Archive

The Two Wars of Ben Kuroki: New book out about Nebraskan who defied prejudice to become a war hero

I am reposting this article because the person profiled in it is the subject of a new young reader’s book, Lucky Ears: The True Story of Ben Kuroki, World War II Hero. Author Jean Lukesh’s biography tells the inspirational story of how Kuroki, a Nebraska-born, Japanese-American, fought two wars — one against prejudice and one against the Axis Powers. I told the same story in a series of articles I wrote about Kuroki a few years ago, when he was receiving various honors for his wartime and lifetime contributions to his country and when a documentary about him was premiering on PBS.

Ben Kuroki, who grew up in Hershey, Neb., was one of 10 children and did not experience discrimination until he and his brother tried to join the Army right after the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor. Ben was Nisei – an American born of Japanese parents. Kuroki had to fight like hell for the right to fight for his own country.

Finally allowed to become a gunner on a B-24 and flew his first mission in December of 1942. Life expectancy for a bomb crew member was ten missions. Kuroki flew 58 missions — and became the only American during WWII to fly for four separate Air Forces — and the only Japanese American to fly over Japan in combat in WWII.

As Kuroki friend Scott Stewart reported to me and other friends, on Nov. 10 in Washington D.C. Kuroki received the prestigious Audie Murphy Award — named after the most decorated American veteran in WWII. The American Veterans Center’s will present the award to Ben Kuroki at their annual conference gala.

Kuroki received little official recognition for his war efforts during his time in the service, but since 2005 the flood gates opened and the honors started flowing.

*Distinguished Service Medal — the Army’s third highest award in 2005 at a ceremony in Lincoln followed by the Nebraska Press Association’s highest honor, the President’s Award and the University of Nebraska honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters.

*Black Tie State Dinner at the White House with Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in 2006

*2007, Lincoln hosted the world premier showing of the PBS documentary on the Kuroki war story Most Honorable Son.

*Presidential Citation from President George W. Bush in May 2008

*Smithsonian dedicated a permanent display on Ben war record, May 2008

At his acceptance speech on Saturday Kuroki will say “words are inadequate to thank my friends who went to bat for me and bestowed incredible honors decades later. Without their support, my war record would not have amounted to a hill of beans. Their dedication is the real story of Americanism and democracy at its very best. I now feel fully vindicated in my fight against surreal odds and ugly discrimination.

As I mentioned above, this article is one of several I wrote about Kuroki around the time the documentary about him, Most Honorable Son, was premiering on PBS. I am glad to share the article with first time or repeat visitors to this site.

The Two Wars of Ben Kuroki:

New book out about Nebraskan who defied prejudice to become a war hero

Honors keep rolling in for much decorated veteran

After Pearl Harbor, Ben Kuroki wanted to fight for his country. But as a Japanese-American, he first had to fight against the prejudice and fear of his fellow Americans. The young sergeant from Hershey, Neb., proved equal to the task.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Nebraska Life Magazine.

“I had to fight like hell just for the right to fight for my own country,” said Hershey, Neb., native Ben Kuroki. During World War II, he became one of only a handful of Japanese-Americans to see air combat, and was America’s only Nisei (child of Japanese immigrant parents) to see duty over mainland Japan.

For Kuroki, just being in the U.S. Army Air Corps was an anomaly. At the outset of war, Japanese-American servicemen were kicked out. Young men wanting to enlist encountered roadblocks. Those who enlisted later were mustered out or denied combat assignments. But Kuroki was desperate to prove his loyalty to America, and persisted in the face of racism and red tape. As an aerial gunner, he logged 58 combined missions, 30 on B-24s over Europe (including the legendary Ploesti raid) and 28 more on B-29s over the Pacific.

Between his European and Pacific tours, the war department put Kuroki on a speaking tour. He visited internment campswhere many of his fellow Japanese-Americans were being held. He spoke to civic groups, and one of his speeches is said to have turned the tide of West Coast opinion about Japanese-Americans.

Few have faced as much to risk their life for an ungrateful nation. Even now, the 90-year-old retired newspaper editor asks, “Why the hell did I do it? I mean, why did I go to that extent? I was just young. I had no family – no children or wife or anything like that. I was all gung-ho to prove my loyalty.”

A new documentary film about Kuroki, “Most Honorable Son,” premiered in Lincoln in August and will be broadcast on PBS in September. For filmmaker Bill Kubota, who grew up hearing his father tell of Kuroki’s visit to the camp at which he was interned, Kuroki’s story is unique.

“It’s very rare you find one person that can carry a lot of different themes of the war with their own personal experience,” Kubota said. “He saw so many different things… It’s a remarkable story no matter who it is, but throw in the fact he’s basically the first Japanese-American war hero and you have even more of a story. He’s more than a footnote in Japanese-American history. One that needs to be better understood and more heard from. It’s a unique, different story that not only Asian Americans can relate to, but all Americans. That’s why I like this story.”

For years after the war he kept silent about his exploits. The humble Kuroki, like most of his generation, did not want a fuss made about events long past. He married, raised a family and worked as a newspaper publisher-editor, first with the York (Neb.) Republican and then the Williamston (Mich.) Enterprise. He later moved to Calif. where he worked as an editor with the Ventura Star-Free Press.

His story resurfaced with WWII 50th anniversary observances in the 1990s. At the invitation of the Nebraska State Historical Society he cut the ribbon for a new war exhibit. On the anniversary of Pearl Harbor he was the subject of a glowing New York Times editorial. More recently, he’s been feted with honors by the Nebraska Press Association and his alma mater, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. As a result of all the new-found attention Kuroki and Shige have been invited guests to the White House on several occasions, most recently in May.

One key to what Kuroki calls his “all guts no brains” loyalty is his upbringing. His parents “pounded it into their children to never bring shame to yourself or your family,” he says in the film. “I hated the fact I was born Japanese. I wanted to try and avenge what they (Japan) had done for causing what we considered shame.”

From his home in Camarillo, Calif., where he lives with his wife, Shige, Kuroki added, “But I think in the long run I have to thank my Nebraska upbringing, my Nebraska roots for playing a real credible role in giving me a solid foundation for patriotism. It really was a way of life. Freedom was always something really I had the best of.”

Kuroki came from a poor family of 10 children. His parents emigrated from Japan with scant schooling and speaking no English. His father, Sam, arrived in San Francisco and worked his way west on Union Pacific section crews. The sight of fertile Nebraska land was enough to make the former sash salesman stay and become a farmer.

A small Japanese enclave formed in western Nebraska. Times were hard during the Great Depression and the years of drought, but Ben enjoyed a bucolic American youth, playing sports, hunting with friends and trucking potatoes down south and returning with fresh citrus.

Though accepted by the white majority, the newcomers were always aware they were different. “But at the same time,” Kuroki said, “I never encountered racial prejudice until after Pearl Harbor.”

On December 7, 1941, he was in a North Platte church basement for a meeting of the Japanese American Citizens League, a patriotic group fighting for equality at a time of heightened tensions with Japan. Mike Masaoka from the JACL national office was chairing the meeting when two men entered the hall and, without explanation, said something to Masaoka and led him out.

“Just like that, he was gone. We were just baffled,” Kuroki said, “so we just sort of scattered and by the time we got outside the church someone had a radio and said, ‘My God, Pearl Harbor has been bombed by the Japanese.’ That was a helluva experience for us the way we found out… It really was a traumatic day.”

They soon learned that Masaoka had been arrested by the FBI and jailed in North Platte. “I guess all suspects, so to speak, were taken into custody,” Kuroki said. Masaoka was soon released, but his arrest presaged the restrictive measures soon imposed on all Japanese-Americans. As part of the crackdown, their assets – including bank accounts – were frozen. As hysteria built on the West Coast, Executive Order 9066 forced the evacuation and relocation of individuals and entire families. Homes and jobs were lost, lives disrupted. As the Kurokis lived in the Midwest, they were spared internment.

Soon after Pearl Harbor, Kuroki and his younger brother Fred were surprised when their father urged them to volunteer for the armed services. As Kuroki recalls in the film, their father said, “This is your country, go ahead and fight for it.”

