Archive

LEOADAMBIGA.WORDPRESS.COM Seeking Sponsors and Collaborators: I Write About People, Their Passions and Their Magnificent Obsessions

LEOADAMBIGA.WORDPRESS.COM Seeking Sponsors and Collaborators: I Write About People, Their Passions and Their Magnificent Obsessions

As a steadily growing blog with now 400-plus unique visitors a day, leoadambiga.wordpress.com is seeking sponsorship. If you are a media company or angel investor or arts-culture-journalism patron and you see value in supporting a dynamic and popular blog site that tells the stories of people, their passions, and their magnificent obsessions, then contact blog author and host, Leo Adam Biga at leo32158@cox.net or 402-445-4666.

The site is also a ready-made platform for convergence journalism opportunities that add audio and visual streaming elements to posts. Addiitionally, the site is a platform for potential story series, books, documentaries, and other projects. Multi-media project proposals are welcome. Please note that Leo Adam Biga is also open to working with collaborators, including writers, artists, photographers, and filmmakers, on select monetized projects. If you have a project in mind, contact Biga at the above email or phone number.

Related articles

- A Journey in Freelance Writing – A Seminar with Leo Adam Biga (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Listen to Freelance Writer Leo Adam Biga’s Guest Bit on the New “Worlds of Wayne Podcast” at worldsofwayne.com (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

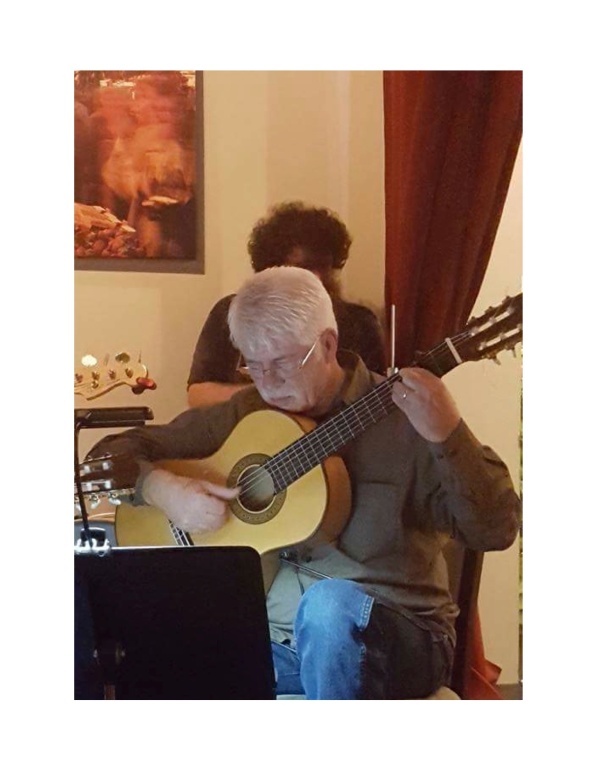

From the Archives: Hadley Heavin sees no incongruity in being rodeo cowboy, concert classical guitarist, music educator and Vietnam combat vet

When I saw Hadely Heavin perform classical guitar at the Joslyn Art Museum in the late 1980s I knew I had to write about him one day, and in 1990 I sought him out as one of my first freelance profile subjects. I’ve culled that resuling story from my archives for you to read below. What I didn’t know when I interviewed him that first time is what a remarkable story he has. I mean, how many world-class classical guitarists are there that also compete in rodeo? How many are combat war veterans? What are the chances that an inexperienced American player (Heavin) would be selected by a Spanish master (Segundo Pastor) to become the maestro’s only student in Spain? I always knew I wanted to revisit Heavin’s story and nearly two decades later I did. That more recent and expansive portrait of Heavin can also be found on this blog, entitled, “Hadley Heavin’s Idiosyncratic Journey as a Real Rootin-Tootin, Classical Guitar Playing Cowboy.” When I wrote the original article posted here Heavin’s mentor, Segundo Pastor, was still alive. Pastor has since passed away but his influence will never leave the protege. Heavin was still doing some rodeoing as of three or four years ago, when I did the follow-up story, but even if he has completely given up the sport he’ll always do something with horses because his love for horses is just that deep in him. The same as music is. I hope you enjoy these pieces on this consumate artist and athlete.

From the Archives: Hadley Heavin sees no incongruity in being rodeo cowboy, concert classical guitarist, music educator and Vietnam combat ve

©by Leo Adam Biga

Orignally published in the Omaha Metro Update

Hadley Heavin defies pigeonholing, The 41-year-old Omaha resident is an internationally renowned classical guitarist, but to ranchers in rural Nebraska he’s better known as a good rodeo hand. The University of Nebraska at Omaha instructor’s life has been full of such seeming incongruities from the very start.

Back in his native Kansas Heavin is as likely to be remembered for being a precocious child musician as an expert bareback bronc rider, star high school athlete and Vietnam War veteran. Today, despite lofty success as a touring performer, Heavin is perhaps proudest of being a husband and new father. He and his wife, Melanie, became first-time parents last year when their girl, Kaitlin, was born.

Music, though, has been the one unifying force in his life. His earliest memories of the Ozarks are filled with gospel harmonies and jazz, ragtime and country rhythms. Home for the Heavin clan was Baxter Springs, Kan., five miles froom the Oklahoma and Missouri borders.

“Basically I grew up with music and I’ve been playing it since I was 5. My father was a jazz guitarist and always had bands,” said Heavin. adding that his late father played a spell with Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys.

Heavin hit the road with his old man at age 7, playing drums, trumpet and occasional guitar at dances and socials.

“I was a little freak because I could play really well. I loved it, but it got to be a chore. I remember about midnight I’d start falling asleep. My dad would start to feel the time dragging and see me nodding, then he’d flick me ont he head with his fingertip and wake me up, and I’d speed up again.

“Most of my fellow students at school didn’t know I was doing this. I didn’t think I was doing anything special because everyone in my family were musicians. I grew up in that environment thinking everybody was like this. I couldn’t believe it when a kid couldn’t sing or carry a tune or do something with music.”

When Heavin was all of 11 he started playing rock ‘n’ roll, an experience, he said, that left him burned out on music, especially rock.

“I’m glad I got burned out on that when I did because I’ve still got students in their 20s trying to study classical guitar and wanting to play rock ‘n’ roll. They want to have fun,” he said disparagingly. “They just don’t realize rock is not an art form in the same sense. Classical guitar requires a lot of work and soul searching.”

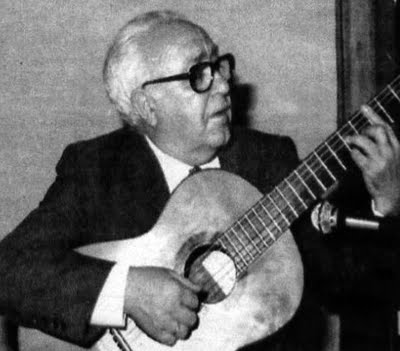

Heavin doesn’t mince words when it comes to music. Since he studied in Spain with maestro Segundo Pastor, he performs and teaches the traditional romantic repertoire that originated there. He feels the music is a deep. direct reflection of the Spanish people, with whom he feels a kinship.

“Spanish people are much warmer than Americans. We’re not brought up with the passion those people are brought up with. That’s why I prefer listening to European artists.”

He said classical guitar “demands” a passionate, expressive quality he finds lacking in most American guitarists with the exception of Christopher Parkening.

“Who a student studies with makes a big difference. I don’t think I ever would have played the way I do if I had never studied with Segundo.”

Heavin feels Pastor selected him as a student because he saw a hungry young musician with a burning passion.

“He wouldn’t have been interested if he didn’t see things in my playing that were like his. Frankly, he doesn’t like very many American guitarists. He thinks they’re very shallow performers.”

Segundo Pastor

The acolyte largely agrees, suggesting that part of the problem is most American musicians don’t face as many obstacles or endure as many sacrifices for their art as foreign musicians.

“My students are spoiled. How are they going to suffer for their art?” he asked rhetorically.

He said that when he turned to the classical guitar in the early ’70s, after seeing combat duty in Vietnam and having his father pass away, he knew what hard times were. “I suffered because by then my father was gone and my mother couldn’t support me. Somehow I played guitar and kept myself fed, but I didn’t have a penny, really, until I was 32. But I loved the guitar and I didn’t worry about those things. People are kind of unwilling to do that anymore.”

