Archive

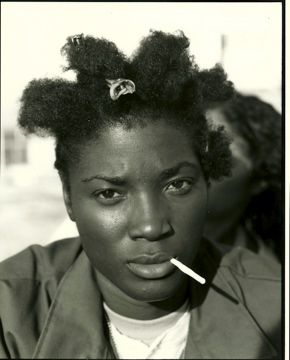

Daring actress Yolonda Ross takes it to the limit

Another example of a talented creative artist from Omaha is Yolonda Ross, a superb actress who left her hometown years ago for New York City, and she’s carved out a very nice career in film and television. The following profile for The Reader (www.thereader.com) gives a good sense for this adventurous actress, who also writes and directs. This story appeared in advance of her role in the controversial film Shortbus, one of my provocative projects she’s participated in. I am posting other pieces I’ve done on Yolonda as well.

NOTE: More recently, Yolonda’s had a recurring role as Dana Lyndsey on the acclaimed HBO drama Treme. Another Omaha actor of note, John Beasley, just nabbed a recurring role on the same series. Small world.

Some of the many faces and looks of Yolonda Ross:

Daring actress Yolonda Ross takes it to the limit

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Gabrielle Union gets all the pub, but another film/television actress from Omaha, the righteous Yolonda Ross, consistently does edgy material far afield from Bad Boys II and The Honeymooners. Ross has played everything from a wannabe gangsta desperate for love to a string of lesbian characters to a child molester to a porn actress. She’s worked with everyone from Woody Allen (Celebrity) to Denzel Washington (Antwone Fisher) to Don Cheadle (The United States of Leland) to Vanessa Williams (Dense and Allergic to Nuts).

Last fall, she worked on a Leonardo DiCaprio-produced film, The Gardener of Eden, and has been in discussions with such A-list artists as Cheadle for other parts. But it’s a project she wrapped last summer, Shortbus, that should grab her some attention. The notorious new feature by John Cameron Mitchell (Hedwig and the Angry Inch), a maker of queer cinema, deals with transient artists looking to connect through sex in the malaise of a post-9/11 Manhattan languishing from ever-present anxiety, commerce, inflation and exhibitionism.

Whether Shortbus ever makes it to Omaha is anyone’s guess. Most of Ross’s film work, which includes several shorts, doesn’t make it here. An exception is Dani and Alice, a 2005 short directed by Roberta Marie Munroe that’s screening at the Omaha Film Festival. The film deals with the rarely discussed problem of woman-on-woman partner abuse. Ross plays the femme victim Alice to butch lover Dani in an abusive relationship in its last hours. Dani and Alice shows March 25 at the Joslyn Art Museum’s Abbott Lecture Hall in the fest’s 9 p.m. short film block and Ross plans to attend and participate in an after-show Q & A. For details, check the event website at www.omahafilmfestival.org.

Difficult subjects are the Ross metier, which keeps her work from being widely seen. Her Shortbus director, John Cameron Mitchell, had trouble financing that pic because of his insistence on lensing non-simulated sex scenes.

“Yeah, that’s true, the not-simulated part,” Ross said. “That’s why it’s taken him so long to get money for the movie. People were scared to put money into it.”

Ross was originally put off by the idea of “doing it” on screen and perhaps jeopardizing her career by blurring the line between adult and mainstream cinema. Then, she changed her mind, and was even prepared to partner up again with an old flame for some celluloid enflagrante.

“At first, I was like, I’ll work on it, but I won’t do the sex part. Then, a year later, when John still didn’t have money for it I told him me and my ex-boyfriend would do it — because he needed couples. At that point I was like, If Chloe Sevigny could suck off Vincent Gallo (in The Brown Bunny), then I’m sure I could do it with my ex in a movie. Right?! I said I would do that based on my complete faith that John knew what he was doing and would do something amazing with it, and not use it in a disgraceful way.” As things turned out, Ross didn’t have to get down and dirty for the sake of her art. “Everything turned out cool. The actual couples are still in it. But when somebody fell out of another part, I was re-cast in a role that does not require me to have sex on camera,” she said.

In a film full of non-actors, she plays opposite JD (Samson) of Le Tigre and Suk Chin of Canadian News. She’s not telling who does what on screen. “Dude, you’ll have to watch the movie to know who does and who doesn’t have sex,” she said, laughing.

In the film, she’s the lesbian rocker, Faustus. She attends a women’s support group whose members talk through the politics and emotions of being gay in a straight world. Shortbus is the name of the fictional salon where the insecurities and idiosyncrasies of the characters, including Faustus, intersect. Some go for readings or performances. Others, for therapy. Still others, to engage in public sex. The salon culture portrayed in the film, where sex is a ritualistic and nihilistic acting out mechanism, is based on actual Manhattan salons.

Mitchell and Ross had wanted to collaborate for some time and the two actually hooked up last winter for a Bright Eyes video he directed and she appeared in.

“It’s really a nice thing working with John. He’s so good with people, whether they’re actors or non-actors. He’s great at bringing out the most in them,” she said. “He’s really good at making people feel confident and at ease, while staying on track with what he wants. I think he’s ridiculously talented.”

Ross follows her own clear vision in trying to elevate her career to the next level. She’s well aware, however, of Hollywood’s feckless ways. It’s why she’s taking matters in her own hands and pitching scripts she’s penned in the hope one sells and provides her with a tailor-made part. One of those scripts is serving as her directorial debut, for the comedy short Safe Sex she plans shooting. The story explores how sexual preferences, once exposed, tend to define people.

“Sex fascinates me. It makes people do really stupid things and act in ways they probably never do otherwise. It’s about a lot of mind stuff and what we see as wrong with sex. People have their fetishes or what have you, but you can’t really judge a person by what they get off to. Different things turn different people on.”

Bold themes and choices mark her work. In her best known role, as lesbian inmate Treasure Lee in Cheryl Dunye’s 2001 HBO original film, Stranger Inside, she endures the humiliation of a strip search early on and, in a later love scene, enjoys being pleasured by an inmate going down on her off-camera. In the comic fable Hung, she’s among several gay women to grow a penis. Each owner of the new appendage has her own ideas what to do with it.

In the feature Slippery Slope, pegged for a fall release, she’s a porn star named Ginger who initially struggles adjusting to the higher expectations of a legit director slumming in the world of skin flicks. “Ginger’s been in the business a little while,” Ross said of her character. “She’s a bit set in her ways. She kind of only knows one way to act. She resists learning something new and then she kind of embraces it. She gets into it, actually — the idea of making better pictures. And she starts making her own pictures. It’s nice that she’s not a one note character.”

With Shortbus, Ross once again pushes the envelope as one in a gallery of exotics. Exposing herself emotionally and physically in a part doesn’t intimidate her.

“I have no problem with being a taboo character or doing taboo things or anything like that,” she said. “As long as I can physically do them, I’m going to get up there and do it. I want you to forget it’s me. I want you to be lost in that character.”

Because Ross wants even fringe characters grounded in reality, she underplays what could be camp or superficial. “I like working subtly. The stuff that gets me is what happens behind the scenes and what people are really going through. Good, strong female characters that are real people,” she said. Not big on research, she relies instead on instinct and script preparation. “Know what you need to know, and then Iet the acting take over. I think what you need to be dead-on with are the emotions. That’s what makes me work better. If I know what my character thinks or feels in a situation, then that’s what makes me react in the right way.”

Her expressing the right emotion of a line is akin to when she sings jazz or blues, something she does purely for pleasure these days, but that she once did professionally in New York clubs. Music, she said, opened her up to acting, and she still uses it today to find the right notes and beats for her characters.

“When I started singing is when I understood the key of emotion. With every major character I’ve done there’s been music behind each one. From singing, I know there’s certain notes I hit or tones I make that, when I hear them, make me cry or make me feel some other way. Music can change my whole body and how I carry myself. If I’m listening to Ella, I’m not going to walk the same way I do as when I’m listening to Ray Charles. When I was doing Stranger Inside, there was a Marvin Gaye song, Distant Lover, in my head. OnShortbus, it was The Tindersticks’ Trouble Every Day soundtrack. Music keeps me relaxed or tense or whatever I need to be.”

In her early-30s, Ross is at a place in her career where she does a nice balance of little and big screen gigs capitalizing on her street smart persona, which finds her getting cast as beleaguered mothers, strung-out junkies, intense cops and bohemian types in episodic TV. But anyone who’s seen her work, such as her riveting turn in Stranger, knows she can play a full palette of colors and be everything from a hard-core case to a sweet, neurotic, vulnerable woman-child.

