Archive

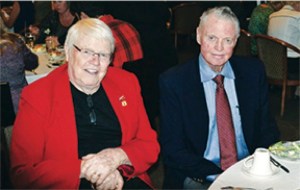

Kathy “Scout” Pettersen and Beverly Reicks Equality and love win

It’s funny how things once considered taboo, unthinkable, and unlawful become accepted practices. if not by everyone (Where is there one hundred percent consensus on anything?) then by the vast majority of us. Gay marriage is certainly one of those societal shifts. As the gay rights movement took hold and most of us came to terms with the fact that we have gay individuals in our lives whom we like or love or respect, ideas about same sex unions moved the public and private needle about this basic human and civil right little by little until what was thought impossible became practical, fair, lawful, and right. This is a piece I did about the women who became the first legally sanctioned same sex married couple in Douglas County, Nebraska.

Kathy “Scout” Pettersen and Beverly Reicks

Equality and love win

The kiss sealing their I-do’s graced the Omaha World-Herald’s front page and many other media platforms.

The couple, who share a home in Benson, waited years for legislation to catch up with public opinion They kept close tabs on the same-sex marriage debate. The morning their lives changed Pettersen was at The Bookworm, where she manages the children’s department, and Reicks, National Safety Council, Nebraska president and CEO, was getting blood work done at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

After hearing initial reports of the court reaching a decision, Reicks joined Pettersen at the bookstore. Once the 5-4 ruling in favor of marriage equality was confirmed, the pair drove to the courthouse for a license. Surrounded by hungry media, supportive staff and friends, they opted for an impromptu civil ceremony.

“We were greeted just with an abundance of joy and happiness,” Reicks says. “It was just really cool.”

“The reception was really warm. Everyone smiling and congratulatory. Lots of hugs from people I’d never met. It kind of made up for the disappointment I experienced in Neb. in 2000,” Pettersen says, referring to voters passing Initiative 416 prohibiting same-sex unions.

“It was troubling people thought certain people should be without civil rights,” Reicks says of the status quo that prevailed here.

Nebraska District Court Judge Joseph Battalion twice ruled the ban unconstitutional. A state appeal resulted in a stay that left gay couples in limbo until this summer’s milestone federal decision.

The couple’s friend, County Clerk Tom Cavanaugh, paid for their license. More friends witnessed the proceedings.

“We were just really honored so many people came through for us,” Pettersen says. “It was just really wonderful.”

“It was beyond what I ever imagined,” Reicks adds.

With the paperwork signed, Chief Deputy Clerk Kathleen Hall nudged the pair to give the media a marriage to cover. Pettersen and Reicks obliged. The lights, cameras and mics made for a surreal scene.

“I felt like I was in a whirlwind,” Pettersen recalls. “I felt like a celebrity,” Reicks says.

After basking in applause and cheers, the newlyweds answered reporters’ questions. Congrats continued outside. The couple celebrated with friends and family at La Buvette and Le Bouillon.

“It was an all-day, into-the-night celebration,” Pettersen says. “Lots of toasting.”

Reasons to celebrate extended to finally being accorded rights long enjoyed by opposite sex couples. Pettersen has an adopted daughter, Mia, and Reicks says, “Now she’s truly my step-daughter.” Recently filling out joint documents, Pettersen says, “I checked the married box for the first time without any hesitation or doubt. That was a very big deal to me. I couldn’t stop smiling it felt so good.”

Reicks reminds, “We owe a debt of gratitude to the plaintiffs who took these cases where they needed to go. They were brave enough to come forward and take up the challenge. We took advantage of the moment they created.”

“We reaped the benefits of their hard work,” Pettersen says. “I never thought I would see this in my lifetime. I do feel like we’re a part of history.”

Contrary to opponents’ fears, Reicks says, “The world did not come to an end because some gay and lesbian couples got married.”

Pettersen says It just all proves “love wins.”

Sarpy County, Nebraska: Rewriting the playbook for economic development.

The Sarpy County boom is the focus of this new piece I contributed to for B2B Omaha Magazine ((http://omahamagazine.com/category/publications/b2b-magazine/),

Once boasting only sleepy rural charms, quaint main streets and Offutt Air Force Base mystique, Sarpy County has awakened to a boom of residents, businesses and amenities. No longer a nondescript boondocks, this little county-that-could is now a magnet with on-the-map attractions. The state’s smallest county by land size claims the third largest population – 170,000, trailing only Douglas County on its northern border and Lancaster County to the west. Sarpy’s seeing the most dramatic growth of any Nebraska county. The surge is not slowing either.Greater Metropolitan Omaha offerings are enhanced by Sarpy’s entertainment venues, shopping centers, historic sites, parks and trails, making Eastern Nebraska a tourist stop and stay-cation spot.

Sarpy County Tourism director Linda Revis isn’t surprised the area’s being discovered. “The more you have to offer, the more you have to see, the more you have to do, the better and more well known you become,” she says. Sarpy’s five communities – Bellevue, Papillion, La Vista, Gretna and Springfield – benefit from the explosion, whether in houses built, businesses opening or tax revenues flowing into city coffers. Revis says, “We’re in the best location. We’ve got Omaha and Lincoln as neighbors. We’re on Interstate 80 and Interstate 29. We’re an easy destination to get to. We can be the hub and they can be the spokes.”

In a if-you-build-it-they-will-come spurt, the city’s added many must-do attractions. Sumtur Amphitheater presents concerts, plays and movies. A downtown market for local artisans and boutique owners and the new Midlands Place shopping center add engaging sites to Shadow Lake Towne Center, Papio Bay Aquatic Center, Papio Fun Park and golf courses-driving ranges. Fishing, boating, camping, hiking, biking enthusiasts flock to Walnut Creek Recreation Area. Prairie Queen Recreation Area is a popular new multi-use water-based outdoor retreat. The region’s only Triple A baseball club, the Omaha Storm Chasers, draws some 390,000 fans to Werner Park each spring-summer. The anticipated boom in housing-business development surrounding the park has not yet materialized but city-county officials expect it will soon. For history buffs, Sautter House is a 19th century farm dwelling and Portal School is a one-room schoolhouse. Papillion Days Festival is a weeklong celebration. Belvedere Hall serves authentic Polish dinners, music and dance.

Sarpy’s dynamic rise as a place people want to invest and do business in is symbolized by the new $25 million SAC Federal Credit Union headquarters and $200 million Fidelity Investments data center. Yahoo and other name company data processing centers give Sarpy a Silicon Prairie signature. A site opening this spring west of Papillion, the VA’s 236-acre Omaha National Cemetery, is expected to draw visitors from all around.

Sarpy’s managed adding big-time features without sacrificing small town character. Balancing bucolic with bustle takes planning. Bellevue’s bursting at the seams with things to do and places to see. Old Towne features the Historic Log Cabin, Old Presbyterian Church, Fontenelle Bank and Omaha and Southern Railroad Depot. Bellevue Little Theatre has produced stage works since 1968. For natural splendor there’s 1,400-acre Fontenelle Forest. Also Gifford Farm and Bellevue Berry & Pumpkin Patch. Haworth Park has multiple recreation amenities. Hitting the links is easy with Willow Lakes and Tregaron Golf Course. Film buffs get their fix at Twin Creek Cinema. Moonstruck Meadery is a new addition to the robust artisan spirits scene. Offfutt’s value-added impact is large. “It’s amazing how many people who serve at Offutt choose to stay or come back,” Revis says. “People want to live in these great communities.”

Embassy Suites by Hilton Omaha La Vista Hotel & Conference Center is a crossroads for tourists and event attendees. Nearby attractions include Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, Lucky Bucket Brewing Company/Cut Spike Distillery, Patriarch Distillers, Nebraska Brewing Company Tap Room, La Vista Falls Golf Course, Defy Gravity trampoline park and Brentwood Square’s shops, services and eateries. Iconic outdoor outfitter Cabela’s superstore features Disney-quality dioramas, the two-story Conservation Mountain with running waterfalls and stream, trout pond and wild game displays and a 34,000-gallon, walk-through aquarium stocked with freshwater fish.

