Archive

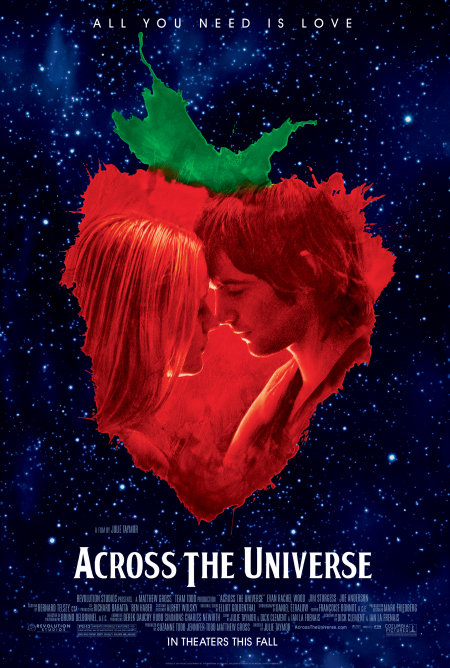

Hot Movie Takes – “Rawhide”

Hot Movie Takes – “Rawhide”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

I love a good Western. This quintessential American film form is full of possibilities from a storytelling perspective because of the vast physical and metaphorical landscapes it embodies. The American West was a wide open place in every sense. Everything there was up for grabs. Thus, the Old West frontier became a canvass for great conflicts and struggles involving land, resources, power, control, law, values, ideas, dreams and visions. With so much at stake from a personal, communal and national vantage point, dramatists have a field day using the Western template to explore all manner of psycho-social themes. Add undercurrents of personal ambition, rivalry, deceit and romantic intrigue to the mix not to mention race and ethnicty, and, well, you have the makings for a rich tableaux that, in the right hands, is every bit as full as, say, Shakespeare or Dickens.

All of which is to say that last night I viewed on YouTube a much underrated Western from the Golden Age of Hollywood called “Rawhide” (1951) that represents just how satisfying and complex the form can be, This is an extremely well-crafted work directed by Henry Hathaway, written by Dudley Nichols and photographed by Milton Krasner. Tyrone Powers and Susan Hayward head a very strong cast rounded out by Hugh Marlowe, Jack Elam. Dean Jagger, George Tobias, Edgar Buchanan and Jeff Corey.

“Rawhide” isn’t quite a Western masterpiece but it’s very good and elements of it are among the very best seen in the Western genre. Let’s start with the fact that the script is superb. It’s an intelligent, taut thriller with a wicked sense of humor leavening the near melodramatic bits. Nichols wrote some of John Ford’s best films and so in a pure story sense “Rawhide” plays a lot like a Ford yarn with its sharply observed characters and situations that teeter back and forth between high drama and sardonic relief.

Like most great Westerns, this is a tale about the tension between upstanding community, in this case a very small stagecoach outpost stop, and marauding outlaws. Across the entire genre the classic Western story is one variation or another of some community, usually a town or a wagon train, under siege by some threat or of some individual seeking revenge for wrongs done him/her or of a gunman having to live up to or play down his reputation.

In “Rawhide” escaped outlaws are on the loose and the stagecoach station manager (Buchanan) and his apprentice (Power), along with a woman passenger (Hayward) and her child, are left to fend for themselves by U.S. cavalry troops hot on the bad guys’ trail. When the four desperate men show up they make the station inhabitants their captives. The leader (Marlowe) is an educated man who exhibits restraint but he has trouble keeping in line one of the men (Elam) who escaped prison with him. Sure enough, things get out of hand as tensions among the outlaws and with the surviving hired hand and woman mount. The criminals are intent on stealing a large gold shipment coming through and the captives know their lives will be expendable once the robbery is over, and so they scheme for a way to escape. The trouble is they are locked in a room most of the time and when let outside they’re closely guarded. Their best chance for getting out of the mess seems to be when a nighttime stage arrives but it and its passengers come and go without the man or woman being able to convey the dire situation. But one more opportunity presents itself when the daytime coach with the gold shipment approaches and the pair, aided by the outlaws’ own internal conflicts. use all their courage and ingenuity to face down the final threat.

The dramatic set-up is fairly routine but what Nichols, Hathaway and Krasner do with it is pretty extraordinary in terms of juxtaposing the freedom of the wide open spaces and the confinement of the captives. A great deal of claustrophobic tension and menace is created through the writing, the direction and the black and white photography, with particularly great use of closeups and in-depth focus. Hathaway’s and Krasner’s framing of the images for heightened dramatic impact is brilliantly done.

The acting is very good. Power, who himself was underrated, brings his trademark cocksure grace and sense of irony to his part. Hayward, who is not one of my favorite actresses from that period, parlays her natural toughness and fierceness to give a very effective performance that is almost completely absent of any sentimentality. Marlowe is appropriately smart and enigmatic in his role and he displays a machismo I didn’t before identify with him. Buchanan, Jagger, Tobias and Corey are all at their very best in key supporting roles that showcase their ability to indelibly capture characters in limited screen time. But it’s Elam who nearly steals the picture with his manic portrayal that edges toward over-the-top but stays within the realm of believability.

“Rawhide” doesn’t deal in the mythic West or confront big ideas, which is fine because it knows exactly what it is, It’s a lean, realistic, fast-paced Western with just a touch of poetry to it, and that’s more than enough in my book.

Hathaway made more famous Westerns, such as “The Sons of Katie Elder” and “True Grit,” but this is a better film than those. With his later pics Hathaway seemed to be trying to follow in the footsteps of John Ford with the scope of his Westerns, but he was no John Ford. Hathaway was best served by the spare semi-documentary style he employed earlier in his career in film noirs like “Kiss of Death,” “13 Rue Madeleine” and “Call Northside 777” and Westerns like “Rawhide.” One exception was “Nevada Smith,” which does successfully combine the leanness of his early career with the sprawling approach he favored late in his career.

Rawhide 1951 Full Movie – YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z03hbI7IZ8g

Hot Movie Takes: PAYNE’S “DOWNSIZING’” – It may be next big thing on the world cinema landscape

Hot Movie Takes:

PAYNE’S “DOWNSIZING’” – It may be next big thing on the world cinema landscape

BY LEO ADAM BIGA, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

April 2017 issue of The Reader

Hot Movie Takes – Gregory Peck

Hot Movie Takes – Gregory Peck

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Gregory Peck was a man and an actor for all seasons. Among his peers, he was cut from the same high-minded cloth as Spencer Tracy and Henry Fonda, only he registered more darkly than the former and more warmly than the latter.

In many ways he was like the male equivalent of the beautiful female stars whose acting chops were obscured by their stunning physical characteristics. Not only was Peck tall, dark and handsome, he possessed a deeply resonant voice that set him apart, sometimes distractingly so, until he learned to master it the way a great singer does. But I really do believe his great matinee idol looks and that unnaturally grave voice got in the way of some viewers, especially critics, appreciating just what a finely tuned actor he really was. Like the best, he could say more with a look or gesture or body movement than most actors can do with a page of dialogue. And when he did speak lines he made them count, imbuing the words with great dramatic conviction, even showing a deftness for irony and comedy, though always playing it straight, of course.

I thought one of the few missteps in his distinguished career was playing the Nazi Doctor of Death in “The Boys from Brazil.” The grand guignol pitch of the movie is a bit much for me at times and I consider his and Laurence Oliver’s performances as more spectacle than thoughtful interpretation. I do admire though that Peck really went for broke with his characterization, even though he was better doing understated roles (“Moby Dick” being the exception). I’m afraid the material was beyond director Franklin Schaffner, a very good filmmaker who didn’t serve the darkly sardonic tone as well as someone like Stanley Kubrick or John Huston would have.

