Archive

Designing Woman: Connie Spellman Helps Shape a New Omaha Through Omaha By Design

Designing Woman: Connie Spellman Helps Shape a New Omaha Through Omaha By Design

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Connie Spellman’s imprint on Omaha grows every day. As director of Omaha By Design, the Omaha Community Foundation (OCF) initiative attempting to do nothing less than change the face of the city, she has her hands all over the metro.

When she joined what was then called Lively Omaha in 2001 Spellman was already a passionate advocate of the city from her prior Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce career. Her Chamber experience gave her a keen understanding of how the private and public sectors work in Omaha.

“I’d had a wonderful career at the Chamber and couldn’t imagine having another position that was as fun and meaningful and rewarding as that,” she said. “I’d had a year of retirement and other opportunities that sounded like jobs. And I wasn’t ready. And this one came along…”

“This one” refers to her Omaha By Design position, which is that of facilitator and visionary. She brings diverse people together to brainstorm ideas, design guidelines, write zoning-construction codes and develop projects that embody aesthetically pleasing, eco-friendly, cohesive urban planning. The aim is to improve Omaha’s appearance and the way people interact with their lived environment. She works closely with the city, neighborhood groups and the private sector to do that.

She took the newly formed post, she said, because “I love Omaha. I enjoy challenges. I thought the timing was right because sometimes timing is everything. The city was really ready for looking beyond its historic attributes to look at its environment in a bigger picture.”

When then-OCF chairman Del Weber recruited her to the job Omaha was in the throes of an identity crisis. The city embodied stolid Midwestern values predicated on friendliness and work ethic but could claim few signature public spaces. The adverse effects of suburban sprawl, inner city neglect and scattershot development were everywhere.

“We’re a great city of individual projects that were developed without consideration of how they’re connected to each other,” she said.

Studies confirmed Omaha lacked a positive image and that residents, especially younger ones, found the city dull and drab. Spellman said a Gallup survey found only a small percentage of Omahans thought the city attractive.

“I was appalled,” she said. “I thought, What a shame. It means we really haven’t paid attention to it and we didn’t have much pride in it. How can we be competitive and expect our kids to stay here if we think our city is unattractive?”

Foundation supporters, who include some of Omaha’s movers and shakers, hired Minnesota consultant Ronnie Brooks to assess the city’s Wow! factor. He suggested Omaha needed to be more” connected, smart, significant, sparkling and fun.” The foundation created Lively Omaha in 2001 to do just that, but it floundered trying to put into action what sounded so abstract or, as Spellman put it, “nebulous.” Meanwhile, Omaha’s doldrums and inferiority complex festered.

Still, she said, those words by Brooks “in one way or another kept coming back to everything we do — to how we look and how we act…”

Then something happened that brought the organization’s mission into focus. When the downtown-riverfront construction boom began — one that ultimately resulted in $2 billion in new development — Lively Omaha saw the potential for an Omaha makeover on a citywide scale.

The Omaha World-Herald’s Freedom Park, Union Pacific’s and First National Bank’s new headquarters, the Holland Performing Arts Center, the Qwest Center, the Gallup campus, the National Parks Services building, Creighton University’s soccer stadium and new dorms and a beautified Abbott Drive created a dynamic new downtown-riverfront corridor. What had been unsightly was now a picture postcard destination district. These projects signaled a major turnaround in not only Omaha’s appearance but in the way Omahans felt about their city.

More energizing projects followed, including the Saddle Creek Records build-out with Slowdown and Film Streams and nearby hotels in NoDo. More is on the drawing boards, notably the $140 million downtown baseball stadium slated to open in 2011.

The cityscape is changing far beyond downtown as well. Improvements around 24th and Lake Streets and along the South 24th Street business strip, the transformation of the former stockyards site and the mixed use developments going up on the Mutual of Omaha and Ak-Sar-Ben campuses are examples of the New Omaha.

Spellman said such projects are changing residents’ and visitors’ appreciation for a town that’s long battled an image problem.

“That translates into so many things,” she said. “You can’t help but feel good when you’re downtown today or driving into our city. There’s an energy here that’s coming back because people have a vision that is being realized. And I think that attitude can accelerate the implementation of the vision because once you get a taste of it you want more, faster.”

She’s certain if a survey were done today sampling the city’s “It” quotient there would be a very different result than a decade ago.

“I think people would feel better about their community. I think there is a contagion that is going on because of the continued development that’s happening downtown and the revitalization of suburban areas like Village Pointe.

“I see it everywhere — in what people do with their own homes and what they do with their businesses and what they want to see happen with development in general and how they view their city.”

It’s ironic the woman who has Omaha reinventing itself through sustainable, livable design strategies had to immerse herself in the subject when she got the job.

“I knew nothing about urban design or public space,” she said from her office in the historic Blackstone building. She’s about a stone’s throw away from Mutual of Omaha’s Midtown Crossing at Turner Park project under construction — an example of the kind of transformation she advocates. “I have always had an appreciation of art and architecture but I never really put them in the context of public spaces or design. And so the first thing I had to do was educate myself.”

That posed no problem for this former teacher who’s devoted much of her public service to education. She read, she sounded out experts, she attended trainings.

“Perhaps the basis for most of my education came from Project for Public Spaces (PPS), a national advocacy group,” she said. “It grew out of the work of New York planner William Whyte, whose book The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces is fascinating. I learned enough to allow me to ask questions. And then I was fortunate enough to meet people like Doug Bisson, a planner at HDR, who recommended more books.”

After PPS training in New York she returned to Omaha to organize Place Making sessions, which she describes “as a way to engage citizens in helping them decide what their own spaces should look like and discover their own neighborhoods’ potential.” Place Games and Place Definitions workshops were held with neighborhood associations. Program Manager Teresa Gleason leads these sessions today. Ideas get broached, goals set and actions taken to make improvements — from lighting to green spaces to facades.

Through these experiences Spellman and others gained a new sense for how Omaha could be flipped.

“I had to have that ‘Ah-ha’ moment in looking at Omaha because I’ve seen it as I’ve always seen it — family-oriented, hard working, conservative. I loved it but I didn’t see it in terms of its potential,” she said. “Then I saw it in terms of what it could look like — a lively, more interesting Omaha that is cutting edge, exciting and fun.

“You can never see the city the same way again once you see it as what it could be. That’s probably the greatest gift to me — opening my eyes to see what the potential is for this city.”

Spellman is unabashedly devoted to Omaha, where she and her husband, attorney Rick Spellman, moved in the ‘70s. It’s where they raised their three kids. Some of Omaha’s greatest ambassadors didn’t start out here and she’s among them. The former Connie Hoy grew up in Wahoo, Neb. Her family moved there from a farm they had near Lincoln. She enjoyed small town life.

“I probably had the most idyllic childhood. I lived a block away from school. The thing about small towns is you’re forced to do everything because there aren’t enough people. I love the opportunity to sample everything. I think that’s useful.”

Her role of helping Omaha see itself in a new light is in keeping with her background.

“I am first and foremost an educator because that’s what I went to school to be,” the 1965 University of Nebraska-Lincoln graduate said.

She taught high school in Ashland, Neb. for two years while her husband Rick was in law school. Even then she showed a knack for getting broad coalitions of people involved as she started a speech and theater program. Under her direction community productions of South Pacific and Our Town were staged.

“We got the whole town engaged in these productions,” she said.

Sound familiar? She built coalitions as a volunteer with the Junior League, a women’s group that promotes community involvement and leadership development. Her work there led to her involvement with the Chamber, where she spearheaded corporate leadership and public school education initiatives.

In a sense, what this designing woman does today is direct an epic scale version of Our Town where the props and the players are real and the stakes are for keeps.

The more she steeped herself in what constitutes good design the more she saw Omaha for the first time. The striking new face that began emerging downtown and on the riverfront offered a preview of what could be. It increased expectations.

