Archive

A good man’s job is never done: Bruce Chubick honored for taking South to top

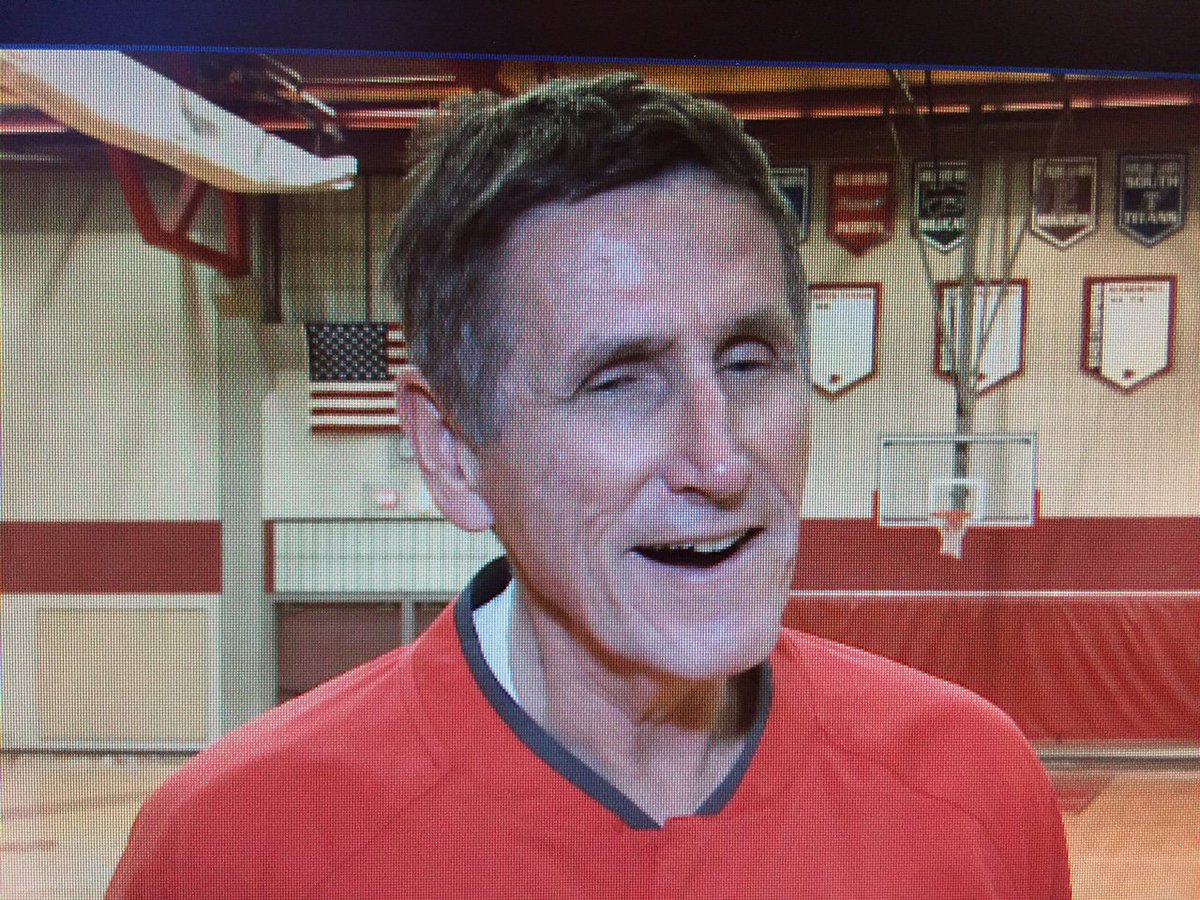

Bruce Chubick cuts a John Wayne-like figure with his tall frame, square jaw and plain-spoken, don’t-mince-words ways. He is, for sure, a throwback to an earlier era and in fact at age 65 he represents a distant generation and hard-to-imagine time to the players he coaches at Omaha South High. But the well-traveled Chubick, who is nothing if not adaptable, has found a way to reach kids young enough to be his grandchildren and great-grandchildren and gotten them to play hard for him. The South High boys basketball program was down when he took it over about a dozen years ago. It was the latest rebuilding job he took in a long career that’s seen go from school to school, town to town, much like an Old West figure, to shake things up and turn the basketball fortunes around before lighting out for the next challenge. Much like his counterpart at South, boys socer coach Joe Maass, who has risen the school’s once cellar-dweller boys soccer program to great heights, Chubick has elevated South High hoops to elite status. After coming close the last few years, Chubick’s Packers finally won the state Class A title this past season – he survived a heart attack en route – and for his efforts he’s been named Nebraska High School Coach of the Year. His team’s championship came just weeks after South’s soccer team won the Class A crown, giving the school and the South Onaha community it represents the best run in sports they’ve had in quite a while.

A good man’s job is never done: Bruce Chubick honored for taking South to top

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in El Perico

Omaha South High 2016 Nebraska High School Coach of the Year Bruce Chubick and his wife Dianne envision one day taking off in their new motor home and not coming back. The couple recently made a road trip by car, but duty still calls the much traveled Chubick. At 65 he’s the metro’s oldest head coach. He’s back prepping for the next boys basketball season with his reigning Class A state champion Packers.

He lost key players from that 28-1 squad that won South’s first state basketball title since 1990. South is the latest rebuilding project he’s engineered at Nebraska and Iowa schools. South came close to hoops titles under him in 2015 and 2012 before breaking through versus Fremont in last March’s finals – giving him his second title after leading West Holt to the C1 crown in 1988 behind his son Bruce.

“It was real satisfying we got it done. I think I appreciated this one a lot more just knowing how valuable that is for a community and school,” he said.

This coming season Chubick lacks depth but has talent in returning all-Nebraska star Aguek Arop. The athletic wing bound for Nebraska may be the main reason Chubick’s coming back despite health concerns. In the midst of last year’s dominant run Chubick suffered a heart attack during a game and elected to coach through it before seeking treatment.

“I didn’t want to quit on the players,” he explained.

He’s no stranger to toughing out difficulties. His son Joe had brain cancer and the family endured an ordeal of doctors, tests and procedures. To get away from it all, Chubick built a cabin in the Montana wilderness, where the family went off the grid for two years. It was a trying but healing time.

“It made the family close. I wouldn’t want to do it again,” he said. “it was a simple but tough life. There’s a lot of stories there, trust me.”

He later survived a kidney cancer scare. Then the recent heart issue. Stints opened clogged arteries. He’s still coaching because he keeps his word.

“I promised Aguek (Arop) when he came in I would stay until he graduated, so I want to keep my word,” said Chubick, who may have his best player ever in Arop. “Aguek is probably the most gifted of all of them, i mean, he’s really special.”

It’s no accident Chubick calls rebuilding programs “the fun part” of his job. He’s been building things his whole life. That cabin. Houses,. Until now, he’d always left after building a program up. “Once you get ’em built I never thought it was that much fun.” But he’s still at South even years after laying a successful foundation. “South happened toward the end of my career. It’s pretty comfortable. I really like South. It’s a good place for us. We found a home when we landed in South Omaha. Once we got this thing built I thought I might as well enjoy it a few years before I turn the keys over to somebody else.”

His “logical” successor is his son Bruce – his top assistant.

This lifelong student of the game grew up in Council Bluffs, where he played whatever sport was in season. “I was the one who usually organized teams. One neighborhood played the other.” He starred at Abraham Lincoln High. While at Southwestern Junior College in Creston, Iowa and at Briar Cliff College in Sioux City, Iowa, he coached junior high ball. “That was my work study program,” he said. At SJC coach Ron Clinton let Chubick and his mates help strategize “how to play teams.” Game-planning and leading got in his blood.

“I don’t know what I’d do if I didn’t work with kids.”

His wife Dianne, who’s seen nearly every high school game he’s coached, said she most admires “the way he can touch kids,” adding, “When they come into his program they’re like his family and he wants the best for every one of them.”

He said his son Joe’s resilience in the face of struggle has affirmed for him that “things are what you make of them.”

Chubick still hungers to coach. “Honest to God we were on the bus after we won the championship headed back to Omaha and before we got out of Lincoln city limits I was thinking about next year. How we’d have to build around Aguek and figure out which players would have to step up.” He said he believes in “that old adage – when you’re through learning, you’re through. That’s true with coaching. You think you know it all, you should quit because you never know it all. I use the analogy that coaching’s like a jigsaw puzzle. You pick up pieces here and there and you try to put the puzzle together. For most coaches, the puzzle’s never complete. I’m not sure mine’s complete.”