Peck learned his craft on the stage and became an immediate star after his first couple films. He could be a bit stiff at times, especially in his early screen work, but he was remarkably real and human across the best of his performances from the 1940s through the 1990s. I have always been perplexed by complaints that he was miscast as Ahab in “Moby Dick,” what I consider to be a film masterpiece. For my tastes at least his work in it does not detract but rather adds to the richness of that full-bodied interpretation of the Melville classic.

My two favorite Peck performances are in “Roman Holiday” and, yes, “To Kill a Mockingbird.” I greatly admire his work, too, in “The Stalking Moon” and have come to regard his portrayal in “The Big Country” as the linchpin for that very fine film that I value more now than I did before. He also gave strong performances in “The Yearling,” “Yellow Sky,” “The Gunfighter,” “12 O’Clock High,” “The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit,” “Pork Chop Hill,” “On the Beach,” “Cape Fear,” “The Guns of Navarone,” “How the West was Won,” “Captain Newman M.D.” “Mirage” and “Arabesque.” I also loved his work in two made for television movies: “The Scarlet and the Black” and “The Portrait.”

He came to Hollywood in the last ebb of the old contract studio system and within a decade joined such contemporaries as Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster in producing some of his own work.

Peck’s peak as a star was from the mid-1940s through the late 1960s, which was about the norm for A-list actors of his generation. Certainly, he packed a lot in to those halcyon years, working alongside great actors and directors and interpreting the work of great writers. He starred in a dozen or more classic films and in the case of “To Kill a Mockingbird” one of the most respected and beloved films of all time. It will endure for as long as there is cinema. As pitch perfect as that film is in every way, I personally think “Roman Holiday” is a better film, it just doesn’t cover the same potent ground – i.e. race – as the other does, although its human values are every bit as moving and profound.

Because of Peck’s looks, stature and voice, he often played bigger-than-life characters. Because of his innate goodness he often gravitated to roles and/or infused his parts with qualities of basic human dignity that were true to his own nature. He was very good in those parts in which he played virtuous men because he had real recesses of virtue to draw on. His Atticus Finch is a case of the right actor in the right role at the right time. Finch is an extraordinary ordinary man. I like Peck best, however, in “Roman Holiday,” where he really is just an ordinary guy. He’s a journeyman reporter who can’t even get to work on time and is in hock to his boss. Down on his luck and in need of a break, a golden opportunity arises for a world-wide exclusive in the form of a runaway princess he’s happened upon. Lying through his teeth, he sets out to do a less than honorable thing for the sake of the story and the big money it will bring. It’s pure exploitation on his part but by the end he’s fallen for the girl and her plight and he can’t go through with his plan to expose her unauthorized spree in Rome. I wish he had done more parts like this.

Here is a link to an excellent and intimate documentary about Peck:

- [VIDEO]

A Conversation with Gregory Peck 6/11 – YouTube

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPjDwN9KY0g

Just last night on YouTube I finally saw an old Western of his, “The Bravados,” I’d been meaning to watch for years. It’s directed by Henry King, with whom he worked a lot (“The Gunfighter,” Twelve O’Clock High,” “Beloved Indidel”), and while it’s neither a great film nor a great Western it is a very good if exasperatingly uneven film. That criticism even extends to Peck’s work in it. He’s a taciturn man hell-bent on revenge but I think he overplays the grimness. I don’t know if some of the casting miscues were because King chose unwisely or if he got stuck with certain actors he didn’t want, but the two main women’s parts are weakly written and performed. Visually, it’s one of the most distinctive looking Westerns ever made. Peck also had fruitful collaborations with William Wyler (“Roman Holiday” and “The Big Country”), Robert Mulligan (“To Kill a Mockingbird” and “The Stalking Moon”) and J.L Thompson (“Cape Fear” and “The Guns of Navarone).

Two Peck pictures I’ve never seen beyond a few minutes of but that I’m eager to watch in their entirety are “Behold a Pale Horse” and “I Walk the Line.”

Peck’s work will endure because he strove to tell the truth in whatever guise he played. His investment in and expression of real, present, in-the-moment emotions and thoughts give life to his characterizations and the stories surrounding them so that they remain forever vital and impactful.

For a pretty comprehensive list of his screen credits, visit:

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000060

Hot Movie Takes Saturday – FIVE CAME BACK

Hot Movie Takes Saturday – FIVE CAME BACK

©by Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Five Legendary Filmmakers went to war:

John Ford

William Wyler

Frank Capra

George Stevens

John Huston

Five Contemporary Filmmakers take their measure:

Paul Greengrass

Steven Spielberg

Guillermo del Toro

Lawrence Kasdan

Francis Ford Coppola

When the United States entered World War II these five great Hollywood filmmakers were asked by the government to apply their cinema tools to aid the war effort. They put their lucrative careers on hold to make very different documentaries covering various aspects and theaters of the war. They were all masters of the moving picture medium before their experiences in uniform capturing the war for home-front audiences, but arguably they all came out of this service even better, and certainly more mature, filmmakers than before. Their understanding of the world and of human nature grew as they encountered the best and worst angels of mankind on display.

The story of their individual odysseys making these U.S, government films is told in a new documentary series, “Five Came Back,” now showing on Netflix. The series is adapted from a book by the same title authored by Mark Harris. The documentary is structured so that five contemporary filmmakers tell the stories of the legendary filmmakers’ war work. The five contemporary filmmakers are all great admirers of their subjects. Paul Greengrass kneels at the altar of John Ford; Steven Spielberg expresses his awe of William Wyler; Guillermo del Toro rhapsodizes on Frank Capra; Lawrence Kasdan gushes about George Stevens; and Francis Ford Coppola shares his man crush on John Huston. More than admiration though, the filmmaker narrators educate us so that we can have more context for these late filmmakers and appreciate more fully where they came from, what informed their work and why they were such important artists and storytellers.

The Mission Begins

As World War II begins, five of Hollywood’s top directors leave success and homes behind to join the armed forces and make films for the war effort.

Combat Zones

Now in active service, each director learns his cinematic vision isn’t always attainable within government bureaucracy and the variables of war.

The Price of Victory

At the war’s end, the five come back to Hollywood to re-establish their careers, but what they’ve seen will haunt and change them forever.

Ford was a patriot first and foremost and his “The Battle of Midway” doc fit right into his work portraying the American experience. For Wyler, a European Jew, the Nazi menace was all too personal for his family and he was eager to do his part with propaganda. For Capra, an Italian emigre, the Axis threat was another example of powerful forces repressing the liberty of people. The “Why He Fight” series he produced and directed gave him a forum to sound the alarm. A searcher yearning to break free from the constraints of light entertainment, Stevens used the searing things he documented during the war, including the liberation of death camps, as his evolution into becoming a dramatist. Huston made perhaps the most artful of the documentaries. His “Let There Be Light” captured in stark terms the debilitating effects of PTSD or what was called shell shock then. His “Report from the Aleutians” portrays the harsh conditions and isolation of the troops stationed in Arctic. And his “The Battle of San Pietro” is a visceral, cinema verite masterpiece of ground war.

The most cantankerous of the bunch, John Ford, was a conservative who held dear his dark Irish moods and anti-authoritarian sentiments. Yet, he also loved anything to do with the military and rather fancied being an officer. He could be a real SOB on his sets and famously picked on certain cast and crew members to receive the brunt of his withering sarcasm and pure cussedness. His greatest star John Wayne was not immune from this mean-spiritedness and even got the brunt of it, in part because Wayne didn’t serve during the war when Ford and many of his screen peers did.

