Archive

Hot Movie Takes Sunday: When cinema first seduced me – “On the Waterfront’

Hot Movie Takes Sunday

When cinema first seduced me – “On the Waterfront”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

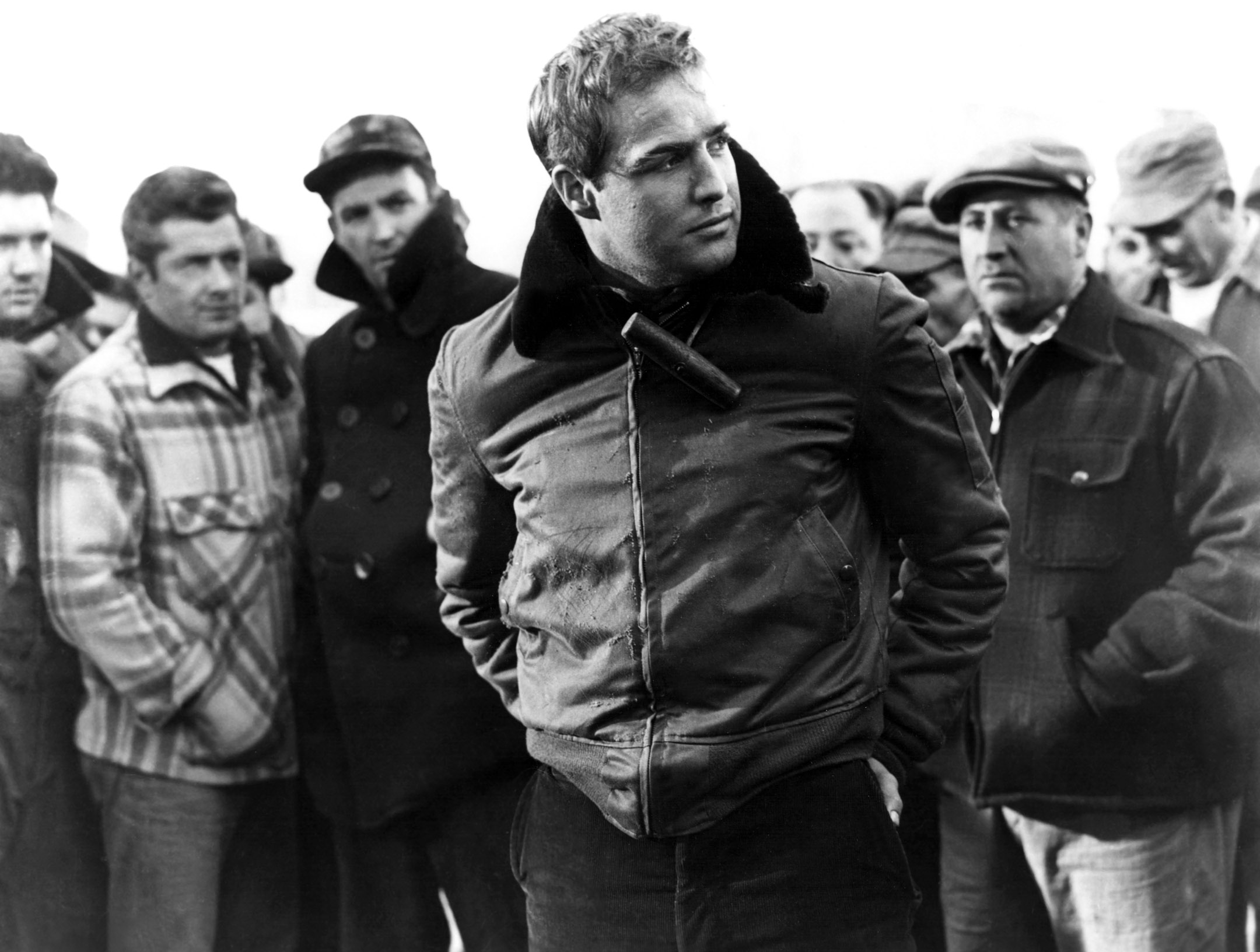

Borrowing from the title of a famous film book, I share in this hot cinema take how I lost my virginity at the movies. It wasn’t a person who stole my innocence and awakened my senses, it was a film, a very special film: “On the Waterfront.” Though in a manner of speaking you could say I gave it up to the film’s star, Marlon Brando.

It was probably the end of the 1960s or beginning of the 1970s when I first saw that classic 1954 film. I would have been 11 or 12 watching it on the home Zenith television set. The film still has a hold on me all these years later. It moves me to tears and exultation as an adult just as it did as a child. I’m sure that will never change no matter how many times I see it, and I’ve seen it a couple dozen times by now, and no matter how old I am when I revisit it.

Nothing could have prepared me for that first viewing though. I mean, it stirred things in me that I didn’t yet have words or meanings for. I remember lying on the living room’s carpeted floor and variously feeling sad, excited, aroused, afraid, angry, disenchanted, triumphant and, though I didn’t know the word at the time, ambivalent.

The power of that movie is in its extraordinary melding of words, images, ideas, faces, locations, actions and dramatic incidents. Great direction by Elia Kazan. Great photography by Boris Kaufmann. Great music by Leonard Bernstein. Great script by Budd Schulberg, Great ensemble cast from top to bottom. But it was Marlon Brando who undid me. I mean, he’s so magnetic and enigmatic at the same time. There’s a charm and mystery to the man, combined with an intensity and truth, that projects a palpable, visceral energy unlike anything I’ve quite felt since from a film performance. His acting is so real, spontaneous and connected to every moment that it evokes intense emotional immediate responses in me. It happened the first time I saw it and it still happens all these decades later. What I’m describing, of course, is the very intent of The Method Brando brought to Hollywood, thus forever changing screen acting by the new level of naturalism and truth he brought to many of his roles.

His Terry Malloy is an Everyman on the mob-controlled docks of New York. He looks like just any other working stiff or mug except he’s not because he’s an ex-prizefigher and his older brother Charley (Rod Steiger) is in the employ of waterfront boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb). The longshoremen can’t form a union and don;t dare to demand anything like decent work conditions or benefits as long as Friendly rules by threat and intimidation. In return for keeping the men in check, he and his crew take a cut of everything that comes in or goes out of those docks. And Terry, who’s part of Friendly’s mob by association, doesn’t have to lift a finger on the job. Not so long as he does what he’s told and keeps his mouth shut. A law enforcement investigation into waterfront racketeering has everyone on edge and the price for squealing is death.

A conflicted Terry arrives at a moral crossroads after being used by Friendly’s bunch to set-up a buddy, Jimmy Dolan, that henchmen throw off the roof of a brownstone. Already racked by guilt for being an accomplice in his friend’s death, Terry then falls for Dolan’s attractive sister, Edie (Eva Marie Saint), who’s intent on finding the men responsible for her brother’s killing. At the same time, the waterfront priest, Father Barry (Karl Malden), urges the longshoremen to stand up and oppose Friendly by organizing themselves and telling what they know to the authorities. Terry is questioned by investigators, one of whom detects his anguish. But he can’t bring himself to tell Father Barry or Edie the truth,

With Friendly feeling the heat, he applies increased pressure and goon tactics. Concerned that Terry may turn stool pigeon under Edie’s and Father Barry’s influence, he orders Charley to get his brother in line – or else. Terry refuses the warning and Charley pays the price. Terry then lays it all on the line and comes clean with Edie, Father Barry and the authorities. All of it leads to Terry being ostracized before a climactic confrontation with Friendly and his stooges.

“On the Waterfront” could have been a melodramatic potboiler in the wrong hands but a superb cast and crew at the peak of their powers made a masterpiece instead. It’s the unadorned humanity of the film that moves us and lingers in the imagination. Then there’s the powerful themes it explores. The film is replete with symbols and metaphors for the human condition, good versus evil and principles of sacrifice, loyalty and redemption. The story also reflects Kazan’s and Schulberg’s view that “ratting” is a sometimes necessary act for a greater good. Like Terry, Kazan became persona non grata to some for naming names before the House Un-american Activities Committee at the height of this nation’s Red Scare hysteria. Some have criticized Kazan for making a self-serving message picture that at the end celebrates the rat as hero.

The film has come under the shadow cast by Kazan’s actions. Some say his cooperating with HUAC directly or indirectly made him complicit in Hollywood colleagues getting blacklisted by the industry. However you feel about what he did or didn’t do and what blame or condemnation can be laid at his feet, the film is a stand the test of time work of social consciousness that works seamlessly within the conventions of the crime or mob film. I think considering everything that goes into a narrative movie, it’s as good a piece of traditional filmmaking to ever come out of America. There have been more visually stunning pictures, more epic ones, better written ones, but none that so compellingly and pleasingly put together all the facets that make a great movie and that so effectively get under our skin and touch our heart.

