Archive

From the Archives: Hadley Heavin sees no incongruity in being rodeo cowboy, concert classical guitarist, music educator and Vietnam combat vet

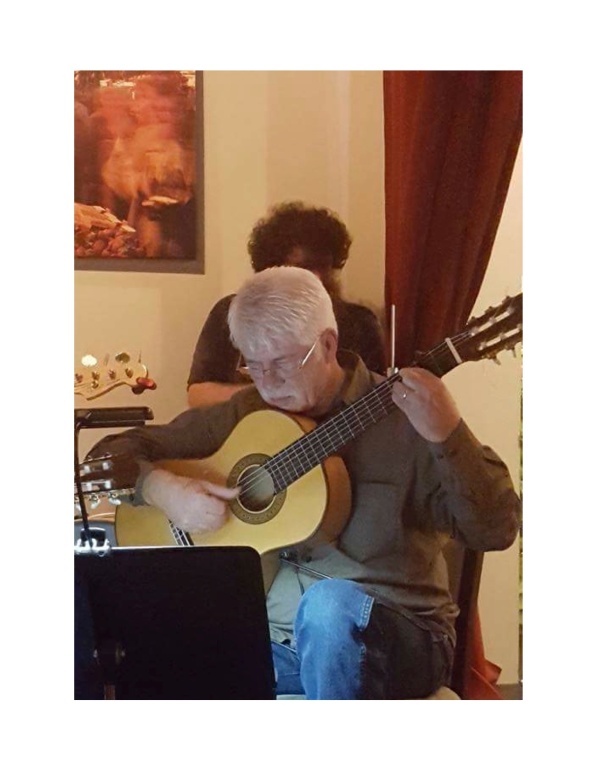

When I saw Hadely Heavin perform classical guitar at the Joslyn Art Museum in the late 1980s I knew I had to write about him one day, and in 1990 I sought him out as one of my first freelance profile subjects. I’ve culled that resuling story from my archives for you to read below. What I didn’t know when I interviewed him that first time is what a remarkable story he has. I mean, how many world-class classical guitarists are there that also compete in rodeo? How many are combat war veterans? What are the chances that an inexperienced American player (Heavin) would be selected by a Spanish master (Segundo Pastor) to become the maestro’s only student in Spain? I always knew I wanted to revisit Heavin’s story and nearly two decades later I did. That more recent and expansive portrait of Heavin can also be found on this blog, entitled, “Hadley Heavin’s Idiosyncratic Journey as a Real Rootin-Tootin, Classical Guitar Playing Cowboy.” When I wrote the original article posted here Heavin’s mentor, Segundo Pastor, was still alive. Pastor has since passed away but his influence will never leave the protege. Heavin was still doing some rodeoing as of three or four years ago, when I did the follow-up story, but even if he has completely given up the sport he’ll always do something with horses because his love for horses is just that deep in him. The same as music is. I hope you enjoy these pieces on this consumate artist and athlete.

From the Archives: Hadley Heavin sees no incongruity in being rodeo cowboy, concert classical guitarist, music educator and Vietnam combat ve

©by Leo Adam Biga

Orignally published in the Omaha Metro Update

Hadley Heavin defies pigeonholing, The 41-year-old Omaha resident is an internationally renowned classical guitarist, but to ranchers in rural Nebraska he’s better known as a good rodeo hand. The University of Nebraska at Omaha instructor’s life has been full of such seeming incongruities from the very start.

Back in his native Kansas Heavin is as likely to be remembered for being a precocious child musician as an expert bareback bronc rider, star high school athlete and Vietnam War veteran. Today, despite lofty success as a touring performer, Heavin is perhaps proudest of being a husband and new father. He and his wife, Melanie, became first-time parents last year when their girl, Kaitlin, was born.

Music, though, has been the one unifying force in his life. His earliest memories of the Ozarks are filled with gospel harmonies and jazz, ragtime and country rhythms. Home for the Heavin clan was Baxter Springs, Kan., five miles froom the Oklahoma and Missouri borders.

“Basically I grew up with music and I’ve been playing it since I was 5. My father was a jazz guitarist and always had bands,” said Heavin. adding that his late father played a spell with Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys.

Heavin hit the road with his old man at age 7, playing drums, trumpet and occasional guitar at dances and socials.

“I was a little freak because I could play really well. I loved it, but it got to be a chore. I remember about midnight I’d start falling asleep. My dad would start to feel the time dragging and see me nodding, then he’d flick me ont he head with his fingertip and wake me up, and I’d speed up again.

“Most of my fellow students at school didn’t know I was doing this. I didn’t think I was doing anything special because everyone in my family were musicians. I grew up in that environment thinking everybody was like this. I couldn’t believe it when a kid couldn’t sing or carry a tune or do something with music.”

When Heavin was all of 11 he started playing rock ‘n’ roll, an experience, he said, that left him burned out on music, especially rock.

“I’m glad I got burned out on that when I did because I’ve still got students in their 20s trying to study classical guitar and wanting to play rock ‘n’ roll. They want to have fun,” he said disparagingly. “They just don’t realize rock is not an art form in the same sense. Classical guitar requires a lot of work and soul searching.”

Heavin doesn’t mince words when it comes to music. Since he studied in Spain with maestro Segundo Pastor, he performs and teaches the traditional romantic repertoire that originated there. He feels the music is a deep. direct reflection of the Spanish people, with whom he feels a kinship.

“Spanish people are much warmer than Americans. We’re not brought up with the passion those people are brought up with. That’s why I prefer listening to European artists.”

He said classical guitar “demands” a passionate, expressive quality he finds lacking in most American guitarists with the exception of Christopher Parkening.

“Who a student studies with makes a big difference. I don’t think I ever would have played the way I do if I had never studied with Segundo.”

Heavin feels Pastor selected him as a student because he saw a hungry young musician with a burning passion.

“He wouldn’t have been interested if he didn’t see things in my playing that were like his. Frankly, he doesn’t like very many American guitarists. He thinks they’re very shallow performers.”

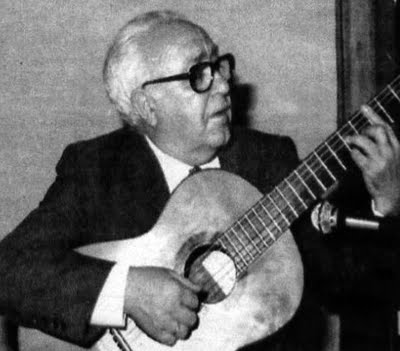

Segundo Pastor

The acolyte largely agrees, suggesting that part of the problem is most American musicians don’t face as many obstacles or endure as many sacrifices for their art as foreign musicians.

“My students are spoiled. How are they going to suffer for their art?” he asked rhetorically.

He said that when he turned to the classical guitar in the early ’70s, after seeing combat duty in Vietnam and having his father pass away, he knew what hard times were. “I suffered because by then my father was gone and my mother couldn’t support me. Somehow I played guitar and kept myself fed, but I didn’t have a penny, really, until I was 32. But I loved the guitar and I didn’t worry about those things. People are kind of unwilling to do that anymore.”

He dismissed the new guitarists who denigrate the traditional repertoire in favor of avant garde literature as mere technicians.

“I hate to say this but about all the concerts I’ve been to with the new guitarists have been very boring, driving audiences away from the guitar. It’s a real shame. They’re championing these avant garde works, which is fine, but they can’t play the Spanish and romantic repertoire at all. They just can’t phrase it. It’s not in them. They sound like they’re playing a typewriter.

“There’s a lot of great guitarists now, and they’re excellent technically, but there’s still only a handful of great musicians.”

He hopes artists like Parkening and Pastor help audiences “discern the guitarists from the musicians.”

It may surprise those who’ve seen Heavin perform with aplomb at Joslyn Art Museum’s Bagels and Bach series or some other concert venue that he as at ease on a horse as he is on a stage, as facile at roping a steer as he is at phrasing a chord, or as penetrating a critic of a rodeo hand’s technique as of a classical guitarist’s. But a look at his thick, powerful hands, deep chest and broad shoulders confirms this is a rugged man. And he does work out to stay in trim, including working with horses.

“As a matter of fact this is the first year I haven’t rodeoed in many years,” he said. “The only reason I’m not this summer is that I’m in the middle of doing an album and my producer’s worried about my losing a finger. I team rope now because I’m too old to ride rough stock. If I do get out of roping to protect my hands I’m probably going to have to do cutting or something just to stay on a horse. It’s just that horses are in my blood. But it’s tough with this kind of career because it takes so much time.”