Decades before he was enlisted to make films during the Second World War, he made a film, “Four Sons,” about the First World War, in which he did not serve.

Following his WWII stint, Ford made several great films, one of which, “They Were Expendable,” stands as one of the best war films ever made. His deepest, richest Westerns also followed in this post-war era, including “Rio Grande,” “Fort Apache,” “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon,” “The Searchers,” “The Horse Soldiers” and “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.” Another war film he made in this period, “The Wings of Eagles,” is another powerful work singular for its focus on a real-life character (played by Wayne) who endures great sacrifices and disappointments to serve his country in war.

Even before the war Ford injected dark stirrings of world events in “The Long Voyage Home.”

William Wyler had already established himself as a great interpreter of literature and stage works prior to the war. His subjects were steeped in high drama. Before the U.S. went to war but was already aiding our ally Great Britain, he made an important film about the conflict, “Mrs. Miniver,” that brought the high stakes involved down to a very intimate level. The drama portrays the war’s effects on one British family in quite personal terms. After WWII, Wyler took this same closely observed human approach to his masterpiece, “The Best Years of Our Lives,” which makes its focus the hard adjustment that returning servicemen faced in resuming civilian life after having seen combat. This same humanism informs Wyler’s subsequent films, including “The Heiress,” “Roman Holiday,” “Carrie,” “The Big Country” and “Ben-Hur.”

Wyler, famous for his many takes and inability to articulate what he wanted (he knew it when he saw it), was revered for extracting great performances. He didn’t much work with Method actors and I think some of his later films would have benefited from the likes of Brando and Dean and all the rest. One of the few times he did work with a Method player resulted in a great supporting performance in a great film – Montgomery Clift in “The Heiress.” Indeed, it’s Clift we remember more than the stars, Olivia de Havilland and Ralph Richardson.

Frank Capra was the great populist director of the Five Who Came Back and while he became most famous for making what are now called dramedies. he took a darker path entering and exiting WWII, first with “Meet John Doe” in 1941 and then with “It’s a Wonderful Life” in 1946 and “State of the Union” in 1948. While serious satire was a big part of his work before these, Capra’s bite was even sharper and his cautionary tales of personal and societal corruption even bleaker than before. Then he seemed to lose his touch with the times in his final handful of films. But for sheer entertainment and impact, his best works rank with anyone’s and for my tastes anyway those three feature films from ’41 through ’48 are unmatched for social-emotional import.

Before the war George Stevens made his name directing romantic and screwball comedies, even an Astaire-Rogers musical, and he came out of the war a socially conscious driven filmmaker. His great post-war films all tackle universal human desires and big ideas: “A Place in the Sun,” “Shane,” “Giant,” “The Diary of Anne Frank.” For my tastes anyway his films mostly lack the really nuanced writing and acting of his Five Came Back peers, and that’s why I don’t see him in the same category as the others. In my opinion Stevens was a very good but not great director. He reminds me a lot of Robert Wise in that way.

That brings us to John Huston. He was the youngest and most unheralded of the five directors who went off to war. After years of being a top screenwriter, he had only just started directing before the U.S. joined the conflict. His one big critical and commercial success before he made his war-effort documentaries was “The Maltese Falcon.” But in my opinion he ended up being the best of the Five Who Came Back directors. Let this list of films he made from the conclusion of WWII through his death sink in to get a grasp of just what a significant body of work he produced:

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

The Asphalt Jungle

Key Largo

The Red Badge of Courage

Heaven Knows Mr. Allison

Beat the Devil

Moby Dick

The Unforgiven

The Misfits

Freud

The List of Adrian Messenger

The Night of the Iguana

Reflections in a Golden Eye

Fat City

The Man Who Would Be King

Wiseblood

Under the Volcano

Prizzi’s Honor

The Dead

That list includes two war films, “The Red Badge of Courage” and “Heaven Knows Mr. Allison,” that are intensely personal perspectives on the struggle to survive when danger and death are all around you. Many of his other films are dark, sarcastic ruminations on how human frailties and the fates sabotage our desires, schemes and quests.

I believe Huston made the most intelligent, literate and best-acted films of the five directors who went to war. At least in terms of their post-war films. The others may have made films with more feeling, but not with more insight. Huston also took more risks than they did both in terms of subject matter and techniques. Since the other directors’ careers started a full decade or more before his, they only had a couple decades left of work in them while Huston went on making really good films through the 1970s and ’80s.

Clearly, all five directors were changed by what they saw and did during the war and their work reflected it. We are the ultimate beneficiaries of what they put themselves on the line for because those experiences led them to inject their post-war work with greater truth and fidelity about the world we live in. And that’s really all we can ask for from any filmmaker.

Hot Movie Takes: Alexander Payne’s ‘Downsizing’ promises to be a cinema feast

You can order signed copies by emailing me at leo32158@cox,net.

Here are links to some of my other “Downsizing” posts and articles:

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/17/the-incredible-s…s-60-years-apart/

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/07/31/stanley-kubrick-…ected-congruence/

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/08/28/downsizing-may-e…-cinema-universe/

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/04/01/lensing-april-1-…ous-film-to-date/

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/27/exclusive-on-ale…eese-witherspoon/

Movie buffs buzzing after early glimpse of Alexander Payne’s ‘Downsizing’

Director Alexander Payne, left, talks with Matt Damon before filming a scene for “Downsizing” in Omaha in April last year.

Alexander Payne’s next movie is already building some buzz, nine months ahead of its release.

Tuesday at the theater-owners convention CinemaCon, Paramount screened 10 minutes of footage from “Downsizing,” and audiences were reportedly blown away.

Payne’s sci-fi dramedy, parts of which were shot in Omaha last year, opens nationwide Dec. 22, a prime spot for movies seeking awards consideration.

“Downsizing,” starring Matt Damon, has been in the works for more than a decade. Payne and his writing partner, Jim Taylor, started the earliest version of the script in 2006. The film faced a few false starts along the way.

“It’s a movie that imagines what might happen if, as a solution to overpopulation and climate change, Norwegian scientists discover how to shrink organic material,” Payne said in an interview last spring. “The scientists propose to the world a 200- to 300-year transition from big to small as the only humane and inclusive solution to our biggest problem.”

In the film, Damon and Kristen Wiig play a married couple who decide to shrink themselves as a cost-saving measure.

The scale of the concept is new territory for the Omaha Oscar-winner, as are the bigger budget and heavy use of special effects.

In the clip screened at CinemaCon, Damon and Wiig attend a presentation about living the good life as a tiny person. An already-shrunk character played by Neil Patrick Harris makes the sales pitch. He lives in a dollhouse-sized mansion with his wife (played by Laura Dern). They get to live like kings for almost no money at all.

The convention clip also gave viewers the first look on what the shrinking process will look like. It apparently looks fantastic.

The Wrap reported that “the auditorium erupted in laughter at certain points throughout the clip, especially when the little miniature people came out of the shrinking machine. When the clip concluded, the audience cheered.”

Responses were across-the-board positive:

Variety: “‘Downsizing’ is something different entirely. It’s funny, to be sure, but it’s also Payne’s first foray into science fiction. Think of it as ‘Honey I Shrunk the Kids’ with a deeper social message.”

The Playlist: “Let’s be clear, Alexander Payne’s ‘Downsizing’ … was literally jaw-dropping. In a visual style and dramatic tone that is the most Kubrick-esque of his career, Payne screened what is effectively the first 10 minutes of the film. To say it’s one of the more original pieces of work I’ve seen in years is an understatement.”

Hollywood Elsewhere: “(The) CinemaCon preview of ‘Downsizing’ was awesome, brilliant, hilarious, sad and a tiny bit scary — an obvious Best Picture contender.”

