Archive

Closing installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An appreciation of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

Here is the closing installment from my 2004-2005 series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. In this and in the recently posted opening installment I try laying out the scope of achievements that distinguishes this group of athletes, the way that sports provided advancement opportunities for these individuals that may otherwise have eluded them, and the close-knit cultural and community bonds that enveloped the neighborhoods they grew up in. It was a pleasure doing the series and getting to meet legends Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers, et cetera. I learned a lot working on the project, mostly an appreciation for these athletes’ individual and collective achievements. You’ll find most every installment from the series on this blog, including profiles of the athletes and coaches I interviewed for the project. The remaining installments not posted yet soon will be.

Closing installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness,

An Appreciation of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Any consideration of Omaha’s inner city athletic renaissance from the 1950s through the 1970s must address how so many accomplished sports figures, including some genuine legends, sprang from such a small place over so short a span of time and why seemingly fewer premier athletes come out of the hood today. As with African-American urban centers elsewhere, Omaha’s inner city core saw black athletes come to the fore, like other minority groups did before them, in using sports as an outlet for self-expression and as a gateway to more opportunity.

As part of an ongoing OWR series exploring Omaha’s Black Sports Legends, this installment looks at the conditions and attitudes that once gave rise to a singular culture of athletic achievement here that is less prevalent in the current feel-good, anything-goes environment of plenty and World Wide Web connectivity.

The legends and fellow ex-jocks interviewed for this series mostly agree on the reasons why smaller numbers of youths these days possess the right stuff. It’s not so much a lack of athletic ability, observers say, but a matter of fewer kids willing to pay the price in an age when sports is not the only option for advancement. The contention is that, on average, kids are neither prepared nor inclined to make the commitment and sacrifice necessary to realize, much less pursue, their athletic potential when less demanding avenues to success abound.

“Kids today are changed — their attitudes about authority and everything else,” says Major League Baseball Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson, an Omaha Tech High grad who grew up in the late’40s-early ‘50s under the stern but steady hand of coaches like his older brother, Josh. “They’re like, I’m not going to let somebody tell me what to do, where we had no problem with that in our day.”

Gibson says coaches like Josh, a bona fide legend on the north side, used to be viewed as an extension of the family, serving, “first of all,” as “a father figure,” or as Clarence Mercer, a top Tech swimmer, puts it, as “a big brother,” providing discipline and direction to that era’s at-risk kids, many from broken homes.

Josh Gibson, along with other strong blacks working as coaches, physical education instructors and youth recreation directors in that era, including Marty Thomas, John Butler, Alice Wilson and Bob Rose, are recalled as superb leaders and builders of young people. All had a hand in shaping Omaha’s sports legends of the hood, but perhaps none more so than Gibson, who, from the 1940s until the 1960s, coached touring baseball-basketball teams out of the North Omaha Y. “Josh was instrumental in training most of these guys. He was into children, and into developing children. He carried a lot of respect. If you cursed or if you didn’t do what he wanted you to do or you didn’t make yourself a better person, than you couldn’t play for him,” says John Nared, a late ‘50s-early ’60s Central High-NU hoops star who played under Gibson on the High Y Monarchs and High Y Travelers. “He didn’t want you running around doing what bad kids did. When you came to the YMCA, you were darn near a model child because Josh knew your mother and father and he kept his finger on the pulse. When you got in trouble at the Y, you got in trouble at home.”

Old-timers note a sea change in the way youths are handled today, especially the lack of discipline that parents and coaches seem unwilling or unable to instill in kids. “You see young girls walking around with their stuff hanging out and boys bagging it with their pants around their ankles. In our time, there were certain things you had to do and it was enforced from your family right on down,” says Milton Moore, a track man at Central in the late ‘50s.

The biggest difference between then and now, says former three-sport Tech star and longtime North Omaha Boys Club coach Lonnie McIntosh, is the disconnected, permissive way youths grow up. Where, in the past, he says, kids could count on a parent or aunt or neighbor always being home, youths today are often on their own, in a latchkey home, isolated in their own little worlds of self-indulgence.

“What’s missing is a sense of family. People living on the same street may not even know each other. Parents may not know who their kids are running with. In our day, we all knew each other. We were a family. We would walk to school together. Although we competed hard against one another, we all pulled for one another. Our parents knew where we were,” McIntosh says.

“There were no discipline problems with young people in those days,” Mercer adds somewhat apocryphally.

Former Central athlete Jim Morrison says there isn’t the cohesion of the past. “The near north side was a community then. The word community means people are of one mind and one accord and they commune together.” “There’s no such thing as a black community anymore,” adds John Nared. “The black community is spread out. Kids are everywhere. Economics plays a part in this. A lot of mothers don’t have husbands and can’t afford to buy their kids the athletic shoes to play hoops or to send their kids to basketball camps. Some of the kids are selling drugs. They don’t want a future. We wanted to make something out of our lives because we didn’t want to disappoint our parents.”

The close communion of days gone by, says Nared, played out in many ways. Young blacks were encouraged to stay on track by an extended, informal support system operating in the hood. “The near north side was a very small community then…so small that everybody knew each other.” In what was the epitome of the it-takes-a-village-to-raise-a-child concept, he says the hood was a community within a community where everybody looked out for everybody else and where, decades before the Million Man March, strong black men took a hand in steering young black males. He fondly recalls a gallery of mentors along North 24th Street.

“Oh, we had a bunch of role models. John Butler, who ran the YMCA. Josh Gibson. Bob Gibson. Bob Boozer. Curtis Evans, who ran the Tuxedo Pool Hall. Hardy “Beans” Meeks, who ran the shoe shine parlor. Mr. (Marcus “Mac”) McGee and Mr. (James) Bailey who ran the Tuxedo Barbershop. All of these guys had influence in my life. All of ‘em. And it wasn’t just about sports. It was about developing me. Mr. Meeks gave a lot of us guys jobs. In the morning, when I’d come around the corner to go to school, these gentlemen would holler out the door, ‘You better go up there and learn something today.’ or ‘When you get done with school, come see me.’

“Let me give you an example. Curtis Evans, who ran the pool hall, would tell me to come by after school. ‘So, I’d…come by, and he’d have a pair of shoes to go to the shoe shine parlor and some shirts to go to the laundry, and he’d give me two dollars. Mr. Bailey used to give me free haircuts…just to talk. ‘How ya doin’ in school? You got some money in your pocket?’ I didn’t realize what they were doing until I got older. They were keeping me out of trouble. Giving me some lunch money so I could go to school and make something of myself. It was about developing young men. They took the time.”

Beyond shopkeepers, wise counsel came from Charles Washington, a reporter-activist with a big heart, and Bobby Fromkin, a flashy lawyer with a taste for the high life. Each sports buff befriended many athletes. Washington opened his humble home, thin wallet and expansive mind to everyone from Ron Boone to Johnny Rodgers, who says he “learned a lot from him about helping the community.” In hanging with Fromkin, Rodgers says he picked-up his sense of “style” and “class.”

Super athletes like Nared got special attention from these wise men who, following the African-American tradition of — “each one, to teach one” — recognized that if these young pups got good grades their athletic talent could take them far — maybe to college. In this way, sports held the promise of rich rewards. “The reason why most blacks in that era played sports is that in school then the counselors talked about what jobs were available for you and they were saying, ‘You’ll be a janitor,’ or something like that. There weren’t too many job opportunities for blacks. And so you started thinking about playing sports as a way to get to college and get a better job,” Nared says.

Growing up at a time when blacks were denied equal rights and afforded few chances, Bob Gibson and his crew saw athletics as a means to an end. “Oh, yeah, because otherwise you didn’t really have a lot to look forward to after you got out of school,” he says. “The only black people you knew of that went anywhere were athletes like Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson or entertainers.” Bob had to look no further than his older brother, Josh, to see how doors were closed to minorities. The holder of a master’s degree in education as well as a sterling reputation as a coach, Josh could still not get on with the Omaha Public Schools as a high school teacher-coach due to prevailing hiring policies then.

“Back in the ‘50s and early ‘60s the racial climate was such we had nothing else to really look forward to except to excel as black athletes,” says Marlin Briscoe, the Omaha South High School grad who made small college All-America at then-Omaha University and went on to be the NFL’s first black quarterback. “We were told, ‘You can’t do anything with your life other than work in the packing house.’ We grew up seeing on TV black people getting hosed down and clubbed and bitten by dogs and not being able to go to school. So, sports became a way to better ourselves and hopefully bypass the packing house and go to college.”