There’s a sense if she can just land one juicy part, she’ll be a major presence. Even if that doesn’t happen, she keeps adding to an already impressive body of work. Among her TV credits, are sketch comedy on Saturday Night Live, and high drama guest shots on 24, ER and Third Watch.

Part of why Ross hasn’t broken out big time in front of the camera, despite some heady props for Stranger and Fisher, has to do with the unsympathetic or peripheral roles she gets and the small indie projects she plays them in. One could argue that until now, while Gabrielle Union’s enjoyed the more successful commercial career, Ross’s has been more interesting. To be fair, though, Union has three films in the can that finally go beyond purely popcorn storylines and that for once hold out the promise of stretching her dramatic abilities.

But the point is Ross, an African-American contemporary of Union’s, has explored provocative subject matter for some time now without a fat pay-off. Union and Ross, who incidentally are fans of each other’s work, offer an interesting comparison. Each has defied the odds to carve out a nice career on screen. A key difference is perception. Union’s classic, wholesome beauty, with her smooth, soft features, put her up for positive roles and land her well-placed Neutrogena TV spots and endless glamour photo spreads in national mags. She comes across as sexy, brainy, full of attitude, but in purely non-threatening terms — as the love interest, friend or rival — and in widely accessible pictures, too.

By contrast, Ross’s unconventional but no less intriguing radiance has harder features, leaving her out of luck when it comes to girl-next-door or, for that matter, seductress roles. Spend any time with Ross, and it’s obvious she can play it all. She even does her share of glam, including a recent Bicardi Big Apple event in which she modeled an Escada gown. She’s a regular at New York premieres and other photo-op bashes. But in a town where they only know you by, What have you done lately? — perception, not reality, rules. Her performance in Stranger, a film/portrayal that became a cause celeb at feminist/lesbian festivals, was so on the mark, she’s been typecast ever since as a low down sista. In fact, she’s in high demand by women directors, whom she often works with.

Women confront stereotypes in the business, but Ross said black women must overcome even more. She said if you look closely, you’ll see that actresses with darker skin tones play “bad” while those with lighter skin shadings play “good.”

“Darker women are the cops, the crack heads, the hard asses. The darker the skin, the harder you’re going to be, the tougher you’re going to be. It’s very difficult for me to be seen as the cute girl next door or the nice mother or the love interest. I mean, it’s the craziest thing. Gabrielle’s about the same color I am, but she’s somewhat busted through,” said Ross, who surmises Union’s straight hair translates into less urban or ghetto in the minds’ of casting directors. “It’s about looks and name and face recognition. That’s what sells. Halle Berry can make bad movie after bad movie and have a Revlon contract. But why is it Angela Bassett isn’t working?”

Good women’s roles are hard to find, period, and even harder if you’re black. “Most scripts I read aren’t that good,” she said. “The characters don’t evolve.” Then there’s color-conscious casting that denies Ross, and even Union, a chance at roles deemed white or, God forbid, being part of an interracial romantic pairing.

That’s why Ross, who’s developed a working friendship with famed screenwriter Joan Tewksbury (Nashville) — “my second mother” — and Dani and Alice co-star Guinivere Turner, is trying to make something happen with projects she’s written alone or in collaboration. She despairs sometimes how fickle and slow the business is. “It drives me crazy. But I have to remember all the stories about other people where it took like 10-15 years to get something done. I know that the stories I have will have an affect on people. So, I keep that in mind.”

Until something breaks there, she’s waiting for start dates on two more features she’s cast in. Pearl City is a modern-day film noir set in Hawaii that lets Ross play sly as one of many potential suspects in a homicide investigation. Then there’s a new religious-themed film by Boaz Yakim (A Price Above Rubies).

Meanwhile, slated for a spring release is The Gardener of Eden. Directed by Kevin Connolly, the film co-stars Ross as one of many people crossing paths with a man so addicted to the props that come with being hailed a hero that he manipulates events to rescue others. The film also features Lukas Haas and Giovanni Ribisi.

Whatever comes next, Ross will take it to the limit.

Related articles

- [Movies] Shortbus (2006) (geeky-guide.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Yolonda Ross is a Talent to Watch (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Film Review: Shortbus (thenakedtruth69.wordpress.com)

Anthony Chisholm is in the house at the John Beasley Theater in Omaha

For a six-seven year period I devoted much time and energy to reporting on Omaha native John Beasley, a respected film, television, and stage actor and the director of his own namesake theater in his hometown. You’ll find on this blog several of the stories I did about John and his theater, including productions mounted there, and various guest artists who performed there. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader,com) is about one of those guest artists, actor Anthony Chisholm. My reporting about Beasley and his theater came to an abrupt end a few years ago when he took such strong exception to a review I wrote of one of his productions that it spoiled that particular beat for me. For all I know, he’s forgotten about the incident. But the verbal excoriation he gave me was so unsettling that I haven’t had the urge or the guts to contact him again, much less set foot in his theater. I did right by John and his theater for years, and he knows it, and so I do hope we can be friends again in the sense of my covering his work. The ironic thing is that that review was the only review I ever wrote – everything else was a feature or profile, and he never had any problem with those. Can’t we all just get along?

By the way, he’s picked up a recurring part in the HBO drama Treme and he hopes to have his recurring role in the NBC serio-comic series Harry’s Law continue. He continues to develop a feature film on Marlin Briscoe, the NFL’s first black quarterback.

Anthony Chisholm is in the house at the john Beasley Theater in Omaha

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Actor Anthony Chisholm, a great interpreter of the late August Wilson’s work, is in Omaha for the second time in three years at the invitation of the John Beasley Theater. Chisholm’s originated roles in several Wilson plays about the African-American experience. He was a close friend of the playwright.

Chisholm once played opposite JBT founder John Beasley in a regional theater production of Wilson’s Two Trains Running. A friendship was born. In 2004 Chisholm came here to be part of the ensemble cast for Wilson’s Jitney at the JBT. Now, fresh off a Tony nomination for his featured role in Wilson’s Radio Golf, Chisholm is back at the JBT in Athol Fugard’s Master Harold…and the Boys. The show opens October 26 and runs through November 18.

This marks the first time that Chisholm, a veteran of regional theater, off-Broadway, Broadway, television and film, has worked in a piece by the South African Fugard. Chisholm met Fugard through the late director and drama instructor Lloyd Richards, a key figure in each man’s life. Chisholm studied under Richards, who brought Fugard’s work to the States at the Yale School of Drama and on Broadway.

Chisholm, a resident of Montclair, N.J., was destined to be an actor from the time his mother, an unpublished poet and novelist, encouraged him to recite prose and verse as a child in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. A young Chisholm wowed family, friends and fellow congregants at East Mount Zion Baptist Church with his resonant bass voice and perfect diction.

“I remember my uncle Pete telling me that was my ‘calling.’ He said it in such a deep and placed way that that stuck somewhere back in me,” Chisholm said.

One of Chisholm’s favorite childhood haunts was the Karamu House, a social settlement offering arts and crafts, dance and theater. The Karamu House Theatre, whose notables have included Langston Hughes, Ruby Dee, Brock Peters, Ivan Dixon and Halle Berry, gained fame for its integrated productions.

Intent on an architectural career, Chisholm entered Case Western Reserve University. He waited tables at a posh Washington, D.C. nightclub, the Junkanoo, to earn enough so he could continue his studies. This was the mid-1960s. As the Vietnam War grew hotter and the draft loomed larger, Chisholm’s number came up and he landed in the U.S. Army. His commanding presence found him a drill sergeant — barking orders to a regiment of 1,500 old-timers.

While in uniform he won a dramatic reading contest that earned him a scholarship to Yale. He never used it. On a leave home he visited the Karamu and found himself shanghaied into a reading of Douglas Turner Ward’s A Day of Absence. Cast on the spot, he had to beg off due to his military commitment. But Chisholm recalled the director encouraging him by saying, “’When you get out of the Army you come back here — we’re going to get you started.’ And so it was.”

Not before Chisholm got his orders for Nam. He served as an M-60 gunner on an armored personnel carrier with the 4th Armored Calvary, 1st Infantry Division. He saw his share of firefights. He survived the shit and just six months after returning home he began doing rep at the Karamu. Things happened fast. Paramount Pictures came to Cleveland to shoot a feature, Up Tight!, and he was cast alongside Roscoe Lee Browne and Raymond St. Jacques. Seven more film roles came in short order, including a pair of cult classics — Putney Swope and Where’s Poppa?.

