Archive

The Brothers Sayers: Big legend Gale Sayers and little legend Roger Sayers (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Whether you’re visiting this blog for the first time or you’re returning for a repeat visit, then you should know that among the vast array of articles featured on this site is a series I penned for The Reader (www.thereader.com) in 2004-2005 that explored Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. We called the 13-part, 45,000 word series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. The following story is one installment from that series. It features a pair of brothers, Gale Sayers and Roger Sayers, whose athletic brilliance made each of them famous in their own right, although the fame of Gale far outstripped that of Roger. Gale, of course, became a big-time football star at Kansas before achieving superstardom with the NFL‘s Chicago Bears. An unlikely set of circumstances saw his playing career end prematurely yet make him an even larger-than-life figure. A made-for-TV movie titled Brian’s Song (since remade) that detailed his friendship with cancer stricken teammate Brian Piccolo, cemented his immortal status, as did being elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame at age 29. Roger’s feats in both football and track were impressive but little seen owing to the fact he competed for a small college (the then-University of Omaha) and never made it to the NFL or Olympics, where many thought he would have excelled, the one knock against him being his diminutive size.

The Sayers brothers are among a distinguished gallery of black sports legends that have come out of Omaha. Others include Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, and Johnny Rodgers. You will find all their stories on this site, along with the stories of other athletic greats whose names may not be familiar to you, but whose accomplishments speak for themselves.

The Brothers Sayers: Big legend Gale Sayers and little legend Roger Sayers (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.theeader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out the Win: The Roots of Greatness

This is the story of two athletically-gifted brothers named Sayers. The younger of the pair, Gale, became a sports figure for the ages with his zig-zagging runs to daylight on a football field. His name is synonymous with the Chicago Bears. His oft-played highlight-reel runs through enemy lines form the picture of quicksilver grace. His well-documented friendship with the late Brian Piccolo endear him to new generations of fans.

The elder brother, Roger, forged a distinguished athletic career of his own, one of blazing speed on cinder and grass, but one overshadowed by Gale’s success.

From their early impoverished youth on Omaha’s near north side in the 1950s the Brothers Sayers dominated whatever field of athletic competition they entered, shining most brightly on the track and gridiron. As teammates they ran wild for Roberts Dairy’s midget football squad and anchored Central High School’s powerful football-track teams. Back then, Roger, the oldest by a year, led the way and Gale followed. For a long time, little separated the pair, as the brothers took turns grabbing headlines. Each was small and could run like the wind, just like their ex-track man father. But, make no mistake about it, Roger was always the fastest.

Each played halfback, sharing time in the same Central backfield one season. Heading into Gale’s sophomore year nature took over and gave Gale an edge Roger could never match, as the younger brother grew a few inches and packed-on 50 pounds of muscle. He kept growing, too. Soon, Gale was a strapping 6’0, 200-pound prototype halfback with major-college-material written all over him. Roger remained a diminutive 5’9, 150-pound speedster whose own once hotly sought-after status dimmed when, bowing to his parents’ wishes, he skipped his senior year of football rather than risk injury. Ironically, he tore a tendon running track the next spring. His major college prospects gone, he settled for then Omaha University.

Roger went on to a storied career at UNO, where he developed into one of America’s top sprinters and one of the school’s all-time football greats. He won the 100-meters at the 1964 Drake Relays. He captured both the 100-yard and 100-meter dashes at the 1963 Texas Relays. He took the 100 and 200 at the 1963 national NAIA meet. He ran well against Polish and Soviet national teams in AAU meets. The Olympic hopeful even beat the legendary American sprinter Bob Hayes in a race, but it was Hayes, known as “The Human Bullet,” who ended up with Olympic and NFL glory, not Sayers.

As an undersized but explosive cog in UNO’s full backfield, Sayers, dubbed “The Rocket,” averaged nearly eight yards per carry and 19 yards per reception over his four-year career. But it was as a return specialist he really stood out. Using his straight-away burst, he took back to the house three punts and five kickoffs for touchdowns. He holds several school records, including highest rushing average for a season (10.2) and career (7.8) and highest punt return average for a season (29.5) and career (20.6). His 99-yard TD catch in a 1963 game versus Drake is the longest scoring play from scrimmage in UNO history.

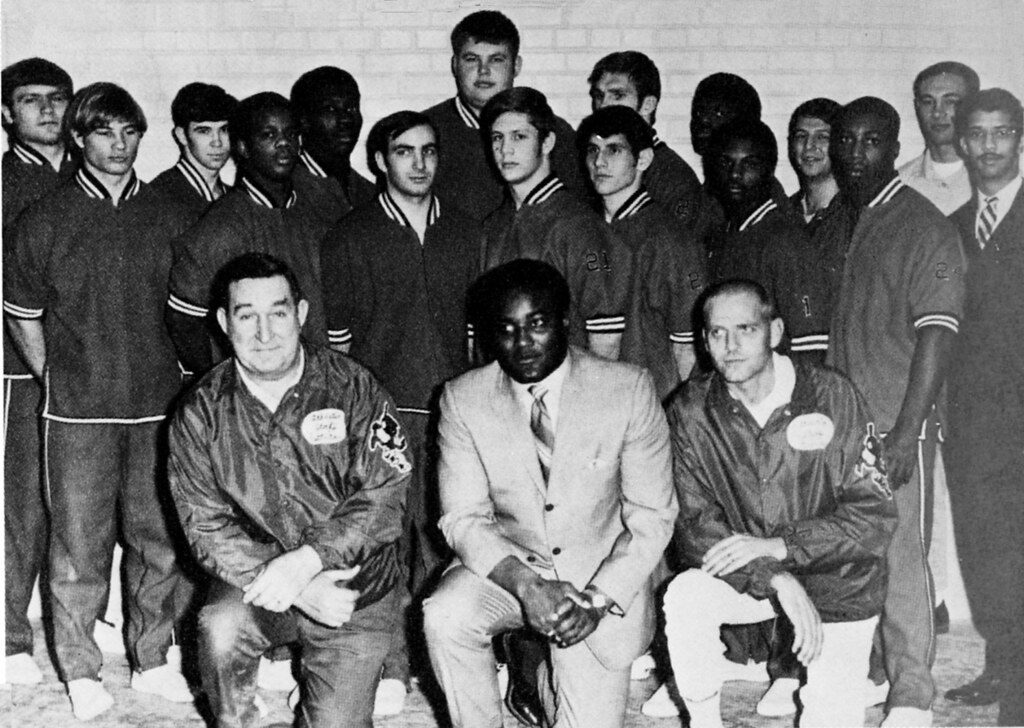

Roger Sayers running track for then-Omaha University

In football, size matters. For most of his playing career, however, Roger said his acute lack of size “never was a factor. I didn’t pay much attention to it. I didn’t lack any confidence when I got on the field. I always thought I could do well.”

Even with his impressive track credentials, Sayers, coming off an injury, was unable to find a sponsor for a 1964 Olympic bid. Even though his small stature never held him back in high school or college, it posed a huge obstacle in pro football, which after graduation he did not pursue right away because the studious and ambitious Sayers already had opportunities lined-up outside athletics. Still, in 1966, he gave the NFL a try when, after prodding from “the guys” at the Spencer Street Barbershop and a little help from Gale, he signed a free agent contract with his brother’s team, the Chicago Bears. Roger lasted the entire training camp and exhibition season with the club before bowing to reality and taking an office job.

“That’s when I realized I was too small,” Roger said of his NFL try.

Gale, the family superstar, is inducted in the college and pro football Halls of Fame but his glory came outside Nebraska, where he felt unappreciated. Racism likely prevented him being named Nebraska High School Athlete of the Year after a senior year of jaw-dropping performances. In leading Central to a share of the state football title, he set the Class A single season scoring record and made prep All-American. In pacing Central to the track and field title, he won three gold medals at the state meet, shattering the Nebraska long jump record with a leap of 24 feet, 10 inches, a mark that still stands today. He got revenge in the annual Shrine all-star game, scoring four touchdowns en route to being named outstanding player.

Recruited by Nebraska, then coached by Bill Jennings, Sayers considered the Huskers but felt uncomfortable at the school, which had ridiculously few black students then — in or out of athletics. Spurning the then-moribound NU football program for the University of Kansas, he heard people say he’d never be able to cut it in school. Sayers admits academics were not his strong suit in high school, not for lack of intelligence, but for lack of applying himself.

