Archive

Life Itself XVI: Social justice, civil rights, human services, human rights, community development stories

Life Itself XVI:

Social justice, civil rights, human services, human rights, community development stories

Unequal Justice: Juvenile detention numbers are down, but bias persists

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/09/unequal-justice-…ut-bias-persists

To vote or not to vote

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/06/01/to-vote-or-not-to-vote/

North Omaha rupture at center of PlayFest drama

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/04/30/north-omaha-rupt…f-playfest-drama/

Her mother’s daughter: Charlene Butts Ligon carries on civil rights legacy of her late mother Evelyn Thomas Butts

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/28/her-mothers-daug…lyn-thomas-butts/

Brenda Council: A public servant’s life

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/26/brenda-council-a…ic-servants-life

The Urban League movement lives strong in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/11/17/the-urban-league…-strong-in-omaha/

Park Avenue Revitalization and Gentrification: InCommon Focuses on Urban Neighborhood

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/02/25/park-avenue-revi…ban-neighborhood/

Health and healing through culture and community

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/11/17/health-and-heali…re-and-community

Syed Mohiuddin: A pillar of the Tri-Faith Initiative in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/09/01/syed-mohiuddin-a…tiative-in-omaha

Re-entry prepares current and former incarcerated individuals for work and life success on the outside

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/01/10/re-entry-prepare…s-on-the-outside/

Frank LaMere: A good man’s work is never done

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/07/11/frank-lamere-a-g…rk-is-never-done

Behind the Vision: Othello Meadows of 75 North Revitalization Corp.

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/27/behind-the-visio…italization-corp

North Omaha beckons investment, combats gentrification

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/25/north-omaha-beck…s-gentrification

SAFE HARBOR: Activists working to create Omaha Area Sanctuary Network as refuge for undocumented persons in danger of arrest-deportation

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/06/29/safe-harbor-acti…rest-deportation

Heartland Dreamers have their say in nation’s capitol

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/24/heartland-dreame…-nations-capitol/

Of Dreamers and doers, and one nation indivisible under…

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/21/of-dreamers-and-…ndivisible-under/

Refugees and asylees follow pathways to freedom, safety and new starts

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/21/refugees-and-asy…y-and-new-starts

Coming to America: Immigrant-Refugee mosaic unfolds in new ways and old ways in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/10/coming-to-americ…ld-ways-in-omaha

History in the making: $65M Tri-Faith Initiative bridges religious, social, political gaps

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/25/history-in-the-m…l-political-gaps

A systems approach to addressing food insecurity in North Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/08/11/a-systems-approa…y-in-north-omaha

No More Empty Pots Intent on Ending North Omaha Food Desert

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/13/no-more-empty-po…t-in-north-omaha

Poverty in Omaha:

Breaking the cycle and the high cost of being poor

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/01/03/poverty-in-omaha…st-of-being-poor/

Down and out but not done in Omaha: Documentary surveys the poverty landscape

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/11/03/down-and-out-but…overty-landscape

Struggles of single moms subject of film and discussion; Local women can relate to living paycheck to paycheck

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/10/24/the-struggles-of…heck-to-paycheck

Aisha’s Adventures: A story of inspiration and transformation; homelessness didn’t stop entrepreneurial missionary Aisha Okudi from pursuing her goals

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/07/10/aisha-okudis-sto…rsuing-her-goals

Omaha Community Foundation project assesses the Omaha landscape with the goal of affecting needed change

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/05/10/omaha-community-…ng-needed-change/

Nelson Mandela School Adds Another Building Block to North Omaha’s Future

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/01/24/nelson-mandela-s…th-omahas-future

Partnership 4 Kids – Building Bridges and Breaking Barriers

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/06/03/partnership-4-ki…reaking-barriers

Changing One Life at a Time: Mentoring Takes Center Stage as Individuals and Organizations Make Mentoring Count

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/01/05/changing-one-lif…-mentoring-count/

Where Love Resides: Celebrating Ty and Terri Schenzel

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/02/where-love-resid…d-terri-schenzel/

North Omaha: Voices and Visions for Change

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/29/north-omaha-voic…sions-for-change

Black Lives Matter: Omaha activists view social movement as platform for advocating-making change

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/08/26/black-lives-matt…ng-making-change

Change in North Omaha: It’s been a long time coming for northeast Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/08/01/change-in-north-…-northeast-omaha/

Girls Inc. makes big statement with addition to renamed North Omaha center

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/23/girls-inc-makes-…rth-omaha-center

NorthStar encourages inner city kids to fly high; Boys-only after-school and summer camp put members through their paces

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/06/17/northstar-encour…ough-their-paces/

Big Mama, Bigger Heart: Serving Up Soul Food and Second Chances

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/10/17/big-mama-bigger-…d-second-chances/

When a building isn’t just a building: LaFern Williams South YMCA facelift reinvigorates community

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/08/03/when-a-building-…-just-a-building/

Identity gets new platform through RavelUnravel

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/03/20/identity-gets-a-…ugh-ravelunravel/

Where Hope Lives, Hope Center for Kids in North Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/where-hope-lives…s-in-north-omaha/

Crime and punishment questions still surround 1970 killing that sent Omaha Two to life in prison

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/03/30/crime-and-punish…o-life-in-prison/

A WASP’s racial tightrope resulted in enduring book partially set in 1960s Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/28/a-wasps-racial-t…t-in-1960s-omaha/

Gabriela Martinez:

A heart for humanity and justice for all

https://leoadambiga.com/2018/03/08/16878

Father Ken Vavrina’s new book “Crossing Bridges” charts his life serving others

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/29/father-ken-vavri…e-serving-others/

Wounded Knee still battleground for some per new book by journalist-author Stew Magnuson

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/04/20/wounded-knee-sti…or-stew-magnuson

‘Bless Me, Ultima’: Chicano identity at core of book, movie, movement

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/09/14/bless-me-ultima-…k-movie-movement

Finding Normal: Schalisha Walker’s journey finding normal after foster care sheds light on service needs

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/07/18/finding-normal-s…on-service-needs/

Dick Holland remembered for generous giving and warm friendship that improved organizations and lives

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/02/08/dick-holland-rem…ations-and-lives/

Justice champion Samuel Walker calls It as he sees it

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/30/justice-champion…it-as-he-sees-it

![[© Ellen Lake]](https://i0.wp.com/www.crmvet.org/crmpics/64fs_gulfport1.jpg)

Photo caption:

Walker on far left of porch of a Freedom Summer

El Puente: Attempting to bridge divide between grassroots community and the system

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/22/el-puente-attemp…y-and-the-system

All Abide: Abide applies holistic approach to building community; Josh Dotzler now heads nonprofit started by his parents

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/12/05/all-abide-abide-…d-by-his-parents/

Making Community: Apostle Vanessa Ward Raises Up Her North Omaha Neighborhood and Builds Community

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/13/making-community…builds-community/

Collaboration and diversity matter to Inclusive Communities: Nonprofit teaches tools and skills for valuing human differences

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/09/collaboration-an…uman-differences

Talking it out: Inclusive Communities makes hard conversations the featured menu item at Omaha Table Talk

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/05/02/talking-it-out-i…omaha-table-talk/

Everyone’s welcome at Table Talk, where food for thought and sustainable race relations happen over breaking bread together

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/16/everyones-welcom…g-bread-together/

Feeding the world, nourishing our neighbors, far and near: Howard G. Buffett Foundation and Omaha nonprofits take on hunger and food insecurity

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/11/22/feeding-the-worl…-food-insecurity

Rabbi Azriel: Legacy as social progressive and interfaith champion secure

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/05/15/rabbi-azriel-leg…-champion-secure

Rabbi Azriel’s neighborhood welcomes all, unlike what he saw on recent Middle East trip; Social justice activist and interfaith advocate optimistic about Tri-Faith campus

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/09/06/rabbi-azriels-ne…tri-faith-campus/

Ferial Pearson, award-winning educator dedicated to inclusion and social justice, helps students publish the stories of their lives

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/25/ferial-pearson-a…s-of-their-lives/

