Archive

Nik Fackler, The Film Dude Establishes Himself a Major Cinema Figure with ‘Lovely, Still’

Now that filmmaker Nik Fackler’s first feature, “Lovely, Still,” has a national theatrical release scheduled, the buzz about the film, its writer-director, and its stars, Martin Landau and Ellen Burstyn, is getting serious. I noticed that a Nik Fackler profile on my site has been getting a fair number of hits, and so today I decided to re-post a more recent piece about Nik and his film. Check it out. I will also be adding other Fackler-“Lovely, Still” articles I’ve done. Around the time the film has its national release this fall, I will be adding new posts related to it all. That will include an extensive interview with Martin Landau.

My site also contains articles about many other cinema subjects and figures, including Alexander Payne. Check them out.

Nik Fackler, The Film Dude. establishes himself a major new cinema figure with “Lovely, Still”

This article on emerging filmmaker Nik Fackler makes no bones about his establishing himself a major cinema figure on the strength of his first feature, Lovely, Still. The pic is finally getting a general release this fall, but it’s picked up a slew of admirers and awards, most recently from screenings at the California Independent Film Festival. Watch for this film when it comes to a theater near you or plays on cable or wherever else you can find it, because it’s the work of an artist who will make his presence felt. As he prepares to make his next projects, I feel the same way about Fackler that I did about Alexander Payne when I saw his debut feature Citizen Ruth – that this is an important artist we will all be hearing much more from in the future. I look forward to charting his journey wherever it takes him.

NOTE: This article appeared in advance of a limited engagement run of Lovely, Still in Nik’s hometown of Omaha last fall. The film is having a full national release the fall of 2010. Look for it at a theater near you in September or October, perhaps later.

Check out my most recent post about the film, Fackler, and the relationship between he and star Martin Landau.

Nik Fackler, The Film Dude, sstablishes himself a major new cinema figure with “Lovely, Still”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

After what must seem an eternity, Omaha’s resident Film Dude, writer-director Nik Fackler, finally has the satisfaction of his first feature being theatrically screened. An advance one-week Omaha engagement of his Lovely, Still opens the new Marcus Midtown Cinema, Nov. 6-12.

The film’s box office legs won’t be known until its 2010 national release. Screenings for New York, L.A. and foreign press will give Lovely the qualifying runs it needs for Academy Awards consideration next year. It’d be a stretch for such a small film to net any nominations but the lead performances by Martin Landau and Ellen Burstyn are so full and finely honed they’re Oscar-worthy by any standard.

Both artists strip themselves emotionally bare in scenes utilizing all their Method gifts. Their work is: dynamic, never dull; natural, unforced. Their behaviors appropriate for the romantic, comedic, dramatic or just Being There moments.

Nods for writing, direction, cinematography, editing and music would be unlikely but not out-of-line for this gorgeous-looking, powerfully-rendered, well-modulated movie that hits few false notes. The film pops with energy and emotion despite a precious storyline of senior citizens rediscovering first love.

The local creative class is well represented by Tim Kasher’s “additional writing,” James Devney’s strong portrayal of Buck, a lush score by composers Mike Mogis and Nate Walcott and dreamy tunes by Conor Oberst and other Saddle Creek artists.

It’s at least as impressive a feature debut as Alexander Payne’s Citizen Ruth.

An indication of how much Landau believes in Lovely and how proud he is of his gutsy star-turn in what Fackler calls “a showcase role that’s very challenging” is the actor’s appearances at select screenings. That includes this Friday in Omaha, when he and Fackler do Q & As following the 6:15 and 9:15 p.m. shows at Midtown.

Fackler’s at ease with the film that’s emerged. “I am very content, although it has changed a lot,” he said, “but I welcome all changes. Film is an ever changing beast. You must embrace the artistic transformation. To not allow it, is to limit it.” Much hype attended the making of the 25-year-old’s debut feature, shot in his hometown in late 2007. It was the first movie-movie with a real budget and name stars made entirely in Nebraska since Payne’s About Schmidt in 2001.

Circumstances caused the film that generated serious buzz a couple years ago and then again at the Toronto Film Festival’s Discovery Program in 2008 to fall off the radar. Lovely producers turned down a distribution offer. They continue negotiations seeking the right release strategy-deal. Self-release is an option.

It’s been a long wait for Fackler to see his vision on screen – six years since writing it, five years since almost first making it in 2005, two years since completing principal photography and one year since reshoots and reediting.

“This has been the longest I’ve like worked on a single project for forever,” he said. “It’s really been a marathon.”

Anticipation is great, not just among the Nebraska film community that worked the pic. Whenever stars the caliber of Landau and Burstyn throw their weight behind a project as they’ve done with Lovely the industry takes note. That a 20-something self-taught filmmaker with only micro-budget shorts and music videos to his name landed Oscar-winning icons certainly got people’s attention. As did hanging his script’s sentimental story about two old people falling in love at Christmas on a subversive hook that turns this idyll into something dark, real, sad and bittersweet. Throw in some magic realism and you have a Tim Burtonesque holiday fable.

The two stars would never have gotten involved with a newcomer on an obscure indie project unless they believed in the script and its author-director. At the time Fackler lacked a single credit on his IMDB page. Who was this kid? In separate meetings with the artists he realized he was being sized up.

“It was really intimidating,” Fackler said of meeting Landau in a Studio City, Calif. cafe. “I was just super freaked out. I don’t know why. I’m usually never that way. But it was like I was about to meet with this legend actor to talk about the script and for him to kind of like feel me out — to see it he can trust me as a director, because I’m a young guy. We’re from such different generations.”

The two hit it off. Lovely producer Lars Knudson of New York said Fackler “aced” a similar test with Burstyn in Manhattan: “It’s a lot of pressure for a (then) 23-year-old to meet with someone like Ellen, who’s worked with the biggest and best directors in the world, but Nik blew her away. I think she called him a Renaissance Man.” Knudson said “it’s really impressive” Fackler won over two artists known for being ultra-selective. “They’re very critical. They’ve done this for so many years that they will only do something if they really believe it’s going to be good.”

Lovely producer Dana Altman of Omaha said the respect Fackler gave the actors earned him theirs.

Anyone reading the screenplay could see its potential. Besides A-list stars other top-notch pros signed on: director of photography Sean Kirby (Police Beat), production designer Stephen Altman (Gosford Park Oscar nominee) and editor Douglas Crise (Babel Oscar nominee).

But the history of films long on promise and short on execution is long. As Dana Altman said, any film is the collective effort of a team and Lovely’s team melded. On location Fackler expressed pleasure with how the crew – a mix from L.A. and Omaha – meshed. “Everyone’s on the same wavelength,” he said. Still, it was his first feature. DP Sean Kirby said, “Anytime you do something for the first time, like direct a feature film, there’s a learning curve, but I think he’s learned very quickly.” Fackler admitted to making “a bunch of mistakes” he “won’t make again.”

The subject matter made the film rife with traps. Take its tone. Handled badly, it could play as treacle or maudlin. Instead, it reads poignant and tragic, and that’s to everyone’s credit who worked on the film.

Then there’s Fackler’s penchant for going on fantastical jags in his work, routine in videos but risky in features. His loose approach, such as ditching the shot list to improvise, combined with the total creative freedom producers granted, meant he could play to his heart’s content, within reason. That can lead to self-indulgent filmmaking. Indeed, he fought and won the right to shoot trippy dream sequences that ended up on the cutting room floor. But some experimental lighting techniques to express tangled memories do make an effective motif in the final cut.

Following the mostly positive Toronto showing, the team reassembled for Omaha reshoots and New York pick ups. His leads supported the fixes and coverage.

“Martin and Ellen were behind it, they weren’t annoyed by it, they thought all the reshoots were going to make the film better,” said Fackler. “It wasn’t something that felt forced or anything like that. Everyone was on the same page.”

The young artist and his venerable stars established an early rapport built on trust. “We became friends,” he said. He readily accepted ideas from them that helped ripen the script and gave its young creator deeper insights into their characters.

“What’s great about Nik, especially at his age, is he’s willing to collaborate with people. It’s still his vision, but if it makes it better he’ll change it, he’s not afraid,” said Knudson, who said the script owes much to the input of Landau and Burstyn. “He’s very sort of ego-less.”

