Archive

UPDATE TO: Marlin Briscoe finally getting his due

UPDATE: I was fortunate enough to attend the Thursday, Sept. 22 An Evening with the Magician event honoring Marlin Briscoe. It was a splendid affair. Omaha’s Black Sports Legends are out in force this week in a way that hasn’t been seen in years, if ever. A Who’s-Who was present for the Magician event at Baxter Arena. They’re back out at Baxter on Sept. 23 for the unveiling of a life-size statue of Marlin. And they’re together again before the kickoff of Omaha South High football game at Collin Field. Marlin is a proud UNO and South High alum. This rare gathering of luminaries is newsworthy and historic enough that it made the front page of the Omaha World-Herald.

It’s too bad that the late Bob Boozer, Fred Hare and Dwaine Dillard couldn’t be a part of the festivities. The same for Don Benning, who now resides in a Memory Care Center. But they were all there in spirit and in the case of Benning, who was a mentor of Marlin Briscoe’s, his son Damon Benning represented as the emcee for the Evening with The Magician event.

So much is happening this fall for Marlin Briscoe, who is finally getting his due. There is his induction in the high school and college football halls of fame. John Beasley, who was a teammate of Marlin’s, is producing a major motion picture, “The Magician,” about his life. This week’s love fest for Briscoe has seen so many of his contemporaries come out to honor him, including Bob Gibson, Gale Sayers, Roger Sayers, Ron Boone and Johnny Rodgers. Many athletes who came after Marlin and his generation are also showing their love and respect. Having all these sports greats in the same room together on Thursday night was a powerful reminder of what an extraordinary collection of athletic greats came out of this city in a short time span. Many of these living legends came out of the same neighborhood, even the same public housing project. They came up together, competed with and against each other, and influenced each other. They were part of a tight-knit community whose parents, grandparents, neighbors, entrepreneurs, teachers, rec center staffers and coaches all took a hand in nurturing, mentoring and molding these men into successful student-athletes and citizens. It’s a great story and it’s one I’ve told in a series called Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Omaha’s Black Sports Legends, I plan to turn the series into a book.

Check out the stories at–

https://leoadambiga.com/out-to-win-the-roots-of-greatness-…/

Marlin Briscoe finally getting his due

©by Leo Adam Biga

In the afterglow of the recent Rio Summer Olympics, I got to thinking about the athletic lineage of my home state, Nebraska. The Cornhusker state has produced its share of Olympic athletes. But my focus here is not on Olympians from Nebraska, rather on history making athletic figures from the state whose actions transcended their sport. One figure in particular being honored this week in his hometown of Omaha – Marlin Briscoe – shines above all of the rest of his Nebraska contemporaries.

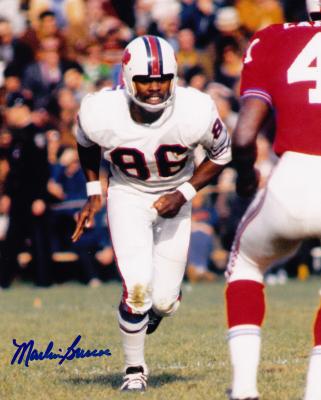

Briscoe not only made history with the Denver Broncos as the first black starting quarterback in the NFL, he made one of the most dramatic transitions in league history when he converted from QB to wide receiver to become all-Pro with the Buffalo Bills. He later became a contributing wideout on back to back Super Bowl-winning teams in Miami. He also made history in the courtroom as a complainant in a suit he and other players brought against then-NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle. The suit accused the league of illegal trust activities that infringed on players’ pursuit of fair market opportunities. When a judge ruled against the NFL, Briscoe and his fellow players in the suit won a settlement and the decision opened up the NFL free-agency market and the subsequent escalation in player salaries.

The legacy of Briscoe as a pioneer who broke the color barrier at quarterback has only recently been celebrated. His story took on even more dramatic import upon the publication of his autobiography, which detailed the serious drug addiction he developed after his NFL career ended and his long road back to recovery. Briscoe has devoted his latter years to serving youth and inspirational speaking. Many honors have come his way, including selection for induction in the high school and college football halls of fame. He has also been the subject of several major feature stories and national documentaries. His life story is being told in a new feature-length film starting production in the spring of 2017.

You can read my collection of stories about Briscoe and other Omaha’s Black Sports Legends at–

OUT TO WIN – THE ROOTS OF GREATNESS: OMAHA’S BLACK SPORTS LEGENDS

Briscoe’s tale is one of many great stories about Nebraska-born athletes. Considering what a small population state it is, Nebraska has given the world an overabundance of great athletes and some great coaches. too, The most high-achieving of these individuals are inducted in national sports halls of fame. Some made history for their competitive exploits on the field or court.

Golfer Johnny Goodman defeated living legend Bobby Jones in match play competition and became the last amateur to win the U.S. Open. Gridiron greats Nile Kinnick, Johnny Rodgers and Eric Crouch won college football’s most prestigious award – the Heisman Trophy. Pitcher Bob Gibson posted the lowest ERA for a season in the modern era of Major League Baseball. Bob Boozer won both an Olympic gold medal and an NBA championship ring. Ron Boone earned the distinction of “Iron Man” by setting the consecutive games played record in professional basketball. Gale Sayers became the youngest player ever inducted in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Rulon Gardner defeated three-time Olympic gold medalist Alexander Karelin in the 2000 Sydney Games to record one of the greatest upsets in Games history.

Terence Crawford has won two world prizefighting titles and in the process single-handedly resurrected the sport of boxing in his hometown of Omaha, where he’s made three title defenses before overflow crowds. He also has a gym in the heart of the inner city he grew up in that serves as a sanctuary for youth and young adults from the mean streets.

Some Nebraskans have made history both for what they did athletically and for what the did away from the field of competition. For example, Marion Hudson integrated Dana College in the early 1950s in addition to being a multi-sport star whose school records in track and field and football still stood on the books decades when the college closed in 2010. Tom Osborne became the first person to be named both the high school and college state athlete of the year in Nebraska. He played three seasons in the NFL before becoming the top assistant to Bob Devaney at the University of Nebraska, where he succeeded Devaney and went to a College Football Hall of Fame coaching career that saw his teams win 250 games and three national titles. After leaving coaching he served as an elected U.S. House of Representatives member. The Teammates mentoring program he established decades ago continues today.

There are many more stories of Nebraska athletes doing good works during and after their playing days. Yet no one from the state has made more of an impact both on and off the playing field than Marlin Briscoe. He is arguably the most important athletic figure to ever come out of Nebraska because his accomplishments have great agency not only in the athletic arena but in terms of history, society and race as well. Growing up in the public housing projects of South Omaha in the late 1950s-early 1960s, Briscoe emerged as a phenom in football and basketball. His rise to local athletic stardom occurred during a Golden Era that saw several sports legends make names for themselves in the span of a decade. He wasn’t the biggest or fastest but he might have been the best overall athlete of this bunch that included future collegiate all-Americans and professional stars.

Right from the jump, Briscoe was an outlier in the sport he’s best remembered for today – football. On whatever youth teams he tried out for, he always competed for and won the starting quarterback position. He did the same at Omaha South High and the University of Omaha. This was at a time when predominantly white schools in the North rarely gave blacks the opportunity to play quarterback. The prevailing belief then by many white coaches was that blacks didn’t possess the intellectual or leadership capacity for the position. Furthermore, there was doubt whether white players would allow themselves to be led by a black player. Fortunately there were coaches who didn’t buy into these fallacies. Nurtured by coaches who recognized both his physical talent and his signal-calling and leadership skills, Briscoe excelled at South and OU.

His uncanny ability to elude trouble with his athleticism and smarts saw him make things happen downfield with his arm and in the open field with his legs, often turning busted plays into long gainers and touchdowns. He also led several comebacks. His improvisational knack led local media to dub him “Marlin the Magician.” The nickname stuck.

Briscoe played nine years in the NFL and thrived as a wide receiver, quarterback, holder and defensive back. He may be the most versatile player to ever play in the league.

