Archive

Blacks of Distinction I

This set of profiles is from my large collection of African-American subjects. Read on and you will meet a gallery of compelling individuals who each made a difference in his or her own way. These figures represent a variety of endeavors and expertise, but what they all share in common is a passion for what they do. Along the way, they learned some hard lessons, and their individual and collective wisdom should give us all food for thought. The oldest of these subjects, Marcus Mac McGee, passed away shortly after these profiles appeared about 9 or 10 years ago. The story, which is really five stories in one, originally appeared in the New Horizons.

Blacks of Distinction

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Frank Peak, Still An Activist After All These Years

Addressing the needs of underserved people became a lifetime vocation for Frank Peak only after he joined the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s.

Today, as administrator of community outreach service for the Creighton University Medical Center Partnership in Health and co-administrator of the Omaha Urban Area Health Education Center, he carries on the mission of the Panthers to help empower African-Americans.

The Omaha native returned home after a six-year (1962-1968) hitch in the U.S. Navy as a photographer’s mate 2nd class, duty that saw him hop from ship to ship in the South China Sea and from one hot zone to another in Vietnam, variously photographing or processing images of military life and wartime action.

The North High grad came back with marketable skills but couldn’t get a job in the media here. He went into the service in the first place, he said, to escape the limited horizons that blacks like himself and his peers faced at home.

“There weren’t a lot of opportunities for blacks in the city of Omaha.”

In the Navy he found what he believed to be a future career path when he was sent to photography school in Pensacola, Florida and excelled. It was a good fit, he said, as he’d always been a shutterbug. “I had always liked photography and I always took pictures with little Brownies and stuff.”

His duty entailed working as a military photojournalist and photo lab technician. Many of the pictures he took or processed were reproduced in civilian and military publications worldwide. In 1965 he prepared the production stills for an NBC television news documentary on the 25th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. He said the network even offered him a job, but he had to turn it down, as he’d already reenlisted. Despite that lost opportunity, he counts his Navy experience as one of the best periods of his life. Not only did he learn to become an expert photographer but he got to travel all over the Far East, much of the time with his younger brother, William, who followed him into the service.

The service is also where Peak became politicized as a strong, proud black man engaged in the struggle for equality.

“Back in the ‘60s there was such a lot of turmoil related to the war, related to the whole race struggle. You know, Malcolm, Martin…It all tied together. There were a lot of riots going on at a lot of the bases and on the ships. There was both bonding and animosity then between whites and blacks. It was a challenging time. ”

A buddy he was stationed with overseas helped Peak gain a deeper understanding of the black experience.

“I had a close friend, Bennie, who was a Navy photographer, too. He was from Savannah, Georgia and he really began to educate me. He was the one that really initiated me into the black experience. That’s when the term black was radical. Coming from Omaha, I was isolated from a lot of things he’d been involved in down South. Interestingly, I ended up a member of the Black Panther party and he ended up a member of the Black Muslims.”

After Peak got out of the Navy and came back to find doors still closed to him, despite the obvious skills he’d gained, he was disillusioned.

For example, he said the Omaha World-Herald wouldn’t even look at his portfolio when he applied there. For years, he said the local daily had only one black photographer on staff and made it clear they weren’t interested in hiring another.

Frustrated with the obstacles he and his fellow African-Americans faced, he was ripe for recruitment into the Black Panthers, a controversial organization that several of his activist friends joined. But he didn’t join right away. He was working as a photo technician when something happened that changed his mind. A black girl named Vivian Strong died from shots fired by a white Omaha police officer. The tragedy, which many in the black community saw as a racially motivated killing, touched off several nights of rioting on the north side.

“I got involved with the Black Panther party after that,” Peak said.

The Panther platform was an expression of the black power movement that sought, Peak said, “self-determination and liberation” for African-Americans. “It was about building capacity into the black community. It was working to end police violence in the black community. It was organizing breakfast programs for our children. Tutoring kids. Holding rallies, organizing protests and standing up for our rights.”

What made the Panthers dangerous in the minds of many authorities were the party’s incendiary language, paramilitary appearance — some members openly brandished firearms — and militant attitude.

“Our premise was we wanted our rights by any means necessary,” said Peak, a philosophy he feels was misconstrued by law enforcement as a subversive plot to undermine and overthrow the government. “What we meant by that was we wanted our education, we wanted to be a part of the political process, we wanted to be a part of determining our own destiny. We even asked, as part of our platform, to have a plebiscite, where blacks would vote to directly determine, for themselves, their own fate.”

Instead, the leadership of the Panthers and other radical black power groups were “crushed” and “dismantled” in a systematic crackdown led by the FBI. In Omaha, Peak was among those arrested and questioned when two local Panthers, Ed Poindexter and David Rice, were implicated and later convicted in the 1970 killing of Omaha police officer Larry Minard. The pair’s guilt or innocence has long been disputed. Appeals for new trials or new evidentiary hearings continue to this today. Peak was friends with both men and he believes they’re wrongfully imprisoned. “I don’t believe they got a fair trial,” he said. Ironically, it was his cousin, Duane Peak, who allegedly acted at the men’s behest in making the 911 call that lured Minard to the house where a suitcase bomb detonated. Doubt’s been cast on whether Duane Peak made the call or not and on the veracity of his court testimony.

Frank Peak traces “the roots” of his advocacy career to his time with the Panthers, when he helped set up “a liberation” school and breakfast program for kids. He said the Panther mission has been “very much diversified” in the work being done today by former party members in the political, social, health, education and human service fields. “The struggle goes on.”

He and other young blacks here were inspired to affect change from within by mentors. “Theodore Johnson put together community health programs. Dr. Earl Persons got us involved in the black political caucus. Jessie Allen got us involved as delegates to the Democratic party. He really brought us around and politicized us to mainstream politics. Dan Goodwin and Ernie Chambers had a great influence on us, too. They made sure we were accountable. They had high standards for us.” There was also Omaha Star publisher Mildred Brown, reporter/activist Charlie Washington and others. Peak’s education continued at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he earned a bachelor’s in journalism and psychology and a master’s in public administration. Lively discussions about black aspirations unfolded at UNO, the Urban League, Panther headquarters, Charlie Hall’s Fair Deal Cafe and Dan Goodwin’s Spencer Street Barbershop.

Frank Peak

The spirit of those ideals lives on in his post-Panthers work, ranging from substance abuse counseling to community health advocacy to he and his wife, Lyris Crowdy Peak, an Omaha Head Start administrator, serving as adoptive and foster parents. He sees today’s drug and gang culture as a major threat. He rues that standards once seen as sacrosanct have “gone out the window” in this age of relativism.

“The only way change is going to occur is if people make it happen,” he said. “If you wait around for somebody else to make it happen, it might not…So, we all have a responsibility to make a contribution and I’m trying to make one.”

He enjoys being a liaison between Creighton and the community in support of health initiatives, screenings and services aimed at minorities. “We just finished glaucoma screenings in south Omaha and we put together the first African-American prostate cancer campaign in north Omaha. We sponsor programs like My Sister’s Keeper, a breast cancer survivors program focused on African-American women.” He said in addition to assessment and treatment, Creighton also provides follow-up services and referrals for those lacking the access, the means, the insurance or the primary care provider to have their health care needs met.

“I’m somebody who believes in what he does. People ask me, Do you like your job? I say, Well, if you get paid for doing something you’d do for free, how could you not like it? That’s my philosophy. To think maybe in some small way you’ve been a part of growing a greater society, then that’s all the reward I need.”

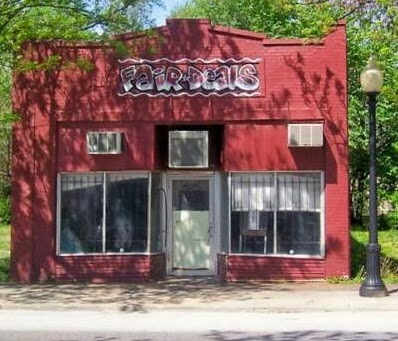

Charles Hall’s Fair Deal

As landmarks go, the Fair Deal Cafe doesn’t look like much. The drab exterior is distressed by age and weather. Inside, it is a plain throwback to classic diners with its formica-topped tables, tile floor, glass-encased dessert counter and tin-stamped ceiling. Like the decor, the prices seem left over from another era, with most meals costing well under $6. What it lacks in ambience, it makes up for in the quality of its food, which has been praised in newspapers from Denver to Chicago.

