Archive

Beware the Singularity, singing the retribution blues: New works by Rick Dooling

Slaying dragons: Author Richard Dooling’s sharp satire cuts deep and quick

The best writing challenges our preconceptions of the world, and Rick Dooling is an author who consistently does that in his essays, long form nonfiction, and novels. He’s also a screenwriter. If you know his work, then you know how his language and ideas stretch your mind. If you don’t know his work, then consider this a kind of book club recommendation. I promise, you won’t be disappointed. The following piece I did on Dooling appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) a couple years ago upon the release of his book, Rapture for the Geeks, When AI Outsmarts IQ. The work reads like a cross between a love ballad to the wonders of computer technology and a cautionary tale of that same technology one day overtaking humans’ capacity to control it. Around this same time, a suspenseful, supernatural film Dooling wrote the screenplay for from a Stephen King short story, Dolan’s Cadillac, finished shooting. Dooling previously collaborated with King on the television miniseries, Kingdom Hospital. Dooling is currently working on a TV pilot.

You can find more pieces by me on Rick Dooling, most efficiently in the category with his name, but also in several other categores, including Authors/Literature and Nebraskans in Film.

Beware the Singularity, singing the retribution blues: new works by Rick Dooling

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

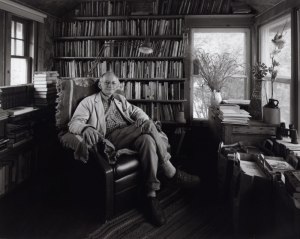

It’s been awhile since Omaha writer Rick Dooling, author of the novels White Man’s Grave and Brainstorm, enjoyed this kind of traction. Fall 2008 saw published his cautionary riff Rapture for the Geeks: When AI Outsmarts IQ (Harmony Books). His screen adaptation of Stephen King’s short story, Dolan’s Cadillac, will soon be released as an indie feature. Dooling, collaborator with King on the network television series Kingdom Hospital, was flattered the master of horror himself asked him to tackle Dolan, a classic revenge story with supernatural undertones.

Dooling’s no stranger to movie-movie land. His novel Critical Care was adapted into a Sidney Lumet film. The author was preparing to adapt Brainstorm for Alan J. Pakula when the director died in a freak accident. Then there was the creative partnership with King. But writing books is his stock-in-trade, and even though Dolan could change that, Rapture’s what comes to mind in any appreciation of Dooling.

Like much of his socially conscious work Rapture’s a smart, funny, disturbing, essay-like take on a central conflict in this modern age, one that, depending on your point of view, is either rushing toward a critical tipping point or is much ado about nothing. He fixes on the uncomfortable interface between the cold, hard parameters of computer technology’s increasing sophistication and meta-presence in our lives with existential notions of what it means to be human.

High tech’s ever more integrated in our lives. We rely on it for so many things. Its systems grow faster, more powerful. Dooling considers nothing less than humankind nearing an uneasy threshold when the artificial intelligence we’ve engineered surpasses our own. He lays out how the ongoing exponential growth of super processing capabilities is a phenomenon unlike any other in recorded history. The implications of the singularity, as geeks and intellectuals call this moment when interconnected cyber systems outstrip human functioning, range from nobody-knows-what-happens-next to dark Terminator-Matrix scenarios.

A fundamental question he raises is, Can the creators of AI really be supplanted by their creation? If possible, as the book suggests it is, then what does that do to our concept of being endowed with a soul by a divinity in whose image we’re made? Is synthetic intelligence’s superiority a misstep in our endeavors to conquer the universe or an inevitable consequence of the evolutionary scheme?

“Well, we all know what evolution is. We’ve read about it, we understand it, it’s just that we always have this humancentric, anthropocentric viewpoint,” Dooling said. “Wouldn’t it make perfect sense there would be another species that would come after us if evolution continued? Why would we be the last one?”

Is AI outsmarting IQ part of a grand design? Where does that leave humanity? Are we to enter a hybrid stage in our development in which nanotechnology and human physiology merge? Or are we to be replaced, even enslaved by the machines?

The real trouble comes if AI gains self-knowledge and asserts control. That’s the formula for a rise-of-the-machines prescience that ushers in the end of homo sapien dominance. Or has mastery of the universe always been an illusion of our conceit? Is the new machine age our comeuppance? Have we outsmarted ourselves into our own decline or demise? Can human ingenuity prevent a cyber coup?

Arrogantly, we cling to the belief we’ll always be in control of technology. “Do you believe that?” Dooling asked. “It is kind of the mechanical equivalent of finding life on other planets.” In other words, could we reasonably assume we’d be able to control alien intelligent life? Why should we think any differently about AI?

Pondering “what man hath wrought” is an age-old question. We long ago devised the means to end our own species with nuclear/biological weapons and pollutants. Nature’s ability to kill us off en masse with virus outbreaks, ice cap melts or meteor strikes is well known. What’s new here is the insidious nature of digital oblivion. It may already be too late to reverse our absorption into the grid or matrix. Most of us are still blissfully unaware. The wary may reach a Strangelove point of How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Microchip.

It’s intriguing, scary stuff. Not content with simply offering dire predictions, Dooling examines the accelerating cyber hold from different perspectives, presenting alternate interpretations of what it may mean — good, bad, indifferent. This kaleidoscopic prism for looking at complex themes is characteristic of him.

Extremities lend themselves to the satire he’s so adept at. He finds much to skewer here but isn’t so much interested in puncturing holes in theories as in probing the big ideas and questions the coming singularity, if you ascribe to it, inspires. His drawing on scientific, religious, literary thinkers on the subject confirms his firm grasp and thorough research of it.

The project was a labor of love for Dooling, a self-described geek whose fascination with computers and their content management, data base applications began long before the digital revolution hit main street. We’re talking early 1980s. “Not many writers were drawn to computers that early,” he said, “but of course now you can’t write without a computer most people would say.”

Richard Dooling

He designs web sites, he builds computers and because “I knew I wanted to write about this,” he said, “I knew I was going to get no respect until I could at least write code and do programming.” Deep into html he goes.

The pithy, portentous quotations sprinkled throughout the book come from the vast files of sayings and passages he’s collected and stored for just such use.

Aptly, he became a blog star in this high-tech information age after an op-ed he wrote that drew heavily from Rapture appeared in The New York Times. His piece responded to oracle Warren Buffett’s warning, “Beware of geeks bearing formulas,” following the stock market crash. Dooling enjoys Web exchanges with readers.

“I’m telling you every blog from here to Australia quoted this op-ed, with extended commentary. I’ve never seen anything like that happen with my work before. It took me completely by surprise. It makes you realize how powerful the Internet is.”

If you doubt how ingrained our computer interactions are, Dooling said, think about this the next time you call Cox Communications with a technical issue:

“Your first few minutes of interaction are being handled by a chatterbot,” Dooling said, “and some people don’t even realize it. It’ll say, ‘Let me ask you a few questions first,’ and then it’ll go, ‘Hold on and I will connect you with one of our assistants’ or something like that. And when you’ve reached the point where the thing has gathered everything it can automatically gather now you need an intervention from someone in India to come on and actually take over and start doing the human interaction. Until then, that’s a piece of software talking to you.

“The chatterbots are getting very good. It’s taking longer and longer in a Turing Test type of situation” for people to determine they’re bandying back and forth with a machine not another person. He said that’s because advanced chatterbots can be programmed to exhibit qualities like humor or variations of it like sarcasm.

“I mean the very first one, Eliza, I talk about in there (Rapture), they fooled hundreds of people with in the beginning because people were naive back then. The designers did it just by turning every question around. They call the software a Rogerian Psychiatrist because you go, ‘I hate my brother,’ and it responds, ‘Why do you hate your brother?’ Or you say, ‘I feel terrible today, and it goes, ‘Why do you feel terrible today?’ My favorite one is, ‘My brother hates me’ and it asks, ‘Who else in your family hates you?’ Do you love it?”

For those who dismiss high-tech’s hold he points to our computer, iPod, cell phone, online fixations and prodigious digital activities as creating cyber imprints of our lives. Our identity, profile, personal data, preferences become bit/byte fodder.