He also made history as one of the players who brought suit against the NFL and its Rozelle Rule that barred players from pursuing free market opportunities. A judge ruled for the players and that decision helped usher in modern free agency and the rise in salaries for pro athletes.

His life after football began promisingly enough. He was a successful broker and invested well. He was married with kids and living a very comfortable life. Then the fast life in L.A, caught up with him and he eventually developed a serious drug habit. For a decade his life fell apart and he lost everything – his family. his home, his fortune, his health. His recovery began in jail and through resilience and faith he beat the addiction and began rebuilding his life. He headed a boys and girls club in L.A.

His autobiography told his powerful story of overcoming obstacles.

Contemporary black quarterbacks began expressing gratitude to him for being a pioneer and breaking down barriers.

Much national media attention has come his way, too. That attention is growing as a major motion picture about his life nears production. That film, “The Magician,” is being produced by his old teammate and friend John Beasley of Omaha. Beasley never lost faith in Briscoe and has been in his corner the whole way. He looks forward to adapting his inspirational story to the big screen. Briscoe, who often speaks to youth, wants his story of never giving up to reach as many people as possible because that’s a message he feels many people need to hear and see in their own lives, facing their own obstacles.

Briscoe is being inducted in the College Football Hall of Fame this fall. A night in his honor, to raise money for youth scholarships, is happening September 22 at UNO’s Baxter Arena. Video tributes from past and present NFL greats will be featured. The University of Nebraska at Omaha is also unveiling a life size statue of him on campus on September 23. That event is free and open to the public.

There is an effort under way to get the Veterans Committee of the Pro Football Hall of Fame to select Briscoe as an inductee and it’s probably only a matter of time before they do.

The fact that he succeeded in the NFL at three offensive positions – quarterback, wide receiver and holder for placekicks – should be enough to get him in alone. The cincher should be the history he made as the first black starting QB and the transition he made from that spot to receiver. His career statistics in the league are proof enough:

Passing

97 completions of 233 attempts for 1697 yards with 14 TDs and 14 INTs.

Rushing

49 attempts for 336 yards and 3 TDs

Receiving

224 catches for 3537 yards and 30 TDs

Remember, he came into the league as a defensive back, only got a chance to play QB for part of one season and then made himself into a receiver. He had everything working against him and only belief in himself working for him. That, natural ability and hard work helped him prove doubters wrong. His story illusrates why you should never let someone tell you you can’t do something. Dare, risk, dream. He did all that and more. Yes, he stumbled and fell, but he got back up better and stronger than before. Now his story is a testament and a lesson to us all.

The Marlin Briscoe story has more drama, substance and inspiration in it than practically anything you could make up. But it all really happened. And he is finally getting his due.

A North Omaha Reflection

A North Omaha Reflection

Here are my reflections on his post:

Adam Fletcher Sasse, your Forgotten Omaha posts tonight about the way things used to be in North Omaha, using the example of Conestoga Place Neighborhood as an illustration, touches a nerve with residents, past and present. The segregation and confinement of African-Americans in North Omaha had mixed results for blacks and the community as a whole. There is no doubt that at every level of public and private leadership, North O was systematically drained of its resources or denied the resources that other districts enjoyed. With everything working against it, North O, by which I mean northeast Omaha for the purposes of this opinion piece, the neighborhood devolved. Using a living organism analogy, once businesses left en masse, once the packinghouse and railroad jobs disappeared, once the riots left physical and psychological scars, once aspirational and disenchanted blacks fled for greener pastures, once the North Freeway and other urban renewal projects ruptured the community and displaced hundreds, if not thousands more residents, once the gang culture took root, well, you see, North O got sicker and weaker and no longer had enough of an immune system (infrastructure, amenities, jobs, professional class middle class) to heal itself and fend off the poison. There is no doubt the powers that be, including the Great White Fathers who controlled the city then and still control it now, implicity and explicity allowed it to happen and in some cases instigated or directed the very forces that infected and spread this disease of despair and ruin. The wasteland that became sections and swaths of North O did not have to happen and even if there was no stopping it there is no rationale or justiiable reason why redevelopment waited, stalled or occurred in feeble fits and starts and in pockets that only made the contrast between ghetto and renewal more glaring and disturbing. North O’s woes were and are a public health problem and the strong intervening treatments needed have been sorely lacking. As many of us believe, the revitalization underway there today is badly, sadly long overdue. It is appreciated for sure but it is still far too conservative and slow and small compared to the outsized needs. And it may not have happened at all if not for the Great White Fathers being embarrased by Omaha’s shockingly high poverty rates and all the attendant problems associated with poor living conditions, limited opportunities and hopeless attitudes. If not for North Downtown’s emergence, the connecting corridors of North 30th, North 24th and North 16th Streets would likely still be languishing in neglect. Seeing images of what was once a thriving Conestoga neighborhood gone to seed says more than my words could ever say and the sad truth of the matter is is that Adam could post dozens more images of other North O neighborhoods or blocks that suffered the same fate. So much commerce and potential has been lost there. What about reparations for North O? The couple hundred million dollars of recent and in progress construction and the infusion of some new businesses is a drop in the bucket compared to what was lost, stolen, sucked dry, displaced, denied, diverted, misspent, wasted. I know hundreds more millions of dollars are slated to be invested there, but it’s still not getting the job done. It’s like a slow drip IV managing the pain rather than healing the patient. I know that the infusion of money and development are not the only fixes, but it is absolutely necessary and the patient can’t get well and prosper unless there’s enough of it and unless it’s delivered on time. I just hope it’s not too little too late. And like many North Omahans, I’d feel better if residents had more of a say in how their/our community gets redeveloped. I’d feel better if we controlled the pursestrings. We are the stakeholders. Beware of the carpetbaggers.

Marlin Briscoe – An Appreciation

Marlin Briscoe – An Appreciation

©by Leo Adam Biga

Some thoughts about Marlin Briscoe in the year that he is:

•being inducted in the College Football Hall of Fame

•having a life-size status of his likeness dedicated at UNO

•and seeing a feature film about himself going into production this fall

For years, Marlin Briscoe never quite got his due nationally or even locally. Sure, he got props for being a brilliant improviser at Omaha U. but that was small college ball far off most people’s radar. Even fewer folks saw him star before college for the Omaha South High Packers. Yes, he got mentioned as being the first black quarterback in the NFL, but it took two or three decades after he retired from the game for that distinction to sink in and to resonate with contemporary players, coaches, fans and journalists. It really wasn’t until his autobiography came out that the significance of that achievement was duly noted and appreciated. Helping make the case were then-current NFL black quarterbacks, led by Warren Moon, who credited Briscoe for making their opportunity possible by breaking that barrier and overturning race bias concerning the quarterback position. Of course, the sad irony of it all is that Briscoe only got his chance to make history as a last resort by the Denver Broncos, who succumbed to public pressure after their other quarterbacks failed miserably or got injured. And then even after Briscoe proved he could play the position better than anyone else on the squad, he was never given another chance to play QB with the Broncos or any other team. He was still the victim of old attitudes and perceptions, which have not entirely gone away by the way, that blacks don’t have the mental acuity to run a pro-style offensive system or that they are naturally scramblers and not pocket passers or that they are better with their feet and their athleticism than they are with their arms or their head. Briscoe heard it all, and in his case he also heard that he was too small.

After Briscoe swallowed the bitter pill that he would be denied a chance to play QB in The League after that one glorious go of it in 1968, he dedicated himself to learning an entirely new position – wide receiver – as his only way to stay in the NFL. In truth, he could have presumably made it as a defensive back and return specialist. In fact, he was primarily on the Broncos roster as a DB when he finally got the nod to start at QB after only seeing spot duty there. Briscoe threw himself into the transition to receiver with the Buffalo Bills and was good enough to become an All-Pro with them and a contributing wideout with the back to back Super Bowl winning Miami Dolphins. As unfair as it was, Briscoe didn’t make a big stink about what happened to him and his QB aspirations, He didn’t resist or refuse the transition to receiver. He worked at it and made it work for him and the teams he played on. The successful transition he made from signal caller to received is one of the most remarkable and overlooked feats in American sports history.

