Archive

Leo Adam Biga’s Journey in the Pipeline; Following The Champ, Terence “Bud” Crawford in Africa

Leo Adam Biga’s Journey in the Pipeline; Following The Champ, Terence “Bud” Crawford, in Africa

This is the first time i’ve posted the stories I wrote about my travels to Africa with boxing champ Terence “Bud’ Crawford just as they appeared in Metro Magazine (http://www.spiritofomaha.com/Metro-Magazine/The-Magazine/). The publisher and editor generously allotted several pages to this rather epic spread highlighting various facets of the two-week trip to Uganda and Rwanda.

NOTE: As originally presented for publication in metroMAGAZINE/mQUARTERLY August 2015 edition.

©by Leo Adam Biga

BTW: My blog features many other stories I’ve written about Crawford.

The Champ looks to impact more youth at his B&B Boxing Academy; Building campaign for Terence Crawford’s gym has goal of $1.2 million for repairs, renovations, expansion

Here is some of my latest writing on Omaha’s own two-time world boxing champion, Terence “Bud” Crawford, this time centered around the $1.2 million buidling campaign to make much needed repairs and renovations and to do much needed expansion to his B&B Boxing Academy. The Champ and his friends have a beauiful vision in mind for the academy. See the renderings for the new and improved facility below and read about the heart Crawford has for his community and the role he sees his center playing in being a positive force for youth and young adults. And meet some of the members who train at B&B.

The Champ looks to impact more youth at his B&B Boxing Academy

Building campaign for Terence Crawford’s gym has goal of $1.2 million for repairs, renovations, expansion

©by Leo Adam Biga

Two-time world boxing champion Terence “Bud” Crawford is putting Omaha on the map with the title bouts he brings here, but he also hopes to steer attention to his B&B Boxing Academy.

The fight world’s focus will once again be on Omaha when Crawford defends his WBO junior welterweight title October 24 at the CenturyLink Center. The Champ wants people to know his roots extend far beyond the fights he has in Omaha to include his nonprofit gym serving youth and young adults in his hometown.

Located at 3034 Sprague Street in a former cold storage warehouse in the very neighborhood he grew up in, B&B is a nonprofit, community-based athletic center with a mission of building body, mind and character. Experienced coaches help members reach goals inside and outside the ring. Positive, structured activities teach confidence, discipline and healthy habits for a lifetime. Crawford started the gym with co-manager Brian “BoMac” McIntyre as a safe haven from the negative street influences that compete for young people’s attention. When Crawford isn’t away training, he and McIntyre are there at B&B, rubbing shoulders with the mix of amateur fighters who frequent it.

But the building housing the gym is in need of total renovation. Antiquated electrical, heating and plumbing fixtures need replacing. There’s no locker room. The single bathroom is shared by males and females. Because the roof leaks, the only thing keeping the Champ and others dry are tarps affixed to the ceiling. The walls leak, too.

Meanwhile, the gym’s reached physical capacity. On warm summer nights the place overflows with members going through their paces – running, working the bags, shadow boxing, sparring. To accommodate the overflow, the doors and fences are opened and the parking lot emptied to create a makeshift outdoor training site. If the numbers keep growing as expected members will need to train in shifts.All of this is prompting friends of the B&B to support a building campaign with a goal of $1.2 million to address the structural needs.

Omaha entrepreneur Willy Theisen is among those supporters.

“Terence and his gym have a true positive impact and he’s committed to B&B,” Theisen said. “He and Brian and the other coaches there do a great job of building champions but I think we must do better as far as the facility goes. We come from a very generous community that gives back and that pays ahead and I think we can get this thing done. A newly renovated building will help Terence and B&B have an even greater impact on the neighborhood and community.”

Currently B&B is only using a fraction of the available space. The vision is to convert the entire warehouse into a spacious, state-of-the-art gym that can also host community events. It is a huge undertaking.

The newly outfitted gym will add a second ring, more punching bags, new exercise equipment, a dedicated fitness-weight training room, meeting-activity spaces and offices. The renovations will also include boys and girls locker rooms and showers, and a community outreach kitchen that can be used for serving meals to the kids as well as hosting special events.

Friends of B&B such as Theisen, along with B&B Advisory Committee members Jamie Nollette Kenneth Patry, Jay R. Lerner, Jason Caskey and Garth Glissman, invite people to help build a gym and give youth a fighting a chance.

For donation inquiries, contact campaign manager Jamie Nollette at jnollette@pipelineworldwide.org or (623) 824-3273.

My travels in Uganda and Rwanda, Africa with Pipeline Worldwide’s Jamie Fox Nollette, Terence Crawford and Co.

Here is my second published story about the Africa trip I made with a group of folks with Omaha ties, including two-time world boxing champion Terence “Bud” Crawford and his former teacher at Skinner Magnet School, Jamie Fox Nollette. This story in the August-September-October issue of Metro Magazine (http://www.spiritofomaha.com/Metro-Magazine/The-Magazine/) is a more comprehensive, overarching look at that experience than the piece I did for The Reader (www.thereader.com).

At the conclusion of this story is some expanded material explaining the impetus for my going to Africa, namely Terence Crawford, including more insight into him, his motivation for going, his relationship with Nollette, and how he wants to help people there and right back here in his hometown of Omaha, where he makes his home and has his B & B Boxing Academy.

My travels to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa were made possible by the Andy Award grant for international journalism I received from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. My reporting is meant to raise the global awareness of Nebraskans.

AFRICA TALES IN IMAGES

Here is a link to a video slideshow of the June trip I made to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa with The Champ, Terence Crawford and Alindra I Person, Jamie Fox Nollette, Scott Katskee, Joseph Sutter and Julia Brown

The visuals were edited, set to music, given movement and in some cases captioned by my friend Victoria White, an Omaha filmmaker.

NOTE: I am available to make public presentations about the trip and the video slideshow will be a part of the talk that I give. We will be updating the video slideshow with new images to keep it fresh and to represent different aspects of the experience we had in those developing nations.

My stories about the trip can be accessed at-

https://leoadambiga.com/?s=africa

My impetus for going to Africa – Terence Crawford – and what you should know about him and his heart for people

©by Leo Adam Biga

Two-time world champion follows his ex-teacher to Africa

The Champ goes to Uganda and Rwanda twice in a year

Setting the stage

I have followed hometown hero prizefighter Terence “Bud” Crawford for two years. In that short span he’s become a transcendent figure whose personal story of rising to the top transfixes anyone who hears it, regardless of whether they follow boxing or not.

His notoriety cuts across race and class rivals if not surpasses that of Neb.’s most decorated homegrown athletes. Among in-state natives, he just may be the most dominant in his sport since Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson was in his prime with the St. Louis Cardinals nearly a half-century ago.

It never occurred to me I would go to Africa to cover Crawford. I mean, I could see myself going to another state to report on one of his fights or visiting his training camp in Colorado Springs. But Africa? Not a chance.

Only I did go – to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa of all places.

My Global Awareness – Journeys chronicle in Metro Magazine is a compendium of that June 1-12 trip. The fighter is not particularly featured in that piece because the trip wasn’t about him. But as I would never have gone there were it not for him, I find it necessary to share here more about the young man who has so captivated us. I also share why making that journey at this juncture of his career is such a compelling part of his story.

So much of Crawford’s tale reads like a novel or screenplay. During his hard-knock growing up in the inner city, street fights and pickup games were a rite-of-passage and proving ground. His formal training began at the CW Boxing Club, where right from the start he showed great promise and dreamed of winning titles. An outstanding if frustrating amateur career saw him lose a controversial bout in the National Golden Gloves finals in Omaha.

He nearly lost his professional fight career and life when he suffered a gunshot wound to the head. His rise up the pro ladder happened in relative obscurity and outside the view of his homes until his amazing 2014 run. He won the WBO lightweight title in Scotland and defended it twice before huge crowds in his hometown. He began 2015 by winning a second world title in Texas. Now he’s in line to fight the sport’s biggest names for mega bucks.

Lots of honors have come his way:

•Named WBO Fighter of the Year

•Named Boxing Writers Association of America Fighter of the Year •Inducted into the Omaha Sports Hall of Fame

•Inducted into the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame

•Likeness added to Omaha Press Club’s Face on the Barroom Floor

•Made the cover of Ring Magazine

•Immortalized in a mobile mural by artist Aaryon Lau Rance Williams

All by age 27

He also his own gym, B & B Boxing Academy, where his Team Crawford works with promising amateur and pro fighters. It’s right in the neighborhood he came up in. He’s a family man, too, who shares a home with his girlfriend and their four children.

Then there’s the whole story behind why he went to Africa and who

he went with. It involves his fourth grade teacher at Skinner Magnet School in North Omaha, Jamie Fox Nollette, whose Pipeline Worldwide supports sustainability and self-sufficiency projects and programs in those nations. Pipeline also works in Ghana, Africa and in India.

The trip to Africa I joined Crawford and Nollette on was actually their second together there. When I learned that first trip had nothing to do with boxing. it peaked my interest, as it suggested a depth to the man I hadn’t considered before. His relationship with Nollette added a whole new dimension to his story.

