Archive

Standing on Faith, Sadie Bankston Continues One-Woman Vigil for Homicide Victim Families

For years I read about this Omaha woman who has dedicated her life to help the families of homicide victims since she losing her own son to a senseless act of violence and finding the support network for grieving loved ones to be wanting. I finally met Sadie Bankston a couple years ago and this is her story. It originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com), and I think you will find her as determined and compassionate as I did. She goes to rather extraordinary lengths to help people, mostly women, who in a very real way become the secondary victims of homicides. Her clients may have lost a son or a daughter or a mate, and without the help she and thankfully some others now provide, these hurting parents and spouses are in danger of being casualties themselves. Sadie carries on her work through her own nonprofit, PULSE, and she can always use more donations and resources to help out families trying to cope with the trauma of losing someone dear and often having to relive it through criminal investigations and court proceedings.

Standing on Faith, Sadie Bankston Continues One-Woman Vigil for Homicide Victim Families

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Whenever Omahan Sadie Bankston hears of a new homicide, her heart aches. Her son Wendell Grixby was shot and killed in 1989 in the Gene Leahy Mall. He was 19. An outpouring of support followed. Then Sadie was on her own. Paralyzed by pain. She sensed others expected her to move on with her life after a certain point. The rest of her adult kids had lives, families, careers of their own. She was single. There wasn’t anyone around to confide in who’d been in her place — another parent who’d suffered the same nightmare of a murdered son or daughter.

Violent crimes in Omaha only escalated. A growing number, gang-related. Others, domestic disputes or random acts turned deadly. Guns the main weapons of choice in the mounting homicide tallies. Sadie felt called to do something for others left adrift in the wake of such loss. She identified with their heartbreak.

Without a degree, she couldn’t provide formal mental health assistance, but she could reach out — mother to mother, heart to heart. Talking, praying, holding hands, preparing care packages, extending a lifeline for people to call day or night. Bearing witness for families at court hearings.

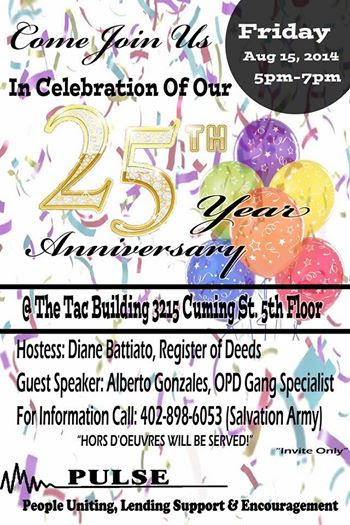

She’s been doing all this and more through the nonprofit organization she started in 1991 — PULSE or People United Lending Support and Encouragement.

Mary E. Lemon’s daughters Saundra and Renota Brown were stabbed to death last Christmas Eve in the basement of an Omaha home. The grieving mother has relied on Sadie to get through many long days and nights.

“Sadie has been a help,” said Lemon. “I call her and talk to her whenever I feel I need to talk to somebody, and that happens quite often. It helps to know that there is someone out there who cares — that you can talk to. And Sadie’s made me feel as if I could talk to her at anytime. She’s a friend worth having, I’ll tell you.”

PULSE began as a support group for mothers who’ve lost a child to homicide. The meetings “phase in and out” now due to funding limitations. Sadie hopes to start the sessions again. She knows how vital these unconditional forums can be.

“You hear their loneliness, their pain, their sleeplessness, their hopelessness. Will I ever stop crying? Those kinds of things. It’s just to come together with other parents who have lost. We have a common denominator there.”

Virgil Cook Jr. and his wife Patricia fell into a depression after their son, Little Virgil. was shot and killed in 1991. They thought they were alone in their grief until Sadie introduced the Native American couple to others suffering like them.

‘We found there are other people like us who’ve been through the same thing. White people, black people, Spanish people. We’re all in the same boat. We’ve become friends,” said Cook.

Sadie’s only guide in the beginning was her own experience. “Just the pain that I knew that I felt,” she said. “I knew other mothers were feeling the same, so I just wanted to help in some way to steer them in the right path as far as help and support.” She knew the most powerful thing she could offer was having walked the same painful journey they’re on. “When you can embrace someone and say, ‘I know how you feel.’ and really know it, it makes a difference,” said Sadie, whose eyes ooze empathy and mirror survival. “I always say, ‘The pain won’t go away, but it will get softer.’”