It’s all in line with Fackler’s predilection for creating a relaxed set where spot-on discipline coexists amid a way-cool, laidback sensibility that invites suggestions. On location for Lovely he exhibited the same playful, informal vibe he does on his videos: whether going “yeah, yeah” to indicate he likes something or pulling on a can of Moen between takes or doing a private, Joe Cocker dance watching scenes or saying to his DP setting up a shot, “Feelin’ good then? Then let’s kick ass!”

Fackler’s totally of his Generation Y culture, just don’t mistake his nonchalance for slacker mentality. He’s all about the work. He carved a career out-of-thin-air directing videos for Saddle Creek recording artists. His shorts netted the attention and backing of Altman. He cobbled together casts, crews and sets, often doing every job himself, before Lovely. He hung in there six years waiting for this moment, working at his family’s business, Shirley’s Diner, to pay the bills.

“If there’s ever a roadblock you can always get around it. It’s just a matter of taking the time…and not giving up. I wanted the roadblocks. I was like, Bring ‘em on, because I had a lot of ambition and I still do. I guess it’s just something that I always thought anything is possible. It’s like the naive child in me never left me. I love it. I try to get everyone else around me to feel the same way.”

It was in an L.A. editing room where the jumble of material he shot for Lovely finally came into focus.

“The film from script to screen went through a lot,” he said. “I tried every possible edit. That’s why we ended up editing two months more than we thought we were. But luckily, you know, everyone — producers and investors – were supportive of that process, They didn’t put that much pressure on me because they saw that the film was pretty good, they liked it, and so they allowed us to do it. I ended up throwing the dreams out all together because they weren’t working, and using the experimental lighting scenes because they ended up looking so good.

“I have no regret cutting things I shot. I love the film I have. I love cutting stuff. My philosophy while editing was to not be attached to anything. Once I lived by that rule, everything came free. What matters is making the best film possible, always.”

That mature-beyond-his-years attitude drew Altman to be his mentor. Altman, whose North Sea Films produced Lovely with Knudson and Jay Van Hoy’s Parts and Labor, credits Fackler for hanging in there and doing what’s best for the project, saying: “it’s taken a great deal of patience. Poor Nik, he really does want to see this get released.” Whatever happens, Fackler’s satisfied with what he’s wrought.

“I like to take children’s themes that anyone from any age can understand and then put them in these like really harsh realities of what life can be like. Lovely, Still is very much written to evoke some kind of feeling. It takes place during Christmas time and it deals with family and love. It’s multi-layered. For some people that may be a happy feeling and for others it may be depressing. Art is trying to create a new feeling you’ve never felt before. You watch a film and you leave the film feeling a new way. You may not have a name for the feeling, but it’s new.

“That’s all I can hope for.”

He recently collaborated with cult comic strip-graphic novel artist Tony Millionaire on a script adaptation of Millionaire’s Uncle Gabby. “I can’t wait to bring existentialism and poetry to the children’s film genre,” said Fackler. ”I’m also excited to work with puppetry. It will be like playing with toys! ALL DAY LONG!”

Altman, Knudson and Co. have informal first-look rights on Fackler projects.The same producers who’ve had his back on Lovely look forward to a long association. “Like Dana (Altman), we want to continue working with Nik and we want to create a family sort of, so he feels protected, so he can make the movies he wants to make for the rest of his career,” said Knudson. Radical, man.

Related Articles

- Landau and Burstyn in Lovely, Still Trailer (screenhead.com)

- Canceled FX Boxing Show, ‘Lights Out,’ May Still Springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s Career (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Winners Announced for 2011 Film Independent Spirit Awards (prnewswire.com)

Power Players, Vicki Quaites-Ferris and Other Omaha African-American Community Leaders Try Improvement Through Self-Empowered Networking

| Here is part two of “my” two-part cover story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) on the African-American Empowerment Network. I qualify the ownership of the story in quotation marks because this installment was cut even more severely than the first. again without my having any input into the editing process. It’s all part for the course for how editors and publishers treat the work of freelancers in the Omaha market, some being more sensitive and inclusive to the writer having a part in the editing phase than others. I do not read my published work, and so I cannot say with any certainty that the piece was damaged or mistakes were made in the winnowing, but I am comfortable saying that what was submitted as a 4,000 word story and then having ended up in print at 2,000 words was a compromised piece of work. When the writer has not made that kind of cut himself or herself, than the work is essentially no longer theirs but is the handiwork of the editors. I will soon post my submitted versions of both installments and let you the reader decide which covered the subject more thoroughly. I use the word thorough for a reason, and that’s because my assignment was to research and write a comprehensive story on the Network, and that’s exactly what I did and submitted. Now mind you, like with any project, I only submitted the story (broken into two parts) after much self-editing. But when 7,500 or 8,000 words are then reduced by others down to 4,500 words, well, I can only say that the printed work must bear only a slight resemblance to the original.