It would be a decade from the time I first saw “On the Waterfront” before I reacted that strongly to another film, and that film was “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

Hot Movie Takes Friday – Indie Film: UPDATED-EXPANDED

Hot Movie Takes Friday

Indie Film

UPDATED-EXPANDED

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

There’s a common misconception that indie films are something that only came into being in the last half-century when in fact indie filmmaking has been around in one form or another since the dawn of movies.

Several Nebraskans have demonstrated the indie spirit at the highest levels of cinema.

The very people who invented the motion picture industry were, by definition, independents. Granted, most of them were not filmmakers, but these maverick entrepreneurs took great personal risk to put their faith and money in a new medium. They were visionaries who saw the future and the artists working for them perfected a moving image film language that proved addictive. The original Hollywood czars and moguls were the greatest pop culture pushers who ever lived. Under their reign, the narrative motion picture was invented and it’s hooked every generation that’s followed. The Hollywood studio system became the model and center of film production. The genres that define the Hollywood movie, then and now, came out of that system and one of the great moguls of the Golden Age, Nebraska native Darryl F. Zanuck, was as responsible as anyone for shaping what the movies became by the projects he greenlighted and the ones he deep-sixed. The tastes and temperaments of these autocrats got reflected in the pictures their studios made but the best of these kingpins made exceptions to their rules and largely left the great filmmakers alone, which is to say they didn’t interfere with their work. If they did, the filmmakers by and large wouldn’t stand for it. After raising hell, the filmmakers usually got their way.

Zanuck made his bones in Hollywood but as the old studio system with its longterm contracts and consolidated power began to wane and a more open system emerged, even Zanuck became an independent producer.

The fat-cat dream-making factories are from the whole Hollywood story. From the time the major studios came into existence to all the shakeups and permutations that have followed right on through today, small independent studios, production companies and indie filmmakers have variously worked alongside, for and in competition with the established studios.

Among the first titans of the fledgling American cinema were independent-minded artists such as D.W. Griffith, Charles Chaplin and Douglas Faribanks, who eventually formed their own studio, United Artists. Within the studio system itself, figures like Griffith, Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Cecil B. De Mille, Frank Capra and John Ford were virtually unassailable figures who fought for and gained as near to total creative control as filmmakers have ever enjoyed. Those and others like Howard Hawks, William Wyler and Alfred Hitchcock pretty much got to do whatever they wanted on their A pictures. Then there were the B movie masters who could often get away with even more creatively and dramatically speaking than their A picture counterparts because of the smaller budgets and loosened controls on their projects. That’s why post-World War II filmmakers like Sam Fuller, Joseph E. Lewis, Nicholas Ray, Budd Boetticher and Phil Carlson could inject their films with all sorts of provocative material amidst the conventions of genre pictures and thereby effectively circumvent the production code.

Maverick indie producers such as David O. Selznick, Sam Spiegel and Joseph E. Levine packaged together projects of distinction that the studios wouldn’t or couldn’t initiate themselves. Several actors teamed with producers and agents to form production companies that made projects outside the strictures of Hollywood. Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster were among the biggest name actors to follow this trend. Eventually, it became more and more common for actors to take on producing, even directing chores for select personal projects, to where if not the norm it certainly doesn’t take anyone by surprise anymore.

A Nebraskan by the name of Lynn Stalmaster put aside his acting career to become a casting direct when he saw an opportunity in the changing dynamics of Hollywood. Casting used to be a function within the old studio system. As the studios’ contracted employee rosters began to shrink and as television became a huge new production center, Stalmaster saw the future and an opportunity. He knew just as films needed someone to guide the casting, the explosion of dramatic television shows needed casting expertise as well and so he practically invented the independent casting director. He formed his own agency and pretty much had the new field to himself through the 1950s, when he mostly did TV, on through the ’60s, ’70s’ and even the ’80s, when more of his work was in features. He became the go-to casting director for many of top filmmakers, even for some indie artists. His pioneering role and his work casting countless TV shows, made for TV movies and feature films, including many then unknowns who became stars, earned him a well deserved honorary Oscar at the 2017 Academy Awards – the first Oscar awarded for casting.

Lynn Stalmaster

Photo By Lance Dawes, Courtesy of AMPAS

In the ’50 and ’60s Stanley Kubrick pushed artistic freedom and daring thematic content to new limits as an independent commercial filmmaker tied to a studio. Roger Corman staked out ground as an indie producer-director whose low budget exploitation picks gave many film actors and filmmakers their start in the industry. In the ’70s Woody Allen got an unprecedented lifetime deal from two producers who gave him carte blanche to make his introspective comedies.

John Cassavetes helped usher in the indie filmmaker we identify today with his idiosyncratic takes on relationships that made his movies stand out from Hollywood fare.

Perhaps the purest form of indie filmmaking is the work done by underground and experimental filmmakers who have been around since cinema’s start. Of course, at the very start of motion pictures, all filmmkaers were by definition experimental because the medium was in the process of being invented and codified. Once film got established as a thing and eventually as a commerical industry, people far outside or on the fringes of that industry, many of them artists in other disciplines, boldly pushed cinema in new aesthetic and technical directions. The work of most of these filmmakers then or now doesn’t find a large audience but does make its way into art houses and festivals and is sometimes very influential across a wide spectrum of artists and filmmakers seeking new ways of seeing and doing things. A few of these experimenters do find some relative mass exposure. Andy Warhol was an example. A more recent example is Godfrey Reggio, whose visionary documentary trilogy “Koyaanisqatsi,” “Powaqqatsi” and “Naqoyqatsi” have found receptive audiences the world over. Other filmmakers, like David Lynch and Jim McBride, have crossed over into more mainstream filmmaking without ever quite leaving behind their experimental or underground roots.

Nebraska native Harold “Doc” Edgerton made history for innovations he developed with the high speed camera, the multiflash, the stroboscope, nighttime photography, shadow photography and time lapse photography and other techniques for capturing images in new ways or acquiring images never before captured on film. He was an engineer and educator who combined science with art to create an entire new niche with his work.

Filmmakers like Philip Kaufman, Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese and many others found their distinctive voices as indie artists. Their early work represented formal and informal atttempts at discovering who they are as

Several filmmakers made breakthroughs into mainstream filmmaking on the success of indie projects, including George Romero, Jonathan Kaplan, Jonathan Demme, Omaha’s own Joan Micklin Silver, Spike Lee and Quentin Taratino.

If you don’t know the name of Joan Micklin Silver, you should. She mentored under veteran studio director Mark Robson on a picture (“Limbo”) he made of her screenplay about the wives of American airmen held in Vietnamese prisoner of war camps. Joan, a Central High graduate whose family owned Micklin Lumber, then wrote an original screenplay about the life of Jewish immigrants on New York’s Lower East Side in the early 20th century. She called it “Hester Street” and she shopped it around to all the studios in Hollywood as a property she would direct herself. They all rejected the project and her stipulation that she direct. Every studio had its reasons. The material was too ethnic, too obscure, it contained no action, it had no sex. Oh, and she insisted on making it in black and white,which is always a handy excuse to pass on a script. What the studios really objected to though was investing in a woman who would be making her feature film directing debut. Too risky. As late as the late 1970s and through much of the 1980s there were only a handful of American women directing feature and made for TV movies. It was a position they were not entrusted with or encouraged to pursue. Women had a long track record as writers, editors, art directors, wardrobe and makeup artists but outside of some late silent and early sound directors and then Ida Lapino in the ’50s. women were essentially shut out of directing. That’s what Joan faced but she wasn’t going to let it stop her.

Long story short, Joan and her late husband Raphael financed the film’s production and post themselves and made an evocative period piece that they then tried to get a studio to pick up, but to no avail. That’s when the couple distributed the picture on their own and to their delight and the industry’s surprise the little movie found an audience theater by theater, city by city, until it became one of the big indie hits of that era. The film’s then-unknown lead, Carol Kane, was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Actress. The film’s success helped Joan get her next few projects made (“Between the Lines,” “Chilly Scenes of Winter”) and she went on to make some popular movies, including “Loverboy,” and a companion piece to “Hester Street” called “Crossing Delancey” that updated the story of Jewish life on the Lower East Side to the late 20th century. Joan later went on to direct several made for cable films. But “Hester Street” will always remain her legacy because it helped women break the glass ceiling in Hollywood in directing. Its historic place in the annals of cinema is recognized by its inclusion in the U.S. Library of Congress collection. She’s now penning a book about the making of that landmark film. It’s important she document this herself, as only she knows the real story of what obstacles she had to contend with to get the film made and seen. She and Raphael persisted against all odds and their efforts not only paid off for them but in the doors it opened for women to work behind the camera.