He dismissed the new guitarists who denigrate the traditional repertoire in favor of avant garde literature as mere technicians.

“I hate to say this but about all the concerts I’ve been to with the new guitarists have been very boring, driving audiences away from the guitar. It’s a real shame. They’re championing these avant garde works, which is fine, but they can’t play the Spanish and romantic repertoire at all. They just can’t phrase it. It’s not in them. They sound like they’re playing a typewriter.

“There’s a lot of great guitarists now, and they’re excellent technically, but there’s still only a handful of great musicians.”

He hopes artists like Parkening and Pastor help audiences “discern the guitarists from the musicians.”

It may surprise those who’ve seen Heavin perform with aplomb at Joslyn Art Museum’s Bagels and Bach series or some other concert venue that he as at ease on a horse as he is on a stage, as facile at roping a steer as he is at phrasing a chord, or as penetrating a critic of a rodeo hand’s technique as of a classical guitarist’s. But a look at his thick, powerful hands, deep chest and broad shoulders confirms this is a rugged man. And he does work out to stay in trim, including working with horses.

“As a matter of fact this is the first year I haven’t rodeoed in many years,” he said. “The only reason I’m not this summer is that I’m in the middle of doing an album and my producer’s worried about my losing a finger. I team rope now because I’m too old to ride rough stock. If I do get out of roping to protect my hands I’m probably going to have to do cutting or something just to stay on a horse. It’s just that horses are in my blood. But it’s tough with this kind of career because it takes so much time.”

Heavin has competed on the professional rodeo circuit all over Nebraska. “It’s funny,” he said. “I draw good crowds at my concerts in western Nebraska because I know all the ranchers and rodeo people, and they’re curious to see this classical guitarist who rodeos, too. I was playing a concert in Kearney and there were some roping friends in the audience. After I was done I went up and said to them, ‘These other people think I’m a guitarist, so don’t be telling them I’m a cowboy.’ But it was too late. They already had. I try not to advertise it too much.”

Heavin took to the rodeo as a boy to escape the music world he’d run dry on. “I started riding bulls and bareback broncs. I wanted to be a world champ bronc rider,” he said.. He rodeoed through high school and for a time in college. He also participated in football, wrestling and track as a prep athlete, winning honors and an athletic scholarship to Kansas University along the way.

“I think my dad put pressure on me to be an athlete to some degree because he wanted me to be well-rounded.”

At KU Heavin played on the same freshman football team as future NFL great John Riggins, a free-spirit known for his rebel ways. “I’ve never seen a guy that trouble came to so quickly. We used to go to bars and there was always a fight and John usually started it. He had more John Wayne in him than John Wayne.”

Another classmate and friend who became famous was Don Johnson, the actor. Heavin hasn’t seen the Miami Vice star in years but stays in touch with his folks in Kansas.

It was the late ’60s and Heavin, like so many young people then, was torn in different directions. “I decided I really didn’t want to be in school but I had the draft hanging over my head. I took a chance anyway and dropped out…and I was drafted within two months.”

The U.S. Army made him an artillary fire officer and shipped him off to Vietnam before he knew what hit him. He shuttled from one LZ to another, wherever it was hot. “I was what they called a bastard. I was with the 1st Field Force. I was in the jungle the whole time. I saw base camp twice during a year in-country,” he said.

Heavin was shot in action and after recovering from his wounds sent back out to the war. Luckily, his tour of duty ended without further injury and he finished his Army hitch back home at Fort Riley, Kansas. While stationed there he began missing working with horses and on a whim one day entered the bareback at a nearby rodeo.

“I drew a pretty rank horse, plus I hadn’t ridden in years and I was still sore from my war injuries. I got hurt. When I got back to the base they were mad at me because I couldn’t pull my duty. They were going to court-martial me.”

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed and the incident was forgotten. “When I got out of the service my dad died shortly thereafter, and there was no music anymore.” Heavin had been working a job unloading trucks for two years when a friend suggested they see a classical guitarist perform. The experience rekindled his love for music.

“I was enthralled. And it just came over me like that,” he said, snapping his fingers. “That’s how fast I made my deicison to play classical guitar.”

Until then Heavin said he had never really heard classical guitar, much less played it. He began by teaching himself.

“I worked really hard. As soon as my hands could take it I was practicing six to eight hours a day and working a full-time job — just so I could get into college.”

Heavin brashly convinced the chairman of the Southwest Missouri State University music department to start a degreed classical guitar program for him. “I said, ‘Look, I want to get a degree in guitar and I’m determined to do it. And I don’t know why nobody has a program in this part of the country.’ He said, ‘I agree, let’s try this and see what happens.'” As the pioneering first student hell-bent on finishing the program, Heavin graduated and he said the program has “grown into something really nice and become very popular.”

His chance meeting with his mentor-to-be, Segundo Pastor, occurred at a concert in Springfield, Mo., at which Heavin was playing and the maestro was attending on one of his rare American visits. Heavin was introduced to “this little old man who couldn’t speak English” and arranged to see him later. He played for Pastor in private and the master liked the young man’s musicianship. The two began a correspondence.

When Pastor returned the next year he asked to see Heavin. “I spent practically a whole day with him and I played everything I knew. Then he said, ‘If you come to Spain I’ll teach you for nothing.’ I didn’t realize then what this meant or how it was going to work out,” Heavin said. A university official aided Heavin’s overseas studies. But the student still had no inkling his apprenticeship would turn out to be what he termed “one of the most wonderful experiences of my life.”

“When I arrive there was an apartment for me. The maestro’s wife was like my mom. His son was like my brother. And I realized only after I got there that I was his only student. He rarely takes them. There were Spanish boys waiting in line to study with him.”

Appropriately, the rodeoer lived a block from the Plaza de Toros, the bullfighting arena, and next door to the hospital for bullfighters.

“I lived in the culture. I wasn’t with Americans at all. My friends were all Spanish. I taught them English, they taught me Spanish. During the 10 months I was there I had a two-hour lesson from Segundo almost every day. He puts all of himself into that one student. That’s why he doesn’t take on many. It was really like a fairy-tale because the man literally gave me a career. The thing that’s odd about it is that I had only been playing about a year when the maestro invited me to Spain. It was confusing because there were Spanish boys who could play better than I.”

It was a question that nagged at Heavin for a long time. why me?

“The whole time I was in Spain I kept asking him, ‘Why did you pick me?’ and he would never answer it. The last night I was there he knocked on my door and we went to the university in Madrid. It was one of those romantic Spanish evenings. We were walking down a wet, cobblestone street and he put his arm on me and said, ‘Yeah, the Spanish boys are good guitarists but some day you’ll be a great guitarist,” recalled Heavin, still touched by the memory. “That gave me a lot of confidence to go on.”

During his stay abroad Heavin toured with Pastor throughout Spain, When the apprenticeship ended they performed duo concerts across the U.S., including New York’s Carnegie Hall. Heavin’s career was launched.

While the two haven’t performed publicly since then, Heavin said they remain close. “Now that I’m in the States he comes more often. When he visits we just have fun and enjoy ourselves. Two years ago he came with Pedro, a friend from Spain, and they did a duo concert here.”

Asked if in some way Pastor replaced his father, with whom he was so close, and Heavin said, “Oh yes. He’s like my father, no doubt. He’s my mentor, too.”

After earning a master’s degree at the University of Denver Heavin came to UNO in 1982. He heads the school’s classical guitar program, which he said is a good one. “I’ve got some students who play very well.”

Besides teaching Heavin performs 25-30 concerts a year, a schedule he’s cut back in 1990 to work on his first album.

“I’ve just finished doing the research on the pieces I want to put on. Now I’m learning the pieces. I’ll probably go into the recording studio in October or November,” he said.

As with Pastor singling him out for the chance of a lifetime, a patron has discovered Heavin and is helping sponsor him. “Another fairy-tale happened. A stockbroker heard me play and thinks I should have lots more recognition. He wants to get involved in my career.”

The guitarist is looking forward to touring more once the album is done. He has been invited to perform in Australia and Pastor has asked him to do concerts in Spain.

“People ask me why I live in Omaha and not on the coast,” he said. “I dearly love Omaha. I love the Old Market. I don’t like huge cities.”

Heavin, who practices his art about five hours daily, said success has little to do with locale anyway. “It’s an attitude. To do anything well requires an aggressive attitude. You have to just want to, and I’ve always done well financially playing guitar and teaching.”