Heavin has competed on the professional rodeo circuit all over Nebraska. “It’s funny,” he said. “I draw good crowds at my concerts in western Nebraska because I know all the ranchers and rodeo people, and they’re curious to see this classical guitarist who rodeos, too. I was playing a concert in Kearney and there were some roping friends in the audience. After I was done I went up and said to them, ‘These other people think I’m a guitarist, so don’t be telling them I’m a cowboy.’ But it was too late. They already had. I try not to advertise it too much.”

Heavin took to the rodeo as a boy to escape the music world he’d run dry on. “I started riding bulls and bareback broncs. I wanted to be a world champ bronc rider,” he said.. He rodeoed through high school and for a time in college. He also participated in football, wrestling and track as a prep athlete, winning honors and an athletic scholarship to Kansas University along the way.

“I think my dad put pressure on me to be an athlete to some degree because he wanted me to be well-rounded.”

At KU Heavin played on the same freshman football team as future NFL great John Riggins, a free-spirit known for his rebel ways. “I’ve never seen a guy that trouble came to so quickly. We used to go to bars and there was always a fight and John usually started it. He had more John Wayne in him than John Wayne.”

Another classmate and friend who became famous was Don Johnson, the actor. Heavin hasn’t seen the Miami Vice star in years but stays in touch with his folks in Kansas.

It was the late ’60s and Heavin, like so many young people then, was torn in different directions. “I decided I really didn’t want to be in school but I had the draft hanging over my head. I took a chance anyway and dropped out…and I was drafted within two months.”

The U.S. Army made him an artillary fire officer and shipped him off to Vietnam before he knew what hit him. He shuttled from one LZ to another, wherever it was hot. “I was what they called a bastard. I was with the 1st Field Force. I was in the jungle the whole time. I saw base camp twice during a year in-country,” he said.

Heavin was shot in action and after recovering from his wounds sent back out to the war. Luckily, his tour of duty ended without further injury and he finished his Army hitch back home at Fort Riley, Kansas. While stationed there he began missing working with horses and on a whim one day entered the bareback at a nearby rodeo.

“I drew a pretty rank horse, plus I hadn’t ridden in years and I was still sore from my war injuries. I got hurt. When I got back to the base they were mad at me because I couldn’t pull my duty. They were going to court-martial me.”

Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed and the incident was forgotten. “When I got out of the service my dad died shortly thereafter, and there was no music anymore.” Heavin had been working a job unloading trucks for two years when a friend suggested they see a classical guitarist perform. The experience rekindled his love for music.

“I was enthralled. And it just came over me like that,” he said, snapping his fingers. “That’s how fast I made my deicison to play classical guitar.”

Until then Heavin said he had never really heard classical guitar, much less played it. He began by teaching himself.

“I worked really hard. As soon as my hands could take it I was practicing six to eight hours a day and working a full-time job — just so I could get into college.”

Heavin brashly convinced the chairman of the Southwest Missouri State University music department to start a degreed classical guitar program for him. “I said, ‘Look, I want to get a degree in guitar and I’m determined to do it. And I don’t know why nobody has a program in this part of the country.’ He said, ‘I agree, let’s try this and see what happens.'” As the pioneering first student hell-bent on finishing the program, Heavin graduated and he said the program has “grown into something really nice and become very popular.”

His chance meeting with his mentor-to-be, Segundo Pastor, occurred at a concert in Springfield, Mo., at which Heavin was playing and the maestro was attending on one of his rare American visits. Heavin was introduced to “this little old man who couldn’t speak English” and arranged to see him later. He played for Pastor in private and the master liked the young man’s musicianship. The two began a correspondence.

When Pastor returned the next year he asked to see Heavin. “I spent practically a whole day with him and I played everything I knew. Then he said, ‘If you come to Spain I’ll teach you for nothing.’ I didn’t realize then what this meant or how it was going to work out,” Heavin said. A university official aided Heavin’s overseas studies. But the student still had no inkling his apprenticeship would turn out to be what he termed “one of the most wonderful experiences of my life.”

“When I arrive there was an apartment for me. The maestro’s wife was like my mom. His son was like my brother. And I realized only after I got there that I was his only student. He rarely takes them. There were Spanish boys waiting in line to study with him.”

Appropriately, the rodeoer lived a block from the Plaza de Toros, the bullfighting arena, and next door to the hospital for bullfighters.

“I lived in the culture. I wasn’t with Americans at all. My friends were all Spanish. I taught them English, they taught me Spanish. During the 10 months I was there I had a two-hour lesson from Segundo almost every day. He puts all of himself into that one student. That’s why he doesn’t take on many. It was really like a fairy-tale because the man literally gave me a career. The thing that’s odd about it is that I had only been playing about a year when the maestro invited me to Spain. It was confusing because there were Spanish boys who could play better than I.”

It was a question that nagged at Heavin for a long time. why me?

“The whole time I was in Spain I kept asking him, ‘Why did you pick me?’ and he would never answer it. The last night I was there he knocked on my door and we went to the university in Madrid. It was one of those romantic Spanish evenings. We were walking down a wet, cobblestone street and he put his arm on me and said, ‘Yeah, the Spanish boys are good guitarists but some day you’ll be a great guitarist,” recalled Heavin, still touched by the memory. “That gave me a lot of confidence to go on.”

During his stay abroad Heavin toured with Pastor throughout Spain, When the apprenticeship ended they performed duo concerts across the U.S., including New York’s Carnegie Hall. Heavin’s career was launched.

While the two haven’t performed publicly since then, Heavin said they remain close. “Now that I’m in the States he comes more often. When he visits we just have fun and enjoy ourselves. Two years ago he came with Pedro, a friend from Spain, and they did a duo concert here.”

Asked if in some way Pastor replaced his father, with whom he was so close, and Heavin said, “Oh yes. He’s like my father, no doubt. He’s my mentor, too.”

After earning a master’s degree at the University of Denver Heavin came to UNO in 1982. He heads the school’s classical guitar program, which he said is a good one. “I’ve got some students who play very well.”

Besides teaching Heavin performs 25-30 concerts a year, a schedule he’s cut back in 1990 to work on his first album.

“I’ve just finished doing the research on the pieces I want to put on. Now I’m learning the pieces. I’ll probably go into the recording studio in October or November,” he said.

As with Pastor singling him out for the chance of a lifetime, a patron has discovered Heavin and is helping sponsor him. “Another fairy-tale happened. A stockbroker heard me play and thinks I should have lots more recognition. He wants to get involved in my career.”

The guitarist is looking forward to touring more once the album is done. He has been invited to perform in Australia and Pastor has asked him to do concerts in Spain.

“People ask me why I live in Omaha and not on the coast,” he said. “I dearly love Omaha. I love the Old Market. I don’t like huge cities.”

Heavin, who practices his art about five hours daily, said success has little to do with locale anyway. “It’s an attitude. To do anything well requires an aggressive attitude. You have to just want to, and I’ve always done well financially playing guitar and teaching.”

Related articles

- Journey Through Latin America with Classical Guitarist Michael Anthony Nigro (worldculturesaustin.com)

- From the Archives: Cowboy-turned Scholar Discovers Kinship with 19th Century Expedition Explorer (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

John Sorensen’s decades-long magnificent obsession with the Abbott sisters bears fruit in slew of new works, Including “The Quilted Conscience” documentary at Film Streams

John Sorensen epitomizes a subject whose magnificent obsession, in this case for social work pioneers Grace and Edith Abbott, inspires me to want to write about him and his passion. This blog contains an in-depth story I did a couple years ago about John and his various Abbott projects. The following short piece for The Reader (www.thereader.com) encapsulates his fascination with the sisters, particularly Grace, and previews his documentary film about a quilt project with strong connections to the Abbotts‘ advocacy for immigrant women and children. John’s film lovingly details a group of Sudanese-American girls making a story quilt that expresses their dreams and memories. The quilt project is a metaphor for the loss of one way of life and the adoption of another way of life as the Sudanese, like other newcomers in the great march of immigration and refugee resettlement in American history, become part of the rich tapestry and fabric of America.

John Sorensen’s decades-long magnificent obsession with the Abbott sisters bears fruit in slew of new works, including “The Quilted Conscience” documentary at Film Streams

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to be published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

John Sorensen is like many Nebraska creatives who left to pursue a passion.

