Archive

Actress Yolonda Ross is a talent to watch

One of my favorite “discoveries” from the past decade is fellow Omaha native Yolonda Ross, a supremely talented actress whose work back here has gone largely unnoticed for some reason. I caught up with her the first time, for the story that follows, not long after her breakthrough starring role in the HBO women’s prison movie Stranger Inside brought her to the attention of the television/film industry and just before Antwone Fisher was released and her small but telling role as Cousin Nadine made an impression. She’s proved a daring artist in her choice of material and is exploring writing-directing opportunities in addition to acting gigs. My story below appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) and a later profile I did on her for that same publication can also be found on this blog.

NOTE: More recently, Yolonda’s had a recurring role as Dana Lyndsey on the acclaimed HBO drama Treme. Another Omaha actor of note, John Beasley, just nabbed a recurring role on the same series. Small world.

Yolonda Ross is a talent to watch

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader

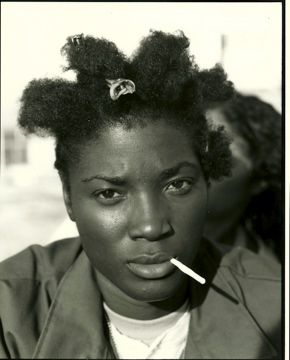

With her sweet-sassy voice, orange-tinged Afro, almond-shaped eyes, real-women-have-curves bod and cool hip-hop vibe, Yolonda Ross gets her groove-on exploring a seemingly boundless creativity.

The Omaha native left town soon after graduating Burke High School in the early 1990s to work in the New York fashion industry before carving out a career on stage and in front of the camera. This rising young film/television actress with a penchant for essaying gritty urban sistas is on the verge of break-out success between her acclaimed star turn in the 2001 HBO women’s prison drama Stranger Inside and supporting performances in two new high-profile films slated for release this winter. Due out first is Antwone Fisher, the directorial debut of Oscar-winner Denzel Washington. Next, is The United States of Leland, a project produced by Oscar-winner Kevin Spacey. She’s now looking to develop a script she wrote into a feature she would also appear in.

Whatever happens with her career, this confident woman of color has an array of artistic flavas to explore. “I like creating in a lot of ways — writing, painting, making clothes, singing, acting,” the New York resident said upon a recent swing-through Omaha to visit family. It was that way even growing-up with her three sisters. “I’ve always been into fashion. I would be up in the middle of the night making things to wear to school the next day. It’s a creative thing to be able to start and finish something and say that you made it. It’s just something I really like to do — that and interior design.” And music. “Me and all my sisters were always musical. I always liked to sing. I didn’t get really serious about it until I was in New York. A roommate who’s a producer had me cut a Billie Holiday cover.” Before long, she said, Ross had her own three-piece band and got offered a Motown demo deal. “I didn’t go for it,” she said. “They were trying to change my jazz into something else.”

New York sustains and energizes Ross. “When you’re in New York you’re always hustling, you’re always doing a variety of things to see which breaks. There’s always stuff happening and you can just literally walk into things,” she said. One gig would lead to another, making her early years there “growing and learning…not really so much struggling.” Prior to 9/11 she lived near the World Trade Center. She was in L.A. when the tragedy occured and took her time moving back. New York is where she feels “at home” again. “I like being on the street with people. I hate driving. I like walking and being a part of it. I’m a downtown person. It works for me.”

When she first went to the Big Apple, she didn’t know a soul there. Undeterred, she stayed to fulfill a long-held vow “to go to New York.” Within a few years there she transitioned from working as a buyer for trendy Soho botiques to modeling (Black Book) to fronting her own band in Greenwich Village gigs to appearing in music videos for the Beastie Boys, L.L. Cool J and Raphfael Saadiq and D’Angelo.

After honing her dramatic skills in classes, she began acting in small theater productions, appearing in recurring roles on Saturday Night Live and daytime shows and getting guest leads in TV series (a cop in New York Undercover, a beleaguered mother in Third Watch). She said she learned more about acting from singing than formal training.

“I’ve taken classes…but it was like being on stage with people you didn’t really like and saying words you didn’t really feel. When I started singing is when I understood that key of emotion and emoting through different characters. Behind everything I do is music. Now, when I do something, it’s not me anymore. I mean, you get a little bit of me with it, but I’m just the conveyor of the writer’s and director’s vision.”

Then along came the part of her young life. On the strength of her TV work, the script for Stranger came her way and after reading it Ross felt the role of Treasure Lee was meant for her.

“I thought it was amazing. I understood it so well. I knew where she was coming from and everything. I was like, I’ve got to get this part. I went in and auditioned. There were a lot of other girls there. I just did my thing and left and I got a call back. I ended up getting a call back three times. The producers flew me out to L.A., where it was like a month of auditioning, and I ended up getting it.”

Written and directed by black-lesbian filmmaker Cheryl Dunye, Stranger takes the conventions of Hollywood prison films and applies a feminist-dyke twist to them, offering a raw depiction of women’s life inside the pen. Ross portrays the troubled Lee, a desperate young woman trying to forge a bond with the mother she never knew, Brownie, a lifer and queenpin behind bars. Her work earned her the 2001 IFP Gotham Award for Breakthrough Actor, a Best Debut Performance nomination from the Independent Spirit Awards and an Outfest Screen Idol Award nomination for Best Performance By an Actress in a Lead Role. In 2001, she was named one of Variety’s “10 Actors to Watch.”

Photo credit: Jack Zeman

While never tackling a role as large or demanding as Treasure before — in one scene she endures a full nude body search and in another is pleasured with oral sex by a fellow inmate — she embraced the challenge, fully aware of just how juicy a part it was.

“To be able to do Treasure and to do everything that was in that script — I welcomed it — I really did — because I knew I had this chance that a lot of people don’t get and I wasn’t about to mess it up.”

Making the part resonate for Ross was its reality.

“Treasure, to me, was like a real person, not just a movie person. With a lot of scripts you read the characters don’t really evolve. The thing I like about Stranger is the characters aren’t one-dimensional. They’re good, strong female characters that let you see other sides.”

She said playing a profane, violent, overtly sexual woman was liberating. “The freedom to be able to get things out through her and to stretch through her was something I looked forward to. As Yolonda, I’m not going to act the way Treasure would — not that I don’t have it inside me — but I need to get those things out and use them and caress them and fine-tune them.”

Researching the role brought Ross to some California women’s prisons, where she met inmates. The film was shot at the “eerie” abandoned Cybil Brand Prison. Rehearsals lasted four weeks, which she welcomed. “You see, I’m not one of those ad-lib people. I like to know exactly what I’m doing. Sometimes, in rehearsal, little things come up and you find things. I feel once you hit it, you should leave it alone until you shoot it.”

She said filming was such a blast “I didn’t want it to end.” As for the finished film, she feels Dunye captured the truth without compromise. “It wasn’t glossed up. It didn’t get sliced up. All the emotions came through. I thought it was a great job and I’m proud of it.” The only downside to making Treasure her first lead, Ross said, is that without much of a track record behind her casting directors “didn’t know how much of it was acting and how much of it was me.”

Even though it meant playing another “bad girl,” Ross jumped at the chance to be in Fisher. The film is based on the best-selling book, The Antwone Fisher Story, in which Fisher, who adapted his own book to the screen, details his real life odyssey of childhood abandonment, foster care abuse, adult rage and — with the help of a good woman and a psychiatrist (played by Washington) — overcoming trauma to emerge a successful husband, father and artist.

Ross portrays Cousin Nadine, a foster family abuser in Fisher’s life. When she read the script, she said she doubted “if I can do this. But the negative things my character does you don’t actually see, and so once I figured that out then it was all right. I sent in my audition on tape. I was out in L.A. to do a 24 and one day I get a call on Melrose, and I’m trying to hold the reception. I’m like (to passersby), ‘OK, wait, I’ve got Denzel on the phone — walk around me. I’m not moving. I’m not going to lose this one.’ He called to say he loved it (her audition),” hiring her on the spot. “Oh, man, that was crazy.” The film was largely shot in Cleveland, where the events depicted actually took place.

Photo by Christopher Logan-

On working with Washington, she said, “He’s so focused…He knew what he wanted. He had his vision and he just did it.” With no rehearsal this time, she discovered the character of Nadine on the set. “We just did the scenes and did ‘em different ways and he used what he wanted.” Of Fisher, she said, “He is the sweetest man. Soft-spoken, low-key. His family is beautiful.” She avoided reading his book before filming “because I didn’t want to try to be exactly something that he wrote. I wanted to come to it with what I have. The crazy thing was, after reading it, my interpretation was just like the character.”