It took his father, a-$55-a-week car polisher, who’d walked away from his own chance at college, to set him straight. “People said I would fail. They called me dumb. But my dad said to me one time, ‘Gale, you are good enough,’ and just those words gave me the incentive that somebody believed in me. That’s all I needed. And I proved that I could do it.”

Sayers was also motivated by his brother, Roger, the bookish one who preceded him to college. Each went on to get two degrees at their respective schools.

On the field, Gale showed the Huskers what they missed by earning All-Big 8 and All-America honors as a Jayhawk and, in a 1963 game at Memorial Stadium the “Kansas Comet” lived up to his nickname by breaking-off a 99 yard TD run that still stands as the longest scoring play by an NU opponent. He was also a hurdler and long-jumper for the elite KU track program.

Upon entering the NFL with the Bears in 1965, Sayers made the most dramatic debut in league history, setting season records for total offense, 2,272, and touchdowns, 22, and a single game scoring record with 6 TDs. Named Rookie of the Year and All-Pro, he continued his brilliant play the next four seasons before the second of two serious knee injuries cut short his career in 1970. A mark of the impact he made is that despite playing only five full seasons, he’s routinely listed among the best running backs to ever play in the NFL.

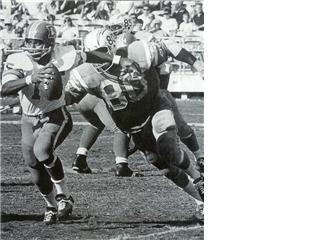

Gale Sayers with the Bears

His immortality was ensured by two things: in 1970, the story of his friendship with teammate Brian Piccolo, who died tragically of cancer, was dramatically told in a TV movie-of-the-week, Brian’s Song, (recently remade); and, in 1977, he was inducted into the pro football Hall of Fame at age 29, making him the youngest enshrine of that elite fraternity.

A quadruple threat as a rusher, receiver out of the backfield, kickoff return man and punt returner, Sayers’ unprecedented cuts saw him change directions — with the high-striding, gliding moves of a hurdler — in the blink of an eye while somehow retaining full-speed. In a blurring instant, he’d be in mid-air as he head-faked one way and swiveled his hips the other way before landing again to pivot his feet to race off against the grain. In the introduction to Gale’s autobiography, I Am Third, comic Bill Cosby may have come closest to describing the effect one of Sayers’ dramatic cuts left on him while observing from the sidelines and on the hapless defenders trying to corral him.

“I was standing there and Gale was coming around this left end. And there are about five or six defensive men ready, waiting for him…And I saw Gale Sayers split. I mean, like a paramecium. He just split in two. He threw the right side of his body on one side and the left side of his body kept going down the left side. And the defensive men didn’t know who to catch.”

The way Gale tells it, his talent for cutting resulted from his “peripheral vision,” a gift he had from the get-go. “When I was running I could see the whole field. I knew how fast the other person was running and the angle he was taking, and I knew all I had to do was make a certain move and I’m past him. I knew it — I didn’t have to think about it. I could see where people were and that gave me the ability to make up my mind what I would do before I got to a person,” he said. He reacted, on the fly, in tenths or hundreds of a second, to what he saw. “

All the so-called great moves in football are instinct,” he said. “It’s not planned. I don’t go down the football field saying, ‘Oh, this fella’s to my right, I better cut left,’ or whatever. You don’t plan it. You’re running with the football and you just do what comes natural…There were so many times in high school, college and pro ball when I was going around left end or right end and there was nothing there, and then I went the other way. You can’t teach that. That’s instinctive.”

He said his greatest asset was not speed, but quickness — combined with that innate ability to improvise on the run. “Every running back has speed, but a lot of running backs don’t have the quickness to hit a hole or to change directions, and I always could do that. A lot of times a hole is clogged and then you’ve got to do something else — either change directions or hit another hole or bounce it to the outside and go someplace else.”

Lightning fast moves may have sprung from an unlikely source — flag football, something Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers also credits with helping develop his dipsy-doodle elusiveness.

“The flags were pretty easy to grab and pull out,” Sayers said, “and so, yes, you had to develop some moves to keep people away from the flags.” The Sayers boys got their first exposure to organized competition playing in the Howard Kennedy Grade School flag football program coached by Bob Rose. An old-school disciplinarian who mentored many of north Omaha’s greatest athletes when they were youths, Rose embodied respect.

“He was a tough coach. I think he had a little attitude that said, in being black, you’ve got to be twice as good, and I think he tried to instill that in us at an early age. He’d say things like, ‘You have to be faster, you have to be tougher, you’ve got to hit harder.’ We all developed that attitude that, ‘Hey, we’ve got to do better because we’re black.’ And I think that stuck with me,” Gale said.

According to Roger, coaches like Rose and the late Josh Gibson (Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson’s oldest brother), whom the brothers came in contact with playing summer softball, “made it possible for people to succeed. They were good coaches because they taught you the fundamentals, they taught you to be respectful of people and they taught you the ethics of the game. These were folks that…made sure you played in an organized, structured event, so you could get the most out of it. They also had an uncanny ability to identify athletes and to motivate athletes to want to play and to achieve. They were part of an environment we had growing up where we had strong support systems around us.”

From the mid-1950s through the late 1960s Omaha’s inner city produced a remarkable group of athletes who achieved greatness in a variety of sports. Many observers have speculated on the whys and hows of that phenomenal run of athletic brilliance. The consensus seems to be that athletes from the past didn’t have to contend with a lot of the pressures and distractions kids face today, thus allowing a greater concentration on and passion for sports.

“Growing up, we didn’t have access to cars or play stations or arcade games,” Roger said. “We didn’t have to deal with the intense peer pressure kids are influenced by today. Because we didn’t have these things, we were able to focus in on our sports.”

For black youths like the Sayers and their buddies, options were even more confining in the ‘50s, when racial minorities were denied access to recreational venues such as the Peony Park pool and were discouraged from so-called country-club activities such as golf, which left more time and energy to devote to traditional inner city sports. “

Every day after school we were in Kountze park or some place playing a sport — football, basketball, baseball, whatever it may be. There wasn’t a whole lot else we could do,” Gale said. “So, we were in the park playing sports. Our mamas and daddies had to call us to come eat dinner because we were out there playing.”

Gale said that as youths he and his friends had such a hunger for football that after completing flag football practice, they would then go to the park to knock heads “with the big kids” from local high schools in pick-up games. “It’s a wonder no one ever got seriously injured because we had no pads, no nothing, and we played tackle. It really made us tougher.”

Dennis Fountain, a friend and fellow athlete from The Hood, said the Sayers would often compete for opposing sides in those informal games. “You wouldn’t think those two guys were brothers,” he said. “They would mix it up good.”

Speaking of tough, the brothers tussled in a pair of now mythic neighborhood football games held around the holidays. There was the Turkey Bowl played on Thanksgiving and the Cold Bowl played on Christmas. “We had some knock-down, drag-out athletic contests out there,” said Gale, referring to the annual games that drew athletes of all ages from Omaha’s north and south inner city projects. “We were a little young, but the fellas’ saw the talent we had and let us play.”

Then, there was the rich proving ground he and Roger found themselves competing in — playing with or against such fine athletes as the Nared brothers (Rich and John), Vernon Breakfield, Charlie Gunn, Bruce Hunter, Ron Boone. “No doubt about it, we fed off one another. We saw other people doing well and we wanted to do just as well,” Gale said. As the Sayers began asserting themselves, they pushed each other to excel.

“When he achieved something, I wanted to achieve something, and vice versa,” Roger said. “I mean, you never wanted to be upstaged or outdone, but by the same token we were always proud and overjoyed by each other’s success. We were as competitive as brothers are.”

Roger and Gale had so much ability that the exploits of their baby brother, Ron, are obscured despite the fact he, too, possessed talent, enough in fact for the UNO grad to be a number two draft pick by the San Diego Chargers in 1968.

Each also knew his limitations in comparison with the other. Roger played some mean halfback himself, but he knew on a football field he was only a shadow of Gale, whom nature blessed with size, speed, vision and instinct. Where Gale was a fine hurdler, relay man and long-jumper, he knew he could not beat Roger in a sprint. “I wasn’t going to get into the 100 or 220-yard dash and run against him because he was much, much faster than I was,” Gale said. “He was great in track.”

