Archive

Combat sniper-turned-art photographer Jim Hendrickson on his vagabond life and enigmatic work

Another of the unforgettable characters I have met in the course of my writing life is the subject of this story for The Reader (www.thereader.com). Jim Hendrickson is a Vietnam combat vet who went from looking through the scope of a rifle as a sniper in-country to looking through the lens of a camera as an art photographer after the war. His story would make a good book or movie, which I can honestly say about a number of people I have profiled through the years. But there is a visceral, cinematic quality to Jim’s story that I think sets it apart and will be readily apparent to you as you read it.

Combat sniper-turned-art photographer Jim Hendrickson on his vagabond life and enigmatic work

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

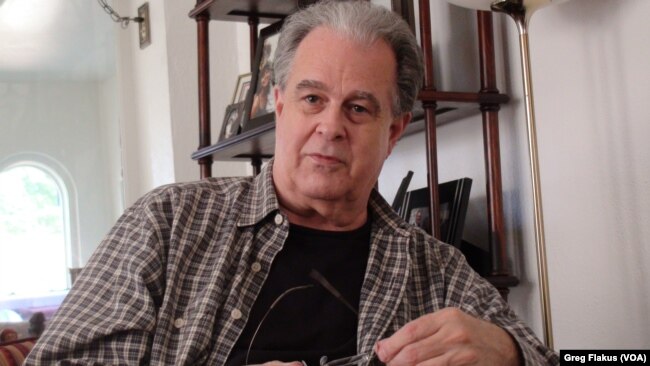

Combat sniper-turned-art photographer Jim Hendrickson is one of those odd Omaha Old Market denizens worth knowing. The Vietnam War veteran bears a prosthetic device in place of the right arm that was blown-off in a 1968 rocket attack. His prosthetic ends in pincer-like hooks he uses to handle his camera, which he trains on subjects far removed from violence, including Japanese Butoh dancers. Known by some as “the one-armed photographer,” he is far more than that. He is a fine artist, a wry raconteur and a serious student in the ways of the warrior. Typical of his irreverent wit, he bills himself as — One Hand Clapping Productions.

The Purple Heart recipient well-appreciates the irony of having gone from using a high-powered rifle for delivering death to using a high-speed camera for affirming life. Perhaps it is sweet justice that the sharp eye he once trained on enemy prey is today applied in service of beauty. For Hendrickson, a draftee who hated the war but served his country when called, Vietnam was a crucible he survived and a counterpoint for the life he’s lived since. Although he would prefer forgetting the war, the California native knows the journey he’s taken from Nam to Nebraska has shaped him into a monument of pain and whimsy.

Jim Hendrickson

His pale white face resembles a plaster bust with the unfinished lines, ridges and scars impressed upon it. The right side — shattered by rocket fragments and rebuilt during many operations — has the irregularity of a melted wax figure. His collapsed right eye socket narrows into a slit from which his blue orb searches for a clear field of vision. His massive head, crowned by a blond crew cut, is a heavy, sculptured rectangle that juts above his thick torso ala a Mount Rushmore relief. Despite his appearance, he has a way of melding into the background (at least until his big bass voice erupts) that makes him more spectator than spectacle. This knack for insinuating himself into a scene is something he learned in the Army, first as a guard protecting VIPs and later as a sniper hunting enemy targets. He’s refined this skill of sizing-up and dissecting a subject via intense study of Japanese samurai-sword traditions, part of a fascination he has with Asian culture.

Because his wartime experience forever altered his looks and the way he looks at things, it’s no surprise the images he makes are concerned with revealing primal human emotions. One image captures the anxiety of a newly homeless young pregnant woman smoking a cigarette to ward off the chill and despair on a cold gray day. Another portrays the sadness of an AIDS-stricken gay man resigned to taking the train home to die with his family. Yet another frames the attentive compassion of an old priest adept at making those seeking his counsel feel like they have an unconditional friend.

The close observation demanded by his work is a carryover from Vietnam, where he served two tours of duty. “With sniping, you had to look at the lay of the land. You had to start looking from the widest spectrum and then slowly narrow it down to that one spot and one moment of the kill,” he said. “You got to the point where you forced yourself to look at every detail and now, of course, I’m doing that today when I photograph. I watch the person…how they move, how they hold themselves, how they talk, waiting for that moment to shoot.”

Shooting, of a photographic kind, has fascinated him from childhood, when he snapped pics with an old camera his Merchant Marine father gave him. He continued taking photos during his wartime tours. Classified a Specialist Four wireman attached to B-Battery, 1st Battalion, I-Corp, Hendrickson’s official service record makes no mention of his actual duty. He said the omission is due to the fact his unit participated in black-op incursions from the DMZ to the Delta and into Cambodia and Laos. Some operations, he said, were conducted alongside CIA field agents and amounted to assassinations of suspected Vietcong sympathizers.

As a sniper, he undertook two basic missions. On one, he would try spotting the enemy — usually a VC sniper — from a far-off, concealed position, whereupon he would make “a long bow” shot. “I was attached to field artillery units whose artillery pieces looked like over-sized tanks. The pieces had a telescope inside and what I would do is sit inside this glorified tank and I would rotate the turret looking through the telescope, looking for that one thing that would say where the Vietcong sniper was, whether it was sighting the sniper himself or some kind of movement or just something that didn’t belong there. I’d pop the top hatch off, stand up on a box and then fire my weapon — a bolt-action 30-ought-6 with a 4-power scope — at the object. Sometimes, I’d fire into a bunch of leaves and there’d be nothing there and sometimes there was somebody there.” When the target couldn’t be spotted from afar, he infiltrated the bush, camouflaged and crawling, to “hunt him down.” Finding his adversary before being found out himself meant playing a deadly cat-and-mouse game.

©Images by Jim Hendrickson

“You look at where he’s firing from to get a fix on where he’s holed up and then you come around behind or from the side. You move through the bush as quietly as possible, knowing every step, and even the smell of the soap you wash with, can betray you. I remember at least three times when I thought I was going to die because the guy was too good. It’s kind of a like a chess match in some sense. At some point, somebody makes a mistake and they pay for it. I remember sitting in a concealed location for like three days straight because only a few yards away was my opponent, and he knew where I was. If I had gone out of that location, he would have shot me dead. So, for three days I skulked and sat and waited for a moonless night and then I slipped out, came around behind him — while he was still looking at where I was — and killed him.”

His first kill came on patrol when assigned as a replacement to an infantry unit. “I was the point man about 50 feet ahead of the unit. I heard firing behind me and, so, I turned to run back to where the others were when this figure suddenly popped up in front of me. I just reacted and fired my M-16 right from the hip. I got three shots into the figure as I ran by to rejoin the patrol. The fire fight only lasted two or three minutes, By then, the Vietcong had pulled back. The captain asked us to go out and look for papers on the dead bodies. That first kill turned out to be a young woman of around 16. It was kind of a shock to see that. It taught me something about the resolve the Vietcong had. I mean, they were willing to give up their children for this battle, where we had children trying to evade the draft.”

As unpopular as the war was at home, its controversial conduct in-country produced strife among U.S. ground forces.

“Officers were only in the field for six months,” Hendrickson said, “but enlisted men were stuck out there for a year. We knew more about what was happening in the field than they did. A lot of times you’d get a green guy just out of officers’ school and he’d make some dumb mistake that put you in harm’s way. We had an open rebellion within many units. There was officer’s country and then there was enlisted men’s country.”

In this climate, fragging — the killing of officers by grunts — was a well-known practice. “Oh, yes, fragging happened quite a lot,” he said. “You pulled a grenade pin, threw the grenade over to where the guy was and the fragments killed him.” Hendrickson admits to fragging two CIA agents, whom he claims he took-out in retribution for actions that resulted in the deaths of some buddies. The first time, he said, an agent’s incompetence gave away the position of two fellow snipers, who were picked-off by the enemy. He fragged the culprit with a grenade. The second time, he said, an agent called-in a B-52 strike on an enemy position even though a friendly was still in the area.