Tellingly, another elementary school teacher who made an impression upon him, Sheila Tapscott, is also still in his life.

Upon finding out The Champ was going again with Nollette, I found the opportunity and means to tag along.

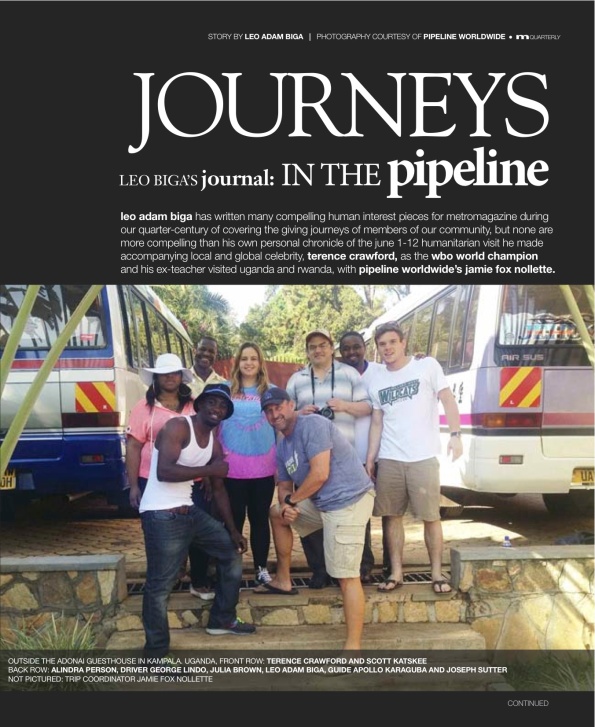

I flew out of Omaha with Crawford and his girlfriend Alindra “Esha” Person, who’s the mother of his children. Jospeh Sutter joined us as well. In Detroit we caught up with Julia Brown of Phoenix. Next onto Amsterdam, The Netherlands, where we met Scott Katskee, an Omaha native now living in L.A. From there we flew to our final destination, Entebbe, Uganda, where Nollette. who’d left the States a day earlier, met us.

In Country

After witnessing the want, the hope, the beauty, the despair of Uganda and Rwanda, I found there’s much more to Crawford than meets the eye. I found a man of contradiction and conflict, whose language and behavior can be inappropriate one minute and sensitive the next. He’s a big kid with a lot of growing up to do in some ways and wise beyond his years in other ways. His nonchalance masks a reservoir of deep feelings he doesn’t like showing.

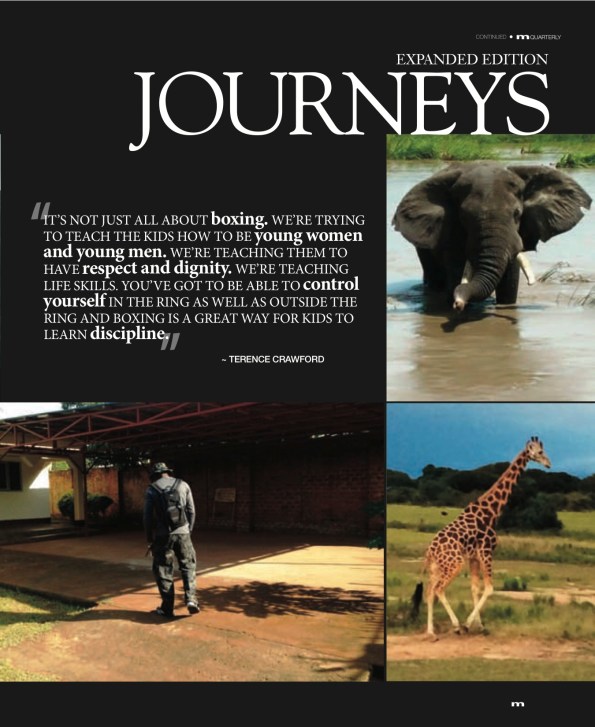

No matter where he is, even Africa, The Hood is never far from him. But he’s not too tough or cool to admit Africa touched him.

“It’s life-changing when you get to go over there and help people,” he told me. “It just made me appreciate things more. It kind of humbled me in a way to where I don’t want to take anything for granted. I haven’t in my life experienced anything of the nature they’re experiencing over there. For one thing, I have clean water – they don’t have clean water. That’s one of their biggest issues and I want to help them with it.

“They appreciate everything, even if it’s just a hug or a handshake.”

On his first visit he gave away all his clothes except for those on his back and on this last trip he gave away many T-shirts and other items. Last fall he paid for Pipeline’s Ugandan guide, Apollo Karaguba, to fly to America to see him fight and to celebrate Thanksgiving with Nollette’s family.

On the trip I made I saw Crawford interact with locals every chance he got. In Uganda he kidded with Apollo and our driver George, he haggled with vendors, he traded quips with noted Catholic nun Sister Rosemary, he played with children and he coaxed young women to dance to music he played. It was much the same in Rwanda, where he joked with our guide Christophe, danced with pygmies and entertained kids by throwing frisbees, doing backflips and handing out gifts.

He also enjoyed the hike, the safari and the gorilla trek that put our group on intimate terms with the wild.

Though clearly a public figure, Crawford rarely made himself the center of attention or acted the celebrity. He was just another member of our group. The few times he was recognized he obliged people with autographs or photo ops. The one special event set aside for him, a Uganda press conference, found sports ministry officials rolling out the red carpet for him. You see, boxing is big in Uganda and his visit constituted a big moment for Ugandans.

As usual, he took it all in stride. Nothing seems to rattle him.

Boxing as change agent

He touts his sport as a vehicle for steering inner city kids away from the mess many face. He even shared that message with sports ministry folks, boxers and reporters at the press conference.

“Boxing took me to another place in my life where I could get away from all the negativity,” he said. “I got shot in my head in 2008 hanging out with the wrong crowd. At that time I knew I just wanted to do more with my life, so I started really pursuing my boxing career.”

He emphasized the “hard work” it took to get where he is. The boxers hung on his every word.

“Every day, any boxing I could watch, I would watch. I would take time out to study, like it was school. I would tell you to just work hard, stay dedicated, give your all every time you go in there and who knows maybe you can be the next champion of the world.”

He emphasized how much motivation and work it takes to be great.

“There’s going to be days you want to quit. Those are the days you’ve got to work the hardest. I never was given anything. I was one of those kids they said was never going to make it – I used that as an opportunity to prove them wrong.”

Crawford handled himself well in that setting, He answered all their questions, posed for pictures, signed things and made everyone feel special.

In an interview with me, he spoke about his gym and his wanting to make it a sanctuary to get kids off the streets..

Show me that you care

“It’s not just all about boxing. We’re trying to teach the kids how to be young women and young men. We’re teaching them to have respect and dignity. We’re teaching life skills. You’ve got to be able to control yourself in the ring as well as outside the ring and boxing is a great way for kids to learn discipline.

“If they feel like nobody cares than they’re not gong to care, but if they feel one person cares than they tend to listen to that person.”

Crawford knows from personal experience what a difference one person can make. Nollette was among those who connected with him when he was a hard-headed kid who bristled at authority.

“She was one of the only teachers that really cared. She would talk to me,” he said.

He needed someone to listen, he said, because “I got kicked out of school so much – a fight here, a fight there, I just always had that chip on my shoulder.” Nollette took the time to find out why he acted out.

He knows, too, the difference a gym can make for a young person working out anger issues.

“It’s a good place to come and get away, release some stress, release some steam if you’re having problems at home or school and you just need to let it out. What better way to let it out than on a bag, rather than going somewhere else and letting it out the wrong way. I look at it as an outlet for the kids that are just hardcore and mad at the world because of their circumstances. They come to this gym and they feel loved and they feel a part of something. For some kids, feeling a part of something changes them around.”

“This is my community, B & B is my gym, so I am in it for the long haul. I’m not in it for the fame or anything like that. I could be anywhere but my heart is with Omaha. We just want to help as many kids as we can. Everything is for the kids.”

Carl Washington got him started in the sport at the CW, where Midge Minor became his coach. Minor’s still in his camp 20 years later.

Crawford hopes that some young people training at the B & B will one day take it over. Then they, too, will pay forward what they received to help a new generation of young people.

Each one, to teach one…

The gym is in a neighborhood plagued by violence. His own childhood mirrored that of kids living there today. It’s survival of the fittest. He got suspended and expelled from school. The lure and threat of gangs loomed large. Boxing became his way out.

Staying true to his roots

His is a classic American success story of someone coming from the bottom up and making it to the top.

He’s fast become an icon and inspiration. He’s singlehandedly put Omaha on the boxing map and revived what was a dead sport here. HBO and TopRank are grooming him as pro boxing’s hot new face. Warren Buffett’s sported a Team Crawford T-shirt at one of his Omaha bouts. The fighter shows his hometown love by wearing trunks and caps with Husker and Omaha insignias. He’s thrown out the first pitch at an Omaha Storm Chasers’ game. He makes personal appearances delivering positive messages to students and athletes.