As much as he downplays his own track ability, Gale held his own in one of the strongest collegiate track programs at Kansas. It was under KU track and field coach Bill Easton he discovered a work ethic and a mantra that have guided his life ever since.

“I thought I worked hard getting ready for football,” he said, “but when I joined his track team I couldn’t believe the amount of work he put me through and I couldn’t believe I could do it. But within months I could do everything he asked me to, and I was in excellent shape. He told me, ‘Gale, you cannot work hard enough in any sport, especially in track.’ The things I did for him on the track team carried on through my pro career in football.

“Every training camp I came in shape, and I mean I came in shape. I was ready to play and put the pads on the first day of camp, where many guys would go to camp to get in shape.”

On the eve of his pro career, Sayers was entertaining some doubts about how he would do when Easton reminded him what made him special. “You go for broke every time you go.” Sayers said it’s a lesson he’s always tried to follow.

A saying printed on a card atop the desk in Easton’s office intrigued Sayers. The enigmatic words said, I Am Third. When he asked his coach their meaning, he was told they came from a kind of proverb that goes, The Lord is First, My Friends are Second, I Am Third. The athlete was so taken with its meaning he went out and had it inscribed on a medallion he wore for years afterwards. His wife Linda now has it.

The saying became the title of his 1970 autobiography. The philosophy bound up in it helped him cope with the abrupt end of his playing days. “All the talent I had, the Lord gave me. And it was the Lord that decided to take it away from me,” Gale said. “That probably helped me accept the fact that, hey, I couldn’t do it anymore. I had a very short career, but a very good career. I was satisfied with that.”

Life after athletic competition has been relatively smooth for Gale and his brother. Roger embarked on a long executive corporate career, interrupted only by a stint as the City of Omaha’s Human Relations Director under Mayor Gene Leahy. He retired from Union Pacific a few years ago. Today, he’s a trustee with Salem Baptist Church. Gale served as athletic director at Southern Illinois University before starting his own sports marketing and public relations firm, Sayers and Sayers Enterprises. Next, he launched Sayers Computer Source, a provider of computer products and technology solutions to commercial customers. Today, SCS has brnaches nationwide and revenues in excess of $150 million. Besides running his companies, Sayers is in high demand as a motivational speaker.

Both men have tried distancing themselves from being defined by their athletic prowess alone.

“I want people to view me as an individual that brings something to the table other than the fact I could run track and play football. That stuff is behind me. There are other things I can do,” said Roger. For Gale, it was a matter of being ready to move on. “I’ve always said, As you prepare to play, you must prepare to quit, and I prepared to quit. I didn’t have to look back and say, What am I going to do now? I did other things.”

Getting on with their lives has been a constant with the brothers since growing up with feuding, alcoholic parents, sparse belongings and little money in “The Toe,” as Gale said residents referred to the north Omaha ghetto. His family moved to Omaha from bigoted small towns in Kansas, where the Sayers lived until Gale was 8, but instead of the fat times they envisioned here they only found despair.

Finding a way out of that cycle became an overriding goal for Gale and his brothers.

“Yes, we had tough times, but everybody in the black neighborhood had a tough time. Our dad always said, ‘Gale, Roger, Ronnie…sorry it didn’t work out for your mother and I, but you need to get your education and make something better for yourselves.’” The fact he and Roger went on to great heights taught Gale that “if you want to make it bad enough, no matter how bad it is, you can make it.”

Related Articles

- Gale Sayers’s Knee, and the Dark Ages of Medicine (fifthdown.blogs.nytimes.com)

- The 32 Greatest NFL Running Backs (sports-central.org)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Sayers: Current players should help pioneers (sports.espn.go.com)

- John Mackey’s death has Gale Sayers ticked off at today’s NFL (profootballtalk.nbcsports.com)

Bob Boozer, Basketball Immortal (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Bob Boozer

2012 UPDATE:

It is with a heavy heart I report that the hoops legend subject of this story, Bob Boozer, passed away May 19. As fate had it, I had a recent encounter with Boozer that ended up informing a story I was working on about comedian Bill Cosby. Photographer Marlon Wright and I were in Cosby’s dressing room May 6 when Boozer appeared with a pie in hand for the comedian. As my story explains, the two went way back, as did the tradition of Boozer bringing his friend the pie. You can find that story on this blog and get a glimpse through it of the warm regard the two men had for each other. For younger readers who may not know the Boozer name, he was one of the best college players ever and a very good pro. He had the distinction of playing in the NCAA Tournament, being a gold medal Olympian, and winning an NBA title.

Unless you’re a real student of basketball history, chances are the name Bob Boozer doesn’t exactly resonate for you. But it should. The Omaha native is arguably the best basketball player to ever come out of Nebraska and when he decided to spurn the University of Nebraska for Kansas State, it was most definitely the Huskers’ loss and the Wildcats’ gain. At KSU Boozer became an All-American big man who put up the kind of sick numbers that should make him a household name today. But he starred in college more than 50 years ago, and while KSU was a national power neither the team nor Boozer ever captured the imagination of the country the way, say, Cincinnati and Oscar Robertson did in the same era. But hoop experts knew Boozer was a rare talent, and he proved it by making the U.S. Olympic team, the orignal Dream Team, that he helped capture gold in Rome. And in a solid, if not spectacular NBA career he made All-Pro and capped his time in the league as the 6th man for the Milwaukee Buck’s only title.

Boozer retired relatively young and unlike many athletes he prepared for life after sports by working off-seasons in the corporate world, where he landed back in his hometown after leaving the game. If you look at the body of his work in college, he should be a sure fire college basketball hall of fame inductee, but somehow he’s been kept out of that much deserved and long overdue honor. The fact that he helped the U.S. win Olympic gold and also earned an NBA title ring puts him in rare company and makes a pretty strong case for NBA Hall of Fame consideration. Some measure of validation happened this week when the 1960 Olympic team was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

2016 UPDATE:

Bob Boozer, Basketball Immortal, to be posthumously inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame

I posted this four years ago about Bob Boozer, the best basketball player to ever come out of the state of Nebraska, on the occasion of his death at age 75. Because his playing career happened when college and pro hoops did not have anything like the media presence it has today and because he was overshadowed by some of his contemporaries, he never really got the full credit he deserved. After a stellar career at Omaha Tech High, he was a brilliant three year starter at powerhouse Kansas State, where he was a two-time consensus first-team All-American and still considered one of the four or five best players to ever hit the court for the Wildcats. He averaged a double-double in his 77-game career with 21.9 points and 10.7 rebounds. He played on the first Dream Team, the 1960 U.S. Olympic team that won gold in Rome. He enjoyed a solid NBA journeyman career that twice saw him average a double-double in scoring and rebounding for a season. In two other seasons he averaged more than 20 points a game. In his final season he was the 6th man for the Milwaukee Bucks only NBA title team. He received lots of recognition for his feats during his life and he was a member of multiple halls of fame but the most glaring omisson was his inexplicable exclusion from the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. Well, that neglect is finally being remedied this year when he will be posthumously inducted in November. It is hard to believe that someone who put up the numbers he did on very good KSU teams that won 62 games over three seasons and ended one of those regular seasons ranked No. 1, could have gone this long without inclusion in that hall. But Boozer somehow got lost in the shuffle even though he was clearly one of the greatest collegiate players of all time. Players joining him in this induction class are Mark Aguirre of DePaul, Doug Collins of Illinois State, Lionel Simmons of La Salle, Jamaal Wilkes of UCLA and Dominique Wilkins of Georgia. Good company. For him and them. Too bad Bob didn’t live to see this. If things had worked out they way they should have, he would been inducted years ago and gotten to partake in the ceremony.

|

Boozer with the Los Angeles Lakers

Bob Boozer, Basketball Immortal (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons and later reprinted in The Reader (www.thereader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness

Omahan Bob Boozer chartered a bus to Manhattan for a February 5 engagement with immortality. By the way, that’s Manhattan, Kansas, where 50 of his closest friends and family members joined him to see his jersey retired at half-time of the Kansas State men’s basketball game.

In case you didn’t know, Boozer is a Wildcat hoops legend. In the late-1950s, he was a dominant big man there. In each of his three years, he was first team all-conference. He was twice a concensus first-team All-American. And that doesn’t even speak to his elite-level AAU play, his winning an Olympic gold medal on the original “Dream Team” and his solid NBA career capped by a championship.