Related articles

- Journey Through Latin America with Classical Guitarist Michael Anthony Nigro (worldculturesaustin.com)

- From the Archives: Cowboy-turned Scholar Discovers Kinship with 19th Century Expedition Explorer (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Home boy Nicholas D’Agosto makes good on the start “Election” gave him; Nails small but showy part in new indie flick “Dirty Girl”

In the late ’90s Alexander Payne returned to his hometown of Omaha, Neb. to make Election and in line with his desire of filling out his film with authentic representations of this place, he cultivated two fellow home boys for the cast. Chris Klein got the film’s third main speaking part. Nicholas D’Agosto got a smaller part but like Klein he used the film as a door opener in Hollywood and has built a nice career. Both were high school students in Omaha and had never acted professionally before when cast in Election. For whatever reasons Klein hasn’t had much to do with Omaha since he left here and rode the wave of fame that came with Election, followed closely by American Pie and a series of other youth comedies. At least D’Agosto is coming back to Omaha for an Oct. 17 Film Streams screening of one of his four 2011 releases, Dirty Girl. He’ll be joined by writer-director Abe Syliva and producer Jana Edelbaum. The film is getting good reviews, mostly for star Juno Temple, and D’Agosto is happy he got to stretch with his part as a drifter exotic dancer.

Home boy Nicholas D’Agosto makes good on the start “Election” gave him

Nails small but showy part in new indie flick “Dirty Girl“

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to be published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

When Alexander Payne cast locals Nicholas D’Agosto and Chris Klein in Election, he opened doors for the two dreamy, boy-next-door types.

Klein burned hot and bright before flaming out. D’Agosto’s gradual rise may reach new heights with his performance in Dirty Girl. He joined writer-director Abe Sylvia and producer Jana Edelbaum for a Film Streams Q&A screening Oct. 17, marking the first time he’s accompanied one of his films back home.

Dirty Girl opens wide on Friday.

D’Agosto plays Joel, an exotic entertainer who hitches a ride from wild child Danielle (Juno Temple) and her gay friend Clarke (Jeremy Dozier). Drawn together by shared outsiderness, the drifters form an instant family. D’Agosto’s screen time is brief, but he makes the most of it.

“It’s a small role but a memorable role,” he says. “It has a really beautiful scene that’s kind of the catalyst for the Juno Temple character finally finding some true relationship. Our characters share a sort of common understanding of two people who’ve been rejected by their fathers. They feel lost and sort of transient. I’m able to tenderly let her know she’s not alone in this kind of pain.

“There’s a lot of depth and dynamism to this character in terms of what he gets to do in a small period of time. For any actor that’s great and for me it’s a lot of stuff I haven’t got to play before, and I jumped at the chance. It’s just fun to take risks.”

Sylvia says, “What’s so funny is Nick does have a very sweet face and a very genial nature but in my movie he essentially plays a hustler. It’s a deceptive character in that you want to like him and yet you know he’s a bit dangerous, and I think it works in our favor Nick’s so likable.”

Edelbaum, who admired Nick’s work in Rocket Science, says, “The challenge was finding an actor who would be wish fulfilling to both a gay and a straight audience and Nick fits the bill. He’s sweet and he’s smart and he was so lovely to work with. He just gave and gave and gave, and you can just see it.”

In the 12 years since Election D’Agosto’s become a journeyman television-film actor, with four feature releases alone in 2011, but he’s ever-mindful of where it all started.

“The truth is while I was shooting that (Election) I really didn’t understand how important that moment would be for me. I didn’t realize this was my break, this was the thing that was going to bring me out to Los Angeles ultimately and have a foot in the door. I just didn’t know so many things. I was so naive at the time.”

He was a 17-year-old at Creighton Prep, whose artist alums include Payne, Holt McCallany, Conor Oberst, Richard Dooling and Ron Hansen.

He says Election was “such a singular film” it provided “a leg up” as an industry newcomer. Long after parlaying that success into a career he says “it’s exciting to bring my work back to Omaha.” Besides starting a new indie pic and auditioning for TV’s pilot season, he’s honing his craft in classes and trying stand-up for the first time. “I’m trying to push my own personal boundaries as a performer right now.”

Related articles

- Dirty Girl: Not Your Average Slutty Girl/Chubby Gay Kid Road Movie (queerty.com)

- Writer/Director Abe Sylvia Interview DIRTY GIRL (collider.com)

- Emma Bell, Nicholas D’Agosto and Tony Todd Interview FINAL DESTINATION 5 (collider.com)

- ‘Final Destination 5′: Nicholas D’Agosto takes a leap of faith (herocomplex.latimes.com)

From the Archives: Photographer Monte Kruse works close to the edge

I’ve dipped into the archives again for this early profile I did of photographer Monte Kruse. The man has crazy talent. When I first met him 21 years ago the bulk of his work was as photojournalist but as the years have gone by h’s gravitated more and more to fine art photogtaphy, often shooting nudes. The first two images below are from fairly recent work he’s done of agrarian nudes – depicting the human form in the throes of doing farm work and showing the nuance and contours of bodies hardened and developed by that kind of labor intensive, close to the ground activity. This blog also features a later story I did on Monte titled “Photographer Monte Kruse Pushes Boundaries.” You’ll also find stories on the blog about Monte’s mentor, photographer Don Doll. The blog features yet more stories on other photographers, including Monte’s good friend Jim Hendrickson, as well as Larry Ferguson, Ken Jarecke, Rudy Smith, and Pat Drickey, superb imagemakers all. Look for a big feature on Jim Krantz in November. And if you’re a film fan, the blog has dozens of pieces on filmmakers and other film artists, including Alexander Payne, Nik Fackler, Joan Micklin Silver, Charles Fairbanks, and Gail Levin. Explore…enjoy.

From the Archives: Photographer Monte Kruse works close to the edge

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Omaha Metro Update

Picture the hard but wild throwing pitcher Tim Robbins portrayed in Bull Durham. A tall, lean, free-spirited kid whose oversized ego hid an underlying naivete and vulnerability. That may be a pretty close take on what Monte Lee Kruse looked liked pitching for Creighton University in the mid-’70s, before he became a noted photographer. The 6’5, 200-plus pound left-handed power pitcher must have cut an intimidating figure on the mound.

Kruse was good enough to get drafted by the Chicago White Sox, but knee injuries prevented him from ever playing an inning in the professional ranks. But this is not a story about Kruse the athlete. He long ago traded in a ball and glove for a camera as his means of self-expression.

The point is that many who know Kruse today as a talented freelance photographer of gripping human scenes would be surprised to learn he played competitive sports at all. Kruse is too complex to pin down easily. Just when you feel you have a bead on him, his story throws you a curve.

Someone who knew him back when – former Creighton athletic director Dan Offenburger – recalls Kruse as a “quiet, kind of country kid. Intelligent. He kind of marched to the beat of a different drummer.”

At 35, Kruse still exudes a commanding presence that sets you a little on edge. His sheer size is daunting enough. Add to that the force of his mercurial personality, blunt manner of speaking and piercing eyes and your first impression of Kruse is that of the brooding artist. He admits he can be temperamental.

“I swear a lot and I can be a real pain in the ass to work with because I’m real nervous and I try to get everything just right. I really push people,” he said. “But when they see the end product…well, I haven’t had a client yet that’s been dissatisfied.”

After spending a little time with him though his big, overgrown kid’s mug and down-home informality put you at ease. Just beneath the rough-hewn exterior is the keen sensitivity and intelligence that characterize his work.

In the stark black and white tones of his photos you sense his nearly spiritual kinship with and empathy for the disenfranchised of society. You feel the sensualist’s appreciation for faces and bodies and his appetite for life.

“I’m out to experience life to its fullest extent,” he said almost as a motto.

The documentary, fine art and commercial photographer travels widely on assignment across America and abroad. Home for Kruse is not so much a place as a state of mind. That seems about right for someone who has lived out of his car in leaner times. Perhaps as a reminder of those times his tiny hatchback is loaded with personal possessions.

Home is often a room at the YMCA or a hotel. Omaha is as close to a permanent haven as he has, spending several months of the year here.

Much of his photojournalistic work documents the lives of people on the fringe of society, where Kruse has been himself.