About a quarter century after Briscoe’s dreams of playing QB were dashed and he reinvented himself as a receiver, another great Omaha athlete, Eric Crouch, faced a similar crossroads. The Heisman Trophy winner was an option quarterback with great athleticism and not well suited to being a pro style pocket passer. He was drafted by the NFL’s St. Louis Rams as an athlete first, but ostensibly to play receiver, not quarterback. He insisted on getting a tryout at QB and failed. The Rams really wanted him to embrace being a receiver but his heart wasn’t in it and he loudly complained about not being given a shot at QB. He went from franchise to franchise and from league to league chasing a dream that was not only unrealistic but a bad fit that would not, could not, did not fit his skills set at that level of competition. Unlike Briscoe, who lost the opportunity to play QB because he was black, Crouch lost the opportunity because he wasn’t good enough. Briscoe handled the discrimination he faced with great integrity and maturity. Crouch responded to being told the truth with petulance and a sense of denial and entitlement. That contrast made a big impression on me. I don’t know if Crouch would have made a successful transition to receiver the way Brsicoe did, but he certainly had the skils to do it, as he showed at Nebraska. I always thought NU should have kept him at wingback and Bobby Newcombe at QB, but that’s for another post.

But the real point is that when the going got tough for Briscoe, he rose to the occasion. That strong character is what has allowed him to recover from a serious drug addiction and to live a sober, successful life these past two-plus decades. John Beasley is producing a feature film about Briscoe called “The Magician” and its story of personal fortitude will touch many lives.

Link to my profile of Marlin Briscoe at–

Link to my collection of stories on Omaha’s Black Sports Legends: Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness at–

OUT TO WIN – THE ROOTS OF GREATNESS: OMAHA’S BLACK SPORTS LEGENDS

Talking it out: Inclusive Communities makes hard conversations the featured menu item at Omaha Table Talk

My, how Omaha loves to talk about race and then not. Everyone has an opinion on race and the myriad issues bound up in it. Most of us save our opinions on this topic for private, close company encounters with friends and family. Only few dare to expose their beliefs in public or among strangers. Inclusive Communities organizes a forum called Omaha Table Talk for discussiing race and other sensitive subjects in small group settings led by a facililator over a meal. It is a safe meeting ground where folks can say what’s on their mind and hear another point of view over the communal experience of breaking bread. I am not sure what all this talking accomplishes in the final analysis since the people predisposed to participate in such forums are generally of like minds in terms of supporting inclusivity and respecting diversity. But I suppose there’s always a chance of learning something new and receiving a if-you-could-walk-in-my-shoes lesson or two that might expand your thinking and perception. For the voiceless masses, however, I think race remains an individually lived experience that only really gets expressed in our heads and among our small inner circle. But I suspect not much then either, except when we see something that angers us as a racially motivated hate crime or a blatant case of racism and discrimination. Otherwise, most of us keep a lid on it, lest we blow up and say something we regret because it might be misunderstood and taken as an insult or offense. The dichotomy of these times is that we live in an Anything Goes era within a Politically Correct culture. Therefore, we are encouraged to say what is on our mind and not. And thus the silent majority plods, often gitting their teeth, while talking heads let out torrents of vitriol or rhetoric.

Talking it out: Inclusive Communities makes hard conversations the featured menu item at Omaha Table Talk

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the January-February 2016 issue of Omaha Magazine

When Catholic Charities of Omaha looked for somebody to take over its open race and identity forum, Omaha Table Talk, it found the right host in Inclusive Communities.

Formerly a chapter of the National Conference for Christians and Jews, the human relations organization started in 1938 to overcome racial and identity divisions. While the name it goes by today may be unfamiliar, the work Inclusive Communities does building bridges of understanding in order to surmount bigotry remains core to its mission. Many IC programs today are youth focused and happen in schools and residential camp settings. IC also takes programs into workplaces.

Table Talk became one of its community programs in 2012-2013. Where Table Talk used to convene people once a year around dinners in private homes to dialogue about black-white relations, under new leadership it’s evolved into a monthly event in public spaces tackling rotating topics. Participation is by registration only.

The November session dug into law enforcement and community. The annual interfaith dialogue happens Jan. 12. Reproductive rights and sex education is on tap March 22 and human trafficking is on the docket April 22,

The annual Main Event on February 9 is held at 20 metro area locations. As always, race and identity will be on the menu. Omaha North High Spanish teacher Alejandro García, a native of Spain, attended the October 13 Ethnic Potluck Table Talk and came away impressed with the exchanges that occurred.

“I had the opportunity to engage in very open conversations with people that shared amazing life stories,” he says. “I am drawn to things that relate to diversity, integration and tolerance. Even though I think I have a pretty open mind and I consider myself pretty tolerant I know this is an illusion. We all have big prejudices and fears of difference. So I think these opportunities allow us to get rid of preconceptions.”

New IC executive director Maggie Wood appreciates the platform Table Talk affords people to share their own stories and to learn other people’s stories.

“It’s exciting to be a part of a youth-driven organization that’s really looking to make a difference in the world. It’s about putting the mic in people’s hands and giving them the opportunity to voice what they feel is important.

“What I think Omaha Table Talk does is really give us the opportunity to have conversations we wouldn’t normally have in a structured way that helps us to think about other people’s ideas. Nobody else in town is doing this real conversation about tough topics.”

“These conversations do not happen in day-to-day life, at least not in my environment,” Garcia says. “I see people avoiding these topics. They find it uncomfortable and they are never in the mood to speak up for the things they might consider to be wrong and that need to be fixed. If you don’t talk about the problems in your community, you will never fix them.”

“The really beautiful thing about Omaha Table Talk,” Wood says, “is it really brings about hope for people who see how more alike we are than different.”

Maggie Wood

Operations director Krystal Boose says, “What makes Inclusive Communities special is we are very good at creating a safe space. It’s so interesting to see how quickly people open up about their identities. Part of it is the way we utilize our volunteers to help navigate and guide those conversations.”

Gabriela Martinez, who participated in IC youth programs, now helps coordinate Table Talk. She says no two conversations are alike. “They’re different at every site. You have a different group of people every single place with different facilitators. We have a set of guided questions but the conversation goes where people want to take it.”

Gabriela Martinez

Wood says the whole endeavor is quid pro quo.

“We need the participants as much as the participants need us. We need individuals to be there to help us drive the conversation in Omaha starting around the table. We’re now looking at how do we put the tools in participants’ hands to go out and advocate for the change they want to see.”

She says IC can connect people with organizations “doing work that’s important to them.”

IC staff feel Table Talk dialogues feed social capital.

“We’re planting seeds for future conversations” and “we’re giving a voice to a lot of people who think they don’t have one,” Martinez says.

“It’s not good enough to just empower them and give them voices and then release them into a world that’s not inclusive and shuts them back down,” Boose says. “It’s our responsibility to help create workplaces for them that value inclusivity and diversity.” Martinez, a recent Creighton University graduate, says milllennials like her “want and expect diversity and inclusion in workplaces – it’s not optional.”

Krsytal Boose

Boose says growing participation, including big turnouts for last summer’s North and South Omaha Table Talks and new community partners, “screams that Omaha is hungry for these conversations.”

Organizers say you don’t have to be a social justice warrior either to participate. Just come with an open mind.

Main Event registration closes January 15.

The IC Humanitarian Brunch is March 19 at Ramada Plaza Center. Keynote speaker is Omaha native and Bernie Sanders press secretary Symone Sanders. For details on these events and other programs, visit http://www.inclusive-communities.org/.

