Archive

Gray Matters: Ben and Freddie Gray fight the good fight helping young men and women find pathways to success

Omaha’s African-American community has some power couples in John and Viv Ewing; Willie and Yolanda Barney; Dick and Sharon Davis, among others, but the couple with the broadest reach may be Ben and Freddie Gray. He serves on the Omaha City Council. She’s president of the Omaha Public Schools Board of Education. That’s really having your fingers on the pulse of Omaha. Ben is someone I use as a source from time to time for stories I write about North Omaha and he is the subject of an extensive profile you’ll find on this blog. Freddie is someone I’ve just begun to know and I expect I’ll be interviewing and profiling her again before too long. They both have compelling stories and individually and collectively they are dynamic people making a difference wherever they serve and it just so happens their passions allign in boosting urban, inner city North Omaha through a variety of community, youth, and education initiatives.

Gray Matters: Ben and Freddie Gray Fight the Good Fight Helping Young Men and Women Find Pathways to Success

©by Leo Adam Biga

To appear in the August edition of the New Horizons

If you follow local news then you can’t help know the names Ben Gray and Freddie Gray. What you may not know is that they are married.

He’s instantly recognizable as a vocal Omaha City Councilman (District 2). He’s also a prominent player in the Empowerment Network, One Hundred Black Men and other community initiatives. He was a public figure long before that as a KETV photojournalist and the activist-advocate executive producer and host of the public affairs program Kaleidoscope, which weekly found him reeling against injustice.

Until recently his wife wasn’t nearly as well known, though in certain circles she was tabbed a rising star. She actually preceded Ben in public service when appointed to the Douglas County Board of Health. At the time she was office manager at NOVA, a mental health treatment facility. Along with Ben she co-chaired the African-American Achievement Council. She was also a paid administrator with the organization, which works closely with the Omaha Public Schools. It’s not the first time the couple worked in tandem. They have a video production business together, Project Impact. He produces-directs. She’s in charge of continuity.

She’s also worked as a strategic planning and management consultant.

Her longstanding interest in education led her to volunteer with the Omaha Schools Foundation and serve as a member of the student assignment plan accountability committee. The Grays were vocal proponents of the “one city, one school district” plan. Her public stature began to rise when she replaced Karen Shepard on the Omaha Public Schools Board of Education in 2008. She’s since become board president. The demands of the position leave little time for consulting work, which she misses, but she may have found her calling as a public servant leader.

“I like governance, I really do,” she says. “I have a strong feel for it.”

The size of responsibility she carries can be daunting.

“Sometimes I think about what a big job it is. The Omaha Public Schools district is one of the largest employers in the state and I’m the president of the board that’s in control of this entity. That’s kind of scary. I am not as confident as it comes across but I have a voice and I believe in using it for all these kids.”

Since assuming the presidency her public profile’s increased. In truth her private life was compromised as soon as she became Ben Gray’s wife in 1991. “It put me in the spotlight. There’s so many things that marrying somebody in the public eye does, and you don’t have a choice, you’re going to be public at that point.”

She suspects that sharing his notoriety has worked to her advantage. “There’s a lot of stuff Ben has afforded me the opportunity to do. Without him people wouldn’t know me from a can of paint and that’s probably how I would have lived my life and I would have been comfortable and OK with that.”

That each half of this pair holds a highly visible public service office makes them an Omaha power couple both inside and outside the African-American community.

Each represents hundreds of thousands of constituents and each deals with public scrutiny and pressure that gets turned up when controversy arises. That was the case last spring when he led the fight for the nondiscrimination ordinance the council eventually passed and Mayor Jim Suttle signed into law. In June Freddie found herself squarely in the media glare in the fallout of the scandal that erupted when sexually explicit emails OPS superintendent hire Nancy Sebring made came to light and she resigned under fire.

The couple makes sure to show their solidarity and support in crisis. Just as she turned out for city council hearings on the ordinance he attended the first school board meeting after the Sebring flap.

They act as sounding boards for each other when they feel they need to. “Sometimes we do,” he says, “but most of the time we don’t.” “If I want to bounce something off of him I can do that but I have my board members to do that with and he has his council members,” she says.

“If you’re married and you’re connected you know when it’s time to intervene and say let’s have a discussion about this,” he says. “Sometimes you just want to come home and veg out. The last thing you want is to talk about it. I don’t bring it home unless there’s a strategy, like when the Sebring thing happened we needed my expertise as a journalist, we needed legal counsel, we needed all of that, so that week was all about that.”

He’s proud of “how well she handled that situation, adding, “That was her defining moment.”

“A lot of times the conversation is after the fact,” she says, “because I can’t wait to talk to him to respond to the media when they’re in my face. I know if i need to I can reach out and he’s going to respond. The other thing is, we don’t always agree with each other. There’s been times when we’ve been able to change each other’s opinion or stand but not real often. But we don’t fight about it.”

The Grays have been making a difference in their individual and shared pursuits for some time now. The seeds planted during their respective journeys have borne fruit in the public-community service work they do, much of it centered around youth and education.

“We believe in children, I can tell you that, we believe strongly in children,” says Ben. Freddie calls it “a passion.”

Their work has earned them many awards.

They have seven adult children from previous marriages. They mentor more. By all accounts, they’ve made their blended family work.

“One of the things we did was we started having family dinners, and we started that before we got married,” says Freddie, “I still had one daughter at home with me. My older daughter was away from home. His children were still at home with their mom. Both of us were smart enough to figure out that with this new young person, let alone me, in the picture spending time with him that could be difficult. So we started having family dinner on Sunday and all seven of the kids would come. And we still do family dinner today.

“It was a wonderful way to bring our families together. And when people talk about a blended family, if you’ve ever done something like that and made it a tradition of your house for everyone to come together, it really and truly does blend them.”

Two of their kids live out-of-state now, as does one of their 11 grandchildren (they also have a great grandchild), but that still leaves a houseful.

“So generally on Sunday it’s a zoo time,” she says. “He loves it. He’s like they could all move back tomorrow. I’m the one that says no they cannot move back here and they have to go home now. They’re so close.”

Though born and reared in Cleveland, Ben’s made Omaha his home ever since the U.S. Air Force brought him here in the early 1970s. He’s built a life and career for himself and raised a family in his adopted hometown.

She’s an Omaha native but her father’s own Air Force career uprooted her and her six sisters for a time so that she did part of her growing up in Bermuda and in Calif. She returned in the early 1960s. The Omaha Central High School graduate raised a family here while working.

Whether in vote deliberations or media interviews each seems so poised and at home in this milieu of politics. As accomplished as they are today each comes from hard times far removed from these circumstances.

For example, the man Omahans know as Ben Gray is called by his street name “Butch” in his old stomping grounds of East Cleveland, where after suffering the loss of his working class parents at age 13 he fell into a life of organized crime. Numbers running, pimping, drug dealing. His extended family was well-entrenched in the black criminal underworld there. Its pull was something he avoided as long as his parents were alive but once gone he succumbed to a life that he’s sure would have ended badly.

Ben’s older sister Mary Thompson, whom he calls “my guardian angel,” and her husband took Ben and his younger brother Doug in and raised the boys right, modeling a fierce work ethic. But the call of the streets won out.

“The guys that I was dealing with, the guys that I knew, were real life gangsters. They do stories about these guys. Shondor Birns. Don King.

Before he was a fight promoter Don King used to run Cleveland. He ran all the drugs. And then he stomped a guy to death and when he went to prison his territory was split up, primarily between three different individuals and one of them was my uncle.”

Gray was arrested and sentenced to a youth incarceration center. After graduating a year late and near the bottom of his class he entered the military. His life’s never been the same since. “The Air Force changed who I was,” he says. “The military was my way out. Had I not joined I don’t think I would be alive. I was headed down a pretty dark path.” He graduated from aerial photography with honors. “People ask, ‘What was different?’ My response is always the same – discipline and expectations.”