Anyone seeing his gut-wrenching images of the mentally ill homeless or AIDS patients is struck by their strong emotionalism and stark, naked truth. His photos combine the best elements of art and reportage. They are at once interpratative and restrained, as enigmatic as life itself.

In 1987 he spent three weeks documenting a Chicago AIDS hospice called The House. The resulting photos have been published in several newspapers.

“It was awful. All the guys I photographed are dead now. You have to keep up kind of a wall. If you get too involved, you’re not going to be able to function. I do get choked up a little because I get to know these people real well. But you still have to get your f-stops right and the image right,” Kruse said. “You do that the best you can and then you leave. I’m not a doctor, I’m not a social worker. My job is to go in there and photograph these people and write about them. That’s how I can be a doctor or shaman. Then it’s up to the public to disseminate the information.”

Far from any cool, impassive detachment, however, his photos are clearly the work of a caring observer. In fact, Kruse pursued the AIDS story because a close friend of his, Gary H., was stricken with the disease.

“When you see somebody dying of AIDS you better feel something. You don’t have to spread it across the page. You have to have restraint and tell the information, but you better have a sense of compassion. Objectivity is for journalism class. When you get out in the real world you’re going to have a point of view and it’s going to come through.”

Many of the most telling shots depict a patient named Bill. In one, he writhes in pain while taking a bath. In another, he prays in his bed of despair. And in another he receives a nurse’s tender attention.

Most images snatch glimpses of hope, such as a patient and his friend embracing on a stoop or planning their future together on a walk.

A lingering portrait is that of Daryl, a patient with one finger pressed against his temple. The caption quotes Daryl saying, “If I had any guts I would take a gun to my head and get it over with, but you know what, I won’t do it because I believe a cure will be found somehow, someway. Maybe I am gutless, I don’t know.”

Kruse has known degrees of desperation himself. A string of carthetic events helped shape him and now informs his work.

By 1977 he had abandoned the sports and college scene altogether, only recently having discovered photography. A passion for the medium and life led him on a cross-country odyssey that eventually landed him in California, where he learned his craft and worked as a fine art photographer. He knew he’d found his life’s work.

“It’s the only thing I’ve ever done that can match the excitement of my sports career.”

In Calif. he photographed his first nudes, which he continues to shoot today. He also did landscapes until tiring of that genre. “It didn’t fit my temperament, so I started doing people – photojournalism. I was kind of shy to begin with and then I just gradually got used to it.”

He said it’s no accident his work focuses on people. “I think that’s just a reflection of me. I’ve always loved people. I’ve always loved talking to people, finding out what it’s all about. If I’m not around people I get real nervous. I have to be flooded by humanity.”

He returned to Creighton a few years later to study under Rev. Don Doll, a Jesuit priest and world class photojournalist whose work Kruse greatly admires.

“I had a period where I was really spinning my wheels, caught between doing fine art work and photojournalism. One reason I came back to Creighton was Don Doll. He’s a great photographer. He’s inspiring to talk to. If I had a mentor it would probably have to be him. I also went back to Creighton because I have a lot of friends here. After I get back home from being gone three months I sometimes just like to come to Creighton and walk around the campus.”

Kruse graduated from the school in the late ’70s and later served a hitch in the U.S. Army. There was a trip to the Middle East, too. His life and vocation were turned upside down in a three-year span during the ’80s when both his parents died.

“My father died all of a sudden. I don’t know what happened but I had an explosion in my work where I got really intense.”

Then his mother became terminally ill with cancer and Kruse spent three months caring for her. “My mother died and I went through another metamorphosis.”

It was while working those tragedies with the help of his photography that Kruse found his unique visual style. He prefers a highly naturalistic style that employs available light for dramatic effect. He brands himself with the tag, “Found Light Photography.”

Like many young artists trying to establish themselves Kruse struggled making ends meet. He found it difficult getting his work published because so much of it graphically shows aspects of the human condition readers would rather not be reminded of.

“The toughest thing to do is docuementary work. There is not a market for it,” he said. “People don’t want to look at that stuff and they don’t want to be made aware of it.”

He suffered through some hard times before breaking through. “Two or three years ago I missed a lot of meals I was making so little money. When I was in really bad shape , yeah, I lived out of my car. If it hadn’t been for the support of people like my brother, Mark, I would have been a derelict in the streets. My brother actually kept me afloat for two or three years.” He said Mark, who lives near Omaha, is one reason why he remains here.

“I can’t survive without Mark. He’s the only person I have left out of my (immediate) family. He’s done so much for me. It’s kind of difficult to leave somebody who’s been that close to you for that long. We don’t see each other for two or three month periods, but on the other hand it doesn’t really matter. If you love somebody what’s the difference if you’re gone a year? I think it’s important for an artist and his work to have a center. If you don’t, what are you? You’re nothing.”

Creighton University

Kruse said his off-the-beaten-path lifestyle is distorted by some into bigger-than-life dimenstions. What some see as eccentric is really practical in his eyes.

“There’s kind of a mystique and romantic notion people have about me. But the YMCA is actually a nice place to live. If you’re in town for two weeks why should you pay $50 a night at a hotel when all you’re going to do is sleep there? I’m out to purchase my freedom, and if I had to live in a pig pen for the next three years I would do it.”

A crucial piece of Kruse’s freedom is being able to “do work that really matters.” He said, “I can’t really explain it, but it’s what keeps me going.” He discovered how to secure that freedom a few years ago by doing corporate photography, which pays far better than photojournalism. He snaps candid shots of CEOs and rank and file workers for annual reports, newsletters, brochures and other corporate publications. His local clients include Creighton University, the Catholic Health Corporation, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Ramsey Associates Inc.

“In an indirect way my corporate work finances my more humanistic work. For a lot of years it was rough and even now it can be rough, but I have nough people that back me today. That backing can go -it’s always tenuous. But I think my clients are my friends.”

A $3,000 or $4,000 corporate job can underwrite his taking riskier, lower paying assignments, such as his accompanying Rev. Ernesto Travieso and about 80 healthcare professionals and students to the Dominican Republic in 1988. The medical caravan went to the country under the auspices of Creighton’s Institute of Latin American Concern. Kruse documented caravan members delivering medical care and supplies to impoverished natives at rural clinics that took three to four hours to reach by backpack and mule.

“Monte came with us and had a good rapport with the people there,” said Travieso. “He made a documentary slide presentation on the project and it was really, really beautiful work.”

Kruse feels his own travails have helped him understand other people’s plight. “Sometimes I look back on when I was on my ass, with nothing to do, and how people looked at me. It wasn’t very pleasant. I learned never to make judgments upon people. You just accept them the way they are.”

Last year saw Kruse do several documentary projects. One brought him to Los Angeles’ skid row, where he photographed the mentally ill homeless for a national photo agency. “As I was leaving that shoot I was choked up. The homeless have rights, too. They’ve kind of chosen a different way of living, unless they’re mentally ill, but this is how they live, and it should be accorded them.”

After completing the AIDS and homeless shoots and having his mother die Kruse was drained. “I said, ‘Man, I’ve got to do something a little more upbeat.'” Fortunately a Kennedy Foundation project on mental retardation surfaced. He described the assignment as “very upbeat, very human.” For it he traveled all over the U.S., spending two weeks with each of his mentally retarded subjects. One was a girl living just outside Sheldon, Iowa, near his hometown of Little Rock. “This farm girl is an absolute angel. I photographed her taking care of sheep on her father’s farm. She sews, she does everything.”

Inspired by the film My Left Foot, Kruse returned to Sheldon last summer to record the daily lives of a married couple with cerebral palsy. The photos are running as a special feature in the Sheldon Iowa Review, a prestigious small town paper. He said the project is “something that I’ve really been invovled with. It’s taken a lot of my heart and soul, and now we’re having to go through the woes of trying to get it published.” Editor Jay Wagner confirms that while Kruse can be “a bit demanding, when you’re working with someone as talented as Monte I guess it doesn’t matter. He’s got a great eye.” Wagner calls the pictures “powerful.”

Kruse recently went to Fargo and Grafton, N.D. to profile developmentally disabled individuals there for the Catholic Health Corporation. He approaches the disabled like all his subjects.

“I just think that they’re people like you and I. On a certain level you can communicare with them and have a helluva good time, or a helluva bad time. You’ve got to let them be who they are.”