His health will determine when he retires. “As long as my health holds up, I don’t think it’s time. Not yet.”

He won’t take it easy in the meantime. “A lot of people go through life and they don’t really live – they just kind of go through the motions. We’ve gotten our money’s worth. We’ve lived.”

Follow his and his team’s viviendo en grande (living large) journey at http://southpackerspride.com/.

Some thoughts on the HBO documentary “My Fight” about Terence Crawford

Terence Crawford: My Fight – Trailer (HBO Boxing)

- on Jun 27, 2016

- 38 views

- Comment

©by Leo Adam Biga

There are sections of contemporary life in this city that most Omahans would rather forget and would certainly do everything to avoid because they represent uncomfortable truths and realities. Terence Crawford’s rise to professional prizefighting’s upper ranks cannot be divorced from where he grew up and from where he still has his heart and continues to have a strong presence. That place is northeast Omaha. The inner city. The Hood. Its tough people and conditions formed and forged him. Rarely if ever is there a screen portrait of that community that goes beyond stereotype or surface. Usually, those screen representations are TV news reports about the aftemath of violent crimes. Over and over again. An exception is the new HBO documentary “My Fight” that profiles Terence in advance of his July 23 title fight with Viktor Postol. It shows an authentic glimpse of the neighborhood and streets, the family and friends he comes from. Not all of northeast Omaha is like what is portrayed. It’s a more diverse landscape than this or any media report paints it to be. But his film gives us a well-rounded look at this man’s life. His routines, his hangouts, his grandmother’s home, his childhood block, his church, his gym, his fishing spot. It’s good for all Omahans to see this film because it does, as much as any one film can, virtually place you there in that community and lifestyle. The psychic-social-cultural-economic-political barriers that continue separating folks are not going away anytime soon but maybe a film like this can at least help put folks there who would never venture there other than maybe for a church mission project. It shows that we’re all just people doing the best that we can. In Terence Crawford, northeast Omaha has a local hero and champion in a way that’s it’s never quite had before. Along the way, as the film makes clear, he’s become Omaha’s hometown champion who is embraced by diverse fans. Perhaps there is more to Terence’s ascendance than we know. Perhaps he can be a unifying figure. He has stayed in Omaha. He remains true to his roots. But at the end of the day he is only one man and this is only one film. Unless and until we can openly, freely and without fear or judgement sit down and break bread together, work together and live together in every part of the city, then a film like this will remain a safe way for people to look with curiosity at how the other half lives and leave it at that. Sadly, that is still how it is in much of Omaha. Maybe just maybe though we can all rally behind Terence and what he wants for his community, which is opportunity and justice.

Northeast Omaha has only been portrayed on film a handful of times. There was “A Time for Burning” Then “Wigger” Now add to the list the new HBO documentary “My Fight” that profiles Terence Crawford in the inner city neighborhood and community that he sprang from and that he still has close ties to. Meet some of the key people in his life. You get a real sense for how things are there and for the people he is a part of. Those conditions and characters made him who he is. Click below to watch the full film, which is produced at a very high level. I have covered Terence for a few years now and my stories touch on just about everything the film does. I even went to Africa with Bud. I accompanied him on one of his two trips to Uganda and Rwanda with Pipeline Worldwide’s Jamie Nollette. I have charted his life story in and out of boxing and I look forward to doing more of this as his journey continues.

Link to my stories about The Champ at–

https://leoadambiga.com/?s=terence+crawford

Come to my July 21 Omaha Press Club Noon Forum presentation Seeing Africa with Terence Crawford and Pipeline–

https://www.facebook.com/events/1019250964856726/

The series and the stadium: CWS and Rosenblatt are home to the Boys of Summer

The College World Series has me all nostalgic for the way things were and by that I mean the CWS and Rosenblatt Stadium enjoying a long-lived marriage as the home to the Boys of Summer. It was a pairing that seemed destined to last decades more. My story here from 1998 appeared at the peak of CWS glory at The Blatt. It was coming on 50 years for this event and venue. But within a decade all the platitudes uttered by the NCAA and others about this match made in heaven began to erode and the business interests and metrics that control big-time college athletics erased any sentiment and moved forward with cold, calculated speed to a new CWS era. The powers that be abandoned Rosenblatt and made plans to develope the new TD Ameritrade ballpark in order to keep the series in Omaha because the Grand Old Lady, as Jack Payne refers to the vintage Blatt, was showing its age and could not accommodate fans in the manner the NCAA demanded. Of course, Omaha had already put put tens of millions of dollars into updating Rosenblatt to keep the series here. The city then spent much more than that again to build a new park to keep the series here. Those who said The Blatt had to go called it a relic and anachronism in an age of expansive stadiums with unobstructed views and wide concourses. There is no doubt that Rosenblatt’s guts were cramped, claustrophobic-inducing and offered limited or nonexistent views of the field from the concourse. Defenders cited the history, legacy, tradition and character of the old park that would be sacrificed, lost and irreplacable in a new venue. We all know what happened. But for a glorious run of more than half a century, The Blatt reigned supreme.

The series and the stadium: CWS and Rosenblatt are home to the Boys of Summer

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Take me out to the ball game,

Take me out with the crowd;

Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack,

I don’t care if I never get back.

Let me root, root, root for the home team,

If they don’t win, it’s a shame.

For it’s one, two, three strikes, you’re out,

At the old ball game.

It’s baseball season again, and The Boys of Summer are haunting diamonds across the land to play this quintessentially American game. One rooted in the past, yet forever new. As a fan put it recently, “With baseball, it’s the same thing all over again, but it isn’t. Do you know what I mean?”

Yes, there’s a timelessness about baseball’s unhurried rhythm, classic symmetry and simple charm. The game is steeped in rules and rituals almost unchanged since the turn of the century. It’s an expression of the American character, both immutable and enigmatic.

Within baseball’s rigid standards, idoosyncracy blooms. A nine-inning contest is decided when 27 outs are recorded and one team is ahead, but getting there can take anywhere from two to four hours or more. All sorts of factors, including weather delays, offensive explosions and multiple pitching changes, can extend a game. An extra inning game results when the two teams are tied after nine stanzas. The number of extra innings is limitless until one team outscores the other after both clubs have had their requisite turns at the plate. There are countless games on record that have gone 10, 11, 12 or more innings, sometimes upwards of 15 to 18 innings and some have even gone beyond these outlier limits to 20 or more innings, when they become true marathon contests of will for players and fans alike. The hours and plays can add up to the point that you can’t remember all the action you just sat through and witnessed.

Stadiums may appear uniform but each has its own personality – with distinctive outfield, dimensions, wind patterns, sight lines, nooks and crannies. Balls play differently and carry differently in each park. The way the infield grass and dirt are maintained differs from park to park. The way the pitcher’s mound and batter’s box are aligned differs, too.

Look in any almost American town and you’ll find a ballpark with deep ties to the sport and its barnstorming, sandlot origins. A shrine, if you will, for serious fans who savor old-time values and traditions. The real thing. Such a place is as near as Omaha’s Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium, the site the past 49 years of the annual College World Series.

The city and the stadium have become synonomous with the NCAA Division I national collegiate baseball championship. No other single location has hosted a major NCAA tournament for so long. More than 4 million fans have attended the event in Omaha since 1950.

This year’s CWS is scheduled for May 29-June 6.

The innocence and the memories

In what has been a troubled era for organized ball, Rosenblatt reaffirms what is good about the game. There, far away from the distraction of Major League free-agency squabbles, the threat of player and umpire strikes, and the posturing of superstars, baseball, in its purest form, takes center stage. Hungry players still hustle and display enthusiasm without making a show of it. Sportsmanship still abounds. Booing is almost never heard during the CWS. Fights are practically taboo.

The action unwinds with lesiurely grace. The”friendly confines” offer the down home appeal of a state fair. Where else but Omaha can the PA announcer ask fans to “scooch in a hair more” and be obliged?

Undoubtedly, the series has been the stadium’s anchor and catalyst. In recent years, thanks in part to ESPN-CBS television coverage, the CWS has become a hugely popular event, regularly setting single game and series attendance records. The undeniable appeal, besides the determination of the players, is a chance to glimpse the game’s upcoming stars. Fans at Rosenblatt have seen scores of future big league greats perform in the tourney, including Mike Schmidt, Dave Winfield, Fred Lynn, Paul Molitor, Jimmy Key, Roger Clemens, Will Clark, Rafael Palmeiro, Albert Belle, Barry Bonds and Barry Larkin.