Power Players, Vicki Quaites-Ferris and Other Omaha African-American Community Leaders Try Improvement Through Self-Empowered Networking © by Leo Adam Biga As published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) African-American Empowerment Network leaders know the nonprofit must have partners to transform North Omaha. It has reached out to philanthropists, CEOs, social service agency executive directors, pastors, neighborhood association leaders, current or ex-gang members, school administrators, law enforcement officials, city planning professionals, local, county and state elected officials. The Network’s taken a systematic approach to build community consensus around sustainable solutions. North Omaha Contractors Alliance president Preston Love Jr. began as a critic but now champions the Network’s methodical style in gaining broad-based input and support. “My compliment to them is even bigger than most because they stayed by their guns. I highly commend them because they did it the right way in spite of people like myself … They developed a process which has involved every level, from leadership on down to grassroots, for people to participate. That is the key to me.” For Empowerment Network facilitator Willie Barney, it’s all about making connections. “When we started there were not enough forums and venues for people to come together and share ideas and solutions in an environment where you felt comfortable no matter who you were,” he said. “ …. Now we’re to a point where we’re working with residents at planning meetings, trying to get as many people as we can involved to tell us what is their vision for the targeted areas — what does it look like in north Omaha, what does it look like for African-Americans in the city, what would they like to see. ” He refers to North Omaha Village Zone meetings at North High that invite community members to weigh in on developing plans for the: 24th and Lake, 16th and Cuming, 30th and Parker/Lake and Adams Park, Malcolm X and Miami Heights neighborhoods. Some 100 residents attended a May 27th meeting. A homeowner who lives in the Adams Park area said she’s interested in how development will affect her home’s resale value and improve quality of life. “I’m very concerned about my investment, so anything that’s going on we want to know because it will eventually impact us,” said Thalia McElroy, who was there with her husband Greg. Greg McElroy said he appreciates residents having a say in plans at the front end rather than the back end. Wallace Stokes, who just moved here from Waterloo, Iowa with his small construction business, likes what’s he’s seen and heard. “They’re trying to empower the neighborhood and create jobs and also make it better for everybody else. All of that’s what I believe in.” Bankers Trust vice president Kraig Williams has lived and worked all over America. “I can honestly say I’ve never seen this happen before. I think there is a sincere invitation for people to experience this and to be a part of it, and the invitation is actually coming from the Empowerment Network. This appears to be something that’s got the appropriate amount of focus. City government’s there, a lot of the commercial companies are involved as well.” While confident the Network “will continue to push forward for change,” Williams said sustainability depends on the “other parties at the table” and how the economy affects their budgets and bottom lines. A segment missing from the leadership is age 30-and-unders. That’s why Dennis Anderson and others created the Emerging Leaders Empowerment Network. “We want to be heard at the table as well,” said Anderson, who has his own real estate business. “We have our own ideas and our own solutions we want to bring forward.” He said ideas generated by Emerging Leaders are presented to the larger Network. “Now we are being heard. They have been extremely supportive of us,” he said. What makes the Network different beyond its covenant calling for African-Americans to harness change through self-empowerment? “I don’t see any other kind of a way and I don’t see any other time that this has happened,” said Family Housing Advisory Services director Teresa Hunter, co-chair of the Network’s housing development covenant. “There has not been the kind of movement like this in our community in a very long time. There have been attempts at it, and I have been a part of those attempts to bring community together, but the structure currently in place is a structure that has not been there before,” said Omaha City Councilman Ben Gray, chair of the violence intervention-prevention strategy. Davis Companies CEO Dick Davis, who heads the economics covenant and a newly formed Economic Strategy Taskforce, said the Network represents a fresh approach to economic development. “The principles we set up are a market-driven merit-based economic model as opposed to the social justice, social equity models Omaha has been doing.” Proposed development projects up for review before the Taskforce or its eight sub-taskforces, he said, are held to a rigorous set of “expectations and outcomes” to select sustainable initiatives. He said Taskforce members, who include elected and appointed public officials, are working to change public policies to “open up more contract, procurement opportunities” for African-Americans. Buttressing the Taskforce’s and the Network’s economic models, said Davis, “are substantial amounts of dollars I’m committing.” He’s living the “do my part” mantra of the Empowerment covenant by, among other things, constructing a new headquarters building for the Davis Cos. in NoDo, investing $10,000 in seed money in each of 10 small black-owned businesses over a decade’s time. He’s on his third one. His Chambers-Davis Scholarship Program and Foundation for Human Development are some of his other philanthropic efforts. Davis uses his own generosity as calling card and challenge. “I go to white folks and black folks and say, ‘OK, here’s how I’m stepping up, tell me how you’re going to step up? How you going to do your part?’ That doesn’t mean necessarily just by money, it’s by expertise, it’s by commitment, it’s by whatever the case may be. But once you step up I want you to be accountable for it, I don’t want you to say it’s somebody else’s fault.” The idea is that as others put up personal stakes, assume vested interests and make commitments, African-Americans gain leverage in the marketplace. For Davis, the promise of the Network is its transformational potential. “If I’m going to dedicate the rest of my life to see if we can develop benefits for African-Americans in Omaha …. what I want to see is a cultural change, a value change, a behavioral change of African-Americans’ psyche toward economics.” He will at least keep people talking. “One of my gifts is I can bring a group of people together that in most cases don’t talk to each other. The social justice advocates don’t talk to the pro business advocates, Republicans don’t talk to Democrats, white folks don’t talk to black folks, and we don’t get anything done.” If the Network’s done nothing else, he said, it’s brought diverse people together. “It’s called shared responsibility, shared accountability — that’s what makes it feel different.” “A strength of the Network is that disagreements unfold in private, behind closed doors, not for public display,” said Rev. Jeremiah McGhee, co-chair of the faith covenant. Where the confrontational outcry of passionate citizens tends to “fizzle out,” he said the Network’s moderate, conciliatory approach is built for “the long haul. We’re not just a flash in the pan. We’re being very deliberate about this.” Network members say a confluence of new leadership, including Gray, Davis and Black, seemed to make the time right for a concerted effort to improve the African-American Omaha. “It was a formation, kind of a like a call to the troops to come together,” said Empowerment operations director Vicki Quaites-Ferris, who came from the Mayor’s Office The Network’s been slow to put itself in the media spotlight because it prefers a behind-the-scenes role and because it’s sensitive to past disappointments. “There’s always been a hesitation,” said Willie Barney. “We see so many groups come before the camera and make grand announcements about what they’re going to do and how they’re going to do it and for whatever reason we don’t see them again, and the community gets really tired of that.” Preston Love Jr. wants African-Americans involved from planning to financing, bonding and insurance, through construction, ownership, management and staffing. Leo Louis takes issue with something else. “If the idea is to empower the community then the community should be growing,” he said, “not the Network. What I’m seeing happening is the Network growing and the community falling further and further down with rising drop out, STD, homicide rates. Yes, there’s more people getting involved, more marketing, more funds going towards the Network and organizations affiliated with the Network, but the community’s not getting any better.” Tangible change is envisioned in Network designated neighborhood-village strategy areas. The plan is to apply the strategic covenants within defined boundaries and chart the results for potential replication elsewhere. One strategic target area includes Carter’s Highlander Association, the Urban League, Salem Baptist Church and the Charles Drew Health Center. The strategy there started small, with prayer walks, block parties, neighborhood cleanups. It’s continued through discussions with neighborhood associations. Brick-and-mortar projects are on tap. “We’ve received some financial support to take the strategy to the next level,” said Barney. “We’re really focused on housing development, working with residents to look at housing needs. We’re partnering with Habitat for Humanity, NCDC, OEDC, Holy Name, Family Housing Advisory Services. Our goal is that you’ll be able to drive through this 15-block area and begin to see physical transformation. That’s where we’re headed.” The Network also works with Alliance Building Communities and the Nebraska Investment Finance Authority. Some major housing developments are ready to launch. Another target area includes 24th and Lake. The Network’s plans for redevelopment there jive closely with those of a key partner, the North Omaha Development Project. As the Network matures, its profile increases. Barney doesn’t care if people recognize the Network as a change agent so long as they participate. “They may not know what to call it but they know there’s something positive going on,” he said. “They know we get things done. The message is spreading. We’ve had a lot of opportunities to go and present. There’s definitely more interest. We can tell by the volume of calls we get and the number of visitors to our web site (empoweromaha.com).” In terms of accountability, Barney said, “the leaders hold the leaders accountable and we invite the community in every second Saturday to an open meeting. They can come in, look at what’s going on. There’s nothing hidden, it’s up on the (video) screen. They have the chance to redirect, ask questions. It’s an open environment.” McGhee said the leadership “is really holding our feet to the fire” for transparency and responsibility. Where could it go wrong? Preston Love cautions if the Network becomes “the gatekeeper” for major funds “that gives them power that, if wrongly used,” he said, “could work against the community.” Carter said letting politics get in the way could sabotage efforts. McGhee said public “bickering” could turn people off. He said the leadership has talked about what-if scenarios, such as a scandal, and he said “there’s no question” anyone embroiled in “something counter-productive like that would need to step down.” Former Omaha minister Rev. Larry Menyweather-Woods worries about history repeating itself and a community’s hopes being dashed should the effort fade away. “You’d go back to square one,” he said. He wonders what might happen if things go off course and the majority power base “turns against you.” “When all hell breaks loose,” he said, “who from the Network will go to the very powers they’ve made relationships with and say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, this isn’t right?’” He suggests only a pastor has “nerve enough to do that.” And that may be the Network’s saving grace — that pastors and churches and congregations are part of this communal mission. “The history of African-Americans has been founded on faith and the church, so it’s the primary thing and everything else kind of grows out of that,” said Pastor Bachus. “Faith is that hub and the covenants and the efforts really are spokes out of that hub, and that’s the thing that holds it together.” |

Related Articles

- Economic Setbacks, Empowerment Challenges, and a Still-Evolving Multicultural Nation Result in Deferred Dreams Among African-American and Hispanic Consumers, New Yankelovich Multicultural Study Finds (prnewswire.com)

- From Motown to Growtown: The greening of Detroit (grist.org)

- Black church: Place of empowerment (cnn.com)

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Keeping the Dream Alive: President Obama’s Work with the African American Community (whitehouse.gov)

- Today’s Exploration: Omaha’s History of Racial Tension (theprideofnebraska.blogspot.com)

‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ Movie for the Ages from Book for All Time

Like a lot of people, To Kill a Mockingbird is one one of my favorite books and movies. Has there ever been a more truthful evocation of childhood and the South? When Bruce Crawford organized a revival screening of the film a couple years ago I leapt at the chance to write about it and the following article is the result. It was originally published in the City Weekly. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the first printing of the masterpiece novel by Harper Lee. The film is fast creeping up on its own 50th anniversary. The book to film adaptation is arguably the best screen treatment of a great novel in cinema history. That transition from one medium to another is often not a happy or satisfying one. Owing to my quite foggy memory of childhood things, I must admit that I cannot be entirely certain I have read Lee’s novel, but then again it was already standard fare in schools and so my unreliable recollection that I did read it in high school is probably accurate. I really should get a copy of the book, sit down with it, and indulge in that precisely drawn world of Lee’s. I am sure I will be as carried away by it now as I still I am by the film, which I have seen in its entirety a few dozen times, never tiring of it, always moved by it, and whenever I find it playing on TV I cannot help but watch awhile. It is that mesmerizing to me. And I know I am hardly alone in its effect.