They went to the induction center in North Platte. They passed all the tests but kept waiting for their names to be called. “We knew we were getting the runaround then because all our friends in Hershey were going in right and left,” Kuroki said. The brothers left in frustration. “It was about two weeks later I heard this radio broadcast that the Air Corps was taking enlistments in Grand Island and so I immediately got on the phone and asked the recruiting sergeant if our nationality was any problem, and he said, ‘Hell, no, I get two bucks for everybody I sign up. C’mon down.’ So we drove 150 miles and gave our pledge of allegiance.”

The Omaha World-Herald ran a picture of the two brothers taking their loyalty oaths.

While on the train to Sheppard Field, Texas, for recruit training, the brothers got a taste of things to come. Kuroki recalled how “some smart aleck said, ‘What the hell are those damn Japs doing in the Army?’ That was the first shocker.”

Things were tense in the barracks as well. “I’ll never forget this one loudmouth yelled out, ‘I’m going to kill myself some goddamned Japs.’ I didn’t know whether he was talking about me or the enemy and I just felt like I wanted to crawl in a damn hole and hide.”

But at least the brothers had each other’s back. Then, without warning, Fred was transferred to a ditch-digging engineers outfit.

“My God, I feared for my life then,” Kuroki said.

As Kuroki learned, it was the rare Japanese-American who got in or stuck with the Air Corps – almost all served in the segregated 442nd Infantry Regiment that earned distinction. The brothers corresponded a few times during the war. Fred ended up seeing action in the Battle of the Bulge.

From Sheppard Field, Kuroki went to a clerical school in Fort Logan, Colo., and then to Barksdale Field (La.) where the 93rd Bomber Group, made up of B-24s, was being formed. As a clerk, he got stuck on KP several days and nights.

“I knew damn well they were giving me the shaft,” he said. “But I wasn’t about to complain because I was afraid if I did, the same thing would happen to me that happened to my brother – that I’d get kicked out of the Air Corps in a hurry.”

He took extra precautions. “I wouldn’t dare go near one (a B-24 bomber) because I was afraid somebody would think I’m going to do sabotage. That’s the way it was for me for a whole year. I walked on egg shells worried if I made one wrong move, if I was right or wrong, that would be the end of my career,” he said.

Then his worst fear came to pass. Orders were cut for him to transfer out, which would ground him before he ever got over enemy skies. That’s when he made the first of his pleas for a chance to serve his country in combat. He got a reprieve and went with his unit down to Fort Myers, Fla. – the last stop before England. But after three months training, he once again faced a transfer.

“I figured if I didn’t go with them then I’d be doing KP for the rest of my Army life,” he said. “And so I went in and begged with tears in my eyes to my squadron adjutant, Lt. Charles Brannan, and he said, ‘Kuroki, you’re going with us, and that’s that.’ All these decades later I’m forever grateful… because if it wasn’t for him I probably would never have gotten overseas.”

He made it to England – the great Allied staging area for the war in Europe – but he was still a long ways from getting to fly. He was still a clerk. But after the first bombing missions suffered heavy losses, there were many openings on bomber crews for gunners. Not leaving it to chance, he took his cause directly to his officers.

“I begged them for a chance to become an aerial gunner and they sent me to a two-week English gunnery school. I didn’t even fire a round of ammunition.”

In late ’42, Kuroki got word his outfit was headed to North Africa… and he was going with it. It took beseeching the 93rd’s commander, Ted Timberlake, whose unit came to be called The Flying Circus, before Kuroki got the final go-ahead. He was delighted, even though he had “practically no training.” As he would later tell an audience, “I really learned to shoot the hard way – in combat.”

Training or not, he finally felt the embrace of brother airmen around him.

“Once I got into flying missions with a regular crew and I was with my own guys, the whole world changed,” he said. “On my first mission I was just terrified by the enemy gunfire but I suddenly found peace. I mean, for the first time I felt like I belonged. And by God we flew together as a family after that. It was just unbelievable, the rapport. Of course we all knew we’re risking our lives together and fighting to save each others’ lives.”

One of his crewmates dubbed Kuroki “The Most Honorable Son.” It became the nickname of their B-24.

At the same time, Kuroki was reading accounts of extremists calling for all Japanese-Americans to be confined to concentration camps. Some nativists even suggested Japanese-Americans should be deported to Japan after the war.

But by then, Kuroki’s own battles were more with the enemy than with the military apparatus. His first action came on missions targeting the shipping lines of the “Desert Fox,” Erwin Rommel, whose Panzer tank divisions had caused havoc in North Africa. Kuroki was on missions that hit multiple locations in North Africa and Italy.

Kuroki and his crewmates made it through more than a dozen missions without incident. Then, on a return flight in ’43, their plane ran out of fuel and made an emergency landing in Spanish Morocco. Armed Arab horsemen converged on them. They feared for their lives, but Spanish cavalry rode to their rescue. The Spanish held the crew more as reluctant guests than as prisoners. But Kuroki tried to escape.

“I just had to prove my loyalty,” he says in the film. He was caught.

What ensued next was a limbo of bureaucratic haggling over what to do with the captured airmen. They were taken to Spain, where they were told they might sit out the rest of the war. For a time, it was welcome news for the crew, who stayed in luxurious quarters. But soon they felt they were missing out on the most momentous events of their lifetime.

Finally, the way was cleared for them to rejoin the 93rd, which soon moved to England for missions over Europe. Of all those bombing runs, the August 1, 1943 raid on Ploesti, Rumania, is forever burned in Kuroki’s memory. In a daylight mission, 177 B-24s came in at treetop level against heavily-fortified oil refineries deep in enemy territory. Nearly a third of the bombers failed to return. Hundreds of American lives were lost.

The legend of Kuroki grew when he reached the 25-mission rotation limit and volunteered to fly five more. His closest call came on his 30th trip, over Munster, when flak shattered the top of his plexiglass turret just as he ducked.

On an official leave home in early 1944, Kuroki was put to work winning hearts and minds. At a Santa Monica, Calif., rest/rehab center, he gave interviews and met celebrities. Stories about him appeared in Time magazine and the New York Times.

Then he was invited to speak at San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club. In preparation for the talk, Sgt. Bob Evans asked him to outline his experiences on paper, which Evans translated into the moving speech Kuroki gave. “He did a terrific job,” Kuroki said.

But before making the speech, Kuroki tried getting out of it. He was intimidated by the prospect of speaking before white dignitaries, and feared a hostile reception. A newspaper headline announced his appearance as “Jap to Address S.F. Club,” and the story ran next to others condemning Japanese atrocities during the Bataan Death March. Even the officer escorting Kuroki worried how the audience would react. Kuroki was the first Japanese-American to return to the West Coast since the mass evacuation.

“I realized I had a helluva responsibility,” Kuroki said.

Kuroki’s speech was broadcast on radio throughout California, and received wide news coverage.

“I learned more about democracy, for one thing, than you’ll find in all the books, because I saw it in action,” Kuroki told the audience. “When you live with men under combat conditions for 15 months you begin to understand what brotherhood, equality, tolerance and unselfishness really mean. They’re no longer just words…”

He went on to recount how a crewmate caught a piece of flak in his head on a mission. The co-pilot came back to give him a morphine injection, but Kuroki waved him off, remembering training that taught morphine could be fatal to head injuries at high altitude. The wounded airman recovered.

“What difference did it make” what a man’s ancestry was? “We had a job to do and we did it with a kind of comradeship that was the finest thing…”

He described his “nearly continuous struggle” to be assigned a flight crew. How he “wanted to get into combat more than anything in the world, so I kept after it.” How he was “waging two battles – one against the Axis and one against intolerance of my fellow Americans.” The prejudice he felt in basic training was so bad, he said, “I would rather go through my bombing missions again than face” it.

Reports refer to men crying and to a standing ovation that lasted 10 minutes. Kuroki confirmed this. Even his escort was in tears.

The reaction stunned Kuroki. He didn’t realize what it all meant until a letter from Club doyen Monroe Deutsch, University of California at Berkeley vice president, reached him overseas and reported what a difference the address made in tempering anti-Japanese sentiment.

Filmmaker Bill Kubota’s research convinces him that the address brought the matter “back to the forefront around the time it needed to be.” It helped people realize that “this is an issue they should think about and deal with.” Kubota said the speech is little known to most Japanese-American scholars because the JA community was prevented from hearing the talk; vital evidence for its profound effect is in Kuroki’s own files, not in public archives.