The stadium on the hill turns 50 this year. As large as the CWS looms in its history, it’s just one part of an impressive baseball lineage. For example, Rosenblatt co-hosted the Japan-USA Collegiate Baseball Championship Series in the ’70s and ’80s, an event that fostered goodwill by matching all-star collegians from each country.

Countless high school and college games have been contested between its lines and still are on occasion.

Pro baseball has played a key role in the stadium’s history as well.

Negro Leagues clubs passed through in its early years. The legendary Satchel Paige pitched there for the Kansas City Monarchs. Major League teams played exhibitions at Rosenblatt in the ’50s and ’60s. St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Famer Stan Musial “killed one” during an exhibition contest.

For all but eight of its 50 years Rosenblatt has hosted a minor league franchise. The Cardinals and Dodgers once based farm clubs there. Native son Hall of Famer Bob Gibson got his start with the Omaha Cardinals in ’57. Since ’69 Rosenblatt’s been home to the Class AAA Omaha Royals, the top farm team of the parent Kansas City Royals. More than 7 million fans have attended Omaha Royals home games. George Brett, Frank White and Willie Wilson apprenticed at the ballpark.

With its rich baseball heritage, Rosenblatt has the imprint of nostalgia all over it. Anyone who’s seen a game there has a favorite memory. The CWS has provided many. For Steve Rosenblatt, whose late father Johnny led the drive to construct the stadium that now bears his name, the early years held special meaning. “The first two years of the series another boy and I had the privilege of being the first bat boys. We did all the games. That was a great thrill because it was the beginning of the series, and to see how it’s grown today is incredible. They draw more people today in one session than they drew for the entire series in its first year or two.”

For Jack Payne, the series’ PA announcer since ’64, “the dominant event took place just a couple years ago when Warren Morris’ two-run homer in the bottom of the ninth won the championship for LSU in ’96. He hit a slider over the right field wall into the bleachers. That was dramatic. Paul Carey of Stanford unloaded a grand slam into the same bleacher area back in ’87 to spark Stanford’s run to the title.”

Jack Payne

Terry Forsberg

Payne, a veteran sports broadcaster who began covering the Rosenblatt beat in ’51, added, “There’s been some great coaching duels out there. Dick Siebert at Minnesota and Rod Dedeaux at USC had a great rivalry. They played chess games out there. As far as players, Dave Winfield was probably the greatest athlete I ever saw in the series. He pitched. He played outfield. He did it all.”

Terry Forsbeg, the former Omaha city events manager under whose watch Rosenblatt was revamped, said, “Part of the appeal of the series is to see a young Dave Winfield or Roger Clemens . Players like that just stick out, and you know they’re going to go somewhere.” For Forsberg, the Creighton Bluejays’ Cinderella-run in the ’91 CWS stands out. “That was a reall thrill, particularly when they won a couple games. You couldn’t ask for anything more.” The Creighton-Wichita State game that series, a breathtaking but ultimately heartbreaking 3-2 loss in 12 innings suffered by CU, is considered an all-time classic.

Creighton’s CWS appearance, the first and only by an in-state school, ignited the Omaha crowd. Scott Sorenson, a right-handed pitcher on that Bluejays squad, will never forget the electric atmosphere. “It was absolutely amazing to be on a hometown team in an event like that and to have an entire city pulling for you,” he said. “I played in a lot of ballparks across the nation, but I never saw anything like I did at Rosenblatt. I still get that tingling feeling whenever I’m back there.”

A game that’s always mentioned is the ’73 USC comeback over Minnesota. The Gophers’ Winfield was overpowering on the mound that night, striking out 15 and hurling a shutout into the ninth with his team ahead 7-0. But a spent Winfield was chased from the mound and the Trojans completed a storybook eight-run last inning rally to win 8-7.

Poignant moments aboud as well. Like the ’64 ceremony renaming the former Municpal Stadium for Johnny Rosenblatt in recognition of his efforts to get the stadium built and bring the CWS to Omaha. A popular ex-mayor. Rosenblatt was forced to resign from office after developing Parkinson’s disease and already suffered from its effects at the rededication. He died in ’79. Another emotional moment came in ’94 when cancer-ridden Arizona State coach Jim Brock died only 10 days after making his final CWS appearance. “That got to me,” Payne said.

Like many others, Payne feels the stadium and tourney are made for each other. “It’s always been a tremendous place to have a tournament, and fortunately there was room to grow. I don’t think you could have picked a finer facility at a better location, centrally located like it is, than Rosenblatt. It’s up high. The field’s big. The stadium’s spacious. It’s just gorgeous. And the people have just kept coming.”

Due to its storied link to the CWS the stadium’s become the unofficial home of collegiate baseball. So much so that CWS boosters like Steve Rosenblatt and legendary ex-USC coach Rod Dedeaux would like to see a college baseball-CWS hall of fame established there.

Baseball is, in fact, why the stadium was built. The lack of a suitable ballpark sparked the formation of a citizens committee in ’44 that pushed for the stadium’s construction. The committee was an earlier version of the recently disbanded Sokol Commission that led the drive for a new convention center-arena. With the goal of putting the issue to a citywide vote, committee members campaigned hard for the stadium at public meetings and in smoke-filled back rooms. Backers got their wish when, in ’45, voters approved by a 3 to 1 margin a $480,000 bond to finance the project.

Unlike the controversy surrounding the site for a convention center-arena today, the 40-acre tract chosen for the stadium was widely endorsed. The weed-strewn hill overlooking Riverview Park (the Henry Doorly Zoo today) was located in a relatively undeveloped area and lay unused itself except as prime rabbit hunting territory. Streetcars ran nearby just as trolleys may in the near future. The site was also dirt cheap. The property had been purchased by the city a few years earlier for $17 at a tax foreclosure sale. Back taxes on the land were soon retired.

Dogged by high bids, rising costs and material delays, the stadium was finished in ’48 only after design features were scaled back and a second bond issue passed. The final cost exceeded $1 million.

Baseball launched the stadium at its October 17, 1948 inaugural when a group of all-stars featuring native Nebraskan big leaguers beat a local Storz Brewery team 11-3 before a packed house of 10,000 fans.

Baseball has continued to be the main drawing card. The growth of the CWS prompted the stadium’s renovation and expansion, which began in earnest in the early ’90s and is ongoing today.

A new look

A new look

Rosenblatt is at once a throwback to a bygone era – with its steel-girded grandstand and concrete concourse – and a testament to New Age theme park design with its Royal Blue molded facade, interlaced metal truss, fancy press box and luxury View Club. The theme park analogy is accentuated by its close proximity to the Henry Doorly Zoo.

Some have suggested the new bigness and brashness have stolen the simple charm from the place.

“Maybe some of that charm’s gone now,” Terry Forsberg said, “but we had to accommodate more people as the CWS got popular. But we still play on real grass under the stars. The setting is still absolutely beautiful. You can still look out over the fences and see what mid-America is all about.”

Jack Payne agrees. “I don’t think it’s taken away from any of the atmosphere or ambience,” he said. “If anything, I think it’s perpetuated it. The Grand Old Lady, as I call it, has weathered many a historical moment. She’s withstood the battle of time. And then in the ’90s she got a facelift, so she’s paid her dues in 50 years. Very much so.”

Perched atop a hill overlooking the Missouri River and the tree-lined zoo, Rosenblatt hearkens back to baseball’s, and by extension, America’s idealized past. It reminds us of our own youthful romps in wide open spaces. Even with the stadium expansion, anywhere you sit gives you the sense you can reach out and touch its field of dreams.

NCAA officials, who’ve practically drawn the blueprint for the new look Rosenblatt, know they have a gem here.

“I think part of the reason why the College World Series will, in 1999, celebrate its 50th year in Omaha is because of the stadium we play in, and the fact that it is a state-of-the-art facility,” said Jim Wright, NCAA director of statistics and media coordinator for the CWS the past 20 years.

Wright believes there is a casual quality that distinguishes the event.

A feeling

A feeling

“Almost without exception writers coming to this event really do become taken with the city, with the stadium and with the laidback way the championship unfolds,” he said. “It has a little bit different feel to it, and certainly part of that is because we’re in Omaha, which has a lot of the big city advantages without having too many of the disadvantages.”

For Dedeaux, who led the Trojans to 10 national titles and still travels from his home in Southern California to attend the series, the marriage of the stadium-city-event makes for a one-of-a-kind experience.

“I love the feeling of it. The intimacy. Whenever I’m there I think of all the ball games but also the fans and the people associated with the tournament, and the real hospitable feeling they’ve always had. I think it’s touched the lives of a lot of people,” he said.

