of the prefabricated mold people are expected to fit. With Schmidt, Nicholson mutely echoes the alienated character (Bobby Dupea) he essayed in 1970’s Five Easy Pieces. Just as Dupea turns his back on his classical piano career and blue blood roots to work the oil fields, Schmidt shucks his constraints to embark on a road trip that is as much escape as quest.

Then there’s the whole star power thing Nicholson brings. The clout Nicholson wields. The Player label he wears. The attention he commands. Payne is savvy enough to know that having Nicholson on the project boosts the prestige and the pressure that goes with it. That’s why this production is a little more all-business and a little less laid back than Payne’s previous two. For example, the filmmaker is, for the time being anyway, giving no interviews (outside this one) and the set is closed to reporters.

This limited access all gets back to the Nicholson factor. It means catering to him and shielding him.

Or, as Payne put, “we have a big fish on this one. Everyone knows him. Most everyone is a fan of his. Plus, there’s the Pop stuff of his winning three Academy Awards and having been in very many popular and artistic films. So, he’s a big presence in American culture. And all of us, certainly from me down to the crew, want him to be impressed. We want him to feel protected and supported. We want to feel that we have his approval. And, as director, I’m really bending over backwards to make sure he feels comfortable enough so he will expose vulnerabilities and really dive into the part. So, just because of his stature there is a heightened will among the film company and crew to do a good job.”

Making no bones about what a fan he is of Nicholson, Payne said his star has thus far been a filmmaker’s dream.

“Sometimes, you think about a movie star as being more star than actor, kind of playing some version of themselves. That’s not the case with Mr. Nicholson. He’s all about the character. He really dives into who is that person. He’s a consummate actor. I’ve been really impressed with what I’ve seen so far. And I think watching the character unfold through him is going to be really amazing.”

Instead of full-blown rehearsal periods for the film, Payne, Nicholson and the film’s other name actors, who include June Squibb as nis wife, Hope Davis as the daughter, Dermot Mulroney as the future son-in-law and Oscar-winner Kathy Bates as the future in-law, have held script readings. According to Payne, Nicholson is not throwing his weight around, as one might expect, but rather acting as a colleague and collaborator.

“My experience so far is that he expresses his opinions as he sees them and he tries to be helpful to me and to the process. He seems to respect the filmmaker. So far, it’s been a really interesting collaboration. And I also think I have much to learn from him, so I welcome his input.”

Nicholson became attached to the project through the kind of old-boy networking Hollywood thrives on. The actor was given Begley’s book by his old friend, producer Harry Gittes (whose name Nicholson appropriated for the private eye he played in Chinatown). Then, Payne came on board, writing the script with Taylor and being assigned directorial chores as well. All Payne knew was that Nicholson would read the finished script first.

“And, oh, thank God he liked and agreed to do it,” Payne said. On a practical level, Nicholson’s participation has meant a much bigger budget than Payne has worked with before. “It’s around $30 million. Mr. Nicholson’s getting a salary which is larger than actors have gotten in my previous movies. Another factor is that this is a union movie, where my previous two were non-union, so there’s a little added cost there.

“Thirty (million) is actually quite modest – it’s hard to believe, I know – by Hollywood standards. And it’s really amazing this script is getting made with this caliber of star at that budget level, because there’s no gimmicks, no special effects, no guns. It’s just a guy in crisis.”

Nicholson’s presence netted a bigger budget than Payne ever had before, which meant New Line insisted he use sound stages and multiple cameras as safeguards against cost overruns caused by shooting delays.

“Because it’s not a terribly commercial film and because it’s somewhat costly I was urged to not go over budget. I had to make all my days, so in order to do that I shot more on sound stages and I sometimes threw up two or three cameras. I’d used sound stages on a limited basis before because, one, we didn’t have the budget to build sets and, two, I don’t really trust it, I trust what exists. But practical locations, as they’re called, are difficult. They’re tight. You wreck people’s front lawns.

“Building sets and shooting on them poses its own logistical problems, but it also solves a lot of problems. And rather than shoot from one angle and then move in closer, I tried to get both (shots) at once. I like doing it precisely for the reason of not wearing out the actors and saving time.” In the end, Payne did meet his sixty two-day schedule.

Despite the hike in budget, the presence of a superstar and the imposition of union realities, Payne insists the film, which is being made for New Line, remains closer to his first two intimate independent features than to overblown mainstream Hollywood pics.

“The scale of filmmaking is, for me, not that much different than my previous two. A lot of directors, as they get older or have more films under their belt or have more success or whatever, they consistently make bigger, more impersonal films. I am conscious of wanting to make increasingly more personal films.”

Directing Nicholson allowed Payne to work with an actor he greatly admires and solidified his own status as a sought-after filmmaker. He found Nicholson to be a consummate professional and supreme artist.

“Nicholson does a lot of work on his character before shooting. Now, a lot of actors do that, but he REALLY does it. To the point where, as he describes it, he’s so in character and so relaxed that if he’s in the middle of a take and one of the movie lights falls or a train goes through or anything, he’ll react to it in character. He won’t break.” Payne said Nicholson doesn’t like a lot of rehearsal “because he believes in cinema as the meeting of the spontaneous and the moment. His attitude is, ‘What if something good happens and the camera wasn’t on?’”

By design, Nicholson carries the film. He is in virtually every scene. That Payne got him to play the lead in the first place was a coup. That he worked with an artist he’s long admired was cool. In an interview Payne gave the Omaha Weekly only days before shooting began, he said the actor was accommodating in every way, immersing himself in the part and making himself available to the entire process during script readings. Now months removed from the shoot, Payne said Nicholson remained a pro throughout the production and his extraordinary talent provided him as a director with endless choices.

“I had a very excellent experience working with him. He was extremely professional and committed to his part. Jack Nicholson is a movie star and an icon and that’s fine, but in the moment of doing it and really who he is in his heart he’s an actor who gets nervous like other actors and wants to do a good job like other actors and hopes he got it right like other actors and needs reassurance like other actors.

“What was great about directing him was that unlike many situations where you give the direction and hope to God the actor can do it just the way you’d like him to or you hope you’ve thought of the right words that will trigger the right response, with Nicholson I had to be careful with what I told him because not only would he do it, he could do it. He just has an excellent instrument. Sometimes, when I’d impose blocking or I wanted a certain scene a certain way, I’d say, ‘Is that all right with you’ and he’d go, ‘Well, anything you come up with I can find a way to justify it to myself, so, what do you want?’ I was like, ‘Ohhhh…’ He makes every possible choice doable.”

Payne said, “There’s always a bit of nerves between actors and director the first couple weeks as you’re learning to trust one another.” That was true at the start of Schmidt, as Nicholson felt Payne out, but in short time “he made it very easy to direct him. He put a lot of appreciated effort into breaking the ice with those around him. He was very professional and very cool and very kind.”

The crowds of fans that followed the Schmidt traveling all-star band from location to location have long dispersed since production wrapped.

If reaction to the film by preview audiences is any gauge, than Payne may be striking the right chords with this gray, introspective story. He said test cards consistently use words like “real,” “true-to-life,” “genuine,” “naturalistic” and “not funny” to describe it. “And that’s been kind of nice,” said Payne, whose aesthetic is informed by the European and American cinema of the last Golden Age (the 1960s and ‘70s) when the best films were about real life. Payne said the September 11 terrorist attacks “helped cement more than ever my already existing desire to make human films – films which are about people.”