Archive

Thomas Gouttierre: In Search of a Lost Dream, An American’s Afghan Odyssey

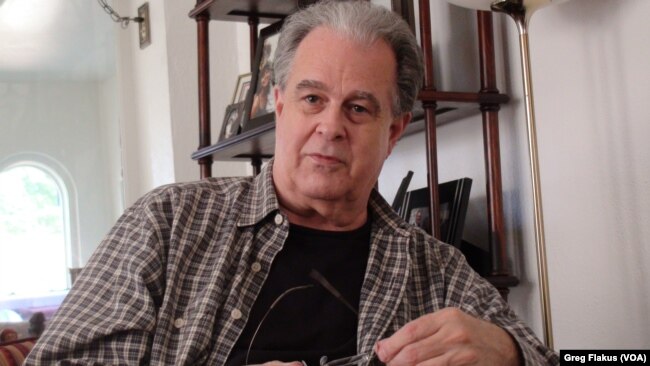

Thomas Gouttierre’s work with Afghanistan has drawn praise and criticism, moreso the latter as of late given what’s happened there with the war and some of that nation’s top leadership having been befriended and trained by Gouttierre’s Center for Afghanistan Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The following profile I did on Gouttierre appeared in 1998, long before U.S. involvement there escalated into full military intervention. Regardless of what’s happened since I wrote the piece, the essential core of the story, which is that of Gouttierre’s magnificent obsession with that country and its people, remains the same.

The story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Thomas Gouttierre: In Search of a Lost Dream, An American’s Afghan Odyssey

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Like a latter-day Lawrence of Arabia, Omahan Thomas Gouttierre fell under the spell of an enigmatic desert nation as a young man and has been captivated by its Kiplingesque charms ever since.

The enchanting nation is Afghanistan and his rapture with it began while working and living there from 1965 to 1974, first as a Peace Corps volunteer teaching English as a second language, then as a Fulbright fellow and later as executive director of the country’s Fulbright Foundation. His duties included preparing and placing Afghan scholars for graduate studies abroad. During his 10 years there, Gouttierre also coached the Afghan national basketball team. Sharing the adventure with him was his wife and fellow Peace Corps volunteer Marylu. The eldest of the couple’s three sons, Adam, was born there in 1971.

Before his desert sojourn, the Ohio native was a naive, idealistic college graduate with a burning desire to serve his fellow man. When he got his chance half-a-world away, it proved a life transforming experience.

“It’s the place where I kind of grew to a mature person,” he said. “I was there from age 24 to 34 and I learned so much about myself and the rest of the world. It gave me an opportunity to learn well another language, culture and people. I love Afghanistan. It’s people are so admirable. So unique. They have a great sense of humor. They’re very hospitable. They have a great self-assurance and pride.”

But the Afghanistan of his youth is barely recognizable now following 19 years of near uninterrupted carnage resulting from a protracted war with the former Soviet Union and an ongoing civil war. Today, the Muslim state lies in shambles, its institutions in disarray. The bitter irony of it all is that the Afghans themselves have turned the heroic triumph of their victory over the vaunted Soviet military machine into a fratricidal tragedy.

Over the years millions of refugees have fled the country into neighboring Pakistan and Iran or been displaced from their homes and interred in camps across Afghanistan. An entire generation has come to maturity never setting foot in their homeland or never having known peace.

The nation’s downward spiral has left Gouttierre, 57, mourning the loss of the Afghanistan he knew and loved. “In a sense I’ve seen what one might call the end of innocence in Afghanistan,” he said, “because for all its deficiencies, Afghan society – when I was living there – was really a very pleasant place to be. It was a quite stable, secure society. A place where people, despite few resources and trying circumstances, still treated each other with a sense of decency and civility. It was a fantastic country. I loved functioning in that Afghanistan. I really miss that environment. Not to be able to go back to that culture is a real loss.”

Through it all, Gouttierre’s kept intact his ties to the beleaguered Asian nation. In his heart, he’s never really left. The job that took him away in 1974 and that he still holds today – as director of the Center for Afghanistan Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha – has kept him in close contact with the country and sent him on fact-finding trips there. He was there only last May, completing a tour of duty as a senior political affairs officer with the United Nations Special Mission to Afghanistan. It was his first trip back since 1993 (before the civil strife began), and what he saw shook him.

“To see the destruction and to learn of the deaths and disappearances of so many friends and associates was very, very sad,” he said from his office on the UNO campus, where he’s also dean of the Office of International Studies and Programs. “Much of the country looks like Berlin and Dresden did after the Second World War, with bombed-out villages and cities. Devastation to the point where almost no family is left unaffected.

“Going back for me was very bittersweet. With every Afghan I met there was such despair about the future of the country. The people are fed up with the war…they so want to return to the way things were. People cried. It was very emotional for me too.”

Everywhere he went he met old friends, who invariably greeted him as “Mr. Tom,” the endearing name he’d earned years before. “In every place I visited I wound up seeing people that I have known for most of my adult life. Individuals that have been here at the University of Nebraska at Omaha – in programs that we’ve sponsored – or people I coached in basketball or people I was instrumental in sending to the U.S. under Fulbright programs or people who taught me Persian and other languages of Afghanistan. So, you know, there’s kind of an extended network there. In fact, it was kind of overwhelming at times.”

Colleague Raheem Yaseer, coordinator of international exchange programs in UNO’s Office of International Studies and Programs, said, “I think he’s received better than any ambassador or any foreign delegation official. He’s in good standing wherever he goes in Afghanistan.”

Yaseer, who supervised Gouttierre in Afghanistan, came to America in 1988 at the urging of Gouttierre, for whom he now works. A political exile, Yaseer is part of a small cohesive Afghan community in Nebraska whose hub is UNO’s Center for Afghanistan Studies. The center, which houses the largest collection of materials on Afghanistan in the Western Hemisphere, provides a link to the Afghans’ shared homeland.

Aside from his fluency in native dialects, his knowledge of Islamic traditions and sensitivity to Afghan culture, Gouttierre also knows many of the principals involved in the current war. It’s the kind of background that gives him instant access and credibility.

“I don’t think there’s any question about that,” Gouttierre said. “The Afghans have a phrase that translates, ‘The first time you meet, you’re friends. The second time you meet, you’re brothers.’ And Afghans really live by that – unless you poison that relationship.”

According to Yaseer, Gouttierre’s “developed a skill for penetrating deep into the culture and traditions of the people and places he visits. He’s able to put everything in a cultural context, which is rare.”

It’s what enables Gouttierre to see the subtle shadings of Afghanistan under its fabled veil of bravado. “When people around the world wonder why the Afghans are still fighting, they don’t realize that a society’s social infrastructure and fabric is very fragile,” said Gouttierre. “They don’t realize what it means to go through a war as devastating as that which the Afghans experienced with the Soviet Union – when well over a million people were killed and much of the traditional resources and strengths of the country were destroyed. When the Soviets left, the Afghans tried to cobble together any kind of government and they were unsuccessful.

“Now they’re trying to put this social-political Humpty-Dumpty back together again, and its just very difficult.”

Under Gouttierre’s leadership the center has been a linchpin in U.S.-U.N. efforts to stabilize and rebuild Afghanistan and has served as a vital conduit between Afghans living inside and outside the country and agencies working on the myriad problems facing it. With nearby Peshawar, Pakistan as a base, the center has operated training and education programs in the embattled country, including a new program training adults in skills needed to work on planned oil and gas pipelines.

Gouttierre himself is a key adviser to the U.S. and world diplomatic community on Afghan matters. He’s served as the American specialist on Afghanistan, Tajikistan and South Asia at meetings of the U.S.-Russian Task Force (Dartmouth Conference) on Regional Conflicts. He’s made presentations on Afghan issues at Congressional hearings and before committees of the British Parliament and the French National Assembly.

And last year he was nominated by the U.S. State Department to serve as the American representative on the U.N. Mission to Afghanistan. “It was quite an honor,” said Gouttierre. “And for me to go back and work among the people again was very appealing and very rewarding.”