Fans have their own take on what makes baseball and Rosenblatt such a good fit. Among the tribes of fans who throw tailgate parties in the stadium’s south lot is Harold Webster, an Omaha tailored clothing salesman. While he concedes the renovation is “nice,” he notes, “The city didn’t have to make any improvements for me. I was here when it wasn’t so nice. I just love being at the ballpark. I’m here for the game.” Not the frills, he might have added.

For Webster and fans like him, baseball’s a perennial rite of summer. “To me, it’s the greatest thing in the world. I don’t buy season tickets to anything else – just baseball.”

Mark Eveloff, an associate judge in Council Bluffs, comes with his family. “We always have fun because we sit in a large group of people we all know. You get to see a lot of your friends at the game and you get to see some good baseball. I’ve been coming to games here since I was a kid in the late ’50s, when the Omaha Cardinals played. And from then to now, it’s come a long way. Every year it looks better.”

Ginny Tworek is another fan for life. “I’ve been coming out here since I was 8 years-old,” the Baby Boomer said. “My dad used to drop me and my two older brothers off at the ballpark. I just fell in love with the game. It’s a relaxing atmosphere.”

There is a Zen quality to baseball. With its sweet, meandering pace you sometimes swear things are moving in slow motion. It provides an antidote to the hectic pace outside.

Baseball isn’t the whole story at Rosenblatt. Through the ’70s it hosted high school (as Creighton Prep’s home field), college (Omaha University-University of Nebraska at Omaha) and pro football (Omaha Mustangs and NFL exhibition) games as well as pro wrestling cards, boxing matches and soccer contests. Concerts filled the bill, too, including major shows by the Beach Boys in ’64 and ’79. But that’s not all. It accommodated everything from the Ringling Brothers Circus to tractor pulls to political rallies to revival meetings. More recently, Fourth of July fireworks displays have been staged there. Except for the annual fireworks show, the city now reserves the park for none but its one true calling, baseball, as a means of protecting its multimillion dollar investment.

Maintaining excellence

Maintaining excellence

“We made a commitment to the Omaha Royals and to the College World Series and the NCAA that the stadium would be maintained at a Major League level. The new field is farily sensitive. We don’t want to hurt the integrity of the field, so we made the decision to just play baseball there,” Omaha public events manager Larry Lahaie said.

A new $700,000 field was installed in 1991-92, complete with drainage and irrigation systems. Maintaining the field requires a groundskeeping crew whose size rivals that of some big league clubs.

Omaha’s desire to keep the CSW has made the stadium a priority. As the series begain consistenly drawing large crowds in the ’80s, the stadium experienced severe growing pains. Parking was at a premium. Traffic snarls drew loud complaints. To cope with overflow crowds, officials placed fans on the field’s cinder warning track. The growing media corps suffered inside a hot, cramped, outdated press box. With the arrival of national TV coverage in the ’80s, the NCAA began fielding bids from other cities wanting to host the CWS.

In the late ’80s Omaha faced a decision – improve Rosenblatt or lose the CWS. There was also the question of whether the city would retain the Royals. In the ’90s the club’s then owner, Irving “Gus” Cherry, was shopping the franchise around. There was no guarantee a buyer would be found locally, or if one was, whether the franchise would stay. To the rescue came an unlikely troika of Union Pacific Railroad, billionaire investor Warren Buffett and Peter Kiewit Son’s Inc. chairman Walter Scott Jr. , who together purchased the Royals in 1991.

Urged on by local organizers, such as Jack Diesing Sr. and Jr., and emboldened by the Royals new ownership the city anteed-up and started pouring money into Rosenblatt to rehab it according to NCAA specifications. The city has financed the improvements through private donations and from revenue derived from a $2 hotel-motel occupancy tax enacted in ’91.

The Beach Boys in concert at Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha. RUDY SMITH/THE WORLD-HERALD

A carnival or fair atmposphere

The makeover has transformed what was a quaint but antiquated facility into a modern baseball palace. By the time the latest work (to the player clubhouses, public restrooms and south pavilion) is completed next year, more than $20 million will have been spent on improvements.

The stadium itself is now an attraction. The retro exterior is highlighted by an Erector Set-style center truss whose interlocking, cantilevered steel beams, girders and columns jig-jag five stories high.

Then there’s the huge mock baseball mounted on one wall, the decorative blue-white skirt around the facade, the slick script lettering welcoming you there and the fancy View Club perched atop the right-field stands. The coup de grace is the spacious, thatched-roof press box spanning the truss.

Rosenblatt today is a chic symbol of stability and progress in the blue collar South Omaha neighborhood it occupies. It is also a hub of activity that energizes the area. On game days lawn picnics proceed outside homes along 13th Street and tailgate parties unwind in the RV and minivan-choked lots. The aroma of grilled sausage, bratwurst and roasted peanuts fills the air. A line invariably forms at nearby Zesto’s, an eatery famous for its quick comfort food.

There’s a carnival atmosphere inside the stadium. The scoreboard above the left-field stands is like a giant arcade game with its flashing lights, blaring horns, dizzying video displays and fireworks. Music cascades over the crowd – from prerecorded cuts of Queen’s “We Will Rock You” and the Village People’s “YMCA” to organist Lambert Bartak’s live renditions of “Sioux City Sioux” and “Spanish Eyes.” Casey the Mascot dances atop the dugouts. Vendors hawk an assortment of food, drink and souvenirs. Freshly-scrubbed ushers guide you to your seat.

The addition that’s most altered the stadium is the sleek , shiny, glass-enclosed View Club. It boasts a bar, a restaurant, a south deck, a baseball memorabilia collection, cozy chairs and, naturally, a great catbird’s seat for watching the game from any of its three tiered-seating levels.

But you won’t catch serious fans there very long. The hermetically-sealed, soundproof interior sucks the life right out of the game, leaving you a remote voyeur. Removed from the din of the crowd, the ballyhoo of the scoreboard, the enticing scent of fresh air and the sound of a ball connecting with leather, wood or aluminum, you’re cut off from the visceral current running through the grandstand. You miss its goosebump thrills. “That’s the bad thing about it,” Tworek said. “You can’t hear the crack of the bat. You don’t pay as close attention to the game there.”

©Omaha World-Herald

When Rosenblatt was Municipal Stadium. At the first game, from left: Steve Rosenblatt; Rex Barney; Bob Hall, owner of the Omaha Cardinals; Duce Belford, Brooklyn Dodgers scout and Creighton athletic director; Richie Ashburn, a native of Tilden, Neb.; Johnny Rosenblatt; and Johnny Hopp of Hastings, Neb.

Baseball’s internal rhythms bring fans back

Even with all the bells and whistles, baseball still remains the main attraction. The refurbished Rosenblatt has seen CWS crowds go through the roof, reaching an all-time single series high of 204,000 last year. The Royals, bolstered by more aggressive marketing, have drawn 400,000-plus fans every year but one since ’92. Fans have come regardless of the won-loss record. The top single season attendance 447,079 came in ’94, when the club finished eight games under .500 and in 6th place.

Why? Fans come for the game’s inherent elegance, grace and drama. To see a well-turned double play, a masterful pitching performance or a majestic home run. For the chance of snaring a foul ball. For the traditional playing of the national anthem and throwing out of the first pitch. For singing along to you-know-what during the seventh inning stretch.

They come too for the kick back convivality of the park, where getting a tan, watching the sun set or making new friends is part of the bargain. There is a communal spirit to the game and its parks. Larry Hook, a retired firefighter, counts Tworek among his “baseball family,” a group of fans he and his grandson Nick have gotten acquainted with at the Blatt. “It’s become a regular meeting place for us guys and gals,” he said. “We talk a little baseball and watch a little baseball. Once the game’s over everybody goes their separate ways and we say, ‘See ya next home stand.'”

The season’s end brings withdrawl pains. “About the first couple months, I’m lost,” Hook said. “There’s nothing to look forward to.” Except the start of next season.

As dusk fell at Rosenblatt once recent night, Charles and Stephanie Martinez , a father and daughter from Omaha, shared their baseball credo with a visitor to their sanctuary above the third-base dugout. “I can never remember not loving baseball,” said Charles, a retired cop. “I enjoy the competition, the players and the company of the people I’m surrounded by.”

Serious fans like these stay until the final out. “Because anything can happen,” Stephanie said. “I like it because it’s just so relaxed sitting out on a summer day. There’s such an ease to it. Part of it’s also the friends you make at the ballpark. It doesn’t matter where you go – if you sit down with another baseball fan, you can be friends in an instant.”

