Archive

Hot Movie Takes: PAYNE’S “DOWNSIZING’” – It may be next big thing on the world cinema landscape

Hot Movie Takes:

PAYNE’S “DOWNSIZING’” – It may be next big thing on the world cinema landscape

BY LEO ADAM BIGA, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

April 2017 issue of The Reader

South Omaha Museum: A melting pot magic city gets its own museum

South Omaha’s history is a heady brew of industry, working class families, immigrants, refugees and migrants, tight-knit ethnic neighborhoods, high spirits and fierce pride and though it took more than a century to get one, it finally has its own museum to celebrate all that rich heritage. This is my recent El Perico story about the newly opened South Omaha Museum. It’s a true labor of love for the three men most responsbile for pulling it together: Gary Kastrick, Marcos Mora and Mike Giron. But the heart and soul of it, not to mention most of the collection it displays, comes from Mr. South Omaha, Gary Kastrick, a historian and educator whose dream this museum fufills.

South Omaha Museum: A melting pot magic city gets its own museum

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico (el-perico.com)

Just like the community that forged him, the dreams of South Omaha native and historian Gary Kastrick don’t die easy. The educator developed the Project Omaha teaching museum at South High but when he retired the school didn’t want it anymore.

For years he stored his collection’s thousands of artifacts at his home while seeking a venue in which to display them. An attempt at securing a site fell through but a new one recently surfaced and has given birth to the South Omaha Museum. The nonprofit opened March 15 to much fanfare. Fittingly, it’s located in a building at 2314 M Street he helped his late father clean as a boy. It’s also where he found his first artifact.

Building owner Marcos Mora of the South Omaha Arts Institute wanted Kastrick’s font of history to have a permanent home.

“He’s got this knowledge and we need to share it with everybody,” said Mora. “If we don’t preserve that history now, it’s going to go away.”

A $10,000 City of Omaha historical grant helped but it still took 12-hour days, sweat equity and hustle to open it. Kastrick’s family, friends and former students pitched in. Artist Mike Giron designed the exhibit spaces.

Funding is being sought. Donations are welcome.

The founders are pleased by the strong early response.

“People are overwhelmed,” said Kastrick.

“People come in with expectation and come out with gratitude,” Giron said.

Offers of artifacts are flooding in.

The free admission museum marks the third leg of Kastrick’s three-pronged campaign to spark interest in “a South Omaha renaissance.” Between the museum, historical walking tours he leads and the South Omaha Mural Project he consults, he aims to bring more people to this history-rich district.

“My main goal is to generate traffic.”

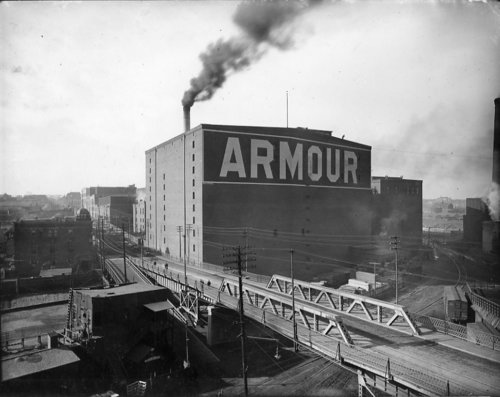

The museum’s opening exhibition, “The Smell of Money,” which runs through April 15, chronicles the stockyards and meatpacking plants that were South O’s lifeblood and largest employer.

Kastrick said, “There was a pride in this industry. The owners did everything first-rate. They put money into it. They made innovations. They created state-of-the-art sheep barns. They did everything right. It’s why Omaha’s stockyards kept growing. It wasn’t expected to be bigger than Chicago but in 1955 it became the world’s largest livestock market.”

He estimates it generated $1.7 million a day.

“It was an extremely wealthy area.”

Ancillary businesses and services sprung up: bars, cafes, hardware stores, feed stores, rendering plants, leather mills, a railway, a newspaper, a telegraph office, grocers, banks, brothels. South O’s red light district The Gully offered every vice. The Miller Hotel was notorious.

Fast growth earned South O the name Magic City.

Rural families taking livestock to market also came for provisions and diversions.

“This was their visit to the big city,” Kastrick said, “so they’d do their shopping, playing, gambling here. It was a treat to come into South Omaha.”

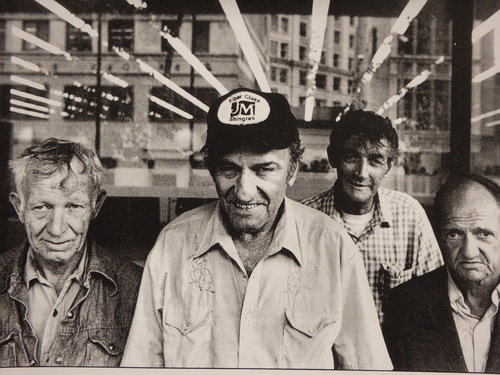

For laborers, the work was rigorous and dangerous.

“There was a comradeship of hard labor. It defined who we were and that definition gave us a color and a flavor other parts of the city don’t have,” Kastrick said. “We’ve always been tougher than those who have it easy.”