Lemon said she appreciates dealing with someone who’s walked in her shoes. Their conversations can be about anything or nothing at all. “I talk to Sadie at least once if not twice a week,” she said.

“We talk about my girls, we talk about old days, growing up in the old neighborhood, we talk about a lot of things. Just to kind of relieve my nerves, you know.”

Once Sadie enters a family’s life she sticks. Even years later, despite moves, remarriages, the bond remains.

“They’re not left alone with me around,” she said, “because I’m calling them.”

PULSE volunteer Denise Cousin got acquainted with Sadie while an Omaha police captain. Now retired, Cousin feels Sadie builds rapport by carrying no institutional agenda or baggage. She’s open, she’s real, she’s honest. She’s just Sadie.

‘“I think because she is not representing any type of governmental entity, there’s no concern the family’s going to be jeopardized as far as what they tell her. She does not have that attachment. And I think it is her personality. She is down to earth. She lets the family know she’s there for them. She kind of comes across as the mother figure. She comes across as family, and so she breaks that barrier of a professional I’m-here-to-tell-you-something.”

Cook said he and his wife regard Sadie “as an older sister” even though they have a few years on her. He credits her with getting them out of the deep funk they fell into after Little Virgil was killed.

“We didn’t want to work, we didn’t want to go anywhere, we didn’t want to do anything. Things got real bad. She helped us out of that ugly state. She’s been like an angel to us. Everybody needs a Sadie.”

With her warm, soulful, old-school way, it’s easy picturing Sadie as everyone’s auntie or big mama or sistah. A girlish, impish side shines when she laughs. She’s no pushover though. A steely, sassy righteousness shows through when describing disrespectful “bagging and sagging” young men, silly girls getting pregnant and senseless gun play taking lives and wrecking havoc on families and neighborhoods.

This woman of faith ascribes her own healing to her higher power. “My source, and still is my source of comfort and strength,” she said, casting her eyes heavenward. A hardness shows, too, when she bemoans PULSE’s chronic financial straits. PULSE grew beyond being merely a support group to a multi-faceted human services operation providing food, clothes and other support. Ambitious programs, including at-risk workshops, were drawn up.

But as a largely one-woman band, Sadie’s left to scratch for dollars and volunteers wherever she can find them. There’ve been many supporters. Churches, businesses, individuals. Lowes donated materials to renovate the house she resides-offices in. Sadie and fellow victim moms did all the labor. Lamar Advertising does billboards for Stop the Violence messages. Popeye’s Chicken donates dinners for We-Care packages PULSE delivers to families.

An annual Mother’s Day banquet she hosts relies on donated food and facilities. Lately though she’s cut back PULSE services.

All the begging, all the scrounging, all the promised donations that don’t come through, all the unrealized dreams get to be too much at times. “I’m just tired of constantly having to ask.” Then there’s her own well-being. She was 46 at PULSE’s start. She’s 63 now. Like many caregivers the last person she thinks of is herself. She realizes that has to change. “I figure I should be taking care of myself because I’m a senior citizen now. I’m just tired.”

A bad back prevents her from working. She’s on disability. Despite this hand-to-mouth existence the work of PULSE goes on, largely unheralded. Oh, she receives glowing endorsements.

Omaha Police Department Sgt. Patrick Rowland said, “What makes Sadie effective is she’s determined to make a difference even when it’s not the most pleasant of times. She gets out there and she still tries. She truly cares for people. She doesn’t judge them or the circumstances in which their loved ones lost their life. She sees the families as being victims also. She cares about the police, too. She wants them to do a good job. She understands the difficulty in trying to solve these things.”

Sadie’s declined Woman of the Year citations. She’s not looking for awards or pats on the back, but tangible support. The situation’s akin to the way parents feel when a child’s been murdered. Life must go on but until someone notices their pain, it’s hard to want to go forward. Attention must be paid. She said one of the hardest things in the aftermath of her son’s murder was the unpleasant realization the world was oblivious to her sorrow. Instead of validating her trauma, life ground on as usual. It made the void that much more cruel. In her outreach work Sadie’s found nearly everyone experiencing a loss feels a sense of emptiness and abandonment at their suffering being ignored or minimized. It’s as if society tells you, “they’re gone,” so get on with your life, she said.