The local reviews are good so far, too. Representatives of Aksarben Cinema got to see the footage. They said it’s amazing.

It’s of course impossible to judge a film on 10 minutes. But given the quality of Payne’s past work, the talent attached here, the warm reception the clip received and the prime holiday release Paramount is giving the film, this is one to maybe mark on your calendar.

Photos: Matt Damon, Kristen Wiig work on set in Omaha for Alexander Payne’s ‘Downsizing’

Director Alexander Payne plans a shot of the iconic La Casa sign at 4432 Leavenworth St, on Tuesday, April 12, 2016. Payne was filming his new movie, “Downsizing.” More photos.

Hot Movie Takes: John Huston, an appreciation

Hot Movie Takes

John Huston, an apprciation

By Leo Adam Biga, author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

When I originally posted about the subject of this Hot Movie Take, the late John Huston, I forgot to note that his work, though very different in tone, shares a penchant for unvarnished truth with that of Alexander Payne. Huston was a writer-director just like Payne is and he was extremely well-read and well-versed in many art forms, again just as Payne is. The screenplays for Huston’s films were mostly adaptations of novels, short stories and plays, including some famous ones by iconic writers, and the scripts for Payne’s films are mostly adaptations as well. Huston also collaborated with a lot of famous writers on his films, including Truma Capote and Arthur Miller. The work of both filmmakers shares an affinity for ambiguous endings. I think at his best Huston was more of a classic storyteller than Payne and his films more literate. Where Huston mostly made straight dramas, he showed a real flair for comedy the few times he ventured that way (“The African Queen,” “Beat the Devil,” “The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean” and “Prizzi’s Honor”). Payne insists that he makes comedies, though most would say he makes dramedies, a terrible descriptor that’s gained currency. More accurately, Payne’s comedy-dramas are satires. I think he’s more than capable of making a straight drama if he chose to, but so far he’s stayed true to himself and his strengths. If Payne is the ultimate cinema satirist of our tme, and I think he is, then Huston stands as the great film ironist of all time. With one using satire and the other using irony to great effect, their films get right to the bone and marrow of characters without a lot of facade. Just as it was for Huston, story and character is everything for Payne. And their allegiance to story and character is always in service to revealing truth.

Of all the great film directors to some out of the old studio system, only one, that craggy, gangly, hard angle of a man, John Huston, continued to thrive in the New Hollywood and well beyond.

It’s important to note Huston was a writer-director who asserted great independence even under contract. He began as a screenwriter at Universal and learned his craft there before going to work at Warner Brothers. But Huston was an accomplished writer long before he ever got to Hollywood. As a young man he found success as a journalist and short story writer, getting published in some of the leading magazines and newspapers of the day. Indeed, he did a lot things before he landed in Tinsel Town. He boxed, he painted, he became a horseman and cavalry officer in the Mexican uprisings, he hunted big gamma he acted and he caroused. His father Walter Huston was an actor in vaudeville before making it on the legitimate stage and then in films.

What he most loved though was reading. His respect for great writing formed early and it never left him. Having grown up the son of a formidable actor, he also respected the acting craft and the power and magic of translating words on a page into dramatic characters and incidents that engage and move us.

He admired his father’s talent and got to study his process up close. Before ever working in Hollywood, John Huston also made it his business to observe how movies were made.

But like most of the great filmmakers of that era, Huston lived a very full life before he ever embarked on a screen career. It’s one of the reasons why I think the movies made by filmmakers like Huston and his contemporaries seem more informed by life than even the best movies today. There’s a well lived-in weight to them that comes from having seen and done some things rather than rehashing things from books or film classes or television viewings.

Because of his diverse passions, Huston films are an interesting mix of the masculinity and fatalistic of, say. a Hemingway, and the ambiguity and darkness of, say, an F. Scott Fitzgerald or Eugene O’Neill. I use literature references because Huston’s work is so steeped in those traditions and influences. In film terms, I suppose the closest artists his work shares some kinship with are Wyler and John Ford, though Huston’s films are freer in form than Wyler’s and devoid of the sentimentality of Ford. As brilliantly composed as Wyler’s films are, they’re rather stiff compared to Huston’s. As poetic as Ford’s films are, they are rather intellectually light compared to Huston’s.

At Warners Huston developed into one of the industry’s top screenwriters with an expressed interest in one day directing his own scripts. Of all the Hollywood writers that transitioned to directing, he arguably emerged as the most complete filmmaker. While he never developed a signature visual style, he brought a keen intelligence to his work that emphasized character development and relationship between character and place. He made his directing invisible so as to better serve the story. When I think of Huston, I think of lean and spare. He perfected the art of cutting in the camera. He was precise in what he wanted in the frame and he got as close to what he had on the page and in his head as perhaps anyone who’s made feature-length narrative films. He did it all very efficiently and professionally but aesthetic choices came before any commercial considerations. He was known to be open to actors and their needs and opinions, but he was not easily persuaded to change course because he was a strong-willed artist who knew exactly what he wanted, which is to say he knew exactly what the script demanded.

His films are among the most literate of their or any era, yet they rarely feel stagy or artificial. From the start, Huston revealed a gift for getting nitty gritty reality on screen. He was also very big on location shooting when that was still more a rarity than not and he sometimes went to extreme lengths to capture the real thing, such as encamping in the Congo for “The African Queen.” Look at his “The Man Who Would Be King” and you’ll find it’s one of the last great epic adventure stories and Huston and Co.really did go to harsh, remote places to get its settings right.

The realism of his work is often balanced by a lyrical romanticism. But there are some notable exceptions to this in films like “Fat City.”

He sometimes pushed technical conventions with color experiments in “Moulin Rouge,” “Moby Dick” and “Reflections in a Golden Eye.”

As a young man learning the ropes, he reportedly was influenced by William Wyler and other masters and clearly Huston was a good student because right out of the gate with his first film as director, “The Maltese Falcon,” his work was fully formed.

In his first two decades as a writer-director, Huston made at least a half dozen classics. His best work from this period includes:

The Maltese Falcon

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

The Asphalt Jungle

Key Largo

The Red Badge of Courage

Heaven Knows Mr. Allison

Beat the Devil

Moby Dick

The Unforgiven

Huston remained a relevant director through the 1960s with such films as:

The Misfits

Freud

The List of Adrian Messenger

The Night of the Iguana

Reflections in a Golden Eye

But his greatest work was still ahead of him in the 1970s and 1980s when all but a handful of the old studio filmmakers were long since retired or dead or well past their prime. Huston’s later works are his most complex and refined:

Fat City

The Man Who Would Be King

Wiseblood

Under the Volcano

Prizzi’s Honor

The Dead

I have seen all these films, some of them numerous times, so I can personally vouch for them. There are a few others I’ve seen that might belong on his best efforts list, including “The Roots of Heaven.” Even a near miss like “The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean” is worth your time. And there are a handful of ’70s era Huston films with good to excellent reputations I’ve never gotten around to seeing, notably “The Kremlin Letter” and “The Mackintosh Man,” that I endeavor to see and judge for myself one day.