The film, which follows Fisher up to his being reunited with his biological family, is ultimately an inspirational story. “Out of what he endured in his life…all this positive has come out of it,” Ross said. She likes how the film doesn’t sensationalize the events it dramatizes but rather shows them as part of a whole. “It isn’t like a Hollywood movie even though Fox Searchlight did it. It’s like how life is. How a lot of times not much is happening but then some craziness will happen and then, like, OK, you’re back to this place.” The film, starring newcomer Derek Luke, features unknowns, which she feels works to its advantage. “Because you’re not having stars shadow the story, the story is the star. It just works beautifully.”

Besides a one-act play she’s preparing to appear in in New York, Ross awaits her next acting job. Hardly idle, she’s busy schmoozing-up a production deal for her script, which she describes as “a slice of life set in New York” dealing with the romantic entanglements of two couples.

“It’s one of those things where you’ve been with somebody for a while and somebody just comes out of nowhere and blows your mind. Is it real? Is it not? Do you jump and go off with this person or do you stay with your steady in a not so happy but safe relationship?”

She wrote it because “there just aren’t a lot of great parts out there for black women. I mean, you’re the crack head or the welfare mom or the girlfriend. It’s like you can never just stand alone and be a character. So, if there’s something I want to do and I can write it, then I might as well do that. Why wait?”

In United States, premiering at Sundance in January, Ross plays the girlfriend of Don Cheadle in a story examining the impact a death has on a community. Her part was added after principal photography wrapped. She also appears this fall on PBS in an American Film Institute short, The Taste of Dirt. Meanwhile, she’s campaigning for the role of jazz singing legend Billie Holiday. “There’s an amazing script out there I really want. It’s not at the point where there’s anybody behind it, but I’m trying to make sure I’m more than in the running when it comes to that.”

So, how does a young woman from Omaha stay real in the spotlight? “My sisters. My sisters keep me real. They won’t go run and do stuff for me. It’s like, ‘No, do it yourself.’” What’s important to her? “My family — we’re really close. My health. Paying attention to things around me and appreciating them. I’m very much an earthy kind of person.” Still, as her marquee value rises, Ross has her eyes fixed on the perks fame can bring and, for now anyway, forgoes thoughts of long term romantic attachments, saying unabashedly, “There’s things that I want, and I need to get them, and I can’t let things get in the way of that. I’m so focused on working.”

What does the 20-something crave? “A place of my own in Manhattan. A house in upstate New York. To be settled…to be able to have a little bit under my belt. I’d like to be producing movies that I would be in.”

If Fisher nets the same enthusiasm it did in September at the Toronto Film Festival, where Ross said it got a standing ovation, then hers may soon be a household name. “Exactly,” she said, delighted at the notion of being THE new one-name soul sista. “Not Diana, not Halle…Yolonda. Mmmm, hmmm. We’ll see.” Go, girl, go.

Related articles

- Yolonda Ross Takes It to the Limit (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Kevyn Morrow’s Homecoming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Life is a Cabaret, the Anne Marie Kenny Story: From Omaha to Paris to Prague and Back to Omaha, with Love (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Daring actress Yolonda Ross takes it to the limit

Another example of a talented creative artist from Omaha is Yolonda Ross, a superb actress who left her hometown years ago for New York City, and she’s carved out a very nice career in film and television. The following profile for The Reader (www.thereader.com) gives a good sense for this adventurous actress, who also writes and directs. This story appeared in advance of her role in the controversial film Shortbus, one of my provocative projects she’s participated in. I am posting other pieces I’ve done on Yolonda as well.

NOTE: More recently, Yolonda’s had a recurring role as Dana Lyndsey on the acclaimed HBO drama Treme. Another Omaha actor of note, John Beasley, just nabbed a recurring role on the same series. Small world.

Some of the many faces and looks of Yolonda Ross:

Daring actress Yolonda Ross takes it to the limit

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Gabrielle Union gets all the pub, but another film/television actress from Omaha, the righteous Yolonda Ross, consistently does edgy material far afield from Bad Boys II and The Honeymooners. Ross has played everything from a wannabe gangsta desperate for love to a string of lesbian characters to a child molester to a porn actress. She’s worked with everyone from Woody Allen (Celebrity) to Denzel Washington (Antwone Fisher) to Don Cheadle (The United States of Leland) to Vanessa Williams (Dense and Allergic to Nuts).

Last fall, she worked on a Leonardo DiCaprio-produced film, The Gardener of Eden, and has been in discussions with such A-list artists as Cheadle for other parts. But it’s a project she wrapped last summer, Shortbus, that should grab her some attention. The notorious new feature by John Cameron Mitchell (Hedwig and the Angry Inch), a maker of queer cinema, deals with transient artists looking to connect through sex in the malaise of a post-9/11 Manhattan languishing from ever-present anxiety, commerce, inflation and exhibitionism.

Whether Shortbus ever makes it to Omaha is anyone’s guess. Most of Ross’s film work, which includes several shorts, doesn’t make it here. An exception is Dani and Alice, a 2005 short directed by Roberta Marie Munroe that’s screening at the Omaha Film Festival. The film deals with the rarely discussed problem of woman-on-woman partner abuse. Ross plays the femme victim Alice to butch lover Dani in an abusive relationship in its last hours. Dani and Alice shows March 25 at the Joslyn Art Museum’s Abbott Lecture Hall in the fest’s 9 p.m. short film block and Ross plans to attend and participate in an after-show Q & A. For details, check the event website at www.omahafilmfestival.org.

Difficult subjects are the Ross metier, which keeps her work from being widely seen. Her Shortbus director, John Cameron Mitchell, had trouble financing that pic because of his insistence on lensing non-simulated sex scenes.

“Yeah, that’s true, the not-simulated part,” Ross said. “That’s why it’s taken him so long to get money for the movie. People were scared to put money into it.”

Ross was originally put off by the idea of “doing it” on screen and perhaps jeopardizing her career by blurring the line between adult and mainstream cinema. Then, she changed her mind, and was even prepared to partner up again with an old flame for some celluloid enflagrante.

“At first, I was like, I’ll work on it, but I won’t do the sex part. Then, a year later, when John still didn’t have money for it I told him me and my ex-boyfriend would do it — because he needed couples. At that point I was like, If Chloe Sevigny could suck off Vincent Gallo (in The Brown Bunny), then I’m sure I could do it with my ex in a movie. Right?! I said I would do that based on my complete faith that John knew what he was doing and would do something amazing with it, and not use it in a disgraceful way.” As things turned out, Ross didn’t have to get down and dirty for the sake of her art. “Everything turned out cool. The actual couples are still in it. But when somebody fell out of another part, I was re-cast in a role that does not require me to have sex on camera,” she said.

In a film full of non-actors, she plays opposite JD (Samson) of Le Tigre and Suk Chin of Canadian News. She’s not telling who does what on screen. “Dude, you’ll have to watch the movie to know who does and who doesn’t have sex,” she said, laughing.

In the film, she’s the lesbian rocker, Faustus. She attends a women’s support group whose members talk through the politics and emotions of being gay in a straight world. Shortbus is the name of the fictional salon where the insecurities and idiosyncrasies of the characters, including Faustus, intersect. Some go for readings or performances. Others, for therapy. Still others, to engage in public sex. The salon culture portrayed in the film, where sex is a ritualistic and nihilistic acting out mechanism, is based on actual Manhattan salons.

Mitchell and Ross had wanted to collaborate for some time and the two actually hooked up last winter for a Bright Eyes video he directed and she appeared in.

“It’s really a nice thing working with John. He’s so good with people, whether they’re actors or non-actors. He’s great at bringing out the most in them,” she said. “He’s really good at making people feel confident and at ease, while staying on track with what he wants. I think he’s ridiculously talented.”

Ross follows her own clear vision in trying to elevate her career to the next level. She’s well aware, however, of Hollywood’s feckless ways. It’s why she’s taking matters in her own hands and pitching scripts she’s penned in the hope one sells and provides her with a tailor-made part. One of those scripts is serving as her directorial debut, for the comedy short Safe Sex she plans shooting. The story explores how sexual preferences, once exposed, tend to define people.

“Sex fascinates me. It makes people do really stupid things and act in ways they probably never do otherwise. It’s about a lot of mind stuff and what we see as wrong with sex. People have their fetishes or what have you, but you can’t really judge a person by what they get off to. Different things turn different people on.”