“When I talk to mothers they explain it the same way. When my son was murdered I was driving somewhere and the street lights were still coming on and I wondered, Why is this going on just like nothing happened? People are still walking and laughing like nothing had happened. It’s a sad feeling, yeah. I wouldn’t say so much lonely. It’s just more, Here, feel my pain — recognize I’m hurting here. Instead of people still eating their ice cream like nothing has affected you, you want everybody to stop and acknowledge what you’re going through.”

She inaugurated the Forget Us Not Memorial Wall shortly after launching PULSE. The commemorative marker ensures victims like her son “will not be forgotten.” Resembling an opened Bible, the tall, custom-made wooden memorial has hinged panels that presently display 150 name plates, most accompanied by a likeness of the victim. The majority of victims are African-American. Two OPD officers slain in the line of duty — Jimmie Wilson Jr. and Jason Pratt — are among those memorialized. A small collection box next to the memorial accepts donations.

Sadie contacts families for permission to affix their loved ones’ names to the wall. The memorial’s had different homes. It’s now displayed at St. Benedict the Moor, 2423 Grant St. The church’s pastor, Rev. Ken Vavrina, champions Sadie’s work. “She has a good heart, she’s compassionate, and she’s been there,” he said. “And she’s worked now over the years with so many families who have a lost a child she really is good at it. She’s developed the expertise of being able to reach out and support these families who have had someone killed. It’s a great idea. I don’t know of any other organization that is doing what she’s doing — certainly not as consistently as she does. We’re honored to have it (the wall) here.”

He and Sadie admit the wall’s not up to date. So many killings. So hard to keep up. “I had no idea it was going to be filled up (so quickly) that we had to have two more extensions put on it. I was just thinking in the here and now,” she said.

In the years following Wendell’s death Omaha homicides exploded. There were 12 in 1990, 35 in 1991 and an average of 31 over the next 17 years, with the count reaching a record 42 last year. 2008 has already seen 40-plus homicides. With more frequency than ever killings happen in waves. This year alone has seen a handful of weeks with multiple fatalities each. “I just don’t know what to say or think about the recent rash of homicide that is plaguing our community,” Sadie said in response to a flurry of gun deaths in early November.

A problem once seen confined to northeast Omaha appears more widespread, including recent incidents in Dundee and south Omaha and, most starkly, the deadly spree at the Westroads Von Maur in 2007. Community responses to the problem are evident. Prayer vigils, anti-violence summits, stop-the-violence campaigns, sermons, editorials, articles, proposed ordinances to stiffen gun laws, public discussions on ways to stem the flow of guns and, ironically, increased gun sales/registrations as people arm themselves to feel safer.

She doesn’t like turning anybody away. “I refer people PULSE cannot help to The Compassionate Friends (a national nonprofit grief assistance group with an Omaha chapter). I don’t let them just drown out there. I don’t say we can’t help you and let it go.” There’s not much she lets go of once she latches onto something.

“I have to say I admire Sadie’s persistence, because she has encountered numerous roadblocks and obstacles. Not getting paid a dime for this. Very little if any type of donation comes her way. This is strictly a heartfelt humanitarian effort that she continues to push on, day after day, year after year. I think most of us would say, ‘That’s it, I’m tired, I’m ready to go on to other things,’” said Denise Cousin. That’s why when Sadie reached a point of no return last summer, Cousin was sympathetic.

A March car accident left Sadie with severe injuries, including two torn rotator cuffs. “I’m in pain now. The accident had a lot to do with it. Then I have nerve damage from having two teeth pulled.” Bad enough. But when Sadie learned the office the Salvation Army let PULSE use starting a year ago would no longer be available, it was more than she could take. She’d talked about closing PULSE before but this was different. “This time I was really at my lowest,” she said. After all, a body can only take so much. It’s why on June 25 she called reporters and friends together to announce PULSE’s end. “I’m tired of the struggle,” she told the gathering. Among those in attendance were some of the parents she’s comforted over the years. They expressed appreciation for all PULSE has done.

Cousin let her know it was OK to walk away. “I was in her corner there saying, You have put in a sufficient amount of time. I can understand you being tired.” Vavrina empathized, too. “Sadie got discouraged and I can understand she gets discouraged, because she’s financially strapped all the time. She doesn’t get the support she needs,” he said. “We try to help her as much as we can.” “But then she called me and said she just couldn’t put it down. She still felt compelled to help families,” said Cousin.