The aim of the U.N. mission, whose work continues today, is to engage the combating parties in negotiations toward a just peace settlement. German Norbert Holl, a special representative of the U.N. secretary general to Afghanistan, heads the mission, whose other members are from Russia, Japan, England and France.

On two separate month-long trips to Afghanistan, Gouttierre met with representatives of the various factions and visited strategic sites – all in an effort to help the team assess the political situation. His extensive travels took him the length and breadth of the country and into Pakistan, headquarters for the mission. He talked with people in their homes and offices, he visited bazaars, he viewed dams, irrigation projects and opium fields and traversed deserts and mountains.

Marylu Gouttierre said her husband’s involvement with Afghanistan and commitment to its future stems, in part, from a genuine sense of debt he feels. “He feels a responsibility. It is his second home and those are his people. He’s not only given his heart, but his soul to the country.”

He explains it this way: “Afghanistan has a special place in my professional and personal life and it has had a tremendous impact on my career. It’s been so much an instrument in what I’ve done.”

To fully appreciate his Afghan odyssey, one must review how the once proud, peaceful land he first came to has turned into a despairing, chaotic killing field. The horror began in 1978, when Soviet military forces occupied it to quell uprisings against the puppet socialist regime the USSR had installed in the capital city of Kabul. The Soviets, however, met with stiff resistance from rebel Mujaahideen freedom fighters aligned with various native warlords. Against all odds, the Afghans waged a successful jihad or holy war that eventually ousted the Soviets in 1989, reclaimed their independence and reinforced their image as fierce warriors.

The Afghans, whose history is replete with legendary struggles against invaders, never considered surrender. Said Gouttierre, “The Afghans felt they were going to win from the start. They felt they could stick with it forever. They had a strong belief in their own myth of invincibility…and to everyone’s surprise but their own, they did force the Soviets to leave.”

But the fragile alliance that had held among rival factions during the conflict fell apart amid the instability of the post-war period. “The Soviets left someone in charge who had been their ally in power. That was Najeebullah. His government fell in 1992. That only helped exacerbate things. The cycle of fighting continued as the Afghans who had fought against the Soviet army continued their fight against Najeebullah, who was captured, tried and executed by the Taliban (an Islamic faction) in September of 1996 for his crimes against the Afghans, which were considerable.” Gouttierre knew Najeebullah in very different circumstances before the war, when the future despot was a student of his in a class he taught at a native high school.

After Najeebullah’s fall, a mad scramble for power ensued among the Mujaahideen groups. As Gouttierre explains, “The leaders of these groups had become warlords in their own regions. They kind of got delusions of grandeur about who should be in control of the whole country and they began to struggle against each other.”

In the subsequent fighting, one dominant group emerged – the Taliban, a strict Islamic movement whose forces now command three-quarters of the country, including the capital of Kabul – with all its symbolic and strategic importance. A loose alliance of factions oppose the Taliban.

“As the Taliban (Seekers of Islam) grew in strength, they began intimidating and even fighting some of the minor Mujaahideen commando groups, and to a lot of people’s surprise, they were successful,” said

Gouttierre, whose U.N. assignment included profiling the Taliban. “They are very provincial, very rural – and in their own minds – very traditional Muslims and Afghans. They’re not that philosophically sophisticated in terms of their own religion, but they are very sophisticated in terms of what they understand they want for their society, and they’re able to argue and discourse on it at length without giving any quarter. And they’re willing to go to war over it.

“Each region where they’ve gone, they’ve been aided by the fact that the people living there were disenchanted with those in control. Most of the other groups, unfortunately, lost any credibility they had because of their failure to bring about peace, stability, security and reconstruction. The people were willing to support almost anything that came along.”

The Taliban has drawn wide criticism, internally and externally, for its application of extreme Islamic practices in occupied areas, particularly for placing severe restrictions on women’s education and employment and for imposing harsh penalties on criminals. Gouttierre said while such actions elicit grave concerns from the U.N. and represent major stumbling blocks in the Taliban’s quest for full recognition, the movement has effectively restored order in areas it controls.

“I have to say that in the areas of Afghanistan I traveled to which they control, the Taliban had confiscated all the weapons, removed all the checkpoints people had to pass through, eliminated the extortion that was part of the checkpoints and instilled security and stability,” said Gouttierre. “You could travel anywhere in Kabul without having to be in any way concerned, except for the mines that haven’t been cleared yet.”

Conversely, he said, the Taliban has exhibited brutal politics of intimidation and blatant human rights violations, although other factions have as well. “It’s not a question of who’s good and who’s bad,” he adds. “There’s plenty of blame and credit to be shared on all sides.”

He found the Taliban a compelling bunch. “One of the things I was impressed with is that all of the leaders I met were in some ways victims of the war with the Soviet Union. They all exhibited wounds, and they acquired these wounds heroically carrying out the struggle against the Soviet Union, and I respect them for that. That needs to be taken into account.”

In addition to pushing for a ceasefire between the Taliban and its adversaries, Gouttierre said the U.N. mission consistently makes clear that in order to gain credentialing from the U.N. and support from key institutions like the World Bank, the Taliban must do a better job of protecting basic human rights and ensuring gender equity.

He said the main barrier to reaching a cease fire accord is the Taliban’s nearly unassailable military position, which gives them little reason to make concessions or accept conditions. Another impediment to the peace process is the nation’s rich opium industry, whose interests diverge from those of the U.N. And a major complicating factor is the support being provided the warring factions by competing nations. For example, Pakistan and certain Persian Gulf states are major suppliers of the Taliban, while Iran and Russia are major suppliers of the opposition alliance.

Taliban and opposition leaders did meet together at several U.N. sponsored negotiation sessions. The representatives arrived for the talks accompanied by armed bodyguards, who remained outside during the discussions. The tenor of the meetings surprised Gouttierre. “It was far more cordial than I had anticipated. These men got along remarkably well, in part because they all know each other. That’s not to say there weren’t disagreements. When offended, Afghans can be exceedingly formidable to deal with.”

At Gouttierre’s urging, the mission began holding intimate gatherings at which representatives of the warring parties met informally with U.N. officials over food and drinks and “where translators were not the main medium for communication and where everybody wasn’t on guard all the time.” He hosted several such luncheons and dinners, including ones in Kandahar, Baamiyaan and Kabul. The idea was to create a comfortable mood that encouraged talk and built trust. It worked.

“In diplomatic enterprises often the most effective periods are at the breaks or the receptions, because you’re sometimes able to get people off to the side, where they’re able to say off the record what they can’t say officially. And that’s exactly what happened. Those of us in the U.N. mission got a better sense of who the Taliban are. They’re not irrational. They do have a sense of humor. And they got a better sense of who we are – that we’re not just officials, but that we also have a long-term interest in Afghanistan.”

Gouttierre said the mission has overcome “high skepticism” on the part of Afghans, who recall the U.N. granted Najeebulah asylum despite his being a war criminal. He said the Afghans’ estimation of the mission has moved from distrust to acceptance. And he feels one reason for that is that the present mission has “more clout and recognition than any previous mission to Afghanistan.” Supplying that essential leverage, he said, is the “unstinting support of influential countries like the U.S., France, England, Russia and Japan.”

Despite recent news stories of military inroads made by opposition forces, especially around Kabul, the Taliban remain firmly entrenched. Gouttierre believes that unless a major reversal occurs to change the balance of power, the Taliban will continue calling the shots. If the Taliban eventually consolidate their power and conquer the whole nation, as most observers believe is inevitable, the hope then is that the movement’s leaders will feel more secure in acceding to U.N. pressure.

Gouttierre said that despite the failure to gain a ceasefire thus far, “the fact remains the two sides are meeting with each other, and that’s the first step in any peace process. We don’t have agreements on anything yet, but at least the channels for continuing dialogue have been opened.”

As Gouitterre well knows, the process of binding a nation’s wounds can be frustrating and exhausting. He stays the course though because he wants desperately to recapture the magical Afghanistan that first bewitched him. “I guess one of the things that keeps me at this is that I am ever hopeful that somehow, some way those admirable qualities of Afghan culture which I came to love so much will to some degree be restored. So I keep pursuing that.”