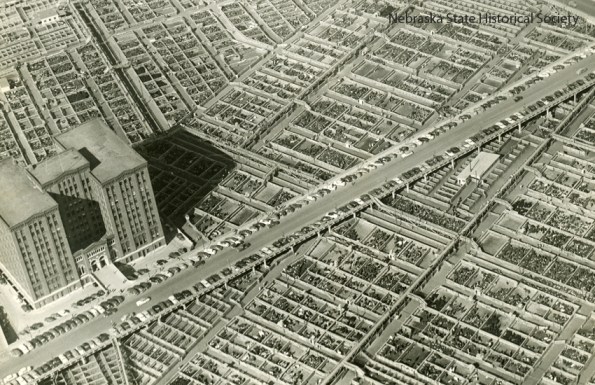

The packing plants drew European immigrants and African-American migrants. Then the antiquated plants grew obsolete and got razed. The loss of jobs and commerce triggered economic decline. The South 24th Street business district turned ghost town. New immigration sparked revival. New development replaced the yards and plants. Only the repurposed Livestock Exchange Building remains. Kastrick’s museum recalls what came before through a scale model layout of the yards, photos, signs, posters, narratives. He has hundreds of hours of interviews to draw on.

“It’s a fascinating history.”

He envisions hosting classes and special events, including a scavenger hunt and trivia night.

Future exhibits will range from bars, brothels and barber shops to Cinco de Mayo to ethnic groups.

Kastrick, Mora and Giron all identify with South O’s melting pot heritage as landing spot and gateway for newcomers.

“There’s that common gene in South Omaha of the immigrant,” said Kastrick, whose grandparents came from Poland. “Wherever people are from, they uprooted themselves from security to come here and start over. It takes a lot of guts. It’s a great place because you run into so many different nationalities. We’re such a compact area – it’s hard not to be with each other.”

Mora, whose grandparents came from Mexico, said

“South Omaha is in our heart.”

Giron, the son of Cuban emigre parents, said, “What I see and identify with here is the underdog. People willing to sacrifice, to work hard, to do what it takes but also knowing how to have a good time. It isn’t an area where everybody takes everything for granted.” Giron said the museum’s “not just about history and facts, it’s about people’s lives,” adding, “It’s like you’re touching or expressing their experience.”

Once a South Omahan, always a South Omaha, said

Mora. “People might have moved out, but they still have that connection. Those roots are still down here. It’s a neighborhood community and extended family network.”

Kastrick said, “We have our own unique identity. It’s something special to be from here. We enjoy who we are. We have kind of a defiant pride because we’ve always been looked down as the working class, the working poor and everything else. We don’t care. We created our own nice little world with everything we need.”

Through changing times and new ethnic arrivals the one constant, he said, “is the South Omaha culture and concept of who we are – tough, good people” who “won’t be stopped.”

For hours, visit http://www.southomahamuseum.org.

//www.youtube.com/embed/HDbrj6HG_Yc?wmode=opaque&enablejsapi=1″,”url”:”https://youtu.be/HDbrj6HG_Yc”,”width”:854,”height”:480,”providerName”:”YouTube”,”thumbnailUrl”:”https://i.ytimg.com/vi/HDbrj6HG_Yc/hqdefault.jpg”,”resolvedBy”:”youtube”}” data-block-type=”32″>

Hot Movie Takes – Gregory Peck

Hot Movie Takes – Gregory Peck

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Gregory Peck was a man and an actor for all seasons. Among his peers, he was cut from the same high-minded cloth as Spencer Tracy and Henry Fonda, only he registered more darkly than the former and more warmly than the latter.

In many ways he was like the male equivalent of the beautiful female stars whose acting chops were obscured by their stunning physical characteristics. Not only was Peck tall, dark and handsome, he possessed a deeply resonant voice that set him apart, sometimes distractingly so, until he learned to master it the way a great singer does. But I really do believe his great matinee idol looks and that unnaturally grave voice got in the way of some viewers, especially critics, appreciating just what a finely tuned actor he really was. Like the best, he could say more with a look or gesture or body movement than most actors can do with a page of dialogue. And when he did speak lines he made them count, imbuing the words with great dramatic conviction, even showing a deftness for irony and comedy, though always playing it straight, of course.

I thought one of the few missteps in his distinguished career was playing the Nazi Doctor of Death in “The Boys from Brazil.” The grand guignol pitch of the movie is a bit much for me at times and I consider his and Laurence Oliver’s performances as more spectacle than thoughtful interpretation. I do admire though that Peck really went for broke with his characterization, even though he was better doing understated roles (“Moby Dick” being the exception). I’m afraid the material was beyond director Franklin Schaffner, a very good filmmaker who didn’t serve the darkly sardonic tone as well as someone like Stanley Kubrick or John Huston would have.

Peck learned his craft on the stage and became an immediate star after his first couple films. He could be a bit stiff at times, especially in his early screen work, but he was remarkably real and human across the best of his performances from the 1940s through the 1990s. I have always been perplexed by complaints that he was miscast as Ahab in “Moby Dick,” what I consider to be a film masterpiece. For my tastes at least his work in it does not detract but rather adds to the richness of that full-bodied interpretation of the Melville classic.