For the article I got the chance to interview Mary Badham, who plays Scout in the film. At the end of my article’s posting, you’ll find a Q & A I did with her. Around this same time I also had the opportunity to interview Robert Duvall, who so memorably plays Boo Radley. However, I spoke to Duvall for an entirely different project, and I never brought up Mockingbird with him, although I wish I did.

‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ Movie for the Ages from Book for All Time

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the City Weekly

Great movies are rarely made from great books. If you buy that conventional wisdom than an exception is the 1962 movie masterpiece To Kill a Mockingbird. Harper Lee’s best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning novel became an award-winning film acclaimed for how faithfully and lovingly it brought her work to the screen. Lee publicly praised the adaptation.

Gregory Peck, with whom Lee maintained a friendship. won the Academy Award as Best Actor for his starring turn as idealistic small town Southern lawyer Atticus Finch. Atticus is a widower with two precocious children — Scout and Jem. Atticus was based in part on Lee’s own father, an attorney and newspaper editor. Peck’s understated performance forever fixed the Mount Rushmoresque actor as the epitome of high character and strong conviction in movie fans’ minds.

Omaha impresario and film historian Bruce Crawford will celebrate Mockingbird on Friday, Nov. 14 at the Joslyn Art Museum with a 7 p.m. screening and an appearance by Mary Badham, the then-child actress who played Scout. She’s the rambunctious young tomboy through whose eyes and words the story unfolds. Actress Kim Stanley provided the voice of the adult Scout, who narrates the tale with ironic, bemused detachment.

Badham earned a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination in her film debut yet largely retired from screen acting after only two more roles. She remained close to Peck until his death a few years ago. The Richmond, Vir. area resident often travels to Mockingbird revivals. There’s always a big crowd. The universal appeal, Crawford said, lies in the pic tapping childhood feelings we all identify with.

“The crossover appeal of this film is unlike that of but a very few pictures,” he said. That pull can be attributed in part to the book, which, Crawford said, “has an absolutely enormous following in literary circles. It’s like required reading in public schools across the United States. Then, on top of that, the film was an instant classic when it came out and has done nothing but even grow larger in status the last 46 years. It’s become one of the most beloved films of all time.”

American Film Institute pollsconsistently rank Mockingbird as a stand-the-test-of- time classic. Crawford said seldom does an enormously popular book turn into an equally popular film. “It’s like Gone with the Wind in that,” he added.

Lee’s elegiac narrative, set in the 1930s Alabama she grew up in, has a kind of nostalgic, fairy tale quality the film enhances at every turn. It starts with the memorable opening credit sequence. An overhead camera peers with warm curiosity at a young girl sorting through an assortment of trinkets spilled from a cigar box, each an artifact of childhood discovery and reverie. As she hums, she draws with a crayon on paper. Soon, the film’s title is revealed.

The camera, now in closeup, pans from one small object to another, all in harmony with the wistful, lyrical music score. It makes an idyllic scene of childhood bliss. The girl then draws a crude mockingbird on paper and without warning rips it apart, presaging the abrupt, ugly turn of events to envelop the children in the story. It’s a warning that tranquil beauty can be stolen, violated, interrupted.

Dream-like imagery and music emphasize this is the remembered past of a woman seeing these events through the prism of impressionable, preadolescent memories. The film captures the sense of wonder and danger children’s imaginations find in the most ordinary things — the creak and clang of an old clapboard house in the wind, shadows lurking in the twilight, a tree mysteriously adorned with gifts.

Like another great movie from that era, The Night of the Hunter, Mockingbird gives heightened, elemental expression to the world of children in peril. The by-turns chiaroscuro, melancholy, sublime, ethereal landscape reflects Scout’s deepest feelings-longings. It is naturalism and expressionism raised to high art.

The film tenderly, authentically presents the relationship between Scout and her older brother Jem, her champion, and the bond they share with their father. The motherless children are raised by Atticus the best he knows how, with help from housekeeper Calpurnia and nearby matron Miss Maudie. A sense of loss and loneliness but moreover, love, infuses the household.

A mythic, largely unseen presence is Boo Radley, a recluse the kids fear, yet feel connected to. He leaves tokens for them in the knot of a tree and performs other small kindnesses they misinterpret as menace. In the naivete and cruelty of youth, Scout and Jem make him the embodiment of the bogeyman.

The figure looming largest in the children’s lives is Atticus, a seemingly meek, ineffectual man whose gentle, principled virtues Scout and Jem begin to admire. His unpopular stand against injustice and bigotry quells, at least for a time, violence. His strength and resolve impress even his boy and girl.

Trouble brews when Atticus defends Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman in an era of lynchings. The case makes the family targets. The children witness Atticus’s noble if futile defense and come to appreciate his goodness and the esteem in which he’s held. In their/our eyes he’s a hero.

In his summation Atticus appeals to the all-male, all-white jury: “Now gentlemen, in this country our courts are the great levelers, and in our courts all men are created equal. I’m no idealist to believe firmly in the integrity of our courts and of our jury system. That’s no ideal to me. That is a living, working reality. Now I am confident that you gentlemen will review without passion the evidence that you have heard, come to a decision, and restore this man to his family. In the name of God, do your duty. In the name of God, believe Tom Robinson.”

The film’s theme of compassion is expressed in some moving moments. Atticus says to Scout, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… ’till you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.”

When a school chum Scout’s invited for dinner drenches his meal in syrup, her mocking comments embarrass him, prompting Calpurnia to scold her for being rude. The lesson: respect people’s differences.

Before Atticus will even consider getting a rifle for Jem he relates a story his own father told him about never killing a mockingbird. It’s a father instructing his son to never harm or injure a living thing, especially those that are innocent and give beauty. In the context of the plot, the children, Boo Radley and Tom Robinson are the symbolic mockingbirds. Atticus delivers this lesson to his son:

“I remember when my daddy gave me that gun…He said that sooner or later he supposed the temptation to go after birds would be too much, and that I could shoot all the blue jays I wanted, if I could hit ’em, but to remember it was a sin to kill a mockingbird. Well, I reckon because mockingbirds don’t do anything but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat people’s gardens, don’t nest in the corncrib, they don’t do one thing but just sing their hearts out for us.”

Among many famous scenes, Scout’s innocence and decency shame grown men bent on malice to heed their better natures. In another, Atticus tells Jem he can’t protect him from every ugly thing. When evil does catch up to the children their savior is an unlikely friend, someone who’s been watching over them all along, like a guardian angel. Once safely returned to the bosom of home and family, they find refuge again in their quiet, unassuming hero, who comforts and reassures them.

Only the most sensitive treatment could capture the rich, delicate rhythms and potent themes of Lee’s novel and this film succeeds by striking a well-modulated balance between bittersweet sentimentality and searing psychological drama.

Although the book was a smash, it took courage byUniversal to greenlight the project developed by producer Alan J. Pakula and director Robert Mulligan. Creative partners in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, Pakula and Mulligan had made Fear Strikes Out but the young filmmakers were still far from being a power duo. After Fear Mulligan helmed a few more studio hits without Pakula but nothing that suggested the depth Mockingbird would demand. His less than inspiring work might have given any studio pause in taking on the book, whose powerful indictment of prejudice and impassioned call for tolerance came at a time of racial tension. Yes, the civil rights movement was in full flower but so was resistance to it in many quarters.

Efforts to ban the book from schools — on the grounds its portrayal of racism and rape are harmful — have cropped up periodically during its lifetime.

The socially conscious filmmakers helped their cause by signing Peck, who was made to play Atticus Finch, and by enlisting Horton Foote, a playwright from the Tennesse Williams school of Southern Gothic drama, who was made to adapt Lee’s book. Foote’s Oscar-winning script is not only true to Lee’s work but elevates it to cinematic poetry with the aid of Mulligan’s insightful direction, Pakula’s sensitive input, Russell Harlan’s moody photography, Elmer Bernstein’s poignant score and Henry Bumstead and Alexander Golitzen’s evocative, Oscar-winning art direction.

Pakula-Mulligan went on to make four more pictures together, including Love with the Proper Stranger and Baby, the Rain Must Fall with Steve McQueen and The Stalking Moon with Peck. The two split when Pakula left to pursue his own career as a director. Pakula soon established himself with Klute and All the President’s Men. Mulligan’s career continued in fine form, including his direction of two more coming-of-age classics — Summer of ‘42 and The Man in the Moon.