Related Articles

- Afghan president criticizes timeline for U.S. withdrawal (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Market bombing in northern Afghanistan town kills 3 police, 2 civilians, wounds 15 (foxnews.com)

- The Challenge of Training Afghan Troops, Police (cbsnews.com)

- An Old Partnership Takes a New Turn: UNO-Kabul University Renew Ties with Journalism Program (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Afghanistan: U.S. Intelligence Failures Led To Civilian Casualties (huffingtonpost.com)

King Crawford: Omaha’s very own movie mogul

I go back with Bruce Crawford 30 years. We met for the first time when I was a film programmer/publicist at the University of Nebraska at Omaha and he was a wide-eyed film enthusiast. He specifically approached me about wanting to share his passion for the great film composer Bernard Herrmann, whom he had struck up a correspondence with late in the composer’s life. I had a screening of Taxi Driver scheduled and Bruce asked if he could make a presentation about Herrmann and the composer’s scoring of that film. We didn’t normally have speakers as part of our campus film program but something about Bruce’s magnificent obsession and tenacity convinced me to agree. Flash forward about 15 years, when I was a fledgling freelance journalist and Bruce was first making a name for himself with the radio documentaries he did, including one on Herrmann, and with the revival screenings he staged of film classics.

The following is the first of many stories I’ve written about Bruce and his work as a film historian and impresario. It appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). He’s since put on dozens more film events.

King Crawford: Omaha’s very own movie mogul

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

There’s a bit of Elmer Gantry in Bruce Crawford, the dynamic Omaha film historian/promoter whose sold-out screening of the original 1933 classic King Kong unreels Saturday, May 30 at the Indian Hills Theater.

With his boyish good looks, magnetic presence and penchant for hyperbole he exudes the charisma of a consummate huckster and the passion of a confirmed zealot. An evangelist for that old time religion called the movies, he often describes his devotion in missionary terms and pays homage to Hollywood’s Golden Age through gala events and elaborate documentaries full of his characteristic verve and adoration.

And with its rich, delirious mix of mythology and metaphor, Kong is an apt choice for cinephile celebration and reverence. This ultimate escapist film combines still impressive visual effects with an outrageous Beauty and the Beast fable played out in a ripe Freudian landscape. Unlike, say, Godzilla, it taps our deepest fears and desires.

Crawford’s passion began in his native Nebraska City, where he had a born-again experience at the movies. It came when his parents took him as a child to see Mysterious Island, a 1961 Jules Verne-inspired fantasy adventure featuring special effects by Ray Harryhausen.

“I loved the effects and the creatures and the fantastic Jules Verne story. But it was the music that hooked me more than anything else,” Crawford said from the movie memorabilia and art-filled northwest

Omaha apartment he shares with wife Tami. “I remember when the music hit me. It was the opening with the boiling ocean and the Victorian lettering rolling across the seascape. I can’t quite find the words for it, but something connected. t was almost like a diamond-tip bullet hit me between the eyes. This music…wow! I was so overwhelmed by its beauty and majesty. I wasn’t old enough to read yet, so I asked my parents where the music came from.”

Bruce Crawford

When he found out it was by legendary composer Bernard Herrmann, he felt “a compulsion” to find out everything he could about the man and his work. He had a similarly dramatic reaction to hearing a cut of the love theme to Ben-Hur. Despite his unfamiliarity with the movie and the composer, Miklos Rozsa, he felt an affinity for each. “The music was sooooo beautiful. Even without knowing it was a Biblical story I felt the Judaism. I felt the ancient world. Like with Mysterious Island I felt another connecting link in my life. That this was part of my destiny. I said, ‘I’ve got to see what movie this music goes to.’”

He finally did see Ben-Hur Christmas night in 1970, and it proved a revelation. “It changed my life. I’ve never been so haunted and moved by something as I was by it. It was so profound, so literate, so poetic. I knew I’d seen a masterpiece. And somehow, on some psychic or intuitive or synchronistic level, a little boy in Nebraska City had this connection with these world-renowned musicians and filmmakers. I knew then I was meant to know these people and to do something with them.”

Amazingly, his life has intersected with the very objects of his devotion. As a precocious teen he began corresponding with the imposing Herrmann, the composer for such film classics as Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo and North By Northwest. Upon Herrmann’s death in ‘75 (after finishing the fever dream score to Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver) Crawford drew close to his family. By ‘88 he’d become an authority on the man and produced an acclaimed documentary on him which has since aired over many National Public Radio affiliate stations and over the BBC in Great Britain.

Crawford struck up a similar acquaintance with Rozsa and shortly before the composer’s death in ‘95 completed a documentary on him and his music that also garnered strong critical praise and wide air play.

Music has always spoken most strongly to Crawford. “My first and foremost love is great music, and for me film scores represent the 20th century’s answer to the great symphonies of the past 300 to 400 years. A film score is like a grand opera in a sense. It can tell what actors can’t say.”

Movie special effects also hold him enthralled. As a high school student he made an award winning short using the same kind of stop-motion animation techniques as Kong. He began networking with FX artists and those contacts led him to the dean of them all — Harryhausen. In ‘92 Crawford coaxed Harryhausen, fresh from receiving an honorary Oscar, to attend an Omaha tribute in his honor. The men are now close friends.

Ray Harryhausen

The tribute proved a hit and spurred subsequent film events. The biggest to date being the 35th anniversary showing of Ben-Hur, for which Crawford scored a coup by making Omaha the first stop on the restored film’s special reissue tour and by getting family members of the film’s legendary director, William Wyler, to attend.

At a screening of Gone with the Wind he brought co-star Ann Rutherford and added atmosphere with women in period hoop skirts. For the Hitchcock suspense classic Psycho he secured an appearance by star Janet Leigh. Family members of late-great director Frank Capra (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington) and producer Darryl F. Zanuck (The Longest Day) came at Crawford’s invitation to Omaha revivals.

Many wonder how someone so far removed from the movie industry is able to gain entree to rarefied film circles, land interviews with top names (from Charlton Heston to Leonard Maltin), arrange celebrity guest appearances and enlist the aid of corporate sponsors. Crawford’s personal charm and genuine ardor for classic movies, and for the artists who made them, help explain how he does it.

Then too there’s the grand showmanlike way he exhibits old movies. “The way they’re meant to be, but so rarely, seen,” he said, meaning on the big screen — with all the puffery, ballyhoo and flourish of a Hollywood premiere. For his 65th anniversary showing of Kong, which has been fully restored, he plans searchlights, a 30-foot tall Kong balloon, limousine-driven guests, a pre-show and a post-autograph session.

“What I’m trying to do is recapture the magic of going to the movies I felt as a kid,” he said, “and add to it with the glitz and the glamour. You get your money’s worth at a Crawford show, don’t you think?”

Kong’s special guests will include Harryhausen, who’s flying in from his home in London, renowned science fiction author Ray Bradbury (Fahrenheit 451) and noted film historian Forrest Ackerman. The three grew up together in California and were equally enchanted by Kong.

Harryhausen, who later apprenticed under the film’s effects master, Willis O’Brien, on Mighty Joe Young, credits Kong for inspiring his life’s work. “I was 13 when I saw it, and I haven’t been the same since,” he said by phone from London. “It left me startled and dumbfounded. It started me on my career. That shows you how influential films can be.”

Bernard Herrmann

The Kong pre-show or “live prologue,” as Crawford calls it, will recreate the film’s native ceremonial ritual — complete with dancers in painted faces and grass skirts — performed for Kong’s original run at the Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Los Angeles.

On his Kong Web page Crawford promises an evening “in the Sid Grauman tradition.” Crawford is indeed a Grauman-type impresario with a flair for extravaganza. He also resembles the P.T. Barnum-like Carl Denham character in Kong who charters the ship and leads the expedition in search of the big ape. In an early scene the first mate asks the skipper about the irrepressible Denham, “Do you think he’s crazy?” “No,’ says the captain, “just enthusiastic.” Likewise, Crawford’s undaunted fanaticism is that of the true enthusiast. His fervor largely accounts for the warm reception he’s been accorded by Hollywood insiders.