Soon enough, the word got out — Sadie was back and recommitted to serving what’s become her life’s mission. What helped change her mind were messages from friends, associates and complete strangers. One, from a woman who identified herself as Eunice, stood out: “I’m calling you Miss Bankston because you were placed in that position for a reason. God put you there, sweetheart. Don’t get weary yet. I get weary at times, too. I know you’re tired. You become tired when you’re trying to do something all by yourself, baby, but you’re not by yourself. God doesn’t want you to get weary. He’ll lift you up. It seems nobody cares but we do care, because that’s our future out there dying daily. We see it. And it’s time for us as women to come together and stop it. Please don’t give up yet, Miss Bankston. I beg you in Jesus’ name.”

Buoyed by such words Sadie’s staying the course, even though she still battles health problems, still pleads for money, still gets frustrated fighting the good fight on little more than goodwill and prayer. But she can’t bear to turn her back on the truth: the killings go on unabated and each time a family’s left to pick up the pieces. “So I must go on. Life goes on. You know I must love what I’m doing or I wouldn’t be doing it for this long,” said Sadie. “I love what I do. You know it’s not for money. Anytime you can reach out and help people it is just so nice. That’s what we’re put here for — to love our brothers and sisters.”

Lemon wouldn’t have blamed her if she had quit but added, “I’m glad she didn’t. Sadie does a job that a lot of people probably wouldn’t even consider doing. Sadie is a special person, That job is meant for Sadie. She does such a good job.”

Sadie plans going about it smarter now though. For years she resisted advice that she should write grant applications for operating funds. Recently, she devised a budget for a year-long project grant. If she gets the monies PULSE will gain the financial stability it’s never enjoyed before. She needs it to ease her mind.

“I’m not going to overstress myself because if I’m no good for myself I’m no good for anyone else. I just can’t do it anymore. I’m not gong to do it anymore.”

Vavrina’s sure it’s a sound strategic move. “Now that she’s doing it the right way,” he said, “I think she can get funded.” He’s encouraged Sadie has a contingency plan “that would permit PULSE to continue without her.”

Forget Me Not Memorial Wall

Her friends know she’s given so much of herself for so long she may not have much left to give. Crisis intervention takes a toll. What some don’t know is that she’s seen some hard things no one should see. “Well, why shouldn’t I see it? I mean, it happens,” she said. PULSE was part of a University of Nebraska Medical Center pilot program that trained folks like her to respond to homicide events. She was on call trauma nights. When the phone rang with a new assignment it meant going to hospitals at all hours to console loved ones. On at least one occasion, she said, “I had to tell the family their loved one was gone. I did. l mean, its really hard comforting people who’ve just lost a son or daughter. Sad, sad, sad.”

Her work at times meant going to crime scenes, where families lived amid fresh evidence of carnage. Even there, she tended to their needs. “There would be blood on the floor from shootings. There was so much it just glistened from the lights.”

She recalled the case of a young mother from Chicago. The woman’s husband kidnapped their baby and fled to Omaha. She followed, with her other kids in tow. After finding and confronting him here, he slit her throat in front of the kids. Sadie managed getting the kids released from the foster care system. Said Sadie, “Now you know how hard that is to do, don’t you? To get someone out of foster care once they’re in? I got ‘em out. I have a gift for gab when something needs to be done.” The victim’s family contacted Sadie asking her to retrieve items from the murder site. “We went into the apartment. It was all white, except where it was saturated with blood. Blood splattered all over. And we retrieved the kids’ clothes and the toys and I sent them back to Chicago. I still keep in contact with the grandma. The kids are grown now.”

Another time, Sadie observed how difficult it was for a family to be surrounded by the stain of murder in their Omaha Housing Authority unit. “Two young men were killed at home, and the blood — it was hard for the mother, for the family to see, so I contacted OHA and they came out and cleaned up everything.” Sadie had noticed a throw rug the mother avoided walking on. Sadie had trod over the same rug and it wasn’t until she got home, she said, “I realized that must have been where her son was murdered. So I called her back and I apologized, and she said, ‘That’s OK, Sadie.’”

In this conspiracy of broken hearts, Sadie said, “there’s that camaraderie” that makes explanations unnecessary. “They (OHA) had to take the carpet up because it soaked through,” Sadie said. She demonstrates she’s not just there for families once, never to be seen or heard from again. She’s there for the long haul. “If they ask for me to attend the funeral I will, and I do.” Celebrations, too. She’s cooked holiday dinners for families. She’s bought groceries, clothes. She even had a wheelchair ramp built for a family. Around her home are tokens of families’ appreciation for her going the extra mile.

