Archive

Family of creatives: Rudy Smith, Llana Smith, Q (Quiana) Smith

Family of creatives: Rudy Smith, Llana Smith, Q (Quiana) Smith

©by Leo Adam Biga

Creativity can certainly run in families and one of the most blessed and beloved Omaha families I know of in this regard is the Rudy and Llana Smith family. He’s a photographer. She’s a playwright. One of their adult children, Q (Quiana) Smith, is an actress. Here is a collection of stories I’ve done about them individually over the years.

Rudy Smith

Rudy Smith’s own life is as compelling as any story he ever covered as a photojournalist. Both as a photographer and as a citizen, he was caught up in momentous societal events in the 1960s. This article for The Reader (www.thereader.com) examines some of the things he trained his eye and applied his intellect and gave his heart to — incidents and movements whose profound effects are still felt today. Rudy’s now retired, which only means he now has more time to work on a multitude of personal projects, including a book collaboration with his daughter Quiana, and to spend with his wife, Llana. This blog contains stories I did on Quiana and Llana. I have a feeling I will be writing about Rudy again before too long.

Hidden in plain view, Rudy Smith’s camera and memory fix on critical time in struggle for equality

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

It was another August night in the newsroom when word came of a riot breaking out on Omaha’s near northside. If the report were true, it meant for the second time that summer of 1966 minority discontent was turning violent. Rudy Smith was the young Omaha World-Herald photojournalist who caught the story. His job at the newspaper was paying his way through then-Omaha University, where the Central High grad was an NAACP Youth Council and UNO student senate activist. Only three years before, he became the first black to join the Herald’s editorial staff. As a native north Omahan dedicated to his people’s struggle, Smith brought instant credibility to his assignments in the black community. In line with the paper’s unsympathetic civil rights stance at the time, he was often the only photographer sent to the near northside.

“And in many cases my colleagues didn’t want to go. They were fearful of the minority community, and so as a result I covered it. They would just send me,” said Smith, a mellow man whose soft voice disguises a fierce conviction. “As a result, the minority community that never had access to the World-Herald before began to gain access. More stories began to be written and more of the issues concerning north Omaha began to be reported, and from a more accurate perspective.”

It was all part of his efforts “to break down the barriers and the stereotypes.”

Archie Godfrey led the local NAACP Youth Council then. He said Smith’s media savvy made him “our underground railroad” and “bridge” to the system and the general public. “Without his leadership and guidance, we wouldn’t of had a ghost of an understanding of the ins and outs of how the media responds to struggles like ours,” said Godfrey, adding that Smith helped the group craft messages and organize protests for maximum coverage.

More than that, he said, Smith was sought out by fellow journalists for briefings on the state of black Omaha. “A lot of times, they didn’t understand the issues. And when splinter groups started appearing that had their own agendas and axes to grind, it became confusing. Reporters came to Rudy to sound him out and to get clarification. Rudy was familiar with the players. He informed people as to what was real and what was not. He didn’t play favorites. But he also never hid behind that journalistic neutrality. He was right out front. He had the pictures, too. This city will probably never know the balancing act he played in that.”

As a journalist and community catalyst, Smith has straddled two worlds. In one, he’s the objective observer from the mainstream press. In the other, he’s a black man committed to seeing his community’s needs are served. Somehow, he makes both roles work without being a sell out to either cause.

“My integrity has never been an issue,” he said. “As much as I’d like to be involved in the community, I can’t be, because sometimes there are things I have to report on and I don’t want to compromise my professionalism. My life is kind of hidden in plain view. I monitor what’s going on and I let my camera capture the significant things that go on — for a purpose. Those images are stored so that in the next year or two I can put them in book form. Because there are generations coming after me that will never know what really happened, how things changed and who was involved in changing the landscape of Omaha. I want them to have some kind of document that still lives and that they can point to with pride.”

For the deeply religious Smith, nothing’s more important than using “my God-given talents in service of humanity. I look at my life as one of an artist. An artist with a purpose and a mission. I’m driven. I’m working as a journalist on an unfinished masterpiece. My life is my canvas. And the people and the events I experience are the things that go onto my canvas. There is a lot of unfinished business still to be pursued in terms of diversity and opportunity. To me, my greatest contributions have yet to be made. It’s an ongoing process.”

The night of the riot, Smith didn’t know what awaited him, only that his own community was in trouble. He drove to The Hood, leaving behind the burnt orange hard hat a colleague gave him back at the office.

“I knew the area real well. I parked near 20th and Grace Streets and I walked through the alleys and back yards to 24th Street, and then back to 23rd.”