Owner and chef Charles Hall has made The Fair Deal the main course in Omaha for authentic soul food since the early 1950s, dishing-up delicious down home fare with a liberal dose of Southern seasoning and Midwest hospitality. Known near and far, the Fair Deal has seen some high old times in its day.

Located at 2118 No. 24th Street, the cafe is where Hall met his second wife, Audentria (Dennie), his partner at home and in business for 40 years. She died in 1997. The couple shared kitchen duties (“She bringing up breakfast and me bringing up dinner,” is how Hall puts it.) until she fell ill in 1996. These days, without his beloved wife around “looking over my shoulder and telling me what to do,” the place seems awfully empty to Hall. “It’s nothing like it used to be,” he said. In its prime, it was open dawn to midnight six days a week, and celebrities (from Bill Cosby to Ella Fitzgerald to Jesse Jackson) often passed through. When still open Sundays, it was THE meeting place for the after-church crowd. Today, it is only open for lunch and breakfast.

The place, virtually unchanged since it opened sometime in the 1940s (nobody is exactly sure when), is one of those hole-in-the-wall joints steeped in history and character. During the Civil Rights struggle it was commonly referred to as “the black city hall” for the melting pot of activists, politicos and dignitaries gathered there to hash-out issues over steaming plates of food. While not quite the bustling crossroads or nerve center it once was, a faithful crowd of blue and white collar diners still enjoy good eats and robust conversation there.

|

Fair Deal Cafe

Running the place is more of “a chore” now for Hall, whose step-grandson Troy helps out. After years of talking about selling the place, Hall is finally preparing to turn it over to new blood, although he expects to stay on awhile to break-in the new, as of now unannounced, owners. “I’m so happy,” he said. “I’ve been trying so hard and so long to sell it. I’m going to help the new owners ease into it as much as I can and teach them what I have been doing, because I want them to make it.” What will Hall do with all his new spare time? “I don’t know, but I look forward to sitting on my butt for a few months.” After years of rising at 4:30 a.m. to get a head-start on preparing grits, rice and potatoes for the cafe’s popular breakfast offerings, he can finally sleep past dawn.

The 80-year-old Hall is justifiably proud of the legacy he will leave behind. The secret to his and the cafe’s success, he said, is really no secret at all — just “hard work.” No short-cuts are taken in preparing its genuine comfort food, whose made-from-scratch favorites include greens, beans, black-eyed peas, corn bread, chops, chitlins, sirloin tips, ham-hocks, pig’s feet, ox tails and candied sweet potatoes.

In the cafe’s halcyon days, Charles and Dennie did it all together, with nary a cross word uttered between them. What was their magic? “I can’t put my finger on it except to say it was very evident we were in love,” he said. “We worked together over 40 years and we never argued. We were partners and friends and mates and lovers.” There was a time when the cafe was one of countless black-owned businesses in the district. “North 24th Street had every type of business anybody would need. Every block was jammed,” Hall recalls. After the civil unrest of the late ‘60s, many entrepreneurs pulled up stakes. But the Halls remained. “I had a going business, and just to close the doors and watch it crumble to dust didn’t seem like a reasonable idea. My wife and I managed to eke out a living. We never did get rich, but we stayed and fought the battle.” They also gave back to the community, hiring many young people as wait staff and lending money for their college studies.

Besides his service in the U.S. Army during World War II, when he was an officer in the Medical Administrative Corps assigned to China, India, Burma, Japan and the Philippines, Hall has remained a home body. Born in Horatio, Arkansas in 1920, he moved with his family to Omaha at age 4 and grew up just blocks from the cafe. “Almost all my life I have lived within a four or mile radius of this area. I didn’t plan it that way. But, in retrospect, it just felt right. It’s home,” he said. After working as a butcher, he got a job at the cafe, little knowing the owners would move away six months later to leave him with the place to run. He fell in love with both Dennie and the joint, and the rest is history. “I guess it was meant to be.”

Deadeye Marcus Mac McGee

When Marcus “Mac” McGee of Omaha thinks about what it means to have lived 100 years, he ponders a good long while. After all, considering a lifespan covering the entire 20th century means contemplating a whole lot of history, and that takes some doing. It is an especially daunting task for McGee, who, in his prime, buried three wives, raised five daughters, prospered as the owner of his own barbershop, served as the state’s first black barbershop inspector, earned people’s trust as a pillar of the north Omaha community and commanded respect as an expert marksman. Yes, it has been quite a journey so far for this descendant of African-American slaves and white slave owners.

A recent visitor to McGee’s room at the Maple Crest Care Center in Benson remarked how 100 years is a long time. “It sure is,” McGee said in his sweet-as-molasses voice, his small bright face beaming at the thought of all the high times he has seen. In a life full of rich happenings, McGee’s memories return again and again to the first and last of his loves — shooting and barbering. For decades, he avidly hunted small game and shot trap. In his late 80s he could still hit 100 out of 100 targets on the range. Yes, there was a time when McGee could shoot with anyone. He won more than his share of prizes at area trapshooting meets — from hams and turkeys to trophies to cold hard cash. As his reputation began to spread, he found fewer and fewer challengers willing to take him on. “I would break that target so easy. I’d tear it up every time. I’d whip them fellas down to the bricks. They wouldn’t tackle me. Oh, man, I was tough,” he said.

As owner and operator of the now defunct Tuxedo Barbershop on North 24th Street, he ran an Old School establishment where no fancy hair styles were welcome. Just a neat, clean cut from sparkling clippers and a smooth, close shave from well-honed straight-edge razors. “The best times for me was when I got that shop there. I got the business going really good. It was quite a shop. We had three chairs in there. New linoleum on the floor. There were two other barbers with me. We had a lot of customers. Sometimes we’d have 10-15 people outside the door waiting for us to come in. I enjoyed that. I enjoyed working on them — and I worked on them too. I’d give them good haircuts. I was quite a barber. Yes, sir, we used to lay some hair on the floor.”

McGee’s Tuxedo Barbershop was located in the Jewell Building

A fussy sort who has always taken great pains with his appearance, he made his own hunting vests, fashioned his own shells and watched what he ate. “I was particular about a lot of things,” he said. Unlike many Maple-Crest residents, who are disabled and disheveled, McGee walks on his own two feet and remains well-groomed and nattily-attired at all times. He entrusts his own smartly-trimmed hair to a barbering protege. Last September, McGee cut a dashing figure for a 100th birthday party held in his honor at Clair Memorial United Methodist Church. A crowd of family and friends, including dozens of grandchildren and great-grandchildren, gathered to pay tribute to this man of small stature but big deeds. Too bad he could not share it all with his wife of 53 years, LaVerne, who died in 1996.

Born and raised along the Mississippi-Louisiana border, McGee’s family of ten escaped the worst of Jim Crow intolerance as landowners under the auspices of his white grandmother Kizzie McGee, the daughter of the former plantation’s owner. McGee’s people hacked out a largely self-sufficient life down on the delta. It was there he learned to shoot and to cut hair. He left school early to help provide for the family’s needs, variously bagging wild game for the dinner table and cutting people’s hair for spare change. Just out of his teens, he followed the path of many Southern blacks and ventured north, where conditions were more hospitable and jobs more plentiful. During his wanderings he picked up money cutting heads of railroad gang crewmen and field laborers he encountered out on the open road.

He made his way to Omaha in the early 1920s, finding work in an Omaha packing plant before opening his Tuxedo shop in the historic Jewel Building. People often came to him for advice and loans. He ran the shop some 50 years before closing it in the late 1970s. He wasn’t done cutting heads though. He barbered another decade at the shop of a man he once employed before injuries suffered in an auto accident finally forced him to put down his clippers at age 88. “I loved to work. I don’t know why people retire.” As much as he regrets not working anymore, he pines even more for the chance to shoot again. “I miss everything about shooting.” He said he even dreams about being back on the hunt or on the range. Naturally, he never misses. “I always take the target. Yeah, man, I was one tough shooter.”