Play considers Northside black history through eyes of Omaha Star publisher Mildred Bown

Upcoming Great Plains Theatre Conference PlayFest productions at nontraditional sites examine North Omaha themes as part of this year’s Neighborhood Tapestries. On May 29 the one-woman play Northside Carnation, both written and performed by Denise Chapman, looks at a pivotal night through the eyes of Omaha Star icon Mildred Brown at the Elks Lidge. On May 31 Leftovers, by Josh Wilder and featuring a deep Omaha cast, explores the dynamics of inner city black family life outside the home of the late activist-journalist Charles B. Washington. Performances are free.

Play considers Northside black history through eyes of Omaha Star publisher Mildred Bown

Denise Chapman portrays the community advocate on pivotal night in 1969

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

As North Omaha Neighborhood Tapestries returns for the Great Plains Theatre Conference’s free PlayFest bill, two community icons take center stage as subject and setting.

En route to making her Omaha Star newspaper an institution in the African-American community, the late publisher Mildred Brown became one herself. Through the advocacy role she and her paper played, Brown intersected with every current affecting black life here from the 1930s on. That makes her an apt prism through which to view a slice of life in North Omaha in the new one-woman play Northside Carnation.

This work of historical fiction written by Omaha theater artist Denise Chapman will premiere Sunday, May 29 at the Elks Lodge, 2420 Lake Street. The private social club just north of the historic Star building was a familiar spot for Brown. It also has resonance for Chapman as two generations of her family have been members. Chapman will portray Brown in the piece.

Directing the 7:30 p.m. production will be Nebraska Theatre Caravan general manger Lara Marsh.

An exhibition of historic North Omaha images will be on display next door at the Carver Bank. A show featuring art by North Omaha youth will also be on view at the nearby Union for Contemporary Art.

Two nights later another play, Leftovers, by Josh Wilder of Philadelphia, explores the dynamics of an inner city black family in a outdoor production at the site of the home of the late Omaha activist journalist Charles B. Washington. The Tuesday, May 31 performance outside the vacant, soon-to-be-razed house, 2402 North 25th Street, will star locals D. Kevin Williams, Echelle Childers and others. Levy Lee Simon of Los Angeles will direct.

Just as Washington was a surrogate father and mentor to many in North O, Brown was that community’s symbolic matriarch.

Denise Chapman

Chapman says she grew up with “an awareness” of Brown’s larger-than-life imprint and of the paper’s vital voice in the community but it was only until she researched the play she realized their full impact.

“She was definitely a very important figure. She had a very strong presence in North Omaha and on 24th Street. I was not aware of how strong that presence was and how deep that influence ran. She was really savvy and reserved all of her resources to hold space and to make space for people in her community – fighting for justice. insisting on basic human rights, providing jobs, putting people through school.

“She really was a force that could not be denied. The thing I most admire was her let’s-make-it-happen approach and her figuring out how to be a black woman in a very white, male-dominated world.”

Brown was one of only a few black female publishers in the nation. Even after her 1989 death, the Star remained a black woman enterprise under her niece, Marguerita Washington, who succeeded her as publisher. Washington ran it until falling ill last year. She died in February. The paper continues printing with a mostly black female editorial and advertising staff.

Chapman’s play is set at a pivot point in North O history. The 1969 fatal police shooting of Vivian Strong sparked rioting that destroyed much of North’s 24th “Street of Dreams.” As civil unrest breaks out, Brown is torn over what to put on the front page of the next edition.

“She’s trying her best to find positive things to say even in times of toil,” Chapman says. “She speaks out reminders of what’s good to help reground and recenter when everything feels like it’s upside down. It’s this moment in time and it’s really about what happens when a community implodes but never fully heals.

“All the parallels between what was going on then and what we see happening now were so strong it felt like a compelling moment in time to tell this story. It’s scary and sad but also currently repeating itself. I feel like there are blocks of 24th Street with vacant lots and buildings irectly connected to that last implosion.”

Mildred Brown and the Omaha Star offices

During the course of the evening, Chapman has Brown recall her support of the 1950s civil rights group the De Porres Club and a battle it waged for equal job opportunities. Chapman, as Brown, remembers touchstone figures and places from North O’s past, including Whitney Young, Preston Love Sr., Charles B. Washington, the Dreamland Ballroom and the once teeming North 24th Street corridor.

“There’s a thing she says in the play that questions all the work they did in the ’50s and yet in ’69 we’re still at this place of implosion,” Chapman says. “That’s the space that the play lives in.”

To facilitate this flood of memories Chapman hit upon the device of a fictional young woman with Brown that pivotal night.

“I have imagined a young lady with her this evening Mildred is finalizing the front page of the paper and their conversations take us to different points in time. The piece is really about using her life and her work as a lens and as a way to look at 24th Street and some of the cultural history and struggle the district has gone through.”

Chapman has been studying mannerisms of Brown. But she’s not as concerned with duplicating the way Brown spoke or walked, for instance, as she is capturing the essence of her impassioned nature.

“Her spirit, her drive, her energy and her tenacity are the things I’m tapping into as an actor to create this version of her. I think you will feel her force when I speak the actual words she said in support of the Omaha and Council Bluffs Railway and Bridge Company boycott. She did not pull punches.”

Chapman acknowledges taking on a character who represented so much to so many intimidated her until she found her way into Brown.

“When I first approached this piece I was a little hesitant because she was this strong figure whose work has a strong legacy in the community. I was almost a little afraid to dive in. But during the research and what-if process of sitting with her and in her I found this human being who had really big dreams and passions. But her efforts were never just about her. The work she did was always about uplifting her people and fighting for justice and making pathways for young people towards education and doing better and celebrating every beautiful accomplishment that happened along the way.”

Chapman found appealing Brown’s policy to not print crime news. “Because of that the Star has kept for us all of these beautiful every day moments of black life – from model families to young people getting their degrees and coming back home for jobs to social clubs. All of these every day kind of reminders that we’re just people.”

For the complete theater conference schedule, visit https://webapps.mccneb.edu/gptc/.

RANDOM INSPIRATION

RANDOM INSPIRATION

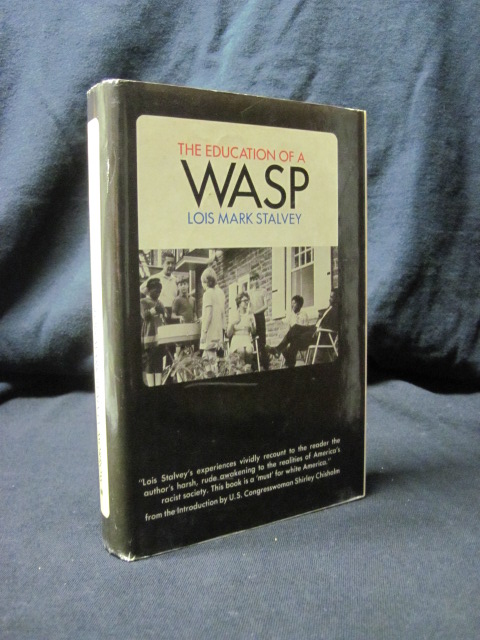

Got a call out of the blue yesterday afternoon from an 86-year-old man in Omaha. He’s a retired Jewish American retailer. He’d just finished reading my November Reader cover story about The Education of a WASP and the segregation issues that plagued Omaha. He just wanted to share how much he enjoyed it and how he felt it needed to be seen by more people. Within a few minutes it was clear the story also summoned up in him strong memories and feelings having to do with his own experiences of bigotry as a Jewish kid getting picked on and bullied and as a businessman taking a stand against discrimination by hiring black clerks in his stores. One of his stores was at 24th and Erskine in the heart of North Omaha and the African-American district there and that store employed all black staff. But he also hired blacks at other storees, including downtown and South Omaha, and some customers were not so accepting of it and he told them flat out they could take their business elsewhere. He also told a tale that I need to get more details about that had to do with a group of outsiders who warned-threatened him to close his North O business or else. His personal accounts jumped from there to serving in the military overseas to his two marriages, the second of which is 60 years strong now. He wanted to know why I don’t write for the Omaha World-Herald and I explained that and he was eager to hook me up with the Jewish Press, whereupon I informed him I contributed to it for about 15 years. I also shared that I have done work for the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society. It turns out the man who brought me and my work to the attention of the Press and the Historical Society, the late Ben Nachman, was this gentleman’s dentist. Small world. I also shared with him why I write so much about African-American subjects (it has to do in part with where and how I grew up). Anyway, it was a delightful interlude in my day talking to this man and I will be sure to talk with him again and hopefully meet him. He’s already assured me he will be calling back. I am eager for him to do so. It’s rare that people call me about my work and this unexpected reaching out and expression of appreciation by a reader who was a total stranger was most appreciated. That stranger is now a friend.