Upon This Rock: Husband and Wife Pastors John and Liz Backus Forge Dynamic Ministry Team at Trinity Lutheran

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/02/upon-this-rock-h…trinity-lutheran/

Gravitas – Gravity Center for Contemplative Activism founders Christopher and Phileena Heuertz create place of healing for healers

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/04/01/gravitas-gravity…ling-for-healers/

Art imitates life for “Having Our Say” stars, sisters Camille Metoyer Moten and Lanette Metoyer Moore, and their brother Ray Metoyer

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/05/art-imitates-lif…ther-ray-metoyer

Color-blind love:

Five interracial couples share their stories

https://leoadambiga.com/2014/02/06/color-blind-love…re-their-stories

A Decent House for Everyone: Jesuit Brother Mike Wilmot builds affordable homes for the working poor through Gesu Housing

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/09/a-decent-house-f…ugh-gesu-housing

Bro. Mike Wilmot and Gesu Housing: Building Neighborhoods and Community, One House at a Time

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/04/27/bro-mike-wilmot-…-house-at-a-time/

Omaha native Steve Marantz looks back at city’s ’68 racial divide through prism of hoops in new book, “The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central”

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/04/01/omaha-native-ste…of-omaha-central/

Anti-Drug War manifesto documentary frames discussion:

Cost of criminalizing nonviolent offenders comes home

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/02/01/an-anti-drug-war…nders-comes-home

Documentary shines light on civil rights powerbroker Whitney Young: Producer Bonnie Boswell to discuss film and Young

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/03/21/documentary-shin…e-film-and-young

Civil rights veteran Tommie Wilson still fighting the good fight

https://leoadambiga.com/2015/05/07/civil-rights-vet…g-the-good-fight

Rev. Everett Reynolds Gave Voice to the Voiceless

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/18/rev-everett-reyn…to-the-voiceless/

Lela Knox Shanks: Woman of conscience, advocate for change, civil rights and social justice champion

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/04/lela-knox-shanks…ocate-for-change

Omahans recall historic 1963 march on Washington

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/08/12/omahans-recall-h…ch-on-washington

Psychiatrist-Public Health Educator Mindy Thompson Fullilove Maps the Root Causes of America’s Inner City Decline and Paths to Restoration

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/04/psychiatrist-pub…s-to-restoration/

A force of nature named Evie:

Still a maverick social justice advocate at 100

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/16/a-force-of-natur…e-advocate-at-99

Home is where the heart Is for activist attorney Rita Melgares

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/20/home-is-where-th…ey-rita-melgares/

Free Radical Ernie Chambers subject of new biography by author Tekla Agbala Ali Johnson

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/12/05/free-radical-ern…bala-ali-johnson

Carolina Quezada leading rebound of Latino Center of the Midlands

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/03/carolina-quezada…-of-the-midlands/

Returning To Society: New community collaboration, research and federal funding fight to hold the costs of criminal recidivism down

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/02/returning-to-soc…-recidivism-down

Getting Straight: Compassion in Action expands work serving men, women and children touched by the judicial and penal system

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/05/22/getting-straight…and-penal-system

OneWorld Community Health: Caring, affordable services for a multicultural world in need

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/09/oneworld-communi…al-world-in-need

Dick Holland responds to far-reaching needs in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/dick-holland-res…g-needs-in-omaha/

Gender equity in sports has come a long way, baby; Title IX activists-advocates who fought for change see much progress and the need for more

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/06/11/gender-equity-in…he-need-for-more/

Giving kids a fighting chance: Carl Washington and his CW Boxing Club and Youth Resource Center

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/12/03/giving-kids-a-fi…-resource-center/

Beto’s way: Gang intervention specialist tries a little tenderness

http://leoadambiga.com/2015/10/28/betos-way-gang-i…ittle-tenderness/

Saving one kid at a time is Beto’s life work

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/01/24/saving-one-kid-a…-betos-life-work

Community trumps gang in Fr. Greg Boyle’s Homeboy model

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/21/community-trumps…es-homeboy-model/

Born again ex-gangbanger and pugilist, now minister, Servando Perales makes Victory Boxing Club his mission church for saving youth from the streets

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/12/19/born-again-ex-ga…from-the-streets/

Turning kids away from gangs and toward teams in South Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/17/turning-kids-awa…s-in-south-omaha/

“Paco” proves you can come home again

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/09/paco-proves-you-…-come-home-again

Two graduating seniors fired by dreams and memories, also saddened by closing of school, St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/05/11/two-graduating-s…igh-in-omaha-neb/

St. Peter Claver Cristo Rey High: A school where dreams matriculate

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/st-peter-claver-…eams-matriculate/

Open Invitation: Rev. Tom Fangman engages all who seek or need at Sacred Heart Catholic Church

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/01/09/an-open-invitati…-catholic-church/

Outward Bound Omaha uses experiential education to challenge and inspire youth

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/04/26/outward-bound-om…nd-inspire-youth

After steep decline, the Wesley House rises under Paul Bryant to become youth academy of excellence in the inner city

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/08/27/after-a-steep-de…n-the-inner-city

Freedom riders: A get on the bus inauguration diary

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/10/21/get-on-the-bus-a…-ride-to-freedom/

The Great Migration comes home: Deep South exiles living in Omaha participated in the movement author Isabel Wilkerson writes about in her book, “The Warmth of Other Suns”

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/03/31/the-great-migrat…th-of-other-suns/

When New Horizons dawned for African-Americans seeking homes in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2013/01/17/when-new-horizon…ericans-in-omaha/

Good Shepherds of North Omaha: Ministers and churches making a difference in area of great need

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/04/the-shepherds-of…ea-of-great-need

Academy Award-nominated documentary “A Time for Burning” captured church and community struggle with racism

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/12/15/a-time-for-burni…ggle-with-racism/

Letting 1,000 Flowers Bloom: The Black Scholar’s Robert Chrisman Looks Back at a Life in the Maelstrom

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/03/08/letting-1000-flo…in-the-maelstrom

Coloring History:

A long, hard road for UNO Black Studies

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/25/coloring-history…no-black-studies

Two Part Series: After Decades of Walking Behind to Freedom, Omaha’s African-American Community Tries Picking Up the Pace Through Self-Empowered Networking

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/02/13/two-part-series-…wered-networking

Power Players, Ben Gray and Other Omaha African-American Leaders Try Improvement Through Self-Empowered Networking

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/07/09/power-players-be…wered-networking/

Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/04/native-omahans-t…n-their-hometown

Overarching plan for North Omaha development now in place: Disinvested community hopeful long promised change follows

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/07/29/overarching-plan…d-change-follows/

Standing on Faith, Sadie Bankston Continues One-Woman Vigil for Homicide Victim Families

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/standing-on-fait…-victim-families/

Forget Me Not Memorial Wall

North Omaha champion Frank Brown fights the good fight

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/01/15/north-omaha-cham…s-the-good-fight/

Man on fire: Activist Ben Gray’s flame burns bright

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/09/02/ben-gray-man-on-fire/

Strong, Smart and Bold, A Girls Inc. Success Story

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/strong-smart-and…-girls-inc-story

What happens to a dream deferred?