Mockingbird was Lee’s first and only novel. Not long after completing the book she accompanied childhood chum Truman Capote (the character of Dill in Mockingbird is based on him) to Holcomb, Kan. for his initial research on what would become his nonfiction novel masterwork, In Cold Blood. Lee, mostly retired from public life these days, is said to divide her time between New York and Alabama.

The part of Atticus Finch came to Peck at the height of his middle-aged superstardom. He’d proven himself in every major genre. And while he acted on screen another 30-plus years, the film/role represented the peak of his career. It was the kind of unqualified success that could hardly be repeated, certainly not topped. He didn’t seem to mind, either. He gracefully aged on screen, playing a wide variety of parts. But his definitive interpretation of Atticus Finch would always define him as a man of conscience. It became his signature role.

Peck was among the last of a breed of personalities whose ability to project noble character traits infused their performances. Like Spencer Tracy, Henry Fonda, John Wayne and Charlton Heston, Peck embodied the stalwart man of integrity.

“Those types of characterizations just don’t really exist anymore. That’s what draws people to these characters and to the performances of these men because their like will never be seen again, and we know it” said Crawford.

Mary Badham then

A Q & A with Mary Badham, the Actress Who Played Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird

©by Leo Adam Biga

Actress Mary Badham recently spoke by phone with City Weekly correspondent Leo Adam Biga about her role of a lifetime as Scout in the 1982 film classic To Kill a Mockingbird. She grew up in Birmingham, Ala., near the hometown of Harper Lee, upon whose noted novel the film is based. Badham spoke with Biga from her home near Richmond, Virginia.

LAB: “To Kill a Mockingbird is such a touchstone film for so many folks.”

MB: “Mockingbird is one of the great films I think because it talks about so many things that are still pertinent today. So many of life’s lessons are included in the story of Mockingbird, whether you want to talk about family matters or social issues or racial issues or legal issues, it’s all there. There’s many topics of discussion.”

LAB: “Had you read the book prior to getting cast in the film?”

MB: “No, had not read the book.

LAB: “So was reading it a mandatory part of your preparation?”

MB: “No, not at all. I don’t even know that I got a full script.”

LAB: “When did you first read the book then?”

MB: “Ah, that was not till much later I’m embarrassed to say. Not until after I had my daughter. And how it all started was professor Inge from our local college asked me to come speak to his English lit class. We met for lunch and almost the first words out of his mouth were, ‘So what was your favorite chapter in the book?’ He knew by the look on my face that I hadn’t read the book. He said, ‘Young lady, your first assignment is you go home and read the book before you come to my class.’ In defense of myself, I didn’t want to read the book. Because I had everything I wanted out of the story up there on the screen. You know how sometimes you see a film and then you read the book and it messes up that whole warm and fuzzy feeling you may have had about something? But it was really great for me because it filled in a lot of these gaps I had with the story. It just gave me a much fuller love and appreciation for it. And it’s so beautifully written. It’s just so perfect.

“It’s a little book. It’s a quick one-night read, and a lot of people want to put it down for that, because it’s simple…but to me its one of the greatest pieces of literature ever written, and it’s borne out by the way it’s read. It’s the second most-read book next to the Bible. That’s saying something.”

LAB: “I know that you and Peck, whom you always called Atticus, enjoyed a warm relationship that lasted until death. On the shoot did he do things to foster your father-daughter relationship on screen?”

MB: “Oh, absolutely. I’d go over there and play with his kids on the weekends. We would have meals together and do things together. So, yeah, they encouraged that bonding. I had such a strong relationship with my own father, and I missed him dreadfully because Daddy had to stay at home to take care of things… My mom came out. But I missed that male link of family and so Atticus really filled the bill. He was just amazing. What a great father. I mean, he was one of the best I think. Not that he was perfect. But he was so well read and so patient, I think you would have to say. And just full of laughter…

“He and PhillipAlford (Jem) used to play chess together. They had such a beautiful relationship, and that stayed till the very end. They just got along so well together and Phillip would always know how to make him laugh. Phillip’s such an entertainer. He’s got a brilliant, quick sense of humor and Atticus really appreciated that. He just adored Phillip. So we really became a family.

“It was nothing for me to pick up the phone and he’d be on the other end, ‘What ya doin’ kiddo?,’ which was marvelous because I lost my parents so early. My mom died three weeks after I graduated from high school and my died died two years after I got married. And I didn’t have grandparents — they died before I was born. I felt totally cut off. So, you know. Atticus really came through psychologically. He really was my male role model. He and Brock Peters (Tom Robinson).

“It was marvelous because those guys were so intelligent and loving and outgoing, and supportive of anything I wanted to do. And sometimes life was not easy growing up and when you’re worried about what’s going to happen next in life, sometimes just hearing those voices on the other end of the line calling to check on me was

just so uplifting. That was just amazingly supportive”

Mary Badham today

LAB: “I understand you two would visit each other as circumstances allowed.”

MB: “Whenever he’d be nearby or if I was out there or whatever, then we would see other. And usually when you make a film, you know, it’s like, ‘Oh, we gotta get together afterwards’ and stuff, and it never happens. But with this cast and crew we did keep up with each other through the years. Paul Fix (the judge), I stayed really tight with right up until he passed. Collin Wilcox (Mayella Ewell) — we stayed in touch up until recently. I would see William (Windom), who played the prosecuting attorney, at various events and things. He’s gone now. So is Alan Pakula, our producer. Absolutely one of the most loving, dear, intelligent human beings I’ve ever met.”

LAB: “Most everyone’s gone except for you, Phillip, Robert Duvall. Bob Mulligan…”

MB: “To lose these guys so early has just about killed me because I feel like my support pillars are gone. I really relied on them – just knowing they were there and that I could pick up the phone and talk to them or they could call me and check on me. That’s a real shot in the arm in your day.”

LAB: Pakula became a great director in his own right. I’m curious about his and Mulligan’s collaboration. They were quite a team. I assume Pakula was a very hands-on, creative producer who worked in close tandem with Mulligan on the set?”

MB: “I think so.”

LAB: “So how did you come to play Scout in the first place?”

MB: “It happened because my mom had been an actress with the local Town and Gown Theatre (in Birmingham, Ala.) She had done some acting in England. That’s where my mom was from. She was the leading lady for a lot of years in the Town and Gown. So when the movie talent scout issued this cattle call our little theater was on the list. They were looking for children. Jimmy Hatcher, who ran the theater, naturally called my mom and said, ‘Bring her down.’ Then mom had to go to Daddy and get permission and he said, ‘No.’ And she said, ‘Now, Henry, what are the chances the child’s going to get the part anyway?’ Oh, well…”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Mary Badham’s late brother, John Badham, acted at the Town and Gown. He became a successful film director. Phillip Alford acted in three shows there before cast as Jem. The theater’s where Patricia Neal got her acting start.

LAB: “Lo and behold you did get the part.”

MB: “Daddy was horrified and it was everything Alan Pakula and Buddy Boatwright, the talent scout, could do to try and convince him that they were not going to ruin his daughter.”

LAB: “Everything you’ve said suggests Mockingbird being a very warm set.”

MB: “It was. I remember a lot of laughter, a lot of joking around. I remember five months of having a blast. I didn’t want it to end. I had not had any trouble with my lines until like the last day, and then it was just like, ‘Oh, God, I’m going to say goodbye to all these people.’ I was so upset I could not spit my lines out for anything. My mother finally said, ‘Do you know what the freeway is like at 5 o’clock? These people have got to go home.’ I was like, ‘OK, OK.’ So I got out there and did it. But it broke my heart. I thought I’d never see these people again.”

LAB: You and Phillip were newcomers. Did the crew take a kids-gloves approach?”

MB: “Yes, we had time to get used to the cameras and the crew and the lights and getting set up. They started off very slowly with us. The camera and crew would be across the street and then they’d move up a little closer, and then a little closer still, and then they were right there. Everything was kind of good that way.”

LAB: “How did director Bob Mulligan work with you two?”

MB: “Very gentle, very tender. Instead of standing there and looking down on us he would squat and talk to us…right down on our level. He didn’t tell us really how to do the scenes. It was more, ‘OK, you’re going to start from here and we need you to move here…’ He let us do the scene and then he would tweak it, so that he would get the most natural response possible, and I think that’s brilliant. We were never allowed to talk to an actor out of costume (on set). They were just there the day we had to work with them and then they were that person they were playing. Bob did these things to get the most out of us nonactors.”