Besides, Nared, says, it wasn’t like there was much else for black youths to do. “Back when we were coming up we didn’t have computers, we didn’t have this, we didn’t have that. The only joy we could have was beating somebody’s ass in sports. One basketball would entertain 10 people. One football would entertain 22 people. It was very competitive, too. In the neighborhood, everybody had talent. We played every day, too. So, you honed in on your talents when you did it every day. That’s why we produced great athletes.”

With the advent of so many more activities and advantages, Gibson says contemporary blacks inhabit a far richer playing ground than he and his buddies ever had, leaving sports only one of many options. “In our time, if you wanted to get ahead and to get away from the ghetto or the projects, you were going to be an athlete, but I don’t know if that’s been the same since then. I think kids’ interests are other places now. There’s all kinds of other stuff to think about and there’s all kinds of other problems they have that we never had. They can do a lot of things that we couldn’t do back then or didn’t even think of doing.”

Milton Moore adds, “It used to be you couldn’t be everything you were, but you could be a baseball player or you could be a football player. Now, you can be anything you want to be. Kids have more opportunities, along with distractions.”

Ron Boone, an Omaha Tech grad who went to become the iron man of pro hoops by playing in all 1,041 games of his combined 13-year ABA-NBA career, finds irony in the fact that with the proliferation of strength training programs and basketball camps “the opportunities to become very good players are better now than they were for us back then,” yet there are fewer guys today who can “flat out play.” He says this seeming contradiction may be explained by less intense competition now than what he experienced back in the day, when everyone with an ounce of game wanted to show their stuff and use it as a steppingstone.

If not for the athletic scholarships they received, many black sports stars of the past would simply not have gone on to college because they were too poor to even try. In the case of Bob Gibson, his talent on the diamond and on the basketball court landed him at Creighton University, where Josh did his graduate work.

By the time Briscoe and company came along in the early ‘60s, they made role models of figures like Gibson and fellow Tech hoops star Bob Boozer, who parlayed their athletic talent into college educations and pro sports careers. “When Boozer went to Kansas State and Gibson to Creighton, that next generation — my generation — started thinking, If I can get good enough…I can get a scholarship to college so I can take care of my mom. That’s the way all of us thought, and it just so happened some of us had the ability to go to the next level.”

Young athletes of the inner city still use sports as an entry to college. The talent pool may or may not be what it was in urban Omaha’s heyday but, if not, than it’s likely because many kids have more than just sports to latch onto now, not because they can’t play. At inner city schools, blacks continue to make up a disproportionately high percentage of the starters in the two major team sports — football and basketball. The one major team sport that’s seen a huge drop-off in participation by blacks is baseball, a near extinct sport in urban America the past few decades due to the high cost of equipment, the lack of playing fields and the perception of the game as a slow, uncool, old-fashioned, tradition-bound bore.

Carl Wright, a football-track athlete at Tech in the ‘50s and a veteran youth coach with the Boys Club and North High, sees good and bad in the kids he still works with today. “There’s a big change in these kids now. I’ll tell a kid, ‘Take a lap,’ and he’ll go, ‘I don’t want to take no lap,’ and he’ll go home and not look back. I’ve seen kids with talent that can never get to practice on time, so I kick them off the team and it doesn’t mean anything to them. They’ve got so much talent, but they don’t exploit it. They don’t use it, and it doesn’t seem to bother them.”

On the other hand, he says, most kids still respond to discipline when it’s applied. “I know one thing, you can tell a kid, no, and he’ll respect you. You just tell him that word, when everybody else is telling him, yes, and they get to feeling, Well, he cares about me, and they start falling into place. There’s really some good kids out there, but they just need guidance. Tough love.”

Tough love. That was the old-school way. A strict training regimen, a heavy dose of fundamentals, a my-way-or-the-highway credo and a close-knit community looking out for kids’ best interests. It worked, too. It still works today, only kids now have more than sports to use as their avenue to success.

Related articles

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Hoops Legend John C. Johnson: Fierce Determination Tested by Repeated Run-Ins with the Law (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- One Peach of a Pitcher: Peaches James Leaves Enduring Legacy in the Circle as a Nebraska Softball Legend (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Great Migration Comes Home: Deep South Exiles Living in Omaha Participated in the Movement Author Isabel Wilkerson Writes About in Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Opening installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

Here is the opening installment from my 2004-2005 series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. Look for the closing installment in a separate post. In these two pieces I try laying out the scope of achievements that distinguishes this group of athletes, the way that sports provided advancement opportunities for these individuals that may otherwise have eluded them, and the close-knit cultural and community bonds that enveloped the neighborhoods they grew up in. It was a pleasure doing the series and getting to meet legends Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers, et cetera. I learned a lot working on the project, mostly an appreciation for these athletes’ individual and collective achievements. You’ll find most every installment from the series on this blog, including profiles of the athletes and coaches I interviewed for the project. The remaining installments not posted yet soon will be.

Opening installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness,

An exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Omaha’s African American community has produced a heritage rich in achievement across many fields, but none more dramatic than in sports, Despite a comparatively small populace, black Omaha rightly claims a legacy of athletic excellence in the form of legends who’ve achieved greatness at many levels, in a variety of sports, over many eras.

These athletes aren’t simply neighborhood or college legends – their legacies loom large. Each is a compelling story in the grand tale of Omaha’s inner city, both north and south. The list includes: Bob Gibson, a major league baseball Hall of Famer. Bob Boozer, a member of Olympic gold medal and NBA championship teams. NFL Hall of Famer Gale Sayers. Marlin Briscoe, the NFL’s first black quarterback. Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers. Pro hoops “iron man” Ron Boone. Champion wrestling coach Don Benning

“Some phenomenal athletic accomplishments have come out of here, and no one’s ever really tied it all together. It’s a huge story. Not only did these athletes come out of here and play, they lasted a long time and they made significant contributions to a diversity of college and professional sports,” said Briscoe, a Southside product. “I mean, per capita, there’s probably never been this many quality athletes to come out of one neighborhood.”

An astounding concentration of athletic prowess emerged in a few square miles roughly bounded north to south, from Ames Avenue to Lake Street, and east to west from about 16th to 36th. Across town, in south Omaha, a smaller but no less distinguished group came of age.

“You just had a wealth of talent then,” said Lonnie McIntosh, a teammate of Gibson and Boozer at Tech High.

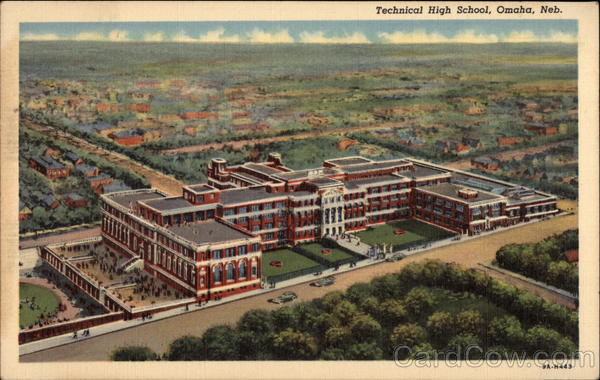

Many inner city athletes resided in public housing projects. Before school desegregation dispersed students citywide, blacks attended one of four public high schools – North, Tech, Central or South. It was a small world.

During a Golden Era from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s, all manner of brilliant talents, including future all-time greats, butted heads and rubbed shoulders on the same playing fields and courts of their youth, pushing each other to new heights. It was a time when youths competed in several sports instead of specializing in one.

“In those days, everybody did everything,” said McIntosh, who participated in football, basketball and track.

Many were friends, schoolmates and neighbors, often living within a few doors or blocks of each other. It was an insular, intense, tight-knit athletic community that formed a year-round training camp, proving ground and mutual admiration society all rolled into one.

“In the inner city, we basically marveled at each other’s abilities. There were a lot of great ballplayers. All the inner city athletes were always playing ball, all day long and all night long,” said Boozer, the best player not in the college hoops hall of fame. “Man, that was a breeding ground. We encouraged each other and rooted for each other. Some of the older athletes worked with young guys like me and showed us different techniques. It was all about making us better ballplayers.”

NFL legend Gale Sayers said, “No doubt about it, we fed off one another. We saw other people doing well and we wanted to do just as well.”

The older legends inspired legends-to-be like Briscoe.

