Archive

Creative couple: Bob and Connie Spittler and their shared creative life 60 years in the making

A lot of you know me as a frequent and longtime contributor with The Reader, for whom I’ve written more than a thousand stories since 1996, including hundreds of cover pieces. Beyond The Reader, I am fortunate to own extended relationships with several other publications. I was a major contributor to the Jewish Press for well over a decade. My tenures with Omaha Magazine and Metro Magazine are both more than a decade old now. But perhaps my longest-lived contributor relationship has been with the New Horizons, a monthly newspaper published by the Eastern Nebraska Office on Aging. Editor Jeff Reinhardt and I are committed to positive depictions of aging that illustrate in words and images the active, engaged lifestyles of people of a certain age. Older adult living doesn’t need to follow any of the outdated prescriptions that once had folks at retirement age slowing down to a crawl and more or less retreating from life. That’s not at all how the people we profile approach the second or third acts of their lives. No, our subjects are out doing things, working, creating, traveling, making a difference. My latest profile subjects for the Horizons, Bob and Connie Spittler, are perfect examples. They are in their 80s and still living the active, creative lives that have always driven their personal and professional pursuits. He makes still and moving images. He pilots planes. She writes essays, short stories and books. They travel. They enjoy nature. Sometimes they combine their images and words together in book projects. Bob and Connie are the cover subjects in the January 2016 issue. They join a growing list of folks I’ve profiled for the Horizons who embody such precepts of health aging as keeping your mind occupied, doing what you enjoy, following youe passion, cultivating new interests and discovering new things. The Spittlers are also in a long line of dynamic older couples I’ve profiled – Jose and Linda Garcia, Vic Gutman and Roberta Wilhelm, Josie Metal-Corbin and David Corbin, Ben and Freddie Gray. You can find many of my Horizons stories on my blog, Leo Adam Biga’s My Inside Stories at leoadambiga.com.

NOTE: ©Photos by Jeff Reinhardt, New Horizons Editor, unless otherwise indicated.

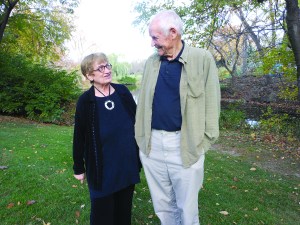

Bob and Connie Spittler outside their Brook Hollow home

Creative couple: Bob and Connie Spittler and their shared creative life 60 years in the making

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the January 2016 issue of the New Horizons

Once a creative, always a creative.

That’s how 80-something-year-olds Bob and Connie Spittler have rolled producing creative projects alone or together for six decades. Their work spans television commercials, industrial films, slideshows and books.

Bob, a photographer and filmmaker, these days experiments making art photos. Connie, a veteran scriptwriter, is now an accomplished essayist, short story writer and novelist. Her new novel, the tongue-in-cheek titled The Erotica Book Club for Nice Ladies, has found a receptive enough audience she’s writing a sequel. The book is published by Omaha author-publisher Kira Gale and her River Junction Press.

This past summer Bob and Connie hit the highway for a five-state book tour. Their stops included signings at the American Library Association Conference in San Francisco and the Tattered Cover in Denver. Following an intimate reading at a Berkeley, Calif. couple’s home she and Bob stayed the night. It harkened back to the RV road trips they made with their four kids.

On social media she termed the tour “an author’s dream.” It was especially gratifying given Bob endured a heart angioplasty and stent earlier in 2015.

Connie was also an invited panelist at an Austin, Texas literary event.

“All in all, an unforgettable year of healing, friendship, interesting places and great people,” she wrote in a card to family and friends.

Sharing a love for the outdoors, the Soittlers have applied their respective talents to splendid nature books. The Desert Eternal celebrates the ecosystem surrounding the home they shared in the foothills of the Catalina Mountains in Arizona, where they “retired” after years running their own Omaha film production biz

“When we want down to Tucson we weren’t going to be working together. We were just going to do our own thing,” she says. “We’ve always been able to kind of follow what we want to do. So I started writing literary things and he was out taking pictures. I had a lumpectomy and the day I came home I’m looking out at the Catalina Mountains and I thought, you know it’s strange Bob and I both think we’re doing our own thing when we’re doing the same thing, we’re just each doing it in our own way. We were both doing the desert.

“We lived between two washes the coyotes and other wildlife came through. I had seven weeks of radiation and I had the idea of putting our work together. I downloaded all my essays on the desert and every morning before radiation I’d go into his office and together we’d look through his photo archive for images he’d taken that matched the words I’d written. Well, by the time we got to the end we had 114 photos – enough for a book. Bob formatted it. It came back (from the printer) the day my radiation finished. It was just this cycle.”

Another of their books, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, documents the wild-in-the-city sanctuary around the southwest Omaha home they’ve lived in since 2010, when they returned from their Arizona idyll. Their home in the gated Sleepy Hollow neighborhood abuts four interconnected ponds that serve as habitat for feathered and furry creatures. The inspiration the couple finds in that natural splendor gets expressed in her words and his images.

“Words and images are perfect for each other,” Connie says by way of explaining what makes her and Bob such an intuitive match.

The couple met at Creighton University in the early 1950s. They studied communications and worked on campus radio, television, theater productions together. He was from the big city. She was from a small town, But they hit it off and haven’t stopped collaborating since.

The couple’s original office, ©Bob Spittler

Her writerly roots

The former Connie Kostel grew up in South Dakota. This avid reader practically devoured her entire hometown library.

Connie developed an affection for great women writers. “I love Emily Dickinson. Her poems are short and kind of pithy. She always has one thought in there that just kind of sticks with you.” Other favorites include Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Christina Rossetti, Jane Austen.

“I like a lot of classics.”

Terry Tempest Williams is a contemporary favorite.

Success in school got her thinking she might pursue writing.

“I think it was in the sixth grade I won an essay competition. It had to be on the topic of how we increased production on our family flax farm. Well, there were some farm kids in my grade but I don’t think anybody grew flax. My father was a funeral director. But I got the encyclopedia and I found out some facts about flax and I wrote an essay and I won. I think I got $25 or something. i mean it was like, Wow, I think I should be a writer. That sparked my interest.”

She attended the Benedictine liberal arts Mount Marty College in Yankton, S.D., a then-junior college for girls.

“I got a scholarship there. I was interested in writing and I was going to have to transfer anyway and I began to see radio and TV as one way maybe I could make a living writing rather than writing short stories and novels and so forth. So I decided to do that. My parents researched it out and found Creighton University for me, It had one of the few programs with television, radio and advertising,”

His Army detour

Meanwhile, Bob graduated from Omaha Creighton Prep before getting drafted into the U.S. Army. In between, he earned his private pilot’s license, the start of a lifelong affair with flying that’s seen him own and pilot several planes he’s utilized for both work and pleasure. Prior to the Army he began fooling around with a camera – a Brownie.

He recently put together a small book for his family about his wartime stint in Korea. He had no designs on doing anything with photography when he began documenting that experience.

“Everybody bought a camera over there and I bought an Argus C3. I just got interested in taking pictures for something to do. I learned how to use it and I just took a lot of pictures. I didn’t think it was going anywhere. It was just a hobby, you know.”

But those early photos show a keen eye for composition. He was, in short, a natural. The book he did years later, titled My Korea 1952 to 1953, gives a personal glimpse of life in the service amidst that unfamiliar culture and forbidding environment.

The Army assigned Spittler to intelligence work.

“My specialty was artillery but I was put in what they called G2 Air (part of Corps Intelligence). I went to a school in Japan. Back in Korea I coordinated the Air Force with the artillery in the CORPS front.”

Spittler relied on wall maps and tele-typed intel to schedule flights by Air Force photo-reconnaissance planes. “When I first arrived P-51 Mustangs were the planes used. Then after about six months they shifted to the F-80 Shooting Star,” he writes. “In winter a little pot-bellied kerosene stove warmed our tent. At night it had to be turned off and lighting it on a cold morning, below zero, was painful, It took 10 minutes before it even thought about giving heat.”