Being a court advocate is another example of Sadie going beyond the call of duty. She understands the strain of seeking justice for a loved one. She attended every proceeding for her son’s assailant. To her other children’s dismay she forgave the young man, who was convicted of manslaughter and is now free. So she attends court with families — to be a pillar of strength, a shoulder to cry on. She knows the last thing a family under extreme emotional distress needs is to see her cry. “Normally I stifle my tears,” she said. She couldn’t once, she said, when it was read into evidence a female shooting victim’s “last words were, ‘It burns.’ I handed tissues to the family and I had to turn my head so they wouldn’t see my tears. It’s hard for me to find someone to go with me because I can’t have them crying.”

Sadie also treads a delicate line as a liaison between families and law enforcement officials investigating unsolved homicides. She’s well aware “snitching” is seriously frowned on by some in the African American community. “A lot of people don’t like the police and I try to be the mediator to keep an open line of communication with the police department,” she said. She said sometimes family members with information about a case tell her what they won’t disclose to police. With a family’s consent, she shares leads. “As a mother how would you feel if someone killed your child and no one came forward?”

OPD’s Sgt. Rowland, who worked with Sadie when he was in homicide, said, “She understands the situation that some of these families are put in, just by the nature of where they live and what their loved one, the homicide victim, was involved in. Sadie does what she can to get them to cooperate with the police. She’s very honest with us. Very blunt.” “She will continue to beat down a door until the information is laid at the footsteps of the police department,” said Cousin.

Sadie’s also known to put herself in harm’s way breaking up scuffles between kids before they escalate into something worse. “I try to intervene. Once, I got flung around and I landed on the hood of the car. But I got back up. I broke up the fight. The cops came. Everybody was OK,” she said. “All I’m trying to do is get ‘em to just think. When I say I lost my son some of them seem to have compassion or pity for me.” Once, a gun was pulled on her. The windows of her home have been shot out. She won’t be intimidated. Would she get involved in the middle of a dispute again? “Probably, and 100 percent if a woman we’re being hit by a man. There would be no doubt.”

She still has dreams for PULSE. She envisions youth life coaching classes. “Make them feel better about themselves, so they’ll make better choices and won’t settle for anything,” she said. “So, that’s a goal. My theory now is if we pay attention to the children maybe there’d be less grief support meetings we have to have.” Cousin suspects Sadie will go right on with PULSE till her dying days.

“As long as we continue to have homicides in this community and as long as there’s breath in her body Sadie will continue to help the families. She’s quite remarkable and definitely unforgettable.” Miss Sadie may not have everything to give she’d like but, she said, “I have my heart and my family. And I have hope. Keep hope alive. I guess I have to stand on faith.”

Related Articles

- Unsolved murder is not forgotten, family says at vigil (mysanantonio.com)

- N.J. 211 hotline expands as one-stop shop for social services information (nj.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Miss Leola Says Goodbye (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Crowns: Black Women and Their Hats (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- An Inner City Exhibition Tells a Wide Range of Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Nancy Duncan: Her final story

I got to know the late Nancy Duncan better than I do a lot of my profile subjects. You might even say we became friends. I had written about her and her work as a professional storyteller. We hit it off. When she developed cancer and began undergoing a regimen of treatments and surgeries, she began doing what came naturally to her — putting her experiences into stories. When told she was terminal, she and I eventually arrived at the idea of her telling one last story, in effect, by sharing her odyssey with the public. The piece appeared in The Reader (www.thereader,com). Not long after the article appeared Nancy died peacefully, having said all her goodbyes and having left the gift of her humor and intelligence and grace with thousands in the form of her stories, which will live on forever.

Nancy Duncan: Her final story

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Professional storyteller Nancy Duncan felt the tell-tale lump on her right breast in 2000. She recalled it being “about two digits long, as round as a pencil and as hard as a rock. I knew the minute I touched it what it was.” Doctors soon confirmed her suspicion. Cancer. “Somehow it had just sneaked through the mammograms.”

After a mastectomy and chemotherapy, her illness appeared under control. Then, in April 2002, she found “a little chip of a tumor” under her arm pit. “They told me it had recurred, and when they found it there they figured it was somewhere else. They did a CAT scan and there were these little specks everywhere in my liver — like from a shotgun blast,” she said. Her cancer had spread. “Metastasized. It’s a nasty word. Nobody wants to hear it. You never know where it’s going to go when it gets outside the breast,” she said. “It’ll go to your bones or to your lungs or somewhere else. Mine just happened to go to my liver.”