Most of the fires were concentrated on 24th. A restaurant, shoe shine parlor and clothing store were among the casualties. Then he came upon a church on fire. It was Paradise Baptist, where he attended as a kid.

“I cussed, repeating over and over, ‘My church, my church, my church,’ and I started taking pictures. Then I heard — ‘Hey, what are you doing here?’ — and there were these two national guardsmen pointing their guns at me. ‘I’m with the World-Herald,’ I said. I kept snapping away. Then, totally disregarding what I said, they told me, ‘Come over here.’ This one said to the other, ‘Let’s shoot this nigger,’ and went to me, ‘C’mon,’ and put the nuzzle of his rifle to the back of my head and pushed me around to the back of the building. As we went around there, I heard that same one say, ‘There ain’t nobody back here. Let’s off him, he’s got no business being here anyway.’ I was scared and looking around for help.

That’s when I saw a National Guard officer, the mayor and some others about a half-block away. I called out, ‘Hey! Hey! Hey!’ ‘Who is it?’ ‘Rudy Smith, World-Herald.’ ‘What the hell are you doing here?’ ‘I’m taking pictures and these two guys are going to shoot me.’ The officer said, ‘C’mon over here.’ ‘Well, they aren’t going to let me.’ ‘Come here.’ So, I went…those two guys still behind me. I told the man again who I was and what I was doing, and he goes, ‘Well, you have no damn business being here. You know you could have been killed? You gotta get out of here.’ And I did. But I got a picture of the guardsmen standing in front of that burning church, silhouetted by the fire, their guns on their shoulders. The Herald printed it the next day.”

Seeing his community go up in flames, Smith said, “was devastating.” The riots precipitated the near northside’s decline. Over the years, he’s chronicled the fall of his community. In the riots’ aftermath, many merchants and residents left, with only a shell of the community remaining. Just as damaging was the later North Freeway construction that razed hundreds of homes and uprooted as many families. In on-camera comments for the UNO Television documentary Omaha Since World War II, Smith said, “How do you prepare for an Interstate system to come through and divide a community that for 60-70 years was cohesive? It was kind of like a big rupture or eruption that just destroyed the landscape.” He said in the aftermath of so much destruction, people “didn’t see hope alive in Omaha.”

Today, Smith is a veteran, much-honored photojournalist who does see a bright future for his community. “I’m beginning to see a revival and resurgence in north Omaha, and that’s encouraging. It may not come to fruition in my lifetime, but I’m beginning to see seeds being planted in the form of ideas, directions and new leaders that will eventually lead to the revitalization of north Omaha,” he said.

His optimism is based, in part, on redevelopment along North 24th. There are streetscape improvements underway, the soon-to-open Loves Jazz and Cultural Arts Center, a newly completed jazz park, a family life center under construction and a commercial strip mall going up. Then there’s the evolving riverfront and Creighton University expansion just to the south. Now that there’s momentum building, he said it’s vital north Omaha directly benefit from the progress. Too often, he feels that historically disenfranchised north Omaha is treated as an isolated district whose problems and needs are its own. The reality is that many cross-currents of commerce and interest flow between the near northside and wider (read: whiter) Omaha. Inner city residents work and shop outside the community just as residents from other parts of the city work in North O or own land and businesses there.

“What happens in north Omaha affects the entire city,” Smith said. “When you come down to it, it’s about economics. The north side is a vital player in the vitality and the health of the city, particularly downtown. If downtown is going to be healthy, you’ve got to have a healthy surrounding community. So, everybody has a vested interest in the well-being of north Omaha.”

It’s a community he has deep ties to. His involvement is multi-layered, ranging from the images he makes to the good works he does to the assorted projects he takes on. All of it, he said, is “an extension of my faith.” He and his wife of 37 years, Llana, have three grown children who, like their parents, have been immersed in activities at their place of worship, Salem Baptist Church. Church is just one avenue Smith uses to strengthen and celebrate his community and his people.

With friend Edgar Hicks he co-founded the minority investment club, Mite Multipliers. With Great Plains Black Museum founder Bertha Calloway and Smithsonian Institute historian Alonzo Smith he collaborated on the 1999 book, Visions of Freedom on the Great Plains: An Illustrated History of African Americans in Nebraska. Last summer, he helped bring a Negro Leagues Baseball Museum exhibit to the Western Heritage Museum. Then there’s the book of his own photos and commentary he’s preparing. He’s also planning a book with his New York theater actress daughter, Quiana, that will essay in words and images the stories of the American theater’s black divas. And then there’s the petition drive he’s heading to get Marlin Briscoe inducted into the National Football League Hall of Fame.

