Archive

Ron Stander: One-time Great White Hope still making rounds for friends in need

I did this follow up story on ex-Omaha heavyweight boxer Ron Stander about seven or eight years after the first story I did on him, which you will also find on this blog. In that earlier piece Stander was still fighting some demons, still in the throes of recovery. In the interim, Stander had come to terms with some things in his life and by the time I did this second story he seemed more at peace with himself and his place in the world. Stander was and is a tough dude, but he’s also a big teddy bear of a man with a heart of gold. That’s one thing that’s never changed about him. This story, which originally appeared in the New Horizons, portrays Stander as the good man he is, just a regular guy who helps his friends, including some fellow ex-boxers who have fallen on various hard times. To a man, his buddies love him. It’s heartening to know that Stander is now happily remarried and writing his life story. It should be a helluva read.

Ron Stander: One-time Great White Hope still making rounds for friends in need

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Far from the spotlight he inhabited when he fought for the world heavyweight boxing title 35 years ago, Ron “The Bluffs Butcher” Stander goes about his daily routine these days in relative obscurity. That’s fine with him. He had his moment in the sun. He’d rather be remembered anyway as a good man, a good father and a good friend than as a good fighter.

“Yeah, right, that’s exactly it,” he said. “I just want to be a good person.”

He lives a simple life, both by choice and circumstance. He may be poor in finances, but he’s rich in friends. Despite his own problems, he aids folks less well-off and able than him, often making the rounds to visit old pals, many of whom he knows “from boxing.” Some, like Tony Novak, Gabe Barajas and Art Hernandez, are ex-fighters. Novak and Hernandez sparred with Stander back in the day.

Fred Gagliola coached a young Stander as an amateur Golden Gloves fighter. Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon is an ex-pro wrestler quite popular here. Stander and Vachon know the highs and lows of life inside and outside the ring. Tom Lovgren was the matchmaker for many Stander fights and at one time managed him.

Each man suffers some kind of health impairment or disability. All befriended Stander at one time or another and he’s never forgotten it.

“They all helped me. Now I attempt to give back in some way. I like to help out. They were in my corner and now I’m in their corner,” said Stander, who variously does chores, runs errands and offers companionship for them.

Lovgren is afflicted with multiple sclerosis. The effects of the advanced disease confine him to a wheelchair. When his wife Jeaninne broke a leg last winter she could not get her large husband out of his chair into bed.

“So I called Ronnie and said, ‘Can you come down and help me into bed every night?’ — and he did,” Lovgren said. “He came down at 10:30 every night and put me to bed. I paid him, because he didn’t have to do that. He’s a good friend.”

Not long ago Lovgren took a fall at home, unable to get up by himself or even with an assist from his petite wife. Enter Stander.

“It was about 10 o’clock at night. I was beat, tired. I worked hard that day and I was all out of gas. I’d just had my first beer of the night when Jeaninne called. ‘Can you help out?’ I went down to their place. He was flat on the floor and I had to pick him up…and put him in his chair. It was a tough lift. Boy, he’s getting heavy. Probably weighs 250. Dead weight,” Stander said. “I about didn’t make it. Jeaninne had to get on his side and grab his pants and pull him up. We got him though.”

Stander’s glad to help the man who so much did for him. Lovgren not only got him fights, but was part of the team that readied him for his May 25, 1972 title bout with champ Joe Frazier in a jam-packed Civic Auditorium. Lovgren prodded Stander to get in fighting trim and stay away from late night beer binges.

“He would always get me to do the road work real good,” Stander said. “He’d take me running, count laps. He was a real disciplinarian. But fun, too. I respected him.”

Before he challenged for the championship, Lovgren arranged what Stander called a “steppingstone” match with future contender Earnie Shavers. Considered one of the hardest punchers in the heavyweight division, Shavers’ blows “felt like getting hit by a night stick or a ball bat,” Stander said. “It was like a whip cracking at the end.” After a slow start that saw him get pummeled, he KO’d Shavers in the fifth. Shavers reportedly had to be carried off by his corner.

That became Stander’s signature win. His most notable loss, of course, came in his title bid. After losing to Frazier, Stander sank into a deep depression and his career nose-dived. “I didn’t have any desire,” he said.

Except when Lovgren got him a marquee match against former contender Ken Norton on the undercard of the Muhammad Ali-Jimmy Young bout. Norton won when the fight was stopped in the fifth due to cuts he opened up on Stander, who was prone to bleed, but to this day “The Butcher” feels he would have had a tiring Norton “out of there in another round or two.”

Coulda’, woulda, shoulda’. “You can’t fight destiny” Stander said.

Away from the ring, the fighter admires how Lovgren has never given up in his own battle with MS. Despite the debilitating disease, Lovgren has raised a family, worked, traveled and maintained his passion for sports, especially boxing.

“He’s been an inspiration,” Stander said. “He’s paid his dues.”

The other men Stander helps are inspirations to him, too.

Former world middleweight contender Art Hernandez lost a leg after a freak fall from a roof, but he hasn’t let it stop him from living a life and enjoying his family. “I’ve got all the respect for him, too,” said Stander, who, like Lovgren, considers Hernandez to have been the best fighter, pound-for-pound, to ever come out of Nebraska. As an undersized but much quicker sparring partner, Hernandez used to frustrate Stander in the gym, confounding and evading the lumbering heavyweight. “I couldn’t hit him with a handful of rice,” Stander said.

Stander admires too how “Mad Dog” Vachon has not allowed the mishap that cost him a leg to embitter him.

“’Mad Dog’s’ a good guy,” he said. “He has a great attitude.”

Through “Mad Dog” Stander met an array of pro wrestling legends, such as Andre the Giant. “When I shook his hand it was like grabbing a pillow,” he said.

When Hernandez first got fitted with his prosthesis Stander brought him over to “Mad Dog’s” place so these two old warriors with artificial limbs would know they were not alone. The gesture touched the two men.

“He did me a favor that day,” Hernandez said.

“He’s got a heart of gold,” Vachon said. “He’s a very nice man. A real softee. He’s the kind of guy who would give you the shirt off his back.”

Since suffering a series of strokes Fred Gagliola, the man who helped show Stander the ropes as an amateur, has trouble getting by.

“I was just weeding in his yard the other day,” Stander said one summer morning outside the south downtown home of the man he calls Coach. “He can’t do much. I sweep and mop the floor for him.” “He cuts the grass, he throws out the garbage,” Coach said. “Whatever it takes,” added Stander. “I just try to help him however I can. He was on my side in the Gloves, you know. He backed me, supported me. He did favors, I do favors. He helped me, I try to help him now. So it’s pay back.”

Although he can use the money, Stander doesn’t lend a hand for the “couple bucks” he earns “here and there.” “Other things,” besides money, “make him happy,” Vachon said. Like doing good deeds.

Friends and family are all that are left once the money runs dry and the glory fades. “Mad Dog” and “The Butcher” made names for themselves in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Vachon reigned as an All-Star Wrestling king on cards at the Omaha Civic Auditorium. That’s where Stander enjoyed his greatest ring success, topped by challenging Frazier for “all the marbles” in what may have been the biggest sporting event Omaha’s ever seen.

The title fight was the pinnacle of his career. But life goes on. Things change. Stander was 27 and fighting on the biggest stage his sport has to offer — in his adopted hometown no less. Before friends and family and the assembled boxing world he put himself on the line and he failed. The fight was stopped after four rounds, Stander’s face a bloody, pulpy mask. He never went down, though. He pleaded for the fight to continue, but ringside physician Jack “Doc” Lewis made the only call he could given that Stander was blinded by blood from ugly gashes and could no longer defend himself. A longtime friend said Stander cried in the dressing room, sure he’d disappointed everyone. The friend assured him he hadn’t.

The incident reveals a couple things: how much Stander, often accused of taking a nonchalant approach to his training, cared about representing his hometown; and his never-say-die attitude. “I trained hard for the fights I cared about. I wanted to prove I was a legitimate contender,” he said. No one could ever call him a quitter.

“He’s got a heart the size of this room,” Lovgren said from his spacious living room. “When Joe Frazier is unloading on you and you’re still standing, you’re something special. Tough guy.”

Life hasn’t been a bed-of-roses since the Frazier fight. Stander’s contentious first marriage ended. He didn’t get to see much of his oldest two kids growing up. He remarried and had two boys before this second marriage soured. He has custody of the boys, Rowan and Ryan. He tried being an entrepreneur, owning his own bar, but that didn’t last. Long an imbiber, he developed a problem with alcohol and a DWI landed him behind bars. “I was stupid. I made some wrong decisions. I didn’t know when to say no. Let the good times roll. Let the party begin. When I had to go away for three months it was like shock treatment,” Stander said. “I was going to grow up sooner or later. Maybe it helped me to.”