Bold themes and choices mark her work. In her best known role, as lesbian inmate Treasure Lee in Cheryl Dunye’s 2001 HBO original film, Stranger Inside, she endures the humiliation of a strip search early on and, in a later love scene, enjoys being pleasured by an inmate going down on her off-camera. In the comic fable Hung, she’s among several gay women to grow a penis. Each owner of the new appendage has her own ideas what to do with it.

In the feature Slippery Slope, pegged for a fall release, she’s a porn star named Ginger who initially struggles adjusting to the higher expectations of a legit director slumming in the world of skin flicks. “Ginger’s been in the business a little while,” Ross said of her character. “She’s a bit set in her ways. She kind of only knows one way to act. She resists learning something new and then she kind of embraces it. She gets into it, actually — the idea of making better pictures. And she starts making her own pictures. It’s nice that she’s not a one note character.”

With Shortbus, Ross once again pushes the envelope as one in a gallery of exotics. Exposing herself emotionally and physically in a part doesn’t intimidate her.

“I have no problem with being a taboo character or doing taboo things or anything like that,” she said. “As long as I can physically do them, I’m going to get up there and do it. I want you to forget it’s me. I want you to be lost in that character.”

Because Ross wants even fringe characters grounded in reality, she underplays what could be camp or superficial. “I like working subtly. The stuff that gets me is what happens behind the scenes and what people are really going through. Good, strong female characters that are real people,” she said. Not big on research, she relies instead on instinct and script preparation. “Know what you need to know, and then Iet the acting take over. I think what you need to be dead-on with are the emotions. That’s what makes me work better. If I know what my character thinks or feels in a situation, then that’s what makes me react in the right way.”

Her expressing the right emotion of a line is akin to when she sings jazz or blues, something she does purely for pleasure these days, but that she once did professionally in New York clubs. Music, she said, opened her up to acting, and she still uses it today to find the right notes and beats for her characters.

“When I started singing is when I understood the key of emotion. With every major character I’ve done there’s been music behind each one. From singing, I know there’s certain notes I hit or tones I make that, when I hear them, make me cry or make me feel some other way. Music can change my whole body and how I carry myself. If I’m listening to Ella, I’m not going to walk the same way I do as when I’m listening to Ray Charles. When I was doing Stranger Inside, there was a Marvin Gaye song, Distant Lover, in my head. OnShortbus, it was The Tindersticks’ Trouble Every Day soundtrack. Music keeps me relaxed or tense or whatever I need to be.”

In her early-30s, Ross is at a place in her career where she does a nice balance of little and big screen gigs capitalizing on her street smart persona, which finds her getting cast as beleaguered mothers, strung-out junkies, intense cops and bohemian types in episodic TV. But anyone who’s seen her work, such as her riveting turn in Stranger, knows she can play a full palette of colors and be everything from a hard-core case to a sweet, neurotic, vulnerable woman-child.

There’s a sense if she can just land one juicy part, she’ll be a major presence. Even if that doesn’t happen, she keeps adding to an already impressive body of work. Among her TV credits, are sketch comedy on Saturday Night Live, and high drama guest shots on 24, ER and Third Watch.

Part of why Ross hasn’t broken out big time in front of the camera, despite some heady props for Stranger and Fisher, has to do with the unsympathetic or peripheral roles she gets and the small indie projects she plays them in. One could argue that until now, while Gabrielle Union’s enjoyed the more successful commercial career, Ross’s has been more interesting. To be fair, though, Union has three films in the can that finally go beyond purely popcorn storylines and that for once hold out the promise of stretching her dramatic abilities.

But the point is Ross, an African-American contemporary of Union’s, has explored provocative subject matter for some time now without a fat pay-off. Union and Ross, who incidentally are fans of each other’s work, offer an interesting comparison. Each has defied the odds to carve out a nice career on screen. A key difference is perception. Union’s classic, wholesome beauty, with her smooth, soft features, put her up for positive roles and land her well-placed Neutrogena TV spots and endless glamour photo spreads in national mags. She comes across as sexy, brainy, full of attitude, but in purely non-threatening terms — as the love interest, friend or rival — and in widely accessible pictures, too.

By contrast, Ross’s unconventional but no less intriguing radiance has harder features, leaving her out of luck when it comes to girl-next-door or, for that matter, seductress roles. Spend any time with Ross, and it’s obvious she can play it all. She even does her share of glam, including a recent Bicardi Big Apple event in which she modeled an Escada gown. She’s a regular at New York premieres and other photo-op bashes. But in a town where they only know you by, What have you done lately? — perception, not reality, rules. Her performance in Stranger, a film/portrayal that became a cause celeb at feminist/lesbian festivals, was so on the mark, she’s been typecast ever since as a low down sista. In fact, she’s in high demand by women directors, whom she often works with.

Women confront stereotypes in the business, but Ross said black women must overcome even more. She said if you look closely, you’ll see that actresses with darker skin tones play “bad” while those with lighter skin shadings play “good.”

“Darker women are the cops, the crack heads, the hard asses. The darker the skin, the harder you’re going to be, the tougher you’re going to be. It’s very difficult for me to be seen as the cute girl next door or the nice mother or the love interest. I mean, it’s the craziest thing. Gabrielle’s about the same color I am, but she’s somewhat busted through,” said Ross, who surmises Union’s straight hair translates into less urban or ghetto in the minds’ of casting directors. “It’s about looks and name and face recognition. That’s what sells. Halle Berry can make bad movie after bad movie and have a Revlon contract. But why is it Angela Bassett isn’t working?”

Good women’s roles are hard to find, period, and even harder if you’re black. “Most scripts I read aren’t that good,” she said. “The characters don’t evolve.” Then there’s color-conscious casting that denies Ross, and even Union, a chance at roles deemed white or, God forbid, being part of an interracial romantic pairing.

That’s why Ross, who’s developed a working friendship with famed screenwriter Joan Tewksbury (Nashville) — “my second mother” — and Dani and Alice co-star Guinivere Turner, is trying to make something happen with projects she’s written alone or in collaboration. She despairs sometimes how fickle and slow the business is. “It drives me crazy. But I have to remember all the stories about other people where it took like 10-15 years to get something done. I know that the stories I have will have an affect on people. So, I keep that in mind.”

Until something breaks there, she’s waiting for start dates on two more features she’s cast in. Pearl City is a modern-day film noir set in Hawaii that lets Ross play sly as one of many potential suspects in a homicide investigation. Then there’s a new religious-themed film by Boaz Yakim (A Price Above Rubies).

Meanwhile, slated for a spring release is The Gardener of Eden. Directed by Kevin Connolly, the film co-stars Ross as one of many people crossing paths with a man so addicted to the props that come with being hailed a hero that he manipulates events to rescue others. The film also features Lukas Haas and Giovanni Ribisi.

Whatever comes next, Ross will take it to the limit.

Related articles

- [Movies] Shortbus (2006) (geeky-guide.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Yolonda Ross is a Talent to Watch (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Film Review: Shortbus (thenakedtruth69.wordpress.com)

Canceled FX boxing show, “Lights Out,” may still springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s career

As noted here before, storytellers are drawn to boxing for the rich drama and conflict inherent in the sport. So when I learned that Holt McCallany, star of the new FX series, Lights Out, spent a formative part of his youth in my hometown of Omaha and that his mother is singer Julie Wilson, a native Omahan, I naturally went after an interview with the actor, and setting it up proved unusually easy. In wake of the series’ cancellation, I know why. Producers and publicists were desperate to get the show all the good press they could but even though the show was almost universally praised by small and big media alike it never found enough of an audience to satisfy advertisers or the network. Because I enjoy charting the careers of Nebraskans who make their mark in the arts, particularly in cinema, I expect I will be writing more about McCallanay, who is a great interview, in the future. In addition to his television work, which between episodic dramas and made-for-TV movies is extensive, he has a fine tack record in features as well. I am also planning a piece on his mother, the noted cabaret artist Julie Wilson.

Canceled FX boxing show, “Lights Out,” may still springboard Omahan Holt McCallany’s career

©By Leo Adam Biga

As published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Storytellers drawn to boxing’s inherent drama invariably find redemption at its soul and conflict as its heart.

Ring tales are on a roll thanks to Mark Wahlberg’s Oscar-winning film The Fighter and FX’s series, “Lights Out,” (the series finale airs next Tuesday, April 5 at 9 p.m.). Although FX recently announced it has decided not to renew the show for a second season, the show received favorable reviews from critics while generating more than usual interest locally, as it stars former home boy Holt McCallany in the breakout role of the fictitious Patrick “Lights” Leary, an ex-heavyweight champ attempting a comeback.