“With the downtown redevelopment we were beginning to see that transformation is possible and energizing and positive. It was a wonderful catalyst to begin to say, Boy, if we can do it downtown, why can’t we translate this throughout our entire city? We can still be hard working and family-oriented but we can also be cutting edge and exciting and fun. We can be competitive in a regional market which we really hadn’t been. All of that, I think, gives a sense of pride, a sense of energy.”

What became known as Omaha By Design evolved from studies, surveys and discussions prompted by Foundation donors. This led to public meetings where citizens weighed in. The work continues today.

“It’s all citizen-led,” she said. “One of the terms we use is, ‘The citizen is the expert — the community is the expert.’ They know best what they want for their community. We just help them see it differently.”

All the feedback called for a citywide approach focusing on key neighborhoods, districts, corridors, sectors that took a more considered approach to development — from signage to setbacks to lighting to landscaping to public art.

The idea’s to create organic, splendid, interconnected, pedestrian-friendly spaces that make Omaha a more pleasant place to live and therefore a more competitive market for attracting and retaining companies and individuals.

“Besides the feel-good aspect there’s an economic component to this as well,” Spellman said. “If you design a building well, if you have a shopping center that’s easily accessible for pedestrians and exciting and attractive, that’s going to be a return on investment.”

The real work began in response to a pair of new Wal-Mart stores slated for Omaha. Objections arose over the plans for the big box projects and their ugly concrete footprints, which all but ignored elements like greenery or enhanced lighting. Spellman, local elected officials, Omaha Planning Department staff and other concerned citizens concluded if the city wanted projects with more curb appeal than design standards must be adopted that compel developers-builders to conform. Rules and regulations with oversight-enforcement teeth were needed.

“In order to create the vision there had to be a change,” she said. “Otherwise, you would have continued to perpetuate the development that’s gone on before.”

Wal-Mart was Omaha’s line-in-the-sand.

“We weren’t content to take the bottom drawer of a Wal-Mart or any box store,” she said. “We were confident enough to say we won’t accept that anymore. We deserve more.”

That’s when her organization decided to undertake a comprehensive plan, called the Urban Design Element, which meant identifying and articulating areas of the city in need of revitalization and redesign. This required the collaboration of a cross-section of city departments, design firms, real estate developers, lawyers, utilities providers, neighborhood associations and others.

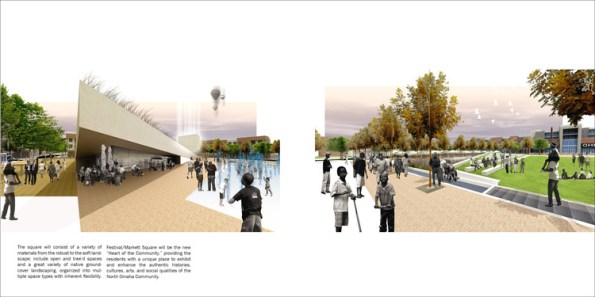

Philadelphia planner Jonathan Barnett helped devise Omaha’s plan. He divided it into three focus areas — Green, Civic and Neighborhoods. “That was one of the best organizational tools we could have come up with,” Spellman said, “because it helps you so much describe it, define it, categorize it, implement it. This way you break it down into very visual, concrete segments that anybody can see. There’s something for everybody.”

A list of goals for each segment is now in place and projects have been targeted within each goal.

The Urban Design Element was not the end game, however.

“It was written not as a plan but as a specific element that once adopted went right into the (city’s) master plan,” she said, “which I think was a brilliant thing. We didn’t want it to be a report that sat on the shelf. Just because it’s part of the master plan doesn’t mean it has the force of law or automatically gets done. It doesn’t unless attention is given to it.

“The highest priority was the implementation of those recommendations that required codification in order to be effective. That became our next major effort.”

In August of 2007 the Omaha City Council unanimously adopted the Urban Design Element into the city’s official master plan. Ideas and goals had been turned into tangible, enforceable codes. As a result, Omaha no longer has to settle for what a developer or builder decides is a sufficient design but the city now has specific standards in place that, by law, must be met.

She said the effort needed both the private and public sectors involved “to make this work and we did have that from the very beginning. It was a wonderful blend that was strategically thought about to make sure that every sector had a voice.”

Spellman got diverse players to sit at the same table and work out the details. Her talent for “bringing people together to get things done” is one of the skills she learned in her 20 years at the Commerce. She managed its Leadership Omaha and Omaha Executive Institute programs and led its education and workforce development initiatives, Omaha 2000 and the Omaha Job Clearinghouse, respectively. Her successes made her a player.

Typical of Spellman, she prefers deflecting attention away from herself and onto others. For example, she credits the Omaha Planning Department with helping make the Urban Design Element a reality.

“I can’t say enough about the role of the Planning Department in making this happen,” she said. “Steve Jensen, Lynn Meyer and Co. are trusted and respected by the development community and they’ve been a real factor in working this through. They were totally professional and patient.”

Her work, however, has been much recognized, including being named The World-Herald’s 2007 Midlander of the Year. She’s previously been the recipient of the Ike Friedman Community Leadership Award and other awards noting her community focus and consensus building.

She said as arduous as creating the Urban Design Element was, “codifying these design standards” was a classic “the-devil’s-in-the-details process” that required innumerable meetings. An expert committee addressed the codification, which among other things put the standards into language that was clear and binding. There was much discussion, argument and compromise.

“It was more technical. It was a smaller, tighter group having to deal with the codes,” she said. “We added more developer-real estate-leasing agent-finance people that really understood the implications of what was going to be asked of them and coupled it with the design community — architects, landscape planners, city department heads — all at the table.

“We thought it was going to be a year’s process. It turned out to be two years. It was the best thing that we did take the two years because nobody had ever done this before. We’re really trying to address so many things from so many different perspectives.”

Spellman said no U.S. city has ever tackled such a sweeping, all encompassing design plan to code.

“Where others had done major sections of code it was usually in a city like Santa Fe, where everything is the same, uniform Southwest look, or a Santa Barbara, where there’s very strict requirements. Well, we didn’t want Omaha to look all the same, so that meant our code doesn’t fit all. Therefore, we really needed to make sure there were no unintended consequences.

“We had to test and reevaluate and retest. There was a several month period where we studied (design) surettes of (mock) urban settings and suburban settings to see how the codes would affect those. Then we learned how topography affects those. It was a true education in how important it is to do it right the first time. It takes time.”

Developers, builders and others who will be working within these codes on future projects expressed various concerns.

“There’s a fear factor,” she said. “What if it doesn’t work? What if it’s going to cost more? What if it’s going to prohibit development? Those are legitimate issues. That’s why it took so long — to be sure that all of us were comfortable with the outcome. The last thing any of us want to do is to hamper economic development. We’re all in this for economic development and quality of life.”

Consequently, nothing’s set in stone. By its nature, urban design is evolutionary.

“It’s not hard and fast,” she said. “Something this big and this broad can’t be perceived as perfect the first time out. That’s why the Technical Advisory Committee decided to stay together to be that sounding board. If the language doesn’t meet the intent then let’s by all means change it. We’re already working on some issues that we discovered need to be changed.”

The committee also serves on the city’s Design Review Board, which is charged with interpreting the codes.

Redesigning Omaha carries the responsibility of being true to all those who’ve participated in the process.

“In a way we’re protecting the interests of all the people that attended meetings and voiced their opinions,” she said. “So we really felt this was a mandate from the community. We went through this process not just as an exercise but as something we want to see because we love our city and we want to make it better. I take that as a responsibility and I don’t want to stop until we’re done.”

Omaha By Design recently released its Streetscape Handbook. This primer for project managers, developers and design professionals offers guidelines for creating enhanced streetscape environments that give careful attention to street fixtures rather than treat them as afterthoughts.