Putting others first is a Smith trait. The second oldest of eight siblings, he helped provide for and raise his younger brothers and sisters. His father abandoned the family after he was conceived. Smith was born in Philadelphia and his mother moved the family west to Omaha, where her sister lived. His mother remarried. She was a domestic for well-to-do whites and a teenaged Rudy a servant for black Omaha physician W.W. Solomon. Times were hard. The Smiths lived in such squalor that Rudy called their early residence “a Southern-style shotgun house” whose holes they “stuffed with rags, papers, and socks. That’s what we call caulking today,” he joked. When, at 16, his step-father died in a construction accident, Rudy’s mother came to him and said, “‘You’re going to take over as head of the family.’ And I said, ‘OK.’ To me, it was just something that had to be done.”

Smith’s old friend from the The Movement, Archie Godfrey, recalled Rudy as “mature beyond his years. He had more responsibilities than the rest of us had and still took time to be involved. He’s like a rock. He’s just been consistent like that.”

“I think my hardships growing up prepared me for what I had to endure and for decisions I had to make,” Smith said. “I was always thrust into situations where somebody had to step up to the front…and I’ve never been afraid to do that.”

When issues arise, Smith’s approach is considered, not rash, and reflect an ideology influenced by the passive resistance philosophies and strategies of such diverse figures as Machiavelli, Gandhi and King as well as the more righteous fervor of Malcolm X. Smith said a publication that sprang from the black power movement, The Black Scholar, inspired he and fellow UNO student activists to agitate for change. Smith introduced legislation to create UNO’s black studies department, whose current chair, Robert Chrisman, is the Scholar’s founder and editor. Smith also campaigned for UNO’s merger with the University of Nebraska system. More recently, he advocated for change as a member of the Nebraska Affirmative Action Advisory Committee, which oversees state departmental compliance with federal mandates for enhanced hiring, promotion and retention of minorities and women.

The camera, though, remains his most expressive tool. Whether it’s a downtown demonstration brimming with indignation or the haunted face of an indigent man or an old woman working a field or Robert Kennedy stumping in North O, his images capture poignant truth. “For some reason, I always knew whatever I shot was for historical purposes,” he said. “When it’s history, that moment will never be revisited again. Words can describe it, but images live on forever. Just like freedom marches on.”

Rudy Smith was a lot of places where breaking news happened. That was his job as an Omaha World-Herald photojournalist. Early in his career he was there when riots broke out on the Near Northside, the largely African-American community he came from and lived in. He was there too when any number of civil rights events and figures came through town. Smith himself was active in social justice causes as a young man and sometimes the very events he covered he had an intimate connection with in his private life. The following story keys off an exhibition of his work from a few years ago that featured his civil rights-social protest photography from the 1960s. You’ll find more stories about Rudy, his wife Llana, and their daughter Quiana on this blog.

Brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Coursing down North 24th Street in his car one recent afternoon, Rudy Smith retraced the path of the 1969 summer riots that erupted on Omaha’s near northside. Smith was a young Omaha World-Herald photographer then.

The disturbance he was sent to cover was a reaction to pent up discontent among black residents. Earlier riots, in 1966 and 1968, set the stage. The flash point for the 1969 unrest was the fatal shooting of teenager Vivian Strong by Omaha police officer James Loder in the Logan Fontenelle Housing projects. As word of the incident spread, a crowd gathered and mob violence broke out.

Windows were broken and fires set in dozens of commercial buildings on and off Omaha’s 24th Street strip. The riot leapfrogged east to west, from 23rd to 24th Streets, and south to north, from Clark to Lake. Looting followed. Officials declared a state of martial law. Nebraska National Guardsmen were called in to help restore order. Some structures suffered minor damage but others went up entirely in flames, leaving only gutted shells whose charred remains smoldered for days.

Smith arrived at the scene of the breaking story with more than the usual journalistic curiosity. The politically aware African-American grew up in the black area ablaze around him. As an NAACP Youth and College Chapter leader, he’d toured the devastation of Watts, trained in nonviolent resistance and advocated for the formation of a black studies program at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he was a student activist. But this was different. This was home.

On the night of July 1 he found his community under siege by some of its own. The places torched belonged to people he knew. At the corner of 23rd and Clark he came upon a fire consuming the wood frame St. Paul Baptist Church, once the site of Paradise Baptist, where he’d worshiped. As he snapped pics with his Nikon 35 millimeter camera, a pair of white National Guard troops spotted him, rifles drawn. In the unfolding chaos, he said, the troopers discussed offing him and began to escort him at gun point to around the back before others intervened.