That philosophy underscores his general technique for getting people to be themselves before the camera. “You’ve got to observe people and if you stay with them long enough they’ll always fall into who they are and what they do. Then you can tell them to hold that. I only photograph people that want to be photographed and want to tell their story.”

He was in Chicago recently making arrangements to photograph some of the city’s cultural icons, including author Studs Terkel, columnist Mike Royko and blues musician Louie Meyer, for an American artists series he is shooting with the aid of a grant. He plans going to New York, L.A. and other locales for more artist portraits.

“There’s so many people I’d love to do – Eudora Welty, Jacob Lawrence, Sonny Rollins, Gregory Peck. I feel I have to do Gordon Parks, the filmmaker-photographer-writer. I’ve read about him and what he went through and it’s always kind of kept me going.”

His goal is to publish the photos in a book someday. with the help of corporate sponsors. It may sound crass but Kruse enjoys the business side of art. “A lot of it is just getting out there and pressing flesh. You’ve got to hustle.”

Now that he has tasted success, he isn’t about to let it slip away. He said that while he “didn’t mind being poor at the time, I could never go back to living like that. I’m into fine dining, I love fine wines, I love women. To hell with the starving artist bit. That’s a myth of the past.”

Related articles

- Photographer Larry Ferguson’s Work is a Meditation on the Nature of Views and Viewing, (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Omaha Lit Fest: “People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like”

Seven years ago the quirky (downtown) Omaha Lit Fest began, and as an arts-culture writer here I’ve found myself writing about it and some of its guest authors and their work pretty much every year. The following piece for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is a preview of the 2011 edition, whose guests include Terese Svoboda (Bohemian Girl) and Rachel Shukert (Everything is Going to be Fine). The festival’s founder and director, novelist Timothy Schaffert (The Coffins of Little Hope), is the subject, along with the event, of several articles on this blog. If you’re a local and you have never done the fest, then shame on you. Make sure you do this time around. If you happen to be visiting during its Oct. 13-15 run then make sure you check it out and experience a sophisticated side of Omaha that may be new to you. Sure, this kind of thing is not for everyone, but it’s a fortifying intellectual exercise you’ll be glad you did. Besides, it’s free, most of it anyway. This year is a bit different in that I’m serving on a panel of local arts-culture writers discussing our role in framing Omaha’s arts scene, including its artists and art oganizations.

Apert from the Lit Fest, this blog also contains many more articles on authors and books of all kinds. Go to the books category on the right and discover the many writers and works I’ve been fortunate enough to report on and read.

Omaha Lit Fest: “People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In his capsule of the 2011 (downtown) Omaha Lit Fest founder-director and novelist Timothy Schaffert draws a parallel with The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Specifically, to the humbug Wizard’s endowing the Tin Woodman with a heart made of silk and sawdust, with some soldering necessary to better make the heart take hold.

As Schaffert (The Coffins of Little Hope) suggests, the writer’s process is part alchemy, part major surgery, part inspiration, part wishful thinking in giving heart to words and ideas and eliciting readers’ trust and imagination. Thus, he writes, this seventh edition of the Lit Fest focuses on “the heart and mechanics of writing” as authors “lift the corner of the curtain on their methods and processes.”

Consistent with its eclectic tradition of presenting whatever spills out of Schaffert’s Wizard’s mind, the Fest includes panels, exhibitions, salons and workshops that feature the musings and workings of poets, fiction writers, journalists and artists.

Guest authors include native Nebraskans turned New Yorkers Terese Svoboda, whose new novel Bohemian Girl has received ecstatic reviews, and Rachel Shukert, now at work on two new novels, a television series she’s adapting from her memoir Everything is Going to be Great and a screenplay.

The free Fest runs Oct. 13-15 at the W. Dale Clark Library, 215 South 15th St. and at Kaneko, 1111 Jones St. “Litnings” unfold the rest of the month at other venues.

With Lit Fest such an intimate Being Timothy Schaffert experience, it’s hard gauging it’s place in the Omaha cultural fabric.

“What we do is fairly esoteric. I’m always meeting people who have never heard of it and I definitely wouldn’t be able to handle it if it was as large as some other cities’ lit fests, which draw hundreds and hundreds of people. So I like it the way it is. I’ve often thought I misnamed it, that I probably shouldn’t have called it a festival, but called it a salon or something. So it’s a fraud basically,” Schaffert says with an ironic lilt in his laugh.

He quotes Abraham Lincoln to sum up the event’s cognoscenti appeal: “People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like.”

Mention how the programs feel peculiarly personal to him, Schaffert says, “It doesn’t always come together perfectly, but, yeah, I definitely try to shape it.” Ask if he pulls the strings behind the curtain, he says, “In the past it’s usually been just me but this year I’ve worked some with Amy Mather, the head of adult services at the W. Dale Clark Library. They’re cosponsors.”

That Schaffert pretty much conceptualizes the show himself is a function of limited resources and, therefore, a necessity-is-the-mother-of-invention approach. “We have virtually no budget. It actually strangely makes it even more interesting I think when you’re trying to do it on the cheap.” Of this labor of love, he adds,. “It is fun.”

Then, too, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln English instructor, Prairie Schooner web-contributing editor and Nebraska Summer Writer’s Conference director is well-plugged into writing circles. He’s also published by premier houses Unbridled Books and, soon, Penguin, which just bought his in-progress The Swan Gondola, a tragic love story set at Omaha’s 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition.

From the start, he’s viewed the Fest as a means of framing the local lit culture. Shukert appreciates the effort. She doesn’t recall a visible Omaha lit scene when she lived here, saying, “I actually think probably there was but it just hadn’t been identified yet, and once somebody is like, Wait, this is going on, then it’s like all these writers and book people can kind of like out themselves as part of a literary community and come together. I think that was an incredibly smart move on Timothy’s part to recognize there was this incipient thing that just needed someone to name it.”

She says, “I feel a nice balance he’s managed to strike is finding local people and native Omahans who have national profiles and people who have no connection to Omaha at all except this is a cool event they want to be at. It’s a nice mix, and that’s important.”

Schaffert notes the 2011 edition is heavy with native Nebraska authors “because so many local writers or writers with local ties have had new books come out in the last year and a half or so, so this is an opportunity to have them talk about their new works.” Those local scribes range from: Omaha World-Herald political cartoonist Jeffrey Koterba, whose memoir Inklings made a big splash, to OWH lifestyles columnist Rainbow Rowell, whose debut novel Attachments did well, to Mary Helen Stefaniak (The Califfs of Baghdad, Georgia) and David Philip Mullins (Greetings from Below).

Of the Nebraska ex-pats participants, perhaps the one with the largest national profile is Ogallala-born and raised Terese Svoboda, a poet and novelist praised for her exquisite use of language. In Bohemian Girl, she describes a hard-scrabble girl-to-womanhood emancipation journey on the early Nebraska frontier. The work contains overtones of True Grit, Huckleberry Finn and Willa Cather.

Peaking her intrigue were “pictures of 30 year-old pioneer women who looked like they were 70…and then they wrote diaries that were extremely cheerful — I just wondered what was going on there.” Charged by the feminist and civil rights movements’ challenge to let muted voices be heard, she says “in some ways Bohemian Girl was setting off to let those voices free or at least to talk about them.”

In some ways her book is a meditation on bohemianism as ethnicity, state of mind and lifestyle. “I was born in Ogallala as the oldest of nine children. My Bohemian father is a rancher, farmer and a lawyer, and my Irish mother painted. They read great books together and recited poetry they had memorized in high school in Neb. And I wore pointy red glasses in high school because I was the bohemian girl.”

Her proto-feminist heroine enlists Bohemian pluck and bohemian invention to survive hardships and seize opportunities in finding prosperity, if not contentment.

Terese Svoboda

Svoboda says “the picaresque story” sets out “to correct Willa Cather about Bohemians — they were more interesting than she portrayed them, and that’s dangerous territory I know to say, but I felt Cather was not a Nebraskan, she was from Virginia, and she looked at the people who settled there with that kind of eye. In fact, her point of view is always a little bit distant. So I wanted to get right inside a girl and show how hard it was and how the opportunities and the choices she makes are her own.”

As a reference point Svoboda drew on a creative pilgrimage she made to Sudan, Africa and to her own prairie growing up.

“I used the experience of my year spent in the Sudan for what it would be like to be a girl out in the bare prairie — blending that with my own experience in western Neb., the Sand Hills especially.”