The lines between true independent filmmakers and studio-bound filmmakers have increasingly blurred. Another Omahan, Alexander Payne, is one of the leaders of the Indiewood movement that encompasses most of the best filmmakers in America. Payne and his peers maintain strict creative control in developing, shooting and editing their films but depend on Hollywood financing to get them made and distributed. In this sense, Payne and Co. are really no different than those old Hollywood masters, only filmmakers in the past were studio contracted employees whereas contemporary filmmakers are decidedly not. But don’t assume that just because a filmmaker was under contract he or she had less freedom than today’s filmmakers. Believe me, nobody told Capra, Ford, Hitchcock, Wyler, or for that matter Huston of Kazan, what to do. They called the shots. And if you were a producer or executive who tried to impose things on them, you’d invariably lose the fight. Most of the really good filmmakers then and now stand so fiercely behind their convictions that few even dare to challenge them.

But also don’t assume that just because an indie filmmaker works outside the big studios he or she gets everything they want. The indies ultimately answer to somebody. There’s always a monied interest who can, if push comes to shove, force compromise or even take the picture out of the filmmaker’s hands. Almost by definition indie artists work on low budgets and the persons controlling those budgets can be real cheapskates who favor efficiency over aesthetics.

Payne is the rarest of the rare among contemporary American filmmakers in developing a body of work with a true auteurist sensibility that doesn’t pander to formulaic conventions or pat endings. His comedies play like dramas and they’re resolutely based in intimate human relationships between rather mundane people in very ordinary settings. Payne avoids all the trappings of Hollywood gloss but still makes his movies engaging, entertaining and enduring. Just think of the protagonists and plotlines of his movies and it’s a wonder he’s gotten any of them made:

Citizen Ruth–When a paint sealer inhalant addict with a penchant for having kids she can’t take care of gets pregnant again, she becomes the unlikely and unwilling pivot figure in the abortion debate.

Election–A frustrated high school teacher develops such a hate complex for a scheming student prepared to do anything to get ahead that he rigs a student election against her.

About Schmidt–Hen-pecked Warren Schmidt no sooner retires from the job that defined him than his wife dies and he discovers she cheated on him with his best friend. He hits the road to find himself. Suppressed feelings of anger, regret and loneliness surface in the most unexpected moments.

Sideways–A philandering groom to be and a loser teacher who’s a failed writer go on a wine country spree that turns disaster. Cheating Jack gets the scare of his life. Depressed Miles learns he can find love again.

The Descendants–As Matt King deals with the burden of a historic land trust whose future is in his hands, he learns from his oldest daughter that his comatose wife cheated on him. With his two girls in tow, Matt goes in search of answers and revenge and instead rediscovers his family.

Nebraska–An addled father bound and determined to collect a phantom sweepstakes prize revisits his painful past on a road trip his son David takes him on.

Downsizing–With planet Earth in peril, a means to miniaturize humans is found and Paul takes the leap into this new world only to find it’s no panacea or paradise.

Payne has the cache to make the films he wants to make and he responsibly delivers what he promises. His films are not huge box office hits but they generally recoup their costs and then some and garner prestige for their studios in the way of critical acclaim and award nominations. Payne has yet to stumble through six completed films. Even though “Downsizing” represents new territory for him as a sci-fi visual effects movie set in diverse locales and dealing with global issues, it’s still about relationships and the only question to be answered is how well Payne combines the scale with the intimacy.

Then there are filmmakers given the keys to the kingdom who, through a combination of their own egomania and studio neglect, bring near ruin to their projects and studios. I’m thinking of Orson Welles on “The Magnificent Ambersons,” Francis Ford Coppola on “One from the Heart”, Michael Cimino on “Heaven’s Gate,” Elaine May on “Ishtar” and Kevin Costner on “Thw Postman” and “Waterworld.” For all his maverick genius, Welles left behind several unfinished projects because he was persona non grata in Hollywood, where he was considered too great a risk, and thus he cobbled together financing in a haphazard on the fly manner that also caused him to interrupt the filming and sometimes move the principal location from one site to another, over a period of time, and then try to match the visual and audio components. Ironically, the last studio picture he directed, “Touch of Evil,” came in on budget and on time but Universal didn’t understand or opposed how he wanted it cut and they took it out of his hands. At that point in his career, he was a hired gun only given the job of helming the picture at the insistence of star Charlton Heston and so Welles didn’t enjoy anything like the final cut privileges he held on “Citizen Kane” at the beginning of his career.

Other mavericks had their work compromised and sometimes taken from them. Sam Peckinpah fought a lot of battles. He won some but he ended up losing more and by the end his own demons more than studio interference did him in.

The lesson here is that being an independent isn’t always a bed of roses.

Then again, every now and then a filmmaker comes out of nowhere to do something special. Keeping it local, another Omahan did that very thing when a script he originally wrote as a teenager eventually ended up in the hands of two Oscar-winning actors who both agreed to star in his directorial debut. The filmmaker is Nik Fackler, the actors are Martin Landau and Ellen Burstyn and the film is “Lovely, Still.” It’s a good film. It didn’t do much business however and Fackler’s follow up film,” Sick Birds Die Easy,” though interesting, made even less traction. His film career is pretty much in limbo after he walked away from the medium to pursue his music. The word is he’s back focusing on film again.

Other contemporary Nebraskans making splashes with their independent feature work include actor John Beasley, actress Yolonda Ross and writer-directors Dan Mirvish, Patrick Coyle, Charles Hood and James E. Duff.

These folks do really good work and once in a while magic happens, as with the Robert Duvall film “The Apostle” that Beasley co-starred in. It went on to be an indie hit and received great critical acclaim and major award recognition. Beasley is now producing a well-budgeted indie pic about fellow Omahan Marlin Briscoe. Omahan Timothy Christian is financing and producing indie pics with name stars through his own Night Fox Entertainment company. Most of the films these individuals make don’t achieve the kind of notoriety “The Apostle” did but that doesn’t mean the work isn’t good. For example, Ross co-starred in a film, “Go for Sisters,” by that great indie writer-director John Sayles and I’m sure very few of you reading this have heard of it and even fewer have seen it but it’s a really good film. Hood’s comedy “Night Owls” stands right up there with Payne’s early films. Same for Duff’s “Hank and Asha.”

Indie feature filmmaking on any budget isn’t for the faint of heart or easily dissuaded. It takes guts and smarts and lucky breaks. The financial rewards can be small and the recognition scant. But it’s all about a passion for the work and for telling stories that engage people.

More Hot Movie Takes

More Hot Movie Takes

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film

Dennis O’Keefe

These riffs are about some very different cinema currents but they’re all inspired by recent screen discoveries I made once I put my movie snobbery in check.

My first riff concerns an actor from Old Hollywood I was almost entirely unfamiliar with and therefore I never thought to seek out his work: Dennis O’Keefe. I discovered O’Keefe only because I finally made an effort to watch some of Anthony Mann’s stellar film noirs from the 1940s. O’Keefe stars in two of them – T-Men” (1947) and “Raw Deal” (1948). Neither is a great film but the former has a very strong script and the latter is like an encyclopedia of noir and they both feature great cinematography by John Alton and good performances across the board. These are riveting films that stand up well against better known noirs, crime and police pics.

Whatever restrictions the filmmakers faced making these movies for small poverty eow studios they more than made up for with their inventiveness and passion.

As wildly atmospheric and evocative as Alton’s use of darkness, light and shadow is in these works, it’s O’Keefe’s ability to carry these films that’s the real revelation for me. I find him to be every bit as charismatic and complex as Humphrey Bogart. James Cagney, Robert Mitchum and other bigger name tough guys of the era were, and I’m certain he would have carried the best noirs they helped make famous. O’Keefe reminds me of a blend between Bogart and Cagney, with a touch of another noir stalwart, William Holden, thrown in. Until seeing him in these two pictures along with another even better pic, “Chicago Syndicate” (1955) directed by the underrated Fred F. Sears, who is yet another of the discoveries I’m opining about here, I had no idea O’Keefe delivered performances on par with the most iconic names from the classic studio system era. It just goes to show you that you don’t know what you don’t know. Before seeing it for myself – if you’d tried to tell me that O’Keefe was in these other actors’ league I would have scoffed at the notion because I would have assumed if this were so he’d have come to my attention by now. Why O’Keefe never broke through from B movies to A movies I’ll never know, but as any film buff will tell you those categories don’t mean much when it comes to quality or staying power. For example, the great noir film by Orson Welles Touch of Evil was a B movie all the way in terms of budget, source material, theme and perception but in reality it was a bold work of art by a master at the top of his game. It even won an international film prize in its time, though it took years for it to get the respect it deserved in America.

Like all good actors, O’Keefe emphatically yet subtly projects on screen what he’s thinking and feeling at any given moment. He embodies that winning combination of intelligence and intuition that makes you feel like he’s the smartest guy in the room, even if he’s in a bad fix.

My admittedly simplistic theory about acting for the screen is that the best film/TV actors convey an uncanny and unwavering confidence and veracity to the camera that we as the audience connect to and invest in with our own intellect and emotion. That doesn’t mean the actor is personally confident or needs to play someone confident in order to hook us, only that within the confines of playing characters they make it seem as though they believe every word they say and every emotion they express. Well, O’Keefe had this in spades.