My two favorite Peck performances are in “Roman Holiday” and, yes, “To Kill a Mockingbird.” I greatly admire his work, too, in “The Stalking Moon” and have come to regard his portrayal in “The Big Country” as the linchpin for that very fine film that I value more now than I did before. He also gave strong performances in “The Yearling,” “Yellow Sky,” “The Gunfighter,” “12 O’Clock High,” “The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit,” “Pork Chop Hill,” “On the Beach,” “Cape Fear,” “The Guns of Navarone,” “How the West was Won,” “Captain Newman M.D.” “Mirage” and “Arabesque.” I also loved his work in two made for television movies: “The Scarlet and the Black” and “The Portrait.”

He came to Hollywood in the last ebb of the old contract studio system and within a decade joined such contemporaries as Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster in producing some of his own work.

Peck’s peak as a star was from the mid-1940s through the late 1960s, which was about the norm for A-list actors of his generation. Certainly, he packed a lot in to those halcyon years, working alongside great actors and directors and interpreting the work of great writers. He starred in a dozen or more classic films and in the case of “To Kill a Mockingbird” one of the most respected and beloved films of all time. It will endure for as long as there is cinema. As pitch perfect as that film is in every way, I personally think “Roman Holiday” is a better film, it just doesn’t cover the same potent ground – i.e. race – as the other does, although its human values are every bit as moving and profound.

Because of Peck’s looks, stature and voice, he often played bigger-than-life characters. Because of his innate goodness he often gravitated to roles and/or infused his parts with qualities of basic human dignity that were true to his own nature. He was very good in those parts in which he played virtuous men because he had real recesses of virtue to draw on. His Atticus Finch is a case of the right actor in the right role at the right time. Finch is an extraordinary ordinary man. I like Peck best, however, in “Roman Holiday,” where he really is just an ordinary guy. He’s a journeyman reporter who can’t even get to work on time and is in hock to his boss. Down on his luck and in need of a break, a golden opportunity arises for a world-wide exclusive in the form of a runaway princess he’s happened upon. Lying through his teeth, he sets out to do a less than honorable thing for the sake of the story and the big money it will bring. It’s pure exploitation on his part but by the end he’s fallen for the girl and her plight and he can’t go through with his plan to expose her unauthorized spree in Rome. I wish he had done more parts like this.

Here is a link to an excellent and intimate documentary about Peck:

- [VIDEO]

A Conversation with Gregory Peck 6/11 – YouTube

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PPjDwN9KY0g

Just last night on YouTube I finally saw an old Western of his, “The Bravados,” I’d been meaning to watch for years. It’s directed by Henry King, with whom he worked a lot (“The Gunfighter,” Twelve O’Clock High,” “Beloved Indidel”), and while it’s neither a great film nor a great Western it is a very good if exasperatingly uneven film. That criticism even extends to Peck’s work in it. He’s a taciturn man hell-bent on revenge but I think he overplays the grimness. I don’t know if some of the casting miscues were because King chose unwisely or if he got stuck with certain actors he didn’t want, but the two main women’s parts are weakly written and performed. Visually, it’s one of the most distinctive looking Westerns ever made. Peck also had fruitful collaborations with William Wyler (“Roman Holiday” and “The Big Country”), Robert Mulligan (“To Kill a Mockingbird” and “The Stalking Moon”) and J.L Thompson (“Cape Fear” and “The Guns of Navarone).

Two Peck pictures I’ve never seen beyond a few minutes of but that I’m eager to watch in their entirety are “Behold a Pale Horse” and “I Walk the Line.”

Peck’s work will endure because he strove to tell the truth in whatever guise he played. His investment in and expression of real, present, in-the-moment emotions and thoughts give life to his characterizations and the stories surrounding them so that they remain forever vital and impactful.

For a pretty comprehensive list of his screen credits, visit:

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000060

Hot Movie Takes – ‘Taxi Driver’

Hot Movie Takes – “Taxi Driver”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

It’s hard to imagine general American moviegoing audiences being prepared for “Taxi Driver” when it hit theaters in 1976. I mean, here was ostensibly a film noir that eschewed standard conventions for a dark fever dream of one man’s mounting paranoia and revulsion in the urban wasteland of New York City.

The character of Travis Bickle didn’t have any direct cinema antecedents but he did emerge from a long line of disturbed screen figures going back to Peter Lorre in “M,” James Cagney as Cody Jarrett in “White Heat,” Richard Basehart as Roy Martin in “He Walked By Nigh,” Robert Walker as Bruno Antony in “Strangers on a Train” and Robert Mitchum as Harry Powell in “Night of the Hunter.”

There are even some hints of Robert Ryan as Montgomery in “Crossfire” and as Earle Slater in “Odds Against Tomorrow” and of Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates in “Psycho” and as Dennis Pitt in “Pretty Poison.”

Bickle also anticiated many screen misfits to follow, including some of the whack jobs in Coen Brothers and Quentin Tarantino films.

As a disenfranchised loner who sees the world around him as a venal place, Bickle obsessively reinvents himself into a self-made avenging angel ridding the streets of scum. His response to the violent, lurid subculture of sex for sale is an explosive bloodletting that is, in his mind, a purification. In the end, after carrying out his self-appointed cleansing mission, are we to believe he is mad or merely misguided? Is he a product or symptom of urban isolation and decay?