McCallany grew up in Omaha, the eldest of two rambunctious sons of Omaha native and legendary New York musical theater actress and cabaret singer Julie Wilson, and the late Irish American actor/producer Michael McAloney.

Like his hard knocks character, McCallany was truant and quick to fight. He was expelled from Creighton Prep. He says most of the “unsavory crew” he ran with outside school “wound up in jail.” At 14, he ran away from home — flush with the winnings from a poker game — to try to make it as an actor in Los Angeles.

“I was a very rebellious and a very ambitious kid,” he says.

In the spirit of second chances linking real life to fiction, he got some tough love at a boarding school in Ireland and returned to graduate from Prep in 1981, a year behind Alexander Payne, whom he hopes to work with in the future. McCallany, who’s returning to Omaha for his class’s 30th reunion in July, appreciates the school not giving up on him.

“I got kicked out but they eventually took me back, and they didn’t have to do that. Near my graduation I said to one of the priests, ‘Why did you guys take me back?’ and he said, ‘Because we believe in your talent, Holt. We see a lot of boys come through here and we believe you can be one of the first millionaires out of your class and a good alumnus.’ When you’re a kid you take that stuff to heart and it kind of stays with you, and if you believe it, other people will believe it about you, too.”

Tragedy struck when his troubled kid brother died at 26 in search of another fix. It’s a path Holt might have taken if not for finding his passion in acting.

“I felt like I had a calling. My brother didn’t have that, and my brother’s dead now, and I can tell you a lot of the pain and suffering he went through is related to this subject. When you don’t know what it is you want to be and you’re lost and you’re floundering and you’re going from job to job and kicking around and nothing really works out, it’s a very dispiriting place to be. It can lead to substance abuse and a lot of negative things.”

In the show, Leary’s a devoted husband and father trying to rise above boxing’s dirty compromises, but he and his younger brother get sullied in the process.

McCallany, who infuses Lights with his own mix of macho and sensitivity, is the proverbial “overnight sensation.” He’s spent 25 years as a journeyman working actor in film (Three Kings) and TV (Law & Order), mostly as a supporting player, all the while honing his craft — preparing for when opportunity knocked.

Everyone from co-star Stacy Keach, as his trainer-father, to series executive producer Warren Leight to McCallany himself says this is a part he was born to play. Why? Start with his passion for The Sweet Science.

“Boxing was my first love, and way back when I was a teenage boy in Omaha. My brother won the Golden Gloves. We had an explosive sort of relationship, he and I. We would often get into fistfights and all of a sudden he was getting really good.”

As for himself, McCallany’s a gym rat. He’s logged countless hours sparring — “sometimes those turn into real wars” — and training with pros. He appeared in the boxing pics Fight Club and Tyson. He’s steeped in boxing lore. He brought in his friend, world-class trainer Teddy Atlas, as technical adviser on Lights Out.

The pains taken to get things right have won the show high praise. The only critics who matter to McCallany are pugilists. “The response from the boxing community has been really positive,” he says.

“There are a lot of similarities I find between boxing and acting,” he says. “In the theater the curtain goes up at 8 and the audience is in their seats and you’ve got to come out and give a performance, and it’s similar in boxing — there’s an appointed day and appointed time when you know people are going to be there ringside and it’s time for you to come out and perform.”

In both arenas, nerves must be harnessed.

“The anxiety is your friend,” he says. “That’s what’s going to ensure you’re going to do what you’re trained to do and, as Ernest Hemingway said, ‘remain graceful under pressure,’ which is really what it’s about.”

As much as he admires great boxing films he says “Lights Out” is not constrained by the limits of biography or a two-hour framework.

“We have all of this time to explore in rich detail a boxer’s life and his relationships and his psychology,” he says. “With this character the writers and I have the freedom to really create and really see where this journey is going to take us, and that’s very exciting. I can’t tell you exactly what’s going to happen in season two because I’m not sure, and I promise you they’re not sure either. That’s what’s different.”

While they’ll be no second season now, McCallany’s up for a part in the nextBatman installment and has a script in play with

Related Articles

- Holt McCallany and Warren Leight Interview LIGHTS OUT (collider.com)

- Five Reasons to Watch Lights Out (seattlepi.com)

- ‘Lights Out’: A Total Knockout Of A Boxing Drama (npr.org)

- FX’s ‘Lights Out’ has more than punches to throw at viewers (latimesblogs.latimes.com)

- So long, “Lights Out” — you coulda been a contender (salon.com)

- Life is a Cabaret, the Anne Marie Kenny Story: From Omaha to Paris to Prague and Back to Omaha, with Love (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Home Girl Karrin Allyson Gets Her Jazz Thing On (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Home Boy Nicholas D’Agosto Makes Good on the Start ‘Election’ Gave Him; Nails Small But Showy Part in New Indie Flick ‘Dirty Girl’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Charles Fairbanks, aka the One-Eyed Cat, makes Lucha Libre a way of life and a favorite film subject

When I read about filmmaker Charles Fairbanks for the first time last year I was immediately taken by his story: how a rural Nebraska student-athlete turned artist become enamored with and immersed in the world of Mexican professional wrestling known as Lucha Libre, which he’s made the subject of some of his short films. Then when I delved further into his story, by exploring his website and watching some of his work, I knew I had to write about him. We met last summer, when his disarmingly sweet personality and thoughtful responses made me immediately like him. The following story I wrote about Fairbanks and his work appeared just before this year’s Omaha Film Festival, where one of his Lucha Libre films, Irma, was shown. Fairbanks is a serious artist whose work may or may not ever find a wide audience but is certainly deserving of it. I plan to follow his career and to see much more of his work as time goes by.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In the space of a few years Charles Fairbanks has gone from conventional prep and collegiate wrestler to one of the few gringo performers of Lucha Libre, Mexico’s equivalent of WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment).

Amid a world of masked figures with exotic alter egos, Fairbanks performs as the One-Eyed Cat. It’s not what you’d expect from this cerebral, soft-spoken, fair-skinned rural Nebraska native. Then again, Fairbanks is an adventurous artist and art educator, which explains why he’s devoted much of the last nine years to Lucha Libre’s high-flying acrobatics and soap opera melodramatics.

Fairbanks, whose pretty boy face and chiseled body are in stark contrast to Jack Black in Nacho Libre, is a photographer and short filmmaker who loves wrestling. Naturally, then, he combines his passions as self-expression. He’s gone so far as affixing a video camera to his mask to record the action.

“Oh, I look silly,” he says of his third eye. “Other wrestlers laugh out loud but they’re always very welcoming. I make sure to establish a relationship before I walk in with a camera on my head.”

His documentary short Irma, an Omaha Film Festival selection, lyrically profiles Irma Gonzalez, a hobbled but still strong, proud former wrestling superstar and singer-songwriter who befriended him at Bull’s Gym on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Last fall Irma won the Best Short prize at the Coopenhagen International Documentary Film Festival. It’s shown at festivals worldwide, as have other works by Fairbanks, some of which, like Pioneers, have nothing to do with wrestling.

Intense curiosity brought him to Mexico in the first place. Oddly, he’d just abandoned organized wrestling. He was a state champion grappler at Lexington (Neb.) High, where his artistic side also flourished. His mat talent and academic promise earned a scholarship to Stanford University, where he wrestled two years before quitting the team.

He was touring Mexico on a rite-of-passage mission of self-discovery and enlightenment when he saw his first Lucha Libre match. He soon started shooting and practicing. He made still images that first trip and has since used video to capture stories.

“I just fell in love with this spectacle,” he says.

Bull’s Gym, located on an upper floor of a hilltop building, is his main dojo, sanctuary and set. It overlooks a cinematic backdrop.

“There’s something powerful for me in looking out at the miles of humble cinderblock housing spread out and up the ridges around Mexico City,” he says. “That view is very beautiful. With all the pollution the sunsets are very colorful. The airport is nearby and so you see the airplanes taking off.

“For me all of this magnifies and modulates the gym’s energy, which is really pretty fervent. There’s often boxing and wrestling going on at the same time in the same room. With all the activity, the ambient noise is really a roar.”

Lucha Libre has a near mystical hold on him now but he admits he originally regarded it as a lovely though bastard version of the wrestling he grew up with.

“At the time, as most competitive wrestlers in the U.S., I denied the connection,” he says. “I said, This is totally different. Now I’ve gotten to the point where I can accept the real links between competitive wrestling and show wrestling.”