Now that O’Keefe is squarely on my radar, I will search for of his work. I recommend you do the same.

By the way, another fine noir photographed by John Alton, “He Walks by Night,” starring Richard Basehart, may have been directed, at least in part, by Mann. Alton’s work here may be even more impressive than in the other films. The climactic scene is reminiscent of “The Third Man,” only instead of the post-war Vienna streets and canals, the action takes place in the Los Angeles streets and sewers. I must admit I was not familiar with Alton’s name even though I’d seen movies he photographed before I ever come upon the Mann trilogy. For example, Alton’s last major feature credit is “Elmer Gantry,” a film I’ve seen a few times and always admired. He also did the great noir pic “The Big Combo” directed by Joseph E. Lewis. And he lit the great dream sequence ballet in “”An American in Paris,” for which he won an Oscar. Now I will look at those films even more closely with respect to the photography, though I actually do remember being impressed by the photography in “Big Combo” and, of course, the dream sequence in “Paris.”

Alton was an outlier in going against prevailing studio practices of over-lighting sets. He believed in under-lighting and letting the blacks and greasy help set mood. The films he did are much darker, especially the night scenes, than any Hollywood films of that time. He studied the work of master painters to learn how they controlled light and he applied his lessons to the screen.

It turns out that Alton left Hollywood at the peak of his powers because he got fed up with the long hours and the many fights he had with producers and directors, many of whom insisted on more light and brighter exposures. Alton usually got his way because he knew his stuff, he worked very fast and he produced images that stood out from the pack. Apparently he just walked away from his very fine career sometime in the early 1960s to lead a completely distant but fulfilling life away from the movies.

Alton setting up a shot in “Raw Deal”

With actress Leslie Caron – “An American In Paris

Regarding the aforementioned “Chicago Syndicate,” it’s a surprisingly ambitious and labyrinthian story told with great verve and conviction by Fred Sears. It’s a neat bridge film between the very composed studio bound tradition and the freer practical location tradition. Sears was another in a long line of B movie directors with great skill who worked across genres in the 1930s through 1950s period. I watched a bit of a western he did and it too featured a real flair for framing and storytelling. His work has some of the great energy and dynamic tension of Sam Fuller and Budd Boetticher from that same period. I can’t wait to discover more films by Sears.

Nebraska’s own Lynn Stalmaster gets long overdue Oscar

Nebraska’s own Lynn Stalmaster gets long overdue Oscar

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film

If you’re like most Nebraskans who watched the Academy Awards last night, you’re probably unaware that one of the receipients of an Honorary Oscar is one of our own – Omaha native Lynn Stalmaster. Stalmaster made history last night as the first casting director so honored by the Academy. That it should have ben Stalmaster is appropriate since, as the attached IndieWire article explains, he basically helped invent the role of the independent casting agent at the very moment the old Hollywood studio system was beginning to dismantle and the rise of independent production companies came to the fore. Casting in old Hollywood was done internally within the studio apparatus or factory system. Stalmaster, who was an actor himself, saw the need and opportunity for a casting expert to help producers and directors identity, audition and assemble casts for their projects. He became the king of casting in Hollywood, for both television and film, from the early 1950s through the 1990s. He discovered many actors who went on to become stars and he cast countless landmark shows and films by legendary directors. Many actors went on to be nominated for Emmys or Oscars, some even winning these awards, for their performances in the roles he cast them in.

From Omaha World-Herald and the Hollywood Reporter:

He was born in Omaha in 1927 to Nebraska District Judge Irvin A. and Estelle Lapidus Stalmaster, and he attended Dundee Elementary School. His father’s made his early career as an assistant state and Douglas County attorney before serving on the Nebraska Supreme Court. The family moved to California in 1938, when Lynn was 12. A self-described “shy child”, he came “out of his shell” during high school and college via acting. He enjoyed a good measure of success as a professional actor, though one day while working as an assistant to a group of producers, including fellow Omahan Phillip Krasne, he was asked to cast some shows. Soon, he was looking for cowboys for the television western, “Gunsmoke.”

Lynn Stalmaster

He cast more than 400 productions during almost 50 years in the industry and is credited with identifying the talent and jumpstarting the careers of John Travolta, William Shatner, Jon Voight and Richard Dreyfuss, among many others. He even earned the nickname “Master Caster.”

“Before Lynn, no one really knew who John was,” Travolta’s manager, Bob LeMond said

The rest, as they say, is history. For many, Stalmaster’s career seems glamorous and powerful; being able to create true stars; but he has said he doesn’t see it that way. “I don’t think of what I had as power. Decisions were made jointly with the director and producer. I wanted to help make the best possible film and hire the best possible actors. I had a responsibility not just to my clients, but to the actors as well.” Once asked how it feels to now be the dean of his profession, he laughed it off, “I’ve just been around the longest!”

Link here to a great IndieWire article detailing what made Lynn Stalmaster such a seminal figure in his field–

http://www.indiewire.com/2016/11/honary-oscar-lynn-stalmaster-casting-directors-1201744901/

______________________________________________

Interestingly, another local, John Jackson, who’s from Council Bluffs but often works in Omaha, is an actor turned casting director having great success in the business. John is fellow local Alexander Payne’s casting director. Payne, like other directors, wiil tell you that casting is perhaps THE single most important aspect in making a successful film. You have to have a good script, of course, but if you don’t have the right cast it won’t be as good as it could be and it might very well fail.

Cheers to Lynn Stalmaster for showing the way and for John Jackson in following in his footsteps, two of hundreds of locals who have made and continue making significant contributions to the screen world.

“The Graduate”

Courtesy of AMPAS

The following is a selected list of Lynn’s staggering credits from his IMDB. You’ll likely be familiar with dozens of the projects he worked on, but pay particular attention to the features he cast in from the 1960s through the 1980s, as he worked on many of the finest films of those decades:

2006 A Lobster Tale

2000 Battlefield Earth

1996 No Easy Way

1996 To Gillian on Her 37th Birthday

1996 Crime of the Century (TV Movie)

1996 Carpool

1995 Fluke

1994 Squanto: A Warrior’s Tale

1994 Chicago Hope (TV Series)

1994 Blue Sky

1994 There Goes My Baby

1994 Clifford

1994 Intersection

1993 The Program

1993 Guilty as Sin

1992 Double Jeopardy (TV Movie)

1992 Stay Tuned

1992 Folks!

1991 For the Boys

1991 Frankie and Johnny

1991 The Doctor

1991 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze

1990 The Bonfire of the Vanities

1990/I Havana

1990 Taking Care of Business

1990 Voices Within: The Lives of Truddi Chase (TV Movie)

1990 Crazy People

1989 Incident at Dark River (TV Movie)

1989 Welcome Home

1989 Casualties of War

1989 A Sinful Life

1989 See No Evil, Hear No Evil

1989 Margaret Bourke-White (TV Movie)

1989 Dead Bang

1989 Get Smart, Again! (TV Movie)

1989 Weekend at Bernie’s

1989 Physical Evidence

1989 Winter People

1988 The Jeweller’s Shop

1988 Split Decisions

1988 Murphy’s Law (TV Series)

1988 Lady in White

1988 Switching Channels

1987 Buck James (TV Series)

1987 Real Men

1987 Big Shots

1987 You Can’t Take It with You (TV Series)

1987 Dragnet

1987 Amazing Grace and Chuck

1987 The Fourth Protocol

1987 American Harvest (TV Movie)

1986 Sword of Gideon (TV Movie)

1986 The Wizard (TV Series)

1986 8 Million Ways to Die

1986 9½ Weeks

1986 The Best of Times

1985 The Eagle and the Bear (TV Movie)

1985 Santa Claus: The Movie

1985 Love, Mary (TV Movie)

1985 Murder: By Reason of Insanity (TV Movie)

1985 Marie

1985 The Other Lover (TV Movie)

1985 Creator

1985 George Burns Comedy Week (TV Series)

1985 Jagged Edge

1985 Joshua Then and Now

1985 Space (TV Mini-Series) 1985 Hollywood Wives (TV Mini-Series)

1985 Robert Kennedy and His Times (TV Mini-Series)

1984 The River

1984 After MASH (TV Series)

1984 The Glitter Dome (TV Movie)

1984 Songwriter

1984 Supergirl

1984 High School U.S.A. (TV Movie)

1984 Ernie Kovacs: Between the Laughter (TV Movie)

1984 Her Life as a Man (TV Movie)

1984 Harry & Son

1984 The Parade (TV Movie)

1984 Unfaithfully Yours

1984 The Lonely Guy

1984 The Master (TV Series)

1984 Something About Amelia (TV Movie)

1983 Uncommon Valor

1983 Princess Daisy (TV Movie)

1983 Rita Hayworth: The Love Goddess (TV Movie)

1983 The Right Stuff

1983 Brainstorm

1983 Hotel (TV Series)

1983 Class

1983 The Thorn Birds (TV Mini-Series)

1983 Deadly Lessons (TV Movie)

1983 Starflight: The Plane That Couldn’t Land (TV Movie)

1983 Love Is Forever (TV Movie)

1983 Invitation to the Wedding

1982 Tootsie

1982 First Blood

1982 Lookin’ to Get Out

1982 Split Image

1982 Mother Lode (uncredited)

1982 The Executioner’s Song (TV Movie)

1982 Young Doctors in Love

1982 Hanky Panky

1979-1982 Hart to Hart (TV Series)