“I’m delighted he takes it so seriously and takes the initiative to try and present pictures the way they were presented in the early days,” said Harryhausen. “What you need is somebody with enthusiasm for these types of things. Bruce has that, and it’s wonderful.”

Gerry Greeno, Omaha city manager for the Douglas Theater Co., whose Cinema Center hosted past Crawford events, said, “He has that exuberance that generates interest and gets people to go along with him…and he’s not bashful about it. For some it might wear a little thin, but he puts a lot of time and effort into these events. He loves doing it.”

Bob Coate, who co-produced the Herrmann-Rozsa documentaries at KIOS 91.5-FM, where he is program manager, said he fell under the Crawford spell when the promoter pitched him the idea. “I’d never produced anything like that before. He kind of got me excited about doing it. His enthusiasm is definitely infectious.” Coate, now part of the Crawford coterie, added, “He’s a driving force. I know these events are tons of work for him, and wear him out, but I think he gets energy from doing them.”

As Crawford tells it, “I try to get people to do things they might not normally do, which I’m told I do a lot of. It’s being persuasive. You have to have that extravagant enthusiasm…that charisma. Some people keep it subdued and withdrawn. I choose not to.”

Until Coate approved the Herrmann program, Crawford had run into dead-ends trying to get it off the ground. “I went to several public radio stations and they said, ‘It can’t be done.’ Of course that went in one ear and out the other. I was determined to do it come hell or high water. Fortunately, Bob (Coate) was a Herrmann fan.”

The pair collaborated for months. In typical Crawford style he pushed the envelope by making the finished product two and a half hours long. Upon hearing it, the feature most listeners remark on is the unusually long (often complete) musical passages from Herrmann’s radio, film and concert hall career and rather spare but informative narrative segments. The same approach is used with the Rozsa project.

Miklos Rozsa

“My programs are really audio musical biographies about the subject and his music,” Crawford said. “The thing that makes them stand out is that they’re 60 to 70 percent music and 30 to 40 percent discussion. There was no model I was aware. I didn’t know what the parameters were. And of course the rest is history.”

He refers to the favorable response the programs netted, especially the piece on Herrmann, who’s a cult figure. Crawford has heard from many famous admirers. “It’s considered the most extensive, the most comprehensive, the most successful documentary ever done on any composer of the 20th century,” he said. “That’s just not my opinion. That’s the opinion of Ray Harryhausen, Ray Bradbury, Danny Elfman, Jerry Goldsmith, David Copperfield, Robert Zemeckis…”

Part of his charm is the wide-eyed, gee-whiz glee he takes in his own achievements. In the Wonderful World of Bruce Crawford, there are only “huge” successes; “amazing” feats; movie “masterpieces;” and his own “almost superhuman” energy. When he goes on a riff about the accolades and national media coverage, he punctuates his speech with a rhetorical “Isn’t that something?” or “Isn’t that incredible?”

Well, who can blame him? He’s been brazen enough to develop world-class film connections and visionary enough to use them in meaningful ways. He’s seen himself become a touchstone figure for film buffs who bask in the glow of his and his famous friends’ celebrity. He’s been commissioned to write articles for major film publications. His services as a documentary producer and event promoter are in much demand.

This self-styled movie mogul rules over a niche market in Omaha for the celebration and veneration of classic films. Call him King Crawford. Still, even he can’t believe his dreams have come true.

“My God, who would have ever thought this was attainable? I didn’t see it coming. I did have a desire, which was obviously intense, but I didn’t know where it would lead. And then to have these giants respond to me, and not only respond, but become pretty close friends — that just doesn’t happen, man. Yeah, syncronicity.”

Perhaps it’s no coincidence then he and Tami live in Camelot Village.

“My life is like a strange sort of destiny.“ he added. “I don’t know how or why that is. That’s what serendipity is I guess. Amazing. Isn’t that wild?”

Related Articles

- Revival House: “We all go a little mad sometimes …” (popdose.com)

- Hitchcock’s Psycho At 50, The Sounds Of Violence (huffingtonpost.com)

- Revival House: Seven Great Rejected Film Scores (popdose.com)

- Listening to Taxi Driver. (slate.com)

- Hitchcock horror under the hammer (thejc.com)

Magical mystery tour of Omaha’s Magic Theatre, a Megan Terry and Jo Ann Schmidman production

UPDATE: Ah, it’s spring again, and that means it’s time for the Great Plains Theatre Conference in Omaha, where many established and emerging playwrights and other theater professionals from the far corners of the U.S. gather their collected energies for the theater arts. As a journalist who interviews some of the guest artists for the conference, which this year is May 28-June 4, I enjoy dropping the name Megan Terry and mentioning that she lives in Omaha. It never fails to elicit a response: first, affection and admiration for the work of Terry, a great American playwright; and then surprise and delight that she lives in the host city for the conference. What follows below is an article I did five or six years ago on Terry and how and why she came to resettle in Omaha from New York and what she did here.

I only attended a couple productions by the Omaha Magic Theatre, an avant garde, experimental stage company led by two women who against all odds made their ground-breaking theater a success in Omaha, Neb. One of the partners, Jo Ann Schmidman was from here and made her reputation here with the theater. The other, Megan Terry, made a name for herself in New York long before joining Schmidman in Omaha at the Magic Theatre. They closed their theater some years ago and the two women who created such a distinct niche for themselves seemed in danger of fading into obscurity when I caught up with them and wrote the following story, which appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). Basically, I wanted to capture in print just how extraordinary what they did was and just how compelling they are as individuals and as partners.

Magical mystery tour of Omaha’s Magic Theatre, a Megan Terry and Jo Ann Schmidman production

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Even in the counter-cultural maelstrom of the late 1960s, the idea conservative Omaha could support an experimental theater with a strong feminist, gay/lesbian bent defied logic.

Well, that’s the point, isn’t it?

When native Jo Ann Schmidman founded the Omaha Magic Theatre in 1968 as a center for avant garde expression in the Old Market, she followed her muse. The fact she was barely out of her teens, between her sophomore and junior years as a Boston University theater major, only added to what many must have regarded as folly. That’s not how she saw it though.

Instead of resistance, “what we discovered was quite the opposite…open-minded people with a work ethic,” said Schmidman, an Omaha Central grad weaned on local children’s theater, the work of an adventurous wing of the Omaha Community Playhouse and a summer studying in Northwestern University’s prestigious theater program.

“The pioneering spirit and the quest to work with your own hand, out of your own soul, is an Omaha, a Midwestern trait and that’s exactly the kind of theater I was interested in doing. It didn’t have anything to do with being radical, it had to do with being homemade and what is inside of people,” she said at a Great Plains Theater Conference (GPTC) panel. “It wasn’t about shocking people, it was about giving them a vehicle to reflect, a way to understand one’s self better, to go on a spiritual journey.

“I knew it was a perfect place to start an alternative, experimental theater…there was nothing like it and to date there is not another alternative theater in town. It’s either realism or naturalism.”

In a 1996 Theatre Quarterly interview she said the very qualities of this place that isolate it from the theater mainstream allow for exploration: “There is something incredibly expansive about this area and about the people that live here. The extremes of temperature, I believe, allow extremes of creation.”

She originally opened OMT as a summer enterprise. Grad students from Boston U. rounded out the company. The first season was heavy with plays by European absurdists Genet and Brecht. American works came later, including The Tommy Allen Show by Megan Terry.

The paths of Schmidman and Terry first crossed years earlier.

A Mount Vernon, Wa. native, Terry has lived a life in theater. She was “brought up” in the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, mere blocks from the home of her pioneer grandma. “I just scratched at the door until they let me in,” she said of Playhouse founders Burton and Florence James. After completing her theater studies in the Pacific Northwest Terry tried for an acting career in New York, all the while journaling. “Pretty soon, I thought my own dialogue was better than the stuff I had to perform. Little by little I started writing.”