The biggest blow — to both his pocketbook and ego — was losing the best job he ever had, as a machinist at Vickers. Through it all, he’s stayed sober and tried to do the right thing for his kids and his pals.

“He’s a good guy,” Lovgren said. “He’s a good father. He takes good care of those kids. He’s really a caring person. If you ask him to do something he makes a real effort to do that. If I need anything I know he’ll come.”

Largely unemployed since 2000, Stander leads a hand-to-mouth existence that finds him scrounging for discarded cans and car batteries he brings to the recycler for chump change. He also does odd jobs for people who reward him with scratch. “Most of the time I’m trying to hustle some gas money and food money,” he said.

One of his frequent stops is A. Marino Grocery, a South 13th Street throwback, or as Stander likes to say, “blast from the past.” Proprietor Frank Marino joked, “He’s my pacifier. If somebody doesn’t pay a bill we send him out to collect.” In reality, Marino said, “We have him do little things, cleanup a little bit, make a delivery every once in awhile for me.” “Take some boxes out,” added Stander, who on a recent visit grabbed a bundle of flattened cardboard boxes and deposited them in the dumpster out back. “It’s the same at Louie M’s (Burger Lust). We’re paisan.”

It puts a few extra dollars in Stander’s pocket. Otherwise, he gets by on his monthly Social Security check. There’s no pension, no nest egg to draw on. Fighters don’t have retirement plans. He does have a 401K through Vickers, but he’s had to dip into it to make ends meet. All of which makes things tight for a man raising his two youngest boys alone. One silver lining is that his house, a mere two blocks from Rosenblatt Stadium, is paid for. Another is that his son Rowan, a senior at Creighton Prep, is a top wrestler who might earn a college athletic scholarship.

Stander’s a robust 62, but he has health issues. He’s overweight, with high blood pressure and diabetes. He’s missing several teeth. For comic relief he slips his dentures out and opens wide to show his bare mouth. He has trouble remembering things. It’s what becomes of old fighters, even one as strong as an ox like him

He doesn’t complain much, except to bemoan the loss of that machinist’s job at Vickers, where he operated drill presses, grinders and lathes. The Omaha plant closed just before Christmas 2000, leaving him and more than 1,000 co-workers out in the cold. He was 55, an age when it’s hard to start over. With only a high school education and no marketable skills, he’s got few prospects.

“When Vickers closed up, that was it, that was the final straw for me,” he said, “because by the time you’re 55 or 60, if you’re not locked into something, you’re done, you’re screwed. So I’m screwed.”

He sometimes wonders if he did the right thing pursuing a boxing career. He began at Vickers in ‘65 while still an amateur. After turning pro in ‘69 he quit his job, even though his early purses were negligible. He got $75 his first fight. A few hundred each the next few bouts. Until Frazier his biggest purse was a few thousand.

“I had a good job at Vickers…If I had stayed there all those years and not taken a shot at the title I’d be retired right now. I went back to Vickers in ‘93 and when I finally started getting the big money in ‘95 they closed the plant. That’s what grieved me. People say, ‘Well, you can start over and work your way up again’ Yeah, right, whatever.”

Men his age aren’t in demand by employers.

“I’m ready to work, but people don’t want to hire ya. I’ve talked to friends in construction and they say, ‘We’re looking for guys 35, not 55. I talked to a friend in the heating and air business and he said, ‘Well, you know, Ron, at your age we don’t want you to be up on a roof when it’s 120 degrees working on an air conditioning unit. You could have a heart attack.’ There again, the age factor.”

He did attend Vatterott College to learn a trade. He was an apartment maintenance man, but tired of tenants calling in the middle of the night demanding their leaking toilets be fixed. His pride won’t let him take an $8 or $9-an-hour job. Until a few years ago he made extra dough refereeing boxing matches in Nebraska, Iowa, the Dakotas and Minnesota. He even did a few televised title bouts. But those gigs dried up with the loss of independent promoters. He’s shut out by the casinos, where the fight action is these days, and their contract refs. Besides, with two boys, in his care he can’t be gone on those overnighters anymore.

Like the old pug in Requiem for a Heavyweight, he’s at a loss what to do now. Fighting is all he knew. For a time he did have his own bar, The Sportsman’s Club, but his weakness for the drink made that an unhealthy environment for him to be in. He’s clean and sober now, but that alone doesn’t pay the bills.

Money worries nag at him, especially with the boys to clothe and feed. “It’s a struggle,” he said. “We live on $953 a month Social Security.”

Come College World Series time he pulls in some much-needed cash parking fans’ cars, at $5 a pop, on his property. His record for one game is 26 vehicles. But that happens only two weeks a year. He also makes some money from autograph signings he does in Omaha, Lincoln, Des Monies, et cetera.

Enough time has passed that he doesn’t carry the cachet he once did, when his mug and name were enough to buy him drinks and meals and perks wherever he went. As Omaha’s last Great White Hope, everyone wanted a piece of him then.

“It’s not like it used to be,” he said.

The Vickers job seemed like a sure thing and then, poof, it was gone — the steady paycheck, the security, his self-esteem. “When I had money, when I had a job,” life was good, he said, “before things went from sugar to shit in a short time.”

Quicker than you can say, Whatever happened to?, the career club fighter blew the six-figure purse he earned for his only shot at immortality. There were a handful of other big paydays. But the pay outs in his era were small potatoes compared to the millions contenders command today.

Long gone are the days when media hounded him for quotes. His last real exposure came in 2001, when he appeared with Joe Frazier, the man who gave him a Rockyesque chance at the title. For only the second time since that fight, the two warriors met — for a Big Brothers, Big Sisters of the Midlands promotional event in Omaha. In the way that old combatants do, they embraced like long lost buddies. They were never close, but the mutual respect is real.

The ensuing years wrought much change. Their hair’s flecked with gray, their mid-sections grown soft, their speech slowed. Yet, to their good fortune, each shows few effects from the punishing blows to the head they absorbed as sluggers who took many shots to land one of their own. They still have their wits about them.

But Stander’s life is a far cry from the ex-champ’s. Frazier is an icon within the larger sports canon for his Olympic gold medal, undisputed heavyweight crown, his three memorable fights with Muhammad Ali and the dramatic way he lost the championship against George Foreman. He has his own gym and other business interests in his hometown of Philly. His much sought-after autograph brings hundreds of dollars, compared to a fraction of that for Stander’s.

Where Frazier is a featured storyline in boxing history, “The Butcher” is a sidebar and footnote. Or an answer to a trivia question: Who was the last fighter Joe Frazier beat while world champ? Ron Stander. Stander’s match with “Smokin’ Joe” came between Frazier’s two most historic fights — eight months after beating Ali at New York’s Madison Square Garden and eight months before being brutally beaten in Jamaica by Foreman, who took the crown only to lose it a year later to Ali.

The boxing world can be a small community. Even though Stander’s career is

forgettable by all-time Ring Magazine standards, he’ll always be a part of boxing history for having fought for the title. The fight occasionally shows up on ESPN Classic. His bid, too, came at a time when the title was still unified. Plus, he squared off with some of the sport’s biggest names — Frazier, Shavers, Norton, Gerrie Coetzee. Then there’s the fact his career intersected with other legends, like Foreman, who was at the title bout in Omaha and reportedly saw something he exploited when he later faced and destroyed the champ.

Specifically, Stander worked on an uppercut to take advantage of a flaw in Frazier’s defenses. In the third round he saw his opening and let the uppercut fly, missing by an inch. He figured he’d only get one chance and he was right. Conversely, Foreman pushed Frazier off and caught him coming in with the same punch.

Then there were Stander’s meetings with The Greatest. He said on four occasions he was a surrogate member of Ali’s entourage. He said Ali liked having him around for his parodies of Aliisms like, “I’m the greatest of all time.” Stander does a fair impression of Ali, of sports broadcaster Howard Cosell, who once interviewed Stander, and of Mike Tyson, the troubled ex-champ.

Stander met Tyson in Las Vegas in the ‘90s, long after his own career had ended. There’s a story behind their encounter. In preparation for Frazier, Stander manager Dick Noland wanted him far from distractions and so shipped him off to Boston to work under famed Johnny Dunn. After the Frazier fight Stander parlayed the connections he’d made back east and went to the Catskills to train under legendary Cus D’Amato. It was D’Amato who went on to mentor the young Tyson.