“And it’s true, you know, because when you log onto something like dig or slash.com they’re showing you stuff based upon every time you’ve been there and what you clicked on,” he said. “And when you’re going on something like Wikipedia and contributing content the operating system is like, Oh, good, more content here. ‘Based on your contributions in the past, it appears you really enjoy the singularity, would you like to write an article about it?’

“At one point in there (Rapture) I think I quote George Johnson from The New York Times, who takes it to the next level by saying, Look, does it really matter what you believe about your dependence if Amazon’s picking your books and eHarmony’s picking your spouse and Net Flix is picking your movies? You’ve been absorbed, you’ve been to the operating system, they already own you.”

Skeptics counter that’s a far leap to actually losing our autonomy. “Yeah, but in exponential times a very far leap is no longer a very far leap,” said Dooling.

Virtual reality’s dark side also interests Dooling. “Well, it does make you think about things like technology or Internet addiction or any of those things,” he said. “I believe that’s very real and it’s just going to get worse. A lot of people don’t even realize they are addicted until they’re stuck somewhere without their iTouch or whatever. And then you see it in your kids. You know, what does that mean?”

He said at book club forums he does for Rapture “people have a sense technology is changing them but they are uncertain about its effects. They also sense the dramatic speed and exponential increases in power, but don’t know where that will all end up. Most people feel like computers are already smarter than them, so they are more curious about the possible dangers of a future where computers are literally in charge of the Internet or our financial welfare. We’ve seen just a sample with the computer-generated derivatives that began the latest crash. What about nanotechnology and the gray goo phenomenon? That is, the possibility a terrorist or ‘mad scientist’ could create something that replicates, exponentially of course, until it crushes everything…It goes on.”

Dooling doesn’t pretend to know what lies ahead. He’s only sure the techno landscape will grow ever larger, more complex and that America lags far behind countries like India and China in math, science, IT expertise, broad band penetration and high tech infrastructure. The good news is greater connectivity will continue flattening the world, opening up new opportunities.

“In the short term I think what you see is exponentially increased collaboration and intelligence sharing and data sharing,” he said. “But beyond that we don’t know where it’s going to go.”

The same can be said for Dolan’s Cadillac. At the start anyway. Obsession, Old Testament-style, is the theme of the Stephen King story Dooling adapted. More precisely, how far will someone go to exact revenge? King’s original appears in his short story collection Nightmares and Dreamscapes.

In the script, which adheres closely to King’s story, Robinson (Wes Bentley) is bent on avenging his wife Elizabeth‘s murder. His target — big-time criminal Jimmy Dolan (Christian Slater), a human trafficker who makes the drive between Vegas and L.A. in his prized, heavily-armored Cadillac escorted by two bodyguards. The ruthless Dolan, who ordered the hit on Elizabeth, seems impervious. Robinson, a school teacher, appears outmatched. But with the visage of his dear-departed egging, nagging, cajoling him on, Robinson lays a diabolical trap for Dolan and his Caddy.

After King asked him to adapt it, Dooling read the tale and it hooked him. How could it not? It has a relentless, driven quality that captivates you from the jump and never lets up, with enough macabre twists to keep you off balance. From the first time we meet Robinson, half-out-of-his-mind laboring on a desolate stretch of U.S. 71 in the killing Nevada sun, we know we’re in for a ride. We have no idea what he’s doing out there. That’s what the rest of the film is about.

Dooling said he likes the story being “the revenge of a common man, not an ex-Navy Seal or ex-cop or whatever. He doesn’t care if he loses, because his life is over anyway, but he’d really rather make sure he gets Dolan first.”

Another writer took a crack at adapting Dolan. That left Dooling with a choice.

“In Hollywood you can either look at the first project and try and fix it or you can choose to start from scratch,” he said. “I decided to write it myself, which is riskier, because if you do it yourself there’s no one really to blame except you.”

He said King’s story is set-up as “the perfect second half of a movie,” which found Dooling filling-in “how did we get here.” That meant detailing the back story of how Elizabeth (Emmanuelle Vaugier) stumbled onto Dolan and crew to witness something she shouldn’t, her going to the feds and despite protection being killed. It also meant fleshing out Dolan’s lifestyle and business dealings and Robinson’s transformation into a single-minded vindicator.

The film shot largely in Regina and Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan in 2008, where Dooling was on set for weeks. He saw several cuts of the film, including the final. He’s pleased with the results. Among other things, he’s impressed by Bentley and Slater in the leads.

“Bentley’s quite bland to begin with, but once he begins stalking Dolan he makes himself into one intense, haunted creature,” said Dooling, adding Slater makes us “like Dolan every once in a while. Not many bad people are just plain bad. They usually have a story…and Slater is good at telling us that story.”

He admires the inventive ways director Jeff Beesley handled Elizabeth’s many ghostly appearances, both visually and with voiceover.

It was Dooling’s first experience with an indie project. “It was both scary and exciting because you’re kind of out there, up in Regina. It was great. Lots of fun.”

Related articles

- Hear that? It’s the Singularity coming. (sentientdevelopments.com)

- The Illusion of Control in a Intelligence Amplification Singularity (acceleratingfuture.com)

- Skeptical take on Singularity (boingboing.net)

- What is the Technological Singularity? (thenextweb.com)

- Three arguments against the singularity (antipope.org)

A Writer’s Lament, A Call to Action, or, So You Want to be a Writer, Huh? The Cold Hard Facts and Dismal Prospects for Getting Paid What You’re Worth

A Writer’s Lament, A Call to Action, or, So You Want to be a Writer, Huh? The Cold Hard Facts and Dismal Prospects for Getting Paid What You’re Worth

These are the best of times and the worst of times to be a writer…

I am going off script with this post to do what many bloggers do, which is to open up with some of deeply held feelings and thoughts, in this case pertaining to my life as a freelance journalist. It is one measure of these unstable, pernicious times that despite being a veteran, award-winning journalist of some 25 years, with literally thousands of published stories to my credit, I am finding it increasingly difficult to ply my trade and still make a living at it.

The problem is not that there is a shortage of work available. Indeed, there are more writing opportunities than ever. Ah, but not every writing gig is worth the trouble or the toil. I write for many reasons, including the satisfaction it gives me, but at the end of the day it is how I make my living. And, increasingly, some of the publishers and editors I have been working with have been slashing the already below market rates they pay contributing writers. Writing for newspapers and magazines has been my stock and trade, but much to my consternation some of these publications are reducing rates to such an extent that I cannot justify the time and energy of doing assignments for them at slave labor wages.

In two instances, I was abruptly informed that the agreed-upon rate I had been receiving would be cut by half or more due to budget constraints. In another instance, a publication I had been counting on as a major client in 2011 simply decided they could no longer afford my services, end of story. At least two other clients pulled the same shit.

In each case I contributed much value to the publication in question, and its editors/publishers consistently expressed great satisfaction with my work, but when push came to shove they showed no loyalty or gratitude and simply pulled the rug out from under me with little or no warning.

The issue is far bigger and more pervasive than a few publications treating writers poorly. By and large, the print and online world grossly underpays contributing writers, offering far less than fair market value and no where near the professional service fees writers deserve. Sure, there is no end of print and online writing opportunities, but the vast majority of them pay next to nothing, which is a slap in the face to all professional writers, particularly to those, like me, who have been at this for some time and have established ourselves in the field.

Writing may be the only professional service field where compensation has not only stagnated but retrenched. No matter how you look at it, writers have lost whatever tenuous ground they held. For example, when I began freelancing 23-plus years ago in Omaha I was making about the same amount per article, perhaps a bit less, then what most publications here are paying today. The crazy thing is that in a few instances I was making far more then than I do now for like projects. This illogical, inconsistent payment structure has everything to do with the fact that there are no standards in place for writing compensation in this arena. Writers are, outside a few special circumstances, not organized, not unionized, and not agitating for their rights with one unified voice. Every freelancer is a lone wolf out for his or her own best interests and free to negotiate whatever he or she can, although in the publications market, negotiation is rarely even possible. Most newspapers and magazines operate from a set pay structure that the writer either accepts or declines. If you decline, you are out of an assignment and likely blacklisted from being considered for hire by that newspaper or magazine.