“It deals with all of the street furnishings in the public right of way,” she said. “Signage, street lights, wires, bike racks…If you think about the placement of this stuff you have to have anyway, if you think about maintenance and sustainability and how it relates to each other and how it looks on the street, it makes a whole different visual impression.”

The committee that generated the handbook was made up of architects, landscape designers, city planners, public works professionals, roads experts and “anyone that had something to do with the placement of street furnishings or the streetscape,” she said. “We worked together for 27 months, once a month, to figure out what we needed to do and how we could do it. I think we’re proud of what we’re presenting. It’s an example of people working together because there’s a vision of what we want out city to be some day.”

None of this could happen, she said, without broad support and participation. “We rely heavily on volunteers and community leadership to make these things happen,” she said.

Where is Omaha By Design’s work taking shape?

Projects have now been identified in each of the Urban Design Element’s goals, “which I think is very exciting,” Spellman said. Keep Omaha Beautiful is undertaking one of the first projects — a landscaped highway’s edge at I-680 and Center.

Other efforts are in progress or soon to start. Omaha By Design acts as project manager for some, including the Benson-Ames Alliance, a comprehensive plan for integrating the design of commercial centers with their neighborhoods. The goal is mixed-use centers that blend retail, residential and office in a balanced manner. The plan also addresses transportation, housing and public space issues.

The Alliance has two projects underway — the Cole Creek Project and the Maple Street Corridor Project. The first entails various stormwater construction to help cleanse runoff and moderate the amount of water flowing into Cole Creek; the second designs functional-decorative streetscapes along the Maple corridor and builds on the entrepreneurial growth under way in downtown Benson with a goal of spurring development in neighboring sectors.

All this activity requires Spellman attend many meetings.

“My to-do lists are pages long,” she said.

But she’s doing exactly what she wants to do.

“I’m very fortunate. It’s just a gift. I am totally content and most days very excited about the potential of what we’re doing.”

- The Slowdown and Film Streams development in NoDo or North Downtown

- Related articles

- Omaha’s Film Reckoning Arrives in the Form of Film Streams, the City’s First Full-Fledged Art Cinema (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jeff Slobotski and Silicon Prairie News Create a Niche by Charting Innovation (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Nancy Oberst, the Pied Piper of Liberty Elementary School (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Lit Fest: ‘People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Golden Boy Dick Mueller of Omaha Leads Firehouse Theatre Revival (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Opera Comes Alive Behind the Scenes at Opera Omaha Staging of Donizetti’s ‘Maria Padilla’ Starring Rene Fleming (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Legends: Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce Business Hall of Fame Inductees Cut Across a Wide Swath of Endeavors (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Garry Gernandt’s Unexpected Swing Vote Wins Approval of Equal Employment Protection for LGBTs in Omaha; A Lifetime Serving Diverse Constituents Led Him to ‘We’re All in the Human Race’ Decision (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Linda Lovgren’s Sterling Career Earns Her Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce Business Hall of Fame Induction (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Nick and Brook Hudson, Their YP Match Made in Heaven Yields a Bevy of Creative-Cultural-Style Results – from Omaha Fashion Week to La Fleur Academy to Masstige Beauty and Beyond (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Entrepreneur Extraordinaire Willy Theisen is Back, Not that He Was Ever Really Gone (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- North Omaha Champion Frank Brown Fights the Good Fight (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Memories of the Jewish Midwest: Mom and Pop Grocery Stores, Omaha, Lincoln, Greater Nebraska and Southwest Iowa

Oh, for the days when there was almost literally a grocery store on every corner and a movie theater in every neighborhood. I only know those days through articles, books, movies, photographs, and reminiscences and I am sure the reality did not match my romanticism about them. As fate would have it, the Mom and Pop grocery phenomenon I only got a glimmer of during my childhood became the subject of an assignment I was offered and gladly accepted: as co-editor and lead writer for a Nebraska Jewish Historical Society book project that commemmorates and documents the Mom and Pop Jewish grocery stores that operated in and around the Omaha metropolitan area from approximately the beginning of the 20th century through the 1960s-1970s. But it was Ben Nachman, along with Renee Ratner-Corcoran, who I worked with on the project, that truly realized the book . Ben’s vision and energy got it started and Renee’s commitment and persistence saw it through. I just helped pick up the pieces once Ben passed away a year or so into the project. Ultimately, the book belongs to all the families and individuals who contributed anecdotes, stories, essays, photos, and ads about their grocery stores.

Immediately below is Jewish Press story about the project, followed by an excerpt from the book.

The book is dedicated to the man who inaugurated the project, the late Ben Nachman, who was responsible for starting what is now my long association with both the Jewish Press and the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society. Ben led me to many Holocaust survivor and rescuer stories I ended up writing, many of which can be found on this blog. My stories about Ben and his work as an amatuer but highy dedicated historian can also be found here. I also collaborated with Ben and Renee, as the writer to their producder-roles, on a documentary film about the Brandeis Department Store empire of Nebraska. A very long two-part story I did for the Jewish Press on the Brandeis family and their empire served as the basis for the script I wrote. You can find that story on this blog.

Historical Society publishes grocery store history

by Rita Shelley

11.11.11 issue, Jewish Press

Freshly arrived from Europe a century ago, thousands of men and women found work in South Omaha’s packinghouse and stockyards.

South 24th Street grocer Witte Fried, also a first generation American and a widow with children from ages 2 to 7, knew something of her neighbors’ struggles to survive and prosper. She also knew they needed to eat. According to her descendants, Fried took care to mark prices on the merchandise in her store in several languages. She wanted her customers, regardless of their German, Irish, Italian, Russian, Polish, Greek, Czech or other origins, to have an easier transition into their new world.

Fried’s story is one of many featured in Memories of the Jewish Midwest: Mom and Pop Grocery Stores. Scheduled to be published in November by the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society (NJHS), the book includes recollections of Jewish grocers and members of the families who operated stores throughout Omaha, Lincoln, Council Bluffs and surrounding areas from the early 1900s to the present.

“A history of Jewish owned stores is also a history of the grocery business,” Renee Ratner-Corcoran, NJHS executive director, said. “Beginning with peddlers who traveled from farm to farm to trade their wares for farm produce to sell in the cities, through one-room Mom and Pop stores with adjoining living quarters, to the first large self-service grocery stores, to today’s discount stores that sell housewares and groceries under the same roof, the Jewish community played a vital role in the grocery industry.The book was a dream of Dr. Ben Nachman, an NJHS volunteer whose father owned a small store on North 27th Street. Dr. Nachman died in 2010; publication of the book is dedicated to his memory.

Children of early Jewish grocers who were interviewed for the book or submitted recollections recall the hustle and bustle of buying produce from open air stalls downtown (today’s Old Market) as early as 4 a.m. to stay ahead of the competition. Before there were automobiles, grocers’ children were responsible for the care of the horses that pulled delivery buggies. Mixing the flour and water paste to use for painting prices of the week’s specials on the front window was also the responsibility of children. So were dividing 100-pound sacks of potatoes into five- and 10-pound packages, grinding and bagging coffee, and feeding the chickens. (A kerosene barrel and a chicken coop were located side-by-side in at least one family’s store.).

The book’s publication was underwritten by the Herbert Goldsten Trust, the Special Donor Advised Fund of the Jewish Federation of Omaha Foundation, the Milton S. & Corinne N. Livingston Foundation, Inc., the Murray H. and Sharee C. Newman Supporting Foundation, Doris and Bill Alloy, Sheila and John Anderson, Edith Toby Fellman, Doris Raduziner Marks, In honor of Larry Roffman’s 80th Birthday, and Stanley and Norma Silverman.Increasing prosperity meant housewives had more money to spend. Innovations in transportation and refrigeration also brought changes to the grocery industry, and Jewish grocers were among the first to embrace those changes. More recently, Jewish Nebraskans “invented” some of the country’s first discount chains and wholesale distribution networks, as well as the data processing innovations that made them profitable.