Paul Schrader’s brilliant script, Martin Scorsese’s inspired direction and Robert De Niro’s indelible performance took what appeared to be Grade B grindhouse thematic material and elevated it into the realm of art-house mastery. They did this by making the story and character an intense psycho-social study of disturbance. Bickle is not some nut case aberration. Rather he is one of us, which is to say he is an Everyman cut off from any real connections around him. The way he’s wired and the way he views the world make him a ticking time bomb. It’s only a matter of time before he’s set off and goes from talking and fantasizing about doing extreme things to actually enacting them. He lives in his head and his head is filled with disgusting images and thoughts that occupy him as he drives his cab through the streets of what he considers to be a modern-day Gomorrah. He fixates on certain things and persons and he won’t be moved from his convictions, which may or may not be the result of psychosis or sociopathic tendencies.

Schrader’s script and Scorsese’s direction, greatly aided by Michael Chapman’s photography and Bernard Herrmann’s musical score, find wildly expressive ways to indicate Bickle’s conflicted state of mind. Atmospheric lighting captures a surreal landscape of garish neon signs, steam rising from the streets and back street porno theaters, strip clubs and whorehouses. He grows to hate the pimps and pushers, the johns and addicts littering the city. When he tries to intersect with normality, it’s a complete disaster. Languid, dream-like music underscores the moral turpitude bringing Bickle down. Emotionally-charged, driving music accompanies Bickle’s trance-like rituals and final hypnotic outburst that is simultaneously savage and serene.

Travis Bickle is a troubling symbol who straddles the legal, moral and psychological line of impulse and premeditation. Does he know what he’s doing? Is he responsible for his actions? Or is he insane?

De Niro’s transformation from mild-mannered cabbie to scary vigil ante, complete with the famous “Are you talking to me?” break with reality, is where the real power of the film resides. He somehow makes his character believably frightening, revolting, pathetic and sympathetic all at the same time. To me, it will always stand as one of his two or three greatest performances because he completely inhabits this disturbed character without ever going over the top or resorting to cliches. He creates a true original in the annals of cinema that belongs to him and him alone.

There are some fine supporting performances in the film by Peter Boyle, Cybill Shepherd. Albert Brooks, Harvey Keitel and, of course, Jodi Foster as the adolescent prostitute Bickle anoints himself as protector and rescuer of. They and De Niro share some strong moments together. But it’s when De Niro’s character is alone and brooding, stalking and staring, that he most comes alive as a terrible reflection of our dark side run amok.

You can read “Taxi Driver” anyway you want: as exploration or examination, as cautionary tale, as prescient forecast, as potboiler crime pic. But however you read it, it is a vital, compelling and singular work of its time that endures because no matter how bizarre the story and stylized the effects, it’s always grounded in the truth of its single-minded protagonist. The film never stops giving us his point of view, even at the height of his mania.

Like a lot of the best ’70s American movies, this one doesn’t leave you feeling good but you know you’ve had an experience that’s challenged your mind and emotions and perhaps even moved you to some new understanding about the human condition. That’s what the best movies are capable of doing and this one certainly hits the mark.

Hot Movie Takes – “A Bronx Tale”

Hot Movie Takes – “A Bronx Tale”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

The movie that Robert De Niro made his directorial debut, “A Bronx Tale” (1993), is a highly personal coming-of-age story for both him and its star and writer, Chazz Palminteri. The two men grew up in the era and around the culture the story depicts, which is 1950s Italian-America. Coming-of-age stories don’t usually have the grit this one does, nor do they have the poetic realism this one finds in the clash between two intersecting worlds with radically different values: the legitimate world of working-class people represented by bus driver Lorenzo and the underworld exemplified by mobster Sonny. Caught in the middle of this tug of war is Calogero, the only son of Lorenzo and the apple of Sonny’s eye. As a child Calogero witnesses a crime committed by Sonny that the boy never reveals. Calogero’s silence earns the respect of Sonny, who unwittingly recruits him into the inner sanctum of his Mafia lifestyle as devoted errand boy and worshipful hanger-on.

Though this grooming into that lifestyle hasn’t resulted in Calogero breaking the law yet, Lorenzo sees that it’s only a matter of time. He strongly disapproves of his son being around that criminal element and he fears he’s losing Calogero to the lure of fast, easy money, expensive cars and an above-the-law attitude. He especially resents Sonny practically adopting his son as a junior Wiseguy, although that’s not what Sonny wants for Calogero at all. Indeed, he tells the boy this is not for him. But Lorenzo doesn’t know that. When Lorenzo finally confronts Sonny, he takes a beating for his trouble but the two men have a clear understanding. Lorenzo will never allow his boy to be seduced into that world. Sonny makes it clear he won’t tolerate being threatened again, Both men accept that crossing the line will mean one of their deaths. Meanwhile, Calogero is torn between his loyalties to the two men he loves and must choose between.

Eventually the choice is made for him. It starts when the teen mobster wannabes he also hangs with go too far with their racist attacks against black youths navigating their streets. Calogero has eyes for a black girl he’s met whose brother is savagely beat by his friends. He knows that if his feelings for this girl, Jane, are found out it will brand him as a traitor to his race. In his xenophobic neighborhood, especially among his peers, an interracial romance is taboo and therefore unthinkable, at least in public.