Before Kuroki went back overseas he appeared at internment camps in Idaho, where his visits drew mixed responses – enthusiasm from idealistic young Nisei wanting his autograph, but hostility from bitter older factions.

Kuroki’s ardent American patriotism and virulent anti-Japan rhetoric elicited “hissing and booing from some of those dissidents,” he said. “Some started calling me dirty names. This one leader called me a bullshitter. It got pretty bad. I didn’t take it too well. I figured I’d risked my life for the good of Japanese-Americans.”

Among the young Nisei who idolized Kuroki was Kubota’s father, a teenager who was impressed with the dashing, highly-decorated aerial gunner.

“My dad regards him as a hero, which is how pre-draft age Japanese-Americans saw him,” Kubota said. Because of the personal tie, the film “means more to me because it means more to my father than I had earlier realized.”

Liked or not, Kuroki said of his public relations work that he “felt very much used and I wasn’t cut out for that sort of thing. I got my belly full of it. I wanted to quit.”

Once back overseas, his bid for Pacific air duty was soon stalled. When Monroe Deutsch learned that a regulation stood in Kuroki’s way, he and others pressured top military brass to make an exception. Secretary of War Henry Stimson wrote a letter granting permission.

“They certainly were unusual people to go to bat for me at that time when war hysteria was so bad,” Kuroki said.

Even with his clearance, Kuroki still encountered resistance. Twice federal agents tried to keep him from going on flights – once at Kearney (Neb.) Air Base, and then again at Murtha Field (Calif.), where the agents carried sidearms. Each time he had to dig in his barracks bag to produce the Stimson letter.

“My pilot and bombardier were so damn mad because by this time they figured we were just getting harassed for nothing,” he said.

His B-29 crew flew out of Tinian Island, where their bomber was parked next to Enola Gay, the B-29 that would soon drop the first atomic bomb. Meanwhile, the fire bombings of Japanese cities left a horrible imprint.

While on Tinian, Kuroki could move safely about only in daylight, and then only flanked by crewmates, as “trigger-happy” sentries were liable to shoot anyone resembling the enemy. And after completing 58 missions unscathed, Kuroki was nearly murdered by a fellow American. When a drunken G.I. called Kuroki “a dirty Jap,” Kuroki started for him, but was waylaid by a knife to the head. The severe cut landed him in the hospital for the war’s duration.

“Just a fraction of an inch deeper and I wouldn’t be here talking today,” he said. “And it probably would never have happened if he hadn’t called me a Jap.”

As he says in the film, “That’s what my whole war was about – I didn’t want to be called a Jap.” Not “after all I had been through… the insults and all the things that hurt all the way back even in recruiting days.”

The irony that a fellow American, not the enemy, came closest to killing him was a bitter pill. Yet Kuroki has no regrets about serving his country. As Kubota said, “I think he knows what he did is the right thing and he’s proud he did it.”

“My parents were very proud, especially my father,” said Kuroki, who earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses during the war. “I know my dad was always bragging about me.” Kuroki presented his parents with a portrait of himself by Joseph Cummings Chase, whom the Smithsonian commissioned to do a separate portrait. When he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 2005, Kuroki accepted it in his father’s honor.

Outside of Audie Murphy, Kuroki may have ended the war as the best known enlisted man to have served. Newspapers-magazine told his story during the war and a 1946 book, Boy From Nebraska, by Ralph Martin, told his story in-depth. When the war ended, Kuroki’s battles were finally over. He shipped home.

“For three or four months I did what I considered my ‘59th mission’ – I spoke to various groups under the auspices of the East and West Association, which was financed by (Nobel Prize-winning author) Pearl Buck. I spoke to high schools and Rotary clubs and that sort of thing and I got my fill of that. So I came home to relax and to forget about things.”

Kuroki didn’t know what he was going to do next, only that “I didn’t want to go back to farming. I was just kind of kicking around. Then I got inspired to go see Cal (former O’Neill, Neb., newspaperman Carroll Stewart) and that was the beginning of a new chapter in my life.”

Stewart, who as an Army PR man met Kuroki during the war, inspired Kuroki to study journalism at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. After a brief stint with a newspaper, Kuroki bought the York Republican, a legal newspaper with a loyal following but hindered by ancient equipment.

He was held in such high esteem that Stewart joined veteran Nebraska newspapermen Emil Reutzel and Jim Cornwell to help Kuroki produce a 48-page first edition called “Operation Democracy.” The man from whom Kuroki purchased the newspaper said he’d never seen competitors band together to aid a rival like that.

“Considering Ben’s triumphs over wartime odds,” Stewart said, the newspapermen put competition aside and “gathered round to aid him.” What also drew people to Kuroki and still does, Stewart said, was “his humility, eagerness and commitment. Kuroki was sincere and modestly consistent to a fault. He placed everyone’s interests above his own.”

Years later, those same men, led by Stewart, spearheaded the push to get Kuroki the Distinguished Service Medal. Stewart also published a booklet, The Most Honorable Son. Kuroki nixed efforts to nominate him for the Medal of Honor, saying, “I didn’t deserve it.”

“That’s the miracle of the thing,” Kuroki said. “Those same people are still going to bat for me and pulling off all these things. It’s really heartwarming. That’s what makes this country so great. Where in the world would that sort of thing happen?”

Related Articles

- Frank Emi, Defiant World War II Internee, Dies at 94 (nytimes.com)

- Ansel Adams’ Japanese American Internment Camp Photos At MoMA. Shhh! (greg.org)

- A search for truth for Japanese-American internees (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

The Two Wars of Ben Kuroki, Honors Keep Rolling in for Nebraskan Who Defied Prejudice to Become a War Hero

First and Front Streets, San Francisco, California. Exclusion Order posted to direct Japanese Americans living in the first San Francisco section to evacuate. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

I am reposting this article because the person profiled in it is due to receive yet another major honor this Saturday, Nov. 6 (2010).

Ben Kuroki, who grew up in Hershey, Neb., was one of 10 children and did not experience discrimination until he and his brother tried to join the Army right after the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor. Ben was Nisei – an American born of Japanese parents. Kuroki had to fight like hell for the right to fight for his own country.

Finally allowed to become a gunner on a B-24 and flew his first mission in December of 1942. Life expectancy for a bomb crew member was ten missions. Kuroki flew 58 missions — and became the only American during WWII to fly for four separate Air Forces — and the only Japanese American to fly over Japan in combat in WWII.

As Kuroki friend Scott Stewart reports, on Nov. 10 in Washington D.C. Kuroki will receive the prestigious Audie Murphy Award — named after the most decorated American veteran in WWII. The American Veterans Center’s will present the award to Ben Kuroki at their annual conference gala.

Kuroki received little official recognition for his war efforts during his time in the service, but since 2005 the flood gates opened and the honors started flowing.

*Distinguished Service Medal — the Army’s third highest award in 2005 at a ceremony in Lincoln followed by the Nebraska Press Association’s highest honor, the President’s Award and the University of Nebraska honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters.

*Black Tie State Dinner at the White House with Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in 2006

*2007, Lincoln hosted the world premier showing of the PBS documentary on the Kuroki war story Most Honorable Son.

*Presidential Citation from President George W. Bush in May 2008

*Smithsonian dedicated a permanent display on Ben war record, May 2008

At his acceptance speech on Saturday Kuroki will say “words are inadequate to thank my friends who went to bat for me and bestowed incredible honors decades later. Without their support, my war record would not have amounted to a hill of beans. Their dedication is the real story of Americanism and democracy at its very best. I now feel fully vindicated in my fight against surreal odds and ugly discrimination.

The article below is one of several I wrote about Kuroki around the time the documentary about him, Most Honorable Son, was premiering on PBS. I am glad to share the article with first time or repeat visitors to this site.

The Two Wars of Ben Kuroki, Honors Keep Rolling in for Nebraskan Who Defied Prejudice to Become a War Hero

After Pearl Harbor, Ben Kuroki wanted to fight for his country. But as a Japanese-American, he first had to fight against the prejudice and fear of his fellow Americans. The young sergeant from Hershey, Neb., proved equal to the task.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Nebraska Life Magazine

“I had to fight like hell just for the right to fight for my own country,” said Hershey, Neb., native Ben Kuroki. During World War II, he became one of only a handful of Japanese-Americans to see air combat, and was America’s only Nisei (child of Japanese immigrant parents) to see duty over mainland Japan.