He’s continued to act on the small and big screen, including parts in Beloved and in the new Adam Sandler-Don Cheadle film, Reign Over Me, playing opposite Cicely Tyson. He’s also done many guest shots on episodic TV and played a recurring character, Burr Redding, in the acclaimed HBO series Oz. But he’s mainly a stage actor. As a young man he hooked up with the Negro Ensemble Company, where he studied under Richards in a master class. He’s gone on to act with such leading theaters as the Goodman and Steppenwolf in Chicago, the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles and the Seattle Repertory. Then there’s his association with August Wilson, whom he first met in 1990. He considers himself a disciple of Wilson’s.

“There was something very holy about him. He was a prophet-philosopher. He was just this very unusual individual. If you read his writing so many of the things he says in storyline, as characters speaking, are so philosophical and deep,” Chisholm said. Doing Wilson, he added, “has made me a beter actor without a doubt because working with well-written material brings out the best in you.”

An actor’s journey is all about discovery — about one’s self, one’s craft. It’s very much a life-long, self-taught process. “You teach yourself and you borrow from observation and every now and then you’re informed of something — an eye-opener,” Chisholm said. “So, yes, it’s always continuous.”

Arriving at the truth is the goal. It means being vulnerable and letting go.

“I know my own truth serum,” he said, “and if I don’t believe it, nobody else is going to believe it. Each role, as I move along, gets more truthful. You have to listen. I’ve been working on listening more. I don’t even think when I go out on stage or in front of the camera. I just throw myself out there. That’s a conditioning I’ve got to at this point, where I try to keep my head clear — a blank slate.

“I don’t care if I have a million lines, I don’t think about those words. As I observe and I feel, when it’s time to respond, it vomits out. The words will be there because I know the words back and forth. And that’s the way we are as people. Stuff comes out of us as we bounce things off one another.”

Related articles

- Polishing Gem: Behind the Scenes of the Beasley Theater & Workshop’s Staging of August Wilson’s ‘Gem of the Ocean ‘ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Ushers in New Era of Omaha Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Playwright/Director Glyn O’Malley, Measuring the Heartbeat of the American Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Playwright John Guare Talks Shop on Omaha Visit Celebrating His Acclaimed ‘Six Degrees of Separation’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- What Happens to a Dream Deferred? Beasley Theater Revisits Lorraine Hansberry’s ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Yolonda Ross is a Talent to Watch (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kevyn Morrow’s Homecoming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Crowns: Black Women and Their Hats (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Canceled FX boxing show, “Lights Out,” may still springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s career

As noted here before, storytellers are drawn to boxing for the rich drama and conflict inherent in the sport. So when I learned that Holt McCallany, star of the new FX series, Lights Out, spent a formative part of his youth in my hometown of Omaha and that his mother is singer Julie Wilson, a native Omahan, I naturally went after an interview with the actor, and setting it up proved unusually easy. In wake of the series’ cancellation, I know why. Producers and publicists were desperate to get the show all the good press they could but even though the show was almost universally praised by small and big media alike it never found enough of an audience to satisfy advertisers or the network. Because I enjoy charting the careers of Nebraskans who make their mark in the arts, particularly in cinema, I expect I will be writing more about McCallanay, who is a great interview, in the future. In addition to his television work, which between episodic dramas and made-for-TV movies is extensive, he has a fine tack record in features as well. I am also planning a piece on his mother, the noted cabaret artist Julie Wilson.

Canceled FX boxing show, “Lights Out,” may still springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s career

©By Leo Adam Biga

As published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Storytellers drawn to boxing’s inherent drama invariably find redemption at its soul and conflict as its heart.

Ring tales are on a roll thanks to Mark Wahlberg’s Oscar-winning film The Fighter and FX’s series, “Lights Out,” (the series finale airs next Tuesday, April 5 at 9 p.m.). Although FX recently announced it has decided not to renew the show for a second season, the show received favorable reviews from critics while generating more than usual interest locally, as it stars former home boy Holt McCallany in the breakout role of the fictitious Patrick “Lights” Leary, an ex-heavyweight champ attempting a comeback.

McCallany grew up in Omaha, the eldest of two rambunctious sons of Omaha native and legendary New York musical theater actress and cabaret singer Julie Wilson, and the late Irish American actor/producer Michael McAloney.

Like his hard knocks character, McCallany was truant and quick to fight. He was expelled from Creighton Prep. He says most of the “unsavory crew” he ran with outside school “wound up in jail.” At 14, he ran away from home — flush with the winnings from a poker game — to try to make it as an actor in Los Angeles.

“I was a very rebellious and a very ambitious kid,” he says.

In the spirit of second chances linking real life to fiction, he got some tough love at a boarding school in Ireland and returned to graduate from Prep in 1981, a year behind Alexander Payne, whom he hopes to work with in the future. McCallany, who’s returning to Omaha for his class’s 30th reunion in July, appreciates the school not giving up on him.

“I got kicked out but they eventually took me back, and they didn’t have to do that. Near my graduation I said to one of the priests, ‘Why did you guys take me back?’ and he said, ‘Because we believe in your talent, Holt. We see a lot of boys come through here and we believe you can be one of the first millionaires out of your class and a good alumnus.’ When you’re a kid you take that stuff to heart and it kind of stays with you, and if you believe it, other people will believe it about you, too.”

Tragedy struck when his troubled kid brother died at 26 in search of another fix. It’s a path Holt might have taken if not for finding his passion in acting.

“I felt like I had a calling. My brother didn’t have that, and my brother’s dead now, and I can tell you a lot of the pain and suffering he went through is related to this subject. When you don’t know what it is you want to be and you’re lost and you’re floundering and you’re going from job to job and kicking around and nothing really works out, it’s a very dispiriting place to be. It can lead to substance abuse and a lot of negative things.”

In the show, Leary’s a devoted husband and father trying to rise above boxing’s dirty compromises, but he and his younger brother get sullied in the process.

McCallany, who infuses Lights with his own mix of macho and sensitivity, is the proverbial “overnight sensation.” He’s spent 25 years as a journeyman working actor in film (Three Kings) and TV (Law & Order), mostly as a supporting player, all the while honing his craft — preparing for when opportunity knocked.

Everyone from co-star Stacy Keach, as his trainer-father, to series executive producer Warren Leight to McCallany himself says this is a part he was born to play. Why? Start with his passion for The Sweet Science.

“Boxing was my first love, and way back when I was a teenage boy in Omaha. My brother won the Golden Gloves. We had an explosive sort of relationship, he and I. We would often get into fistfights and all of a sudden he was getting really good.”

As for himself, McCallany’s a gym rat. He’s logged countless hours sparring — “sometimes those turn into real wars” — and training with pros. He appeared in the boxing pics Fight Club and Tyson. He’s steeped in boxing lore. He brought in his friend, world-class trainer Teddy Atlas, as technical adviser on Lights Out.

The pains taken to get things right have won the show high praise. The only critics who matter to McCallany are pugilists. “The response from the boxing community has been really positive,” he says.

“There are a lot of similarities I find between boxing and acting,” he says. “In the theater the curtain goes up at 8 and the audience is in their seats and you’ve got to come out and give a performance, and it’s similar in boxing — there’s an appointed day and appointed time when you know people are going to be there ringside and it’s time for you to come out and perform.”

In both arenas, nerves must be harnessed.

“The anxiety is your friend,” he says. “That’s what’s going to ensure you’re going to do what you’re trained to do and, as Ernest Hemingway said, ‘remain graceful under pressure,’ which is really what it’s about.”

As much as he admires great boxing films he says “Lights Out” is not constrained by the limits of biography or a two-hour framework.

“We have all of this time to explore in rich detail a boxer’s life and his relationships and his psychology,” he says. “With this character the writers and I have the freedom to really create and really see where this journey is going to take us, and that’s very exciting. I can’t tell you exactly what’s going to happen in season two because I’m not sure, and I promise you they’re not sure either. That’s what’s different.”