Three star-crossed iconic actors with Huston, Arthur Miller, Eli Wallach and Co. on the set of “The Misfits”

It would be easy for me to discuss any number of his films but I elect to explore his final and, to my tastes anyway, his very best film, “The Dead” (1987). For me, it is a masterpiece that distills everything Huston learned about literature, film, art, music, life, you name it, into an extraordinary mood piece that is profound in its subtleties and observations. For much of his career, Huston portrayed outward adventures of characters in search of some ill-fated quest. These adventures often played out against distinct, harsh urban or natural landscapes. By the end of his career, he turned more and more to exploring inward adventures. “The Dead” is an intimate examination of grief, love, longing and nostalgia. Based on a James Joyce short story, it takes place almost entirely within a private home during a Christmas gathering that on the surface is filled with merriment but lurking just below is bittersweet melancholia, particularly for a married couple stuck in the loss of their child. It is a tender tone poem whose powerful evocation of time, place and emotion is made all the more potent because it is so closely, carefully observed. Much of the inherent drama and feeling resides in the subtext behind the context. Discovering these hidden meaning sin measured parts is one of the many pleasures of this subdued film that has more feeling in one frame than any blockbuster does in its entirety. “The Dead” is as moving a meditation on the end of things, including human life, that I have ever seen.

Huston made the film while a very sick and physically feeble old man. He was in fact dying. But it might as well be the work of a young stallon because it’s that vital and rigorous. The fact that he was near death though gives his interpretation and expression of the story added depth and poignancy. He knew well the autumnal notes it was playing. The film starts his daughter Angelica Huston. It was their third and final collaboraton.

If you don’t know Huston the writer-director I urge you to seek out his work and even if you do you may discover he made films you didn’t associate with him. Just like we often don’t pay attention to the bylines of writers who author pieces we read and even enjoy, some of us don’t pay strict attention to who the directors of films are, even if we enjoy them. Some of you may even be more familiar with Huston’s acting than his directing. His turn in “Chinatown” is a superb example of character acting. My point is, whatever Huston means or doesn’t meant to you, seek out his work and put the pieces together of the many classics he made that you’ve seen and will make a point to see.

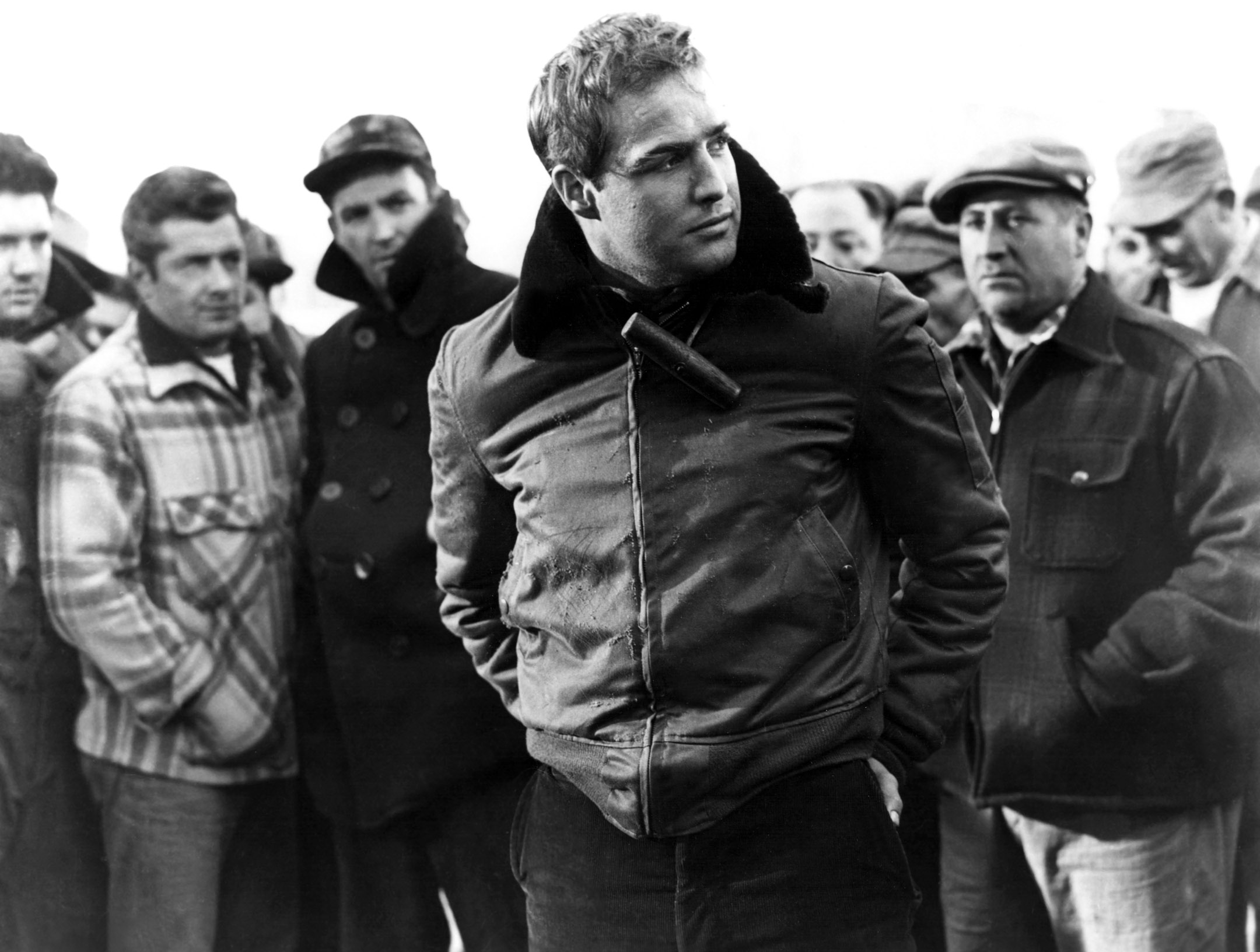

Hot Movie Takes Sunday: When cinema first seduced me – “On the Waterfront’

Hot Movie Takes Sunday

When cinema first seduced me – “On the Waterfront”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Borrowing from the title of a famous film book, I share in this hot cinema take how I lost my virginity at the movies. It wasn’t a person who stole my innocence and awakened my senses, it was a film, a very special film: “On the Waterfront.” Though in a manner of speaking you could say I gave it up to the film’s star, Marlon Brando.

It was probably the end of the 1960s or beginning of the 1970s when I first saw that classic 1954 film. I would have been 11 or 12 watching it on the home Zenith television set. The film still has a hold on me all these years later. It moves me to tears and exultation as an adult just as it did as a child. I’m sure that will never change no matter how many times I see it, and I’ve seen it a couple dozen times by now, and no matter how old I am when I revisit it.

Nothing could have prepared me for that first viewing though. I mean, it stirred things in me that I didn’t yet have words or meanings for. I remember lying on the living room’s carpeted floor and variously feeling sad, excited, aroused, afraid, angry, disenchanted, triumphant and, though I didn’t know the word at the time, ambivalent.

The power of that movie is in its extraordinary melding of words, images, ideas, faces, locations, actions and dramatic incidents. Great direction by Elia Kazan. Great photography by Boris Kaufmann. Great music by Leonard Bernstein. Great script by Budd Schulberg, Great ensemble cast from top to bottom. But it was Marlon Brando who undid me. I mean, he’s so magnetic and enigmatic at the same time. There’s a charm and mystery to the man, combined with an intensity and truth, that projects a palpable, visceral energy unlike anything I’ve quite felt since from a film performance. His acting is so real, spontaneous and connected to every moment that it evokes intense emotional immediate responses in me. It happened the first time I saw it and it still happens all these decades later. What I’m describing, of course, is the very intent of The Method Brando brought to Hollywood, thus forever changing screen acting by the new level of naturalism and truth he brought to many of his roles.

His Terry Malloy is an Everyman on the mob-controlled docks of New York. He looks like just any other working stiff or mug except he’s not because he’s an ex-prizefigher and his older brother Charley (Rod Steiger) is in the employ of waterfront boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb). The longshoremen can’t form a union and don;t dare to demand anything like decent work conditions or benefits as long as Friendly rules by threat and intimidation. In return for keeping the men in check, he and his crew take a cut of everything that comes in or goes out of those docks. And Terry, who’s part of Friendly’s mob by association, doesn’t have to lift a finger on the job. Not so long as he does what he’s told and keeps his mouth shut. A law enforcement investigation into waterfront racketeering has everyone on edge and the price for squealing is death.