“We’d hear great stories about these guys and their athletic abilities and as young players we wanted to step up to that level,” he said “They were older and successful, and as little kids we looked up to those guys and wanted to emulate them and be a part of the tradition and the reputation that goes with it.”

The impact of the older athletes on the youngsters was considerable.

“When Boozer went to Kansas State and Gibson to Creighton, that next generation – my generation – started thinking, ‘If I can get good enough, I can get a scholarship to college so I can take care of my mom‚’” Briscoe said. “That’s the way all of us thought, and it just so happened some of us had the ability to go to the next level.”

With that next level came a new sense of possibility for younger athletes.

“It got to the point where we didn’t think anything was impossible,” Johnny Rodgers said. “It was all possible. It was almost supposed to happen. We were like, If they did it, we can do it, too. We were all in this thing together.”

In the ’50s and ’60s, two storied tackle football games in the hood, the annual Turkey and Cold Bowls, were contested at Burdette Field over the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. Drawing players of all ages, they were no-pads, take-no-prisoners rumbles where adolescent prodigies like Gale Sayers and Johnny Rodgers competed against grown men in an athletic milieu rich with past, present and future stars.

“They let us play ball with them because we were good enough to play,” Rodgers said. “None of us were known nationally then. It really was gratifying as the years went on to see how guys went on and did something.”

When Rodgers gained national prominence, he sensed kids “got the same experience seeing me as I got seeing those legends.”

Among the early legends that Rodgers idolized was Bob Gibson. Gibson gives Omaha a special sports cachét. He’s the real thing — a major league baseball Hall of Famer, World Series hero and Cy Young Award winner. The former St. Louis Cardinal pitcher was among the most dominant hurlers, intense competitors and big game performers who ever played. Jim Morrison, a teammate on the High Y Monarchs coached by Bob’s brother, Josh, recalled how strong Gibson was.

“He threw so hard, we called it a radio ball. You couldn’t see it coming. You just heard it.”

Morrison said Gibson exhibited his famous ferocity early on.

“On the sideline, Bob could be sweet as honey, but when he got on the mound you were in big trouble. I don’t care who you were, you were in big trouble,” he said.

Gibson was also a gifted basketball player, as Boozer, a teammate for a short time at Tech and with the Travelers, attested.

“He was a finer basketball player than baseball player. He could play. He could get up and hang,” Boozer said.

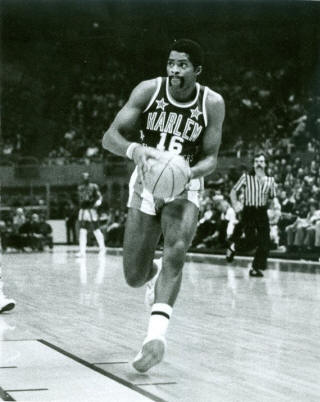

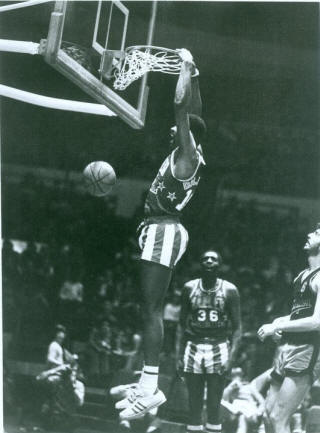

Gibson starred on the court for the hometown Creighton University Bluejays, then played with the Harlem Globetrotters for a year, but it was only after being denied a chance with the NBA that he made baseball his life. Gibson’s all-around athleticism and fierce game face was aided and abetted by his older brother, Josh, a formidable man and coach who groomed many of Omaha’s top athletes from the inner city.

Bob Gibson may be The Man, but Josh was a legend in his own time as a coach of touring youth teams (the Monarchs and Travelers) out of North Omaha’s YMCA.

“He was a terrific coach. If you were anything in athletics, you played for those teams under Josh Gibson,” Boozer said.

Others agreed.

“Josh was the one that guys like myself looked up to,” said Ron Boone. Jim Morrison said Josh had “the ability to elicit the best out of young potential stars. He started with the head down, not the body up. He taught you how to compete by teaching the fundamentals. It’s obvious it worked because his brother went on to be a great, great athlete.”

Josh Gibson is part of a long line of mentors, black and white, who strongly affected inner city athletes. Others included Logan Fontenelle rec center director Marty Thomas, the North O Y’s John Butler, Woodson Center director Alice Wilson, Bryant Center director John Nared and coaches Bob Rose of Howard Kennedy School, Neal Mosser of Tech, Frank Smagacz of Central, Cornie Collin of South, Carl Wright and Lonnie McIntosh of the North O Boys Club, Richard Nared and Co. with the Midwest Striders track program, Forest Roper with the Hawkettes hoops program, Petie Allen with the Omaha Softball Association, and Joe Edmonson of the Exploradories Wrestling Club. Each commanded respect, instilled discipline and taught basics.

Mosser, Tech’s fiery head hoops coach for much of the ‘50s and ‘60s, coached Boozer and Gibson along with such notables as Fred Hare, whom Boone calls “one of the finest high school basketball players you’d ever want to see,” Bill King and Joe Williams. A hard but fair man, Mosser defied bigoted fans and biased officials to play black athletes ahead of whites.

“Neal Mosser fought a tremendous battle for a lot of us minority kids,” McIntosh said. “He and Cornie Collin. At that time, you never had five black kids on the basketball court at the same time.”

But they did, including a famous 1954 Tech-South game when all 10 kids on the court were black.

“Their jobs were on the line, too,” McIntosh said of the two coaches.

Wherever they live, athletes will always hear about a real comer to the local scene. Like when Josh Gibson’s little brother, Bob, began making a name for himself in hoops.

The buzz was, “This kid can really jump, man,” Lonnie McIntosh recalled. “He had to duck his head to dunk.” But nobody could hang like Marion Hudson, an almost mythic-like figure from The Hood who excelled in soccer, baseball, football, basketball and track and field. Former Central High athlete Richard Nared said, “Marion was only 6’0, but he’d jump center, and go up and get it every time. The ref would say, ‘You’re jumping too quick,’ and Marion would respond, ‘No, you need to throw the ball higher.'”

Admirers and challengers go to look over or call out the young studs. Back in the day, the proving grounds for such showcases and showdowns included Kountze Park, Burdette Field, the North O YMCA, the Logan Fontenelle rec center, the Kellom Center and the Woodson Center. Later, the Bryant Center on North 24th became the place to play for anyone with game, Boone said.

“I mean, the who’s-who was there. We had teams from out west come down there to play. There was a lot of competition.”

Black Omaha flourished as a hot bed of talent in football, basketball, baseball and track and field. At a time when blacks had few options other than a high school degree and a minimum-wage job, and even fewer leisure opportunities, athletics provided an escape, an activity, a gateway. In this highly charged arena, youths proved themselves not by gang violence but through athletic competition. Blacks gravitated to sports as a way out and step up. Athletics were even as a mode of rebellion against a system that shackled them. Athletic success allowed minority athletes to say, oh, yes, I can.

“Back in the ‘50s and early ‘60s the racial climate was such we had nothing else to really look forward to except to excel as black athletes,” said Briscoe. “In that era, we didn’t get into sports with that pipe dream of being a professional athlete. Mainly, it was a rite of passage to respect and manhood. We were told, ‘You can’t do anything with your life other than work in the packing house.’ We grew up seeing on TV black people getting hosed down and clubbed and bitten by dogs and not being able to go to school. So sports became a way to better ourselves and hopefully bypass the packing house and go to college.”

Richard Nared, a former track standout at Central, said speed was the main barometer by which athletic ability was gauged.

“Mostly, all the guys had speed. You were chosen that way to play. The guys that were the best and fastest were picked first,” he said.

Toughness counted for something, too, but speed was always the separating factor.

“You had to be able to fight a little bit, too. But, yeah, you had to be fast. You were a second class citizen if you couldn’t run,” Bob Gibson said.

And second class wasn’t good in such a highly competitive community.

“The competition was so strong Bob Boozer did not make the starting five on the freshman basketball team I played on at Tech,” Jim Morrison said.

It was so strong that Gale Sayers was neither the fastest athlete at Central nor at home, owing to older brother Roger, an elite American sprinter who once beat The Human Bullet, Bob Hayes. Their brother, Ron, who played for the NFL’s San Diego Chargers, may also have been faster than Gale.

The competition was so strong that Ron Boone, who went on to a storied college and pro hoops career could not crack Tech’s starting lineup until a senior.