For Kuroki, just being in the U.S. Army Air Corps was an anomaly. At the outset of war, Japanese-American servicemenwere kicked out. Young men wanting to enlist encountered roadblocks. Those who enlisted later were mustered out or denied combat assignments. But Kuroki was desperate to prove his loyalty to America, and persisted in the face of racism and red tape. As an aerial gunner, he logged 58 combined missions, 30 on B-24s over Europe (including the legendary Ploesti raid) and 28 more on B-29s over the Pacific.

Between his European and Pacific tours, the war department put Kuroki on a speaking tour. He visited internment campswhere many of his fellow Japanese-Americans were being held. He spoke to civic groups, and one of his speeches is said to have turned the tide of West Coast opinion about Japanese-Americans.

Few have faced as much to risk their life for an ungrateful nation. Even now, the 90-year-old retired newspaper editor asks, “Why the hell did I do it? I mean, why did I go to that extent? I was just young. I had no family – no children or wife or anything like that. I was all gung-ho to prove my loyalty.”

A new documentary film about Kuroki, “Most Honorable Son,” premiered in Lincoln in August and will be broadcast on PBS in September. For filmmaker Bill Kubota, who grew up hearing his father tell of Kuroki’s visit to the camp at which he was interned, Kuroki’s story is unique.

“It’s very rare you find one person that can carry a lot of different themes of the war with their own personal experience,” Kubota said. “He saw so many different things… It’s a remarkable story no matter who it is, but throw in the fact he’s basically the first Japanese-American war hero and you have even more of a story. He’s more than a footnote in Japanese-American history. One that needs to be better understood and more heard from. It’s a unique, different story that not only Asian Americans can relate to, but all Americans. That’s why I like this story.”

For years after the war he kept silent about his exploits. The humble Kuroki, like most of his generation, did not want a fuss made about events long past. He married, raised a family and worked as a newspaper publisher-editor, first with the York (Neb.) Republican and then the Williamston (Mich.) Enterprise. He later moved to Calif. where he worked as an editor with the Ventura Star-Free Press.

His story resurfaced with WWII 50th anniversary observances in the 1990s. At the invitation of the Nebraska State Historical Society he cut the ribbon for a new war exhibit. On the anniversary of Pearl Harbor he was the subject of a glowing New York Times editorial. More recently, he’s been feted with honors by the Nebraska Press Association and his alma mater, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. As a result of all the new-found attention Kuroki and Shige have been invited guests to the White House on several occasions, most recently in May.

One key to what Kuroki calls his “all guts no brains” loyalty is his upbringing. His parents “pounded it into their children to never bring shame to yourself or your family,” he says in the film. “I hated the fact I was born Japanese. I wanted to try and avenge what they (Japan) had done for causing what we considered shame.”

From his home in Camarillo, Calif., where he lives with his wife, Shige, Kuroki added, “But I think in the long run I have to thank my Nebraska upbringing, my Nebraska roots for playing a real credible role in giving me a solid foundation for patriotism. It really was a way of life. Freedom was always something really I had the best of.”

Kuroki came from a poor family of 10 children. His parents emigrated from Japan with scant schooling and speaking no English. His father, Sam, arrived in San Francisco and worked his way west on Union Pacific section crews. The sight of fertile Nebraska land was enough to make the former sash salesman stay and become a farmer.

A small Japanese enclave formed in western Nebraska. Times were hard during the Great Depression and the years of drought, but Ben enjoyed a bucolic American youth, playing sports, hunting with friends and trucking potatoes down south and returning with fresh citrus.

Though accepted by the white majority, the newcomers were always aware they were different. “But at the same time,” Kuroki said, “I never encountered racial prejudice until after Pearl Harbor.”

On December 7, 1941, he was in a North Platte church basement for a meeting of the Japanese American Citizens League, a patriotic group fighting for equality at a time of heightened tensions with Japan. Mike Masaoka from the JACL national office was chairing the meeting when two men entered the hall and, without explanation, said something to Masaoka and led him out.

“Just like that, he was gone. We were just baffled,” Kuroki said, “so we just sort of scattered and by the time we got outside the church someone had a radio and said, ‘My God, Pearl Harbor has been bombed by the Japanese.’ That was a helluva experience for us the way we found out… It really was a traumatic day.”

They soon learned that Masaoka had been arrested by the FBI and jailed in North Platte. “I guess all suspects, so to speak, were taken into custody,” Kuroki said. Masaoka was soon released, but his arrest presaged the restrictive measures soon imposed on all Japanese-Americans. As part of the crackdown, their assets – including bank accounts – were frozen. As hysteria built on the West Coast, Executive Order 9066 forced the evacuation and relocation of individuals and entire families. Homes and jobs were lost, lives disrupted. As the Kurokis lived in the Midwest, they were spared internment.

Soon after Pearl Harbor, Kuroki and his younger brother Fred were surprised when their father urged them to volunteer for the armed services. As Kuroki recalls in the film, their father said, “This is your country, go ahead and fight for it.”

They went to the induction center in North Platte. They passed all the tests but kept waiting for their names to be called. “We knew we were getting the runaround then because all our friends in Hershey were going in right and left,” Kuroki said. The brothers left in frustration. “It was about two weeks later I heard this radio broadcast that the Air Corps was taking enlistments in Grand Island and so I immediately got on the phone and asked the recruiting sergeant if our nationality was any problem, and he said, ‘Hell, no, I get two bucks for everybody I sign up. C’mon down.’ So we drove 150 miles and gave our pledge of allegiance.”

The Omaha World-Herald ran a picture of the two brothers taking their loyalty oaths.

While on the train to Sheppard Field, Texas, for recruit training, the brothers got a taste of things to come. Kuroki recalled how “some smart aleck said, ‘What the hell are those damn Japs doing in the Army?’ That was the first shocker.”

Things were tense in the barracks as well. “I’ll never forget this one loudmouth yelled out, ‘I’m going to kill myself some goddamned Japs.’ I didn’t know whether he was talking about me or the enemy and I just felt like I wanted to crawl in a damn hole and hide.”

But at least the brothers had each other’s back. Then, without warning, Fred was transferred to a ditch-digging engineers outfit.

“My God, I feared for my life then,” Kuroki said.

As Kuroki learned, it was the rare Japanese-American who got in or stuck with the Air Corps – almost all served in the segregated 442nd Infantry Regiment that earned distinction. The brothers corresponded a few times during the war. Fred ended up seeing action in the Battle of the Bulge.

From Sheppard Field, Kuroki went to a clerical school in Fort Logan, Colo., and then to Barksdale Field (La.) where the 93rd Bomber Group, made up of B-24s, was being formed. As a clerk, he got stuck on KP several days and nights.

“I knew damn well they were giving me the shaft,” he said. “But I wasn’t about to complain because I was afraid if I did, the same thing would happen to me that happened to my brother – that I’d get kicked out of the Air Corps in a hurry.”

He took extra precautions. “I wouldn’t dare go near one (a B-24 bomber) because I was afraid somebody would think I’m going to do sabotage. That’s the way it was for me for a whole year. I walked on egg shells worried if I made one wrong move, if I was right or wrong, that would be the end of my career,” he said.

Then his worst fear came to pass. Orders were cut for him to transfer out, which would ground him before he ever got over enemy skies. That’s when he made the first of his pleas for a chance to serve his country in combat. He got a reprieve and went with his unit down to Fort Myers, Fla. – the last stop before England. But after three months training, he once again faced a transfer.

“I figured if I didn’t go with them then I’d be doing KP for the rest of my Army life,” he said. “And so I went in and begged with tears in my eyes to my squadron adjutant, Lt. Charles Brannan, and he said, ‘Kuroki, you’re going with us, and that’s that.’ All these decades later I’m forever grateful… because if it wasn’t for him I probably would never have gotten overseas.”

He made it to England – the great Allied staging area for the war in Europe – but he was still a long ways from getting to fly. He was still a clerk. But after the first bombing missions suffered heavy losses, there were many openings on bomber crews for gunners. Not leaving it to chance, he took his cause directly to his officers.