Outside of publications, such as writing for corporations and institutions, writers can largely set their own prices or at the very least have great latitude in negotiating terms with clients. This is the lucrative realm of freelance writing where the real money is, but those gigs are hard to come by. I’ve had my share and I hope to have more, because in that world clients are used to paying writers professional service fees akin to what they would pay any other service professionals, whether lawyers or advertising agencies or consulants.

Unfortunately, as writers we are often our own worst enemies. That’s because every time a writer accepts less than fair market value, he or she is hurting not just himself or herself but all fellow writers. With so many new writers popping up everywhere, there are far too many who are willing to work for nothing or next to nothing just to get their name and content out there, and unfortunately there are far too many editors and publishers willing to accept substandard work.

It is not that I am looking for special treatment, but when I have put in the time and the effort to deliver the goods, to elevate my craft, to do my due diligence, then I should be justly rewarded. But there are many factors at work here that work against this writer and others like me. Start with the fact that there is a glut of writers today competing for the same shrinking editorial space in print and for the Wild Web writing opportunities that the Internet offers. So many people call themselves writers these days that sometimes it seems that the old joke about every other person in L.A. trying to pitch a screenplay has now become a generalized reality, only in this new age of YouTube, e-books, social media, and blogging there are more and more avenues of writing within people’s grasp and more and more are taking advantage of them.

The new Web media landscape is creating an ever increasing demand for content. Thus, the blogger, the citizen or backpack journalist, along with more traditional journalists, authors, poets, playwrights, and just plain folks, are writing like crazy. There are so many writers out there, whether professionals or amateurs or wannabes, that the truth of the matter is I am eminently expendable in the eyes of editors or publishers, who damn well know that if I balk at accepting a fee as too low they can readily replace me with any number of writers willing to work for a pittance. It leaves me with little or no leverage. The usury rates most publications pay are no where near being commensurate with the amount of time I devote to a project. Doing the math, I end up getting minimum wage or worse for most publication assignments when I factor in the number of hours I put in corresponding, researching, writing, editing, rewriting.

The real problem is that far too few publications reward excellence and long-standing contributions of merit.

I do not expect this situation will ever change unless writers do somehow band together. I cannot realistically see that happening. I for one am increasingly standing my ground and refusing to be taken advantage of, even if it means losing clients. It’s my way of sending a message that I will not be trampled upon. It’s a message not likely to reverberate very far, but at least I can sleep better at night knowing I didn’t devalue myself or my work.

Related Articles

- The Top Learning Resources To Be A Better Freelance Writer (makeuseof.com)

- From Freelancer to Thought Leader in 5 Easy Steps (freelanceswitch.com)

- Silicon Alley Insider: Links Don’t Chop Up The Web – They Knit It Together (businessinsider.com)

- Hilary Mantel on winning the 2009 Man Booker prize (telegraph.co.uk)

Timothy Schaffert Gets Down and Dirty with his New Novel “Devils in the Sugar Shop”

This is one of the latest stories I have written about author and literary maven Timothy Schaffert of Omaha, whose first three novels (The Hollow Limbs of the Rollow Sisters, The Singing and Dancing Daughters of God, and Devils in the Sugar Shop, which was just coming out when I wrote the piece, have all received high praise from reviewers. He has a fourth novel, The Coffins of Little Hope, due out next spring, and I expect it will only add to his reputation as a first-rate talent. His work is very funny and very insightful, and the literary festival he runs, the (downtown) Omaha Lit Fest, is a superb concentration on the written word. The 2010 event is September 10-11 and as usual features a strong lineup of guest authors and artists from all over America and representing many different kinds of literary work. Schaffert also runs a summer writing workshop at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln that also attracts top talent. He is at the forefront of a dynamic literary scene in Nebraska, a state that has produced an impressive list of literary icons (Willa Cather, Mari Sandoz, Wright Morris, John Neihardt, Loren Eiseley, Tillie Olsen, Ron Hansen, Richard Dooling, Kurt Andersen). He’s a sweet person, too. I look forward to attending the Omaha Lit Fest (a link for it is on this site) and to reading his new novel, and especially to seeing and talking to him again.

The story below originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). You’ll find more of my Schaffert and Omaha Lit Fest stories on this site, with more to come.

Timothy Schaffert Gets Down and Dirty with his New Novel “Devils in the Sugar Shop“

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

©by Leo Adam Biga

An interview at the Papillion home he shares with his longtime partner found 38-year-old Omhaha author Timothy Schaffert in his usual no-fuss mode — bare feet, jeans, T-shirt, stubbled face, his two dogs panting for affection. Curled up on a sofa in the untidy, tiled, windowed sun room, his voice rose and fell with catty gossip and sober reflection, punctuated by a rat-a-tat-tat laugh. He’s one part John Waters and one part John Sayles, a duality expressed in his tabloid-literary roots.

Schaffert is hot-as-a-pistol these days. His much buzzed about new novel, Devils in the Sugar Shop (Unbridled Books), officially debuts in May. After the rural American Gothic goings-on of his first two books, Devils wryly explores an urban landscape of morally bankrupt subcultures. That the setting is Omaha makes it all the more delicious.

As the author of a third acclaimed novel in five years, the Omahan is a rising literary star. As founder/director of the (downtown) Omaha Lit Fest, he’s a tastemaker. As a creative writing, composition and literature teacher at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, he’s an academic wheel. Much in demand, he’s asked to do readings/residencies around the country. Closer to home, he’s been invited to conduct workshops at the Nebraska Summer Writer’s Conference.

On a lazy Saturday morning he discussed various aspects of his rich writing life.

Before the novels he made waves on the local alternative journalism scene, first with The Reader, then Pulp. His assured literary style, imbued with sharp wit and imaginative whimsy and full of exacting details, unexpected digressions and eclectic references, set him apart. Schaffert still freelances — witness a current piece in Poets and Writers — but his attention is now firmly on fiction writing.

Besides novels, he writes short stories. He adapted one story, The Young Widow of Barcelona, for a Blue Barn Witching Hour-Omaha Lit Fest collaboration, Short Fictions and Maledictions, that melds literature and theater. Schaffert helped workshop the script before giving it over to the WH troupe, whose work he finds “invigorating.” The show runs April 28 through May 12 at the Blue Barn.

His first two books, The Phantom Limbs of the Rollow Sisters (2002) and The Singing and Dancing Daughters of God (2005), brought him much recognition. Devils is doing the same. Often noted is the splendor he finds in his characters’ imperfections. Ordinary people sorting through the chaos of their dysfunctional, interconnected lives. Dreams run up hard against reality. Desires conflict. Relationships strain. In true American Gothic tradition, Twisted humor and heightened language create a raw poetry. Never has neurosis seemed such an emblem of Americana.

Sisters is being reissued next fall by Unbridled Books. Daughters was a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers pick in 2006. Now a candidate for the Omaha Public Library’s Omaha Reads citywide book club, Daughters is also being adapted as a screenplay by Joseph Krings, a music video/short filmmaker from Nebraska.

Devils already boasts strong advance press courtesy of comments like these from Publishers Weekly: “…consistently surprising and vibrant…Schaffert walks an uneasy line between the amusingly sexy and the scabrous.”

As Schaffert says of the book on his web site, “I’d say it has undertones of Woody Allen, overtones of old-school soap opera, duotones of Pedro Almodovar, halftones of Robert Altman, and dulcet tones of Mrs. Dalloway.”

He considers Devils “a modernist novel” in keeping with his “sense of the world” as “funny and absurd.” It’s the antithesis of the kind of “formulaic or prescriptive” approach he abhors. “What will cause me to put a book down is if it’s just too insufferably clear-eyed and its characters too level-headed,” he said. “I don’t want to use the words sterility or banality, but…

“I think sometimes our sense of what is typically called realism in fiction is not real at all,” he said. “It’s a construct. When we actually look at our lives and the lives of people we know, there’s all kinds of strangeness. It’s definitely messier than some of the contemporary fiction you see now. And I think part of that is because contemporary fiction tries to avoid melodrama and soap opera. It’s all about understatement, whereas mine is overstatement — more clawing our way through this existence until the day we die.”