Fairbanks, a Stanford art grad with a master of fine arts degree from the University of Michigan, takes an analytical view of these kindred martial arts.

“There is a lot of overlap but at the same time I think they have very different philosophies embedded in them.”

Asking if Lucha Libre is fake misses the point. The visceral, in-the-moment experience is the only reality that matters.

“In my experience of Lucha Libre the matches themselves are not staged — you don’t know who’s going to win. You still maybe want to win, but it’s not just up to you,” he says. “You can’t just go for a pin. You really have to try to entertain. It’s very much like a dance. There’s a certain repertoire of moves my opponent and I know how to do together, and if I start to do one move you recognize this move and you actually respond in a certain way to help me do it more spectacularly.

“And then there are variations, where you’re doing something defensive that’s changing me, so it’s not my move anymore. As we go through this back and forth we establish these sort of rhythms.”

The unfolding dance, he says, is also “an improvised drama” marked by “waves of tension” and “a building of energies. One wrestler is dominating but then the tides turn and the other wrestler comes back. It’s not something scripted but you feel your way through.” The improvisation, he adds, extends to the referee, who “plays his part,” and to the crowd, “who play their part.”

Reared in the no-frills tradition of amateur wrestling, he says “it’s been really hard to learn this completely different way of thinking or feeling reality. I’m the first to say I haven’t mastered Lucha Libre. I’m not trying to make it big as a wrestler in Mexico. I’m trying to learn about wrestling.” He’s also a practitioner of Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

He’s learned about Lucha Libre’s “built-in codes of honor” and “certain ways people present themselves publicly or don’t.” The wrestlers aren’t supposed to reveal their identity outside the ring. He’s made himself an exception.

“I feel OK transgressing this because I’m already marked as Other.”

Irma Gonzalez

In his Flexing Muscles some native wrestlers half-kiddingly harangue this outsider. “It’s very important to me they’re calling me gringo and saying, ‘Go back to your damned country,” he says, as it makes overt his interloper status. As deep as he’s tasted Mexican culture he knows he remains a visitor and observer.

“I’m really conscious of my differences from most of the people there in terms of nationality and economics,” he says.

He’s acutely aware too of his privileged “ability to come in and do this and then leave and go back to the States and make art out of this experience,” adding, “With my movies in a certain sense I try to build in the story of my being there and my relationship to the subjects.” He’s struck by how generous his subjects are in opening their lives and homes to him even as they struggle getting by.

Stranger or not, he engages the culture head-on.

“I do try to immerse myself very much in that world I’m living in, but without losing who I am. I never try to pretend to be Mexican. I try to get as close as I can and I try to understand, but from my point of view.”

Despite the obvious differences between Fairbanks and his fellow performers, he feels a reciprocal kinship, adding, “there’s a certain kind of camaraderie I feel with wrestlers anywhere.” Wherever he’s traveled, including Europe and Asia, he’s wrestled.

Fairbanks has seen much of Mexico but is largely centered in Mexico City and Chiapas, where he teaches filmmaking. He says, “I love to stay with families, I love to have local people to learn from and to interact with.”

Moments of zen-like meditation and magic realism lend his work poetic sensibility and cultural sensitivity. Irma‘s tough title character sings a ranchero in the ring while her circus performer granddaughters romp. In Pioneers Fairbanks lays hands over his father’s ailing back in a shamanistic healing ceremony. Enigmatic stuff.

“I like to make movies that invite more questions,” says Fairbanks, who participated in Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School and cut his chops working with veteran filmmakers in Brussels, Belgium. “I like to have the films be a process of discovery for the viewers — to not tell the viewers how to see this world — but also a sense of discovery for me as I’m making the films.”

Authenticity is his goal.

“For me it’s important I’m making movies in Mexico that convey a part of experience not covered by our news media.”

As for the future, he says, “I have very specific stories I want to tell in Mexico and in other countries, some related to wrestling, other types of wrestling, some not at all related to wrestling.”

Irma‘s Omaha Film Festival screening is 6 p.m. on March 3 at the Great Escape Theatre as part of the Striking a Chord block of Nebraska documentary shorts.

Related articles

- WWE News: Has Mexican Lucha Libre Star Averno Signed with the WWE? (bleacherreport.com)

- Lucha Future Mexican wrestlers storm The Roundhouse (vidalondon.net)

- Behind the mask – lucha libre wrestlers tap into Kitsap (pnwlocalnews.com)

- Offbeat Wrestlers Celebrate Cinco De Mayo ‘Lucha Libre’ Style (weirdnews.aol.com)

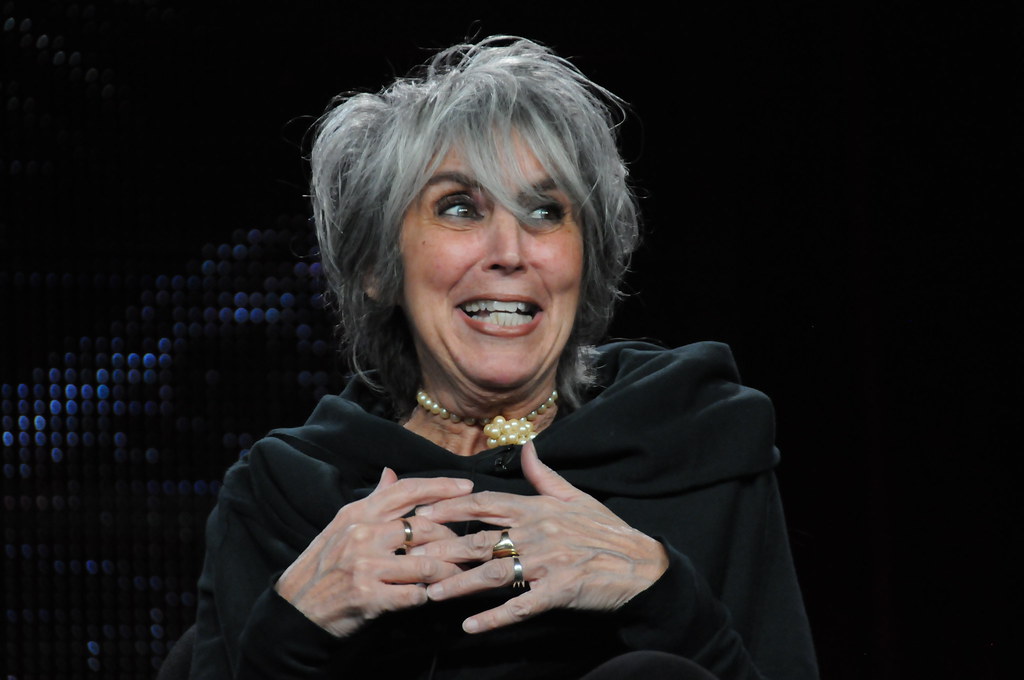

Long Live the Dude: Gail Levin Chronicles Jeff Bridges for “American Masters”

My friend and sometime subject, documentary filmmaker Gail Levin, has a new work premiering Jan. 12 on PBS for American Masters — a profile of Oscar-winning actor Jeff Bridges. Her film, Jeff Bridges: The Dude Abides, comes just short of a year since the star accepted the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Bad Blake in Crazy Heart. He may well be in contention for the award again on the strength of his performance in the Coen brothers‘ remake of True Grit. I interviewed Levin by phone during a break from her editing of the film in New York, where she lives. I haven’s seen the film, except for a brief excerpt you can find yourself on the American Masters web site. But I know her work very well, and she’s handled similar assignments profiling acting legends quite well. I expect the same with this project. Levin is an Emmy Award-winning filmmaker whose work has appeared before on both American Masters and Great Performances. On this blog site you can find some of my earlier stories about Gail and her films The Tall Ship Lindo, Making the Misfits, James Dean, Sense Memories, and Marilyn Monroe – Still Life. My story on Levin and her Jeff Bridges film is published in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

NOTE: Now that I have seen Levin’s film — on the rebound in a late night reprise screening — I can now say that it one of the better profiles of an actor I have ever seen. Even though Levin expressed frustration to me at not getting in as deep or close with Bridges as she would have liked, I feel like I now have an authentic appreciation for who he is and how he conducts himself in his life and in his art. As I mentioned to Levin when we spoke about the project, I have always felt that Bridges was hugely unappreciated and I think her film will be part of an ongoing reevaluation of his work and his career that will recognize him as one of the masters of his craft.