Amidst all the fame and hoopla, he’s remained rooted in his community. Yet he’s also found time to expand his world view by twice going to Third World countries when he could have chosen some resort. He considers Africa his second home.

“It IS home. I’m AFRICAN-American. It’s where a lot of my people come from historically down the line of my ancestors. Damn, I love this place.“

Just like his first visit there, he said, “I was very touched by the people and how gracious and humble and thankful they were about everything that came towards them. I had a great time with great people. I experienced some great things.”

As someone who prides himself in being a man of his word, he was pleased when Africans expressed appreciation for his not only saying he’d be back after his last trip, but actually returning.

The fact that he’s retained the same coaches and trainers who have been with him for years and that he supports his ex-teacher’s work in Africa speaks to his loyalty. What he gives, he gets back, too, thus making him a beloved star athlete and role model to the people and community he calls his own.

He hasn’t forgotten where he comes from and I doubt he’ll ever forget Africa. We don’t have much in common other than the same North Omaha roots, but the shared experience of seeing Uganda and Rwanda is something we’ll always have between us. That, and having the privilege of writing about the experience, is enough for me.

I never expected to be in Africa, let alone with him, but I’m glad it worked out that way.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com.

_______________________________________________________

My travels in Uganda and Rwanda, Africa with Pipeline Worldwide’s Jamie Fox Nollette. Terence Crawford and Co.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Nebraskans connect with Africans on trip

A chronicle of the June 1-12 humanitarian visit The Champ and his ex-teacher made to developing nations

I never imagined my first venture outside the United States would be in Africa. But in June I found myself in the neighboring East African nations of Uganda and Rwanda as the 2015 winner of the Andy Award for international journalism from the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

I accompanied a small group under the auspices of Pipeline Worldwide, a charitable organization with strong Omaha ties. The nonprofit supports sustainable clean water projects as well as self-sufficiency programs for vulnerable youth and women.

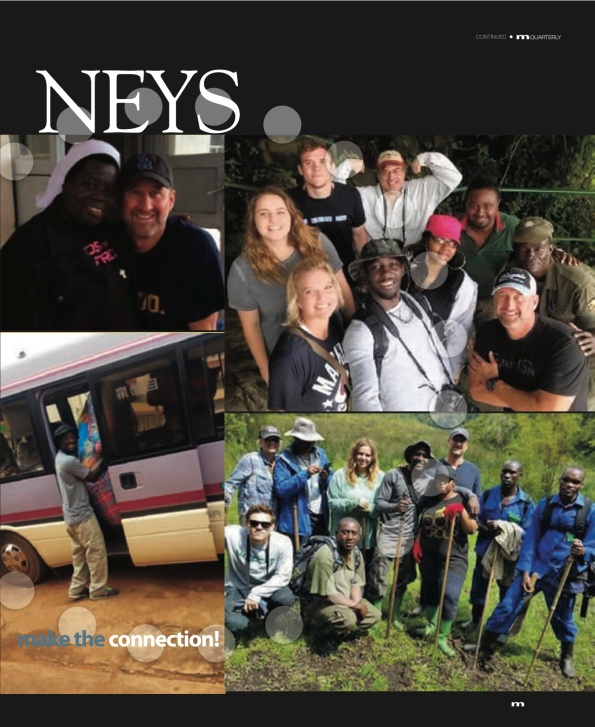

Pipeline co-founder and executive director Jamie Fox Nollette, an Omaha native, goes three times a year to check progress, assess needs and meet partners. She also raises awareness by bringing folks over and documenting the visits for prospective donors. She’s among scores of Americans, including Nebraskans, serving Third World countries. Though secular, Pipeline partners with faith-based groups. Her passion for serving Africa began with a 2007 church mission trip there.

She was Mother Hen for the trip I made.

Our ranks included a star – two-time world boxing champion Terence “Bud” Crawford of Omaha – who’s perhaps the most accomplished Neb. athlete in my lifetime.

Despite being a newsmaker, his visits to Uganda and Rwanda last August with Nollette went under the radar. It’s the way he wanted it. He’s low-key, even nonchalant about what he does to broaden his mind, see the world and help his community.

He doesn’t want to be thought of as just a fighter, though.

“I’m a human being just like anyone else,” he said,

You may wonder what compelled this 27 year-old at the top of his game to go, not once but twice, to developing nations beset by poverty, infrastructure gaps and violent legacies when he has the means to go anywhere. Well, it turns out Nollette was his fourth grade teacher at Skinner Magnet School in North Omaha, where they bonded, and they still click today.

He was a hard-headed kid from the streets carrying “a chip on my shoulder.” She was a calming influence at school, where he often acted out, except not in her classroom.

He and Nollette, who lives in Phoenix, Arizona, reconnected in 2014. She’d followed his prizefight success from afar and reached out to congratulate him.

“I told him how proud I was of him,” Nollette said.

When he discovered she did work in Africa he asked her to take him to the “motherland” he feels an ancestral draw to.

Traveling there also feeds Crawford’s heart for people less well off than himself, especially children. His generosity’s well-known. Crawford supports Pipeline’s work by bringing attention to it – he’s headlined fundraisers in Omaha and Phoenix – and she supports his B & B Boxing Academy. She’s leading a capital drive to expand the facility so it can serve more youth.

Loyalty is important to him. The coaches and trainers in his Team Crawford camp have been with him for years.

His “trust” in Nollette as someone who’s got his best interests at heart is reciprocated by him having her back.

After learning their shared history, their having gone to Africa and their planning to return, I applied for the grant to fund my Africa travel. That’s how I ended up half way around the world with a boxing star and a humanitarian.

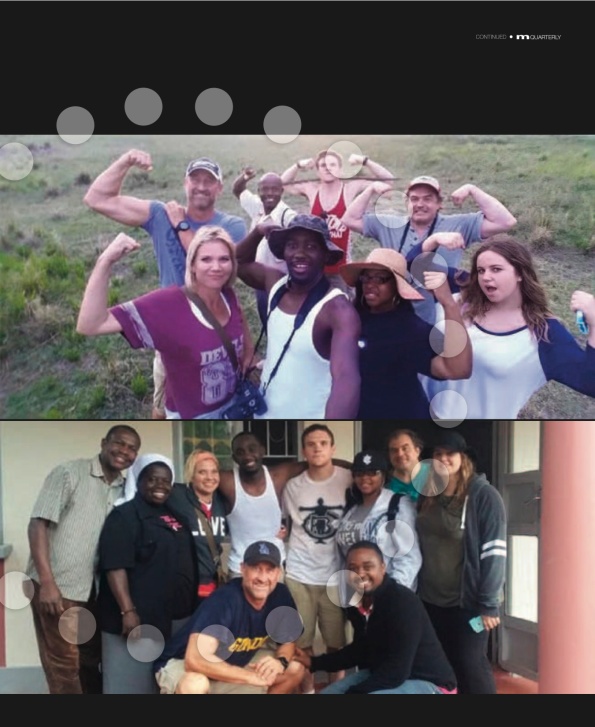

Our merry band in far distant lands

However, those two weren’t the whole story. We were a diverse seven-member group all affected by the places we went, the people we met and the stories we heard. The experience stretched us in new directions and offered new perspectives.

Nollette, our laidback leader, encouraged us to appreciate the human dimensions of what we witnessed as active participants,

Crawford, our by turns stoic and silly star, traveled with his girlfriend and the mother of his children, Alindra “Esha” Person.

Person, who’s a match for her man, expressed fears about the trip but proved a real trouper. Like her mate, she has a soft spot for kids and loved on them every chance she got.

Scott Katskee, an international apparel entrepreneur originally from Omaha and now living in L.A.,, is a big, gregarious, inquisitive man with a blend of street smarts and sophistication.

Joseph Sutter, a 2015 Millard West graduate, loved being in the company of his idol, Crawford, whom he played sidekick to.

Julia Brown, a recent Phoenix-area high school grad, didn’t say much but her heart for children shined through.

That left me capturing Africa’s contrasting tableaux. Traveling by mini-bus and land cruiser, we bounced from urban to rural areas and back again, often via heavily rutted dirt roads.

Busy, jam-packed cities gave way to sleepy rural spots. Hours of open plains followed by winding hilly terrain. I’ll never forget the beauty and power of hiking Murchison Falls or the wonder of being on safari and coming up on two lion prides. Roadside shanties sometimes sprawled only a stone’s throw from gated communities and luxury hotels.

Nollette said there’s no substitute for going to remote regions and urban slums “if you really want to see how people live.”

Sights that stick in my mind:

Vendors hawking wares.

Workers tending fields.

Farm animals foraging in front of homes.

Boda boda (motorbike) drivers darting through traffic.

Sounds too:

Roosters waking us in the morning.

Cawing birds.

Children singing, drumming, laughing.

Catholic Mass celebrated in Latin, English and Swahili.

We’re not in Nebraska any longer

As fellow travelers we shared something potent together we won’t soon forget. Our June 1-12 journey was an odyssey for all, even those with extensive international experience. For this virgin globe-trotter it constituted an outside-the-box leap of faith.