“I walked over to the agent’s hootch (bunker), I called him out and I shot three shots into his chest with a .45 automatic. He fell back into the hootch. And just to let everybody know I meant business I threw a grenade into the bunker and it incinerated him. Everybody in that unit just quietly stood and looked at me. I said, ‘If you ever mess with me, you’ll get this.’ Nobody ever made a report. It went down as a mysterious Vietcong action.”

He was early into his second tour when he found himself stationed with a 155-Howitzer artillery unit. “We were on the top of a gentle hill overlooking this valley. I was working the communications switchboard in a bunker. I was on duty at two or three in the morning when I started hearing these thumps outside. I put my head up and I saw explosions around our unit. Well, just then the switchboard starts lighting up.”

In what he said was “a metaphor” for how the war got bogged down in minutiae, officers engaged in absurd chain-of-command proprieties instead of repelling the attack. “Hell, these Albert Einsteins didn’t even know where their own rifles were,” he said, bellowing with laughter. What happened next was no laughing matter. In what was the last time he volunteered for anything, he snuck outside, crossed a clearing and extracted two wounded soldiers trapped inside a radio truck parked next to a burning fuel truck.

“First, I started up the fuel truck, put the self-throttle on, got it moving out of the unit and jumped out. Then I went back and helped the wounded out of their truck and got them back to where the medics were. Then, another guy and I were ‘volunteered’ to put a 60-caliber machine gun on the perimeter fence. We were on the perimeter’s edge…when I saw a great flash. A Russian-made 122-millimeter rocket exploded. The man behind me died instantly. The only thing I remember is the sense of flying.” Hendrickson’s right arm and much of the right side of his face was shredded off.

As he later learned, a battalion of Vietcong over-ran a company of Australians stationed on the other side of the hilltop and attacked his unit “in a human wave.” He said, “They ran right by me, thinking I was dead, probably because of all the blood on me.” The attack was knocked-back enough to allow for his rescue.

“I remember starting to come around as my sergeant yelled at me…I heard an extremely loud ringing noise in my ears. I knew something was extremely wrong with my right arm, but I didn’t know what. I couldn’t really see anything because my eyes were swollen shut from the fragments in my face. About that time the medic came along. They put me on a stretcher and pulled me back to a hold. That’s when I was told my right arm was blown off.

“I was just thankful to be alive at that point. Then, the rockets started coming in again and people were running around getting ready for the next human wave attack. I was lying there with the two guys I’d saved. Then I saw this big bright light in the pitch black. It was a chopper coming in to pick us up. The medics carried us up, threw us in and the pilot took off. As we lifted, I could hear bullets ripping through the chopper. We were taken to the nearest hospital, in Long Binh, about 50 miles away.”

While recuperating, Hendrickson was informed by his captain that of the 100-plus-man strong unit, there were only five survivors – the captain, Hendrickson, along with the two men he saved, plus one other man. “Apparently,” Hendrickson said, “the unit had been hit by a combination of rocket and human wave attacks that night and the day after and were eventually wiped off the earth. Years later, the historians said this was a ‘retreating action’ by the Vietcong. If this was a retreating action, I sure as heck would hate to see it when they were serious and advancing.” He said his fellow survivors are all dead now. “Those are four people whose names should be on that wall in Washington. Unfortunately, they’ll never be recognized as casualties of war, but yet they are casualties OF THE war.”

He spent the next several months in and out of hospitals, including facilities in Japan, before undergoing a series of operations at Letterman Hospital in the Presidio of San Francisco. Afterwards, he said, he entered “a wandering period…trying to find myself.” He made his home in Frisco, becoming a lost soul amid the psychedelic searchers of the Haight-Ashbury district. “I tried to resume a life of somewhat normalness, but it was like a whole separate reality.” He enrolled in City College-San Francisco, where he once again felt out of place.

Disillusioned and directionless, he then came under the guidance of a noted instructor and photographer — the late Morrie Camhi. “Morrie made that connection with me and started me on a pathway of using photography as a kind of therapy. It was a really great relationship that evolved…He became like a second father.” Years of self-discovery followed. Along the way, Hendrickson earned a master of fine arts degree from the San Francisco Art Institute, married a woman with whom he got involved in the anti-war and black power movements and, following years of therapy in storefront VA counseling centers, overcame the alcohol abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder he suffered from after the war. While his marriage did not last, he found success, first as a commercial artist, doing Victoria’s Secret spreads, and later as an art photographer with a special emphasis on dance.

Morrie Camhi

Helping him find himself as an artist and as a man has been an individual he calls “my teacher” — Sensie Gene Takahachi, a Japanese sword master and calligrapher in the samurai tradition. Hendrickson, who has studied in Japan, said his explorations have been an attempt to “find a correlation or justification for what happened to me in Vietnam. I studied the art of war…from the samurai on up to the World War II Zero-pilot. I studied not only the sword, but the man behind the sword. In the Japanese philosophy of the sword it’s how you make the cut that defines the man you are and the man you’re up against.” He said this, along with the minimalist nature of Haiku poetry and calligraphy, has influenced his own work.

“I try to do the same thing in my photography. I try to strip down a subject to the most essential, emotional image I can project.” He has applied this approach to his enigmatic “Haiku” portraits, in which he overlays and transfers multiple Polaroid images of a subject on to rice paper to create a mysterious and ethereal mosaic. While there is a precision to his craft, he has also opened his work up to “more accidents, chaos and play” in order to tap “the child within him.” For him, the act of shooting is a regenerative process. “When I shoot — I empty myself, but everything keeps coming back in,” he said.

A self-described “vagabond” who’s traveled across the U.S. and Europe, he first came to Omaha in 1992 for a residency at the Bemis Center for the Contemporary Arts. A second Bemis residency followed. Finding he “kept always coming back here,” he finally moved to Omaha. An Old Market devotee, he can often be found hanging with the smart set at La Buvette. Feeling the itch to venture again, he recently traveled to Cuba and is planning late summer sojourns to Havana and Paris. Although he’s contemplating leaving Omaha, he’s sure he’ll return here one day. It is all part of his never-ending journey.

“I see photography as a constant journey and one that has no end until the day I can’t pick-up a camera anymore,” he said.

Related Articles

- How Snipers Succeed by Missing Their Targets (theqco.com)

- In the shadow of Vietnam: A close encounter with Karl Marlantes, US marine turned literary giant (independent.co.uk)

- Full Metal Jacket: history unzipped (guardian.co.uk)

- Darpa’s Super Sniper Scopes in Shooters’ Hands by 2011 (wired.com)

- Snipers targeting children in key Libyan city: UN (cbc.ca)

Bill Ramsey, Marine: A Korean War Story

Journalists look for hooks to hang their stories on, and anniversaries of major events are always convenient pegs to use. On the 50th anniversary of the Korean War I profiled the combat experience of Bill Ramsey, an amiable man who made a rich life for himself after the conflict as a husband, father, PR professional, and community volunteer. He has devoted much of his life to veterans affairs, particularly memorializing fallen veterans. He’s also authored a handful of books. He’s still quite active today at age 80. Anyone who survives combat has a story worth repeating, and it was my privilege telling his story in the New Horizons. Now, in conjunction with the 60th anniversary of the Korean War, I offer the story again as a tribute to Ramsey and his fellow servicemen who fought this often forgotten conflict.

Bill Ramsey, Marine: A Korean War Story

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Fifty years ago, Americans were piecing their lives back together in the aftermath of World War II when the best and brightest of the nation’s youth were once more sent-off to fight in a distant land. This time the call to arms came in defense of a small Asian nation few Americans were even aware of then — Korea. In June of 1950, Communist North Korean forces (with backing from the Soviet Union and Red China) launched an unprovoked attack on the fledgling democratic republic of South Korea, whose poorly prepared army was soon overrun. With North Korea on the verge of conquering their neighbors to the south, the United States and its Western allies drew a line in the sand against Communist expansionism in the strategically vital Far East and led a United Nations force to check the aggression.

Among those answering the call to service was a tall, strapping 20-year-old Marine reservist from Council Bluffs named Bill Ramsey. His wartime experience there became a crucible that indelibly marked him. “The war will always be the most defining experience in my life,” said Ramsey, 70, whose full postwar years have included careers as a newsman, advertising executive and public relations consultant. He and his wife of 46 years, Pat, raised five children and are grandparents to 14 and great-grandparents to one. This is his Korean War story.