The closest he came to action was when a Greek mortar platoon on the other side of a river running past the American camp fired shells into a nearby hill, causing the GIs to scramble for cover.

Though he didn’t pilot any aircraft there he did find ways to feed his flying fix.

He writes, “Since my job was using radio contact with reconnaissance flights every day I became ‘talking friendly’ with some of the pilots. One of them agreed to give me a jet ride…”

Bob Spittler

That ride was contingent on Spittler making his way some distance to where the sound-breaking aircraft were based. “Come hell or high water I wasn’t going to pass up that offer,” he writes. With no jeep available, he hitchhiked his way southwest of Seoul and got his coveted ride in a T-33. From 33,000 feet he sighted the “double bend’ of the Imjin River pilots used as a rendezvous landmark – something he’d heard them often reference in radio chatter.

At Spittler’s urging the pilot did some loops. Aware his guest was a flier himself the pilot let Spittler put the jet into a roll. But before he could complete the pull out the pilot took over when Spittler began losing control in the grip of extreme G-forces he’d never felt before. An adrenalin rush to remember.

Kindred spirits

After a year in-country Bob eagerly resumed the civilian life he’d put on hold. What he did to amuse himself in the Army. photography, became a passion. When he and Connie met at Creighton they soon realized they shared some interests and ambitions. They were friends first and dated off and on. She was entranced by the romance of this tall, strapping veteran who took her up in his Piper Cub. He was drawn to her petite beauty and unabashed intelligence and independence.

Besides their mutual attraction, they enjoyed working in theater productions. They even appeared in a few plays together. Connie’s passion for theater extended to teaching dramatic play at Joslyn Art Museum. She also enacted the female lead, Lizzie, in an Omaha Community Playhouse production of The Rainmaker.

The pair benefited from instructors at Creighton, including two Jesuit priests who were mass communications pioneers. Before commercial television went on the air in Omaha, Rev. Roswell Williams trained production employees of WOW-TV with equipment he set up at the school. He founded campus radio station KOCU to prepare students for broadcasting careers. He implemented an early closed circuit television systems used to teach classes.

Connie Spittler works the board as Rex Allen gets ready to shoot a scene in the 28-minute film on the story of Ak-Sar-Ben. Published Nov. 16, 1968. (Richard Janda/The World-Herald).

“He was the person that brought television to Creighton University,” Connie says. “He was interested in it in students learning about it.”

Rev. Lee Lubbers was an art professor whose kinetic sculptures experimental, film offings and international satellite network, SCOLA, made him an “avant garde” figure.

“It was so unusual to have him be here and do what he did,” Connie says. “He stirred things up for sure.”

Right out of college she and Bob worked in local media. He directed commercials and shows at WOW-TV. She was a continuity director, advertising scriptwriter and director at fledgling KETV. She also worked in advertising at radio station KFAB.

Bob’s father was an attorney and there was an expectation he would follow suit but he had other plans.

“My father wanted me to be a lawyer and I just kept fighting that,” he recalls. “The gratifying thing about that is that after about 10 years of being in business he said, ‘I’m really kind of glad you didn’t go into it.'”

Bob calls those early days of live TV “fun.”

“I did little 10 second spots for Safeway. They’d just give me the copy and have me go shoot a banana or something. Well, one night I hung them up in the air and swung them and moved the camera and they were flying all over the place and Safeway just loved it.

“But it changed so much with (video )tape coming in. You can always look back and say, ‘Boy, what we could have done if we’d had that.'”

Taking the plunge

Bob and Connie then threw caution aside to launch a film production company from their basement. Don Chapman joined them to form Chapman-Spittler Productions. While leaving the stability of a network affiliate to build a business from scratch might have been a scary proposition for some, it fit Bob to a tee.

“To be honest with you I’m not a team player and I’m not a leader. I’m kind of a loner,” he says. “I could see corporate-wise I wouldn’t get anywhere. I had ideas and things I wanted to do myself. When I did get something done it was always off by myself and I figured out that was the way I wanted it.”

The fact that Bob and Connie brought separate skill sets to the table helped make them work together.

“We didn’t do the same things, that was part of it, so we weren’t competing with each other,” she says. “One other very important thing she did – she kept the books,” Bob notes.

It was unusual for a married couple to work together in the communications field then. Connie was also a rarity as a woman in the male-dominated media-advertising worlds.

She’s long identified as a feminist.

“I was a working woman in the ’50. We were just women that wanted to be able to work, to be able to make a living wage, that wanted to have a family and kids if we chose to but not that we had to.”

There were a few occasions when her gender proved an issue.

“Northern Natural Gas was interviewing for a position and they said there’s no way we can accept a female for this because this job entails going to a lot of parties that get too rowdy, so we’re sorry. When I was at KETV we were doing a documentary about SAC (Strategic Air Command) in-air refueling missions. I wanted to go up so I could write about it, but base officials said we can’t send up a woman, so I couldn’t do that. The station did send up a male director and he came back and told me about it and I wrote the script

“Otherwise, I don’t think I did experience discrimination.”

Bob’s beloved Piper Cub, ©Bob Spittler

She wasn’t taking any chances though when she broke into the field.

“I was one of the first people hired before KETV went on the air. My job was as an administrative assistant to work with New York (ABC). That was one place where I didn’t know if there’d be any problem with my being a woman so instead of signing letters Connie Kostel (this was before she was married), I signed them Con Kostel, so they wouldn’t know what sex I was. I didn’t have any problems.”

Connie will never forget the time she wrote a promo for a Hollywood actor on tour promoting his new ABC Western series.

“I directed him in the promo. When I got home Bob said, ‘How’d it go with the guy from Hollywood?’ I said, ‘He’s nice looking but he’s a loser, He had the personality of a peach pit. I just didn’t get anything from him at all.'”

She was referring to James Garner, whose Maverick became a hit.

In retrospect, she chalks up his lethargy to being exhausted after a long tour. “Thank heavens I didn’t want to be a talent scout.”

The salad days

She says when she and Bob had their own business she was put “in charge of some really big sales meetings” by clients who entrusted her with writing-producing multi-screen slide shows. These elaborate productions cost tens, even hundreds of thousands of dollars and often involved name narrators, such as Herschel Bernardi and Rex Allen.

She wrote-produced a 9-screen, 14-projector show for Leo A. Daly having never produced even a single-screen slide show.

“Inspired in the late ’60’s by our plane trips to the Montreal World Fair and the San Antonio HemisFair, Bob and I were both excited by multi-screen shows.”

Once, Connie was asked to produce show in three days to be shown in a tent in Saudi Arabia.

“I always wondered about the extension cord,” she quips.

Bob says Connie was accepted as an equal by the old boys network they operated in. “I never saw any signs of any rejection.” Besides, he adds, “she got along real well with people” and “she was good.”

For her part, Connie felt right at home doing projects for Eli Lilly, Mutual of Omaha, Union Pacific, ConAgra, Ak-Sar-Ben, the Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce and many other clients.

“I loved it, I absolutely loved it. And the thing I loved about the writing I did was that each one was a different subject. I’d go visit a big company like Leo A. Daly and they’d introduce me to their top people to interview. I’d be given all these research books and reports to read. It was like a continuing education. Working on the Daly account I learned a lot about architecture.

“Almost anything turned out to be really interesting once I talked to the people who worked there who were excited about their work.”

Their projects played international film festivals and earned industry awards. Bob worked with Galen Lillethorup at Bozell and Jacobs to produce the ‘The Great Big Rollin’ Railroad’ commercials for Union Pacific, which won the prestigious Clio for B & J. Bob recalls the North Platte, Neb. shoot as “fun,” adding, “We got a lot of attention out of it and we did get other business from it.” A few years later, Spittler Productions received their own Clio recognition for an Omaha Chamber project. Assignments took them all over the U.S. Bob would often do the flying.

“Bob either shot, scouted or landed for business purposes and I traveled to locations to research, write and produce sales meetings in every state in the U.S. with the exception of Alaska, Hawaii, Maine and Rhode Island,” Connie says.