La Vista anticipates a spike once the Nebraska Multisport Complex is built on 184 acres to encompass a natatorium with Olympic regulation pools, an indoor-outdoor tennis center and soccer fields with field turf and lighting. The facilities will be available to local teams, clubs, schools and nonprofits. Hosting regional-national tournaments is possible. Projections estimate the complex generating $17.8 million in new economic impact and attracting 1.2 million visitors annually.

Gretna’s home to some of Sarpy’s biggest draws. No. 1 is Nebraska Crossing Outlets. The $112 million, 335,000-square-foot mall featuring buzz-worthy brand name stores unavailable elsewhere in the region, did $140 million in sales and 4 million shopper visits its first year of operation in 2013-14. Sales and visits trended up last year. A $15 million expansion adding more stores is to open by Christmas. Pumpkin patches are big business in ag tourism and Vala’s Pumpkin Patch has cornered the area market. The 55-acre site welcomes 200,000-plus visitors during its September-October run. A meditative getaway awaits at Holy Family Shrine atop a hill above the scenic Platte Valley. The 23-acre sanctuary features serene gardens, walking paths, visitor’s center and chapel.

Hidden treasures abound in Springfield. Indulge creative interests at Weiss Sculpture Garden and Studio and Springfield Artworks. Satisfy a sweet tooth at Springfield Drug’s vintage soda fountain. Commune with nature’s bounty at Soaring Wings Vineyard & Brewing. The great outdoors is on tap, too, at Mopac Trailhead and Nature Center. South Sarpy development is the county’s next horizon opportunity.

Tourism maven Linda Revis says the people make the difference. “You go to any of our attractions or venues and you will not find friendlier more welcoming people anywhere. We work at being welcoming and it pays off a hundred-fold.”

Sarpy County, Nebraska

Rewriting the playbook for economic development.

In 1999, an online-banking company with a nonsensical name built a sprawling operation center next to the I-80 corridor on the edge of Papillion. Baffled passing commuters wondered how long a company named “PayPal” could possibly survive.

Six years later—to the delight of the region’s outdoor enthusiasts—Cabela’s opened a 128,000-square-foot sportsmen’s paradise that transformed the Cornhusker Street exit along I-80 into a bustling retail hotspot.

As the companies moved into the area, so did the employees, and the shoppers. Once boasting only sleepy rural charms, quaint main streets, and Offutt Air Force Base mystique, Nebraska’s smallest county by land mass is now also its fastest growing.

Indeed, while the rest of the state lost 3% of its population (or 55,000 people) between 2010 and 2014, Sarpy County added 13,000 people—an 8% increase.

How did it happen? Is there something to be learned by Nebraska’s other 92 counties?

Sarpy’s formula was a mix of nature and nurture: Aggressive leaders with vision and a willingness to deal. The good fortune of having open land next to a major metropolitan area and one of the nation’s major east-west corridors. Lots of nearby suburbanites with cash. Also, an educated work force within driving distance.

It was a perfect economic storm that even pulled off the outrageous and unthinkable: Dragging the Omaha Royals into the suburban Sarpy playground of the Omaha Stormchasers.

And now, in 2016, it’s all about synergy. Momentum. Winning begets more winning.

Ernie Goss, a Creighton University professor of economics, says that when county leaders are successful in building a concentration of development like the one in Sarpy County, it becomes a catalyst for more growth.

“There’s the impact of what we call clustering, Goss says.

The perpetual motion machine is paying off for the county and state. PayPal alone generated $736,930.00 in tax revenue in 2014, more than any other commercial business in the region.

Goss says the presence of PayPal and Cabela’s, among others, has undoubtedly propelled more development. After all, people want to be where the jobs and rooftops are.

There’s a lot to be said for clustering and that’s what we’re seeing out there,” he says.

Embassy Suites Conference Center in La Vista, developed in 2004, has brought in tourism dollars from conventions and weddings. Those tourism dollars also mean more people viewing the city, which builds awareness of the hotel and convention center, which, of course, increases chances that people will spread the word to other shoppers and convention organizers.

Goss says the boom will continue as long as the benefits of providing essential services—such as sewers and roads—in support of new development exceeds the marginal costs. Once those infrastructure elements are in place, he says, the marginal costs tend to decrease and that, in turn, spurs more development.

“It’s the initial development that’s very costly in providing things like fire and police services and other government services.”

Typically, he says, providing services becomes cheaper as the area grows more densely populated. That’s what’s happening in Sarpy County, where a growing resident and business tax base is helping make development cost effective.

The area also benefits from ready access to interstate highways that feed into the Omaha-Lincoln metroplex. Goss says Sarpy is situated just enough outside the urban congestion sprawl to give it a semi-country, away-from-it-all appeal while being near enough to still share in the big city orbit.

“It has a lot to do with interstate access,” he says.

And convenience.

“A lot of folks out west of Omaha find it easier driving to a conference at the Embassy Suites in La Vista than having to drive to the Embassy Suites in the Old Market,” Goss says. “That’s certainly part of it.”

All this growth, too, has come amid a national economy that has generally lagged. But, as the economy sputters, interest rates remain low. In the environment of the last decade, the cost and major development has remained lower as interest rates continue to hover around 4%.

The surge is not slowing.

La Vista anticipates yet another spike once the Nebraska Multisport Complex is built on 184 acres to encompass a natatorium with Olympic regulation pools, an indoor-outdoor tennis center, and soccer fields with field turf and lighting. The facilities will be available to local teams, clubs, schools, and nonprofits. Hosting regional-national tournaments is a massive money generator as families follow players for long weekends of play. Projections estimate the complex would generate $17.8 million in new economic impact and attracting 1.2 million visitors annually.

The win streak extended down the road to the edge of Gretna, where the massive Nebraska Crossing Outlets defied the doubters by doing $140 million in sales in its first year of operation. Within a year of its 2013 opening, the $112 million, 335,000-square-foot mall featuring buzz-worthy brand name stores was planning a major expansion. A new $15 million complex of stores is scheduled to open by Christmas.

Karen Gibler, president of the Sarpy County Chamber of Commerce, says there soon will be announcements about coming neighborhoods and businesses spurred by the new Highway 34 bridge, 84th Street developments, new I-80 exits, and planned sewer and transportation projects.

Gibler cites many reasons why investors and residents choose to work and live there:

“Quality of education and life keeps residents looking to move into our area,” she says. “This growth has opened the eyes of developers. Our leadership in the cities and county are a contributing factor. Land availability and easy access to good highways and the interstate make it easy to access from around the area.” Smart planning helps, as do plentiful jobs and affordable home prices. And people feel safe.”

That success has brought recognition. Papillion now ranks second on Money Magazine’s Best Places to Live for its high median income ($75,000), job growth (10%), thriving cultural life, and great access to the big-city amenities of Omaha.

National awards show up in national magazines and websites. People and companies looking for good homes read about this happenin’ place called Sarpy County in Nebraska.

And so, the wheels of progress keep on turning.

Once you can get it going, Goss says, “one activity draws another activity or one company draws another company.

“They have it all going in the right direction right now,” Goss says.

Lew Hunter’s small town Nebraska boy made good in Hollywood story is a doozy

Of all the Hollywood greats Nebraska has produced, and there are far more than you think, Lew Hunter may boast the most impressive career behind the camera outside of Darryl Zanuck from Tinsletown’s Golden Age. Hunter’s career stacks up well, too, among more more recent Hollywood players from here, such as Joan Micklin Silver and Alexander Payne. While it’s true Hunter never ran a major studio the way Zanuck did and has never directed a film the way Silver and Payne have, he did hold high executive level positions at each of the three major broadcast televison networks and at various studios. And like Zanuck, Silver and Payne, he’s written and produced movies. But he’s also done some singular things that stand him alone from his predecessor and peers. For example, he’s taught a well-regarded screenwriting class at UCLA since 1979, “Screenwriting 434,” that became the title and basis for his best-selling book about how to write screenplays. He’s also conducted many screenwriting workshops or seminars. He annually hosts the Superior Screenwriting Colon at his home in Superior, Neb., near his childhood home of Guide Rock. Unlike the vast majority of Nebraskans who’ve made a name for themselves in film and television, Hunter never lost touch with his Midwest origins and some 15 years ago or so he and his wife Pamela departed the Left Coast to move back to his roots.

