Archive

Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Never is anyone simply what they appear to be on the surface. Deep rivers run on the inisde of even the most seemingly easy to peg personalties and lives. Many of those well guarded currents cannot be seen unless we take the time to get to know someone and they reveal what’s on the inside. But seeing the complexity of what is there requires that we also put aside our blinders of assumptions and perceptions. That’s when we learn that no one is ever one thing or another. Take the late Charles Bryant. He was indeed as tough as his outward appearance and exploits as a one-time football and wrestling competitor suggested. But as I found he was also a man who carried around with him great wounds, a depth of feelings, and an artist’s sensitivity that by the time I met him, when he was old and only a few years from passing, he openly expressed.

My profile of Bryant was originally written for the New Horizons and then when I was commissioned to write a series on Omaha’s Black Sports Legends entitled, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, I incorporated this piece into that collection. You can read several more of my stories from that series on this blog, including profiles of Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, and Johnny Rodgers.

Charles Bryant at UNL

Soul on Ice – Man on Fire: The Charles Bryant Story (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons and The Reader (www.thereader.com)

“I am a Lonely Man, without Love…Love seems like a Fire many miles away. I can see the smoke and imagine the Heat. I travel to the Fire and when I arrive the Fire is out and all is Grey ashes…

–– “Lonely Man” by Charles Bryant, from his I’ve Been Along book of poems

Life for Charles Bryant once revolved around athletics. The Omaha native dominated on the gridiron and mat for Omaha South High and the University of Nebraska before entering education and carving out a top prep coaching career. Now a robust 70, the still formidable Bryant has lately reinvented himself as an artist, painting and sculpting with the same passion that once stoked his competitive fire.

Bryant has long been a restless sort searching for a means of self-expression. As a young man he was always doing something with his hands, whether shining shoes or lugging ice or drawing things or crafting woodwork or swinging a bat or throwing a ball. A self-described loner then, his growing up poor and black in white south Omaha only made him feel more apart. Too often, he said, people made him feel unwelcome.

“They considered themselves better than I. The pain and resentment are still there.” Too often his own ornery nature estranged him from others. “I didn’t fit in anywhere. Nobody wanted to be around me because I was so volatile, so disruptive, so feisty. I was independent. Headstrong. I never followed convention. If I would have known that then, I would have been an artist all along,” he said from the north Omaha home he shares with his wife of nearly hald-a-century, Mollie.

Athletics provided a release for all the turbulence inside him and other poor kids. “I think athletics was a relief from the pressures we felt,” he said. He made the south side’s playing fields and gymnasiums his personal proving ground and emotional outlet. His ferocious play at guard and linebacker demanded respect.

“I was tenacious. I was mean. Tough as nails. Pain was nothing. If you hit me I was going to hit you back. When you played across from me you had to play the whole game. It was like war to me every day I went out there. I was just a fierce competitor. I guess it came from the fact that I felt on a football field I was finally equal. You couldn’t hide from me out there.”

Even as a youth he was always a little faster, a little tougher, a little stronger than his schoolmates. He played whatever sport was in season. While only a teen he organized and coached young neighborhood kids. Even then he was made a prisoner of color when, at 14, he was barred from coaching in York, Neb., where the all-white midget-level baseball team he’d led to the playoffs was competing.

Still, he did not let obstacles like racism stand in his way. “Whatever it took for me to do something, I did it. I hung in there. I have never quit anything in my life. I have a force behind me.”

Bryant’s drive to succeed helped him excel in football and wrestling. He also competed in prep baseball and track. Once he came under the tutelage of South High coach Conrad “Corney” Collin, he set his sights on playing for NU. He had followed the stellar career of past South High football star Tom Novak — “The toughest guy I’ve seen on a football field.” — already a Husker legend by the time Bryant came along. But after earning 1950 all-state football honors his senior year, Bryant was disappointed to find no colleges recruiting him. In that pre-Civil Rights era athletic programs at NU, like those at many other schools, were not integrated. Scholarships were reserved for whites. Other than Tom Carodine of Boys Town, who arrived shortly before Bryant but was later kicked off the team, Bryant was the first African-American ballplayer there since 1913.

No matter, Bryant walked-on at the urging of Collin, a dandy of a disciplinarian whom Bryant said “played an important role in my life.” It happened this way: Upon graduating from South two of Bryant’s white teammates were offered scholarships, but not him; then Bryant followed his coach’s advice to “go with those guys down to Lincoln.’” Bryant did. It took guts. Here was a lone black kid walking up to crusty head coach Bill Glassford and his all-white squad and telling them he was going to play, like it or not. He vowed to return and earn his spot on the team. He kept the promise, too.

“I went back home and made enough money to pay my own way. I knew the reason they didn’t want me to play was because I was black, but that didn’t bother me because Corney Collin sent me there to play football and there was nothing in the world that was going to stop me.”

Collin had stood by him before, like the time when the Packers baseball team arrived by bus for a game in Hastings and the locals informed the big city visitors that Bryant, the lone black on the team, was barred from playing. “Coach said, ‘If he can’t play, we won’t be here,’ and we all got on the bus and left. He didn’t say a word to me, but he put himself on the line for me.”

Bryant had few other allies in his corner. But those there were he fondly recalls as “my heroes.” In general though blacks were discouraged, ignored, condescended. They were expected to fail or settle for less. For example, when Bryant told people of his plans to play ball at NU, he was met with cold incredulity or doubt.

“One guy I graduated with said, ‘I’ll see you in six weeks when you flunk out.’ A black guy I knew said, ‘Why don’t you stay here and work in the packing houses?’ All that just made me want to prove myself more to them, and to me. I was really focused. My attitude was, ‘I’m going to make it, so the hell with you.’”

Bryant brought this hard-shell attitude with him to Lincoln and used it as a shield to weather the rough spots, like the death of his mother when he was a senior, and as a buffer against the prejudice he encountered there, like the racial slurs slung his way or the times he had to stay apart from the team on road trips.

As one of only a few blacks on campus, every day posed a challenge. He felt “constantly tested.” On the field he could at least let off steam and “bang somebody” who got out of line. There was another facet to him though. One he rarely shared with anyone but those closest to him. It was a creative, perceptive side that saw him write poetry (he placed in a university poetry contest), “make beautiful, intricate designs in wood” and “earn As in anthropolgy.”

Bryant’s days at NU got a little easier when two black teammates joined him his sophomore year (when he was finally granted the scholarship he’d been denied.). Still, he only made it with the help of his faith and the support of friends, among them teammate Max Kitzelman (“Max saved me. He made sure nobody bothered me.”) professor of anthropology Dr. John Champe (“He took care of me for four years.”) former NU trainers Paul Schneider and George Sullivan (who once sewed 22 stitches in a split lip Bryant suffered when hit in the chops against Minnesota), and sports information director emeritus Don Bryant.

“I always had an angel there to take care of me. I guess they realized the stranger in me.”

Charles Bryant’s perseverance paid off when, as a senior, he was named All-Big Seven and honorable mention All-American in football and all-league in wrestling (He was inducted in the NU Football Hall of Fame in 1987.). He also became the first Bryant (the family is sixth generation Nebraskan) to graduate from college when he earned a bachelor’s degree in education in 1955.

He gave pro football a try with the Green Bay Packers, lasting until the final cut (Years later he gave the game a last hurrah as a lineman with the semi-pro Omaha Mustangs). Back home, he applied for teaching-coaching positions with OPS but was stonewalled. To support he and Mollie — they met at the storied Dreamland Ballroom on North 24th Street and married three months later — he took a job at Brandeis Department Store, becoming its first black male salesperson.

After working as a sub with the Council Bluffs Public Schools he was hired full-time in 1961, spending the bulk of his Iowa career at Thomas Jefferson High School. At T.J. he built a powerhouse wrestling program, with his teams regularly whipping Metro Conference squads.

In the 1970s OPS finally hired him, first as assistant principal at Benson High, then as assistant principal and athletic director at Bryan, and later as a student personnel assistant (“one of the best jobs I’ve ever had”) in the TAC Building. Someone who has long known and admired Bryant is University of Nebraska at Omaha wrestling Head Coach Mike Denney, who coached for and against him at Bryan.