That training is so ingrained, he says, “I’m disciplined about everything,” whether the self-pressed clothes he wears, the tidy home he keeps, the legislation he advances or the youth outreach he does.

“The intention of the military is to complete the mission and I complete the mission. When it came to the equal employment ordinance I had to complete the mission. When it came to the budget I had to complete the mission.”

He says leaving his old environment behind was the best thing he could have done.

“My sister readily tells folks all the time that while she hated to see me go she was in a lot of ways glad to see me go because she didn’t think I was going to make it if I stayed there.”

“That’s what she told me once,” says Freddie. “She said, ‘We’d thought he’d be dead or in jail.’ But they’re so proud of who he is today.”

When he goes back to visit relatives and friends, as he did with Freddie in July, he’s clearly a different person than the one who ran the streets as a youth but to them he’s still Butch. Oh, they see he’s transformed alright, but he’s Butch just the same.

“When we’re in Cleveland I immediately go back to referring to him as Butch,” says Freddie. “That’s what everybody knows him as. I don’t think anybody knows him as Ben.”

“It’s interesting when you leave a place and you come back to it,” he says, “because when I visited the corners I used to be at – even though a lot of the same people were still there – it wasn’t the same for me. They knew it and I knew it. A friend of mine told me, ‘This is not your place anymore,’ and he was right, it wasn’t. I didn’t fit.

“When I was doing the things I was doing I fit right in, as a matter of fact I ran the show for the most part.”

On a plane ride the couple made 20 years ago to spend Thanksgiving with his family in Cleveland Ben revealed his past for the first time to Freddie.

“I said, ‘Babe, when we get to Cleveland you’re going to hear some stories about me.'”

Then he asked her to marry him.

“Yeah, that plane ride was interesting,” she says, “and I still said yes.”

She has her own past.

Living in the South Omaha public housing projects called the Southside Terrace Garden Apartments, near the packinghouse kill floors her father worked after his military service ended, the future Mrs. Ben Gray grew up as Freddie Jean Stearns.

Life’s not always been a garden party for her. She got pregnant at age 17 and missed graduating with her senior class. She struggled as a young single mother before mentors helped her get her life together.

“It was not all a fairy tale life. The personal feeling of disappointment, not just letting my parents down but all those sisters behind me. That humbled me for a really long time.”

Long before marrying a celebrity and entering the public eye or serving on the school board, she quietly made young people her focus as a mother and mentor. She calls the young people under her wing “my babies.” Just as women helped guide her she does the same today.

She can identify with young single moms “who think their lives are over,” telling them, “I thought that was going to be it, that I was going to be on welfare for the rest of my life. I looked around at where I was, the projects, and I saw a lot of it around me. Mothers who had never been married. I was on public assistance for awhile and didn’t like that at all. I didn’t like the fact welfare workers could just come over my place and go through my stuff.”

She shares her experience of learning to listen to the right advice and to make better choices.

“I talk to these young women now, and I’m very open about it. I don’t preach.”

But she tries to do for them what women did for her. “I was blessed to have those women in my life. A number of them became my mentors. One of them was LaFern Williams. I’ll never forget her and Miss Alyce Wilson, the director of the Woodson Center in South Omaha. I spent so much time there. My big sister Lola Averett was another. There was a time when anything and everything she did I would do. She still models everything I could ever hope to do and to be.”

She says women like her sister, who worked at GOCA (Greater Omaha Community Action), along with Carolyn Green, Juanita James, Phyllis Evans, Sharon Davis and Beverly Wead Blackburn, among others, encouraged and inspired her. When Gray attended GOCA meetings she says she was at first too shy to speak up at but Lola and Co. helped her find her voice and confidence.

“They honestly would make me stand up and ask my question.”

“I’ve been very blessed in my life to have great female role models,” she says. “They took special care of me and others. They took care of the community, too. They made it safe. They protected and loved. These women touched a lot of lives.”

Those that survive continue fighting the good fight into their 70s and 80s. “They haven’t stopped. I wouldn’t even say they’ve slowed down.” She says when she sees them “you can bet your bottom dollar I’m in their ear saying, ‘I’m making you proud, I’m doing the right thing.'” It’s what Freddie’s babies do when they’re around her. All of it in the each-one-to-teach-one tradition.

“I’ve always had the passion for those who are behind me, young people. I just collect them, I don’t know what else to say. Anyone who really knows me knows that I talk about my babies. And they know who they are and they know what I expect from them. I can’t tell you how they’re selected, I don’t know how. But there is that group and they are my babies and I love them with all my heart.

‘I’ve told them, ‘My expectations are you’ve got to take care of Miss Freddie when she’s old.’ They laugh at that. But I need them to take care of me. They’re going to be my doctor, my mechanic, my attorney. And then they get it, they understand what I’m telling them. That they’re going to take care of me because I can’t do it forever. So they’re going to have to do these things, they’re going to need to be on the board of health, on the school board, work at NOVA. They need to take care of the world. They know that’s my expectation.”

She is a wise elder and revered Big Mama figure in their lives.

“When they see me they call me Mama Freddie or say, ‘How you doin’ Mama Freddie?'”

She recently lost one of her “babies.” When she got the news, she says, “it knocked me to my knees and I’m not talking figuratively. I was walking down the hall looking at Facebook on my phone when I saw it. I was very thankful Ben was here because I dropped to the floor. And then the phone started ringing and it was some of the other babies calling to check on me and me needing to check on them.”

Just as Freddie’s been a force in the lives of young people for a long time, so has Ben, who’s made at-risk youth his mission. As part of his long-time gang prevention and intervention work he even founded an organization, Impact One, that supports young people in continuing their education and becoming employable.

Because he’s been where they are, he feels he can reach young men and women whose lives are teetering on the edge of oblivion.

“It’s amazing how quickly you can spiral down into some really deep stuff if you let yourself, so I understand,” he says.”When people ask me why I do i deal with gang members it’s because I know ’em. I know how they think, I know what they think, I know most of ’em don’t want to do what they’re doing because I didn’t.

“But you get to a point after awhile where it becomes a lifestyle that makes it very difficult for you to get out of and the only choice you have sometimes, and the only choice I see for a lot of these young men, I hate to say this, is to leave here. I don’t like the brain drain. A lot of these people are really smart. But they’ve cast such a bad shadow that I don’t know how you stay here. I mean, I think there has to be some time between they’re leaving and coming back.”

He says something missing from today’s street dynamic is a kind of mentoring that used to unfold on the corner.

“At that time we had older guys that were able to talk to the younger guys.”

Kind of like what Ben does today.

“Someone might say, ‘Stop, don’t do that, that’s crazy.’ Or, ‘If this is what you’re going to do, here’s how you do it.’ Those kinds of things.

These young men don’t have that. A lot of them don’t. I’m talking about across the country. There’s nobody on that corner anymore who’s older who can tell them…”

“It used to be the young guys on the corner and the wise guys that went back to the corner gave people words of wisdom, and that’s gone,” says Freddie, who’s known her share of hard corners.

“That’s lost,” says Ben.

He says what’s missing from too many of today’s homes and schools in the inner city and elsewhere is the kind of discipline he got from his parents and sister and the military.

“I think most of us want it, we just don’t know we want it. Discipline is a method of working with people and molding people into what they should be as adults. That’s what it is. And that’s what my father tried to do for me in the brief time he was on this Earth.”

Gray sees a disconnect between some of today’s African-American youth and schools.

“I think what’s missing from majority minority schools is a pathway to get young people to know who they are. Our African-American students don’t know why they are. They don’t know the background. In the classroom they get a real strong dose of European history but they don’t get much about who they are.

“When there’s little or no discussion about you then how do you sit there and maintain an interest in being there?”