Those lived vignettes, she posits, “contributed to the authenticity.”

Schaffert is among Svoboda’s many admirers.

“She brings a poet’s rich sense of language to her fiction. I feel like that’s what makes her novels and her short stories so exciting — they’re not weighty with language, they’re not inaccessible, but you do have to read them carefully to fully enjoy them. I think her new novel Bohemian Girl has eloquence. It’s eclectic, it’s whimsical, unsettling, and it has its heart in Nebraska and Nebraska history.”

The depth and precision of Svoboda’s language come from endless reworking.

“I do work hard at that. I am very attentive to each word. I am not a transparent writer — that is to say writing prose where the words are just something the reader falls into a dream for the characters and the plot. Because my background is a poet, I see each word as a possibility and each narrative exchange as a possibility, so nobody wastes any time going in and out of rooms or talking about the weather.

“I really respect the reader and their intelligence and hope that they appreciate I do that. I really think every word they read should be worthy of them.”

She didn’t plan on being a novelist, but a life-changing odyssey changed all that.

“I would have been perfectly happy to be a poet forever…but when I went off to Africa I had such a profound and emotionally difficult experience of being in practically another planet, I wrote a novel, Cannibal, about it. I felt I had to write prose.”

She only came to finish the novel, however, after struggling through 30 full length drafts over several years. A course taught by then-enfant terrible editor Gordon Lish awoke her to a new way into the story.

“At the end of that you learned that writing was the most important thing in your life and the words were a building block of the sentence…And it didn’t matter what you wrote — the minute you thought of someone else reading it or started weighing it against somebody else you might as well toss it away, so I tossed it away, I started all over again, although I had to still send it out 13 times before it finally did get published, and that excruciating experience brought me to the world of prose.

“I’m not one of those people that sits down and all the words come out right. Each of my novels seems to take 10 years from the beginning to the end, overlapping of course. I continue to go back to them. But some of my poems take that long, too.”

She’ll talk shop with Timothy Schaffert at An Evening with Terese Svoboda on Oct. 15 at 7 p.m. at Kaneko.

Shukert, along with fellow writers, will share thoughts about craft during a 2-5 p.m. salon at the library earlier that day.

“I’m happy to talk about process but I always do it with the caveat that I don’t expect it to actually be helpful to anybody. It’s not a formula,” says Shukert. “Very often people ask questions like, How do you do it? and the implication is, How can I do it? or How do I get a book published? or How do I finish my novel? And that’s the one thing nobody else can answer for you. Very early in your career it can be helpful to hear the way other people did it because you need to keep telling yourself it’s possible, it can be done.”

While Svoboda insists her process is not appreciably different writing novels than it is poems, Shukert says, “I find my process alters depending on what I’m working on. Like my process writing a book is very different than my process writing a play or a screenplay. My process writing fiction — now that I’m working on my first novel — is very different than the memoir process. It’s a lot slower. Switching from first person to third person has been interesting, especially as pertains to point of view.

“There are things that get easier and then things that get harder. I feel I have a much easier time, for example, just sitting down and writing and not being intimidated by the sheer scope of it. It’s a much more practiced muscle. But that doesn’t mean what I write right away is better.”

Rachel Shukert

Writing is one thing. Getting published, another. Conventional publishing is still highly competitive. Self-publishing though is within reach of anyone with a computer, tablet or smart phone. This democratization is the subject of a 11 a.m. Oct. 15 panel at the library and an Oct. 22-23 workshop at the Omaha Creative Institute.

Shukert says, “I feel like there’s more of an appetite to write than ever before but is there the same appetite to read? I feel, too, it’s about being able to cut through the noise. It’s one thing to publish your work, it’s another thing if anyone actually reads it or is able to find it.”

Yes, she says, self-publishing “does get voices heard that otherwise would not have been, but,” she adds. “there was a sort of curatorial process that I think is slowly falling apart. You want to know that what you’re reading is valuable. In a weird way I feel that attitude that anybody can be published, that I can publish this myself, oddly devalues the work of every writer. There’s still gotta be a way you can separate things. When there’s too much, there’s sort of too much.”

In the traditional publishing world, says Svoboda, an opposite trend finds “many more gatekeepers then when I started, or the gate has gotten a lot smaller, and so there are manuscripts in the world that deserve to get published that aren’t getting published. But I don’t know there would be that many more” (deserving manuscripts) now that the number of self-proclaimed writers has increased.

“The ability to publish so easily is probably a bad thing,” she adds. “Many people have stories and they are interesting stories but not everybody can write literature.”

Schaffert embraces this come one, come all new age.

“I think it’s a really great time to be a writer and I don’t think it’s yet necessarily interfering with the pursuit of the reader to find quality content. The stuff that the world responds to the world will still respond to and still find their way to. There are more ways to respond to the work you’re reading and more avenues to find new work thats more specific to your tastes. I mean, I think this is all great.

“If you’re sort of entrepreneurial by nature you can even venture to do for yourself what a conventional publisher might do, which is to promote your work, try to get attention for it…Even writers going through the old fashioned methods of publishing have added opportunities because you still have to promote your work. The world is your oyster.”

A 5 p.m. panel Oct. 13 at the library, moderated by blogger Sally Brown Deskins, will consider “the role criticism, arts profiles and cultural articles play in presenting artists and arts organizations to the community and to the world,” says Schaffert. “It seems to me every serious city needs serious coverage of what it’s doing. I think it’s integral there be writers we associate with coverage of the arts scene.”

Book design, objects in literature and fashion in literature are other themes explored in panels or exhibits.

An opening night reception is set for 6:30-9:30 at the library, Enjoy cupcakes, champagne and a pair of art exhibits.

For the complete Lit Fest schedule, visit omahalitfest.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.wordpress.com

Related articles

- Off the Shelf: Bohemian Girl by Terese Svoboda (nebraskapress.typepad.com)

- Getting to know: Terese Svoboda. (wewhoareabouttodie.com)

- Being Jack Moskovitz, Grizzled Former Civil Servant and DJ, Now Actor and Fiction Author, Still Waiting to be Discovered (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Author Rachel Shukert, A Nice Jewish Girl Gone Wild and Other Regrettable Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Summer Reading: The Coffins of Little Hope by Timothy Schaffert (homebetweenpages.com)

- When Safe Isn’t Safe at All, Author Sean Doolittle Spins a Home Security Cautionary Tale (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Rachel Shukert’s Anything But a Travel Agent’s Recommended Guide to a European Grand Tour (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Retired Omaha World-Herald military affairs newsman Howard Silber: War veteran, reporter, raconteur, bon vi vant, globetrotter

I have done my fair share of stories about journalists by now, and my favorites are generally those profiling venerable figures like the subject of this story, Howard Silber, who epitomized the intrepid spirit of the profession. Howard, though long retired, still has the heart and the head of a newsman. It’s an instinct that never fully leaves one. His rich career intersected with major events and figures of teh 20th century, as did his life before becoming a reporter. I think you’ll respond as I did to his story in the following profile I wrote about Howard for the New Horizons.

Retired Omaha World-Herald military affairs newsman Howard Silber:

War veteran, reporter, raconteur, bon vi vant, globetrotter

©by Leo Adam Biga

Oriignally published in the New Horizons

It’s hard not viewing retired Omaha World-Herald military affairs editor Howard Silber’s life in romantic terms. Like a dashing fictional adventurer he’s spent the better part of his 90 years gallivanting about the world to feed his wanderlust.

A Band of Brothers World War II U.S. Army veteran, Silber was wounded in combat preceding the Battle of the Bulge. Soon after his convalescence he embarked on a distinguished journalism career.

As a reporter, the Omaha Press Club Hall of Fame inductee covered most everything. He ventured to the South Pole. He went to Vietnam multiple times to report on the war. He interviewed four sitting U.S. Presidents, even more Secretary of States and countless military brass.

He counted as sources Pentagon wonks and Beltway politicos.

Perhaps the biggest scoop of his career was obtaining an interview with Caril Ann Fugate shortly after she and Charles Starkweather were taken into custody following the couple’s 1958 killing spree.

A decade later Silber caught the first wave of Go Big Red fever when he co-wrote a pair of Husker football books.

As Veteran of Foreign Wars publicity chairman he went to China with an American contingent of retired servicemen.