For additional information, contact Renee Ratner-Corcoran by e-mail at rcorcoran@jewishomaha.org or by phone at 402.334.6442.

Excerpts from the book-

©by Leo Adam Biga

Memories of the Jewish Midwest: Mom and Pop Grocery Stores Omaha, Lincoln, Greater Nebraska and Southwest Iowa

Jews have a proud history as entrepreneurs and merchants. When Jewish immigrants began coming to America in greater and greater numbers during the late 19th century and early 20th century, many gravitated to the food industry, some as peddlers and fresh produce market stall hawkers, others as wholesalers, and still others as grocers.

Most Jews who settled in Nebraska came from Russia and Poland, with smaller segments from Hungary, Germany, and other central and Eastern European nations. They were variously escaping pogroms, revolution, war, and poverty. The prospect of freedom and opportunity motivated Jews, just as it did other peoples, to flock here.

At a time when Jews were restricted from entering certain fields, the food business was relatively wide open and affordable to enter. There was a time when for a few hundred dollars one could put a down payment on a small store. That was still a considerable amount of money before 1960, but it was not out of reach of most working men who scrimped and put away a little every week. And that was a good thing too because obtaining capital to launch a store was difficult. Most banks would not lend credit to Jews and other minorities until after World War II.

The most likely route that Jews took to becoming grocers was first working as a peddler, selling feed, selling produce by horse and wagon or truck, or apprenticing in someone else’s store. Some came to the grocery business from other endeavors or industries. The goal was the same – to save enough to buy or open a store of their own. By whatever means Jews found to enter the grocery business, enough did that during the height of this self-made era, from roughly the 1920s through the 1950s, there may have been a hundred or more Jewish-owned and operated grocery stores in the metro area at any given time.

Jewish grocers almost always started out modestly, owning and operating small Mom and Pop neighborhood stores that catered to residents in the immediate area. By custom and convenience, most Jewish grocer families lived above or behind the store, although the more prosperous were able to buy or build their own free-standing home.

Since most customers in Nebraska and Iowa were non-Jewish, store inventories reflected that fact, thus featuring mostly mainstream food and nonfood items, with only limited Jewish items and even fewer kosher goods. The exception to that rule was during Passover and other Jewish high holidays, when traditional Jewish fare was highlighted.

Business could never be taken for granted. In lean times it could be a real struggle. Because the margin between making it and not making was often quite slim many Jewish grocers stayed open from early morning to early evening, seven days a week, even during the Sabbath, although some stores were closed a half-day on the weekend. Jewish stores that did close for the Sabbath were open on Sunday.

Jewish grocery stores almost always became multi-generation family affairs. The classic story was for a husband and wife to open a store and for their children to “grow up” in it. In some families there was a definite expectation for the children to follow and succeed their parents in the business. But there were as many variations on this story as families themselves. In some cases, the founder, almost always a male, was joined in the business by a brother or brothers or perhaps a brother in law. Therefore, a child born into a grocer family might have one or both parents and some combination of uncles, aunts, siblings, and cousins working there, too.

Of course, not every child followed his folks into the family business. Because most early Jewish grocers did not have much in the way of a formal education, the family business was viewed as a springboard for their children to complete an education, even to go onto college. It was a means by which the next generation could advance farther than their parents had, whether in the family grocery business or in a professional field far removed from stocking shelves and bagging groceries.

Some Jewish grocers went in and out of business in a short time, but many enjoyed long runs, extending over generations. Some proprietors stayed small, with never more than a single store, while others added more stores to form chains (the Tuchman brothers) and others (like the Bakers and the Newmans) graduated from Mom and Pop shops to supermarkets. Some owners made their success as grocers only to leave that segment of the food business behind to become wholesale suppliers and distributors (Floyd Kulkin), even food manufacturers (Louis Albert).

Whatever path Jewish grocers took, the core goal was the same, namely to provide for their families and to stake out a place of their own that offered continued prosperity. For a Jewish family, especially an immigrant Jewish family, owning a store meant self-sufficiency and independence. It was a means to an end in terms of assimilation and acceptance. It was a real, tangible sign that a family had arrived and made it. Most Jewish grocers didn’t get rich, but most managed to purchase their own homes and send their kids to college. It was a legitimate, honorable gateway to achieving the American Dream, and one well within reach of people of modest means.

For much of the last century Jewish grocery stores could be found all over the area, in rural as well as in urban locales, doing business where there were no other Jews and where there was a concentration of Jews. In Nebraska and Western Iowa there have historically been few Jewish enclaves, meaning that Jewish grocers depended upon Gentiles for the bulk of their business. Dealing with a diverse clientele was a necessity.

In some instances, Jewish grocers and their fellow Jewish business owners catered to distinct ethnic groups. For example, from the 1920s through the 1960s the North 24th Street business district in Omaha was the commercial hub for the area’s largely African-American community. During that period the preponderance of business owners along and around that strip were Jewish, including several grocers, some of whom lived in the neighborhood. These circumstances meant that Jews and blacks in Omaha were mutually dependent on each other in a manner that didn’t exist before and hasn’t existed since. When the last in a series of civil disturbances in the district did significant damage there, the last of the Jewish merchants moved out. Only a few Jewish owned grocery stores remained in what was the Near Northside.

Until mechanical refrigeration became standard, customers had to shop daily or at least every other day to buy fresh products to replenish their ice boxes and pantries. Having to shop so frequently at a small, family-run neighborhood store meant that customers and grocers developed closer, more personal relationships than they generally do today. Grocers not only knew their regular customers by name but knew their buying patterns so well that they could fill an order without even looking at a list.

Home delivery was a standard service offered by most grocers back in the day. Some stores were mainly cash and carry operations and others primarily charge and delivery endeavors. Taking grocery orders by phone was commonplace.

Most grocers extended credit to existing customers, even carrying them during rough times. It was simply the way business was conducted then. A person’s word was their bond.

Fridays were generally the busiest day in the grocery business because it’s when most laborers got paid and it’s when families stocked up for the big weekend meal most households prepared.

Jewish grocers were among the founders and directors of cooperatives, such as the United Associated Grocers Co-op or United AG and the Lincoln Grocers Association, that gave grocers increased buying power on the open market.

With only a few exceptions today, the intimate, family neighborhood stores are a thing of the past. As automobiles and highways changed the landscape to accommodate the burgeoning suburbs, newer, larger chain stores and supermarkets emerged whose buying and selling power the Mom and Pops could not compete with on anything like an even basis. Thus, the Mom and Pop stores, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, began fading away.

Because Jewish grocers were such familiar, even ubiquitous fixtures in the community, the majority population gave little thought to the fact that Omaha Jewish merchants like the Bakers (Baker’s Supermarkets) or the Newmans (Hinky Dinky), who began with Mom and Pop stores, led the transition to supermarket chains. For much of the metro’s history then, Jews controlled a large share of the grocery market, helping streamline and modernize the way in which grocers did business and consumers shopped.

It is true the one-to-one bond between grocer and consumer may have all but disappeared with the advent of the supermarket and discount store phenomenon. The days of grocers filling each customer order individually went by the wayside in the new age of self-service.

One thing that’s never changed is the fact that everybody has to eat and Jews have been at the forefront of fulfilling that basic human need for time immemorial. The Jewish grocer was an extension of the friendly neighborhood bubbe or zayde or mensch in making sure his or her customers always had enough to eat.