OPS has struggled closing the achievement gap between African-American students and nonblack students. Gray says before any real progress can be made “you’ve got to get them to stay there and keep them interested,” an allusion to the high truancy and drop-out rates among African-American students.

The problem has thus far defied attempted remedies.

He says, “In spite of efforts by the Empowerment Network, Building Bright Futures and others to address core problems like truancy and drop-outs in the (North Omaha) Village Zone we’re losing kids, they’re not staying in school. And they’re not staying in school because the influence of the street is such a strong influence. I know it. Those streets call you, man, and you can be in that classroom six hours a day but damnit you’ve got to go home and when you dog home you go to an environment that’s primarily unhealthy.

“So in spite of all we’ve done in that Village Zone we’re not winning.”

He doesn’t pretend to have the answers. He knows the problem is complex and requires multiple responses. But he does offer an illustration of one approach he thinks works.

“Teachers are constantly amazed I can address a school assembly and keep kids’ attention. Staff don’t get it. Freddie gets it. I talk about where the kids came from, I talk about who they are, I talk about what their history has been. They listen because they don’t (usually) hear that. That’s part of the missing piece of why they don’t stay. They don’t feel there’s anything there for them.”

He doesn’t claim miraculous results either.

“Any of us who are involved in this effort who talk to these kids know they’re not going to hear everything we say right away. They’re waiting to hear if we’re genuine. I tell them, ‘I’m not here to get all of you, I’m not here to convince any of you of anything. One of you is going to hear what I say, respond and react to what I say by becoming a leading citizen in this community. So I’m just here to get my one.’

“That’s when they start listening. They want to be the one.”

Flanked by Freddie Gray and Ben Gray, grieving parent Tabatha Manning at a press conference in the aftermatth of losing her 5-year-old child to gun violence.

Freddie appreciates better than most the challenge of educating children when so many factors bear on the results.

“We don’t produce widgets, we produce the citizens that are going to run this country. That’s exactly what we’re doing every single day. Every single one of these kids is an individual who deserves to have an individual touch them. It’s about that one-on-one relationship if we’re going to get kids to succeed, and if we don’t get this right then I think that says something about what the state of this country will be.

“Poverty is going to be the thing that kills us if we don’t take care of it and the only way I know to do that is to provide our children with the necessary skills to become employable.”

She’s keenly aware of criticism that the school board has ceded too much power to the superintendent.

“I understand people say that thing about the board being a rubber stamp but they don’t come and listen to the committee meetings and hear the board in dialogue. By the time theres a news sound bite we’ve already talked about it or figured it out or tabled it. Those things happen during the day (when the cameras aren’t on).

“But trust me we’ve got this. My job is to provide the superintendent with guidance in saying, ‘This is what you will do.’ There has to be parameters. We’ve got statutes to follow.”

In seeking solutions to bridge the achievement gap, she say, “I’m talking to other districts’ board presidents and members, not just when I’m on the Learning Community, but other times, too. That hasn’t happened much before.”

She says more collaboration is necessary because studies show that wherever kids live, whatever their race, if they live in poverty they underachieve.

“Poverty is a problem. If we’re not addressing poverty now than 20 years from now we’ll be having the same conversation.”

Breaking the cycle is a district goal.

“At the board level it’s looking at careers. We do kids a disservice when we say everybody’s going to college because that’s a lie and we all know it. But we do need to supply them with the necessary skill sets so they can be productive citizens.

“We’ve got to get these young people to the place where they can get jobs, where they can get out of poverty.”

She says OPS is finding success getting businesses to offer students internships that provide real life work experiences. He’s been active in the Empowerment Network’s Step-Up Omaha program to provide young people summer training and employment towards careers.

As both of them see it, everyone has a stake in this and a part to play, including schools, parents, business.

“There’s room at the table for everybody and everybody has to have a foot in this and has to step up. The focus has to be on what can we do together,” she says.

Now that she’s solidly in the public eye in such a prominent job she hopes African-American women follow her.

“I have to say this for other women who find themselves feeling like they’re voiceless: If you can see it, you can be it. There’s a lot of young African-American females who are just sharper than sharp, that could run rings around me all day doing this, but they don’t feel like they have a voice.

“And so I really hope they are paying attention because again Miss Freddie is not going to be doing this for the rest of her life and some of them are going to need to be sitting on this board.”

Ben Gray feels the same way about the young men and women of color he wants to see follow him into television or politics or wherever their passion lies.

Both with his own children and those he’s “adopted,” he’s taken great pains exposing them to African-American history and culture and encouraging them to engage in critical thinking and discussion.

“I wanted them to be more aware, I wanted all of our children to be aware of what’s around them and what it takes to survive. And to know who they are and what their history is, and some of them can tell you a lot better than I can tell you now.

“We have two that are like our own who are former gang members. Both of these guys are brilliant young men, and given a different set of circumstances would be someplace else.”

Ben and Freddie Gray are living proof what a difference new circumstances and second chances can make.

Related articles

- Masterful: Omaha Liberty Elementary School’s Luisa Palomo Displays a Talent for Teaching and Connecting (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Fast Times at Omaha’s Liberty Elementary: The Evolution of a School (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Exhibits on Display for the College World Series; In Bringing the Shows to Omaha the Great Plains Black History Museum Announces it’s Back (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kelly: It’s not about the ‘sex story,’ Freddie Gray says of Sebring (omaha.com)

- Brown v. Board of Education: Educate with an Even Hand and Carry a Big Stick (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

From the Archives: Veterans Cast Watchful Eye on the VA Medical Center

Very rarely do I write anything that even edges up on hard news. This story from 2000 is one of those exceptions. It had to do with complaints filed against the Omaha VA Medical Center and the watchdog role local veteran activists assumed in agitating for change and monitoring government responses and remedies. The Department of Veterans Affairs has a spotty even inglorious and sometimes infamous track record in attending to the medical needs of servicemen, past and present, and horror stories abound of poor conditions and treament experiences in veterans’ facilities. Of course, much good is done as well. But given that problems persisted before the last solid decade or more of returning combat vets requiring care the problems have, from I gather, only mutiplied in the crush of patients overwhelming the system.

From the Archives: Veterans Cast Watchful Eye on the VA Medical Center

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

A Call for Action

Last September saw the release of a long-awaited federal report stemming from an investigation by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Office of Inspector General into complaints about the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) program at the Omaha VA Medical Center. The investigation followed requests by Sen. Bob Kerrey, D-Neb., and Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, to examine complaints made to them, many in impassioned letters and phone calls, by veterans.

After the October 1999 investigation, nearly a year passed before the inspector general issued a 50-page report substantiating such concerns as insufficient staff, poorly coordinated services, long scheduling delays, inadequately administered drugs and a weak patient advocacy program. Other beefs, including allegations about negligent care, were not supported. Kerrey characterized the findings as showing “there are serious problems…inside an organization that is for the most part dedicated to high quality care.” The report made 16 recommendations for addressing the problems. Concurrent with the PTSD review the entire medical center was the subject of a routine comprehensive inspector general assessment, the timing of which may have been pushed up given the heat coming down from Washington, and its report surfaced more concerns and remedies amid overall good health care practices. In what was described as a coincidence, the center’s director and chief medical officer retired in June.

A hospital spokeswoman said the center has already implemented several changes and is on pace to complete others by target dates. Veterans who called for the initial study are pleased with some changes but assert old problems still persist. Todd Stubbendieck, legislative assistant in Kerrey’s Washington, D.C. office, said,

“Our understanding is everything is being implemented there. We’ve heard no additional patient complaints.”