The Grand Island native and longtime New York City resident worked with master filmmaker Alexander MacKendrick (The Sweet Smell of Success) and Broadway legends Lewis and Jay Presson Allen (Tru). He founded a New York theater troupe. He’s developed a radio series. He’s written-edited books and study guides.

What sets him apart is a two-decade venture combining all those mediums. The Abbott Sisters Project is his multi-media magnificent obsession with deceased siblings, proto-feminists and early 20th century social work pioneers, Grace and Edith Abbott, from Grand Island.

As Abbott champions, Sorensen and University of Nebraska at Omaha professor Ann Coyne were instrumental in getting the school last fall to rename its social work unit the Grace Abbott School of Social Work.

John Sorensen with bronze bust of Grace Abbott

Sorensen has found a saga of strong, visionary women engaged in social action. These early Suffragists and University of Nebraska-Lincoln graduates were part of the Progressive wave that sought to reform the Industrial Age’s myriad social ills.

They trained under Jane Addams at Hull House, they taught at universities, they widely published their views, they advised Congress and sitting presidents and served on prestigious boards, all in helping shape policy to protect immigrants, women and children. Much feted during their lives, the sisters are arguably the most influential Omaha women of all time. The pair remained close, often consulting each other.

“I think from an early age, the sisters recognized they were each somehow mysteriously made whole by the other — that together they could learn things, experience things and do things impossible for either on her own,” says Sorensen.

His latest Abbott work is a documentary, The Quilted Conscience. He wrote, produced and directed it. A 7 p.m. free preview screening is set Thursday, October 6 at Film Streams.

The doc follows a group of Sudanese girls in Grand Island making a story quilt with the help of master quilter Peggie Hartwell and the town’s local quilters guild. The resulting story-blocks illustrate the African home the girls’ families left and the American home they’ve adopted. The quilt expresses the girls’ memories and dreams for the future. Sorensen seamlessly interweaves Grace Abbott’s minority rights advocacy with the girls’ cross-cultural experience to create a rich, affecting tapestry full of dislocation and integration, loss and hope.

A Q & A with Sorensen and some of the girls follows the screening. The “Dreams and Memories” story quilt the girls completed will be on display. The film is expected to eventually air on public television.

Grand Island public school teacher Tracy Morrow, whose students worked on the story quilt, says, “For many of the girls it has been a life-changing experience. They put so much work into it. I feel like John’s … educating the Grand Island community about the Sudanese and educating the Sudanese about Grand Island and America.”

As Grand Island connects Sorensen to the Abbotts, his project is allied with the public schools and library. The city’s refugee population is living context for applying Abbott values.

Sorensen has promoted the Abbotts for years, but it’s only recently his efforts have borne fruit. The story quilt has toured the state. He’s formed a immigrant-student quilt workshop. He co-edited The Grace Abbott Reader and helped get Edith’s memoir published posthumously. The sisters’ accomplishments are told in a new children’s book. The Grand Island Independent sponsors an Abbott scholarship.

All of it affirms that his epic odyssey to bring the Abbotts to the masses has been worth it. Even when his efforts gained little traction, he persisted.

“I just did whatever I could to keep transforming it and keeping it in people’s faces,” he says. “I could see I was having success in raising awareness — that people were slowly getting to know around the state who these women were. And that this more than the study of people from 100 years ago; this is the study about things that can help us to live better today.”

His devotion to the Abbott legacy is complete.

“I simply love the sisters,” he says. “I also admire their work for children and women and immigrants, and I feel a family-like connection and perhaps responsibility to them from sharing a hometown. I could no more turn my back on them, their legacy and their story than I could my own family. That love, that sense of faith is unconquerable.”

Even though he didn’t intend making it his life’s work, he’s grateful his Johnny Appleseed project is finally sprouting.

“It’s become clear in the last three or four years that it has no end for me. It’s become so embedded in my existence that I can’t stop — also because now it’s actually starting to unfold.”

Sorensen, who “never felt at home” growing up in Grand Island, is today a celebrated favorite son for his project’s rediscovery of two town legends. It feels like “a kind of destiny,” he says.

Seating is limited for the free Quilted Conscience screening. Reservations are recommended and may be made by emailing maggie@filmstreams.org or visiting the theater box office, 1340 Mike Fahey Drive. For more details, call 402-933-0259 or visit http://www.filmstreams.org.

Related articles

- A Stitch in Time Builds A World Class Quilt Collection and Center-Museum (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Short story writer James Reed at work in the literary fields of the imagination

James Reed of Omaha is one of those superb writers who goes under the radar of the general reading public because he specializes in short fiction that gets published in serious but sparsley read literary journals and anthologies, but he deserves a much wider following. I wrote this piece about James for The Reader (www.thereader.com) some 12 years ago, when he was still teaching at the University of Nebraska at Omaha and editing its literary magazine. I first met James at UNO, where we were students about the same time. I ran the campus film series and he and his then girlfriend and now wife, Omaah Central High School teacher Vicki Deniston Reed, were regulars at our screenings of classic and contemporary American and foreign films. Like most writers, James has always worked a regular job to support his writing habit. Highly respected in the field, James has received the National Endowment for the Arts‘ prestigious Charles B. Wood Award for Distinguished Writing from Carolina Quarterly and and Individual Fellowship Master Award in Literature from the Nebraska Arts Council. His work has been a finalist in competitions for the Spokane Prize for Short Fiction, the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction and the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, and the Southern California Review Fiction Prize. His work was a semi-finalist for the St. Lawrence Book Award.

James is a sweet man with a huge talent, and it’s safe to say that the vast majority of customers he waits on at the copy center he works at don’t have a clue he is one of the best living writers in the world. He’s far too humble to toot his own horn, so let me do it for him.

Short story writer James Reed at work in the literary fields of the imagination

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

“The clocks were faced with gold. Real gold. It dazzled the eyes. Houses might be black and white and as big as barns, with long slate roofs as if to weight them into the earth, but the clock towers shone like sunlight…They could be seen for miles. Towers, steeples, clocks, and inside the cathedrals, the walls seethed with gleaming saints. Angels older than America clawed toward heaven with empty, shimmering eyes.”

-from James Reed’s “The Time in Central Europe”

James Reed hears the music in words.

An award-winning short fiction author and accomplished amateur musician, the 45-year-old Omahan routinely reads aloud his work to better catch the beats, measures, tones resonating in the prose. While hardly an unusual practice among writers, Reed’s highly developed musical sense (he is a clarinet player with the Nebraska Wind Symphony and Black Woods Wind Ensemble) makes him more attuned than most to the lyrical notes of a descriptive passage, an alliterative phrase, a sly metaphor, an active verb. For him, it’s all about maintaining and tweaking, where needed, the voice he’s chosen (or that’s chosen him) to tell a story. Like a composer, he gets the rhythm down until every chord, every inflection, every transition flows seamlessly into a unified whole.

How does Reed, a creative writing instructor in the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Writers’ Workshop as well as fiction and managing editor of its literary magazine, The Nebraska Review, know when he’s reached the desired pitch?

“It sounds right,” he said in between swigs of coffee during a sit-down chat at the cluttered Review office in the Weber Fine Arts Building on the UNO campus. “I’m very aural…very attentive to sound and rhythm. I’m very voice-driven. I try to have a different voice for every piece and that pretty much is the guiding force. Whatever voice I’m using, whether it’s very formal or highly colloquial or a very flat uninflected voice, I always want it be settled. Is it working the way it should? Is it dead-on consistent? And if it doesn’t need to be consistent, when it moves do you believe the chord changes, the modulations?”

An example of a story where, as Reed puts it, “the voice ran the show” is “The Natural Order,” a morbid tale with a lonely, embittered old widow, Gwendolyn, as its gloomy narrator. Having lost everything dear to her, she sees her own sad end approaching in a neighborhood gone to the dogs:

“In the distance I hear woodchippers, the big industrial kind, and soon they’ll come down this street. Whole trees are being mulched. Most of them have been dead for years, and the neighborhood’s looking blighted. I’m afraid the city will just decide to make it official. Mr. Krendler’s old house already has been condemned…After Mr. Krendler died the place was rented to…maybe a psychotic, I think. He didn’t last long. I wouldn’t doubt he’s locked up or dead, the way he treated Mrs. Vacanti’s dog. I hated it too, the yappy little thing…but that young man twisted its head until he broke its neck…It was a noisy ball of fluff, but most of the dogs here are bigger. There’s one that looks like a horse…I’ve cleaned up uncounted messes from my yard…but the city wouldn’t listen. They just help who they want.”