“At this same time were all the protest movements, the marches. There was a huge political-social-cultural revolution. The new music, the new art, the Action painters and Abstract Expressionists, were at their zenith. All these things were converging,” Terry remembered. “I’d go to Washington Square and hear Bob Dylan and Joan Baez before they were famous. There were about 35 marvelous playwrights all working in New York City and we could all walk to each other’s theaters, so it was like, Can you top this? We just played off of each other.

“I mean, it was all there. I see theater really as a conservative art, where it takes from everything else and I think American jazz had to do what it did and American painting had to do what it did before our kind of theater could happen, because the other arts feed you.”

Terry churned out plays at an amazing clip, at one point having a new one produced every month. Edward Albee co-produced a double bill that included her Ex-Miss Copper Queen On a Set of Pills at the Cherry Lane Theatre. She was a founder of the legendary Open Theatre, an experimental company that produced her work, eventouring it nationally. Other Terry plays were performed at the chic La Mama. Another at the Circle Rep. Still another at the Actor’s Studio.

Along with Sam Shepard, a fellow founder of the Open Theatre, she was identified as one of America’s most promising new playwrights.

“At a point I worked with very strong men in the ‘60s. Joe Chaikin, Tom O’Morgan, Peter Feldman,” said Terry, who developed Viet Rock in a Saturday Open Theatre workshop that also produced Hair. Rock was perhaps the first major work of art to deal with the Vietnam War. When Chaikin and Feldman “took it (the play) away from me,” she said, “a big confrontation” ensued.

Aptly, Terry’s and Schmidman‘s paths crossed in theatrical fashion.

“I met her [Schmidman} in Boston when I was asked to come to write the bicentennial celebration for Boston University’s theater school” Terry said. While in Bean Town she joined the throng gathered for a protest on the Boston Common. Out of the crowd Terry estimates approached a million people, the two found each other.

“I don’t go to rallies but I went to an anti-war rally where I met her by mistake, doing guerrilla theater,” Schmidman said. “I found her to fix my tin foil mask.” “Her mask had come off and I helped her with it. It’s just absolutely true,” Terry said.

Schmidman admired Terry’s work. Indeed, she said, “I had the top of my head blown off” by the work of Terry and her cohorts. The two got to know each other when Terry later went to Boston U. to workshop her Approaching Simone. Terry cast BU theater students. None of the perky, blonde, blue-eyed, well made-up girls fit what she wanted. So, “I designed an improvisation where one person had to stand off all of the rest of the kids in the school,” she recalled, “and Jo Ann had the power to stand them off. I said, ‘Ah ha, I can write this play around her. There’s the power I’m looking for.’’ Jo Ann WAS Simone. The play ran off-Broadway at Cafe La Mama, becoming the first student-cast production to win an Obie.

Their relationship grew when Schmidman toured with the Open Theatre, “It was a magic, perfect fit,” said Schmidman. Terry visited Omaha in 1970 to see Schmidman’s production of the Tommy Allen Show.

“It was a better production then I had done out in Los Angeles. I had to admit it,” said Terry. “I said, ‘This is really good.’ I mean, she was showing me things about this play I didn’t know were there.”

With some prodding, Terry set her sights on this place, moving here in 1974.

“When the Open Theatre closed and I saw what Jo Ann was building here,” Terry said, “I could easily make that transition. She’s a great director.” Still, it was a huge leap of faith. “She was leaving where one made it in the theater. Plenty would not leave New York City, period. But for Megan I never heard a second thought,” Schmidman said.

The difference being in Omaha Terry didn’t have to take a back seat to anyone. It’s why leaving the center of the theater world was not such a hard move. “I always felt like I was camping out in New York as it was,” Terry said. “I always felt like it was temporary. The feminist movement freed me from being stuck in New York and being in that life.” She said she ended up being far more productive here.

Schmidman said since Terry’s “ego was not at stake,” Omaha made sense, as here she could “work every day within a viable company” that would produce her plays. “Megan is the kind of playwright that writes for a company of people, which is how I lured her out here.”

As Schmidman did before her, Terry found the possibilities for theater here “wide open.” Terry’s presence lent OMT instant credibility. Her career hardly suffered for the move. Her prodigious output (60 plays) continued. Her work has been taught or performed across North America, Europe, South America and beyond.

The theater became a year-round venue for the most mind-altering work. It changed locations a few times before settling at its present downtown site on 16th street in a former department store next to King Fong’s.

More than two decades before the Blue Barn Theatre opened, these women were doing Witching Hour work that made electric cool aid acid trips seem tame.

Terry and Schmidman recently sat down for interviews at the theater, an open, tiled space with a stripped-down ‘50s-vibe. They are a study in contrasts. Terry has the pale, soft, rounded features and sweet, doe-eyed look of an ingenue turned mature matron. Schmidman is a slim, dark-featured, hard-angled figure whose severe face and brooding demeanor signal intensity. Little Bo-Peep and Gothic Queen. Both exude a manic fervor on low simmer. They listen intently. They laugh easily. Each interrupts the other to complete a sentence, the way longtime companions do.

The two ceased producing at OMT a decade ago. A new group of artists use the space and the name today, inspired by what the two women did to push theater’s boundaries. Terry and Schmidman long intended handing over the OMT to a new troupe. Groups came and went. None stuck. In 2004, fashion designer Julia Drazic and a coterie of designers, visual artists and musicians hit it off with the women and took over the space. The resulting multi-media, multi-layered shows defy categorization. Sound familiar?

Schmidman, who advises the group, calls Drazic “a natural born producer.”

Drazic and Co. realize the heavy legacy they carry with the OMT name.

The Growth of the Magic Theatre

A generation apart, Terry and Schmidman each studied and rejected old theater concepts in favor of a freer model unbound by, in their minds, rigid constraints and assumptions. While Schmidman’s a militant adherent of independence and a harsh critic of conventionality, Terry’s more politic.

With Schmidman as artistic director and Terry as resident playwright, OMT showcased works by playwrights thick in the canon of the American avant garde: Ron Tavel (Kitchenette), a collaborator with Andy Warhol on the Pop artist’s early narrative films; Paula Vogel (Baby Makes Seven), whose play How I Learned to Drive won a Pulitzer; and Obie and Pulitzer winner Sam Shepard (Chicago). Guest directors helmed some shows. Visiting playwrights-directors did workshops. It was all about change and challenging the status quo, even the very definition of theater.

Schmidman was well-suited to the task said New York playwright Susan Yankowitz: “Jo Ann has flung herself into roles, as actor-as director, with unusual courage and confidence, qualities that make her especially friendly to risk.”

Everyone contributed ideas to a play’s development. Everyone participated in its performance. Devoid of the usual barriers, like a proscenium stage, audiences, actors, stage hands, words, sets, music, costumes, sculptures, movements and projected images became equal elements in total, multi-media, sensory immersions.

Terry’s transformational style, in which actors interchange parts or morph into objects, was aided by soft sculptural costumes. Crew handled lights, music and sets not behind a curtain or in shadow, but out in the open, for all to see. Same way with actors changing costumes. It was part of the experience, as in the spirit of the ‘60s New York “happenings” Terry witnessed.

The experience, Omaha theater director Jim Eisenhardt said, could be formidable. “Oh, absolutely, it was intimidating, but it was a great shared experience, too.”

“In those days our object was to push previously established ideas of what theater was in new directions,” said Schmidman. “To create absolutely contemporary theater…in other words, to create theater that had to do with our lives, living and working in Omaha, Nebraska, because that’s what we were doing. So it was a pretty lofty task we set for ourselves. It was to reinvent what does theater look like, what does it sound like, what is it.

“And certainly there were plenty of roots in people before us. This was the end of the ‘60s, so we had Cafe La Mama, Cafe Chino, the Open Theatre” as models to follow.”

OMT fit in well with the Old Market’s head shops and art galleries. It had the entire building that contains the Passageway. The company lived communally there and in a loft across the street, with Terry cooking big stews from French Cafe refuse. The theater became a self-supporting operation. Members did not need to take second jobs. By taking risks rather than playing it safe the women made OMT a successful, recognized home for contemporary theater.

“We were producing this fine theater that commanded national grants and international respect at a time when it wasn’t being given to the opera or the symphony,” Schmidman said. “This tiny little theater was getting direct National Endowment for the Arts support in ever escalating amounts because the work was good. They (the NEA) came out each year to see the work.”