Just as he was “transformed” by the wreckage of Watts, his eyes were “opened” by the crucible of witnessing his beloved neighborhood going up in flames and then coming close to his own demise. Aspects of his maturation, disillusionment and spirituality are evident in his work. A photo depicts the illuminated church inferno in the background as firemen and guardsmen stand silhouetted in the foreground.

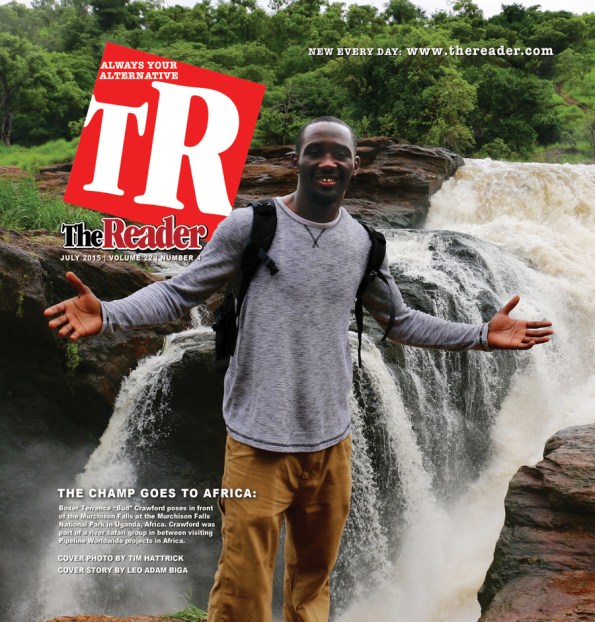

The stark black and white ultrachrome prints Smith made of this and other burning moments from Omaha’s civil rights struggle are displayed in the exhibition Freedom Journeynow through December 23 at Loves Jazz & Arts Center, 2512 North 24th Street. His photos of the incendiary riots and their bleak aftermath, of large marches and rallies, of vigilant Black Panthers, a fiery Ernie Chambers and a vibrant Robert F. Kennedy depict the city’s bumpy, still unfinished road to equality.

The Smith image promoting the exhibit is of a 1968 march down the center of North 24th. Omaha Star publisher and civil rights champion Mildred Brown is in the well-dressed contingent whose demeanor bears funereal solemnity and proud defiance. A man at the head of the procession holds aloft an American flag. For Smith, an image such as this one “portrays possibilities” in the “great solidarity among young, old, white, black, clergy, lay people, radicals and moderates” who marched as one,” he said. “They all represented Omaha or what potentially could be really good about Omaha. When I look at that I think, Why couldn’t the city of Omaha be like a march? All races, creeds, socioeconomic backgrounds together going in one direction for a common cause. I see all that in the picture.”

Images from the OWH archives and other sources reveal snatches of Omaha’s early civil rights experience, including actions by the Ministerial Alliance, Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties, De Porres Club, NAACP and Urban League. Polaroids by Pat Brown capture Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. on his only visit to Omaha, in 1958, for a conference. He’s seen relaxing at the Omaha home of Ed and Bertha Moore. Already a national figure as organizer of the Birmingham (Ala.) bus boycott and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he’s the image of an ambitious young man with much ahead of him. Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, Jr. joined him. Ten years later Smith photographed Robert F. Kennedy stumping for the 1968 Democratic presidential bid amid an adoring crowd at 24th and Erskine. Two weeks later RFK was shot and killed, joining MLK as a martyr for The Cause.

Omaha’s civil rights history is explored side by side with the nation’s in words and images that recreate the panels adorning the MLK Bridge on Omaha’s downtown riverfront. The exhibit is a powerful account of how Omaha was connected to and shaped by this Freedom Journey. How the demonstrations and sit-ins down south had their parallel here. So, too, the riots in places like Watts and Detroit.

Acts of arson and vandalism raged over four nights in Omaha the summer of ‘69. The monetary damage was high. The loss of hope higher. Glimpses of the fall out are seen in Smith’s images of damaged buildings like Ideal Hardware and Carter’s Cafe. On his recent drive-thru the riot’s path, he recited a long list of casualties — cleaners, grocery stores, gas stations, et cetera — on either side of 24th. Among the few unscathed spots was the Omaha Star, where Brown had a trio of Panthers, including David Poindexter, stand guard outside. Smith made a portrait of them in their berets, one, Eddie Bolden, cradling a rifle, a band of ammunition slung across his chest. “They served a valuable community service that night,” he said.

Most owners, black and white, never reopened there. Their handsome brick buildings had been home to businesses for decades. Their destruction left a physical and spiritual void. “It just kind of took the heart out of the community,” Smith said. “Nobody was going to come back here. I heard young people say so many times, ‘I can’t wait to get out of here.’ Many went away to college and never came back. That brain drain hurt. It took a toll on me watching that.”