Proud, Poised Mary Dean Pearson

A life of distinction does not happen overnight. In the case of Omaha executive, educator, child advocate, community leader, wife and mother Mary Dean Pearson, the road to success began just outside Marion, La., where she grew up as one of nine brothers and sisters in a fiercely independent black family during the post World War II era — a period when the South was still segregated. From as far back as she can remember, Pearson (then Hunt) knew exactly what was expected of her and her siblings– great things. “I grew up in the South during the Crow era and my father instilled in all of his children a very profound sense of obligation to improve on what we were born into. To make it better. Whether that was our immediate economic circumstances or social status or whatever,” she said.

Despite the fact her parents, Ed and Rosa Hunt, never got very far in school they were high achievers. He was a respected landowner and entrepreneur and, together with Rosa, set rigorously high standards for their children. Even the daughters were expected to do chores, to complete high school and, unusual for the time, to attend college. “My father was a very driven, very aggressive man who believed it was our right and our duty to do well everyday. And to do only well. The consequences were quite severe if you didn’t do well. He also instilled a work ethic, which is probably unparalleled, in all of us,” said Pearson, a former Omaha Public Schools teacher and past director of the Nebraska Department of Social Services who, since 1995, has been president and CEO of the Boys and Girls Clubs of Omaha, Inc.

“I was his workhorse from time to time. I call him the father of women’s lib because he never hesitated to say, ‘Baby, do this,’ even if it was a heavy job traditionally reserved for men. I really credit him with helping me understand that anything that needed to be done, I perhaps had the capability of doing it, and so I just approached everything with that can-do sensibility. I got that from him, no doubt.”

Where her father cracked the whip, her mother applied the salve. “My mother was a gentle soul who was the one always to seek peace and to seek a solution. I think my attempt to become a peacemaker and facilitator was my desire to be more like her. She created an absolutely wonderful balance for our family. They were a dynamite team.” For Pearson, the lessons her parents taught her are bedrock values that never go out of style: “Honesty, integrity, loyalty, perseverance.”

Pearson and her siblings did not let their parents down, either. They became professionals and small business owners. She graduated with a liberal arts degree from Grambling State University, hoping for a career in law. Her plans were put on hold, however, after marrying her old beau Tom Harvey, who got a teaching contract in Omaha, where the young couple moved in the late 1960s. She tried finding work here to earn enough money for law school but found doors closed to her because of her color. Then, she joined the National Teacher Corps, a federal teaching training program pairing liberal arts majors with students in inner city schools. She soon found she could make a difference in young lives and abandoned law for education. “I discovered there were some young folks in this world who were absolutely starving for intellectual challenge, and I enjoyed providing that to them.”

As part of the program she earned a master’s degree in education at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where former College of Education dean Paul Kennedy became the strong new mentor figure in her life. “If I ever thought I was going to slack off once I had left my father, I was wrong. Paul Kennedy saw my soul and demanded the very best from me.” After earning her teaching degree at UNO, she embarked on a 20-year education career that included serving as an OPS classroom teacher, assistant principal and principal. She treasures her experiences as an educator and holds the role of educator in the highest esteem.

“As a classroom teacher you can actually see you have touched someone. The satisfaction is immediate. As an administrator, the obligation is to give every child, every learner, the maximum opportunity for success. It is to say, ‘All children can learn.’” She is “proudest” of how successful some of her former students are. “They are carrying on the lessons they were taught to make our society a better one as teachers, lawyers, doctors, ministers.”

By 1986 Pearson was ready for some new challenges. Starting with her term as executive director of Girls Incorporated through her stewardship of the state’s social services agency (at then Gov. Ben Nelson’s request) and up to her current post as head of the Boys and Girls Clubs, she has focused on programs for disadvantaged youths that “improve their life chances.” While Pearson can one day see herself exploring new challenges outside the social service arena, she would miss impacting children. “Of all the groups present in our society, children are the one one group who need an advocate more than any other.”

Mildred Lee , Standing Her Ground

When brazen drug dealers threatened over-running her north Omaha neighborhood in the early 1990s, Mildred Lee reacted like most residents — at first. With an open-air drug market operating 24-hours a day within yards of her well-maintained property, she saw children wading through discarded drug paraphernalia and strewn garbage. She saw neighbors growing fearful. She saw things heading toward a violent end. That’s when she made it her crusade to pick-up debris and to let the pushers and addicts know by her defiant demeanor she wanted them out. She hoped they would all just go away. They didn’t.

As the criminal activity increased, Lee considered moving, but the idea of being run out of her own house infuriated her. A dedicated walker, she refused letting some punks stop her hikes. “I thought, ‘If I live in the neighborhood, I’m going to walk in the neighborhood.’ They attempted to intimidate me, but I wasn’t afraid of them. I just didn’t back off.” As months passed and she realized others on her block were too afraid to do anything, this widow, mother and grandmother decided to act. “I was disgusted. I could see that nobody else was going to do it, so I thought, ‘I’ll just do it myself.’”

Fed up, she called a friend, Rev. J.D. Williams, who had worked with local law enforcement to rid his own district of bad apples. He set-up a meeting with Omaha Police Department officials, who informed Lee they were aware of the problem but were waiting for residents to come forward to ask what could be done to reclaim the area.

What happened next was a transforming experience for Lee, who went from bystander to activist in a matter of weeks. It just so happened her coming forward coincided with the city’s first Weed and Seed program, a federally-funded initiative to weed out undesirables and to seed areas with positive activities. Several things happened next. First, the Fairfax Neighborhood Association was formed and Lee was elected its president. The association acted as a watchdog and liaison with law enforcement.

Then the Mayor’s Office proposed a Take Our Neighborhood Back rally to showcase residents’ solidarity against crime. The Mad Dads lent their support to the event, which saw a parade of citizens chanting and holding anti-drug slogans outside known drug dens and a convoy of trucks displaying caskets as a dramatic reminder that drugs kill. Police on horseback added symbolic fanfare. A brigade of citizens armed with rakes, shovels and brooms swept up litter in the area and others hauled away old appliances and assorted other junk from residents’ homes and deposited the items in dumpsters. As a reminder to criminals that police were ever-vigilant, a mobile command unit was stationed on-site around the clock. No parking and no loitering signs were posted on streets. Finally, sting operations conducted by police and FBI resulted in dozens of arrests.

Under Lee’s leadership, the Fairfax Association launched a latchkey program for school-age children at New Life Presbyterian Church, painted houses for elderly residents, converted a vacant lot into a mini-park and hosted Neighborhood Night Out block parties among other good works. Recognized as the driving force behind it all, Lee was asked to serve on the city’s Weed and Seed steering committee and her ideas were sought by public and private leaders. Not bad for someone who had never been a community activist before. She never had time. She was always too busy working (as an employment interviewer with the Nebraska Job Service) and, after her husband died from a massive heart attack at age 36, raising their four children alone.

As Lee became a focal point for taking back her neighborhood, she began fielding inquiries from residents of other areas facing similar problems. She shared her experiences in talks before vcommunity groups and received a slew of honors for her community betterment efforts, including the 1999 Spirit of Women award. With her work here now finished, Lee is preparing to move down South to start a new life with her new husband. The legacy she leaves behind is a community now brimming with active neighborhood associations, many modeled after Fairfax.

“One of the reasons we’ve gotten attention is we’re the neighborhood that stood up first,” she said. The whole experience, she said, has been empowering for her. “It brought to light a lot of things I didn’t know I could do. I never thought of being a leader before. But when you’re put in a certain position, you do what you have to do.” The message she imparts with audiences today is that we can all make a difference, if we care enough to try. “Most people are afraid. They don’t want anything to do with it. But they don’t realize you’ve already got something to do with it if drug dealers are in your neighborhood. You’ve just got to take charge. You can’t just sit back and wait for somebody else to do it.” She said doing good works gets to be contagious. “When other people see all you’re doing, then they want to start doing more too.”