In the fall of 1950, Ramsey was preparing to study journalism at then Omaha University. His plans were put on hold, however, with the outbreak of hostilities overseas. He followed the unfolding drama in newsreel and newspaper accounts, including the U.S. rushing-in army divisions grown soft from occupation duty in defeated Japan. The invaders pushed South Korean and American forces down the Korean peninsula. Ramsey sensed reserves might be recalled to active duty. He was right.

He was assigned a front line unit in the 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, Reinforced. He was excited at the prospect of seeing action in a real shooting war, even one misleadingly termed “a police action.” His anticipation was fed not by bravery, but rather heady youthful zeal to be part of the Corps’ glorious tradition. The conflict offered a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to test himself under fire. After all, he was too young to have fought in his older brother Jack’s war the previous decade. This would be his war. His proving ground. His adventure.

“I wanted to be in the front lines. I didn’t want to go all that way to end up sorting letters in Pusan,” he said. “I was curious to know how I would hold up in action.”

No stirring salute or fanfare saw the Marines off as their Navy attack transport ship, Thomas Jefferson, pulled out of San Diego harbor in March 1951. Ramsey was one of hundreds of young men crammed in the hull. They had been plucked away from factories, offices, schools, homes and families. Ramsey left behind his mother, brother and an aunt (his father died when he was 12). The GIs were going to defend a land they did not know and a people they never met. Their mission lacked the patriotic fervor of WWII. There was no Pearl Harbor to avenge this time. No, this was a freedom fight in a growing global struggle for people’s hearts and minds.

Bill Ramsey

Before ever setting foot on Korean soil, Ramsey smelled it from aboard ship in the Sea of Japan. Nearing Pusan harbor in the far southeastern tip of Korea, the heavy acrid odor of the war-ravaged countryside permeated the air. It was the stink of sulfur (the discharge from spent armaments), excrement (peasant farmers used it as fertilizer in their fields), fire and death. “That all mixed together made for quite a pungent odor,” he said. “It’s a stench that you never forget.”

Ramsey and his Able Company comrades were flown into a staging area near Chunchon in east-central Korea to await transport to the front. The city had sustained heavy damage. “It was pretty well leveled at that point,” he recalls. Standing on a wind-swept tarmac, he saw snaking down a road from the north a convoy of trucks carrying combat-weary GIs being rotated out of the line. These were veterans of the famous Chosin Reservoir Battle who defied all odds, including numerically superior enemy forces, to complete a withdrawal action that featured hand-to-hand combat. Ramsey and his green mates were their replacements.

“I remember when they got off the trucks they looked like zombies. Their faces were covered with a fine white powdery dust and their hands were blackened from the soot of the fires burning everywhere in the country,” Ramsey said. “I thought, ‘God, I’d give anything to have gone through what they’ve gone through and to be going home.” Among the dog-faced vets was a friend, Phil O’Neill, from Council Bluffs. “He tried to tell me what it was like. He didn’t exaggerate or try to make it any scarier than it was. He didn’t fool around or joke. He just gave me some good advice, like keep a low profile and keep your weapon dry.” After seeing and hearing what awaited him, Ramsey felt an overpowering desire to join the departing GIs. “They were going home. That really hurt. I was so envious.”

Ramsey’s unit headed for a position along the central front. Every village and field they passed was scarred and charred. “We drove all night. We could see fires burning. Again, we could smell the countryside,” he said.

Movement was the order of the day in a war of quickly shifting positions along the long and narrow Korean peninsula. “It was a very fluid war. We were moving constantly, sometimes by truck and sometimes marching 20 or 30 miles in a day to the next spot,” he said. Rough mountainous terrain, bad roads and inclement weather — marked by extreme temperatures, torrential rains, floods, snow and ice — made the going tough. “The farther north you go the more mountainous it becomes. You always had to go up a hill or some rocky face. No flat open fields. This was trees and rocks and cliffs. A really difficult place.” While he never had to endure the brutal winter, he described conditions “as miserably cold. And when it rained, which it did a lot, you were soaking wet, cold and knee-deep in mud. You thought you could never get through it, but you kept going.”

When his company first arrived, U.N. forces were striking out in a series of bold counteroffensives. By the summer, the war was bogged down in a stalemate. A single position (invariably a hill) would be taken, lost, and retaken several times. “It was pretty much hill by hill,” Ramsey said. Platoons were like firefighters rushing from one hot zone to another. A hundred yards or less might separate opposing forces. The basic objective was usually capturing or holding a perimeter on one of the endless sharp-edged ridge lines. Upon reaching a position, the Marines set-up machine gun posts and prepared cover by digging fox holes. Not only did the metal shards from incoming mortar and artillery pose threats, but splintered rock made deadly projectiles too. “

You always had to get some protection for yourself from shrapnel,” he said. Sleeping accommodations were standard-issue pup tents or makeshift bunkers (for extended stays). “Most of the time you stayed one night or two nights and then walked to another position, where you’d dig another hole.” The premium was on moving — no matter what. “You have aching feet. A sore back. You’re tired, discouraged. You’re cold, dirty. You’re sick (dysentery, encephalitis, etc.). But you can’t stop. You’re there, you’re on the move and there’s no way out unless a doctor says you just can’t go on and sends you to the rear.”

On rare occasions when his platoon remained in one spot, barbed wire was strung across the perimeter. The men had to be on constant alert for all-out charges or smaller probing raids looking for weaknesses in the line. “A lot of times they were through the position or in the position. They weren’t always stopped at the wire,” Ramsey said. Nightfall was the worst. The enemy preferred attacking then by frontal assault or flanking maneuvers. To keep a sharp defensive perimeter, men took turns sleeping and watching — two hours on and two hours off — through the night. “You never let your guard down. We were always ready,” he said, adding that the last two years of the conflict it got to be “almost like trench warfare.”

His first taste of combat came early in his hitch. His platoon was dug in for the night on some anonymous ridge line, the men extra wary because reconnaissance had spotted enemy massed nearby. “We were told the Chinese were going to be coming in some force. It was pretty hard to sleep anyway, and anticipating my first night under fire made it that much harder. Sure enough, they came that night. I remember a lot of noise. Mortars. Shots. All that firepower. I remember thinking, “I would love to be able to cram myself inside my helmet.” I somehow got through that night. The next morning they brought in some of our killed. They were in ponchos — their feet sticking out. They were carried down the hill.”

Sometimes, a noise from somewhere out in the pitch black warned of encroaching danger. Other times, a fire fight broke loose with no warning at all. “You would hear something or you would sense something. You laid down fire if you heard anything at all out there. Their movements might trigger a flare, which made it easier for you to see them moving but also made it easier for them to see you,” he said. “On occasion, they would purposely make some noise to try and shake you up. They would produce some tinny sound or blare a bugle or just shout out. It was a psychological ploy.” A dreaded eerie sound was the “zzziiippp” made by the infamous Chinese burp gun, an incredibly fast-firing tommy gun-like weapon.

Perhaps the most terrifying action he saw came the night his outfit’s position was nearly overrun. What began as a cold damp day worsened after sunset.

“We got to our positions pretty late that night. It was raining. We dug in as fast as we could. We’d been in quite a few fire fights in the days preceding that. We thought with the weather this might be one of those nights when the enemy didn’t do anything. We were wrong,” he said. “Our machine guns started firing, and when you heard those you knew they were coming. A few of the enemy broke through our position and came right in the camp. I was quite shocked. We’d never had that before. I saw them through flashes of fire. It was very confusing. A real nightmare. We finally pushed them back.”

There were casualties on both sides. Ramsey said the enemy took advantage of the night, the rain and his unit’s complacency. “They knew Americans were not that big on night fighting and that with the bad weather we might be more inclined to worry about staying dry than steeling for attack. I think what happened is somebody in our ranks did let down. That was the only time they got in our camp that way.” He said an enemy breaching the wire could “demoralize” the troops and, if not repelled, result in a much larger breakthrough.