1982 Mae West (TV Movie)

1982 American Playhouse (TV Series)

1982 Some Kind of Hero

1982 T.J. Hooker (TV Series) 1982 Making Love

1982 Prime Suspect (TV Movie)

1982 Marian Rose White (TV Movie)

1981 Modern Problems

1981 Looker

1981 Splendor in the Grass (TV Movie)

1981 Dark Night of the Scarecrow (TV Movie)

1981 Callie & Son (TV Movie)

1981 Mommie Dearest

1981 Blow Out

1981 Second-Hand Hearts

1981 Caveman

1981 Cheaper to Keep Her

1981 On the Right Track

1981 Crisis at Central High (TV Movie)

1981 A Whale for the Killing (TV Movie)

1980 Stir Crazy

1980 Superman II

1980 A Change of Seasons

1980 Enola Gay: The Men, the Mission, the Atomic Bomb (TV Movie)

1980 The Last Song (TV Movie)

1980 Foolin’ Around

1980 The Women’s Room (TV Movie)

1980 Loving Couples

1980 The Shadow Box (TV Movie)

1977-1980 Family (TV Series)

1980 Wholly Moses!

1980 When the Whistle Blows (TV Series)

1980 The Mountain Men

1980 Amber Waves (TV Movie)

1980 The Black Marble

1980 Seizure: The Story of Kathy Morris (TV Movie)

1980 Ike: The War Years (TV Movie)

1979 Being There

1979 Letters from Frank (TV Movie)

1979 The Rose

1979 Promises in the Dark

1979 The Two Worlds of Jennie Logan (TV Movie)

1979 Flesh & Blood (TV Movie)

1979 10

1979 The Last Word

1979 The Onion Field

1979 North Dallas Forty

1979 Nightwing

1979 Goldengirl

1979 Prophecy

1979 The MacKenzies of Paradise Cove (TV Series)

1979 Ashanti

1979 Fast Break

1979 Ike: The War Years (TV Mini-Series)

1979 The French Atlantic Affair (TV Mini-Series)

1978 Ishi: The Last of His Tribe (TV Movie)

1978 Superman

1978 And I Alone Survived (TV Movie)

1978 A Question of Love (TV Movie)

1978 Like Mom, Like Me (TV Movie)

1978 The Users (TV Movie)

1978 Foul Play

1978 Matilda

1978 Go Tell the Spartans

1978 Convoy

1978 Damien: Omen II

1978 Murder at the Mardi Gras (TV Movie)

1978 Stickin’ Together (TV Movie)

1978 Cindy (TV Movie)

1978 Gray Lady Down

1978 The Fury

1978 Ski Lift to Death (TV Movie)

1978 Coming Home

1978 The Betsy

1978 Fantasy Island (TV Series)

1978 The Defection of Simas Kudirka (TV Movie)

1978 How Sweet It Is!

1977 Having Babies II (TV Movie)

1977 The Night They Took Miss Beautiful (TV Movie)

1977 Young Dan’l Boone (TV Series) (

1977 You Light Up My Life

1977 New York, New York

1977 The Other Side of Midnight

1977 Good Against Evil (TV Movie)

1977 Alexander: The Other Side of Dawn (TV Movie)

1977 Nashville 99 (TV Series)

1977 Audrey Rose

1977 Black Sunday

1977 Brothers

1977 Westside Medical (TV Series)

1977 SST: Death Flight (TV Movie)

1977 Secrets (TV Movie)

1977 Fun with Dick and Jane

1977 Roots (TV Mini-Series)

1976 The Secret Life of John Chapman (TV Movie)

1976 Nickelodeon

1976 Victory at Entebbe (TV Movie)

1976 Bound for Glory

1976 Silver Streak

1976 I Want to Keep My Baby! (TV Movie)

1976 21 Hours at Munich (TV Movie)

1976 Having Babies (TV Movie)

1976 Mr. T and Tina (TV Series)

1976 The Big Bus

1976 Harry and Walter Go to New York

1976 Second Wind

1976 Farewell to Manzanar (TV Movie)

1976 James Dean (TV Movie)

1976 The Entertainer (TV Movie)

1976 Three’s Company (TV Series)

1975 The Cop and the Kid (TV Series)

1975 The Legend of Valentino (TV Movie)

1975 Beyond the Bermuda Triangle (TV Movie)

1975 Katherine (TV Movie)

1975 The Master Gunfighter

1975 Welcome Back, Kotter (TV Series)

1975 Rollerball

1975 Cornbread, Earl and Me

1975 Mandingo

1975 The Hiding Place

1975 The Wild Party

1975 Hustling (TV Movie)

1975 A Shadow in the Streets (TV Movie)

1974 Punch and Jody (TV Movie)

1974 All the Kind Strangers (TV Movie)

1974 The Crazy World of Julius Vrooder

1974 The Great Niagara (TV Movie)

1974 Kodiak (TV Series)

1974 Hurricane (TV Movie) (as Lyn Stalmaster)

1974 The Dove

1974 The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz

1974 The Family Kovack (TV Movie)

1974 Conrack

1974 Billy Two Hats

1974 Rhinoceros

1973 Cinderella Liberty

1973 Sleeper

1973 The Last Detail

1973 A Summer Without Boys (TV Movie)

1973 The Iceman Cometh

1973 The Girl Most Likely to… (TV Movie)

1973 Jonathan Livingston Seagull

1973 The Third Girl from the Left (TV Movie)

1973 Isn’t It Shocking? (TV Movie)

1973 Scorpio

1973 Class of ’63 (TV Movie)

1973 Lolly-Madonna XXX

1973 Firehouse (TV Movie)

1972 The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean

1972 The Mechanic

1972 Footsteps (TV Movie)

1972 Hickey & Boggs

1972 The New Centurions

1972 Junior Bonner

1972 The Magnificent Seven Ride!

1972 Deliverance

1972 The Wrath of God

1972 Jeremiah Johnson

1972 Pocket Money

1972 The Sixth Sense (TV Series)

1972 The Cowboys

1971 Harold and Maude

1971 If Tomorrow Comes (TV Movie)

1971 Honky

1971 The Resurrection of Zachary Wheeler

1971 Fiddler on the Roof

1971 The Organization

1971 Sweet, Sweet Rachel (TV Movie)

1971 Le Mans

1971 The Grissom Gang

1971 Bearcats! (TV Series)

1971 Valdez Is Coming

1971 Lawman

1971 The Sporting Club

1970 Monte Walsh

1970 Cannon for Cordoba

1970 They Call Me Mister Tibbs!

1970 The Hawaiians

1970 The Landlord

1970 Too Late the Hero

1970 Halls of Anger

1968-1970 Death Valley Days (TV Series)

– The World’s Greatest Swimming Horse (1968) … (casting)

1969 The Reivers

1969 Gaily, Gaily

1969 They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

1969 Viva Max

1969 Castle Keep

1969 What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice?

1969 The Bridge at Remagen

1969 The April Fools

1969 Guns of the Magnificent Seven

1969 If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium

1968 The Stalking Moon

1968 The Killing of Sister George

1968 How Sweet It Is!

1968 The Thomas Crown Affair

1968 Yours, Mine and Ours

1968 The Scalphunters

1966-1968 The Rat Patrol (TV Series)

1967 Fitzwilly

1967 Clambake

1967 Hour of the Gun

1967 Dundee and the Culhane (TV Series)

1967 In the Heat of the Night

1966-1967 Hey, Landlord (TV Series)

1966 The Iron Men (TV Movie)

1966 Return of the Magnificent Seven

1966 The Fortune Cookie

1966 And Baby Makes Three (TV Movie)

1966 The Russians Are Coming! The Russians Are Coming!

1964-1966 My Favorite Martian (TV Series)

1965-1966 Hogan’s Heroes (TV Series)

1966 Man in the Square Suit (TV Movie)

1966 Cast a Giant Shadow

1961-1966 Ben Casey (TV Series)

1965 A Rage to Live

1965 The Loved One (uncredited)

1965 The Hallelujah Trail

1965 The Satan Bug

1964-1965 My Living Doll (TV Series)

1965 The Greatest Story Ever Told

1964 Kiss Me, Stupid

1964 Slattery’s People (TV Series)

1964 Profiles in Courage

1964 Lady in a Cage

1955-1964 Gunsmoke (TV Series)