John Beasley Theater revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun”

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/14/what-happens-to-…aisin-in-the-sun

Brown v. Board of Education:

Educate with an Even Hand and Carry a Big Stick

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/07/brown-v-board-of…arry-a-big-stick/

Fast times at Omaha’s Liberty Elementary: Evolution of a school

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/07/05/fast-times-at-om…tion-of-a-school/

New school ringing in Liberty for students

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/06/new-school-ringi…rty-for-students

Nancy Oberst: Pied Piper of Liberty Elementary School

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/06/nancy-oberst-the…lementary-school/

Tender Mercies Minister to Omaha’s Poverty Stricken

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/tender-mercies-m…poverty-stricken/

Community and coffee at Omaha’s Perk Avenue Cafe

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/04/community-and-co…perk-avenue-cafe/

Whatsoever You Do to the Least of My Brothers, that You Do Unto Me: Mike Saklar and the Siena/Francis House Provide Tender Mercies to the Homeless

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/01/whatsoever-you-d…t-you-do-unto-me/

Gimme Shelter: Sacred Heart Catholic Church Offers a Haven for Searchers

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/gimme-shelter-sa…en-for-searchers

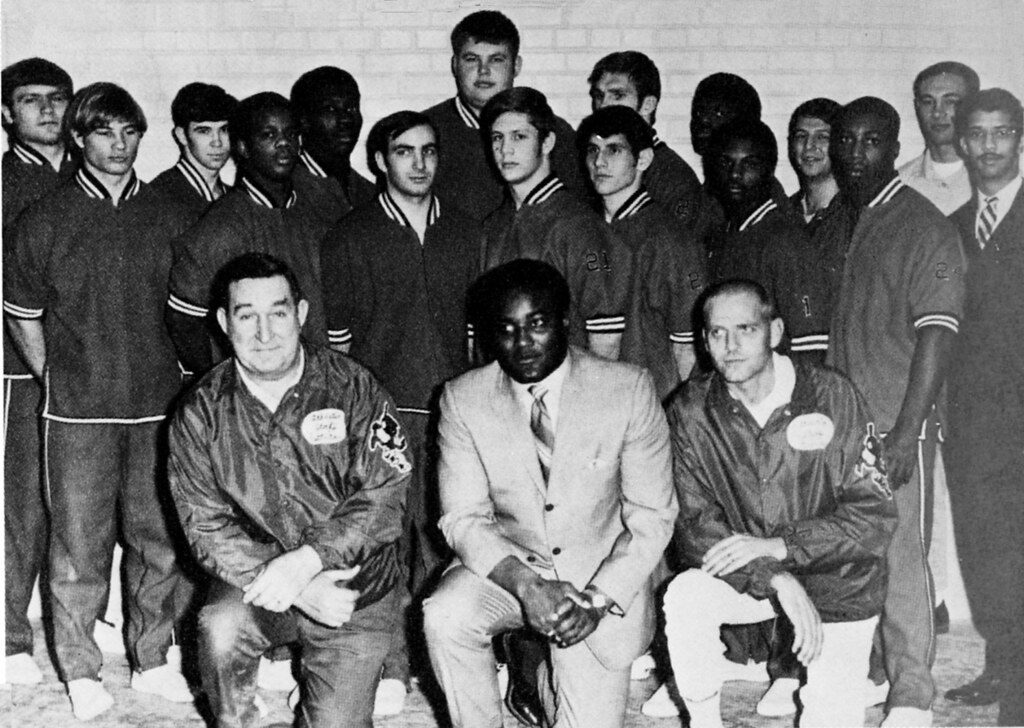

UNO wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/03/17/uno-wrestling-dy…-social-change-2

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/02/a-brief-history-…apher-rudy-smith/

Hidden In plain view: Rudy Smith’s camera and memory fix on critical time in struggle for equality

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/08/29/hidden-in-plain-…gle-for-equality/

Small but mighty group proves harmony can be forged amidst differences

https://leoadambiga.com/2016/11/14/small-but-mighty…idst-differences/

Winners Circle: Couple’s journey of self-discovery ends up helping thousands of at-risk kids through early intervention educational program

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/couples-journey-…-of-at-risk-kids

A Mentoring We Will Go

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/06/18/a-mentoring-we-will-go

Abe Sass: A mensch for all seasons

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/05/02/abe-sass-a-mensch-for-all-seasons

Shirley Goldstein: Cream of the Crop – one woman’s remarkable journey in the Free Soviet Jewry movement

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/09/05/shirley-goldstei…t-jewry-movement/

Flanagan-Monsky example of social justice and interfaith harmony still shows the way seven decades later

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/31/flanagan-monsky-…y-60-years-later/

A Contrary Path to Social Justice: The De Porres Club and the fight for equality in Omaha

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/01/a-contrary-path-…quality-in-omaha/

Hey, you, get off of my cloud! Doug Paterson is acolyte of Theatre of the Oppressed founder Augusto Boal and advocate of art as social action

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/03/hey-you-get-off-…as-social-action/

Doing time on death row: Creighton University theater gives life to “Dead Man Walking”

https://leoadambiga.com/2012/01/10/doing-time-on-de…dead-man-walking/

“Walking Behind to Freedom” – A musical theater examination of race

https://leoadambiga.com/2011/06/21/walking-behind-t…mination-of-race/

Bertha’s Battle: Bertha Calloway, the Grand Lady of Lake Street, struggles to keep the Great Plains Black History Museum afloat

https://leoadambiga.com/2010/05/11/berthas-battle

Leonard Thiessen social justice triptych deserves wider audience

https://leoadambiga.com/2017/01/21/leonard-thiessen…s-wider-audience/

Gabriela Martinez: A heart for humanity and justice for all

Gabriela Martinez: A heart for humanity and justice for all

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in a February 2018 issue of El Perico ( http://el-perico.com/ )

Like many young Omaha professionals, Gabriela Martinez is torn between staying and spreading her wings elsewhere.

The 2015 Creighton University social work graduate recently left her position at Inclusive Communities to embark on an as yet undefined new path. This daughter of El Salvadoran immigrants once considered becoming an immigration lawyer and crafting new immigration policy. She still might pursue that ambition, but for now she’s looking to continue the diversity and inclusion work she’s already devoted much of her life to.

Unlike most 24-year-olds. Martinez has been a social justice advocate and activist since childhood. She grew up watching her parents assist the Salvadoran community, first in New York, where her family lived, and for the last two decades in Omaha.

Her parents escaped their native country’s repressive regime for the promise of America. They were inspired by the liberation theology of archbishop Oscar Romero, who was killed for speaking out against injustice. Once her folks settled in America, she said, they saw a need to help Salvadoran emigres and refugees,

“That’s why they got involved. They wanted to make some changes, to try to make it easier for future generations and to make it easier for new immigrants coming into this country.”

She recalls attending marches and helping out at information fairs.

In Omaha, her folks founded Asociación Cívica Salvadoreña de Nebraska, which works with Salvadoran consulates and partners with the Legal immigrant Center (formerly Justice for Our Neighbors). A recent workshop covered preparing for TPS (Temporary Protected Status) ending in 2019.

“They work on getting people passports, putting people in communication with Salvadoran officials. If someone is incarcerated, they make sure they know their rights and they’re getting access to who they need to talk to.”

Martinez still helps with her parents’ efforts, which align closely with her own heart.

“I’m very proud of my roots,” she said. “My parents opened so many doors for me. They got me involved. They instilled some values in me that stuck with me. Seeing how hard they work makes me think I’m not doing enough. so I’m always striving to do more and to be the best version of myself that I can be because that’s what they’ve worked their entire lives for.”

Martinez has visited family in El Salvador, where living conditions and cultural norms are in stark contrast to the States.

She attended an Inclusive Communities camp at 15, then became a delegate and an intern, before being hired as a facilitator for the nonprofit’s Table Talk series around issues of racism and inequity. She enjoyed “planting seeds for future conversations” and “giving a voice to people who think they don’t have one.”

Inclusive Communities fostered personal growth.

“People I went to camp with are now on their way to becoming doctors and lawyers and now they’re giving back to the community. I’m most proud of the youth I got to work with because they taught me as much as I taught them and now I see them out doing the work and doing it a thousand times better than I do.

“I love seeing how far they’ve come. Individuals who were quiet when I first met them are now letting their voices be heard.”

Martinez feels she’s made a difference.

“I love seeing the impact I left on the community – how many individuals I got to facilitate in front of and programs I got to develop.”

She’s worked on Native American reservations, participated in social justice immersion trips and conferences and supported rallies.

“I’m most proud when I see other Latinos doing the work and how passionate they are in being true to themselves and what’s important to them. There’s a lot of strong women who have taken the time to invest in me. Someone I really look up to for her work in politics is Marta Nieves (Nebraska Democratic Party Latino Caucus Chair). I really appreciate Marta’s history working in this arena.”

Martinez is encouraged that Omaha-transplant Tony Vargas has made political inroads, first on the Omaha School Board, and now in the Nebraska Legislature.