Stander was in Vegas, where Tyson was training for a title defense against James Broad, when he paid a call on the then-champ. As dissimilar as the two men were, they did share a pedigree in the person of Cus D’Amato.

“He knew all of Cus’ disciples and he knew I was with Cus, so he let me in the gym. No introduction, he just came right up to me, ‘Hello, Mr. Stander.’ ‘Hey, champ, how ya doin’?.’ ‘I’m working on an uppercut that will drive that nose bone into the brain.’ ‘Yeah, that’s a good move, champ,’ said Stander in a wickedly dead-on Tyson impersonation — childlike voice, silly lisp and all. “He was something.”

“The Butcher” even ended up in a film, The Mouse, based on the life of his real-life friend, ex-boxer Bruce “The Mouse” Strauss.

Stander also hung out with non-sports celebrities — as a bodyguard for the Rolling Stones and The Eagles. He said Evel Knievel, whom he got to know, offered him $3,500 to work the security detail for his Snake River Canyon jump. Instead, Stander took a fight in Hawaii, where he’d never been, for the same money.

All these brushes with fame please Stander, but as he likes to say, “That and 50 cents will get you a cup of coffee.”

He experienced about everything you can in boxing. Good, bad, indifferent. He never really announced his retirement, but he knew when it was time to quit.

“You know when you’re almost done,” he said. “You don’t have the desire or the hunger. You’re tired of the running and the road work. You’re tired working out all the time. The stitches start mounting up. Your nose gets a little flatter. Your teeth get a little looser. Your brain gets a little jiggled. You just lose it.”

If anything, he hung on too long, waiting for one more big payday that never came. “Yeah, that’s probably right,” he said. “There at the end I fought a lot out of shape because I didn’t care. But a guy’s gotta have money. It wasn’t like I was gaining seniority working for U.P.”

Rather than work for meager wages today, he scrapes by. He’d like to run his own gym, but that takes moolah. One benefit of not having a regular job is that he has time to spend with his kids and help friends.

“I try to be a role model and do the right thing for these kids. I have to show them the right way to go,” he said.

As for his friends, Stander said, “They did right by me,” and now he’s trying to do right by them. Gabe Barajas appreciates having Stander as a friend. Barajas, the former owner of Zesto’s near the zoo and stadium, said, “We’re pretty close. He used to come up and help me out there, too, shaking everybody’s hand, bringing the heavy pop coolers up to us. He did lots of things. He ate a lot, too.”

Stander’s visits to the nursing home Barajas resides in bring a smile to his friend’s face. Stander sometimes takes Barajas, who has MS, for drives, down to old haunts. He lifts Barajas from the bed or recliner into his wheelchair and puts him and the chair in his car. Stander said his friend needs outings like these. Otherwise, “that’s his life — in that room and down in the dining hall,” he said.

Fred Gagliola, Stander’s old coach, knows he can count on him. “Oh, hell, yeah. He comes down here all the time to help me out,” Gagliola said. “He’s a good friend.”

Tony Novak, Stander’s first sparring partner, lives alone in a Carter Lake trailer home. Stander frets over his buddy’s health. “Ron’s been a good, true loyal friend for 40 years. He checks on my every day,” Novak said.

The breaks maybe haven’t gone “The Butcher’s” way since he lost to Frazier, but he just chalks it up to “fate” and appreciates what he does have.

“No matter how good you are, how smart you are, how well-built you are, you gotta have a little bit of luck to go along with it,” he said. And you gotta have “a few good friends.” That he has. It’s why he’s not about to quit now. There are too many rounds to go, too many friends in need.

“You gotta do whatchya gotta do. Hang in there. You can’t fight destiny.”

Related Articles

- World Heavyweight Boxing Championship 1960-1975 (sportales.com)

- Top ten hardest punchers in boxing history (trueslant.com)

- Foreman gains respect even in losing title (jta.org)

- Liston and Ali: the Ugly Bear and the Boy Who Would Be King by Bob Mee: review (telegraph.co.uk)

Requiem for a Heavyweight, the Ron Stander Story

This is the first story I wrote about Omaha sports legend Ron Stander, a journeyman heavyweight boxer who got his Rocky and Great White Hope moment in the sun when he fought reigning world champion Joe Frazier for the title in the challenger’s adopted hometown of Omaha, Neb. My story appeared some 30 years after that 1972 bout in which Frazier bloodied and bruised but did not knock down Stander. The fight was called after four rounds. As a fighter, Stander was strong and brave and always stood a puncher’s chance. But he forever sabotaged whatever chance he had to be a legit heavyweight contender by the way he conducted his life, which was to overeat and drink and recreate and to avoid training whenever possible. He paid for that lack of discipline in a number of ways, both professionally and personally. But the reason why people have always loved Stander is that he’s a sweet, generous Every Man whose triumphs and struggles we can identify with. At the time I wrote this article he was somewhat a sad, down-and-out figure. More recently, his life has taken an upswing I am happy to report. I understand he’s now writing his life story. It should be one helluva read.

Requiem for a Heavyweight, the Ron Stander Story

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the defunct Omaha Weekly

It is tempting to cast local boxing legend Ron “The Bluffs Butcher” Stander in the role of a heavyweight in need of a symbolic requiem. A certain sadness surrounds this one-time contender who, since retiring from the ring in 1982, has often battled opponents he could not lay a glove on — including himself. While this smart ex-pug is no permanent resident of Palookaville and clearly still has all his wits about him, he does fit the part of a man haunted by having had the world in the grasp of his beefy hands only to let it all slip away.

Like some real-life Rockyesque figure, this hometown Great White Hope was just another up-and-coming club fighter when he got a once-in-a-lifetime chance to fight for the heavyweight championship of the world. It happened 30 years ago right here in Omaha, Neb. On May 25, 1972 he squared-off with “Smokin” Joe Frazier at a jam-packed Civic Auditorium. What transpired next has defined Stander ever since. Unlike the fictional “Rocky,” his moment in the sun ended not in fame or fortune but as the answer to a trivia question: “The last fight Frazier fought as champion? It was against me,” Stander will tell you at the drop of a hat.

Before sitting down for a recent interview at the comfortable south Omaha home he shares with his second wife Becky and their two children, he excused himself, saying, “I have to put my teeth in,” referring to the denture plate he inserts to replace the many ivories he lost over the course of his ring life. Reposed in a recliner, his fleshy face a contour map of scars and crevices, he spoke about the Frazier fight and its implications in his life.

For four brutal rounds the local slugger stood toe-to-toe with the fierce Frazier, then only months removed from having beaten Muhammad Ali in the first of their epic fights, and traded body blows and head butts with him. They were like two big-horned antelope locked in mortal combat, neither giving an inch. “We could have fought the fight in a telephone booth,” is how Stander describes it. The challenger got in a few good licks, even stunning the champ in the 1st, but by the time the bell sounded to end round 4 his pasty face was a bloody, swollen mask. Ringside physician Dr. Jack Lewis put a stop to the slaughter before the start of the 5th.

Heavyweight champion Joe Frazier (left) lands a punch against challenger Ron Stander during their May 25, 1972, title bout at the Omaha Civic

Local boxing fans fondly recall Stander’s courage in waging war the way he did. It was a frontal assault all the way, as he absorbed multiple blows just to connect one or two. His friend and former matchmaker, Tom Lovgren, said, “Ron Stander was not going to be embarrassed. He was not going down at the first thing that came close. He had a heart the size of a house. He’d walk right at you.”

Never one to pull his punches, even when discussing himself, Stander said, “As far as taking several punches to land one, that’s not the smartest thing. It was more a result of my short height and short reach.” Despite all the techniques and strategies he was taught over the years, in the heat of battle the Butcher always returned to his unschooled, bull-rush style. “You resort back to whatever comes natural to you, I guess,” he explained. “I was just a slugger. I was very aggressive.”

Much like he fought, Stander approached life head-on also, over-indulging in food and drink, taking risks, making rash decisions, leading with his chin and heart instead of keeping his guard up. He paid the price, too. His tempestuous first marriage ended in divorce. He became estranged from his first two children and his grandchildren. There were much publicized drunken driving offenses, the second of which landed him in a men’s reformatory and a detox unit for several months (“That was pretty bad.”) There was the failure of his Council Bluffs watering hole, The Sportsman’s Bar. His weight ballooned to nearly 300 pounds.