1963-1964 The Greatest Show on Earth (TV Series)

1963 The Richard Boone Show (TV Series)

1963 Irma la Douce (uncredited)

1960-1963 The Untouchables (TV Series)

1963 A Child Is Waiting

1962 Two for the Seesaw

1962 Pressure Point

1962 Don’t Call Me Charlie (TV Series)

1961-1962 The New Breed (TV Series)

1959-1962 The Detectives (TV Series)

1959-1962 Hennesey (TV Series)

1961 The Children’s Hour (uncredited)

1960-1961 Peter Loves Mary (TV Series)

1961 Harrigan and Son (TV Series)

1957-1961 Zane Grey Theater (TV Series)

1961 Gunslinger (TV Series)

1960 The Westerner (TV Series)

1960 The Law and Mr. Jones (TV Series)

1960 Guestward Ho! (TV Series)

1960 Tate (TV Series) (4 episodes)

1960 Inherit the Wind (uncredited)

1959-1960 Black Saddle (TV Series)

1959-1960 Law of the Plainsman (TV Series)

1959-1960 Johnny Ringo (TV Series)

1959 The Adventures of Hiram Holliday (TV Series)

1959 The Gale Storm Show: Oh! Susanna (TV Series)

1959 The Betty Hutton Show (TV Series)

1959 Pork Chop Hill

1959 The Third Man (TV Series)

1959 Tokyo After Dark (uncredited)

1957-1959 Whirlybirds (TV Series)

1958-1959 U.S. Marshal (TV Series)

1958 Half Human

1958 I Want to Live!

1958 When Hell Broke Loose

1958 The Texan (TV Series)

1958 The Rifleman (TV Series)

1958 Kings Go Forth (uncredited)

1957-1958 Have Gun – Will Travel (TV Series)

1957-1958 The Court of Last Resort (TV Series)

1957-1958 The Sheriff of Cochise (TV Series)

1957 The Pied Piper of Hamelin (TV Movie) (uncredited)

1957 The Walter Winchell File (TV Series)

1957 Those Whiting Girls (TV Series)

1957 Black Patch

1957 Trooper Hook

1957 Hot Rod Rumble

1957 The O. Henry Playhouse (TV Series)

1957 Official Detective (TV Series)

1956 Johnny Concho

1956 Screaming Eagles

1956 Please Murder Me!

1955-1956 Dr. Hudson’s Secret Journal (TV Series)

1955 Matinee Theatre (TV Series) (1956-1957)

1954-1955 The Lone Wolf (TV Series)

1950 Big Town (TV Series)

Hot Movie Takes: “The Incredible Shrinking Man” and “Downsizing” speak to each other and to us 60 years apart

Hot Movie Takes:

‘The’Incredible Shrinking Man”and ‘Downsizing” speak to each other and to us 60 years apart

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Media wonks like me are always looking for anniversary tie-ins between something from the past and something happening right now. Being a film buff to boot, I like finding movies from, say, Hollywood’s Golden Age, that have some thematic, visual or authorial resonance with contemporary movies. An obvious one that will be even more noticeable later this year has to do with Jack Arnold’s “The Incredible Shrinking Man” from 1957 and Alexander Payne’s “Downsizing” premiering later this year. That makes 60 years between films that have something to say to each other as well as about their respective times through the conceit of human miniaturization.

Making comparisons is always precarious but, as Payne would say, we’re only talking movies here, so relax. Besides, it’s irresistible discussing two films about small human beings even though each project’s storyline, approach, resources and era of filmmaking is radically different from the other.

Another problem with doing a comparison in this case is that “Shrinking Man” is widely available for review while “Downsizing” hasn’t even been completed yet. But I have the script to go on as well as interviews I’ve done with Payne and a good chunk of his creative team.

In the earlier film the protagonist is miniaturized by accident or fate or phenomenon and his reduction is gradual and out of his control. In the later film the protagonist’s downsizing is a choice that happens immediately upon demand. And where the 1957 film’s hero is the lone person affected by this strange and frightening event, the hero of the 2017 film is one of an entire community or population experiencing miniaturization.

For all the films’ differences, there are also some key similarities. Let’s start with fact that each has an Everyman protagonist who ends up scaled down by mechanisms that speak to the anxieties of their times. “Shrinking Man’s” Scott Carey, played by Grant Williams, is caught in a strange fog and dust out on the ocean. Given that the film is set in and was released in the first full decade of the nuclear age, the inevitable implication is that Scott’s fallen victim to radioactive fallout. Relatively little was known then about the effects of radioactivity and that’s why science fiction stories ran wild with conjectures of mutations that made things grow abnormally large. Well, here, writer Richard Matheson imagines the reverse result.

As Scott’s diminutiveness advances, he is framed against the plastic suburban world of his home that increasingly becomes a foreboding, overwhelming prison of things that heretofore were neutral when he dominated but are now threats in his fragile new state. At one stage in his downsizing the family cat becomes a terrifying predator he must run from to escape. Later, when’s he’s even smaller, he gets stranded in the basement, where everything is an epic, life or death challenge – from navigating steps looming as cliffs he must scale to getting swept away in a water heater spill that for him is the equivalent of being caught in a flood to a spider that’s no longer just a household pest but a frightening monster he must battle for hi slife. In a world where everything has spiraled out of scale, he’s a vulnerable creature subject to objects and forces he once mastered but that are now beyond his control.

Throughout the shrinking phenomenon Scott’s normal sized wife remains faithful until the differential makes things impossible to carry on anything resembling a normal relationship. He loses her and every outward artifice of his life. Stripped of all that he once used to define himself by, Scott is eventually only left with his mind, his heart and his soul. Faced with the inevitability of being reduced to a molecule, then an atom, then an electron and eventually to the smallest life particles, he enters the vast unknown of an infinite universe. It is at once sad, as he is alone, and inspiring, as he’s become fully, intimately integrated with the matter of nature itself. By the conclusion he has moved from fearful, angry, desperate and despairing to surrender. No longer resistant, he gives himself over to a new reality in which he is the first human traveler. It is among the most profound, spiritual endings in cinema history.

Without giving away too much, Payne’s “Downsizing” has its protagonist Paul choose to be miniaturized in a near future world where looming climate change catastrophe has motivated scientists to develop a means by which humans are reduced to four inches. Every day people’s motivation to take this drastic action is variously noble, practical, desperate and exploitive. The environmentally conscious are willing to sacrifice their normal lives and everything in them in order to reduce their carbon and resource footprint and thus help save the planet. On the other end of the spectrum are the hustlers, hucksters, opportunists and traffickers who see a new world of suckers to con or to conduct illegal business with. In between these extremes is Paul, played by Matt Damon, who is convinced to sign up for downsizing transformation by his wife, played by Kristen Wiig. Paul is the classic go along to get along type who doesn’t like making waves or going out on a limb. Yet he agrees to give up everything he knows to be miniaturized because he and his mate will take this leap of faith into the unknown together. Besides, there’ll be doing their part to conserve resources in the hope that enough people will do the same to stem the catastrophic, apocalyptic end of life as we know it. It’s the most dramatic decision and act of his life because once the process is complete, there is no turning or going back. It is irreversible.

Then there is the huge new industry sprung up overnight to support and outfit this pioneering alternative lifestyle. The consumerist culture of escapist cruises and retirement resorts finds new expression in the small world and its geodesic domed communities. The way people live in this manufactured, improvised reality mirrors the normal world and thus there’s a class system of haves and have-nots, desirables and undesirables, predators and preyed upon.

When the couple go in for the procedure, they are led to separate labs. Paul goes through the process only to discover his wife had last minute second-thoughts and opted to not go through with it, after all. Thus, he’s abandoned to face the small world alone. There he falls into something of a shell shock routine until he beings meeting people and seeing things he never would have met or seen before. This includes Euro-trash wheeler-dealer Goran, who can get anything for a price, and Vietnamese-American activist, Gong Jiang, who fights the injustice that confines a marginalized segment of the small world to ghettos. Paul is befriended by Goran, who wants nothing more than to corrupt the circumspect newcomer, but this good-hearted grifter settles for opening his innocent acolyte’s eyes to the illicit commerce and trade this new world order offers. He can also get Paul places he couldn’t get alone. Circumstances bring Paul and Gong together and he is at first put off by her fierce, single-minded focus but grows to admire her passion and to love her not just as a symbol of right but as a fully dimensional woman.

It is through these opposites of Gong and Goran that Paul goes on his greater adventure both within the social-political maelstrom of the downsized community and amidst the end-of-world crisis hanging over everybody, big and small alike. Indeed, he finds himself at the right place and at the right time to witness and participate in an epoch of global dimensions. His diminutive size makes him a candidate to join a group of pioneers whose mission is nothing less than securing the future of human civilization. Thus, by the end, “Downsizing” takes a spiritual turn not unlike “Shrinking” and suggests notions of man’s place in the universe, on Planet Earth and in eternity.