He described “plenty of close calls” on Able Company’s grueling march north across the 38th Parallel to engage the Chinese in the Iron Triangle stronghold. There was the omnipresent threat of mortar and artillery fire. If you stayed in the field long enough, he said, “you could hear the difference in the sound” and distinguish mortars from artillery and what size they were. Where a mortar round or artillery shell whistling high overhead gave men time to find cover, the report of the Chinese mountain gun, which fired shells in a low trajectory, allowed little or no time to hit the dirt. “You heard the report and, BOOM, it was right there. It fired in on like a straight line.” And there was occasionally the danger of friendly fire, especially errant air strikes, raining hell down on you.

Fording the streams that flowed abundantly from the mountains in Korea presented still more hazards. As heavily weighed down as the men were with their poncho, pack, boots, rifle, helmet, and ammunition, one slip in crossing the clear, fast-rushing streams (more like surging rivers) could be fatal. “A few times I felt like I was going under for sure,” Ramsey said. “I wouldn’t have had a chance.” Carrying their rifles overhead to keep them dry, the men were sitting ducks for snipers. “We were exposed,” he said.

Once, he recalls his platoon just making it to the far bank when shots began splaying the shore from the hill above. “We couldn’t see too much because it was fairly steep. We finally did draw fire on this hill.” But when Ramsey got ready to fire his M1 rifle, he got a rude surprise. “I pulled the trigger and nothing happened. That was a terrible feeling. In all that sloshing through the water my weapon must have got wet. I used a wounded buddy’s carbine instead.”

A fire fight Ramsey will never forget erupted when his 1st squad was returning to the lines after completing a mission and saw the point squad ahead of them “get hit” in an ambush of machine gun fire. Several men were cut down in the ensuing action, including 1st’s squad leader and Ramsey’s good friend — Don Hanes. “He was shot in the chest. Another fellow and I went back up this hill to get him. The fire was really intense. I was amazed we weren’t all killed on the spot. We started taking him down and Don looked at us and said, ‘No, no, no, no, no…Just leave me. You’ve got to get out of here. I’m not going to make it.’ He was a brave fellow. He was hurt so badly. Well, we did get him out of there — across an open rice paddy. He was evacuated to a hospital, but it turned out he was mortally wounded. He died later. We had a number of other casualties we carried too. It was a grim day.”

At 20, Ramsey was named temporary squad leader. He already led a four-man fire team. In addition to M1s, the team carried a single Browning Automatic Rifle or BAR. Their mission: flushing out the enemy or scouting enemy lines. Sometimes, they ran sniper patrols. If the enemy was sighted (with the aid of a sniper scope), the team’s job was to “throw some fire in” and try to pick-off or pin down targets. “We wouldn’t necessarily hit them all the time,” he said. Days or weeks might pass without enemy contact. Once, Ramsey came face-to-face with his foe. It happened when taking a hill. He and another Marine surprised a North Korean soldier. “We both fired at him, and he fell dead. We went over to where he was lying on his back. There was a pouch. We opened it and found a photo of a woman and a child. I thought, ‘He’s just like me.’ We had been thinking of the enemy as a bunch of faceless fanatics, and here was a man with a wife and child. It made an impact.”

By November 1951, Ramsey had been in-country eight months. Despite steady combat, he’d escaped unscathed. He hoped his luck held out just a few months more — then his hitch would be up and he’d be back stateside. “You see people dropping everyday. You see friends maimed and killed. You see guys going out of their head. You wonder when your number’s going to come up next. You ask yourself, ‘How can I ever get out of here?’ It’s a sinking feeling,” he said. He feels what keeps men going in such awful conditions “is your intense desire to survive and to see your loved ones again. That kept me driving.”

On the morning of November 17, his fire team “headed out on a routine sniper patrol” down Hill 834. “It was one of our more permanent lines. The hill was a muddy mess. We weren’t out long when one of us tripped a land mine, and a piece of shrapnel caught my right arm.” The impact sent Ramsey skidding face down the hill. “I was in shock, but I knew it was pretty bad because my dungaree jacket was shredded and blood was all over the place.” Metal fragments had severed his ulnar nerve and fractured bones. His mates brought a Navy corpsman to his side. The corpsman applied a bandage and administered a shot of morphine. Ramsey’s buddies then carried him up the hill and down the reverse slope to a small, level clearing. There, a second casualty from down the line was stretchered in — missing a foot. Ramsey recalls an officer giving him a cigarette to drag on and saying, “You got a million dollar wound there, Bill…you’ll probably be going home.” Still, Ramsey worried he might lose his shattered arm, which burned with pain. A helicopter evacuated he and the other casualty to a nearby MASH unit.

Rushed into surgery, Ramsey awoke the next day to the news doctors had saved the arm. Wearing a cast, he was taken (by ambulance) to an Army hospital in the devastated capital of Seoul. “There was nothing standing,” he said. From there, he was flown (on a transport plane stacked with wounded) to an Army hospital in Osaka, Japan, spending days in agony (receiving no treatment as a non-Army patient) before transferred (via train) to a Navy hospital in Yukosuka, where he finally found some relief for the pain and slept for the first time in nine days.

In early December he hopped a four-engine prop bound for the states. He landed at Travis Air Force Base in southern California. His first impulse was to call home. He next reported to Oak Knoll Navy Hospital near Oakland, where he underwent skin grafts and three months of physical therapy. During his rehab, the Purple Heart recipient recalls being torn by two emotions: “I felt sick about leaving and letting my buddies down. But the other side of it was I was really thankful to get out. Eight months there was enough.” His long voyage back ended almost a year to the day his Korean odyssey began. A relieved Ramsey arrived to “the quiet of my wonderful home.” He downed a beer and thanked God the journey was over at last.

Upon his return (he graduated from Creighton University) he was dismayed by the indifference civilians expressed toward the raging conflict. From its start in June 1950 to its conclusion three years later, it never captured the public’s imagination. Many observers feel it came too quickly on the heels of World War II for Americans — then preoccupied with living the good life — to care. Cloaked under the murky misnomer “police action,” it became a shadow war.

President Harry S. Truman summed up the national mood when he called it “that dirty little war.” Its status as “the forgotten war” was sealed when it ended not with victory but an armistice leaving Korea still divided at the 38th Parallel (with a permanent American military presence there to keep the peace.) Lost on many was the fact the true objective — preserving a democratic South Korea — was accomplished. In the larger scheme of things, a free South Korea has emerged as a thriving economic juggernaut while a closed North Korea has withered in poverty. Ramsey saw for himself the economic miracle wrought in South Korea on a 1979 trip there. He met a people grateful for his and his comrades’ sacrifices. Monuments abound in recognition of the U.N. “freedom fighters.”

It is only recently, however, these veterans got their due in America. In 1995 the Korean War Memorial was dedicated in Washington, D.C. (Ramsey was there). In the late ‘70s Ramsey, whose post-war life has been devoted to causes, spearheaded the erection of a joint Korean-Vietnam War monument in Omaha’s Memorial Park. The monument has received a recent refurbishing and the addition of a flower garden. This year, he started a Nebraska chapter of the National Korean War Veterans Association.

For vets who went to hell and back, the war is never far from their thoughts. “I’m proud to have served. We stood fast. We saved the south. I can think of no higher compliment than to be called a freedom fighter,” said Ramsey, who, in 1997, faced a new enemy — prostate cancer. Aggressive treatments have left him cancer free. In August, he attended a reunion of his 1st Marine Division mates. “My admiration continues to grow for the Marines with whom I served,” he said. For their heroic actions there, the division received the rarely bestowed Presidential Unit Citation.