Boarded-up ruins became a common site for blocks. For years, they stood as sad reminders of what had been lost. Only in the last decade did the city raze the last of these, often leaving only vacant lots and harsh memories in their place. “Some buildings stood like sentinels for years showing the devastation,” Smith said.

His portrait of Ernie Chambers shows an engaged leader who, in the post-riot wake, addresses a crowd begging to know, as Smith said, “Where do we go from here?’

Smith’s photos chart a community still searching for answers four decades later and provide a narrative for its scarred landscape. For him, documenting this history is all about answering questions about “the history of north Omaha and what really happened here. What was on these empty lots? Why are there no buildings there today? Who occupied them?” Minus this context, he said, “it’d be almost as if your history was whitewashed. If we’re left without our history, we perish and we’re doomed to repeat” past ills. “Those images challenge us. That was my whole purpose for shooting them…to challenge people, educate people so their history won’t be forgotten. I want these images to live beyond me to tell their own story, so that some day young people can be proud of what they see good out here because they know from whence it came.”

An in-progress oral history component of the exhibit will include Smith’s personal accounts of the civil rights struggle.

Llana Smith

About a decade ago I became reacquainted with a former University of Nebraska at Omaha adjunct professor of photography, Rudy Smith, who was an award-winning photojournalist with the Omaha World-Herald. I was an abject failure as a photography student, but I have managed to fare somewhat better as a freelance writer-reporter. When I began covering aspects of Omaha‘s African-American community with some consistency, Rudy was someone I reached out to as a source and guide. We became friends along the way. I still call on him from time to time to offer me perspective and leads. I’ve gotten to know a bit of Rudy’s personal story, which includes coming out of poverty and making a life and career for himself as the first African-American employed in the Omaha World-Herald newsroom and agitating for social change on the UNO campus and in greater Omaha.

I have also come to know some members of his immediate family, including his wife Llana and their musical theater daughter Quiana or Q as she goes by professionally. Llana is a sweet woman who has her own story of survival and strength. She and and Rudy are devout Christians active in their church, Salem Baptist, where Llana continues a family legacy of writing-directing gospel dramas. She’s lately taken her craft outside Omaha as well. I have tried getting this story published in print publications to no avail. With no further adieu then, this is Llana’s story:

Gospel playwright Llana Smith enjoys her Big Mama’s time

©by Leo Adam Biga

When the spirit moves Llana Smith to write one of her gospel plays, she’s convinced she’s an instrument of the Lord in the burst of creative expression that follows. It’s her hand holding the pen and writing the words on a yellow note pad alright, but she believes a Higher Power guides her.

“I look at it as a gift. It’s not something I can just do. I’ve got to pray about it and kind of see where the Lord is leading me and then I can write,” said the former Llana Jones. “I’ll start writing and things just come. Without really praying about it I can write the messiest play you ever want to see.”

She said she can only be a vessel if she opens herself up “to be used.” It’s why she makes a distinction between an inspired gift and an innate talent. Her work, increasingly performed around the nation, is part of a legacy of faith and art that began with her late mother Pauline Beverly Jones Smith and that now extends to her daughter Quiana Smith.

The family’s long been a fixture at Salem Baptist Church in north Omaha. Pauline led the drama ministry program — writing-directing dramatic interpretations — before Llana succeeded her in the 1980s. For a time, their roles overlapped, with mom handling the adult drama programs and Llana the youth programs.

“My mother really was the one who started all this out,” Smith said. “She was gifted to do what she did and some of what she did she passed on to me.”

Married to photojournalist Rudy Smith, Llana and her mate’s three children grew up at Salem and she enlisted each to perform orations, sketches and songs. The youngest, Quiana, blossomed into a star vocalist/actress. She appeared on Broadway in a revival of Les Miserables. In 2004 Llana recruited Quiana, already a New York stage veteran by then, to take a featured role in an Easter production of her The Crucifixion: Through the Eyes of a Cross Maker at Salem.

Three generations of women expressing their faith. From one to the next to the other each has passed this gift on to her successor and grown it a bit more.

Pauline recognized it in Llana, who recalled her mother once remarked, “How do you come up with all this stuff? I could never have done that.” To which Llana replied, ‘Well, Mom, it just comes, it’s just a gift. You got it.” Pauline corrected her with, “No, I don’t have it like that. You really have the gift.”

“Them were some of the most important words she ever said to me,” Smith said.