The two women’s imprint is undeniable.

As if being an experimental theater were not enough, OMT dared to be a “‘gay,’ ‘radical feminist,’ ‘lesbian’ theater‘” on top of it, said Rose Theatre artistic director James Larson. “None of that existed in Omaha before.” Given that, he said, “it is extraordinary the Magic Theatre could survive for 30 years.” He added it’s “impressive” OMT could command large grants and he admires how “resourceful” Schmidman and Terry were in replenishing the company over time.

OMT built loyal followings for experimental work that proved accessible. “Once the people saw the work, whether they knew what they were seeing or not, they responded to it,” Schmidman said. One reason may be the extensive research Terry did for “the big community pieces” OMT did, like her Kegger, that dealt with under age drinking. Once they had a hit, they kept it in front of audiences for a steady cash stream. OMT toured Kegger for three years, nearly surviving on its proceeds alone.

“Touring is what kept us going,” Terry said. “It helped enable us to keep doing what we were doing, reaching out to all of the communities, getting to know people at different universities and arts councils.”

Q & As usually followed shows. Often, the theater invited scholars or experts to lead discussions related to the themes/issues raised. Audiences weighed in, some testifying, as in church, to how the plays resonated with their lives.

Terry and Schmidman set a high standard.

Larson, a playwright whose doctoral thesis is on Terry, worked with OMT for 15 years. He said, “There was a time in the ’60’s and ’70’s when Megan was considered one of the top three female playwrights in the history of American Theater” along with Lillian Hellman and Susan Glaspell. “Then more female playwrights emerged, and Megan is still remembered as the leading political/feminist playwright.”

Noted New York playwright and poet Rochelle Owens said, “Megan Terry’s plays explore the boundaries of American culture…Her use of ‘transformation’ marked her as one of the most original dramatists of the experimental theater of the 20th century.” Owens said Schmidman is a “brilliant artistic director” who, along with Terry, is “an inspiration to theater artists.”

OMT was an island unto itself, isolated, by choice and by perception, from the larger theater community due to the work it did and the single-minded focus, some might say zealousness, the women displayed. “We didn’t play the local theater game,” Terry said. “Or socialize,” Schmidman interjected. “We were too busy working.”

Its 30-year run only ended, in 1998, when Schmidman and Terry, partners in life and in the theater, reached a point of exhaustion. The two share a house together in south O. The theater’s old touring van is parked on the street. The house is obscured by the van and an overgrown garden in front that seems an apt metaphor for two artists whose wild, creative vines are intertwined.

“When we closed we were playing to full houses every night,” Schmidman said. Even if she and Terry were weary, why walk away from such a good thing? “It’s just, there are other things to life. There are other art forms, like living,” Schmidman said. Besides, she said, it just never got any easier, especially the struggle to win grant money. All the late nights of preparing mountains of paperwork for grant applications and then waiting on pins and needles for a yes or no wore on them.

“The audiences were great, the work was great, but getting the damn money was as miserable as ever,” Terry said.

They closed shop to archive OMT’s and Terry’s remarkable bodies of work, all of which is housed in the Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley.

Thirty years of original, groundbreaking work unseen before here, some seen for the first time outside NY. Tours across Nebraska, Iowa. All “musicals,” not with familiar show tunes, either, but original, contemporary, music.

“The biggest myth of the American theater is people will only go to a show if they can leave the theater humming the tunes or they’ll only go to something that sounds like something else. That has not been our experience,” Schmidman said.

The Magic made its mark far beyond Omaha, too. Terry and Schmidman collaborated on the lyrics and book, respectively, for Running Gag, staged as an official selection of the 1980 Winter Olympic Games in Lake Placid, NY.

In 1996 the Magic represented America in the Suwon Castle International Theatre festival in Suwon, South Korea, just south of Seoul. Terry, Schmidman and Co. performed Star Path Moon Stop outdoors before a crowd of some 5,000 squatting spectators.

“It was fabulous,” Schmidman said. “They come from a shamanistic tradition, so they really got into our kind of theater,” Terry said. “They embraced it because it’s quite like their traditional, very broad, emotional, spectacle theater,” Schmidman elaborated. “Yes, their theater is very episodical and relies on fabulous stage effects,” Terry added. The festival appearance followed workshops OMT did the year before in Seoul. The theater traveled abroad once before, when they toured Body Leaks at a women’s fest in Canada.

From OMT’s inception, Schmidman surrounded herself with collaborators drawn from many disciplines/backgrounds. Rarely did anyone have formal theater training. There were painters, musicians, poets, hippies and freaks. Among the noted artists to work with OMT were painter Bill Farmer, musicians Jamel Mohamed and Luigi Waites and composer John Sheehan. Sora Kimberlain arrived as a visual artist and ended up doing set design, acting, writing and directing.

“The bottom line was if theater reflects life and if we’re creating a brand new way of performing, well, you sure don’t need to go to school for it,” Schmidman said. “You need to open your heart, open your soul, give yourself over to the work and do what it tells you.”

EDITOR’S NOTES: While Schmidman and Terry closed the original OMT a decade ago, they’re hardly inactive. Terry still writes, accepting commissions from theaters like The Rose in Omaha. Schmidman no longer directs but she consults/mentors the new OMT and other young theater artists.

In 1992 the Magic Theatre produced a book, Right Brain Vacation Photos, that serves as a great OMT primer, the American avante garde and experimental theater. Look for it at your local library or on Amazon.com.

Related Articles

- A day in the life of a theatre (thestar.com)

- Take in Some Indie Theater at This Year’s Spark Showcase (phillyist.com)

- Gotham goes for a ‘Ride’ (variety.com)

- Omaha Arts-Culture Scene All Grown Up and Looking Fabulous (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jo Ann McDowell’s Theater Passion Leads Her on the Adventure of Her Life: Friend, Confidante, Champion of Leading Playwrights, Directors, Actors and Organizer of Major Theater Festivals and Conferences (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- All Trussed Up with Somewhere to Go, Metropolitan Community College’s Institute for Culinary Arts Takes Another Leap Forward with its New Building on the Fort Omaha Campus (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Ushers in New Era of Omaha Theater (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Q & A with Edward Albee: His Thoughts on the Great Plains Theatre Conference, Jo Ann McDowell, Omaha and Preparing a New Generation of Playwrights (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Great Plains Theatre Conference Grows in New Directions (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Playwright John Guare Talks Shop on Omaha Visit Celebrating His Acclaimed ‘Six Degrees of Separation’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Q & A with Theater Director Marshall Mason, Who Discusses the Process of Creating Life on Stage (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Three old wise men of journalism – Hlavacek, Michaels and Desfor – recall their foreign correspondent careers and reflect on the world today

As a kid I watched John Hlavacek on a local network television affiliate’s newscasts and documentaries, and as a young man I was aware of him serving on the Omaha City Council, and operating his own travel agency. I vaguely knew that he had been a foreign correspondent. It was only a few years ago though that I met him for the first time and got to know more of his story. He and his late wife Pegge were both reporters in the Golden Age of American journalism. Their life stories of living and working around the world are as amazing as those of the historical events and figures they covered. In the last few years John has had published several books authored by himself and Pegge that recount their adventures. I have also posted the story I wrote about John and Pegge and their adventures, but the following piece is about John and two old reporter friends of his from back in the day. The three men hadn’t seen each other in decades until John arranged for their meeting in Omaha for a panel discussion. I covered the event and wrote this story for The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Three old wise men of journalism – Hlavacek, Michaels and Desfor – recall their foreign correspondent careers and reflect on the world today

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

They were three young lions of American journalism when they met far from home, a long time ago. John Hlavacek of Carleton College (Minn.) and Jim Michaels of Harvard were green United Press foreign correspondents based in post-World War II India. In wartime Hlavacek trucked medical supplies over the Burma Road for the International Red Cross. Michaels drove an American Field Service ambulance. Each was imprisoned there: Hlavacek for days; Michaels for months. New Yorker Max Desfor covered the war in the South Pacific as an Associated Press photographer.