LAB: “You and Phillip were thrust into this strange world of lights-cameras.”

MB: “Now, I was used to having a camera stuck in my face from the time I was born because I was my father’s first little girl. He’d had all these ratty boys and then he finally got his dream with me when he was 60 years old. That was back in the days when flash cameras had the light bulbs that would pop and the home movie cameras needed a bank of lights. So, yeah, I grew up with all of that. Phillip and I grew up four blocks from one another. But we would never have met

because I was in private school — he was in public school. He was 13. I was only 9.”

LAB: “There’s such truth in all the performances.”

MB: “I think our backgrounds helped in that a lot, because Atticus (Peck) was from a small town in Calif. (La Jolla) that looked very much like that little village (in Mockingbird). He knew that period well. And for Phillip and I nothing much had changed in Birmingham, Ala. from the 1930s to the 1960s. All the same social rules were in place. Women did not go out of the house unless their hair was done and they had their hats and gloves on. Servants and children were to be seen and not heart. Black people still rode on the back of the bus. And there were lynchings on certain roads you knew you couldn’t go down. There were still colored and white drinking fountains when I was growing up. So all of that was just totally normal for us. There’s no way you could have explained that to a child from Los Angeles. They wouldn’t have known how to react to all that stuff. My next door neighbor (during the shoot in Calif.) was this black man with a beautiful blond bombshell wife and two gorgeous kids, and down the road was an Oriental family, and we visited — went to dinner at their house. We could never do that in Alabama. It just would not happen.”

Related Articles

- To Kill a Mockingbird Turns 50 (austinist.com)

- ‘To Kill A Mockingbird’ Anniversary: Anna Quindlen On The Greatness Of Scout (huffingtonpost.com)

- 51 reviews of To Kill a Mockingbird (rateitall.com)

- Great Characters: Atticus Finch (“To Kill a Mockingbird”) (gointothestory.com)

- Films For Father’s Day (npr.org)

- Harper Lee – We Hardly Know Ye (pspostscript.wordpress.com)

Bob Gibson, the Master of the Mound remains his own man years removed from the diamond (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Omaha’s bevy of black sports legends has only recently begun to get their due here. With the inception of the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame a few years ago, more deserving recognition has been accorded these many standouts from the past, some of whom are legends with a small “l” and some of whom are full-blown legends with a capital “L.” As a journalist I’ve done my part bringing to light the stories of some of these individuals. The following story is about someone who is a Legend by any standard, Bob Gibson. This is the third Gibson story I’ve posted to this blog site, and in some ways it’s my favorite. When you’re reading it, keep in mind it was written and published 13 years ago. The piece appeared in the New Horizons and I’m republishing it here to coincide with the newest crop of inductees in the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame. Gibson was fittingly inducted in that Hall’s inaugural class, as he is arguably the greatest sports legend, bar none, ever to come out of Nebraska.

Bob Gibson, the Master of the Mound remains his own man years removed from the diamond (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Orignally published in the New Horizons

Bob Gibson. Merely mentioning the Hall of Fame pitcher’s name makes veteran big league baseball fans nostalgic for the gritty style of play that characterized his era. An era before arbitration, Astro-Turf, indoor stadiums and the Designated Hitter. Before the brushback was taboo and going the distance a rarity.

No one personified that brand of ball better than Gibson, whose gladiator approach to the game was hewn on the playing fields of Omaha and became the stuff of legend in a spectacular career (1959-1975) with the St. Louis Cardinals. A baseball purist, Gibson disdains changes made to the game that promote more offense. He favors raising the mound and expanding the strike zone. Then again, he’s an ex-pitcher.

Gibson was an iron man among iron men – completing more than half his career starts. The superb all-around athlete, who starred in baseball and basketball at Tech High and Creighton University, fielded his position with great skill, ran the bases well and hit better than many middle infielders. He had a gruff efficiency and gutsy intensity that, combined with his tremendous fastball, wicked slider and expert control, made him a winner.

Even the best hitters never got comfortable facing him. He rarely spoke or showed emotion on the mound and aggressively backed batters off the plate by throwing inside. As a result, a mystique built-up around him that gave him an extra added edge. A mystique that’s stuck ever since.

Now 61, and decades removed from reigning as baseball’s ultimate competitor, premier power pitcher and most intimidating presence, he still possesses a strong, stoic, stubborn bearing that commands respect. One can only imagine what it felt like up to bat with him bearing down on you.

As hard as he was on the field, he could be hell to deal with off it too, particularly with reporters after a loss. This rather shy man has closely, sometimes brusquely, guarded his privacy. The last few years, though, have seen him soften some and open up more. In his 1994 autobiography “Stranger to the Game” he candidly reviewed his life and career.

More recently, he’s promoted the Bob Gibson All-Star Classic – a charitable golf tournament teeing off June 14 at the Quarry Oaks course near Mahoney State Park. Golfers have shelled out big bucks to play a round with Gibson and fellow sports idols Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Sandy Koufax, Whitey Ford, Lou Brock and Oscar Robertson as well as Nebraska’s own Bob Boozer, Ron Boone and Gale Sayers and many others. Proceeds will benefit two causes dear to Gibson – the American Lung Association of Nebraska and BAT – the Baseball Assistance Team.

When Gibson announced the event many were surprised to learn he still resides here. He and his wife Wendy and their son Christopher, 12, live in a spacious home in Bellevue’s Fontenelle Hills.

His return to the public arena comes, appropriately enough, in the 50th anniversary season of the late Jackie Robinson’s breaking of Major League Baseball’s color barrier. Growing up in Omaha’s Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects, Gibson idolized Robinson. “Oh, man, he was a hero,” he told the New Horizons. “When Jackie broke in, I was just a kid. He means even more now than he did then, because I understand more about what he did” and endured. When Gibson was at the peak of his career, he met Robinson at a Washington, D.C. fundraiser, and recalls feeling a deep sense of “respect” for the man who paved the way for him and other African-Americans in professional athletics.

In a recent interview at an Omaha eatery Gibson displayed the same pointedness as his book. On a visit to his home he revealed a charming Midwestern modesty around the recreation room’s museum-quality display of plaques and trophies celebrating his storied baseball feats.

His most cherished prize is the 1968 National League Most Valuable Player Award. “That’s special,” he said. “Winning it was quite an honor because pitchers don’t usually win the MVP. Some pitchers have won it since I did, but I don’t know that a pitcher will ever win it again. There’s been some controversy whether pitchers should be eligible for the MVP or should be limited to the Cy Young.” For his unparalleled dominance in ‘68 – the Year of the Pitcher – he added the Cy Young to the MVP in a season in which he posted 22 wins, 13 shutouts and the lowest ERA (1.12) in modern baseball history. He won the ‘70 Cy Young too.

Despite his accolades, his clutch World Series performances (twice leading the Cardinals to the title) and his gaudy career marks of 251 wins, 56 shutouts and 3,117 strikeouts, he’s been able to leave the game and the glory behind. He said looking back at his playing days is almost like watching movie images of someone else. Of someone he used to be.

“That was another life,” he said. “I am proud of what I’ve done, but I spend very little time thinking about yesteryear. I don’t live in the past that much. That’s just not me. I pretty much live in the present, and, you know, I have a long way to go, hopefully, from this point on.”

Since ending his playing days in ‘75, Gibson’s been a baseball nomad, serving as pitching coach for the New York Mets in ‘81 and for the Atlanta Braves from ‘82 to ‘84, each time under Joe Torre, the current Yankee manager who is a close friend and former Cardinals teammate. He’s also worked as a baseball commentator for ABC and ESPN. After being away from the game awhile, he was brought back by the Cardinals in ‘95 as bullpen coach. Since ‘96 he’s served as a special instructor for the club during spring training, working four to six weeks with its talented young pitching corps, including former Creighton star Alan Benes, who’s credited Gibson with speeding his development.

Who does he like among today’s crop of pitchers? “There’s a lot of guys I like. Randy Johnson. Roger Clemens. The Cardinals have a few good young guys. And of course, Atlanta’s got three of the best.”

Could he have succeeded in today’s game? “I’d like to think so,” he said confidently.