Raising Hell

The reports, written in the cold, clinical language of bureaucratic Washington, mute the rage some veterans express at the insensitive and unresponsive manner in which they insist they’ve been treated. David Spry, vice president of the local chapter of the Vietnam Veterans of America, has become a mouthpiece and advocate for their discontent. His own experiences as a post traumatic stress disorder patient (in Lincoln), as a veterans legal custodial aide and as a past Veterans Advisory Committee member at the Omaha VA facility put him in a unique position to assess center practices and to glean feedback from the veterans community. Much of the discord has centered on a few key staff members and administrators and their perceived arrogance toward veterans. “They treated us with disrespect and that’s what a lot of the complaints are about,” Spry said. “It’s like, They’re the system, and we’re only veterans. What do we know? They thought we had no brain, no mouth, no nothing once we left their building, but we were comparing our notes about this place with other veterans groups.”

Spry turned veterans’ dissatisfaction into a cause that eventually got lawmakers and government oversight bodies to take action. For Spry, a Vietnam combat veteran, the process of getting officials to finally take seriously the red flags he and others originally raised more than three years ago has been an odyssey akin to battle. The role of whistle blower has taken its toll, too. “It hasn’t been easy. In 1997 we started to complain vigorously to VA management about this. We got nowhere. Our complaints never even got into the minutes of the meetings of the Veterans Advisory Committee. The things we were concerned about were problems we didn’t seem to be able to get corrected internally, so we went to a congressman,” he said, referring to former Rep. Jon Christensen (R-Neb.). Veterans aired grievances to Christensen and VA officials but, Spry said, little headway was made. “Then, when Christensen became a lame duck, we were kind of at a loss.”

Making the Case

That’s when, in 1998, Spry and fellow Vietnam Veterans of America service officers brought complaints, which grew in the wake of a national hospital accreditation survey, to the inspector general office, the Senate Subcommittee on Veterans Affairs and Kerrey. Spry said a year elapsed before Kerrey’s office took serious interest. Then, at the request of top Kerrey aides, Spry and his comrades were asked to gather veterans’ gripes and, once Kerrey saw the more than 100 letters of complaint, he asked the inspector general office to get involved. At the time, Kerrey said, “…this Vietnam Veterans post has made a persuasive case that something’s going on here that’s not good.” According to Spry, “This organization of ours really became quite passionate about this. We really pushed very hard. We had a lot of people looking into this and we finally got somebody to listen to us. It helped tip the scales when Sen. Kerrey came on board.”

Long before the inspector general weighed-in, the VA Medical Center followed-up its own internal program review by inviting the director of the VA system’s National Center for PTSD, Fred Gusman, to conduct an on-site assessment of the Omaha PTSD program in July 1999. Hospital spokeswoman Mary Velehradsky said, “We recognized we did have some systems problems as well as some patient care issues, and our inviting Mr. Gusman was a way to have another set of eyes look at that and to fix the problems and to make it a stronger program.”

Gusman’s findings of a “systemic problem” was confirmed by the inspector general, which included Gusman’s data in its report. He has made a follow-up visit to the hospital and, with inspector general staff, is overseeing program modifications.

A Thorn-in-the-Side

By the time the inspector general took a hard look at the Omaha facility, Spry said he was persona non grata with hospital officials. “I became a little too much of an irritant and they banned me from the facility except for medical treatment for my own service-connected disabilities. But that wasn’t good enough. They took away my freedom of speech, too. I am to have no contact with anyone or anyone with me. They’re doing anything they can to shut me up.” Veteran Tom Brady, who worked with Spry to document complaints about the center, said Spry has been singled-out: “Certainly, there are consequences to exposing practices that are subject to sanctions. He’s been one of the driving forces behind a lot of things and now they treat him like he’s a dangerous person.” Velehradsky confirmed the restrictions but added, “There are reasons people can be banned from a facility and I can guarantee you there was nothing connected to the IG (inspector general) incident.” She did not specify the reasons in this case.

As unofficial watchdogs, Spry and Brady chart the center’s progress in making changes. “We’re trying to monitor what’s going on, but we’re limited in going up there. From what we can tell, they have implemented a number of things that we’re really happy about. We’ve seen improvements in scheduling, in medications and in one-on-one therapy. We’ve seen a considerable difference in staff morale. The hospital is a lot happier.” But he and Brady remain critical of some program staff they feel lack expertise in working with PTSD patients. A psychologist whom the majority of complaints was filed against remains while a popular social worker has left. The two veterans also continue to be disenchanted with what they feel is the distant voice veterans have there. “We’re still not a cooperating partner — not because we don’t want to be,” Spry said.

According to Velehradsky the center has long had in place mechanisms for veterans to speak out with management and has recently increased these feedback avenues. She said the PTSD program has been strengthened with new procedures and the addition of specialized staff. She added recent patient surveys indicate high approval ratings and that veterans not wishing to be treated in the Omaha program have the option of being seen in a Lincoln clinic.

Standing Guard

It is perhaps inevitable disenfranchised veterans and entrenched VA Medical Center managers see things differently. Where Spry feels “it’s kind of a shame we had to go to this extent to push the bureaucracy around to get them to look at things,” Velehradsky said: “When you have an outside set of eyes look at your program and make recommendations it does make you stronger. We welcome it. It’s been very helpful and we continue to make improvements.”

While Kerrey has termed the VA episode a victory for veterans, the ever vigilant Spry remains wary and vows to carry on the fight if need be. His never-say-die attitude was formed as a Marine in Vietnam while under siege from overwhelming forces at Khe Sanh during the Tet Offensive in 1968. “I kind of made a commitment to myself and to the 1,500 of us who died at Khe Sanh that I don’t ever want to lose another battle again. And that’s why I’ve fought this (VA) thing. Have I been tenacious about this? I certainly have. All I want to do is make things better.”

Related articles

- Suicidal veterans may not be getting help they need (pri.org)

- Disabled vets increasingly cheated by fund managers (sfgate.com)

- Inspector General Report: VA Understates Delays In Handling Veterans’ Mental Health Claims (theveteransdisabilitylawfirm.com)

- Bill proposed to change PTSD military programs (thenewstribune.com)

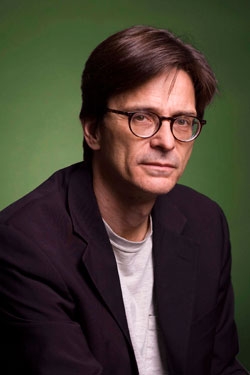

He knows it when he sees it: Journalist-social critic Robert Jensen finds patriarchy and white supremacy in porn

Robert Jensen is one of those writers who challenges preconceived ideas we all have about things we think we already have figured out. Among the many subjects he trains his keen intellect on are race, politics, misogny, and white supremacy and things really get interesting when he analyzes America’s and the world’s penchant for porn through the prism of those constructs. I interviewed him a couple years ago on these matters in advance of a talk he gave in Omaha, and the following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) is the result.

He knows it when he sees it: Journalist-social critic Robert Jensen finds patriarchy and white supremacy in porn

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Journalist-political activist-social critic Robert Jensen is the prickly conscience for a narcissistic Addict Nation that lusts after ever more. More resources. More power. More money. More toys. More sex. The tenured University of Texas at Austin associate professor organizes, agitates, reports, gives talks, writes. Oh, does he write.

He’s the prolific author of books-articles challenging the status quo of privileged white males, of which he’s one. He believes white patriarchal systems of power and predatory capitalism do injury to minorities through racist, sexist, often violent attitudes and actions. His critiques point out the injustice of a white male domination matrix that dehumanizes black men and objectifies-subordinates women.

We’re talking serious oppression here.

As an academic trained in critical thinking and radical feminism, his work rings with polemical fervor but refrains from wild rant or didactic manifesto. Agree or not, it’s hard not to admire his precise, well-reasoned arguments that persuasively connect the dots of an elite ruling class and its assumed supremacy.

He’s presenting the keynote address at a Sept. 22 Center for Human Diversity workshop in Omaha. His topic, “The Pornographic Mirror: Facing the Ugly Realities of Patriarchy and White Supremacy,” is one he often takes up in print and at the podium. His analysis, he said, is based on years studying the porn industry, whose misogynistic, racist products express “men’s contempt and hatred of women.”