Miss Pauline saw the calling in her granddaughter, too. “My mother would always say, ‘Quiana’s going to be the one to take this further — to take this higher.’ Well, sure enough, she has,” Smith said. “Quiana can write, she can direct, she can act and she can SING. She’s taken it all the way to New York. From my mother’s foundation all the way to what Quiana’s doing, it has just expanded to where we never could have imagined. It just went right on down the line.”

Whether writing a drama extracted from the gospels or lifted right from the streets, Smith is well-versed in the material and the territory. The conflict and redemption of gospel plays resonate with her own experience — from her chaotic childhood to the recent home invasion her family suffered.

Born in a Milford, Neb. home for young unwed mothers, Smith knew all about instability and poverty growing up in North O with her largely absentee, unemployed, single mom. Smith said years later Pauline admitted she wasn’t ready to be a mother then. For a long time Smith carried “a real resentment” about her childhood being stolen away. For example, she cared for her younger siblings while Pauline was off “running the streets.” “I did most of the cooking and cleaning and stuff,” Smith said. With so much on her shoulders she fared poorly in school.

She witnessed and endured physical abuse at the hands of her alcoholic step-father and discovered the man she thought was her daddy wasn’t at all. When her biological father entered her life she found out a school bully was actually her half-sister and a best friend was really her cousin.

It was only when the teenaged Llana married Rudy her mother did a “turnabout” and settled down, marrying a man with children she raised as her own. “She did a good job raising those kids. She became the church clerk. She was very well respected,” said Smith, who forgave her mother despite the abandonment she felt. “She ended up being my best friend. Nobody could have told me that.”

Until then, however, the only security Smith could count on was when her Aunt Annie and Uncle Bill gave her refuge or when she was at church. She’s sure what kept her from dropping out of school or getting hooked on drugs or turning tricks — some of the very things that befell classmates of hers — was her faith.

“Oh, definitely, no question about it, I could have went either way if it hadn’t really been for church.” she said. “It was the one basic foundation we had.”

In Rudy, she found a fellow believer. A few years older, he came from similar straits.

“I was poor and he was poor-poor,” she said. “We both knew we wanted more than what we had. We wanted out of this. We didn’t want it for our kids. To me, it was survival. I had to survive because I was looking at my sister and my brother and if they don’t have me well, then, sometimes they wouldn’t have nobody. I had to make it through. I never had any thought of giving up. I did wonder, Why me? But running away and leaving them, it never crossed my mind. We had to survive.”

Her personal journey gives her a real connection to the hard times and plaintive hopes that permeate black music and drama. She’s lived it. It’s why she feels a deep kinship with the black church and its tradition of using music and drama ministry to guide troubled souls from despair to joy.

Hilltop is a play she wrote about the driveby shootings and illicit drug activities plaguing the Hilltop-Pleasantview public housing project in Omaha. The drama looks at the real-life transformation some gangbangers made to leave it all behind.

Gospel plays use well-worn conventions, characters and situations to enact Biblical stories, to portray moments/figures in history or to examine modern social ills. Themes are interpreted through the prism of the black experience and the black church, lending the dramas an earthy yet moralistic tone. Even the more secular, contemporary allegories carry a scripturally-drawn message.

Not unlike an August Wilson play, you’ll find the hustler, the pimp, the addict, the loan shark, the Gs, the barber, the beauty salon operator, the mortician, the minister, the do-gooder, the gossip, the busy-body, the player, the slut, the gay guy, et cetera. Iconic settings are also popular. Smith’s Big Momma’s Prayer opens at a church, her These Walls Must Come Down switches between a beauty shop and a detail shop and her Against All Odds We Made It jumps back and forth from a nail shop to a hoops court.

The drama, typically infused with healthy doses of comedy, music, singing and dancing, revolves around the poor choices people make out of sheer willfulness. A breakup, an extramarital affair, a bad business investment, a drug habit or a resentment sets events in motion. There’s almost always a prodigal son or daughter that’s drifted away and become alienated from the family.

The wayward characters led astray come back into the fold of family and church only after some crucible. The end is almost always a celebration of their return, their atonement, their rebirth. It is affirmation raised to high praise and worship.

At the center of it all is the ubiquitous Big Mama figure who exists in many black families. This matriarch is the rock holding the entire works together.

“She’s just so real to a lot of us,” Smith said.

Aunt Annie was the Big Mama in Smith’s early life before her mother was finally ready to assume that role. Smith’s inherited the crown now.

If it all sounds familiar then it’s probably due to Tyler Perry, the actor-writer-director responsible for introducing Big Mama or Madea to white America through his popular plays and movies. His big screen successes are really just more sophisticated, secularized versions of the gospel plays that first made him a star. Where his plays originally found huge, albeit mostly black, audiences, his movies have found broad mainstream acceptance.

Madea is Perry’s signature character.