Related Articles

- Stephan Salisbury: Stage-Managing the War on Terror: Ensnaring Terrorists Demands Creativity (huffingtonpost.com)

- Challenging Judge Walker (theroot.com)

- The White City (2009) (newgeography.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Big Bad Buddy Miles (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Arno Lucas, Serious Sidekick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Enchantress “LadyMac” Gets Down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Myers Legacy of Caring and Community

Myers Funeral Home is an institution in northeast Omaha‘s African-American community, and like with any long-standing family business there is a story behind the facade, in this case a legacy of caring and community. My article originally appeared in the New Horizons.

The Myers Legacy of Caring and Community

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Strictly speaking, a funeral home is in the business of death. But in the larger scheme of things, a mortuary is where people gather to celebrate life. It’s where tributes are paid, memories are recalled, mourning is done. It’s a place for taking stock. One where offering condolences shares equal billing with commemorating high times. In a combination of sacred and secular under one roof, everything from prayers are said to stories told to secrets shared. It encapsulates the end of some things and the continuation of others. It’s where we face both our own mortality and the imperative that life goes on. Perhaps more than anywhere outside a place of worship, the mortuary engages our deepest sense of family and community.

Besides organizing the myriad of details that services encompass, funeral directors act as surrogate family members for grieving loved ones, providing advice on legal, financial and assundry other matters. It means being a good neighbor and citizen. It’s all part of being a trusted and committed member of the community.

“It’s more than just being a funeral director. It’s like I used to tell people, ‘Look, you called me to perform a service, and I’m here to do it. Think of me really as a part of the family. We’re all working together because we have a job to do. My role is to see it goes the way it’s supposed to go,” said Robert L. Myers, former owner and retired director of Myers Funeral Home in Omaha. The dapper 86-year-old with the Cab Calloway looks and savoir-faire ways lives with his wife of 54 years, Bertha, a retired music educator, guidance counselor, choir director and concert pianist, at Immanuel Village in northwest Omaha. After the death of his first wife, with whom he had two daughters, he married Bertha, who raised the girls as her own. They became educators like her.

For Myers, community service extended to social causes. Much of his volunteering focused on improving the plight of he and his fellow African-Americans at a time when de facto segregation treated them as second-class citizens.

He learned the importance of civic-minded conviction from his father, W.L. Myers, the revered founder of Myers Funeral Home — 2416 North 22nd Street — Nebraska’s oldest continuously run African-American owned and operated business. Since the funeral parlor’s 1921 Omaha opening, three generations of Myers have overseen it. W.L. ran things from 1921 until 1947, when his eldest son, Robert, went into partnership with him. Then, in 1950, W.L. retired and Robert took over. He was soon joined by his brother, Kenneth, with whom he formed a partnership before they incorporated. In the early ‘70s, Kenneth handed over the enterprise to his son and Robert’s nephew, Larry Myers, Jr, who still owns and operates it today.

The Myers name has been a fixture on the northeast Omaha landscape for 84 years. From its start until now, it’s presided over everyone from the who’s-who of the local African-American scene to the working class to the indigent.

W.L. saw to it no one was turned away for lack of funds. He assisted people in their time of need with more than a well-turned out funeral, too.

“Families come in helpless. They’ve had a death. It’s a traumatic event. They don’t know what to do. They’re upset. They need some guidance. Dad was more interested in counseling and guiding people than he was in the financial part of it,” Myers said. “He’d tell them which way to go. What extra step they should take. How to handle their business affairs. How to dispose of their property. They’d plead, ‘What am I going to do, Mr. Myers?’ He’d say, ‘Don’t worry about it. You just ask me anything you want.’ I’d say the same thing. That’s where I learned a lot from him. Be fair and be truthful. He was that, so people would call him because they knew he would lead them in the right way. Money was secondary.”

Myers said his father’s goodwill helped build a reputation for fairness that served him and the funeral home well.

“A lot of times, people couldn’t pay him, especially back in the Depression days. He did a lot of charity service. He would talk to Mom about it. ‘They don’t have any money,’ he’d say. ‘Well, go ahead and give ‘em a service,’ she’d tell him. He’d try and reassure her with, ‘It’ll come back some way or another down the line.’ And as a result, he got a lot of repeat business. The next time those people came back, why they were able to pay him. They’d say, ‘I remember you helped me out. I’ll never forget that and I want to employ you again, and this time I’ll take care of it myself.’ Word of mouth about his generosity built his business.”

The Golden Rule became the family credo. “Compassion. That’s what we learned from Dad. He wouldn’t let anybody take advantage of our people. He looked out for our people and saw that they were treated fairly,” he said.

“Back in those days, a lot of our people couldn’t read and write and were afraid of dealing with white collar types, who were usually Caucasian and liked to assert their authority over minorities. Dad used to take folks to the insurance office or the social security office or the pension office, so he could talk eyeball to eyeball with these bureaucrats. That way, our people wouldn’t be intimidated. If the suits got confrontational, he would take over and intercede. He’d say, ‘Wait a minute. Back off.’ He’d speak for the people. ‘Now then, she has what coming to her?’ He’d do the paperwork for them. We’d carry people through the process.”

Myers said his father rarely if ever made a promise he couldn’t keep.

“The word is the bond. That was my dad,” Myers said. “And that’s what I developed, too, in dealing with people. If I say something, you can go to the bank with it.” That reputation for integrity carries a solemn responsibility. “People reveal confidences to you that you would not divulge for love of money. Everything is confidential. You appreciate that type of trust.”

His father no sooner got the funeral home rolling than the Great Depression hit. W.L. plowed profits right back into his business, including relocating to its present site and making expansions. He never skimped on services to clients.

In an era before specialization, Myers said, a funeral director was a jack-of-all-trades. “We did everything from car mechanics to medicine to law to vocal singing to counseling to barber-beautician work to yard work.” Keeping a fleet of cars running meant doing repairs themselves. W.L. graced services with his fine singing voice, an inherited talent Robert shared with mourners. Robert’s mother, Essie, played organ. His wife, Bertha did, too. Describing his father as “a self-made and self-educated man,” Myers said W.L. enjoyed the challenge of doing for himself, no matter how far afield the endeavor was from his formal mortuary training.

“He was very hungry for knowledge. He read incessantly. Anything pertaining to this line of work, to business, to the law…He sent off for correspondence courses. He just wanted to know as much as he could about everything. He knew a lot more than some of these so-called educated people. He could stand toe-to-toe and converse. Doctors and lawyers respected his intellect.”

The patriarch’s “classic American success story” began in New London, Mo., a rural enclave near Hannibal. He sprang from white, black and Native American ancestry. His folks were poor, hard-working, God-fearing farmers. His mother also ran a cafe catering to farmers. Born in 1883, W.L. enjoyed the country life immortalized by Mark Twain. Myers said his father felt compelled from an early age to intern the remains of wildlife he came upon during his Huck Finn-like youth. “He just felt every living thing should have a decent burial. That was his compassion. He just loved to funeralize — to speak words and what-not in a service. I think he had the calling before he realized what he was doing. That just led him into the real thing.”

But W.L.’s journey to full-fledged mortician took many hard turns before coming to fruition. As a young man he found part-time work burying Indians for the State of Oklahoma. Later, he worked in a coal mine in Buxton, Iowa, a largely-black company town that died when the coal ran out. He eventually scraped together enough money to enter the Worsham School of Embalming in St. Louis. When his money was exhausted, he took a garment factory job in Minneapolis, where he was gainfully employed the next eight years. He made foreman. In 1908 he married Essie, mother of Robert, Kenneth and their now deceased older sisters, Florence and Hazel.

The good times ended when W.L.’s black heritage was discovered and he was summarily fired — accused of “passing.” With a family to support, he next made the brave move of picking up and moving to Chicago. There, he worked odd jobs while studying at Barnes School of Anatomy in pursuit of his mortuary dream.