According to Reed, “One day I wrote that opening sentence about woodchippers, ‘the big industrial kind,’ and from that moment on I had the voice I wanted. The more I wrote her (Gwendolyn), the more that voice made sense to me.”

Being true to the music of language is one thing, but just how Reed’s musicianship feeds his prose is somewhat ethereal. Experience has taught him not to discount it though.

He explains, “After college there was a period when I wasn’t playing (music) and I discovered I also wasn’t writing much. And when I finally picked up the horn I found myself writing again, so there’s obviously some link there. I write and read the way I do I believe largely because of the way I hear music generally, but particularly composers like Stravinsky and Mingus, whose work is dense complex stuff that leaps at a moment’s notice. Very complicated voicing. Enormous range of notes. How I hear fiction is very much a rhythmic mental sense of chord structure and of consonants and vowels colliding. That’s what I’m always trying to do — make it sound right. And some things never sound right to you.”

The discipline of practicing music daily as a youth, when he and his younger brother took horn lessons, steeled him for the rigors of writing every day. “For someone who’s going to be doing a very solitary job like being a writer, being a musician is great training because you spend hours and hours and hours by yourself mastering tasks. Like writing, it’s an extremely focused activity. I’m very good about writing even if I’m not in the mood. I highly recommend that. In class I tell students to think of this as your job. Some days on your job you’re great. Some days you’re just walking through the motions. The important thing is the process of doing it. If you don’t sit down and make yourself do it, it won’t happen. It just won’t.”

He works from a congested second-story office in the well-rummaged old clapboard house he shares with his wife Vicki Deniston Reed, a Central High School teacher, and their two young children, Anna and Jake. The small room, with stacks of books bulging from shelves and littering the floor, overlooks one side of Cascio’s Steak house and contains two desks, one for writing in long-hand,the other for his Mac computer. Within easy reach are his two horns — a B-flat and an alto clarinet.

Reed is a man of contrasts. He navigates the academic-aesthetic world while holding down a blue-collar printing job (something he’s done for years). He wears the utilitarian clothes and unpretentious demeanor of a working stiff, but his sonorous voice and capacious vocabulary clearly belong to the classroom or stage.

Among the discordant strains Reed or any writer must face is the rejection notice. You know the kind: ‘Thank you for the opportunity of reading your manuscript, but unfortunately at this time it does not meet our needs…blah, blah, blah…yadda, yadda, yadda.’ He’s heard them all before. To give aspiring writers a sober dose of reality or perhaps let them thumb their collective nose at the Philistines making publishing decisions, he’s affixed a collage of rejection notes to his UNO office window.

Getting stories published can take years. Some never see the light of day. Several Reed stories have appeared in major literary magazines (West Branch, Whetstone, River Styx, Tennessee Quarterly), but for every acceptance there’s far more turn-downs. So it goes. Undaunted by writing’s vagaries, he pursues a singular vision. His work has garnered attention though. One of his two collections, “The East Coast of Nebraska,” has been a finalist for top American literary prizes — the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction. While neither this collection nor his other (“Insulting the Flesh”) has found a publisher yet, he takes the attitude it’s only a matter of time before they do sell.

Meanwhile, he’ll go on trusting his inner voice. It’s served him well thus far. He’s won writing awards from the General Electric Foundation, Creighton University, Carolina Quarterly and the Nebraska Arts Council. Not bad for someone who fell into writing shortly after he and his family moved to Omaha from his birthplace of Minneapolis in 1973. A 1979 cum laude graduate of UNO’s Fine Arts College, Reed then promptly left academia behind. Years passed. Then, in 1990, he returned as fiction editor of the Nebraska Review and at the urging of poetry editor Susan Aizenberg pursued post-graduate studies, earning a master of fine arts degree at Warren Wilson College in N.C. in 1995. In the two-year Warren Wilson program he discovered a passion for teaching and gained a rigorous analytical approach to writing.

“It gave me a way of working with students to break down things into ever smaller component parts and still have it be comprehensible enough to deal with the overall architecture of the piece. Teaching I like because get to watch students light up and figure it out and take themselves to a place where they wouldn’t probably have been before, and that’s enormously rewarding.”

He’s especially grateful to former Warren Wilson instructor Karen Brennan for pushing him to refine his work. “I tend not to be very fond of rewriting. She beat into me, against all of my impulses, the real necessity of being an attentive rewriter and being ever vigilant and ever willing not to settle just because you’re tired. I owe her a lot for that because I think I’m a better writer as a result.”

Additionally, Reed credits UNO Writers’ Workshop founder and director, author Richard Duggin, for his development. “Absolutely. I ran into him early and young. I learned more from him about how to think about writing than probably anybody. I owe him, and many other people owe him, an enormous debt for his being endlessly, tirelessly helpful and instructive.”

James Reed

In turn, Duggin says he admires Reed’s “particular attention to small details that authenticate the story, his eye to finding the appropriate image and his meticulous attention to character development,” adding, “To me, James’ stuff represents some of the best work being done in Midwest literature.” Noting the musicality of his prose, he also appreciates Reed’s “attention to the rhythms of the language.”

Reed’s sonata-like stories unfold in episodic turns, each taking the measure of characters and incidents in small incremental movements that variously diverge from and merge with the main theme until the whole is great than the sum of its parts. He is fond of constructing lattice-work layers of digression and subtext.

“I love details. I will cram stories full of details. Early on in my fiction I picked up on a military defense theory, of all things, called Dense-Pack. The notion goes that you can have so much stuff densely clustered in different places and have it be so mobile that it’s difficult to destroy. And I think of my own fiction as essentially Dense-Pack stuff. I mean it’s just loaded, as somebody once told me, with lots of bits of dead-end pipe. I’m not as concise a short story writer as I probably should be, but I like the sound of things to be a little busier than that.

“Even though my plots tend to be kind of wandering, I will construct elaborately baroque things. One thing I do is mess with your time sense. My structure tends not to be a straight-line, linear, chronological development. In some ways I think I’m trying to do in short fiction a lot of the things people do in novels.”

While conscious his dead-end wanderings are not always neatly resolved, these very detours help bring Reed’s explorations of human foibles, conflicts and passions to life. He delves into the private often dark thoughts, personality tics, quirky behaviors and strained relations of “average” people in “ordinary” straits, revealing an extraordinary panorama of social-emotional-psychic baggage along the way.

“I like fiction with lots of people in it and I like the people in my fiction to be interesting. But it’s not like I have people fanatically happy or in love in my stories — often they’re ferociously not.”

Brooding characters are abundant in “The Downside,” a story set in a law firm whose soul-killing politics and pressures drive an attorney into a downward spiral. For it, Reed drew on his years working in the printing office of Kutak-Rock. Reed, who views the world of work as a rich but largely ignored vein of material, says it’s surprising “how much real hatred there is among people” at jobs.

Conceding “I can be dark,” Reed adds, “I like my darkness with humor.” His sardonic sense is evident in the “East Coast of Nebraska” collection’s title piece, which portrays the absurd lengths a business associate goes to in hiding the truth behind his seemingly stalwart friend’s scandalous death and illicit sexual history.

Reed speculates the source of his own dark side may be the “startling” experience of touring, at age six, the Dachau death camp while his career Army officer father was stationed in Germany. He drew on that episode for “The Time in Central Europe,” an evocative rumination on the crossroads an American service family finds themselves in in Germany during the Cold War. The protagonist is a small boy who sees the immediate menace of the Berlin Wall crisis and the past horror of Dachau reflected in the oppressive architecture of the region and in the Hansel and Gretel fairy-tale he’s reading. The area’s shining gold-faced clock towers seem beacons of hope but ultimately only reflect the inferno. Together with the anxiety the adults around him exhibit, it is a deeply troubling time for the boy, just as it was for Reed.

Naturally, Reed felt compelled to describe it in fiction, but years passed before he was able to come to terms with it. During a return visit to Germany as an adult, he says, “all this memory poured out and I was able finally to write a version of that story that was close enough to get it out of my system.”