Related Articles

- Editorial: Korean War veterans are due recognition (knoxnews.com)

- Legacy of the Korean War (theworld.org)

- Stunning photo gallery remembers the Korean War (holykaw.alltop.com)

- Veteran laments long wait for Korean War day (cbc.ca)

Chuck Powell: A Berlin Airlift Story

One of the nice things about a blog like mine is that I can revive or resurrect stories long ago published and forgotten. Here’s a story I did about a man who had a remarkable military service record. His name was Chuck Powell. He passed away recently, and I post his story here as a kind of tribute or memorial. I did the story around an anniversary of the Berlin Airlift, which he participated in as a pilot. He also flew in World War II and in the Korean War. He nearly flew in Vietnam. Powell was a great big old Texican who had a way with words. He was an example to me of never judging a book by its cover. By that I mean he appeared to be one thing from the outside looking in but he was that and so much more. For example, by the time I met him he was pushing 80 and a tenured academic at my alma mater, the University of Nebraska at Omaha, but none of that suggested the many adventures he had experienced far removed from academia, adventures in and out of wartime, that added up to a wild and woolly life.

The profile originally appeared in the New Horizons and I think, like me, you’ll find Powell’s story compelling if for no other reason than all the history his life intersected with.

Chuck Powell: A Berlin Airlift Story

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Somehow it’s fitting one-time aviator turned political scientist, gerontology professor, history buff and pundit Chuck Powell holds court from a third-floor office perch on the University of Nebraska at Omaha campus. There, far removed from the din of the crowd, he analyzes trends affecting older Americans, which, at 78, he knows a thing or two about.

On any given week his office, tucked high away in a corner of an old brick mansion, is visited by elected officials from across the political spectrum seeking advice on public policy and legislative matters.

“Most of the so-called issues are perennial. They don’t change. Most of the time people are searching for some magic silver bullet, but there isn’t any. My advice is usually pretty simple,” he says.

Don’t mistake Powell for some ivory tower dweller though. Whether offering sage counsel or merely shooting the bull in his down-home Texas drawl, this high flier and straight shooter draws as much on rich life experience as broad academic study with students and politicos alike.

And, oh, what a life he’s led thus far. During a 30-year military career he saw duty as a Navy combat pilot in the Pacific during World War II, a photo reconnaissance pilot in China and a C-54 jockey in the Berlin Airlift. Later, he flew combat cargo missions in Korea. By the time he retired a Naval officer in 1971 he’d seen action in two wars, plus the largest air transport operation in history, been stationed in nearly every corner of the globe and risen through the ranks from seaman to pilot to commander.

He’s gone on to earn three college degrees, teach in post-secondary education and travel widely for pleasure. Yet, for all his adventures and opinions, he’s rather taciturn talking about himself. Chalk it up to his self-effacing generation and stern east Texas roots. Nothing in his home or office betrays his military career. His wife, Betty Foster, said even friends were surprised to learn he’s a veteran of the 1948-49 airlift, a fact made public last spring when he and fellow veterans were honored in Berlin at a 50th anniversary event. Participating in “Operation Vittles” changed his life.

“There’s a strong feeling of public service among those of us who served in the airlift because it left us with the idea we could do great things without bombing the bejesus out of somebody,” he says.

While he has, until now, been reluctant to discuss his military service, his impressions, especially of the airlift, reveal much about the man and his take on the world and help explain why his advice is so eagerly sought out.

Born along the Texas-Louisiana border, he was reared in Tyler and a series of other small east Texas towns during the Depression. He hardly knew his father and was often separated from his mother. Shuttled back and forth among relatives in a kind of “kid of the month club,” as he jokingly refers to it, he spent much time living with an uncle and aunt — Claiborne Kelsey Powell III, an attorney and Texas political wheel, and his wife Ilsa, a University of Chicago–educated sociologist and Juilliard-trained musician.

One of Powell’s clearest childhood memories is Claiborne taking him to see the inimitable populist Huey Long stumping for a gubernatorial bid in nearby Vernon Parish, La. He recalls it “just like it was yesterday. The guy was so impressive. He was a big man. He had a large head and a full head of hair and wore a white linen suit with a string tie. He’d go, ‘My friends, and I say, you are my friends…’ Yeah, Huey man, he was a hoot.”

Surrounded by Claiborne’s political cronies and exposed to his and Ilsa’s keen wit and elevated tastes in music and books Powell was, without knowing it then, groomed to be a political animal and scholar. He credits his uncle with being “probably the most influential person in my life” and sparking an insatiable inquisitiveness. “I’m a curious person. I’m someone who likes to turn over every rock in sight,” Powell concedes. Betty, a gerontological educator and consultant, adds, “He doesn’t look at the surface of most things. He looks far deeper than most people do. Chuck is always looking at why we do things. He’s very, very bright.”

Searching for some direction early in life, Powell found it in the Navy at the outbreak of World War II. Besides serving his country, the military gave him a proving ground and a passport to new horizons.

“It provided a way out. I could hardly wait to get on the road.”

The sea first took him away. In a series of twists and turns he doesn’t elaborate on, his early wartime Naval service began as a sailor in the Atlantic and ended, improbably, as a fighter pilot in the Pacific. The only thing he shares about his combat flying experience then is: “I heard some gunshots, let’s put it that way, but by the time the war ended the overpowering might of the United States in the Pacific was such that you rarely got an opportunity to even see, let alone shoot at, the enemy.”

After a year’s duty in China he returned home and was assigned to the Military Air Transport Service (MATS). “I was in a Navy four-engine transport squadron that flew out of Washington National. We had nightly, non-stop routes that went from Washington to San Francisco.”

Then, in June 1948, the Soviets blockaded all ground and water routes in and out of West Berlin and Powell and his mates were redeployed to Germany to support the, at first, ragtag airlift of vital supplies into the isolated and beleaguered city. The first supplies were flown in June 25.

Powell’s first missions supported the airlift itself: “We started flying equipment and personnel to Rhein-Main,” a major air base and staging area near Frankfurt. Attached to Air Transport Squadron 8, he found himself thrown in with other airmen originally trained for combat duty. Its skipper, “Jumpin” Joe Clifton of Paducah, Ky., was a decorated fighter pilot.

The start of “Operation Vittles” was inauspicious. Men and material were scarce. The few supplies lifted-in fell woefully short of needs. The whole thing ran on a wing and a prayer. Allied commanders and German officials knew Berliners required a daily minimum 3,720 tons, including coal and food, to ensure their survival, yet Powell says,“there was no evidence they could lift this much tonnage daily. The first day they cobbled together a group of old C-47s and lifted 80 tons. That was 3,620 tons short.

The task, as it began, was very high on optimism and low on reality because Berlin’s huge, about 400 square miles, and we’re talking about supplying a city the size of Philadelphia by air.” All sorts of alternate supply schemes — from armored transport convoys to mass parachute drops — were rejected.

Hindering the early operation was a lack of infrastructure supporting so mammoth an effort.

To meet the supply goals hundreds of C-47s and C-54s had to be brought in from around the world and pipelines laid down from Bremerhaven to Frankfurt to carry fuel. All this — plus devising a schedule that could safely and efficiently load and unload planes, maintain them, get them in the air and keep them flying around-the-clock, in all weather — took months ironing out. Yet, even during this learning curve, the airlift went on, growing larger, more proficient each week. Still, it fell far short of targets as winter closed in, leaving the terrible but quite real prospect of women and children starving or freezing to death.

“The first six months of the airlift were nothing to write home about,” Powell recalls. “The stocks in Berlin were drawn down. All the trees were cut to be used for fuel. We watched that tonnage movement day by day and, intuitively, everybody on the line knew how bad things were headed.”

Historians agree the turning point was the appointment of Maj. Gen. William H. Tunner as commander of the combined American-British airlift task force. He arrived with a proven air transport record, having supplied forces over “The Hump” in India and China during the war. He and his staff brought much needed organization, streamlining things from top to bottom.

The number of flights completed and quantity of tons delivered increased, but when Tunner, “a bird dog” who observed operations first-hand, was on a transport during a gridlock that stacked planes up for hours, he insisted staff devise improved air traffic routes and rules that kept planes in a rhythmic flow The result, a loop dubbed “the bicycle chain,” smoothly fed planes through air corridors in strict three-minute intervals.

“Gen. Tunner was a tremendous leader. He knew you couldn’t turn a bunch of cowboys loose with these airplanes and expect precision. Under him, the airlift became a rigidly controlled operation. You had to fly just precisely, otherwise you were gonna be on the guy ahead of you or the guy behind you,” Powell says.