Nollete described what the trip demanded and gave.

“These trips are hard, We are all away from home, out of our comfort zones – some way more than others. Not in control, thrown in a group with people we do not really know and usually would not try to get to know. We eat different, sleep less and see some really impactful things we’re not sure what to do with. That creates some dynamic situations. My hope is people come and see some things that are new, feel something different and learn not only about the countries and people but about themselves.

“Being out of control, uncomfortable and in new surroundings can foster growth. That’s not what people sign up for but most people will probably admit they experience some sort of transformation.”

I don’t know yet how I’ve grown from this, except perhaps I’m more patient and tolerant.

It’s important to note I went as an innocent abroad. Going in, I knew little about Uganda and Rwanda and after being there only 10 days I don’t pretend to be an expert. Our itinerary revealed different sides of those nations, but they were just snapshots of complex societies and cultures.

My greatest takeaway from Africa is its immense resources and challenges, which equates to vast unmet potential. As Nollette pointed out, the people want the same things we do but the barriers to entry for Western-standard living are steep. These are developing nations in every sense. Folks trying to improve things there measure progress in small steps that might seem insignificant to us but make a big difference in people’s lives.

On the flight from Amsterdam to Uganda I sat next to medical anthropologist and linguist Anna Eisenstein, a University of Virginia doctoral student doing field work in southwest Uganda. She lives with a village family and as she builds relationships with locals she conducts interviews. Her explanation of her work lent insight into the world I was entering:

“I’m studying the way people think about their bodies, how they think about health care and how they make decisions about when to go to the healer or the herbalist or when to go to the public health system. If they’re going to see a healer their family knows, it looks very different than going to the public hospital. If people are coming out of an encounter with bio-medicine rooted in colonialism then they have a lot of reason not to trust doctors or to take pills or want to be proactive. Also the public health system functions in English, which can be a barrier as well.”

Her comments stuck with me during my stay in Uganda, where vestiges of colonial rule persist.

She also told me what I could expect from the people.

“Everyone I’ve met has been so welcoming and friendly and kind and I hope you’ll find the same. There’s a lot of emphasis on hospitality and on making others feel welcome.”

Indeed, we came face to face with warm hospitality wherever we went. In Kampala, cancer-stricken children and their mothers at Bless a Child welcomed us with sweet formality. Sports ministry officials treated us like VIPs owing to the presence of The Champ, whom they greeted like a returning prince. In Atiak. a region of northern Uganda, young women recovering from trauma honored us with a rousing tribal dance and a hearty meal in appreciation for our group outfitting their newly dedicated dorm with bedding. Their sweet sisterhood enchanted us. In Luwero trainees at the African Hospitality Institute prepared a gourmet feast for us.

In the Rwanda highlands, pygmy village residents performed a traditional dance we reciprocated in kind.

We were welcomed into homes with mud walls, a thatched roof and bare possessions. When we visited organizations staff eagerly showed us classrooms, nurseries, clinics, guest houses and residential units. In many areas, access to clean water is an ever-present issue. The presence of a working community well or tank or pipe is cause for celebration. All too often rural folk must travel distances by foot or bike or boda boda lugging plastic yellow Jerry cans to fetch or return water. Without any or reliable home refrigeration, people shop at outdoor markets to supplement daily food needs subsistence farming doesn’t provide. Wooden stalls overladen with fruit, vegetables, oils, spices, grains, meat and fish do a brisk business as do their equivalent piled high with clothes, bags, tools, electronics. In slums, where there’s no sanitation system, human refuse runs free when the rains come.

I left feeling humbled by the scale of need and grateful for my own good fortune.

This impressionistic account dispenses with chronology in favor of moments and individuals that impressed me. My hope is you’ll find something that sparks your own journey or quest.

Getting to know you: Partners

I barely knew Nollette before the trip. I soon saw her dedication is sincere. She’s learned lessons in eight years serving Africa, none more vital than finding the right people on the ground to work with. She introduced us to several Pipeline partners in Uganda she’s close to. Ben Kibumba with Come Let’s Dance, Richard Kirabira with Chicken City Farms and Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe at Saint Monica’s. They lead efforts to educate, train and employ locals, no small feat in places where poverty and unemployment are widespread and opportunity limited. Adding to the challenge are transportation issues, resource shortages, misappropriated aid monies and emotional scars from civil war (Uganda) and genocide (Rwanda).

“Partnerships and relationships are crucial,” Nollette said. “It is very difficult to manage projects overseas. Since there is a great deal of corruption, you have to develop trust. Once we’ve identified potential partners with strong leadership, we start slow with small projects. We see how they do with communication, execution and accountability. We don’t expect them to be perfect. Many organizations we work with are grassroots just like us, but we believe in their vision and leadership. We emphasize collaboration and problem solving.

“It’s so hard here to try and do things on your own.”

Nollette cultivates leaders and facilitates their networking together. At one stop she presented partners with Samsung Galaxy tablets so they can better communicate-coordinate with each other and do better project management.

“They’re all great leaders. The cool part is these guys are now collaborating.”

Networking helps Pipeline track projects and programs. Pipeline is a conduit feeding the change agents it supports with what they need. Sometimes that means connecting partners.

Nollette said, “For example, Richard with Chicken City Farms has figured out brick making using a brick making machine with interlocking bricks. It can cut the cost of construction by 30 percent because it doesn’t require as much cement. We introduced him to Sister Rosemary and Ben Kibumba. Richard’s team is training Sister Rosemary’s and Ben’s teams on this process by building guesthouses for them. Not only will they learn this new skill that cuts costs, but they can continue to make bricks and sell them as an additional revenue stream.”

Leveraging expertise and resources, Pipeline strives to create synergies for sustainable change.

Nollette said it takes time to fully discern needs and challenges and get people thinking longterm.

“I’ve learned many Africans want to withhold information for fear the support may go away. They also tend to think about immediate fixes rather than long-term solutions. When most people wake up each day and have to walk for water and get food for the day, it is difficult to think beyond that. We talk a lot about solutions that are sustainable.”

Two of her most trusted liaisons are Apollo Karaguba in Uganda and Christophe Mbonyyingabo in Rwanda. Besides serving as our tour guides, they took us to programs serving residents of urban slums and isolated rural villages. Pipeline partners with Apollo’s employer, Watoto Child Care Ministries, and with Christophe’s own CARSA.

Nollette sings the praises of Apollo and Christophe, two affable men with burning intensity.

“I’m mostly impressed with their passion and commitment to make a difference in the lives of others. I can count on them for anything and truly think of them as brothers. It’s an honor to work with them. They are also eager to listen and learn and help with other projects even when it doesn’t benefit their own organizations.”

She and her family are especially close to Apollo, who in turn is close to Terence Crawford.

“I feel like I’ve adopted both of them,” she says of the guide and the boxer.

Nollette’s brother is financially helping Apollo and his two siblings finish their university studies. When Crawford hit it off with Apollo on his first Africa visit, he flew him to America to watch his Nov. lightweight title fight defense in Omaha. Apollo enjoyed Thanksgiving dinner with Nollette’s extended family. A friend and associate of Apollo’s, George Lingo, was our driver in Uganda. Pipeline is helping pay for one of his son’s studies.

Apollo’s employer, Watoto, houses and educates orphaned children in Uganda, where soaring teen pregnancy and poverty create a crisis of abandoned youth. We met boys living in a Watoto family-style home. Each home has a maternal caregiver and her own children. The caregiver is mother to them all.

Three of the boys we met stayed with Nollette and her family in Phoenix when traveling to perform in a Watoto choir last year. She’s attached to one of them, Peter. He and his buddies joined us for dinner one night and Peter, who spent part of a bus ride next to Nollette, didn’t want to return to Watoto that night.

“It was particularly painful when Peter asked me if they could stay the night and if he could have more time with me,” she recalled. “It reminded me again that everything matters. Even If it doesn’t seem like much, it has huge impact. All Peter wants is my time and love – something so easily given.”

The attention he craved reminded her of The Champ at that age. Crawford was a handful in school but never gave Nollette grief as he found in her a caring, compassionate teacher.

“I remember Terence saying the same thing to me on our last trip back in August. I asked him why he didn’t get into trouble in my class and he said it’s because he knew that I cared about him. Some things we do, it’s hard to measure the impact.”

People helping people

Ben Kibumba, like many Pipeline partners, escaped the same dire straits of poverty and homelessness as the children that his Come Let’s Dance (CLD) serves through its school, clinic, farm and housing. He’s learned you can only move people forward when their basic needs are met.

“You can’t dream when you’re hungry,” he said. “When you’re fed, you can dream of things bigger.”

CLD’s Thread of Life program targets single mothers in the slums, some of whom who turn to prostitution to get by. Others can’t afford sending their kids to school. Thread of Life gives women a safe place to live and the opportunity to learn sewing-beading skills they use to make jewelry and apparel whose sales earn them a living wage.

Program directors Mercy and Florence say some participants have left behind exploitation and dependence to move out of the slums and live healthy lives with their kids.