Growing up a military brat, Reed moved from state to state, even overseas. It was an “unrooted” existence, but one affording rich opportunities to see people and places he might not have otherwise. He attended 26 schools, lived in Alaska before it was a state and was in Germany when the Berlin Wall went up. The longest he settled anywhere was seven years in Virginia. A “smart, alienated kid,” he was a “voracious reader” from the time he entered school. His storytelling first blossomed in the form of cartoons and even a daily comic strip he created for his own amusement. Later, he began writing stories for classroom assignments.

Whether his stories reverberate deeply with own life or spring full-born from his fancy, they are rooted in careful observation. Everything is potential material. “Absolutely, everything,” he says. “Cereal boxes, the old lady carrying plastic bags, a guy slamming lug nuts off a tire.” Keen awareness is a writer’s duty or curse. In Reed’s case, also his pleasure. “I’m constantly trying to pay attention to what people say and do. To catch subtleties of nuance and behavior. I’ve always been entertained just watching people. I’m pretty much an eclectic sponge. I’ve got this great store of stuff in my head, so I assume I was always fairly observant, even as a kid.” When something strikes him, he jots down impressions or makes mental notes.

“Transit Info.,” a slice-of-life story about disparate city bus riders, grew out of a conversation Reed overheard on a MAT bus. “People were discussing the nature of heaven, and I sat and thought, ‘Well, who are these people who would all end up in the oddity of this time and place discussing the nature of heaven? How did this happen? How did we get here?’” Imagination filled in the rest. Similarly, “Customer Recognition,” in which a guilt-ridden stick-up man has a life-reviewing catharsis at the garage he’s robbing, came from Reed observing a service station attendant.

A Newsweek article sparked Reed’s interest in Nikola Tesla, a brilliant if eccentric electrical engineer and inventor of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The resulting story, “Mr. Tesla’s Thunder,” explores the effect this wizard-like man has on the residents of a pioneer town upon setting up shop there and conducting awesome experiments to harness lightning and broadcast electricity.

Reed’s diverse interests and fluid style make him hard to categorize. His many literary influences include the late Wright Morris (whom he dedicates a tribute to in the next issue of The Nebraska Review), Robert A. Heinlein, J.R. Tolkien, Alice Munro and Mervyn Peake (“The Gormen Ghast Trilogy”). Filmmaker Robert Altman’s fusion-like story and dialogue riffs are another inspiration for this certified film buff.

Like many artists Reed strives hard to make his craftsmanship invisible. To let his technique work unconsciously on the reader. He doesn’t get carried away with any grand designs, however. “There are writers who want to put the I-beams on the outside of the structure, but I definitely am of the camp that you spend all your time trying to make sure this is not real obvious. That you essentially fool them into believing something that isn’t there. But then again, they’re all just squiggles on paper. Let’s be real.”

Plenty busy these days, Reed is now “slogging away” on a short story and in the early research stages of a first novel. “In the spirit of a don’t-jinx-the-project impulse,” he’ll only say the novel’s historical theme concerns a musician’s exploits in the Old West, including playing in a band under the command of Gen. George Armstrong Custer at the time of the Little Big Horn. Yes, that’s right, “Custer’s Last Band.”

“It was a scene picture-perfect, like the cover of a story book, with shadows climbing the vibrant contours of the earth, sliding over forests toward a small village, until he saw across the brilliant hills a clock. He saw on its face the ancient flash of sunlit gold, the red gold fire of twilight.

-from “The Time in Central Europe”

Related articles

- The Many Worlds of Science Fiction Author Robert Reed (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- World’s Best Short Stories: Boule De Suif (socyberty.com)

- Lit Fest Brings Author Carleen Brice Back Home Flush with the Success of Her First Novel, ‘Orange Mint and Honey’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

UNO Wrestling Retrospective – Way of the Warrior, House of Pain, Day of Reckoning

This blog recently featured my story “Requiem for a Dynasty” about the UNO wrestling program being eliminated. The story allowed longtime head coach Mike Denney to reflect on the proud legacy of brilliant achievement he helped build. That legacy ended ignominously, not because of anything he or his athletes or coaches did, but because of decisions made by University of Nebraska at Omaha officials and University of Nebraska regents to unilaterally cut a program that did everything right in pursuit of higher revenue Division I athletics. The action sent a disturbing message to anyone in the university system: namely, that dollars trump integrity and standards. The following three-part series on UNO wrestling was originally published in 1999 by The Reader (www.thereader.com), when I followed the program for an entire season. This experience put me in close proximiity to Denney, his coaches, and his athletes, thus giving me an inside perspective on how he conducts himself and his program, and I walked away from the experience with great admiration for the man and his methods, as virtually everyone does when they get to know him. Now as he starts a new chapter in his athletic coaching life at Maryville University in St. Louis, where he is leading a start-up program with a band of brothers he’s brought with him from UNO, I know that he will have the same impact there he had here.

A Three-Part UNO Wrestling Retrospective-

Part I: Way of the Warrior

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Near dusk on a Saturday in southwest Minnesota, ten samurai-like warriors lick their wounds after valiantly waging battle an hour before. Officially, they comprise the starting lineup for NCAA Division II’s No. 2-ranked University of Nebraska at Omaha wrestling team. But, in truth, they ply the ancient grappling arts in service of a master-teacher, Coach Mike Denney, whose honor they must uphold in extreme tests of skill, will, endurance.

Move over Magnificent Seven. Make room for The Terrific Ten.

Only they’re not feeling so terrific after losing a dual 23-16 to St. Cloud State, a North Central Conference rival UNO usually pummels. Having lost face in this Jan. 16 rumble up north, the Mavericks are bowed and beaten warriors whose dreams of a national championship lay temporarily dashed. Huddled in the close confines of the 28-foot Ford Chateau motor home the team travels in, the men sit in cold stony silence, awaiting their master’s arrival, and with it, hoped for redemption.

Losing hurts enough, but how they lost really grates. The St. Cloud debacle comes 18 hours after UNO defeats Augustana 25-11 in Sioux Falls, S.D. in what is a solid if unspectacular showing for a season-opening dual. Versus St. Cloud the Mavs build a 16-11 lead entering the next to last match, in which UNO’s stalwart 125-pounder Mack LaRock, a returning All-American, holds a 12-4 edge near the very end. But then, all at once, LaRock loses control, gets himself turned on his back, his shoulders driven into the mat and pinned with four seconds left, sending the crowd in cavernous old Halenbeck Hall into a frenzy and putting SCSU up 17-16 with one match to go.

Shellshocked, LaRock lingers on the mat, alone on an island of pain. Wrestling leaves no time for wallowing in defeat, however. Even when humiliated like this you must pick yourself up and shake hands with your victorious opponent, whose arm the referee raises overhead, not yours. As you skulk off in defeat, the next match begins.

Unfortunately, the Mavs’ entry in this Last Man Standing contest is 133-pounder T.J. Brummels, a weak link who quickly folds under the pressure and is pinned too, capping a stunning series of events that leaves Coach Denney staring out at the mat long after the final whistle.

A half-hour later the still brooding Denney tries absorbing what transpired and how to use it as a lesson for his team. He tells a visitor, “Wow. I don’t think I ever had one turn that quickly. I really don’t. We were in complete control. Mack’s just killing his guy…on his way to a major decision that would put it out of reach. Then it kind of just happened. It was like a knockout punch. I think I’ll tell my guys that back in 1991, the year we won the national championship, Augustana beat us with a team that wasn’t as good as this one. But from that point on our team said, ‘We’re not going to be denied.’ We’ll see what this team does.”

Later, in the motor home, LaRock, propped atop a cooler, head buried in his hands, sobs in front of his teammates, saying, “I’m sorry I let you guys down.” Albert Harrold (174) tenderly rubs his back, telling him, “Hey, when you lose, we all lose with you. We’ve all been there.” Others comfort him too.

As time drags on and the sting of losing burns deeper, the guys grow anxious over what Coach will say when he appears. Not because he’ll go off on some expletive-filled tirade. That’s not his nature. No, because they love him and feel they’ve let him down.

R.J. Nebe, former UNO wrestling great and assistant under Denney and now co-head wrestling coach at Skutt High School, says, “He’s a great motivational coach. The eternal optimist. He’s always upbeat, always supportive, no matter what happens. As much as you want to win for yourself, you want to go out and win for him. Anybody you talk to will say he’s kind of like a father figure. I know that’s a cliche but he truly is an amazing individual and you really do want to make him proud of you.”