While they’ll be no second season now, McCallany’s up for a part in the nextBatman installment and has a script in play with

Related Articles

- Holt McCallany and Warren Leight Interview LIGHTS OUT (collider.com)

- Five Reasons to Watch Lights Out (seattlepi.com)

- ‘Lights Out’: A Total Knockout Of A Boxing Drama (npr.org)

- FX’s ‘Lights Out’ has more than punches to throw at viewers (latimesblogs.latimes.com)

- So long, “Lights Out” — you coulda been a contender (salon.com)

- Life is a Cabaret, the Anne Marie Kenny Story: From Omaha to Paris to Prague and Back to Omaha, with Love (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Home Girl Karrin Allyson Gets Her Jazz Thing On (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Home Boy Nicholas D’Agosto Makes Good on the Start ‘Election’ Gave Him; Nails Small But Showy Part in New Indie Flick ‘Dirty Girl’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Being Dick Cavett

The recent publication of Dick Cavett‘s new book, Talk Show: Confrontations, Pointed Commentary, and Off-Screen Secrets, is as good enough a reason as any for me to repost some of the Cavett stories I’ve written in the last few years. I’m also using the book’s release as an excuse to post some Cavett material I wrote that hasn’t appeared before on this blog. I’ve always admired this most adroit entertainer and I feel privileged that he’s granted me several interviews. With his new book out, I plan to interview him again. For me and a lot of Cavett admirers he’s never quite gotten the credit he deserves for raising the bar for talk shows, perhaps because almost no one followed his lead in making this television genre a forum for both serious and silly conversation. Cavett never quite caught on with the masses the way his talk-jock contemporaries did, and I’ve always thought it had something to do with his built-in contradiction of being both an egg-head and a stand-up comedian at the same time. The following story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) was based on a face-to-face interview I did with him in Lincoln, Neb. in 2009.

Being Dick Cavett

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in a 2009 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

While Johnny Carson’s ghost didn’t appear, visages of the Late Night King abounded in the lobby of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Temple Building.

Carson’s spirit was invoked during an Aug. 1 morning interview there with fellow Nebraska entertainer, Dick Cavett. That night Cavett did a program in its Howell Theatre recalling his own talk show days. Prompted by friend Ron Hull and excerpts from Cavett television interviews with show biz icons, the program found the urbane one doing what he does best — sharing witty observations.

The Manhattanphile’s appearance raised funds for the Nebraska Repertory Theatre housed in the Temple Building. The circa-1907 structure is purportedly haunted by a former dean. Who’s to say Carson, a UNL grad who cut his early chops there, doesn’t clatter around doing paranormal sketch comedy? His devotion to Nebraska was legendary. Only months before his 2005 passing he donated $5.4 million for renovations to the facility, whose primary academic program bears his name.

The salon-like lobby of the Johnny Carson School of Theatre & Film is filled with Carsonia. A wall displays framed magazines — Time, Life, Look — on whose covers the portrait of J.C., Carson, not Christ, graced. Reminders of his immense fame.

A kiosk features large prints of Carson hosting the Oscars and presiding over The Tonight Show, mugging it up with David Letterman. In one of these blow-ups Carson interviews Cavett, just a pair of Nebraska-boys-made-good-on-network-TV enjoying a moment of comedy nirvana together.

It’s only apt Cavett should do a program at a place that meant so much to Carson. They were friends. Johnny, his senior by some years, made it big first. He hired Cavett as a writer. They remained close even when Cavett turned competitor, though posing no real threat. Cavett was arguably the better interviewer. Carson, the better comic.

They shared a deep affection for Nebraska. Carson starred in an NBC special filmed in his hometown of Norfolk. He donated generously to Norfolk causes. Cavett’s road trips to the Sand Hills remain a favorite pastime. Though not an alum, he’s lent his voice to UNL, and he’s given his time and talent to other in-state institutions.

Looking dapper and fit, Panama hat titled jauntily, Tom Wolfe-style, the always erudite Cavett spoke with The Reader about Carson, his own talk show career, his work as a New York Times columnist/blogger, but mostly comedy. In two-plus hours he did dead-on impressions of Johnny, Fred Allen, Katharine Hepburn, Marlon Brando, Charles Laughton. His grave voice and withering satire, intact. He dropped more names and recounted more anecdotes than Rex Reed has had facelifts. Walking from the UNL campus to his hotel he recreated a W.C. Fields bit.

He’s so ingrained as a talking head Cavett’s comedy resume gets lost: writing for Jack Paar, Carson, Merv Griffin; doing standup at Greenwich Village clubs with Lenny Bruce; befriending Groucho Marx. He hosted more talk shows than Carson had wives. He’s had more material published than any comic of his generation.

On the native smarts comedy requires, Cavett said, “comedy is complete intelligence.” He said the best comics “may not be able to quote Proust (you can bet the Yale-educated Cavett can), but there’s an order of genius there that sets them apart. There aren’t very many stupid, inept, dumb comics. There are ones that aren’t very talented and there are the greatly talented, but the comic gift is a real rare order. It doesn’t qualify you to do anything else but that.”

Good material and talent go a long way, but he concedes intangibles like charisma count, too. He said, “Thousands of comics have wondered why Bob Hope was better than they are. What’s he got? I’ve got gags, too.”

For Cavett, “Lack of any humor is the most mysterious human trait. You wonder what life must be like.” He appreciates the arrogance/courage required to take a bare stage alone with the expectation of making people laugh.

“Oh, the presumption. It’s not so bad if the house isn’t bare but that has happened to me too at a club called the Upstairs at the Duplex in the Village, where many of us so to speak worked for free on Grove Street. A great motherly woman named Jan Wallman ran this upstairs-one-flight little club with about seven tables. Joan Rivers worked there. Rodney Dangerfield, Bob Klein, Linda Lavin. Woody (Allen) worked out some material there early on.”

He knows, too, the agony of bombing and that moment when you realize, “I have walked into the brightest lit part of the room and presumed to entertain and make people laugh and I’m doing apparently the opposite.” A comic in those straits is bound to ask, “What made me do this?” The key is not taking yourself too seriously.

“If you can get amused by it that will save you, and I finally got to that point at The Hungry Eye,” he said. “I knew something was wrong because I’d played there for two weeks and been doing alright and then one night, nothing, zero. The same sound there would be if there was no one seated in the place. Line after line. It was just awful. You could see people at the nearest tables gaping up at you like carp in a pool, not comprehending, not laughing, not moving. And I finally just said, ‘Why don’t you all just get the hell out of here?’ It gave me a wonderful feeling.

“Two, what Lenny Bruce used to call diesel dikes sitting in the front row with their boots up on the stage, one of whose boots I kicked off the stage, taking my life in my hands, got up to leave. And as they got to the door I said, ‘There are no refunds,’ and one of them said, ‘We’ll take a chance.’ And she got a laugh. So they (the audience) were capable of laughing.”

He finished his set sans applause, the only noise the patter of his patent leathers retreating. Inexplicably, he said, “the next show went fine. Same stuff.” For Cavett it’s proof “there is such a thing as a bad audience or a bad something — a gestalt, that makes a room full of unfunnyness, and I don’t think it’s you. It might be something in you. Whatever it is, you’re unaware of its source, not its presence.”

Anxiety is the performer’s companion. It heightens senses. It gets a manic edge on.

“Whether you want it, you’re going to get some,” he said. “I can go into a club and perform without any nerves of any kind now. But if it isn’t there you want a little something, and there are ways you can get it. Like be a little late. Or I found with low grade depression, before diagnosed, not knowing what it was, I would do things like go back and rebrush my hair or put another shirt on. ‘This is dangerous, they’re going to be mad,’ I’d think. ‘But that’s alright somehow.’ I didn’t realize the somehow meant it’s giving me adrenalin that lifted the depressed seratonin level. It raises you a little bit above the level of a normal person standing talking to other normal people. It’s a recent realization. I’ve never told that before.”

Cavett was always struck by how Carson, the consummate showman, was so uptight outside that arena. “I’ve said it before, but he was maybe the most socially uncomfortable man I’ve ever known. At such odds with his skills. There are actors who can play geniuses that aren’t very smart seemingly when you talk to them, but whatever it is is in there and it comes out when they work. I have a sad feeling Johnny was happiest when on stage, out in front of an audience. I don’t know that it’s so sad. Most people are sad a lot of the time, but some don’t ever get the thrill of having an ovation every time they appear.”

“It’s funny for me to think there are people on this earth who have never stood in front of an audience or been in a play or gotten a laugh,” he said.