“Well, Nancy, you’re a terminal,” is what her doctor told her. Terminal. Aren’t we all? — Duncan wondered. The only difference between me and my doc, Duncan thought, “is that she thinks she knows what I’m going to die of.” That, and the fact the malignant tumors carrying Duncan’s death sentence play a cruel game with her. “They grow and then the chemo shrinks them. Enough so you can barely see them or they’re not visible. In about four or five months, they figure out how to get around that drug and then they come back. That routine is what I’ve been doing the past two years,” said Duncan, the Nebraska Arts Council’s Artist of the Year.

Her four-year “dance with cancer” has propelled the former theater maven into a journey of self-discovery that’s informed every aspect of her life and work. Her unfolding death is the subject of her final, most profound story.

“Storytelling is always a process of learning about yourself,” said Duncan. “The story transforms along with you and that’s exciting to realize that and to let that happen. It’s a dialogue you maintain with that story for the rest of your life.”

The most surprising thing to happen in the narrative of her evolving death, she said, is the tranquility she’s found. “It’s totally taken away the fear” she had of dying. Her late husband, Harry Duncan, an acclaimed poet and fine book printer, died at home under her watch. That experience is helping her prepare for her own death.

When she first got news of her terminal illness, she panicked. “Then, I remembered what Harry did. He just stopped eating and drinking and he was unconscious after three days and gone in a week. From the day he decided he didn’t want to live anymore, he went in this kind of graceful state. It wasn’t like he was a beaming idiot or anything. He just seemed totally at peace. Very relaxed. Loving. It was like he was teaching us all that when you’re ready, you don’t have to hang around and be tortured to death. So, I thought, I always have that option. My kids have agreed they’re not going to mess with that choice.”

The comfort Duncan gained in contemplating her own blissful exit carried over to a new freedom she felt on stage. “The interesting thing is I totally lost my fear in performing. I became completely relaxed,” she said. “It was such a gift to be able to perform two years without any fear. Yahoo! Because that is what your audience really wants. They want you embodied in that art form. They want to see you, the most they can possibly see you, broken open. And fear just gets in the way. It’s a barrier between you and the audience. It’s a good thing, because it tells you this is an important occasion and you need to be present for it. It helps you stay on your toes. But it’s also a bad thing because then you’re editing, and you don’t want to edit. What you want to do is listen to your audience and remember things and let them pop into the story. Why did I have to have cancer in order to lose that fear?”

She’s considered her cancer from every conceivable angle. She’s talked frankly about it in stories. In the published Losing and Getting, her cancer-ridden breast converses with her healthy left breast in a stream of bitterness, guilt and humor. She’s talked about losing her hair but gaining a new appreciation for life. She’s performed her cancer story for many audiences, but especially for women who are cancer survivors, patients and potential victims. She knows firsthand their fear.

“There’s also a lot of lessons you learn…” Like the harsh reality of health care in America. “If I didn’t have supplemental insurance I wouldn’t be alive today because I couldn’t afford all these chemo treatments. And a lot of people can’t afford them. They don’t have a choice. They’re not given the opportunity to have their lives extended like mine has been. Given the fact there’s so much money being made treating cancer and that cancer is growing exponentially in the world, there’s no incentive to find a cure…and definitely no incentive to prevent it. I think we don’t really want to prevent it because we don’t want to change our lives. We’re too lazy. We don’t want to give up our fossil fuels and our fatty foods. We’re so complacent. I’m as bad as anyone else. That makes me mad sometimes.”

Since finding she’s terminal, she’s tried maximizing the brief periods she feels well between her taxing treatments, stealing moments here and there to work and to spend time with the many friends and relatives who comprise her extended care team. She’s also managed performing occasionally and nurturing some of the storytelling festivals she’s helped found and grow, particularly the Nebraska Storytelling Festival in Omaha. She’s annually given 600-plus hours of volunteer time to Nebraska Story Arts, the organization that puts on the festival.

Even as her condition’s worsened, she’s continued being the state’s most visible and vocal advocate for storytelling. Omaha sculptor Catherine Ferguson called Duncan “one of Nebraska’s most treasured women. She has dedicated her professional life to connecting people to the arts and humanities. Nancy’s performances have always gone beyond entertainment to become educational.” Story Arts president Jim Marx said, “Her gift is to imagine possibilities, inspire others to join her vision and to will them into existence through tireless effort and encouragement.” Nancy’s daughter and fellow storyteller, Lucy Duncan, said, “She has a great generosity of spirit in her teaching of storytelling and wanting to spread the art form. Her support of my telling is a direct example. Instead of feeling, This is my territory, she says, Let’s share this. She’s done that with a lot of people — not just me. She’s also very beloved in the national storytelling community.”