As for her own plans, she said, “I’m being very intentional about making sure my next step is a good fit and that i’m wanting to do the work not because of the money but because it’s for a greater good.”

Though her immediate family is in Omaha, friends have pursued opportunities outside Nebraska and she may one day leave to do the same.

“I’d like to see what I can accomplish in Omaha, but I need a bigger city and I need to be around more diversity and people from different backgrounds and cultures that I can learn from. I think Omaha is too segregated.”

Like many millennials, she feels there are too many barriers to advancement for people of color here.

“This community is still heavily dominated by non-people of color.”

Wherever she resides, she said “empowering and advocating” for underserved people “to be heard in different spaces”.will be core to her work.

Despite gains made in diversity and inclusion, she feels America still has a long way to go. She’s seen too many workplaces let racism-sexism slide and too many environments where individuals reporting discrimination are told they’re “overreacting” or “too ‘PC.'” That kind of dismissive attitude, she said, cannot stand and she intends to be a voice for those would be silenced.

Lourdes Gouveia: Leaving a legacy but keeping a presence

One of the smartest and kindest people I know, Lourdes Gouveia, has stepped down from directing the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies of the Great Plains or OLLAS, a program she helped found at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. A sociologist by training and practice, she and her program have helped the university, policymakers and other stakeholders in the state better understand the dynamics of the ever growing and more fluid Latino immigrant and Latin American population. OLLAS has become a go-to resource for those wanting a handle on what’s happening with that population. She is very passionate about what she’s built, the strong foundation laid down for its continued success and the continuing research she’s doing. Though no longer the director, she’s still very much engaged in the work of OLLAS and related fields of interests. She’s still very much a part of the UNO scene.

Lourdes Gouveia: Leaving a legacy but keeping a presence

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in El Perico

When sociology professor and researcher Lourdes Gouveia joined the University of Nebraska at Omaha faculty in 1989 it coincided with the giant Latino immigration wave then impacting rural and urban communities.

Little did she know then she would found the Office of Latino/Latin American Studies of the Great Plains or OLLAS in 2003. She recently stepped down as director of that prestigious center she’s closely identified with.

The idea for OLLAS emerged after her field work in Lexington, Neb. documenting challenges and opportunities posed by the influx of new arrivals on communities that hadn’t received immigrants in a century. She focused on the labor trend of Latinos recruited into meatpacking. While doing a post-doctorate fellowship at Michigan State University she came to see the global implications of mobile populations.

“It really did become a transformative experience,” recalls the Venezuela native and University of Kansas graduate. “It gave me a whole new level of understanding of issues I had been working on. It opened opportunities I had no idea we’re going to be so influential and consequential in my life. These were colleagues as motivated as I was to try to understand this tectonic and dramatic shift going on of increased immigration from Latin America accompanied with an economic recession in the United States.

“I learned a tremendous amount. It just opened a lens that gave me confidence to understand this shift in a larger context.”

When Gouveia returned from her post doc she accepted an invitation to head what was just a minor in Latino Studies at UNO.

“I said yes but with a condition we explore something larger. Many of us were beginning to realize the minor was just not enough of a space to understand, to educate our students, to work with the community on issues of this magnitude.”

She led a committee that conceived and launched OLLAS and along with it a major in Latin American Studies.

“OLLAS was built upon a very clear vision that Neb. and Omaha in particular was seeing profound changes in the makeup of the Latino immigrant and Latino American population. Neither the university nor the community, let alone policymakers. were sufficiently prepared to understand the significance of those changes and their long-term consequences or respond in any informed, data-driven, rationale way. That message resonated with people on the ground and at the top.”

Lourdes Gouveia (far right) is the Director of OLLAS at UNO. (Photo Courtesy UNO)

Significant seed money for making OLLAS a reality came from a $1 million U.S. Department of Education grant that then-Sen. Chuck Hagel helped secure.

From the start, Gouveia says OLLAS has existed as a hybrid, interdisciplinary center that not only teaches but conducts research and generates content-rich reports.

“Community agencies, policymakers, students and others tell us they find enormous value in those research reports and fact sheets we produce. That is a mainstay of what we do. It’s done with a lot of difficulty because they require enormous work, expert talent and rigor and we don’t always have the resources at hand. Yet we have maintained that and hope to expand that.”

She says OLLAS is unlike anything else at UNO.

“We’re an academic program but we’re also a community project. So we’re constantly engaging, partnering, discussing, conversing with community organizations, even government representatives from Mexico and Central America, in projects we think enhance that understanding of these demographic changes. We’re also looking at the social-economic conditions of the Latino population and what it has to do with U.S. immigration or U.S. involvement in Latin America.”

OLLAS also plays an advocacy role.

“We use our voices in public, whether writing op-ed pieces or holding meetings and conferences with political leaders or elected officials. We use our research to make our voices heard and to inform whatever issues policymakers may be debating, such as the refugee crisis.”

Gouveia says the way OLLAS is structured “allows us to be very malleable, more like a think tank.” adding, “We define ourselves as perennial pioneers always trying to anticipate the questions that need answers or the interests emerging we can fulfill. It’s extremely exhausting because we’re constantly inventing and innovating but it’s extremely rewarding. We’re about to put out a report, for example, on the changes of the Latino population across the city. Why? Because we are observing Latinos are not just living in South Omaha but are spread across the city. As we detect trends like this on the ground we try to anticipate and answer questions to give people the tools to use the information in their work. That guarantees we’re always going to be relevant to all these constituencies.”

OLLAS faculty and staff

OLLAS has grown in facilities and staff, including a project coordinator, a community engagement coordinator and research associates, and in currency. Gouveia says, “I’m very satisfied we did it right. We thoughtfully arrived correctly at the decision we just couldn’t be a regular department offering courses and graduating students but we also had to produce knowledge. Our reports are a good vehicle for putting out information in a timely manner about a very dynamic population and set of population changes.”

She says OLLAS could only have happened with the help of many colleagues, including Jonathan Benjamin-Alvarado and Theresa Barron-McKeagney, “who shared enthusiastically in the mission we were forging.” She say OLLAS has also received broad university support and community philanthropic support.

“There was resistance, too,” she adds. “It’s a very creative space that breaks with all conventions. Like immigrants we create fear that somehow we’re shaking the conventional wisdom. But I think our success has converted many who were initially skeptical. I think we’ve pioneered models that others have come to observe and learn from.”

One concern she has is that as Latino students in the program have increased UNO’s not kept apace its hiring of Latino faculty.

A national search is underway for her successor.

“I feel very good about stepping out at this time. It surprised a lot of people. As a founding director you cannot stay there forever. Once you have helped institutionalize the organization then it’s time to bring in the next generation of leaders with fresh visions and ideas.”

Besides, there’s research she’s dying to get to. And it’s not like this professor emeritus is going away. She confirms she’ll remain “involved with OLLAS, but in a different way.”

Visit http://www.unomaha.edu/ollas/.

Finding Normal: Schalisha Walker’s journey finding normal after foster care sheds light on service needs

After my Aisha Okudi story last week I promised another story of inspiration and transformation and here it is, my new Reader (www.thereader.com) cover story profiling Schaiisha Walker, a young woman whose journey finding normal after foster care led her to a Nebraska program called Project Everlast. It provides young people leaving or having already left foster care with much needed support. Schalisha had found herself on her own at 17, sometimes homeless, dropping out of school to support herself, working as many as four jobs at one point, going from couch to couch until she got a place of her own. It’s only by the grace of God she survived that experience. She’s now employed as a Project Everlast youth advisor. I came to do this story about her because I attended a performance by actor-spoken word artist Damiel Beaty last winter at the Holland Performing Arts Center in Omaha and before he came on Schalisha appeared on stage to introduce him. Her heart-felt words as well as her poise and grace struck me to the core. She shared how deeply Beaty’s work, much of it drawn from his own harsh childhood, resonated with her, especially his message that one can rise above and overcome anything. She’s a model for that herself. You go, girl.

|

Finding Normal: Schalisha Walker’s journey finding normal after foster care sheds light on service needs

Project Everlast provides support for young people as they age-out of the system

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Before a Feb. 27 packed house at the Holland Performing Arts Center a woman strode on stage to introduce playwright-poet-performance artist Daniel Beaty.