People who say they nearly die of nerves speaking in public reminds him he once did, too. “I had the added problem of every time I spoke everybody turned and looked at me because of my voice. It was always low. If I heard one more time ‘the little fellow with the big voice’ I thought I’d kick someone in the crotch.”

He said performers most at home on stage dread “having to go back to life. For many of them that means the gin bottle on the dresser in a hotel in Detroit. On stage, god-like. Off-stage, miserable.”

In Cavett’s eyes, Carson was a master craftsman.

“He could do no wrong on stage. I mean in monologue. He perfected that to the point where failure succeeded. If a joke died he made it funnier by doing what’s known in the trade as bomb takes — stepping backwards a foot, loosening his tie…’” Not that Carson didn’t stumble. “He had awkward moments while he was out there. Many of them in the beginning. My God, the talk in the business was this guy isn’t making it, he’s not going to last. It’s hard to think of that now. Merv Griffin began in the daytime the same day as Johnny on The Tonight Show. Merv got all the good reviews. He was the guy they said should have Tonight, and Merv really died when he didn’t get it.”

When the mercurial Paar walked off Tonight in ’62 NBC scrambled for a replacement. Griffin “was actually seemingly in line” but the network anointed Carson, then best known as a game show host. In what proved a shrewd move Carson didn’t start right away. Instead, guest hosts filled in during what Cavett refers to as “the summer stock period between Paar and Johnny. People don’t remember that. Everybody and his dog who thought he could host a talk show came out and most of them found out they couldn’t.” Donald O’Connor, Dick Van Dyke, Jackie Leonard, Bob Cummings, Eva Gabor, Groucho. Some were serviceable, others a disaster.

Carson debuted months later to great anticipation and pressure. “At the beginning he was really uncomfortable, drinking a bit I think to ease the pain, and as one of my writer friends said, ‘with a wife on the ledge.’ It was a very, very hard time in his life to have all this happen” said Cavett, “and then he just developed and all this charm came out.”

Off-air is where Carson’s real problems lay. “Many a time I rescued him in the hall from tourists who accidentally cornered him on his way back to the dressing room after the show. They’d made the wrong turn to the elevators and decided to chat up Johnny, and he was just in agony.” The same scene played out at cocktail parties, where Carson hated the banter. It’s one of the ways the two were different. Said Cavett, “I don’t seek it but I don’t mind it. He couldn’t do it and he knew he couldn’t do it and it pained him.”

That vulnerability endeared Carson to Cavett. “I liked him so much. We had such a good thing going, Johnny and I. It dawned on me gradually how much he liked me. I mean, it was fine working for him and we got along well, and when I was doing an act at night he’d ask me how it went, and we’d laugh if a joke bombed. He’d say, ‘Why don’t you change it to this?’ He’d give me a better wording for it. I feel guilty for not seeing him the last 8 or 10 years of his life, though we spent evenings together. The staff couldn’t believe I ate at his house. ‘You were in the house?’ On the phone he was, ‘Richard’ — he always called me Richard, sort of nice — ‘you want to go to the Magic Castle?’ I’d say, ‘Who is this?’ ‘Johnny.’ And I would think somebody imitating him, even though I’d been around him a million times.”

Something Brando once told Cavett — “Because of Nebraska I feel a foolish kinship with you” — applied to Cavett and Carson.

Cavett realized a dream of hosting his own show in ’68 (ABC). In ’69 he went from prime time to late night. A writer supplied a favorite line: “‘Hi, I’m Dick Cavett, I have my own television show, and so all the girls that wouldn’t go out with me in high school — neyeah, neyeah, neyeah, neyeah, neyeah.’ It got one of the biggest laughs. Johnny liked it.”

Getting more than the usual canned ham from guests was a Cavett gift. Solid research helped.

“I often did too much. I’d worry, ‘Oh, God, I’m not going to get to the first, let alone the 12 things I wrote down. Or. ‘I’ve lost the thread again.’ Only to find often the best shows I did had nothing I’d prepared in it. The best advice I ever got, which Jack Paar gave me, was, ‘Kid, don’t ever do an interview, make conversation.’ That’s what Jack did.” A quick wit helps.

At its best TV Talk is a free-flowing seduction. For viewers it’s like peeking in on a private conversation. “Very much so,” he said. “You’d think that can’t be possible because there are lights and bystanders and an audience, and it’s being recorded, and yet I remember often a feeling of breakthrough, almost like clouds clearing. ‘We’re really talking here. I can say anything I want .’”

With superstar celebs like Hepburn, Bette Davis, Robert Mitchum, Orson Welles and his “favorite,” Groucho, Cavett revealed his fandom but grounded it with keen instincts and insights. “That did help. I could see on their faces sometimes, Oh, you knew that about me? I guess I have to confess to a knack of some sort that many people commented about: ‘How did you get me to say those things?’”

He said viewing the boxed-set DVDs of his conversations with Hollywood Greats and Rock Greats reveals “there was a time when nobody plugged anything” on TV. Then everyone became a pimp. “When first it happened it was rare. Then it was joked about,” he said, “and then it got so it was universal — that’s the reason you go on.”

Today’s new social media landscape has him “a bit baffled and bewildered.”

“I have wondered at times what all has changed, what’s so different. It did occur to me the other day looking at the Hollywood Greats DVD — who would be the 15 counterparts today of these people. I might be able to think of three. And that’s not just every generation thinks everything is better in the past than it is now. I know one thing you could start with is the single act that propelled me here — the fact I was able to enter the RCA Building via the 6th Ave. escalators, which were unguarded, and walk up knowing where Paar’s office was, and go to it.”

He not only found Paar but handed him jokes the star used that night on air, netting Cavett a staff writing job. “No career will start that way today,” he said. Then again, some creatives are being discovered via Facebook and YouTube.

In terms of the talk genre, he said, “it doesn’t mean as much to get a big name guest anymore. They’re cheap currency now,” whereas getting Hepburn and Brando “was unthinkable.” He’s dismayed by “how much crap” is on virtually every channel.” He disdains “wretched reality shows” and wonders “what it’s done to the mind or the image people have of themselves that allows them to think they’re still private in ways they’re not anymore.”

Comedy Central is a mixed bag in his opinion. “I like very little of the standup. I don’t see much good stuff. They all are interchangeable to me. They all hold the mike the same and they all say motherfucker the same. You just feel like I may have seen them before or I may not have. And I don’t believe in the old farts of comedy saying ‘we didn’t need to resort to filthy language’ and ‘they don’t even dress well.’ That’s boring, too.”

Cavett’s done “a kind of AARP comedy tour” with Bill Dana, Mort Sahl, Shelley Berman and Dick Gregory. “It was pretty good.” But he’s about more than comedy nostalgia. He enjoys contemporary topical comics Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert and Bill Maher, about whom he said, “he gives as good as he gets and gets as good as he gives.” He’s fine not having a TV forum anymore: “I’ve lived without it and I got what I wanted mostly I guess in so many ways.” Besides, who needs it when you’re a featured Times’ blogger?

“Yeah, I like that, although it can be penal servitude to meet a deadline.”

His commentaries range from reminiscences to takes on current events/figures. His writing’s smart, acerbic, whimsical, anecdotal. He enjoys the feedback his work elicits. “My God, they’re falling in love with Richard Burton,” he said of reader/viewer reactions to a ditty on the Mad Welshman’s charms. He covers Cheever-Updike to Sarah Palin. “My Palin piece broke the New York Times’ records for distributions, responses, forwarding. The two from that column most quoted about her: ‘She seems to have no first language’ and ‘I felt sorry for John McCain because he aimed low and missed.’ Many, many people extracted those two.”

He said Times Books wants to do a book of the columns.

When his handler came to say our allotted 90 minutes were up, he quipped, “Oh, God, it went by as if it were only 85.” And then, “I’ve got a show tonight but I said everything. Biga has had my best.” Before leaving he asked his picture be taken beside the Cavett-Carson repro. Two Kings of Comedy together again.