Sonny warns Calogero away from his impulsive buddies and the stubborn kid only narrowly escapes their ill-fated but inevitable demise. Calogero balances the hard life lessons Sonny and his father impart and he comes to realize the enticing gangster world isn’t all that it appeared to be to his once naive eyes.

By the end, Calogero’s learned to see things more clearly, including the high price that The Life brings, and he no longer feels he has to hide his dating Jane.

De Niro and Palminteri know from first-hand experience something of the streets and pressures and culture clashes the film portrays.

The film is an adaptation of a one-man play Palminteri wrote and starred in. It was such a sensation on the stage, first in L.A. and then in New York, that a bidding war for its screen rights broke out. In the end he adapted the play to the screen for De Niro to direct. The story is taken directly from Palminteri’s own life. He was that boy, the son of a bus driver, who fell under the influence of a local made-guy named Sonny.

Palminteri explained it all in an interview:

“I remembered this killing I saw when I was 9 years old. I was sitting on my stoop and this man killed a man right in front of me.”

The killer’s name was Sonny, a mobster who controlled much of the Bronx neighborhood where Palminteri grew up. The police came, but the young boy kept quiet. Soon after Sonny began taking him under his wing.

“He liked me almost as a son, and he wanted me to do good and he wanted me to go to college. But just by being around and who he was, he was a Wiseguy, he was a boss, I was being influenced by all these guys and their cars and their women.”

Just as in the movie, Palminteri’s father told his son the real hero was the working man, not the gangsters.

“He wrote on a little card ‘The saddest thing in life is wasted talent.’ He used to say to me ‘Don’t waste your talent. Make something out of yourself.’ And he put it in my room and I used to see that all the time. You know, Sonny eventually got killed. And I realized that my father was right. So I thought about this whole thing and I said, ‘Gee, you know what? This would make a great story to write what I learned from both men, and how I became a man.'”

De Niro grew up very differently as the son of accomplished artists and creatives but his life skirted some rougher aspects and he certainly knows well the territory and hazards of interracial relationships.

“A Bronx Tale” is now a musical and in an interview Palminteri said of the story’s enduring appeal across different media and genres and cultures, “I’ve done 60 movies, and people just love A Bronx Tale. It’s strange. Not just here in America, but everywhere—Japan, Europe. I don’t understand it. It touched a chord with a lot of people. I guess what I wrote was archetypes. It’s about so many things, about being the best of who you are. It’s about choices. And the story has just connected to people for so long.”

De Niro explained it this way: “It’s kind of a morality story. It’s got a simple story in a way. It has that kind of timelessness to it.”

As a director, De Niro shows a sure hand with his actors and keeps the story moving along. Whatever he gleaned from Francis Fork Coppola, Sergio Leone and Martin Scorsese in acting in their mob-themed movies, he uses to great subtle effect here as he doesn’t make his own take on that world derivative or half-hearted, but rather orginal and full-blooded.

“A Bronx Tale” also stands as one of De Niro’s best performances. As brilliant as he is in showier roles, I like him best playing average Joes like this. Palminteri has never been better than he is here. Francis Capra as the 9 year-old Calogero and Lillo Brancato as the 17-year-old Calogero are both very good. Brancato infamously ran afoul of the law in real life and served a long prison term. Taral Hicks is dreamy as Jane and it’s shame we haven’t seen more of her over the years. Joe Pesci has a small but vital role at the end that he handles extremely well in adding a final grace note to the story.

I can definitely see how “A Bronx Tale” could work as a musical and I hope a touring production of it makes it here one day or else a local theater company puts on its own production of it.

Hot Movie Takes – ‘The Bronx Bull’

Hot Movie Takes – “The Bronx Bull”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

1980’s “Raging Bull” is a great film that captures the demons of boxing legend Jake LaMotta through stylized filmmaking expressing the state of this complex figure’s tortured soul. Until I found it on Netflix the other night I didn’t know that a new filmic interpretation of LaMotta came out in 2016 – “The Bronx Bull.” While it’s not on the same level as the Martin Scorsese-Robert De Niro classic, it’s a good film that takes a less arty and more traditional look at those demons that made LaMotta such a ferocious fighter and haunted man.

Veteran character actor William Forsythe plays the older adult LaMotta and delivers a stellar performance that in many ways has as much or more depth as De Niro’s famous turn as LaMotta. Don’t get me wrong, De Niro’s work in “Raging Bull” is one of cinema’s great acting tour de forces for its compelling physical and emotional dimensions. but Forsythe gives perhaps a more subtle and reality grounded performance. In this telling of the LaMotta tale, the violence of his character is rooted in a Dickensian growing up that saw him abused and exploited by his own father. We are asked to accept that LaMotta was the way he was both inside and outside the ring because he had basic issues with rejection and abandonment. And he can’t forgive himself for apparently killing a fellow youth in a back alley fistfight for pay. Reality might be more complex than that, but these are as plausible explanations as any for what made LaMotta such a beast and Forsythe draws from that well of hurt to create a very believable flesh and blood man desperate for love and forgiveness.

There’s a lot of really good actors in “The Bronx Bull” and while the writing and directing by Martin Guigui doesn’t always do them justice, it’s great to see all this talent working together: Paul Sorvino, Joe Mantegna, Tom Sizemore, Ray Wise, Robert Davi, Natasja Henstridge, Penelope Ann Miller, Cloris Leachman, Bruce Davison, Harry Hamlin and James Russo.