Tired of being tired leads to new start at John Beasley Theater

- If you’re a return visitor to this blog, then you may recognize that the subject of this next story, the John Beasley Theater & Workshop in Omaha, is one I’ve written about a number of times. If not the theater itself, then I’ve written about its productions, and if not productions then I’ve written about founder and president John Beasley. This time around I write about some recent financial woes the theater’s been experiencing and how with the help of friends and strangers the organization now has what it needs to go on with the 2011-2012 season, which was in jeapordy until John Beasley went public with the need. As a niche theater that largely but not exclusively produces work by African-American playwrights – with its current production of Radio Golf the theater’s now staged the entire 10-play cycle of African-American life that August Wilson wrote – the JBT presents a slate of work that otherwise might not be produced in Omaha. The theater is a labor of love for Beasley, a stage-film-television actor who views his enterprise as a way to bridge cultural differences and as a forum for black actors to learn their chops in a white majority city that has traditionally not embraced its black community and not provided many theater opportunities for aspiring, emerging or even established black theater artists.

Tired of being tired leads to new start at John Beasley Theater & Workshop

©by Leo Adam Biga

Published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

John Beasley got tired of being tired.

By now, you’ve likely learned the John Beasley Theater & Workshop’s urgent appeal for funds to relieve its financial distress has been answered and the once endangered 2011-2012 season saved. But you probably don’t know the back story of its troubles or why founding namesake and president, John Beasley, is putting himself out there to share these travails and to make the case for the theater’s continued existence.

Ever since launching the theater in 2000 the stage-film-television actor has largely bankrolled the nonprofit himself. Year after year, with no real administrative staff and fronting a board short on resources and contacts, the theater’s only barely scraped by. This despite strongly reviewed work, some outright smash hits, including shows held over for extended runs. Its niche producing African-American plays, most notably the August Wilson repertoire, has distinguished it but not always helped it either.

The kindness of strangers, an occasional grant, meager season-ticket sales and box office receipts from a 100-seat house only go so far. It’s left Beasley holding the bag, writing personal checks to make-up the shortfall.

“I’ve underwritten most everything we’ve done, but it’s been at the point for a long time now that I thought the theater should be self-sustaining rather than to just keep going in my pocket,” he says. “I’m not getting anything financially out of the theater.”

There have been times, even quite recently, when there wasn’t enough in the theater’s coffers to pay his son, artistic director Tyrone Beasley, or directors’ fees, much less vendors. So he paid Tyrone and creditors himself.

Even the theater’s performing home in the LaFern Williams South Omaha YMCA at 3010 R Street, where the old Center Stage Theatre used to operate, was no sure thing.

“We were going through a period there where the oral contract we had with OHA (the Omaha Housing Authority agency that owned the building before the YMCA acquired it) had expired. Without that space being donated we wouldn’t have made it,” says Beasley “That was a big consideration at the end of that contract. It was up for renewal and the YMCA was saying, ‘What can you pay?’ and I told them we’re really in a situation where we can’t pay anything, They worked out a really nice arrangement for us and I’m really grateful to the YMCA for the use of that space.

“Without that, I think we would have closed.”

He acknowledges that in some ways he’s ill-prepared to run a theater, but he’s stuck it out because by his reckoning the whole venture is a calling.

“I didn’t set out to open a theater. I thought it was put on me for a reason. I believe things happen for a reason, so I’ve always talked to God in this way: ‘If you want me to be here, you’re going to have to provide the way.’”

Divine providence was necessary, he says, “because we came in here without any grants. OHA gave us the space but they didn’t give us any money to go with it, and not ever having a board that would raise funds for me, it’s been a struggle. The fact we’ve managed to stay here as long we have is a miracle in itself given I never had any experience in theater administration.

“But, you know, God has been good and has allowed us to be here 11 years and I don’t think He’s brought us this far to say, Ok, it’s over now. We haven’t completed our mission and we still have a ways to go, and I still have a vision for the theater.”

That vision, which encompasses a second theater he wants to build from the ground up in North Omaha as a regional attraction, has often seemed far off.

Rendering of the revitalized North 24th and Lake St. corridor where Beasley wants to build a new theater

“It’s always been a day to day thing. You can’t imagine what it’s like getting up every morning with this on your mind, wondering — how are we going to take care of this? how are we going pay these people?”

The recession hasn’t helped matters.

“Revenues have been flat and our expenses keep mounting. The box office only pays a little bit of the expenses. Our small house is not a big revenue source. It will pay some bills, but then you’re scrambling where you’re going to get the money for this and that. Attendance numbers are down because of the recession. These are entertainment dollars and with discretionary spending theater might not be at the top of the list.”

In noting that other theaters have dropped prices, he says, “we’ve looked at doing the same thing,” hastening to add, “But it wont necessarily guarantee our attendance will go up, and I’ve always felt that if people think it’s too cheap, they’ll assume its probably not worth it.” He’s heard grumbling in the black community his theater’s too pricey, an opinion he disputes. “We weren’t overcharging,” he says, noting that people don’t think twice about plopping down considerably more money to see touring gospel plays.

“Our work might not be as glitzy but the quality is as good as any that comes through as far as the acting is concerned, because I see what comes through and I don’t think there’s a lot of talent sometimes.”

The theater’s woes extended to marketing and publicity, which have been largely limited to post cards and print ads, leading Beasley to doubt it was even reaching its audience in this online social media age.

Approaching the start of the 2011-2012 season, kicking off with August Wilson’s Radio Golf, Beasley decided he’d had enough.

“I told the board that going into this season I needed $20,000 for the first show and I wouldn’t greenlight it until I received $10,000. And I asked the board, ‘Who’s going to lead this?’ I didn’t have any volunteers because my board is more of a working board. They’re willing to put in the work but they’re just not fundraisers, and that’s just the way it is. So out of frustration I said, ‘Well, alright, I’ll do it,’ and so I stepped out. I didn’t know how I was going to do it but I believe when you step out in faith good things happen, they just happen. God or whatever provides a way.”

He laid out the precarious situation to friends of the theater with, “This is a crossroads for us. If this doesn’t happen I can’t just go along with this kind of pressure anymore…”

Then he went public Sept. 1, posting a Facebook appeal that spelled out in dire terms the make-or-break scenario confronting his South Omaha theater. His message stated flat out the JBT would close unless $10,000 was obtained. KETV, the Omaha World-Herald and other media picked up the story.

By mid-September $30,000 was either donated or pledged, meaning the season was on and the theater’s future, at least for now, secured. For Beasley, whose fierce demeanor and brickhouse physique belie a soft heart, the outpouring has taken him aback and given his theater mission a new lease on life.

“The best thing about going public is to receive the love from Omaha we received from people we didn’t know. When I found out all you had to do was ask and people would respond…” he says, his voice trailing off in wonder.

“It’s put us in a place where I’m really optimistic about not only the season but about the future of the theater. This has given some breathing room we have never had before. It’s given us a budget, and that budget will take care of a lot of things. It will also help us pay off the vendors we owe.”

He says the community’s embrace has come from both long-time theater supporters and individuals with no connection to the organization. Support has come in amounts as small as $20 and as much as $5,000. The Myth bar in the Old Market threw a fund-raising party Sept. 20 that raised about $1,400.

Beyond the money collected, there’s new blood cultivated. As a result, he says the JBT now has a circle of volunteers with the skills to build a stable enterprise.

“I’ve put together a committee of people I’ve never had in place before,” says Beasley. “These people know what it’s all about.”

Development professional Jeff Leanna is the new executive director. He, along with management communications specialist Wendy Moore and her real estate executive husband Scott Moore are heading up marketing, solicitation, subscription campaigns and beefing up its online presence. Beasley’s in the process of “weeding out” some inactive board members and replacing them with energetic new members. Taken together, he says, the JBT has people in place to “take care of the administrative things and business part of it, and that’s such a relief. We’ve been really lacking in that end of it. My son and I are creative people.”

He expects fund-raisers, grant applications, membership programs and marketing-development campaigns to happen year-round. “That’s part of the plan,” he says. “We’re even reaching out to Oprah now,” he says, and hints that overtures may be made to actor-director Robert Duvall, whom he acted alongside in the The Apostle.