Long Live the Dude: Gail Levin Chronicles Jeff Bridges for “American Masters”

©by Leo Adam Biga

Author of Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film

Published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Omaha native and Emmy Award-winning documentarian Gail Levin profiles actor Jeff Bridges in a new film kicking off the 25th season of American Masters, a series produced for PBS by New York Public Media THIRTEEN in association with WNET.

Jeff Bridges: The Dude Abides premieres Jan. 12, showing locally on NET at 9 p.m.

Levin, an Omaha Central High graduate long based in Manhattan, says the project has been on quick turnaround to parlay the heat surrounding Bridges. A year ago he won the Best Actor Oscar for his performance as country musician Bad Blake in Crazy Heart. Oddsmakers predict a nomination for his rendition of lawman Rooster Cogburn in the Coen brothers’ True Grit.

“We’re really trying to take advantage of all the energy and buzz of everything that’s going on with him,” says Levin (Making the Misfits, James Dean: Sense Memories).

Her film reveals Bridges as a multi-faceted creative. In addition to acting he’s a musician. He performs with his band The Abiders. He’s also a photographer, painter, potter, and vintner. Performing his own music in Crazy Heart surprised many, but it was simply an extension of what he’s always done.

“His great love is music, and it has been all throughout his life,” she says. “He’s now really playing a lot of music, doing gigs. We’ve got a lot of footage of him. We shot at this funny little place he played in Niagara Falls.”

She also captured him at a Zen symposium.

“I don’t know that he would call himself a Buddhist, but he’s certainly in that ether at the moment. He’s very involved with a group called Zen Peacemakers.”

Levin was struck by a passage Bridges wrote in the intro to his book Pictures, a sampling of images the actor takes on movie sets and gifts as photo albums to cast and crew. In describing why he prefers the panoramic Widelux still camera, he offers a key to his creative method:

“…it has an arbitrariness to it, a capricious quality. I like that. It’s something I aspire to in all my work — a lack of preciousness that makes things more human and honest, a willingness to receive what’s there in the moment, and to let go of the result. Getting out of the way seems to be one of the main tasks for me as an artist.”

For Levin, the insight helps explain what makes Bridges a durable star 40 years since his feature breakthrough in The Last Picture Show.

In her interviews with him, his family and colleagues Levin found he’s more complex than his public Everyman-Next-Door, laid-back Dude persona.

“The interesting truth about him is that he’s rather tortured all the time. He says in the film he’s rather reluctant to all of this (film career). I think he came to it obviously through the legacy of his father (the late actor Lloyd Bridges) and his older brother Beau, But he even says he’s a little bit lazy, he’s got a little of the Dude in him, and it’s always kind of hard for him to kind of gear himself up again.”

This “drag me to the party” resistance and ambivalence is how he moves through life. She says some Bridges collaborators, such as Terry Gilliam and John Goodman, speak to his cautious approach.

“He’s not a spontaneous, improvisational actor,” says Levin. “He really needs to know what and where. He has guides who school him in being a junkie or a drunk. He takes that all very seriously and seems to form close relationships with these people who sort of become his models for how to play various parts.

“I think he’s very particular about the kinds of things he chooses. I think he picks films that have some intrigue for him and not necessarily what are going to be the biggest blockbusters. He’s a very individual star. I think he’s really on his own path.”

While Levin enjoyed “amazing access” to Bridges and Co., she found his well-protected veneer hard to penetrate:

“You’ll see in this film there’s a much darker side to Jeff than people realize, and this kind of push-me, pull-you about the acting is really a great revelation. People think he’s easy going about it, and he’s really not. But he doesn’t divulge dark disappointments and things like that. Others say it.”

She says if there are secrets to pry loose, “you gotta be long and deep with him,” adding she didn’t establish a rapport that might have led to such intimacies.

As for Bridges being an American Master, she says, “He’s worked with remarkable directors, he has an extraordinary body of work. He’s an amazing amalgam. He’s an artist on many, many levels.”

Related Articles

- Jeff Bridges looks back on “Lebowski” for “The Dude Abides” (hollywoodnews.com)

- WATCH: Jeff Bridges Almost Told Coen Brothers No On ‘Big Lebowski’ (huffingtonpost.com)

- Jeff Bridges, from The Dude to The Duke (thestar.com)

- Jeff Bridges Previews Debut Album at L.A. Show (musicbusinessheretic.wordpress.com)

- Jeff Bridges Looking to Adapt and Star in ‘The Giver’ (moviefone.com)

Related articles

- Jeff Bridges Previews Debut Album at L.A. Show (musicbusinessheretic.wordpress.com)

- Jeff Bridges Looking to Adapt and Star in ‘The Giver’ (moviefone.com)

“Lovely, Still,” that rare film depicting seniors in all their humanity, earns writer-director Nik Fackler Independent Spirit Award nomination for Best First Screenplay

I am reposting this article I wrote about Lovely, Still, the sweet and searing debut feature film by Nik Fackler, because he has been nominated for an Independent Spirit Award for Best First Screenplay. The film stars Martin Landau and Ellen Burstyn in roles that allow them to showcase their full range humanity, a rare thing for senior actors in movies these days. If the movie is playing near you, take a chance on this low budget indie that actually has the look of a big budget pic. If you didn’t have a chance to see it in a theater, you can look for it on DVD. As deserving as the film is for Oscar consideration, particularly the performances by Landau and Burstyn, it’s unlikely to break through due to its limited release. The following article I wrote for the New Horizons comes close to giving away the film’s hook, but even if you should hazard to guess it the film will still work for you and may in fact work on a deeper level. That was my experience after knowing the hook and still being swept away by the story. It happened both times I’ve seen it. My other Lovely, Still and Nik Fackler stories can be found on this blog.

NOTE: The Independent Spirit Awards show is broadcast February 26 on cable’s Independent Film Channel (IFC). That is the night before the Oscars, which is fitting because the Spirit Awards and IFC are a definite alternative to the high gloss, big budget Hollywood apparatus. I will be watching and rooting for Nik.

“Lovely, Still,” that rare film depicting seniors in all their Humanity, earns writer-director Nik Fackler Independent Spirit Award nomination for Best First Screenplay

©by Leo Adam Biga

Published in the New Horizons

Hollywood legends seldom come to Omaha. It’s even rarer when they arrive to work on a film. Spencer Tracy and Mickey Rooney did for the 1938 MGM classic Boys Town. Jack Nicholson and Kathy Bates crashed for Alexander Payne’s About Schmidt in 2001.

More recently, Oscar-winning actors Martin Landau and Ellen Burstyn spent two months here, during late 2007, as the leads in the indie movie Lovely, Still, the debut feature of hometown boy Nik Fackler.

True, George Clooney shot some scenes for Up in the Air in town, but his stay here was so brief and the Omaha footage so minimal that it doesn’t really count.

Lovely, Still on the other hand was, like Boys and Schmidt before it, a prolonged and deep immersion experience for the actors and the crew in this community. Landau and Burstyn grew close to Fackler, who’s young enough to be their grandson, and they remain close to him three years later.

Since the production practically unfolded in Fackler’s backyard, the actors got to meet his family and friends, some of whom were on the set, and to visit his haunts, including the Millard eatery his family owns and operates, Shirley’s Diner. It’s where, until recently, Nick worked. It’s also where he carefully studied patrons, including an older man who became the model for Lovely protagonist Robert Malone (Landau).

Then there’s the fact the film drips Omaha with scenes in the Old Market, Gene Leahy Mall, Memorial Park and Country Club neighborhood. Omaha’s never looked this good on the big screen before.

After select showings in 2008 and 2009, including a one-week run in Omaha last year, Lovely is finally getting a general release this fall in dozens of theaters from coast to coast. It opened September 24 at the Midtown Cinema and Village Pointe Cinema in Omaha and other cities across the U.S..

For Fackler, 26, it’s the culmination of a long road that goes back to when he first wrote the script, at 17. Over time, the script evolved and once Landau and Burstyn came on board and provided their input, it changed some more. Finally seeing his “baby” reach this point means much to Fackler.

“I’ve been very emotional,” he said. “I didn’t think I was going to be emotional but I have been. It’s been nine years of persistence and positivity and not giving up. It’s always been this thing in my life, Lovely, Still, that’s never gone away, and now I’m going to let it go away, and it feels good because I’m ready to let it go…

“I wanted it to come out a couple years ago, and it was delayed. Now it’s finally coming out and I feel sort of a distance from it, but at the same time it’s good I feel that because there’s nothing a bad review can say that won’t make me proud of the accomplishment. It just feels good to know that it’s out there.”