He lingered far past his prime as a prizefighter, hoping against hope another big pay day would emerge. It never did. He entered the title fight with a promising 21-1-1 record, including 15 KOs, and staggered to a disappointing 14-19-2 mark after it, often going into fights poorly conditioned and mentally unprepared. Near the end, Lovgren refused putting him in with heavy hitters or expert boxers for fear his fighter might be badly hurt. Friends feel Stander hung on too long. “Yeah, that’s probably true,” the Butcher said. “You know when you’re almost done. You don’t have the desire or the hunger. You’re tired of the roadwork. You’re tired of working out all the time. The stitches start mounting up. Your nose gets a little flatter. Your teeth get a little looser. Your brain gets a little more giggled. You just lose it. But a guy’s gotta have money. It wasn’t like I was earning a pension working for U.P. (Union Pacific).” He was a fighter. That’s all he knew.

Along the way, he was exposed to the seamier side of boxing. While training back east he met some wise guys who had their hooks into boxers. He heard stories of fighters refusing to take dives being thrown off a pier or getting their hands busted with hammers. “Yeah, it happened,” he said. “There’s a lot of backstabbers in boxing.” Then there’s the whole dirty business of being a gladiator under contract, which is like being an indentured servant. He got only a small piece of the financial pie. “Everybody gets their hands in the till, see? I got $100,000 for the Frazier fight and I only came home with $40,000 by the time my manager took his cut, somebody else took his and the IRS took theirs,” he said. On three occasions his contract was bought outright by managers in other states and he had no choice but to pack-up, relocate and take his marching orders from a new boss. “You move to their town, you train in their gym, you fight in their fights and they take half,” is how he put. All in all, though, he feels he was well treated, especially by Noland and Lovgren. “They did right by me.” One of the quirks of being a once-name fighter is hanging out with sports icons. On several occasions he was with Ali as The Greatest prepared for fights. He witnessed him practicing pre-fight poetry out loud like an actor running his lines and lording over his entourage like some sultan overseeing his minions. He was with a young Mike Tyson (of whom he does a dead-on impression) in Las Vegas. He chummed around with pro wrestlers like Jesse “The Body” Ventura. He made friends with such ringside characters as Cus D’Amato and Bruce “The Mouse” Strauss.

With the perspective of time, Stander now blames his many travails on the deep funk he says he descended into after losing the title shot. “After the Frazier fight I was really depressed. I wanted to win so bad,” This once hometown hero became seemingly overnight, a has-been. Upon his retirement he stayed on the fringes of the game refereeing bouts and appearing on fight cards, where he was a bloated shadow of his former self. He searched in vain for something, anything, that could replace the rush of stepping into the ring to throw leather. For a while, alcohol became his elixir. It didn’t help when he endured the loss of his mother and step-father, who adopted him and whom he idolized. As a child the future boxer and his mother were abandoned by his biological father. He said when she remarried (getting hitched to Frank Stander, a hard working World War II vet who accepted Ron as his own) it “was the greatest thing that ever happened to me.”

With the help of his second wife, Becky — “She’s a doll” — with whom he has two boys, ages 11 and 13, Stander is clean and sober these days, but out of work. When a reporter recently read him a litany of his troubles and asked what went wrong, this man who never took a dive in the ring answered candidly about the hard fall he took after hanging up the gloves. “Yeah…yeah…yeah. Depression. Losing the Frazier fight. Yeah, that and stupidity. Probably irresponsibility. I made some wrong decisions. I didn’t know when to say no. I was like, ‘Let the party begin.’ When I had to go away (for rehab) it was like shock treatment. I was going to grow up sooner or later and maybe going away helped me to. Now, I just want to raise these two kids and enjoy my grandkids and try to be a role model and do the right thing. I have to show them the right way to go,” he said sheepishly.

When the Vicker’s plant closed a few years ago, Stander lost his well-paying machinist’s job there and has lately been attending Vatterott College’s heating and air conditioning school in an attempt to learn a new trade. He worries, though, how a man his age can find a job that will enable him to support a family. “People say, ‘Well, you can start over and work your way up again.’ Yeah, right. Whatever,” he said, sarcasm dripping from his tongue. “I’m ready to go, I’m ready to work. But people don’t want to hire ya when you’re my age. I talked to friends at Hawkins Construction and they said, ‘We’re looking for guys 35, not 55.’ I talked to a friend who’s in the heating and air business and he said, ‘Well, you know Ron, we don’t want someone your age up on a roof when it’s 120-degrees. You could have a heart attack. Heart attack, hell, I feel fine. I can fight Frazier tonight.”

Like many athletes who once enjoyed success and celebrity, Stander clings to the memory of his halcyon days as the popular hard-hitting heavyweight who, as Lovgren said, “put asses in seats better than anyone ever has in Omaha, Nebraska.” Lovgren, a boxing historian, feels Stander was “one of the last good heavyweights under 6’0 tall.” To be sure, Stander made some waves in the fight game. Early in his career he peaked at just the right time for a fight with the formidable Earnie Shavers, widely considered one of the hardest punchers ever in the heavyweight ranks, and knocked Shavers out in five. In total, he faced nine men who fought for the title, never ducking anyone. But he admits he often didn’t train as hard as he should have. According to Lovgren, Stander lacked a fire in his belly. “It was hard to get Ron enthusiastic about fighting,” he said. “When he fought for me I was on him all the time, but there was no inner drive, no fire in the furnace, except for certain fights. I don’t know why he didn’t have it. I tried talking to him about it. I tried playing mind games with him. I did everything I could do.”

As for himself, Stander holds fast to the dream of what-might-have-been glory days if he had only connected with one solid blow that fateful May night 30 years ago. There is still enough cockeyed machismo and never-say-die hope left in him that when discussing old ring rivals Joe Frazier, Ken Norton and Muhammad Ali, he says, not entirely facetiously, “I have all the respect in the world for those guys, but the simple fact is if we fight today — I knock ‘em out. I’d knock ‘em all three out in less than one round because of their poor physical condition. Frazier’s got diabetes. His weight’s down. His arms look kind of arthritic. Norton was in a coma for months after a car wreck. He can’t hardly walk now. Ali’s got Parkinson’s.” Then, as if catching himself in the absurdity of boasting over dismantling such debilitated old men, he added, “That and 50 cents will get you a cup of coffee.”

Stander, today a robust 57 with a big belly and forearms as hard and round as telephone poles, appreciates the irony of how he, the once prohibitive underdog, would now be the odds-on favorite, given the ravages of time, in imaginary pugilistic contests against these old greats. Even though his own post-boxing life has been anything but a joy ride, Stander is physically unscarred compared to his fellow warriors. And he undoubtedly could whip their asses today, too. A lot of good that does him now, though. The point is, as he knows all too well, is that “when it really counted — when all the money was on the line, it would have been different,” he said. “I would still have been a 10-1 underdog.” And he still would have lost for the same reasons he did when he fought Frazier and met Norton in a matchup of former contenders. The simple fact is Stander, even in his prime, had a bad penchant for being cut in the ring. Sure, he could take you out with one punch, but the slim chance of landing a haymaker made him a long shot against elite fighters, who pummeled him at will and invariably opened up gashes over his eyes from which blood obscured his vision. Cuts led to the early stoppage of both the 1972 title bout and his 1976 fight with Norton. He never faced Ali, but if he had the results would surely have been the same. Making matters worse, Stander was a notoriously slow starter and sometimes he had barely warmed up before cuts opened up and the fight was halted.

Like the tough guy he is, Stander still believes he could have taken out both Frazier and Norton if the fights hadn’t been stopped on account of what he calls “chicken shit cuts.” Indeed, anyone who worked with Stander will tell you he was not hurt during those fights or during any of his fights for that matter, that he was rarely dropped and that he was never counted out. Despite ineffective defensive skills, his massive neck, sturdy chin, heavy leather and refusal to go down made him a pain-in-the-ass for any foe. His losses could be attributed more to his poor training and his accursed propensity for bleeding than anything else. Of his legendary ability to knock men out cold and to stay on his feet, he said, “I was just blessed with it. You either have it or you don’t, I guess.”

That’s not to say Stander didn’t incur his share of punishment during his ring career. His injuries included an oft-broken nose, fractured hands, shattered teeth and myriad cuts requiring more than 200 stitches. His face is a kind of Frankenstein monster’s patchwork. He feels fortunate he avoided long-term damage. Therefore, he does not take lightly how his more famous fellow ex-practitioners of The Sweet Science have suffered physically in recent years. About Frazier, with whom he was reunited last summer for a Boys and Girls Club of Omaha promotion, he said he was shocked by how much the former champ has failed. “I’m not putting him down. I’m just telling you the facts. He had 41 brutal rounds with Ali. And Big George Foreman scrambled his brain, too. Frazier’s a mucho-macho champion, but all that pounding takes its toll on a guy. Norton hasn’t been right since his car wreck. And Ali, with his rope-a-dope tactics, took a lot of shots he shouldn’t have late in his career.”