Bob Boozer, remembered today as a sweet-shooting, high-scoring, big-rebounding All-America power forward at Kansas State and a solid journeyman in the NBA, did not start out a polished player. But he holds the rare distinction of winning both Olympic gold as a member of the U.S. squad at the 1960 Rome Games, and an NBA championship ring as 6th man for the 1971 Milwaukee Bucks.

Boozer showed little promise early on. After a prodigious growth spurt of some six inches between his sophomore and junior years in high school, Boozer was an ungainly, timid giant.

“I couldn’t walk, chew gum and cross the street at the same time without tripping,” he said.

Hoping to take advantage of his new height, Boozer enlisted John Nared, a friend and star at arch-rival Central, and Lonnie McIntosh, a teammate at Tech, to help his coordination, conditioning, skills and toughness catch up to his height.

“Lonnie was always a physical fitness buff. He would work me out as far as strength and agility drills,” Boozer recalled. “And John was probably one of the finest athletes to ever come out of Omaha. He was a pure basketball player. John and I would go one-on-one. He was 6’3. Strong as a bull. I couldn’t take him in the paint. I had to do everything from a forward position. And, man, we used to have some battles.”

Boozer dominated Nebraska prep ball the next two years and, in college, led the KSU Wildcats to national glory. When Boozer prepared to enter the NBA with the Cincinnati Royals, he again called-on Nared’s help and credits their one-on-one tussles with teaching him how to play against smaller, quicker foes. The work paid off, too, as Boozer became a 20-point per game scorer and all-star with the Chicago Bulls.

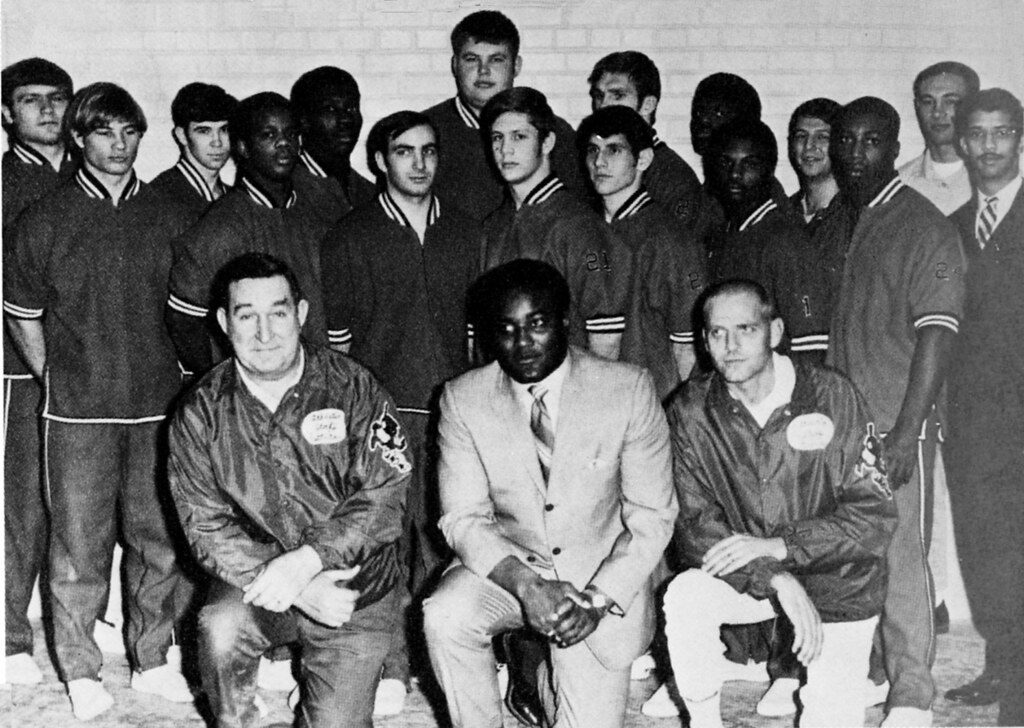

Around the time Boozer made a name for himself in the NBA, Don Benning took over then-Omaha U.’s lowly wrestling program. He was the first black head coach at a predominantly white university. Within a few years, Benning , a North High and UNO grad who competed in football and wrestling, built the program into the perennial power it remains today. He guided his 1969-70 squad to a national NAIA team championship, perhaps the first major team title won by a Nebraska college. His indomitable will led a diverse mix of student-athletes to success while his strong character steered them, in the face of racism, to a higher ground.

After turning down big-time coaching offers, Benning retired from athletics in his early 30s to embark on a career in educational administration with Omaha Public Schools, where he displayed the same leadership and integrity he did as a coach.

The Central High pipeline of prime-time running backs got its start with Roger and Gale Sayers. Of all the Eagle backs that followed, including Joe Orduna, Keith “End Zone” Jones, Leodis Flowers, Calvin Jones, Ahman Green and David Horne, none quite dazzled the way Gale Sayers did. He brandished unparalleled cutting ability as an All-American running back and kick returner at Kansas University and, later, for the Chicago Bears. As a pro, he earned Rookie of the Year, All-Pro and Hall of Fame honors.

Often overlooked was Gale’s older but smaller brother, Roger, perhaps the fastest man ever to come out of the state. For then-Omaha U. he was an explosive halfback-receiver-kick returner, setting several records that still stand, and a scorching sprinter on the track, winning national collegiate and international events. When injuries spoiled his Olympic bid and his size ruled out the NFL, he left athletics for a career in city government and business.

Ron Boone

Ron Boone went from being a short, skinny role player at Tech to a chiseled 6’2 star guard at Idaho State University, where his play brought him to the attention of pro scouts. Picking the brash, upstart ABA over the staid, traditional NBA, Boone established himself as an all-around gamer. He earned the title “iron man” for never missing a single contest in his combined 13-year ABA-NBA career that included a title with the Utah Stars. His endurance was no accident, either, but rather the result of an unprecedented work ethic he still takes great pride in.

Marlin Briscoe was already a pioneer when he made small college All-America as a black quarterback at mostly white Omaha U., but took his trailblazing to a new level as the NFL’s first black QB. Pulled from cornerback duty to assume the signal calling for the Denver Broncos in the last half of his 1968 rookie season, he played big. But the real story is how this consummate athlete responded when, after exhibiting the highly mobile, strong-armed style now standard for today’s black QBs, he never got another chance behind center. Traded to Buffalo, he made himself into a receiver and promptly made All-Pro. After a trade to Miami, he became a key contributor at wideout to the Dolphins two Super Bowl winning teams, including the perfect 17-0 club in 1972. His life after football has been a similar roller-coaster ride, but he’s adapted and survived.

Finally, there is the king of bling-bling, Johnny Rodgers, the flamboyant Nebraska All-American, Heisman Trophy winner and College Football Hall of Fame inductee. Voted Husker Player of the Century and still regarded as one of the most exciting, inventive broken field runners, Rodgers is seemingly all about style, not substance. Yet, in his quiet, private moments, he speaks humbly about the mysteries and burdens of his gift and the disappointment that injuries denied him a chance to strut his best stuff in the NFL.

Other, less famous sports figures had no less great an impact, from old-time football stars like Charles Bryant and Preston Love Jr., to more recent gridiron stars like Junior Bryant and Calvin Jones, right through Ahman Green. In 2003, Green, the former Nebraska All-American and current Green Bay Packers All-Pro, rushed for more yards, 1,883, in a single season, than all but a handful of backs in NFL history, shattering Packers rushing records along the way.

Hoops stars range from John Nared, Bill King, Fred Hare and Joe Williams in the ‘50s and ‘60s to Dennis Forrest, John C. Johnson, Kerry Trotter, Mike McGee, Ron Kellogg, Cedric Hunter, Erick Strickland, Andre Woolridge, Maurtice Ivy and Jessica Haynes in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s. After torrid prep careers, King, Nared, Hare and Williams had some college success. The others starred for Division I programs, except for Forrest, who starred at Division II UNO. Ex-NU star Strickland made the NBA, where he’s still active.

The prolific McGee, who set Class A scoring marks at North and topped the University of Michigan’s career scoring chart, played on one of Magic Johnson’s-led Lakers title teams in the ‘80s. Ivy made the WBA. Others, like Woolridge, played in Europe.

Multi-sport greats have included Marion Hudson, Roger Sayers and Mike Green from the ‘60s and Larry Station from the ‘70s, all of whom excelled in football. A Central grad, Hudson attended Dana College in Blair, Neb. where he bloomed into the most honored athlete in school history. He was a hoops star, a record-setting halfback and a premier sprinter, long-jumper and javelin thrower, once outscoring the entire Big Seven at the prestigious Drake Relays.