Unless you’re a serious student of the game or of a certain age, the name Bob Boozer may only be familiar as one adorning a road in his hometown. But, in his time, he was the real deal. He had some serious game. He overwhelmed opponents as an all-everything pivot man at Omaha Technical High from 1952-55, earned national accolades as a high-scoring, fierce-rebounding forward at K-State from 1955-59, led an AAU squad to a title, played on the legendary 1960 U.S. Olympic basketball squad and was a member of the 1971 NBA champion Milwaukee Bucks. It’s a resume few can rival.

“There’s very few guys that really had it all every step of the way, like I did. All City. All State. All Conference. All-American. Olympic gold medal. NBA world championship. Those are levels everybody would like to aspire to but very few have the opportunity,” he said.

He is, arguably, the best player not in the college hoops hall of fame. He is, by the way, in the Olympic Hall of Fame. His collegiate credentials are unquestionable. Take this career line with the Wildcats: 22 points and 10 rebounds a game. And this came versus top-flight competition, including a giant named Wilt at arch-rival Kansas, when K-State contended for the national title every year. If anything, the Feb. 5 tribute is long overdue.

Of his alma mater feting him, he said, “It’s quite an honor to have your jersey retired. That means in the history of that school you have reached the pinnacle.”

The pinnacle is where Boozer dreamed of being. His Olympic experience fulfilled a dream from his days at the old North YMCA, mere blocks from his childhood home at 25th and Erskine. Then, he reached the pinnacle of his sport in the NBA. A starter most of his pro career, he was a productive journeyman who could be counted on for double figures in points and rebounds most nights. His career NBA averages are 14.8 points and 8.1 rebounds a game. The 6’8 Boozer played in the ‘68 NBA All-Star game, an honor he just missed other years. He led the Chicago Bulls in scoring over a three-year period. He was the Bucks’ valuable 6th man in their title run.

Still, he was more a role player than a leading man. His game, like his demeanor, was steady, not sensational. He was, in his own words, “a blue-collar worker.” He could shoot like few other men his size, utilizing deadly jumpers and hook shots.

“I was a good player. I would make you pay if you made a mistake. I could move out for the jump shot and the hook shot or make a quick move for a layup,” he said.

While he admires the athleticism of today’s players, he doesn’t think much of their basic skills.

“We could flat-out outshoot these kids today. We worked awfully hard at being able to shoot the jump shot. I used to always say that a 15- to 18-foot jump shot is just like a layup. That was my mind set — that if I got it clear, it was going down.”

He perfected his shot to such a degree that in practice he could find his favorite spots on the court and nail the ball through the hoop with his eyes closed.

“It’s just something that with thousands and thousands of repetitions gets to be automatic. And when I shot I always used to try to finger the ball for the seams and to swish it because if the ball left my hand with a backward rotation and went through the net, it would hit the floor and come right back to you. That way, when you’re shooting by yourself, you don’t have to run after the ball very much,” he said, chortling with his booming bass voice.

Unlike many players who hang around past their peak, once Boozer captured that coveted and elusive ring, he left the game.

“I had made up my mind that once I walked, I walked, and would never look back. Besides, your body tells you when it’s getting near the end. I started hating the training camps a little more. The last few years I knew it was coming to an end,” he said. “The championship season with the Bucks was the culmination of my career. It was great.”

Indeed, he left without seeking a coaching or front office position. The championship was made sweeter as he shared it with an old pal, Oscar Robertson. As players, they were rivals, teammates and friends. Both were college All-Americans for national championship contending teams. As a junior, Boozer and his KSU Wildcats eliminated “The Big O” and his Cincinnati Bearcats from the 1957-58 NCAA quarterfinals. The next year Robertson turned the tables on Boozer by knocking the No. 1-ranked ‘Cats out of the regionals.

The two were teammates on the 1960 US Olympic basketball team, considered by many the best amateur basketball talent ever assembled. Besides Boozer and Robertson, the team featured future NBA stars Jerry West, Jerry Lucas and Walt Bellamy. It destroyed all comers at the Rome games, winning by an average margin of 34-plus. Then Boozer and Robertson were reunited with the Cincinnati Royals. Cincy was the site of some fat times for Boozer, who was popular and productive there. It’s also where he met his wife, Ella. The couple has one grown child and one grandchild.

After a trade to the New York Knicks that he protested, Boozer bounced around the league. He played a few years with the expansion Chicago Bulls, where he enjoyed his biggest scoring seasons — averaging about 20 points a game. He led the Bulls to the playoffs in their inaugural season — the first and last time a first-year expansion team did that.

A card from his time with the Cincinnati Royals

He had one happy season with the Los Angeles Lakers, spelling the great Elgin Baylor, before he joined Robertson in Milwaukee. With the incomparable Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at center, smooth Bob Dandridge at forward, playmaker Robertson at guard and the steady Boozer coming off the bench (he averaged 9 points and 5 boards), the Bucks, in only their second year, blew away opponents en route to a 66-16 regular season mark. They captured the franchise’s first and only championship by sweeping the Baltimore Bullets in four games.

By then, Boozer was 34 and a veteran of 11 NBA seasons with five different teams. He left the league and his then-lofty $100,000 salary to build a successful career off the court with the former Northwestern Bell-US West, now called Qwest.

Now retired from the communications giant, the 67-year-old Boozer enjoys a comfortable life with Ella in their spacious, richly adorned Pacific Heights home in Omaha, a showplace he refers to as “the fruits of my labor.” He moves stiffly from the wear and tear his body endured on the hardcourt those many years. His inflamed knee joints ache. But he recently found some relief after getting a painful hip replaced.

With his sports legacy secured and his private life well-ordered, his life appears to have been one cozy ride. Viewed more closely, his journey included some trying times, not least of which was to be denied the chance to buy a home in some of Omaha’s posher neighborhoods during the late 1960s. The racism he encountered made him angry for a long time, but in the end he made peace with his hometown.

Boozer grew up poor in north Omaha, the only son of transplanted Southerners. His father worked the production line and cleanup crew at Armour’s Packinghouse. His mother toiled as a maid at the old Hill Hotel downtown. Neither got past the 9th grade and these “God-fearing, very strict” folks made sure Bob and his older sister understood school was a priority.

“They knew racial prejudice and they said education was the way out. Their philosophy was, you kids will never have to work as hard as we did if you go get your education. We had to get good grades,” Boozer said. “My junior year in high school my mother and dad set my sister and I down and said, ‘We‚ve got enough money to send your sister to Omaha U. (UNO). You’re on your own, Bob.’ Well, it just so happened I started growing and I started hitting the basket and I figured I was probably going to get a basketball scholarship, and that came to fruition.”

No prodigy, Boozer made himself into a player. That meant long hours at the YMCA, on playgrounds and in school gyms. His development was aided by the stiff competition he found and the fine coaching he received. He came along at a time when north Omaha was a hotbed of physical talent, iron will and burning desire.

“That was a breeding ground,” he said. “All the inner city athletes were always playing ball. All day long. All night long. If you were anything in athletics, you played for the Y Travelers, a basketball team, or the Y Monarchs, a baseball team, under Josh Gibson (Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson’s older brother), who was a fine coach.”

Boozer said he spent so much time at the Y that its executive director, John Butler, “used to let me have the keys to the place. Butler provided the arena where I could work out and become an accomplished player and Josh Gibson provided the opportunity to play with older players.”

He said his dedication was such that while his buddies were out dating, “I was shooting hoops. It was a deep desire to excel. I always wanted to be a basketball player and I always wanted to be one of the best. I realized too at an early age athletics could provide me with an education.”

Athletics then, like now, were not merely a contest but a means of self-expression and self-advancement. Boozer was part of an elite lineage of black athletes who came out of north Omaha to make their mark. Growing up amid this athletic renaissance, he emulated the older athletes he saw in action, eventually placing himself under the tutelage of athletes like Bob Gibson — or “Gibby” as Boozer calls his lifelong friend, who is a year his senior. They were teammates one year each with the Y Travelers and at Tech.