Schalisha Walker, 25, was unknown to all but a few in the audience. She was there to not only introduce Beaty but to deliver a personal message about the hundreds of foster care youth who age or drop out of the system each year in Nebraska. These young people, she noted, can find themselves adrift without a helping hand. She knows because she was one of them, Walker was at the Holland representing Project Everlast, a statewide, youth-led initiative that assists current and former foster care youth to smooth their transition into adulthood.

This former ward of the state has successfully transitioned from life on the edge to the picture of achievement. Her story of perseverance is not unlike Beaty’s own saga. In his work he often refers to the crazy things his drug addict, in-and-out-of-prison father exposed him to. The performing arts saved Beaty by giving him a vehicle for his angst and a platform for expressing his credo that one can rise above anything.

Walker’s risen above a whole lot of chaos.

She says, “My mother was extremely young (15) when she had me and she was unable to care for me properly. I was about 2 when I went in the (foster care) system and I was 4 when I was adopted.”

Separated from her six siblings, things happened within her adoptive family that prompted her to leave and go off on her own at 17. She finally found a safe haven at Everlast, where she got the support she never had before. She served on the youth council that helps formulate the organization’s programs and policies and she shared her story with the public in speaking appearances.

She now works as a youth advisor with Everlast, a Nebraska Children and Families Foundation program. Introducing Beaty wasn’t the first time she’s been the face and voice of Everlast and the foster care community. She appeared in a documentary about the project and she’s been featured on its website.

“This is truly an organization with people committed to the work,” she says. “Our job doesn’t stop when we leave the office. It’s like a family, I really mean that.”

This fall she’s starting school at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where she hopes to earn a social work degree.

“I’ve always wanted to help children in need. It’s really natural for me. I was fortunate to get a job here (Everlast). I love what I do and I do it with my heart.”

That night at the Holland she stood tall, black and beautiful invoking Beaty’s poetic testimony to share her own overcoming journey and the role she plays today as a mentor for otherwise forgotten young people.

Reading from Beaty’s poem “Knock, Knock” she exhorted, “‘We are our fathers’ sons and daughters but we are not their choices. For despite their absences we are still here, still alive, still breathing with the power to change this world one little boy and girl at a time.’ The words struck me to the core. They convey the passion I have for using my experience to help young people with a foster care background struggling and feeling alone as I did…

“For many years I let my past keep me from my future but now I use my past to help others. Let me be the voice for those that have not found theirs yet.”

Having walked in the shoes of the young people she engages, she understands the challenges they face and the needs they express. It’s almost like looking in the mirror and seeing herself five-six years ago.

“It’s a powerful identification. Struggling with unhealthy relationships, a feeling of being alone or having no one to turn to or looking for a job and not knowing what’s the best decision to make – I see that on a regular basis. I see myself in a lot of these young girls, especially when it comes to the unhealthy relationships. I see so many young people who just want to be loved and accepted. Unfortunately, a lot of times what happens is they get in the wrong crowd. Looking back, I was in some very scary situations.

“I’m glad I’m at a point now where I can offer advice from having been there and making the wrong decisions and now making better decisions. Now I can use my life experiences to say, ‘Hey, this is what happened to me, I don’t want this to happen to you, I want to help you.’ I feel I’m like an older sister or a mother to them.”

Schalisha giving a homemade pecan pie, baked by a volunteer, to a young woman on her birthday.

Just as she’s a mother to the kids she serves, Everlast associate vice president Jason Feldhaus is a father to her.

“He’s very much like a dad to me,” Walker says of him. “You might as well say he is my dad. I talk to him a lot. That’s a relationship that was built. He was in my position when I was in youth council – he was my youth advisor.”

Feldhaus says there “was just something different about Schalisha from the very beginning.” He explains, “She was very organized, very committed, very mature. Even early on she just always seemed dedicated to something bigger to help make things better for people. The young people she works with bond to her and so no matter where their life is in flux they still keep coming back to Project Everlast and I think a lot of that has to do with her ability to connect to them.”

Walker says the disruptions that can attend life in and out of foster care, such as moving from family to family or being separated from siblings, “can be very traumatic” and adversely affect one’s education and socialization. The more links to stability that are missing or broken, she says, “the more difficult it is to keep your life together.”

Everlast grew out of an Omaha Independent Living Plan initiated by Nebraska Children and Families Foundation to address resource needs and service gaps faced by foster youth. Foundation director of strategic relationships, Judy Dierkhising, who oversaw Everlast during a recent transition, estimates that of the 200 youth aging out of foster care in Douglas and Sarpy Counties each year 40 percent don’t have an adequate plan or support system in place. That’s not counting individuals who get lost in the system as Schalisha did. In Neb. youth age-out of the system at 19.

Until Everlast, Dierkhising says, “there were not a lot of services or programs dedicated to that transitional living piece that helped young folks look for housing, job and education opportunities.” The project bridges that gap by connecting young people to partner agencies, such as Youth Emergency Services, that offer needed resources.

”

We provide young people access to those services they need to live independently, to grow into adulthood, to have engagement with the community, to be successful educationally, to be connected to health care, et cetera. A number of young people we work with don’t have anybody else there for them. We help them to help themselves and hopefully to find some permanence in their life. We’re here to empower them, with whatever it takes, to know they can have an impact on the world and that the world isn’t doing it to them.

“We’re not trying to save them, we’re assisting them to be successful, just like Schalisha. She is a tremendous role model and advocate for how there is a way to survive this and to thrive.”

In the immediate years following the break from her adoptive family Walker had no one to formally guide or mentor her, which meant she had to figure out most things for herself.

“The experience with being adopted was very difficult and I ended up being on my own. It was very difficult, very lonely. I hadn’t even graduated high school yet. I had to drop out of school to work to support myself. I was working four jobs at one time. I had no choice because I didn’t have the support of a family like I should have. I didn’t have the support of friends because all my friends were still in high school.

“I ended up staying with some friends until I was able to have an apartment on my own.”

She says unstable housing is a major problem for foster youth once they leave the system.

“Homelessness is not uncommon. It is an ongoing issue. There’s a young man I work with who ever since he aged out was couch surfing. He now has a steady job and a safe place to live in. It’s very scary not having a safety net or a stable place to call home and that is a reality for many of these young people. It was a reality for me as well. In my case, I couldn’t go back to the home I was at. Just having a place to call your own where you feel safe and that you can go to every night can make a huge difference.”

Young people at at Project Everlast event were recognized for getting new jobs, moving into their own apartments, procuring scholarships and graduating high school. Schalisha served as an emcee for the program.

She says Everlast introduced her to youth and adults she could trust and count on to help her navigate life. Through its Opportunity Passport program she built her financial management skills, The dollars youth save are matched by donors. The program enabled her to retire the beater of a car she drove to buy a newer model vehicle.

“What I found was people that really cared about your success, people who really listened and wanted to be a support for you. It was like a relief finding people who had been through what I’d been through and I could share my story with. That was very powerful.”

Having that safety net is much healthier than going it alone, she says.

“That feeling of being alone and not being wanted can tear you apart. Having to make some of the decisions I did is something no child should have to go through. The experiences I had and some of the difficulties and struggles I dealt with is why I’m so passionate about making sure no other young person feels alone or feels they have no support and no one to turn to.”

She says the young people she works with all have different stories but they’re all trying to improve their life, whether going back to school or landing a job or finding a secure place to live or leaving an abusive relationship or getting treatment for drug or alcohol addiction.

“Any step forward is a success and makes my job worthwhile. That’s why it’s really important for me to be here doing this work.”

After dropping out of South High she earned her diploma through independent studies and lattended Metropolitan Community College.

Drawing on her own experience of never having her birthdays celebrated as a kid, which she says is common among foster youth, she created the No Youth Without a Birthday Treat initiative.