Senior Mav Jerry Corner, the nation’s No. 1-rated heavyweight, says he appreciates the strong brotherhood Denney engenders. “Coach Denney impresses upon us to care about the guys we wrestle with. We’re not afraid to say, ‘I love you,’ and openly show some emotion when things don’t go right or when they do go right. That says a lot about the character and nature of the team. Coach Denney is the most positive coach I’ve ever been in contact with. He’s a coach, and then he’s a friend.”

For Denney, in his 20th season at the UNO helm, the role of friend and mentor is not one he feels obligated playing. It is genuinely how he sees himself in relation to these young men. He and his wife Bonnie are parents to three grown children — sons Rocky and Luke and daughter Michealene — and surrogate parents to 30 wrestlers. Serving youths is his fervent calling.

“I have a passion to work with young men and to help them along their journey. To guide them. To get them to get the best out of themselves. To gently nudge them and maybe not so gently sometimes. What I can bring to them is only experience and encouragement. They don’t have to listen to me. Some don’t. They learn the hard way. I don’t have great wisdom to share, but I do have great desire and I do care about them. It’s all teaching,” says Denney, who holds a master’s degree in education from UNO.

His desire to be a positive force in young people’s lives is partly a response to not having had a stable male role model while growing up on his family’s 160-acre farm in the shadows of the Sand Hills near Clearwater, Neb. His late father, Duke, was an alcoholic who abandoned Denney and his younger brother Dave and was abusive to their mother Grace. Filling the void were several key men in his life, among them his high school and college coaches. “They were all great role models. They had a big influence on me. They saw some good in me and kept encouraging me,” he notes.

He tries being this same nurturing figure to the athletes he coaches by creating “a family away from home” for them, especially those from single-parent backgrounds like his own. The “We Are Family” theme is one he and his wrestlers often reference. This sense of sharing a special bond is something he’s borrowed from his old high school coach, Roger Barry.

When Denney finally does climb aboard the motor home in St. Cloud, his big solid body filling the door frame, he speaks with the quiet authority and gentle compassion of a father consoling and fortifying his hurt sons.

“We didn’t give Coach Higdon a very good birthday present did we?” he says sardonically, referring to top assistant Ron Higdon, who stews behind the steering wheel, having turned 32 but feeling 72 . “What happened today I’ve seen happen to us before.” He goes on to tell about the ‘91 team rebounding from an unexpected loss. “And as we look back at that year, it was the best thing that could have happened. If it hadn’t happened, we probably wouldn’t have taken it up to another level.”

His dejected young charges listen carefully, fighting back tears.

Weeks earlier Denney confided he thrives on moments like these: “I honestly think I do the most good when they are at their lowest, most vulnerable. It’s when I can really make a difference with my guys. I actually like to see it happen because I think it’s then you can do so much building and can make a lasting impression. I try to be real sensitive to that.”

Back on the motor home Denney places a hand on LaRock’s shoulder, saying, “Nobody feels worse than this guy. Raise your hand if you’ve been there before.” The rest raise their hands in a show of solidarity. “It wasn’t like we performed terribly, but it’s going to take each one of us to get a level higher in conditioning. I see that. We have to do it. We’re going to do it. It can be just what is necessary for us to take the next step.”

Denney speaks in a deep voice whose easy cadence is soothing, almost mesmerizing. Then, like the taskmaster he must sometimes be, he promises he’ll push them in practice into the region he calls “Thin Air,” where they will train beyond exhaustion, beyond self-imposed limits, to reach the next highest rung. They will gladly endure it too.

“Be prepared men. We’re going to get after it. I’m going to take you until I see some of you over the trash can. I’m not doing it to be an a-hole. I’m just trying to take you to another level. I gotta do it. I just gotta do it. We have to push. We’ve got to get to Thin Air, when you don’t think you can make another step, but you can. And you will. So that when you get in the 3rd period or that overtime you’ve got something left.”

With his guys still smarting, he ends on a motivational note.

“You’re only one performance away from feeling good. We can’t really spend a lot of time feeling sorry for ourselves. Now let’s pull together and feel thankful. There were no injuries. This wasn’t the end. We’re not sitting here feeling like this after the national tournament. Be thankful for that. Be thankful there’s two months left. Be assured, all is well.”

Then, en masse, they kneel in prayer, holding hands. After being braced by their coach’s words and sated by a meal the sullen team loosens up on the drive back home, playing rounds of Spades, laughing, joking, being care-free kids again. They’re young, resilient. Yes, all will be well.

True to his word, Denney takes his team into Thin Air at practice the following week and, as predicted, a couple guys hurl from sheer burn-out. “It was one of the hardest practices I’ve ever had,” he says. “They were hurtin’, but they just wouldn’t let themselves break. Nobody hit the trash can until it was all done. They want to do well and know they can prevent what happened up there by being in better physical condition than anyone they go against. It gives each of them confidence that if it gets down to sudden victory, ‘I’ve been there. I’ve been in Thin Air.’ It can only help.”

The benefits of all that work show up in the Mavs next competition, Jan. 22-23, at the National Showdown Duals in Edmond, Okla., where UNO squares-off with four elite teams, finishing 3-1, advancing to and losing in the championship round to top-ranked Pitt-Johnstown 21-16. Bolstering the attack is junior Boyce Voorhees, a returning All-American, who goes 4-0 at 149 pounds in his first action since an early season injury. Voorhees is an intense wrestler capable of lifting an entire team with his dynamic style. The Mavs gain confidence coming so close to the No. 1 club without senior stud Braumon Creighton, the nation’s top-rated 141-pounder and a returning national champ, who injures a knee and forces UNO to forfeit his match.

Following another Thin Air day, the Mavs maintain their momentum Jan. 29 with a 21-18 win over No. 5 Central Oklahoma that is not as close as the score indicates since LaRock, nursing torn rib cartilage, forfeits. He also misses the next evening’s dual against the University of Nebraska-Kearney, which UNO runs away with 30-10. But Creighton returns triumphantly and he and his mates exude confidence that comes with Thin Air days being a weekly fixture. It’s all about keeping an edge.

The Mavs, with seven of their starting ten rated nationally, are back. Their aim on a national title still true. Denney feels good: “In some real close matches we’ve stayed confident, stayed strong, stayed focused. I like that. We now seem to have the reserve at the end to be able to do what we need to do. This team is on a mission.”

When the Mavs butt-kicking ways end abruptly in a Feb. 19 home dual loss to long-time nemesis North Dakota State, Denney isn’t so sure anymore. “As a team we have to hit on more cylinders. We have to perform better. It’s in us…but, I don’t know, maybe our expectations are just too high.”

After the less-than-inspired showing versus NDSU Denney issues an uncharacteristic in-your-face challenge to his slackers. “I wanted to shock them a little bit. They don’t see that side of me, but I needed to challenege them, and they responded — they really stepped up.” The Mavs respond with a 24-17 win over Div. I Northern Iowa to end the dual season 10-3.

The days leading up to the NCC tourney include intense practices that leave Denney feeling secure once again: “Honestly, that’s the hardest I’ve ever worked a team — but they took it. I’m really confident we’ll perform better. On paper North Dakota State’s the favorite, but we have no fear.”

Steeled by grueling workouts and bolstered by LaRock’s return the Mavs outlast the Bison 78-77 and win the NCC. In the process they regain face and inch closer to wrestling nirvana.With nationals a week away Denney likes how his team refuses to let injuries, forfeits or losses become distractions. “Those things are going to happen but I’m pleased with how our guys aren’t worrying about it. Each guy is staying focused,” he says.

Focused best describes Denney during a match. He never sits. Instead he prowls the sidelines, intently watching his men in action. He raises his voice to offer instructions (“Finish strong,” “Break him down,” “Let it flow”). His expressive face says it all, ranging from a pinched death mask to an open Irish mug. He’s the first one to congratulate his guys after victory

and to offer solace after defeat. After a rough outing he takes a wrestler aside to whisper encouragement– to put things in perspective.

“I tell our guys when they lose to not get that tied in with their self-worth. It’s got nothing to do with it. It’s completely separate.”

After home duals he works the crowd like a seasoned politico, pressing the flesh with boosters, fans, alums and other members of his extended wrestling family. His charismatic side shines through then. When greeting you he makes you feel you are the only one in his orbit. It’s the way he sidles right up to you with a sloppy grin splayed on his face, the way his big warm paw grasps your arm, the way his kind eyes meet yours, the way his “Aw Shucks” manner strikes instant rapport. But like any driven man his extreme focus sometimes catches up with him, putting him in a black mood.