“Some of the older athletes worked with me and showed me different techniques. In the inner city we basically marveled at each other’s abilities. There were a lot of great ballplayers. We rooted for each other. We encouraged each other. We were there for each other. It was like an inner city fraternity,” Boozer said. “I used to sit in the stands at Burdette Field and watch ‘Gibby’ pitch. As good a baseball player as he was, he was a finer basketball player. He could play. He could get up and hang.”

By the time Boozer played for Tech coach Neal Mosser, he was a 6’2” forward with plenty of promise but not yet an impact player. No one could foresee what happened next.

“Between my sophomore and junior years I grew six inches. With that extra six inches I couldn’t walk, chew gum and cross the street at the same time without tripping,” Boozer said. “That’s when I enlisted my friends, Lonnie McIntosh and John Nared, to help me. Lonnie, a teammate of mine at Tech, was a physical fitness buff, and John, who later played at Central, was probably one of the finest athletes to ever come out of Omaha.

“We’d go down to the Y every week. Lonnie would put me through agility drills on some days and then John and I would go one-on-one other days. John was only 6’3” but strong as a bull. I couldn’t take him in the post. I had to do everything from a guard-forward position. And, man, we used to have some battles.”

By his junior season Boozer was an imposing force — a big man with little-man skills. He could not only post-up down low to score, rebound and block shots, he could also shoot from outside, drive the lane and run the floor. With Boozer in the middle and a talented supporting cast around him, Tech was a powerhouse comprised mainly of black starters when that was rare. Then came the state tournament in Lincoln, and the bitterness of racism was brought home to Boozer and his mates.

“We had the state championship taken away from us in 1955. We played Scottsbluff. We figured we were the better team. I was playing center and I literally had guys hanging on me. The referees wouldn’t call a foul. I’d say, ‘Ref, why don‚t you call a foul?‚ and all I heard was, ‘Shut up and play ball,’ he said. “On one play, Lonnie McIntosh stole the ball and was dribbling down the sideline when one of their guys stuck his foot out and tripped him. There was Lonnie sprawled out on the floor and the referee called traveling and gave the ball to Scottsbluff. I will never forget that.

“We were outraged, but what could we do? If we had really got on the refs we’d have got a technical foul. So we had to suck it up and just play the best we could and hope we could beat ‘em by knocking in the most shots.”

Tech lost the game on the scoreboard but Boozer said players from that Scottsbluff team have since come up to him and admitted the injustice done that day. “It’s a little late,” he tells them. According to Boozer, Tech bore the brunt of discrimination in what should have been color-blind competition.

“Tech High always used to get the shaft, particularly in the state tournament.” He said Mosser, whom he regards as one of Nebraska’s finest coaches, helped him deal with “the sting of racism” by instilling a certain steeliness.

“Neal was a real disciplinarian. And he used to always tell us that life was not going to be easy. That you‚ve got to forge ahead.”

That credo was tested when Boozer became a hot recruit his senior year but was rejected by his top choice, the University of Iowa.

“Neal showed me a letter that Iowa coach Bucky O’Connor wrote telling him he had his quota of black players. “Neal said, ‘Bob, these are things you’re going to have to face and you’ve just got to persevere in spite of it.’ It hardens you. It makes you tougher.’”

Kansas was in the running until Wilt Chamberlain signed to play there. Boozer settled on Kansas State, where he made a name for himself and the Wildcats. Under coach Tex Winter, Boozer was the go-to-guy in the triangle post, an offense made famous years later by Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls.

“A lot of plays flashed across the middle. We had a double screen where I’d start underneath and come back. The off forward and guard would come down and pinch and I’d brush my guy off into them and pop out for my jump shot.”

During his three-year varsity career, the Cats went 62-15 and won two Big Eight titles. Boozer was unstoppable. His 25.6 scoring average as a senior remains a single-season record. He ranks among KSU’s all-time leaders in points and boards.

In a famous 1958 duel for league, intrastate and national bragging rights, he led a 75-73 double overtime win over Wilt Chamberlain and KU in Manhattan. He outscored Wilt 32 to 25.

“Nobody could go one-on-one with Wilt. He was just too powerful. From his waist up he was almost like a weight lifter. You always had to be aware of where he was because he’d knock the ball in the 13th row. I had one move where I’d face him and fake him and he’d take a step back and I would do a crossover hook shot. He’d be up there with it and always miss it by about like that,” Boozer said, holding his index finger and thumb an inch apart. “I’d say, ‘In your face, big fella.’ And he’d say, ‘I’ll get you next time.’ Wilt and I always enjoyed each other.”

After his banner senior year the NBA came calling, with the Cincinnati Royals making Boozer the No. 1 overall draft pick, but Boozer had other ideas.

“I delayed going pro one year to keep my amateur standing and get a shot at the Olympic Trials.”

To stay sharp he played a year with the Peoria Cats of the now-defunct National Industrial Basketball League, an AAU-sanctioned developmental league not unlike today’s CBA or NBDL. Boozer worked at the Caterpillar Tractor Co. by day and played ball at night. He led his team to the NIBL title, which qualified the team and its players to showcase their talents at the Olympic Trials in Denver. Boozer and a teammate made the grade. The Rome Olympics are still among his personal highlights.

“I was a history buff and just the idea of being on the Appian Way, where the Caesars trod, and all the beauty of Rome — it was magnificent. And winning the gold medal for my country was very, very meaningful.”

Even after entering the NBA, Boozer honed his game in the off-season back home with John Nared in one-on-one duels at the Y. “If he could guard me, as small and quick as I was, he could guard anybody in the NBA,” Nared said.

“We used to go out and get dinner, go back to our rooms, light up some cigars, pop open some beers and talk basketball until the wee hours of the morning.”

Boozer prepared for post-hoops life years before he retired by participating in a summer management training program with the phone company. By the time he quit playing ball, he had a job and career waiting.

“You see, I never forgot how my mom and dad stressed getting an education and looking after your family.”

In 1997, he retired after 27 years as a community affairs executive and federal lobbyist with the communications company. Restless in retirement, he accepted an appointment that year from then-Gov. Ben Nelson to the Nebraska Parole Board. Gov. Mike Johanns reappointed him to a new six-year term running through 2006. Boozer enjoys his work.

“It’s almost like being a counselor. I’ll pull an offender aside, especially a young male from the inner city, and have a common sense conversation with him, and most times he’ll listen. I think my athletic name helps me because most young males identify with an athlete.”

Boozer’s not just any ex-athlete. He’s an immortal.

Related Articles

- Collegians Were the Olympic Basketball Show in 1960 (nytimes.com)

- The Dream Team Enters The Basketball Hall Of Fame: Can The Lakers, Bulls, And Celtics Come Too? (sbnation.com)

- Basketball Hall Of Fame Speech: The 1960 U.S. Olympic Team (sbnation.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From My Series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Closing Installment from My Series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Hoops Legend John C. Johnson: Fierce Determination Tested by Repeated Run-Ins with the Law (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Prodigal Son: Marlin Briscoe takes long road home (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

I never saw Marlin Briscoe play college football, but as I came of age people who had see The Magician perform regaled me with stories of his improvisational playmaking skills on the gridiron, and so whenever I heard or read the name, I tried imagining what his elusive, dramatic, highlight reel runs or passes looked like. Mention Briscoe’s name to knowledgable sports fans and they immediately think of a couple things: that he was the first black starting quarterback in the National Football League; and that he won two Super Bowl rings as a wide receiver with the Miami Dolphins. But as obvious as it seems, I believe that both during his career and after most folks don’t appreciate (1) how historic the first accomplishment was and (2) don’t recognize how amazing it was for him to go from being a very good quarterback in the league, in the one year he was allowed to play the position, to being an All-Pro wideout for Buffalo. Miami thought enough of him to trade for him and thereby provide a complement to and take some heat off of legend Paul Warfield.

The following story I did on Briscoe appeared not long after his autobiography came out. I made arrangements to inteview him in our shared hometown of Omaha, and he was every bit as honest in person as he was in the pages of his book, which chronicles his rise to stardom, the terrible fall he took, and coming back from oblivion to redeem himself. The story appeared in a series I did on Omaha’s Black Sports Legends, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, for The Reader (www.thereader.com) in 2004-2005. Since then, there’s been a campaign to have the NFL’s veterans committee vote Briscoe into the Hall of Fame and there are plans for a feature film telling his life story.