Said Denney, “He’s from the old school. A tough, hard-nosed straight shooter. He also has a very sensitive, caring side. I’ve always respected how he’s developed all aspects of himself. Writing. Reading widely. Making art. Going from coaching and teaching into administration. He’s a man of real class and dignity.”

Bryant found a new mode of expression as a stern but loving father — he and Mollie raised five children — and as a no-nonsense coach and educator. Although officially retired, he still works as an OPS substitute teacher. What excites him about working with youth?

“The ability to, one-on-one, aid and assist a kid in charting his or her own course of action. To give him or her the path to what it takes to be a good man or woman. My great hope is I can make a change in the life of every kid I touch. I try to give kids hope and let them see the greatness in them. It fascinates me what you can to do mold kids. It’s like working in clay.”

Since taking up art 10 years ago, he has found the newest, perhaps the strongest medium for his voice. He works in a variety of media, often rendering compelling faces in bold strokes and vibrant colors, but it is sculpture that has most captured his imagination.

“When I’m working in clay I can feel the blessings of Jesus Christ in my hands. I can sit down in my basement and just get lost in the work.”

Recently, he sold his bronze bust of a buffalo soldier for $5,000. Local artist Les Bruning, whose foundry fired the piece, said of his work, “He has a good eye and a good hand. He has a mature style and a real feel for geometric preciseness in his work. I think he’s doing a great job. I’d like to see more from him.”

Bryant has brought his talent and enthusiasm for art to his work with youths. A few summers ago he assisted a group of kids painting murals at Sacred Heart Catholic Church. He directs a weekly art class at Clair Memorial United Methodist Church, where he worships and teaches Sunday School.

Much of Bryant’s art, including a book of poems he published in the ‘70s, deals with the black experience. He explores the pain and pride of his people, he said, because “black people need black identification. This kind of art is really a foundation for our ego. Every time we go out in the world we have to prove ourselves. Nobody knows what we’ve been through. Few know the contributions we’ve made. I guess I’m trying to make sure our legacy endures. Every time I give one of my pieces of art to kids I work with their eyes just light up.”

These days Bryant is devoting most of his time to his ailing wife, Mollie, the only person who’s really ever understood him. He can’t stand the thought of losing her and being alone again.

“But I shall not give in to loneliness. One day I shall reach my True Love and My fire shall burn with the Feeling of Love.”

–– from his poem “Lonely Man”

Related articles

- A Family Thing, Bryant-Fisher Family Reunion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Green Bay Packers All-Pro Running Back Ahman Green Channels Comic Book Hero Batman and Gridiron Icons Walter Payton and Bo Jackson on the Field (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Bobby Bridger: Singing America’s Heart Song

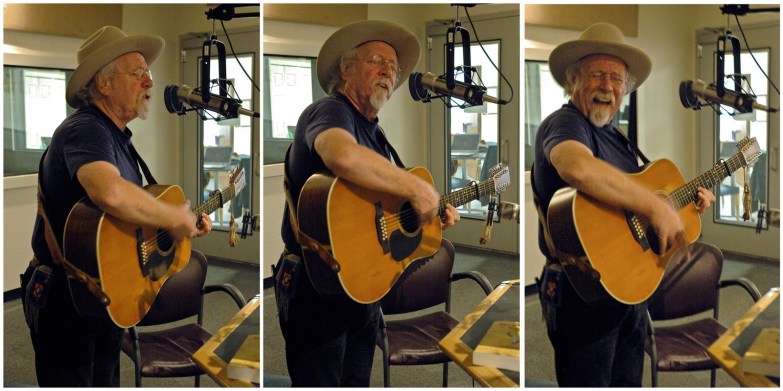

Among the most interesting figures I’ve written about is Bobby Bridger, a singer, songwriter, actor, author, and historian. His career arc has taken him from the heart of the Nashville and Los Angeles music scenes to a singular path as an epic balladeer of the American West. He’s perhaps best known today for his incisive writing about aspects of the American West that he’s become expert in. His books include A Ballad of the West, Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull: Inventing the Wild West, Bridger, and his latest, Where the Tall Grass Grows, Becoming Indigenous and the Mythological Legacy of the American West.

You’ll find other, more extensive stories I’ve written about Bobby and his fascinating life and career journey on this blog.

Bobby Bridger: Singing America’s Heart Song

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

When Bobby Bridger began doing his epic ballad thing in praise of mountain men, Plains Indians and Buffalo Bill, he was 24 and derided as a flake. He was told, Who wants a history lesson from a long haired folk singer clad in buckskins and beads? He was called crazy for walking from a multi-year/record deal at RCA. For researching cold trails from an obscure past. For performing a one-man acoustic show in a plugged-in era.

This unreformed hippie has always gone against the grain to forge a singular career path in search of, as the title of his forthcoming autobiography says, “America’s heart song.” His anachronistic journey has taken him from Nashville to Austin, where he resides and whose vital indie music center he helped form, to the Frontier West to Europe to Australia.

His three-part trilogy A Ballad of the West is the result of a lifetime’s work. Seekers of the Fleece recounts the mountain man era. Pahaska, the Indian name given William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, explores Cody’s relationship with Indians. Lakota focuses on Indian healer/mystic Black Elk, the subject of Nebraska poet John Neihardt’s classic epic Black Elk Speaks, whose Homeric couplets Bridger regards as a bible. Bridger describes Neihardt and Black Elk as “my two greatest teachers.”

For his 7:30 p.m. April 29 concert at the Omaha Healing Arts Center Bridger will perform Parts I (Seekers) and III (Lakota) from his own epic Ballad of the West.

Bridger’s 62 now and 40 years into his quest to forever fix the mythological West in ballad form. Time has made this once young upstart a graybeard figure not unlike those he writes and sings about. Bolstered by his acclaimed book Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull: Inventing the Wild West, he’s an authority on the West, albeit one without the imprimatur of a scholarly degree.

This frequent Western history presenter/panelist is giving two talks this weekend at the John G. Neihardt Center (Bancroft, Neb.), where he’s the poet/balladeer in residence. He courts controversy when the historian in him tells the “documentary truth” but the contrarian artist in him chooses the “emotional truth.”

“I’ve always approached this whole thing as if it’s a continuation of the Arthurian kind of legend in America,” he said. “Neihardt had only underscored that with his Homeric approach. I realize I’ve stumbled into something that’s so much bigger than me and so much grander than a career in country music…”

In exploring such figures as Jim Bridger (a distant relation), Hugh Glass, Black Elk and Cody, Bridger gives us the West writ large to counter the cynical view that’s gained currency and that he feels is due for a correction. “What we’re doing now is searching for a new interpretation of the hero,” he said. “Since the ‘50s we’ve been living in the age of the anti-hero. It’s like we had to trash the hero and completely drag him through the gutter and totally cynicize him in order to realize the mythological need for the positive hero in our culture and in our society.”

Bridger’s always felt his work’s tapped into an essential American story with deep reverberations to the historical Trans-Missouri region, the well-spring, as he sees it, of our national identity. He feels there’s much to “discover about who we are” in the pioneer and Native-rich past he perpetuates.

“The Trans-Missouri is where we invented our self when no one knew what it meant to be American. Since time immemorial the Lakota mythology sprang from the same region. If you go to Moscow or Sydney, Australia or Paris or Berlin…and somebody recognizes you as an American, soon the discussion goes to Native Americans — feather bonnets, teepees, peace pipes — all the accouterments of the Plains Indians. There’s a reason our mythology emerged from that region.”

He said from their struggles Native Americans offer “very vital knowledge for us of the future.” Their understanding of “the interconnectedness of things,” he said, can only help in a time of global warming and resource interdependence. Bridger is a conduit for such enduring wisdom. In him, the Old West lives anew. Just don’t call him a cowboy poet-singer. “That’s the quickest way to insult me,” he said.

Related articles

- Buffalo Bill’s Coming Out Party Courtesy Author-Balladeer Bobby Bridger (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

From the Archives: Conquering Cannes – Alexander Payne’s triumphant Cannes Film Festival debut with “About Schmidt”

From the Archives: Conquering Cannes, –Alexander Payne‘s triumphant Cannes Film Festival debut with “About Schmidt”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Omaha Weekly

Press accounts of Alexander Payne’s conquest of the Cannes Film Festival, where his new film About Schmidt created a buzz in the main competition, have largely focused on the film losing out on any awards or on the critical hosannas directed toward him and his star, Jack Nicholson.