A conflicted Terry arrives at a moral crossroads after being used by Friendly’s bunch to set-up a buddy, Jimmy Dolan, that henchmen throw off the roof of a brownstone. Already racked by guilt for being an accomplice in his friend’s death, Terry then falls for Dolan’s attractive sister, Edie (Eva Marie Saint), who’s intent on finding the men responsible for her brother’s killing. At the same time, the waterfront priest, Father Barry (Karl Malden), urges the longshoremen to stand up and oppose Friendly by organizing themselves and telling what they know to the authorities. Terry is questioned by investigators, one of whom detects his anguish. But he can’t bring himself to tell Father Barry or Edie the truth,

With Friendly feeling the heat, he applies increased pressure and goon tactics. Concerned that Terry may turn stool pigeon under Edie’s and Father Barry’s influence, he orders Charley to get his brother in line – or else. Terry refuses the warning and Charley pays the price. Terry then lays it all on the line and comes clean with Edie, Father Barry and the authorities. All of it leads to Terry being ostracized before a climactic confrontation with Friendly and his stooges.

“On the Waterfront” could have been a melodramatic potboiler in the wrong hands but a superb cast and crew at the peak of their powers made a masterpiece instead. It’s the unadorned humanity of the film that moves us and lingers in the imagination. Then there’s the powerful themes it explores. The film is replete with symbols and metaphors for the human condition, good versus evil and principles of sacrifice, loyalty and redemption. The story also reflects Kazan’s and Schulberg’s view that “ratting” is a sometimes necessary act for a greater good. Like Terry, Kazan became persona non grata to some for naming names before the House Un-american Activities Committee at the height of this nation’s Red Scare hysteria. Some have criticized Kazan for making a self-serving message picture that at the end celebrates the rat as hero.

The film has come under the shadow cast by Kazan’s actions. Some say his cooperating with HUAC directly or indirectly made him complicit in Hollywood colleagues getting blacklisted by the industry. However you feel about what he did or didn’t do and what blame or condemnation can be laid at his feet, the film is a stand the test of time work of social consciousness that works seamlessly within the conventions of the crime or mob film. I think considering everything that goes into a narrative movie, it’s as good a piece of traditional filmmaking to ever come out of America. There have been more visually stunning pictures, more epic ones, better written ones, but none that so compellingly and pleasingly put together all the facets that make a great movie and that so effectively get under our skin and touch our heart.

It would be a decade from the time I first saw “On the Waterfront” before I reacted that strongly to another film, and that film was “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

Hot Movie Takes Friday – Indie Film: UPDATED-EXPANDED

Hot Movie Takes Friday

Indie Film

UPDATED-EXPANDED

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

There’s a common misconception that indie films are something that only came into being in the last half-century when in fact indie filmmaking has been around in one form or another since the dawn of movies.

Several Nebraskans have demonstrated the indie spirit at the highest levels of cinema.

The very people who invented the motion picture industry were, by definition, independents. Granted, most of them were not filmmakers, but these maverick entrepreneurs took great personal risk to put their faith and money in a new medium. They were visionaries who saw the future and the artists working for them perfected a moving image film language that proved addictive. The original Hollywood czars and moguls were the greatest pop culture pushers who ever lived. Under their reign, the narrative motion picture was invented and it’s hooked every generation that’s followed. The Hollywood studio system became the model and center of film production. The genres that define the Hollywood movie, then and now, came out of that system and one of the great moguls of the Golden Age, Nebraska native Darryl F. Zanuck, was as responsible as anyone for shaping what the movies became by the projects he greenlighted and the ones he deep-sixed. The tastes and temperaments of these autocrats got reflected in the pictures their studios made but the best of these kingpins made exceptions to their rules and largely left the great filmmakers alone, which is to say they didn’t interfere with their work. If they did, the filmmakers by and large wouldn’t stand for it. After raising hell, the filmmakers usually got their way.

Zanuck made his bones in Hollywood but as the old studio system with its longterm contracts and consolidated power began to wane and a more open system emerged, even Zanuck became an independent producer.

The fat-cat dream-making factories are from the whole Hollywood story. From the time the major studios came into existence to all the shakeups and permutations that have followed right on through today, small independent studios, production companies and indie filmmakers have variously worked alongside, for and in competition with the established studios.

Among the first titans of the fledgling American cinema were independent-minded artists such as D.W. Griffith, Charles Chaplin and Douglas Faribanks, who eventually formed their own studio, United Artists. Within the studio system itself, figures like Griffith, Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Cecil B. De Mille, Frank Capra and John Ford were virtually unassailable figures who fought for and gained as near to total creative control as filmmakers have ever enjoyed. Those and others like Howard Hawks, William Wyler and Alfred Hitchcock pretty much got to do whatever they wanted on their A pictures. Then there were the B movie masters who could often get away with even more creatively and dramatically speaking than their A picture counterparts because of the smaller budgets and loosened controls on their projects. That’s why post-World War II filmmakers like Sam Fuller, Joseph E. Lewis, Nicholas Ray, Budd Boetticher and Phil Carlson could inject their films with all sorts of provocative material amidst the conventions of genre pictures and thereby effectively circumvent the production code.

Maverick indie producers such as David O. Selznick, Sam Spiegel and Joseph E. Levine packaged together projects of distinction that the studios wouldn’t or couldn’t initiate themselves. Several actors teamed with producers and agents to form production companies that made projects outside the strictures of Hollywood. Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster were among the biggest name actors to follow this trend. Eventually, it became more and more common for actors to take on producing, even directing chores for select personal projects, to where if not the norm it certainly doesn’t take anyone by surprise anymore.

A Nebraskan by the name of Lynn Stalmaster put aside his acting career to become a casting direct when he saw an opportunity in the changing dynamics of Hollywood. Casting used to be a function within the old studio system. As the studios’ contracted employee rosters began to shrink and as television became a huge new production center, Stalmaster saw the future and an opportunity. He knew just as films needed someone to guide the casting, the explosion of dramatic television shows needed casting expertise as well and so he practically invented the independent casting director. He formed his own agency and pretty much had the new field to himself through the 1950s, when he mostly did TV, on through the ’60s, ’70s’ and even the ’80s, when more of his work was in features. He became the go-to casting director for many of top filmmakers, even for some indie artists. His pioneering role and his work casting countless TV shows, made for TV movies and feature films, including many then unknowns who became stars, earned him a well deserved honorary Oscar at the 2017 Academy Awards – the first Oscar awarded for casting.

Lynn Stalmaster

Photo By Lance Dawes, Courtesy of AMPAS

In the ’50 and ’60s Stanley Kubrick pushed artistic freedom and daring thematic content to new limits as an independent commercial filmmaker tied to a studio. Roger Corman staked out ground as an indie producer-director whose low budget exploitation picks gave many film actors and filmmakers their start in the industry. In the ’70s Woody Allen got an unprecedented lifetime deal from two producers who gave him carte blanche to make his introspective comedies.

John Cassavetes helped usher in the indie filmmaker we identify today with his idiosyncratic takes on relationships that made his movies stand out from Hollywood fare.