He’s now the subject of a new documentary, Once in a Lew Moon, showing at the Omaha Film Festival.

On this blog you can find an earlier profile I wrote about Lew that drew on my being embedded in his screenwriting colony for several days.

NOTE: Thanks to Lonnie Senstock and Bill Blauvelt for providing some of the photos here.

Lew Hunter

Lew Hunter’s small town Nebraska boy made good in Hollywood story is a doozy

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the March 2016 issue of the New Horizons

Nestled at the bottom of Eastern Nebraska, about a three-hour drive from Omaha, the sleepy hamlet of Superior is home to one-time Hollywood Player Lew Hunter. Pushing 81 and retirement now, he still exerts enough influence to bring Tinseltown types to this isolated spot. Growing up a Neb. farm boy not far from there, Hunter dreamed of doing something in show business and he did as a television network and Hollywood studio executive. producer, screenwriter.

He’s on the short list of Nebraskans with major Hollywood credits. He isn’t as well known as some as his success came behind the camera, not in front of it. Not since Darryl Zanuck’s mogul days did a native reside so far within Hollywood’s inside circle as Hunter. Of past screen legends from Neb., he says, “These people were role models for me.”

Hunter’s a role model himself for having programmed popular network shows in the 1960s and 1970s that still draw viewers on Nick at Nite. Some mini-series and TV movies he shepherded for the networks were sensations in their time. Three movies he wrote, two of which he produced himself, earned huge shares and generated much discussion for their sensitive treatment of hard issues.

Site of the Superior Screenwriting Colony

A full life and an amazing career

Hunter’s the first to tell you he’s led one helluva life.– one as big as his oversized personality. Given where he came from, his career seems unlikely, but a desire to prove himself drove him to succeed.

Throughout the Great Depression and Second World War, he was enamored by the movies and radio. Then, during the Cold War and Baby Boom, he fell under TV’s spell.

Weaned on MGM, RKO and Paramount musicals – the only motion pictures his mother allowed him to see – he projected himself into the fantasies he saw in the lone theater in his hometown of Guide Rock. He imagined himself up there on the silver screen.

“I wanted to be Fred Astaire so bad. I danced with a pitchfork, and the pitchfork was Ginger Rogers.”

The barnyard filled in for a ballroom or nightclub.

The fact that Hunter went on to enjoy a storybook career rubbing shoulders with the likes of Astaire and other stars does not escape him. He knows how fortunate he was to create top-rated movies of the week. He’s grateful to be emeritus chairman and screenwriting professor at UCLA and to have written a book based on his class, Screenwriting 434, that’s the bible for cracking the scriptwriting code.

Some of his students have enjoyed major film-TV careers, including Oscar-winner Alexander Payne, one of dozens of great screenwriters and directors Hunter’s had as guests for his class. Those sessions have featured everyone from the late Billy Wilder and Ernest Lehman to William Goldman and Oliver Stone.

Hunter’s the subject of a new documentary, Once in a Lew Moon. It portrays his love of the writing craft and writers and the reciprocal love writers feel for him. The feature-length film by fellow Neb. native Lonnie Senstock premiered at UCLA, where Hunter’s retiring after this quarter. The doc screens at the Omaha Film Festival on March 12.

This once big wheel and still beloved figure in Hollywood gave up that lifestyle years ago when he and his wife Pamela settled near his boyhood origins to make their home in Superior. Twice a year there he convenes the Superior Screenwriting Colony, an immersive two-week workshop for aspiring and emerging film-TV writers. He leads it in an inimitable style that is equal parts Billy Graham, Big Lebowski and Aristotle on the Great Plains.

This prodigiously educated and well-read man once considered entering the ministry. He long served as the lay leader of a Methodist congregation. He does treat screenplays with a reverence usually reserved for the scriptures. When he gets rolling about scene structure and character development, he might as well be a preacher. Far from being a choir boy though, this let-your-hair-down free spirit uses coarse language the way some people use punctuation. There was a time when he drank to excess. A naturally verbose man and born raconteur, his preferred way of teaching is telling stories. Asides and anecdotes beget full-blown stories. He has a vast store of them.

The site of the Colony is a restored Victorian mansion across from another period house he and Pamela occupy. He’s prone to lecture in shorts, T-shirt and bare feet. While professing he keeps near him a file folder bulging with lecture materials. He fishes out writerly quotes, excerpts or tidbits to share, referencing Tennessee Williams, William Faulkner, Joseph Campbell. He relates how as a Northwestern University grad student he asked guest lecturer John Steinbeck what to do to be a great writer. The legend’s response: “Write!” Hunter’s appropriated a variation as his sign-off in letters and emails: “Write on!”

Colony sessions are largely unscripted improvisations. Hunter doesn’t need notes, he says, “because the structure is exactly the structure I do in a 10-week class.” At table readings he reads, aloud, students’ ideas or outlines and offers verbal notes, inviting group feedback. He proffers precise analysis that constitutes Lew’s Rules.

“Too little story.” “Too much story.” “What’s your story really about?” “Your imagination is the only restriction you have.” “Conflict, conflict, conflict.” “Story, story, story.” “Character, character, character.” “All comedy and all drama is based on the three-act structure.” “My paradigm is situation, consequences and conclusion.” “Don’t even think about writing down to the audience.”

His rapid-fire yet relaxed, let-it-all-hang-out approach is fun. But his sunny, cruise-ship-recreation-director manner is leavened by a semi-scholarly seriousness that makes clear this is no joke. There’s work to be done and no time to waste, well, maybe a little. Students pay thousands of dollars to attend, many traveling long distances to participate. Perks include drop-in visits by Hollywood friends like Kearney native Jon Bokenkamp, creator of The Blacklist.

Colonists aim to please their guru, whose laid-back Socratic Method has its charms. It suits this one-time King of Pitchers who bent the ear of producers and executives when trying to sell a story idea or script. Hunter knew how to play the game because he was on the other side as a producer-executive, listening to writers-directors pitch him.

How it all happened for Hunter is, well, a story. One he’s only too glad to share. It aptly falls into three-acts. But leave it to Hunter to digress.

Lew back in his salad days at the networks

Midwest roots

Raised in an “extraordinarily conservative” environment full of narrow-minded views – “I felt like I had a pretty sheltered life” – Hunter had a lot of growing up to do post-Guide Rock.

His classically trained mother exposed him to cultural things to round out the corn pone experience. For example she had him take dance and music lessons. His father was “known as the most loved and strongest man in Webster County” before a massive stroke left him paralyzed and unable to speak. “The first 12 years of my life I had him and then I lost him to a stroke and aphasia,” Hunter recalls.

As his father slipped further away, Hunter’s overbearing “hell on wheels” mother became the dominant presence in his life.

“She was the head of the Nebraska Republican Party, the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) and WCTU (Women’s Christian Temperance Union) in her lifetime. Someone asked me once, did you love your mother?” and I said, ‘Well, I think I loved her, but I didn’t much like her. I respected her. And my father, I adored.”

A bright boy who felt betrayed by life for taking away his father and bored with his surroundings, Hunter rebelled. He got caught doing petty vandalism. With his mother unable to handle him, a judge offered a choice – reform school or military school. Hunter chose the latter. A valuable takeaway from Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington Mo. came playing football. Back home he had no experience with African-Americans. He only heard disparaging, scornful things. Then one game while playing guard he went up against a black tackle whose extreme effort and high ability made a lie of what he was told.

“I got the shit beat out of me. That was a very good learning lesson. I deserved it.”

Hunter’s racial education continued at Nebraska Wesleyan University in Lincoln, where his roommate was a black student-athlete.

“Meeting him was clearly one of the best things. We palled around together. He took me down to the jazz cellars in Lincoln.”