Upon graduating from Barnes in 1910 he was hired as an embalmer at a Muskogee, Ok. funeral home. After a long tenure there he was again betrayed when the owner, whom he taught the embalming art, fired him, saying he no longer needed his services. It was a slap in the face to a loyal employee.

Tired of the abuse, W.L. opened the original Myers Funeral Home in 1918 in Hannibal, where Robert was born. When slow to recover from a bout of typhoid fever he’d contracted down south, doctors ordered W.L. to more northern climes. So, in 1921 he packed his family in a touring car en route to Minneapolis when a fateful stopover in Omaha to visit friends changed the course of their lives.

It just so happened a former Omaha funeral home at 2518 Lake Street was up for grabs in an estate sale. W.L. liked the set-up and the fact Omaha was a thriving town. North 24th Street teemed with commerce then. The packing houses and railroads employed many blacks. Despite little cash, he rashly proposed putting down what little scratch he had between his own meager finances and what friends contributed and to pay the balance out of the proceeds of his planned business. The deal was struck and that’s how W.L. and Myers Funeral Home came to be Omaha institutions. As his son Robert said, “He wasn’t heading here. He was stopped here.” Character and compassion did the rest.

Myers admires his parents’ fortitude. “Dad was a school-of-hard-knocks guy. He was determined to do what he wanted and to make it on his own, and he succeeded in spite of many obstacles. I always appreciated how our mother and father sacrificed to give us advantages they did not have. They put all four of us through college.”

Old W.L.’s instincts about relocating here proved right. Under his aegis, Myers Funeral Home soon established itself as the premiere black mortuary in Omaha.

“He had a little competition when he came in, but it all faded away,” Myers said. “Some of the black funeral homes were fronts for whites. They didn’t have the training, the skills, the know-how, nor the techniques Dad developed over the years. Plus, he was very personable. People took to him. The clientele came to him, and he ran with it.”

“Everybody was pretty much in the same boat. But we had community. We had fellowship. We had a bond through the church and what-not. So, everybody kind of looked out for everybody else,” Myers said.

As youths, Robert and Kenneth had little to do with the family business, but since the Myers lived above the mortuary, they were surrounded by its activities and the stream of people who filed through to select caskets, seek counsel, view departed. Their mother answered the phone and ushered in visitors. The boys were curious what went on in the embalming room but were forbidden inside. They knew their father expected them to follow him in the field.

“It was kind of understood. When I was in school, I looked into other areas like pharmacy and law and this, that and the other thing, but it didn’t go anywhere,” Myers said. “I guess Dad’s blood got into me because there was really nothing else I wanted to do. Besides, I liked what he was doing and the way he was doing it. I always felt the same way he did with people.”

A Lake Elementary School and Technical High School grad, Myers earned his bachelor’s degree from prestigious, historically black Howard University in Washington, D.C., where Kenneth followed him. After graduating from San Francisco College of Mortuary Science, he worked in an Oakland funeral home three years. He intended staying on the west coast, but events soon changed his mind. Frustrated by an employer who resisted the modern methods Robert tried introducing, he then got word that W.L. had lost his chief assistant and could use a hand back home. The clincher was America’s entrance in World War II. Robert got a deferment from the military in light of the essential services he performed.

From 1943 until the mid-’60s, Myers had a ringside seat for some fat times in Omaha’s black community. Those and earlier halcyon days are long gone. Recalling all that the area once was and is no more is depressing.

“It is because I can think back to the Dreamland Ballroom and all the big bands that used to come there when we were kids. We used to stand outside on summer nights. They’d have a big crowd out there. The windows would be open and we could hear all this good music and, ohhhh, we’d just sit back and enjoy every minute of it. Yeah, I think back on all those things. How at night we used to stroll up and down 24th Street. Everybody knew everybody pretty much. We’d stand, greet and talk. You didn’t have to worry about anything. Yeah, I miss all that part.”

The northside featured any good or service one might seek. Social clubs abounded.

“We had a lot of black professional people there — doctors, lawyers, dentists, pharmacists. They intermingled with the white merchants, too,” he said. Then it all changed. “Between the riots’ destruction and the North Freeway’s division of a once unified community, it started going down hill. And, in later years, after the civil rights movement brought in open housing laws and our people had a chance to better themselves, many began moving out of the area’s substandard housing.”

He said northeast Omaha might have staved-off wide-spread decline had blacks been able to get home loans from banks to upgrade existing properties, but restrictive red lining practices prevented that. Through it all — the riots, white flight, the black brain drain, gang violence — Myers

Funeral Home remained.

“No, we never considered moving away from there. Even though North 24th Street was pretty well shot, the churches were still central to the life of the community. People still came back into the area to attend church,” he said.

Emboldened by the civil rights movement, Robert and Bertha put themselves and their careers on the line to improve conditions. As a lifetime member of the NAACP and Urban League, he supported equal rights efforts. As a founder of the 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties) he organized and joined picket lines in the struggle to overturn racial discrimination. As a member of Mayor A.V. Sorensen’s Biracial Commitee and Human Relations Board and a director of the National Association of Christians and Jews, he promoted racial harmony. As the first black on the Omaha Board of Education (1964-1969), he fought behind the scenes to create greater opportunities for black educators.

With blacks still denied jobs by some employers, refused access to select public places and prevented from living in certain areas, Myers was among a group of black businessmen and ministers to form the 4CL and wage protest actions. The short-lived group initiated dialogues and broke down barriers, including integrating the Peony Park swimming pool. In his 4CL role, he went on the record exposing Omaha’s shameful legacy of restrictive housing covenants.

In a 1963 Omaha Star article, Myers is quoted as saying, “The wall of housing segregation” here is “just as formidable as the Berlin Wall in Germany or the Iron Curtain in Russia.” Labeling Omaha as the “Mississippi of the North,” he said the attitudes of realtors is “one of down right ghetto planning.” He and Bertha raised the issues of unfair housing practices in a personal way when they went public with their ‘60s ordeal searching for a ranch-style home in all-white districts. Realtors steered them away, some discreetly, others bluntly. The Myers finally resorted to using a front — a sympathetic white couple — for building a new residence in the Cottonwood Heights subdivision. When the Myers were revealed as the actual owners, a fight ensued. Subjected to threats and insults, they endured it all and stayed.

“That’s what my dad gave me an education for — to not accept these things. To see it for what it’s worth and to do something about it,” said Myers, who replied to a developer’s offer to move elsewhere with — “You don’t assign us a place to live.”

In a letter to the developer, Myers wrote, “Let me remind you that this is America in 1965 and…you must accept the fact there are some things money, threats or circumstances cannot change. We knew we could expect some trouble, we just figured it was part of the price we have to pay for living in a new area.”

Myers also worked for change from the inside as a member of the Omaha school board. The board had a lamentable policy that largely limited the hiring of black teachers to substitute status or, if hired full-time, placed them only in all-black schools and blocked promotion to administrative ranks. Even black educators with advanced degrees were routinely shut out.

“That was my wife’s situation. After she finished Northwestern University School of Music she couldn’t get a job here. She had to go to Detroit,” he said. Bit by bit, he got OPS to relax its policies. “The majority of school board members were in the frame of mind that they saw the unfairness of it. I was the catalyst, so to speak. All my work was done in the background in what’s called the smoke-filled back room.”

Advocating for change in a period of raging discontent brought Myers unwanted attention. He got “flak” from blacks and whites — including some who thought he was pushing too hard-too fast and others who alleged he was moving too soft-too slow. “I became something of a hot potato,” he said. “I thought I was independent and could do what I wanted because I didn’t have to rely on whites for business, but I found out people in my own community could get to me.”

The experience led Robert to retreat from public life. At least he had the satisfaction of knowing he’d carried on where his father left off. An anecdote Myers shared reveals how much his father’s approval meant to him.

“I handled a service one time when Dad was out sick. This was before my brother had joined us, so everything fell on me. I was scared,” he said. “There’s a lot to deal with. The mourners. The minister. The choir. The pallbearers. The employees. And you’re in charge of the whole thing. The whole operation has got to jell with just the right timing — from when to cue the mourners to exit to what speed the cars are to be driven. It’s all done silently — with expressions and gestures.