Mojean Aria is just okay as the very young LaMotta. I think a more dynamic actor would have helped. Then again, the young LaMotta is not given many moments to explain himself or his world. That’s left to his cruel father, well-played by Sorvino. But this is Forsythe’s film and he’s more than up to the task of carrying it. Whenever he’s on screen, he fully inhabits LaMotta as a force of nature to be reckoned with. Forsythe very smartly stays away from a characterization that’s anything like what De Niro did in “Raging Bull.” Forsythe finds his own way into LaMotta and pulls out some very human, very tender things to go along with the legendary rage. The trouble with the film though is that writer-director Guigui sometimes apes “Raging Bull’s” style, either consciously or unconsciously, especially in some of the scenes inside the ring and in the way he handles the Mob characters, and since he’s no Martin Scorsese, those scenes don’t measure up.

Any story about professional boxing set in the 1940s and 1950s, as this one is, must deal with the Mob, which controlled the upper levels of prizefighting in this country in that period. This story doesn’t so much go into what Mob influence looked like during LaMotta’s career as it does what it looked like after he hung up the gloves. That said, the movie begins with a retired LaMotta testifying before a U.S. Senate sub-committee on how the Mafia ordered him to throw a fight and how he did what he had to do to get the title shot he craved. The story then picks up on how what LaMotta always feared – the Mob getting their hooks in and not letting go – catches up with him years later.

Tom Sizemore is pretty good as one Wiseguy but Mike Starr wears out his welcome playing the same kind of bungling Wiseguy he’s played in one too many pictures. In a very brief but telling scene Robert Davi is superb as a character who appears almost as a ghost to LaMotta. Natasja Henstridge is every bit as good as Sally as Cathy Moriarty was as Vickie in “Raging Bull,” and that’s saying something. After a strong opening, Penelope Ann Miller’s character of Debbie is mishandled. Debbie and LaMotta make an unlikely but interesting pairing and then she’s almost dismissed as irrelevant when she begins to tire of his antics and he’s once again threatened by rejection and abandonment. As Debbie’s mother, Cloris Leachman is fine but she’s basically reduced to being a cliche.

Joe Mantegna is a good actor and his character of Rick is compelling at the start but by the end he seems to be there more as a plot-point device than as a real figure and by then he’s frankly irritating.

According to this telling of the LaMotta story, the fighter and those close to him paid a high price for his deep reservoir of insecurity but through all the hell he put himself and others through he did eventually find peace and atonement. In the end, I wanted it and bought it, too.

This is not a great film and not even a great boxing film but you may well find it worth your time. It’s title got me thinking about a much better film with the name Bronx in it – “A Bronx Tale,” the first movie Robert De Niro directed and the project that made its writer and star, Chazz Palminteri, a star. It’s the subject of my next Hot Movie Take.

The Bronx Bull Official Trailer (HD)

Hot Movie Takes Monday – ‘Mississippi Masala’

Hot Movie Takes Monday – “Mississippi Masala”

©By Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Over the weekend I revisited one of my favorite films from the early 1990s – Mira Nair’s “Mississippi Masala.” I remembered it as one of the richest cross cultural dramas of that or any era and upon re-watching it on YouTube my impressions from then have been confirmed.

The story concerns an Indian family exiled from Uganda during Idi Amin’s reign of terror. They were forced to leave everything they owned and loved in terms of home, The patriarch of the family was born and raised in Uganda and lived there his entire life, building a life and career that made him feel at one with a nation his people had been brought to by the British to build railways. Though his ancestral roots are not of that continent, he identifies as African first, Indian second. The family ends up in Mississippi, owning and operating a motel and a liquor store. The patriarch, Jay, and his wife are the parents of an only child, Meena, who was a little girl when her left Uganda as refugees. When we meet her again she is a lovely, single 24 year old woman and still devoted daughter but strains under her parents’ overprotectiveness and their insisting she adhere to strict traditions concerning matrimonial matches and such. Those traditions aren’t such a good fit in America.

Also weighing heavily on Meena is the burden her father carries from being torn from his homeland. He can’t let that severing go. For years he’s petitioned the Ugandan government for a hearing to plead his case for his property and assets to be restored. He is a haunted figure. Part of what haunts him is the way he rebuked his black Ugandan friend from childhood, Okelo, when Amin’s military police rounded up foreigners for arrest, torture, deportation. Okelo is a devoted family friend who is like a brother to Jay and a grandfather to Meena. When Jay is arrested for making anti-Amiin remarks in a broadcast TV interview, Okelo bribes officials to free him. He tries to convince Jay that there is no future for him in Uganda anymore. Okelo tells him, “Africa is for black Africans.” He says it not out of malice but love. Jay is deeply hurt. He can’t accept this new reality but he realizes he and his family have no choice but to flee if they are to remain alive. Jay leaves without saying goodbye to Okelo. Meena sees and feels her father’s bitter anger and her beloved Okelo’s broken heart.