“When Madea talks she be talking stuff everybody can relate to,” Smith said. “Stuff that’s going on. Every day stuff. We can relate to any and everything she be saying. That character’s a trip. It’s the truth. One of my mother’s best friends was just like Madea. She smoked that cigarette, she talked from the corner of her mouth, she could cuss you out at the drop of a hat and she packed her knife in her bosom.”

Smith appreciates Perry’s groundbreaking work. “That is my idol…my icon. At the top of my list is to meet this man and to thank him for what he’s done,” she said. She also likes the fact “he attributes a lot of what he does to the Lord.”

Her own work shows gospel plays’ ever widening reach — with dramas produced at churches and at the Rose and Orpheum Theatres. She first made her mark with Black History Month presentations at Salem with actors portraying such figures as Medgar Evers, Harriet Tubman and Marian Anderson. Her mom once played Jean Pittman. A son played Martin Luther King Jr. She enjoys “bringing history to life.”

Her Easter-Christmas dramas grew ever grander. Much of that time she collaborated with Salem’s then-Minister of Music, Jay Terrell, and dance director, Shirley Terrell-Jordan. Smith’s recently stepped back from Salem to create plays outside Nebraska. That’s something not even her mother did, although Pauline’s Your Arms Are Too Short to Box with God did tour the Midwest and South.

At the urging of Terrell, a Gospel Workshop of America presenter and gospel music composer now at Beulahland Bible Church in Macon, Ga., Smith’s taking her gift “outside the walls of the church.” In 2005 her Big Momma’s Prayer was scored and directed by Terrell for a production at a Macon dinner theater. The drama played to packed houses. A couple years later he provided the music for her These Walls, which Smith directed to overflow audiences at Tabernacle Baptist Church in Wichita, Kansas. In 2008 her Against All Odds was a hit at Oakridge Missionary Baptist Church in Kansas City, Kan., where she, Terrell-Jordan and Jay Terrell worked with some 175 teens in dance-music-drama workshops.

Against All Odds took on new meaning for Smith when she wrote and staged the drama in the aftermath of a home invasion in which an intruder bound and gagged her, Rudy and a foster-daughter. Rudy suffered a concussion. A suspect in the incident was recently arrested and brought up on charges.

Smith’s work with Terrell is another way she continues the path her mother began. Doretha Wade was Salem’s music director when Pauline did her drama thing there. The two women collaborated on Your Arms Are Too Short, There’s a Stranger in Town and many other pieces. Wade brought the Salem Inspirational Choir its greatest triumph when she and gospel music legend Rev. James Cleveland directed the choir in recording the Grammy-nominated album My Arms Feel Noways Tired. Smith, an alto, sang in the choir, is on the album and went to the Grammys in L.A.

Terrell’s been a great encourager of Smith’s work and the two enjoy a collaboration similar to what Doretha and Pauline shared. “To see how Doretha and her worked to bring the music and the drama together was a big influence and, lo and behold, Jay and I have become the same,” she said.

Smith and Terrell have discussed holding gospel play workshops around the country. Meanwhile, she staged an elaborate production at Salem this past Easter. There’s talk of reviving a great big gospel show called Shout! that Llana wrote dramatic skits for and that packed The Rose Theatre. It’s all coming fast and furious for this Big Mama.

“This is like a whole new chapter in my life,” she said.

Quiana Smith

NOTE: I am reposting the following article because its subject, Quiana Smith, who goes by Q. Smith professionally, is back in our shared hometown of Omaha, Neb. with the national Broadway touring production of Mary Poppins. Quiana, recently promoted to the part of Miss Andrew, will perform as part of a 23-show run at the Orpheum Theater in Omaha, where loads of family and friends will be sure to cheer her on. This isn’t the first time she’s made a splash: she’s made waves off-Broadway (Fame) and on Broadway (Les Miserables) and in many regional theater productions. But this time she’s come home as part of a Broadway show. Sweet.

Quiana is a daughter of my good acquaintances Rudy and Llana Smith. She’s inherited their talent and drive and gone them one further by pursuing and realizing her dream of a musical theater career in New York. This profile of Quiana for The Reader (www.thereader.com) expresses this dynamic young woman’s heart and passion. It’s been a few years since I’ve spoken with her, and I’m eager to find out what she’s been up to lately, and how she and her father are coming along on a book project about African-American stage divas. Quiana is to write it and Rudy, a professional photographer, is to shoot it. Her mother, Llana, is a theater person, too — writing and directing gospel plays. My story on Llana Smith is posted on this site and I will soon be adding a story I did on Rudy Smith. They are a remarkable family.