Pipeline supports this and similar programs that train and employ African women to sew. Nollette’s also launched a business, C ME Stories (http://cmestories.com/), where U.S. designers create patterns for apparel-accessory products women in Uganda produce.

“We pay women for each piece they make. The idea is to have a recurring business model and pay women a good wage for the work they do. They learn to save as well,” Nollette said.

At her Saint Monica facilities in Gulu and Atiak, Uganda world renown humanitarian Sister Rosemary and staff empower exploited females, who are trained and employed in sewing and beading. Many were abducted as girls by rebels and forced into sex slavery, marriage and childbirth. Through education, community and work, they build self-esteem and self-reliance.

“She’s my type of person,” Nollette said of the charismatic nun. “She’s a problem-solver and knows how to get things done. One of the things she said to me was, ‘You know Jamie, we understand how to do all the little things that turn into big things.’ She loves those women and it shows. Her work is incredibly difficult and yet she is always fun to be around. Contagious is the best word to describe her.”

About the women at Saint Monica’s. Sister said, “They’ve seen a lot of bad stuff. That’s why it’s good to get a lot of people who can come and show them a different face of the world. If they remain by themselves they will not know anything else.”

A shy resident she introduced us to, Evelyn Amony, was abducted by Lord’s Resistance Army rebels at age 12 on her way to school and like other taken girls forced to do and witness awful things. She became one of LRA leader Joseph Kony’s many wives and bore him three children. She lived in hiding with him until the Uganda army intervened.

Since regaining her freedom, she said, “I find a lot of improvements and changes in my life.” Amony said she enjoys the work she does and the pleasure it gives others. As if to prove it she modeled a blouse she makes and designs, too. She smiled as we admired her handiwork.

Nollette said, “When you empower women to be able to actually support themselves and to be able to pay for their kids’ schooling it’s really important. When a mom is able to afford to send her own child to school it teaches the value of education.”

Giving people the means to break cycles of misery and achieve self-sufficiency is a big focus of Pipeline and its partners. In his own way, Crawford tries doing the same thing at his gym.

Charles Mugabi and Richard Kirabira’s passion for helping others led to them getting full-ride college scholarships in the States. Now these entrepreneurs are applying what they learned by giving back to their homeland.

“We came back with a a very single purpose – to create startups that help youth get the opportunity to work. That’s the biggest need – jobs,” Mugabi said.

His telecom service business Connect offers employment and internship opportunities and conducts tech training at colleges.

Kirabira, whose Chicken City Farms ministry trains young men to raise chickens to market and to operate their own small farms, said, “We want to lead people in all areas but focusing on economic empowerment because we believe when someone is economically stable you can talk to them about Christ. But if I’m not stable, if I am not sure what I’m going to eat tomorrow, your message may not even make sense to me. So we try to tackle the gospel by bringing some hope for people to take care of their families and their needs.”

Bottom-line, Kirabira said, “Young people here need an opportunity to work. That’s what will turn around the country.”

Healing

In places haunted by terror and violence, healing’s in order, too. Gacaca courts attempted to foster healing In Rwanda, where CARSA walks directly related genocide perpetrators and survivors through reconciliation workshops. After years of mounting tensions, a contrived ethnic war pitted the majority Hutus against the minority Tutsis. Wholesale slaughter ensued. We met survivors who lost their family and home. Pipeline’s building a home for a widow survivor named Catherine. We met a young man who’s forgiven the person who killed his siblings.

Christophe translated for us.

A man and woman bound by pain shared their testimonies. He’s Hutu and she’s Tutsi. They were neighbors. He was friends and drinking mates with her husband, He admitted getting caught up in the blood lust of atrocities. He participated in her husband’s murder and stole her home and possessions. He served 11 years in prison for his crimes. She had trouble moving on after losing so much, including two children. After the perpetrator’s release from prison he returned to their village and she couldn’t bear to see him. With support from CARSA she found the strength and grace to forgive him. The pair now share a cow they tend, enjoying the milk and calves it produces.

Of the man who caused such heartache she’s neighbors with again, she said, “He was able to open up and open the secret of his heart to us and I did the same towards him and I’ll tell you since then things have changed. Now we not only greet one another but we are friends.”

We were all struck by what we heard. Scott Katskee said it was the most moving thing he experienced in Africa. Crawford found it “crazy” i.e. amazing one could find peace amidst such angst. Julia Brown doubted reunification could happen here.

Nollette said, “The stories in Rwanda are deeply personal and I always feel honored these people share them with us. Catherine, the widow who lost her husband and child and is currently living with her sister, seemed especially sad. I could sense she feels hopeless. Christophe told her we wanted to build her a house, but I don’t think she believes it will happen.”

Ex-Pats

We met other Westerners whose Africa commitment has changed their lives. Former CNN reporter Patricia Smith does marketing for Saint Monica’s. During our visit she documented the blessing of a new dorm in Atiak and our supplying bedding for the female residents, who worked merrily alongside us. Maggie Josiah sought radical change and found it at the African Hospitality Institute she carved out of the bush in Luwero, a district in central Uganda. AHI trains women to work in Uganda’s booming hospitality industry.

A few years ago Canadian Randy Sohnchen and his wife moved to Uganda, where he now runs Omer Farming Co., one of several agricultural concerns looking to turn millions of untouched acres of rich soil into producing croplands. “It’s got all the makings of a classic land rush,” he said, adding productivity gains should improve Ugandans’ quality of life. His decision to live there, he said, is based on his experience that “nothing lasting happens unless somebody dwells.”

Apollo agrees that “being on the ground” is indispensable and “totally different” than managing things long-distance.

Sohnchen’s done development work elsewhere and he said, “In 15 years this country will be transformed. It’s gonna happen, I’ve seen it happen in other places. It will happen here.”

Americans Todd and Andria Ellingson caught the vision, too. but soon after moving to Rwanda to start a school they thought they’d made the biggest mistake of their lives.

“Everything fell apart. It was nothing what we thought it would be. Finally, after much reevaluation and just staying the course,” Todd said, “we’re seeing the impact, we’re seeing the fruit of what we planted and watered.”

Their City of Joy consists of a school, a kitchen, a well, a water tower. A church is being built. They brought electricity to the community. They’re looking to help farmers reap more yield. That doesn’t mean it’s gotten any easier,

“Still lots of doubt, even today,” he said. “Am I really making a difference or am I just enabling and spoon-feeding?”

He said living and working in an isolated area so far from home “there’s that constant stress of being in a different culture,” adding, “If you don’t focus on keeping yourself healthy, you can crash and burn here. It’s probably the best thing I’ve ever done, but the hardest.”

Respecting African autonomy and aspirations

Nollette said many Westerners who come make the mistake of wanting “to fix everything,” adding, “If you try to do everything for everyone then it’s unlikely you’ll do anything of much substance. It’s easy to come in and act like Santa Claus. It will make you feel better, but the reality is when you leave you haven’t done anything to help. I want our help and support to be meaningful and sustainable. I want to have real impact that outlives our visits.

“The key is collaboration. It requires us to be true partners – ready to listen and learn. We need to be the supporters and empower the local leaders. It’s not as glamorous but it is what allows for meaningful change.”

She used as an example the Rwandan pygmy village Christophe took us to. Residents depend on an unreliable water supply and they can’t make a living from the pots they fire and sell.

“It’s obvious they need help but what to do will take some time,” Nollette said. “Is there a way to capture and store the water? Do we train them on a new skill so they have a better way to earn income? Christophe and I both agree we don’t know the best solution at this time. We’re going to have to learn more and discuss various options.”

Apollo said there’s no shortage of resources flowing in from governments, NGOs and other sources. Corruption siphons off much of it, but even what’s left he said is controlled by outside, often non-African forces. It’s an old story in these former colonial lands where British rule persisted.

“They brought civilization, they brought education, clothing, but they also promoted slavery. They gave us guns to kill ourselves, they divided us, they diluted us.”

Africa’s come to rely on and rue white influence. In the poorest spots we visited children excitedly waved and shouted “mzungo” (rich whites). Apollo did, too, as a child.. I asked what he was thinking when he saw whites then.

“Opportunity. Every time you saw a white person you thought of opportunity, financially, because when you’re growing up you watch movies and everything you see about Europe or America is nice roads, nice cars, nice houses. Even the poor live in very decent homes. So maybe a white person might throw some money at you. Yeah, growing up that’s what I felt. Sometimes just being able to have a white person notice me was big. I remember standing by the roadside when a car or a bus went by with white people. I would run screaming and waving, and it just took one person to wave back and that was just heaven to me. I can say the same for most of my friends.”

“Is it the same with today’s kids, too?” I asked.

“Absolutely.”

“Is there ever any negative connotation to this?”

“Not with the children. The adults, if they’ve had education, they know what the British did, they came and looted our continent, so there’s a bit of bias.”

Joseph Sutter articulated the conflict many of us felt as privileged Americans just passing through. “You have a guilty conscious the way they look at you when we’re driving by.” Referring to the gifts we handed out here and there, Nollette said, “Are we doing anything good by giving suckers and jerseys? No.”