Prodigal Son:

Marlin Briscoe takes long road home (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness

Imagine this is your life: Your name is Marlin Briscoe. A stellar football-basketball player at Omaha South High School in the early 1960s, you are snubbed by the University of Nebraska but prove the Huskers wrong when you become a sensation as quarterback for then Omaha University, where from 1963 to 1967, you set more than 20 school records for single game, season and career offensive production.

Because you are black the NFL does not deem you capable of playing quarterback and, instead, you’re a late round draft choice, of the old AFL, at defensive back. Injured to start your 1968 rookie season, the offense sputters until, out of desperation, the coach gives you a chance at quarterback. After sparking the offense as a reserve, you hold down the game’s glamour job the rest of the season, thus making history as the league’s first black starting quarterback. When racism prevents you from getting another shot as a signal caller, you’re traded and excel at wide receiver. After another trade, you reach the height of success as a member of a two-time Super Bowl-winning team. You earn the respect of teammates as a selfless clutch performer, players’ rights advocate and solid citizen.

Then, after retiring from the game, you drift into a fast life fueled by drugs. In 12 years of oblivion you lose everything, even your Super Bowl rings. Just as all seems lost, you climb out of the abyss and resurrect your old self. As part of your recovery you write a brutally honest book about a life of achievement nearly undone by the addiction you finally beat.

You are Marlin Oliver Briscoe, hometown Omaha hero, prodigal son and the man now widely recognized as the trailblazer who laid the path for the eventual black quarterback stampede in the NFL. Now, 14 years removed from hitting rock bottom, you return home to bask in the glow of family and friends who knew you as a fleet athlete on the south side and, later, as “Marlin the Magician” at UNO, where some of the records you set still stand.

Now residing in the Belmont Heights section of Long Beach, Calif. with your partner, Karen, and working as an executive with the Roy W. Roberts Watts/Willowbrook Boys and Girls Club in Los Angeles, your Omaha visits these days for UNO alumni functions, state athletic events and book signings contrast sharply with the times you turned-up here a strung-out junkie. Today, you are once again the strong, smart, proud warrior of your youth.

Looking back on what he calls his “lost years,” Briscoe, age 59, can hardly believe “the severe downward spiral” his life took. “Anybody that knows me, especially myself, would never think I would succumb to drug addiction,” he said during one of his swings through town. “

All my life I had been making adjustments and overcoming obstacles and drugs took away all my strength and resolve. When I think about it and all the time I lost with my family and friends, it’s a nightmare. I wake up in a cold sweat sometimes thinking about those dark years…not only what I put myself through but a lot of people who loved me. It’s horrifying.

“Now that my life is full of joy and happiness, it just seems like an aberration. Like it never happened. And it could never ever happen again. I mean, somebody would have to kill me to get me to do drugs. I’m a dead man walking anyway if I ever did. But it’s not even a consideration. And that’s why it makes me so furious with myself to think why I did it in the first place. Why couldn’t I have been like I am now?”

Or, like he was back in the day, when this straight arrow learned bedrock values from his single mother, Geneva Moore, a packing house laborer, and from his older cousin Bob Rose, a youth coach who schooled him and other future greats in the parks and playing fields of schools and recreation centers in north and south Omaha.

For Briscoe, the pain of those years when, as he says, “I lost myself,” is magnified by how he feels he let down the rich, proud athletic legacy he is part of in Omaha. It is a special brotherhood. One in which he and his fellow members share not only the same hometown, but a common cultural heritage in their African–American roots, a comparable experience in facing racial inequality and a similar track record of achieving enduring athletic greatness.

Marlin Briscoe, a South High alum, is honored with a street named in his honor on Oct. 22, 2014.

Briscoe came up at a time when the local black community produced, in a golden 25-year period from roughly 1950 to 1975, an amazing gallery of athletes that distinguished themselves in a variety of sports. He idolized the legends that came before him like Bob Boozer, a rare member of both Olympic Gold Medal (at the 1960 Rome Games) and NBA championship (with the 1971 Milwaukee Bucks) teams, and MLB Hall of Famer and Cy Young Award winner Bob Gibson. He honed his skills alongside greats Roger Sayers, one of the world’s fastest humans in the early 1960s, NFL Hall of Famer Gale Sayers and pro basketball “Iron Man” Ron Boone. He inspired legends that came after him like Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers.

Each legend’s individual story is compelling. There are the taciturn heroics and outspoken diatribes of Gibson. There are the knee injuries that denied Gale Sayers his full potential by cutting short his brilliant playing career and the movies that dramatically portrayed his bond with doomed roommate Brian Piccolo. There are the ups and downs of Rodgers’ checkered life and career. But Briscoe’s own personal odyssey may be the most dramatic of all.

Born in Oakland, Calif. in 1945, Briscoe and his sister Beverly were raised by their mother after their parents split up. When he was 3, his mother moved the family to Omaha, where relatives worked in the packing houses that soon employed her as well. After a year living on the north side, the family moved to the south Omaha projects. Between Kountze Park in North O and the Woodson Center in South O, Briscoe came of age as a young man and athlete. In an era when options for blacks were few, young men like Briscoe knew that athletic prowess was both a proving ground and a way out of the ghetto, all the motivation he needed to work hard.

“Back in the ‘50s and early ‘60s we had nothing else to really look forward to except to excel as black athletes,” Briscoe said. “Sports was a rite-of-passage to respect and manhood and, hopefully, a way to bypass the packing houses and better ourselves and go to college. When Boozer (Bob) went to Kansas State and Gibson (Bob) went to Creighton, that next generation — my generation — started thinking, If I can get good enough in sports, I can get a scholarship to college so I can take care of my mom. That’s how all of us thought.”

Like many of his friends, Briscoe grew up without a father, which combined with his mother working full-time meant ample opportunity to find mischief. Except that in an era when a community really did raise a child, Briscoe fell under the stern but caring guidance of the men and women, including Alice Wilson and Bob Rose, that ran the rec centers and school programs catering to largely poor kids. By the time Briscoe entered South High, he was a promising football-basketball player.

On the gridiron, he’d established himself as a quarterback in youth leagues, but once at South shared time at QB his first couple years and was switched to halfback as a senior, making all-city. More than just a jock, Briscoe was elected student council president.

Scholarship offers were few in coming for the relatively small — 5’10, 170-pound — Briscoe upon graduating in 1962. The reality is that in the early ‘60s major colleges still used quotas in recruiting black student-athletes and Briscoe upset the balance when he had the temerity to want to play quarterback, a position that up until the 1980s was widely considered too advanced for blacks.

But UNO Head Football Coach Al Caniglia, one of the winningest coaches in school history, had no reservations taking him as a QB. Seeing limited duty as a freshman backup to incumbent Carl Meyers, Briscoe improved his numbers each year as a starter. After a feeling-out process as a sophomore, when he went 73 of 143 for 939 yards in the air and rushed for another 370 yards on the ground, his junior year he completed 116 of 206 passes for 1,668 yards and ran 120 times for 513 yards to set a school total offense record of 2,181 yards in leading UNO to a 6-5 mark.

What was to originally have been his senior year, 1966, got waylaid, as did nearly his entire future athletic career, when in an indoor summer pickup hoops game he got undercut and took a hard, headfirst spill to the floor. Numb for a few minutes, he regained feeling and was checked out at a local hospital, which gave him a clean bill of health.

Even with a lingering stiff neck, he started the ‘66 season where he left off, posting a huge game in the opener, before feeling a pop in his throbbing neck that sent him “wobbling” to the sidelines. A post-game x-ray revealed a fractured vertebra, perhaps the result of his preseason injury, meaning he’d risked permanent paralysis with every hit he absorbed. Given no hope of playing again, he sat out the rest of the year and threw himself into academics and school politics. After receiving his military draft notice, he anxiously awaited word of a medical deferment, which he got. Without him at the helm, UNO crashed to a 1-9 mark.

Then, a curious thing happened. On a follow-up medical visit, he was told his broken vertebra was recalcifying enough to allow him to play again. He resumed practicing in the spring of ‘67 and by that fall was playing without any ill effects. Indeed, he went on to have a spectacular final season, attracting national attention with his dominating play in a 7-3 campaign, compiling season marks with his 25 TD throws and 2,639 yards of total offense, including a dazzling 401-yard performance versus tough North Dakota State at Rosenblatt Stadium.