Still, Stander, who once said, “I’ll fight any living human and most animals,” can’t resist, as crazy as it sounds, entertaining the notion of a seniors boxing circuit pitting him against the men who kept the crown out of his reach. “Let’s do it, please. Line it up,” he said, smiling at the thought of cashing-in once more on his God-given KO punch, stiff chin and brave heart. As ludicrous as it may be, boxing is given to extremes, whether it’s an ancient George Foreman returning to fight after a more than decade-long hiatus or Roberto Duran still mixing it up well into his 50s. He knows the fights he imagines can’t happen, of course, but it’s all he has to content himself with after missing out on boxing’s money parade. As he puts it, “I fought the title in 1972, B.C. — that’s before cash and before cable.”

He has watched the film of the Frazier fight countless times by now. Viewing it is part penance and part nostalgia. He trained hard, even staying with Lovgren and his family in the weeks preceding the action so that Lovgren could act as a kind of chaperon closely monitoring his roadwork, escorting him to and from the Foxhole gym where he trained under the watchful eye of Leonard Hawkins, supervising his diet and ensuring he did not stray far from home for nights out on the town. Lovgren can recall Stander giving him the slip only once to, presumably, go out and party. But even with Stander mostly attending to business, there were distractions galore. Fans clamored for his autograph. Old “friends” came out of the woodwork and pleaded for tickets. The media hounded him for interviews, ranging from the foreign press calling to even the venerable CBS newsman Heywood Hel Broun showing up at Lovgren’s doorstep one day with a camera crew in tow. Then there was the marital strife Stander and his then wife Darlene, who was widely quoted disparaging her husband’s chances, were coping with. Finally, there was the broken nose he suffered two weeks before the fight while sparring with “Mighty” Joe Young in Boston, where Stander trained for a time under Johnny Dunne.

It all got to be too much. “It was annoying and aggravating,” he said. “I just know there were some distractions. It was hard to concentrate. It was a mess. Plus, the anxiety of it. It was for all the marbles. The stress was a factor. Well, you know how they say — Never let them see you sweat? — well, you would have seen me sweating fight night. My armpits were wet. I was anxious, you know? I wasn’t scared. It was psychological. You were going to fight no matter what, but you were just tense. Ready to rumble.”

Then there was the pressure of the money involved. Win or lose, more jack was at stake than he he had ever seen before. His share was $100,000 where his previous best pay day was maybe $1,500. Should he have won, he knew he could command riches even far beyond that. As it was, the money disappeared all too soon and he would never take home more than $5,000 for a fight again.

Another factor rarely mentioned in accounts of the fight was the huge disparity in experience between the two combatants. Frazier had been a world class amateur competitor, winning America’s only boxing gold medal at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Heading into the Stander fight his pro career saw him face one leading contender after another in top venues like Madison Square Garden. By contrast, Stander had a limited amateur career against mostly local foes and as a pro had fought, with few exceptions, much lesser lights than Frazier. Then there was the fact Frazier routinely sparred with top flight men in Philadelphia’s talent-rich boxing gyms while Stander made do with whomever he could find here. In short, Frazier outclassed Stander in every way. “Experience was a big part of it,” said Stander. “I had less than 40 fights, amateur and pro combined whereas Frazier had 100-some fights. I turned pro in ‘69 and then in ‘72 I fought for the title.” So, was it a classic case of too much, too soon? “Yeah…maybe,” he said.

That the fight came off at all was a golden opportunity for Stander, plus a coup for his manager, the late Dick Noland, and for matchmaker Lovgren, who were the president and vice-president, respectively, of the now defunct Cornhusker Boxing Club. Negotiations for the event, Omaha’s first and last title card, bogged down at one point, Lovgren said, over the size of the take that Stander and his people would get. Frazier’s camp wanted the lion’s share and only when syndicated national television entered the picture and anteed up big bucks for the live broadcast rights did enough money appear on the table to satisfy both parties.

Regardless of whether Stander was a worthy opponent for Frazier, he was a natural choice because he fit the bill for what the champ’s camp was looking for in a last tuneup before the Frazier-Foreman bout: First, Stander was an action fighter who would eagerly mix it up with the champ and therefore give him a good workout and provide some crowd-pleasing moments; next, he was prone to cuts and so the odds were good the fight would not go anywhere near the distance; and, finally, he was a popular white contender — when that was fast-becoming an endangered commodity in a division dominated by African-Americans — who would attract enough fans to guarantee a nice pay day. Stander gave them just what they wanted, too. He fought gamely, he bowed out before Frazier got in any real danger and he helped fill the auditorium and generate a nearly quarter million dollar gate.

If his later career was a letdown, there were some highlights. Perhaps his most satisfying post-Frazier bout came in 1975 when he knocked out Terry Daniels in the first round. Daniels, another White Hope, had also lost to Frazier and by destroying him Stander hoped to proved that he was still “a legitimate contender.” That win helped him secure the matchup with Norton but after losing that one he never fought a marquee fight again.

All these years later Stander’s still slugging it out, only now his fight is about trying to make a go of it as a middle-aged blue collar breadwinner amid a landscape of layoffs, cutbacks and tough times. He sometimes wonders what-might-have-been had fortune turned the other way in his life. “As good as you are and as hard as you work, you need a little bit of luck on top of everything else. Things just never happened for me. Now, I’m lookin’ for a job.” But at least when he’s low he can always take heart in the fact he once fought for the most coveted title in boxing. “It’s the biggest sporting event for one man in the world. It was a great time.” That and 50 cents will get you a cup of coffee.

Related Articles

- World Heavyweight Boxing Championship 1960-1975 (sportales.com)

- Heavyweight Boxing Division Losing Popularity to Lighter Weights (bleacherreport.com)

- Great White Hope: Not Great, Little Hope Against Johnson (nytimes.com)

- Requiem for a Fake Heavyweight (popculturehasaids.wordpress.com)

- 40 Years Later, Ali-Frazier Still An MSG Classic (newyork.cbslocal.com)

- Was “The Fight of the Century” the Greatest Sporting Event of All Time? (bleacherreport.com)

Fight Girl Autumn Anderson

I have to admit that when I saw an article about a female boxer in Omaha it was her picture, a provocative image of an attractive young woman, more than her story that enticed me to want to meet her and profile her for a local paper. When I met her at the gym she trains at she turned out to be every bit as good looking as that picture suggested but she was not at all stuck on herself or her good looks. Instead, I found a hard working athlete and U.S. Army Reservist who is dedicated to her sport and to her military commitment, and someone who has some high level goals she wants to achieve. She’s very much aware of how people perceive her and she’s quite smart about how she deals with all that. My story about her originally appeared in the Omaha City Weekly (www.omahacityweekly.com), a now defunct newspaper.

Fight Girl

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the City Weekly (www.omahacityweekly.com)

By rights, Autumn Anderson shouldn’t be boxing. Even ignoring the propriety of women duking it out, she doesn’t fit the fight girl profile. Not this bumble gum Reese Witherspoonesque blond whose self-described “girly-girl” good looks earn her modeling gigs. In nothing more revealing than a bikini in case you’re wondering.

Still, the 22-year-old Omahan looks more like the ring card girl than the main event fighter. More soft and feminine than chiseled bad ass.

“Every time, it works to my advantage,” she said, “especially with the black and Hispanic girls because they’re like, ‘White girl, huh — oh, she thinks she’s tough?’”

On close inspection Anderson’s hard, compact body is anything but delicate. Her 15-9 record backs up her ability to handle herself inside the ropes. Still, why risk such a pretty face in the ring? She’s heard it all before from her parents.

Her answer explains why she got into boxing to begin with.

“I kind of wanted to prove to people females could do anything they put their minds to,” said Anderson, who took up the sport at 16, “because a lot of males especially doubt women and their abilities, especially physical abilities.”

A one-time competitive swimmer and runner, she craved “something with contact” — that challenged her toughness on a more instinctual level.

“I wanted to do a more individual sport. Something more aggressive,” she said.

Her commitment to boxing’s been tested by the only two long-term boyfriends she’s had and the only prolonged layoff she’s taken from boxing.

“It’s always my boyfriends being like,“‘Why do you box?’ Blah-blah-blah. My first one convinced me not to. I’d go to the gym, there’d be all guys, and so it’d make him insecure. It made me not want to go because it made him uncomfortable. Then we broke up and then I got back into it like hardcore.”