One time when Bob let someone else do the flying he and a Native American guide caught a helicopter that deposited them atop a Wyoming mesa so he could capture a train moving across the wilderness valley.

“I sat up there with my Arriflex and that old Indian and waited for that train to come and neither of us could understand the other,” he recalls.

Connie once wrote liner notes for a City of London Mozart Symphonia produced by Chip Davis and recorded in Henry Wood Hall, London. Davis recommended her to Decca Records in London to write liner notes for a Mormon Tabernacle Choir album.

At its peak Chapman-Spittler Productions did such high profile projects the partners opened a Hollywood office. Spittler worked with big names Gordon McCrae and John Cameron Swayze.

The Nebraskans made their office a Marina del Rey yacht, the Farida, supposedly once owned by King Farouk and named after his wife.

“On one occasion I flew a Moviola (editing machine) out there and we edited one of the Union Pacific commercials on the boat over in Catalina,” Bob remembers.

An InterNorth commercial was edited there as well.

Connie adds, “I used the yacht as a wonderful place to write scripts.”

“Ours was 40-foot. We were able to sleep on it. I took the boat out a lot. When we left, that’s where it stayed,” Bob says. “Our boat was right next to Frank Sinatra’s boat off the Marina del Rey Hotel. His was a converted PT-boat.”

Bob also did his share of flying up and down the Calif. coast. Connie wedded her words to his images to tell stories.

One of Bob and Connie’s favorite projects was working with Beech Aircraft. Using aerial photography Bob shot in several states, they produced a film on the pressurized Baron and later a film on the King Air for the Beechcraft National Conference in Dallas, Texas

The variety of the projects engaged her.

“Curiosity is my favorite thing,” she acknowledges.

A hungry mind is another attribute she shares with her mate, as Bob’s a tinkerer when it comes to mechanical and electronic things.

“Bob is curious, too,” she says. “He’s always trying to think of something to invent. Years ago he went out and brought home one of the first PCs – a TRS 80. He wanted to play around with it. Then he pushed me into playing around with it and then he made all the kids learn it so they could do their college applications on the computer. So he dragged the whole family into the computer generation.”

The way Bob remembers it, “When I brought that first computer home we had it for a week and I was still trying to figure out how to turn the damn thing on and my son was programming it. He taught me. But that was neat. I’m way behind now on technology,” though he has digital devices to share and store his work.

Connie Spittler

Reinventing themselves

Bob and Connie’s collaborations continued all through the years they worked with Don Chapman. When that partnership dissolved the couple went right on working together.

“We were complementary I suppose in many ways,” she says. “When we had the business I wrote and produced, he shot and edited, so it just worked.”

By now, Connie’s written most everything there is to write. Being open to new writing avenues has brought rewarding opportunities.

“You have to be open to writing about other things just to keep your mind going. I received a phone call in Tucson one day and this person said, ‘We heard about you and we wondered if you’d come read your cowboy poetry at our trail ride?’ I’d never written any cowboy poetry but it sounded so much fun. I said, ‘Let me think about that.’ Well, I like cowboys and nature and all these things, so I agreed to do it. Bob and I ended up making this little book Cowboys & Wild, Wild Things.”

When she got around trying her hand at fiction writing, it fit like a glove.

“I was writing my first fiction piece and Bob said to me, ‘Do you know for the first time since we’ve come down here every time you come out of your office you’re smiling?’ Before, my projects were all kind of heavy, fact-laden subjects. I mean, there was creativity but it was mostly how do you take this subject and make it interesting. With the novel, I could make it anything I want.”

She hit her fiction stride with the books Powerball 33 and Lincoln & the Gettysburg Address.

A project that brought her much attention is the Wise Women Videos series she wrote about individuals who embody or advocate positive aging attributes. The videos have been widely screened. For a time they served as the basis for a cottage industry that found her teaching and speaking about mind, body, spirit matters.

For the series, she says, “I found interesting women I thought other people should listen to. None of them were famous. They were just women introduced to me or once people knew I was doing the series they would say, Oh, you should talk to this person or that person.”

As the series made its way into women’s festivals and organizations she got lots of feedback.

“When I would get letters from cancer groups or prisons or abused women groups I thought good grief, how wonderful that can happen, that they can ‘meet’ these women through these videos.”

The series is archived in Harvard University’s Library on the History of Women in America.

She’s given her share of writing presentations and talks – “I love to attend book clubs to discuss my books” – but a class on memoir she taught in Tucson took the cake.

“The class was inspired by one of my Wise Women Videos and began with each student telling a story about their first decade in life. Then each time we met the women chose one important memory to tell the group about the next decade. The assignment was to write that story for family, friends or themselves. An interesting thing happened: When the class sessions reached the end of their decades and the class was finished the women were so connected from the experience they continued to meet independently for years afterward.”

Bob and Connie on their deck

Legacy

Connie’s own essays and short stories are published in many anthologies. She achieved a mark of distinction when an essay of hers, “Lint and Light,” inspired by the work and concepts of the late Neb. artist and inventor Reinhold Marxhausen, was published in The Art of Living – A Practical Guide to Being Alive. The international anthology’s editor sent an email letting Connie know the names of the other authors featured in the book. She was stunned to find herself in the company of the Dalai Lama, Mikhail Gorbachev, Deepak Chopra, Desmond Tutu, Jean Boland, Sir Richard Branson and other luminaries.

“I almost fell off the chair. When that happened I was like, I wonder if I should quit writing because I don’t think I’ll ever top that.”

Bob says he always knew Connie was destined for big things. “It didn’t surprise me a bit.”

Much of her work lives on thanks to reissues and requests.

“It’s interesting how you do something and it isn’t necessarily gone,” she says. “Some of those things have a long life. I always say a book lasts as long as the paper lasts.”

Now with the Web her work has longer staying power than ever.

Meanwhile, one of Bob’s photographs just sold in excess of a thousand dollars at a gallery in Bisbee, Arizona.

Living in Tucson Connie says she was spoiled by the “absolutely wonderful writers community” there. She and some fellow women writers created their own salon to talk about art, music, theater and literature. “The one rule was you couldn’t gossip – it was just intellectual, interesting talk,” she says. “One night the subject of erotica came up. The next day I went to a bookstore and I said to this young female clerk, ‘Do you have a place for erotica here?’ And she said, ‘Oh erotica, yes, let me get my friend, she loves erotica, too!’ and they both took me off to the section and told me all their favorite books. I didn’t get any of their favorites, but I did get this one, Erotica: Women’s Writing from Sappho to Margaret Atwood.”

Connie found writers published in its pages she never expected.

“When I opened this book the first thing I saw was Emily Dickinson, then Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte, all these well-known, respected authors. Their work is considered erotica for their time because it was romantic reading with sensual undertones. It’s in your mind, not graphic. I thought it so interesting that that could be erotica. It occurred to me a book club about erotica could be fun.”

Only Connie’s resulting book is not erotica at all but “a cozy mystery.”

“A librarian who gave it 5 stars said, ‘You would not be embarrassed to discuss this book with your mother.'” In the back Connie offers a list of erotica titles for those interested in checking out the real thing.

She’s delighted the book’s being published in the Czech Republic.

“My dad was a hundred percent Czech. I asked the publisher if I could add my maiden name and change the dedication to dedicate it to my dad and my grandmother and Czech ancestors and they said, ‘We’d love that.’ My dad’s been gone a long time and he didn’t have any sons and he always said to me, ‘That’s the end of my line,’ so now I thought it will live on – at least in the Czech Republic.”

Words to live by

Closer to home, Connie’s developed a following for the Christmas Card essays she pens. Her sage observations and sublime wordings are much anticipated. This year’s riffs on the fox that visits their property.