His magnetic presence dominates team practices, which unfold in a sleek retro-style room brimming with banners, posters, plaques charting the program’s storied history. The room reflects different facets of the man, serving for him as training center, tabernacle and sanctuary all in one. With almost ministerial zeal he demands, prods, preaches adherence to the sport’s strict regimen. Indeed, Denney, active in the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and in ecumenical outreach activities, regards the room as “the Lord’s House” and himself as its “watchman” (his church’s pastor blessed it). He even lays hands on his wrestlers with a healer’s touch.

In a space dedicated to mastering the rigors of the mind and body, he is a high priest in this Temple of Fitness. A Master in the Way of the Mat training young ascetics to develop the gift of serenity and the art of physical combat. He is, in fact, a longtime martial arts practitioner, owning high black belt ranks in judo and jujitsu, and incorporates aspects of these Eastern disciplines in the wrestling program, such as greeting visitors by bowing and saying, “Welcome to the dojo,” or his disciples adopting as their mantra, “Ooosss.”

His men are models of cool, calm, collected poise. They accept cutting weight, the bane and burden of all amateur wrestlers, with stoicism.

Finally, Denney is a sentinel keenly attuned to all around him. A most honorable sensei seeking to embolden and enlighten each of his warriors.

“I make it my goal every day at practice to touch every one of my guys physically, with a pat on the shoulder, and to do the same with a positive statement. I like to circulate through the whole group so I can sense when somebody needs a little extra help. I try to catch them doing something right and reinforce that. As a coach you have to focus on doing that because you can get caught up in the other side of it — the negative side. Very seldom to people react well to negativity. I never did,” says Denney, an ex-college and semi-pro athlete and a still accomplished sportsman today. “My philosophy is that so much of the stuff outside of this room is negative that I try to have a positive atmosphere and environment, and it starts with me.”

When he spots one of his guys is down he has him home for dinner or takes him to church. To build togetherness he holds retreats and gets feedback from a team unity council. To help his wrestlers keep a mental edge and handle the pressures of being student-athletes he has two sports psychologists work extensively with the team. To make them better ciitzens he has wrestlers make goodwill visits to hospitals, nursing homes and prisons and assist with youth wrestling clinics.

“I believe in the whole person approach to coaching,” he says.

His wife Bonnie, who is quite close to the program, says he has the tools necessary for this empathic approach: “I think he’s a great communicator and is very wise about what a person is all about. He can listen and read a person and see where they need to be directed. He can motivate them. And he cares. It’s not fake either. He really cares.”

But don’t confuse caring for softness. His practices are pictures of hard work. He’s always pushing for more. More effort, more desire, more, focus, more tenacity, more commitment. He demands nothing more than he does of himself. At 51 he still works out religiously every day, stretching, hitting the treadmill, pumping iron. He refines his judo and jujitsu skills by training with the U.S. National Team at the Olympic Training Center in Boulder, Col., and still mixes it up in martial arts competitions. In 1982 he won the national masters judo championship at 209 pounds. He teaches judo at UNO and self-defense for area law enforcement agencies.

During the season he regularly works 12 to 15-hour days. Hard work and long hours are old hat for Denney, who from the time he was a boy did most of the farming on his family’s spread, where they grew corn, alfalfa, rye and vetch and raised livestock.

“I worked the fields. I helped cattle and sheep deliver their calves. My brother and I milked cows every morning before we went to school. We broke horses. When I began driving a truck and tractor I had to sit on a crate to see over the steering wheel.”

Minus a TV, he and Dave made their own entertainment. “Looking back, I suppose it was a meager existence, but we never thought so.” He variously rode a horse or drove a tractor to the one-room schoolhouse he attended. The school doubled as the community church. His mother taught Sunday School there. He and Dave didn’t dare miss.

Denney concedes his mother, who still lives on the farm at 84, has been the greatest influence in his life. “My real hero is my mother. She’s a rock. She had it real tough raising us on her own and just scratching out a living, but we never wanted for anything. She’s a woman of strong faith and positive attitude. She’s an inspiration to me. She’s amazing.”

Bonnie feels her husband owes much of his iron will and true grit to Grace. “His mother’s a marvelous, strong individual. He got from her a strong character and work ethic that you can’t believe. Nobody will outwork him. He just covers every base. He puts his entire self into it.”

He admits it’s easy losing one’s bearings amid coaching’s endless demands. “In this profession you can get your priorities mixed up pretty easily. It can really consume you. There’s always somebody else you can recruit. Always something else you can do. You really have to work at keeping a balance in your life. My wife has really helped me a lot on that.”

His Never-Say-Die credo served him well during UNO Athletics’ lean times. In the late ‘80s state funding was cut, resulting in severely trimmed budgets, some men’s programs relegated to club status and pickle card sales begun as a last ditch revenue-making source. And until last year’s long overdue fieldhouse renovation Denney got by with second-rate facilities. The old wrestling room, charitably remembered as “a hole in the wall,” was so bad he steered recruits away from it.

“When UNO athletics went through that down period it had a negative effect on all the men’s sports, except wrestling. One of Mike’s supreme accomplishments was to keep right on winning championships. He had no facilities but the man never came to me with anything even resembling a complaint. The truly amazing thing was him getting quality athletes under those conditions. He’s a terrific salesman and has the insight to find the right young men who fit our program. Plus, he’s a great motivator,” says former UNO Athletic Director Don Leahy, now Assistant A.D. at the school.

Assistant Ron Higdon says the new facilities bring higher expectations and added “pressure” for Denney. “He doesn’t look at it like, ‘We’ve got it made, but more like, ‘We don’t have any excuses any more. Let’s not leave any rock unturned. We don’t want any regrets.’” He’s tightened the screws.

Bonnie Denney says her husband thrives on adversity. “He likes it tough. His whole life philosophy is: ‘Get out of the comfort zone in whatever you’re doing. That’s when you will grow.’” He simply says: “I like challenges.”

It’s the same resolve he showed farming and as a football-wrestling standout at both Neligh High School and Dakota Wesleyan, the NAIA college (in Mitchell, S.D.) he attended and whose Athletic Hall of Fame he’s inducted in. As a college lineman he played both ways, often never leaving the field. When the gridiron season ended he went right into wrestling. “One day off was enough. It was a year-round deal,” Denney recalls.

After graduating with a teaching degree his goal was making it in the National Football League. It was 1969. The Vietnam War was hot. The military draft in effect. His kid brother, then an Army grunt in ‘Nam, wrote home warning to “stay out of this mess.” Luckily, Denney got a deferral upon landing a contract with the Omaha Public Schools. When the NFL did not beckon he signed with the Omaha Mustangs, a semi-pro football club popular with area fans in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Even after moving to Omaha with Bonnie, whom he married that summer, he kept alive his NFL hopes.

“I spent a number of years on that mission.”

Life in the ‘70s revolved around teaching (math) and coaching (wrestling, football, track) — first at South High and later at Bryan — and playing ball. He paid a steep personal price for the grueling schedule.

“I’d go early in the morning to lift weights, then teach all day, then coach and then practice with the Mustangs all night. I’d travel on the weekends. There were times when I never saw our first son awake. I really neglected my family. I don’t know why my wife stayed.”

Despite the costs, he would not be deterred from his dream. “Playing with the Mustangs filled the need I had to still compete and play. It was my NFL. I loved it.” He played seven years and concedes only the club’s folding prevented him from continuing. Judo then became his competitive outlet.

What is the appeal of athletic competition? “Unlike the corporate world, you have instant feedback with it. It tells you right away how you did. You can look at wins or losses. Or, like I do, you can base it on performance. The real opponent is yourself — trying to get the best out of yourself.”

He could have coached football in college but chose wrestling. Why?

“You look for vehicles to teach and build and what a great vehicle wrestling is because it’s so demanding. It takes so much discipline, dedication and commitment. You’re going to get beat right out in front of everybody. You can be humbled at any time and very quickly. It brings out the best and the worst in you. And you get so much closer to your athletes in wrestling.”

He finally did get his shot at the big-time via a free-agent try-out with the Chicago Bears in the mid-70s. He was among the final players cut.

“I worked so hard at it and spent so many years pursuing that mission, but in the end I was a marginal player. I faced that fact. And I realized the NFL was not the ultimate answer to my needs. The Lord had other plans for me…much better plans than I could ever have imagined.”