“What I like to focus on is giving them normal experiences they might not have had. It’s to make sure they have a cake or a pie or cookies or muffins, whatever they’d like, for their birthday because it’s a special day for them and I want them to feel special. To give that young person their first birthday cake and to see their joy is amazing.

“At Thanksgiving and Christmas we have a big event with a dinner and presents.”

She also makes sure young people experience arts and cultural events they may not otherwise get to enjoy. Until she was asked to introduce Daniel Beaty, Walker herself had never been to the Holland. Judy Dierkhising took her there a few days before the program and Walker was awed by the space. Though Schalisha had spoken to groups before, she’d never addressed an audience the size of the gathering that night for Beaty’s one-man show, Emergency. It was different, too, because this time she was communing with someone she regards as a kindred soul and whom she also considers “amazing.”

“Daniel Beaty is such a talent. His poetry is electrifying – it gives me chills to hear him speak and to watch him perform,” Walker says. “I’d never seen him in person, so to see him live was a whole other experience. I’d never seen anything like that before. It blew my mind. I’ll never forget that performance. It was such an honor to introduce him. It was so exciting and I was really nervous.”

Reiterating what she told the audience that evening, she says Beaty’s poem “Knock, Knock” deeply resonated with her.

“When I first heard that poem I cried. A lot of my passion comes from my experience. The reason I’m in the field I’m in and do the work I do is because of the experiences I had. His words that we are not our parents’ choices really touched me, really spoke to me. So did his story and the things he overcame and the struggles he went through.

“It made me believe that no matter what you come from you make your future. You don’t have to be a product of what you came from, you don’t have to be what people expect you to be, you can be so much greater. That is what is so amazing to me about him.”

Topping it all off, she says, “He was so nice to me. He’s so cool and laid-back and down-to-earth. He has this presence about him that screams awesomeness without him being cocky.”

One of the things she admires about Beaty – his resilience overcoming steep odds – is what she admires in the young people she serves.

“The resilience they have to overcome is amazing. They didn’t want to be in these difficult situations and they’re motivated to do what they need to in order to get out. So many of these young people are talented and smart. They have dreams and goals and aspirations.”

She recognizes the same drive in herself pushed her to excel.

“I wanted to show that despite the circumstances around me that I still could succeed. I just have a real fire and passion to not fail and to not become a statistic and to show other young people they can make it. It’s been a lot of work.”

When she takes stock of her journey, she says she sees “someone who’s overcome a lot,” adding, “I see someone I’m proud very, very proud of, but even now I still struggle accepting that and saying that because some of the emotional scars are still there.”

She’s motivated to pay forward what was given her, she says. “because young people are counting on me to be there for them.”

Gravitas – Gravity Center for Contemplative Activism founders Christopher and Phileena Heuertz create place of healing for healers

UPDATE: Pam and I participated in a weekend Grounding Retreat facilitated by the founders-directors of Gravity, A Center for Contemplative Activism and it lived up to everything that Christopher and Phileena Heuertz described to us when we met them several months ago. Here is a Metro Magazine story I wrote about the couple, their years of humanitarian work overseas and the mission of Gravity. The organization is based in Omaha, where they live and where Pam and I live. The Grounding Retreat was held at the St. Benedict Center near Schuyler, Neb., a lovely place to experience and connect to the truth that our Higher Power speaks in the scriptures:

Be still, and know that I am God.

I look forward to doing another retreat and to writing a new story one day about the work of this amazing couple, especially now that I have seen them in action.

OLD INTRO: The more I look around the more I appreciate just how many interesting stories are available to me right in my hometown of Omaha, Neb. if I just open my eyes and my heart to what’s here. As I expand my vision, I see more than I did before. There’s also a law of attraction thing going on whereby as my personal spiritual journey ramps up more and more stories of people’s own spiritual journeys and personal transformations present themselves to me. One such story is that of Gravity, A Center for Contemplative Activism, which I’ve posted here. This feature for Omaha’s Metro Magazine is really a profile of the married couple behind the center, Christopher and Phileena Heuertz, and a chronicle of the serious traveling they’ve done – physically, emotionally and spiritually – to arrive at the place of healing they operate for fellow healers like themselves.

Christopher and Phileena Heuertz

Gravitas

Gravity Center for Contemplative Activism founders Christopher and Phileena Heuertz create place of healing for healers

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in Metro Magazine (http://www.spiritofomaha.com/Metro-Magazine/The-Magazine/)

After serving the poorest of the poor, an Omaha couple now helps heal fellow healers.

Omaha is a world away from the slums of Calcutta, the killing fields of Sierra Leone or the red light districts of South America. But the human pain found there is never far from the hearts and minds of a spiritually enlightened local couple who worked among the suffering in these and similarly challenged places for nearly two decades.

Christopher and Phileena Heuertz are 40-something-year-olds who’ve devoted much of their adult lives to social justice activism with the poorest of the poor, all the while led by the scripture admonition “faith without works is dead.” Growing up – he’s from Omaha and she’s from Indiana – each had powerful do-the-right-thing examples of radical hospitality in their own lives. His parents took in foster care kids in crisis and adopted two at-risk children. Later, his folks founded and ran a local agency to help resettle Sudanese refugees. Her father is a Protestant pastor and the senior chaplain for the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department.

By the time the couple met at a small liberal arts Christian college in Kentucky Chis had already done service work on a Navajo reservation, in Cabrini Green Chicago and in South India and Southeast Asia. In love with him and their shared commitment to serve others, Phileena joined him overseas.

The many hard things they witnessed brought them to a crucible of faith that now has them dedicated to nurturing the spirits of people whose human service vocations align with their own.

A new path

In 2012 they founded the Omaha-based Gravity, a Center for Contemplative Activism. Officed in the Mastercraft Building in North Downtown, where kindred spirit creatives, entrepreneurs and social justice warriors (at Siena/Francis House) are their neighbors, the center is the arm for their new outreach focus. The couple’s new mission finds them leading prayer sits and pilgrimages and giving retreats and spiritual direction in support of people like themselves committed to humanitarian work. The Heuertzes know first-hand how draining that work can be and therefore how vital it is to have a discipline or method or sanctuary in order to get refreshed.

Chris says, “We’re trying to create this sort of pit stop for the activist soul to catch their breath, to be refueled, to find practices that will help sustain their vocations and journeys.”

Many of the practices are contemplative in nature, meaning they emphasize silent prayer, meditation and reflection which nurtures self-awareness or consciousness. Centering prayer is one such practice.

Gravity does some of this work right at its spacious office, such as the weekly prayer sits and spiritual direction. and holds retreats at the St. Benedict Center in Schuyler, Neb. and around the country. The husband and wife team leads pilgrimages to historic sacred spots around the world (Assisi, Italy) and to historic social justice locales around the world (Rwanda). In the U.S. pilgrmmage has focused on “21st Century Freedom Rides” revisiting civil rights sites in the South. The couple also does workshops and makes presentations for communities, churches and universities across the nation.

“Gravity is for people who care about their spirituality and want to make the world a better place,” says Phileena, who completed her certification as a spiritual director. “Since Gravity opened its doors we’re finding that people from all different walks of life are coming. Even if they’re not in formal social justice work many of these people want to make the world a better place and they’re doing that in their way through their unique vocation.”

The couple came to start Gravity after reaching a point where they needed their own reset. They intentionally took time off to minister to themselves, along the way finding some spiritual practices they found beneficial for their own peace of mind and spiritual growth and that they now share with others.

After years working in the trenches with the destitute, the desperate and the dying they took a sabbatical in 2007. For part of their time away from the fray they made a famed pilgrimage in Spain, the Camino de Santiago, that saw them walk almost 800 kilometers (500 miles) across southern France and northern Spain on a 33-day trek. There, under the stars, unplugged from modem life, they discovered some essential truths.

“Every night on the Camino we’d stop at a convent or monastery or pilgrim house,” says Chris. “For 1,100 years these folks have practiced hospitality. You’re so exhausted after walking 25 or 30 kilometers, carrying everything in your pack, and then these folks welcome you in, saying, ‘Here’s a hot meal, here’s the shower, you can wash your clothes, we’ll make you breakfast in the morning and send you on your way.’ And it just always refreshed our spirits, our souls, our bodies, and that’s what we want to do through the center. We want to offer these little glimpses of hope and tools of nourishment for the activist soul to keep going, to keep fighting for a better world and not give up.”