Here is the story that motivated that new friend to call me about:

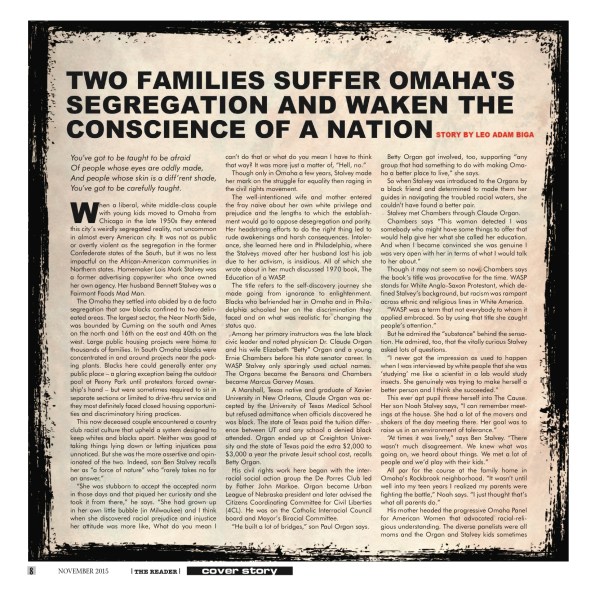

Two families suffer Omaha’s segregation and waken the conscience of a nation

My newest cover story appears in the November 2015 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com) and it explores dimensions of race in America through the prism of a 1970 book whose events and themes still have relevance and resonance with today. Lois Mark Stalvey’s book The Education of a WASP largely grew out of her experience learning the architecture and construction of racism from black friends in Omaha and Philadelphia whose lives were, by necessity, built around barriers constricting their lives. The inequality and discrimination blacks faced came as a revelation to the White Anglo Saxon Protestant Stalvey, whose education into social awareness and consciousness changed the arc of her life. Two of her primary educators in Omaha were Ernie Chambers and the late Dr. Claude Organ. By the time the book came out Chambers had won election to the Nebraska Legislature and Organ enjoyed a noted career as a surgeon educator at Creighton University. Along the way, Chambers played a prominent role in a famous race documentary shot in Omaha, A Time for Burning, and the Organs, whom Stalvey tried to get to integrate her neighborhood, built a new home in a neighborhood and parish that didn’t appreicate their presence. They stayed anyway.

Two families suffer Omaha’s segregation and waken the conscience of a nation

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the November 2015 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

A WASP’s racial tightrope resulted in enduring book

©by Leo Adam Biga

You’ve got to be taught to be afraid

Of people whose eyes are oddly made,

And people whose skin is a diff’rent shade,

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

When a liberal, white middle-class couple with young kids moved to Omaha from Chicago in the late 1950s they entered this city’s weirdly segregated reality, not uncommon in almost every American city. It was not as public or overtly violent as the segregation in the former Confederate states of the South, but it was no less impactful on the African-American communities in Northern states. Homemaker Lois Mark Stalvey was a former advertising copywriter who once owned her own agency. Her husband Bennett Stalvey was a Fairmont Foods Mad Man.

The Omaha they settled into abided by a de facto segregation that saw blacks confined to two delineated areas. The largest sector, the Near North Side, was bounded by Cuming on the south and Ames on the north and 16th on the east and 40th on the west. Large public housing projects were home to thousands of families. In South Omaha blacks were concentrated in and around projects near the packing plants. Blacks here could generally enter any public place – a glaring exception being the outdoor pool at Peony Park until protestors forced ownership’s hand – but were sometimes required to sit in separate sections or limited to drive-thru service and they most definitely faced closed housing opportunities and discriminatory hiring practices.

This now deceased couple encountered a country club racist culture that upheld a system designed to keep whites and blacks apart. Neither was good at taking things lying down or letting injustices pass unnoticed. But she was the more assertive and opinionated of the two. Indeed, son Ben Stalvey recalls her as “a force of nature” who “rarely takes no for an answer.”

“She was stubborn to accept the accepted norm in those days and that piqued her curiosity and she took it from there,” he says. “She had grown up in her own little bubble (in Milwaukee) and I think when she discovered racial prejudice and injustice her attitude was more like, What do you mean I can’t do that or what do you mean I have to think that way? It was more just a matter of, “Hell, no.”

Though only in Omaha a few years, Stalvey made her mark on the struggle for equality then raging in the civil rights movement.

The well-intentioned wife and mother entered the fray naive about her own white privilege and prejudice and the lengths to which the establishment would go to oppose desegregation and parity. Her headstrong efforts to do the right thing led to rude awakenings and harsh consequences. Intolerance, she learned here and in Philadelphia, where the Stalveys moved after her husband lost his job due to her activism, is insidious. All of which she wrote about in her much discussed 1970 book, The Education of a WASP.

The title refers to the self-discovery journey she made going from ignorance to enlightenment. Blacks who befriended her in Omaha and in Philadelphia schooled her on the discrimination they faced and on what was realistic for changing the status quo.

Among her primary instructors was the late black civic leader and noted physician Dr. Claude Organ and his wife Elizabeth “Betty” Organ and a young Ernie Chambers before his state senator career. In WASP Stalvey only sparingly used actual names. The Organs became the Bensons and Chambers became Marcus Garvey Moses.

A Marshall, Texas native and graduate of Xavier University in New Orleans, Claude Organ was accepted by the University of Texas Medical School but refused admittance when officials discovered he was black. The state of Texas paid the tuition difference between UT and any school a denied black attended. Organ ended up at Creighton University and the state of Texas paid the extra $2,000 to $3,000 a year the private Jesuit school cost, recalls Betty Organ.

His civil rights work here began with the interracial social action group the De Porres Club led by Father John Markoe. Organ became Urban League of Nebraska president and later advised the Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties (4CL). He was on the Catholic Interracial Council board and Mayor’s Biracial Committee.

“He built a lot of bridges,” son Paul Organ says.

Betty Organ got involved, too, supporting “any group that had something to do with making Omaha a better place to live,” she says.

So when Stalvey was introduced to the Organs by a black friend and determined to made them her guides in navigating the troubled racial waters, she couldn’t have found a better pair.

Stalvey met Chambers through Claude Organ.

Chambers says “This woman detected I was somebody who might have some things to offer that would help give her what she called her education. And when I became convinced she was genuine I was very open with her in terms of what I would talk to her about.”

Though it may not seem so now, Chambers says the book’s title was provocative for the time. WASP stands for White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, which defined Stalvey’s background, but racism was rampant across ethnic and religious lines in White America.

“WASP was a term that not everybody to whom it applied embraced. So by using that title she caught people’s attention.”

But he admired the “substance” behind the sensation. He admired, too, that the vitally curious Stalvey asked lots of questions.

“I never got the impression as used to happen when I was interviewed by white people that she was ‘studying’ me like a scientist in a lab would study insects. She genuinely was trying to make herself a better person and I think she succeeded.”

This ever apt pupil threw herself into The Cause. Her son Noah Stalvey says, “I can remember meetings at the house. She had a lot of the movers and shakers of the day meeting there. Her goal was to raise us in an environment of tolerance.”

“At times it was lively,” says Ben Stalvey. “There wasn’t much disagreement. We knew what was going on, we heard about things. We met a lot of people and we’d play with their kids.”

All par for the course at the family home in Omaha’s Rockbrook neighborhood. “It wasn’t until well into my teen years I realized my parents were fighting the battle,” Noah says. “I just thought that’s what all parents do.”