Perhaps the purest form of indie filmmaking is the work done by underground and experimental filmmakers who have been around since cinema’s start. Of course, at the very start of motion pictures, all filmmkaers were by definition experimental because the medium was in the process of being invented and codified. Once film got established as a thing and eventually as a commerical industry, people far outside or on the fringes of that industry, many of them artists in other disciplines, boldly pushed cinema in new aesthetic and technical directions. The work of most of these filmmakers then or now doesn’t find a large audience but does make its way into art houses and festivals and is sometimes very influential across a wide spectrum of artists and filmmakers seeking new ways of seeing and doing things. A few of these experimenters do find some relative mass exposure. Andy Warhol was an example. A more recent example is Godfrey Reggio, whose visionary documentary trilogy “Koyaanisqatsi,” “Powaqqatsi” and “Naqoyqatsi” have found receptive audiences the world over. Other filmmakers, like David Lynch and Jim McBride, have crossed over into more mainstream filmmaking without ever quite leaving behind their experimental or underground roots.

Nebraska native Harold “Doc” Edgerton made history for innovations he developed with the high speed camera, the multiflash, the stroboscope, nighttime photography, shadow photography and time lapse photography and other techniques for capturing images in new ways or acquiring images never before captured on film. He was an engineer and educator who combined science with art to create an entire new niche with his work.

Filmmakers like Philip Kaufman, Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese and many others found their distinctive voices as indie artists. Their early work represented formal and informal atttempts at discovering who they are as

Several filmmakers made breakthroughs into mainstream filmmaking on the success of indie projects, including George Romero, Jonathan Kaplan, Jonathan Demme, Omaha’s own Joan Micklin Silver, Spike Lee and Quentin Taratino.

If you don’t know the name of Joan Micklin Silver, you should. She mentored under veteran studio director Mark Robson on a picture (“Limbo”) he made of her screenplay about the wives of American airmen held in Vietnamese prisoner of war camps. Joan, a Central High graduate whose family owned Micklin Lumber, then wrote an original screenplay about the life of Jewish immigrants on New York’s Lower East Side in the early 20th century. She called it “Hester Street” and she shopped it around to all the studios in Hollywood as a property she would direct herself. They all rejected the project and her stipulation that she direct. Every studio had its reasons. The material was too ethnic, too obscure, it contained no action, it had no sex. Oh, and she insisted on making it in black and white,which is always a handy excuse to pass on a script. What the studios really objected to though was investing in a woman who would be making her feature film directing debut. Too risky. As late as the late 1970s and through much of the 1980s there were only a handful of American women directing feature and made for TV movies. It was a position they were not entrusted with or encouraged to pursue. Women had a long track record as writers, editors, art directors, wardrobe and makeup artists but outside of some late silent and early sound directors and then Ida Lapino in the ’50s. women were essentially shut out of directing. That’s what Joan faced but she wasn’t going to let it stop her.

Long story short, Joan and her late husband Raphael financed the film’s production and post themselves and made an evocative period piece that they then tried to get a studio to pick up, but to no avail. That’s when the couple distributed the picture on their own and to their delight and the industry’s surprise the little movie found an audience theater by theater, city by city, until it became one of the big indie hits of that era. The film’s then-unknown lead, Carol Kane, was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Actress. The film’s success helped Joan get her next few projects made (“Between the Lines,” “Chilly Scenes of Winter”) and she went on to make some popular movies, including “Loverboy,” and a companion piece to “Hester Street” called “Crossing Delancey” that updated the story of Jewish life on the Lower East Side to the late 20th century. Joan later went on to direct several made for cable films. But “Hester Street” will always remain her legacy because it helped women break the glass ceiling in Hollywood in directing. Its historic place in the annals of cinema is recognized by its inclusion in the U.S. Library of Congress collection. She’s now penning a book about the making of that landmark film. It’s important she document this herself, as only she knows the real story of what obstacles she had to contend with to get the film made and seen. She and Raphael persisted against all odds and their efforts not only paid off for them but in the doors it opened for women to work behind the camera.

The lines between true independent filmmakers and studio-bound filmmakers have increasingly blurred. Another Omahan, Alexander Payne, is one of the leaders of the Indiewood movement that encompasses most of the best filmmakers in America. Payne and his peers maintain strict creative control in developing, shooting and editing their films but depend on Hollywood financing to get them made and distributed. In this sense, Payne and Co. are really no different than those old Hollywood masters, only filmmakers in the past were studio contracted employees whereas contemporary filmmakers are decidedly not. But don’t assume that just because a filmmaker was under contract he or she had less freedom than today’s filmmakers. Believe me, nobody told Capra, Ford, Hitchcock, Wyler, or for that matter Huston of Kazan, what to do. They called the shots. And if you were a producer or executive who tried to impose things on them, you’d invariably lose the fight. Most of the really good filmmakers then and now stand so fiercely behind their convictions that few even dare to challenge them.

But also don’t assume that just because an indie filmmaker works outside the big studios he or she gets everything they want. The indies ultimately answer to somebody. There’s always a monied interest who can, if push comes to shove, force compromise or even take the picture out of the filmmaker’s hands. Almost by definition indie artists work on low budgets and the persons controlling those budgets can be real cheapskates who favor efficiency over aesthetics.

Payne is the rarest of the rare among contemporary American filmmakers in developing a body of work with a true auteurist sensibility that doesn’t pander to formulaic conventions or pat endings. His comedies play like dramas and they’re resolutely based in intimate human relationships between rather mundane people in very ordinary settings. Payne avoids all the trappings of Hollywood gloss but still makes his movies engaging, entertaining and enduring. Just think of the protagonists and plotlines of his movies and it’s a wonder he’s gotten any of them made:

Citizen Ruth–When a paint sealer inhalant addict with a penchant for having kids she can’t take care of gets pregnant again, she becomes the unlikely and unwilling pivot figure in the abortion debate.

Election–A frustrated high school teacher develops such a hate complex for a scheming student prepared to do anything to get ahead that he rigs a student election against her.

About Schmidt–Hen-pecked Warren Schmidt no sooner retires from the job that defined him than his wife dies and he discovers she cheated on him with his best friend. He hits the road to find himself. Suppressed feelings of anger, regret and loneliness surface in the most unexpected moments.

Sideways–A philandering groom to be and a loser teacher who’s a failed writer go on a wine country spree that turns disaster. Cheating Jack gets the scare of his life. Depressed Miles learns he can find love again.

The Descendants–As Matt King deals with the burden of a historic land trust whose future is in his hands, he learns from his oldest daughter that his comatose wife cheated on him. With his two girls in tow, Matt goes in search of answers and revenge and instead rediscovers his family.

Nebraska–An addled father bound and determined to collect a phantom sweepstakes prize revisits his painful past on a road trip his son David takes him on.

Downsizing–With planet Earth in peril, a means to miniaturize humans is found and Paul takes the leap into this new world only to find it’s no panacea or paradise.

Payne has the cache to make the films he wants to make and he responsibly delivers what he promises. His films are not huge box office hits but they generally recoup their costs and then some and garner prestige for their studios in the way of critical acclaim and award nominations. Payne has yet to stumble through six completed films. Even though “Downsizing” represents new territory for him as a sci-fi visual effects movie set in diverse locales and dealing with global issues, it’s still about relationships and the only question to be answered is how well Payne combines the scale with the intimacy.

Then there are filmmakers given the keys to the kingdom who, through a combination of their own egomania and studio neglect, bring near ruin to their projects and studios. I’m thinking of Orson Welles on “The Magnificent Ambersons,” Francis Ford Coppola on “One from the Heart”, Michael Cimino on “Heaven’s Gate,” Elaine May on “Ishtar” and Kevin Costner on “Thw Postman” and “Waterworld.” For all his maverick genius, Welles left behind several unfinished projects because he was persona non grata in Hollywood, where he was considered too great a risk, and thus he cobbled together financing in a haphazard on the fly manner that also caused him to interrupt the filming and sometimes move the principal location from one site to another, over a period of time, and then try to match the visual and audio components. Ironically, the last studio picture he directed, “Touch of Evil,” came in on budget and on time but Universal didn’t understand or opposed how he wanted it cut and they took it out of his hands. At that point in his career, he was a hired gun only given the job of helming the picture at the insistence of star Charlton Heston and so Welles didn’t enjoy anything like the final cut privileges he held on “Citizen Kane” at the beginning of his career.