Porn, he said, routinely depicts such stereotypes as “the hot-blooded Latina, the demure Asian geisha girl, the animalistic black woman and the hypersexualized black male.” Racially-charged code words — ebony, ivory, nubian, booty, jungle, ghetto, mama, chica, spicy, exotic — market these materials.

He said most interracial porn features black men having sex with white women, which he considers odd given that historically the majority culture’s posited black males as threats to the purity of white women. Why then would an “overwhelmingly white” audience want to view these portrayals?

Jensen suggests what’s at work is an “intensification” of “the core dynamic of male domination and female subordination.” Thus, he said, “by ‘forcing’ white women to have sex with black men, the ultimate sort of demonized man in this culture, it’s intensifying the misogyny and racism” behind it all. “That’s why I talk about these two things together, and why pornography is an important cultural phenomenon to study. It tells us something about the world we live in that is very important.”

The mainstreaming of porn as legitimate pop culture is a trend he finds disturbing. The industry, not counting the corollary sex trade, is estimated at $10 billion annually, comparable to other major entertainment industries such as television, film and sports. Jensen said his own students’ acceptance of porn as “just part of the cultural landscape” reflects a generational shift. Porn’s gone from taboo, scandalous, underground to casual lifestyle choice easily accessed via print, video, TV and the Web, where adult fare’s limitless and its content increasingly extreme.

Strip joints, adult book stores, chat lines, hook-up clubs, escort services, porn sites and X-rated channels abound. Sex tourism is a booming business in Third World Nations, where white men exploit women of color. Homemade porn is on the rise. Porn star Jenna Jameson owns cultural capital. Reality TV, cable programs, movies and advertising are, in his estimation, increasingly pornographic. Although careful not to link porn use to behavior, Jensen sees dangers. Sex addiction is a widely recognized disorder whose various forms have porn as a component.

Recreational choice or addictive fix, end point or gateway to overt, criminal acting- out, Jensen makes the case it’s all fodder for an already dysfunctional society.

“This is helping shape a culture which is increasingly cruel and degrading to women, which we should be concerned about,” he said. “If we’re honest with ourselves, even those who want to defend the pornography industry or who use pornography, I think we have to acknowledge the patterns we’re seeing are cause for concern. I can’t imagine how anyone could come to any other conclusion.”

He said it’s an open question how much more pornographers can push the limits before the culture says a collective, “Enough.” Any outcry’s not likely to come as a see-the-light epiphany, he said, but rather in the course of a long-term public education and public policy campaign. Anti-obscenity legal restraints, he said, are difficult now due to vague, weak state and federal laws, The exception is child porn, where strict laws are easily enforced, he said.

He opposes censorship, insisting, “I’m a strong advocate of the First Amendment and Free Speech,” adding current laws could be enforced with sufficient mandate.

“Much of the material were talking about clearly could be prosecuted yet it isn’t,” he said, “which I think reflects that level of cultural acceptance.”

He suggests enough male stakeholders consume, condone or profit from porn/illicit sex that this old boys network gives winking approval behind faux condemnation.

Jensen supports strict local ordinances and aggressive civil actions against adult porn similar to what feminists proposed in the ‘80s. He feels with modifications this approach, which failed legal challenges then, could prove a useful vehicle.

As Jensen notes, concurrent with this-anything-goes era of on-demand porn and sex-for-hire are the repressive strains of Puritanical America that discourage sex ed and open discussion of sex issues. He’d argue that silence on these subjects in a patriarchal, misogynistic society contributes to America’s high incidence of rape, sexual assault, prostitution, STDs, HIV/AIDS and teen pregnancy.

Overturning these trends, he said, begins with public critiques and forums. The Center for Diversity workshop at the Omaha Home for Boys is just such a forum. The 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. event features a wide-range of presenters on how to “Stay Alive” under the pervasive assault of sexism, racism, economic destabilization, domestic violence and pornography. The workshop’s recommended for health care professionals, therapists and social workers.

Check out Jensen’s work on the web site http://uts.cc.utexas.edu/-rjensen/index.html.

One Helluva Broad: Mary Galligan Cornett

I never met the late Mary Galligan Cornett during her long, legendary tenure as Omaha City Clerk, only when she’d been retired some years, but her reputation as a cantankerous, bigger-than-life personality preceded her and I was not disappointed when I finally did catch up with her. Sheds lost none of her bite or her blunt, blue-streak manner of speaking. She’s gone now but she’s definitely one of my most unforgettable characters. My profile of her appeared in the New Horizons in 2002.

One Helluva Broad: Mary Galligan Cornett

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horizons

For more than half-a-century, Mary Galligan Cornett gave as good as she got with the boys at City Hall.

In her colorful 53-year civil service career she saw hundreds of elected officials come and go. In a 1961 to 1997 reign as Omaha City Clerk she served 13 mayors (counting acting and interim chiefs) and dozens of council members. She saw Omaha transition from the commission form of government to the city charter home rule system to the present structure featuring district council elections. She was a stabilizing presence as Omaha endured scandals, bitter fights over equal rights and public works and abrupt changes in leadership. She helped Omaha retain its Triple AAA credit rating by selling bonds in New York’s financial district.

Along the way, she earned a reputation as a tough woman valued for the knowledge and history she brought to city business and as one not to be trifled with in the political wrangling game. This blunt, unadorned woman, who says of the wrinkles in her face — “I’ve earned every one” — is one helluva broad.

Unafraid to speak her mind and uncowed by the rough-and-tumble maneuvers of smoke-filled, back-room deliberating, Cornett was a trailblazer in the male fraternity called politics. For years, she was among only a handful of women city clerks in major U.S. metropolises. So, how did she survive under so many different regimes and surrounded by so many powerful men of often clashing politics and personalities? “Very simple, I became one of the good old boys. I made friends with their wives, their secretaries and their mistresses, and I got along just fine,” she said from her terraced antique and bric-a-brac-filled home on the busy Northwest Radial Highway. As former City Councilman Subby Anzaldo said, “Having Mary in a group of men was not uncomfortable. If a cross word flew out of someone’s mouth it wasn’t a situation where you had to worry about it. Mary understood and she could throw a few out herself if she had to. She was one of a kind. They don’t make ‘em like that anymore.”

At her home, family photographs are prominently displayed in the living room, where the pet dog and cat roam freely. Most pictures are of Cornett’s only child, Irene A. Cornett (Stranglin), now a 10-year veteran with the Omaha police force and the new mother of twin girls. Cornett raised Irene alone after the death of her husband, surety executive Bob Cornett, in 1976. Slowed by a broken hip suffered last March, she has a nurse tech, Raissa Franklin, help at home. About her patient, Franklin said jokingly, “She’s ornery. She’s worse than the agitator in the washing machine.” Ever the politician, the chain-smoking Cornett recently had pictures of herself taken sans cigarettes. After the photo session Cornett called out, “Raissa, honey, could you hand me a pack of cigarettes now that the photographer is gone?”

As far as being a woman in a man’s world, Cornett had only to look at the domineering women in her own life for role models.

Both of her grandmothers worked outside the home in addition to raising families. Her maternal grandma came from sturdy ranch stock and went on to become a music teacher in towns across Nebraska. Her paternal matriarch was a railroad brakeman as well as a seamstress. Her mother was a political operative and helped run the family produce business.

“I grew up with the idea a woman could be anything she wanted to be,” said Cornett. That’s why when she started working at City Hall as a building clerk in 1945 she chafed at the resistance she met from the all-male contractors who had to go through her to obtain permits. “Well, the men contractors had a hard time with that because they didn’t think a woman could look at a set of blueprints and figure out anything. It was a whole new thing for them. They had a hard time accepting it and I had a hard time accepting their chauvinism. My attitude was, ‘The hell with it. I’m here. I’m the one that issues the permits. Show me your (expletive) blueprints. Take me or leave me.’ I think I’ve always felt that way.”