But, as Payne noted during a recent Omaha visit, Cannes is a phantasmagorical orgy of the senses that cannot be reduced to mere prizes or plaudits. It is at once an adoring celebration of cinema, a crass commercial venue and a sophisticated cultural showcase. It is where the French bacchanal and bistro sensibilities converge in one grand gesture for that most democratic art form — the movies. Only a satirist like Payne can take the full, surreal measure of Cannes and expose it for all its profundity and profanity.

“I likened it to the body of super model Gisel (Bundchen),” he said, “which is extraordinarily beautiful and draped in the most elegant clothes on the planet, yet, also possesses…bile and all sorts of fetid humors inside of it. The festival is all of those things. I mean, one thing is the elegance — the red carpet, the beautiful tuxes and gowns, the fabulous beach parties and all that stuff. Another thing is the best filmmakers in the world showing work there.

“And still another side is the marketplace, which is like a bazaar, with people talking about how many videocassette units your film’s going to sell in Indonesia. It’s that kind of sordid marketplace that gives cinema its vitality. And you can’t have the cinema body without all of it. So, it’s really like a beautiful woman. It’s extraordinary to look at from the outside, but once you cut it and look inside, you could throw up.”

He said the confluence of glitz, glamour and garishness reminded him of Las Vegas. “It’s all kind of Vegasy. You see really elegant things and you see really tacky things, which I liked. I was in such a good mood, that I just loved everything.”

So, what do you do for an encore when your third feature film makes a splash at the mecca of world cinema? Well, if you’re riding a wave of success like Alexander Payne, your hot new film is next chosen to open the New York Film Festival (NYFF), September 27 through October 13, at Lincoln Center. “It’s an honor,” he said regarding Schmidt’s recently announced selection to open the Big Apple event. “That will keep the awareness of the film afloat. A lot of the New York press and international press and kind of the tastemaker-types will see it, I’m told.”

To be accepted as an opening night feature there, a film must be making its North American premiere, which forced New Line Cinema to decline invitations for Schmidt to play other major festivals on the continent, including those in Toronto and Telluride. No matter. The word-of-mouth momentum attached to Schmidt from its Cannes screenings is so strong that early industry patter is already positioning the film as an award-contending late fall release.

For the filmmaker, Cannes (May 15-26) marked a milestone in a still young career whose sky-is-the-limit ceiling has his work being compared to and his name being mentioned with the most celebrated cinema artists in the world today. An indication of his growing stature is the fact that during a recent Omaha visit he was shadowed by a New York Times reporter preparing a major profile on him. He fully recognizes, too, what Cannes means for his reputation, although the sardonic Payne points out the absurdity attending such puffery.

“It was a huge honor just to be there…and it’s a nice stepping-stone,” he said.. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s bigger than being nominated for an Oscar (he and writing partner Jim Taylor earned Best Adapted Screenplay nods for Election) because it’s international. It’s also really political and full of bullshit to some degree, but what isn’t? But given that reality of the world, it’s still about pure love of cinema, not Hollywood people slapping each other on the back and awarding movies like A Beautiful Mind. Ugh.”

YOU CAN READ THE REST OF THE STORY IN MY NEW BOOK-

Alexander Payne’s Journey in Film: A Reporter’s Perspective, 1998-2012

A compilation of my articles about Payne and his work. Now available for pre-ordering.

Related articles

- From the Archives: About ‘About Schmidt’: The Shoot, Editing, Working with Jack and the Film After the Cutting Room Floor (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne – Portrait of a Young Filmmaker (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: A Road Trip Sideways – Alexander Payne’s Circuitous Journey to His Wine Country Film Comedy (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: A Hollywood Dispatch from the set of Alexander Payne’s Sideways – A Rare, Intimate, Inside Look at Payne and His Process (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- When Laura Met Alex: Laura Dern & Alexander Payne Get Deep About Collaborating on ‘Citizen Ruth’ and Their Shared Cinema Sensibilities (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne, an Exclusive Interview Following the Success of ‘Sideways’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Alexander Payne Achieves New Heights in ‘The Descendants’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne Discusses His New Feature ‘About Schmidt’ Starring Jack Nicholson, Working with the Star, Past Projects and Future Plans (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha’s Film Reckoning Arrives in the Form of Film Streams, the City’s First Full-Fledged Art Cinema (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

From the Archives: About “About Schmidt”: The shoot, editing, working with Jack and the film After the cutting room floor

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Omaha Weekly

Ever since Omaha native Alexander Payne wrapped shooting on About Schmidt, the hometown movie whose star, Jack Nicholson, caused a summer sensation, the filmmaker has been editing the New Line Cinema pic in obscurity back in Los Angeles.

That’s the way Hollywood works. During production, a movie is a glitzy traveling circus causing heads to turn wherever its caravan of trailers and trucks go and its parade of headliners pitch their tents to perform their magic. It’s the Greatest Show on Earth. Then, once the show disbands, the performers pack up and the circus slips silently out of town. Meanwhile, the ringmaster, a.k.a. the director, holes himself up in an editing suite out of sight to begin the long, unglamorous process of piecing the film together from all the high wire moments captured on celluloid to try and create a dramatically coherent whole.

Whether Schmidt is the breakout film that elevates Payne into the upper echelon of American directors remains to be seen, but it is clearly a project with the requisite star power, studio backing and artistic pedigree to position him into the big time.

An indication of the prestige with which New Line execs regard the movie is their anticipated submission of it to the Cannes Film Festival. Coming fast-on-the-heels of Election, Payne’s critically acclaimed 1999 film that earned he and writing partner Jim Taylor Oscar nominations for Best Adapted Screenplay, Schmidt will be closely watched by Hollywood insiders to see how the director has fared with a bona fide superstar and a mid-major budget at his disposal.

Regardless of what happens, Payne’s unrepentant iconoclasm will probably keep him on the fringe of major studio moviemaking, where he feels more secure anyway. As editing continues on Schmidt, slated for a September 2002 release, Payne is nearing his final cut. The film has already been test previewed on the coast and now it’s just a matter of trimming for time and impact.

While in town over Thanksgiving Payne discussed what kind of film is emerging, his approach to cutting, the shooting process, working with Nicholson and other matters during a conversation at a mid-town coffeehouse, Caffeine Dreams. He arrived fashionably late, out of breath and damp after running eight blocks in a steady drizzle from the brownstone apartment he keeps year-round.

He and editor Kevin Tent, who has cut all of Payne’s features, have been editing since June. They and a small staff work out of a converted house in back of a dentist’s office on Larchmont Street in Los Angeles. Payne and Tent work 10 -hour days, six days a week.

“As with any good creative relationship we have a basic shared sensibility,” Payne said of the collaboration, “but we’re not afraid to disagree, and there’s no ego involved in a disagreement. We’re like partners in the editing phase. He’ll urge me to let go of stuff and to be disciplined.”

By now, Payne has gone over individual takes, scenes and sequences hundreds of times, making successive cuts along the way. What has emerged is essentially the film he set out to make, only with different tempos and tones than he first imagined.

“Rhythmically, it’s come out a little slower than I would have wanted it,” he said. “I think it’s been something hard for me and for those I work with to accept that because of it’s subject matter and for whatever ineffable reason this is a very different film in pacing and feel than the very kinetic and funny Election, which got so much praise. It has, I think, the same sensibility and humor as Election but it’s slower and it lets the drama and emotion play more often than going for the laugh. I think it just called for that. With this one, we don’t go for the snappy edit.”

Even before Schmidt, Payne eschewed the kind of MTV-style of extreme cutting that can detract from story, mood, performance.

“Things are over-covered and over-edited these days for my tastes. There’s many exceptions, of course, but the norm seems to be to cut even though you don’t need to. And, in fact, not only don’t filmmakers need to, their cuts are disruptive to watching performance and getting the story. I like watching performance. My stuff is about getting performance. I like holding within a take as long as possible until you have to cut.”

YOU CAN READ THE REST OF THE STORY IN MY FORTHCOMING BOOK-

Alexander Payne’s Journey in Film: A Reporter’s Perspective, 1998-2012

A compilation of my articles about Payne and his work. Available this fall as an ebook and in select bookstores.