During that same sabbatical period the Heuertzes received a fellowship from the Center for Reconciliation at Duke Divinity School in Durham, North Carolina.

“They hosted us,” says Chris,”and we found it such a great place for reflecting deeply on very difficult things in the world with a very diverse group of people.”

These experiences of taking time out for solitude, reflection, community and rejuvenation set this always searching couple on a new path, this time not directly tending to the suffering but to those who serve the suffering. Thus, their new mission is healing the healers.

Taking stock

In all the time Phileena and Chris served the oppressed, the exploited, the hungry, the sick and the dying, surrounded by a sea of want and hopelessness, they saw many of their colleagues lose their bearings.

“We worked all over the world and saw pretty messed up stuff and we saw a lot of great people burn out and walk away from their beliefs or faith or communities or vocations,” says Chris.

The couple came close to their own personal breaking points.

He says, “What we experienced in 19 years of really grassroots, gritty, on-the-streets, in-the-neighborhoods difficult work was that we gave a lot of ourselves. We saw lots and lots of terrible things that started to weigh on us. The work that we did impacted us and we absorbed a lot of that. What we saw in our own lives, in our own health and bodies, in our marriage were things that were hurt, that were wounded.

“It did take some emotional, spiritual, physical toll on us.”

While they were still wrapped up in that work though it was hard for them to see that damage. Only after being back home – Chris headed the North American office of Word Made Flesh from here – could they grasp just how much trauma they’d stuffed. There were the tragic figures at the Mother Teresa-founded House for the Dying, the maimed victims of the Blood Diamonds War, the Latina and Asian women recovering from being trafficked in the sex trade.

Phileena says the burden of it all came to a head for her one day.

“Back home a friend asked me after listening to what we had experienced, ‘Do you ever doubt the goodness of God?’ Immediately it was like a dam broke loose and the emotions took over and I just wept and wept and said, ‘Yes, I doubt the goodness of God.’ What I realize now is that in all my work social justice work up until that point I was operating in terms of finding someone to blame, someone who’s responsible for the state of the world and the suffering and injustice that is there.

“And certainly some of us are responsible and we need to take responsibility for our actions. But in Freetown, Sierra Leone everywhere I looked I found the person to blame was also victimized and so then I had nowhere to turn except to blame God for the state of the world and for the condition of my friends.

“I was in a crisis of faith.”

Just when things seemed bleakest a ray of hope shone through in the person of Father Thomas Keating, a Cistercian monk and priest who is a leading proponent of the Christian contemplative prayer movement.

“Keating came to Omaha to speak at Creighton University and he introduced us to the contemplative tradition and centering prayer,” says Phileena. “That was really a lifesaver for me. It was immediate grace. There was a way for me to just be with the terrible suffering and trauma of the world, the human brutality, the questions, the doubts. There’s a way for me to be with my anger towards God and my questions and doubts about my faith. There’s a way to live faith without having all the answers.

“The answers I grew up with in church in mid-America were not connecting with the real problems of the world. Keating was just so helpful in providing a way for me to stay connected to faith, to God in a way that would allow me to deepen and grow.”

It should be no surprise then that Keating, the author of several books and the founder of the St. Benedict’s monastery in Snowmass, Colo., where he resides and teaches, is a founding board member of Gravity.

Keating’s oft-professed lesson that a test of faith is an opportunity for growth resonated with the couple.

“Keating teaches that if we stay on the spiritual journey long enough we’ll come to the point where the practices that have sustained us in our faith journey fall short, they no longer nourish us, and when that happens it can be completely disorienting,” says Phileena, who went through this dark night of the soul herself. “A lot of people walk away from their faith at that point but Keating says it’s actually an invitation to go deeper.”

She and Chris chose to plunge the depths.

The contemplative way and paying it forward

“What we found is there’s a real difference between faith and certainty,” she says..”Faith is being able find yourself being held by something bigger and greater than you and not having all these answers. Doubt can be contained within our faith. Certainty is the opposite of faith. I think a lot of spiritual or religious people put a lot of bank in our certainty, but that’s actually a barrier to faith. Certainity can be a disguise for pride and superiority and thinking we have all the answers and have figured it all out and can figure God out. But faith is something that carries us. It’s a grace that helps us to be a part of the mystery of life and God and any goodness that is in us and that can flow through us to heal and transform the world.

“It really gave us an understanding for what we had witnessed in Mother Teresa and the Missionaries of Charity in South India. Mother never talked about this but we saw in her this pure model of contemplative activism, where people were dying at her doorstep and she was disciplined to see that they were taken care of but also to see that she and the Missionaries of Charity would take regular time out to meditate and pray. They had these regular rhythms of withdrawal and engagement and getting connected to a source that is greater than them.”

Reflecting on their own and others’ service experiences, Chris says he and Phillena concluded that many “folks in social justice actually take better care of someone else than they do themselves,” adding, “Where’s the integrity in that? If we don’t really know how to love ourselves how well can we really love someone else? We also saw folks who had really beautiful compelling vocations were sometimes being very unpleasant, grumpy people. We did see a lot of people burn out and a lot of people perpetually teetering on the edge of burn out.”

He says he and his wife resolved they and their fellow social justice workers “don’t have to do this at our expense, we don’t have to do this in a way that ends poorly for us or that ends with people walking away from their work, their faith, their beliefs, their community.” That’s where Gravity comes in. “The idea is we want to accompany or journey with folks in this formation of helping ground our social engagement in a deep contemplative spirituality.”

They’re guided in their new mission by the wisdom and example of figures as diverse as Keating, Father Richard Rohr and Thomas Merton, Mother Teresa, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Phileena says the monastic teachings of Keating, Rohr and Merton “have done a lot to bring contemplative spirituality out from the monastery and into the secular world. We’re a part of the next generation who are making it even more accessible and demystifying it. I think a big part of what we’re offering is accessibility to mysticism or contemplative spirituality. At the retreats the demystifying comes by practicing together and talking about our experiences.”

Gravity is a resource center whose programs, activities, books and videos help fulfill the mission statement tagline: “…do good better.” Both Chris and Phileena are published authors on matters of faith and spirituality.

The spiritual experiences that led them to Gravity, including all the insights gleaned from their teachers, colleagues, friends and role models, is their way of carrying the message.

Visit http://gravitycenter.com for a schedule of upcoming retreats and programs and links to materials.

Saving one kid at a time is Beto’s life work

He goes by Beto. Though middle-aged now Alberto “Beto” Gonzales can relate to the hard circumstances youths face at home and in the barrio because he faced difficulties at home and on the streets when he was their age. He knows what’s behind kids skipping school or getting in trouble at school because he did the same thing to cover his pain when he was a teen. He can talk straight to gang members because he ran with gangs back in the day. He knows what addiction looks and feels like because he’s a recovering addict himself. His work for the Chicano Awareness Center, the Boys and Girls Clubs of the Midlands, and other organizations has netted him many honors, including a recent Martin Luther King Jr. Legacy Award from Creighton University. Beto is a South Omaha legend for the dedication he shows to saving one kid at a time. My profile of him for El Perico tells something about the personal journey of transformation he followed to turn his life around to become a guiding light for others.

Here is a link to a more recent story I did about Beto-https://leoadambiga.com/category/alberto-beto-gonzales/

Saving one kid at a time is Beto’s life work

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in El Perico

Alberto “Beto” Gonzales believes working one-on-one with youths is the best way to reach them. His work as a mentor and gang prevention-intervention specialist has earned him much recognition, most recently the Martin Luther King Jr. Legacy Award from Creighton University.

Gonzales grew up in the South Omaha barrio he serves today as a Boys and Girls Clubs of the Midlands counselor. He does outreach with truants, many of whom come from dysfunctional homes. He knows their stories well. He grew up in a troubled home himself and acted out through gangs, alcohol and drugs. He skipped school. He only turned things around through faith and caring individuals.