Those plans brought him to UNO in 1979 when Leahy, who saw his work ethic up close as a Mustangs coach, hired Denney, despite no prior college coaching experience, to lead an already respected program.

“Mr. Leahy took a chance on me,” he says, “and I’m forever thankful for that. It was a tremendous opportunity.”

Denney’s made the most of the opportunity by taking UNO wrestling to new heights, annually contending for the title. The year UNO won it all, ‘91, posed a severe trial for him and his family. First, a former Mav wrestler he was close to, Ryan Kaufman, died in a car accident. Denney calls him “our guardian angel.” Then Bonnie, who has multiple sclerosis, fell gravely ill, enduring a lengthy hospital stay. She fully recovered and is healthy today. She says the experience deepened the family’s bond and faith.

Also deepened is her husband’s outlook on athletics. “He used to have a terrible time dealing with losing,” she says. “But now the process has become as important as the result. He’s discovered the joy is in the journey.” Indeed, he preaches to his troops, “Respect the journey, but don’t sell your soul for it.” It’s why he emphasizes the values and lessons to be gained from competition over records and wins. It’s about helping young men “feel somebody cares about them. That there’s an investment in them. That they have some worth. Basically that’s what we’re all looking for,” he says.

It’s a message he delivers in public motivational talks. It’s why he calls his job “a privilege” and twice turned down the head coaching post at Division I Wyoming. Why he is at home with his wrestling family. “I honestly think I’ve been put here as the watchman. I’ve been assigned this. It’s meant to be.”

Part II: House of Pain

Destiny seems on the side of the No. 2-ranked University of Nebraska at Omaha wrestling team entering the NCAA Divison II national championships Friday and Saturday in Omaha: UNO’s nine individual qualifiers match the most of any team; the school is hosting the finals in it own Sapp Fieldhouse on the UNO campus; and the tourney will coincide with Head Coach Mike Denney’s induction into the Div. II Wrestling Hall of Fame.

It is, as Denney’s fond of saying, a time “to shoot for the stars.” The source of UNO’s tempered-steel toughness is forged not in the stars, but in the inferno of practice and in the heat of battle. In a journey through pain.

A UNO practice resembles a “Guernica-like” scene with its entangled heaps of twisted, wreathing bodies and flushed, grimacing faces belonging to a sect of athletes who endure punishment as a badge of honor. Some lay sprawled on the mat, limbs clenched in a contortionist’s nightmare. Others crouch in a gruesome dance, pushing and pulling like territorial bulls.

More than any other sport, wrestling is a survival contest. Technique, fitness, power are all vital qualities but when these things are relatively equal, as they often are, it ultimately comes down to a test of wills. A confrontation to see who can withstand more, who can outlast the other.

Wrestling is a sport of resistance, using the body as a pinion and vice to gain leverage and control. It’s countering your opponent’s moves with ones of your own. It’s long stalemates followed by lightning quick reversals, take-downs, pins. One tiny slip in concentration can prove your undoing.

In the heat of action bodies become locked in vicious embrace. One torso tightly wound around another. A leg wrapped around a neck. Arms ratcheted back from the socket with enough torque to tear ligament and snap bone. Tongues hang out from sheer exhaustion. Sweat runs off in sheets. The thud of bodies on the mat mixes with anguished cries and grunts. As if this agony isn’t enough, there’s the bane of all wrestlers — cutting weight. Truly, it’s as much penance as sport.

Welcome to the House of Pain. Every wrestling club or program has one. It’s often only a ratty old mat in a cold dark gym. Until this season UNO made do with a pit too small to accommodate a full practice. For years its teams trained around the school’s other sports, carting and rolling out mats onto the fieldhouse floor and rolling them up and carting them back off when done. With the completion of a multi-million dollar fieldhouse renovation last year, the Mavs finally have a training facility all their own and one commensurate with the program’s powerhouse status.

Located in the northeast corner of the fieldhouse’s top floor, the UNO wrestling room, a.k.a. the dojo, is a 5,000-plus square-foot facility where all 30 wrestlers can work out in at once. It includes a kick-ass mat, a video station, a digital scale and a sound system. It’s clean, well-lit, ventilated. It’s also where guys shed sweat, blood and tears and gasp for air.

On “Thin Air Days” UNO coaches push their athletes past fatigue, past the breaking point — all in an effort to build mental-physical endurance. A trash can stands nearby for those who get sick. On those days practice begins at 3 and goes full bore past 5. One drill immediately follows another, pairing wrestlers off on the mat as coaches hover above goading them on.

“Your body can do it,” assistant Cory Royal shouts at a prone wrestler one recent practice. “It’s mind over matter.” With that, the spent lad drags himself to his feet and gets after it again. There’s always more to give.

To cap off practice the team runs stairs. The late afternoon session is in addition to a morning workout and individual running and lifting drills. On competition days the demands only increase. In tournaments, such as the nationals, entrants may wrestle multiple matches on day one and still run that same night to ensure making weight for day two’s action.

“In no other sport do athletes have to put themselves through what wrestlers put themselves through,” says top UNO assistant coach Ron Higdon. “As coaches it’s what we love about this sport.” Denney says, “You look for vehicles to teach and build and what a great vehicle wrestling is because it’s so demanding. It takes so much discipline, dedication and commitment. You’re going to get beat right out in front of everybody. You can be humbled at any time and very quickly. It brings out the best and the worst in you. I like these challenges.”

Why do athletes do it?

“I don’t know, maybe I’m a masochist, but I love it. Wrestling is a sport that’s so demanding. It takes the mind, body and soul. It takes everything that you can possibly muster and I guess that’s the challenge I really enjoy,” says senior Jeff Nielsen, (133 pounds), who went 0-3 in the NCC tourney.

There’s more to it than that. It’s being cast alone on an island of pain and using every ounce of courage and skill to try and best your opponent.

Senior Mav Braumon Creighton, a national champion at 134 pounds last year and top-seeded at 141-pounds this year, is a fluid methodical performer who appreciates wrestling’s intricacies.

“I like the science of the sport. The leverage, the speed, the techniques and the type of physical attributes you need to be a good wrestler. I like the mental preparation that goes into it. I like the battle. I like the nervousness. I like how it’s a chess match out there and you’ve got to make the right moves. I love everything about it except the cutting weight part,” Creighton says. “And when the lights go on it’s my opportunity to put on a show. To say, ‘Look at me. Look at how good I am. Look what I can do.”

For two-time All-American Boyce Voorhees, a junior contending for the 149-pound crown this weekend, it’s “the competition.” He adds, “The best part about it is it’s just one guy against another. It’s you against him. Nobody else has anything else to say about it. You have no excuses.”

“It’s a great challenge every time I wrestle,” says junior Chris Blair, a two-time All-American competing at 165 pounds in the NCAA finals, “It’s a test of all my training methods and everything I believe in. When I win, everything about me wins. When I lose, I lose all that stuff. In order to be a champion you’ve really got to work hard at it every single day.”

For motivation UNO ‘s athletes need only look at the wrestling room’s walls adorned with banners and plaques honoring the program’s many All-Americans, national titlists, Hall of Famers and championship teams.

The swank new room has made a deep impression on the team, serving as inspiration, validation and challenge. For senior Jose Medina, a returning All-American and a national qualifier this year at 197 pounds, the space is a source of good vibes. “The room has so much character and Coach Denney’s put all that character in there with the All-American plaques and the banners listing the national champs and the records. It’s awesome to be around all that.”

Sophomore Scott Antoniak, a national qualifier at 184 pounds, says, “We walk around with a bit of added confidence. We have our own room. We have something to be proud of. It gives us something to brag about.”

Blair feels the room sets a serious, no-nonsense tone: “Having something like this makes you feel like you’re in an elite program. It really helps mentally coming into a place everyday that’s this businesslike and professional. It gives us added confidence and strength.”

“I can’t even tell you all the things it does for us,” says sophomore Mack LaRock, a national qualifier at 125 pounds. “It gives us a home, for one. I think it also raises the expectation level of ourselves. We feel we’ve got to rise to the occasion and perform, almost as if we’ve got to earn what we’ve been given.”

Ron Higdon

Indeed, Higdon says the new facilities have added “pressure” on the coaching staff. “Coach Denney doesn’t look at it like, ‘Ah, we’ve got it made, but more like, ‘We don’t have any excuses anymore. Let’s not leave any rock unturned. We don’t want any regrets.’”