Projected by pro scouts at cornerback, a position he played sparingly in college, Briscoe still wanted a go at QB, so, on the advice of Al Caniglia he negotiated with the Denver Broncos, who selected him in the 14th round, to give him a look there, knowing the club held a three-day trial open to the public and media.

“I had a lot of confidence in my ability,” Briscoe said, “and I felt given that three-days at least I would have a showcase to show what I could do. I wanted that forum. When I got it, that set the tone for history to be made.”

At the trial Briscoe turned heads with the strength and accuracy of his throws but once fall camp began found himself banished to the defensive backfield, his QB dreams seemingly dashed. He earned a starting cornerback spot but injured a hamstring before the ‘68 season opener.

After an 0-2 start in which the Denver offense struggled mightily out of the gate, as one QB after another either got hurt or fell flat on his face, Head Coach Lou Saban finally called on Briscoe in the wake of fans and reporters lobbying for the summer trial standout to get a chance. Briscoe ran with the chance, too, despite the fact Saban, whose later actions confirmed he didn’t trust a black QB, only gave him a limited playbook to run. In 11 games, the last 7 as starter, Briscoe completed 93 of 224 passes for 1,589 yards with 14 TDs and 13 INTs and he ran 41 times for 308 yards and 3 TDs in helping Denver to a 5-6 record in his 11 appearances, 5-2 as a starter.

Briscoe proved an effective improviser, using his athleticism to avoid the rush, buy time and either find the open receiver or move the chains via scrambling. “Sure, my percentage was low, because initially they didn’t give me many plays, and so I was out there played street ball…like I was down at Kountze Park again…until I learned the cerebral part of the game and then I was able to improve my so-called efficiency,” is how Briscoe describes his progression as an NFL signal caller.

By being branded “a running” — read: undisciplined — quarterback in an era of strictly drop back pocket passers, with the exception of Fran Tarkenton, who was white, Briscoe said blacks aspiring to play the position faced “a stigma” it took decades to overcome.

Ironically, he said, “I never, ever considered myself a black quarterback. I was just a quarterback. It’s like I never thought about size either. When I went out there on the football field, hey, I was a player.”

All these years later, he still bristles at the once widely-held notions blacks didn’t possess the mechanics to throw at the pro level or the smarts to grasp the subtleties of the game or the leadership skills to command whites. “How do you run in 14 touchdown passes? I could run, sure. I could buy more time, yeah. But if you look at most of my touchdown passes, they were drop back passes. I led the team to five wins in seven starts. We played an exciting brand of football. Attendance boomed. If I left any legacy, it’s that I proved the naysayers wrong about a black man manning that position…even if I never played (QB) again.”

Despite his solid performance — he finished second in Rookie of the Year voting — he was not invited to QB meetings Saban held in Denver the next summer and was traded only weeks before the ‘69 regular season to the Buffalo Bills, who wanted him as a wide receiver.

His reaction to having the quarterback door slammed in his face? “I realized that’s the way it was. It was reality. So, it wasn’t surprising. Disappointing? Yes. All I wanted and deserved was to compete for the job. Was I bitter? No. If I was bitter I would have quit and that would have been the end of it. As a matter of fact, it spurred me to prove them wrong. I knew I belonged in the NFL. I just had to make the adjustment, just like I’ve been doing all my life.”

The adversity Briscoe has faced in and out of football is something he uses as life lessons with the at-risk youth he counsels in his Boys and Girls Club role. “I try to tell them that sometimes life’s not fair and you have to deal with it. That if you carry a bitter pill it’s going to work against you. That you just have to roll up your sleeves and figure out a way to get it done.”

While Briscoe never lined up behind center again, soon after he left Denver other black QBs followed — Joe Gilliam, Vince Evans, Doug Williams and, as a teammate in Buffalo, James Harris, whom he tutored. All the new faces confronted the same pressures and frustrations Briscoe did earlier. It wasn’t until the late 1980s, when Williams won a Super Bowl with the Redskins and Warren Moon put up prolific numbers with the Houston Oilers, that the black QB stigma died.

Briscoe was not entirely aware of the deep imprint he made until attending a 2001 ceremony in Nashville remembering the late Gilliam. “All the black quarterbacks, both past and present, were there,” said Briscoe, naming everyone from Aaron Brooks (New Orleans Saints) to Dante Culpepper (Minnesota Vikings) to Michael Vick (Atlanta Falcons).

“The young kids came up to me and embraced me and told me, ‘Thank you for setting the tone.’ Now, there’s like 20 black quarterbacks on NFL rosters, and for them to give me kudos for paving the way and going through what I went through hit me. That was probably the first time I realized it was a history-making event. The young kids today know about the problems we faced and absorbed in order for them to get a fair shot and be in the position they are.”

Making the Buffalo roster at a spot he’d never played before proved one of Briscoe’s greatest athletic challenges and accomplishments. He not only became a starter but soon mastered the new position, earning 1970 All-Pro honors in only his second year, catching 57 passes for 1,036 yards and 8 TDs. Then, in an example of bittersweet irony, Saban was named head coach of the moribund Bills in 1972 and promptly traded Briscoe to the powerful Miami Dolphins. The move, unpopular with Bills’ fans, once again allowed Briscoe to intersect with history as he became an integral member of the Dolphins’ perfect 17-0 1972 Super Bowl championship team and the 1973 team that repeated as champs.

Following an injury-plagued ‘74 season, Briscoe became a vagabond — traded four times in the space of one year — something he attributes to his involvement in the 1971 lawsuit he and five other players filed against then-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle, an autocrat protecting owners’ interests, in seeking the kind of free agency and fair market value that defines the game today. Briscoe and his co-complainants won the suit against the so-called Rozelle Rule but within a few years they were all out of the game, labeled troublemakers and malcontents.

His post-football life began promisingly enough. A single broker, he lived the L.A. high life. Slipping into a kind of malaise, he hung with “an unsavory crowd” — partying and doing drugs. His gradual descent into addiction made him a transient, frequenting crack houses in L.A.’s notorious Ho-Stroll district and holding down jobs only long enough to feed his habit. The once strapping man withered away to 135 pounds. His first marriage ended, leaving him estranged from his kids. Ex-teammates like James Harris and Paul Warfield, tried helping, but he was unreachable.

“I strayed away from the person I was and the people that were truly my friends. When I came back here I was trying to run away from my problems,” he said, referring to the mid-’80s, when he lived in Omaha, “and it got worse…and in front of my friends and family. At least back in L.A. I could hide. I saw the pity they had in their eyes but I had no pride left.”

Perhaps his lowest point came when a local bank foreclosed on his Super Bowl rings after he defaulted on a loan, leading the bank to sell them over e-bay. He’s been unable to recover them.

He feels his supreme confidence bordering on arrogance contributed to his addiction. “I never thought drugs could get me,” he said. “I didn’t realize how diabolical and treacherous drug use is. In the end, I overcame it just like I overcame everything else. It took 12 years…but there’s some people that never do.” In the end, he said, he licked drugs after serving a jail term for illegal drug possession and drawing on that iron will of his to overcome and to start anew. He’s made amends with his ex-wife and with his now adult children.

Clean and sober since 1991, Briscoe now shares his odyssey with others as both a cautionary and inspirational tale. Chronicling his story in his book, The First Black Quarterback, was “therapeutic.” An ESPN documentary retraced the dead end streets his addict’s existence led him to, ending with a blow-up of his fingers, bare any rings. Briscoe, who dislikes his life being characterized by an addiction he’s long put behind him, has, after years of trying, gotten clearance from the Dolphins to get duplicate Super Bowl rings made to replace the ones he squandered.

For him, the greatest satisfaction in reclaiming his life comes from seeing how glad friends and family are that the old Marlin is back. “Now, they don’t even have to ask me, ‘Are you OK?’ They know that part of my life is history. They trust me again. That’s the best word I can use to define where I am with my life now. Trust. People trust me and I trust myself.”