Both films speak eloquently to the nature of man and the nature of existence itself and what it means to be human. At the end of these respective stories, Scott and Paul prepare to embark on journeys that will take them into ever new realms of unknowns. The conclusions suggest that it’s not the end for these characters or for their fellow human beings, but rather the beginning. In the earlier film there is an underlying social consciousness that questions what have we wrought in the nuclear age in terms of our health and future. There’s also the strong suggestion that in smashing the atom and releasing its energy we have reconnected with the very essence of mankind’s beginnings and our elemental lineage with the stars. In the later film the social consciousness stream focuses on what man has done to spoil the Earth and the desperate measures taken to salvage a future for man to continue living on it. In that respect and others, these films speak across generations to each other and to us.

Before I bid peace out, a few notes about the creators of these two films:

The late Richard Matheson wrote the screenplay for “The Incredible Shrinking Man” by adapting his own novel (called “The Shrinking Man”). Matheson was a prolific and much honored author novels, short stories and screenplays for film and television and much of his best known work is in the horror, fantasy, science fiction categories. Among other things, he wrote several films for Roger Corman, including adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe works, a handful of the best episodes of the original Twilight Zone series (“Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” and my all-time favorite “Little Girl Lost”) and the made for TV movie “Duel” which made its very young director, He adapted his short story “Steel” into a Twilight Zone by the same title and decades later the story was made into the film “Real Steel” starring Hugh Jackman. Omaha’s own Mauro Fiore was the cinematographer on that 2011 adaptation. Steven Speilberg, a hot commodity in Hollywood. He also wrote a well-regarded episode of the original “Star Trek” series – “The Enemy Within.” His novel “I Am Legend” was adapted into the films “The Omega Man” and “I Am Legend.” He also worked closely with director Dan Curtis on some fine TV movies, including “The Night Stalker,” “The Night Strangler,” “Dead of Night” and a great adaptation of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” starring Jack Palance. He also wrote for Western series and, well, if you look at his IMDB credits or go to his Wikepedia page you will see just what a titan he was among American popular writers.

The director of “The Incredible Shrinking Man,” the late Jack Arnold, was a good not great filmmaker who made some interesting movies in addition to this one, including “It Came from Outer Space,” “Creature from the Black Lagoon,” “Man in the Shadow” and the made for TV “Marilyn: The Untold Story.” Most of his directing credits were for epdisodic TV shows from the 1960s through the mid-1980s.

Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor are one of Hollywood’s great writing teams. “Downsizing” represents their second original script (their first was “Citizen Ruth”) and their adaptations have included “Election,” “About Schmidt” and “Sideways.” Payne directed each of these projects and two more features that Taylor did not contribute to – “The Descendants” and “Nebraska.” “Downsizing” represents their first foray into science fiction but the script doesn’t read so much as a sci-fi picture as it does an epic yet intimate human story that straddles, like all their work, comedy and drama. Lots of big ideas are explored and expressed in the story.

Where Matheson didn’t have the advantage of a director with great sophistication in Arnold, who was a studio journeyman, Payne is a world-class Indiwood filmmaker who has total creative control over his work. And where “Shrinking Man” was limited by a smallish budget and limited visual effects, though the effects are quite good not only for that time but even by today’s standards, “Downsizing” is a big budge project employing state of the art CGI and other technologies that should make human miniaturization look far more real than ever imagined before.

“The Incredible Shrinking Man”

1957 film

7.7/10·IMDb

90%·Rotten Tomatoes

“The Incredible Shrinking Man” is a 1957 American black-and-white science fiction film from Universal-International, produced by Albert Zugsmith, directed by Jack Arnold, that starred Grant Williams and Randy Stuart. Wikipedia

Initial release: February 22, 1957

Director: Jack Arnold

Story by: Richard Matheson

Producer: Albert Zugsmith

Screenplay: Richard Matheson, Richard Alan Simmons

_ _ _

“Downsizing”

2017 film

IMDB http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1389072/

First reviews should appear by the end of May 2017

“Downsizing” is a 2017 American comedy from Paramount Pictures, produced by Jim Burke, directed by Alexander Payne, that stars Matt Damon, Kristen Wiig, Christoph Waltz, Hong Chau, Neil Patrick Harris, Jason Sudeikis and Bruce Willis.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Downsizing_(2017_film)

Initial release: December 23, 2017

Director: Alexander Payne

Story by: Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor

Producer: Jim Burke, Megan Ellison

Screenplay: Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor

‘King of Comedy’ a dark reflection of our times

‘King of Comedy’ a dark reflection of our times

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro enjoy one of the great cinema muse relationships in movie history. Few American directors have found an actor who so thoroughly inhabits their screen worlds as De Niro does his old friend’s. The pair are best known for their collaborations on:

“Mean Streets” “

“Taxi Driver”

“New York, New York”

“Raging Bull”

“Goodfellas”

“Casino”

Powerful films all. But, as you’ll read, I’m making the case for Scorsese’s least known and seen film with De Niro, “The King of Comedy,” as a woefully under-appreciated work that ranks right up there with their best teamings.

Cases can be made for five of the other six pictures they did together to be considered in the Top 100 American movies of all-time: In an unusually strong decade for film, “Mean Streets” and “Taxi Driver” are certainly among the very best of that ’70s bumper crop of New Hollywood films. The first is an alternately gritty, trippy look at the small-time mob subculture that goes much deeper than crime movies of the past ever dared. The second is a cautionary tale fever dream that anticipates the cult of celebrity around violence. Though an acquired taste because of its uncompromising fatalistic uneasy rumination on love, “New York, New York” is a lush, inspired melding of intense psychological drama, magic realism and classic MGM musical. “Raging Bull” is often cited as THE film of the ’80s for its artful, brutal take on boxer Jake Lamotta and “Goodfellas” expanded on what Coppola did with the mob in the first two “Gpdfather” films by exploring in more detail the lives of men and women bound up in that life they call “our thing.”

Just as De Niro came to the fore as an actor who penetrates characters in unusually deep, perceptive ways, Scorsese does the same as a storyteller working on the periphery of human conduct. Extremes of emotions and situations are their metier. Their mutual penchant for digging down into edgy material make them perfect collaborators. “The King of Comedy” is a dark film whose intense, deadpan approach to disturbing incidents makes it read as a straight drama much of the time. But it’s really a satire bordering on farce and theater of the absurd about obsession with fame and media. De Niro plays Rupert Pupkin, an emotionally stunted wannabe comic and talk show host who’s prepared to go to any lengths to make his show biz fantasies reality. His intrusive, hostile pursuit of affirmation and opportunity from fictional talk show host Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis) grows ever more dangerous and aggressive and eventually turns criminal. The character of Pupkin is often compared to Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver” and there are definite similarities. Both are isolated loners living in their own heads. Viewing himself as a kind of avenging angel, the loser Travis fixates on cleaning the streets of the human trash he sees around him and rescuing the child prostitute played by Jodi Foster. After growing up ridiculed and bullied, chasing autographs from celebrities, Rupert sees himself as entitled to what his fixation, Jerry Langford, has and he hatches a plot with a fellow nut case (played by Sandra Bernhard) to kidnap Jerry. Rupert’s ransom: doing a standup routine on Jerry’s show to be aired nationwide.

“King of Comedy” depicts the extremes, dangers and blurring of lines that make the object of celebrity media worship a target of an unstable mind. De Niro delivers a pitch perfect, tour de force performance as a vainglorious neurotic whose love for Jerry masks an ever bigger hate.

The film is filled with awkward, all-too-real situations that make us uncomfortable because we can identify with Pupkin’s desperate need to be liked, to be respected, to be taken seriously. The character is full of contradictions and De Niro strikes an incredible balance of grotesquerie, sweetness, delusion and determination..As Rupert, De Niro is pathetic, inspiring, scary, funny, needy and strong.

It had been awhile since I’d seen the film before catching it for free on YouTube the other night and I must say it holds up very well, and perhaps resonates even more with these times than with the time it was made and released (1983). After all, in an era when America’s elected a bombastic, egomaniacal reality TV star and grifter as president, is it such a stretch to think that someone could extort and kidnap their way onto late night television? “Triumph of the Will” (1935), “State of the Union” (1948), “A Face in the Crowd” (1957) “Medium Cool” (1969), “Network” (1976) and “Wag the Dog” (1997)show, decade by decade, the unholy alliance we’ve made with mass media’s ability to manipulate, seduce, exploit and distort. Likewise, “The King of Comedy” (1983) shows just how far some among us are prepared to go for attention, power, fame.