“I begged them for a chance to become an aerial gunner and they sent me to a two-week English gunnery school. I didn’t even fire a round of ammunition.”

In late ’42, Kuroki got word his outfit was headed to North Africa… and he was going with it. It took beseeching the 93rd’s commander, Ted Timberlake, whose unit came to be called The Flying Circus, before Kuroki got the final go-ahead. He was delighted, even though he had “practically no training.” As he would later tell an audience, “I really learned to shoot the hard way – in combat.”

Training or not, he finally felt the embrace of brother airmen around him.

“Once I got into flying missions with a regular crew and I was with my own guys, the whole world changed,” he said. “On my first mission I was just terrified by the enemy gunfire but I suddenly found peace. I mean, for the first time I felt like I belonged. And by God we flew together as a family after that. It was just unbelievable, the rapport. Of course we all knew we’re risking our lives together and fighting to save each others’ lives.”

One of his crewmates dubbed Kuroki “The Most Honorable Son.” It became the nickname of their B-24.

At the same time, Kuroki was reading accounts of extremists calling for all Japanese-Americans to be confined to concentration camps. Some nativists even suggested Japanese-Americans should be deported to Japan after the war.

But by then, Kuroki’s own battles were more with the enemy than with the military apparatus. His first action came on missions targeting the shipping lines of the “Desert Fox,” Erwin Rommel, whose Panzer tank divisions had caused havoc in North Africa. Kuroki was on missions that hit multiple locations in North Africa and Italy.

Kuroki and his crewmates made it through more than a dozen missions without incident. Then, on a return flight in ’43, their plane ran out of fuel and made an emergency landing in Spanish Morocco. Armed Arab horsemen converged on them. They feared for their lives, but Spanish cavalry rode to their rescue. The Spanish held the crew more as reluctant guests than as prisoners. But Kuroki tried to escape.

“I just had to prove my loyalty,” he says in the film. He was caught.

What ensued next was a limbo of bureaucratic haggling over what to do with the captured airmen. They were taken to Spain, where they were told they might sit out the rest of the war. For a time, it was welcome news for the crew, who stayed in luxurious quarters. But soon they felt they were missing out on the most momentous events of their lifetime.

Finally, the way was cleared for them to rejoin the 93rd, which soon moved to England for missions over Europe. Of all those bombing runs, the August 1, 1943 raid on Ploesti, Rumania, is forever burned in Kuroki’s memory. In a daylight mission, 177 B-24s came in at treetop level against heavily-fortified oil refineries deep in enemy territory. Nearly a third of the bombers failed to return. Hundreds of American lives were lost.

The legend of Kuroki grew when he reached the 25-mission rotation limit and volunteered to fly five more. His closest call came on his 30th trip, over Munster, when flak shattered the top of his plexiglass turret just as he ducked.

On an official leave home in early 1944, Kuroki was put to work winning hearts and minds. At a Santa Monica, Calif., rest/rehab center, he gave interviews and met celebrities. Stories about him appeared in Time magazine and the New York Times.

Then he was invited to speak at San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club. In preparation for the talk, Sgt. Bob Evans asked him to outline his experiences on paper, which Evans translated into the moving speech Kuroki gave. “He did a terrific job,” Kuroki said.

But before making the speech, Kuroki tried getting out of it. He was intimidated by the prospect of speaking before white dignitaries, and feared a hostile reception. A newspaper headline announced his appearance as “Jap to Address S.F. Club,” and the story ran next to others condemning Japanese atrocities during the Bataan Death March. Even the officer escorting Kuroki worried how the audience would react. Kuroki was the first Japanese-American to return to the West Coast since the mass evacuation.

“I realized I had a helluva responsibility,” Kuroki said.

Kuroki’s speech was broadcast on radio throughout California, and received wide news coverage.

“I learned more about democracy, for one thing, than you’ll find in all the books, because I saw it in action,” Kuroki told the audience. “When you live with men under combat conditions for 15 months you begin to understand what brotherhood, equality, tolerance and unselfishness really mean. They’re no longer just words…”

He went on to recount how a crewmate caught a piece of flak in his head on a mission. The co-pilot came back to give him a morphine injection, but Kuroki waved him off, remembering training that taught morphine could be fatal to head injuries at high altitude. The wounded airman recovered.

“What difference did it make” what a man’s ancestry was? “We had a job to do and we did it with a kind of comradeship that was the finest thing…”

He described his “nearly continuous struggle” to be assigned a flight crew. How he “wanted to get into combat more than anything in the world, so I kept after it.” How he was “waging two battles – one against the Axis and one against intolerance of my fellow Americans.” The prejudice he felt in basic training was so bad, he said, “I would rather go through my bombing missions again than face” it.

Reports refer to men crying and to a standing ovation that lasted 10 minutes. Kuroki confirmed this. Even his escort was in tears.

The reaction stunned Kuroki. He didn’t realize what it all meant until a letter from Club doyen Monroe Deutsch, University of California at Berkeley vice president, reached him overseas and reported what a difference the address made in tempering anti-Japanese sentiment.

Filmmaker Bill Kubota’s research convinces him that the address brought the matter “back to the forefront around the time it needed to be.” It helped people realize that “this is an issue they should think about and deal with.” Kubota said the speech is little known to most Japanese-American scholars because the JA community was prevented from hearing the talk; vital evidence for its profound effect is in Kuroki’s own files, not in public archives.

Before Kuroki went back overseas he appeared at internment camps in Idaho, where his visits drew mixed responses – enthusiasm from idealistic young Nisei wanting his autograph, but hostility from bitter older factions.

Kuroki’s ardent American patriotism and virulent anti-Japan rhetoric elicited “hissing and booing from some of those dissidents,” he said. “Some started calling me dirty names. This one leader called me a bullshitter. It got pretty bad. I didn’t take it too well. I figured I’d risked my life for the good of Japanese-Americans.”

Among the young Nisei who idolized Kuroki was Kubota’s father, a teenager who was impressed with the dashing, highly-decorated aerial gunner.

“My dad regards him as a hero, which is how pre-draft age Japanese-Americans saw him,” Kubota said. Because of the personal tie, the film “means more to me because it means more to my father than I had earlier realized.”

Liked or not, Kuroki said of his public relations work that he “felt very much used and I wasn’t cut out for that sort of thing. I got my belly full of it. I wanted to quit.”

Once back overseas, his bid for Pacific air duty was soon stalled. When Monroe Deutsch learned that a regulation stood in Kuroki’s way, he and others pressured top military brass to make an exception. Secretary of War Henry Stimson wrote a letter granting permission.

“They certainly were unusual people to go to bat for me at that time when war hysteria was so bad,” Kuroki said.

Even with his clearance, Kuroki still encountered resistance. Twice federal agents tried to keep him from going on flights – once at Kearney (Neb.) Air Base, and then again at Murtha Field (Calif.), where the agents carried sidearms. Each time he had to dig in his barracks bag to produce the Stimson letter.

“My pilot and bombardier were so damn mad because by this time they figured we were just getting harassed for nothing,” he said.

His B-29 crew flew out of Tinian Island, where their bomber was parked next to Enola Gay, the B-29 that would soon drop the first atomic bomb. Meanwhile, the fire bombings of Japanese cities left a horrible imprint.

While on Tinian, Kuroki could move safely about only in daylight, and then only flanked by crewmates, as “trigger-happy” sentries were liable to shoot anyone resembling the enemy. And after completing 58 missions unscathed, Kuroki was nearly murdered by a fellow American. When a drunken G.I. called Kuroki “a dirty Jap,” Kuroki started for him, but was waylaid by a knife to the head. The severe cut landed him in the hospital for the war’s duration.

“Just a fraction of an inch deeper and I wouldn’t be here talking today,” he said. “And it probably would never have happened if he hadn’t called me a Jap.”

As he says in the film, “That’s what my whole war was about – I didn’t want to be called a Jap.” Not “after all I had been through… the insults and all the things that hurt all the way back even in recruiting days.”

The irony that a fellow American, not the enemy, came closest to killing him was a bitter pill. Yet Kuroki has no regrets about serving his country. As Kubota said, “I think he knows what he did is the right thing and he’s proud he did it.”