Even when he stopped chasing stories following his 1988 retirement, he kept right on going, taking cruises with his wife Sissy to ports of call around the globe. More than 60 by now they reckon. They’ve even gone on safaris in Kenya and South Africa. Their Fontenelle Hills home is adorned with artifacts from their travels.

In truth, Silber’s been on the move since he was a young man, when this New York City native left the fast-paced, rough and tumble North for the slower rhythms and time-worn traditions of the South. His itch to get out and see new places may have been inherited from his Austro-Hungarian Jewish immigrant parents.

Growing up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, Silber learned many survival lessons. HIs earliest years were spent in a well-to-do Jewish enclave. But when the Depression hit and his fur manufacturer father lost his business, the small family — it was just Howard, his younger sister and parents — were forced to move to “a less attractive neighborhood” and one where Jews were scarce.

As the new kid on the block Silber soon found himself tested.

“Fighting became a way of life. It was a case of fighting or running and I decided to fight,” he said. “I had to fight my way to school a few times and had to protect my sister, but after three or four of those fracases why they left me alone.”

Sports became another proving ground for Silber. He excelled in football at Stuyvesant High School, a noted public school whose team captured the city championship during his playing days. An equally good student, he set his sights high when he attempted to enroll at hallowed Columbia University.

“I wanted to go to Columbia as a student, not as an athlete,” he said. “They turned me down. I had all the grades but in those days most of the Ivy League and other prestigious schools had a quota on so many Jews they would admit per year.”

Columbia head football coach Lou Cannon offered Silber a partial football scholarship. The proud young student-athlete “turned it down.” The way Silber saw it, “If they wouldn’t take me as a student I didn’t want to go there as an athlete.'”

He said when the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa recruited several teammates he opted to join them. The school’s gridiron program under then head coach Frank Thomas was already a national power. Silber enrolled there in 1939.

At Alabama his path intersected that of two unknowns who became iconic figures — one famously, the other infamously.

“Paul “Bear” Bryant was my freshman football coach. I thought he was a great guy. He did a lot for me,” Silber said of the gravely voiced future coaching legend.

Paul “Bear” Bryant

The Bear left UA after Silber’s freshman year for Vanderbilt. It was several coaching stops later before Bryant returned to his alma mater to lead the Crimson Tide as head coach, overseeing a dynasty that faced off with Nebraska in three New Year’s bowl games. Bryant’s Alabama teams won six national titles and he earned a place in the College Football Hall of Fame.

Silber makes no bones about his own insignificant place in ‘Bama football annals.

“I was almost a full-time bench warmer,” he said. “The talent level was higher than mine.” He played pulling guard at 170 pounds sopping wet.

His mother wanted him to be a doctor and like a good son he began pre-med studies. He wasn’t far along on that track when the medical school dean redirected Silber elsewhere owing to color blindness. Medicine’s loss was journalism’s gain.

Why did he fix on being a newspaperman?

“I always had an interest in it. My environment had been New York and jobs were hard to get in those days and it just never occurred to me I would try for one. I was more interested in radio as a career. Actually, my degree is partly radio arts. I interned at WAPI in Birmingham and after three weeks I quit and went to work as a summer intern for the old Birmingham Post, a Scripps Howard paper, because it paid four bucks a week more. That’s how I got into print journalism.”

Silber became well acquainted with someone who became the face of the Jim Crow South — George Wallace. When he first met him though Wallace was just another enterprising Alabama native son looking to make his mark.

“George Wallace and I shared an apartment over a garage one summer school session,” recalled Silber. “I had known him a little bit before then. We became pretty good friends. There was no sign of bigotry at that time, and in fact I’m convinced to this day that his bigotry was put on for political purposes.

“He (Wallace) ran at one point for the (Alabama state) judiciary and his opponent was Jim Folsom, who later became governor, and he lost, and he made the comment, ‘I’m never going to be out-niggered again.'”

George Wallace

Years before Wallace uttered that comment Silber witnessed another side of him.

“We had our laundry done by black women in town. Their sons would come around the campus, even the athletic dorms, to pick up laundry. Tony, a big lineman from West Virginia, was always hazing them and finally George, who was on the boxing team, wouldn’t take it anymore and he went up to Tony ready to fight him, saying, ‘We don’t treat our people down here that way.’ I wouldn’t have wanted to get into a fight with him. He was a tough little baby.”

In 1968 the one-time roommates’ paths crossed again. By then Silber was a veteran Herald reporter and Wallace a lightening rod Alabama governor and divisive American Independent Party presidential candidate on a campaign speaking tour stop in Omaha. Wallace’s abrasive style and segregationist stands made him a polarizing figure.

“Wallace’s advance man Bill Jones was a mutual friend and because of Bill I was invited into Wallace’s plane as it was sitting on the ground and George answered some local questions. He seemed familiar with local politics and the local situation and he was interested in agriculture. We talked for a good 15 or 20 minutes.”

That evening at the Omaha Civic Auditorium Wallace’s inflammatory speech excited supporters and agitated opponents. A melee inside the arena spilled out onto the streets and in the ensuing confrontations between police and citizens a young woman, Vivian Strong, was shot and killed by an officer, setting off a civil disturbance that caused serious property damage and looting in Northeast Omaha.

In some ways Northeast Omaha has never recovered from those and other disturbances that burned out or drove away business. It’s just the kind of story Silber liked to sink his teeth into. Before ever working as a professional journalist Silber found himself, likes millions of others, caught up in momentous events that forever altered the course of things.

He was an undergraduate when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. The call to arms meant a call to duty for Silber and so many of the Greatest Generation. Boys and men interrupted their lives, leaving behind home-family-career for uncertain fates in a worldwide conflict with no guarantee of Allied victory.

“The day after Pearl Harbor hundreds of students went to the recruiting offices in Tuscaloosa, the university town. The lines were terrible and finally several days later I got in. I wanted to become a Navy pilot but I was rejected because I was partly color blind. So I just entered the Army.”

He was 21. He went off to war in 1942, his studies delayed button forgotten.

“The university had a program where if you finished the spring semester and had so many hours you could enter the armed services and finish your degree by correspondence,” said Silber, who did just that.

His military odyssey began at Fortress Monroe, Va. with the Sea Coast Artillery. “We had big guns to intercept (enemy) ships,” he explained. “Because I had some college I was put in the master gunner section where with slide rules we calculated the azimuth and range of the cannon to zero in on the enemy ships that might approach. The Sea Coast Artillery was deemed obsolete by the emergence of the U.S. Air Force as a reliable deterrent force.

“I was transferred to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, an anti-aircraft training center (and a part of the country’s coastal defense network). “I loved it down in El Paso. It was a good post.”

From there, he said, “I went into a glider unit and once in action we were supposed to glide in behind enemy lines to set up for anti-aircraft. Well, the glider unit was broken up. So I had some choices and I just transferred to the infantry. I went to Camp Howze (Texas), a temporary Army post, and became a member of company A, 411th Infantry Regiment, 103rd division. We did some pretty heavy training there,” said Silber.

“We went by train to Camp Shanks, New York — a port of embarkation. One morning with very little notice we were put aboard trains and transferred to a ferry stop in New Jersey and ferried across New York harbor to the Brooklyn Army Base,” he recounted. “There we boarded a ship that, believe it or not, was called the Santa Maria. We sailed to Southern France. It took about two weeks in a convoy strung out for quite a distance.”

Silber, whose descriptions of his wartime experiences retain the precision and color of his journalistic training, continued:

“We landed in Southern France (post-D-Day, 1944). We were equipped to go into combat but we were diverted to the Port of Marseilles. The French stevedores, who were supposed to be unloading ships of ammunition and such, went on strike. So we spent about two weeks unloading ammunition from ships to go up to the front.

“We were encamped on a plateau above Marseille. It was a happy situation. We’d be able to go in the city and enjoy ourselves.”

The idyll of Marseille was welcome but, as Silber said, “it ended soon enough. Part of the division went by truck and my regiment went by freight train with straw on the floor to a town called Epinal in Eastern France. From there we went into combat. The first day of combat eight members of my platoon were killed. A baptism by fire.”

That initial action, he said, “was in, oddly enough, a churchyard in which most of the graves were occupied by World War I German soldiers. I didn’t learn that until later.” Many years after the war Silber and his old comrades paid for a monument to be erected to the eight GIs lost there. He and Sissy have visited the site of that deadly encounter to pay their respects.