“Sometimes in the late evening he trots along the grasslands and pond. Bob, watching TV down in the family room, has spotted the scurrying fox several times – always unexpected and too quick for his camera lens. I haven’t seen this wild urban creature yet since I’m in bed during the usual prowling gorse. Still, imagining his billowing tail flying by int he dark adds a flurry of magic to the winter night…

“As our dancing, prancing fox moves in and out of focus and time, I think of the surprising people, pets, events and moments that visit our lives. They come and go with reminders to be grateful for unexpected things that happen along the way…fleeting or lingering…illusive…intriguing.

“This season our message comes from the fox, a wish for wisdom, longevity and beautiful surprises. Do keep a look out. You never know who you’ll meet or what you’ll see.”

Finally, as one half of a 57-year partnership, Connie proffers some advice about the benefits of passion-filled living.

“One beautiful thing about writing is that by picking up pencil and paper, or using computer, iPad, you can write anywhere. I’ve written on a beach, by a pool, a yacht and in an RV. I always encourage anyone interested in writing to sit down and go to it. It doesn’t cost any money to try and studies show the creativity of writing keeps the mind alert. And it’s a feeling of accomplishment, if you finish a piece or even if you finish a good day writing.”

The same holds true for filmmaking and photography. And for delighting in the wonders of wild foxes running free.

Follow the couple at http://www.conniespittler.com.

Natural imagery: Tom Mangelsen travels far and wide to where the wild things are for his iconic photography, but always comes back home to Nebraska

Tom Mangelsen’s journey to becoming a world-class nature-wildlife photographer is told in my New Horizons cover story now available at newsstands. The Nebraska native truly goes to where the wild things are to make his iconic photographs. His work is available at his Images of Nature galleries across the country. But as my story details, no matter how far afield he travels for his work, and he travels all over the world, he always comes back home, to where the Platte River flows and the cranes migrate in his native land. There, among the shallows and sandbars, his love for nature and photography first took hold and every year he returns for the song and dance of that perennial ritual that speaks deeply to his heart and soul.

Natural Imagery

Tom Mangelsen travels far and wide to where the wild things are for his iconic photography, but always comes back home to Nebraska

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the February 2015 New Horizons

Growing up on the Platte

Thomas Mangelsen had no inkling youthful forays along the Platte River’s sandbars and shores would be the foundation for a world-class nature photography and conservation career.

He didn’t even take pictures growing up in the 1950s into the 1960s. That calling didn’t come until later. Without knowing it though his Huck Finn-like boyhood spent closely observing the natural world around him was perfect preparation for what became his life’s work.

His retailer father Harold Mangelsen, founder of the family crafts store now run by Tom’s brother David, was an avid hunter who championed Platte River Basin conservation before environmental stands were popular. The Mangelsens made good use of a family cabin on the river. There, Tom gained a deep appreciation for the wild, an ardor imbued in the painterly images he makes of species and ecosystems. All are available as framed prints at his nationwide Images of Nature galleries. Then there are his photo books, including his latest, The Last Great Wild Places. His work sometimes accompanies articles in leading magazines, too. Best known for his stills, he’s also shot nature films.

From his Jackson Hole, Wyo. residence he travels widely, shooting on all seven continents. He returns to Neb. to visit family and friends. Every March he’s back for the great crane migration, often in the company of star anthropologist Jane Goodall, a board member of the nonprofit Cougar Fund he co-founded to protect wild cougars.

He’s won national and international recognition for his work and brought wide attention to the annual crane migration, the importance of the Platte and endangered animal populations.

None of it may have happened were it not for that outdoorsy, rite-of-passage coming-of-age that gave him a reverence for nature. That, in concert with an abiding curiosity, a restless spirit and a good eye, are the requisite qualities for being a top wildlife photographer.

His earliest memories are of the meandering Platte’s well-worn life rhythms. Mangelsen largely grew up in Grand Island, where he was born. The family moved to Ogallala, where his father opened his first store, before moving back to Grand Island and finally to Omaha when Tom was 15. Wherever he lived, he spent most of every summer on the Platte. When not hunting waterfowl, there were decoys to be set and tangles of driftwood to be dislodged. Mostly, though, it was sitting still in anticipation of a good shot.

“That’s all we did all summer,” says Mangelsen, who got a .410 shotgun at age 6 or 7.

On hunts his father bemoaned the low river levels resulting from diversions to irrigate farms and to feed city water supplies.

“He felt there should be some water left over for the wildlife.”

At times water management policies left the Platte dry.

Mangelsen says, “It went in 50 years from a lot of water to like 15 percent of what it used to be. It’s probably still only 20 percent now from its historical flows. My dad was very much into that. He testified, he wrote letters. So in that sense he was the first conservationist I knew. He taught me all the ethics of hunting – don’t shoot stuff you can’t kill or don’t have a good chance of killing. He taught me how to call, too.” Coached by his father Mangelsen twice won the world’s goose calling championship.

Under their father’s tutelage Tom and his brothers learned to make their own decoys. painting them every year.

Tom wanted to know about sustainability before it had a name.

“When I wasn’t asking questions I saw what worked and what didn’t,” he says of dam releases and other efforts to regulate river flow and to balance the ecosystem.

Watching and waiting became engrained virtues.

“Basically we’d sit there for a week without seeing a flock of geese maybe, That’s just what you did. The challenge was waiting and then when you had the opportunity maximize that by calls, by setting decoys. We changed decoy sets five or six times a day depending on the wind and my dad’s moods or boredom. We’d see pheasants, hawks, eagles and lots of other birds. I’d watch through my binoculars because I was curious. So I fell in love with birds and not just a few.”

From gun to camera

He eventually discovered what makes a good hunter makes a good photographer.

“In reality I traded in my guns for a camera. It’s all the same process, except I don’t have to pick ’em and I don’t have to clean ’em and I can shoot ’em again. It’s like catch-and-release.”

Both disciplines depend upon patience.

“Well, that’s my biggest asset. I didn’t know any better because that’s how we grew up. I don’t mind sitting in a blind for days. I’m entertained just by watching things. People ask, ‘What do you do – read?’ Well, you can’t read if you’re in a blind. If you are, you’re not watching. If you’re not watching you don’t see something, and if you don’t see something you’re not going to photograph it. So you sit there and you wait and you look. So, yeah, I’m very patient and that’s the biggest gift to have.

“But I’m also a very keen observer. From a photographic standpoint you have to anticipate where an animal might be, what it might do. Is it going to go here or there? Is it going to go by its mate? Is it going to sit on the eggs and if so how long will it be there? If it comes flying in will the best cottonwood be in the background.”

He might never have picked up a camera. Like his brothers he worked in the family’s Omaha store. To please his dad he majored in business administration at then-Omaha University. Preferring a smaller school, he transferred to Doane College in Crete after two years.

“It was probably the best thing I did,” he says.

He changed majors from business to biology, with designs on a pre-med regimen, until finally settling on wildlife biology.

Finding his mentor

After graduating from Doane an important figure came into his life to encourage his new path.

“To continue my graduate studies in wildlife and zoology I went down to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to see Paul Johnsgard. Even at that time at age 39 he was considered the world’s authority on waterfowl. I was intrigued by his background, He’s a duck carver and a sketcher and a photographer and a writer and a teacher.”

But Mangelsen first had to convince Johnsgard to take him on, which required a leap of faith since this would-be protege was no academic star. With the military draft hanging over his head, Mangelsen needed Johnsgard to overlook his deficiencies before Uncle Sam called.

Paul Johnsgard

“It was 1969 and the height of the Vietnam War. I asked Paul if he would be interested in being my advisor in graduate school. I showed him my transcripts and he said, ‘These are really not up to snuff.’ He always took straight A students and only took five students a year. I said. ‘Well, I won the world’s goose calling championship twice and I have a cabin on the Platte, and could you maybe make an exception.'”

Johnsgard did, vouching for him to the dean of students. “I think he was mostly trying to stay out of the service,” Johnsgard quips about Mangelsen. The student didn’t let the teacher down. “Paul told me, ‘You may have been one of my worst students but you probably did the best of all.’ So in the end it worked out.”

Johnsgard soon recognized familiar qualities in his student.