“My parents were very proud, especially my father,” said Kuroki, who earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses during the war. “I know my dad was always bragging about me.” Kuroki presented his parents with a portrait of himself by Joseph Cummings Chase, whom the Smithsonian commissioned to do a separate portrait. When he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 2005, Kuroki accepted it in his father’s honor.

Outside of Audie Murphy, Kuroki may have ended the war as the best known enlisted man to have served. Newspapers-magazine told his story during the war and a 1946 book, Boy From Nebraska, by Ralph Martin, told his story in-depth. When the war ended, Kuroki’s battles were finally over. He shipped home.

“For three or four months I did what I considered my ‘59th mission’ – I spoke to various groups under the auspices of the East and West Association, which was financed by (Nobel Prize-winning author) Pearl Buck. I spoke to high schools and Rotary clubs and that sort of thing and I got my fill of that. So I came home to relax and to forget about things.”

Kuroki didn’t know what he was going to do next, only that “I didn’t want to go back to farming. I was just kind of kicking around. Then I got inspired to go see Cal (former O’Neill, Neb., newspaperman Carroll Stewart) and that was the beginning of a new chapter in my life.”

Stewart, who as an Army PR man met Kuroki during the war, inspired Kuroki to study journalism at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. After a brief stint with a newspaper, Kuroki bought the York Republican, a legal newspaper with a loyal following but hindered by ancient equipment.

He was held in such high esteem that Stewart joined veteran Nebraska newspapermen Emil Reutzel and Jim Cornwell to help Kuroki produce a 48-page first edition called “Operation Democracy.” The man from whom Kuroki purchased the newspaper said he’d never seen competitors band together to aid a rival like that.

“Considering Ben’s triumphs over wartime odds,” Stewart said, the newspapermen put competition aside and “gathered round to aid him.” What also drew people to Kuroki and still does, Stewart said, was “his humility, eagerness and commitment. Kuroki was sincere and modestly consistent to a fault. He placed everyone’s interests above his own.”

Years later, those same men, led by Stewart, spearheaded the push to get Kuroki the Distinguished Service Medal. Stewart also published a booklet, The Most Honorable Son. Kuroki nixed efforts to nominate him for the Medal of Honor, saying, “I didn’t deserve it.”

“That’s the miracle of the thing,” Kuroki said. “Those same people are still going to bat for me and pulling off all these things. It’s really heartwarming. That’s what makes this country so great. Where in the world would that sort of thing happen?”

Related Articles

- California Apologizes for Past Internment of Italian-Americans (immigration.change.org)

- ‘442’ tells of Japanese American WWII soldiers (sfgate.com)

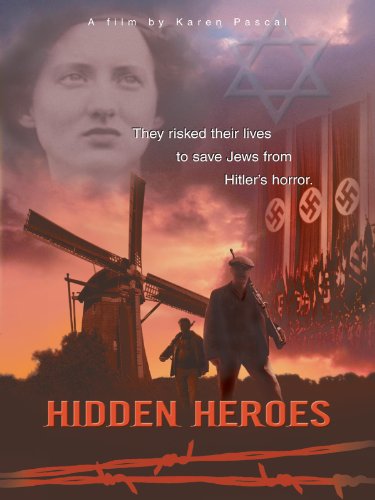

Bringing to light hidden heroes of the Holocaust

A dear friend of mine passed away recently, and as a way of paying homage to him and his legacy I am posting some stories I wrote about him and his mission. My late friend, Ben Nachman, dedicated a good part of his adult life to researching aspects of the Holocaust, which claimed most of his extended family in Europe. Ben became a self-taught historian who focused on collecting the testimonies of survivors and rescuers. It became such a big part of his life that he accumulate a vast library of materials and a large network of contacts from around the world. Ben’s mission was to help develop and disseminate Holocaust history for the purpose of educating the general public, especially youth, and he did this through a variety of means, including videotaped interviews he conducted, sponsoring the development of curriculum for schools, and hosting visiting scholars. He also led this journalist to many stories about Holocaust survivors, rescuers, and educational efforts. Because of Ben I have been privileged to tell something like two dozen Holocaust stories, some of which ended up winning recognition from my peers. I have met some remarkable individuals thanks to Ben. Several of the stories he led me to and that I ended up writing are posted on this blog site under the Holocaust and History categories.

The Hidden Heroes of the Holocaust Foundation that the following article discusses and that Ben founded was eventually absorbed into the Institute for Holocaust Education in Omaha.

Ben’s interests ranged far beyond the Holocaust and therefore his work to preserve history extended to many oral histories he collected from Jewish individuals from all walks of life and speaking to different aspects of Jewish culture. He got me involved in some of these non-Holocaust projects as well through the Nebraska Jewish Historical Society, including a documentary on the Brandeis family of Nebraska and their J.L. Brandeis & Sons department store empire (see my Brandeis story on this blog site) and an in-progress book on Jewish grocers. Ben’s passion for history and his generous spirit for sharing it will be missed. Rest in peace my friend, you were truly one of the righteous.

Bringing to light hidden heroes of the Holocaust

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

A new Omaha foundation is looking to build awareness about an often overlooked chapter of the Holocaust — the rescuers, that small, disparate and courageous band of deliverers whose compassionate actions saved thousands of Jews from genocide. A school-age curriculum crafted by the aptly named Hidden Heroes of the Holocaust Foundation, focusing on the rescue efforts of Swiss diplomat Carl Lutz, is receiving a trial run at Westside High School this spring.

The rescuers came from every station in life. They included civil servants, farmers, shop keepers, nurses, clergy. They hid refugees and exiles wherever they could, often moving their charges from place to place as sanctuaries became unsafe. The mostly Christian rescuers hid Jews in their homes or placed them in convents, monasteries, schools, hospitals or other institutions. As a means of protecting those in their safekeeping, custodians provided new, non-Jewish identities.

While not everyone in hiding survived, many did and behind each story of survival is an accompanying story of rescue. And while not every rescuer acted selflessly — some exacted payment in return for their silence — the heroes that did — and there are more than commonly thought — offer proof that even lone individuals can make a difference against overwhelming odds. These individuals’ noble actions, whether done unilaterally or in concert with organized elements, helped preserve one of Europe’s richest cultural legacies.

Hidden Heroes is the brainchild of Ben Nachman, a retired Omaha dentist who decades ago began an in-depth quest to try and understand the madness that killed 23 members of his Jewish family in the former Ukraine. While his despairing search turned up no satisfactory answers, it did introduce him to Holocaust scholars around the world and to scores of survivors, whose personal stories of survival and rescue he found inspiring.

He said he formed the non-profit foundation “to promote specific Holocaust education efforts and to promote the good deeds of hidden heroes. Most people are aware of only a handful of individuals, like Oscar Schindler or Raoul Wallenberg, who rescued Jews but there were many more who risked their lives to save others. Our mission is to bring to light the stories of these dynamic people and organizations and their little known activities. We hear enough about the bad things that went on. We want to tell the story of the good things and so our focus is on life rather than on death.”

Before he came to celebrate rescuers, Nachman spent years documenting the heroic and defiant stories of survivors. Among the accounts that stirred him most were those of former hidden children residing in Nebraska. Belgian native Dr. Fred Kader avoided deportation through the ultimate sacrifice of his mother, the brave efforts of lay and clergy Christian rescuers and a confluence of fortunate circumstances. Belgian native Dr. Tom Jaeger found refuge through the foresight of his mother and an elaborate network of civilian rescuers, all of whom risked their lives to aid him. Lou Leviticus, a native of Holland, eluded arrest on several occasions through a combination of his own wiles, an active Dutch underground movement and the assistance of Christian families. Nachman interviewed each man for the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Project (now known as the USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education), a worldwide endeavor filmmaker Steven Spielberg started after completing Schindler’s List.

Nachman’s work introduced him to individuals who, despite immeasurable loss, continued embracing life. “I built-up a tremendous love affair with the survivors,” he said. “They’re a wonderful bunch of people. They’ve endured a great deal. They live with what happened every day of their lives, yet hatred is not there — and they’ve got every reason in the world to hate. They’re the most morally correct people I’ve ever found. They’re my heroes.”