He also performs PR functions for the club. “I go back several times to St. Louis when they have special events. You go up to the owners’ box and you have a couple cocktails and shake hands and be very pleasant…and grit your teeth,” he said. “Not really. Years ago it would have been very tough for me, but now that I’ve been so removed from the game and I’ve got more mellow as I’ve gotten older, the easier the schmoozing becomes.”

His notorious frankness helps explain why he’s not been interested in managing. He admits he would have trouble keeping his cool with reporters second-guessing his every move. “Why should I have to find excuses for something that probably doesn’t need an excuse? I don’t think I could handle that very well I’m afraid. No, I don’t want to be a manager. I think the door would be closed to me anyway because of the way I am – blunt, yes, definitely. I don’t know any other way.”

Still, he added, “You never say never. I said I wasn’t going to coach before too, and I did.” He doesn’t rule out a return to the broadcast booth or to a full-time coaching position, adding: “These are all hypothetical things. Until you’re really offered a job and sit down and discuss it with somebody, you can surmise anything you want. But you never know.”

He feels his outspokenness off the field and fierceness on it cost him opportunities in and out of baseball: “I guess there’s probably some negative things that have happened as a result of that, but that really doesn’t concern me that much.”

He believes he’s been misunderstood by the press, which has often portrayed him as a surly, angry man. “

When I performed, anger had nothing to do with it. I went out there to win. It was strictly business with me. If you’re going to have all these ideas about me being this ogre, then that’s your problem. I don’t think I need to go up and explain everything to you. Now, if you want to bother to sit down and talk with me and find out for yourself, then fine…”

Those close to him do care to set the record straight, though. Rodney Wead, a close friend of 52 years, feels Gibson’s occasional wariness and curtness stem, in part, from an innate reserve.

“He’s shy. And therefore he protects himself by being sometimes abrupt, but it’s only that he’s always so focused,” said Wead, a former Omaha social services director who’s now president and CEO of Grace Hill Neighborhood Services in St. Louis.

Indeed, Gibson attributes much of his pitching success to his fabled powers of concentration, which allowed him “to focus and block out everything else going on around me.” It’s a quality others have noted in him outside sports.

“Mentally, he’s so disciplined,” said Countryside Village owner Larry Myers, a former business partner. “He has this ability to focus on the task at hand and devote his complete energy to that task.”

If Gibson is sometimes standoffish, Wead said, it’s understandable: “He’s been hurt so many times, man. We’ve had some real, almost teary moments together when he’s reflected on some of the stuff he wished could of happened in Omaha and St. Louis.” Wead refers to Gibson’s frustration upon retiring as a player and finding few employment-investment opportunities open to him. Gibson is sure race was a factor. And while he went on to various career-business ventures, he saw former teammates find permanent niches within the game when he didn’t. He also waited in vain for a long-promised Anheuser-Busch beer distributorship from former Cardinals owner, the late August Busch. He doesn’t dwell on the disappointments in interviews, but devotes pages to them in his book.

Gibson’s long been outspoken about racial injustice. When he first joined the Cardinals at its spring training facility in St. Petersburg, Fla., black and white teammates slept and ate separately. A three-week stay with the Cardinals’ Columbus, Ga. farm team felt like “a lifetime,” he said, adding, “I’ve tried to erase that, but I remember it like it was yesterday.” He, along with black teammates Bill White and the late Curt Flood, staged a mini-Civil Rights movement within the organization – and conditions improved.

He’s dismayed the media now singles out baseball for a lack of blacks in managerial posts when the game merely mirrors society as a whole. “Baseball has made a lot more strides than most facets of our lives,” he said. “Have things changed in baseball? Yes. Have things changed everywhere else? Yes. Does there need to be a lot more improvement? Yes. Some of the problems we faced when Jackie Robinson broke in and when I broke in 10 years later don’t exist, but then a lot of them still do.”

He’s somewhat heartened by acting baseball commissioner Bud Selig’s recent pledge to hire more minorities in administrative roles. “I’m always encouraged by some statements like that, yeah. I’d like to wait and see what happens. Saying it and doing it is two different things.”

He’s also encouraged by golfer Tiger Woods’ recent Masters’ victory.“What’s really great about him being black is that it seems to me white America is always looking for something that black Americans can’t do, and that’s just one other thing they can scratch off their list.” Gibson’s All-Star Classic will be breaking down barriers too by bringing a racially mixed field into the exclusive circle of power and influence golf represents.

Some have questioned why he’s chosen now to return to the limelight. “It’s not to get back in the public eye,” Gibson said of the golf classic. “The reason I’m doing this is to raise money for the American Lung Association and BAT.”

Efforts to battle lung disease have personal meaning for Gibson, who’s a lifelong asthma sufferer. A past Lung Association board member, he often speaks before groups of young asthma patients “to convince them that you can participate in sports even though you have asthma…I think it’s helpful to have somebody there that went through the same thing and, being an ex-baseball player, you get their attention.”

He serves on the board of directors of BAT – the tourney’s other beneficiary. The organization assists former big league and minor league players, managers, front office professionals and umpires who are in financial distress. “Unfortunately, most people think all ex-players are multimillionaires,” he said. “Most are not. Through BAT we try to do what we can to help people of the baseball family.”

He hopes the All-Star Classic raises half-a-million dollars and gives the state “something it’s never seen before” – a showcase of major sports figures equal to any Hall of Fame gathering. Gibson said he came up with the idea over drinks one night with his brother Fred and a friend. From there, it was just a matter of calling “the guys” – as he refers to legends like Mays. Gibson downplays his own legendary status, but is flattered to be included among the game’s immortals.

What’s amazing is that baseball wasn’t his best sport through high school and college – basketball was. His coach at Tech, Neal Mosser, recalls Gibson with awe: “He was unbelievable,” said Mosser. “He would have played pro ball today very easily. He could shoot, fake, run, jump and do everything the pros do today. He was way ahead of his time.”

Gibson was a sports phenom, excelling in baseball, basketball, football and track for area youth recreation teams. He enjoyed his greatest success with the Y Monarchs, coached by his late brother Josh, whom Mosser said “was a father-figure” to Gibson. Josh drilled his younger brother relentlessly and made him the supreme competitor he is. After a stellar career playing hardball and hoops at Creighton, Gibson joined the Harlem Globetrotters for one season, but an NBA tryout never materialized.

No overnight success on the pro diamond, Gibson’s early seasons, including stints with the Omaha Cardinals, were learning years. His breakthrough came in ‘63, when he went 18-9. He only got better with time.

Gibson acknowledges it’s been difficult adjusting to life without the competitive outlet sports provided. “I’ll never find anything to test that again,” he said, “but as you get older you’re not nearly as competitive. I guess you find some other ways to do it, but I haven’t found that yet.”

What he has found is a variety of hobbies that he applies the same concentrated effort and perfectionist’s zeal to that he did pitching. One large room in his home is dominated by an elaborate, fully-operational model train layout he designed himself. He built the layout’s intricately detailed houses, buildings, et all, in his own well-outfitted workshop, whose power saw and lathe he makes use of completing frequent home improvement projects. He’s made several additions to his home, including a sun room, sky lights, spa and wine cellar.

“I’m probably more proud of that,” he said, referring to his handiwork, “than my career in baseball. If I hadn’t been in baseball, I think I would of probably ended up in the construction business.”

The emotional-physical-financial investment Gibson’s made in his home is evidence of his deep attachment to Nebraska. Even at the height of his pro career he remained here. His in-state business interests have included radio station KOWH, the Community Bank of Nebraska and Bob Gibson’s Spirits and Sustenance, a restaurant he was a partner in from

1979 to 1989. Nebraska, simply, is home. “I don’t know that you can find any nicer people,” he said, “and besides my family’s been here. Usually when you move there’s some type of occupation that takes you away. I almost moved to St. Louis, but there were so many (racial) problems back when I was playing…that I never did.”

His loyalty hasn’t gone unnoticed. “He didn’t get big-headed and go away and hide somewhere,” said Jerry Parks, a Tech teammate who today is Omaha’s Parks, Recreation and Public Property Director. “What I admire most about him is that he’s very loyal to people he likes, and that’s priceless for me,” said Rodney Wead. “He’s helped a lot of charitable causes very quietly…He’s certainly given back to Omaha over the years,” said Larry Myers.