Watch the movie at this link–

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJ2Lc0txkbk

Now, more than three decades since the film’s release, De Niro currently stars as an old, belligerent standup in “The Comedian,” a film that Scorsese was originally going to direct but didn’t. I haven’t seen it and so I can only go by the reviews I’ve read, but it appears to be a real misfire. I will hold judgment until I see it for myself, and I want to because I’m eager to compare and contrast what De Niro did with the standup he portrays in “King” to the comic he plays in the new film.

After recently watching “The Graduate” and now “The King of Comedy,” I was reminded of what brilliant chameleons Dustin Hoffman and Robert De Niro were early in their film careers. They very much followed what Marlon Brando did during his first decade and a half in Hollywood by submerging themselves in very different characters from film to film to film. Their collections ofcharacterizations may be the most diverse in American film history. These kinds of actors are rare. The closest equivalents to them we have in contemporary cinema may be Daniel Day Lewis and Johnny Depp.

But I digress. Be sure to check out “The King of Comedy” and let me know what you think of its ballsy, over-the-top, sometimes surreal yet always thoroughly grounded take on the implications of seeking celebrity as its own reward and the thin line between harmless flights of fancy and deranged compulsion. In its view, the American Dream and the American Nightmare are two sides of the same obsession. Be careful what you ask for it seems to be saying. And don’t look now, but that schmuck and impossibly irritating, shallow moron may just be the next Big Thing in entertainmet, media or some other sphere of public inflience. There’s something Trumpian about the whole thing and its media is the message theme.

Catch me talking ‘Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film’ on the podcast – ‘The Dustin Dales Show’

THANKS, DUSTIN, FOR HAVING ME ON…

HERE’S DUSTIN’S POST ABOUT THE PODCAST EPISODE FEATURING THE SEGMENT WHERE I TALK ABOUT MY BOOK “ALEXANDER PAYNE: HIS JOURNEY IN FILM” (YOU CAN LINK BELOW TO THE BOOK’S AMAZON PAGE AND TO THE SHOW):

I want to send special thanks to Leo Adam Biga for stopping by to chat his book on Alexander Payne!

You can check out his book on Amazon here.

https://www.amazon.com/Alexander-Payne-His-Jou…/…/0997266708

Hot Movie Takes: Forty-five years later and ‘The Godfather’ still haunts us

Hot Movie Takes:

Forty-five years later and ‘The Godfather’ still haunts us

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Forty-five years ago “The Godfather” first hit screens and it immediately became embedded in American pop culture consciousness. Its enduring impact has defined the parameters of an entire genre, the mob movie, with its satisfying blend of old and new filmmaking. It’s also come to be regarded as the apogee of the New Hollywood even though it was very much made in the old studio system manner. The difference being that Coppola was in the vanguard of the brash New Hollywood directors. He would go on to direct in many different styles, but with “The Godfather” he chose a formalistic, though decidely not formulaic, approach in keeping with the work of old masters like William Wyler and Elia Kazan but also reflective of the New Waves in cinema from around the world.

I actually think his “The Conversation” and “Apocalypse Now” are better films than “The Godfather” and “The Godfather II” because he had even more creative control on them and didn’t have the studios breathing down his neck the way he did on the first “Godfather” film.

But there is no doubt that with “The Godfather” and its sequel he and his creative collaborators gave us indelible images. enduring lines, memorable characters, impressive set pieces and total immersion in a shadowy world hitherto unknown to us.

I think it’s safe to say that while any number of filmmakers could have made a passable adaptation of the Maria Puzo novel then, only Francis Ford Coppola could have given it such a rich, deeply textured look and feel. He found a way into telling this intimate exploration of a crime family pursing its own version of the American Dream that was at once completely specific to the characters but also totally universal. Their personal, familial journey as mobsters, though foreign to us, became our shared journey because the layered details of their daily lives, aspirations and struggles mirrored in many ways our own.

In many ways “The Godfather” saga is the classic tale of The Other, in this case an immigrant patriarch who uses his guile and force of personality to find extra legal ways of serving the interests of his people, his family and the public.

Coppola was ideally suited to make the project more than just another genre movie or mere surface depiction of a colorful subculture because he straddled multiple worlds that gave him great insights into theater, literature, cinema, culture, history, this nation and the Italian-American experience. Growing up in 1940s-1950s New York, Coppola was both fully integrated into the mainstream as a second generation Italian-American and apart from it in an era when ethnic identity was a huge thing.

The filmmaker’s most essential skill is as a writer and with “The Godfather” he took material that in lesser hands could have been reduced to stereotypes and elevated it to mythic, Shakespearean dimensions without ever sacrificing reality. That’s a difficult feat. He did the same with “Patton,” the 1970 film he wrote but that Franklin Schaffner helmed.

Of course, what Coppola does in the sequel to “The Godfather” is truly extraordinary because he goes deeper, more epic yet and still never loses the personal stories and characterizations that anchor the whole thing. In “The Godfather II,” which is partly also a prequel, he establishes the incidents, rhythms and motivations that made Don Corleone who he was when we meet him in the first film. Of course, Coppola subsequently reedited “Godfather I and II” to create a seamless, single narrative that covers the genesis and arc of the Corleone empire in America and its roots in Italy.

“Godfather III” does not work nearly as well as the first two films and seems a forced or contrived rather than organic continuation and culmination of the saga.

The best directors will tell you that casting, next to the script and the editing process, is the most important part of filmmaking and with the first two “Godfather” films, which are hard to separate because they are so intertwined, Coppola mixed and matched a great stew of Method and non-Method actors to create a great ensemble.

The depth of acting talent and pitch perfect performances are staggering: Brando, Pacino, Caan, Cazale, Duvall, Conte, Hayden, Keaton, Castellano, Marley, Lettieri, Vigoda, Shire, Spradlin, Rocco, De Niro. Strasberg, Kirby, “Godfather I and II” arguably the best cast films of all time, from top to bottom. One of the best portrayals is by an actor none of us have ever heard of – Gastone Moschin. He memorably plays the infamous Fanucci in Part II. And there are many other Italian and American actors whose names are obscure but whose work in those films is brilliant. Coppola is a great director of actors and he beautifully blends and modulates these performances by very different players.

Coppola’s great way into the story was making it a dark rumination on the American Dream. He saw the dramatic potential of examining the mafia as a culture and community that can exist outside the law by exploiting the fear, avarice and greed of people and working within the corruption of the system to gain power and influence. Personally, I’ve always thought of the films as variations of vampire tales because these dark, brooding characters operate within a very old, secret, closed society full of ritual. They also prey on the weak and do their most ignominious work at night, under the cover of darkness. drawing the blood of the innocent and not so innocent alike. While these mob creatures do not literally feast on blood, they do extract blood money and they do willfully spill blood, even from colleagues, friends and family. No one is safe while they inhabit the streets. Alongside the danger they present, there is also something seductive, even romantic about mobsters operating outside the law/ And there is also the allure of the power they have and the fear they incite.

“The Godfather” set the standard for crime films from there on out. It’s been imitated but never equaled by those who’ve tried. Sergio Leone took his own singular approach to the subject matter in “Once Upon a Time in America” and may have actually surpassed what Coppola did. Michael Mann came close in “Heat.” But Coppola got there first and 45 years since the release of “The Godfather” it has not only stood the test of time but perhaps even become more admired than before, if that’s even possible. That film and its sequel continue to haunt us because they speak so truthfully, powerfully and personally to the family-societal-cultural-political dynamics they navigate. For all their venal acts, we care about the characters because they follow a code and we can see ourselves in them. We are equally repelled and attracted to them because they embody the very worst and best in us. And for those reasons these films will always be among the most watched and admired of all time.

‘The Graduate’ revisited

‘The Graduate’ revisited

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

This is the 50th anniversary for a much beloved yet peculiar film,“The Graduate” (1967), that landed as a sensation in its time, became an adored artifact of the 1960s but has steadily lost some of its stature and allure over the proceeding half-century. I watched it again the other night and while it’s a film I’ve always admired and I still enjoy I can see now that it’s a strange thing to have resonated so deeply in any era, even in its own breaking-the-rules time.

I mean, the new college graduate protagonist Benjamin Braddock sleeps with the mother of a childhood friend and then falls in love with the daughter and interrupts her marriage to run off with her. It’s a preposterous plot line but it works, which is to say we go along with it, because the film is basically a farcical, satirical indictment of the establishment and an embrace of youthful rebellion and following your heart. The performances by a very fine cast mostly hold up. the writing perhaps less so and the direction is, well, needlessly showy. Mike Nichols was a Broadway wunderkind and a fresh force in cinema who helped push American filmmaking more in the direction of the various European New Wave movements with rapid cutting, restless camera, nonlinear structure and frank exposition. He veered dangerously close to going over the top with it all in his first three features – “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf?,” “The Graduate” and “Catch 22” – I suspect because he was enthralled with the new freedom cinema offered and was just insecure enough not to trust the material to hold our attention without using various tricks. His much later work (“Working Girl,” “Charlie Wilson’s War”) is far more traditional, visually and technically speaking, but far more satisfying, too.