That familiar welcoming feeling may be baseball’s essential appeal.

Coming to the ballpark, any ballpark, is like a homecoming. Its sense of reunion and renewal, palpable. Rosenblatt only accentuates that feeling.

Like a family inheritance, baseball is passed from one generation to the next. It gets in your blood.

So, take me out to the ball game, take me out to the crowd…

Omaha fight doctor Jack Lewis of two minds about boxing

The visitation will be held on Thursday, June 23, from 4 – 6:30 pm at the Heafey-Hoffmann Dworak & Cutler Bel Air Chapel on 12100 West Center Road. The service will be held on Friday, June 24, at 11 am at the Presbyterian Church of the Cross on 1517 S 114th Street.

Dr. Jack Lewis

Omaha fight doctor Jack Lewis of two minds about boxing as the city readies to host the National Golden Gloves

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

For the first time since 1988, Omaha plays host to the National Golden Gloves boxing tournament, one of the nation’s showcases for amateur boxing. The 2006 tourney is a six-day event scheduled for April 24-29 at two downtown venues. The preliminary and quarterfinal rounds will be fought at the Civic Auditorium the first four days, with the semi-final and championship bouts at the Qwest Center Omaha the final two days.

Historically, the national Golden Gloves has produced scores of Olympic and world champions. Former Gloves greats include Joe Louis, Ezzard Charles, Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, Evander Holyfield and Roy Jones Jr.

Three men with long ties to the local boxing scene recently shared their thoughts on the Gloves with the New Horizons.

The man heading up the event is Omaha’s fight doctor, Dr. Jack Lewis, a 71-year-old internal medicine physician. As a doctor who loves a sport that gets a bad name from the medical community, he’s a paradox. While a staunch supporter of amateur boxing, Lewis is a fierce critic of the professional fight game, which he has come to abhor.

His experience in the prizefighting arena included serving as ringside physician for the 1972 world heavyweight title fight in Omaha between champ Joe Frazier and contender Ron Stander from Council Bluffs. Lewis stopped the fight after the fourth round with a battered Stander blinded by blood in his eyes.

“I love the sport of amateur boxing. I was involved in pro boxing and I didn’t like that from a medical standpoint,” Lewis said. “After just a few years working with the pros, I quit. In some cases, I didn’t know who the fighters were. They were fighting under fake names. I’d ask all these questions and the boxer would say the last time he lost a fight was a month ago in Chicago, and then some guy would come up later and tell me that same guy got knocked out last night in Chicago.

“Those pro boxers move around, have fake names, won’t give you their true medical history.”

Lewis continued, “Those pro boxing days are behind me. That sport needs to be cleaned up.”

More than just a fan of amateur boxing, Lewis is a veteran ringside doctor and longtime president of the Great Plains Boxing Association, the main organizing body for amateur boxing in Nebraska. This is the second time under his leadership his hometown of Omaha is presenting the Golden Gloves nationals.

Lewis is optimistic the event will fare better than recent national Gloves tourneys in cities like Kansas City, where the event failed miserably at the gate.

“We’ve done this before. I think our sales are going very well,” he said.

With Omaha’s success as College World Series host, with the Qwest Center filled to capacity for Creighton University men’s basketball home games, with the arena slated to host a slew of NCAA post-season events over the next several years, plus the U.S. Olympic swimming trials, the Omaha’s known as an amateur sports-friendly town. That’s why there’s talk of Omaha trying to host the Golden Gloves on a regular basis. The event is bid out a few years in advance, so it would be awhile before Omaha could host the event again after 2006.

“Omaha knows how to put people in the seats. Plus, this is really a fight town,” said Harley Cooper of Omaha. The former two-time national Gloves champion is seving as the 2006 tournament director. “It’s an outstanding event, Fans will see the best boxing in the country and probably see some future Olympic and professional champions.”

Omaha boxing historian Tom Lovgren joins many others in calling the Qwest “a great facility for boxing.” “The people there do a superb job,” he added.

While he never boxed, Lewis lettered in football and rugby at Stanford University, backing up future NFL great John Brodie at quarterback in the late 1950s. He said his athletic background and internal medicine specialization “lent itself” to begin treating athletes.

After graduation from Standford and the University of Nebraska Medical School, Lewis did his internal medicine residency in Oakland, California. He came back to Omaha in 1964 to practice with his physician father.

Right away, Lewis’ sports medicine interest found him treating a variety of athletes – jockeys at the Ak-Sar-Ben thoroughbred race track, football players at his alma mater Central high School, where he has been team physician since 1964, and boxers at the Omaha and Midwest Golden Gloves tournaments.

Lewis’ passion for amateur boxing has only grown. He enjoys the purity of the sport. He applauds the protective headgear and other measures taken to ensure fighters’ safety. He believes the competition inside the ropes instills discipline in its participants.

“I think the greatest athlete is the guy that steps in the ring and some guy comes after you. I think it builds character. I think it teaches you resraint. It helps you collect yourself. Through those years I’ve been to many meetings and been to many nationals. I’ve been he ringside physician at hundreds of fights and taken care of a lot of medical problems at the fights. Even though I never fought, I’ve educated myself in boxing and in all the trials and tribulations of the kids.”

Lewis said amateur boxing has suffered unfairly from the ills of its pro counterpart.

“There has been a lot of deaths and those deaths really hurt amateur boxing because then parents don’t want their kids to go into boxing. There’s been a lot of unscrupulous stuff. When I started it was a more popular sport. Today, kids are into doing all kinds of other things. They just don’t go into boxing anymore. And the coaching ranks have really declined. It’s an uphill battle.”

Despite the smaller number of young boxers, Tom Lovgren said “there are kids around that can fight and the Golden Gloves is still a major contributor to the U.S. Olympic boxing team. He said a Gloves title still carries weight in the world of boxing.

“If you are a national Golden Gloves champion, you’re highly respected when you make a turn to the pro ranks.”

Lewis said another thing unchanged in the sport over the years is that ethnic-racial minorities are disproportionately drawn to boxing.

“Our best known boxers in the state now are Latino. There’s been a great influx of Spanish-speaking kids. Unfortunately, many of them don’t have U.S. citizenship and the rules require you to be a citizen in order to compete at nationals (Golden Gloves).”

In the history of the Golden Gloves there have been but five national champions from Nebraska. According to Lovgren, the best of the bunch was Harley Cooper, who won his titles in 1963 and 1964 (the first at heavyweight and the second at light heavyweight). He won those titles when he was in his late 20s. which is much older than the typical Gloves fighter. Since retiring from the ring, Cooper’s devoted time to developing and suporting area amateur boxing. He never turned pro.

“Everybody wanted him to fight for them,” said Lovgran, a former prize fight matchmaker and a longtime observer of the local fight scene. “The first time anybody saw hiim in the gym they knew this guy was going to be a national champion. He could punch. He could box. He could do it all. He was the most complete fighter I ever saw from around here. I never saw Harley Cooper lose a round in amateur fights in Omaha. He was that dominant.”

Besides Cooper, the only other Nebraska boxers crowned national Gloves champions were Carl Vinciquerra and Paul Hartneck in 1936, Hartneck again in ’37, Ferd Hernandez in 1960 and most recently Lamont Kirkland in 1980. A number of other Nebraskans advanced to the semi-finals or finals, only to lose.

In general, Lewis said, area kids are at a distinct disavantage.

“Amateur programs here are not strong. We don’t have enough coaches to train these kids. We don’t have enough fighters to have regular smokers that season them. Every year, our kids go to nationals with maybe 10 to 12 fights under their belt and they face opponents with 70 to 80 fights.”

Harley Cooper said Omaha holding the nationals can only help raise the level of the amateur boxing scene here.

“It wil let our kids see what they have to strive to obtain – the different skills and knowledge they will need to be a world-class boxer. Seeing is much better than someone explaining it to you.”

He added the biggest difference between “our boxers and the fighters from bigger cities is the opponents’ strength, size and skill.”

“It’s going to be a great weekend for amateur boxing in Omaha, Nebraska” Lovgren said. “I just hope a couple of guys from Omaha can go as far as the finals.

A raucous home crowd could help spur a local fighter to do great things.

“It can’t hurt,” Lovgren said. “Who knows? Anything can happen. Boxing’s a funny game.”

“There’s still some kids out there. We should see some real good boxing,” Lewis said.

A final elimination stage before the nationals will be held March 17 and 18 at the Omaha Civic Auditorium’s Mancuso Hall. Winners in this Midwest Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions will complete Nebraska’s 11-man contingent for the April national tourney.