“What i saw in him was mostly myself. He was a hunter and although by then I had long since given up hunting I went through a short period of loving duck hunting and that got me to love ducks. And I think Tom already had begun to stray well away from hunting as a passion to be much more interested in photography.

“I set him to work on a little duck counting project but it mostly became lessons in photography, and having a grand time.”

At Johnsgard’s direction Mangelsen bought his first camera, a Pentax, and first lens, a 400-millimeter.

Tom says, “Paul and I would meet on weekends and we’d photograph ducks, geese and cranes, mostly birds in flight, and I got hooked on it.”

The bond between master and pupil was forged during those times.

Johnsgard says the Mangelsen family’s hunting blinds “proved to be perfect photographic blinds,” adding, “I long wanted to spend time on the Platte photographing and this was a perfect chance, so we both got something out of the deal and we became very close friends.”

It was all manual focus, settings and exposures then. Johnsgard helped teach Mangelsen the ropes.

“He told me, ‘You focus in the eye and you shoot at five-hundredths of a second – that will stop the wings,” Mangelsen recalls.

That and a Nikon workshop were Tom’s only formal training. What Johnsgard provided was more valuable than any camera lessons.

“Paul turned me onto watching birds and he gave me a respect for the waterfowl. The more I learned the more I got interested in being a photographer,” Mangelsen says. “I didn’t have any plans other than doing it for a hobby. Then I started a darkroom in the basement of my family’s home in Westgate. I processed my film and I made prints. All black and white. Then I switched to color because it’s more conducive to shooting wood ducks and mallards.”

Tom and his brother David framed those early prints themselves. They banged away late at night in the garage of the family home until their father banished them to a spare warehouse.

Johnsgard says Mangelsen’s talent was apparent from the start. “Tom was very good. He had very good eye sight and hand-eye coordination in terms of focusing on birds moving very rapidly. When we compared pictures his were usually better than mine. He had great ability and it might have been a carryover from his hunting skills.”

Several kindred spirits shaped Mangelsen, who says, “there were all these interesting people I kept meeting along the way,” but he regards Johnsgard as a second father. These men bound by shared interests still get together on the Platte most every year.

“There’s always been a kind of parental sense dealing with Tom, especially in those early years when he was still lost in the woods, if you will,” says Johnsgard, who knows Mangelsen’s career has been no overnight success story but rather a slow steady climb. Once opportunity knocked, Mangelsen was prepared.

Paul Johnsgard and Yom Mangelsen

Making photography his life

By the time Tom heeded a long-held desire to live in the high country of Colo. he’d “found a different calling” than the family business though he concedes those retail roots taught him how to sell his work.

The mountains had beckoned from the time his family took trips to Estes Park. Then as a young man amid the counterculture movement, with peers joining communes, he moved to Nederland, Colo. outside of Boulder to live in an old one-room schoolhouse. He mastered photography and continued his education there.

“I was still taking some courses, like arctic alpine ecology, from the University of Colorado. At one of the classes this educational filmmaker, Bert Kempers, was doing a dog-and-pony slide show and the teacher knew I was interested in photography and introduced me to him after the class. Bert invited me to come have a beer and a burger with him and asked me if I was interested in work. I said sure.

“I told him I’d never used a movie camera and he said, ‘If you can shoot stills, you can shoot movies,’ which isn’t necessarily true because they’re quite different mindsets. But I didn’t know any better, so he taught me how to use a movie camera. We had an old Bell & Howell with the three-turret lens. Then we moved up to a Bolex and then to an Arriflex. We were doing educational biology films for the University of Colorado. Our advisor there, Roy Gromme, had a famous father, the nature painter and conservationist Owen Gromme.”

Mangelsen later met and was befriended by the elder Gromme.

“Owen was one of the first men making limited edition prints of his paintings, so I thought, Well, why couldn’t I make limited edition prints of photographs? I was stupid and naive at the time and thank God I was because that’s how I started selling the prints.”

Mangelsen opened his first gallery in Jackson Hole in 1978.

Not only did Gromme show him a way to market his work, but he modeled a fierce commitment to bio-diversity reinforced by others he met, including Mardy Murie Didl, widely considered the grandmother of conservation, and Jane Goodall. He also found inspiration in the work of such great photographers as Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, Ernst Haas, Edward Weston, Minor White, Paul Strand and Dorothea Lange. He and fellow Nebraska-native nature photographer Michael Forsberg are good friends. Nature painters like Robert Bateman are influences, too.

Projects with personal meaning

Learning filmmaking from Kempers paid huge dividends.

“I did most of the camerawork and Burt wrote, edited and put the films together. That was a great experience. For five years I made films. Out of that grew other films down the road.”

Among these later films was Cranes of the Grey Wind about the birds’ reliance on the Platte habitat.

“My whole deal with that was to do something about the Platte River, which was running dry. I wanted to show people, mostly in Neb., that we have a resource here that’s vital to the whooping crane migration – a natural phenomenon so incredible that it matches any in the world.”

This was Mangelsen’s chance to combine his talent for photography with his passion for the river and his interest in seeing its ecosystem valued and protected. The fact he could shed light on something so dear was irresistible. He didn’t want to see past mistakes repeated.

“The Platte literally went dry when I was a kid because they sucked so much water out of it for irrigation and for cities like Denver. They were putting more and more dams up. My brother Billy and I would go down to the river to see how deep the water was and sometimes couldn’t even find it. Then when the water came in the fall when the irrigation season was over it would trickle down from (Lake) McConaughy and Johnson Reservoir and people would call us and say, ‘The water’s coming, the water’s coming,’ and we’d wait for it. That’s the truth.

“It was a shrinking river with shrinking channels. It was becoming a woodland not that useful for ducks, geese and cranes. That’s changed quite a bit now. There’s been lawsuits over the dams and things. They have to keep a certain amount of water in the river now. Thank God for the whooping cranes or it probably never would have happened.”

He made Cranes of the Grey Wind for the Whooping Crane Trust. His mentor Johnsgard wrote the script and a companion book.

Johnsgard also turned Mangelsen onto Jackson Hole.

“We had spent time in greater Yellowstone,” Mangelsen says. “He introduced me to that area. I fell in love with Jackson Hole because of that trip I made with him when I was his assistant in the field.”

Johnsgard was doing field work in the Tetons when Mangelsen wheeled-in via a jeep. After a week there Mangelsen was sold.

The two men long talked about doing a book together but it wasn’t until last year they finally released one, Yellowstone Wildlife. They’re working on a new book about the cranes of the world.

Mangelsen’s interest in cranes led him on a kind of pilgrimage that helped generate more projects.

“I wanted to see where the cranes lived in the summer, I wanted to see where they nested in Alaska, where they wintered in Texas off the coasts and all the migration stops along the way.”

National Geographic got wind of this intrepid photographer following the cranes’ migration patterns and they commissioned him for a project that led to a PBS Nature film and so on. His reputation made, his books became best sellers and more people started collecting his prints. He opened more galleries to keep up with demand.

Staying true to his convictions

Even though he’s gained fame few photographers ever attain, the values, principles and rituals of his work remain immutable.

“You photograph birds in the spring when they’re breeding because that’s when they’re most colorful. You photograph mammals in the fall when they have their antlers and their best color.”

He works in all kinds of weather and even prefers when it’s not a picture postcard day. “Blue skies and sunshine are boring to me,” he says. Old Kodak film stock required “you put the sun at your back because the film was so slow it was sensitive to light.” But, he adds, “it’s all changed with higher speed films and now of course with digital.”

Catching the best light is a sport unto itself.

“They call it the golden hour, around sunrise and sunset. But you can also have wonderful light around storms and rain and fog, so there’s not one light I look for. But obviously the golden light, the early light or late light is classically the best light.”

He once made an image of a mountain lion during the last light of the day, the creature silhouetted against a black cave containing her den.

“That very direct light is really beautiful,” he says.

An elephant “against a black, windy, dusty African sky can be beautiful, too,” he says, as it was when he photographed one amid a rolling storm that shone “this golden light sideways across the plain.”