With so little spacing between planes, there was scarce margin for error, especially at night or in the foul weather that often hampered flying.

“With a guy coming in three minutes behind you, if you missed your first approach you didn’t have enough time to take another shot. You either made it the first time or you went home,” says Powell, who after a few weeks ferrying essentials to support the airlift’s launch, began carrying coal into Berlin’s Tempelhof airport from Rhein-Main (the base in the southern corridor reserved for C-54s). “If everything was going right you could do a turnaround (roundtrip) in four hours. If it wasn’t going right it could take you 24 hours. There were any number of things that could go wrong.”

Rules were one thing, says Powell, but they were often ignored in the face of the dire task at hand. “I can’t speak for anybody but myself but I never carried a load of coal back. There were times in the airplane when you set the glide path and the descent and the first you knew you’d landed is when you hit something.” To work, he explains, the airlift depended on men and machines going beyond the norm in “a max effort.”

“We were flying over manufacturers’ specified weights. Engines were a constant problem. We were wearing these things out. The airplane was actually being asked to do things it wasn’t even built to do, and everybody knew that. In wars and crises things are set aside. You take chances because you don’t have time to sit around and procrastinate. The Soviets were trying to starve the people of Berlin into submission. You got swept up in all this and pretty soon you were doing all you could. The only time I know of when it (the airlift) was shut down was one night when there were some violent thunderstorms. I was in the corridor and man, it was grim that night up there. Just before we were ready to take off at Tempelhof to come back home they shut the thing down for six or seven hours until that storm dissipated.”

Considering the scale of operations, blessedly few planes and lives were lost. During the entire 15-month duration, covering some 277,000 sorties, 24 Allied planes were lost and 48 Allied fliers killed. Another 31 people died on the ground. “I think it’s remarkable that with all the things that were required, we lost so few,” Powell says.

All the more remarkable because aside from the dangers presented by night flying, storms, fog, overtaxed planes and fatigued fliers, there were other risks as well. Take the Tempelhof approach for example.

“Tempelhof was the toughest of all the fields,” he notes, “because you were coming in over a nine-story bombed-out apartment building. You had a tremendous angle on your glide slope.”

Then there was the danger of transporting coal. A plane might blow if enough static electricity built-up and ignited the dust that settled over every nook and cranny. To ventilate planes crews flew with emergency exits off.

“It was noisy,” Powell says, “but you couldn’t argue with it because then you’d be arguing you want to get killed.”

Coal dust posed an added problem by fouling planes’ hydraulics and irritating fliers’ eyes. Powell was legally blind six months and grounded for two due to excess coal dust in his eyes. He says even the most benign loads, if not properly lashed down, could shift in mid-air and compromise flight stability.

“You didn’t want anything rockin’ around loose in the airplane.”

He reserves his highest praise for the Army Quartermaster and flight maintenance crews that kept things running like clockwork. German citizens made up part of the brigade of workers loading and unloading supplies and servicing planes.

“The crews were exceptional. They were absolutely incredible in their ability to perform this work and to perform quickly.”

The operation got so precise that a C-54 could be loaded with 22,000 to 25,000 pounds of supplies, refueled and lift-off — all within 20 minutes.

“It wasn’t going to run unless everybody did their job, and if one part broke down the whole thing broke down.”

He says many civil aviation advances taken for granted now were pioneered then, such as strobe lights lining runways and glowing wands used by grounds crew to steer planes to gates. All this happened in a pressure-cooker environment and the menacing presence of nearby Soviet forces. The Soviets used harassment tactics, including sending fighters to buzz transport planes and ordering ground-based anti-aircraft batteries to fire rounds at the corridors’ edges.

Powell says if the tactics were meant as intimidation, they failed.

“C’mon, we’d all been shot at before, give me a break. The ammunition made for a good fireworks display, but it made no impact. Probably the worst thing they did from my point of view was shine some very high-powered searchlights on the aircraft at night and jam the final control or frequency. You just had to keep driving and hope you made it all right.”

Make no mistake, it was a tense time. The blockade and airlift had put the world on the brink. One false move by either side could have triggered WWIII. Despite the threat, U.S. and British resolve held firm and the Cold War didn’t turn hot. By 1949 it was clear the airlift was succeeding beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. Tunner’s bicycle chain was humming along and with the weather improving that spring he chose Easter Sunday to kick the operation into overdrive. In what became known as The Easter Parade, the airlift’s spacing was dropped to one-minute intervals and in a single 24-hour stretch in April a record 1,390 flights delivered 12,940 tons into Berlin.

“A one-minute separation — that’s pretty close for big overloaded airplanes,” Powell says. “I don’t think we could have cut it any closer. But it was a beautiful day. The weather was ideal. You could see everybody. That made it easier. The Soviets of course were betting the next day would be a huge fall-off but we did something like 8,000 tons. By then we’d hit our stride and we were routinely lifting 8,000 to -9,000 tons a day. It sent a message to Joe Stalin. The next month the Soviets lifted the blockade.”

However, the airlift continued months afterward as a buffer against any further Soviet ploy. By operation’s end — September 30, 1949 — more than 2.3 million tons of supplies had been lifted-in and a world crisis averted.

For Powell, its success, along with rebuilding Europe, were America at its best. “We’re an amazing country. Sometimes we have a veritable uncanny propensity to do the right thing. It brought into rather sharp relief just what could be done. In my humble opinion the United States, between 1945 and 1950, could be compared to ancient Greece under Pericles. It as a golden era. We did virtually everything right and you can’t do that without leadership. We were deep in leadership after the war.”

He says the feeling in America then — “that everybody was in this together” — is hard for young people to understand. “Now, we’re so disparate. Everybody’s off doing their own thing. But I still put my faith in the willingness of the American people to do the right thing…given the right leadership.” The airlift’s legacy, he says, is the goodwill it generated. “Civic-minded Germans formed the Berlin Airlift Foundation to take care of the wives and children of the airmen killed in the lift.

When he joined other vets in Berlin last May he spoke with Germans who vividly recalled the airlift. “They all mentioned the omnipresent noise. One lady told us, ‘It didn’t bother us because we knew if the noise continued we would eat.’ He adds the warm outpouring of gratitude got him “a little choked up. We made generations of friends there.” He says if there’s any heroes in all this, it’s “the people of Berlin, because they could have very easily gone to the Soviet sector and been fed and clothed. No question. They were down to 1,200 calories a day but chose to stay and stick it out. These people sought self-determination.”

After the airlift Powell was set to study law when the Korean War erupted. He spent 21 more years in the service, moving from place to place “like a locust.” Posted in France during the ‘60s, he became a certified Francophile — enamored with the nation’s history, culture, people. He’s often returned there.

Along the way he married, raised a family (he has three grown children) and indulged a lifelong search for knowledge by reading and studying. He describes himself then as “a kind of journeyman” scholar. That all changed in 1964 when plans to join an F4 Phantom squadron off the coast of Vietnam were scuttled and he was assigned instead to Offutt Air Force Base.

Here, he finally stayed one place long enough to earn a degree (in business administration from Bellevue University). And here he’s remained. His post-military career saw him remake himself as an authority on public policy and aging issues, earning a master’s in public administration and a Ph.D. in political science. UNO hired him in 1973 to implement training programs under the Older Americans Act.

As a full professor today he teaches courses, advises students and collaborates with colleagues on

articles, surveys and studies. He’s applied the public service mission he took from the airlift to serve political campaigns, advise local and state government and participate in White House conferences on aging. Both his life and work dispel many myths about aging.

“We feel it’s wonderfully appropriate to have a 78-year-old teaching younger people all older people are not alike,” says James Thorson, UNO Department of Gerontology Chairman. “Dr. Powell is an excellent instructor and accomplished researcher. He’s wildly popular with students. He works long hours. He wants to wear out, not rust out, and I respect him for it.”

It was at UNO Powell met Betty. Both were recently divorced. He was teaching, she was doing grad work. They married in 1982. Everyone agrees they make a good match. They travel together and enjoy entertaining at their sprawling Keystone neighborhood home, where he often holes up in a study whose impressive library is stocked with volumes on American history (the presidents, the Civil War) and France. Travel is no idle pursuit for him. He researches destinations and prepares itineraries detailing sites and themes, from architecture to art to vineyards. He got in the habit in the service.