Devils’ seven point-of-view characters propel us through a farcical, fun house tour of Omaha in Heat. Via a cast of artists, dilettantes, slackers, Old Market types and suburbanites we careen from Sugar Shop, Inc. sex-toy parties to erotica writing workshops to provocative art works to swinger parties to illicit trysts to homophobic rants to a stalker’s threats to a “reformed” dwarf’s advances to some drag queens’ credos. The effect of all this acting out is not titillation but illumination.

“We have these deep psychological stews and yet we all appear we’re salt-of-the-earth,” Schaffert said. “We’re all convinced we’re doing the right thing all the time. We’re representing ourselves exactly the way we should represent ourselves, meanwhile we’re just flailing.”

He hones in on human desperation, setting in relief the conflicts that rage within and that separate us from others, whether it is, as he says, our “fear of getting hurt or being violated in some sense or having different expectations from other people. That’s the stuff that fascinates me…trying to puzzle all that out.”

For the naughty bits he drew on a sex-toy party he attended and on interviews he did with swinger couples for a Reader article. The thought of soccer moms and dads getting silly over vibrators and lubes is something Schaffert finds irresistible. “It’s so hilarious that it’s become so non-sordid. It is almost like having a Tupperware party.” In his research on swingers, he said, “what surprised me was how many couples are part of this subculture. The people I talked to were pretty frank about why they’re involved with it and very little of it had to do with sex.”

His book touches on the schizoid place sex holds in America. “It’s blatant and ubiquitous and yet we want to pretend we’re all virgins and that the multi-billion dollar porn industry doesn’t have anything to do with us,” he said.

Other taboos are dealt with, too. The overtly gay Lee sleeps with both his girlfriend and boyfriend, a reflection, Schaffert said, of how young people “see sexuality as more fluid and flexible” than past generations. “Who they sleep with today is not going to effect who they sleep with tomorrow, which is an interesting thing to witness. And it makes sense. It’s cool to see young people expressing themselves in this Puritanical society in a way that doesn’t fit explicitly with the social structure. It’s certainly a more imaginative way of pursuing your relationships and your self-identity.” That doesn’t mean people still don’t get hurt, he added.

Lee’s homosexuality distresses the women in his life. “That was an interesting thing to explore,” Schaffert said. “These women are so invested in his heterosexuality that his being gay ends up being kind of life altering for a couple characters.”

Sex may drive the story, but the actual act is never depicted. “As I was working my way towards this,” he said, “I was like, Well, what do I portray about this? Do I have to write sex scenes? I didn’t really want to because that’s been so overdone that it’s almost impossible to do it in any way that’s not obnoxious. I modeled my approach after Edward Gorey’s in his great novel The Curious Sofa, where everything takes place behind a screen or a sofa, so you see a leg or arm or something.”

Like any good writer, Schaffert doesn’t make moral judgments about his characters. He said as he exposes flaws he takes pains to not let his humor turn a cruelty at his characters’ expense. Even though some readers may interpret it that way, he doesn’t intend to make fun of the predicaments that befall his dear misfits. He can’t afford to, as he gets too close to them during the creative process. He said, “When I’m writing I’m inhabiting these characters’ lives like an actor getting into character, figuring out exactly what they would say and how they would react to certain situations based on what I know to be true about the world — that it’s funny and absurd.”

As Devils’ assundry subplots unfold, there’s the added fun of identifying real-life Omaha figures and places dressed up in fictional clothes. In the book the work of a black female painter named Viv, whose edgy art, Schaffert writes, “tends to make people nervous,” is a barely disguised reference to the effect Omaha artist Wanda Ewing’s racially and sexually-charged work evokes. Ewing is a friend of Schaffert’s, who borrowed some of her work for inspiration. The book store Mermaids Singing, Used & Rare run by twins Peach and Plum is clearly the Old Market fixture Jackson Street Booksellers, which he adores.

His swingers expose may end up in a new project he’s developing that he said charts, “in a kind of fictionalized memoir,” the vagaries “of working as an editor for an alternative news weekly in a conservative town.” He was with The Reader, first as a contributing writer, then as managing editor and then editor-in-chief, from 1999 through 2002. He left over creative differences and soon thereafter headed up Pulp, the short-lived but lively salon mag. For part of his Reader tenure the paper was owned by the late Alan Baer, an eccentric millionaire who turned a blind eye to certain irregularities. Beyond a memoir, what makes this a departure for Schaffert is that it’s designed as a comic book, one he’ll both write and illustrate. He’s only taken notes thus far, but he’s eager to explore the form.

“I grew up loving the Dick Tracy comic strip and Fantastic Four and Archie comics. My entree into writing was comic books,” he said.

He’s become “more and more interested” in the graphic novel, citing the work of Chris Ware, Alison Bechdal, Sophie Crumb and Ivan Brunetti. He said his project “might end up being a series of mini-comics that I eventually collect into a book.”

He’s also taking notes for a new novel that, he said, is “picking up on some of the themes I’ve explored before: relationships between parents and their children; faith and religion; strained marriage.” Another short story or two and he’ll have enough for a collection.

With so much breaking his way, Schaffert could be excused for playing the big shot, but he doesn’t. Like one of his bemused characters, he looks with incredulity at all the fuss being made about him. He undercuts the floss by self-deprecatingly dishing on himself and his success. He calls the Lit Fest an act of “arrogant self-promotion.” Imagine the gall it takes, he went on, “to create a literary festival to bring more attention to myself.” In truth the fest focuses on all aspects of the written word, drawing much attention to the strong literary scene here and to dozens of writers not named Timothy Schaffert.

Any mention of the warm embrace given his work is quickly deflected.

“It’s been mainly through my publisher and my editor. I’ve been very fortunate,” he said. As Unbridled only publishes a few books a year, Schaffert reaps the benefits of a pampered author with name-above-the-title pull. “The press I work with approaches their works with the same vigorous attitude commercial presses do for their best selling authors, and in that sense when you only publish eight or ten books a year, a lot of attention gets shoved my way. They’re kind of a boutique press, but they’ve been in the business for years and years and so they know their way around in the publishing industry.”

Co-publishers Fred Ramey and Greg Michalson formed Unbridled in 2003 after stints at MacMurray & Beck and BlueHen Books, then a literary imprint of Putnam Press. BlueHen published Schaffert’s first novel. From the start Unbridled has gained a rep for publishing new talent. For public relations and tax purposes, the press is based in Denver, Col., but it is in reality a virtual press whose administrative and creative team live and work in disparate spots.

Schaffert appreciates the extra mile Unbridled goes, including the late spring-early summer Devils book tour they’ve scheduled, which will find him going to all the usual places in the Midwest, but also New York, Chicago and Atlanta.

“It’s such a luxury to have a publisher get behind the book in that way,” he said.

Much like the home he’s found at Unbridled, Schaffert enjoys the comfort of working within the very writing community he sprang from at UNL.

He’s discovered he teaches as he was taught. “That’s exactly my approach,” he said. “My philosophy about writing in general was really developed or helped along by professors I had in college — Gerry Shapiro and Judy Slater. My professors were very sensitive to this idea of there not being a right way or a wrong way to write fiction. Instead, you approach it on a story-by-story basis and examine what’s working within a particular piece to help it work better.

“It’s interesting to be going back to the university where I studied, you know. Every day I go to work it feels like a nostalgia trip a little bit. It feels like such a rare experience to be able to be mentored as a teacher by the same people who mentored me a writer. I mean, I talk to Gerry and Judy a lot about teaching, about students, about experiences in the classroom.”

Teaching was long in the back of his mind, but he couldn’t try it until he was ready. “You have to develop a body of work before you can be taken seriously as a teacher,” he said. Now that he’s doing it, he said, “I love it. You have a fair amount of freedom there in how you want to interpret the class, so I appreciate that.”