“Well, we went through the whole service OK. Later, a friend of the family told me. ‘Your old man told me to keep an eye on you and to watch everything you do and report back to him.’ He said he told my dad “everything was perfect — that I handled things just the way he would have’ and that my dad said, ‘That’s all I wanted to know.’ So, in that respect, Dad was still watching over me. It made me feel good to know I’d pleased him.”

Related Articles

- Woman Claims ‘Death at a Funeral’ Ripped Off Her Real-Life Funeral Nonsense (cinematical.com)

- A Dying Industry to Die For (fool.com)

- Home funerals making a comeback (nj.com)

Flanagan-Monsky example of social justice and interfaith harmony still shows the way seven decades later

When I became aware of the fact that Father Edward Flanagan, the Catholic priest and Boys Town founder whom Spencer Tracy won an Oscar portraying in the classic MGM movie, was close friends with prominent American Jewish leader Henry Monsky, I was intrigued. Then when I discovered that Monsky was a key figure in the formation, survival, and growth of Boys Town, I knew there was a story to be told. I like how men of two different faiths found enough common ground to work together for the greater good. My story originally appeared in the Jewish Press.

It’s interesting to me that this interfaith bond should happen in Omaha, a decidedly Catholic and Protestant communnity. At the time when Flanagan and Monsky forged their solidarity, the local Jewish population was much larger than it is today. But as my story points out, the relationship between Boys Town and the Omaha Jewish community remains strong all these decades later. And Omaha is receiving national attention these days for its ambitious Project Interfaith, a union of the local Episcopal, Jewish, and Muslim faith communities that is trying to lay the groundwork for a planned tri-faith campus. One can only think that Flanagan and Monsky would be pleased.

You can find more stories by me about Boys Town on this blog, including one that charts the story of the 1938 MGM movie Boys Town (“When Boys Town Bwecame the Center of the Film World”), another that explores its athletic glory years (“Rich Boys Town Sports Legacy Recalled”), and still another that looks at the investigative newspaper reporting that uncovered Boys Town’s hidden wealth (“Sun Reflection, Revisiting the Omaha Sun‘s Pulitzer Prize-Winning Expose of Boys Town”).

Fr. Edward Flanagan

Flanagan-Monsky example of social justice and interfaith harmony still shows the way seven decades later

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the Jewish Press

Even as the world grows ever flatter and more interconnected, political, religious, ethnic differences still separate people into divisive factions. One need only consult history or today’s news to see how this distrust of the other is the cause of conflict. Inroads to understanding can be made. The efforts of the NAACP, the Urban League, the National Conference for Community and Justice and many other organizations bring disparate groups together in a spirit of cooperation.

Macro alliances can start at the micro level. All it takes is two persons willing to work toward the greater good. Ninety years ago in Omaha two men — a Catholic priest and a Jew — forged an enduring friendship that made famous a haven for homeless boys, shined a light on at-risk youth and demonstrated the power of unified action. Father Edward Flanagan was an Irish immigrant prelate dedicated to rescuing men from the bowery and children from delinquency. He dreamed of a home for wayward boys but lacked funds. Henry Monsky, a Jew from the Orthodox tradition, was a social activist and attorney with a law degree from Jesuit Creighton University, where he graduated top in his class (1912).

As legend has it, Monsky is the mensch who loaned Flanagan $90 to start Boys Town in 1917. For the next 30 years he served, without pay, as Flanagan’s confidante and legal counsel. Monsky also drew his law office of Monsky, Grodinsky, Marer & Cohen into tending to the home’s affairs. One partner, William Grodinsky, joined Monsky in serving on the BT board of trustees.

Like his fellow mensch, the priest, Monsky was involved in assisting children in the juvenile justice system, a cause he “felt deep in his bones, as Flanagan obviously did, too,” said Omaha historian Oliver Pollak. Recognizing they shared a vision for helping lost boys, they formed an association “of legendary proportions,” Pollak writes in his article, “The Education of Henry Monsky,” published in the journal Western States Jewish History. That association is much documented, even dramatized in the 1938 movie “Boys Town.” A Jewish merchant-benefactor in the film, Dave Morris, is based on Monsky, whose desire for anonymity led him to secure a promise from producers that neither his real name nor profession be used. Columnist Walter Winchel later revealed Monsky as the real Dave.

In 1989 the Boys Town Hall of History and the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society co-curated an exhibition, “Father Flanagan and Henry Monsky: Men of Vision,” telling these men’s story. The exhibit, which showed at Boys Town and the Jewish Community Center, traveled widely. Boys Town plans to display the exhibit again next fall for the home’s 90th anniversary celebration. 2008 is the 60th anniversary of Flanagan’s death. 2007 marked the 60th anniversary of Monsky’s passing.

“The close friendship between Father Flanagan and Mr. Monsky was very unique for its time,” said Boys Town Hall of History director Tom Lynch. “…Father Flanagan had developed an ecumenical outlook on life, especially when it came to helping children in need…Father forged many bonds with like-minded individuals of different races and religions. The first such friendship was with Henry Monsky, who represents the thousands of supporters who have assisted Boys Town…”

The bond of brotherhood these men exemplified lives on today.

“There is a respectful mutuality in the relationship between the Jewish community and Boys Town,” said Father Steve Boes, national executive director of Boys Town. At the 2005 ceremony introducing Boes as BT’s new leader “Rabbi Jonathon Gross of the Beth Israel Synagogue offered a prayer for our kids, our organization and for me. Since that day and in the spirit of Henry Monsky and Father Flanagan, we have developed a friendship meet monthly.

“Our discussions range from the social problems that affect our community to personal issues like family, exercise and prayer. I have come to value our time together and see it as a great extension of Father Flanagan’s legacy. We also have a relationship with Beth Israel Synagogue. Members have helped serve Christmas dinner to our kids who can’t return home at the holidays.”

Just as Boes and Gross make an intriguing contrast today, so did Flanagan and Monsky. Flanagan, the pale, soft-spoken, bespectaled Irish priest. Monsky, the dark-complexioned, loud, lion-headed, larger-than-life Jew.

Just as having a top flight attorney and lay Jewish leader in his corner was a coup for Flanagan and BT, having a preeminent child welfare advocate and Catholic priest on his side was a boon for Monsky and convergent Jewish interests. Each was a Great Man in his own right. Flanagan owned the ear of powerful figures on the national-international stages, traveling the globe on speaking, goodwill and fact-finding tours. He commanded large audiences through personal appearances he made, including many addresses before Jewish crowds, and interviews he gave. He openly supported interfaith alliances and Zionist causes. At the time of his death he was acting at the behest of President Harry S. Truman in appraising the war orphan situation in Europe, a mission he made the year before to Korea and Japan.

Monsky served on many civic and charitable boards and from 1938 to 1947 presided as international president of B’nai B’rith, the largest Jewish service club, at a crucible time in history. As an ardent Zionist he implored U.S. and world leaders to intervene on behalf of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe and supported the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. He helped form the American Jewish Conference (Congress), served as editor of the National Jewish Monthly and consulted the U.S. delegation at the formation of the United Nations.

He and Omahan Sam Beber also established the AZA, the world’s largest Jewish youth organization.

Like Flanagan, Monsky was in high demand as a public speaker, addressing audiences of all persuasions, and enjoyed entree into halls of power. He, too, encouraged interfaith collaboration and served on many Catholic boards.

Henry Monsky, Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archive

No one knows precisely when or how they met but there’s no question they saw each other as kindred souls working to save endangered or abandoned youth. The fact one was Jewish and the other Catholic seemed to matter little to them.

Monsky’s widow, Daisy (Hirsch) Monsky, makes these points in the book she co-authored with Maurice Bisgyer, “Henry Monsky: The Man and His Work”:

“The profound friendship and loyal devotion between Henry and Father Flanagan was based on the fact that, despite the vast difference in their formal religion, both believed in social justice and both were willing to work to achieve it. There are innumerable stories of the bond between them…Father Flanagan always knew that Henry could be depended upon to act for the benefit of the underprivileged.”