He was the Lincoln Journal Star’s 1956 State College Athlete of the Year.

Among the best prep track athletes ever are former Central sprinter Terry Williams, Boys Town distance runner Barney Cotton, Holy Name sprinter Mike Thompson, Creighton Prep sprinter/hurdler Randy Brooks and Central’s Ivy.

The elite wrestlers are led by the Olivers. Brothers Archie Ray, Roye and Marshall were state champs at Tech and collegiate All-Americans. Roye was an alternate on the ’84 U.S. Olympic wrestling team. The latest in this family mat dynasty is Archie Ray‚s son Chris, a Creighton Prep senior, who closed out a brilliant career with an unbeaten record and four state individual titles.

Joe Edmonson developed top wrestlers and leaders at his Exploradories Wrestling Club, now the Edmonson Youth Outreach Center. Tech’s Curlee Alexander became a four-time All-American and one-time national champ at UNO and the coach of seven state team championships, including one at Tech, where he coached the Oliver brothers, and the last six at North. And Prep’s Brauman Creighton became a two-time national champ for UNO.

A few black boxers from Omaha made their mark nationally. Lightweight prizefighter Joey Parks once fought a draw with champ Joe Brown. A transplanted Nebraskan via the Air Force, Harley Cooper was a two-time national Golden Gloves champion out of Omaha, first as a heavyweight in 1963 and then as a light heavyweight in 1964. He was slated for the 1964 U.S. Olympic Team as light heavyweight at the Tokyo Games and sparred with the likes of Joe Frazier, when, just before leaving for Japan, a congenital kidney condition got him scratched. Despite offers to turn pro, including an overture from boxing legend Henry Armstrong, Cooper opted to stay in the military. Lamont Kirkland was a hard-hitting terror during a light heavyweight amateur and pro middleweight career in the ’80s.

With the advent of Title IX, girls-women’s athletics took-off in the ‘70s, and top local athletes emerged. Omaha’s black female sports stars have included: Central High and Midland Lutheran College great Cheryl Brooks; Central High and NU basketball legend Maurtice Ivy, a Kodak All-America, WBA MVP and the founder-director of her own 3-on-3 Tournament of Champions; Ivy’s teammate at Central, Jessica Haynes, an impact player at San Diego State and a stint in the WNBA; Maurtice’s little sister, Mallery Ivy Higgs, the most decorated track athlete in Nebraska prep history with 14 gold medals; Northwest High record-setting sprinter Mikaela Perry; Bryan High and University of Arizona hoops star Rashea Bristol, who played pro ball; and NU softball pitching ace Peaches James, a top draftee for a new pro fastpitch league starting play this summer.

The stories of Omaha’s black sports legends contribute to a vital culture and history that demand preservation. This ongoing, 12-part series of profiles is a celebration of an inner city athletic lore that is second to none, and still growing.

Related articles

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Hoops Legend John C. Johnson: Fierce Determination Tested by Repeated Run-Ins with the Law (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- One Peach of a Pitcher: Peaches James Leaves Enduring Legacy in the Circle as a Nebraska Softball Legend (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

One Peach of a Pitcher: Peaches James Leaves Enduring Legacy in the Circle as a Nebraska Softball Legend

I earlier posted a 2004 story about black women athletes of distinction in Nebraska, and that reminded me of another story I did that year on Peaches James, a hard-throwing softball pitcher whose dominance in the circle helped establish a dynasty at Papillion-La Vista High School and helped lead the University of Nebraska softball program to great success, though short of its ultimate goal of winning the women’s College World Series. James was a good to very good college pitcher her first three years in Lincoln but elevated her game her senior season to become nothing short of great as she earned all sorts of team, conference, and national accolades. My story appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com) just as her collegiate career came to an end and just as she looked forward to playing professionally. Her pro career didn’t amount to much, but today she’s a fastpitch instructor with an elite sports academy in Illinois.

NOTE: While this story was not officially a part of my extensive 2004-2005 series on Omaha black sports legends, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, it appeared just before the start of that series, and so I count it in the mix. You can find most of the installments in that series on this blog, and I’ll soon be adding the remaining installments.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Nebraska softball pitching whiz Peaches James is the epitome of cool on the diamond between her tight braids, sleek shades, silver bling-bling adorned ears and silky smooth delivery of blazing rise balls. She strides the circle with the calm confidence you expect from the ace of the staff. Intense, yet loose, and in complete command out there.

The record-setting James is among the latest African-American athletes from Omaha who’ve made an enduring contribution to the area’s fat sports heritage. But she’s done it in a sport that, at the collegiate level, has had traditionally few black faces.

It’s no coincidence the Top 15 Lady Huskers enjoyed their finest season in a long time in what was their ace’s best year. NU wrapped up the regular season Big 12 title with a pair of one-run wins pitched by James over Texas A & M in early May. Two weekends ago, she got on a roll in the Big 12 tourney. She pitched a 2-1 complete game victory over Texas that saw her strike out 13 Longhorns and then topped that with a perfect game 7-0 win over Oklahoma. On May 15, she was in the circle for a 10-1 win over Baylor and later that same day she threw a 1-0 shutout, with 16 strikeouts, against Missouri to clinch the Huskers’ tourney title. With her four-game performance, she added conference tourney MVP to her Big 12 Pitcher of the Year honors. Then, she led her Huskers to the NCAA Region 5 championship round, posting a 6-0, 12-strikeout win over Leigh and bracketing two wins over Creighton amid a 2-0 loss to top-seed California. NU was eliminated Sunday with another 2-0 loss to the Bears — falling two wins short of the College World Series.

Even with her NU career ended, Peaches has already secured more softball in her future. Last December, she was a second round pick in the inaugural senior draft of the newly formed National Pro Fastpitch league, the latest attempt to market women’s softball. Selected by the Houston Thunder, now known as the Texas Thunder, James will be competing this summer with a who’s-who roster of former college and Olympic stars. NCAA rules prohibited her from negotiating and signing a contract until the season ended. Now that it has, she’s eager to get started. “I’m really excited,” she said. “It will be great competition.”

Then there’s a possible try for the 2008 USA Olympic team. Just like the pros, making the Olympic squad would require taking her game to “a whole different level,” she said. “When you have pitchers like Lisa Fernandez and Jenny Finch, they’re your top, elite athletes. To compete at that level you’ve got to be at the top of your game every game.” Can she? “I’d like to think so.” Cool. Peachy keen.

History repeated itself with James. She was a solid, at times smothering, starting pitcher her first two years of prep ball before going off into the stratosphere her senior season, when she shut down and almost always shut out her foes. Similarly, for NU, she established herself as an outstanding performer her freshman, sophomore and junior seasons, pitching well enough to earn first-team All-Big 12 honors all three years and first-team All-Midwest Region as a junior. Entering the 2004 season, she’d already been on the national Softball Player of the Year watch list and an invitee to the Olympic training center and she ranked among NU’s all-time leaders in wins, shutouts, strikeouts and innings pitched.

But, just like she did before, she ratcheted her game up another notch or two for her swan song, lowering her ERA by nearly half her career average, to 0.70, throwing her second collegiate no-hitter and setting NU single season records for most shutouts (18) and strikeouts (more than 300). Her 37 wins (versus 9 losses) are among the program’s best single season totals. She’s also first in career strikeouts (with more than 900) and second in career wins (98).

“I do see a lot of mirroring from her high school career,” Revelle said. “It seemed like every year in high school she made strides and then she made a leap her senior year. And I feel the same thing in this senior year for her. She’s had a great career for us but this is definitely her signature season.”

James explains her senior success this time around to having been there before. “I think what’s helped me is the experience I’ve gained from my freshman year in college to my senior year now. It’s about building confidence. It’s getting comfortable being out there and playing with your teammates. It’s building trust. It’s all those mental things that make you a better player.”

She first started developing a name for herself at Papillion-La Vista High School, whose dynasty of a softball program she helped maintain. Her prep career came in the middle of the school’s record nine straight state championships, a run of excellence unequaled in Nebraska prep history. But what James did her senior season elevated her and her team’s dominance to new heights. Almost literally unhittable the entire 1999-2000 campaign, she posted a remarkable 0.04 earned run average. In the space of that same season, she pitched 11 no-hitters, including five perfect games. It was the culmination of an unparalled two-year run in which she set about a dozen state records, including marks for most consecutive: wins (31); shut-outs (19); shut-out innings (162 1/3) and no earned runs allowed (257 2/3).