The paths of these three men crossed in 1946, when their lives-careers intersected with India’s historic bid for independence from British colonial rule. Last spring, they came together for the first time in 60 years with the publication of a book, United Press Invades India, by Hlavacek, an Omaha resident who invited his colleagues to participate in public forums about their intrepid reporting days. The men shared stories and observations during two panel discussions in Omaha.

After being out of touch all that time Hlavacek began the process of reestablishing contact with his old colleagues while working on his memoir. Facts needed checking and where Hlavacek’s memory faltered, he relied on Desfor and Michaels to fill in the blanks. By the time the book was completed, Hlavacek suggested he and his comrades reunite. The men still correspond today.

John Hlavacek

The book that helped bring the old colleagues together was Hlavacek’s second volume of memoirs based on his overseas adventures in India and China, where he taught English in an American mission school in Fenyang as part of the Carleton in China exchange program. Hlavacek now has a third volume of memoirs out, Freelancing in Paradise, that recounts the years he and his wife Pegge, a fellow journalist he met and married in India, filed stories from the Caribbean for national media outlets. He’s also published two books authored by Pegge about her own far flung news career and the couple’s remarkable feat of raising five children while working in India, New York, Jamaica and Omaha.

For Hlavacek and Michaels, now in their late 80s, India began long, distinguished careers in journalism. As bureau chief in Bombay, Hlavacek built up UP’s presence there and under his aegis the news service proved a formidable rival to their bitter rival, the AP. He won what’s now called the Edward R. Murrow Fellowship for study at Columbia University, he covered the Caribbean and after moving with his family in the early 1960s to Omaha, where he was a television news correspondent/commentator, he filed a series of reports from Vietnam on area residents serving in the war.

Michaels got the scoop of a lifetime when he broke the story of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination in 1948. He joined Forbes Magazine in 1954, was made editor in 1961, a post he held until 1999. He’s credited with turning Forbes into one of the world’s most read financial pubs. A VP today, he can be seen Sundays on Forbes On Fox.

Before India, Desfor already made memorable images: of the Enola Gay crew upon their return from the mission that dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima; and of the Japanese surrender to the allies on the USS Missouri. Soon after his arrival in India in 1946, he snapped a famous picture of Gandhi and India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in an unguarded moment of friendship. “You see the interchange, the compatibility, the simpatico. It’s just an enormous moment,” he said. The iconic pic was used as the basis for a popular Indian postage stamp.

Desfor won a Pulitzer Prize for news photos for his work in the Korean War. In all, he shot five wars, many conflicts and much civil strife. He later served as an AP photo executive/editor before retiring in 1979. That same year though he joined US News and World Report as director of photos. He made his 1984 retirement permanent, but he’s till snapping pics, only now with a digital camera. He’s 93.

Max Desfor posed in front of picture taken of himself during the Korean War

These young lions turned wise old men of journalism reunited for panel discussions in Omaha in 2006. They took to their role as pundits well. They spoke about the momentous events they reported on, the way the news biz has changed and how the India and China of today differ from the developing nations they knew then.

Hlavacek said the troika may be the only surviving American journalists to have met Gandhi. While his colleagues minimize Gandhi’s ultimate influence, Desfor said “he had a moral effect” of lasting import. Michaels said by the end Gandhi was “almost irrelevant” for opposing “industrialization or modernity. Had Gandhi lived, he said, “he would have been loved but nobody would have paid attention to his views.”

The ascetic led a huge movement yet was quite approachable. Unlike today’s restrictive climate, the press had unfettered access to major public figures then.

“A journalist’s access to events in those days was so much more intimate than it is today,” Michaels said. “Gandhi was a world figure, yet he had these prayer meetings when he was in Delhi that the public could come to. If you got there early you could sit right up in front and ask him questions. Or, as John (Hlavacek) did, you could go right up to him and ask for an interview. Today, you wouldn’t be able to get through the masses of hired guards, spin meisters, the whole lot.”

“Once, I wanted to interview the number two man in the cabinet of Independent India, Vallabhbhai Patel, a very important figure in Indian independence,” Michaels said. “So, I drove up in my little car to his place, knocked on the door, a servant answers and says, ‘What do you want?’ I say, ‘I’m from the United Press of America — I’d like to interview Vallabhbhai Patel’ He says, ‘Wait a minute,’ takes my card and five minutes later ushers me into the garden, where Patel and I had tea together and I had an interview. That kind of immediacy today simply does not exist.”

When Hlavacek wanted to interview Mohammed Ali Jinnah, a Muslim leader in the free India movement, he simply stopped by his flat. He had similar access to presidents (Nehru, Indira Gandhi), religious leaders (the Dalai Lama), royalty (Aga Kahn) and dictators (Juan Peron of Argentina, Zaldivar Batista of Cuba).

“There are many great stories I had the opportunity to cover,” Hlavacek said. “It was interesting. I had a lot of fun. I had a lot of worries from time to time, too. And you were always in competition. You were always trying to beat someone.”

“It was a wonderful era for being a correspondent,” said Desfor, who with his Speed Graphic made pictures of great personalities that “will live forever in history books. This is what gives me such great pleasure,” he said.

When Michaels arrived at the scene of the estate where Gandhi lay fatally shot, he was among the first there. The grounds were open and he could move freely about to ask questions and make observations. After sending off his first dispatches at a nearby cable office, he returned to find the area cordoned-off by police and a large group of reporters and peasants gathered outside the closed and guarded front gates. The reporters there earlier with him were now inside.

“I thought, Oh, my God, I’m going to get beat on this story. I better do something,” Michaels said. “So I went around the back. I knew the area pretty well. And I climbed through the hedges and, wow, staring me right in the face was an Indian constable. I desperately searched in my wallet for my old Geneva card, which I carried as an ambulance driver during the second world war. I flashed this card, which was very impressive, and he said, ‘OK, sahab.’ So I got in. I saw as they brought Gandhi’s body out on the balcony for the people to see. I saw a famous woman photographer (and correspondent) for Life Magazine, Margaret Bourke-White, thrown out physically when she refused to stop taking pictures.

“I saw all these great Indian leaders sitting around crying. I witnessed Nehru, the first prime minister of India, get up on the wall with tears streaming down his face declaring, ‘The father of our country is dead.’ I witnessed all these scenes.”

The phalanx of competing news groups was far smaller then, too, compared to the unwieldy mobs that descend on news events today.

“The independence of India was one of the great events of the century. It was huge news. Yet it was covered by less than 100 journalists,” Michaels said. “When Hong Kong became independent less than a decade ago, there were 8,000 journalists covering it and the ones that got there had to cover it by watching it on TV. Today, everything is staged. Access to events is tightly controlled.”

In the process, Michaels said, “something is lost between what you read and what happens. The whole nature of the profession has changed — I don’t think necessarily for the better. The news business today belongs more to presenters.” “You have to be an actor,” Hlavacek interjected.” “You have to be a performer,” Michaels agreed, “and what you get is filtered through these presenters.”

Another major difference between then and now is the rate at which news is disseminated. Filing stories from the field in Third World nations once meant getting the news out via mail or cable or teletype, all of which took time. Sometimes just getting from a news event to a dispatch office could take hours of travel. Now, stories can be filed from the most remote or dangerous regions, even war zones, almost instantaneously due to satellite phone lines and the Internet.

“The speed of communication is what’s really changed,” said Hlavacek, who adds “the 24-hour circuit” of news coverage puts hard copy newspapers in a tough spot. “You used to break a story in a special edition. It’s too late now.” Michaels believes the ever growing online info world “is killing newspapers.” To those who worry a point-and-click universe prevents analysis, Hlavacek said, “No, it doesn’t, but this is spot news and it never did. Analysis can come later.” He marvels at “the emergence of the Internet” and is encouraged that “there’s so much information out there. I don’t think you can control it. At least I don’t see that you can.”