His mother headed the progressive Omaha Panel for American Women that advocated racial-religious understanding. The diverse panelists were all moms and the Organ and Stalvey kids sometimes accompanied their mothers to these community forums. Paul Organ believes the panelists wielded their greatest influence at home.

“On the surface all the men in the business community were against it.

Behind the scenes women were having these luncheons and meetings and I think in many homes around Omaha attitudes were changed over dinner after women came back from these events and shared the issues with their husbands. To me it was very interesting the women and the moms kind of bonded together because they all realized how it was affecting their children.”

Betty Organ agrees. “I don’t think the men were really impressed with what we were doing until they found out its repercussions concerning their children and the attitudes their children developed as they grew.”

Stalvey’s efforts were not only public but private. She personally tried opening doors for the aspirational Organs and their seven children to integrate her white bread suburban neighborhood. She felt the northeast Omaha bungalow the Organs occupied inadequate for a family of nine and certainly not befitting the family of a surgeon.

Racial segregation denied the successful professional and Creighton University instructor the opportunity for living anywhere outside what was widely accepted as Black Omaha – the area in North Omaha defined by realtors and other interests as the Near North Side ghetto.

“She had seen us when we lived in that small house on Paxton Boulevard,” Betty Organ says. “She had thought that was appalling that we should be living that many people in a small house like that.”

Despite the initial reluctance of the Organs, Stalvey’s efforts to find them a home in her neighborhood put her self-educating journey on a collision course with Omaha’s segregation and is central to the books’s storyline. Organ appreciated Stalvey going out on a limb.

Stalvey and others were also behind efforts to open doors for black educators at white schools, for employers to practice fair hiring and for realtors to abide by open housing laws. Stalvey found like-minded advocates in social worker-early childhood development champion Evie Zysman and the late social cause maven Susie Buffett. They were intent on getting the Organs accepted into mainstream circles.

“We were entertained by Lois’ friends and the Zysmans and these others that were around. We went to a lot of places that we would not have ordinarily gone because these people were determined they were going to get us into something,” Betty Organ says. “It was very revealing and heartwarming that she wanted to do something. She wanted to change things and it did happen.”

Only the change happened either more gradually than Stalvey wanted or in ways she didn’t expect.

Despite her liberal leanings Claude Organ remained wary of Stalvey.

“He felt she was as committed as she could be,” his widow says, “but he just didn’t think she knew what the implications of her involvement would be. He wasn’t exactly sure about how sincere Lois was. He thought she was trying to find her way and I think she more or less did find her way. It was a very difficult time for all of us, that’s all I can say.”

Ernie Chambers says Stalvey’s willingness to examine and question things most white Americans accepted or avoided was rare.

“At the time she wrote this book it was not a popular thing. There were not a lot of white people willing to step forward, identify themselves and not come with the traditional either very paternalistic my-best-friend-is-a-Negro type of thing or out-and-out racist attitude.”

The two forged a deep connection borne of mutual respect.

“She was surprised I knew what I knew, had read as widely as I had, and as we talked she realized it was not just a book kind of knowledge. In Omaha for a black man to stand up was considered remarkable.

“We exchanged a large number of letters about all kinds of issues.”

Chambers still fights the good fight here. Though he and Claude Organ had different approaches, they became close allies.

Betty Organ says “nobody else was like” Chambers back then. “He was really a moving power to get people to do things they didn’t want to do. My husband used to go to him as a barber and then they got to be very good friends. Ernie really worked with my husband and anything he wanted to accomplish he was ready to be there at bat for him. He was wonderful to us.”

Stalvey’s attempts to infiltrate the Organs into Rockbrook were rebuffed by realtors and residents – exactly what Claude Organ warned would happen. He also warned her family might face reprisals.

Betty Organ says, “My husband told her, ‘You know this can have great repercussions because they don’t want us and you can be sure that because they don’t want us they’re going to red line us wherever we go in Omaha trying to get a place that they know of.'”

Bennett Stalvey was demoted by Fairmont, who disliked his wife’s activities, and sent to a dead-end job in Philadelphia. The Organs regretted it came to that.

“It was not exactly the thing we wanted to happen with Ben,” Betty Organ says. “That was just the most ugly, un-Godly, un-Christian thing anybody could have done.”

While that drama played out, Claude Organ secretly bought property and secured a loan through white doctor friends so he could build a home where he wanted without interference. The family broke ground on their home on Good Friday in 1964. The kids started school that fall at St. Philip Neri and the brick house was completed that same fall.

“We had the house built before they (opponents) knew it,” Betty Organ says.

Their spacious new home was in Florence, where blacks were scarce. Sure enough, they encountered push-back. A hate crime occurred one evening when Betty was home alone with the kids.

“Somebody came knocking on my door. This man was frantically saying, ‘Lady, lady, you know your house is one fire?’ and I opened the door and I said, ‘What?’ and he went, ‘Look,’ and pointed to something burning near the house. I looked out there, and it was a cross burning right in front of the house next to the garage. When the man saw what it was, too, he said, ‘Oh, lady, I’m so sorry.’ It later turned out somebody had too much to drink at a bar called the Alpine Inn about a mile down the road from us and did this thing.

“I just couldn’t believe it. It left a scorch there on the front of the house.”

Paul Organ was 9 or 10 then.

“I have memories of a fire and the fire truck coming up,” he says. “I remember something burning on the yard and my mom being upset. I remember when my dad got home from the hospital he was very upset but it wasn’t until years later I came to appreciate how serious it was. That was probably the most dramatic, powerful incident.”

But not the last.

As the only black family in St. Philip Neri Catholic parish the Organs seriously tested boundaries.

“Some of the kids there were very ugly at first,” Betty Organ recalls. “They bullied our kids. It was a real tough time for all of us because they just didn’t want to accept the fact we were doing this Catholic thing.”

You’ve got to be taught

To hate and fear,

You’ve got to be taught

From year to year,

It’s got to be drummed

In your dear little ear

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

Daughter Sandra Organ says, “There were some tensions there. Dad would talk about how to handle these kind of things and to take the high road. But if they used the ‘n’ word we had an opportunity to retaliate because you defend your honor as a black person.

“An older neighbor man didn’t particularly like black people. But his grandson was thrilled to have these five boys to play with, so he became like an extra person in the family. The boy’s family was very kind to us and they kind of brought the grandfather around.”

Betty Organ says things improved with parishioners, too. “It got to the point where they got to know the family and they got to know us and they kind of came around after a few years.”

Sandra says when her brother David suffered severe burns in an accident and sat-out school “the neighborhood really rallied around my mom and provided help for her and tutoring for David.”

Stalvey came from Philadelphia to visit the Organs at their new home.

“When she saw the house we built she was just thrilled to death to see it,” Betty Organ says.

In Philadelphia the Stalveys lived in the racially mixed West Mount Airy neighborhood and enrolled their kids in predominantly African-American inner city public schools.

Ben Stalvey says, “I think it was a conscious effort on my parents part to expose us to multiple ways of living.”

His mother began writing pieces for the Philadelphia Bulletin that she expanded into WASP.

“Mom always had her writing time,” Ben Stalvey notes. “She had her library and that was her writing room and when she in the writing room we were not to disturb her and so yes I remember her spending hours and hours in there. She’d always come out at the end of the school day to greet us and often times she’d go back in there until dinner.”

In the wake of WASP she became a prominent face and voice of white guilt – interviewed by national news outlets, appearing on national talk shows and doing signings and readings. Meanwhile, her husband played a key role developing and implementing affirmative action plans.

Noah Stalvey says any negative feedback he felt from his parents’ activism was confined to name-calling.

“I can remember vaguely being called an ‘n’ lover and that was mostly in grade school. My mother would be on TV or something and one of the kids who didn’t feel the way we did – their parents probably used the word – used it on us at school.”

He says the work his parents did came into focus after reading WASP.