She said there’s no reason a man should feel threatened by what she does. “When I go to the gym I dress like a guy. I don’t wear short-shorts or tank tops to show off anything. I wear bandanas. I don’t let my hair down. I’m here for business. I’m not here to like pick-up guys or to be distracting. I’m more like a tomboy.”

Anyone who’s a drag on her dreams, which include Olympic glory, she cuts loose, with the exception of her folks, who’ve since come around to support her.

“Everything’s a life-learning experience, especially when you have opportunities and somebody’s holding you back and they don’t support you,” she said. “You just have to let them realize you’re going to follow your dreams and nothing’s going to stop you. I’m pretty stubborn. If somebody feels I can’t do something, I have to prove them wrong.”

Despite proving doubters wrong boxing still seems an unlikely choice. Besides her cover girl puss there’s her background, which reads more Girl-Next-Door idyll than Girl-from-Ghetto trial.

Raised by a single mom, she’s technically from a broken home, but it’s not like she grew up scratching and clawing her way out of the projects. No, she grew up in the burbs of Kansas City, Mo. and Baltimore, Md. She says almost apologetically that she’s never been in a fight outside the ring.

She’s been on her own since age 16, first in Nebraska City, where she lived with an older sister, later with friends, and then in Omaha. Her first boxing mentor was a crusty old coach in Sidney, Iowa. Then she was taken by the late Kenny Wingo at the famed Downtown Boxing Club here.

Whatever gym she landed in it was always the same — show us you belong.

“That’s what they always do with a new girl,” she said. “They want you to get in the ring and spar and see if you have any heart. See if you’ll last. If you get your butt kicked once, are you going to quit. So, I’ve gotten beat-up a couple times, and I kept coming. I just fell in love with the sport.”

Her ringworthy rite-of-passage was more difficult than most.

“I definitely didn’t grow up fighting people in the streets, which is different than a lot of boxers. I had to learn to be mean. I had to learn to be aggressive.”

Hitting girls in the face didn’t come naturally for Anderson, who was into ballet and modeling from a young age. She’s always been athletic, but before boxing the most physical things she’d done were dancing, running and swimming.

When that guy she later dumped got her to hang up her gloves for a whole year, she ran cross country and track at William Penn College (Iowa). But, she said, “something was missing in my life. I was like, ‘Man, this is boring,’ I came back to boxing.” Not exactly a classic path to the Sweet Science. That’s not all that defies expectations about her. Anderson’s a full-time college student majoring in real estate and economics at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. She’s intent on getting her master’s in business administration.

She’s also a sergeant in the U.S. Army Reserves. This Motor Transportation Operator in the 443rd Transportation Company in Omaha does her battle assembly drills and training on weekends. She does her amateur fighting thing both inside and outside the confines of the Army, which has made her a poster girl.

The goarmy.com web site profiles Anderson’s multi-faceted life as reservist, student, boxer and young woman-going-places. She looks fetching in a portrait shot with an American flag backdrop. She stands tall, all 5-foot-5 of her, wearing a red tank top, her arms folded across her chest, her long blond hair framing her determined face and her gloves fecklessly slung over one shoulder. It’s a strong, sexy, confident, patriotic image.

Other photos show her in her Army fatigues and dress blues. She said snippets from the promo can be seen in GoArmy television spots. She felt like a pampered star when last July the Army sent a large production crew to the house she shares. “It took two days, about 12 hours each day. They did my hair and makeup,” she said.

“It’s a cool story for people who are interested in the Army,” she said.

Portraying her as a warrior is not a stretch. Not when you see her throw some leather in the ring. She can bring it. She’s tough enough to own the nation’s No. 5 women’s amateur ranking at 132 pounds. That ranking’s significance is debatable given the few women in the sport. But watch her spar and it’s clear she packs some power and possesses more than rudimentary skills. She has serious intent.

When not competing in Army tournaments she trains at the Northside Boxing Club in northwest Omaha. It’s an apt setting, given that the gym operates from one of the low-slung concrete block structures, Building 203, that housed elements of a former U.S. Air Force radar base. These days the multi-acre fenced-in compound at 11000 North 72nd Street belongs to construction Local Labor Union 1140.

While in training she’s at the gym five times a week. She’s now preparing for the August 4-9 Ringside World Amateur Boxing Championships in K.C., a signature event for a young woman with high aspirations.

My dream is to be a national champion and to fight in the Olympics,” she said.

Turning pro is another goal. Laila Ali has shown that talent and looks in the ring can lead to fame and fortune. But Anderson wants that trophy or medal first.

A national title may soon be within her reach. The Olympics will have to wait as its international governing body has not sanctioned women’s boxing. She hopes girl fighters like herself get their chance at the 2012 summer games.

Female boxing’s a fringe thing. Women’s Golden Gloves is still in its infancy. The small number who compete makes it difficult finding matches. Anderson’s fought one girl five times. To get action she must often travel. One of her last Nebraska fights stole the show on a 2007 Melee at InPlay card.

Sparse local/regional competition makes any national or international boxing event that much more important to her ambitions of being a title holder. Actually, she already owns one. She won the 2007 Armed Services Championships’ 132-pound division at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas. But she acknowledges she didn’t have the stiffest draw and captured the title on the basis of only two wins, both against fellow servicewomen. No, the championship she really wants is a civilian one, in an open tourney like Ringside that features more top drawer talent.

Her coaches, led by former Omaha amateur boxer Tim Pilant, had high hopes for her in the National Women’s Golden Gloves tourney earlier this year but she got sick and didn’t make the trip. Two years before Anderson stopped one opponent at these same nationals before dropping a 5-0 decision in her second bout.

Pilant, who runs the Northside Boxing Club with a crew of grizzled ring veterans, “adopted” Anderson three years ago at a national tourney in Colorado Springs when she didn’t have anyone working her corner. Her original coaches and boxing father figures had both died and she was competing on her own. Pilant cornered her and invited her to train at Northside back home. She’s been there ever since.

He admires her “commitment” and “dedication.”

To date, Anderson’s been stymied at the highest levels by two women who’ve dominated her weight class — Naquana Smalls and Carrie Barry. Smalls has since retired, leaving Barry as the foe Anderson must go through to realize her dream.

Preparing for her first nationals in 2003 Anderson saw a picture of Smalls, already a legend, and was, well, intimidated. “I remember looking at her face in the brochure and going, ‘Man, I hope I don’t fight that girl right away.’ She did. In the mismatch Smalls stopped her. She fared better with Barry but still lost a unanimous decision.

One day Anderson wants to be the woman nobody wants to face.

“That’s exactly right. I’ve actually built myself up that way. All you have to do is work towards it and it can be you. You just have to tell yourself it’s going to be you,” she said.

She may not ever be a Million Dollar Baby but her looks and her smarts, combined with her heart, should help her go the distance.

Related Articles

- NZ’s top women’s boxer could get world title fight (3news.co.nz)

- Sara Kuhn: Ready for her pro debut on September 11 (timesunion.com)

- Coloradans stand up and fight (denverpost.com)

- Canceled FX Boxing Show, ‘Lights Out,’ May Still Springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s Career (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Laila Ali Welcomes Second Child (bleacherreport.com)

- The Pit Boxing Club is an Old-School Throwback to Boxing Gyms of Yesteryear (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

University of Nebraska at Omaha Wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