Related articles

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne Discusses His New Feature ‘About Schmidt’ Starring Jack Nicholson, Working with the Star, Past Projects and Future Plans (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Conquering Cannes, Alexander Payne’s Triumphant Cannes Film Festival Debut with ‘About Schmidt’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: A Hollywood Dispatch from the set of Alexander Payne’s Sideways – A Rare, Intimate, Inside Look at Payne and His Process (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne – Portrait of a Young Filmmaker (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: A Road Trip Sideways – Alexander Payne’s Circuitous Journey to His Wine Country Film Comedy (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne, an Exclusive Interview Following the Success of ‘Sideways’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jim Taylor, the Other Half of Hollywood’s Top Screenwriting Team, Talks About His Work with Alexander Payne (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- When Laura Met Alex: Laura Dern & Alexander Payne Get Deep About Collaborating on ‘Citizen Ruth’ and Their Shared Cinema Sensibilities (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Alexander Payne Achieves New Heights in ‘The Descendants’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

From the Archives: Alexander Payne discusses “About Schmidt” starring Jack Nicholson, working with the iconic actor, past projects and future plans

From the Archives: Alexander Payne discusses “About Schmidt” starring Jack Nicholson

Working with the iconic actor, past projects and future plans

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Omaha Weekly

Citizen Ruth announced him as someone to watch on the independent film scene. Election netted him and his writing partner, Jim Taylor, an Oscar nomination for best adapted screenplay. The commercial success of Meet the Parents, whose script he and Taylor contributed to, led to another high profile hired gun job — a rewrite of Jurassic Park III.

Now, with About Schmidt, which began filming in his hometown of Omaha this week, filmmaker Alexander Payne finds himself playing in a $30 million sandbox in his own backyard and sharing the fun with one of the biggest movie stars ever — Jack Nicholson. It is the culmination of Payne’s steady climb up the Hollywood film ladder the past seven years. It has been quite a journey already for this amiable writer-director with the sharp wit and the killer good looks. And the best still appears ahead of him.

During an exclusive interview he granted to the Omaha Weekly at La Buvette one recent Sunday afternoon in the Old Market (fresh from seeing off his girlfriend at the airport) Payne discussed the genesis and the theme of his new film, his collaboration with Jack, his take on being a rising young filmmaker, his insider views on working in the American movie industry and his past and future projects.

Although About Schmidt gets its title from the 1997 Louis Begley novel, it turns out Payne’s film is only partly inspired by the book and is actually more closely adapted from an earlier, unproduced Payne screenplay called The Coward.

As he explained, “When I first got out of film school 10 years ago I wrote a script for Universal that had the exact same themes as About Schmidt…a guy retiring from a professional career and facing a crisis of alienation and emptiness. Universal didn’t want to make it. I was going to rewrite it and come back to Omaha and try and get it made, and then Jim Taylor and I stumbled on the idea of Citizen Ruth, so I pursued that and put this on the back burner. Then, about three years ago, producers Harry Gittes and Michael Besman sent me the Begley book, which has similar themes, although set in a very different milieu.”

Nicholson, who had read the book, was already interested. Payne first commissioned another writer to adapt the novel but that didn’t pan out. “I didn’t relate very much ultimately to the adaptation and then I turned to Jim Taylor and said, ‘You know that thing I was writing 10 years ago? How would you like to rewrite that with me under the guise of an adaptation for this thing.’” Taylor agreed, and the film About Schmidt was set in motion, with Gittes and Besman as producers.

Taking elements from both the earlier script and the Begley book, the character of Schmidt is now a a retired Woodmen of the World actuary struggling to come to terms with the death of his longtime wife, the uneasy gulf between he and his daughter, his dislike of his daughter’s fiance and the sense that everything he’s built his life around is somehow false. Full of regret and disillusionment, he sees that perhaps life has passed him by. To try and get his head straight, he embarks on a road trip across Nebraska that becomes a funny, existential journey of self-discovery. A kind of Five Easy Pieces meets a geriatric Easy Rider.

“What interested me originally was the idea of taking all of the man’s institutions away from him,” Payne said. “Career. Marriage. Daughter. It’s about him realizing his mistakes and not being able to do anything about them and also seeing his structures stripped away. It’s about suddenly learning that everything you believe is wrong — everything. It asks, ‘Who is a man? Who are we, really?’”

Typical of Payne, he doesn’t offer easy resolutions to the dilemmas and questions he poses, but instead uses these devices (as he used abortion politics and improper student-teacher activities in his first two films) as springboards to thoughtfully and hopefully, humorously explore issues. “I don’t even have the answers to that stuff, nor does the film really, at least ostensibly. But, oh, it’s a total comedy. I hope…you know?”

For Payne, who derives much of his aesthetic from the gutsy, electric cinema of the 1970s, having Nicholson, whose work dominated that decade, anchor the film is priceless. “One thing I like about him appearing in this film is that part of his voice in the ‘70s kind of captured alienation in a way. And this is very much using that icon of alienation, but not as someone who is by nature a rebel, but rather now someone who has played by the rules and is now questioning whether he should have. So, for me, it’s using that iconography of alienation, which is really cool.”

Beyond the cantankerous image he brings, Nicholson bears a larger-than-life mystique born of his dominant position in American cinema these past 30-odd years. “He has done a body of film work,” Payne said. “Certainly, his work in the ‘70s is as cohesive a body of work as any film director’s. He’s been lucky enough to have been offered and been smart enough to have chosen roles that allow him to express his voice as a human being and as an artist. He’s always been attracted to risky parts where he has to expose certain vulnerabilities.”

YOU CAN READ THE REST OF THE STORY IN MY FORTHCOMING BOOK-

Alexander Payne’s Journey in Film: A Reporter’s Perspective, 1998-2012

A compilation of my articles about Payne and his work. Available this fall as an ebook and in select bookstores.

Related articles

- From the Archives: About ‘About Schmidt’: The Shoot, Editing, Working with Jack and the Film After the Cutting Room Floor (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Conquering Cannes, Alexander Payne’s Triumphant Cannes Film Festival Debut with ‘About Schmidt’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne – Portrait of a Young Filmmaker (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Alexander Payne, an Exclusive Interview Following the Success of ‘Sideways’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: A Road Trip Sideways – Alexander Payne’s Circuitous Journey to His Wine Country Film Comedy (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jim Taylor, the Other Half of Hollywood’s Top Screenwriting Team, Talks About His Work with Alexander Payne (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- When Laura Met Alex: Laura Dern & Alexander Payne Get Deep About Collaborating on ‘Citizen Ruth’ and Their Shared Cinema Sensibilities (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Alexander Payne Achieves New Heights in ‘The Descendants’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Green Bay Packers All-Pro Running Back Ahman Green Channels Comic Book Hero Batman and Gridiron Icons Walter Payton and Bo Jackson on the Field

Green Bay Packers All-Pro Running Back Ahman Green Channels Comic Book Hero Batman and Gridiron Icons Walter Payton and Bo Jackson on the Field

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Green Bay Packers All-Pro running back Ahman Green has a well-publicized fascination with Batman. It makes sense considering the player applies the same old-school, no-frills style to his game as the comic book caped-crusader does to crime fighting. Instead of super powers, Batman gets by with well-hewn brain and brawn. Just like his favorite action figure, the former Omaha Central High School and University of Nebraska All-American, is all about the work. Gifted with size, strength and speed, Green’s worked hard honing himself into a chiseled, fluid dynamo. He is that rare combination of plower who won’t be stopped in short-yardage situations and burner who’s a threat to go the distance on every carry.

The same way Batman disdains trendy martial arts in favor of more basic ass whuppings, Green eschews any fancy moves on the field and, instead, sheds tacklers with brute force, cat quickness, superb balance and unerring instinct.

While his foes on the field may not be as maniacal as the Green Goblin, the NFL’s second leading rusher from a year ago confronts his own terrors in the form of bull rushing linemen, heat-seeking backers and hard-hitting corners. Green’s slashing style may deflect the full brunt of hits, but he still absorbs the force of a car crash every time he gets thrown down, blown up or taken out like a ten-pin. He just keeps on coming though, with a bring-it-on durability that’s his trademark.