“I first read it when I was in early high school. It kind of put together pieces for me. I began to understand what they were doing and why they were doing it and it made total sense to me. You know, why wouldn’t you fight for people who were being mistreated. Why wouldn’t you go out of your way to try and rectify a wrong? It just made sense they were doing what they could to fix problems prevalent in society.”

Betty Organ thought WASP did a “pretty good” job laying out “what it was all about” and was relieved their real identities were not used.

“That was probably a good thing at the time because my husband didn’t want our names involved as the persons who educated the WASP.”

After all, she says, he had a career and family to think about. Dr. Claude Organ went on to chair Creighton’s surgery department by 1971, becoming the first African-American to do so at a predominately white medical school. He developed the school’s surgical residency program and later took positions at the University of Oklahoma and University of California–Davis, where he also served as the first African-American editor of Archives of Surgery, the largest surgical journal in the English-speaking world.

Sandra Organ says there was some queasiness about how Stalvey “tried to stand in our shoes because you can never really know what that’s like.” However, she adds, “At least she was pricking people’s awareness and that was a wise thing.”

Paul Organ appreciates how “brutally honest” Stalvey was about her own naivety and how embarrassed she was in numerous situations.” He says, “I think at the time that’s probably why the book had such an effect because Lois was very self-revealing.”

Stalvey followed WASP with the book Getting Ready, which chronicled her family’s experiences with urban black education inequities.

At the end of WASP she expresses both hope that progress is possible – she saw landmark civil rights legislation enacted – and despair over the slow pace of change. She implied the only real change happens in people’s hearts and minds, one person at a time. She equated the racial divide in America to walls whose millions of stones must be removed one by one. And she stated unequivocally that America would never realize its potential or promise until there was racial harmony.

Forty-five years since WASP came out Omaha no longer has an apparatus to restrict minorities in housing, education, employment and recreation – just hardened hearts and minds. Today, blacks live, work, attend school and play where they desire. Yet geographic-economic segregation persists and there are disproportionate numbers living in poverty. lacking upwardly mobile job skills, not finishing school, heading single-parent homes and having criminal histories in a justice system that effectively mass incarcerates black males. Many blacks have been denied the real estate boom that’s come to define wealth for most of white America. Thus, some of the same conditions Stalvey described still exist and similar efforts to promote equality continue.

Stalvey went on to teach writing and diversity before passing away in 2004. She remained a staunch advocate of multiculturalism. When WASP was reissued in 1989 her new foreword expressed regret that racism was still prevalent. And just as she concluded her book the first time, she repeated the need for our individual and collective education to continue and her indebtedness to those who educated her.

Noah Stalvey says her enduring legacy may not be so much what she wrote but what she taught her children and how its been passed down.

“It does have a ripple effect and we now carry this message to our kids and our kids are raised to believe there is no difference regardless of sexual preference or heritage or skin color.”

Ben Stalvey says his mother firmly believed children are not born with prejudice and intolerance but learn these things.

“There’s a song my mother used to quote which I still like that’s about intolerance – ‘You’ve Got to be Carefully Taught’ – from the musical South Pacific.

“The way we were raised we were purposely not taught,” Ben Stalvey says. “I wish my mother was still around to see my own grandchildren. My daughter has two kids and her partner is half African-American and half Filipino. I think back to the very end of WASP where she talks about her hopes and dreams for America of everyone being a blended heritage and that has actually come to pass in my grandchildren.”

You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late,

Before you are six or seven or eight,

To hate all the people your relatives hate,

You’ve got to be carefully taught!

Stalvey’s personal chronicle of social awareness a primer for racial studies

©by Leo Adam Biga

With America in the throes of the 1960s civil rights movement, few whites publicly conceded their own prejudice, much less tried seeing things from a black point of view. Lois Mark Stalvey was that exception as she shared her journey from naivety to social consciousness in her 1970 book The Education of a WASP.

Her intensely personal chronicle of becoming a socially aware being and engaged citizen has lived on as a resource in ethnic studies programs.

Stalvey’s odyssey was fueled by curiosity that turned to indignation and then activism as she discovered the extent to which blacks faced discrimination. Her education and evolution occurred in Omaha and Philadelphia. She got herself up to speed on the issues and conditions impacting blacks by joining organizations focused on equal rights and enlisting the insights of local black leaders. Her Omaha educators included Dr. Claude Organ and his wife Elizabeth “Betty” Organ (Paul and Joan Benson in the book) and Ernie Chambers (Marcus Garvey Moses).

She joined the local Urban League and led the Omaha chapter of the Panel of American Women. She didn’t stop at rhetoric either. She took unpopular stands in support of open housing and hiring practices. She attempted and failed to get the Organs integrated into her Rockbrook neighborhood. Pushing for diversity and inclusion got her blackballed and cost her husband Bennett Stalvey his job.

After leaving Omaha for Philly she and her husband could have sat out the fight for diversity and equality on the sidelines but they elected to be active participants. Instead of living in suburbia as they did here they moved into a mixed race neighborhood and sent their kids to predominantly black urban inner city schools. Stalvey surrounded herself with more black guides who opened her eyes to inequities in the public schools and to real estate maneuvers like block busting designed to keep certain neighborhoods white.

Behind the scenes, her husband helped implement some of the nation’s first affirmative action plans.

Trained as a writer, Stalvey used her gifts to chart her awakening amid the civil rights movement. Since WASP’s publication the book’s been a standard selection among works that about whites grappling with their own racism and with the challenges black Americans confront. It’s been used as reading material in multicultural, ethnic studies and history courses at many colleges and universities.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln associate professor of History and Ethnic Studies Patrick Jones has utilized it in two courses.

“In both courses students had a very positive response to the book,” he says. “The book’s local connections to Omaha literally bring the topic of racial identity formation and race relations ‘home’ to students. This local dynamic often means a more forceful impact on Neb. students, regardless of their own identity or background.

“In addition, the book effectively underscores the ways that white racial identity is socially constructed. Students come away with a much stronger understanding of what many call ‘whiteness’ and ‘white privilege” This is particularly important for white students, who often view race as something outside of themselves and only relating to black and brown people. Instead, this book challenges them to reckon with the various ways their own history, experience, socialization, acculturation and identity are racially constructed.”

Jones says the book’s account of “white racial identity formation” offers a useful perspective.

“As Dr. King, James Baldwin and others have long asserted, the real problem of race in America is not a problem with black people or other people of color, but rather a problem rooted in the reality of white supremacy, which is primarily a fiction of the white mind. If we are to combat and overcome the legacy and ongoing reality of white supremacy, then we need to better understand the creation and perpetuation of white supremacy, white racial identity and white privilege, and this book helps do that.

“What makes whiteness and white racial identity such an elusive subject for many to grasp is its invisibility – the way it is rendered normative in American society. Critical to a deeper understanding of how race works in the U.S. is rendering whiteness and white supremacy visible.”

Stalvey laid it all right out in the open through the prism of her experience. She continued delineating her ongoing education in subsequent books and articles she wrote and in courses she taught.

Interestingly, WASP was among several popular media examinations of Omaha’s race problem then. A 1963 Look magazine piece discussed racial divisions and remedies here. A 1964 Ebony profile focused on Don Benning breaking the faculty-coaching color barrier at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The 1966 film A Time for Burning featured Ernie Chambers serving a similar role as he did with Stalvey, only this time educating a white pastor and members of Augustana Lutheran Church struggling to do interracial fellowship. The documentary prompted a CBS News special.

Those reports were far from the only local race issues to make national news. Most recently, Omaha’s disproportionately high black poverty and gun violence rates have received wide attention.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

A WASP’s racial tightrope resulted in enduring book partially set in 1960s Omaha

White people don’t know shit about black people.