Armed with her sharp tongue, astute mind and vast experience, she had the ear of mayors and council members. According to her successor, current City Clerk Buster Brown, whom she trained, “If she had something to say, people listened. Yes, she influenced decisions behind-the-scenes. She was an institution. She knew the ins-and-outs.” Rather than challenge her “strong personality,” he said, officials would “back away.” Former City Councilman Robert Cunningham said, “She handled things with authority. She was respected.” In her capacity as clerk and confidante, Cornett was the keeper of city records and secrets. She recalls how attorney Eddie Shaston, an associate of former Mayor A.V. Sorensen, “always said ‘I was the woman that knew and never talked.’”

Retired since 1997, Cornett is not telling tales out-of-school now, at least not on the record. If she did tell her story, the 77-year-old said she’d borrow the title from the Frank Sinatra anthem, “I Did It My Way.” The only trouble with that, she asked rhetorically, is “which of my lives would I be talking about? My private life? My political life? My life as a bondswoman?” To which Pat Wright, a friend and former assistant who popped over during a recent interview quipped, “Where does one stop and the other end? Sometimes you don’t even know,” which prompted Cornett to reply, “I know that.” Wright added, “Cornetts real. She tells it like it is.”

No doubt, Cornett thrived in the political arena because public service was, in a sense, a birthright by virtue of her family’s longtime involvement in the field. Her Irish-Scottish immigrant family’s political legacy extends back to the town’s wild-and-whooly beginnings to a pair of paternal grand uncles: former fire chief Jack J. Galligan and former police chief Michael Dempsey. Then there was her mother, Fairrie Irene Cameron Galligan, a wheel in the state and Midwest Democratic central committees. Mary often accompanied her to conventions, even meeting future president Harry S. Truman in Kansas City when he was still a ward leader for the Tom Pendergast machine. There was also a familial tie to the politically active Warners of Nebraska. “Everyone in my family, on both sides, was in politics,” Cornett said. “That’s been my whole life.”

Public service has been a passionate thing for the Cornett clan. “It was and it still is with me” she said. “My family at one time were all immigrants and this was the country that welcomed them. They felt they owed it something because of the freedom and the education and the employment they found here. And for all of that, there’s gotta be some payback. And, so, I think the whole family felt a personal responsibility to be part of government and to devote a lot of their lives to it. I devoted my entire life to it.” Politics also suited Cornett’s gregariousness. She said her capacity for getting along with people and putting aside personal differences for the public good is “an ability you have to have” to succeed in politics. Her skill at mixing with people from all walks of life and her hunger for being right in the thick of the action is why it all came naturally to her.

“I guess I’m a people person. I guess that’s why I picked this as my retirement house,” she said, referring to her residence. “It’s right on the street. Life goes on. There isn’t a time the rescue squad isn’t going that-a-way or a fire truck isn’t going this-a-way or a police car isn’t going another way. I can lay in bed and tell from the traffic what time it is.”

Cornett likes the neighborhood and its mix of young families and retirees. “I lived for many years in a big home at 61st and Decatur and I hated it. Everybody went to bed at like 8:30 or 9, and being a night owl, I’d be up till 1 or 2 in the morning. Also, I cannot imagine living in one of these retirement places where everybody’s old, where there’s no children, where there’s no dogs or cats. Why would you want to shut yourself off from the world? You’ve got to have some life going on around you,” she said above the din of rushing traffic and barking dogs outside.

For her, city government was where the action was. How apt then that this lifelong devotee of Italian grand opera found herself immersed in the drama and machinations of big city politics, with all its brokering, backstabbing and symbolic bloodletting. Because politics truly is in her blood, she still keeps close tabs on City Hall. Asked if leaders still come to her for counsel, she answered, “Let’s put it this way, I get a lot of telephone calls. I still have an excellent grapevine together. Remember, it’s been 53 years or so building it. I can tell you what’s going on in every (expletive) department down there. I keep track of things.”

After years directing the clerk’s office, which besides keeping records supports the functions and enforces the rules of the City Council, she has a rather proprietary feeling about that august body. The last council she worked with had a contentious relationship with former Mayor Hal Daub, whom she felt was not well served by some members, which makes her glad the present council, with its five new faces, is working so well with Mayor Mike Fahey. “I’m very proud of the new council. I think they’re doing a very good job. This council and the mayor are communicating. I think that’s a necessary part of good government. You can disagree, but you need to communicate at least your disagreements.”

In Cornett’s view the previous council “made life miserable for Mayor Daub,” adding: “I always felt very sorry for Daub. Did he make mistakes? Yes. Could he have maybe communicated with two or three of them better? Yes. But there were four of ‘em on that council that no matter what he would have done they would never have moved off what they wanted. And it wasn’t a matter of what was best for the city or what was good for the taxpayer. It was a matter of their own personal egos and their desire to stay in power. Well, you know what happened to most of ‘em? They were beaten out in the last election.”

In past administrations Cornett became a liaison or conduit between mayors and councils locked in stalemates. “When some mayors were not talking to certain council members they used me as a go-between,” she said. “They about wore my voice out, too.” She also frequently sat in on cabinet meetings.

One of Cornett’s closest cronies in city government was the late Herb Fitle, the longtime city attorney with whom she enjoyed a salty relationship that sometimes found them feuding. As years passed, Cornett and Fitle, along with officials George Ireland and S.P. Benson, became the wise old sages in city government. Cornett and Fitle were “the staunchest supporters and absolute protectors” of the city charter that came into effect in the late-1950s.

“We had a long, long tenure together,” she said. “If we stood together, all hell and high heaven could not have moved us — I don’t care if it was mayors, councils, outside influences, whatever. But our disagreements also were legend. He’d write his opinions and although I wasn’t an attorney I sometimes wouldn’t agree with his opinion and I wasn’t very amiss to tell him so.

“Once, we disagreed over some political or legal issue and we stopped talking to each other. I’d send my assistants up to his office for answers and he’d send his attorneys down to my office for answers. Well, the help got tired of that and came to me and said, ‘Look, you guys have got to stop this. We can’t take it anymore.’ I said, ‘OK, fine.’ It was near Christmas and we used to have this event called The Christmas Sing where we all gathered in the council chambers with an orchestra to sing carols, and so I asked someone to get peace doves. While this program was going on I said to Herb, ‘I think we should make up,’ and I let the birds go. They were scared as hell and flew all over the place. Well, it turned out they were pigeons and, you know, they pooped on everybody and everything…the musicians, the councilmen, the chairs, the desks. I think it took the night help two or three hours to clean up.”

Despite the mess, her goodwill gesture was accepted and The Great Cornett-Fitle feud ceased.

In her watchdog role with the council Cornett provided oversight to ensure proceedings followed protocol. She served as sergeant of arms, called roll, recorded results and supplied information requested by councilmen on resolutions, ordinances, liquor licenses, etc.. The job also involved training new council members in how municipal government operates. Not everyone comes prepared to govern. “You get newly elected officials that never saw a charter before,” she said. Former councilman Subby Anzaldo said her influence was felt. “She had input. We came to her for answers. She told it like it was. She was like the eighth council member.”

She provided continuity when, in 1981, the move from at-large to district elections brought seven new council members and a new mayor into office and then, in the late 1980s-early 1990s, when Omaha went through six mayors due to recall, death, defeat, election, resignation. At times like those, City Clerk Buster Brown said, “She was very vital to making sure city government ran smoothly.” The way she sees it, she helped by “just being there.”

Then there’s the delicate matter of sorting out potential conflicts of interest. As Cornett explained, “Everybody comes to government bringing their own baggage in terms of outside influences. There may be something in the charter that can favor an official in getting a contract” or a business advantage. “Will officials try to use their influence? Of course they will. In my downstairs office at home I have reams of settled rulings on certain sections of the charter where somebody tried to do something they couldn’t (legally) do.”