Another time he captured a group of giraffes in the noon day light but with a storm riding in to create a black sky.

“So there’s millions of different kinds of light,” he says.

From the start, Mangelsen’s viewed his work with an eye to education.

“I looked at all this as not collecting trophies as most photographers do early on, you know, shooting the biggest bucks or the biggest bull elk or the biggest rams or whatever. Instead, I was trying to collect animals in their environment – showing how they live.”

His by now iconic image of a brown bear catching a sockeye salmon in its mouth – entitled ‘Catch of the Day’ – has been so often reproduced he’s lost count. But that picture taken in 1988 at the head of Brooks Falls in Katmai National Park, Alaska and which adorned the cover of his first book, Images of Nature, would not have been possible if he didn’t intentionally look and wait for it.

“It was a moment that hadn’t been recorded before,” he says. “There’s thousands of pictures of bears at the falls. I’d seen them, I’d gone there. I’d researched bear footage. I happened upon a book about the bears of Brook Falls and I saw a picture from a distance of fish jumping and I wondered if you could shoot that, just head and shoulders.”

To get this image he’s now most identified with meant having a plan, then letting his instincts take over. It’s still his M.O. in the field today.

“Anticipation, pre-visualizing, observation is a huge part of it,” he says.

For “Catch of the Day” he was 45 yards from the bear on a platform 10 feet off the river. From his homework he says he knew the bears positioned themselves at the top of the falls, “which is kind of the prime fishing spot,” where they practically call to the salmon, “come to me.”

He says the picture became a sensation because “it’s unique – nobody got that moment before.” Some felt it was too good to be true – suggesting he’d manipulated or altered the image. “It was shot in ’88, before photo shop was invented,” says Mangelsen, who’s emphatic that the picture was not enhanced in any way.

Wherever he is, no matter what he’s photographing, his interest is documenting animals as they actually behave in their natural habitats.

“That’s my goal,” says Mangelsen, who decries the short-cut method of shooting animals on game farms.

“These farms have everything from snow leopards to tigers to deer, bears, foxes, cougars, every animal imaginable. Well, snow leopards don’t live on this continent, but for a few hundred dollars in the morning and for a hundred dollars more you can shoot a snow leopard and a raccoon in the morning and a cougar and a wolf in the afternoon and a fox and a caribou the next day, and by the time you’re done with the week and for a few thousand dollars you can have quite a collection.

“But baiting is used and the animals are half starved to death. There’s electric fences around them so they don’t leave. They are released to perform for the camera and the rest of the time they live in cages the size of a coffee table, which is criminal.”

An activist artist

His work in the wild has instilled in him a passion and activism.

“I’ve learned that all animals are really important, from the smallest to the largest, not just the bears and the wolves and the cougars but tiny animals. People may joke when certain things are put on the endangered species list – it might be a mouse or a small bird or a frog. But we’ve learned that the disappearance of something as tiny and familiar as bees is a whole chain reaction.

“We need to recognize they’re all important and we shouldn’t take it for granted. We also need to recognize individuals within a species are important. We shouldn’t be killing wolves. There’s no good reason to shoot a wolf unless it’s threatening your livestock or your person or your baby. Then you’re entitled to do something about it.”

But he says lawmakers tend to get their priorities mixed up.

“Nebraska’s a great example. They started this stupid cougar season even though there’s only 20 animals in the whole state. The season’s based on a couple legislators who think they saw a cougar moving across their pasture. I dare say I’ve seen more cougars in downtown Boulder, where I lived, than anyone in Neb. has in their entire life. They’re just part of the ecosystem there.”

He says in Colo. human encroachment on wilderness areas means foraging animals become part of the foothills experience. He says the answer’s not to kill displaced cougars but to coexist with them.

“Studies show it’s counterproductive to hunt things like cougars and wolves. Some people like to create fear of these hard carnivores. Some Joe Blow who hasn’t done his homework thinks they’re going to save babies and create safe zones if they kill all the big guys that prey on other animals. What they don’t realize is the big picture. They think they’re heroes somehow because they’re killing things with big teeth.

“It’s a Duck Dynasty kind of mentality.”

He’s outraged by Neb’s recently enacted cougar hunting season.

“It’s unconscionable to basically have open season on this great animal that you have so few of in the whole state. There’s no reason to kill a cougar other than a real valid threat to humans and none of that’s occurred in Neb. or in Wyoming. There’s no scientific reason. It doesn’t create more deer, it doesn’t make it safer. If you end up shooting the older, knowledgeable cougars which are still teaching their young how to hunt then the young are the ones that go out there to become juvenile delinquents looking for food in people’s backyards.”

He says the public has largely unfounded fears of animals like cougars or bears attacking humans.

“You’d be much more likely to get hit by lightning. People don’t put that into perspective. They’re fearful of what they don’t know.”

He supports well-informed hunting policies and practices. “I’m not against hunting if you do it ethically and cleanly and you do it for meat.”

He disdains hunters who kill animals for trophies. “They’re totally insensitive to the fact these animals have a great place in the ecosystem. Without them there are too many deer, they over graze, then there are no rabbits and beavers. It’s a top down thing.””

He’s quick to criticize hunting and wildlife management abuses. “I took a picture that appeared in the Jackson Hole Daily of these hunters at Grand Teton National Park shooting elk off the road. There were no rangers on duty – they were all at a meeting that morning and the hunters knew it for some reason. The game and fish and the park service got their tits in a wringer so to speak.

“National parks ought to be refuges for animals.”

The Cougar Fund tries to prevent mishaps like this from happening.

“The biggest threat to cougars is sport hunting. About 3,500 cougars a year are killed. Seventy five percent of those are females who are pregnant or have dependent young who will die without their mother. That’s tragic. It’s criminal to be shooting an animal that has young dependents. What our job to do is to educate people that cougars have a place and that killing cougars does not make it safer for people.”

He says the organization also monitors game and fish departments “to hold their feet to the fire.”

For his book Spirit of the Rockies: The Mountain Lions of Jackson Hole he followed a mother cougar and her kittens for 40-plus days, detailing their precarious existence and overturning some myths along the way.

Mangelsen’s travels around the world have put him on intimate terms with the challenges certain animals face on other continents.

“Africa’s in dire straits right now mostly because of the illegal trade in wildlife. Elephants are being slaughtered for their tusks and rhinos for their horns. They say one elephant is killed every 15 minutes. A lot of large elephants are gone. Poachers are shooting baby elephants that have tusks the size of a hot dog. Ivory and rhino horn are worth as much as gold is now. America has its own guilt over that in buying ivory trinkets. People don’t understand that every ivory trinket adds up to a wild animal. Most of the ivory and rhino trade is in China now because of the growth of the middle class there. The middle class didn’t exist not that long ago and now that millions have become affluent they want the cars, they want the fashions, they want the trinkets.

“Rhino horn has absolutely no more value than your toenails or fingernails do. There’s absolutely nothing there for medicinal purposes or aphrodisiacs or any of that. It’s all culture, all tradition, all bullshit. And ivory is just for ornamental purposes and as a status symbol.”

He’s appalled by this rampant destruction of species.

“It’s an amazing crime. People are trying to stop it. People need to stop buying the stuff. It’s not the poor villager who trades in it who’s the problem. I mean, he’s going to feed his family, that’s what comes first, and this is a lot easier than trying to eek out a living goat herding. It’s the people buying it and then of course all the middle men. Terrorist organizations are involved. Elephant ivory is considered valuable enough to be traded for guns, so not only are elephants being killed, so are people. I’m working potentially on a feature film on this issue.”

Full circle

By now he’s photographed just about everything that walks or runs or flies – from elephants to elk and from penguins to peregrine falcons. Two bucket list exceptions are wild snow leopards and pandas. He’s developed some favorites, especially polar bears, brown bears and grizzly bears, and he just hopes it isn’t too late for these creatures.