Grown-up Meena, played by Sarita Choudhury, lives with her parents in a diverse Mississippi town where they are the minority. A meet-cute accident brings together Meena and a young African-American man, Demetrius, played by Denzel Washington. He’s a devoted son who owns his own carpet cleaning business. He’s immediately attracted to Meena but at first he pays attention to her to get back at his ex, who’s in town and intent on belittling him. But things progress to the point where he and Meena spark the start of a real relationship. She meets his family and is embraced by them. Then the prejudice her extended family and community feels for blacks gets in the way and things get messy. As it always is with race, there are misunderstandings, assumptions and fears that cause rifts. Meena’s father is reminded of his own close-mindedness – that Indians in Africa wouldn’t allow their children to marry blacks. Demetrius and his circle must confront their own racist thinking.

Everyone in this film has their own wounds and stones of racism to deal with. No one is immune. No one gets off the hook. We’re all complicit. We all have something to learn from each other. It’s what we do with race that matters.

The theme of being strangers in homelands runs rife through the film. Just as African-Americans in Mississippi were enslaved and disenfranchised and often cut off from their African heritage, Indian exiles like Meena’s family are strangers wherever they go and distant from their own ancestral homeland of India.

Meena finally asserts her independence and her father finally gets his hearing. His bittersweet return to Uganda fills him with regret and longing, ironically enough, for America, which he realizes has indeed become his new home. The simple, sublime ending finds Jay in a street market where residents of the new Uganda revel in music and dance that are a mix of African and Western influences. As he watches the joy of a people no longer living in oppression, a black infant held by a man touches his face and Jay ends up holding the boy close to him, feeling the warmth and tenderness of unconditional love and trust.

There’s a great montage sequence near the end where the diverse currents of India, the American Deep South and Africa converge in images that some hot harmonica blues cover. By the end, the movie seems to tell us that home is a matter of the heart and identity is a state of mind and none of it need keep us apart if we don’t let it.

I saw the film when it first came out and though it spoke to me I was still a decade away from being in my first interracial relationship. I was already very curious about the possibilities of such a relationship and I was also acutely attuned to racial stereotypes and prejudices because of where and how I grew up. Seeing the film again today, as a 15 year veteran of mixed race couplings and a 21 year veteran of writing about race, it has even more resonance than before. And having visited Uganda in 2015 I now have a whole new personal connection to the film because of having been to that place so integral to the story.

This was the second movie by Nair I saw. The first, “Salaam Bombay,” was a hit on the festival circuit and that’s where I saw it – an outdoor screening at the Telluride Film Festival. Years later I saw another of her features, “Monsoon Wedding.” I still need to catch up with two of her most acclaimed later films, “The Perez Family” and “The Namesake.”

Watch the “Mississippi Masala” trailer at:

Hot Movie Takes Saturday – FIVE CAME BACK

Hot Movie Takes Saturday – FIVE CAME BACK

©by Leo Adam Biga, Author of “Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film”

Five Legendary Filmmakers went to war:

John Ford

William Wyler

Frank Capra

George Stevens

John Huston

Five Contemporary Filmmakers take their measure:

Paul Greengrass

Steven Spielberg

Guillermo del Toro

Lawrence Kasdan

Francis Ford Coppola

When the United States entered World War II these five great Hollywood filmmakers were asked by the government to apply their cinema tools to aid the war effort. They put their lucrative careers on hold to make very different documentaries covering various aspects and theaters of the war. They were all masters of the moving picture medium before their experiences in uniform capturing the war for home-front audiences, but arguably they all came out of this service even better, and certainly more mature, filmmakers than before. Their understanding of the world and of human nature grew as they encountered the best and worst angels of mankind on display.

The story of their individual odysseys making these U.S, government films is told in a new documentary series, “Five Came Back,” now showing on Netflix. The series is adapted from a book by the same title authored by Mark Harris. The documentary is structured so that five contemporary filmmakers tell the stories of the legendary filmmakers’ war work. The five contemporary filmmakers are all great admirers of their subjects. Paul Greengrass kneels at the altar of John Ford; Steven Spielberg expresses his awe of William Wyler; Guillermo del Toro rhapsodizes on Frank Capra; Lawrence Kasdan gushes about George Stevens; and Francis Ford Coppola shares his man crush on John Huston. More than admiration though, the filmmaker narrators educate us so that we can have more context for these late filmmakers and appreciate more fully where they came from, what informed their work and why they were such important artists and storytellers.

The Mission Begins

As World War II begins, five of Hollywood’s top directors leave success and homes behind to join the armed forces and make films for the war effort.

Combat Zones

Now in active service, each director learns his cinematic vision isn’t always attainable within government bureaucracy and the variables of war.

The Price of Victory

At the war’s end, the five come back to Hollywood to re-establish their careers, but what they’ve seen will haunt and change them forever.

Ford was a patriot first and foremost and his “The Battle of Midway” doc fit right into his work portraying the American experience. For Wyler, a European Jew, the Nazi menace was all too personal for his family and he was eager to do his part with propaganda. For Capra, an Italian emigre, the Axis threat was another example of powerful forces repressing the liberty of people. The “Why He Fight” series he produced and directed gave him a forum to sound the alarm. A searcher yearning to break free from the constraints of light entertainment, Stevens used the searing things he documented during the war, including the liberation of death camps, as his evolution into becoming a dramatist. Huston made perhaps the most artful of the documentaries. His “Let There Be Light” captured in stark terms the debilitating effects of PTSD or what was called shell shock then. His “Report from the Aleutians” portrays the harsh conditions and isolation of the troops stationed in Arctic. And his “The Battle of San Pietro” is a visceral, cinema verite masterpiece of ground war.