Jerry Mosser may have summed it up best: “He’s just a true-blue guy.”

Because Gibson’s such a private man, his holding a celebrity golf tournament caught many who know him off-guard. “I was as surprised as anyone,” said Wead, “but so pleased – he has so much to offer.” Gibson himself said: “I have never done anything like this before. If I don’t embarrass myself too badly, I’ll be fine.”

If anything, Gibson will rise to the occasion and show grace under fire. Just like he used to on the mound – when he’d rear back and uncork a high hard one. Like he still does in his dreams. “Oh, I dream about it (baseball) all the time,” he said. “It drives me crazy. I guess I’m going to do that the rest of my life.”

Thanks for the memories, Bob. And the sweet dreams.

Related Articles

- Gibson (joeposnanski.si.com)

- It’s finally the Year of the Pitcher again (denverpost.com)

- National League Treasures: The Best Players in Each Franchise’s History (bleacherreport.com)

- Book Review: Sixty Feet, Six Inches by Bob Gibson & Reggie Jackson (othemts.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Wrestling is a proving ground. In an ultimate test of will and endurance, the wrestler first battles himself and then his opponent until one is left standing with arms raised overhead in victory. In a life filled with mettle-testing experiences both inside and outside athletics, Don Benning has made the sport he became identified with a personal metaphor for grappling with the challenges a proud, strong black man like himself faces in a racially intolerant society.

A multi-sport athlete at North High School and then-Omaha University (now UNO), the inscrutable Benning brought the same confidence and discipline he displayed as a competitor on the mat and the field to his short but legendary coaching tenure at UNO and he’s applied those same qualities to his 42-year education career, most of it spent with the Omaha Public Schools. Along the way, this man of iron and integrity, who at 68 is as solid as his bedrock principles, made history.

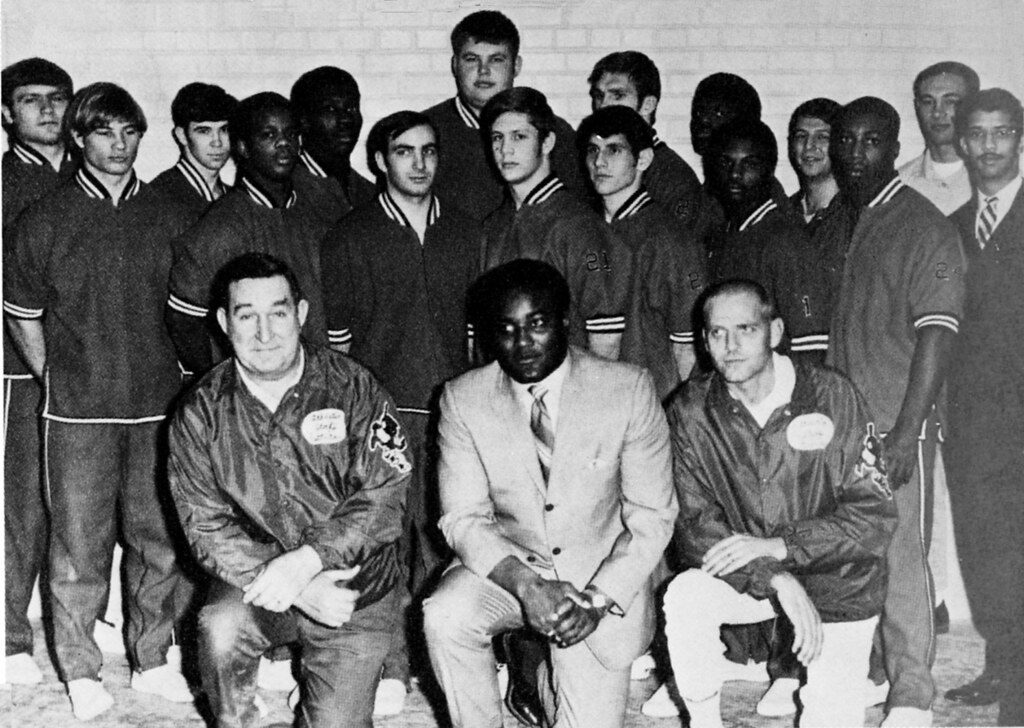

At UNO, he forged new ground as America’s first black head coach of a major team sport at a mostly white university. He guided his 1969-70 squad to a national NAIA team championship, perhaps the first major team title won by a Nebraska college or university. His indomitable will led a diverse mix of student-athletes to success while his strong character steered them, in the face of racism, to a higher ground.

When, in 1963, UNO president Milo Bail gave the 26-year-old Benning, then a graduate fellow, the chance to he took the reins over the school’s fledgling wrestling program, the rookie coach knew full well he would be closely watched.

“Because of the uniqueness of the situation and the circumstances,” he said, “I knew if I failed I was not going to be judged by being Don Benning, it was going to be because I was African-American.”

Besides serving as head wrestling coach and as an assistant football staffer, he was hired as the school’s first full-time black faculty member, which in itself was enough to shake the rafters at the staid institution.

“Those old stereotypes were out there — Why give African-Americans a chance when they don’t really have the ability to achieve in higher education? I was very aware those pressures were on me,” he said, “and given those challenges I could not perform in an average manner — I had to perform at the highest level to pass all the scrutiny I would be having in a very visible situation.”

Benning’s life prepared him for proving himself and dealing with adversity.

“The fact of the matter is,” he said, “minorities have more difficult roads to travel to achieve the American Dream than the majority in our society. We’ve never experienced a level playing field. It’s always been crooked, up hill, down hill. To progress forward and to reach one’s best you have to know what the barriers or pitfalls are and how to navigate them. That adds to the difficulty of reaping the full benefits of our society but the absolute key is recognizing that and saying, ‘I’m not going to allow that to deter me from getting where I want to get.’ That was already a motivating factor for me from the day I got the job. I knew good enough wasn’t good enough — that I had to be better.”

Shortly after assuming his UNO posts his Pullman Porter father and domestic worker mother died only weeks apart. He dealt with those losses with his usual stoicism. As he likes to say, “Adversity makes you stronger.”

Toughing it out and never giving an inch has been a way of life for Benning since growing up the youngest of five siblings in the poor, working-class 16th and Fort Street area. He said, “Being the only black family in a predominantly white northeast Omaha neighborhood — where kids said nigger this or that or the other — it translated into a lot of fights, and I used to do that daily. In most cases we were friends…but if you said THAT word, well, that just meant we gotta fight.”

Despite their scant formal education, he said his parents taught him “some valuable lessons scholars aren’t able to teach.” Times were hard. Money and possessions, scarce. Then, as Benning began to shine in the classroom and on the field (he starred in football, wrestling and baseball), he saw a way out of the ghetto. Between his work at Kellom Community Center, where he later coached, and his growing academic-athletic success, Benning blossomed.

“It got me more involved, it expanded my horizons and it made me realize there were other things I wanted,” he said.

But even after earning high grades and all-city athletic honors, he still found doors closed to him. In grade school, a teacher informed him the color of his skin was enough to deny him a service club award for academic achievement. Despite his athletic prowess Nebraska and other major colleges spurned him.

At UNO, where he was an oft-injured football player and unbeaten senior wrestler, he languished on the scrubs until “knocking the snot” out of a star gridder in practice, prompting a belated promotion to the varsity. For a road game versus New Mexico A&M he and two black mates had to stay in a blighted area of El Paso, Texas — due to segregation laws in host Las Cruces, NM — while the rest of the squad stayed in plush El Paso quarters. Terming the incident “dehumanizing,” an irate Benning said his coaches “didn’t seem to fight on our behalf while we were asked to give everything for the team and the university.”

Upon earning his secondary education degree from UNO in 1958 he was dismayed to find OPS refusing blacks. He was set to leave for Chicago when Bail surprised him with a graduate fellowship (1959 to 1961). After working at the North Branch YMCA from ‘61 to ‘63, he rejoined UNO full-time. Still, he met racism when whites automatically assumed he was a student or manager, rather than a coach, even though his suit-and-tie and no-nonsense manner should have been dead giveaways. It was all part of being black in America.

To those who know the sanguine, seemingly unflappable Benning, it may be hard to believe he ever wrestled with doubts, but he did.