The film, which has received mixed critical notices, does well with audiences.

“People that pick up on the emotions and the feelings in the film seem to really be attached to it and love it,” Fackler said. “It’s either people really get it and get something emotional from it or people don’t get it.”

The PG movie’s slated to continue opening at different theaters throughout October before going to DVD November 9.

Lovely had its requisite one-week screenings in Los Angeles and New York to qualify for Academy Awards consideration. While many feel Landau and Burstyn deliver Oscar-caliber performances, the odds are stacked against them because of the film’s limited release and non-existent budget for waging an awards campaign.

Rare for features these days, the film focuses on two characters in their late 70s-early 80s. Rare for films of any era it stars two actors who are actually the advanced ages of the roles they essay. The film also approaches a sensitive topic in a way that perhaps has never been seen before.

Now for a spoiler alert. The film hinges on a plot twist that, once revealed, casts a different meaning on events. If you don’t want to know the back story, then stop reading here. If you don’t care, then continue.

Without getting specific, this story of two older people falling in love is about a family coping with Alzheimer’s Disease. Unlike perhaps a Lifetime or Hallmark Hall of Fame movie, Lovely never mentions the disease by name. Instead, its effects are presented through the prism of a fairy tale, complete with exhilarating and terrifying moments, before a dose of stark reality, and an ending that’s pure wistful nostalgia.

What makes the film stand out from most others with a senior storyline is that

Landau and Burstyn create multidimensional rather than one-note characters. The script requires they play a wide range of emotional and psychological colors and these two consummate actors are up to fully realizing these complex behaviors.

A Best Supporting Actor Oscar winner for Ed Wood, Landau returned to Omaha last year to promote Lovely. He said he was drawn to the material by its depth and nuance and by the opportunity to play an authentic character his own age.

“I get a lot of scripts where the old guy is the crusty curmudgeon who sits at the table and grunts a lot, and that’s that, because we kind of dismiss (old) age. So, the chance of exploring this many sides of a man, and the love story aspect of the older couple, presented an interesting arc.”

The actor marvels at how someone as young as Fackler could tap so truthfully the fears and desires of characters much older than himself. During an interview at North Sea Films, the Omaha production company of co-producer Dana Altman, Landau spoke about the pic, playing opposite his friend Ellen Burstyn, and working with wunderkind writer-director Fackler, whom he affectionately calls “the kid.”

Ellen Burstyn and Martin Landau from Lovely, Still

Before there was even a chance of landing an actor of Landau’s stature producers had to get the script in his hands through the golden pipeline of movers and shakers who make feature film projects possible. Fackler’s script long ago earned him a William Morris agent — the gold standard for artists/entertainers.

Landau explained, “Nick sent it to William Morris, who has an independent feature division, who sent to my agent, who sent it to me. I liked it a lot, but I felt there were bumps in it at the time. Some scenes that shouldn’t be in the first act, some scenes that needed to be in the first act. What the second act was I had no idea.” Enough substance was there that Landau expressed interest. It was only then he learned the unlikely author was a not-long-out-of-high school 20-something whose directing experience consisted of low budget shorts and music videos.

“I said, “I want to meet with the writer, figuring somebody maybe close to my age. I said, ‘How old is he?, and they said 22 (at the time). A few minutes later my eyes were still crossed and I said, ‘Wow. I mean, how does a 22 year-old write an older couple love story with this texture?'”

The venerable, much honored actor took a lunch meeting with the Generation Y upstart at an L.A. cafe. Each was a bit wary whether he could work with the other. Landau recalled that initial meeting, which he used to gauge how open Fackler was to accepting notes to inform rewrites:

“I basically said, ‘This is a terrific script, but it’s bumpy. If you’re willing to do this with me, I’ll do the movie,’ and Nick said, ‘OK.’Well, he did a rewrite on the basis of what we talked about, For two months we talked on the phone, several times a week, five or six pages at a time” to smooth out those bumps.

Landau and Fackler devised a wish list of actresses to play Mary. Burstyn, the Best Actress Oscar-winner for Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, was their first choice. On Landau’s advice Fackler waited until the rewrite was complete before sending the script to her. When she received it, she fell in love with the property, too.

Even as much as he and Burstyn loved the storyl, signing on with such an inexperienced director was a risk “It was a leap of faith working with a kid,” said Landau, “but he’s talented and adventurous and imaginative and willing to listen. He reminds me of Tim Burton. Less dark, maybe a little more buoyant.”

In the end, the material won over the veterans.

“Actors like me and Ellen are looking for scripts that have some literary value. Good dialogue today is rare. Dialogue is what a character is willing to reveal to another character. The 90 percent he isn’t is what I do for a living. It’s harder and harder to get a character-driven movie made by a studio or independents and it’s harder to get theaters to take them, so many go directly to DVD, if they’re lucky. Others fall through the cracks and are never seen, and that’s going to happen more.”

The suits calling the shots in Hollywood don’t impress Landau.

“Half the guys running the studios, some of them my ex-agents, haven’t read anything longer than a deal memorandum. And they’re deciding what literary piece should be made as a film?”

He likes that this movie is aimed for his own underserved demographic.

“A lot of older people are starved for movies,” he said. “They’re not interested in fireballs or car chases or guys climbing up the sides of buildings.”

He attended a Las Vegas screening of the pic before a huge AARP member crowd and, he said, spectators “were enwrapped with this movie. It talked to them. I mean, they not just liked it, it’s made for them. There’s a huge audience out there for it.”

Instead of an age gap they couldn’t overcome, Landau and Fackler discovered they were kindred spirits. Before he got into acting, Landau studied music and art, and worked as an editorial cartoonist. He draws and paints, as well as writes, to this day. Besides writing and directing films, Fackler is a musician and a visual artist.

“I feel that Martin and I are very similar and we get along really well,” said Fackler, who added the two of them still talk frequently. He described their relationship as a mutually “inspired” one in which each feeds the other creatively and spiritually. Fackler also feels a kinship with Burstyn. He said he gets away to a cabin she has in order to write.

“One of the main things Martin repeated to me over and over again was, ‘This is your movie.’ He made sure that rang in my ears,” said Fackler, “just to make sure I stayed strong when I came up against fights and arguments with people that wanted the film to be something I didn’t want it to be, and much love to him for doing that. Those words continue to ring in my ear in his voice to this day, and I’m sure for the rest of my career.”

Landau and Burstyn brought their considerable experience to bear helping the first-time feature director figure out the ropes, but ultimately deferred to him.

“All good films are collaborations,” said Landau. “A good director, and I’ve worked with a lot of them (Hitchcock, Mankiewicz, Coppola, Allen), doesn’t direct, he creates a playground in which you play. Ninety percent of directing is casting the right people. If you cast the right people what happens in that playground is stuff you couldn’t conceive of beforehand.”

“It was collaborative,” said Fackler. “We were a team, it was artists working together the same way a group of musicians make a band. We became friends and then after we became friends we respected each other’s opinions.”

As for working with Burstyn, Landau said, “it’s a joy. She’s a terrific actress.” He compared doing a scene with her to having a good tennis partner. “If you’re playing pretty well and you’ve got a good partner you play better. You don’t know exactly where they’re going to place the ball, and it’s that element when Ellen and I work together we have. It’s never exactly the same. She’ll throw the ball and I’ll get to the ball, toss it back to her, so that it’s alive. I won’t call them accidents but they are sin a way, which is what living is, and that element of unpredictability and ultimately inevitability, is what good acting is about. That stuff is what I care about.”

Not every review of the film has been positive. Some critics seem uneasy with or dismissive of its emotionalism, complaining it’s too cloying or precious. That emotional journey of a man who believes he’s falling in love for the first time, only to find out the bitter truth of what he’s lost, is what appealed to Landau.

“The interesting thing about this movie is that if you took away the last act you could cast 15 year-olds in it and not change a lot,” said Landau. “Nick (first) wrote it when he was 17. It’s basically a teenage romance. There’s something simplistic and sweet about these two people who want to be together. Robert’s naive, he’s a kid on his first date. That’s why Nik was able to write it — because he was going through stuff, his first love. The primal feelings people have at 15 or 50 or 80 are pretty much the same.”

Landau is proud to be associated with the film for many reasons, among them its effective portrayal of memory loss.