Related Articles

- Black like me (cbc.ca)

- Black like me: CFL QB legacy (cbc.ca)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Today’s Exploration: Omaha’s History of Racial Tension (theprideofnebraska.blogspot.com)

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Eric Crouch To Play For UFL’s Omaha Nighthawks, Fulfill Destiny (sbnation.com)

Bob Gibson, the Master of the Mound remains his own man years removed from the diamond (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Omaha’s bevy of black sports legends has only recently begun to get their due here. With the inception of the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame a few years ago, more deserving recognition has been accorded these many standouts from the past, some of whom are legends with a small “l” and some of whom are full-blown legends with a capital “L.” As a journalist I’ve done my part bringing to light the stories of some of these individuals. The following story is about someone who is a Legend by any standard, Bob Gibson. This is the third Gibson story I’ve posted to this blog site, and in some ways it’s my favorite. When you’re reading it, keep in mind it was written and published 13 years ago. The piece appeared in the New Horizons and I’m republishing it here to coincide with the newest crop of inductees in the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame. Gibson was fittingly inducted in that Hall’s inaugural class, as he is arguably the greatest sports legend, bar none, ever to come out of Nebraska.

Bob Gibson, the Master of the Mound remains his own man years removed from the diamond (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Orignally published in the New Horizons

Bob Gibson. Merely mentioning the Hall of Fame pitcher’s name makes veteran big league baseball fans nostalgic for the gritty style of play that characterized his era. An era before arbitration, Astro-Turf, indoor stadiums and the Designated Hitter. Before the brushback was taboo and going the distance a rarity.

No one personified that brand of ball better than Gibson, whose gladiator approach to the game was hewn on the playing fields of Omaha and became the stuff of legend in a spectacular career (1959-1975) with the St. Louis Cardinals. A baseball purist, Gibson disdains changes made to the game that promote more offense. He favors raising the mound and expanding the strike zone. Then again, he’s an ex-pitcher.

Gibson was an iron man among iron men – completing more than half his career starts. The superb all-around athlete, who starred in baseball and basketball at Tech High and Creighton University, fielded his position with great skill, ran the bases well and hit better than many middle infielders. He had a gruff efficiency and gutsy intensity that, combined with his tremendous fastball, wicked slider and expert control, made him a winner.

Even the best hitters never got comfortable facing him. He rarely spoke or showed emotion on the mound and aggressively backed batters off the plate by throwing inside. As a result, a mystique built-up around him that gave him an extra added edge. A mystique that’s stuck ever since.

Now 61, and decades removed from reigning as baseball’s ultimate competitor, premier power pitcher and most intimidating presence, he still possesses a strong, stoic, stubborn bearing that commands respect. One can only imagine what it felt like up to bat with him bearing down on you.

As hard as he was on the field, he could be hell to deal with off it too, particularly with reporters after a loss. This rather shy man has closely, sometimes brusquely, guarded his privacy. The last few years, though, have seen him soften some and open up more. In his 1994 autobiography “Stranger to the Game” he candidly reviewed his life and career.

More recently, he’s promoted the Bob Gibson All-Star Classic – a charitable golf tournament teeing off June 14 at the Quarry Oaks course near Mahoney State Park. Golfers have shelled out big bucks to play a round with Gibson and fellow sports idols Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Sandy Koufax, Whitey Ford, Lou Brock and Oscar Robertson as well as Nebraska’s own Bob Boozer, Ron Boone and Gale Sayers and many others. Proceeds will benefit two causes dear to Gibson – the American Lung Association of Nebraska and BAT – the Baseball Assistance Team.

When Gibson announced the event many were surprised to learn he still resides here. He and his wife Wendy and their son Christopher, 12, live in a spacious home in Bellevue’s Fontenelle Hills.

His return to the public arena comes, appropriately enough, in the 50th anniversary season of the late Jackie Robinson’s breaking of Major League Baseball’s color barrier. Growing up in Omaha’s Logan Fontenelle Housing Projects, Gibson idolized Robinson. “Oh, man, he was a hero,” he told the New Horizons. “When Jackie broke in, I was just a kid. He means even more now than he did then, because I understand more about what he did” and endured. When Gibson was at the peak of his career, he met Robinson at a Washington, D.C. fundraiser, and recalls feeling a deep sense of “respect” for the man who paved the way for him and other African-Americans in professional athletics.

In a recent interview at an Omaha eatery Gibson displayed the same pointedness as his book. On a visit to his home he revealed a charming Midwestern modesty around the recreation room’s museum-quality display of plaques and trophies celebrating his storied baseball feats.

His most cherished prize is the 1968 National League Most Valuable Player Award. “That’s special,” he said. “Winning it was quite an honor because pitchers don’t usually win the MVP. Some pitchers have won it since I did, but I don’t know that a pitcher will ever win it again. There’s been some controversy whether pitchers should be eligible for the MVP or should be limited to the Cy Young.” For his unparalleled dominance in ‘68 – the Year of the Pitcher – he added the Cy Young to the MVP in a season in which he posted 22 wins, 13 shutouts and the lowest ERA (1.12) in modern baseball history. He won the ‘70 Cy Young too.

Despite his accolades, his clutch World Series performances (twice leading the Cardinals to the title) and his gaudy career marks of 251 wins, 56 shutouts and 3,117 strikeouts, he’s been able to leave the game and the glory behind. He said looking back at his playing days is almost like watching movie images of someone else. Of someone he used to be.

“That was another life,” he said. “I am proud of what I’ve done, but I spend very little time thinking about yesteryear. I don’t live in the past that much. That’s just not me. I pretty much live in the present, and, you know, I have a long way to go, hopefully, from this point on.”

Since ending his playing days in ‘75, Gibson’s been a baseball nomad, serving as pitching coach for the New York Mets in ‘81 and for the Atlanta Braves from ‘82 to ‘84, each time under Joe Torre, the current Yankee manager who is a close friend and former Cardinals teammate. He’s also worked as a baseball commentator for ABC and ESPN. After being away from the game awhile, he was brought back by the Cardinals in ‘95 as bullpen coach. Since ‘96 he’s served as a special instructor for the club during spring training, working four to six weeks with its talented young pitching corps, including former Creighton star Alan Benes, who’s credited Gibson with speeding his development.

Who does he like among today’s crop of pitchers? “There’s a lot of guys I like. Randy Johnson. Roger Clemens. The Cardinals have a few good young guys. And of course, Atlanta’s got three of the best.”

Could he have succeeded in today’s game? “I’d like to think so,” he said confidently.

He also performs PR functions for the club. “I go back several times to St. Louis when they have special events. You go up to the owners’ box and you have a couple cocktails and shake hands and be very pleasant…and grit your teeth,” he said. “Not really. Years ago it would have been very tough for me, but now that I’ve been so removed from the game and I’ve got more mellow as I’ve gotten older, the easier the schmoozing becomes.”

His notorious frankness helps explain why he’s not been interested in managing. He admits he would have trouble keeping his cool with reporters second-guessing his every move. “Why should I have to find excuses for something that probably doesn’t need an excuse? I don’t think I could handle that very well I’m afraid. No, I don’t want to be a manager. I think the door would be closed to me anyway because of the way I am – blunt, yes, definitely. I don’t know any other way.”

Still, he added, “You never say never. I said I wasn’t going to coach before too, and I did.” He doesn’t rule out a return to the broadcast booth or to a full-time coaching position, adding: “These are all hypothetical things. Until you’re really offered a job and sit down and discuss it with somebody, you can surmise anything you want. But you never know.”

He feels his outspokenness off the field and fierceness on it cost him opportunities in and out of baseball: “I guess there’s probably some negative things that have happened as a result of that, but that really doesn’t concern me that much.”

He believes he’s been misunderstood by the press, which has often portrayed him as a surly, angry man. “

When I performed, anger had nothing to do with it. I went out there to win. It was strictly business with me. If you’re going to have all these ideas about me being this ogre, then that’s your problem. I don’t think I need to go up and explain everything to you. Now, if you want to bother to sit down and talk with me and find out for yourself, then fine…”

Those close to him do care to set the record straight, though. Rodney Wead, a close friend of 52 years, feels Gibson’s occasional wariness and curtness stem, in part, from an innate reserve.

“He’s shy. And therefore he protects himself by being sometimes abrupt, but it’s only that he’s always so focused,” said Wead, a former Omaha social services director who’s now president and CEO of Grace Hill Neighborhood Services in St. Louis.

Indeed, Gibson attributes much of his pitching success to his fabled powers of concentration, which allowed him “to focus and block out everything else going on around me.” It’s a quality others have noted in him outside sports.

“Mentally, he’s so disciplined,” said Countryside Village owner Larry Myers, a former business partner. “He has this ability to focus on the task at hand and devote his complete energy to that task.”