Related Articles

- Cavett’s Conversations: ‘When People Simply Talk’ (npr.org)

- Tamar Abrams: Dick Cavett: Get This Man a Show! (huffingtonpost.com)

- ‘Mel Brooks and Dick Cavett Together Again,’ Hour-Long Special Reuniting Comedy Greats Debuts Sept. 9 on HBO (tvbythenumbers.zap2it.com)

- “Looking at the Louds: A video supplement to ‘Cinema Verite’ and ‘An American Family'” and related posts (latimesblogs.latimes.com)

- The First Shall Be Last – Or, Anyway, Second (opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com)

Homecoming always sweet for Dick Cavett, the entertainment legend whose dreams of show biz Success were fired in Nebraska

In his new book, Talk Show: Confrontations, Pointed Commentary, and Off-Screen Secrets, irrepressible Dick Cavett reminds us that though he hasn’t hosted a talk show in a very long time he has much to say about this television genre, one he gave his own distinctive spin to as a writer and host. A wordsmith at heart, his new work also reminds us how gifted he is at turning a phrase. Because Cavett is making the rounds this fall and winter to promote his book, he is very much in the entertainment news again, which is why I am reposting a couple Cavett articles I wrote a few years ago and why I am posting for the first time some other Cavett material I wrote. He’s been very generous with me in terms of granting me ample time for my interviewing him over the years. To be honest, I didn’t even know about this book until a friend mentioned it. Now that I’m onto it, I will request a new interview with him and I know he will be accommodating again. As he likes to say, he’s always a good guest, and in this case, a good interview. The following piece, which traces his career, originally appeared in the New Horizons newspaper in Omaha, Neb.

Homecoming always sweet for Dick Cavett, the entertainment legend whose dreams of show biz success were fired in Nebraska

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horizons

Dick Cavett’s longing to be “under the lights” burned so hot as a boy in post-World War II Nebraska that nothing seemed more enticing than the prospect of far-off glamour in New York. Then, as now, the Big Apple loomed as the center of all things, certainly of show biz, which the young Cavett saw as his future.

“Always the shot of the New York skyline spoke to me where it didn’t to others my age,” the 70-year-old comic and former talk show host said by phone from his historic coastal retreat, Tick Hall, on Montauk, Long Island. The 19th-century, Stanford White-designed home is where Cavett and his late wife Carrie Nye spent time away from the tumult of New York. The house burned down in 1997 and over three years time the couple had it reconstructed to historic specifications, an epic project that is the subject of a documentary, From the Ashes.

The house hasn’t been the same since Nye died from cancer last July. She had a way of filling any room she was in with her bright spirit and hearty, Southern drawl-tinged laugh. She and Cavett were married 42 years.

Today, when not at the beach, he stays at the Manhattan apartment the couple shared. This son of career educators lives a life steeped in culture — books, the theater, films, fine dining. He writes letters and op-ed pieces. His ability to engage in literature, history, gossip, trivia and one-liners sets him apart from some entertainers. Words fascinate him. He loves finding just the right one with which to prick or prod or parry. Exposing grammatical errors is a hobby, nigh-compulsion.

Cavett, the forever puckish wit, was born in Gibbon, Neb. and raised in Grand Island and Lincoln. Precociously bright, he got laughs from an early age, when he’d surprise others with his large vocabulary, double entendres, confident delivery and deep voice. His humor’s never left him, not even in his grief. Since Nye’s death, however, he has grown more reflective than usual about his Nebraska upbringing and the close ties he’s kept here throughout his nearly half-century career.

Nebraska is where he came back only three months after Nye, a noted actress, passed. He headed out alone by car to its far western reaches, a road trip he’s made many times over the years as a kind of pilgrimage. When things get too oppressive back East, Nebraska is his escape. Here, away from the glare, the noise, the crowd, he can unwind and breath under the clear, open, quiet skies.

“Yeah, it is that in a way,” he said, “especially when I do almost my favorite thing in the world to do, which is get in a car and go out into the Sand Hills. I remember one great teacher I had in high school, after I had just been to the Sand Hills, said, ‘Oh, it’s just heaven. Aren’t you glad the tourists haven’t found it?’ A lot of the tourists wouldn’t dig it or get it. But the idea you could take the family car as I did and drive 416 miles on the 4th of July for however many hours and hours it took and see just four other cars on those old roads…,” he said, his golden voice trailing off, choked with the wonder of the memory.

When he’s back, he stops in on old friends like Dannebrog’s Roger Welsch, the folklorist-author, and Lincoln’s Ron Hull, the avuncular Nebraska Educational Television legend. He visits his stepmother, Dorcas, now 90 but still sharp as a whip.

“So I went up to our bedroom where my wife Linda had already gone to bed and said, ‘Uuuuuuuh, Linda…Dick Cavett says he’s going to come visit us sometime. ‘Did he say when?’ she said sleepily. ‘Yeah….in about five minutes.’ She never did forgive me…or Dick…for that one.”

Hull said Cavett’s affinity for Nebraska is “genuine. There’s not a phony bone in his body. He’s a very, very honest person.” Cavett often comes back at Hull’s request to emcee benefits or to lend his famous face and voice to a documentary or spot. “He’s never turned me down,” Hull said admiringly. “He’s a very generous guy. He’s always come through. And he’s always done it pro bono, just as a friend. He’s been a very good friend of Nebraska. That’s one of the things I like about him — he didn’t forget his roots. He is proud of those roots. He never lost touch with that.”

Whether at work in the studio or at play over dinner, Hull said Cavett’s “so much fun to be with. He is curious about everything. He listens. He has this marvelous, retentive mind. He’s so good at words. Don’t ever play Scrabble with him.”

“He is a pleasant soul,” Welsch said. “It’s hard not to like Cavett. His visits here are…definitely not an exercise in royalty visiting the peasants. Yes, he talks about Woody Allen and Mel Brooks…while I talk about my pal Bondo, the auto body repairman, or Dan the plumber, but somehow there isn’t a feeling of inequity. He appreciates the humor I find in ordinary people out here and in turn shows me the ordinary side of the notables in whom he finds his humor. I really don’t consider Dick Cavett to be a famous person who is a friend of mine; to us he is a friend…and oh yes, I guess he’s also famous. Perhaps the best part is that even as a world-famous star and intellect, he is still, through and through, a Nebraskan.”

Roger Welsch

Cavett’s love for the wide open spaces, solitude and history of Nebraska was implanted early on, via road trips his family made out West when he was a boy. Book, film and museum images of Plains Indians fixated him. As an adult he immersed himself more deeply in the land and legacy of its native peoples, familiarizing himself and the nation with the works of John Neihardt, Willa Cather and Mari Sandoz. He’s proud of the remarkable figures Nebraska’s produced and will name, without any prodding, some of the great film, theater, literary and athletic icons from here.

Whenever someone suggests there’s a characteristic that describes a typical Nebraskan, he’s quick to point out that personalities as diverse as William Jennings Bryan, Darryl Zanuck, Fred Astaire, Marlon Brando, Johnny Carson, Malcolm X, Sandy Dennis and Johnny Rodgers emerged from this same terra cotta.

For the book Eye on Cavett he wrote of returning a celeb to his Lincoln High class reunion. He and Welsch were classmates and bandmates, not buds. Cavett suspects Welsch thought he was “one of the fancy people.” Welsch confirms as much, but adds, “I admired him…He was always one of the stars at the talent shows, theater productions, and that kind of thing, and yet he was never an arrogant pain in the ass…just a nice guy who had a lot of talent.” They both coveted luminous Sandy Dennis, another classmate bound for fame, but neither had the guts to ask her out, much less speak to her. Cavett later got to know her in New York.

Nebraska is where Cavett’s heart is. New York’s where the action is. Even as a boy, he felt the pull of that place. How could it not beckon a starstruck kid like him? Especially after he nearly committed to memory the classic book, The Empire City, an anthology of great stories about New York by great writers.

“It’s just wonderful. Every famous writer who ever wrote anything about New York is in there,” he said, “from E.B. White to Groucho (Marx) to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ben Hecht. And I would read that thing and then read it again. I knew more about New York then, sitting on the glider on the porch reading that book than most New Yorkers did. I could describe Chinatown and how to get to it and around it and in it,” without having been there. In the book Cavett he co-authored with friend Christopher Porterfield the entertainer calls New York “a siren call.” Made all the more alluring by anecdotes of it told by his parents’ friends or the genuine New York actors he shared the stage with one season of summer stock in Lincoln.

For him, the future was a New York or bust deal. He wasn’t sure what path would take him there — “I had no idea how you got there” — but he knew his destiny lay in the crackle and glow of theater marquees, not the scraping of chairs on floors and chalk on backboards. His late parents, and stepmother, were all public school teachers and while he suspects he too would have excelled at it, he would be dissatisfied knowing he’d missed out on his dream.