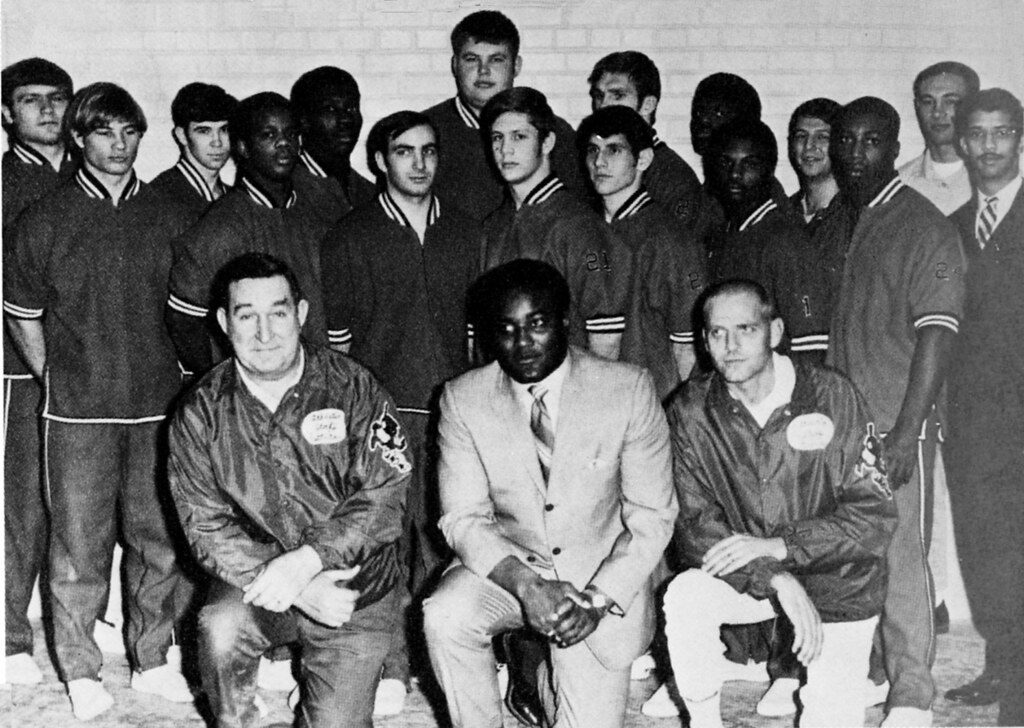

Don Benning, center front row, with his magnificent wrestling team

THE LATEST: Requiem for a Dynasty will be the headline, if I get an assignment to write the story that is, for what transpired as expected with the UNO wrestling program. As anticipated and despite the most heartfelt efforts of the program’s coaches, student-athletes, alums, and supporters the NU Board of Regents approved UNO’s proposed move to the Summit League and NCAA Division I competition and with it the elimination of the wrestling and football programs. It’s a sad day for UNO when its administrators can discard history and tradition so easily for the sake of convenience. In this disposable culture two programs were thrown out as if they were useless refuse. Losing football hurts, but the rationale for excising it ultimately makes sense because it was never going to come close to making money. Dumping wrestling though to purportedly be in better alignment with the Summit League is pure hogwash. It’s really UNO and NU leaders saying that they don’t give a rat’s ass about wrestling, that they don’t really care about all the championships, the scores of All-Americans, the prestige, the community service, the lessons learned, the incredibly strong and tight family bond built up across generations. They don’t care that UNO hosted multiple national championships and the largest single day annual wrestling tournament in the country. Why not give a damn about those things universities are there to provide its student-athletes and constituents? My take is that no matter how much UNO wrestling achieved, and it achieved so very much, it was never accorded the respect or due it deserved. Not by the regents, not by administrators, not by major university donors, not by the media, not by the general public. It was always considered marginal and therefore expendable. When things got tight, UNO wrestling was an easy target despite being a dynasty. That sends a disturbing, dysfunctional message to anyone really paying attention.

Getting rid of wrestling was painless for the regents because it was done in the abstract. By the time the UNO wrestling community appeared before them to plead their case that the program be retained, by the time all the appeals and messages had been made via email and phone, the regents had already made up their minds. The March 25 hearing was perfunctory. It was a show to merely let wrestling vent and have its say in an open forum. If the regents had bothered to actually visit the UNO wrestling room and to see first-hand the sweat and blood and tears and love and joy that went into making the dynasty, then the program might have had a fair day in court, so to speak. If the regents had seen for themselves the championship banners and the roll calls of All-Americans and soaked up the atmosphere of excellence imbued in that room, it might have been a different story. Or not. This was a business decision made by UNO and given the thumbs up by the regents. Cold, calculated business. The administrators and the regents simply didn’t get it or didn’t want to get it. They would not be moved by emotion or history. To the end, the UNO wrestling family fought gallantly, never breaking ranks, always showing class, the bonds that hold them together more powerful than any bureaucratic decree, extending beyond the now ended program. UNO wrestling may be gone, but its spirit lives on. The relationships between the men forged in that room and in those duals and tournaments and in all the time spent on the road and cutting weight and hanging out will endure.

NEW UPDATE: With each passing day any window of opportunity for UNO wrestling to be saved grows smaller. Unless something dramatic should happen between now and March 25th, it appears likely then that the NU Board of Regents will approve the plan advanced by University of Nebraska at Omaha Chancellor John Christensen and Athletic Director Trev Alberts for UNO to move to Division I and to drop football and wrestling in the process. As a graduate of UNO, as a former Athletic Department staffer, as a UNO sports fan, and as a writer I have a perspective to offer many don’t. Football certainly has a longer tradition than wrestling at the school, but when it comes to sustained success there’s no comparison. Don’t get me wrong, I will miss UNO football. I variously kept stats at and cheered at probably a hundred home games over the years. Caniglia Field is a great venue to watch a game at and UNO consistently plays at a high standard . UNO football’s been one of the best entertainment bargains in the city. But the sad truth is the program rarely drew well and even if IUNO football came along for the ride to D-I there’s little reason to expect it would draw any better at that level. UNO football has had its share of winning but it’s never won a national title and generally failed in the post-season, on the biggest of stages. UNO wrestling is a whole different story. It has been an elite program for more than 40 years. It’s won multiple national titles, produced scores of All-Americans, and basically been the best D-II program over the past 20 years. No, it’snot a big draw, although by wrestling standards it does quite well, but in terms of national prestige UNO is one of the best things the university has going for it, period. The crazy thing is that the UNO administration makes clear it’s not finances driving the proposed elimination of wrestling and football, which gets at the heart of it: UNO administrators don’t care about the excellence that UNO football and particularly UNO wrestling represents. It’s inconceivable it is prepared to walk away from something so successful, but that is what is about to happen.

Therefore, it seems like a good idea to look back at the wrestling program’s early years in order to gain an appreciation for where it came from and the significance it had at a tempestuous time in the university’s and in the city’s and in the nation’s history. The story of what Don Benning and his wrestlers did to put UNO on the map and to make UNO wrestling a champion is one of the great legacies of the university, and one it has never really embraced or celebrated to the extent it deserves. Sadly, wrestling at the school has always been viewed as marginal and expendable, and the words and actions of the UNO administration today bear that out. So check out the story below — it’s my take on the tide of social change that UNO’s glorious wrestling program is built on. I wrote it early last year for The Reader, as UNO prepared to defend its national title, which it did, and did again this year. It’s sad to think the story may now be the Requiem for a Dynasty.

UPDATE: Trev Alberts has been putting his stamp on the University of Nebraska at Omaha Athletic Department since his from left-field arrival in the job of athletic director two years ago. Chancellor John Christensen hand-picked Alberts to lead a revitalization of UNO athletics and Alberts has surprised many by just how bold his moves have been — from hiring Dean Blais as head hockey coach to getting major donors whose support had waned to ante up big again for capital improvements. And now as the Omaha World-Herald is reporting Alberts and Christensen are about to shake the foundation of the school and the athletic department by moving UNO into Division I competition across the board — pending University of Nebraska Board of Regents approval — by joining the Summit League. The news of going D-I isn’t that big a surprise in and of itself, as UNO has made clear for more than a decade that is where it wanted to go, but what is is UNO doing it so soon and its decision that in order to make it work long-term it must sacrifice the school’s two winningest sports — football and wrestling. Alberts and Christensen say they and others have worked the numbers and the only way UNO can justify the leap into the big-time is by dropping the heavy financial burden of football, whose weight would only increase with the increased scholarships and improved facilities D-I necessitates. Besides, where football is a revenue generator at many schools it is not at UNO and even the prospect of D-I would likely do little for the program’s mass appeal given the shadow of Big Red. But the real shocker is that UNO is prepared to jettison its shining star, wrestling, whose program just captured its eighth national title over the March 11-12 weekend. UNO could choose to go independent in wrestling but the school is opting not to do that, which is odd because it’s perhaps the least financially onerous men’s program in terms of scholarships, equipment, travel, facilities. But more to the point — how do you just dismiss the incredible success that UNO wrestling has achieved? I would hope that UNO finds a way to preserve the wrestling program. For a look at some of its remarkable history, see my story below about how the UNO wrestling dynasty is built on a tide of social change. You can also find on this blog my stories about Don Benning, the coach who began UNO’s wrestling dynasty, and about Trev Alberts, who may go down as the man who took down that same dynasty.