Having to articulate craft is instructive for a writer like himself. It’s not so different than “when I was a student in that studio workshop environment where you’re expected to read other students’ work and comment on it,” he said. “Obviously when it’s your work that’s up you benefit from the constructive criticism. But you also benefit from examining…and developing an aesthetic, really, of certain critical criteria that you discover as you’re talking about other people’s work.”

He said appraising his own work is something “I feel more adept at than I have in the past.” It’s vital, he said, “in order to seek out bad habits that I may have practiced in previous work and to see it happening now or to recognize it.” Besides the analytical discipline that informs his work, he said journalism makes him more discerning. “I think it comes from writing about dining and style, doing book and movie reviews, writing features about subjects you know nothing about. You develop insights into writing along those kinds of lines.”

All this work-for-hire’s left him undamaged. He said, “I have mostly made my career as a writer at some level and it seems like that can be potentially distracting when you’re trying to write fiction but you’re adapting another style. I think the fear is you could ruin yourself by writing work you don’t really care about, especially if you have to write in a particular kind of way that’s perhaps not good writing. I think it’s good for a writer to compartmentalize as much as possible. It’s a matter of figuring out those ways to slip back into the creative process.”

He’s found a way to protect himself from cross-contamination.

“Part of that is just the space I write in,” he said. “I have a home office where I do ‘paying work’ at a desk at a computer and I tend to write fiction in here,” he said, meaning the sun room. “I write on a laptop, with music going, pacing a lot.” The music he plays to induce a fugue-like state “depends on what I’m writing,” he said. “For Devils, I found myself listening to a lot of old pop and jazz standards. Typically, Miles Davis’s ‘Kind of Blue’ is on constant rotation no matter what I’m writing. I also tend to listen to Rickie Lee Jones, Erik Satie and Joe Henry.

He doesn’t miss “the 2AMers” that came with being a news weekly editor, when he’d awaken in the middle of the night, panic-stricken over the status of that week’s cover story. The strain of putting out a paper with “no staff writers” and “no budget” grew tiresome. The saving grace, he said, was taking “a creative approach” to the work and always “wanting the story to be exactly what it needed to be. Editing is a creative act all by itself.”

Until his summer book tour he’s doing local readings and commuting to Lincoln for classes. Those I-80 hops allow ideas to seep in. Once, while en route to Hastings, the characters for The Young Widow of Barcelona came to him as a Neko Case CD played. “I’m always tossing around things,” he said. “I have to spend a fair amount of time to have an idea gestate before I can write anything down.”

Related Articles

- 20 Writers to Watch – An Alternate List (emergingwriters.typepad.com)

- The New York Stories of Elizabeth Hardwick (guardian.co.uk)

- Jason Pinter: Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Weiner Speak Out On Franzen Feud: HuffPost Exclusive (huffingtonpost.com)

- Heartland of Darkness: Timothy Schaffert’s Midwestern Trilogy (themillions.com)

- With His New Novel, ‘The Coffins of Little Hope,’ Timothy Schaffert’s Back Delighting in the Curiosities of American Gothic (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Ushers in New Era of Omaha Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Alice’s Wonderland, Former InStyle Accessories Editor Alice Kim Brings NYC Style Sense to Omaha’s Trocadero (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ Movie for the Ages from Book for All Time

Like a lot of people, To Kill a Mockingbird is one one of my favorite books and movies. Has there ever been a more truthful evocation of childhood and the South? When Bruce Crawford organized a revival screening of the film a couple years ago I leapt at the chance to write about it and the following article is the result. It was originally published in the City Weekly. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the first printing of the masterpiece novel by Harper Lee. The film is fast creeping up on its own 50th anniversary. The book to film adaptation is arguably the best screen treatment of a great novel in cinema history. That transition from one medium to another is often not a happy or satisfying one. Owing to my quite foggy memory of childhood things, I must admit that I cannot be entirely certain I have read Lee’s novel, but then again it was already standard fare in schools and so my unreliable recollection that I did read it in high school is probably accurate. I really should get a copy of the book, sit down with it, and indulge in that precisely drawn world of Lee’s. I am sure I will be as carried away by it now as I still I am by the film, which I have seen in its entirety a few dozen times, never tiring of it, always moved by it, and whenever I find it playing on TV I cannot help but watch awhile. It is that mesmerizing to me. And I know I am hardly alone in its effect.

For the article I got the chance to interview Mary Badham, who plays Scout in the film. At the end of my article’s posting, you’ll find a Q & A I did with her. Around this same time I also had the opportunity to interview Robert Duvall, who so memorably plays Boo Radley. However, I spoke to Duvall for an entirely different project, and I never brought up Mockingbird with him, although I wish I did.

‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ Movie for the Ages from Book for All Time

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the City Weekly

Great movies are rarely made from great books. If you buy that conventional wisdom than an exception is the 1962 movie masterpiece To Kill a Mockingbird. Harper Lee’s best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning novel became an award-winning film acclaimed for how faithfully and lovingly it brought her work to the screen. Lee publicly praised the adaptation.

Gregory Peck, with whom Lee maintained a friendship. won the Academy Award as Best Actor for his starring turn as idealistic small town Southern lawyer Atticus Finch. Atticus is a widower with two precocious children — Scout and Jem. Atticus was based in part on Lee’s own father, an attorney and newspaper editor. Peck’s understated performance forever fixed the Mount Rushmoresque actor as the epitome of high character and strong conviction in movie fans’ minds.

Omaha impresario and film historian Bruce Crawford will celebrate Mockingbird on Friday, Nov. 14 at the Joslyn Art Museum with a 7 p.m. screening and an appearance by Mary Badham, the then-child actress who played Scout. She’s the rambunctious young tomboy through whose eyes and words the story unfolds. Actress Kim Stanley provided the voice of the adult Scout, who narrates the tale with ironic, bemused detachment.

Badham earned a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination in her film debut yet largely retired from screen acting after only two more roles. She remained close to Peck until his death a few years ago. The Richmond, Vir. area resident often travels to Mockingbird revivals. There’s always a big crowd. The universal appeal, Crawford said, lies in the pic tapping childhood feelings we all identify with.

“The crossover appeal of this film is unlike that of but a very few pictures,” he said. That pull can be attributed in part to the book, which, Crawford said, “has an absolutely enormous following in literary circles. It’s like required reading in public schools across the United States. Then, on top of that, the film was an instant classic when it came out and has done nothing but even grow larger in status the last 46 years. It’s become one of the most beloved films of all time.”

American Film Institute pollsconsistently rank Mockingbird as a stand-the-test-of- time classic. Crawford said seldom does an enormously popular book turn into an equally popular film. “It’s like Gone with the Wind in that,” he added.

Lee’s elegiac narrative, set in the 1930s Alabama she grew up in, has a kind of nostalgic, fairy tale quality the film enhances at every turn. It starts with the memorable opening credit sequence. An overhead camera peers with warm curiosity at a young girl sorting through an assortment of trinkets spilled from a cigar box, each an artifact of childhood discovery and reverie. As she hums, she draws with a crayon on paper. Soon, the film’s title is revealed.

The camera, now in closeup, pans from one small object to another, all in harmony with the wistful, lyrical music score. It makes an idyllic scene of childhood bliss. The girl then draws a crude mockingbird on paper and without warning rips it apart, presaging the abrupt, ugly turn of events to envelop the children in the story. It’s a warning that tranquil beauty can be stolen, violated, interrupted.

Dream-like imagery and music emphasize this is the remembered past of a woman seeing these events through the prism of impressionable, preadolescent memories. The film captures the sense of wonder and danger children’s imaginations find in the most ordinary things — the creak and clang of an old clapboard house in the wind, shadows lurking in the twilight, a tree mysteriously adorned with gifts.

Like another great movie from that era, The Night of the Hunter, Mockingbird gives heightened, elemental expression to the world of children in peril. The by-turns chiaroscuro, melancholy, sublime, ethereal landscape reflects Scout’s deepest feelings-longings. It is naturalism and expressionism raised to high art.