“It permits you to observe how other people do things and to see Americans don’t have a corner on how things are done.”

The couple prove growing older doesn’t necessarily mean slowing down. In typical fashion he and Betty plan ushering in the new millennium under the Eiffel Tower in Paris. “I’m really looking forward to it,” he says. In his office hangs an enlarged photo of the French landmark with an inscription that sums up his ageless sense of wanderlust: “Paris is like a lover. You may leave her, but you will never forget her.” It’s the same way with Chuck Powell: Once you meet him, you never forget him.

Related Articles

- Causes, Reasons and Results of the Berlin Airlift (brighthub.com)

- Trail of the unexpected: Tempelhof Park, Berlin (independent.co.uk)

- James Rodney Ferrell, 90 (kitsapsun.com)

- History: The Berlin Airlift (americanthings.wordpress.com)

- How much supplies did Berlin Airlift receive (wiki.answers.com)

- Candy Bomber: The Story of the Berlin Airlift’s Candy Bomber: The Story of the Berlin Airlift’s “Chocolate Pilot” by Michael O. Tunnell (alleganylibrarycollections.wordpress.com)

Thomas Gouttierre: In Search of a Lost Dream, An American’s Afghan Odyssey

Thomas Gouttierre’s work with Afghanistan has drawn praise and criticism, moreso the latter as of late given what’s happened there with the war and some of that nation’s top leadership having been befriended and trained by Gouttierre’s Center for Afghanistan Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The following profile I did on Gouttierre appeared in 1998, long before U.S. involvement there escalated into full military intervention. Regardless of what’s happened since I wrote the piece, the essential core of the story, which is that of Gouttierre’s magnificent obsession with that country and its people, remains the same.

The story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Thomas Gouttierre: In Search of a Lost Dream, An American’s Afghan Odyssey

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Like a latter-day Lawrence of Arabia, Omahan Thomas Gouttierre fell under the spell of an enigmatic desert nation as a young man and has been captivated by its Kiplingesque charms ever since.

The enchanting nation is Afghanistan and his rapture with it began while working and living there from 1965 to 1974, first as a Peace Corps volunteer teaching English as a second language, then as a Fulbright fellow and later as executive director of the country’s Fulbright Foundation. His duties included preparing and placing Afghan scholars for graduate studies abroad. During his 10 years there, Gouttierre also coached the Afghan national basketball team. Sharing the adventure with him was his wife and fellow Peace Corps volunteer Marylu. The eldest of the couple’s three sons, Adam, was born there in 1971.

Before his desert sojourn, the Ohio native was a naive, idealistic college graduate with a burning desire to serve his fellow man. When he got his chance half-a-world away, it proved a life transforming experience.

“It’s the place where I kind of grew to a mature person,” he said. “I was there from age 24 to 34 and I learned so much about myself and the rest of the world. It gave me an opportunity to learn well another language, culture and people. I love Afghanistan. It’s people are so admirable. So unique. They have a great sense of humor. They’re very hospitable. They have a great self-assurance and pride.”

But the Afghanistan of his youth is barely recognizable now following 19 years of near uninterrupted carnage resulting from a protracted war with the former Soviet Union and an ongoing civil war. Today, the Muslim state lies in shambles, its institutions in disarray. The bitter irony of it all is that the Afghans themselves have turned the heroic triumph of their victory over the vaunted Soviet military machine into a fratricidal tragedy.

Over the years millions of refugees have fled the country into neighboring Pakistan and Iran or been displaced from their homes and interred in camps across Afghanistan. An entire generation has come to maturity never setting foot in their homeland or never having known peace.

The nation’s downward spiral has left Gouttierre, 57, mourning the loss of the Afghanistan he knew and loved. “In a sense I’ve seen what one might call the end of innocence in Afghanistan,” he said, “because for all its deficiencies, Afghan society – when I was living there – was really a very pleasant place to be. It was a quite stable, secure society. A place where people, despite few resources and trying circumstances, still treated each other with a sense of decency and civility. It was a fantastic country. I loved functioning in that Afghanistan. I really miss that environment. Not to be able to go back to that culture is a real loss.”

Through it all, Gouttierre’s kept intact his ties to the beleaguered Asian nation. In his heart, he’s never really left. The job that took him away in 1974 and that he still holds today – as director of the Center for Afghanistan Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha – has kept him in close contact with the country and sent him on fact-finding trips there. He was there only last May, completing a tour of duty as a senior political affairs officer with the United Nations Special Mission to Afghanistan. It was his first trip back since 1993 (before the civil strife began), and what he saw shook him.

“To see the destruction and to learn of the deaths and disappearances of so many friends and associates was very, very sad,” he said from his office on the UNO campus, where he’s also dean of the Office of International Studies and Programs. “Much of the country looks like Berlin and Dresden did after the Second World War, with bombed-out villages and cities. Devastation to the point where almost no family is left unaffected.

“Going back for me was very bittersweet. With every Afghan I met there was such despair about the future of the country. The people are fed up with the war…they so want to return to the way things were. People cried. It was very emotional for me too.”

Everywhere he went he met old friends, who invariably greeted him as “Mr. Tom,” the endearing name he’d earned years before. “In every place I visited I wound up seeing people that I have known for most of my adult life. Individuals that have been here at the University of Nebraska at Omaha – in programs that we’ve sponsored – or people I coached in basketball or people I was instrumental in sending to the U.S. under Fulbright programs or people who taught me Persian and other languages of Afghanistan. So, you know, there’s kind of an extended network there. In fact, it was kind of overwhelming at times.”

Colleague Raheem Yaseer, coordinator of international exchange programs in UNO’s Office of International Studies and Programs, said, “I think he’s received better than any ambassador or any foreign delegation official. He’s in good standing wherever he goes in Afghanistan.”

Yaseer, who supervised Gouttierre in Afghanistan, came to America in 1988 at the urging of Gouttierre, for whom he now works. A political exile, Yaseer is part of a small cohesive Afghan community in Nebraska whose hub is UNO’s Center for Afghanistan Studies. The center, which houses the largest collection of materials on Afghanistan in the Western Hemisphere, provides a link to the Afghans’ shared homeland.

Aside from his fluency in native dialects, his knowledge of Islamic traditions and sensitivity to Afghan culture, Gouttierre also knows many of the principals involved in the current war. It’s the kind of background that gives him instant access and credibility.

“I don’t think there’s any question about that,” Gouttierre said. “The Afghans have a phrase that translates, ‘The first time you meet, you’re friends. The second time you meet, you’re brothers.’ And Afghans really live by that – unless you poison that relationship.”

According to Yaseer, Gouttierre’s “developed a skill for penetrating deep into the culture and traditions of the people and places he visits. He’s able to put everything in a cultural context, which is rare.”

It’s what enables Gouttierre to see the subtle shadings of Afghanistan under its fabled veil of bravado. “When people around the world wonder why the Afghans are still fighting, they don’t realize that a society’s social infrastructure and fabric is very fragile,” said Gouttierre. “They don’t realize what it means to go through a war as devastating as that which the Afghans experienced with the Soviet Union – when well over a million people were killed and much of the traditional resources and strengths of the country were destroyed. When the Soviets left, the Afghans tried to cobble together any kind of government and they were unsuccessful.

“Now they’re trying to put this social-political Humpty-Dumpty back together again, and its just very difficult.”

Under Gouttierre’s leadership the center has been a linchpin in U.S.-U.N. efforts to stabilize and rebuild Afghanistan and has served as a vital conduit between Afghans living inside and outside the country and agencies working on the myriad problems facing it. With nearby Peshawar, Pakistan as a base, the center has operated training and education programs in the embattled country, including a new program training adults in skills needed to work on planned oil and gas pipelines.

Gouttierre himself is a key adviser to the U.S. and world diplomatic community on Afghan matters. He’s served as the American specialist on Afghanistan, Tajikistan and South Asia at meetings of the U.S.-Russian Task Force (Dartmouth Conference) on Regional Conflicts. He’s made presentations on Afghan issues at Congressional hearings and before committees of the British Parliament and the French National Assembly.