Hunter became enough of a jazz devotee that at 17 he hitchhiked to Chicago to see Art Tatum at the Blue Note.

He studied theater at Wesleyan and he made his first foray into show biz working at Lincoln radio and TV stations.

“I became so caught up in the idea of being a professional that it spurred me to go to Chicago.”

Lew with Francis Ford Coppola

Rebel with a cause

Intent on studying broadcasting at Northwestern, he applied but was rejected. Not taking no for an answer he garnered letters of support from Neb. dignitaries and struck a bargain with school officials to enroll on a probational basis. If he got all As, he stayed. If he got even one B, he’d leave. He stayed and excelled, earning a master’s in 1956.

“That rebellious aspect of me is still part of me.”

He worked in Chicago radio as a disc jockey and producer. But he wanted out of the Midwest in order to try his hand in Hollywood. Everyone he consulted told him to quit what they considered a cockeyed dream and stay put. Instead, he followed his heart and went.

“I’ve been pretty much a guy that ‘no’ is just a word on the way to ‘yes.’ If I really want something bad enough, I keep on it.”

He did not head out alone. Though barely 20, he was already married. He and his young bride packed their Packard and hoped for the best.

He laid the groundwork for his eventual break into the big time by getting a second master’s at UCLA, this time studying film.

“I went to UCLA on a David Sarnoff Fellowship. I took a lot of pleasure and pride in that.”

He used that opportunity to get his foot in the door.

Future cinema legend Francis Ford Coppola was a classmate. Years after their graduate student days, Hunter had Coppola appear at the UCLA class he teaches to talk screenwriting with students.

At the Westwood campus Hunter indulged in some serious hero worship of his favorite instructor, Arthur Ripley.

“I had very specific mentoring with Arthur Ripley. I just adored him. He was the most charismatic, interesting man.”

Hunter says Ripley’s sarcastic humor was reflected in a famous one-liner attributed to him. When stoic former U.S. President Calvin Coolidge died Ripley was said to have cracked, “How could they tell?”

A veteran from Hollywood’s early sound era, Ripley helped create the miserly, misanthropic W.C. Fields character the comedian parlayed to great success. Ripley worked for cinema giants Mack Sennett, Frank Capra and Irving Thalberg.

“I admired Arthur Ripley and all these wonderful stories he told when he worked at MGM for Irving Thalberg. He told stories about running around with Thomas Wolfe. I was like a sponge soaking up all that stuff. I have more show business stories because I loved the business and the people and the craziness of it all.”

Lew and Pamela

The start of it all

Hunter got on as a page at NBC and then worked in the mailroom, where he rose up the ranks to music licensing and promotion.

“I could see there was a ladder I could climb at NBC.”

He later worked in promotion at ABC and served stints at CBS and Disney, among other entertainment conglomerates, before eventually transforming himself into a producer-writer. He later rejoined NBC.

Then-NBC and MTM president Grant Tinker gave Hunter some sage advice about the vagaries of Hollywood when Hunter was torn between staying at NBC or taking an offer at ABC.

“He said, “For your benefit you need to know that in this business you’re not rewarded for loyalty. Quite to the contrary, we’ll probably be more interested in you if you go over to ABC, and so I did.”

And just as Tinker predicted, after making the move Hunter found himself more in demand than ever.

“In this business, if they want you, over hot coals and razor blades they will come get you. But if they don’t want you, nothing. I mean you’re either eating high on the hog or on the hoof of the hog.

“For one brief shining moment,” as the song goes, Hunter officed at four different studios, including Paramount.

He got schooled by (Aaron Spelling) and had run-ins with (Irwin Allen) some big-name producers.

Seeing so many different sides of the business, he learned the ins and ours of how shows and movies get developed, packaged, marketed.

“I was in promotions doing trailers for Bonanza, Dick Powell Theatre, Dinah Shore Chevy Show and so forth. I was around it all the time. A sound engineer and I went around to stars’ homes with a reel to reel tape machine to record them reading copy promoting their shows. Once, we went to the home of my idol, Fred Astaire. As he was reading into a microphone the copy I’d written for him I glanced through another room’s open doorway and I saw a pool table inside. When he was done I said, ‘Do you play pool, Fred?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, do you play pool?’ I said, Well, a little, and he said, ‘Oh-oh, I’m toast, c’mon, let’s go.’ I played a game of pool with Fred Astaire and he won and I let him win. I could not dream of beating my idol.

“I have lots of stories about John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Cary Grant. It just goes on and on.”

Perhaps the star he got closest to was Judy Garland.

“She and I were very close on an emotional level. We had such a wonderful relationship. We never went to bed with each other but we sure flirted with each other a lot. I’m still in sorrow over what happened to her over the last few years of her life and how she died.”

He enjoyed getting to know the real personalities behind the personas.

The writer’s way

Doing promos was fine but he felt pulled to go where the action is – programming. He took endless meetings with writers, producers, agents. He gleaned what he could from those around him.

“I had doors open for me all the time I think because of my Neb. decency. I was just eager to absorb everything I could and I learned so much in those story conferences, going to dailies, watching rough cuts and observing artists working on the backlot.”

He was at ABC and then Disney (as a story executive) when the urge or, more accurately, the obligation to be a writer got the better of him.

“I had been for like four or five years telling writers how to write and never having made a living as a writer myself. It bothered me a lot because I really didn’t think I had the cachet. I mean, it’s very, very alarming to give notes to Paddy Chayefsky, who I idolized, or Neil Simon. I was having lunch with Ray Bradbury at the Disney commissary and I said, ‘I’ve read 2.000 scripts in the last two years and 90 percent of them are shit. I think I can be in the top 10 percent. He encouraged me to read Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style and Dorthea Brande’s Becoming a Writer.

“I came home and told my then-wife I’ve gotten to the point where I want to try to be a writer myself. And she said fine.”

It was a leap of faith as the couple had young kids and a mortgage.

Hunter left his job to scratch this itch. He made a pact that if he didn’t make it in a year he’d find a job. Fifty-one weeks later none of the screenplays he wrote had sold. Tapped out and with a family to support, he took a job as a body sitter at Forest Lawn cemetery. The ghoulish work entails sitting up with corpses and laying them down if they rise up from rigor mortis. He’d done it at an uncle’s funeral home in Guide Rock and again to pay his way through college.

The day before he was to start Aaron Spelling called saying he wanted to buy Hunter’s script for what became If Tomorrow Comes. If it hadn’t sold at least Hunter knew he’d tried.

If Tomorrow Comes is the story of an ill-fated romance between a Caucasian girl and Japanese-American boy in the days before and after Pearl Harbor. The couple get separated when he and his family are ostracized after Japan’s attack on the U.S. and eventually imprisoned in an internment camp.

Even though Hunter grew up during the period when Japanese-Americans were interned he was, like the general public, oblivious to what happened. He only thought about the internment as the premise for a script when a relative recalled this infamy in less than sympathetic terms. That propelled Hunter to research the subject. He was appalled to discover that innocent Japanese-Americans were summarily stripped of property, businesses, livelihoods. Their kids taken out of schools, their lives disrupted. They were treated as criminals and traitors. All without due process. He was dismayed to find they were interned in camps surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards.

“I was shocked we incarcerated more than 120,000 citizens.”

He was shocked this injustice was not mentioned in textbooks. He was offended that many folks dimssed the incident as just part of the price of war. That it was merely a regrettable inconvenience when in fact it was a traumatic severing and breach of trust and civil rights.

In writing his script he found an emotional hook everyone could relate to by imagining a star-crossed Romeo and Juliet romance torn asunder by those harsh, unforgiving events. Patty Duke and Frank Michael Liu starred as the lovers whose lives are interrupted by history.

Anne Baxter, James Whitmore, Pat Hingle and Mako co-starred.

He considers the resulting 1971 movie made from his script among “the stuff that I’ve done that I’m most pleased with,” adding, “That was the thing that got me going. We got a 39 share. My phone was ringing off the hook. Then came another project and another one.”