At the countless council meetings she oversaw, she heard everything from dissident voices to impassioned pleas to whimpers to cheers. Among those she had removed from the premises was a deputy sheriff who arrived with a warrant during a council session. When she informed the deputy it was not permissible to serve a sitting body but that he would instead have to wait until the meeting ended, he persisted, whereupon she called security, ordering police to “remove this man,” which they did, much to the deputy’s chagrin. Cornett said she was so upset that someone was “obstructing or interrupting MY council meeting” she never even “bothered to find out” who or what the warrant specified.

Another time, during the racially tense 1960s, Cornett recalls how marching civil rights demonstrators descending upon City Hall sent most officials scurrying for cover. Typical of Cornett, she stood her ground. As it turned out, the group included a large contingent of church-based elders whose intent was conciliatory. “With all the public officials having taken to the hills, I was the only one left, so the marchers came to my office. I called the switchboard and told them I didn’t want any calls and I told my staff to give these elderly ladies the cushions off their chairs to kneel on. That’s how I came to have a pray-in in my office.”

For the most part, however, Cornett plied her political savvy not in public view but behind-the-scenes. Of the many mayors she worked with, she said, “Almost every one of ‘em really cared about this city. I loved every one of ‘em, whether I fought with ‘em or not and whether they disliked me or not. Different mayors at different times had difficult personalities. I wouldn’t say who were my favorites, but I would say who taught me the most — A.V. Sorensen (1965-69). He made it a point to teach me…government, finances, investments, organization, management. He expected everything to be organized. He hated a messy desk.”

She said Sorensen was a model of efficiency who demanded subordinates follow suit. “If you couldn’t give him an answer in 5 minutes…forget it.” She recalls how when she and former City Council President Art Bradley questioned why he gave “both of us directives” to hunt up the same data, his honor replied — “‘Because you come back with different answers, and half way between the two of them is the truth.’ That was A.V.”

Sorensen restored faith in Omaha’s elected leadership in the wake of corruption at City Hall. His predecessor, the dashing young Jim Dworak (1961-65) was indicted but later acquitted on bribery and conspiracy charges involving rigged real estate zoning laws. Other city officials were convicted. While Cornett is convinced Dworak did not accept any bribes, she believes he was a victim of his own fast-living ways. “Wine, women and song were his problems. He just had too much too soon.”

Where Dworak was a free-wheeling playboy, Sorensen was a circumspect elder statesman. Tough facade aside, Cornett maintained a soft spot for old A.V. “I felt so close to him. He was one of the few people who hurt my feelings. He had been out of office a few months when he came to visit me. My office, for some reason, was all cluttered up. He didn’t say Hello or How are you? — no, he said, ‘I thought I taught you better than that,’ and walked out. Well, I sat there and cried.”

Another mayor whom Cornett says “taught me a great deal” was brash Hal Daub (1993-2001). She feels his greatest strength — a facile mind — often proved his undoing when combined with his impatience. “Hal is an extremely brilliant man,” she said. “He has almost a complete retentive memory for facts and figures. But he thinks so fast that he’s always jumping the gun on people.” The two respected each other enough that mere weeks after retiring from the clerk’ s office she accepted his request to assume an eight-month job researching issues related to city-county government merger, a subject she calls “near and dear to my heart.”

Over the years Cornett said she rejected notions of running for public office and spurned opportunities to enter the private sector. Life as an elected official held no interest, she said, because she “didn’t want to play the game” and disliked the idea of being beholden to “outside influences.” Besides, she added, elected officials don’t have the real control — civil service administrators do. The prospect of leaving City Hall altogether was equally unimaginable.

“I was offered two or three very good jobs paying twice what I made in city government, but I decided, no, that’s where I belonged.” It’s why she looked forward going to work every day and thought nothing of putting in overtime even though her post didn’t qualify her for extra pay.

“This sounds kind of corny, but I always felt the Lord put me in the right spot at the right time in my life,” she said. “Every day there were new problems. Every day there was something else. You never knew when you got there in the morning what was going to transpire. And, so, if you wanted an interesting life you couldn’t have had a better job. I loved every minute and I kept going as long as I could.”

Related articles

- Steve Rosenblatt, A Legacy of Community Service, Political Ambition and Baseball Adoration (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Ashford to run for Omaha mayor (omaha.com)

- Kelly: It’s not about the ‘sex story,’ Freddie Gray says of Sebring (omaha.com)

Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them

African-Americans from the town where I live, Omaha, Neb., are often amused when they travel outside the state, especially to the coasts, and people they first meet discover where they are from and invariably express surprise that black people live in this Great Plains state. Yes, black people do live here, thank you very much. They have for as long as Nebraska’s been a state and Omaha’s been a city, and their presence extends back even before that, to when Nebraska was a territory and Omaha a settlement. Much more, some famous black Americans hail from here, including musicians Wynonie Harris, Buddy Miles, Preston Love Sr. and Laura Love, Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson, Hall of Fame running back Gale Sayers, Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers, the NFL’s first black quarterback Marlin Briscoe, actress Gabrielle Union, actor John Beasley, producer Monty Ross, Radio One-TV One magnate Cathy Hughes, and, wrap your mind around this one, Malcolm X. That’s right, one of the most controversial figures of the 20th century is from this placid, arch conservative and, yes, overwhelmingly white Midwestern city. He was a small child when his family moved away but the circumstances that propelled them to leave here inform the story of his experience with intolerance and bigotry and help explain his eventual path to enlightenment and civic engagement in the fight to resist inequality and injustice. Though the man who was born Malcolm Little and remade himself as Malcolm X had little to do with his birthplace after leaving here and going on to become a national and international presence because of his writings, speeches, and philosophies, some in Omaha have naturally made an effort to claim him as our own and to perpetuate his legacy and teachings. Much of that commemorative and educational effort is centered in the work of the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation based at the North Omaha birthsite of the slain civil rights activist. The following story, soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com), gives an overview of the Foundation and recent progress it’s made. Rowena Moore of Omaha had a dream to honor Malcolm X and she led the way acquiring and securing the birthsite and ensuring it was granted historic status. After her death a number of elders maintained what she established. Under Sharif Liwaru’s dynamic leadership the last eight years or so the organization has made serious strides in plugging MXMF into the mainstream and despite much more work to be done and money to be raised my guess is that it will someday realize its grand plans, and perhaps sooner than we think.

Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Self-determination by any means necessary.

The notorious sentiment is by Malcolm X, whose incongruous beginnings were in this conservative, white-bread city. Not where you’d expect a revolutionary to originate. Then again, his narrative would be incomplete if he didn’t come from oppression.

Born Malcolm Little, his family escaped persecution here when he was a child. His incendiary intellect and enlightenment were forged on a transformative path from hustler to Muslim to militant to husband, father and humanist black power leader.

As it does annually, the Omaha-based Malcolm X Memorial Foundation commemorates his birthday May 17-19. Thursday features a special Verbal Gumbo spoken word open mic at 7 p.m. hosted by Felicia Webster and Michelle Troxclair at the House of Loom.

Things then move to the Malcolm X Center and birthsite. Friday presents by the acclaimed spoken word artist and author Basheer Jones, plus The Wordsmiths, at 7 p.m.

On Saturday the African Renaissance Festival unfolds noon to 5 p.m. with drummers, native attire, storytelling, face painting and Malcolm X reflections. Artifacts from the recently discovered Malcolm “Shorty” Jarvis collection of Malcolm X materials will be displayed. The late musician was a friend and criminal partner of Malcolm Little’s before the latter’s incarceration and conversion to Islam.

It’s a full weekend but hardly the kind of community-wide celebration, much less holiday, devoted to Martin Luther King Jr.