“I absolutely believe in this film. When I did Ed Wood I felt that way. But this one because I know so many people who’ve had memory problems or are having memory problems. My brother-in-law had Alzheimer’s. A lot of close peers of mine. The Alzheimer’s Association is very behind this movie because it rings true…”

Related Articles

- Movie Review | ‘Lovely, Still’: A Late-Life Relationship (movies.nytimes.com)

- Filmmakers to Watch (gointothestory.com)

- Martin Landau, A ‘Lovely’ Leading Man (npr.org)

- Seniors Are Having Lots of Sex (newsweek.com:80)

Related Articles

- Martin Landau and Nik Fackler Discuss Working Together on ‘Lovely, Still,’ and Why They Believe So Strongly in Each Other and in the New Film (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- “2011 Film Independent Spirit Award Nominations” and related posts (filmofilia.com)

- Filmmakers to Watch (gointothestory.com)

- Omowale Akintunde’s In-Your-Face Race Film for the New Millennium, ‘Wigger,’ Introduces America to a New Cinema Voice (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Yolonda Ross is a Talent to Watch (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Beware the Singularity, singing the retribution blues: New works by Rick Dooling

Slaying dragons: Author Richard Dooling’s sharp satire cuts deep and quick

The best writing challenges our preconceptions of the world, and Rick Dooling is an author who consistently does that in his essays, long form nonfiction, and novels. He’s also a screenwriter. If you know his work, then you know how his language and ideas stretch your mind. If you don’t know his work, then consider this a kind of book club recommendation. I promise, you won’t be disappointed. The following piece I did on Dooling appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) a couple years ago upon the release of his book, Rapture for the Geeks, When AI Outsmarts IQ. The work reads like a cross between a love ballad to the wonders of computer technology and a cautionary tale of that same technology one day overtaking humans’ capacity to control it. Around this same time, a suspenseful, supernatural film Dooling wrote the screenplay for from a Stephen King short story, Dolan’s Cadillac, finished shooting. Dooling previously collaborated with King on the television miniseries, Kingdom Hospital. Dooling is currently working on a TV pilot.

You can find more pieces by me on Rick Dooling, most efficiently in the category with his name, but also in several other categores, including Authors/Literature and Nebraskans in Film.

Beware the Singularity, singing the retribution blues: new works by Rick Dooling

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

It’s been awhile since Omaha writer Rick Dooling, author of the novels White Man’s Grave and Brainstorm, enjoyed this kind of traction. Fall 2008 saw published his cautionary riff Rapture for the Geeks: When AI Outsmarts IQ (Harmony Books). His screen adaptation of Stephen King’s short story, Dolan’s Cadillac, will soon be released as an indie feature. Dooling, collaborator with King on the network television series Kingdom Hospital, was flattered the master of horror himself asked him to tackle Dolan, a classic revenge story with supernatural undertones.

Dooling’s no stranger to movie-movie land. His novel Critical Care was adapted into a Sidney Lumet film. The author was preparing to adapt Brainstorm for Alan J. Pakula when the director died in a freak accident. Then there was the creative partnership with King. But writing books is his stock-in-trade, and even though Dolan could change that, Rapture’s what comes to mind in any appreciation of Dooling.

Like much of his socially conscious work Rapture’s a smart, funny, disturbing, essay-like take on a central conflict in this modern age, one that, depending on your point of view, is either rushing toward a critical tipping point or is much ado about nothing. He fixes on the uncomfortable interface between the cold, hard parameters of computer technology’s increasing sophistication and meta-presence in our lives with existential notions of what it means to be human.

High tech’s ever more integrated in our lives. We rely on it for so many things. Its systems grow faster, more powerful. Dooling considers nothing less than humankind nearing an uneasy threshold when the artificial intelligence we’ve engineered surpasses our own. He lays out how the ongoing exponential growth of super processing capabilities is a phenomenon unlike any other in recorded history. The implications of the singularity, as geeks and intellectuals call this moment when interconnected cyber systems outstrip human functioning, range from nobody-knows-what-happens-next to dark Terminator-Matrix scenarios.

A fundamental question he raises is, Can the creators of AI really be supplanted by their creation? If possible, as the book suggests it is, then what does that do to our concept of being endowed with a soul by a divinity in whose image we’re made? Is synthetic intelligence’s superiority a misstep in our endeavors to conquer the universe or an inevitable consequence of the evolutionary scheme?

“Well, we all know what evolution is. We’ve read about it, we understand it, it’s just that we always have this humancentric, anthropocentric viewpoint,” Dooling said. “Wouldn’t it make perfect sense there would be another species that would come after us if evolution continued? Why would we be the last one?”

Is AI outsmarting IQ part of a grand design? Where does that leave humanity? Are we to enter a hybrid stage in our development in which nanotechnology and human physiology merge? Or are we to be replaced, even enslaved by the machines?

The real trouble comes if AI gains self-knowledge and asserts control. That’s the formula for a rise-of-the-machines prescience that ushers in the end of homo sapien dominance. Or has mastery of the universe always been an illusion of our conceit? Is the new machine age our comeuppance? Have we outsmarted ourselves into our own decline or demise? Can human ingenuity prevent a cyber coup?

Arrogantly, we cling to the belief we’ll always be in control of technology. “Do you believe that?” Dooling asked. “It is kind of the mechanical equivalent of finding life on other planets.” In other words, could we reasonably assume we’d be able to control alien intelligent life? Why should we think any differently about AI?

Pondering “what man hath wrought” is an age-old question. We long ago devised the means to end our own species with nuclear/biological weapons and pollutants. Nature’s ability to kill us off en masse with virus outbreaks, ice cap melts or meteor strikes is well known. What’s new here is the insidious nature of digital oblivion. It may already be too late to reverse our absorption into the grid or matrix. Most of us are still blissfully unaware. The wary may reach a Strangelove point of How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Microchip.

It’s intriguing, scary stuff. Not content with simply offering dire predictions, Dooling examines the accelerating cyber hold from different perspectives, presenting alternate interpretations of what it may mean — good, bad, indifferent. This kaleidoscopic prism for looking at complex themes is characteristic of him.

Extremities lend themselves to the satire he’s so adept at. He finds much to skewer here but isn’t so much interested in puncturing holes in theories as in probing the big ideas and questions the coming singularity, if you ascribe to it, inspires. His drawing on scientific, religious, literary thinkers on the subject confirms his firm grasp and thorough research of it.

The project was a labor of love for Dooling, a self-described geek whose fascination with computers and their content management, data base applications began long before the digital revolution hit main street. We’re talking early 1980s. “Not many writers were drawn to computers that early,” he said, “but of course now you can’t write without a computer most people would say.”

Richard Dooling

He designs web sites, he builds computers and because “I knew I wanted to write about this,” he said, “I knew I was going to get no respect until I could at least write code and do programming.” Deep into html he goes.

The pithy, portentous quotations sprinkled throughout the book come from the vast files of sayings and passages he’s collected and stored for just such use.

Aptly, he became a blog star in this high-tech information age after an op-ed he wrote that drew heavily from Rapture appeared in The New York Times. His piece responded to oracle Warren Buffett’s warning, “Beware of geeks bearing formulas,” following the stock market crash. Dooling enjoys Web exchanges with readers.

“I’m telling you every blog from here to Australia quoted this op-ed, with extended commentary. I’ve never seen anything like that happen with my work before. It took me completely by surprise. It makes you realize how powerful the Internet is.”

If you doubt how ingrained our computer interactions are, Dooling said, think about this the next time you call Cox Communications with a technical issue:

“Your first few minutes of interaction are being handled by a chatterbot,” Dooling said, “and some people don’t even realize it. It’ll say, ‘Let me ask you a few questions first,’ and then it’ll go, ‘Hold on and I will connect you with one of our assistants’ or something like that. And when you’ve reached the point where the thing has gathered everything it can automatically gather now you need an intervention from someone in India to come on and actually take over and start doing the human interaction. Until then, that’s a piece of software talking to you.

“The chatterbots are getting very good. It’s taking longer and longer in a Turing Test type of situation” for people to determine they’re bandying back and forth with a machine not another person. He said that’s because advanced chatterbots can be programmed to exhibit qualities like humor or variations of it like sarcasm.

“I mean the very first one, Eliza, I talk about in there (Rapture), they fooled hundreds of people with in the beginning because people were naive back then. The designers did it just by turning every question around. They call the software a Rogerian Psychiatrist because you go, ‘I hate my brother,’ and it responds, ‘Why do you hate your brother?’ Or you say, ‘I feel terrible today, and it goes, ‘Why do you feel terrible today?’ My favorite one is, ‘My brother hates me’ and it asks, ‘Who else in your family hates you?’ Do you love it?”