“Well, it makes them happy for a second,” Julia Brown noted.

Nollette said feel-good, bandaid fixes won’t solve a person’s or a nation’s systemic problems. Change must begin with a better educated populace and committed new leadership,

“When people have access to good education they learn what’s possible,” she said. “That’s why it’s important to partner with developing leaders.”

Given the instability of the Ugandan civil war and Rwandan genocide of only a decade and a generation ago, respectively, she said people who lived through those times are apt to have lower expectations.

“Knowing there may be some corruption and there’s no innovation and infrastructure, they’re okay because they don’t want the alternative.”

Younger people are more demanding.

“They’re looking for leadership, they want education, they want to develop the country.”

Apollo said, “The biggest challenge we have is leadership and stewardship. We must raise a generation that grows up with integrity, that is corrupt free and that will be true stewards of the resources of this nation and this continent.”

Coming and going

Nollette doesn’t ever want to assume she has things figured out. It’s a sensitive point brought home by none other than Terence Crawford, a product of a ghetto she only has glancing knowledge of, much like Africa’s slums.

“It’s the same thing I talk to Bud about all the time. He’ll say, ‘You don’t know what it’s like,’ and I’m like, ‘You’re right, I don’t know, you have to tell me what can I do.'”

Just like our visit to the genocide memorial in Kigali, Rwanda couldn’t possibly help us understand the scope of carnage and despair that resulted when madness befell the nation.

“I think it’s really sad,” Julia Brown said. “It makes me feel every one here must have been affected but it doesn’t seem like it, everyone’s going about their day normally. It’s hard to picture anything that happened even though I just saw pictures.”

“Sobering. I can’t imagine what those people went through when there were just dead bodies everywhere,” said Scott Katskee, who had a friend die in his arms on a Nepal mountain trek. “It was hard for me to reconcile one dead body. But this…”

It’s a grim recent past but Nollette’s focused on helping Rwandans and Ugandans move forward.

“Every time I go on a trip it reminds me of how important the work we’re doing is and to keep faithful and dedicated. It can be draining and frustrating at times but when I see our partners and projects, it makes me forget everything else. Their sacrifice and dedication inspires me.”

Nollette said her husband supports her work and the travel it entails. It’s become a family affair, too. He went in February. Their son Sam in 2012. “Sam raised money for three wells hosting a baseball tournament. It was a huge personal highlight for me. He wants to go back,” she said. “I’m bringing my youngest, Shea, with me in November. I plan on taking my oldest, Morgan, next June when she graduates from high school. They have to raise their own money to go.”

Several in our party expressed a desire to return. As for myself, I recall what someone we met said about his first coming to Africa: “What an eye-opener. The biggest life lesson I’ve learned. America is not like the rest of the world.” Or as someone in our travel group put it: “There’s so much more to the world than just Nebraska.” Ah, there you have it. Now that I’ve expanded my horizons I want to see more because I know I’ve barely scratched the surface. There’s so much more to see and do.

I’m reminded, too, of what a priest friend of mine who’s done missionary work in far-flung places refers to as crossing bridges. He says every time we venture into a new culture we cross a bridge of insight and understanding. Having finally taken such a big leap of my own, my appetite has been whetted for more. Therefore, I fully expect to make new crossings that further open my eyes and stretch my boundaries.

As I discovered, making connections with people in places as distant as Africa is only limited by our means and imagination. Not everyone can go there for themselves, but they can support projects and programs that make a difference.

To learn more about the work of Nollette’s nonprofit, visit http://pipelineworldwide.org/. Visit http://pipelineworldwide.org/partners/ for links to its partner organizations.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at leoadambiga.com

The Champ Goes to Africa: Terence Crawford Visits Uganda and Rwanda with his former teacher, this reporter and friends

The Champ Goes to Africa

Terence Crawford Visits Uganda and Rwanda with his former teacher, this reporter and friends

Two-time world boxing champ Terence Crawford of Omaha has the means to do anything he wants. You might not expect then that in the space of less than a year he chose to travel not once but twice to a pair of developing nations in Africa wracked by poverty, infrastructure problems and atrocity scars: Uganda and Rwanda, I accompanied his last trip as the 2015 winner of the Andy Award for international journalism from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Until now I’ve posted a little about the grant that took me to Africa along with a few pictures and anecdotes from the trip. But now I’m sharing the first in a collection of stories I’m writing about the experience, which is of course why I went there in fhe first place. This cover story in the coming July issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com) emphasizes Crawford within the larger context of what he and the rest of us saw, who we met and what we did. Future pieces for other publications will go even more into where his Africa sojourns fit into his evolving story as a person and as an athlete. But at least one of my upcoming stories from the trip will try to convey the totality of the experience from my point of view and that of others. I feel privilged to have been given the opportunity to chronicle this journey. Look for new posts and updates and announcements related to this and future stories from my Africa Tales series.

NOTE: This is at least the fifth major article I’ve written about Crawford. You can find all of them on this blog site. Find them at-

https://leoadambiga.com/?s=crawford

AFRICA TALES IN IMAGES

Here is a link to a video slideshow of the June trip I made to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa with The Champ, Terence Crawford and Alindra I Person, Jamie Fox Nollette, Scott Katskee, Joseph Sutter and Julia Brown.

The visuals were edited, set to music, given movement and in some cases captioned by my friend Victoria White, an Omaha filmmaker.

NOTE: I am available to make public presentations about the trip and the video slideshow will be a part of the talk that I give. We will be updating the video slideshow with new images to keep it fresh and to represent different aspects of the experience we had in those developing nations.

All my stories about the trip can also be found on this blog. Access them at-

https://leoadambiga.com/?s=africa

(Below is a text-only format of the same article)

The Champ Goes to Africa

Terence Crawford Visits Uganda and Rwanda with his former teacher, this reporter and friends

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Senior contributing writer Leo Adam Biga, winner of the 2015 Andy Award for international journalism from the University of Nebraska at Omaha, chronicles recent travels he made in Africa with two-time world boxing champion Terence Crawford.

Expanding his vision

Terence “Bud” Crawford’s rise to world boxing stardom reads more graphic novel than storybook, defying inner city odds to become one of the state’s most decorated athletes. Not since Bob Gibson ruled the mound for the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1960s has a Nebraskan so dominated his sport.

When Bud overheard me say he might be the best fighter pound-for-pound Neb.’s produced, he took offense:. “Might be? I AM the best.”

En route to perhaps being his sport’s next marquee name, he’s done remarkable things in improbable places. His ascent to greatness began with a 2013 upset of Breidis Prescott in Las Vegas, In early 2014 he captured the WBO lightweight title in Glasgow, Scotland. He personally put Omaha back on the boxing map by twice defending that title in his hometown before huge CenturyLink Center crowds last year.

In between those successful defenses he traveled to Uganda and Rwanda, Africa in August. He went with Pipeline Worldwide co-founder Jamie Fox Nollette, an Omaha native and Bud’s fourth grade teacher at Skinner Magnet School. After reuniting in mid-2014, he expressed interest going to Africa, where her charitable organization works with partners to drill water wells and to support youth-women’s programs.

When I caught up with The Champ last fall, he left no doubt the impact that first trip made.

“It’s life-changing when you get to go over there and help people,” he says.

Nollette recalls, “When Terence left he had an empty suitcase. He left all his clothes, except what he was wearing, to a bus driver.”

“I just felt they needed it more than I did,” he says. ‘I just thought it was the right thing to do.”

Seeing first-hand profound poverty, infrastructure gaps and atrocity scars made an impression.

“Well, it just made me appreciate things more. It kind of humbled me in a way to where I don’t want to take anything for granted. I haven’t in my life experienced anything of the nature they’re experiencing over there. For one thing, I have clean water – they don’t have clean water. That’s one of their biggest issues and I want to help them with it. They appreciate everything, even if it’s just a hug or a handshake.”

Simpatico and reciprocal

Nollette says the trips and fundraisers she organizes raise awareness and attract donors.

Only weeks after winning the vacant WBO light welterweight title over Thomas Dulorme in Arlington, Texas last April Bud returned to those same African nations with Nollette.

“I told Jamie I would like to go back.”

He says locals told him, “We have a lot of people that come and tell us they’re going to come back and never do. For you to come back means a lot to us.”

“Just the little things mean a lot to people with so little, and so I guess that’s why I’m here,” Bud told an assembly of Ugandans in June.

None of this may have happened if he and Nollettte didn’t reconnect. Their bond transcends his black urban and her white suburban background. He supports Pipeline’s work and she raises funds for his B&B Boxing Academy in North O.

His first Africa trip never made the news because he didn’t publicize it. His June 1 through 12 trip is a different matter.

What about Africa drew this streetwise athlete to go twice in 10 months when so much is coming at him in terms of requests and appearances, on top of training and family obligations?

Beyond the cool machismo, he has a sweet, soft side and burning curiosity. “He really listens to what people say,” Nollette notes. “He wants to understand things.”

His pensive nature gets overshadowed by his mischievous teasing, incessant horseplay and coarse language.