Lately, Duncan’s good spells have grown fewer. The artist has been homebound since the end of May, when she gave her “last” performance at the Darkroom Gallery in the Old Market.

Her three grown children and several grandchildren are staying with her now in the big mid-town house she and Harry shared. It’s where he died of cancer in 1997. It’s where she intends dying, too. As the debilitating rounds of chemo have taken her longer and longer to recover from, she’s considered not undergoing them again, knowing full well stopping them will mean certain death.

“I have to pay such a huge price to feel good for about two months,” she said.

For now, at least, she tarries on, telling stories to her grandchildren or soaking up

the good vibes of her army of friends who flit in and out of her place all day long. Some come to do chores. Others bring her things. Some just come by to chat.

Reminders of her friends are everywhere, most poignantly in the paper, silk and rubber hands adorning the inside of her front door. Each “helping-healing hand” was sent or delivered to her and is adorned with a message that’s variously funny, outrageous, wise, enigmatic, just like the stories Duncan’s told since 1984, when she turned away from a career in the theater to pursue storytelling professionally.

Some visitors come to say goodbye, although few use that word, because even though Duncan is physically frail now and needs around-the-clock support, her effervescent spirit shines through, making it all the harder to imagine her gone. The light-up-the-room sparkle is still there in her eyes. So, is the ear-to-ear smile. And the cascading laugh. Ah, The Laugh. It’s an irrepressible cackle that starts in her chest, rolls up her giraffe neck and spills out her crescent mouth in a high-pitched sound that recalls the coyote-witch figures she portrays in tellings.

Then again, there’s a chronic fatigue that didn’t used to be there. Every now and then she catches her breath, swallowing hard to stem the pain from the stints in her liver. Her body, once as expressive an instrument as her animated face and voice, is gaunt and still, betraying the fight she wages to keep death at bay.

Her impending death is being recorded by Omaha videographer George Ferguson. The documentary she asked him to make is meant to help other dying individuals in their search for healing. It’s only natural that Duncan, who’s used stories as a way to interpret life, should use storytelling as a means of understanding her own end.

“I thought it might be useful to somebody else who’s dying the same way, but also to see how useful storytelling can be in helping you go through this process,” she said. “where grotesque things happen to you and people are poking your body here and there. And, where, in the middle of having stints put in your liver, people around you are talking while you’re drugged. And the craziness of discovering systems that you are either a victim of or you have to figure out how to defend yourself against. Not to mention a whole new vocabulary you learn.

“I’ve met people who, when diagnosed with cancer, kind of isolate themselves and live at home quietly and some who sadly get really angry and stay angry until they die. And to me dancing with cancer has not been like that. I was angry the first weekend before the biopsy results came back. That was the weekend when I fired God and hired HER back a couple times. But then I got over that because I’ve always believed that in every trauma there’s some kind of a grace at work and you just have to open yourself to it and figure out what it is. It doesn’t make you a better person, but it says, Wait, stop, who do you really want to be? And, so, cancer gives you some time, mostly, to do that and that’s a great privilege. I mean, I think it would be a great privilege to drop dead of a heart attack, but it wouldn’t be for your family because it’s so traumatic.”

Her decision to have her odyssey filmed was one she came to after much thought. “It took a long time to decide what my motives were here. Was I just doing this out of ego? Was it really a good idea? I talked to a lot of friends about it before I talked to my family. Most of my friends said, ‘Oh, yeah, you better do this because it will give you something to keep you busy.’ My kids in the beginning were thinking what it would be like to have somebody around filming during the last week of my life. I wasn’t thinking about that at all. I was thinking about talking about the things that happened to me in terms of my cancer, but also in terms of how the cancer affects my life and the stories. So, finally, I think my kids have all come around to it.”

Storytelling, she said, constitutes the way we make sense of things. The story of her cancer and dying, she said, is “no different. Every time you narratize your story to explain something to yourself, that’s healing, because then you’re no longer so confused or befuddled by it. Then, when you tell it to somebody, they give it their own meaning based on their lives.” This search for identity and meaning is one she thinks America suppresses in its instant gratification apparatus.