And much like his alter ego has a dark side, Green does, too. He was charged with fourth-degree domestic assault against his first wife, who filed for divorce soon after the couple were cited for disturbing the peace in 2002. “I had a lot of stuff going on,” he told the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. “Outside of football I had to juggle a lot of things.” Besides dealing with problems at home, he struggled healing from a series of nagging injuries and finding time to complete his college studies at UNL. Then, last year he got his degree and found a new bride. There’s a sense that by dealing with his personal issues and getting well again, emotionally and physically, he set the stage for his record-setting, busting-loose 2003 performance.

Records are meaningful to Green in-so-far as they are a benchmark for his own progress. “That’s important to me because if a person doesn’t set goals, where are they going? I keep setting goals. After I knock ‘em out, I put another one in and I just keep going. That’s it.” Coming from the tradition-rich Nebraska program made his adjustment to the storied Packers franchise a little easier. “It was kind of old-hat by the time I got here,” he said. “I know what’s happened here in the past and I’m like, Let’s make some new history and let’s roll.”

After a slow start in the NFL with Seattle, where he was never given a chance to be an every down back, he’s evolved into the league’s prototype workhorse. An average game now finds him lugging the ball from scrimmage 20 or more times and catching three or four passes out of the backfield, not to mention all the times he’s called on to block. With a maturity that belies his age, Green is putting the team on his back and taking a pounding, while dealing out some serious hurting, too. It’s just the way he did it as a junior at NU, when he had more than 2,200 combined yards on 300-plus touches (counting bowl stats). With his luxury package design of power and explosiveness, he’s dominating the field again, only against the best players in the world. Taking on such a big role doesn’t faze him. “I don’t even look at it as that. I don’t worry about what’s on my shoulders or what’s not. I just go out there and play football. Whatever happens, it happens. That’s it,” he said.

Erased now is the tag of fumbler that dogged him from Seattle and that surfaced last year when he had trouble holding onto the ball. “Oh, yeah, it’ll probably never be forgotten, but it’s behind me. It’s definitely behind me. But some people never let stuff go,” he said. “I just go out there and play every game knowing that stuff can happen. That’s just part of football. You’re competing. It’s a back and forth battle. You’re not going to have a perfect game. Well, I don’t want to say never.”

That he remains productive and healthy carrying such a heavy load defies the odds and speaks not only to his good fortune but to his great work ethic. His penchant for paying the price with grueling workouts in the off-season is something he took from his real-life idol, Walter Payton, a righteous back Batman would have loved. The late-great Chicago Bear was renowned for his toughness on the field and his extreme conditioning drills off it that culminated in running, full out, a hell hill few dared testing and fewer yet conquered.

“What I do when I am working out, whether lifting weights or running, is I push myself to the end, to where I ain’t got nothing left,” Green said. “That’s what Walter Payton did when he worked out during the off-season. The intensity of his off-season workouts was higher than any training camp or game. He pushed himself harder than anybody else did, so that when the season came along he was in top shape and he didn’t worry about being tired or getting hurt.”

To give himself that same edge, Green religiously pumps iron and runs stairs until his muscles and lungs burn. “If I’m going to be in the right kind of shape, I’ve got to make sure I have my butt in the weight room lifting weights — getting stronger, bigger, faster — because if I don’t I’m going to start getting hurt” and wearing down, he said. “I’m trying to find a hill to run the way Walter Payton did.”

Payton also embodied the warrior figure Green sees himself as. Growing up in L.A., where he lived before returning to his native Omaha for high school, Green adopted a style Sweetness made famous. “He was the kind of runner I was. I was scrappy. I never went down easy. I was just tough. That was something I learned out in L.A. because, you know, you have to be tough to get along in this sport, especially there, where the competition’s real high. And that was the way my idol ran. He ran tough. He didn’t die easy. He was just the type of running back I Iike.” For his pre-game inspirational ritual, Green watches the Pure Payton highlight tape.

Bo Jackson was another back he patterned himself after. “He was blessed with the ability. He was fast and he was big and he took that and he ran very hard with it.”

The legendary feats of Payton-Jackson and the mythic heroics of Batman aside, Green’s work ethic springs from a more prosaic source, his parents, Edward and Glenda Scott. “My parents were older, and with that I developed that work ethic that if I want something I’m going to have to work for it — it’s not going to be given to me,” he said. “And some days it’s going to hurt, but if you really want it, you’ve got to fight through the hurt, fight through the pain, fight through the sweat, the blood and the tears to get where you want to be. And that’s how I think.”

If he could, Green said he would incorporate into his regimen a drill that simulates the hits he takes during a game. “I wish I could, because that would be my workout every single day of the week, but you can’t. You can’t imitate a football game.”

Getting himself ready to weather the hits and the upsets of a pro football career is all about focus, he said. “My philosophy on life is, just attend to the things you can control like your body. I control my body. I control what goes into my body. With my job, I’ve got to make sure I’m eating the right foods and that I’m in the right kind of shape. Anything on the outside — the stuff that you don’t hold in your hand and that you can’t control — don’t worry about it.”

Consistent with this no-nonsense approach is Green’s grounding in the fundamentals of the game. “I was fortunate to have a line of good coaches that taught me the basics. That’s the biggest thing,” he said. “Once you get taught that at an early age, everything else will come easier and you’ll be able to excel faster just by knowing the fundamentals of your sport.”

Green got his football start playing in Los Angeles midget leagues. He said the talent pool there steeled him for his return to Nebraska. “I played pretty well and I knew if I could survive out there, which I did, I could come out pretty good in high school ball here.” Once back in Omaha, where he lived with his grandma, he made his first splash on the local gridiron starring for the North Omaha Bears, which he helped lead to the 1991 national youth football (ages 13-14) title in Daytona, Florida. He began his prep career at North High, playing little as a freshman before starting on the varsity as a sophomore, when he ran for more than 1,000 yards. Two decades earlier his uncle, Michael Green, ran roughshod for North.

Ahman then heeded the wishes of his mother to attend her alma mater, Central, where he transferred prior to his junior year. He said switching schools was more about honoring his mom than any dissatisfaction with North or any desire to join Central’s fabled roster of running backs. “My mom wanted me to graduate from the high school she graduated from as a keep-it-in-the-family type thing.”

As far as Central’s rich tailback legacy, he said, “I wasn’t really into it. I just knew from the year before they had a guy — Damion Morrow — running the ball real good. I knew he was there, but I didn’t know all the other running backs that came out of there, like Calvin Jones, Leodis Flowers and Keith Jones. There’s been a long line of running backs there that I didn’t know about till I got there.” One name he did hear growing up was Gale Sayers, who set an exceedingly high bar for the Eagles’ running back tradition by earning All-America honors at the University of Kansas and NFL Hall of Fame status with the Chicago Bears.

Since then, Central’s become a prime feeder of college football talent. Its pipeline of talented backs dates back to at least the late ‘50s with Roger Sayers, the older brother of Gale. The Brothers Sayers even played one season together (1960) in the same backfield. Long overshadowed by Gale, Roger was a top American top sprinter and a spectacular small college back-kick returner for then-Omaha University.

Distinguished Central backs of more recent vintage include ex-NU stars Joe Orduna (Giants, Colts), Keith Jones (Browns, Cowboys), Leodis Flowers and Calvin Jones (Raiders, Packers) and current Husker David Horne. There was also Jamaine Billups, who switched to defense at Iowa State. And there were guys with brilliant prep resumes who, for one reason or another, never duplicated that success in college. Terry Evans was one. Damion Morrow, another. After an unprecedented sophomore year in which he ran for more than 1,700 yards, Morrow shared the ball with Ahman Green his last two years at Central, when each topped 1,000 yards. The pair are on a short list of backs in Nebraska 11-man prep football history to ever rush for 1,000 or more yards in three seasons.

According to Green, Morrow was “an awesome back” and just one of many “great athletes” he was around while coming up in Omaha. “Just pure athletes. Some of them didn’t get the opportunities that I got. Damion Morrow, Ronnie Doss. Zanie Adams. Stevie Gordon. The list goes on and on.” Green is well aware of his hometown’s considerable athletic tradition and brags on it whenever he can. “I’m always defending Omaha here in Green Bay,” he said. “They’re like, ‘Who else is from Omaha?’ I tell ‘em. ‘Ya’ll just don’t know that we’ve got a great line of athletes. Not just from football, but from all other sports.’”