Her brilliance is all the more remarkable given that only six years earlier Mike Govig, her future prep coach, saw her at an indoor clinic where her wild throws soared up to the ceiling while her mother patiently sat on a bucket waiting, in vain, to catch one of those errant tosses. “I did not get it (pitching) right away. Balls would be flying everywhere,” James said. Govig recalls thinking the girl was hopeless.

What he didn’t know then was the size of her heart and strength of her will. With a lot of hard work, James made herself a pitcher the Monarchs rode to titles her sophomore year on. Her progress into a consummate hurler was so advanced that at a summer Topeka, Kansas tournament prior to her senior year she threw seven games in one day, winning six, en route to capping team title-tourney MVP honors.

“The title game got over at two o’clock in the morning, and her last inning was probably her strongest inning of the whole day,” Govig said. “You talk about a workhorse. The legend grew.”

Her dominance and endurance carried through her senior season. As her reputation grew, Govig said frustrated batters often got themselves out. “People were not able to step in the box with a whole lot of confidence. Half the battle was already won. They’d already lost…You could see it their body language.”

James also blossomed into a fine athlete. She competed in volleyball and track. On the diamond, she displayed versatility by playing second base her freshman year and posing the Monarchs best base stealing threat all four years. Govig rates her as one of the best athletes he’s ever coached, while NU head softball coach Rhonda Revelle flat out says, “I’ve not coached a better all-around athlete in this program. She’s physically powerful. She has so many tools.” James holds the best all-sport vertical jump in NU women’s athletics history at 30.5 inches.

The coaches say there’s never been another home-grown softball pitcher who’s carried her dominance from high school into college as James has. “She definitely stands alone,” Govig said. “She’s set the bar very high.”

The work ethic it took to come so far, so quickly, was instilled in James by her parents and coaches, whose preachings about the importance of practice she faithfully followed. “As I got older I had enough discipline to go pitch on my own or go work out on my own,” she said. “It’s like I wanted to do it on my own because I wanted to get better and I wanted to get good.”

Govig, who’s followed James career at NU, said the right-hander has it all. “Some pitchers might just be dominant with a rise ball, but she can throw a drop, a curve, a rise, a change. She can get you out in a bunch of different ways. Her ball movement is very extraordinary.”

Embracing the role of every day starter didn’t come easily for the placid James, whose magnanimous personality made it hard for her to stand out. “It was hard for me at first when we’d play and then I’d find out I was pitching again the next day and the other pitchers were not getting the ball, because I am the type of person that wants everybody to succeed,” she said. Her survival-of-the-fittest showing in Topeka went a long way towards changing her attitude. “Before that I would never have thought I’d be able to pitch and win that many games in one day,” she said. “I guess when you’re put in that situation and you’re put to the test, you really find out what you’re made of and you find out what you can and what you can’t do. It defines who you are and if you’re going to be tough enough to step up to a challenge and succeed at it. I got to where if my coaches said, ‘You’re pitching today,’ then I got in that mindset and that’s the only thing I could worry about if I was going to do my best for the team.”

Despite a solid start to her college career — when she posted 16-7, 22-9 and 23-13 records her first three years — James lacked the fire top pitchers need. “I was like a nice competitor, you know. I would compete, but I wasn’t like gritting my teeth in a I-will-not-lose kind of way. My teammates would always say I was too nice out there. You can be nice off the field, but when you’re on the field that’s the time you need to compete fiercely. And I think I’ve grown more into that to where I’m like: For me to lose, you’re going to have to beat me…I’m not going to beat myself and I’m not going to give into you…you’re going to have to be better than me. Yeah, I think that’s more the demeanor I do have now, and it’s really helped.”

Coach Revelle noticed. “I’ve used the term warrior for Peaches this year,” she said, “as I really think she’s taken on a warrior’s mentality, where she’s virtually unfazed by what goes on around he and just sticks to her game plan.” That nonplussed attitude extended to those times racial slurs were directed her way and to the strange looks she got as one of college softball’s few black pitchers.

Her strong, poised presence in the circle sent a clear message. “Ever since I’ve been a pitcher I’ve known you have to set the tone out there and have that presence,” she said. “You’re like an automatic leader being a pitcher. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve grown more into being a leader out there. I have to set the tone for the rest of my teammates because how I act and how I respond and how I am on the mound is how they’re going to act and respond.”

She also formed a tight relationship with her regular battery mate, catcher Brittney Yolo. “My catcher and our coaches have talked a lot about going two against one. That it’s not just me out there going against the batter, it’s me and my catcher going against that batter. And that, mentally, has helped a lot because I don’t feel like I have to do it myself. I have someone back there that’s going to help me. Especially with her behind the plate, I feel like I do own the batter and I do own part of that batter’s box, and they’re going to have to beat both of us.”

If the Huskers were to go all the way, James would have been the horse her team rode. Prior to the regional, she felt fully capable of carrying the load. “Oh, definitely. I will not be satisfied until the season’s over and we’ve been to the tournament,” she said. “We haven’t been there since my sophomore year, so that’s definitely a goal of mine, and the only way to get there is to keep working and to keep getting better. I can’t be content with anything.” Her coach, too, envisioned Peaches bringing the team all the way home. “She’s been a thoroughbred for us, and we can ride her until the last out of the College World Series, if we make it that far. I think she’s strong enough mentally and physically to endure that,” Revelle said before the start of the regional.

After coming up short, James simply said, “It’s hard.” Although not hit hard by California in the regional losses that ended NU’s season, James, who threw nearly 40 innings in two days, said, “I think physically I wasn’t at my sharpest but…I was giving whatever I had.” Revelle said it’s that kind of gutsy effort that made working with James “a tremendous ride for this coach,” adding: “I’ve never had a pitcher trust me so much. She is a tremendous athlete in her own right, but when you can trust the pitches that are being called and work together like that…Well, if I never have that again, I know I’ve had it once.”

This Peach of a Pitcher is finished at NU, but her legend will long live on there.

Related articles

- In twist of fate, Texas pitcher ties softball’s second-best single game homer mark (sports.yahoo.com)

- USA Softball Says Goodbye To a Legend: Jennie Finch to Retire in August (bleacherreport.com)

Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Gender equity got a major boost in 1972 when Congress passed Title IX legislation. Enacted in 1976, the law made it a crime for any educational institution receiving federal money to deny females the same rights as males, including in the field of athletic competition. The effects of Title IX have been far-reaching.

Since Title IX’s passage, female participation in interscholastic-intercollegiate sports has grown from a few hundred thousand annually to millions, U.S. Department of Education figures show. Once rare, female athletic scholarships are now proportionally the same as men’s. The amazing growth in female athletics — from the explosion of girls softball, soccer, swimming, track, volleyball and basketball programs to the birth of professional leagues to the capturing of Olympic gold medals — can be traced to Title IX. The legislation didn’t so much create great female athletes as legitimize them and provide an equal playing ground. It’s in this context Omaha’s black female athletes emerged on a broader stage than before.

Cheryl Brooks-Brown came along when fledgling athletic programs for girls were just evolving in the post-Title IX era. In local hoops circles, she was known for being a bona fide player. She got her game competing with boys on the courts near her home at 25th and Evans and with the Y-based Hawkettes, a select Amateur Athletic Union touring program for school-age girls founded and coached by the late Forrest Roper.

“I guess the ultimate complement for a girl is when you’re told, ‘You play like a guy,’ and I got that quite often,” she said. “I think I was a player that was before my time.” Wider recognition eluded her in an era of scant media exposure and awards for girls athletics. “That’s just the way it was,” she said.

For decades, Nebraska girls hoops was confined to intramural, club or AAU play. In the early ‘70s, the Hawkettes’ Audrey and Kay Boone, sisters of pro legend Ron Boone, were among the first local women to land athletic scholarships — to Federal City College in Washington, D.C. and John F. Kennedy College in Wahoo, Neb., respectively. When, in the mid-’70s, girls hoops was made a prep pilot program, Brooks got to compete her senior year (‘74-’75) for Omaha Central. In a nine-game season, she scored 20-plus points a game for the Eagles. It wasn’t until 1977 the Nebraska School Activities Association sanctioned full girls state championship play.