Tickets for the nationals may be purchased at the Qwest Center box office or via Ticketmaster by phone at 402-1212, or online at http://www.ticketmaster.com.

For more details, call the Qwest Center at 997-9378 or go online at http://www.qwestcenteromaha.com.

A Kansas City Royals reflection

A Kansas City Royals reflection

©by Leo Adam Biga

It warms my heart that my Kansas City Royals defy the cold calculations of this digitized, meta-metrics age that’s come to define the way team sports get measured these days. You see, the Royals win in spite of faring poorly in analytic forecasting, and that makes the people for whom these statistical tendencies and barometers truly serve – the gambling industry – mad. KC wins in spite of hitting relatively few home runs, scoring at a less than robust average, getting rare quality starts from its pitchers and lacking even a single superstar on its roster. The Royals win in spite of being a small market franchise with comparatively meager financial resources at its disposal. The Royals win because, well, they are winners and that is not something that can be broken down into data bytes except for wins and losses, divisional finishes, league championships and World Series titles. KC does most all of the little things right that have come to be associated with small ball – manufacturing runs by getting bunts, taking walks, advancing runners, sacrificing, hustling. They also play solid defense at every spot on the diamond and in the outfield. When the Royals are right, they play station to station team ball like no one else in today’s game, though more times than you might imagine they are also capable of keeping the line moving with hit after hit, baserunner after baserunner, enroute to big innings. They put consistent pressure on opponents until foes bend and ultimately break. If the Royals get the lead on you early or if they stay within striking distance late, they have more than enough firepower among their position players and bullpen to close the door and lock up the win or to rally and go ahead, as the situation demands. They may not be a great team in the annals of The Show and in fact these Royals may not even be as strong as the franchise’s glory years teams from 1975 through 1985, but they are consistently excellent four years running now. Should they win another division title and make a third consecutive World Series, then they are firmly in the conversation of a dynasty in our midst. What makes it all so satisfying is that the core of the club is essentially intact during this span and many of the most valuable players on this ride came up together through the KC farm system. Those that were added by trades have been part of the MLB journey to success for the full duration. The Royals may be just one more strong starting pitcher and one more run producer away from writing their ticket to another world title and assuring this bunch a measure of all-time greatness. Best of all, the Roayls are still fairly young and may be looking at another two or three or four or more years of contention. Don’t bother trying to add the numbers up to explain why the Royals are able to do what they do because you can’t quantify grit, energy, determination, desire, camaraderie and teamwork. The Royals are the epitome of guys who come through in the clutch no matter what the stats read. The numbers won’t show you a line for haivng character through advertisity or breaking the will of opponents. Of course, it’s not as if the Royals are without mega talent. The draft and farm system began stockpiling and developing elite prospects going back a decade. It took awhile for the potential to reach maturation and to show results. Each year of this four year run of results has been a different story. The Royals began to live up to their ballyhooed promise in 2013 but still had too many gaps to fill to fully emerge a top tier club. They broke through to the upper echelon and to the post-season in 2014, when they surprised everyone by reaching the World Series. Thet were arguably the better team than the Giants in that W.S. but just couldn’t overcome a certain ace. They were pretty much wire to wire leaders in 2015, when several Royals enjoyed career years, and KC fairly dominated the post season on through to a W.S. title. This season, several of those same players got off to miserable starts. Then came a rash of injuries. Manager Ned Yost and his gang of coaches and his band of brothers players have stayed the course, changed out some parts, and just like the last two years, made true on the next man up credo by plugging in guys who get the job done. So far so good. Two weeks ago or so KC struggled to do much of anything right and seemed in danger of being left out of the race before it began. Now the team has hit its stride and KC finds itself in first place. Nothing is guaranteed with so much season left to go but the team sure has the look of a contender and a champion again. The stats tell you they shouldn’t be doing this but ignore the metrics where the Royals are concerned and go with your heart. That’s what they do and it’s working out just fine.

Bob Boozer, basketball immortal, posthumously inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame

Bob Boozer, basketball immortal, posthumously inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame

I posted this four years ago about Bob Boozer, the best basketball player to ever come out of the state of Nebraska, on the occasion of his death at age 75. Because his playing career happened when college and pro hoops did not have anything like the media presence it has today and because he was overshadowed by some of his contemporaries, he never really got the full credit he deserved. After a stellar career at Omaha Tech High, he was a brilliant three year starter at powerhouse Kansas State, where he was a two-time consensus first-team All-American and still considered one of the four or five best players to ever hit the court for the Wildcats. He averaged a double-double in his 77-game career with 21.9 points and 10.7 rebounds. He played on the first Dream Team, the 1960 U.S. Olympic team that won gold in Rome. He enjoyed a solid NBA journeyman career that twice saw him average a double-double in scoring and rebounding for a season. In two other seasons he averaged more than 20 points a game. In his final season he was the 6th man for the Milwaukee Bucks only NBA title team. He received lots of recognition for his feats during his life and he was a member of multiple halls of fame but the most glaring omisson was his inexplicable exclusion from the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. Well, that neglect is finally being remedied this year when he will be posthumously inducted in November. It is hard to believe that someone who put up the numbers he did on very good KSU teams that won 62 games over three seasons and ended one of those regular seasons ranked No. 1, could have gone this long without inclusion in that hall. But Boozer somehow got lost in the shuffle even though he was clearly one of the greatest collegiate players of all time. Players joining him in this induction class are Mark Aguirre of DePaul, Doug Collins of Illinois State, Lionel Simmons of La Salle, Jamaal Wilkes of UCLA and Dominique Wilkins of Georgia. Good company. For him and them. Too bad Bob didn’t live to see this. If things had worked out they way they should have, he would been inducted years ago and gotten to partake in the ceremony.

I originally wrote this profile of Boozer for my Omaha Black Sports Legends Series: Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. You can access that entire collection at this link–

https://leoadambiga.com/out-to-win-the-roots-of-greatness-…/

I also did one of the last interviws Boozer ever gave when he unexpectedly arrived back stage at the Orpheum Theater in Omaha to visit his good buddy, Bill Cosby, with whom I was in the process of wrapping up an interview. When Boozer came into the dressing room, the photographer and I stayed and we got more of a story than we ever counted on. Here is a link to that piece–

Bill Cosby on his own terms: Backstage with the comedy legend and old friend Bob Boozer

JOHN C. JOHNSON: Standing Tall

None of us is perfect. We all have flaws and defects. We all make mistakes. We all carry baggage. Fairly or unfairly, those who enter the public eye risk having their imperfections revealed to the wider world. That is what happened to one of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends, John C. Johnson, who along with Clayton Bullard, led Omaha Central to back to back state basketball titles in the early 1970s. Both players got Division I scholarships to play ball: Johnson at Creighton and Bullard at Colorado. John C. had a memorable career for the Creighton Bluejays as a small forward who could play inside and outside equally well. He was a hybrid player who could slide and glide in creating his own shot and maneuver to the basket, where he was very adept at finishing, even against bigger opponents, but he could also mix it up when the going got tough or the situation demanded it. He was good both offensively and defensively and he was a fiine team player who never tried to do more than he was capable of and never played outside the system. He was very popular with fans.His biggest following probably came from the North Omaha African-American community he came out of and essentially never left. He was one of their own. That’s not insignificant either because CU has had a paucity of black players from Omaha over its long history. John C. didn’t make it in the NBA but he got right on with his post-collegiate life and did well away from the game and the fame. Years after John C. graduated CU his younger brother Michael followed him from Central to the Hilltop to play for the Jays and he enjoyed a nice run of his own. But when Michael died it broke something deep inside John C. that triggered a drug addction that he supported by committing a series of petty crimes that landed him in trouble with the law. These were the acts of a desperate man in need of help. He had trouble kicking the drug habit and the criminal activity but that doesn’t make him a bad person, only human. None of this should diminish what John C. did on and off the court as a much beloved student-athlete. He is a good man. He is also human and therefore prone to not always getting things right. The same can be said for all of us. It’s just that most of us don’t have our failings written or broadcast for others to see. John was reluctant to be profiled when I interviewed him and his then-life partner for this story about seven or eight years ago. But he did it. He was forthright and remorseful and resolved. After this story appeared there were more setbacks. It happens. Wherever you are, John, I hope you are well. Your story then and now has something to teach all of us. And thanks for the memories of all that gave and have as one of the best ballers in Nebraska history. No one can take that away.