It may be a moot point in the end, but the UNO wrestling program is not going down without a fight. Coaches, student athletes, alums, fans, and boosters gathered at UNO Sunday, March 13 in the wake of the startling announcement that the wrestling program will be disbanded. Coach Mike Denney was seen calmly addressing the gathering and coalescing support. In an interview he gave a local TV sports reporter he pointed out that some schools in the Summit League that UNO has been invited to join do have wrestling programs. Denney asked the question a lot of people are asking: If they can be in that league and keep wrestling, then why can’t we do it? UNO Chancellor John Christensen and Athletic Director Trev Alberts apparently came to this decision without consulting Denney or the UNO wrestling community or UNO student leaders. The two men are undoubtedly acting out of good intentions and in the long term interests of the school but to spring this decision without warning and without giving Denney and his assistant coaches and student-athletes the opportunity to weigh in and argue against it is cruel and ill-advised. I would not be surprised if Don Benning adds his voice to the chorus of disapproval over Christensen’s and Albert’s decision to throw away the history and tradition that UNO wrestling represents.

________________________________________________________________________________

In my view, one of the most underreported stories coming out of Omaha the last 50 years was what Don Benning achieved as a young black man at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. At a time and in a place when blacks were denied opportunity, he was given a chance as an educator and a coach and he made the most of the situation. The following story, a version of which appeared in a March 2010 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com), charted his accomplishments on the 40th anniversary of making some history that has not gotten the attention it deserves.

One of the pleasures in doing this story was getting to know Don Benning, a man of high character who took me into his confidence. I shall always be grateful.

University of Nebraska at Omaha Wrestling dynasty built on tide of social change

©by Leo Adam Biga

Version of story published in a March 2010 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

As the March 12-13 Division II national wrestling championships get underway at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, it’s good to remember wrestling, not hockey, is the school’s true marquee sport

Host UNO has been a dominant fixture on the D-II wrestling scene for decades. Its No. 1-ranked team is the defending national champs and is expected to finish on top again under Mike Denney, the coach for five of UNO’s six national wrestling titles. The first came 40 years ago amid currents of change.

Every dynasty has a beginning and a narrative. UNO’s is rooted in historic firsts that intersect racial-social-political happenings. The events helped give a school with little going for it much-needed cachet and established a tradition of excellence unbroken now since the mid-1960s.

It all began with then-Omaha University president Milo Bail hiring the school’s first African-American associate professor, Don Benning. The UNO grad had competed in football and wrestling for the OU Indians and was an assistant football coach there when Bail selected him to lead the fledgling wrestling program in 1963. The hire made Benning the first black head coach of a varsity sport (in the modern era) at a predominantly white college or university in America. It was a bold move for a nondescript, white-bread, then-municipal university in a racially divided city not known for progressive stances. It was especially audacious given that Benning was but 26 and had never held a head coaching position before.

Ebony Magazine celebrated the achievement in a March 1964 spread headlined, “Coach Cracks Color Barrier.” Benning had been on the job only a year. By 1970 he led UNO to its first wrestling national title. He developed a powerful program in part by recruiting top black wrestlers. None ever had a black coach before.

Omaha photographer Rudy Smith was a black activist at UNO then. He said what Benning and his wrestlers did “was an extension of the civil rights activity of the ’60s. Don’s team addressed inequality, racism, injustice on the college campus. He recruited people accustomed to challenges and obstacles. They were fearless. Their success was a source of pride because it proved blacks could achieve. It opened the door for other advancements at UNO by blacks. It was a monumental step and milestone in the history of UNO.”

Indeed, a few years after Benning’s arrival, UNO became the site of more black inroads. The first of these saw Marlin Briscoe star at quarterback there, which overturned the myth blacks could not master the cerebral position. Briscoe went on to be the first black starting QB in the NFL. Benning said he played a hand in persuading UNO football coach Al Caniglia to start Briscoe. Benning publicly supported efforts to create a black studies program at UNO at a time when black history and culture were marginalized. The campaign succeeded. UNO established one of the nation’s first departments of Black Studies. It continues today.

Once given his opportunity, Benning capitalized on it. From 1966 to 1971 his racially and ethnically diverse teams went 65-6-4 in duals, developing a reputation for taking on all comers and holding their own. Five of his wrestlers won a combined eight individual national championships. A dozen earned All-America status.

That championship season one of Benning’s two graduate assistant coaches was fellow African-American Curlee Alexander. The Omaha native was a four-time All-American and one-time national champ under Benning. He went on to be one of the winningest wrestling coaches in Nebraska prep history at Tech and North.

Benning’s best wrestlers were working-class kids like he and Alexander had been:

Wendell Hakanson, Omaha Home for Boys graduateRoy and

Mel Washington, black brothers from New York by way of cracker GeorgiaBruce “Mouse” Strauss, a “character” and mensch from back East

Paul and Tony Martinez, Latino south Omaha brothers who saw combat in Vietnam

Louie Rotella Jr., son of a prep wrestling legend and popular Italian bakery family

Gary Kipfmiller, a gentle giant who died young

Bernie Hospokda, Dennis Cozad, Rich Emsick, products of south Omaha’s Eastern European enclaves.

Jordan Smith and Landy Waller, prized black recruits from Iowa

Half the starters were recent high school grads and half nontraditional students in their 20s; some, married with kids. Everyone worked a job.

The team’s multicultural makeup was “pretty unique” then, said Benning. In most cases he said his wrestlers had “never had any meaningful relationships” with people of other races before and yet “they bonded tight as family.” He feels the way his diverse team came together in a time of racial tension deserves analysis. “It’s tough enough to develop to such a high skill level that you win a national championship with no other factors in the equation. But if you have in the equation prejudice and discrimination that you and the team have to face then that makes it even more difficult. But those things turned into a rallying point for the team. The kids came to understand they had more commonalities than differences. It was a social laboratory for life.”

“We were a mixed bag, and from the outside you would think we would have a lot of issues because of cultural differences, but we really didn’t,” said Hospodka, a Czech- American who never knew a black until UNO. “We were a real, real tight group. We had a lot of fun, we played hard, we teased each other. Probably some of it today would be considered inappropriate. But we were so close that we treated each other like brothers. We pushed buttons nobody else better push.”

“We didn’t have no problems. It was a big family,” said Mel Washington, who with his late brother Roy, a black Muslim who changed his name to Dhafir Muhammad, became the most decorated wrestlers in UNO history up to then. “You looked around the wrestling room and you had your Italian, your whites, your blacks, Chicanos, Jew, we all got together. If everybody would have looked at our wrestling team and seen this one big family the world would have been a better place.”

If there was one thing beyond wrestling they shared in common, said Hospodka, it was coming from hardscrabble backgrounds.

“Some of the kids came from situations where you had to be pretty tough to survive,” said Benning, who came up that way himself in a North O neighborhood where his was the only black family.

The Washington brothers were among 11 siblings in a sharecropping tribe that moved to Rochester, N.Y. The pair toughened themselves working the fields, doing odd-jobs and “street wrestling.”

Dhafir was the team’s acknowledged leader. Mel also a standout football lineman, wasn’t far behind. Benning said Dhafir’s teammates would “follow him to the end of the Earth.” “If he said we’re all running a mile, we all ran a mile,” said Hospodka.

Having a strong black man as coach meant the world to Mel and Dhafir. “Something I always wanted to do was wrestle for a black coach. It was about time for me to wrestle for my own race,” said Mel. The brothers had seen the Ebony profile on Benning, whom they regarded as “a living legend” before they ever got to UNO. Hospodka said Benning’s race was never an issue with him or other whites on the team.

Mel and Dhafir set the unrelenting pace in the tiny, cramped wrestling room that Benning sealed to create sauna-like conditions. Practicing in rubber suits disallowed today Hospodka said a thermostat once recorded the temperature inside at 110 degrees and climbing. Guys struggled for air. The intense workouts tested physical and mental toughness. Endurance. Nobody gave an inch. Tempers flared.

Gary Kipfmiller staked out a corner no one dared invade. Except for Benning, then a rock solid 205 pounds, who made the passive Kipfmiller, tipping the scales at 350-plus, a special project. “I rode him unmercifully,” said Benning. “He’d whine like a baby and I’d go, ‘Then do something about i!.” Benning said he sometimes feared that in a fit of anger Kipfmiller would drop all his weight on him and crush him.

Washington and Hospodka went at it with ferocity. Any bad blood was left in the room.

“As we were a team on the mat, off the mat we watched out for each other. Even though we were at each other’s throats on the wrestling mat, whatever happened on the outside, we were there. If somebody needed something, we were there,” said Paul Martinez, who grew up with his brother Tony, the team’s student trainer-manager, in the South O projects. The competition and camaraderie helped heal psychological wounds Paul carried from Vietnam, where he was an Army infantry platoon leader.