Brooks got two in-state offers — from UNO and Midland Lutheran College (Fremont, Neb.) She became the first black female to play at Midland, which competed then in the AIAW. Small college town life for a black woman in a sea of white faces presented “growing pains” for her, just as women’s athletics faced its own challenges. For example, she recalls the women’s team having to defer to the men’s team by practicing in the auxiliary gym. “Today, it’s much better, but athletics is still a male-dominated field. The battle’s still on,” she said.

An impact player ranking eighth all-time in scoring at Midland with 1,448 points, Brooks led the Warriors in nine individual categories as a sophomore and earned acclaim as one of the region’s best small college players as a junior. She led the Warriors to a 100-19 record over four years, including a berth in the ‘78 AIAW post-season tourney. She was selected to try out for a U.S. national Olympic qualifying team.

Her coach at Midland, Joanne Bracker, said the 5’9 guard’s “strength was her penetration to the basket. She was very offensive-minded. She had the ability to see the court extremely well. She was probably as good a passer as scorer. She would be competitive in today’s game because of her intense love and appreciation for the game and her understanding of the game. She’s a basketball junkie.”

After college, Brooks coached at Central, but her playing was strictly limited to recreational ball, as women’s pro hoops was still a decade away. The elementary ed grad has taught in the Omaha and Chicago public schools and was an adoption caseworker with the state of Illinois. She’s now back in Omaha, on disability leave, awaiting a kidney transplant. She’s done some recent coaching at the North Omaha Boys and Girls Club and continues working as a personal coach for a promising Omaha Benson player she hopes lands a scholarship, an easier task today than when she played.

“When I coach kids I tell them, ‘You don’t know how good you have it with all the opportunities you have.’ It’s unbelievable.”

By the time Brooks left Midland, a new crop of girl stars arrived, led by Central’s Maurtice Ivy and Jessica Haynes, both of whom were premiere prep and collegiate players. At the head of the class is Ivy, arguably the best female player ever to come out of Nebraska. Her credits include: vying for spots on the U.S. Olympic squad; leading the Nebraska women’s program out of the cellar en route to topping its all-time scoring charts; starring in pro ball in Europe and America; anchoring national title Hoop-It-Up teams; and directing her own 3-on-3 tourney.

For inspiration, Maurtice looked to Cheryl Brooks, whom she followed into the Hawkettes and at Central. A 5’9 swing player, Maurtice combined with Haynes, a 6’0 all-court flash, in leading the Hawkettes to high national age-group rankings and the Eagles to two straight state titles.

From more than 250 college scholarship offers, Ivy selected then-lowly NU. The high-scoring, tough-rebounding playmaker became the first Lady Husker to top 2,000 points while being named first-team all Big 8 her final three years. She closed out a stunning collegiate career with Kodak All-America and Conference Player of the Year honors. As a senior, in 1987-88, she capped NU’s turnaround by leading it to its first NCAA tournament appearance.

Great players are born and made. Ivy earned her chops going head-to-head with boys.

“They were the ones that pushed me. They were the ones that made me,” she said. Her proving grounds were the cement courts at Fontenelle Park, across the street from her childhood home. There, she hooped it up with boys her own age, but didn’t really arrive until the older guys acknowledged her.

“They wouldn’t let me play for years. I had something to prove to them. Then, eventually, as my game improved…I proved it. The fellas were yelling my name to come across the street to the park. Once I got respect from the fellas, I knew I was there.”

Off the playground, her hard court schooling came via two men — the Hawkettes’ Forrest Roper, whom she calls “by far the best coach that ever coached me,” and her father, Tom, a former jock and youth sports coach who coached her in football. “I played middle linebacker for five years with my dad’s Gate City Steelers team,” she said. “He didn’t start me. I had to earn everything I got.” When not on the sidelines, “Pops” was courtside or trackside giving her “pointers and tips.”

Despite also competing in softball and track, basketball was IT. “That’s all I did — from the crack of dawn till the street lights came on,” Maurtice said. “That’s when we had to be inside. That was our clock.” The court was the place she felt most complete. “That’s where I found my peace. I was happy when I was out there. That’s what, as a child, brought me joy,” she added.

Her prowess on the court made her a star but her low-key personality and workmanlike approach tamped down any raging ego or showboat persona.

“I may have expressed myself out there, but I never wanted to tear anybody down,” she said. “I’ve always been pretty grounded. I expressed myself as a fighter…a warrior…a winner…a competitor. I had a blue collar work ethic out there. I did whatever I needed to do to get the W.”

The fire to win that raged inside was stoked by the heat of competition she braved every day. “I grew up around a lot of competitive people and it just challenged me to want to be a complete basketball player. I had people challenging me all the time and, so, either you sink or swim.”

Steeled early-on in the rigors of top-flight competition, Maurtice blossomed into a hoops prodigy. So rapid was her development that, at only 15, she made the U.S. Olympics Festival team and, at 17, she was invited to the 1984 Olympics tryouts in Colorado Springs. She was again invited to the tryouts in ‘88. Although failing in both bids to make the Olympics squad, she regards it as “a wonderful experience.”

“Still hungry for the game” after college, she pursued pro ball, playing two years in Denmark before joining the WBA’s Nebraska Express. In a five-year WBA stint, she twice won league MVP honors and led the Express to the league title in 1996. While her pro career unfolded before the women’s game reached a new level with the WNBA, she’s proud of her career. “I do think I’ve been a pioneer for women’s basketball. I’m always flattered when they compare players coming up now to me.”

Since retiring from the game, Ivy’s remained involved in the community as a mentor, YMCA program director, Head Start administrator and director of her own 3-on-3 Tournament of Champions. She’s also pursuing her master’s degree.

The hoops journey of the former Jessica Haynes (now Jackson) mirrored that of Maurtice Ivy’s before some detours took her away from the game, only to have her make a dramatic comeback. From the time she began playing at age six, she often went to great lengths to play, whether walking through snow drifts to the YMCA or sneaking into the boys club.

“I can honestly say basketball was my first love,” she said. “I’d wake up and I couldn’t wait to get to the gym.”

Another product of the Hawkettes program, she got additional schooling in the game from the boys and men she played with in and out of her own hoops-rich family. Her cousins include former ABA-NBA star Ron Boone and his son Jaron, a former NU and European star.

She recalls her uncles toughening her up in pickup games in which they routinely knocked her down and elbowed her in the ribs, all part of “getting her ready” for the next level. She tagged along with Ivy to the parks, where they found respect from the fellas.

“When they would choose us over some of the other guys to play with them, that was an honor. We were kind of like the pioneers” for women’s hoops,” said Jackson, who dunked by her late teens, although never in a game. LIke Ivy, Jackson was considered among America’s elite women’s players and was selected along with her to compete in the Olympic Sports Festival.

Originally intending to join Ivy at NU, Jackson opted instead for San Diego State University, where she was a first-team all-conference pick in 1986-87. “My strengths were speed and quickness. I was a slasher. I loved to go to the cup,” she said. Haynes, who played at the top of the Aztecs’ 1-3-1 zone, was a ball-hawk defender and fierce rebounder. Despite playing only three seasons, she ranks among the school’s career leaders in points, rebounds, steals and blocks.

Her career was cut short, she said, when harassment allegations she made against a professor were ignored by her coach and, rather than stay in what she felt was an unsupportive atmosphere, she left. She moved with her then-boyfriend to Colorado Springs, where he was stationed in the Air Force.

After the couple married and started a family, any thoughts of using the one year of eligibility she had left faded. But her love for the game didn’t. She played recreational ball and then, in the mid-’90s, earned a late season roster spot with the Portland Power pro franchise of the ABL. That led to a tryout with the L.A. Sparks of the newly formed WNBA. She got cut, but soon landed with the league’s Utah Stars, for whom she wore the same number, 24, as her famous cousin, Ron Boone, who’d played with the Utah Jazz.

To her delight, her game hadn’t eroded in that long layoff from top competition. “It came right back.” When a groin injury sidelined her midseason, she ended up returning to her family. Her last fling with the game found her all set to go play for an Italian pro team. Only she’d have to leave her family behind.

“I was at the airport with my passport and visa. My bags were checked. The reservation agent was searching for a seat for me. And then I looked at my daughter, who had tears streaming down her face, and all of a sudden I said, ‘I can’t go.’ I didn’t. I’m very family-oriented and I really feel in my heart I made the right decision,” she said.

Today, Jackson is the youth sports director at the South Omaha YMCA, where she coaches her daughter’s team, and a voluntary assistant coach at Central High. She hopes to coach at the next level.