“It’s become kind of a shrine to guys from my old outfit,” he said.

The next phases of his combat duty exposed him to even more harrowing action.

Although wars historically shut down in winter or prove the undoing of armies ill-equipped to deal with the conditions, the record winter of ’44 in Europe ultimately did little to slow down either side. In the case of the advancing American and Allied forces, the treacherous mix of snow and cold only added to the miseries. When Silber and his fellow soldiers were ordered to cross a mountain range, the dangers of altitude, deadly passes and avalanches were added to the challenge.

“We fought our way through the Vosges Mountains in Alsace,” he said, adding cryptically, “We had a couple of situations…

“We were the first sizable military unit to cross the Vosges in winter. We had snow for which we were not equipped really. It turned out to be the worst in the history of that part of Europe. We didn’t have any white camouflage gear or anything like that that the Germans had. We met some pretty heavy combat in the mountains for a time. It was an SS outfit, but we managed to fight our way through.”

If any soldier is honest he admits he fears engaging in hand-to-hand combat because he doesn’t know how he’ll perform in that life or death struggle. In the Vosges campaign Silber confronted the ultimate test in battle when he came face to face with a German.

“I’ll tell you what happened,” is how Silber begins relating the incident. “We went out on patrol at night trying to contact the enemy and pick up a couple prisoners for intelligence purposes. By that time I had become a second lieutenant, courtesy a battlefield commission. I didn’t really want to become too attractive a target for the Germans, so I pretended I was still an enlisted man in dress and in emblem, and I carried around an M-1 rifle instead of a carbine.

“What often happened was the Germans might send out a patrol at the same time just by coincidence and we would kind of startle each other at the same moment and ignore each other purposely. That happened a lot and we thought it was going to happen this time, but they opened fire on us.”

In the close quarters chaos of the fire fight, he said, “I jumped into a roadside ditch with my M-1 and it was knocked out of my hand by the guy I killed. Had to. I had a trench knife in my boot and I attacked him with that and fortunately I beat him, or he would have beaten me.” Only one man was coming out alive and Silber lived to tell the tale. He does so without boast or pleasure but a it-was-him-or-me soberness.

A desperate Germany was sending almost anyone it could find to the front, including boys. The SS troop Silber dispatched was an adult, therefore, he said, “I didn’t have that to worry about on my conscience.”

“After that most of the units we encountered were made up either of young conscripts, and I mean below the age of 18, or middle aged men, as almost a last gasp. I saw German soldiers who couldn’t have been more than 12 or 13 years old. I also saw men in their 40s and 50s.”

This last gasp “was a hopeful sign” Germany was through, but he added, “We didn’t feel very comfortable fighting against 14 year olds. I mean, if we had to do it, we did it because they were trying to kill us. We lived with it, that’s all.”

Finally breaking out of the mountains onto the Rhine Plain was a great relief. For the first time since the start of the campaign, he said, “we got to sleep in an intact house. We proceeded around Strausberg. We were in the U.S. 7th Army and integrated into our army corps was the French 1st Army and they were made up mostly of North Africans. Most of them were Moroccans, Algerians and Tunisians, I guess. They had come across the Mediterranean with de Gaulle. We saw them from time to time. They had a reputation of being good fighters.

“We headed north paralleling the Rhine River and we were approaching the Maginot Line (the elaborate French fortification system Germany outflanked during its blitz into France). On December 14, 1944 we had orders to break through it. The Germans had artillery, some troops and some tanks zeroed in and ready to go.”

All hell then broke loose.

“We woke up one morning to the sound of artillery high above us, exploding in the trees,” recalled Silber. “We were on the side of a ravine through which a road had been cut and on that road was a tank destroyer outfit — using World War I leftover anti-tank guns. They were a platoon of African-Americans. The bravery those guys exhibited was unbelievable. When I think of it I become emotional because they were shot up to hell and kept fighting.”

His second close brush with death then occurred.

“The artillery action slowed down and we began to advance into the Maginot Line,” he said. “The Germans had some tanks positioned between fixed fortresses. We encountered off in the distance a tank — 400 or 500 yards away. It was very slowly approaching us. The tank destroyer outfit had been so decimated they were pretty much out of action, so we had bazookas. Our bazooka team in my platoon was knocked out. By that time I was the platoon leader. I picked up the bazooka, knelt and loaded it, fired once and missed. It was quite a distance still.

“The last thing I can remember is that tank lowering its beastly 88 millimeter cannon in my direction…I woke up the next day in an Army field hospital. Apparently the shell was a dud but its impact half buried me in my foxhole. Our platoon medic dug me out of the collapsed foxhole and got me out of the way. I was unconscious. Both my arms were broken and my left rib cage was pretty well beat up. I woke up December 16 and that was the day the Battle of the Bulge erupted about a hundred kilometers north of us.”

Silber spent the remainder of the war healing.

“The next day the field hospital was emptied out of patients and it moved north to take care of casualties from the Bulge,” he said. “I was shipped along with other patients by ambulance to the U.S. 23rd General Hospital at Vittel, France, a spa town. It had been a resort. It had a racetrack and a casino. We wound up in the grand hotel.

“Even though my arms were in casts by then I enjoyed being there, believe me.”

Ending up sidelined from the action, banged up but without any life threatening injury, reminded him of something he and his buddies often joked about to help pass the time.

“Especially when I was an enlisted man we used to sit and talk in our foxholes, usually at night when things were quiet, smoking a cigarette under a tarpaulin or something, about the ‘million dollar wound.’ We’d speculate on what it would take to get us back to the States without getting really hurt.

“Well, maybe I should be ashamed of this, but that was one of the things I thought of in the hospital — that I had kind of one of those (wounds). Except I was hurt a little more than I would have chosen.”

Back home, he continued mending at Rhodes General Hospital in Utica, New York. A restless Silber completed his college studies by correspondence and volunteered in the public relations office. He penned the script for a weekly radio show written, produced and acted by patients, mostly on war experiences, that the hospital sponsored. Silber shared in a George Foster Peabody Award for public service a show segment won. “It wasn’t my brilliant writing or anything,” he said, “but I was part of the process.”

He was still hospitalized when VJ Day sparked celebrations over the war’s end.

One of his PR tasks was delivering copy to the local Utica Daily Press, where he secured a job upon his discharge. “I took my swearing out ceremony as we called it at 10 o’clock in the morning and by two o’clock I was down there working for a salary, not much of a salary — $38 a week. I still have a soft spot in my heart for Utica. I actually was stationed in a bureau in Rome, New York 15 miles away.”

From there he returned to his old stomping grounds in the Big Apple, where he worked for the New York Sun. A plum early assignment put him in the company of Harry Truman, “the VIP who really impressed me most,” said Silber. “I rode his (1948) campaign train. I was pretty raw material then, a real cub reporter, but I got the assignment and I ran with it. I even got to kibbutz his (Truman’s) poker game.”

Silber recalls Truman as “very kind, although he’d pick on guys for fun,” adding, “He was just a pretty decent man but he had shall we say a frothy tongue.”

When the Sun folded in 1950 Silber got on with “a blue ribbon” PR firm, but as he once put it, “I just had the romance of daily journalism in my blood.” Thus he began searching for a newspaper job. His choice came down to a Kansas City paper and the Omaha World-Herald, and $5 more a week brought him here in 1955.

He started out on the rewrite desk.

The Herald had a team of reporters out covering the Charles Starkweather story but Silber was familiar with the mounting murders and resulting manhunt around the upper Midwest from rewriting field reports. Then, as things often happen in a newsroom, Silber found himself enlisted to cover a major development.

“When the Starkweather case broke, our chief photographer Larry Robinson, who was versed in aviation and friendly to some of the operators out at the air base, chartered a good airplane on standby. So when we got the word in the newsroom about Starkweather being captured in Douglas, Wyo., city editor Lou Gerdes pointed to me and said, ‘Go!,’ and I went with Robby and John Savage.”

“We got there ahead of anybody else outside the immediate area and because of that we were able to have a lot of informality that wouldn’t exist today. We got friendly with the sheriff, Earl Heflin, and his wife, the jail matron. We got some good stories.”

Minus a wire to transmit photos, Robinson flew back with the negatives, while Silber and Savage stayed behind to cultivate more stories.

That night, a keyed up Silber, unable to sleep, walked from the hotel to the courthouse where the captured fugitives were held.