As he heard story after story of how survivors owed their lives to the actions of total strangers, the more curious he became about the men and women who defied the Nazi death machine by harboring and transporting Jews, falsifying documents, bribing officials and doing whatever else was necessary to keep the wolves at bay. “I got very interested in the rescuers of Jews,” he said. “I was interested in knowing what made them do what they did. I think most of them did it because of their own personal convictions rather than out of some government mandate. For them, it was the only thing to do. They were very, very special people.”

One rescuer in particular captured his imagination — the late Carl Lutz, a Swiss diplomat credited with saving 62,000 Jews in Hungary while posted to Budapest as vice consul during the Second World War. At the center of an elaborate conspiracy of hearts, Lutz defied all the odds in devising, implementing and maintaining a mammoth rescue operation in cooperation with members of the Jewish underground, the Chalutzim, and select Swiss and Hungarian officials. He established protective papers and safe houses that helped thousands avoid deportation and almost certain death in the camps.

It is a story of how one seemingly insignificant statesman acted with uncommon courage in the face of enormous evil and personal risk and to do all this despite extreme pressure from Hungarian-German authorities and even his own superiors in Berne to stop. The more he has studied him, the more Nachman has come to admire Lutz, who died in 1975 — long before international acclaim caught up to him, including being named by Israel’s Yad Vashem as a Righteous Among the Nations.

What does he admire most about him? “Probably the fact he acted as a man of conviction rather than as a diplomat. He used the office of Swiss consul to shield a lot of what he was doing, but he did things he didn’t have to do. He was just an obstinate, stubborn man who felt right was the only way to go. Lutz was a very devout man and he felt he wanted to be on the side of God, not man.”

Nachman began searching for a way to make known to a wider audience little known acts of heroism like Lutz’s. In 2000 he and some friends, including former hidden child Lou Leviticus of Lincoln, formed Hidden Heroes. With Nachman as its president and guiding spirit, the foundation is a vehicle for researching, producing and distributing historically-based educational materials that reveal rarely told stories of rescue and resistance. It is the hope of Nachman and his fellow board members that the stories the foundation surfaces cast some light and hope on what is one of the darkest and bleakest chapters in human history.

One of the foundation’s first education projects, a curriculum program focusing on Lutz’s rescue efforts, is being piloted at Westside this spring. The curriculum, entitled Carl Lutz: Dangerous Diplomacy, includes a teacher’s guide, grade appropriate lesson plans, reading assignments, discussion activities and classroom resources, including extensive links to selected Holocaust web sites.

The curriculum was written by Christina Micek, a Holocaust studies graduate student and a third grade teacher at Springlake Elementary School in Omaha. With programs designed for the sixth and eighth grades and another for high school, Micek based the materials on the definitive book about Lutz and his heroic work in Hungary, Dangerous Diplomacy: The Story of Carl Lutz, Rescuer of 62,000 Hungarian Jews (2000, Eerdmans Publishing Co.) by noted Swiss historian Theo Tschuy, a consultant with the foundation. Micek developed the curriculum with the input of Tschuy, who made a foundation-sponsored speaking tour across Nebraska last winter.

Foundation secretary/treasurer Ellen Wright said, “The Holocaust was obviously one of the biggest travesties in history and we feel it is valuable to tell the stories of individuals like Carl Lutz who rose to the occasion and acted righteously.” Wright, who away from the foundation is deputy director of the Watanabe Charitable Trust, said the foundation wants the story of Lutz and other rescuers to serve as models for youths about how individuals can stand up to injustice and intolerance.

“Our youths’ heroes today are athletes and entertainers, which is an interesting commentary on our times. What we want to do is add to that plate of heroes by taking a look at an individual like Carl Lutz and seeing that while his actions were extraordinary he was just like you and I. The difference is, he saw a need and became not only impassioned but obsessed by it. When you consider the 62,000 lives he saved you realize he made it possible for generation after generation of descendants to live and do wonderful things around the world. It’s a remarkable feat and that’s what we want to impart.”

Wright added the foundation seeks to eventually make the Lutz curriculum available, at no cost, to schools in Nebraska, across the nation and around the world. In addition to the current curriculum package, she said, plans call for making an interactive CD-ROM as well as Tschuy’s book available to schools.

The idea of Hidden Heroes’ education mission, members say, is to go beyond facts and figures and to instead spark dialogue about what lies at the heart of bigotry and discrimination and to identify what people can do to combat hate. Curriculum author Christina Micek said she wants students using the materials “to get a personal connection to history” and has therefore created lesson plans that allow for discussion and inquiry. She said when dealing with the Holocaust, students should be encouraged to ask questions, search out answers and apply the lessons of the past to their own lives.

“I don’t see teaching history and social studies as something where a teacher is lecturing and the kids are writing down dates,” she said. “I really want students to feel they’re historians and to feel like they know Carl Lutz by the end of it. I want them to take a personal interest in the subject and to analyze the events and to be able to identify some of the moral issues of the Holocaust and to discuss them in an educated manner.”

The sense of discovery and empathy Micek wants the curriculum to inspire in youths is something quite personal for her. Recently, Micek, a Catholic since birth, discovered she is actually part Jewish. Her mother’s German emigre family, the Feldmans, were practicing Catholics as far back as anyone recalled. But the maternal branches of Micek’s family tree were shaken when relatives searching for records of descendants near Frankfurt, Germany came up empty and were instead directed to a local synagogue, where, to their surprise, they found marriage records of Josef Feldman, her maternal great-great-great grandfather.

Like many Jews in Europe hounded by pogroms, the Feldman family hid their Jewish identity and adopted Catholic traditions around the time they emigrated to America in the late 19th century. Some family members remained behind and perished in the Holocaust. This revelation of a lost heritage has been a life-transforming experience for Micek and one that informs her work with the foundation.

“I felt a great personal loss. My family was kind of cheated out of their culture and their religion,” she said. “And so, for me as educator, I feel it’s important that people realize what hate and not understanding other peoples can do to families and cultures. I was attracted to the Hidden Heroes mission because it shows children that, yes, the Holocaust was a terrible tragedy but that were good people who tried to help. It shows something more than the negative side.”

Micek field tested a revised version of the curriculum with her third grade class and found the compelling subject matter had a profound effect on her students.

“My classroom is 80 percent English-As-A-Second-Language children. Most are new immigrants from Mexico, and so they have a first-hand experience of what it is like to be discriminated against. They could relate to the prejudice Jews endured. It provided my class with a wonderful discussion forum to get into the issues raised by the Holocaust. I thought the kinds of questions my kids came up with were very adult: Why do people hate? How can we keep people from hating other people? It turned out to be really in-depth.

“And my kids have kind of become activists around the school based on this lesson. They’re more caring and they try to help other students when they hear negative messages in the hall. It’s gone a lot further than I ever thought it would.”

She anticipates older students using the lesson plan will also be spurred to look beyond the story of Lutz to examine what they can do when confronted with hate. “I hope that, like my third graders did, they take it beyond the classroom and incorporate it into their own lives To understand what prejudice and hate can do and maybe in their own little corner of the world try and make sure that doesn’t happen again.”

According to Tom Carman, head of the department of social studies in the Westside Community Schools, the Lutz curriculum is, for many reasons, an attractive addition to the district’s standard Holocaust studies.

“The material allows us to look beyond Oscar Schindler and Raoul Wallenberg, whose rescue efforts some people view as an aberration, in showing there were a number of people, granted not enough, who did some positive things at that time. It does take that rather depressing topic and give it some ray of hope. I was always looking for something that added some degree of positive humanity to it.

“And while I thought I was fairly familiar with the subject of the Holocaust, I had never heard of Carl Lutz, which surprised me. That was probably the main draw in our incorporating this curriculum. That and the fact it provides a framework for looking at the moral dilemmas posed by the Holocaust.

“Everybody asks, How could that happen? In the final analysis it happened because people allowed it to happen. It prods us to ask whether the pat answers given by perpetrators and witnesses — ‘I was only following orders’ or ‘I didn’t know’ — are acceptable answers because in figures like Carl Lutz we find there were people who behaved differently. Lutz and others said, This is wrong, and did something about it, unlike most people who took a much safer route and either feigned ignorance or looked the other way. It gives examples of people who acted correctly and that teaches there are options out there.”