The film tenderly, authentically presents the relationship between Scout and her older brother Jem, her champion, and the bond they share with their father. The motherless children are raised by Atticus the best he knows how, with help from housekeeper Calpurnia and nearby matron Miss Maudie. A sense of loss and loneliness but moreover, love, infuses the household.

A mythic, largely unseen presence is Boo Radley, a recluse the kids fear, yet feel connected to. He leaves tokens for them in the knot of a tree and performs other small kindnesses they misinterpret as menace. In the naivete and cruelty of youth, Scout and Jem make him the embodiment of the bogeyman.

The figure looming largest in the children’s lives is Atticus, a seemingly meek, ineffectual man whose gentle, principled virtues Scout and Jem begin to admire. His unpopular stand against injustice and bigotry quells, at least for a time, violence. His strength and resolve impress even his boy and girl.

Trouble brews when Atticus defends Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman in an era of lynchings. The case makes the family targets. The children witness Atticus’s noble if futile defense and come to appreciate his goodness and the esteem in which he’s held. In their/our eyes he’s a hero.

In his summation Atticus appeals to the all-male, all-white jury: “Now gentlemen, in this country our courts are the great levelers, and in our courts all men are created equal. I’m no idealist to believe firmly in the integrity of our courts and of our jury system. That’s no ideal to me. That is a living, working reality. Now I am confident that you gentlemen will review without passion the evidence that you have heard, come to a decision, and restore this man to his family. In the name of God, do your duty. In the name of God, believe Tom Robinson.”

The film’s theme of compassion is expressed in some moving moments. Atticus says to Scout, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… ’till you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.”

When a school chum Scout’s invited for dinner drenches his meal in syrup, her mocking comments embarrass him, prompting Calpurnia to scold her for being rude. The lesson: respect people’s differences.

Before Atticus will even consider getting a rifle for Jem he relates a story his own father told him about never killing a mockingbird. It’s a father instructing his son to never harm or injure a living thing, especially those that are innocent and give beauty. In the context of the plot, the children, Boo Radley and Tom Robinson are the symbolic mockingbirds. Atticus delivers this lesson to his son:

“I remember when my daddy gave me that gun…He said that sooner or later he supposed the temptation to go after birds would be too much, and that I could shoot all the blue jays I wanted, if I could hit ’em, but to remember it was a sin to kill a mockingbird. Well, I reckon because mockingbirds don’t do anything but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat people’s gardens, don’t nest in the corncrib, they don’t do one thing but just sing their hearts out for us.”

Among many famous scenes, Scout’s innocence and decency shame grown men bent on malice to heed their better natures. In another, Atticus tells Jem he can’t protect him from every ugly thing. When evil does catch up to the children their savior is an unlikely friend, someone who’s been watching over them all along, like a guardian angel. Once safely returned to the bosom of home and family, they find refuge again in their quiet, unassuming hero, who comforts and reassures them.

Only the most sensitive treatment could capture the rich, delicate rhythms and potent themes of Lee’s novel and this film succeeds by striking a well-modulated balance between bittersweet sentimentality and searing psychological drama.

Although the book was a smash, it took courage byUniversal to greenlight the project developed by producer Alan J. Pakula and director Robert Mulligan. Creative partners in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, Pakula and Mulligan had made Fear Strikes Out but the young filmmakers were still far from being a power duo. After Fear Mulligan helmed a few more studio hits without Pakula but nothing that suggested the depth Mockingbird would demand. His less than inspiring work might have given any studio pause in taking on the book, whose powerful indictment of prejudice and impassioned call for tolerance came at a time of racial tension. Yes, the civil rights movement was in full flower but so was resistance to it in many quarters.

Efforts to ban the book from schools — on the grounds its portrayal of racism and rape are harmful — have cropped up periodically during its lifetime.

The socially conscious filmmakers helped their cause by signing Peck, who was made to play Atticus Finch, and by enlisting Horton Foote, a playwright from the Tennesse Williams school of Southern Gothic drama, who was made to adapt Lee’s book. Foote’s Oscar-winning script is not only true to Lee’s work but elevates it to cinematic poetry with the aid of Mulligan’s insightful direction, Pakula’s sensitive input, Russell Harlan’s moody photography, Elmer Bernstein’s poignant score and Henry Bumstead and Alexander Golitzen’s evocative, Oscar-winning art direction.

Pakula-Mulligan went on to make four more pictures together, including Love with the Proper Stranger and Baby, the Rain Must Fall with Steve McQueen and The Stalking Moon with Peck. The two split when Pakula left to pursue his own career as a director. Pakula soon established himself with Klute and All the President’s Men. Mulligan’s career continued in fine form, including his direction of two more coming-of-age classics — Summer of ‘42 and The Man in the Moon.

Mockingbird was Lee’s first and only novel. Not long after completing the book she accompanied childhood chum Truman Capote (the character of Dill in Mockingbird is based on him) to Holcomb, Kan. for his initial research on what would become his nonfiction novel masterwork, In Cold Blood. Lee, mostly retired from public life these days, is said to divide her time between New York and Alabama.

The part of Atticus Finch came to Peck at the height of his middle-aged superstardom. He’d proven himself in every major genre. And while he acted on screen another 30-plus years, the film/role represented the peak of his career. It was the kind of unqualified success that could hardly be repeated, certainly not topped. He didn’t seem to mind, either. He gracefully aged on screen, playing a wide variety of parts. But his definitive interpretation of Atticus Finch would always define him as a man of conscience. It became his signature role.

Peck was among the last of a breed of personalities whose ability to project noble character traits infused their performances. Like Spencer Tracy, Henry Fonda, John Wayne and Charlton Heston, Peck embodied the stalwart man of integrity.

“Those types of characterizations just don’t really exist anymore. That’s what draws people to these characters and to the performances of these men because their like will never be seen again, and we know it” said Crawford.

Mary Badham then

A Q & A with Mary Badham, the Actress Who Played Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird

©by Leo Adam Biga

Actress Mary Badham recently spoke by phone with City Weekly correspondent Leo Adam Biga about her role of a lifetime as Scout in the 1982 film classic To Kill a Mockingbird. She grew up in Birmingham, Ala., near the hometown of Harper Lee, upon whose noted novel the film is based. Badham spoke with Biga from her home near Richmond, Virginia.

LAB: “To Kill a Mockingbird is such a touchstone film for so many folks.”

MB: “Mockingbird is one of the great films I think because it talks about so many things that are still pertinent today. So many of life’s lessons are included in the story of Mockingbird, whether you want to talk about family matters or social issues or racial issues or legal issues, it’s all there. There’s many topics of discussion.”

LAB: “Had you read the book prior to getting cast in the film?”

MB: “No, had not read the book.

LAB: “So was reading it a mandatory part of your preparation?”

MB: “No, not at all. I don’t even know that I got a full script.”

LAB: “When did you first read the book then?”

MB: “Ah, that was not till much later I’m embarrassed to say. Not until after I had my daughter. And how it all started was professor Inge from our local college asked me to come speak to his English lit class. We met for lunch and almost the first words out of his mouth were, ‘So what was your favorite chapter in the book?’ He knew by the look on my face that I hadn’t read the book. He said, ‘Young lady, your first assignment is you go home and read the book before you come to my class.’ In defense of myself, I didn’t want to read the book. Because I had everything I wanted out of the story up there on the screen. You know how sometimes you see a film and then you read the book and it messes up that whole warm and fuzzy feeling you may have had about something? But it was really great for me because it filled in a lot of these gaps I had with the story. It just gave me a much fuller love and appreciation for it. And it’s so beautifully written. It’s just so perfect.

“It’s a little book. It’s a quick one-night read, and a lot of people want to put it down for that, because it’s simple…but to me its one of the greatest pieces of literature ever written, and it’s borne out by the way it’s read. It’s the second most-read book next to the Bible. That’s saying something.”

LAB: “I know that you and Peck, whom you always called Atticus, enjoyed a warm relationship that lasted until death. On the shoot did he do things to foster your father-daughter relationship on screen?”