“I think I could have enjoyed being a teacher a great deal,” he said. “They would have liked me. I would have been funny and all the things you didn’t associate with most teachers.” Like his dad. “My father was always the most popular teacher anyone in Lincoln ever had,” he said. “My father always attracted the most forlorn types…and made them feel better and gave them confidence and all these things. He gave them meaning. He didn’t mean to do that, but it just happened.”

One of those the elder Cavett tried reaching out to was the garbage man on their block, a young, sullen, self-made rebel named Charlie Starkweather, an obscure boy and striking name soon to strike fear on the Great Plains.

Cavett’s “toyed with the idea” of what might have been if he hadn’t left Nebraska. “Would I go nuts? Probably not. But I certainly wouldn’t have had what I wanted and at times got more than enough of later on. Let’s just say I can’t imagine contributing a covered dish to the picnic of the neighborhood,” he said dryly.

As “drawn” to show biz as he was, he said, “I can’t think of ever wanting anything else. It wasn’t as though, If I can’t become a comedian or a magician I’ll become a lawyer or a plumber and I’ll be happy doing that. Noooo…” That didn’t stop some from trying to dissuade him. “I didn’t have any interest in dental college, one of several things — it seems so humorous now — my father tried to interest me in. And of course his pitch was. ‘You’re talented, but you know a lot of people don’t make much of a living in your business, You really ought to think about something that’s going to be steady.’ I just nodded and let it pass.”

Once bit by the bug, no appeal to practicality could change his mind. “Yeah, because in effect you don’t really have any choice,” he said. “The thought of trying to go to law school was not even in question. I didn’t want to have anything to do with it.” The death of his mother from cancer when he was 10 only made him retreat more into the world of make believe. On the whole he counts his childhood a happy one, but the trauma of his mother’s death still stings.

“The worst part of that was not only watching her dying,” he said, “but no other kid I ever heard of lost a parent. Nobody.” He said his wife’s death made him relive the pain of his mother’s death and elicited “the resentment of, Screw this — I have to do it again? That was awful.”

There were also molestations he suffered at the hands of strangers, once at a Lincoln movie theater. He doubts the abuse triggered the depression he struggled with for many years, although he doesn’t discount the possibility.

But mostly he looks back fondly at a solid rearing. While his folks were far from bohemians, they were no squares, either. His mom and dad were intelligent, culturally astute people. As is his stepmother. His dad and step-mom co-founded a high brow social club, the C.A.s, whose name was a closely guarded secret. Critics Anonymous brought together a group of like-minded adults, plus Dick, for celebrations and excoriations of different subjects or themes. Sometimes, a country’s music, food, literature and customs came under scrutiny.

All the talk of exotic places only fueled his fire to see the larger world.

Like the boy who runs away with the circus, Cavett heeded the call of the lights, only gradually, in small measures. While growing up here he did some magic, some acting, some announcing. Even his favorite athletic pursuit, gymnastics, put him out front, under the lights. He studied the great comics, absorbing their stances, their inflections, their timing. His models were as near as Johnny Carson, then a popular magician on the Chautauqua circuit and, later, a dashing television-radio personality in Omaha, and as distant as the greats he glimpsed in the movies or on TV.

He once saw a young Johnny’s Great Carsoni act, and it left an impression. Perhaps, he thought, he could emulate a fellow Nebraskan’s success on stage. And once in awhile one of those bigger-than-life legends, as Bob Hope did, would come to perform in Lincoln or Omaha, giving him a first-person dose of show biz magic.

On those occasions, Cavett would, through sheer pluck, wend his way backstage before and after the show, something he continued doing once he finally made it to New York, becoming a habitue of the club-theater-network TV district, all the better to run into celebs. Just seeing Hope in the flesh was enough to feed his imagination and project himself into that rarefied company.

Besides Hope, long a hero of his, Cavett’s star gazing in Nebraska found him finagling seats and trading backstage banter with the likes of Charles Laughton, Basil Rathbone, Phil Silvers and Spike Jones. Each encounter only intoxicated him more with the idea that he belonged “in that world” with them.

Still, the stars were ethereal enough that even his “wildest dream could not convince me I would one day have Hope as a guest on my own show.” But he did.

After one of those head-in-the-cloud nights in Lincoln, enraptured by the sight of his idols and the exchange of a few words with them, his return to dreary Earth felt like defeat. “To go to school the next day was just murder,” he said. I thought, ‘I belong with them (the stars)’” as they set off by train for the next stop under the lights. Wanderlust ran in the family. His maternal grandfather was a Baptist preacher who immigrated from Wales and evangelized his way across the Great Plains. “My hell-for-leather Uncle Paul, as my father always called him,” was a rover who rode the freight rails. A young Cavett was captivated by their experiences of setting off for distant spots. “Oh, yeah, they had dramatic adventures in faraway places,” he said. “But I didn’t want to be T.E. Lawrence or Frank Buck. I didn’t see myself in jungles or deserts, though I’ve been to both…” He said he was like this character from a long-forgotten novel who startles her parents when they ask — ‘What do you want to be, a nurse or a school teacher?’ — by saying, and my wife used to quote this, ‘I want the fast cars, the bright lights and the men in tuxedos.’” Only substitute women in cocktail dresses for men in tuxes.

Cavett was spotted early on as a talent to be watched, even if he didn’t know exactly what talent might send him on his way. As a teen he acted in and eventually directed, too, a Lincoln Junior League Theater program, Storytime Playhouse, on popular radio station KFOR, the same station Carson used to launch his career. Cavett once did a 15-minute Macbeth.

“One day out on the street I run into Bob Johnson, who was of course this huge celebrity in Lincoln because he was a longtime announcer on KFOR. He did Bob Johnson’s Musical Clock and Bob Johnson’s this-and-that. We were both heading for the studio and he said, ‘Let’s walk around the block,’ as if he was about to bring up something sensitive and didn’t quite know how to. So we made small talk and then he said, ‘You know, Dick, I have a feeling about you — you’re going to get up and out of here the way Johnny did.’ And it was a poignant moment because it was a man in his middle age saying, I’m as far as I’m going to get and I faced up to that, but you and Johnny, well…

“I didn’t know what to make of it. I didn’t know what to say. I kind of hoped he was right, but I didn’t know how Johnny did. I can’t imagine what we said for the last half-block.”

Johnny was of course Johnny Carson. “Johnny was 10-12 years older than I was,” Cavett said. “He was doing his television show (The Squirrel’s Nest) in Omaha and soon going on to New York for various things, He hadn’t utterly ‘made it’ yet, but as far as anyone in Lincoln was concerned he had.” Cavett’s since wondered what might have happened if they had bumped into each other then to discuss their nascent show biz dreams. He’s sure they would have recognized in themselves then what kindred spirits they were.

As it was, they both made it big time, their careers following nearly parallel courses. Cavett was a talent coordinator and writer for Jack Paar’s Tonight Show, the slot Carson, who’d hosted TV game shows and written for Red Skelton, inherited when Paar retired. Carson made Tonight an even more popular and lucrative brand name for NBC. Cavett joined Carson’s staff of writers before getting his own talk show.

“I guess I just always had this sort of pull, as I think he (Carson) must have, to go where the action is. Mingle with Jack Benny and Bob Hope and Lucille Ball and maybe Groucho if you were really lucky.”

Cavett’s opportunity to leave Nebraska for the bright lights came courtesy of a family friend, another older man who saw in him the hunger and potential to excel.

“A friend of my parents by the name of Frank Rice taught at Omaha Central. Frank sort of looked like Vincent Price. He had a Whitney Fellowship, I think it was called, at Yale for a year. He came back and said, ‘Dick should apply at Yale.’ Nobody took this very seriously and Frank insisted. And somehow that came about.”

“I remember Frank saying, ‘You’ll like it at Yale, if you’re lucky enough to get in, because the Shubert Theatre is right across the street from your freshmen campus. Every week or two a new Broadway show comes through on its way to New York.’’ Broadway show? I didn’t even care it would cost me a dollar-forty to sit in the front row of the second balcony.”

This was it — his entree to the glimmer of New York theater and culture. If he could get in. And then one day, as he tells it, he was “on the same glider on the porch that I was probably readingThe Empire City on” when the mailman brought a letter from Yale that said, ‘You have been accepted in the Class of 1954.’ And the whole world just swam for a moment. ‘What will all this mean? God, what could happen from this? It’s hard to say. Damn near anything.’ I walked around in a daze.”