“I tell people, you may still not like Malcolm X, you may have a problem with a revolutionary. Martin was a revolutionary and maybe you came to love him. But I do want you to know brother Malcolm’s whole story and where he came from,” says MXMF president Sharif Liwaru.

“A big portion of what we do is about the legacy of Malcolm X. We go into communities, schools and other speaking environments and we educate people about Malcolm X, what he meant, what his impact was on society. Sometimes people walk away with a different level of respect for him. Sometimes they walk away having a better understanding.”

Using the tenets of Malcolm X, the foundation promotes civic engagement as a means foster social justice.

Nearly a half-century since Malcolm X’s 1965 assassination, he remains controversial. The Nebraska State Historical Society Commission has denied adding him to the Nebraska Hall of Fame despite petition campaigns nominating him. Few schools have curricula about the slain civil rights activist.

From its 1971 start MXMF has struggled overcoming the rhetoric around its namesake. The late activist Rowena Moore founded the grassroots nonprofit as a labor of love. She secured the North O lot where the razed Little home stood and where she once lived. Fueled by her dream to build a cultural-community center, MXMF acquired property around the birthplace. The site totals some 11 acres.

By the time she passed in 1998 the piecemeal effort had little to show save for a state historical marker. Later, a parking lot, walkway and plaza were added. Other than clearing the land of overgrowth and debris, the property was long on promise and short on fruition, awaiting funds to catch up with vision.

Without a building of its own, MXMF events were held alfresco on-site from spring through fall and at rotating venues in the winter. “We felt a little homeless,” says Liwaru. “We were very creative and did a whole lot without a building but we didn’t have a place to showcase and share that.” All those years of making do and staying the course have begun paying off. Hundreds of thousands of dollars in public-private grant monies have been awarded MXMF since 2009. Other support’s come from the Douglas County Visitors Improvement Fund, the Iowa West Foundation, the Sherwood Foundation, the Nebraska Arts Council and the Nebraska Humanities Council.

Most notably a $200,000 North Omaha Historical grant allowed MXMF to acquire its first permanent indoor facility, an adjacent former Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall at 3463 Evans Street, in 2010. Now renamed the Malcolm X Center, it hosts everything from lectures, films, plays, community forums, receptions and fundraisers to a weekly Zumba class to a twice monthly social-cultural-history class. Annual Juneteenth and Kwanzaa celebrations occur there.

Most notably a $200,000 North Omaha Historical grant allowed MXMF to acquire its first permanent indoor facility, an adjacent former Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall at 3463 Evans Street, in 2010. Now renamed the Malcolm X Center, it hosts everything from lectures, films, plays, community forums, receptions and fundraisers to a weekly Zumba class to a twice monthly social-cultural-history class. Annual Juneteenth and Kwanzaa celebrations occur there.MXMF conducts some longstanding programs, including Camp Akili, a residential summer leadership program for youth ages 14-19, and Harambee African Cultural Organization, an outreach initiative for citizens returning to society from prison.

The center is a community gathering spot and bridge to the wider community. Liwaru says it gives the birth site a “public face” and “front door” it lacked before, thus attracting more visitors. Besides hosting MXMF activities the center’s also used by outside groups. For example, Bannister’s Leadership Academy classes and Sudanese cultural events are held there.

“We’re very proud to be a community resource. It legitimizes us as an organization to have that space available. It makes a difference with the confidence of the volunteers involved.””

A recent site development that’s proved popular is the Shabazz Community Garden, where a summer garden youth program operates.

The surge of support is not by accident. The birthsite’s pegged as an anchor-magnet in North Omaha Revitalization Village plans and Liwaru says, “We definitely see ourselves as a viable part of it.” North Omaha Development Project director Ed Cochran, Douglas County Commissioner Chris Rodgers and Omaha City Councilman Ben Gray have helped steer resources its way.

Attitudes about Malcolm X have softened to the point even the prestigious Omaha Community Foundation awarded a $20,000 capacity building grant. Despite working on the margins, Liwaru says “investors could see our mission and work ethic and they supported that.”

Since obtaining its own facility, Liwaru says, “I find more people speaking as if our long-range plans are possible.” Those plans call for an amphitheater and a combined conference-cultural center.

For most of its life MXMF’s subsisted on small donations. When the building grant stipulated $50,000 in matching funds, says Liwaru, “”it was really the culmination of a lot of little gifts that made it happen.”

The all-volunteer organization depends on contributions of time, talent and treasure from rank-and-file supporters.

“We believe a little bit of money from a lot of people is beneficial,” says Liwaru. “Sometimes that meant we were probably working harder than the next organization that may be able to go to one or two people to get their funds, but it certainly makes us accountable to more people. We’re ultimately responsible to our community because we have so many community members contribute.

“Our organization belongs to the community. The people get the say.”

In tangible, brick-and-mortar terms, the foundation hasn’t come far in 40 years, but all things considered Liwaru’s pleased where it’s at.

“We’ve made a lot of progress. One of the things that makes me confident we’ve turned this corner is there’s still this strong commitment, there’s still passionate people involved.”

Veteran board members and community elders Marshall Taylor and Charles Parks Jr., among others, have carried the torch for decades. “They bring experience and wisdom,” says Liwaru. He adds, “We’ve added strong young people to our board like Kevin Lytle (aka Self Expression), and Lizabet Arellano, who bring a lot of new ideas and a passion for carrying out change in this urban environment.”

However, if MXMF is to become a major attraction a giant leap forward is necessary and Liwaru’s unsure if the support’s there right now.

“Everybody wants sustainability in terms of stable funding and revenue. We put out a lot of funding proposals at the end of last year. Few were approved. We got a lot of nos. Most funders don’t say why. We don’t know if it’s because they’re not wanting to be affiliated with Malcolm X or if it’s not understanding what we do as an organization or if they don’t think we can see projects through to the end.”

He can’t imagine it’s the latter, saying, “Anybody who knows us knows we’re persistent and that what we talk we follow through with.”

His gut tells him the organization still encounters patriarchal, political barriers.

“We always feel we have to come in proving ourselves. I always come in and explain we’re not a terrorist organization or a splinter cell. Most of what we get is a lot of encouragement but it’s a pat on the back and ‘I hope that you guys do really well with that’ versus, ‘I can help.’ I think one of the challenging things is we’re not sure what people think of us. There are many who aren’t sure which Malcolm we’re celebrating.

“If an organization is just completely not interested in covering anything related to Malcolm X it’d be nice to know. So the question from me to philanthropists out there is, ‘What do you think about the Malcolm X foundation and what we do? Do you see it as a worthy cause? What are we missing?”

Answers are important as MXMF is S100,000 away from finishing its planning phase and millions away from realizing the site’s full build-out. It could all take years. None of this seems to discourage MXMF stalwarts.

“We are willing to sacrifice and work diligently for however long it takes,” says Lizabet Arellano. Fellow young blood board member Kevin Lytle takes hope from the momentum he sees. “There’s more and more people at events and rallies and different things we do. People are finally starting to recognize and take pride in the fact Malcolm X was born here,” he says. “We have to start somewhere, and that’s a start. People know that we’re here and that we’re representing something beneficial to the community.”

Liwaru sees a future when major donors ouside Nebraska help the MXMF site grow into a regional, national, even international mecca for anyone interested in Malcolm X.

Besides a House of Loom cover charge, the weekend MXMF events are free. For details, visit http://www.malcolmxfoundation.org or the foundation’s Facebook page.

Related articles

- A Brief History of Omaha’s Civil Rights Struggle Distilled in Black and White By Photographer Rudy Smith (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Malcolm X bio doubts activist was served justice (cbsnews.com)

- Malcolm X artifacts unearthed: Police docs and more found among belongs of ‘Shorty’ Jarvis (thegrio.com)

- Blacks of Distinction II (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)