“They’re really intelligent, they’re beautiful to look at, they’re at the top of the food chain. They’re like wolves in that way. Wolves are terribly persecuted for no good reason. With all these animals there’s a competition with man. It’s not only a competition its a threat.”

There are consequences to being so outspoken. He says, “I’ve been threatened by people for speaking out.”

If there’s one place in the world that has the greatest pull for him it’s the Serengeti in East Africa, which is where he was in January.

“I went to photograph elephants before they’re gone. They really figure they’ll be extinct in 14 years.”

In March he’ll be back home, on the Platte, where his journey in photography began, watching the cranes again. Jane Goodall at his side. He still can’t believe she’s a friend.

“She was always a hero.”

He’d briefly met her but it wasn’t until 2002, when he was asked to introduce her at a talk she made in Jackson Hole, he got to know her.

“She happened to have the following day off and I took her to Yellowstone and we just had a great time. We talked about cougars and Jane joined the Cougar Fund. She asked about the migration of cranes to Neb. and I told her we just happen to have a cabin right in the heart of that crane migration and she said I’m coming to see you and the cranes, and this will be her 13th year she’s come.

“Jane has been to thousands of more places than I have been and yet she comes to Neb. to see the cranes. That should tell you something – that these cranes and the river are very meaningful to her.”

He’s still in awe of her.

“She’s an inspiration to me in that she can keep going through a lot of adversity. She sees a lot of poverty and animal abuse. She’s working very hard on elephant-rhino preservation because it’s coming now to be such a big deal. She’s known for chimpanzees and yet she joined the Cougar Fund. She has more causes and energy than the man in the moon. She’s 80 now and yet she won’t let anything slow her down.

“She’s got so much energy, drive, passion. She’s unstoppable.”

As anyone who knows Mangelsen can attest, he could be describing his own indefatigable self. One that knows no bounds. But like the cranes he loves, no matter how far afield he travels, he always migrates home.

Follow his adventures at http://blog.mangelsen.com/.

Rock photographer Janette Beckman keeps it real: Her hip-hop and biker images showing at Carver Bank as part of Bemis residency

Here’s my Reader (http://www.thereader.com/) cover story on famed rock photographer Janette Beckman, whose images of punk and hip-hop pioneers helped create the iconography around those music genres and the performing artists who drove those early scenes. She’s been visiting Omaha for a residency at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, working on a portrait of the city. An exhibition of her photos of hip-hop pioneers and Harlem bikers is showing at the Carver Bank here through the end of November.

|

Janette Beckman

Rock photographer Janette Beckman keeps it real;

Her hip-hop and biker images showing at Carver Bank as part of Bemis residency

©by Leo Adam Biga

Now appearing in The Reader (http://www.thereader.com/)

Photographer Janette Beckman made a name for herself in the 1970s and 1980s capturing the punk scene in her native London and the hip-hop scene in her adopted New York City.

Dubbed “the queen of rock photographers,” her images appeared in culture and style magazines here and abroad and adorned album covers for bands as diverse as Salt-N-Pepa and The Police. Weaned on Motown and R & B, this “music lover” was well-suited for what became her photography niche.

She still works with musicians today. She’s developing a book with famed jazz vocalist Jose James about his ascent as an artist.

Her photos of hip-hop pioneers along with pictures of the Harlem biker club Go Hard Boyz comprise the Rebel Culture exhibition at Carver Bank, 2416 Lake Street. Beckman, documenting facets of Omaha and greater Neb. for a Bemis residency, will give a 7 p.m. gallery talk on Friday during the show’s opening. The reception runs from 6 to 8.

The Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts stint is her first residency.

“This is a new experience. It’s very refreshing. It’s kind of nice to get away from your life and open up your mind a little bit,” says Beckman, who describes her aesthetic as falling “between portrait and documentary.” “I truly believe taking a portrait of somebody is a collaboration between you and the person. I really like taking pictures on the street. I don’t want hair stylists and makeup artists. I don’t tell people what to do. I want to document that time and place – that’s really important to me. I want it to be about them and their lives, not about what I think their lives should be.”

Carver features a personal favorite among her work – a 1984 photo of Run DMC shot on location in Hollis, Queens for the British mag Face.

“They were just hanging out on this tree-lined street they lived on. I said, ‘Just stand a little closer,’ and they did. I love this picture because it expresses so much. It’s a real hangout picture and such a symbol of the times, style-wise. The Adidas with no laces, the snapback hats, the gazelle glasses, the track suits. It just expresses so much about that particular moment in time. And I love the dappled light on their faces.”

Salt-n-Pepa, ©Janette Beckman

She made the first press photo of LL Cool J, complete with him and his iconic boom box. She did the first photo shoot of Salt-N-Pepa while “knocking about” Alphabet City. In L.A. she shot N.W.A. posed around cops in a cruiser just as the group’s “Fuck tha Police” protest song hit.

She says her hip-hop shots “bring up happy memories for people because music is very evocative – it’s just like a little moment in time.”

The early hip-hop movement in America paralleled the punk explosion in England. Both were youthful reactions against oppression. In England – the rigid class system and awful economy. In the U.S. – inner-city poverty, violence and police abuse.

“Punk really gave a voice to kids who never really had a say. Working-class kids and art school kids all sort of banded together and started protesting, basically by being obnoxious and writing punk songs that were kind of like poetry, expressing what their lives were like. There was the shock factor of wearing bondage apparel and trash bags, putting safety pins in their noses. Really giving the finger to Queen and country and all that history. It was like, ‘Fuck you, it’s not that time, we’re fed up and we’re not going to take it anymore.'”

Her introduction to hip-hop came in London at the genre’s inaugural Europe revue tour.

“No one knew what hip-hop was. It was just the most amazing show. It had all the hip-hop disciplines. So much was going on on that stage – the break dancers and the Double Dutch and Fab 5 Freddy, scratching DJs, rapping, graffiti. All happening all at once. It blew me away.

“I met Afrika Bambaataa, who’s pretty much the father of hip-hop.”

Weeks later she visited NYC and “there it all was – the trains covered in graffiti, kids walking around with boom boxes, people selling mix tapes on the street. I got very involved in it.”

“New York was broke. Politically it was a mess. These kids had no future. Hip-hop gave this voice to the voiceless. They were singing ‘The Message’ (by the Furious Five). Where I was living there really were junkies in the alley with a baseball bat. It was no joke. You could see it unfolding in front of you and yet there was this vibrant art scene going on. Graffiti kids stealing paint from stores, breaking into train yards at night and painting trains in the pitch dark to make beautiful art that then traveled like a moving exhibition around New York. It was just fantastic. A real exciting time.”

She got so swept up, she never left. When big money moved in via the major record labels, she says. “everything changed.” She feels hip-hop performers “lost their artistic freedom and that almost punk aesthetic of making it up as you go along because you don’t really know what you’re doing. They were just experimenting. That’s why it was so fresh.” She expected hip-hop would run its course the way punk did. She never imagined it a world-wide phenomenon decades later.

“In the ’90s with Biggie and people like that it got massive. People are rapping in Africa and Australia. Breakancing is bigger than ever now..”

While capturing its roots she didn’t consider hip-hop’s influence then. “I was just in it doing it. I was just riding the wave.”

Portraying folks as she finds them has found her work deemed “too raw, too real, too rough” for high style mags that prefer photo-shopped perfection. “I don’t really believe in stereotypes and I don’t believe in ideals of beauty.” She’s even had editors-publishers complain her work contains too many black people.

Beckman’s surprised by Omaha’s diversity and intrigued by its contradictions. She’s shot North O barbershops, the downtown Labor Day parade, her first powwow, skateboarders doing tricks at an abandoned building and a South Omaha mural. She’s looking forward to taking pics at a rodeo and ranch.

She came for a site visit in July with one vision in mind and quickly had to shift gears when she began her residency in August.

“I wanted to photograph people on the street in North Omaha and I found there’s nobody on the street, so I had to try to wiggle into the community.”

Her curiosity, chattiness and British accent have given her access to events like the Heavy Rotation black biker club’s annual picnic at Benson Park. That group reminded her of the Ride Hard Boyz she shot last summer in New York.