Now that the JBT is on more solid ground, he says, “I’m glad I went public with it. People now are aware of the need of the theater.” He says telling the theater’s story has also laid to rest some myths — like the city was funding the venue. “There was a misconception that we had everything we needed,” he says, and that he had limitless deep pockets.

“I think we had to hit bottom before we could have this turning point. I think this really was the catalyst to take us to that next level.”

For a proud man like Beasley airing his plight is not easy. But he sees it as the only way to explain why the theater is worth fighting for in the first place.

“At first I had some reservations, because you don’t want people to think you’re struggling or failing, but then I came to the realization we serve a purpose. Who else is going to do August Wilson or Suzan-Lori Parks or Eugene Lee or even Ted Lange? And where are the opportunities for up and coming black actors?

“Through the years we’ve touched a lot of lives. We’ve changed lives. We’ve got some good people we’ve brought along. Andre McGraw first came on the stage in our theater — now he’s going to school to study theater at UNO. TammyRa (Jackson) is an outstanding talent I’m going to lose soon — she’s talented enough to work out of town. I’m just so proud of her. Dayton Rogers is another fine actor coming up. Phyllis Mitchell-Butler is in a production at the Playhouse now. Where else would they have gotten this opportunity?”

The JBT’s also offered a window into the black experience that’s given white Omaha a perspective sorely lacking outside that prism.

“I guess I’m most proud of the exposure to black culture we’ve given Omaha,” he says, adding that “75 percent of our patrons come from West Omaha.”

Fear or loathing of other cultures, he says, is less likely when there’s communication and knowledge.

“The more you learn about something, the more you understand something — then you can’t hate it. I think we’re bridging gaps.”

He says the divides that stymie America plague the city as well, and the arts and theater, perhaps his theater especially, can serve to heal.

“The country can’t move forward because of politics and ideologies. Nobody’s trying to understand the other side, there’s no compromise. If you can understand the other side then you can create a dialogue. If you have a dialogue then things can happen. That’s true nationally and it’s true in this city. The disparity between blacks and whites in this city is the worst than any place in this country.”

Among the reasons he’s hung his theater on the back of August Wilson’s body of work is the playwright’s cycle of 10 plays revealing the arc of African-American life in the 20th century as seen through the eyes of Pittsburgh’s Hill District denizens.

August Wilson visiting Pittsburgh’s Hill District

“I love August Wilson’s work because it’s a true reflection,” says Beasley, whose extensive credits include productions of Wilson plays in major regional theaters. “I know these people. One of the goals when I opened the theater was to introduce Omaha to August Wilson, because he’s such an important part to my whole career and has created work that will keep middle aged black men working forever. I can do Wilson till I’m ready to die. It’s just a rich legacy he’s left black actors and the world for that matter. His stuff crosses all lines.

“You’ve known people like Troy Maxon (Fences). I’ve had people come up to me wherever I’ve done this and say, ‘That was my dad’ or ‘I knew that guy.’ You know these people and these situations, the relationships between sons and fathers. Life has passed them by and they haven’t dealt with it very well.”

With Radio Golf, the last in the cycle, the JBT’s now performed each of the 10 Wilson plays, including some (Fences, Two Trains Running, Jitney) staged multiple times. Radio Golf’s look at gentrification efforts in a historical black neighborhood has particular resonance for Beasley and the new North Omaha theater he envisions. Leo A Daly is nearing final designs for the unfunded project, which would not replace the existing site, but rather complement it. It’s a project personal to Beasley on several levels.

“We’d like to put it between 25th and 24th Streets in that Lake Street corridor. It would be right off the Interstate. If you build up it, they’ll come. That would be my field of dreams. We want to be a destination and an anchor to the cultural revitalization of this district. I grew up in this neighborhood, it’s my neighborhood. I was here when they tore it down and burnt it down. I remember giving a little speech here to rioters — ‘Why you tearing down your own neighborhood? If you’re that angry, go downtown.’ It was opportunistic hoodlums that did that stuff and then you have that mob mentality.

“I just want to be a part of rebuilding the neighborhood. It’s changed. Regentrification is happening.”

Should the new theater come to pass, it would be another piece in the resurgent arts-culture district slated for the area, where the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and Great Plains Black History Museum already operate and where Brigitte McQueen’s Union for Contemporary Art is due to locate.

None of it means the JBT is out of the woods.

“I don’t want people to think we’re OK, we’re not OK,” says Beasley. The influx of funds, he says, “is a start, but I’m looking for a $200,000 budget for this season. We appreciate any donations.” As a thank you to the community the theater offered free admission for its season-opening, Sept. 30-Oct. 2, weekend.

Visit www.johnbeasleytheater.org for donation and season ticket info.

Related articles

- John Beasley and Sons Make Acting a Family Thing at the John Beasley Theater & Workshop and Beyond (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Crowns: Black Women and Their Hats (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Golden Boy Dick Mueller of Omaha Leads Firehouse Theatre Revival (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native American Survival Strategies Shared Through Theater and Testimony (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Dick Boyd Found the Role of His Life, As Scrooge, in the Omaha Community Playhouse Production of the Charles Dickens Classic ‘A Christmas Carol’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- John Beasley Has it All Going On with a New TV Series, a Feature in Development, Plans for a New Theater and a Possible New York Stage Debut in the Works; He Co-stars with Cedric the Entertainer and Niecy Nash in TVLand’s ‘The Soul Man’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Synergy in North Omaha Harkens a New Arts-Culture District for the City (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Leola keeps the faith at her North Side music shop

Here is the promised cover profile I did on Leola McDonald, whose Leola’s Records and Tapes shop in North Omaha was an African American cultural bastion for years before she decided to close the operation. This piece for The Reader (www.thereader.com) appeared as business was appreciably slowing for her, and as the short follow up piece I posted earlier here reported, she eventually called it quits. It was no great surprise. The times were changing, and she wasn’t changing with them. She said so herself. The writing was on the wall and so it was just a matter of time.

Leola keeps the faith at her North Side music shop

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (wwwthereader.com)

The iridescent, rainbow-palette mural splayed across the brick west wall spells LEOLA’S in big block letters. The name on the side of the Omaha music store formally known as Leola’s Records and Tapes belongs to founder/owner Leola McDonald. Both the handle and the woman are synonymous with music on the north side.

Her small shop at 56th and Ames Avenue is where today’s beat generation heads for the latest hip hop and rap tracks, including hard to find mixes and chopped and screwed versions of hit cuts.

Bright as the colors decorating that wall is Leola’s own passion for music.

“I love music. I always have. I used to play it all. At one point in my life I even sang. I sang in the church choir,” said the former Leola Ann Francis.

A 68-year-old church lady who prefers gospel may not be what you expect behind the counter of an urban music store carrying CDs and tapes with R-rated lyrics, but that’s exactly what you get. Her operation is pretty much a one-woman show. Oh, her grandkids come by to help some, but “mostly I do it by myself,” she said.

As its sole proprietor, she’s there seven days a week. Waiting on customers. Answering the phone. Registering sales. Bantering back and forth with whoever saunters on in, some just to “conversate” with her. Others to inquire after new releases. The door bell rings and it’s a young man, Eric Miller, who’s been shopping there since he was a boy.

“Hi, Miss Leola.” “What you want, babe?” “I’m lookin’ for that CD that got, uh, Slim Thug and, um, Young Zee-Zee on it…” She searches the shelves in back of her. Another young man comes in, hawking a box-full of high-end electronic gadgets. Leola tells him, “Honey, my money’s funny and my change is strange. I’m broke.”