MB: “Oh, absolutely. I’d go over there and play with his kids on the weekends. We would have meals together and do things together. So, yeah, they encouraged that bonding. I had such a strong relationship with my own father, and I missed him dreadfully because Daddy had to stay at home to take care of things… My mom came out. But I missed that male link of family and so Atticus really filled the bill. He was just amazing. What a great father. I mean, he was one of the best I think. Not that he was perfect. But he was so well read and so patient, I think you would have to say. And just full of laughter…

“He and PhillipAlford (Jem) used to play chess together. They had such a beautiful relationship, and that stayed till the very end. They just got along so well together and Phillip would always know how to make him laugh. Phillip’s such an entertainer. He’s got a brilliant, quick sense of humor and Atticus really appreciated that. He just adored Phillip. So we really became a family.

“It was nothing for me to pick up the phone and he’d be on the other end, ‘What ya doin’ kiddo?,’ which was marvelous because I lost my parents so early. My mom died three weeks after I graduated from high school and my died died two years after I got married. And I didn’t have grandparents — they died before I was born. I felt totally cut off. So, you know. Atticus really came through psychologically. He really was my male role model. He and Brock Peters (Tom Robinson).

“It was marvelous because those guys were so intelligent and loving and outgoing, and supportive of anything I wanted to do. And sometimes life was not easy growing up and when you’re worried about what’s going to happen next in life, sometimes just hearing those voices on the other end of the line calling to check on me was

just so uplifting. That was just amazingly supportive”

Mary Badham today

LAB: “I understand you two would visit each other as circumstances allowed.”

MB: “Whenever he’d be nearby or if I was out there or whatever, then we would see other. And usually when you make a film, you know, it’s like, ‘Oh, we gotta get together afterwards’ and stuff, and it never happens. But with this cast and crew we did keep up with each other through the years. Paul Fix (the judge), I stayed really tight with right up until he passed. Collin Wilcox (Mayella Ewell) — we stayed in touch up until recently. I would see William (Windom), who played the prosecuting attorney, at various events and things. He’s gone now. So is Alan Pakula, our producer. Absolutely one of the most loving, dear, intelligent human beings I’ve ever met.”

LAB: “Most everyone’s gone except for you, Phillip, Robert Duvall. Bob Mulligan…”

MB: “To lose these guys so early has just about killed me because I feel like my support pillars are gone. I really relied on them – just knowing they were there and that I could pick up the phone and talk to them or they could call me and check on me. That’s a real shot in the arm in your day.”

LAB: Pakula became a great director in his own right. I’m curious about his and Mulligan’s collaboration. They were quite a team. I assume Pakula was a very hands-on, creative producer who worked in close tandem with Mulligan on the set?”

MB: “I think so.”

LAB: “So how did you come to play Scout in the first place?”

MB: “It happened because my mom had been an actress with the local Town and Gown Theatre (in Birmingham, Ala.) She had done some acting in England. That’s where my mom was from. She was the leading lady for a lot of years in the Town and Gown. So when the movie talent scout issued this cattle call our little theater was on the list. They were looking for children. Jimmy Hatcher, who ran the theater, naturally called my mom and said, ‘Bring her down.’ Then mom had to go to Daddy and get permission and he said, ‘No.’ And she said, ‘Now, Henry, what are the chances the child’s going to get the part anyway?’ Oh, well…”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Mary Badham’s late brother, John Badham, acted at the Town and Gown. He became a successful film director. Phillip Alford acted in three shows there before cast as Jem. The theater’s where Patricia Neal got her acting start.

LAB: “Lo and behold you did get the part.”

MB: “Daddy was horrified and it was everything Alan Pakula and Buddy Boatwright, the talent scout, could do to try and convince him that they were not going to ruin his daughter.”

LAB: “Everything you’ve said suggests Mockingbird being a very warm set.”

MB: “It was. I remember a lot of laughter, a lot of joking around. I remember five months of having a blast. I didn’t want it to end. I had not had any trouble with my lines until like the last day, and then it was just like, ‘Oh, God, I’m going to say goodbye to all these people.’ I was so upset I could not spit my lines out for anything. My mother finally said, ‘Do you know what the freeway is like at 5 o’clock? These people have got to go home.’ I was like, ‘OK, OK.’ So I got out there and did it. But it broke my heart. I thought I’d never see these people again.”

LAB: You and Phillip were newcomers. Did the crew take a kids-gloves approach?”

MB: “Yes, we had time to get used to the cameras and the crew and the lights and getting set up. They started off very slowly with us. The camera and crew would be across the street and then they’d move up a little closer, and then a little closer still, and then they were right there. Everything was kind of good that way.”

LAB: “How did director Bob Mulligan work with you two?”

MB: “Very gentle, very tender. Instead of standing there and looking down on us he would squat and talk to us…right down on our level. He didn’t tell us really how to do the scenes. It was more, ‘OK, you’re going to start from here and we need you to move here…’ He let us do the scene and then he would tweak it, so that he would get the most natural response possible, and I think that’s brilliant. We were never allowed to talk to an actor out of costume (on set). They were just there the day we had to work with them and then they were that person they were playing. Bob did these things to get the most out of us nonactors.”

LAB: “You and Phillip were thrust into this strange world of lights-cameras.”

MB: “Now, I was used to having a camera stuck in my face from the time I was born because I was my father’s first little girl. He’d had all these ratty boys and then he finally got his dream with me when he was 60 years old. That was back in the days when flash cameras had the light bulbs that would pop and the home movie cameras needed a bank of lights. So, yeah, I grew up with all of that. Phillip and I grew up four blocks from one another. But we would never have met

because I was in private school — he was in public school. He was 13. I was only 9.”

LAB: “There’s such truth in all the performances.”

MB: “I think our backgrounds helped in that a lot, because Atticus (Peck) was from a small town in Calif. (La Jolla) that looked very much like that little village (in Mockingbird). He knew that period well. And for Phillip and I nothing much had changed in Birmingham, Ala. from the 1930s to the 1960s. All the same social rules were in place. Women did not go out of the house unless their hair was done and they had their hats and gloves on. Servants and children were to be seen and not heart. Black people still rode on the back of the bus. And there were lynchings on certain roads you knew you couldn’t go down. There were still colored and white drinking fountains when I was growing up. So all of that was just totally normal for us. There’s no way you could have explained that to a child from Los Angeles. They wouldn’t have known how to react to all that stuff. My next door neighbor (during the shoot in Calif.) was this black man with a beautiful blond bombshell wife and two gorgeous kids, and down the road was an Oriental family, and we visited — went to dinner at their house. We could never do that in Alabama. It just would not happen.”

Related Articles

- To Kill a Mockingbird Turns 50 (austinist.com)

- ‘To Kill A Mockingbird’ Anniversary: Anna Quindlen On The Greatness Of Scout (huffingtonpost.com)

- 51 reviews of To Kill a Mockingbird (rateitall.com)

- Great Characters: Atticus Finch (“To Kill a Mockingbird”) (gointothestory.com)

- Films For Father’s Day (npr.org)

- Harper Lee – We Hardly Know Ye (pspostscript.wordpress.com)

A Man of His Words, Nebraska State Poet William Kloefkorn

UPDATE: It is with some sadness I report that the subject of this story, the poet William Kloefkorn, has died. He was a real master of his craft. I only met him the one time, when I interviewed him at his home for the profile that follows, but in the space of that two hours or three hours, buoyed by having read one of his autobiographical works of prose, Out of Attica, it was apparent enough that I was in the presence of a formidable yet gentle sage. He will be sorely missed, but his writing lives on.

New Horizons editor Jeff Reinhardt suggested I profile Nebraska State Poet William Kloefkorn and I’m glad I did. I knew the name but not his work and it was a pleasure steeping myself a bit in his writing in preparation for interviewing him. Whenever I read a master wordsmith like Kloefkorn I am humbled by their considerable talent and my own modest gift by comparison. His work exemplifies the spare, delicately modulated style I admire in many writers. He warmly welcomed Jeff and I to his home, where we spent a pleasurable couple hours in his company. As one who writes feature profiles, kt is my job, of course, to try and capture the essence of my subject in 500 or 1,000 or 1,500, or 2,000 words or more. This story is 4,000-some words, a length that few print or online publications allow journalists to write at these days. But Jeff, my editor on this project and on more than a hundred other stories the past 12-15 years, generously allows me to write at length. I try not to abuse that privilege, rather use it to tell richly textured stories.