NOTE: This story is one of dozens I have written for a collection I call: Out to Win – The Roots of Greatness: Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. You can find it on my blog, leoadambiga.com. Link to it directly at–

OUT TO WIN – THE ROOTS OF GREATNESS: OMAHA’S BLACK SPORTS LEGENDS

JOHN C. JOHNSON: Standing Tall

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

“I got tired of being tired.”

Omaha hoops legend and former Creighton University star John C. Johnson explained why he ended the pattern of drug abuse, theft and fraud that saw him serve jail and prison time before his release last May.

From a sofa in the living room of the north Omaha home he shares with his wife, Angela , who clung to him during a recent interview, he made no excuses for his actions. He tried, however, to explain his fall from grace and the struggle to reclaim his good name.

“Pancho” or “C,” as he’s called, was reluctant to speak out after what he saw as the media dogging his every arrest, sentencing and parole board hearing. The last thing he wanted was to rehash it all. But as one of the best players Omaha’s ever produced, he’s newsworthy.

“I had a lot of great players,” said his coach at Omaha Central High School, Jim Martin, “but I think ‘C’ surpassed them all. You would have to rate him as one of the top five players I’ve seen locally. He’d be right up there with Fred Hare, Mike McGee, Ron Kellogg, Andre Woolridge, Kerry Trotter… He was a man among boys.”

The boys state basketball championship Central won this past weekend was the school’s first in 31 years. The last ones before that were the 1974 and 1975 titles that Johnson led the Eagles to. Those clubs are considered two of the best in Omaha prep history. In the proceeding 30 years Central sent many fine teams down to Lincoln to compete for the state crown, but always came up short — until this year. It’s that kind of legacy that makes Johnson such an icon.

He’s come to terms with the fact he’s fair game.

“Obscurity is real important to me right now,” Johnson said. “I used to get mad about the stuff written about me, but, hey, it was OK when I was getting the good pub, so I guess you gotta take the good with the bad. Yeah, when I was scoring 25 points and grabbing all those rebounds, it’s beautiful. But when I’m in trouble, it’s not so beautiful.”

As a hometown black hero Johnson was a rarity at Creighton. Despite much hoops talent in the inner city, the small Jesuit school’s had few black players from Omaha in its long history.

There was a rough beauty to his fluid game. It was 40 minutes of hell for opponents, who’d wilt under the pressure of his constant movement, quick feet, long reach and scrappy play. He’d disrupt them. Get inside their heads. At 6-foot-3 he’d impose his will on guys with more height and bulk — but not heart.

“John C.’ s heart and desire were tremendous, and as a result he was a real defensive stopper,” said Randy Eccker, a sports marketing executive who played point guard alongside him at Creighton. “He had a long body and very quick athletic ability and was able to do things normally only much taller players do. He played more like he was [6-foot-6]. On offense he was one of the most skilled finishers I ever played with. When he got a little bit of an edge he was tremendous in finishing and making baskets. But the thing I remember most about John C. is his heart. He’d always step up to make the big plays and he always had a gift for bringing everybody together.”

Creighton’s then-head coach, Tom Apke, calls Johnson “a winner” whose “versatility and intangibles” made him “a terrific player and one of the most unique athletes I ever coached. John could break defenses down off the dribble and that complemented our bigger men,” Apke said. “He had an innate ability on defense. He also anticipated well and worked hard. But most of all he was a very determined defender. He had the attitude that he was not going to let his man take him.”

Johnson took pride in taking on the big dudes. “Here I was playing small forward at [6-foot-three] on the major college level and guarding guys [6-foot-8], and holding my own,” he said in his deep, resonant voice.

When team physician and super fan Lee “Doc” Bevilacqua and assistant coach Tom “Broz” Brosnihan challenged him to clean the boards or to shut down opponents’ big guns, he responded.

He could also score, averaging 14.5 points a game in his four-year career (1975-76, 1978-79) at CU. Always maneuvering for position under the bucket, he snatched offensive rebounds for second-chance points. When not getting put-backs, he slashed inside to draw a foul or get a layup and posted-up smaller men like he did back at Central, when he and Clayton Bullard led the Eagles to consecutive Class A state titles.

He modeled his game after Adrian Dantley, a dominant small forward at Notre Dame and in the NBA. “Yeah, A.D., I liked him,” Johnson said. “He wasn’t the biggest or flashiest player in the world, but he was one of the hardest working players in the league.” The same way A.D. got after it on offense, Johnson ratcheted it up on defense. “I was real feisty,” he said. “When I guarded somebody, hell if he went to the bathroom I was going to follow him and pick him up again at half-court. Even as a freshman at Creighton I was getting all the defensive assignments.”

Unafraid to mix it up, he’d tear into somebody if provoked. Iowa State’s Anthony Parker, a 6-foot-7, high-scoring forward, made the mistake of saying something disparaging about Johnson’s mother in a game.

“When he said something about my mama, that was it,” Johnson said. “I just saw fire and went off on him. Fight’s done, and by halftime I have two or three offensive rebounds and I’m in charge of him. By the end, he’s on the bench with seven points. Afterward, he came in our locker room and I stood up thinking he wanted to settle things. But he said, ‘I’m really sorry. I lost my head. I’m not ever going to say anything about nobody’s mama again. Man, you took me right out of my game.’”

Doing whatever it took — fighting, hustling, hitting a key shot — was Johnson’s way. “That’s just how I approached the game,” he said. He faced some big-time competition, too. He shadowed future NBA all-stars Maurice “Mo” Cheeks, a dynamo with West Texas State College; Mark Aguirre, an All-American with DePaul; and Andrew Toney, a scoring machine with Southwest Louisiana State. A longtime mentor of Johnson’s, Sam Crawford said, “And he was right there with them, too.”

He even had a hand in slowing down Larry Bird. Johnson and company held Larry Legend to seven points below his collegiate career scoring average in five games against Indiana State. The Jays won all three of the schools’ ’77-78 contests, the last (54-52) giving them the Missouri Valley Conference title. But ISU took both meetings in ’78-79, the season Bird led his team to the NCAA finals versus Magic Johnson’s Michigan State.

When “C” didn’t get the playing time he felt he deserved in a late season game his freshman year, Apke got an earful from Johnson’s father and from Don Benning, Central’s then-athletic director and a black sports legend himself. If the community felt one of their own got the shaft, they let the school know about it.

Expectations were high for Johnson — one of two players off those Central title teams, along with Clayton Bullard, to go Division I. His play at Creighton largely met people’s high standards. Even after his NBA stint with the Denver Nuggets, who drafted him in the 7th round, fizzled, he was soon a fixture again here as a Boys and Girls Club staffer and juvenile probation officer. That’s what made his fall shocking.

Friends and family had vouched for him. The late Dan Offenberger, former CU athletic director, said then: “He’s a quality guy who overcame lots of obstacles and got his degree. He’s one of the shining examples of what a young man can accomplish by using athletics to get an education and go on in his work.”

What sent Johnson off the deep end, he said, was the 1988 death of his baby brother and best friend, Michael, who followed him to Creighton to play ball. After being stricken with aplastic anemia, Michael received a bone marrow transplant from “C.” There was high hope for a full recovery, but when Michael’s liver was punctured during a biopsy, he bled to death.

“When he didn’t make it, I kind of took it personally,” Johnson said. “It was a really hard period for our family. It really hurt me. I still have problems with it to this day. That’s when things started happening and spinning out of control.”

He used weed and alcohol and, as with so many addicts, these gateway drugs got him hooked on more serious stuff. He doesn’t care to elaborate. Arrested after his first stealing binge, Johnson waived his right to a trial and admitted his offenses. He pleaded no contest and offered restitution to his victims.

His first arrests came in 1992 for a string of car break-ins and forgeries to support his drug habit. He was originally arrested for theft, violation of a financial transaction device, two counts of theft by receiving stolen propperty and two counts of criminal mischief. His crimes typically involved a woman accomplice with a fake I.D. Using stolen checks and credit cards, they would write a check to the fake name and cash it soon thereafter. He faced misdemanor and felony charges in Harrison County Court in Iowa and misdemeanor charges in Douglas County. He was convicted and by March 2003 he’d served about eight years behind bars.

He was released and arrested again. In March 2003 he was denied parole for failing to complete an intensive drug treatment program. Johnson argued, unsuccessfully, that his not completing the program was the result of an official oversight that failed to place his name on a waiting list, resulting in him never being notified that he could start the program.