The most cantankerous of the bunch, John Ford, was a conservative who held dear his dark Irish moods and anti-authoritarian sentiments. Yet, he also loved anything to do with the military and rather fancied being an officer. He could be a real SOB on his sets and famously picked on certain cast and crew members to receive the brunt of his withering sarcasm and pure cussedness. His greatest star John Wayne was not immune from this mean-spiritedness and even got the brunt of it, in part because Wayne didn’t serve during the war when Ford and many of his screen peers did.

Decades before he was enlisted to make films during the Second World War, he made a film, “Four Sons,” about the First World War, in which he did not serve.

Following his WWII stint, Ford made several great films, one of which, “They Were Expendable,” stands as one of the best war films ever made. His deepest, richest Westerns also followed in this post-war era, including “Rio Grande,” “Fort Apache,” “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon,” “The Searchers,” “The Horse Soldiers” and “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.” Another war film he made in this period, “The Wings of Eagles,” is another powerful work singular for its focus on a real-life character (played by Wayne) who endures great sacrifices and disappointments to serve his country in war.

Even before the war Ford injected dark stirrings of world events in “The Long Voyage Home.”

William Wyler had already established himself as a great interpreter of literature and stage works prior to the war. His subjects were steeped in high drama. Before the U.S. went to war but was already aiding our ally Great Britain, he made an important film about the conflict, “Mrs. Miniver,” that brought the high stakes involved down to a very intimate level. The drama portrays the war’s effects on one British family in quite personal terms. After WWII, Wyler took this same closely observed human approach to his masterpiece, “The Best Years of Our Lives,” which makes its focus the hard adjustment that returning servicemen faced in resuming civilian life after having seen combat. This same humanism informs Wyler’s subsequent films, including “The Heiress,” “Roman Holiday,” “Carrie,” “The Big Country” and “Ben-Hur.”

Wyler, famous for his many takes and inability to articulate what he wanted (he knew it when he saw it), was revered for extracting great performances. He didn’t much work with Method actors and I think some of his later films would have benefited from the likes of Brando and Dean and all the rest. One of the few times he did work with a Method player resulted in a great supporting performance in a great film – Montgomery Clift in “The Heiress.” Indeed, it’s Clift we remember more than the stars, Olivia de Havilland and Ralph Richardson.

Frank Capra was the great populist director of the Five Who Came Back and while he became most famous for making what are now called dramedies. he took a darker path entering and exiting WWII, first with “Meet John Doe” in 1941 and then with “It’s a Wonderful Life” in 1946 and “State of the Union” in 1948. While serious satire was a big part of his work before these, Capra’s bite was even sharper and his cautionary tales of personal and societal corruption even bleaker than before. Then he seemed to lose his touch with the times in his final handful of films. But for sheer entertainment and impact, his best works rank with anyone’s and for my tastes anyway those three feature films from ’41 through ’48 are unmatched for social-emotional import.

Before the war George Stevens made his name directing romantic and screwball comedies, even an Astaire-Rogers musical, and he came out of the war a socially conscious driven filmmaker. His great post-war films all tackle universal human desires and big ideas: “A Place in the Sun,” “Shane,” “Giant,” “The Diary of Anne Frank.” For my tastes anyway his films mostly lack the really nuanced writing and acting of his Five Came Back peers, and that’s why I don’t see him in the same category as the others. In my opinion Stevens was a very good but not great director. He reminds me a lot of Robert Wise in that way.

That brings us to John Huston. He was the youngest and most unheralded of the five directors who went off to war. After years of being a top screenwriter, he had only just started directing before the U.S. joined the conflict. His one big critical and commercial success before he made his war-effort documentaries was “The Maltese Falcon.” But in my opinion he ended up being the best of the Five Who Came Back directors. Let this list of films he made from the conclusion of WWII through his death sink in to get a grasp of just what a significant body of work he produced:

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

The Asphalt Jungle

Key Largo

The Red Badge of Courage

Heaven Knows Mr. Allison

Beat the Devil

Moby Dick

The Unforgiven

The Misfits

Freud

The List of Adrian Messenger

The Night of the Iguana

Reflections in a Golden Eye

Fat City

The Man Who Would Be King

Wiseblood

Under the Volcano

Prizzi’s Honor

The Dead

That list includes two war films, “The Red Badge of Courage” and “Heaven Knows Mr. Allison,” that are intensely personal perspectives on the struggle to survive when danger and death are all around you. Many of his other films are dark, sarcastic ruminations on how human frailties and the fates sabotage our desires, schemes and quests.

I believe Huston made the most intelligent, literate and best-acted films of the five directors who went to war. At least in terms of their post-war films. The others may have made films with more feeling, but not with more insight. Huston also took more risks than they did both in terms of subject matter and techniques. Since the other directors’ careers started a full decade or more before his, they only had a couple decades left of work in them while Huston went on making really good films through the 1970s and ’80s.

Clearly, all five directors were changed by what they saw and did during the war and their work reflected it. We are the ultimate beneficiaries of what they put themselves on the line for because those experiences led them to inject their post-war work with greater truth and fidelity about the world we live in. And that’s really all we can ask for from any filmmaker.