Bill Hayes, a Westside social studies instructor applying the curriculum in his class, said, “I think it gives a message to kids that you don’t have to just stand by — there is something you can do. There may be some risk, but there is something you can do.”

Carman said the material provided by the Hidden Heroes Foundation is “done very well” and is “really complete.” He added it is written in such a way as to make it readily “adaptable” and “usable” within existing curriculum. District 66 superintendent Ken Bird said it’s rare for a non-profit to offer “a value-added” educational program that “so nicely augments our curriculum as this one does.”

Lutz became the subject of Hidden Heroes’ first major education project due to Nachman’s own extensive research and contacts.

“In my reading I ran across Lutz,” Nachman said, “and in writing, searching and chasing around the world I found his step-daughter, Agnes Hirschi, a writer in Bern, Switzerland. We started corresponding regularly. She introduced me to the man who is the biographer of Lutz — the Rev. Theo Tschuy — a Methodist minister living outside Geneva. He has done tremendous research into the rescuers and he particularly knows the story of Lutz. He and I have become about as close as two people can be.”

Nachman was instrumental in finding an American publisher (Eerdmans) for Tschuy’s book on Lutz. In addition to his work with the foundation, Nachman is a contributor and catalyst for other Holocaust projects. In conjunction with New Destiny Films, a production company with offices in Omaha and Sarasota, Fla., Nachman did research for two documentaries in development.

One film, which Nebraska Public Television may co-produce, profiles survivors who resettled in Nebraska and forged successful lives here, including Drs. Kader and Jaeger, a pediatric neurologist and psychiatrist, respectively, and Lou Leviticus, a retired UNL agricultural engineering professor. The other film, which American Public Television is to distribute, focuses on the rescue that Lutz engineered. The latter film, Carl Lutz: Dangerous Diplomacy, is intended as the first in a series (Hidden Heroes of the Holocaust) on rescuers.

Nachman and New Destiny’s Mike Moehring of Omaha have traveled to Europe to conduct interviews and pore over archives. The Swiss Consulate in Chicago has taken an interest in the Lutz film, providing financial (defraying airfare expenses) and logistical (cutting red-tape) support for research abroad. Swiss Consul General Eduard Jaun, who is excited about the project, said, “This will be the first comprehensive film about Lutz.”

Hidden Heroes is now working on creating new education programs featuring other rescuers. Micek is gathering data for a curriculum focusing on the late Portuguese diplomat Aristides de Sousa Mendes, who while stationed in France signed thousands of visas that spared the lives of their recipients, including many Jews.

Nachman serves on an international committee working to bring worldwide recognition to the humanitarian work of Mendes. Other subjects the foundation is researching are: Father Bruno Reynders, a Benedictine monk who found refuge for more than 200 Jewish children in Belgium; the individuals and organizations behind Belgium’s extensive rescue network, which successfully hid 4,500 children; and the rescue of children on the French and Swiss borders.

Wright said when she approaches potential donors about supporting the foundation she sometimes encounters cynical attitudes along the lines of — “I don’t want to hear anymore about the Holocaust” — which she views as an opportunity to explain what sets Hidden Heroes apart from other Holocaust education initiatives.

“While it’s true there’s a tremendous amount of information out there about the Holocaust,” she said, “what we’re trying to do is take a different approach. Through the stories of survivors and rescuers we want to talk about life. About how survivors did more than just survive — they went on to thrive, raise families and accomplish remarkable things. About how rescuers risked everything to save lives. We want to tell these stories in order to educate young people around the world. It is our hope that behaviors and attitudes can be changed, if even one person at a time, so that something like this never happens again.”

Among others, the foundation’s message of hope is being bought into by funding sources. The foundation recently gained the support of the National Anti-Defamation League, which has promised a major grant to fund its work. Hidden Heroes is close to securing a matching grant from a local donor. The foundation anticipates working cooperatively with the National Hidden Children’s Foundation, which is housed within the National ADL headquarters in New York. More funding is being sought to underwrite foundation research jaunts in Europe.

Because stories of rescue have as their counterpart stories of survival, Hidden Heroes is also involved in raising awareness about the survival experience. In a series of events ranging from receptions to lectures, the foundation presents occasional forums at which former hidden children speak about survival in terms of the trauma it exacts, the defiance it represents and the ultimate triumph over evil it achieves.

For example, the foundation sponsored a November visit by Belgian psychologist and author Marcel Frydman, a former hidden child who spoke about the lifelong ramifications of the hidden child experience, which he describes in his 1999 French-language book, The Trauma of the Hidden Child: Short and Long Term Repercussions. Nachman, who enjoys the role of facilitator, brought Frydman together with Drs. Kader and Jaeger, two countrymen who share his hidden child legacy, for an emotional meeting last fall.

Foundation members say each is participating in the work of the Hidden Heroes organization for his or her own reasons. For Ellen Wright, “it is the right thing to do.” For Nachman, it is a source of fulfillment unlike any other. “There’s nothing I’ve ever done that’s had more meaning and made more of an impact on me,” he said. He noted that as the aging population of survivors and rescuers dwindles each year, there is real urgency to recording the stories of survivors and rescuers before the participants in these stories are all gone.

With reports of anti-Semitism on the rise in Europe and elsewhere in the wake of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian crisis, foundation members say there is even added urgency to telling stories of resilience, resolve and rescue during the Holocaust because these accounts demonstrate how, even in the midst of overwhelming evil, good can prevail.

Related Articles

- ‘American Schindler’ helped 4,000 Jews escape the Nazis (telegraph.co.uk)

- Righteous Gentiles honored in Warsaw (jta.org)

- Leo Adam Biga’s Survivor-Rescuer Stories Featured on Institute for Holocaust Education Website (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Isabella Threlkeld’s lifetime pursuit of art and Ideas yields an uncommon life

UPDATE: As some of you who have recently come to this post know already the subject of this profile, Isabella Threlkeld, passed away March 4, 2012. I met her just a few years before. By the time I met her she was quite on in years and living in a retirement community, but her passion and curiosity for life were undiminished. She will always be one of the more unforgettable characters of my journalistic career. Rest in peace, dear Isabella.

Someone, I don’t remember who now, told me about Isabella Threlkeld, suggesting she’d make an interesting profile subject. To say the least, she did. My New Horizons piece about Isabella follows, and I believe it’s a case in point of how people all around us have fascinating stories if we only take the time and show the interest to search out and learn their tales. As a journalist, I am in a privileged position to seek out people’s stories and to share them with others. For every great story I come upon and end up writing, I can only imagine there are dozens, hundreds, thousands, that I miss or will never have the time to get to. I am only one writer, one storyteller, after all. I am glad I found Isabella and her story. As you’ll read, she is my prototypical profile subject in that she has a great passion and magnificent obsession that permeates every fiber of her being. During the course of several conversations I had with her before the interview and then during the interview and in subsequent conversations, she described an unlikely association with Albert Einstein that I wanted to believe but that I couldn’t find any confirmation of. I still want to believe it happened the way she tells it, but even if it didn’t it’s just another manifestation of her passion and magnificent obsession, which are qualities I find irresistible.

Isabella Threlkeld’s lifetime pursuit of art and ideas yields an uncommon life

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Isabella Threlkeld could feel sorry for herself. She chooses not to. She’s too busy enjoying life. The Omaha artist, art enthusiast, collector, instructor and art therapist is still very much engaged in her passion and work at 86. Still a vivacious force of nature whose brassy personality is the life of any gathering.

Opinionated, curious, quick-to-laugh, Isabella loves the stimulation of a good conversation, book or artwork.

Despite compromises to her age she still paints/draws every day, her precious sketchpad never far from her lithe hands. She even has a new exhibition opening Dec. 5 at the Hot Shops Art Center in NoDo.

The show’s Futurism theme perfectly expresses this dynamo’s focus on energy and states of being. Always reading, always exploring, she’s more attuned to the here-and-now and things-to-come than the past. Not that she doesn’t think about her much-traveled, event-filled past. She does. She has a keen appreciation for history and what it teaches. She savors her visits to Mexico, England, Italy, France, Germany, Spain, Greece, Egypt, Morocco, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, all locales she studied in, all cultures she immersed herself in.