Knowing he’s now considered in the same company as Omaha’s athletic elite — with legends Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers — makes him “proud,” he said, “because those are names I heard about and how great they were. I’m just proud, because it goes to show that my hard work has paid off for me and is continuing to pay off for me and my family.”

With most of his family still in Omaha, Green gets back often and stays active in the community. “I do a lot of stuff with the North Omaha Boys and Girls Club,” he said. “Just recently, we had our third annual high school all-star basketball night, where we had men’s and women’s games, a three-point shootout and a dunk contest.” And in that way things have of coming full circle, he will soon be teaching football basics. “This summer I’m having my first Ahman Green Youth Football Camp, for kids 8 to 14. It’s a non-contact camp for boys and girls where I teach the fundamentals.” The June 28 and 29 camp is at North High School.

After his break-out 2003 season, Green’s fame is on the rise but his ego is not. “I haven’t changed. I’m still that little kid that grew up in Los Angeles and that was born in Omaha. If you talk to my family members, they’ll tell you — I’m still Ahman.”

Coming off his monster year, when the 10-6 Packers added a wild card win before being knocked out of the playoffs by Philadelphia, Green feels the club is ready for a title run. “We’ve got the tools in line to do big things,” he said.

Heading into his seventh NFL campaign, he knows he’s in the prime of a career that also has its limits. The end isn’t in sight yet, but he knows it’s only a matter of time. “I think about it,” he said, “but it’s something where I just play it by ear, like I always do. My body will let me know if I’ve had enough. I’ll listen to that. I’ve been listening to it for awhile now. When my body says it’s enough, it’s enough.”

Any talk of walking away from football is premature as long as he stays healthy and keeps producing. Then there’s the elusive perfect game he feels may not be so impossible, after all. “I just go into every game knowing I’m going to give it my best that day for my team. Who knows? It might happen. I might have a perfect game.” KAPOW. BAM. ZOOM. No. 30 saves the day again for Gotham City, er Green Bay.

Related articles

- Ahman Green officially retires (profootballtalk.nbcsports.com)

- Green Bay Packers: Does 19-0 Season Make Them the Best Team in NFL History? (bleacherreport.com)

- 2011 Green Bay Packers and the 10 Best Teams in NFL History (bleacherreport.com)

- Lettermen In The News: Ahman Green Joins Big Ten Network (lostlettermen.com)

Louise Abrahamson’s legacy of giving finds perfect fit at The Clothesline, the Boys Town thrift store the octogenarian founded and still runs

Even though I know better, I sometimes find myself making assumptions about people based solely on their appearance. Pint-sized octogenarian Louise Abrahamson didn’t look like my idea of a dynamo not to be trifled with when I first laid eyes on her but as I soon discovered that’s exactly what she is. This sweet little old Jewish lady has been running, variously with an iron fist and a velvet glove, a thrift shop at the Catholic run Boys Town for decades now and she shows no signs of slowing down. This story of a Jew deeply embedded at Boys Town reminded me of the deep relationship that Boys Town founder Father Edward Flanagan enjoyed with Jewish attorney Henry Monsky – a story I wrote about and that you can find on this blog. While Monsky’s contributions were more advisory, legal, and monetary, Louise’s are more cultural, charitable, and practical. My story about Louise that follows originally appeared in the Jewish Press.

Louise Abrahamson’s legacy of giving finds perfect fit at The Clothesline, the Boys Town thrift store the ocotgenarian founded and still runs

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Jewish Press

Eighty-nine years ago, Omaha Jewish leader Henry Monsky befriended an Irish Catholic priest with whom he shared a dream of creating a safe haven for troubled youths. The priest found a site, but lacked funds. Monsky, a successful attorney and inveterate do-gooder, lent Rev. Edward Flanagan $90 for the first month’s rent on the original Boys Town building in downtown Omaha. Besides serving, pro bono, as attorney for both the home and the late Fr. Flanagan, Monsky was a member of the Boys Town board of directors from its 1917 inception until his death in 1947. His support of Fr. Flanagan and the youth care program got other civic-business leaders to follow suit. The rest is history. As Boys Town’s approach to serving at-risk children caught on, donations poured in and the organization expanded. Now, it’s become a much replicated national model and the names Fr. Flanagan and Boys Town are synonymous with youth care worldwide.

The role Monsky played in the then-fledging institution’s founding is even portrayed in the 1938 Oscar-winning film Boys Town.

Twenty-six years ago, an Omaha Jewish woman named Louise Abrahamson, a former legal stenographer, small business owner, retailer, grant writer, fundraiser and political advisor, got the idea of starting a thrift shop to outfit children at the home with new clothes and things. At the time, she was a secretary and much more at Boys Town. Struck by how little new arrivals had in the way of clothes or other possessions, she took it upon herself to solicit donations from clothing and sundry manufacturers. Donated goods began arriving at her home and were stored in her garage. She distributed the gifts to Boys Town residents and to other organizations helping families and children. Before long, the operation outgrew her garage and moved to new quarters on campus.

Today, she operates out of a retail store-like setting called The Clothesline. The volume of goods that comes in year-round is enough to keep the store’s neatly dressed shelves, bins and racks filled and to take up floor-to-ceiling sections of a warehouse storage area. At any given time the inventory — a typical shipment contains hundreds or thousands of items — includes everything from apparel to accessories to toiletries to toys. Each box must be unpacked, sorted and labeled. In 2005 alone she collected merchandise worth a combined commercial value of $1.3 million, a record year. And that’s only counting donations of $1,000 or more.

There, she applies her well-practiced people skills and business acumen — “I’ve done a lot of things in my life” — to sweet talk corporations out of in-kind gifts and to ease the transition displaced kids face miles away from home. All her considerable time on the project is given as a volunteer.

More than just a place where children get a new set of duds, The Clothesline is where kids find a friend in Abrahamson they can always confide in.

“She is so wonderful to all these kids. When they come in they get a hug and kiss,” said Betty Rubin, a friend and fellow volunteer at the store. “This is what makes it tick — the warmth of it. I mean, it’s very personal to her.”

“Louise is one of those rare people who flourishes by helping others,” said Fr. Val Peter, recently stepped down as executive director of Girls and Boys Town. “Her joy is in giving to others. She is an expert at human relations. She can talk major manufacturing reps into helping us and she has a way with the kids, too. She is an enormously happy person, and to be that happy you have to work at it.”

“This is my life,” Louise said by way of explaining why, at age 86, she still works at the store four days a week. “I get a lot of pleasure out of this. It’s just kind of a challenge to see if people remember me and send me stuff I ask for for the kids.”

Besides, the need that inspired her to start the store in the first place, is still there. Then, like now, newcomers arrive with few possessions and little trust. If anything, she said, kids today present “a lot more problems than when I first came here. I have just taken it into my heart to care about the kids. Generally, when they come in, I don’t settle for a handshake. I have a hug. I want them to know I truly care what happens to them. That, to me, is what sets the pace for a youngster. Rather than have them feel like a stranger or a truant, I want them to feel welcome,” said the former Louise Miller, an Omaha native and Central High graduate. “That’s why I tell them, ‘We want you here. It’s a great place to be. Make the most of it. If you take advantage of what we offer, we’ll never let you down.’ I love that about Boys Town. I like what we do for children.”

“Louise is a great ambassador for those kids,” Girls and Boys Town Public Relations Director John Melingagio said. “She manages to take some of the fear and anxiety away for them.”

On a typical day at the store, the pint-sized Abrahamson, crisply-attired in a pants and sweater suit and her hair nicely coiffured, is seated at her command center at the front of the shop, her phone, computer and files within easy reach. An adult man saunters in with a teenage boy trying hard to suppress his unease. The man’s a campus family teacher and the youth a newbie in need of threads to replace the banned gang clothes he’s come with.

She greets the teen. “Good morning. How are you?” He says, “What’s up?” “And you are?” “Tavonne,” he tells her. “Where you from?” “Baltimore.” “Baltimore, well you know cold weather then. You just pick out what you want, bring it up here and we’ll check it out. That’s all there is to it,” she explains.