“I was just an angry kid,” says Gonzales, who witnessed his father verbally abuse his mother. Betro’s internalized turmoil sometimes exploded.

“At 17 I almost went to prison for 30 years for assault and battery with the intent to commit murder. Then I got hooked on some real heavy drugs.”

“My mother prayed over me all the time and I think it’s her prayers that really helped me get out of this. I just decided to give my life to the Lord. ”

When he’d finally had enough he completed his education at South High at 20.

The Chicano Awareness Center changed his life’s course. A social worker there saw potential in him he didn’t see in himself. Then he was introduced to a nun, Sister Joyce Englert, who worked as a chemical dependency counselor.

“She heard me out,” he says. “I talked to her about my drug addiction, how I couldn’t keep a relationship and all kinds of crap going on. What’s cool about that is she asked me if I would go talk to kids about the dangers of drugs and alcohol even though she knew I was an abuser. She said, ‘I think it’s important kids hear your story.’ I found myself crying right along with the kids as I shared it.

“She told me I had a passion for this and asked what I thought about becoming a counselor. Well, I’ve done a lot crazy, dangerous things in my life but the most frightening and hardest thing was to tell the truth that I couldn’t read or write that well.”

Sister Joyce didn’t let him make excuses.

“With her help I got a chemical dependency associates degree from Metropolitan Community College, which led me into working in the schools with adolescents dealing with addiction issues, and I loved it, I just loved it.”

He also got sober. He has 33 years in recovery now.

Then he responded to a new challenge.

“When the gangs started surfacing I changed my career to working with gang kids,” he says. “That’s been my passion.”

He worked for the center until 2003, when he joined the Boys and Girls Clubs.

Having walked in the shoes of his clients, he commands respect. He uses his story of transformation to inspire.

“I had a faith my mother blessed me with, then I met a woman of faith in Sister Joyce who gave me my direction, and my job now is to give kids faith, to give them hope.”

He says it comes down to being there, whether attending court hearings, visiting probation officers, providing rides, helping out with money or just listening.

“It really takes a lot of consistency in staying on top of them. All that small stuff really means a lot to a kid who’s not getting it from the people that are supposed to be doing it for them, like mom and dad.

“Gangs ain’t never going to go away. The only thing we can do as a society is to find the monies to hire the people that can do the job of saving one life at a time. That’s what Jesus did. He then trained his disciples to go out and share his word, his knowledge, and they saved one life at a time. That’s all I’ve been doing, and I’ve lost some and I’ve won some.”

His job today doesn’t allow him to work the streets the way he used to with the hardcore kids.

“I’m not out there like I used to be.”

However, kids in his Noble Youth group are court-referred hard cases he gets to open up about the trauma, often abuse, they’ve endured. Talking about it is where change begins.

In a high burn-out field Gonzales is still at it, he says, because “I love what I do.” It hasn’t been easy. His first marriage ended over his job. Then tragedy struck home.

“There was a time in South Omaha when we were losing kids right and left and one of the kids killed was my cousin Rodolfo. It’s painful to see other people suffer but when it’s in your own family it’s a different story. Rodolfo was a good kid, I loved him, but he was deep in some stuff. When he got killed I lost it. That was a struggle. I told my employer, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ I took a sabbatical, I just had to get away. I did a lot of meditation and praying and it only made me stronger.”

He’s not wavered since.

“I’ve got my faith and I’ve learned you’ve got to hand everything over to God, Don’t try to handle it yourself because you will crumble.”

Related articles

- Drugs, gangs blamed for Okla. City homicide spike (sfgate.com)

- Child grows into woman before abuser is sentenced (omaha.com)

- Alleged gang leader arrested at Garfield High School (q13fox.com)

- Finding Her Voice: Tunette Powell Comes Out of the Dark and into the Spotlight (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Community trumps gang in Fr. Greg Boyle’s Homeboy model

Gang prevention-intervention efforts run the gamut. One that’s drawn lots of attention is Homeboy Industries, an East L.A. program founded and directed by Rev. Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest who has serious cred on the mean streets there for helping gangbangers find pathways to employability. I wrote this article in advance of a talk Boyle gave in Omaha a couple years ago. His experiences working with gang members and getting many to give up that life are told in his book, Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion.

Community trumps gang in Fr. Greg Boyle’s Homeboy model

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

The gang intervention efforts of a Jesuit priest in East Los Angeles have grown into Homeboy Industries, which provides mostly Latino participants work and life skills training, counseling and, most importantly, opportunity for hope.

The much profiled program has many communities, including Omaha, looking to its founder, Rev. Greg Boyle, for guidance in dealing with their own gang issues. Boyle, an acknowledged expert in the field, will be in Omaha Feb. 24 to discuss the successful therapeutic and employability approach his nonprofit takes and how it may be a model for Omaha.

From 1 to 4 p.m. at Creighton University‘s Harper Center Boyle will consult with community leaders engaged in gang intervention, prevention and workforce development efforts. At 5 p.m. he meets with Mayor Jim Suttle and Omaha City Council members. At 7 Boyle will deliver a public lecture and sign copies of his book, Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion, at Metropolitan Community College‘s South Omaha campus, in Room 120 of the Industrial Training Center, 27th and Q Streets.

Rev. Howard Dotson, pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church in Omaha, invited Boyle after hearing him speak last year in L.A., where Dotson also did gang intervention work. One thing Boyle says he’s learned from 20-plus years dealing with gang bangers is that “just like recovery in alcohol and drugs,” where “it takes what it takes to finally stop getting high,” it’s the same for gang members leaving The Life. “It can be the death of a friend, the birth of a son, a long stretch in prison. Like in recovery you don’t have to hit bottom, but maybe it will take that.”

He says gangs are not a crime issue but a community health issue like other social dilemmas (homelessness, addictions, prostitution).To address the complex problems gang members present he says Homeboy offers mental health services, along with employment opportunities, life coaching, “plus every imaginable curricular thing, from anger management to parenting — you name it, we have it.”

The program operates businesses that employ gang members, including a bakery, a cafe, a silkscreen shop, a merchandise store and a maintenance service. More than a job Boyle says Homeboy provides an avenue for “healing to take place.” Enemy gang members work side by side to break down barriers.

“Once they have a real palpable experience of community then it will shine light on the dark corners of gang life,” he says. “They realize how empty and hollow all that had been in the past. The community trumps gang.”

He says suspicion and animosity dwindle amid shared goals and cooperation.

“Their common interest is that they want to work. Before too long they become fast, wonderful friends. It’s one of those things you can actually take to the bank — it’s going to happen. They’re going to bond in a way they’ve never known in their family and they’ve never known in their gang certainly.”

Boyle says the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of Homeboy is why cities like Seattle and Wichita adopt some of its methods. Some observers credit Homeboy and community policing with helping dramatically reduce L.A.’s homicide rate.

“No nonprofit in L.A. County has a greater impact on the public safety than this place because we engage so many gang members,” says Boyle, who estimates “all 1,100 known gangs in the county have had somebody walk in here at some time or another.”

“I would say what makes us unique is this therapeutic model — attachment repair and a secure base is what we call it. We try to help people engage in their own healing so they can re-identify who they are in the world. Then they can go out in the world and the world will throw at them what it will but it won’t topple them because they’ve had this palpable experience of community and the chance to figure out who they are. It works.”

Dotson’s convinced Boyle and Homeboy have something to offer Omaha.

“To get jobs and to get rehabilitation for kids coming out of correction is the best way to stop the bullet.,” says Dotson. “You need to invest in these kids. If you give them a sense of hope and a sense of agency and some of that unconditional love many of them never got, then you reduce the gang problem.

“As church and community we have to meet people where they’re at and Fr. Greg and the people who support Homeboy understand that.”

South Omaha Boys and Girls Clubs gang prevention specialist Alberto Gonzales says the need for a Homeboy model here is greater than ever in light of recent cuts. Funding for anti-gang work he did in local schools has been eliminated. The Latino Center of the Midlands has disbanded its substance abuse counseling program.