That’s an oversimplification and generalization to be sure but it largely holds true today that many whites don’t know a whole lot about blacks outside of surface cultural things that fail to really get to the heart of the black experience or what it means to be black in America. That was certainly even more true 50 years ago or so when the events described in the 1970 book The Education of a WASP went down. The book’s author, the late Lois Mark Stalvey, was a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant and thus WASP Omaha homemaker in the late 1950s-early 1960s when she felt compelled to do something about the inequality confronting blacks that she increasingly became aware of during the civil rights movement. Her path to a dawning social consciousness was aided by African-Americans in Omaha and Philadelphia, where she moved, including some prominent players on the local social justice scene. Ernie Chambers was one of her educators. The late Dr. Claude Organ was another. Stalvey talked to and learned from socially active blacks. She got involved in The Cause through various organizations and initiatives. She even put herself and her family on the line by advocating for open housing, education, and hiring practices.

Her book made waves for baring the depths of her white prejudice and privilege and giving intimate view and voice to the struggles and challenges of blacks who helped her evolve as a human being and citizen. Those experiences forever changed her and her outlook on the world. She wrote followup books, she remained socially aware and active. She taught multicultural and diversity college courses. She kept learning and teaching others about our racialized society up until her death in 2004. Her Education of a WASP has been and continues being used in ethnic stiudies courses around the country.

A WASP’s racial tightrope resulted in enduring book partially set in 1960s Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the November 2015 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

You’ve got to be taught to be afraid

Of people whose eyes are oddly made,

And people whose skin is a diff’rent shade,

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

When a liberal, white middle-class couple with young kids moved to Omaha from Chicago in the late 1950s they entered this city’s weirdly segregated reality, not uncommon in almost every American city. It was not as public or overtly violent as the segregation in the former Confederate states of the South, but it was no less impactful on the African-American communities in Northern states. Homemaker Lois Mark Stalvey was a former advertising copywriter who once owned her own agency. Her husband Bennett Stalvey was a Fairmont Foods Mad Man.

The Omaha they settled into abided by a de facto segregation that saw blacks confined to two delineated areas. The largest sector, the Near North Side, was bounded by Cuming on the south and Ames on the north and 16th on the east and 40th on the west. Large public housing projects were home to thousands of families. In South Omaha blacks were concentrated in and around projects near the packing plants. Blacks here could generally enter any public place – a glaring exception being the outdoor pool at Peony Park until protestors forced ownership’s hand – but were sometimes required to sit in separate sections or limited to drive-thru service and they most definitely faced closed housing opportunities and discriminatory hiring practices.

This now deceased couple encountered a country club racist culture that upheld a system designed to keep whites and blacks apart. Neither was good at taking things lying down or letting injustices pass unnoticed. But she was the more assertive and opinionated of the two. Indeed, son Ben Stalvey recalls her as “a force of nature” who “rarely takes no for an answer.”

“She was stubborn to accept the accepted norm in those days and that piqued her curiosity and she took it from there,” he says. “She had grown up in her own little bubble (in Milwaukee) and I think when she discovered racial prejudice and injustice her attitude was more like, What do you mean I can’t do that or what do you mean I have to think that way? It was more just a matter of, “Hell, no.”

Though only in Omaha a few years, Stalvey made her mark on the struggle for equality then raging in the civil rights movement.

The well-intentioned wife and mother entered the fray naive about her own white privilege and prejudice and the lengths to which the establishment would go to oppose desegregation and parity. Her headstrong efforts to do the right thing led to rude awakenings and harsh consequences. Intolerance, she learned here and in Philadelphia, where the Stalveys moved after her husband lost his job due to her activism, is insidious. All of which she wrote about in her much discussed 1970 book, The Education of a WASP.

The title refers to the self-discovery journey she made going from ignorance to enlightenment. Blacks who befriended her in Omaha and in Philadelphia schooled her on the discrimination they faced and on what was realistic for changing the status quo.

Among her primary instructors was the late black civic leader and noted physician Dr. Claude Organ and his wife Elizabeth “Betty” Organ and a young Ernie Chambers before his state senator career. In WASP Stalvey only sparingly used actual names. The Organs became the Bensons and Chambers became Marcus Garvey Moses.

A Marshall, Texas native and graduate of Xavier University in New Orleans, Claude Organ was accepted by the University of Texas Medical School but refused admittance when officials discovered he was black. The state of Texas paid the tuition difference between UT and any school a denied black attended. Organ ended up at Creighton University and the state of Texas paid the extra $2,000 to $3,000 a year the private Jesuit school cost, recalls Betty Organ.

His civil rights work here began with the interracial social action group the De Porres Club led by Father John Markoe. Organ became Urban League of Nebraska president and later advised the Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties (4CL). He was on the Catholic Interracial Council board and Mayor’s Biracial Committee.

“He built a lot of bridges,” son Paul Organ says.

Betty Organ got involved, too, supporting “any group that had something to do with making Omaha a better place to live,” she says.

So when Stalvey was introduced to the Organs by a black friend and determined to made them her guides in navigating the troubled racial waters, she couldn’t have found a better pair.

Stalvey met Chambers through Claude Organ.

Chambers says “This woman detected I was somebody who might have some things to offer that would help give her what she called her education. And when I became convinced she was genuine I was very open with her in terms of what I would talk to her about.”

Though it may not seem so now, Chambers says the book’s title was provocative for the time. WASP stands for White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, which defined Stalvey’s background, but racism was rampant across ethnic and religious lines in White America.

“WASP was a term that not everybody to whom it applied embraced. So by using that title she caught people’s attention.”

Ernie Chambers educating Pastor William Youngdahl in “A Time for Burning”

But he admired the “substance” behind the sensation. He admired, too, that the vitally curious Stalvey asked lots of questions.

“I never got the impression as used to happen when I was interviewed by white people that she was ‘studying’ me like a scientist in a lab would study insects. She genuinely was trying to make herself a better person and I think she succeeded.”

This ever apt pupil threw herself into The Cause. Her son Noah Stalvey says, “I can remember meetings at the house. She had a lot of the movers and shakers of the day meeting there. Her goal was to raise us in an environment of tolerance.”

“At times it was lively,” says Ben Stalvey. “There wasn’t much disagreement. We knew what was going on, we heard about things. We met a lot of people and we’d play with their kids.”

All par for the course at the family home in Omaha’s Rockbrook neighborhood. “It wasn’t until well into my teen years I realized my parents were fighting the battle,” Noah says. “I just thought that’s what all parents do.”

His mother headed the progressive Omaha Panel for American Women that advocated racial-religious understanding. The diverse panelists were all moms and the Organ and Stalvey kids sometimes accompanied their mothers to these community forums. Paul Organ believes the panelists wielded their greatest influence at home.

“On the surface all the men in the business community were against it.

Behind the scenes women were having these luncheons and meetings and I think in many homes around Omaha attitudes were changed over dinner after women came back from these events and shared the issues with their husbands. To me it was very interesting the women and the moms kind of bonded together because they all realized how it was affecting their children.”

Betty Organ agrees. “I don’t think the men were really impressed with what we were doing until they found out its repercussions concerning their children and the attitudes their children developed as they grew.”

Stalvey’s efforts were not only public but private. She personally tried opening doors for the aspirational Organs and their seven children to integrate her white bread suburban neighborhood. She felt the northeast Omaha bungalow the Organs occupied inadequate for a family of nine and certainly not befitting the family of a surgeon.

Racial segregation denied the successful professional and Creighton University instructor the opportunity for living anywhere outside what was widely accepted as Black Omaha – the area in North Omaha defined by realtors and other interests as the Near North Side ghetto.

“She had seen us when we lived in that small house on Paxton Boulevard,” Betty Organ says. “She had thought that was appalling that we should be living that many people in a small house like that.”

Cover of the book “Ahead of Their Time: The Story of the Omaha DePorres Club”

Despite the initial reluctance of the Organs, Stalvey’s efforts to find them a home in her neighborhood put her self-educating journey on a collision course with Omaha’s segregation and is central to the books’s storyline. Organ appreciated Stalvey going out on a limb.

Stalvey and others were also behind efforts to open doors for black educators at white schools, for employers to practice fair hiring and for realtors to abide by open housing laws. Stalvey found like-minded advocates in social worker-early childhood development champion Evie Zysman and the late social cause maven Susie Buffett. They were intent on getting the Organs accepted into mainstream circles.