This father of four is easy around children, who gravitate to him. He supports anything, here or in Africa, that gets youth off the streets.

He gives money to family, friends, homies and complete strangers. In 2014 he so bonded with Pipeline’s Uganda guide, Apollo Karaguba, that he flew him to America to watch his Nov. fight in Omaha.

“When I met Apollo I felt like I’ve been knowing him for years. I just liked the vibe I got. He’s a nice guy, he’s caring. He took real good care of us while we were out there.”

Bud says paying his way “was my turn to show him my heart.”

He respects Nollette enough he let her form an advisory committee for his business affairs as his fame and fortune grow.

Even with a lifelong desire to see “the motherland” and a fascination with African wildlife, it took Nollette reentering his life for him to go.

“Certain opportunities don’t come every day. She goes all the time and I trust her.”

His fondness for her goes back to when they were at Skinner. “She was one of the only teachers that really cared. She would talk to me.”

He needed empathy, he says, because “I got kicked out of school so much – a fight here, a fight there, I just always had that chip on my shoulder.” He says she took the time to find out why he acted out.

Catching the vision

Boxing eventually superseded school.

“I used to fall asleep studying boxing.”

Meanwhile, Nollette moved to Phoenix. On a 2007 church mission trip to Uganda she found her calling to do service there.

“It really impacted me,” she says. “I’ve always had a heart for kids and

I always had an interest in Africa.”

She went several times.

“There’s not really anything that can prepare you for it. The volume of people. The overwhelming poverty. Driving for hours and seeing all the want. I didn’t know what possibly could be done because everything seemed so daunting.

“But once I had a chance to go into some villages I started to see things that gave me hope. I was absolutely amazed at the generosity and spirit of these people – their hospitality and kindness, their gratitude. You go there expecting to serve and after you’re there you walk away feeling like you’ve been given a lot more. I was hooked.”

Bud got hooked, too, or as ex-pats say in Africa, “caught the vision.”

“I was very touched by the people and how gracious and humble and thankful they were about everything that came towards them. I had a great time with great people. I experienced some great things.”

Coming to Africa i:

Uganda

For this second trip via KLM Delta he brought girlfriend Alindra “Esha” Person, who’s the mother of his children. Joseph Sutter of Omaha and myself tagged along, Julia Brown of Phoenix joined us in Detroit and Scott Katskee, a native Omahan living in Los Angeles, added to our ranks in Amsterdam. Nollette arrived in Uganda a day early and met us in Entebbe, where Bud and Apollo enjoyed a warm reunion.

The next seven days in Uganda, which endured civil war only a decade ago, were a blur made foggier by jet lag and itinerary overload. Dividing our time between Kampala and rural areas we saw much.

Roadside shanties. Open market vendors. Christian schools, clinics, worship places. Vast, wild, lush open landscapes. Every shade of green vegetation contrasted with red dirt and blue-white-orange skies. Immense Lake Victoria. Crossing the storied Nile by bridge and boat.

The press of people. Folks variously balancing fruit or other items on their head. Unregulated, congested street traffic. Everything open overnight. Boda bodas (motor bikes) jutting amid cars, trucks, buses, pedestrians. One morning our group, sans me, rode aback boda bodas just for the thrill. I suggested to Bud Top Rank wouldn’t like him risking injury, and he bristled, “I run my life, you feel me? Ain’t nobody tell me what to do, nobody. Not even my mom or my dad.”

Ubiquitous Jerry cans – plastic yellow motor oil containers reused to carry and store water – carted by men, women, children, sometimes in long queues. “All waiting on water, that’s crazy,” Bud commented.

Stark contrasts of open slums and gated communities near each other. Mud huts with thatched roofs in the bush.

Long drives on unpaved roads rattled our bodies and mini-bus.

Whenever delays occurred it reminded us schedules don’t mean much there. Bud calls it TIA (This is Africa). “Just live in the moment…go with the flow,” he advised.

In a country where development’s piecemeal, Apollo says, “We’re not there yet, but we’re somewhere.”

Africans engaged in social action say they’ve all overcome struggles to raise themselves and their countrymen. “I was one of the lucky few to get out (of the slums),” Apollo says. They want partners from the developed world, but not at the expense of autonomy.

Many good works there are done by faith-based groups. Apollo works for Watoto Child Care Ministries, whose campus we toured. Three resident boys close to Nollette bonded with Bud on his last trip. The boys joined us for dinner one night.

We spent a day with Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe, whose vocational work with exploited females has won acclaim. Last year Nollette produced a video showing Bud training Sister for a mock fight with Stephen Colbert. This time, Nollette, Bud and Co. outfitted a dormitory for her girls in Atiak, where Pipeline built a well. Bud played music the girls danced to. They honored us with a traditional dinner and dance.

We toured Pastor Ben Kibumba’s Come Let’s Dance (CLD) community development organization. Bud and others gave out jerseys to kids.

Nakavuma Mercy directs CLD’s Thread of Life empowerment program for single moms in Kampala’s Katanga slum.

We met Patricia at Bless a Child, which serves cancer-stricken kids in Kampala, and Moses, who’s opening a second site in Gulu. We met young entrepreneurs Charles Mugabi and Richard Kirabira, whose Connect Enterprise and Chicken City Farms, respectively, are part of a creative class Pipeline partners with.

“One of the things I see is that you have a lot of young people with strong leadership skills and I want to be able to come alongside them and support them in their efforts,” Nollette says.

Apollo says Uganda needs new leadership that’s corruption-free and focused on good resource stewardship.

Nollette says she offers “a pipeline to connect people in the States with opportunities and projects in Africa that are really trying to make a difference in their communities.”

It’s all about leveraging relationships and expertise for maximum affect.

We met ex-pats living and work there: Todd Ellingson with City of Joy and Maggie Josiah with African Hospitality Institute.

Josiah offered this advice:

“A lot of times, especially we Americans come over thinking we have all the answers and we know how to fix all the problems, and really we don’t need to fix any of the African problems. They will fix them themselves in their own time. But come over and listen and learn from them. The Africans have so much to teach us about joy when we have very little, they have so much to teach us about what it really means to live in community, what it means to live the abundant life…”

Hail, hail, The Champ is here

Having a world champ visit proved a big deal to Ugandans, who take their boxing seriously. The nation’s sports ministry feted Bud like visiting royalty at a meeting and press conference. He gained extra cred revealing he’s friends with two Ugandan fighters in the U.S., Ismail Muwendo and Sharif Bogere.

“I want to come back with Ismail.”

Ministry official Mindra Celestino appealed to Bud “to be our ambassador for Uganda.” Celestino listed a litany of needs.

“Whatever I can do to help, I’d like to help out,” Bud said. “I’m currently helping out Ismail. He fought on the undercard of my last fight. We’re building him up.”

Bud won over officials, media and boxers with his honesty and generosity, signing t-shits and gloves, posing for pics, sharing his highlight video and delivering an inspirational message.

“For me coming up was kind of hard. You’ve got gangs, you’ve got drugs, you’ve got violence. I got into a lot of things and I just felt like boxing took me to another place in my life where I could get away from all the negativity. I got shot in my head in 2008 hanging out with the wrong crowd. At that time I knew I just wanted to do more with my life, so I started really pursuing my boxing career.

“I had a lot of days I wanted to quit. For you boxers out there this ain’t no easy sport. It’s hard, taking those punches. You might be in the best shape of your life, but mentally if you’re not in shape you’re going to break down.”

He emphasized how much work it takes to be great.

“Every day, any boxing I could watch, I would watch. I would take time out to study, like it was school. I would tell you to just work hard, stay dedicated, give your all every time you go in there and who knows maybe you can be the next champion of the world.”

He referred to the passion, discipline and motivation necessary to carry you past exhaustion or complacency.

“There’s going to be days you want to quit. Those are the days you’ve got to work the hardest. I never was given anything. I was one of those kids they said was never going to make it – I used that as an opportunity to prove them wrong.”