By the time he headed east he was a certified TV junkie, so much so he said that when his family got their first set in the mid-’50s “I did almost nothing but watch it. Sundays, my God, I got out graham crackers and peanut butter and started with ‘Super Circus, live from Chicago, and went all the way through the evening, including Mr. Peepers, What’s My Line?, Ed Sullivan, The Web…I made the mistake of getting a date once on a Saturday night and she did not want to watch Show of Shows, so that was the end of that relationship.

“When I thought of going away to college I wondered, Will they let me watch all my television?”

Yale let him have his catho ray tube fix, although with only one set in the dorm he couldn’t always watch his favorite shows. More importantly, New Haven, Conn. put him within easy reach of where it all happens. With such close access to New York, his idea of a good time was far different than most of his fellow red-blooded Yalies, who had scoring girls on their mind.

“Instead of going to girls schools on the weekends, Wellesley, Smith, Vassar, I went down to New York. I thought, How can you be so dumb as to want to go there when you can go to New York…see a play with the Lunts, Paul Muni or Bette Davis, and sneak into the Jackie Gleason Show and What’s My Line?,” a show he ended up guesting on.

As he did in Lincoln, he gushed to classmates about the stars and shows he saw and that he sometimes talked to. There were more all the time. Now that he was an Ivy Leaguer and a big city sophisticate, he wanted to go home “to parade around” in his Oxford blue shirt and tweed, three-button jacket from Saks and regale everyone with where he’d been and whom he’d seen.

“That was everything I’ve lived for — to come back and cause amazement,” he said. It was also a case of homesickness. But as he found nothing stays the same.

“My first trip from Yale back to Nebraska I couldn’t wait to get to Grand Island and as soon as I got around the corner to see where we used to live, it was gone,” he said. “There was a Safeway there. They had obliterated the Christian church, my best friend Mary Huston’s house, our house, the whole block. And it was one of the most devastating things that’s happened to me. How could they raze this without my permission? A horrible feeling. It hurts me right now.”

He was near finishing up Yale when walking on campus one day in 1957 he heard the news stand jockey hawking papers, Cavett recalled, with “the words ‘murder in Nebraska.” An incredulous Cavett remarked to the man, “It sounded like you said murder in Nebraska.” He confirmed he had. “There in the Journal American, now defunct, in big letters just short of what you put War Declared in, it said, ‘Ghastly Murders, Lincoln, Nebraska.” The headline referred to Charlie Starkweather’s killing spree. It gave Cavett the creeps.

“I don’t know now if I thought, I hope nobody I know was murdered. I guess you wouldn’t necessarily assume it. Had I known and glanced down at the name Starkweather I could have had a horrible moment recalling if my father said, ‘That’s our garbage guy.’ My father said he always seemed like a kind of forlorn kid. He seemed nice enough. My dad made people seem nice enough that weren’t anywhere but in his presence. Though I suppose I doubt if my father was anyone he toyed with as a victim.”

Even that incidental connection to a serial killer was enough for Cavett to closely follow the Starkweather manhunt, capture, trial and eventual execution.

By the time the notorious case became a sensation, Cavett was taking courses at Yale School of Drama and that’s when he met the woman who would become his life partner. Carrie Nye was her theatrical name but also her full first name. When Cavett met her her surname was McGeoy. She was flamboyantly Southern. Brilliant. Funny. Serious about her craft. Independent. Opinionated. An original.

The Greenwood, Miss. native attended Stephens College where, Cavett said, she “probably had the record number of violations there of books not returned, walking on the grass, smoking behind the lockers…”

His reaction upon first setting eyes on her? “I didn’t like her very much…I said ‘God, who the hell is that? She looks affected,’ or something like that to one of the guys at the drama school and he said, ‘But have you met her?’ I said, ‘No.’ When I did I saw what he meant. She was not like anything or anybody I ever met before. No one could ever say, ‘She’s just like Carrie Nye.’”

Dick with Carrie Nye

Their drama mates included, at one time or another, Paul Newman and Julie Harris. Cavett and Nye performed at Yale and in summer stock at Williamstown, Mass. They were soon an item, marrying in 1962. For a time, her career overshadowed his. When things broke for him, they broke big. Working for Paar, Carson, Jerry Lewis. Doing his own standup comedy act. Guesting on panel/game shows. Hosting his own late night network TV show, followed by TV desk-jock stints on PBS, then cable. Prime time specials. Commercials. Voice-overs. Films. Plays. She enjoyed success in regional theater and on Broadway, also taking occasional small and big screen parts. Their marriage survived the ups and downs of their respective careers.

It’s been awhile since Cavett’s had a talk-show gig. He laid to rest any question of whether he’s still “got it” with his 2000-2002 role as the narrator in the Broadway revival of The Rocky Horror Picture Show and his 2006 appearances on Turner Classic Movies, which revived some of his late night ABC shows with Hollywood greats. For a new TCM special he taped with Mel Brooks, Cavett proved his quick wit and verbal acuity are still intact. The Hollywood shows are out on DVD, as is a rock icon collection. A new DVD set featuring him with jazz-blues legends is planned.par

It’s interesting to note that even after all the dreaming he’d done of New York and all the trips he made there from New Haven to cozy up to the stars, Cavett still hadn’t made plans to move there after graduating Yale. He was doing summer stock when, he said, a fellow actor remarked, “‘Well, I guess you’ll be heading for New York, looking for an apartment.’ But to that point I hadn’t thought very far beyond the edge of the season. I really hadn’t thought it out. I figured I’d probably trip back to Nebraska. But as soon as I heard ‘you’ll be going to New York,’ I did.”

Cavett lived the life of a struggling young hopeful, making the rounds in casting offices, taking bit parts here and there, working all kinds of side jobs to keep himself alive. He was a copy boy atTime Magazine when he screwed up the nerve to go to the RCA Building with a batch of jokes he’d written for Paar, the king of late night. His plan? To somehow bump into the Great Man, slip him the material, and be discovered for the brilliant comic mind he is. Amazingly, it all came true.

Jack Paar

He still marvels at “the sheer chance of taking the monologue to Jack Paar,” running into him in a hallway, Paar accepting the envelope containing jokes penned by a unknown, then sitting back in the live studio audience to hear hisone-liners go out over the airwaves from the mouth of a star; and later, backstage being thanked by the star and encouraged to feed him more jokes. It all led to Cavett being hired on staff. The surreal experience was just one of “the phenomenal breaks, coincidences and other such things” that helped launch his career.

Cavett found his niche as a writer. “Once I get an idea I can go with it,” he said. “That was true as a monologue writer. If Jack or Johnny would give a subject, then I could be very fast and, to the irritation of the other writers, the first one to Johnny’s desk. Not that it mattered, because the first was not always the best.” He gets a high from writing that’s akin to the buzz he gets from ab libbing. Some, like old friend Ron Hull, suggest the entertainer could be a serious writer. “Yeah, I’m reasonably certain I could have made a living that way,” Cavett agrees.

While the two never talked about it, Cavett said he and Carson understood they shared a special connection. Like Carson did, Cavett’s given back to his home state.

He recalled one of the rare times the intensely private and supposedly cold Carson invited him out to dinner in L.A.

“That night we were sitting in a booth, just two guys from Nebraska in California, and he described the special (Johnny Goes Home) he’d just done in Norfolk and he said ‘there was this moment when I opened the door at the school building and there were all my teachers.’ And it was astounding because he was moved and he stuttered, and I thought, Oh, if people who think he has a ramrod up his ass and he treats people horribly could see this…He wasn’t a bit embarrassed by the emotion.

“He had a tremendous affection for me, and it took somebody to point it out. ‘Do you notice Johnny’s a different man when you’re on his show?’ one of his staff told me. ‘We wish you’d come on all the time. Johnny’s so easy to get along with when you’re on.’ It almost embarrassed me.”

Johnny’ gone. Cavett’s beloved Carrie Nye, a woman Ron Hull called “a perfect complement” to his friend, for her brilliance, humor and taste, is gone now, too, leaving “a void” no amount of quips can fill.

Given Cavett’s comic bent, her humor may be what he misses most. “The obit man at the Times spoke to me and said, ‘I feel I know your wife a bit,’ because he had talked to her twice on the phone about people who had died she had worked with, like Ruth Gordon. He said, ‘I remember those two conversations as the funnest experiences of my life and I wish I’d recorded them.’” To which Cavett can only concur, saying, “She was just vastly entertaining in the way nobody else was.”