Ironically, a member of the Nebraska Board of Parole who heard Johnson’s appeal is another former Omaha basketball legend — Bob Boozer, a star at Technical High School, an All-American at Kansas State and a member of the 1960 U.S. Olympic gold medal winning Dream Team and the 1971 Milwaukee Bucks NBA title team. Where Johnson’s life got derailed and reputation sullied, Boozer’s never had scandal tarnish his name.

After getting out on in the fall of 2003, Johnson was arrested again for similar crimes as before. The arrest came soon after he and other CU basketball greats were honored at the Bluejays’ dedication of the Qwest Center Omaha. He only completed his last stretch in May 2005. His total time served was about 10 years.

He ended up back inside more than once, he said, because “I wasn’t ready to quit.” Now he just wants to put his public mistakes behind him.

What Johnson calls “the Creighton family” has stood by him. When he joined other program greats at the Jays’ Nov. 22, 2003 dedication of the Qwest Center, the warm ovation he received moved him. He’s a regular again at the school’s old hilltop gym, where he and his buds play pickup games versus 25-year-old son Keenan and crew. He feels welcome there. For the record, he said, the old guys regularly “whup” the kids.

“It feels good to be part of the Creighton family again. They’re so happy for me. It’s kind of made me feel wanted again,” he said.

Sam Crawford, a former Creighton administrator and an active member of the CU family, said, “I don’t think we’ll ever give up on John C., because he gave so much of himself while he was there. If there’s any regret, it’s that we didn’t see it [drug abuse] coming.” Crawford was part of a contingent that helped recruit Johnson to CU, which wanted “C” so bad they sent one of the school’s all-time greats, Paul Silas, to his family’s house to help persuade him to come.

Angela, whom “C” married in 2004, convinced him to share his story. “I told him, ‘You really need to preserve the Johnson legacy — through the great times, your brief moment of insanity and then your regaining who you are and your whole person,’” she said. Like anyone who’s been down a hard road, Johnson’s been changed by the journey. Gone is what’s he calls the “attitude of indifference” that kept him hooked on junk and enabled the crime sprees that supported his habit. “I’ve got a new perspective,” he said. “My decision-making is different. It’s been almost six years since I’ve used. I’m in a different relationship.

Having a good time used to mean getting high. Not anymore. Life behind “the razor wire” finally scared him straight. ”They made me a believer. The penal system made me a believer that every time I break the law the chances of my getting incarcerated get greater and greater. All this time I’ve done, I can’t recoup. It’s lost time. Sitting in there, you miss events. Like my sister had a retirement party I couldn’t go to. My mother’s getting up in age, and I was scared there would be a death in the family and I’d have to come to the funeral in handcuffs and shackles. My son’s just become a father and I wouldn’t wanted to have missed that. Missing stuff like that scared the hell out of me.”

Johnson’s rep is everything. He wants it known what he did was out of character. That part of his past does not define him. “I’ve done some bad things, but I’m still a good person. You’ll find very few people that have anything bad to say about me personally,” he said. “You’ll mostly find sympathy, which I hate.” But he knows some perceive him negatively. “I don’t know if I’m getting that licked yet. If I don’t, it’s OK. I can’t do anything about that.”

He takes full responsibility for his crimes and is visibly upset when he talks about doing time with the likes of rapists and child molesters. “I own up to what I did,” he said. “I deserved to go to prison. I was out of control. But as much trouble as I’ve been in, I’ve never been violent. I never touched violence. The only fights I’ve had have been on the basketball court, in the heat of battle.”

He filled jobs in recent years via the correction system’s work release program. Shortly before regaining his freedom in May, he faced the hard reality any ex-con does of finding long-term work with a felony conviction haunting him. When he’d get to the part of an application asking, “Have you ever been convicted of a felony?” — he’d check, yes. Where it said, “Please explain,” he’d write in the box, “Will explain in the interview.” Only he rarely got the chance to tell his story.

Then his luck changed. Drake Williams Steel Company of Omaha saw the man and not the record and hired him to work the night shift on its production line. “I really appreciate them giving me an opportunity, because they didn’t have to. A lot of places wouldn’t. And to be perfectly honest, I understand that. This company is employee-oriented, and they like me. They’re letting me learn things.”

He isn’t used to the blue-collar grind. “All my jobs have been sitting behind a desk, pretty much. Now I’m doing manual labor, and it’s hard work. I’m scratched up. I work on a hydro saw. I weld. I operate an overhead crane that moves 3,000-pound steel beams. I’m a machine operator, a drill operator…”

The hard work has brought Johnson full circle with the legacy of his late father, Jesse Johnson, an Okie and ex-Golden Gloves boxer who migrated north to work the packing houses. “My father was a hard working man,” he said. “He worked two full-time jobs to support us. We didn’t have everything but we had what we needed. I’ve been around elite athletes, but my father, he was the strongest man I’ve ever known, physically, emotionally and mentally. He didn’t get past the 8th grade, but he was very well read, very smart.”

His pops was stern but loving. Johnson also has a knack with young people — he’s on good terms with his children from his first marriage, Keenan and Jessica — and aspires one day to work again with “kids on the edge.”

“I shine around kids,” he said. “I can talk to them at their level. I listen. There’s very few things a kid can talk about that I wouldn’t be able to relate to. I just hope I didn’t burn too many bridges. I would hate to think my life would end without ever being able to work with kids again. That’s one of my biggest fears. I really liked the Boys Club and the probation work I did, and I really miss that.”

He still has a way with kids. Johnson and a teammate from those ’74 and ’75 Central High state title teams spoke to the ‘05-’06 Central squad before the title game tipped off last Saturday. “C” told the kids that the press clippings from those championship years were getting awfully yellow in the school trophy case and that it was about time Central won itself a new title and a fresh set of clippings. He let them know that school and inner city pride were on the line.

He’s put out feelers with youth service agencies, hoping someone gives him a chance to . For now though he’s a steel worker who keeps a low profile. He loves talking sports with the guys at the barbershop and cafe. He works out. He plays hoops. Away from prying eyes, he visits Michael’s grave, telling him he’s sorry for what happened and swearing he won’t go back to the life that led to the pen. Meanwhile, those dearest to Johnson watch and wait. They pray he can resist the old temptations.

Crawford, whom Johnson calls “godfather,” has known him 35 years. He’s one of the lifelines “C” uses when things get hairy. “I know pretty much where he is at all times. I’m always reaching out for him … because I know it is not easy what he’s trying to do. He dug that hole himself and he knows he’s got to do what’s necessary. He’s got to show that he’s capable of changing and putting his life back together. He’s got to find the confidence and the courage and the faith to make the right choices. It’s going to take his friends and family to encourage him and provide whatever support they possibly can. But he’s a good man and he has a big heart.”

Johnson is adamant his using days are over and secure that his close family and tight friends have his back. “Today, my friends and I can just sit around and have a good time, talking and laughing, and it doesn’t have nothing to do with drugs or alcohol. There used to be a time for me you wouldn’t think that would be possible. I still see people in that lifestyle and I just pray for them.”

Besides, he said, “I’m tired of being tired.”

Marlin Briscoe – An Appreciation

Marlin Briscoe – An Appreciation

©by Leo Adam Biga

Some thoughts about Marlin Briscoe in the year that he is:

•being inducted in the College Football Hall of Fame

•having a life-size status of his likeness dedicated at UNO

•and seeing a feature film about himself going into production this fall

For years, Marlin Briscoe never quite got his due nationally or even locally. Sure, he got props for being a brilliant improviser at Omaha U. but that was small college ball far off most people’s radar. Even fewer folks saw him star before college for the Omaha South High Packers. Yes, he got mentioned as being the first black quarterback in the NFL, but it took two or three decades after he retired from the game for that distinction to sink in and to resonate with contemporary players, coaches, fans and journalists. It really wasn’t until his autobiography came out that the significance of that achievement was duly noted and appreciated. Helping make the case were then-current NFL black quarterbacks, led by Warren Moon, who credited Briscoe for making their opportunity possible by breaking that barrier and overturning race bias concerning the quarterback position. Of course, the sad irony of it all is that Briscoe only got his chance to make history as a last resort by the Denver Broncos, who succumbed to public pressure after their other quarterbacks failed miserably or got injured. And then even after Briscoe proved he could play the position better than anyone else on the squad, he was never given another chance to play QB with the Broncos or any other team. He was still the victim of old attitudes and perceptions, which have not entirely gone away by the way, that blacks don’t have the mental acuity to run a pro-style offensive system or that they are naturally scramblers and not pocket passers or that they are better with their feet and their athleticism than they are with their arms or their head. Briscoe heard it all, and in his case he also heard that he was too small.