Hunter resumed working for NBC and various studios in the 1970s and 1980s. As a general program executive at NBC he helped bring to the small screen two movies touching on social=political-moral issues in The Execution of Private Slovak and The Red Badge of Courage (both 1974). Later, as director of program development, he oversaw some major mini-series, including Centennial.

His next venture as a writer confronting social issues was Fallen Angel (1981), in which he tackled pedophilia long before the Catholic Church scandal broke. The idea for taking on the sensitive topic seemingly popped in his head during a meeting.

“I was pitching to Columbia executive Christine Foster when the phone rang. We heard, ‘This is Peter Frankovich here.’ He was an executive at CBS. Christine said, ‘I’ve got Lew Hunter.’ We all knew each other. I said, ‘Can I show you something, Peter?’ He asked, ‘You got anything hot?’ And I found myself saying, ‘Child pornography.’ It just came to me. And then, boom, he said, ‘You’ve got a deal.'”

Only Hunter didn’t have a story, much less a script. He was due to meet Frankovich the next week.

“I said to m self, ‘Oh, shit, I’ve gotta get a story together.” I went down to what was called the Abused Children’s Unit at LAPD. They told me everything they could tell me. I was in constant horror. They had me go down to the hall of records and look at the pedophile records.”

He learned how perpetrators groom their victims. In his script the perp is a photographer (Richard Masur) who befriends a fatherless girl (Dana Hill) and convinces her to pose nude. It bothered Hunter that kids could be manipulated or coerced to appear nude and perform sexual acts and that L.A. was the porn capital of the world.

It was only after Fallen Angel aired he remembered he had a childhood encounter with a pedophile.

“My mother thought she’d make a little bit of money by renting out a room to a Superior Knights semi-pro baseball player. He was a large man and he roomed right next to my room. One day he suggested we go out to the cornfield for a beer. We drove out there and parked. He said, ‘You’ve been really naughty to your mother.’ Of course, I had. I was a little ass-wise, That’s how I ended up at military academy. And then he put his hand on my thigh and said, ‘You know, you deserve to be spanked.’ I didn’t have the slightest idea what was going on but I knew it was bad, so I disengaged myself, leaped out of the car and ran through the cornfield back home. I didn’t say anything to my mother. That man was back in his room that night and I spent every night for the next month with a .22 rifle next to me when I went to bed. I was going to shoot him if he came in and tried something.”

Hunter says the man attempted to molest some of his buddies, too. While Hunter was away at military school he heard the authorities finally caught the predator. Several boys filed complaints against him.

Fallen Angel scored a record 43 share.

Too close for comfort

A personal tragedy informed Hunter’s next controversial and much viewed project, Desperate Lives (1982).

“My best friend at the time said we should so a story together about our boys. Our sons were both deep into drugs. One of the people I talked to in researching this was my son, who said, ‘I can get drugs at my high school quicker than I can get lunch at the cafeteria.'”

Hunter made a decision to give the protagonist played by Doug McKeon the same name as his son, Scott, who didn’t appreciate it.

“it was a stupid thing because it really estranged us, I’m sure for the rest of our lives. He basically doesn’t talk to me, just superficially. That was a very negative thing in my life and something I deeply regret.”

About doing projects that meant something, even at a cost, he says, “I just started poking round through life and coming up with things that really energized me. That was the key for me.”

Fast forward a couple decades, to soon after Lew and Pamela moved to Superior, when the scourge of methamphetamine hit hard.

Concerned by its devastating effects on residents’ lives, he and Pamela formed a nonprofit to raise awareness of the dangers and of helping resources available.

“This bloody meth problem is a terrible problem,” he says. “It’s a rural holocaust.”

He got retired Nebraska football coach Tom Osborne and other public figures, along with law enforcement officials, to appear at a town hall meeting. The Hunters mentored in Osborne’s Teammates program.

Lew and Tom Osborne, ©The Digg Site Productions, photographer Christine Young

Lew says. “Boy, we really had a roll going. We certainly woke the town up to the fact we have a very serious problem and the reality is the problem still exists. I don’t think it’s going to subside.”

The nonprofit he launched has since been absorbed into a state Health and Human Services program.

Superior Express publisher Bill Blauvelt says the Hunters are a presence in that tiny community.

“Lew and Pam have been active on many fronts. When they take on a project it is a joint effort. You don’t get one with out the other. They have financially supported many community activities and encouraged programs. Last summer they brought in a painter to work on their homes and then kept finding work so that he and his crew stayed the entire summer. They provided a house for the men to stay in.

“Their homes are always open. If we have important people coming to town and they need a place to stay, you can count on the Hunters to provide lodging. The colony program has brought lots of visitors to town, many of whom spend freely while here. And the colony has brought me friends. Often I have been invited to attend their get acquainted picnics and late night parties.”

Finding his niche as teacher and author

After If Tomorrow Comes and before Fallen Angel. Hunter began teaching at UCLA in 1979. From the start, he’s taught grad students.

“I love that. Undergraduates, they know too much – they haven’t been knocked around as the graduate students.”

He says teaching screenwriting while penning scripts himself proved fruitful.

“It was great. I’d be working on a script and I’d realize. ‘I can’t do this,” because I just told students they’re not supposed to have two people in a room agree with each other – one of my dictums.”

His classes became popular, especially 434. Each student starts with a synopsis and they’re guided step by step to create an outline, story points, and by the end of the class they have a first draft screenplay.

“Then somebody said, Why don’t you put your class on paper?’ I said, ‘That’s a good idea.'”

He says. “Other screenwriting books are ABOUT screenwriting but they don’t tell you HOW TO write a screenplay, they don’t give you the caveats you get on a professional level. Not only do I tell you how to write a screenplay I tell you how 80 to 90 percent of professionals write a screenplay.”

As more than one person in Once in a Lew Moon states, Hunter demystified the screenwriting process and made it accessible to everyone. Like the evangelist he is for screenwriting, he even spread the gospel doing workshops around the world in his aw-shucks style.

“From me, you don’t get this academic bullshit you get from other people who have only learned from a book or they’re failed screenwriters. They give misinformation. I would not have gone into professing had I not been successful. If you go to IMDB you’ll see it’s a pretty long list of stuff I’ve done – probably over a hundred hours of actually writing stuff and producing it. I’m really quite proud of that.”

He’s also proud he and his colleagues helped “professionalize” the screenwriting program at UCLA.

“We have more professionals professing.”

Since the program produces many grads who work in the industry, there’s a deep talent pool of writers who come back to teach. Their experience gives students is a taste for how things really work.

“We try to recreate what they’re going to face when they go out into the professional world with the meetings and note sessions before they actually write the screenplay and polish the screenplay.”

Soon into his teaching career he and a group of his students formed the Writers Block, a monthly social for writers. Newly divorced at the time, he offered to host it at his three-bedroom Burbank home.

This open house started small but grew like wildfire.

“The first one had about 20-25 people, then we got 40 and then 40 became 70 and 70 became…until eventually we got hundreds. People would come in and out over the evening. Professional writers dropped by because they liked the atmosphere. We socialized and bull-shitted.

I’ve always felt we writers socialize but we don’t party – it’s too frivolous. It was a wonderful thing.”

In the documentary, former students express gratitude for Hunter creating “a community” of writers. When Pamela entered Lew’s life she became part of the scene. Once Lew and Pamela adopt you, you not only have the keys to their heart but to their house, too.

The last Writers Block in ’99 was held off-site to accommodate the 1,000-plus attendees.

“We closed it down when we moved back to Nebraska,” he says. “Going back to the roots,” he calls that full circle relocation.

He and Pamela will be buried in the Guide Rock cemetery.

“We’ll be stacked,” he says. “The one that goes first will be on the bottom and the one after that will be on top. That’ll raise some gossip.”

Lew and Lonnie Senstock

Once in a Lew Moon

The documentary about Lew is a passion project for director Lonnie Senstock, who regards the Hunters as surrogate parents.

“Well, he wanted to do something about me,” Lew recalls. “He came to the colony and shot a lot of footage. That was a decade ago. He’s been working on this sucker for 10 years. Very shortly on into the relationship he said, ‘I’d like you and Pamela to be my parents.’ His parents died within a ear of each other. We said sure and so he calls us papa and mama and we’re cool with that. He’s a really nice man.”