The dynamic economies and rising technocracies of India and China have caught the men’s notice. Michaels often goes back to India, where he’s interviewed current prime minister Manmohan Singh. Michaels said India’s ascendancy “is one of the great unheralded revolutions of our time.” He said the planned socialist state under Nehru and his successors resulted in an India that “stagnated from the time of independence right through 1989.” Michaels, who calls Singh “a very impressive man,” credits him with engineering “a revolution from the top” that urged Indian leadership to abandon the old system in favor of “a free enterprise model.” The result, he said, is a “booming” economy. While India prospers, its caste system’s inequities still pervade the society, said Hlavacek, who’s also been back. The India-Pakistan divide, they agree, is one born of religious-political differences.

Last fall Hlavacek visited the mission school in Fenyang, China he taught at under Japanese occupation. On his 10-day China trip he was most impressed by all “the change,” he said. “That’s the difference.” He said while China is still “ostensibly a Communist country, they’re the greatest capitalists in the world.” “They call themselves Communists,” said Michaels, who’s been there, “but everybody winks and nobody really believes that.” The journalists believe China and India will grow as trading partners with each other and with the U.S. as their economies continue to grow. As the world changes at an ever faster rate, Hlavacek said journalism remains “a higher calling.”

For three old men, a lifetime of curiosity has not waned. The world is still their oyster. The news, their metier.

Related Articles

- Journalism veteran Daniel Schorr dies at 93 (cbc.ca)

- ‘Great Soul’: Joseph Lelyveld tells Mahatma Gandhi’s larger-than-life story (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Jesuit Photojournalist Don Doll of Creighton University Documents the Global Human Condition One Person, One Image at a Time (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Address by Cuban Archbishop Jaime Ortega Sounds Hopeful Message that Repression in Cuba is Lifting (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Returning To Society: New community collaboration, research and federal funding fight to hold the costs of criminal recidivism down (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Slaying dragons: Author Richard Dooling’s sharp satire cuts deep and quick

Rick Dooling is yet another immensely talented Nebraska author, one who left here but came back and continues to reside here. His work exhibits great range, but at its core is a sharp wit and a facility for making complex subjects compelling and relatable. His books include White Man’s Grave, which was nominated for the National Book Award, Critical Care, Brain Storm, and his latest, Rapture for the Geeks. He’s also a great guy. This is the first of a few stories I’ve written about him, and it is by the far the most in-depth. It orignally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). Look for more of my Dooling stories to be added to the site. I strongly recommend anything by Rick, who also writes essays on societal-cultural matters for the New York Times and other leading publications.

One of Rick’s books, Critical Care, was made into a feature film by the same title directed by Sidney Lumet. Rick was working with filmmaker Alan Pakula on another big screen adaptation when Pakula was killed in a freak highway accident. Since this article appeared, Rick has collaborated with Stephen King on the television series Kingdom Hospital and adapted King’s short story Dolan’s Cadillac for a feature film by the same name. He’s currently producing-writing a TV pilot.

Slaying dragons: Author Richard Dooling’s sharp satire cuts deep and quick

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Since 1992 Omaha native Richard Dooling has gone from being just another frustrated writer to a literary star, creating a body of work distinguished for its dizzying array of ideas, sharp satirical assault on cherished dogma and sheer mastery of language. In three acclaimed novels — Critical Care, White Man’s Grave, Brain Storm — this writer-provocateur skewers American mores, trends, fads and sacred cows, reserving his most cutting remarks for two fields he once worked in, the law and health care. Easy targets, yes, but Dooling doesn’t settle for tired old broadsides or cloying jokes worn thin. Instead, he uses the hubris and cynicism endemic in the law and medicine as a prism for critically examining issues and raising questions that vex us all.

Dooling, who would make a great teacher, doesn’t presume to provide answers so much as prod us to think about how once basic human yearnings and immutable beliefs are foiled in this world of modern ambiguity and conditional ethics. His work is funny, dramatic, analytical and literary. The attorney-cum-author uses his knack for research to glean telling details that, as in building a good case, lend added weight to his tales.

“I do a lot of research,” he says. “You’ve got to get your facts straight, and then you can do anything you want with them later.”

From 1987 to 1991 he was an associate (specializing in employment

discrimination law) with St. Louis’ largest firm, and before that a respiratory therapist in the intensive care unit at Clarkson Hospital. From working in the legal-medical arenas to holding odd jobs as a cab driver, house painter and psyche ward attendant (“to share some of those patients’ vivid delusional systems is an interesting experience”) to traveling across Europe and Africa, Dooling has a deep well of living to drawn on for his fiction. His stories feature naive white middle-class professionals, all animated extensions of himself, enmeshed in fever-pitch moral dilemmas not patently resolved by the end. Like a lawyer, he argues both sides of an issue in his narratives.

In addition to his novels he has penned a well-received volume of essays (Blue Streak) defending the use of offensive language and op-ed pieces for major publications that poke fun at the latest excesses on the social-cultural front, including a rip-roaring send-up of the President’s imbroglio with Miss Monica. He is currently writing screen adaptations of two of his novels for planned feature films.

In person, Dooling exhibits the same penetrating wit as his prose, although he seems too normal to be the voice behind the scathing black humor he relishes. Married with four children, he is a practicing Catholic. His wife, Kristin, is converting to the faith. The family drives from their southwest Omaha home to worship at a near north side church. Dooling writes from an office in the Indian Hills business district.

If ever a wolf, albeit an intellectual one, in sheep’s clothing it is the 44-year-old author. He has the jowly, post-cherubic face of an altar boy (he was one) flirting with middle-age debauchery. Look closely and his hail fellow-well met facade reveals a gleam in the eye and curl of the lip that betray the bemused, wry gaze of a born agitator who likes pricking the mendacity he sees all around him.

Why satire? “More than anything, I like to make people laugh,” he says. “I don’t want cheap laughs. I want you to discover something new about yourself you didn’t understand before. What interests me as a writer is people on the threshold struggling to organize the flawed parts of themselves into a good person.”

What sets him off on a satirical jag? “Hypocrisy. That’s probably the first thing that provokes me. Somebody saying one thing and doing something else,” he says. “When law and medicine pretend to be helping patients or clients and really it’s raw self-interest, than that’s satirical material. Medicine and law are perfect targets for satire just because they exercise so much control in our lives, and people resent it in a way. You want to bring down the high and mighty and make them just like everybody else. Satire is the great leveler.”

He especially likes deflating any pretensions litigation is a sedate reasoned process for resolving disputes. “It’s combat. It’s a contest and just because it’s essentially bloodless doesn’t make it any less violent. I’m not a big fan of litigation. I think it should be avoided at all costs.”

The looming monster of political correctness is among the trends raising Dooling’s hackles these days. “Because, again, it’s a hypocrisy of a kind,” he says. “The claim is you want diversity in everything, but the central paradox of political correctness is that proponents demand diversity in everything except thought. You have to think the same way as they do or else you’re the enemy. And also the notion you can control people’s thoughts by changing their language just repels me. As a writer, language is the most important thing in your life, and when people start telling you what you should say or not say, it makes you want to say exactly what they don’t want to hear. It makes you want to rebel.”

In a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed he ridiculed attempts at removing certain offensive words from Merriam-Webster dictionaries. One of those petitioning for the excision of hateful language, Kathryn Williams of Flint, Michigan, defended her position by saying, ‘If the word is not there, you can’t use it.” In response, Dooling wrote, “Following…Ms. Williams’s reasoning, we could also remedy the drug problem if we simply removed the words cocaine and heroin from our nation’s dictionaries, for then junkies would be unable to use them. How nice if ancient hatreds could be remedied with a little word surgery, a logos-ectomy to remove offensive words and the hateful thoughts lurking behind them.”

If it weren’t for his dead-on observations, Dooling could easily come off as a smart aleck who is clever with words but short on substance. He is, however, that rarest of commodities: A Swiftian satirist whose barbed, elegantly phrased comments are both funny and thought-provoking. Even when his points are made with dark humor, he avoids sounding contemptuous because he infuses his work with glints of his charming guile and frames his skepticism within a moral context. It makes perfect sense when you learn he grew up in a middle-class Catholic family of nine children and is the product of Jesuit educators. His father was an insurance claims adjustor. His mother, a nurse.