A few minutes later, after trying on some pants, shirts and shoes, Tavonne’s back. Louise asks him, “Did you find what you’re looking for?” “Yeah.” “So now you’re all fixed up with dress clothes, right?” “Yeah.” “That’s good. How long have you been here?” “This is my second day.” “Second day, you’re an old-timer.” He smiles shyly. “Probably by the end of next week you’ll be sworn in as a Boys Towner. We’re glad to have you here.” The boy, warming to her, replies, “Thank you.” She tells him, “We hope you do well. It’s a great place to be. Now, I have these…if you want a watch,” she says, pushing a basket filled with nice men’s watches near him. He fishes through the bunch and finds one he wants. “I like this one.” “It’s yours.” “Thank you, I appreciate it.” “You’re very welcome. I want to wish you a merry Christmas.” “Same to you.” “And I hope things work out for you, dear.” “Thanks.”

It’s this kind of human exchange that keeps Abrahamson coming back day after day. “Yeah, that tells a story,” she said. “We get a lot of new kids in this time of year. Family teachers will come in with new children, most of them with little or no clothes other than what they have on their back. All our clothes are new and appropriate to wear at church and school. The kids pick out what they want.”

She said her empathy for them extends back to her own childhood. “I knew my folks loved me, but they were busy making a living and really didn’t have much time for me. I was lonesome. I needed somebody I thought cared. And I think that’s why I feel a special need to help children,” she said.

It was while working as a secretary in Boys Town’s Youth Care program she saw first hand the want and conceived the idea of a free clothing center. She got it up and running out of her home in no time.

“I’d see these unhappy youngsters come in carrying a grocery sack and I’d say, ‘Where’s your luggage?’ They’d say, ‘This is it.’ My husband and I used to be in retail — we had a shoes and clothing store — and I wondered if I called on our old dealers, would they help and send me what they have. So, those were the first people I wrote to. They were very giving and began sending merchandise to me.”

With the chutzpah all doers possess, she just thought it up and went ahead. “I did this strictly on my own. I didn’t ask anybody’s permission. I just started doing it,” she said. “Once I’d get the merchandise in, I’d open up the boxes and I’d send out a memo and invite the family teachers and the kids to come over my house.”

By then, Louise and her late husband of 58 years, Norman Abrahamson, lived alone. Their two sons, Hugh and Steve, were grown. She credits Norman for her success. “He taught me everything I know. He taught me how to greet people. He taught me how to go for the product. He taught me that being kind is unusual. He was very supportive. He encouraged me. He said, ‘Go for it, honey. You can do it.’ He was there when I asked for advice and when I faltered.” A former Edison Brothers shoe salesman, he opened his own retail men’s apparel and shoe stores, Hugh’s. He later became a real estate builder-developer.

Soon, the amount of donations was too much for the couple’s garage. “My husband said, ‘Don’t you think Boys Town would give you a spot?’ So, I went to Fr. Hupp (the late former executive director of Boys Town), who knew I was inviting the teachers and kids over to my house to get clothes, and he said, ‘We’ve got space down in the boiler room (of the Youth Care building). Can you hack that?’ ’Any place would be good,’’ I said. So, we had our stuff delivered there, and this is pretty much the way it started.”

She wore a mask to protect against fumes in the cramped boiler room. It was under Fr. Peter’s watch the operation moved from that dank place to its pleasant environs today — in the building that houses the U.S. postal station on campus.

“When Fr. Peter came aboard, we just went on from there. He and I worked very closely, especially at Christmas-time. The store grew and grew, as did the demand.”

She’s done it almost entirely on her own, too, running things the way she sees fit. “There’s nobody that’s been put here to watch me.”

Generations removed from Henry Monsky helping make the dream of Boys Town a reality, fellow Jew Louise Abrahamson is helping Boys Town fulfill its nonsectarian mission of providing a caring environment to homeless and abused children of all faiths and creeds. She’s familiar with Monsky’s legacy, too, as she helped organize a touring Nebraska Jewish Historical Society exhibit on him in collaboration with Boys Town. Fr. Peter said that if Monsky is the grandfather of Boys Town, then Abrahamson is “the grandmother. She is loved and appreciated here.”

Playing the role of matriarch to kids with severed family relationships appeals to her. “While they’re here, I am like their grandmother,” she said. “A lot of the young people come in and tell me their problems, and I’ll listen very carefully. They’re welcome to come in anytime. They don’t have to make an appointment.”

Her contact with the children often extends well past their graduation and departure from the home. “Even two or three years later,” she said, “kids can have hard luck. I’ll get a call that says, ‘Louise, so and so is going out on a job interview and doesn’t have a thing to wear.’ And I’ll say, ‘Send ‘em over.’ Now, where else can you go and get that kind of a feeling that you’re needed and wanted?”

The ties go well beyond that. Her desk at the front of the store displays photos sent by former Boys Town students, many pictured with families they’ve begun. She exchanges cards and letters, just like any good grandma does. “I keep in touch with a lot of the children after they leave,” she said.

Just don’t assume her kindly ways and diminutive stature mark her as a pushover.

“Louise is a very pleasantly, disarmingly assertive little old lady,” said Dan Daly, Girls and Boys Town’s Vice President and Director of Youth Care. “You see this pleasant looking, smiling, tiny person and pretty soon she’s got her hand in your right back pocket. That’s how Boys Town was founded. Her and Fr. Peter, made a very, very potent tandem. He knew what kind of talent she has at doing this sort of thing and he was very supportive of her. It’s grown and proliferated because of her personality and her keen business sense.”

So savvy is this nice little old Jewish lady in sizing up people, Daly said, that he and other Boys Town officials would steer family teacher candidates by her desk, so she could observe them. Her assessment factored into new hires. Her counsel was also sought ought off-campus by candidates for mayor, governor and senator. She even wrote a booklet to help prospective candidates weigh bids for public office.

Using her political skills, she routinely contacts corporate giants like Target, Wal-Mart, Dillards, Lands-End, Johnson & Johnson and Colgate, and gets them to donate surplus items. Her personal appeals, scripted herself, are laced with tug-on-your-heart pathos and practical let’s-do-business talk. She tells them, “We have so many young boys and girls who…desperately need clothing…I am asking for your help. If you have any donation department of your discontinued styles, over-stocks, irregulars or out-of-season merchandise, could I ask that you place us on your recipient list? Any merchandise sent can be a tax write-off…Thank you. I hope you will share in Boys Town’s grand mission.”

She doesn’t stop there, either. She follows up with phone calls and letters, always gently reminding potential donors of the need. Her persistence often pays off. “I’m after them all the time. I don’t take no for an answer. I keep pitching, and pitching kindly.” Every donor receives a personal thank you note from her.

Melingagio said the donations she brings in help Boys Town “leverage our dollars. Those in-kind gifts she gets from corporations allow the monies we get to go to things that help the kids get better.”

When she approached Fr. Peter with her concept for the store, he embraced it. “I knew that if we let Louise loose at The Clothesline, that it would become very big,” he said. “The best thing to do is to let Louise do her work. She does it better than anyone else.” He said the store’s proved a winning venture. “Oh, yes, it’s a great idea. We needed it badly. It helps everybody. The best ideas come from people like Louise who have talent and a willingness to make their ideas successful.”

He added there’s never been any thought of taking it out of her hands. “It has been Louise’s baby from the get-go. What we do here is we give people a job and say, You’re in charge of making it a success, and she’s made it a success. We’re all proud of her.” He confirmed there’s also been no talk of what will happen once she’s gone. “We don’t want to think about that. We tell her, Take your vitamins. Stay healthy. We need you for years to come. She’s it.”

Daly said Abrahamson is quite adept at “networking with family teachers. She alerts people when new stuff comes in. She’s always pushing the product, so to speak. Louise has her favorites. If she gets something in that she knows one little girl would like, she makes sure that little girl gets the first crack at it.” He said it’s not only the 500-some kids on campus who benefit from the fruits of her labor. Another 200 or so in foster care settings also have dibs on what she collects. When supplies or shipments exceed the Boys Town demand, she places the extra goods with places like The St. Francis House and the Salvation Army.