“I was riding in the flatbed of an F-150 truck driven by one of the guys down this expressway with bikers doing wheelies alongside, All totally illegal. It was the most exciting thing I’ve done in years. Although it’s rebel in a way, the club keeps kids off the street and out of drugs and gangs. They’re the greatest guys – like a big family.”

The end of Sept. she returns to the NewYork “bubble.” An exhibit of her photos that leading artists painted on, JB Mashup, may go to Paris. She’s photographing a saxophonist. Otherwise, she’s taking things as they come.

“I try not to make too many plans because they tend to get diverted.”

Rebel Culture runs through Nov. 29.

View her Omaha and archived work at http://janettebeckman.com/blog.

The panoramic world of Patrick Drickey

Pat Drickey has been a fine art, architectural, and landscape photographer and he’s combined all of those talents and disciplines in a niche today that finds him making sumptuous and collectible panoramic images of the world’s great golf courses. This short profile should whet your appetite for the much longer piece I did on him, which can also be found on this blog.

The panoramic world of Patrick Drickey

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in Omaha Magazine

Omaha commercial photographer Pat Drickey knew he was onto something big when panoramic images he was commissioned to shoot of Pebble Beach Golf Course struck a chord in people. What began as an irrigation company ad campaign gig, flying him to elite courses around the world, became his own niche enterprise when the prints sold out and the Professional Golfers Association took note.

“That’s when I knew this could be a business,” said Drickey, an Omaha native whose Stonehouse Publishing company, 1508 Leavenworth St., specializes in producing iconic landscape images of premier golf courses around the world. Drickey, who takes the vast majority of the photographs himself and personally supervises the production of every single print, estimates more than 300,000 Stonehouse prints are now in circulation.

“We have branded the panoramic format for golf,” said Drickey, whose business operates out of a century-old red-brick building on the Old Market’s fringe.

In addition to being licensed by major courses, the United States Golf Association and the PGA, he has the endorsement of living legends like Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, giving him access to virtually any green. From Pebble Beach to Pinehurst to Medinah to St. Andrews to many other championship courses with rich histories, Stonehouse and Drickey are recognized names with carte blanche access.

“Which is a significant deal,” he said, ”because we are becoming that embedded in the lore of golf.”

Drickey’s neither the first nor only photographer to capture links in a panoramic way. But he believes what separates his work from others is the photo-illustration approach he uses in creating crystal-clear images of striking detail and depth. Employing all-digital equipment in the field and the studio Drickey brings exacting standards to his imagemaking not possible with film. Digital enhancements bring clarity from shadows and achieve truer, more balanced colors, he said. Even a sand trap can be digitally raked.

“It’s just incredible what you can do — the control you have,” he said.

He said Stonehouse has adopted the fine art Giclee process to its own printmaking methods, which entails using expensive pigmented archival inks on acid free watercolor paper to ensure prints of high quality that last.

“I want to produce a product that’s going to be around for a long time. The color hits that paper and stays with it — it will not fade. And that’s significant,” he said.

He feels another reason for Stonehouse’s success is its images portray the timeless characteristics that distinguish a scenic hole or course. He strives to indelibly fix each scene into a commemorative frieze that expresses the design, the physical beauty, the tradition. The clubhouse is often featured. Getting the composition just how he wants it means “waiting for the right light,” which can mean hours or days. Much care and research go into finding the one idyllic, golden-hued shot that speaks to golf aficionados. That’s who Stonehouse prints are marketed to.

Building-updating Stonehouse’s image collection keeps Drickey on the road several days a month. He’s half-way to his goal of photographing the world’s top 100 courses. One he’s still waiting to shoot is Augusta, home to the Masters.

“That’s one of America’s crown jewels. We are present at the other majors and we’d like to have a presence there. It’s just a matter of time. Those introductions have been made,” Drickey said.

Stonehouse prints grace golf books-periodicals. Drickey’s collaborating on a book project for Nebraska’s Sand Hills Golf Club course. He has more book ideas in mind.

His golf niche is an extension of the architectural photography he once specialized in. It’s all a far cry from the images he made with a Brownie as a boy. He still has that camera. A reminder of how far he’s come.

Related articles

- How to: Create panoramic photos in Adobe Photoshop (onsoftware.en.softonic.com)

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

Rudy Smith was a lot of places where breaking news happened. That was his job as an Omaha World-Herald photojournalist. Early in his career he was there when riots broke out on the Near Northside, the largely African-American community he came from and lived in. He was there too when any number of civil rights events and figures came through town. Smith himself was active in social justice causes as a young man and sometimes the very events he covered he had an intimate connection with in his private life. The following story keys off an exhibition of his work from a few years ago that featured his civil rights-social protest photography from the 1960s. You’ll find more stories about Rudy, his wife Llana, and their daughter Quiana on this blog.

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Coursing down North 24th Street in his car one recent afternoon, Rudy Smith retraced the path of the 1969 summer riots that erupted on Omaha’s near northside. Smith was a young Omaha World-Herald photographer then.

The disturbance he was sent to cover was a reaction to pent up discontent among black residents. Earlier riots, in 1966 and 1968, set the stage. The flash point for the 1969 unrest was the fatal shooting of teenager Vivian Strong by Omaha police officer James Loder in the Logan Fontenelle Housing projects. As word of the incident spread, a crowd gathered and mob violence broke out.

Windows were broken and fires set in dozens of commercial buildings on and off Omaha’s 24th Street strip. The riot leapfrogged east to west, from 23rd to 24th Streets, and south to north, from Clark to Lake. Looting followed. Officials declared a state of martial law. Nebraska National Guardsmen were called in to help restore order. Some structures suffered minor damage but others went up entirely in flames, leaving only gutted shells whose charred remains smoldered for days.

Smith arrived at the scene of the breaking story with more than the usual journalistic curiosity. The politically aware African-American grew up in the black area ablaze around him. As an NAACP Youth and College Chapter leader, he’d toured the devastation of Watts, trained in nonviolent resistance and advocated for the formation of a black studies program at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he was a student activist. But this was different. This was home.

On the night of July 1 he found his community under siege by some of its own. The places torched belonged to people he knew. At the corner of 23rd and Clark he came upon a fire consuming the wood frame St. Paul Baptist Church, once the site of Paradise Baptist, where he’d worshiped. As he snapped pics with his Nikon 35 millimeter camera, a pair of white National Guard troops spotted him, rifles drawn. In the unfolding chaos, he said, the troopers discussed offing him and began to escort him at gun point to around the back before others intervened.

Just as he was “transformed” by the wreckage of Watts, his eyes were “opened” by the crucible of witnessing his beloved neighborhood going up in flames and then coming close to his own demise. Aspects of his maturation, disillusionment and spirituality are evident in his work. A photo depicts the illuminated church inferno in the background as firemen and guardsmen stand silhouetted in the foreground.

The stark black and white ultrachrome prints Smith made of this and other burning moments from Omaha’s civil rights struggle are displayed in the exhibition Freedom Journeynow through December 23 at Loves Jazz & Arts Center, 2512 North 24th Street. His photos of the incendiary riots and their bleak aftermath, of large marches and rallies, of vigilant Black Panthers, a fiery Ernie Chambers and a vibrant Robert F. Kennedy depict the city’s bumpy, still unfinished road to equality.

The Smith image promoting the exhibit is of a 1968 march down the center of North 24th. Omaha Star publisher and civil rights champion Mildred Brown is in the well-dressed contingent whose demeanor bears funereal solemnity and proud defiance. A man at the head of the procession holds aloft an American flag. For Smith, an image such as this one “portrays possibilities” in the “great solidarity among young, old, white, black, clergy, lay people, radicals and moderates” who marched as one,” he said. “They all represented Omaha or what potentially could be really good about Omaha. When I look at that I think, Why couldn’t the city of Omaha be like a march? All races, creeds, socioeconomic backgrounds together going in one direction for a common cause. I see all that in the picture.”