Senstock says the film could have gone a different direction when he and Lew experienced some difficulties in their lives. But, he adds, “I found myself celebrating something beautiful instead of something dark. I didn’t realize it was going to be that way until Lew and I talked about the celebration of writing. We realized it was bigger than him. We really wanted it to celebrate that life that so seldom is given kudos.”

Hunter appreciates that focus, “Everybody in it is talking about screenwriting. I like that.” He likes, too, how it overturns the idea that somehow actors and directors just make up movies as they go along.

“There are men and women who write these things.”

Meanwhile, this old lion of cinema, now battling illness, is readying his next book, Lew Hunter’s Naked Screewriting: 25 Academy Award-winning Screenwriters Bare their Art, Craft, Soul and Secrets.

Whatever’s happening with him, he still makes time for past-present students. He’s frequently sought out to consult on scripts and projects. He makes himself available 24-7.

“I’ve always thought being accessible was the right thing to do.”

Besides, he says, “I identify so much with people who are dreamers.”

Once in a Lew Moon screens Sunday, March 12 at 3:45 p.m. at Marcus Village Pointe Cinema in Omaha.

Follow Lew’s adventures at http://www.lewhunter.com.

Making community and conversation where you find it: Stuart Chittenden’s quest for connection now an exhibit

When Stuart Chittenden couldn’t meaningfully connect with others in his adopted hometown of Omaha he and his wife Amy began hosting conversation salons in their Midtown home. That led to Chittenden starting a business, Squishtalks. And that led him to embark on a project, 830 Nebraska, that saw him travel the state to explore making community and conversation. His photos and audio recordings of people he met and spoke with are now an exhibit. I profiled Stuart and his project last fall for Metro Magazine and you can find that piece on this blog, leoadambiga.com. Here is a new feature I’ve written on Stuart and the 830 project. The story appears in the February 2016 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Making community and conversation where you find it

Stuart Chittenden’s quest for connection now an exhibit

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the February 2016 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Last August Stuart Chittenden traversed Neb. to test drive the idea that interpersonal communication is intrinsic to building community.

He called the project “A Couple of 830 Mile Long Conversations.” With support from Humanities Nebraska, the Nebraska Cultural Endowment, the Omaha Creative Institute, plus Indie GoGo funding, he set out to meet Nebraskans where they are. He communed in bars, bakeries, cafes, outside storefronts, at campsites, farms, ranches, fairgrounds.

The Omaha resident intentionally went to the great wide open spaces that make up Nebraska to find the connective thread of community running through cities and towns, the Sand Hills, the Panhandle, the Bohemian Alps and the Platte River Valley.

Wherever he pitched his talking tent, people happened by and conversation ensued. He was both facilitator and participant. The photographs and audio recordings he made of these meet-ups, including the stories people told about their lives and communities, plus the trials, joys and lessons bound up in them, comprise a new interactive exhibition at the W. Dale Clark Library.

Simply titled 830 Nebraska, the exhibit is curated by Alex Priest.

It features 20 8” x10” photographs of the people and places documented. Viewers can also listen to audio excerpts from the conversations, thereby putting voices and words to faces.

Hitting the highway in search of something has a nomadic romance about it. But this was no existential On the Road personal freedom ride fueled by sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll. No, this was a buttoned-down ex-pat Brit in an RV following a pre-determined path, albeit open to some detours along the way. Some of the folks he documented were encountered in the natural flow things and others pre-selected.

That’s not to say Chittenden, whose day job is Chief Curiosity Officer at Omaha branding company David Day Associates, doesn’t harbor a bohemian soul. In terms of exploring conversation, he’s both creative entrepreneur and mad amateur social scientist. He’s fascinated by the power of dialogue. So much so he and his wife Amy hosted conversation salons in their mid-town home. The salons begat a business, Squishtalks, that sees him package conversation programs for clients. Through guided talk sessions he helps organizations navigate public and community concerns.

The exhibit culled from his 830 Nebraska experiment follows a series of statewide talks he’s given in which he’s shared his takeaways from the project, The Reader recently caught up with Chittenden to get a fresh take on what he found out there, what he brought back and how it’s all part of his own quixotic journey of self-discovery.

This serial daydreamer’s youth in Great Britain was preoccupied by flights of fancy, his reveries often revolving around the very American archetypes he tapped decades later.

The pull of the American West once led him to live in Colorado. Though he’s resided in Neb. several years, living in Omaha made him feel isolated from much of the state. His travels for the project confirmed the divide between Omaha-Lincoln and the greater rural reaches. If his urban origins and British accent put off folks, he didn’t sense it. Indeed, he found he received the same good vibrations he put out. Call it the law of attraction

“If you approach any environment with a sincere openness and willingness to appreciate someone else’s voice, if you’re open to them, then it is door opening,” he says.

In that same communal spirit he found no doors closed, but rather heaping doses of hospitality and conviviality, though some folks politely declined going on the record. Whether shooting the bull with the boys at the bakery or chewing the fat with the guys at the barbershop, he was welcomed as a friend, not a stranger, and people expressed appreciation for his interest and invitation to just talk.

“That affirmation has buttressed my belief that conversation is not only something of benefit to communities and individuals but that this is my calling.”

By intent and intuition, he got people to say what’s on their hearts and minds in regards to what makes community.

“The more people talked the more other elements started to come out that suggested to me that community is a paradox. From the outside, if you try to create it, that is a very difficult thing to do. Community instead is a deliberate individual choice to behave and do things in ways that invest in something that is not directly related to you.”

Chittenden found a mix of rural communities, ranging from vibrant cultural enclaves such as Dannebrog to robust Western outposts such as Chadron, and bedraggled hamlets in between.

“I had this expectation that rural life would be decimated and somewhat tired and there are those towns that do appear to be in a position of uncertainty,” he says. “You can feel they’re in stasis. They don’t know what circumstances are going to do to them and so they feel in flux, tired a little bit.

“Then there are those other towns that aren’t allowing circumstances to dictate what happens, they are looking at the available resources they have – people or place or history or whatever – and managing those things in ways that make them sustainable.”

He says residents in remote places like Scottsbluff or Valentine “don’t have any other choice but to fix things or make things – you do it for yourself or it doesn’t get done,” adding, “Several people demonstrated this zest for self-determination, for sustaining themselves and coming together as they need to as people. They credit that spirit to the legacy of the pioneers.”

For Chittenden, there are larger implications for what conversation and community can mean to certain underserved and underrepresented populations. In Wayne, Neb., for example, he spoke with an openly gay couple who run a business in town. They told Chittenden they find more acceptance there than they do among young professionals in Omaha, where they get the feeling they’re not taken seriously because of the stigma that paints rural denizens as unsophisticated. More pernicious yet, Chittenden says, are the silos erected by different groups to talk over each other, not to each other.

“The more I look around me in our community in Omaha and in communities across the nation I see increasing division and inequality and I am morally outraged by that situation. As offended as I am by all the various types of inequality I see, wrapped up in very casual stereotypes and bigotry to those people on the other side of the fence, I’ve begun to see that my contribution to the better health of our society is just to increase understanding of the other. And the way to do that is to engage people in conversation.

“You don’t have to like them, you don’t have to agree with them but if you can do anything to increase rapport and understanding, you’ve already taken very bold steps to a more cohesive society.”

He says as he’s come to accept his role as conversation starter or convener, he’s reminded of an old saying he once heard that goes, “the point about conversation is that it has no point.” Thus, he’ll tell you, the real fruits of an exchange only come when the parties forget ego or agenda and genuinely listen to each other. In a world starved for rich authentic content, it doesn’t get any richer or truer than that.

The exhibit, which runs through February 29, is in the Michael Phipps Gallery on the first floor of the downtown library, 215 South 15th Street. The show is open during normal library hours. For more details, visit http://omahalibrary.org/w-dale-clark-library or call 402-444-4800.