In her book Daisy recounts the time Flanagan borrowed $25,000 from a board member in order to post bail for a boy charged with murder in Iowa. The priest learned of extenuating circumstances in the case and decided the lad would be better served at BT rather than in a youth detention center while awaiting trial. In a letter Flanagan asked Monsky to smooth over the legalities of it all:

“…Henry, this home is for saving boys, and we cannot let that boy stay in jail over there…I hope you will present the matter properly at the next meeting of the board, and explain what has been done.”

Always the trusted servant, Monsky persuaded the board to approve the loan and its repayment. Up until his trial the boy remained at Boys Town.

The story illustrates how the men shared an implicit understanding of how BT matters should be handled. The symbiotic way they operated is not surprising when you consider the two knew each from the time they were young men.

Ireland born and reared, Flanagan first came to America in 1904. That year or the next he arrived in Omaha on the coattails of older brother Patrick, a priest who started Holy Angels Church on the north side. It’s then that Edward may have first met Henry, who lived nearby. When Edward expressed interest in the priesthood, the Omaha bishop — a fellow Irishman named Harty — accepted him as a seminarian and sent him off to study in Rome. Ordained in 1912, Flanagan was assigned to Omaha, where he celebrated his first mass at Holy Angels. Monsky was studying law at nearby Creighton. After a stint in O’Neill, Neb. Flanagan returned to Omaha in 1913 at St. Patrick Catholic Church. He and Monsky soon worked together — to establish a Boy Scouts of America council and to advocate for youth with juvenile justice system judges and social workers.

A 1945 address by Flanagan at a B’nai B’rith tribute for Monsky at the Commodore Hotel in New York City alludes to their longtime friendship:

“…we have come here to honor a great man — a man with a brilliant mind and a loving heart. A man whose outstanding virtue is his love for his fellow man…Unlike most of you here, I have known him as a boy, a student at the university, a young lawyer entering upon a professional career — a fellow worker with whom it was my privilege to engage in charitable and welfare fields. He is a member of the board of Father Flanagan’s Boys Home, and my own attorney. He is my personal friend.”

The fondness they felt for each other is seen in their correspondence:

Flanagan to Monsky on the receipt of a gift:

“My dear Henry, I have received your wonderful gift…It is very kind of you, dear Henry, to think of me in this way — I don’t know what other gift would be appreciated as much right now. Wishing you God’s every blessing and success, I remain, dear Henry, Yours most sincerely…”

And on the occasion of Monsky’s marriage to Daisy:

“…I am very happy to hear this good news, for I know it makes you happy, and my whole household joins with me in wishing you both every blessing and happiness that this old world can bring to people of good will…”

Monsky, in appreciation of that note, references an honor conferred on Flanagan:

“…I know how interested you are in my welfare, and I assume that happiness that comes to me gives you the same thrill as I experienced when I witnessed your elevation (to monsignor) in last Sunday’s ceremony. I think I know as much as anyone does how well merited this recognition is. With kindest regards…”

And on the occasion of his election to international B’nai B’rith president:

“I appreciate very much your telegram…It is delightful to know, in undertaking a responsibility of this character, that one has the confidence of those with whom he has been intimately associated for so many years…”

Monsky’s admiration for Flanagan is evident in a speech he gave at a 1942 dinner celebrating BT’s 25th anniversary.

“This is a privilege that I would not like to have missed…Father Flanagan, you can be very proud for what you have contributed in the past 25 years…those of us who have been on the board have enjoyed the great privilege, not only in that we have worked with you, but accepted your philosophy of this unique institution that ‘there is no such thing as a bad boy”…It is perfectly understandable that he has become the outstanding individual in America for his work with boys.”

In 1921 Monsky chaired the speakers bureau for BT’s inaugural capital campaign, which bought the land and erected the first building for the campus.

In a letter to Daisy, Flanagan wrote about his departed friend’s service on behalf of that campaign, which raised some $25,000:

“He spent much of his time then in training our boys who constituted his principal speakers on the public platforms throughout Omaha and its environs for this campaign. He took even more interest in making this campaign a success than he did his own business, but it seems to me he did this with everything he took up…That is why he was a great man, a great friend and a great citizen.”

The home and Flanagan became national icons thanks to savvy marketing and the success of MGM’s 1938 hit Boys Town. Superstar Spencer Tracy won the Best Actor Oscar for his endearing portrayal of Flanagan and popular Mickey Rooney won new legions of fans as the plucky Whitey.

Even before the movie Flanagan and the home gained national exposure via a weekly coast-to-coast radio broadcast he delivered. But the movie brought a whole new level of attention. From its two-week, on-location shoot in Omaha to its September 7, 1938 premiere at the Omaha Theatre downtown, Boys Town was a phenomenon. Thousands of curious onlookers descended on the campus for a glimpse of the stars during the filming, which unfolded in the middle of a July heat wave. There’s some suggestion the Monskys put up Rooney at their home and that Rooney and Henry’s son, Hubert, went out on the town more than once.

At the movie’s world premiere, an estimated 30,000 people filled the streets, sidewalks and roofs around the Omaha Theater. Daisy recalled the excitement of that opening night in her book:

“…the stage setting was irresistible…Klieg lights, loud speakers, all the Hollywood paraphernalia stretched for blocks…as we left the car..the master of ceremonies stopped my husband for a broadcast over the loud speaker…of his speech…In the theater we sat just in front of Father Flanagan, Bishop Ryan, Mickey Rooney and his date and other visiting celebrities. Mickey…wept at all of the touching scenes, including his own. So did Henry, whose emotions were always easily stirred.”

Besides being invited to make remarks for the pre-show program outdoors, Monsky was among the guests introduced inside the theater.

Despite the hoopla, BT officials and MGM big wigs had little confidence in the pic. Flanagan-Monsky gave away the rights to the story for a measly $5,000. The story goes they didn’t think the movie stood a prayer of making money. And they probably weren’t wise to the going rates in Hollywood. Studio files indicate MGM boss Louis B. Mayer lacked enthusiasm for the property even after it’s completion, shelving it for months before Tracy-Rooney prevailed upon him to release it. The rest is history. When the movie hit big a new problem arose — donations dried up as the public assumed BT made a killing on it, not realizing the home saw nothing from the box office receipts. A desperate Flanagan, perhaps at the urging or with the blessing of Monsky, asked MGM to get the word out that BT needed help. Tracy signed his name to an appeal letter sent donors. The money flooded in. MGM, perhaps feeling guilty, gave $250,000 for the construction of a dormitory.

The sequel to Boys Town, 1941’s Men of Boys Town, was not well received but it still carried the home’s message and name. Where Flanagan-Monsky erred in securing a small rights fee the first time, they negotiated $100,000 for the sequel, which proved a shrewd move when the movie bombed.

Boys Town further capitalized on the films when a nationally broadcast radio serial aired weekly dramatizations based on the lives of residents there.

From the 1938 movie, Boys Town

Up to the time of his death in 1947 Monsky remained a close ally of Flanagan’s and key adviser to Boys Town. He was there for it all: from a fledgling start in an old 10-room house downtown; to the purchase of the Overlook farm for the present site; to an impressive campus build-out that turned corn fields into a “city of little men” with fine educational, vocational, residential and recreational facilities; to the household name status Boys Town gained and parlayed.

The measure of high esteem in which Flanagan held Monsky and his contributions to BT is expressed in this letter to Daisy:

“…Henry was Boys Town…He is as much responsible for the fine things the public sees out there as are my associates and me, for it was through his keen mind and advice that we were able to follow a pattern of prudence and good judgment. Never in all my association with men have I found one who seemed to understand what I wanted to do and who would advise me how best to do it. Over the years we have had many difficult problems…and Henry’s handling of all these matters was one of great satisfaction. I have received from him over the years hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of advice for which I paid nothing. It is only within the last few years that I was able to show my appreciation in a small way, and never have I considered anything that I did for Henry a recompense for his legal work…”

The late Hubert Monsky confirmed the selfless nature of his father in an interview for the “Men of Vision” exhibit:

“…when my father passed away, in going through his desk…found a check written to my father for $25,000 by Father Flanagan…and a note attached to it which said, ‘Henry, dear, for years your services have been given to us with no renumeration, and now that we have the funds, you must accept this.’ That check was seven months old — my father would not cash it. That was very typical of the two people. Father Ed recognized what my father had done. He appreciated it deeply and in his fashion he was trying to say…’God bless you, Henry, for a job well done.’ But my father didn’t wish to be compensated for any work that he did for Boys Town because he felt that it was a project for everybody in Omaha.”