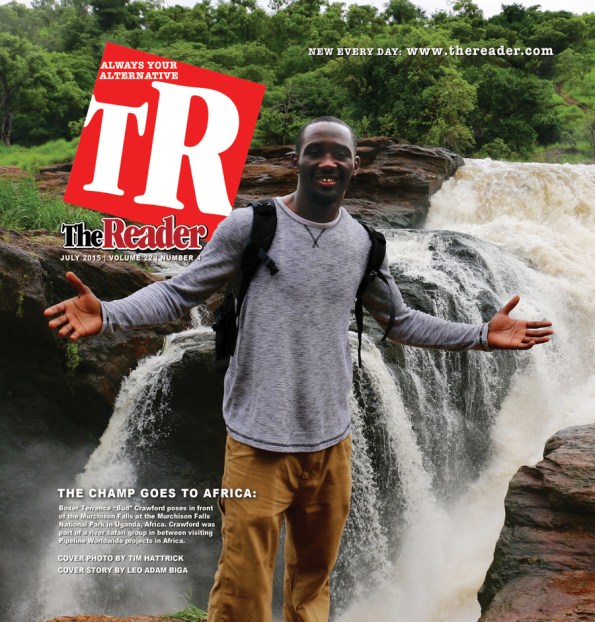

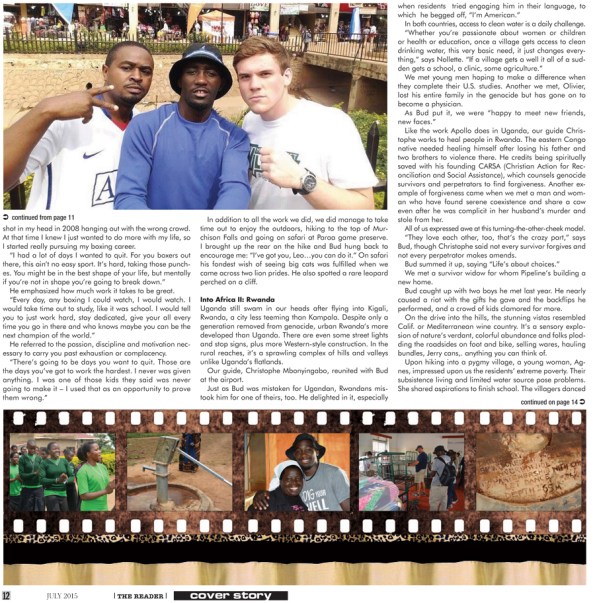

We did take time out to enjoy the outdoors, hiking to the top of Murchison Falls and going on safari at Paraa game preserve. I brought up the rear on the hike and Bud hung back to encourage me: “I’ve got you, Leo…you can do it.” On safari his fondest wish of seeing big cats was fulfilled when we came across two lion prides. He earlier spotted a rare leopard perched on a cliff.

Into Africa II:

Rwanda

Uganda still swam in our heads after flying into Kigali, Rwanda, a city less teeming than Kampala. Despite only a generation removed from genocide, urban Rwanda’s more developed than Uganda. There are even some street lights and stop signs, plus more Western-style construction. In the rural reaches, it’s a sprawling complex of hills and valleys unlike Uganda’s flatlands.

Our guide, Christophe Mbonyingabo, reunited with Bud at the airport.

Just as Bud was mistaken for Ugandan, Rwandans mistook him for one of theirs, too. He delighted in it, especially when residents tried engaging him in their language and he begged off, “I’m American.”

In both countries, access to clean water is a daily challenge.

“Whether you’re passionate about women or children or health or education, once a village gets access to clean drinking water, this very basic need, it just changes everything,” says Nollette. “If a village gets a well it all of a sudden gets a school, a clinic, some agriculture.”

We met young men hoping to make a difference when they complete their U.S. studies. Another, Olivier, lost his entire family in the genocide but has gone on to become a physician.

As Bud put it, we were “happy to meet new friends, new faces.”

Like the work Apollo does in Uganda, Christophe works to heal people in Rwanda. The eastern Congo native needed healing himself after losing his father and two brothers to violence there. He credits being spiritually saved with his founding CARSA (Christian Action for Reconciliation and Social Assistance), which counsels genocide survivors and perpetrators to find forgiveness. We met a man and woman – he was complicit in her husband’s murder and stole from her – who’ve come to a serene coexistence. They now share a cow.

All of us expressed awe at this turning-the-other-cheek model.

“They love each other, too, that’s the crazy part,” says Bud, though Christophe said not every survivor forgives and not every perpetrator makes amends.

Bud summed it up with, “Life’s about choices.”

We met a survivor widow for whom Pipeline’s building a new home.

Bud caught up with two boys he met last year. He nearly caused a riot when the gifts he gave and the backflips he performed were spent and a crowd of kids clamored for more.

On the drive into the hills, the stunning vistas resembled Calif. or Mediterranean wine country. It’s a sensory explosion of nature’s verdant, colorful abundance and folks plodding the roadsides on foot and bike, selling wares, hauling bundles, Jerry cans,. you name it.

Upon hiking into a pygmy village, a young woman, Agnes, impressed on us residents’ extreme poverty. Their subsistence living and limited water source pose problems. She shared aspirations to finish school. The villagers danced for us. Our group returned the favor. Then Scott Katskee played Pharrell’s “Happy” and everyone got jiggy.

Seeing so much disparity, Bud observed. “Money can’t make you happy, but it can make you comfortable.”

A sobering experience came at the genocide memorial in Kigali, where brutal killings of unimaginable scale are graphically documented.

Group dynamics and shooting the bull

The bleakness we sometimes glimpsed was counteracted by fun, whether playing with children or giving away things. Music helped. At various junctures, different members of our group acted as the bus DJ. Bud played a mix of hip hop and rap but proved he also knows old-school soul and R&B, though singing’s definitely not a second career. Photography may be, as he showed a flair for taking stills and videos.

In this device-dependent bunch, much time was spent texting, posting and finding wi-fi and hot spot connections.

On the many long hauls by bus or land cruiser, conversation ranged from music to movies to gun control to wildlife to sports. Apparel entrepreneur Scott Katskee entertained us with tales of China and southeast Asia travel and friendships with noted athletes and actors.

Bud gave insight into a tell Thomas Dulorme revealed at the weigh-in of their April fight.

“When you’re that close you can feel the tension. I could see it in his face. He was trying too hard. If you’re trying too hard you’re nervous. If he’s intimidated that means he’s more worried about me than I am about him. I won it right there.”

Our group made a gorilla trek, minus me. Even Bud said it was “hard” trudging uphill in mud and through thick brush. He rated “chilling with the gorillas” his “number one” highlight, though there were anxious moments. He got within arm’s reach of a baby gorilla only to have the mama cross her arms and grunt. “That’s when I was like, OK, I better back off.” A silverback charged.

Back home, Bud’s fond of fishing and driving fast. He has a collection of vehicles and (legal) firearms. He and Esha feel blessed the mixed northwest Omaha neighborhood they live in has welcomed them.

Nollette correctly predicted we’d “become a little family and get to know each other really well.” She was our mother, chaperone, referee and teacher. Her cousin Joseph Sutter, an athlete, became like a little brother to Bud, whom he already idolized. When the pair wrestled or sparred she warned them to take it easy.

“Stop babying him,” Bud said. “I’m not going to hurt him. I’m just going to rough him up. You know how boys play.”

Like all great athletes Bud’s hyper competitive – “I don’t like to lose at nothing,” he said – and he didn’t like getting taken down by Suetter.

Once, when Bud got testy with Nollette. Christophe chastised him, “I hope you remember she’s your teacher.” Bud played peacemaker when things got tense, saying, “Can’t we all get along? We’re supposed to be a family.” We were and he was a big reason why. “What would y’all do without me? I’m the life of the party,” he boasted.

Out of Africa…for now

As The Champ matures, there’s no telling where he’ll wind up next, though Africa’s a safe bet. When I mentioned he feels at home there, he said, “It IS home. I’m AFRICAN-American. It’s where a lot of my people come from historically down the line of my ancestors. Damn, I love this place. I’m just thankful I’m able to do the things I’m able to do. I can help people and it fills my heart.”

Our last night in Africa Christophe and Nollette implored us not to forget what we’d seen. Fat chance.

Recapping the journey, Bud said, “That was tight.”

Bud may next fight in Oct. or Feb., likely in Omaha again.

Sparring for Omaha: Boxer Terence Crawford Defends His Title in the City He Calls Home

My latest story about Omaha’s own world boxing champion, Terence “Bud” Crawford, who is fresh off his Nov. 29 title defense in his hometown. I was at the CenturyLink for the fight and some of what I experienced there is in this story for Omaha Magazine (http://omahamagazine.com/). It’s on the stands now. My blog contains several other articles I’ve written about Terence.

Sparring for Omaha: Boxer Terence Crawford Defends His Title in the City He Calls Home

In a class by himself

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in Omaha Magazine (http://omahamagazine.com/)

Terence “Bud” Crawford grew up a multi-sport athlete in North Omaha, but street fighting most brought out his hyper competitiveness, supreme confidence, fierce determination and controlled fury. He long ago spoke of being a world champion. That’s just what he’s become, too, and he’s now sharing his success with the community that raised him and that he still resides in.

A gifted but star-crossed amateur boxer, he turned pro in 2008 and for years he fought everywhere but Omaha. It was only after winning the WBO title last March against Ricky Burns in Scotland, he finally returned home to fight as a professional. As reigning champion Crawford headlined a June 28 CenturyLink Center card. He successfully defended his title with a rousing 9-round technical knockout over Yuriorkis Gamboa before 10,900 animated fans.

He made a second victorious defense here Nov. 29 against challenger Ray Beltran. Before a super-charged crowd of 11.200 he dismantled Beltran en route to a 12-round unanimous decision. The convincing win made him Ring Magazine’s Fighter of the Year.

Even with everything he’s done, Crawford, who’s expected to move up to the welterweight division, says, “I’m hungry because I want more. I don’t want to just stop at being good, I want to be great. I want to keep putting on performances that will take me to that next level.”