Whatever brings them there, she greets all with — “Hey, sweetie” or “Hey, babe” or “How ya doin’?” or “What’s up, doc?” — in a musky voice that years of cigarette smoking ruined for singing. She used to love to sing. In the Sunday baptist church choir as a youth. In church-sponsored competitions. She once dreamed of performing professionally. That was a long time ago.

“I could sing once in my life…I won every contest I got into. But I messed up my own voice. I started smoking and drinking. I was grown. I could do what I wanted to do. But didn’t nobody suffer for it but me. Now, I can’t carry a tune across the street and bring it back in one piece,” she likes to say.

That doesn’t change her passion. That’s why she’s still at her store every day when most women her age are retired.

“I love music and I love people. So, it’s easy for me. And you really have to to deal with this because you can get some fools in here, and sometimes it’s more than one, and you have to deal with ‘em,” said the Omaha native, who divided her growing up between here and Cheyenne, Wyoming, where her mother moved after splitting up with her father.

Then there’s “that crap they call rap” she feels obliged to carry. It’s what sells these days. It doesn’t mean she has to like it, though. Still, she must be familiar with the artists and their work. Like it or not, it’s what customers want.

“Yeah, I pretty much have to be up on all of it now. I don’t particularly care for it, but hey, maybe if I was these kids’ age…But I don’t think I would go in for it. To me, it’s nothin’ but noise. But different strokes for different folks,” she said.

Eric Miller said despite the generation and taste gap, McDonald stocks what’s in vogue. “You can find things here you can’t find at a lot of places,” he said. Carmelette Snoddy said she prefers Leola’s for its “quality. Like with these mixed CDs,” she said, holding up a few, “you can buy them off the streets, but they’re not quality. They don’t play as good.”

Leola tries to ensure customers know what they’re getting.

“If they don’t know what something sounds like, I’ll play the music for them, so they’re not just buying something blind. I’ve always done that,” she said.

Long before rap, back when jazz, blues, R & B and soul ruled the charts, she was a respected black music source. Music buff Billy Melton of Omaha said he often relied on her opinion in compiling some of his extensive collection.

“She’s very studious. She knows music. She always had what I was looking for,” Melton said. “And she loves what she’s doing now, too. She’s been faithful to that music line. I just wish she would have stayed with the older music, but there’s no money in that. She knows I love music and she’s given me pictures and things of older artists over the years. She’s quite a gal.”

Her savvy got her a job at the Hutsut, a now defunct music store. Then an advertising salesperson with the Omaha Star, she called on the store one day. When she saw the clerks couldn’t answer customers’ questions about black music, she offered to help. The owner agreed and she so impressed him he hired her on the spot.

She and a partner soon opened their own store, Mystical Sounds. She then went solo. Leola’s followed. For a time, she ran both. For the last 30 years, just Leola’s.

While most of her store’s inventory is given over to current CDs or tapes, she reserves a few bins and racks for old-school vinyl recordings.

Her own personal collection of CDs, LPs, 45s and 8-tracks, drawn from four decades in the business, is all R & B and gospel.

“Gospel music to me is like no other. I love it. Nothing compares…There’s just something about it.”

There’s another reason she opens the doors of her business daily. As a small independent, she’s squeezed by national chains and bled by music pirates. With so many under selling her, she can’t afford not to light up the neon Open sign.

“I don’t have a choice. I have to work. If I didn’t have to work, God knows at my age I wouldn’t be. I’m sure doing this for the love of it. Besides, I’m too old to go get a job. I can’t even think about it. But if push comes to shove and that’s what I have to do to survive…”

Profits are down as a result of black marketeers. Her no-return policy is aimed at pirates who buy CDs, copy for resell and bring back for a refund. “Like I tell ‘em, I wasn’t born yesterday. I was born the day before yesterday. You have too much competition from the bootleggers,” she said. “They stand on the street and they make more than I do sittin’ up here. Why, it’s not fair…I have sat up in here all day long and gone from open to close and walked out the door with $20. Before, it might have been $500-$600 in the drawer. So, there’s no comparison.”

That’s why she takes umbrage when some suggest she pack it in and rest easy on her supposed riches. “If I had the money people tell me I have I probably wouldn’t be here,” she said. “But I love to work.” It’s not as if she has a pension or retirement fund to fall back on. “No, when you work for yourself, unless you save or invest your own money, you don’t have any. And I had four kids to raise, so I didn’t do any saving,” said the twice-married, twice-divorced McDonald.

Single is something she never counted on being at 68. But things never quite worked out with the men in her life. Like any young woman coming of age in the 1950s, she bought into the happily-ever-after ideal.

“I never wanted to be (single). It just happened. Back then, you were to get married, have some kids and be happy. Well, I got married, had the kids, but damn if I was happy,” she said, laughing at herself. She takes it all in stride. “If you don’t have any regrets, you haven’t had any life,” she said.

Faith has a way of healing wounds and easing doubts. Church is where she renews herself. Mount Nebo Baptist Church is where she gives praise and worship.

“I’ve always liked church. It’s been a very short time I wasn’t in the church. Now, I go every Sunday and, if I can, Wednesdays, too. It’s just that I enjoy it so much.”

With that, she turns up the boombox on a cut from the William Murphy Project’s All Day CD. The rousing choir anthem fills the store, rising, rising…the spirit moving her to answer the call…“Oh, yes…He got it together. He got them together…”. As the words “I am trusting you, to bring me through” reverberate, she hums and sings along, swaying to the beat. Hearing the lyric — “So, all you’ve got to do is…” — she finishes it with “Be strong…”

Be strong, Miss Leola, be strong.

hoto ©photo from DJ Smove

hoto ©photo from DJ SmoveRelated articles

- Miss Leola Says Goodbye (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Walking Behind to Freedom, A Musical Theater Examination of Race (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- An Inner City Exhibition Tells a Wide Range of Stories (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omahans Take Stock of the African-American Experience in Their Hometown (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Overarching Plan for North Omaha Development Now in Place, Disinvested Community Hopeful Long Promised Change Follows (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Soon Come: Neville Murray’s Passion for the Loves Jazz & Arts Center and its Role in Rebirthing North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Art as Revolution: Brigitte McQueen’s Union for Contemporary Art Reimagines What’s Possible in North Omaha (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Miss Leola Says Goodbye

As music stores went, it wasn’t much, but it was a fixture in Omaha’s African-American North Omaha community, and when owner Leola McDonald decided to close her Leola’s Records and Tapes the decision was met by an outpouring of regret and fond memories. I did this short piece for The Reader (www.thereader.com) in the wake of her announcement she was closing shop. It appeared not long after a cover profile I did on Leola for the same paper. I will soon be posting that cover. She and her store are missed.

Miss Leola Says Goodbye

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Miss Leola is moving on and the African-American community she served for decades at Leola’s Records and Tapes is treating her retirement as a loss akin to a death. Since Leola McDonald announced she’s closing her music store at 5625 Ames Avenue, mourners have filed in to pay their respects.

Felix Hall was among them last Friday. “What’s up, doc, how ya’ doin’?” Leola greeted the middle-aged man from behind the counter. “Oh, pretty good,” said Hall, before choking up to proclaim, “I saw in the news you were going out of business and I just had to come in to say goodbye.” “Well, thank you, that was nice of you,” a visibly moved Leola said.

It’s been like that now for weeks.

Attired in slacks and a T-shirt imprinted with aphorisms to motherhood, Leola, a mother and grandmother, has been a surrogate parent for neighborhood kids who “grew up” in her store. One of these, Marcus Roach, 18, said he and his posse have “been coming up here for years. A lot of people come up here. Yeah, everybody knows Miss Leola.”

Jason Fisher, 31, owner of the building housing Leola’s and his own multi-media company downstairs, can attest to the respect she holds.

“Miss Leola is known immensely throughout the north Omaha community. It’s unreal what kind of impact you can have on a community in 30 years. Just about everybody knows her like she’s the President,” he said.