And last year he was nominated by the U.S. State Department to serve as the American representative on the U.N. Mission to Afghanistan. “It was quite an honor,” said Gouttierre. “And for me to go back and work among the people again was very appealing and very rewarding.”

The aim of the U.N. mission, whose work continues today, is to engage the combating parties in negotiations toward a just peace settlement. German Norbert Holl, a special representative of the U.N. secretary general to Afghanistan, heads the mission, whose other members are from Russia, Japan, England and France.

On two separate month-long trips to Afghanistan, Gouttierre met with representatives of the various factions and visited strategic sites – all in an effort to help the team assess the political situation. His extensive travels took him the length and breadth of the country and into Pakistan, headquarters for the mission. He talked with people in their homes and offices, he visited bazaars, he viewed dams, irrigation projects and opium fields and traversed deserts and mountains.

Marylu Gouttierre said her husband’s involvement with Afghanistan and commitment to its future stems, in part, from a genuine sense of debt he feels. “He feels a responsibility. It is his second home and those are his people. He’s not only given his heart, but his soul to the country.”

He explains it this way: “Afghanistan has a special place in my professional and personal life and it has had a tremendous impact on my career. It’s been so much an instrument in what I’ve done.”

To fully appreciate his Afghan odyssey, one must review how the once proud, peaceful land he first came to has turned into a despairing, chaotic killing field. The horror began in 1978, when Soviet military forces occupied it to quell uprisings against the puppet socialist regime the USSR had installed in the capital city of Kabul. The Soviets, however, met with stiff resistance from rebel Mujaahideen freedom fighters aligned with various native warlords. Against all odds, the Afghans waged a successful jihad or holy war that eventually ousted the Soviets in 1989, reclaimed their independence and reinforced their image as fierce warriors.

The Afghans, whose history is replete with legendary struggles against invaders, never considered surrender. Said Gouttierre, “The Afghans felt they were going to win from the start. They felt they could stick with it forever. They had a strong belief in their own myth of invincibility…and to everyone’s surprise but their own, they did force the Soviets to leave.”

But the fragile alliance that had held among rival factions during the conflict fell apart amid the instability of the post-war period. “The Soviets left someone in charge who had been their ally in power. That was Najeebullah. His government fell in 1992. That only helped exacerbate things. The cycle of fighting continued as the Afghans who had fought against the Soviet army continued their fight against Najeebullah, who was captured, tried and executed by the Taliban (an Islamic faction) in September of 1996 for his crimes against the Afghans, which were considerable.” Gouttierre knew Najeebullah in very different circumstances before the war, when the future despot was a student of his in a class he taught at a native high school.

After Najeebullah’s fall, a mad scramble for power ensued among the Mujaahideen groups. As Gouttierre explains, “The leaders of these groups had become warlords in their own regions. They kind of got delusions of grandeur about who should be in control of the whole country and they began to struggle against each other.”

In the subsequent fighting, one dominant group emerged – the Taliban, a strict Islamic movement whose forces now command three-quarters of the country, including the capital of Kabul – with all its symbolic and strategic importance. A loose alliance of factions oppose the Taliban.

“As the Taliban (Seekers of Islam) grew in strength, they began intimidating and even fighting some of the minor Mujaahideen commando groups, and to a lot of people’s surprise, they were successful,” said

Gouttierre, whose U.N. assignment included profiling the Taliban. “They are very provincial, very rural – and in their own minds – very traditional Muslims and Afghans. They’re not that philosophically sophisticated in terms of their own religion, but they are very sophisticated in terms of what they understand they want for their society, and they’re able to argue and discourse on it at length without giving any quarter. And they’re willing to go to war over it.

“Each region where they’ve gone, they’ve been aided by the fact that the people living there were disenchanted with those in control. Most of the other groups, unfortunately, lost any credibility they had because of their failure to bring about peace, stability, security and reconstruction. The people were willing to support almost anything that came along.”

The Taliban has drawn wide criticism, internally and externally, for its application of extreme Islamic practices in occupied areas, particularly for placing severe restrictions on women’s education and employment and for imposing harsh penalties on criminals. Gouttierre said while such actions elicit grave concerns from the U.N. and represent major stumbling blocks in the Taliban’s quest for full recognition, the movement has effectively restored order in areas it controls.

“I have to say that in the areas of Afghanistan I traveled to which they control, the Taliban had confiscated all the weapons, removed all the checkpoints people had to pass through, eliminated the extortion that was part of the checkpoints and instilled security and stability,” said Gouttierre. “You could travel anywhere in Kabul without having to be in any way concerned, except for the mines that haven’t been cleared yet.”

Conversely, he said, the Taliban has exhibited brutal politics of intimidation and blatant human rights violations, although other factions have as well. “It’s not a question of who’s good and who’s bad,” he adds. “There’s plenty of blame and credit to be shared on all sides.”

He found the Taliban a compelling bunch. “One of the things I was impressed with is that all of the leaders I met were in some ways victims of the war with the Soviet Union. They all exhibited wounds, and they acquired these wounds heroically carrying out the struggle against the Soviet Union, and I respect them for that. That needs to be taken into account.”

In addition to pushing for a ceasefire between the Taliban and its adversaries, Gouttierre said the U.N. mission consistently makes clear that in order to gain credentialing from the U.N. and support from key institutions like the World Bank, the Taliban must do a better job of protecting basic human rights and ensuring gender equity.

He said the main barrier to reaching a cease fire accord is the Taliban’s nearly unassailable military position, which gives them little reason to make concessions or accept conditions. Another impediment to the peace process is the nation’s rich opium industry, whose interests diverge from those of the U.N. And a major complicating factor is the support being provided the warring factions by competing nations. For example, Pakistan and certain Persian Gulf states are major suppliers of the Taliban, while Iran and Russia are major suppliers of the opposition alliance.

Taliban and opposition leaders did meet together at several U.N. sponsored negotiation sessions. The representatives arrived for the talks accompanied by armed bodyguards, who remained outside during the discussions. The tenor of the meetings surprised Gouttierre. “It was far more cordial than I had anticipated. These men got along remarkably well, in part because they all know each other. That’s not to say there weren’t disagreements. When offended, Afghans can be exceedingly formidable to deal with.”

At Gouttierre’s urging, the mission began holding intimate gatherings at which representatives of the warring parties met informally with U.N. officials over food and drinks and “where translators were not the main medium for communication and where everybody wasn’t on guard all the time.” He hosted several such luncheons and dinners, including ones in Kandahar, Baamiyaan and Kabul. The idea was to create a comfortable mood that encouraged talk and built trust. It worked.

“In diplomatic enterprises often the most effective periods are at the breaks or the receptions, because you’re sometimes able to get people off to the side, where they’re able to say off the record what they can’t say officially. And that’s exactly what happened. Those of us in the U.N. mission got a better sense of who the Taliban are. They’re not irrational. They do have a sense of humor. And they got a better sense of who we are – that we’re not just officials, but that we also have a long-term interest in Afghanistan.”

Gouttierre said the mission has overcome “high skepticism” on the part of Afghans, who recall the U.N. granted Najeebulah asylum despite his being a war criminal. He said the Afghans’ estimation of the mission has moved from distrust to acceptance. And he feels one reason for that is that the present mission has “more clout and recognition than any previous mission to Afghanistan.” Supplying that essential leverage, he said, is the “unstinting support of influential countries like the U.S., France, England, Russia and Japan.”

Despite recent news stories of military inroads made by opposition forces, especially around Kabul, the Taliban remain firmly entrenched. Gouttierre believes that unless a major reversal occurs to change the balance of power, the Taliban will continue calling the shots. If the Taliban eventually consolidate their power and conquer the whole nation, as most observers believe is inevitable, the hope then is that the movement’s leaders will feel more secure in acceding to U.N. pressure.

Gouttierre said that despite the failure to gain a ceasefire thus far, “the fact remains the two sides are meeting with each other, and that’s the first step in any peace process. We don’t have agreements on anything yet, but at least the channels for continuing dialogue have been opened.”