Follow this wayfaring conversationalist at https://www.facebook.com/stuart.chittenden.

Lourdes Gouveia: Leaving a legacy but keeping a presence

One of the smartest and kindest people I know, Lourdes Gouveia, has stepped down from directing the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies of the Great Plains or OLLAS, a program she helped found at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. A sociologist by training and practice, she and her program have helped the university, policymakers and other stakeholders in the state better understand the dynamics of the ever growing and more fluid Latino immigrant and Latin American population. OLLAS has become a go-to resource for those wanting a handle on what’s happening with that population. She is very passionate about what she’s built, the strong foundation laid down for its continued success and the continuing research she’s doing. Though no longer the director, she’s still very much engaged in the work of OLLAS and related fields of interests. She’s still very much a part of the UNO scene.

Lourdes Gouveia: Leaving a legacy but keeping a presence

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in El Perico

When sociology professor and researcher Lourdes Gouveia joined the University of Nebraska at Omaha faculty in 1989 it coincided with the giant Latino immigration wave then impacting rural and urban communities.

Little did she know then she would found the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies of the Great Plains or OLLAS in 2003. She recently stepped down as director of that prestigious center she’s closely identified with.

The idea for OLLAS emerged after her field work in Lexington, Neb. documenting challenges and opportunities posed by the influx of new arrivals on communities that hadn’t received immigrants in a century. She focused on the labor trend of Latinos recruited into meatpacking. While doing a post-doctorate fellowship at Michigan State University she came to see the global implications of mobile populations.

“It really did become a transformative experience,” recalls the Venezuela native and University of Kansas graduate. “It gave me a whole new level of understanding of issues I had been working on. It opened opportunities I had no idea we’re going to be so influential and consequential in my life. These were colleagues as motivated as I was to try to understand this tectonic and dramatic shift going on of increased immigration from Latin America accompanied with an economic recession in the United States.

“I learned a tremendous amount. It just opened a lens that gave me confidence to understand this shift in a larger context.”

When Gouveia returned from her post doc she accepted an invitation to head what was just a minor in Latino Studies at UNO.

“I said yes but with a condition we explore something larger. Many of us were beginning to realize the minor was just not enough of a space to understand, to educate our students, to work with the community on issues of this magnitude.”

She led a committee that conceived and launched OLLAS and along with it a major in Latin American Studies.

“OLLAS was built upon a very clear vision that Neb. and Omaha in particular was seeing profound changes in the makeup of the Latino immigrant and Latino American population. Neither the university nor the community, let alone policymakers. were sufficiently prepared to understand the significance of those changes and their long-term consequences or respond in any informed, data-driven, rationale way. That message resonated with people on the ground and at the top.”

Lourdes Gouveia (far right) is the Director of OLLAS at UNO. (Photo Courtesy UNO)

Significant seed money for making OLLAS a reality came from a $1 million U.S. Department of Education grant that then-Sen. Chuck Hagel helped secure.

From the start, Gouveia says OLLAS has existed as a hybrid, interdisciplinary center that not only teaches but conducts research and generates content-rich reports.

“Community agencies, policymakers, students and others tell us they find enormous value in those research reports and fact sheets we produce. That is a mainstay of what we do. It’s done with a lot of difficulty because they require enormous work, expert talent and rigor and we don’t always have the resources at hand. Yet we have maintained that and hope to expand that.”

She says OLLAS is unlike anything else at UNO.

“We’re an academic program but we’re also a community project. So we’re constantly engaging, partnering, discussing, conversing with community organizations, even government representatives from Mexico and Central America, in projects we think enhance that understanding of these demographic changes. We’re also looking at the social-economic conditions of the Latino population and what it has to do with U.S. immigration or U.S. involvement in Latin America.”

OLLAS also plays an advocacy role.

“We use our voices in public, whether writing op-ed pieces or holding meetings and conferences with political leaders or elected officials. We use our research to make our voices heard and to inform whatever issues policymakers may be debating, such as the refugee crisis.”

Gouveia says the way OLLAS is structured “allows us to be very malleable, more like a think tank.” adding, “We define ourselves as perennial pioneers always trying to anticipate the questions that need answers or the interests emerging we can fulfill. It’s extremely exhausting because we’re constantly inventing and innovating but it’s extremely rewarding. We’re about to put out a report, for example, on the changes of the Latino population across the city. Why? Because we are observing Latinos are not just living in South Omaha but are spread across the city. As we detect trends like this on the ground we try to anticipate and answer questions to give people the tools to use the information in their work. That guarantees we’re always going to be relevant to all these constituencies.”

OLLAS faculty and staff

OLLAS has grown in facilities and staff, including a project coordinator, a community engagement coordinator and research associates, and in currency. Gouveia says, “I’m very satisfied we did it right. We thoughtfully arrived correctly at the decision we just couldn’t be a regular department offering courses and graduating students but we also had to produce knowledge. Our reports are a good vehicle for putting out information in a timely manner about a very dynamic population and set of population changes.”

She says OLLAS could only have happened with the help of many colleagues, including Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado and Theresa Barron-McKeagney, “who shared enthusiastically in the mission we were forging.” She say OLLAS has also received broad university support and community philanthropic support.

“There was resistance, too,” she adds. “It’s a very creative space that breaks with all conventions. Like immigrants we create fear that somehow we’re shaking the conventional wisdom. But I think our success has converted many who were initially skeptical. I think we’ve pioneered models that others have come to observe and learn from.”

One concern she has is that as Latino students in the program have increased UNO’s not kept apace its hiring of Latino faculty.

A national search is underway for her successor.

“I feel very good about stepping out at this time. It surprised a lot of people. As a founding director you cannot stay there forever. Once you have helped institutionalize the organization then it’s time to bring in the next generation of leaders with fresh visions and ideas.”

Besides, there’s research she’s dying to get to. And it’s not like this professor emeritus is going away. She confirms she’ll remain “involved with OLLAS, but in a different way.”

Visit http://www.unomaha.edu/ollas/.

How wayfarer Stuart Chittenden’s Nebraska odyssey explored community through conversation

This past summer Stuart Chittenden formulated an equally brilliant and lovely idea to explore the power of conversation for making community when he struck out on the road for a meandering journey of small talk into the very heart of his adopted state, Nebraska. Traveling by RV, the ex-pat Brit stopped in a series of towns and cities to sit down and talk with people about what community means to them, but mainly he listened to their stories. And he recorded those tales. On his weeks long adventure he met and had conversations with a cross-section of this state’s salt-of-the-earth folks and he came away with a new appreciation for this place and for people’s diverse lifestyles in it. Read my Journeys piece here about Chittenden and his project for Metro Magazine or link to it at http://www.spiritofomaha.com/Metro-Magazine/The-Magazine/. Or get your copy of the print edition by subscribing at https://www.spiritofomaha.com/Metro-Magazine/Subscribe/

IMAGES FROM STUART CHITTENDEN’S WEBSITE © http://830nebraska.com/ unless otherwise noted.

From the Metro Magazine print edition

How a wayfarer’s Nebraska odyssey explored community through conversation

Stuart Chittenden’s magnificent obsession led to an epic road trip…a summer sojourn across the state centered around community and conversation

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the Nov-Dec-Jan issue of Metro Magazine (http://www.spiritofomaha.com/Metro-Magazine/The-Magazine/)

Leave it to an ex-pat Brit to travel Neb. in search of what makes community in this Midwestern place. He did it the old-fashioned way, too, by engaging in dozens of face-to-face conversations with residents across the width and breadth of the state over a month-long journey.

Traveling alone in a rented RV, Stuart Chittenden, 46, stopped in urban and rural settings, on main streets and side streets, in libraries, coffee shops, barber shops, bars, town squares and private homes to chew the fat with folks. He shared the fruits of his travels and conversations across social media via his project website, Instagram posts and Twitter tweets. He also did radio dispatches for KIOS 91.5 FM.

Chittenden made the August 10-September 5 trip for his project A Couple of 830 Mile Conversations. Nebraska is about 430 miles from east to west but his purposely meandering, circuitous route nearly doubled that distance each way.