“I think she’s kind of like the community’s grandma,” said granddaughter Mercedes Smith. “She’s always looked out for everybody that came to her…People having a bad day come in and talk to her because they know she’ll make them feel better about who they are. She’s a good person.”

“Momma’s real…always lovin’ and always levelin’ with someone,” her son Seth Smith said. Mercedes feels her grandma’s personal stamp will make her missed. “This is not like Sam Goodies or any of the other (independent) music stores closing around the country. She’s the cornerstone of the community.” “I don’t understand it, she’s been here forever,” a young man in search of a CD said.

Leola doesn’t want to leave, but business has lagged. “In the last two years I’ve seen it go down, down, down…” she said. National chains hurt enough, but there’s no competing with music pirates. “It’s so much on the streets now,” she said. The cruelest rub is when black marketeers get source material from Leola’s to burn and then under sell her with it. “It’s just sad that somebody who always tried to be fair and right and correct in everything she did has to suffer,” Smith said.

The woman who’s become an institution is pragmatic about it all. “I wanted it to last a little bit longer, but I guess my biggest problem is I haven’t moved with the times,” Leola said. “I’m still over there, while the times are over here. It happened and I didn’t even realize it. I’m saddened with it and I will miss it. I enjoyed what I was doing and if I was a little bit younger I’d still be doing it.

“I was young when I started and I ain’t young no more — no parts of it.”

Her legacy and her 70th birthday will be celebrated August 11 with a 6:30 p.m. reception at Loves Jazz & Arts Center, 2510 N 24th Street.

But, as Fischer noted, “This isn’t the end of Leola’s, it’s a new beginning.” Soon after Leola closes shop around August 10, he plans to make renovations to the existing space and reopen as Leola’s Urban Avenue, a retail music store “with a singular focus on independent artists, underground music and diversified merchandising.” As for the friend Leola was to the community, he’ll try to represent. “We’ll try to keep it going,” he said.He’s keeping Leola’s in the title to play off her good name and “to carry that torch for her and her family.”

“It gives me a good feeling that somebody cares enough about me to keep the name. I appreciate it. He’s been great to me,” Leola said of Fischer.

Beyond the name, she’s sure a little piece of her will remain in the new store. “I think it will,” she said. She plans to move to Calif., where she has family.

Related articles

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Native Omaha Days: A Black is Beautiful Celebration, Now, and All the Days Gone By (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Family Thing, Bryant-Fisher Family Reunion (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Synergy in North Omaha Harkens a New Arts-Culture District for the City (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry

Two well-connected players on the Omaha entrepreneurial scene and two stalwart figures in efforts to revitalize predominantly African-American North Omaha are Michael Green and Dick Davis. The Omaha natives go way back together and they share a deep understanding of what it will take to turn around a community that lags far behind the rest of the city in terms of income, commerce, jobs, education, housing starts, et cetera.

Lifetime Friends, Native Sons, Entrepreneurs Michael Green and Dick Davis Lead Efforts to Revive North Omaha and to Empower its Black Citizenry

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horizons

Growing up in the late 1940s-early 1950s, Michael Green and Dick Davis knew The Smell of Money from the pungent odors of the bustling packing plants and stockyards near the Southside Terrace apartments they lived in. Buddies from age 4, these now middle aged men began life in similar disadvantaged straits, yet each has gone on to make his fortune.

Instead of the old blue collar model they were exposed to as kids, they’ve achieved the Sweet Smell of Success associated with the fresh, squeaky clean halls of corporate office suites. Education got them there. Each man holds at least one post-graduate degree.

Along the way, there have been some detours. As kids they moved with their families to North O, where they became star athletes. They were teammates at Horace Mann Junior High before becoming opponents at rival high schools — Green at Tech and Davis at North. Both earned accolades for their gridiron exploits as running backs. Green, a sprint star in track, was a speed merchant, yet still rugged enough to play tackle, fullback and linebacker. Davis, a two-time unbeaten state wrestling champ, was a bruiser, yet still swift enough to outrun defenders.

The Division I football recruits reunited as teammates at Nebraska in the mid-’60s — excelling in the offensive backfield under head coach Bob Devaney and position coach Mike Corgan. They never saw action at the same time. Green, a halfback his first two years, co-captained the Huskers’ 1969 Sun Bowl championship team at fullback. Davis was in the mold of the classic blocking, short yardage fullback but he could also catch passes out of the backfield. Drafted a year apart by the NFL, they each pursued pro football careers, but not before getting their degrees — Green in economics and marketing and Davis in education. It wasn’t long before each opted to take a different route to success — one that involved brain, not brawn and three-piece-suits, not uniforms or helmets.

They ended up as executives with major Omaha companies. Today each is the owner of his own company. Green is founder, president and chief investment officer of Evergreen Capital Management, Nebraska’s only minority-owned registered investment advisor. Davis is CEO of Davis Cos., a holding company for firms providing insurance brokerage, financial consulting and contractor development services. Green handles hundreds of millions of dollars in managed assets for institutional clients. Davis Cos., with offices in multiple states, generates millions in revenues and is one of Omaha’s fastest growing firms.

The two men’s stories of entrepreneurial success are remarkable given that in the era they came up in there were few African American role models in business. Back in the day, blacks’ best hopes for good paying jobs were with the packing plants, the railroad or in construction. Few blacks made it past high school. One gateway out of the ghetto and into higher education was through athletics, and both Green and Davis were talented enough to earn scholarships to Nebraska. The opportunities and lessons NU afforded them — both in the classroom and on the field — opened up possibilities that otherwise may have eluded them.

Having come so far from such humble beginnings, neither man has lost sight of his people’s struggle. Both are immersed in efforts to address the problems and needs facing inner city African Americans. Green and Davis are leaders in a growing Omaha movement of educated and concerned blacks working together with broad private-public coalitions to make a difference in key quality of life categories. These initiatives are putting in place covenants, strategies, plans, programs and opportunities to help spur economic development, create jobs, provide scholarships and do whatever else is needed to help blacks help themselves.

Some efforts are community-driven, with Green and Davis serving as committee members/chairs. Others are spearheaded by the men themselves. For example, Davis is the driving force behind the North Omaha Foundation for Human Development, the Davis-Chambers Scholarship Endowment and Omaha 20/20, efforts aimed at community betterment, educational opportunities and economic development, respectively. Green has led a minority internship program that guides young black men and women into the financial services field. He helps direct the Ahman Green Foundation for Youth Development, which awards grants to youth organizations and holds a week-long football/academic camp. The foundation’s namesake, Husker legend Ahman Green, is his nephew.

Individually and collectively Green and Davis represent some high aspirations and achievements. They’re trying to give fellow blacks the tools to dream and reach those things for themselves. The two defied the long odds and low expectations society set for them and now actively work to improve the chances and raise the bar for others. The paths forged by these men offer a road to success. They’re putting in place guideposts for new generations to follow in their footsteps.

Recently, Green and Davis sat down with the New Horizons. In separate interviews they discussed their own journey and the road map for setting more blacks on the path to the American Dream.

Michael Green

Responsibility and leadership came early for Michael Green. As the oldest of five kids whose single mother worked outside the house, he was often charged with the task of looking after his younger siblings. His mom, Katherine Green, worked in the Douglas County Hospital kitchens before getting on with the U.S. Postal Service, where she retired after 30-plus years. Sundays meant getting dressed for services and bible school at Salem Baptist Church. He remains in awe of what his mom did to take care of the family.

“My mother raised us kids as a single working mom,” he said. “A very stable person. We didn’t know what poor was. I mean, she provided for us. We didn’t have the best of everything but we always had a place to live and food on the table. She was always home when she wasn’t working. On Saturday mornings she’d always get up and cook us a big breakfast with eggs and pancakes and everything and it conditioned me so much there’s hardly a Saturday morning I don’t crave eggs.”

|