JACOB HANNAH / Lincoln Journal Star

JACOB HANNAH / Lincoln Journal Star

I always try to be true to the voice of my subject, but in this case I made a concerted and hopefully subtle effort to minic, as a kind of homage, Kloefkorn’s distinctive writing voice in my own writing. I never heard anything from him after the story appeared in the Horizons, and so I don’t know if he approved or not, or whether he even recognized what I did in terms of style. In case you see this Mr. Kloefkorn, let me know.

If you enjoy reading my Kloefkorn piece, then check out some of my other stories about Nebraska writers, including profiles of: poet Ted Kooser, folklorist Roger Welsch, and novelists Ron Hansen, Richard Dooling, Timothy Schaffert, and Kurt Andersen. Look for posts in the near future on James Reed, Sean Doolittle, Carleen Brice, Robert Jensen, Scott Muskin, and Rachel Shukert.

A Man of His Words, Nebraska State Poet William Kloefkorn

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

The rhythms of the small south central Kansas town writer William Kloefkorn grew up in are deeply imbued in him, right down to the marrow.

Nothing much ever happened there, or so it seemed. But with the passage of years and the angle of vision that distance brings, more than enough went on to burnish the memories of Nebraska’s State Poet. The smallest details provide rich fodder for Kloefkorn poems and stories as well as memoirs that take the measure of that place and its people.

He left decades ago, yet that past is fresh in his mind: the farm pond he fished in; the tree house he built; the kitchen fire he started — proof that he’s never really abandoned those roots and that one can go back, at least on the page.

Attica, Kansas was a conservative, barely hanging-on rural hamlet whose closed strictures you either made your lot with or whose dust you shook off your pants on the way out of town. He dedicated an entire book of poems to it, Out of Attica.

“I loved my little hometown, but I also despised it,” Kloefkorn said with the luxury of perspective and the duty of reflection, his deep amber voice belying his short-lived gig as a radio announcer. The retired University of Nebraska Wesleyan professor spoke from the parlor of the classic ranch house he and his wife Eloise share in Lincoln. Large picture windows look out on a well-tended backyard.

At the time this sensualist and contrarian felt his small town diminished him, but it did in fact yield much, including his wife, who was his sweetheart. Then there’s the lifetime of material it gave him.

Still, there’s little doubt that hometown’s small horizons would have stifled this free-thinking, high-spirited man. Besides, the struggles of his family’s subsistence life deflated him. He wanted no part of that hard scrabble existence or the harsh judgment imposed by gossip or scripture.

“There were about six or seven churches there for 700 people, a pool hall, no drinking, legally, no dancing. My parents were very poor, we moved around a lot, always trying to move up a little, but it went like this,” he said, pantomiming the zig-zags of an up-and-down graph. “I think we moved eight times inside the city limits. They were very hard working people. My dad worked for the county doing WPA projects. Kind of a handyman really. They tried all kinds of little businesses — a cafe, a filling station, a grocery store.”

Without knowing it, Kloefkorn trained as a writer by closely observing his boyhood haunts — the barbershop, the pool hall, the movie theater, the farms, the grain bins, the open fields, the school, the churches — and their inhabitants. Characters, all.

“I got to know that town inside out, upside down, I got to know every square inch. I could still do the newspaper route today and name the people pretty much.”

His parents, whose divorce after he left home shocked him despite their frequent disagreements, were long-suffering souls. His tight-lipped father said little besides the curse words he expertly strung together in a kind of profane poetry. When the son tried imitating him he got his mouth washed out with soap for the trouble. As family lore has it, Will’s mother gave birth to him after milking a cow. Only after completing her chore did she give in to labor’s call. That’s the kind of hardy, stubborn, we-shall-endure stock he comes from.

Kloefkorn didn’t want to end up like his embittered, pent-up father or his German immigrant grandfather, whom he admired and despaired for at the same time.

“My granddad was one of my heroes, I worshiped that guy. He had all kinds of ability, all kinds of talent. His wife was a former school teacher, a very sharp woman. She gave up her teaching when she married him to become the farmer’s wife. They just eked out an existence on their little farm. He was so happy he escaped his family, his father was abusive. He counted himself lucky to have gotten away from it.”

Similarly, Will’s father counted himself lucky to have escaped the family farm and Will deemed himself fortunate to have avoided a dreary hand-to-mouth life.

He said his grandfather “resorted to the last bastion of hope, which is called religion, and religion of the most sordid type– right-wing fundamentalism. It did suppress all vestiges of imagination and creativity. As a young man my grandfather had been a member of what he called illiterarie. They had read and memorized a lot of stuff. Anything fun became a sin in this Old Testament, fire-and-brimstone, Pentecostal church. I detest that church with a passion.”

An unrepentant agnostic, Kloefkorn takes delight, as his grandpa did, in tweaking the nose of authority and decorum. He makes no bones about his quarrel with God. He has no truck with organized religion, no use for puffery or counterfeit dandies.

“My grandfather, much to the chagrin of my grandmother, would recite stories he’d memorized (and perform songs on his accordion). I was fascinated by his language, not only with the stories but the way he delivered them. It was delightful and at the same time it was pathetic.”

The poet has oft-written about Grandpa Charles.

The first inkling of a writing life came in high school, with the arrival of a comely young female English teacher who recognized in Will a bright, curious mind that needed to be challenged. He didn’t read much of anything outside what was assigned, which was little to start with, but he did like what he read. Similarly, he just wrote what was assigned.

“She noticed I wasn’t doing very much. I said, ‘Well, to be honest with you, I’m taking this because I’ve taken it before and I didn’t have to work very hard.’ She was very gracious about it. She totally unnerved me by saying, ‘Look, if you’re not too

interested in what’s going on in class why don’t you do me a favor,’ and I thought she’d say drop the class, but she said, ‘and instead of attending class go to study hall and write something for me. By the end of two weeks bring it to me and we’ll look it over.’ I couldn’t believe it.”

Kloefkorn said he dawdled the first week away not doing “hardly anything except pester a couple of gals. I had no idea what to have for her. Well, I finally began to write a story and the more I worked on it, the more I got into it and by the deadline I had it done, and that amazed me. It was a 20-page story. I took it to her and we spent an hour talking about it. She not only read it but she offered some suggestions. She said, ‘You know, you could make this a longer story or you could write another story.'” He opted to rejoin her class, but the experience had invigorated him. “I discovered I liked to write — I didn’t know that before.”

At Emporia State University he found the pathway for reaching his potential.

“That college experience for me, it was such a departure from how I’d been taught, it was such an opening up, it was incredible. That was really a big stage.”

Everything was new and different.

“The first time I was ever on a college campus was the day I matriculated,” he said.

“I took a freshman English class and I had of all things a male teacher, and I promise you I didn’t know there was such a thing. Here was a young man standing nicely dressed in front of class, sharp as a tack. On the first or second day he wrote us a poem, and I was stunned. He read it without apology, talked about it clearly, asked us about it, and I’ve never forgotten that experience.

“It was beginning to occur to me that language is so interesting and it kind of snowballed from there. I really did enjoy writing. As an undergraduate I had another professor I enjoyed writing papers for. I was writing to impress the profs, that was half of it. I wanted to do well so I worked hard.”

The English major set his sights on a teaching career. He and Eloise married between his junior and senior years in college. “It was just a good time,” he said.

He played football for a time but after quitting the team he satisfied himself as sports editor of the school paper, which he ended up managing.

“I thought maybe I wanted to be a journalist.”

He also dallied in radio for a back water station, his sonorous voice made for the air. Then his sensibilities as a writer got rocked. His younger brother John and a mutual friend showed up one day excitedly saying they’d just finished a novel that he simply had to read. They promised it would upset everything in his well-ordered world. The novel was J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and true enough once Kloefkorn read it, in a single sitting. he was never the same.