In the annals of Nebraska prep track athletes, one name stands alone — Mallery Ivy (Higgs). The younger sister of Maurtice Ivy, Mallery dominated the sprints in the early ‘90s, winning more all-class gold medals — 14 — than anyone else in state track meet history. Her run of success was only slowed when injuries befell her at powerhouse Tennesee. So dominant was Mallery that she never lost an individual high school race she entered. She set numerous invitational and state records. She holds the fastest time in Nebraska history in the 100. She ran on the 400-meter relay team that owns the state’s best mark. The Ivys form an amazing sister act.

“There’s not a lot of siblings that have done what we’ve done,” Mallery said.

“I think there was a mutual respect we had for one another. Mallery is one of the best track athletes to come out of this state,” Maurtice said. “I encouraged her. And the reason I got in track is that Mallery started having some success. I was like, Wow, she’s bringing in way more medals than I am in basketball. And she got in basketball because of me. We didn’t really compete one-on-one. I think we had a couple races, but, to be totally honest, she probably would have beat me, especially in the 100 and 200.”

Three years younger than her sister, Mallery used Maurtice as a measuring stick for her own progress.

“Well, I was the baby, so I always had to follow on behind her footsteps. She was somewhat my drive,” Mallery said, “because if she excelled, I had to excell. If she did it, I had to do it, and do it better. There was not like a rivalry with us. We always wanted each other to do the best we could. We always had each other’s back. But because she held track records, I still had to compete with her times…and I had to beat them.”

For extra incentive, Maurtice made challenge bets with Mallery to best her marks. One year, a steak dinner rode on the outcome. “I was down to my last race, the 400, and she held the record…and I broke that record,” Mallery said. “She still owes me that steak.”

As with Maurtice, Tom Ivy was there for Mallery. He challenged her to races and put her through her paces. She further refined her running with the Midwest Striders, a youth track program that’s turned out many award-winning athletes.

“He was the one who wouldn’t let us let up,” Mallery said of their father. “If he would show up at practice, he would make comments like, ‘You gotta dig down and fight,’ and that made you fight a little bit harder. We couldn’t perform until we heard that voice, and then we were fine. I remember at one of my state meets being in the blocks and thinking, Oh, my God, my daddy’s not here, and then literally hearing his voice, ‘Let’s go ladies,’ just before the start. And I was like, All right, I’m cool.”

Mallery dug the deepest her final two meets when, not long before districts she came down with chicken pox. Badly weakened after sitting out two weeks, she barely qualified for state. A grueling training schedule for state paid off when she gutted out four victories in winning four all-class gold medals.

The Ivy sisters fed off the motivation their family provided. “They always reinforced we could do anything we put our minds to,” Mallery said. “They knew that whatever anybody told us we couldn’t do, we would do it.”

Like her sister, Mallery is community-oriented, only in Atlanta, where she lives with her husband and their two children. She works in an Emory University health care program aimed at preventing HIV, STDS and unplanned pregnancies and contracts with the country to counsel at-risk youths. The owner of her own interior design business, she’s back in school going for an interior design degree.

Many more women athletes of note have made an impact. Just in track and field alone there’s been Juanita Orduna and Kim Sims as well as Angee Henry, the state record holder in the 200-meter dash (24.52 seconds) and Mikaela Perry, the state record holder in the 400-meter dash (55.36 seconds). In hoops, there’s been the Hawkettes’ Deborah Lee and Deborah Bristol and Bryan’s Rita Ramsey, Annie Neal, Marlene Clark and Gail Swanson. More recently, there’s Bryan’s Reshea Bristol and Niokia Toussaint.

Point guard Bristol starred at the University of Arizona. As an All-Pac 10 senior she averaged 15.6 points and 7.5 assists. She led the league in assists and was second in steals. She ranks among UA’s all-time leaders in 12 categories. Drafted by the WNBA’s Charlotte Sting, Bristol later played in Europe.

Now, there’s softball standout Peaches James. The former Papillion-La Vista pitching phenom just concluded her record-setting Husker career and brilliant season-ending senior run by leading NU within two wins of the College World Series. She’s now playing professionally for the Texas Thunder in the newly formed National Pro Fastpitch League.

UPDATE: Since this article appeared more than a decade ago many more black female athletes of distinction have emerged in Nebraska, including Yvonne Turner, Dominique Kelley, Dana Elsasser, Mayme Conroy, Chelsea Mason, Brianna Rollerson. When my article was published the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame didn’t exist and now all of the women featured in the story are inductees there in addition to various school athletic halls of fame.

Related articles

- President Obama Talks Title IX (whitehouse.gov)

- From ESPN’s celebration of Title IX’s 40th: (womenshoopsblog.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From My Series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Gender Equity in Sports Has Come a Long Way, Baby; Activists-Advocates Who Fought for Change See Progress and the Need for More (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Lisa Leslie: The First Daughter of Title IX (huffingtonpost.com)

- As Title IX turns 40, legacy goes beyond numbers (cnsnews.com)

Making the case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame

When I wrote this piece several years ago the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame was a concept, not a reality, but I am happy to report that much of its vision has been realized. The men behind the hall, Ernie Britt and Robert Faulkner, know better than most that the state has produced and been a proving ground for an impressive gallery of accomplished black athletes for the better part of a century but that little formal recognition existed commemorating their accomplishments. Britt and Faulkner thought the time long overdue to organize a hall that gives these high achievers a permanent place of honor, particularly when many African-American youths today do not know about these greats and could draw inspiration from them. The founders also wanted to make the hall a vehicle for honoring top black prep athletes of today and for showcasing their talents. The hall’s early inductees include figures whose names are familiar to anyone, anywhere with more than a passing knowledge of sports history: Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers. They are all Omaha natives. But the hall is open to any black athlete, male or female, who made their mark in Nebraska, even if they just went to school here or played professionally here. Thus, this expanded pool of honorees encompasses figures like Bob Brown, Paul Silas, Charlie Green, Nate Archibald, Mike Rozier, Will Shields, and Tommy Frazier. There have been several induction classes by now and I must admit that each year there’s someone I didn’t know about before or had forgotten about, and that’s why the organization and its recogniton is so important – it educates the public about individuals deserving our attention. Britt and Faulkner, by the way, are inducted members of the hall themselves: the former as an athlete and the latter as a coach.

Making the case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Robert Faulkner feels it’s a shameful thing African American visitors to Omaha, much less area residents, can barely point to a single venue where local black achievements hold a place of honor. As the native Omahan is quick to note, the black community here can claim many accomplished individuals as its own. These figures encompass the breadth of human endeavor. But perhaps none are more impressive than the athletic greats who excelled in and out of Omaha’s inner city.

“What do you have for some of the greatest athletes that have ever walked the playing fields or the courts? Where can you see them up on a pedestal? There is nothing,” Faulkner said. “You’re talking about some of the greatest athletes in the world right from here,” said his lifelong friend Ernie Britt III, who rattled off the names Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlon Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers and Ahman Green as a sampling of Omaha’s black athletic progeny.

The distinguished list grows larger when you include area coaches (Don Benning at UNO) and talents who came to coach (Willis Reed at Creighton) or compete (Mike Rozier at Nebraska, Nate Archibald with the Kansas City/Omaha Kings, etc.).

All of this is why Faulkner and Britt recently formed the Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (NBSHF). The grassroots non-profit is a hall of fame in name only thus far, but that doesn’t stop these former athletes from sharing their vision for the real thing — a brick-and-mortar hall where folks can learn a history otherwise absent.

“It’s about remembering and promoting legacy and culture,” Faulkner said. “Our kids need to realize there are people they can look up to. There are people we looked up to. And these heroes…can live on. In our community pur kids don’t have those kinds of heroes because they’re never promoted anymore. They’re forgotten about. None of their exploits outside athletics is publicized. If they didn’t reach the highest levels in sport, then even their athletic exploits fade.”

He and Britt maintain there’s a serious disconnect between today’s black youths and the local athletic legends that could serve as role models. They sense even young athletes don’t know the greats who preceded them.

“Right now you walk into any school or onto any playground and go up to the finest athlete and throw out those names to him or her, and they don’t know what you’re talking about,” Faulkner said. “They don’t know who Bob Boozer is, and that’s the best basketball player ever from here. An all-state and all-American, an Olympic gold medalist, a first-round draft choice, an NBA champion.” They don’t even know who Johnny Rodgers is, and he’s a Heisman Trophy winner.