Her office is also the base for a whole other category of gifts she acquires for children. Daly said she manages to get kids passes to movies, concerts, athletic events, skating rinks and many other activities. She gets donated food for parties. She ensures every Boys Town resident has gifts at Christmas and graduation. “It’s a lot bigger than just The Clothesline,” he said.

Service to others is a lifelong habit. Whether advising politicos such as Kay Orr and Hal Daub, or helping run their campaigns for public office or volunteering with the American Red Cross, the Arthritis Foundation, the March of Dimes, Hadassah, the Special Olympics and the United Way or serving as a member of the credit committee of the Boys Town Federal Credit Union or as president of the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society, she gives her time in many ways.

Then there are the two years she devoted to caring for her son Steve after he was left a paraplegic as the result of an auto accident. He now lives independently. She became a vocal advocate for the rights and abilities of the handicapped. She was also careprovider for her husband after he contracted cancer.

Her good works have been recognized. Under her watch the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society won the Federation’s Achievement Award. She was nominated for the National Council of Jewish Women’s Humanitarian Award for “her great compassion for the needs of others.”

Nothing slows her down, either. A bad back that laid her up last year only kept her away from the store a few months, during which time she did all her business from home. The flow of merchandise never stopped. But she knows she can’t do it forever. That’s why she’d like to work out a plan for a successor — ideally someone like herself who, as Melingagio put it, “goes the extra mile.”

“I worry what’s going to happen to this place when I no longer can do it,” she said. “My hope is that there is somebody who has pretty much the idea that I have. That they’re caring and want so much for the kids that they know how to express that caring. Because that’s the bottomline. That’s what it’s all about.”

Related articles

- Steve Rosenblatt, A Legacy of Community Service, Political Ambition and Baseball Adoration (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Leo Greenbaum is Collector of Collectors of Jewish Artifacts at YIVO Institute (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Customer-First Philosophy Makes the Family-Owned Kohll’s Pharmacy and Homecare Stand Out from the Crowd (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Author Scott Muskin – What’s a nice Jewish boy like you doing writing about all this mishigas?

One of the best reads for me the last few years was Scott Muskin’s debut novel, The Annunciations of Hank Meyerson, Mama’s Boy and Scholar, and the story below is my attempt to make sense of the 2009 book and its author, whose work has gained him some measure of noteriety. Expectantly awaiting his next novel.

Author Scott Muskin – What’s a nice Jewish boy like you doing writing about all this mishigas?

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Jewish Press

Omaha native Scott Muskin’s well-received first novel, The Annunciations of Hank Meyerson, Mama’s Boy and Scholar, tells a funny, enlightened, inconvenient journey of self-discovery taken by the title’s protagonist-narrator. This satirical adventure leaves Hank scarred, liberated and, better-late-than-never, wised-up.

The novel was the inaugural (2007) winner of the Parthenon Prize for Fiction, a national competition to boost unknown authors.The Prize, which honored Annunciations out of more than 350 submissions, netted Muskin $8,000, plus a full, traditional book publishing contract. The final judge was author Tony Earley (Jim the Boy). Muskin will be in Omaha for a 1 p.m. Bookworm signing on April 18.

Annunciations was released this winter by Hooded Friar Press, a Nashville, Tenn.-based literary house that describes itself as “dedicated to publishing high-quality books by new authors.” Muskin’s clearly arrived as a new voice deserving attention.

He’s the son of Omahans Linda and Alan Muskin, members of Beth El Synagogue. His mother was a Millard Public Schools teacher. His father owned Youngtown, a chain of stores selling children’s furniture, toys, assundries. Alan’s father and Scott’s grandfather, Stuart Muskin, co-founded Youngtown, originally a Kiddie-Cut-Rate. The father character in Annunciations is a toy merchant from Omaha whose two boys, Hank and Carlton, were raised there. Most of the book’s set in Minneapolis, where Muskin and his wife Andrea Bidelman live in a 1920s stucco faux-Tudor home near Lake Nokomis. Muskin’s anchored the fiction in a reality he knows.

His story’s a modern, urban walkabout for a middle-class, secular American Jew who’s somehow managed to graduate college, start a career and marry without ever really finding himself or figuring out what he needs. Much less how to get it. His dysfunctional family is a case study. Smart, charming Hank’s schlepped through life, failing to hold himself accountable, letting old wounds fester, ignoring the very things that fill him with unresolved anger, unanswered questions, unfulfilled desires, unmitigated regret. An academic and free spirit by nature, he’s more attuned to Emily Dickinson arcania than to real life emotions and actions.

“Hank expected more of himself. He had larger dreams, of living a more passionate life,” Muskin said by way of analysis in a phone interview from his home in the Twin Cities. “When he starts to act on those, that’s when the trouble starts. Be careful what you wish for — that’s what’s driving the plot of the novel.”

Hank, a smart-alleck nebish who cops a superior attitude, is long overdue a comeuppance and he gets a doozy. Along the way, the putz learns to be a mensch.

Well-meaning in that lackadaisical way men are, Hank’s flippant defiance mucks up the works whether dealing with his estranged wife Carol Ann, distant father Daniel, troubled brother Carlton or the memory of his dead mother. Morally weak Hank acts out with his sister-in-law June and promptly runs away from his problems. Like an addict who believes the world revolves around him and conspires against him, Hank’s submerged in a bathos of ego, lust, self-pity, resentment and entitlement. A saving grace is his humor, which can cut through the clutter of his myopic vision.

It’s a witty and poignant exploration of the self-centered male psyche in identity crisis. Hank represents a type of male many women are familiar with — the kind who require a rude awakening to grow up. His stumbling, guilt-ridden initiation into adulthood rings true. Especially resonant is his strained relationship with his father and brother, who represent aspects of himself and his past he’d rather forget.

“I think one of the central dynamics of the book is that tension between silence and the unspoken energy in a family or in a relationship and the ways that that silence ends up finding voice,” said Muskin. “It’s not like it’s not there. It’s just being said in different ways. A lot of the interactions between the characters are animated by the ways it’s being unsaid. It does come out sometimes quite messily.”

Like most first novels Annunciations is personal. Muskin wrote it, in part, as a catharsis for the rough patch he went through around the time he started it.

“Well, I was getting divorced at the time or I was just divorced,” he said, thus the book is on one level “a working out of some of those things.”

The drama. Life happens.

“And I then found this voice to fictionalize it, which is a must. You’ve got to fictionalize it,” he said, otherwise it’s a self-indulgent rant. “I’m into real people and the real struggles they go through. Flaws and idiosyncratic obsessions — everyone’s got them. Shining a light on people who take a hard look at those things in themselves I find fascinating.”

Muskin found in Hank a literary avatar.

“I’m a quite biographical writer in terms of being able to find the emotional core of a situation if I’ve been through it or somehow been there. I then turn it or filter it through the prism of the character, and that’s important because then it forces you to think about the character’s perspective on things. You create three dimensionalites just by doing that — the interaction of the author, the character and the reader. It’s a way of getting closer to the universal.”

How close is Scott to Hank and vice versa?

“There’s a lot of similarities between me and Hank,” said his creator, “but there’s also a lot of differences, and the differences were more generative and healthier for the novel then were our similarities.”

For example, Muskin has a sister, not a brother, and the two of them get on fine. Finding the right voice for his protagonist let Muskin examine sibling rivalry.

“The book really took shape when I stumbled upon this voice,” he said. “I had been reading Richard Ford’s Independence Day and I remember thinking, ‘This is the kind of voice I want — a narrator who’s introspective but sardonic, thoughtful but sharp-witted, sharp-tongued. In essence, complex and likable and not likable.’ That’s the protagonist I wanted. I tried to steal that voice for a short story, not very successfully. Only when I put it into my own context did it begin to take shape.”

Short story writing was Muskin’s literary form of choice at the time. He’d had success placing pieces in literary journals and magazines. A collection by him was a finalist for the 2005 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction. While his stories earned him admiration and praise and some were published individually, he said “no one was terribly interested” in publishing them as a collection.

A mentor of his in graduate school at the University of Minnesota first suggested his talents might best lay in novel writing.

“One of my teachers, Julie Schumacher, pushed me. She said, ‘You ought to write a novel. You seem like a natural for it,’ and I took that to heart, and I finally hit upon a voice that I felt could sustain the novel for the reader.”

So, what did Schumacher see that made her nudge him along the novelist’s path?