Other mavericks had their work compromised and sometimes taken from them. Sam Peckinpah fought a lot of battles. He won some but he ended up losing more and by the end his own demons more than studio interference did him in.

The lesson here is that being an independent isn’t always a bed of roses.

Then again, every now and then a filmmaker comes out of nowhere to do something special. Keeping it local, another Omahan did that very thing when a script he originally wrote as a teenager eventually ended up in the hands of two Oscar-winning actors who both agreed to star in his directorial debut. The filmmaker is Nik Fackler, the actors are Martin Landau and Ellen Burstyn and the film is “Lovely, Still.” It’s a good film. It didn’t do much business however and Fackler’s follow up film,” Sick Birds Die Easy,” though interesting, made even less traction. His film career is pretty much in limbo after he walked away from the medium to pursue his music. The word is he’s back focusing on film again.

Other contemporary Nebraskans making splashes with their independent feature work include actor John Beasley, actress Yolonda Ross and writer-directors Dan Mirvish, Patrick Coyle, Charles Hood and James E. Duff.

These folks do really good work and once in a while magic happens, as with the Robert Duvall film “The Apostle” that Beasley co-starred in. It went on to be an indie hit and received great critical acclaim and major award recognition. Beasley is now producing a well-budgeted indie pic about fellow Omahan Marlin Briscoe. Omahan Timothy Christian is financing and producing indie pics with name stars through his own Night Fox Entertainment company. Most of the films these individuals make don’t achieve the kind of notoriety “The Apostle” did but that doesn’t mean the work isn’t good. For example, Ross co-starred in a film, “Go for Sisters,” by that great indie writer-director John Sayles and I’m sure very few of you reading this have heard of it and even fewer have seen it but it’s a really good film. Hood’s comedy “Night Owls” stands right up there with Payne’s early films. Same for Duff’s “Hank and Asha.”

Indie feature filmmaking on any budget isn’t for the faint of heart or easily dissuaded. It takes guts and smarts and lucky breaks. The financial rewards can be small and the recognition scant. But it’s all about a passion for the work and for telling stories that engage people.

More Hot Movie Takes

More Hot Movie Takes

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film

Dennis O’Keefe

These riffs are about some very different cinema currents but they’re all inspired by recent screen discoveries I made once I put my movie snobbery in check.

My first riff concerns an actor from Old Hollywood I was almost entirely unfamiliar with and therefore I never thought to seek out his work: Dennis O’Keefe. I discovered O’Keefe only because I finally made an effort to watch some of Anthony Mann’s stellar film noirs from the 1940s. O’Keefe stars in two of them – T-Men” (1947) and “Raw Deal” (1948). Neither is a great film but the former has a very strong script and the latter is like an encyclopedia of noir and they both feature great cinematography by John Alton and good performances across the board. These are riveting films that stand up well against better known noirs, crime and police pics.

Whatever restrictions the filmmakers faced making these movies for small poverty eow studios they more than made up for with their inventiveness and passion.

As wildly atmospheric and evocative as Alton’s use of darkness, light and shadow is in these works, it’s O’Keefe’s ability to carry these films that’s the real revelation for me. I find him to be every bit as charismatic and complex as Humphrey Bogart. James Cagney, Robert Mitchum and other bigger name tough guys of the era were, and I’m certain he would have carried the best noirs they helped make famous. O’Keefe reminds me of a blend between Bogart and Cagney, with a touch of another noir stalwart, William Holden, thrown in. Until seeing him in these two pictures along with another even better pic, “Chicago Syndicate” (1955) directed by the underrated Fred F. Sears, who is yet another of the discoveries I’m opining about here, I had no idea O’Keefe delivered performances on par with the most iconic names from the classic studio system era. It just goes to show you that you don’t know what you don’t know. Before seeing it for myself – if you’d tried to tell me that O’Keefe was in these other actors’ league I would have scoffed at the notion because I would have assumed if this were so he’d have come to my attention by now. Why O’Keefe never broke through from B movies to A movies I’ll never know, but as any film buff will tell you those categories don’t mean much when it comes to quality or staying power. For example, the great noir film by Orson Welles Touch of Evil was a B movie all the way in terms of budget, source material, theme and perception but in reality it was a bold work of art by a master at the top of his game. It even won an international film prize in its time, though it took years for it to get the respect it deserved in America.

Like all good actors, O’Keefe emphatically yet subtly projects on screen what he’s thinking and feeling at any given moment. He embodies that winning combination of intelligence and intuition that makes you feel like he’s the smartest guy in the room, even if he’s in a bad fix.

My admittedly simplistic theory about acting for the screen is that the best film/TV actors convey an uncanny and unwavering confidence and veracity to the camera that we as the audience connect to and invest in with our own intellect and emotion. That doesn’t mean the actor is personally confident or needs to play someone confident in order to hook us, only that within the confines of playing characters they make it seem as though they believe every word they say and every emotion they express. Well, O’Keefe had this in spades.

Now that O’Keefe is squarely on my radar, I will search for of his work. I recommend you do the same.

By the way, another fine noir photographed by John Alton, “He Walks by Night,” starring Richard Basehart, may have been directed, at least in part, by Mann. Alton’s work here may be even more impressive than in the other films. The climactic scene is reminiscent of “The Third Man,” only instead of the post-war Vienna streets and canals, the action takes place in the Los Angeles streets and sewers. I must admit I was not familiar with Alton’s name even though I’d seen movies he photographed before I ever come upon the Mann trilogy. For example, Alton’s last major feature credit is “Elmer Gantry,” a film I’ve seen a few times and always admired. He also did the great noir pic “The Big Combo” directed by Joseph E. Lewis. And he lit the great dream sequence ballet in “”An American in Paris,” for which he won an Oscar. Now I will look at those films even more closely with respect to the photography, though I actually do remember being impressed by the photography in “Big Combo” and, of course, the dream sequence in “Paris.”

Alton was an outlier in going against prevailing studio practices of over-lighting sets. He believed in under-lighting and letting the blacks and greasy help set mood. The films he did are much darker, especially the night scenes, than any Hollywood films of that time. He studied the work of master painters to learn how they controlled light and he applied his lessons to the screen.

It turns out that Alton left Hollywood at the peak of his powers because he got fed up with the long hours and the many fights he had with producers and directors, many of whom insisted on more light and brighter exposures. Alton usually got his way because he knew his stuff, he worked very fast and he produced images that stood out from the pack. Apparently he just walked away from his very fine career sometime in the early 1960s to lead a completely distant but fulfilling life away from the movies.

Alton setting up a shot in “Raw Deal”

With actress Leslie Caron – “An American In Paris

Regarding the aforementioned “Chicago Syndicate,” it’s a surprisingly ambitious and labyrinthian story told with great verve and conviction by Fred Sears. It’s a neat bridge film between the very composed studio bound tradition and the freer practical location tradition. Sears was another in a long line of B movie directors with great skill who worked across genres in the 1930s through 1950s period. I watched a bit of a western he did and it too featured a real flair for framing and storytelling. His work has some of the great energy and dynamic tension of Sam Fuller and Budd Boetticher from that same period. I can’t wait to discover more films by Sears.