He will be making public presentations about the project across the state this fall. Beyond that, he’s considering what to do with the 100 hours of recorded interviews he collected.

The project received an $8,000 Humanities Nebraska grant matched by monies from an online Indie Go-Go Crowd Funding campaign.

American archetypes

The experience fulfilled a lifelong fascination he’s cultivated with American archetypes. He’s long wanted to see for himself the places and characters who’ve fired his “fertile imagination” about pioneers, cowboys, ranchers, rugged individualists. indigenous cultures and immense open spaces. The project gave him an excuse to “follow the archetypal American adventure to go west.”

Not surprisingly, the experience made quite an impression.

“My reactions to the state are that it’s remarkably diverse, very historic. There are areas of natural beauty really quite remarkable. Physically the state is an intriguing. lovely and delightful place to go and explore. In terms of the culture. I was surprised by how vibrantly pioneering the west of the state feels. In Scottsbluff several people demonstrated this zest for self-determination, for sustaining themselves and coming together as they need to. Billy Estes and others there credit that spirit to the legacy of the pioneers.

“In a more remote community like Valentine it also means you don’t have any other choice but to fix things or make things. You do it for yourself or it doesn’t get done. To see that spirit is to really appreciate it. I thought most rural communities would seem somewhat tired and there are those towns that do appear to be in a position of uncertainty – they don’t know what circumstances are going to do to them and so they feel in flux. But then there are those other towns that aren’t allowing circumstances to dictate what happens. They are looking at the available resources they have and managing those things in ways that make them sustainable.”

Individuals made their mark, too.

“Owen Timothy Hake in St. Paul touched on the courage needed in the choice to sit and talk with a stranger.”

R. Mark Swanson in Valentine recounted how conversation was therapeutic for him in the wake of his father’s suicide and losing his 16-year-old son. He told Chittenden that stories are “a form of freedom.”

The project was also an extension of work Chittenden’s been doing with conversation as a mediation and relationship tool. He wanted as well to assess the facility of this human communication medium as a means for finding consensus around the idea of community.

He says the project was “founded in my belief conversation is a way we connect better and form community.” It was also his opportunity to discover how people across the state talk about community. “I was very aware of the supposed divides between rural and urban. Also I wanted to put to the test my beliefs about conversation to see if it really has that kind of power or potency.”

Tom Schroeder in Dannebrog told Chittenden how community requires genuine personal, emotional investment. Community often came up in the sense of the safety it offers. Others spoke about community in terms of the appreciation they have for their town.

Though Chittenden’s lived in Omaha many years – his wife Amy is a native – the journey was his first real foray across the state with the intention of finding the heart of things and closely observing and recording them. That’s why he opted to follow the road less traveled – taking highways and byways rather than Interstate 80.

Making sense of it all

Still fresh from meeting people wherever he found them, he’s been weighing what these encounters and dialogues reveal. He says it was only at the end of the trip he began “to formulate some ideas around what community means to people.”

“Some of these incipient thoughts around community are that it’s paradoxical,” he says. “I heard a lot of people talk about things like it’s trusting, it’s supporting each other and it’s feeling safe and not locking your doors, et cetera, and that’s all true. But it didn’t really ever quite get to the heart of the matter. And the more people talked the more other elements started to come out that suggested to me community is a paradox. If you try to create it by saying, ‘I’m going to make my neighborhood a good community,’ it’s a very difficult thing to do.

Community instead is a deliberate individual choice to behave and do things in ways that invest in something not directly related to you.

“It’s a very individual action and it’s a very deliberate choice. The people that are active and altruistic and do something that isn’t selfish – the effect of that is community.”

Not his first rodeo

All of this is an extension of a path he’s been on to use conversation as a community building instrument. It started when he first came to Omaha to work as a business development director for David Day Associates, a branding agency he still works at today.

“Being new in town required me to network. I found there to be an arid landscape for engagement of a depth beyond one inch and that was not satisfying to me. I didn’t want to be in a new community and establish networking connections that had no merit other than just superficial Neb. nice. So that was one provocation that led me to desire more meaningful conversations with people.

“The second track is that the more I look around me in Omaha and in communities across the nation I see increasing division and inequality – wrapped up in very casual stereotypes and bigotry to people on the other side of the fence – and I am morally outraged by that situation.

I’ve begun to see that my contribution to the better health of our society is just to increase understanding of The Other and the way to do that is to engage people in conversation. You don’t have to like them, you don’t have to agree with them, but if you can do anything to increase rapport and understanding, you’ve already taken very bold steps to a more cohesive society.”

He felt strongly enough about these things that he and Amy hosted a series of by-invitation-only conversation salon evenings in their mid-town home beginning in 2010.

“People would come together and talk about issues without an agenda and move beyond the superficial,” he says.

That morphed into salons led by siimilarly-minded creatives. But after two-plus years it got to be more than the couple could handle at home. At Amy’s insistence, he looked long and hard at how much he wanted to continue doing it and the need to take the model out into the world.

“It was something incredibly meaningful and fulfilling for me and therefore I wanted to see if it had merit beyond the personal in our home,” Chittenden says.

He then formed Squishtalks, a for-profit platform for conversation-based interventions and experiences he develops and facilitates for organizations, corporations and communities.

The 830 Nebraska project amplified everything Squishtalks represents and reinforced what he feels his purpose in life is shaping up to be.

“Conversation is not only something of benefit to communities and to individuals but what I’m learning is that it’s my calling.”

“My reactions to the state are that it’s remarkably diverse, very historic. There are areas of natural beauty really quite remarkable. Physically the state is an intriguing. lovely and delightful place to go and explore.”

“I’ve begun to see that my contribution to the better health of our society is just to increase understanding of The Other and the way to do that is to engage people in conversation. You don’t have to like them, you don’t have to agree with them, but if you can do anything to increase rapport and understanding, you’ve already taken very bold steps to a more cohesive society.”

“Conversation is not only something of benefit to communities and to individuals but what I’m learning is that it’s my calling.”

“The list of people that will stay with me from this project and whom I intend to maintain connection is quite long.”

To be or not to be

Calling or not, Chittenden felt the project pulling him in different directions.

“I wrestled with should I heavily promote the project in the places I was going to or not promote things at all but literally just turn up somewhere totally unannounced. The difficulty with over-promotion is that what happens is you run the risk of getting a queue of people who want to talk at you and you miss other people. People self-select for reasons that perhaps aren’t the reasons you want them to sit down and talk to you. At the other end, if you just roll in and don’t tell anybody – I could be sitting around places and having no conversations with anybody.”

He resolved this dilemma by playing it down the middle “so things weren’t contrived but I’d also have people to talk to,” adding, “That was an interesting dance and I don’t know whether it was right or wrong, one could never really know. But I feel as if I struck a balance between reaching out to a few interesting people in advance, reaching out to library directors to work with them, and then just showing up.

“Actually getting on the road, the experience was very much working out – where do people convene, where does anybody convene in any environment for any purpose, where do people go to protest, to celebrate, to feel a safe environment for provocative conversation?

All of these things were occurring to me.”

Early into the experience, he says, “I realized I had to adjust my initial formal plan of just setting up in a public space to put myself into places where people did convene and often that meant a bar, more likely a coffee shop or the donut place and maybe stopping at the gas station to ask where the old-timers were. It was that balance between allowing serendipity to reign and if no one came and sat with me for two hours, that’s what happened, that’s how that was meant to be.”

At each stop, he says, “…maybe 95 percent of people would acknowledge me warmly or would respond to my greeting warmly. Maybe 2 in 10 would ask what’s going on and then 1 in 10 would sit down. And the reasons why the other people didn’t will remain unknown and I think that’s totally fine.”

Wherever he set up with his sign reading “Hello! Please sit and chat with me” he surrendered himself to take whomever fate offered in this intersection of outsider-meets-local. He was not disappointed.

People he won’t soon forget

“The list of people that will stay with me from this project and whom I intend to maintain connection is quite long.”

Two unforgettable characters were Lukas Rix and Mark Kanitz in Wayne.