“I think all my work with storytelling has been trying to fight that tendency in our culture that does everything to avoid having people talking deeply to each other, especially about death or anything important. As a society, we want to be entertained and we avoid things that might make ask us to think or deal with situations going on in the world. Problems are not going to get solved until we sit down with somebody else and really listen to their stories, so we can get to understand each other rather than blowing each other up. The more we put labels on people, the more we’re destined not to know them. When you really know somebody’s else’s story, you can’t hate them anymore. It’s a wonderful tool for peace,” said Duncan, whose residencies in schools and other settings have used storytelling to break down barriers, to build self-esteem and to promote diversity.

“But nobody trusts it (storytelling), partially because nobody has ever listened to our stories. We narrow ourselves so much by not knowing each other. Storytelling works against that. That’s why I keep working on storytelling.”

She said too many of us seek the cold isolation of mass media diversions as substitutes for interpersonal communication around the dinner table or fireplace, where gathering with friends to talk and tell stories is a communal event and a celebration of our shared humanity. “That’s what storytelling is all about.”

Harry Duncan

Her many tales, from the repertoire of “platform” stories she’s crafted for performance to the private stories she’s passed on to loved ones, are sure to live on through her family members, all of whom, she said, are born storytellers. That’s why her dying is more celebration than requiem. “Not only is it a celebration,” she said, “it’s a transition. It’s a very important transition from my versions of the stories to everybody else’s. Now, they’re all going to own these stories. I would love to someday eavesdrop on them, although that’s probably not possible.” Her performance stories are available on CD.

Duncan’s love for stories extends back to childhood. Born in Indiana to “depressed-alcoholic” parents, she did most of her growing up in Illinois and Georgia. A tomboy with a big imagination, Duncan roamed the woods in back of her Georgia house to act out the dramas in her mind. It was her pipe-smoking grandma, with whom she shared a room and found refuge with for eight years, that introduced literature and storytelling to her. “She read books to me until she dropped. She was not a big talker, but she told very well-honed stories all about her life. She was the unconditional loving parent in my life and my rock of stability,” Duncan said. “If I hadn’t of had my grandmother, I think I would have ended up in a booby hatch.”

Expressive by nature, Duncan first heeded her talents as a writer, earning a scholarship to the prestigious University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1958. It was there, as a student, she met and married Harry, then a teacher and fine arts press director. Eventually, she and Harry moved to Omaha, where he ran the Abattoir Press at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. She acted on area stages and served as associate director of the Omaha Community Playhouse and as artistic director and, later, executive director of the Emmy Gifford Children’s Theater (now the Omaha Theater Company for Young People).

She applied drama techniques to her early storytelling. She built her signature story performances around Baba Yaga, a witch character adapted from Russian literature, and a chicken. “Baba Yaga was really the one who broke me open because she could say anything,” Duncan said. During the Fundamentalist Right’s rise to power, Baba Yaga got her in hot water with some area school districts that outright banned or picketed her shows. She was even spat at once.

Dissatisfied with her hybrid of theater and storytelling, Duncan began shedding makeup and costume to explore and expose more of herself on stage. Once she made herself more present in her increasingly personal stories, she found her voice as a teller. She never looked back at the theater, which she found limiting. “In the theater, you’re really not in charge of the material. The playwright or director is. In storytelling, there’s no separation of yourself from the story. You have to take total responsibility for it. You can’t blame it on the writer or director. It’s a different kind of bareness-nakedness, but also a different kind of responsibility.”

Speaking of responsibility, she hopes her militant views on cancer increase awareness. It’s why she doesn’t wear a wig or a prosthesis. “We need not hide the fact this is happening. If we hide the fact we have cancer…we’re denying who we are. We’re also making it easier for others to get it because we’re doing nothing to prevent it,” she said. “I hope my actions draw attention to the fact there is breast cancer in the world and that we need to do something to cure it. Moreover, we need to prevent it. Hiding it, to me, says the opposite. That it doesn’t exist. Instead, we need to let women know, You have a job to do.” She said many women don’t self-examine or are afraid to. Why? “They don’t want to know.”

Duncan’s curiosity, passion, concern and whimsy have made her a timeless teller and, when she’s gone, her life and work will endure as a never-ending story.

Related Articles

- Tall tales: Meet the storytellers spinning edgy new yarns for the digital age (independent.co.uk)

- Healing with Story: Healing the Storyteller (health-psychology.suite101.com)