Referring to Monsky’s work as a board of trustee member, Flanagan wrote:

“He was one of the most active members of the Board in determining policies, and was constantly concerned with anything which would further the interests of Boys Town. His fine legal mind would shine forth at these Board meetings…and I know that in following his advice we have made very few mistakes.”

Flanagan trusted Monsky’s judgment enough that he involved him in nearly all aspects of the home’s operations and interests. Further testimony of this high regard is found in the following except from a letter the priest wrote to Daisy:

“He was one of the most active members of the Board in the founding of the Boys Town Foundation Fund and in this, as in all other legal matters, resolutions, etc., he personally dictated those and gave much thought and consideration to them.

“Henry’s last and final act was giving advice and counsel in the establishment of the training program in Boys Counseling to be established at the Catholic University of America in cooperation with…Boys Town, which offers a two-year graduate training program leading to a degree, M.A., in Boys Counseling.”

Although neither made a fuss over it, Monsky’s and Flanagan’s nonsectarian brotherhood transcended their vastly different backgrounds. From the start Flanagan opened BT to boys of all races and creeds. While Jewish youths have always accounted for a tiny percentage of residents, one, Daniel Ocanto, was elected mayor of the incorporated village in 2002-2003.

Whatever faith a youth professes, BT facilitates their practice of it. “If you’re a Lutheran, I’m gonna make you a better Lutheran than you are now. If you’re a Jew, I’m gonna make you a better Jew than you are now,”said former Boys Town director Father Val Peter. Current director Father Steve Boes said, “When we admit Jewish students to campus, we work with local synagogues to secure their religious training, and our kids are always welcomed with open arms.”

Monsky’s association with Flanagan modeled his belief in interfaith outreach. That’s why this prominent Jew served on the Catholic Commission on American Citizenship and the National Catholic Welfare Conference and on the boards of other non-Jewish organizations, including the Community Chest, the Boy Scouts, the Nebraska Conference of Social Work, the Church Peace Union and the Urban League.

Even though BT’s not Catholic per se, the fact a Catholic priest has always headed it lends it that church’s imprimatur. That was even more true during Flanagan’s regime. As far as the general public and media were concerned, the priest and BT were synonymous, making it a de facto Catholic ministry. That’s why the identification of a noted Jew like Monsky with BT was a model for how Jewish-Catholic relations could proceed both on a personal level and in regard to issues.

“They were men of different faiths,” writes Omaha historian Oliver Pollak. “Both had faith, particularly faith in the next generation….No doubt exists that Monsky and Flanagan were men of great faith whose concern for troubled youth transcended parochial boundaries.”

Every time Monsky’s involvement with BT made headlines, as it did when at Flanagan’s invitation he gave the commencement speech for the 1942 graduating class, it illustrated the possibility of Jewish-Catholic unity. Monsky’s address to the 90 8th grade and high school grads emphasized sacrifice at a time of war:

“You are, indeed, fortunate to have been taught here at Father Flanagan’s Boys Home…that life has significance, that life is purposeful…Thus conditioned, it is expected that you have the necessary equipment to assume and discharge adequately your share of the greater responsibility which each of us must bear in the present crisis…Not unlike other chapters in our nation’s history, the record of these difficult days will be resplendent with the glorious achievements of youth.”

Ties between the home and the Jewish community were strengthened by the Flanagan-Monsky bond. When elected to the BT board of trustees in ‘29 Monsky replaced another Jewish leader, the late Rabbi Frederick Cohn, of Temple Israel.

Just as Monsky’s link with BT generated Jewish outreach with the Catholic community, Flanagan’s link with Monsky led to a close relationship between B’nai B’rith and BT. Flanagan addressed several B’nai B’rith gatherings, including those in Omaha, Philadelphia and Los Angeles. He spoke before the Jewish Ladies Auxiliary of the B’nai B’rith lodge in Detroit. He was the keynote speaker for the Jewish Children’s Home of Rhode Island, the Young Men’s Jewish Council for Boys’ Clubs in Chicago and the National Conference of Christians and Jews in Minneapolis.

Evidence suggests Flanagan and Monsky recommended each other for interfaith engagements and appointments, and took satisfaction in doing so. A 1939 letter from Monsky to Flanagan refers to an invitation for the priest to speak before “a very substantial group of Jewish people in Chicago, which I am sure will give you a very acceptable audience…If acceptance of this invitation is possible, of course, I would appreciate it.” The Monsky letter also mentions “reports” about Flanagan’s appearance before another Jewish group “have pleased me very much. I am happy to note the great demand on the part of my co-religionists, and particularly B’nai B’rith lodges, for the message of Father Flanagan’s Boys Home.”

In another letter to his friend Monsky describes the positive feedback a Flanagan appearance before a B’nai B’rith group in Phillie elicited, adding that members expressed “pleasure in the fact that we appeared to be very good friends.”

The BT-BB relationship is one that continues 60 years after the two friends’ deaths.

“The B’nai B’rith historically brings its sports banquet speakers to Boys Town to meet our children” and to do media interviews, said John Melingagio, Boys Town director of public relations. “Their members also have individually or collectively done charitable activities ranging from donations of funds, services or needed items to mentoring or creating opportunities for our children in the community,”

“I just can’t shake the feeling when we do that, that the two friends are looking down and smiling at the successful legacy of their dreams,” said Gary Javitch, president of the Omaha B’nai B’rith Henry Monsky Lodge #3306.

Melingagio added its only natural for BT and the Jewish Community Center, where the local B’nai B’rith is headquartered, should be on good terms as the organizations are neighbors. Each extends open invitations to the other for various programs and activities. Boys Town and the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society at the JCC work cooperatively to update the Flanagan-Monsky exhibit.

Temple Israel senior Rabbi Aryeh Azriel said Jewish-Catholic relations ebb and flow but the “special relationshp” Flanagan and Monsky exhibited serves as an example of how people of two faith groups can interact in constructive ways. He would like to see more such comradeship and collegiality today in serious interfaith dialogues.

Examples of interfaith work abound locally.

Monsky’s alma mater, Creighton University, has a tradition of being welcoming to Jews and promoting Jewish studies. Monsky was invited to make the 1925 commencement address at Creighton. Jews Rodney Shkolnik and Larry Raful were longtime deans of the Creighton Law School. CU’s legal aid center is named after Milton Abrahams. The university is home to the Klutznick Chair in Jewish Civilization, a post held by Leonard Greenspoon. CU’s Kripke Center, named for Rabbi Myer Kripke and his wife Dorothy, promotes understanding between the Jewish, Christian and Islamic faith communities. Despite its strong WASP roots the University of Nebraska at Omaha hosts: the Rabbi Sidney H. Brooks Lecture Series in honor of the late Omaha religious leader who worked for social justice and unity; and the Leonard and Shirley Goldstein Human Rights Lecture Series in honor of the Omaha Jewish couple long active in the Free Soviet Jewry movement.

Additionally, Rabbi Azriel of Temple Israel has served on the United Catholic Social Services board and chairs the clergy committee for Omaha Together One Community (OTOC), a faith-based social action group. He’s won recognition for his human relations work, including a Black/Jewish Dialogue initiative he led.

These efforts to be inclusive rather than exclusive and to foster fellowship rather than division coincide with the work of Project Interfaith. The Omaha Anti-Defamation League program directed by Beth Katz brings Christians, Jews and Muslims together to share the gifts of their respective faiths. Katz has traveled to the Vatican and to Israel with interfaith groups.