Quiana Smith’s dream time takes her to regional, off-Broadway and Great White Way theater success

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Once the dream took hold, Quiana Smith never let go. Coming up on Omaha’s north side she discovered a flair for dramatics and a talent for singing she hoped would lead to a musical theater career. On Broadway. After a steady climb up the ladder her dream comes true tomorrow when a revival of Les Miserables open at the Broadhurst Theatre in New York. Q. Smith, as her stage name reads, is listed right there in the program, as a swing covering five parts, a testament to her versatility.

Before Les Miz is over Smith will no doubt get a chance to display her big, bold, brassy, bodacious self, complete with her shaved head, soaring voice, infectious laugh and broad smile. Her Broadway debut follows featured roles in the off-Broadway Fame On 42nd Street at NY‘s Little Shubert Theater in 2004 and Abyssinia at the North Shore Theater (Connecticut) in 2005. Those shows followed years on the road touring with musical theater companies or doing regional theater.

Fame’s story about young performers’ big dreams resonated for Smith and her own Broadway-bound aspirations. As Mabel, an oversized dancer seeking name-in-lights glory, she inhabited a part close to her ample self, projecting a passion akin to her own bright spirit and radiating a faith not unlike her deep spirituality. In an Act II scene she belted out a gospel-inspired tune, Mabel’s Prayer, that highlighted her multi-octave voice, impassioned vibrato and sweet, sassy, soulful personality. In the throes of a sacred song like this, Smith retreats to a place inside herself she calls “my secret little box,” where she sings only “to God and to myself. It’s very, very personal.” Whether or not she gets on stage this weekend in Les Miz you can be sure the 28-year-old will be offering praise and thanksgiving to her higher power.

It all began for her at Salem Baptist Church, where her grandmother and mother, have written and directed gospel plays for the dramatic ministry program. At her mother Llana’s urging, Smith and her brothers sang and acted as children. “My brothers got really tired of it, but I loved the attention, so I stuck with it,” said Smith, who began making a name for herself singing gospel hymns, performing skits and reciting poetry at Salem and other venues. She got attention at home, too, where she’d crack open the bathroom window and wail away so loud and finethat neighborhood kids would gather outside and proclaim, “You sure can sing, Quiana” “We were just a real creative house,” said Quiana’s mother.

Quiana further honed her craft in classes at the then-Emmy Gifford Children’s Theatre and, later, at North High School, where music/drama teacher Patrick Ribar recalls the impression Smith made on her. “The first thing I noticed about Quiana was her spark and flair for the stage. She was so creative…so diverse. She would do little things to make a part her own. I was amazed. She could hold an audience right away. She has such a warmth and she’s so fun that it’s hard not to like her.”

Still, performing was more a recreational activity than anything else. “Back then, I never knew I wanted to do this as a career,” Smith said. “I just liked doing it and I liked the great response I seemed to get from the audience. But as far as a career, I thought I was going to be an archaeologist.”

She was 15, and a junior at North, when her first brush with stardom came at the old Center Stage Theatre. She saw an audition notice and showed up, only to find no part for a black girl. She auditioned anyway, impressing executive directorLinda Runice enough to be invited back to tryout for a production of Dreamgirls. The pony-tailed hopeful arrived, in jeans and sweatshirt, sans any prepared music, yet director Michael Runice (Linda’s husband) cast her as an ensemble member.

Then, in classic a-star-is-born fashion, the leading lady phoned-in just before rehearsal the night before opening night to say she was bowing out due to a death-in-the-family. That’s when Mike Runice followed his instinct and plucked Smith from the obscurity of the chorus into a lead role she had less than 24 hours to master.

“It was like in a movie,” Smith said. “The director turned around and said to me, ‘It’s up to you, kid.’ I don’t know why he gave it to me to this day. You should have seen the cast. It was full of talented women. I was the youngest.” And greenest. Linda Runice said Smith got it because “she was so talented. She had been strongly considered for the role anyway, but she was so young and it’s such a demanding role. But she was one of those rare packages who could do it all. You saw the potential when she hit the stage, and she just blew them out of the theater.”

What began as a lark and segued into a misadventure, turned into a pressure-packed, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Not only did an already excited and scared Smith have precious little time to steel herself for the rigorous part and for the burden of carrying a show on her young shoulders, there was still school to think about, including finals, not to mention her turning sweet 16.

“The director wrote me a note to let me out of school early and he came to pick me up and take me to the theater. From 12 to 8, I was getting fitted for all the costumes, I was learning all the choreography, I was going over all the line readings, I was singing all the songs, and it was just crazy. A crash course.”

Smith pushed so hard, so fast to nail the demanding music in time for the show that she, just as the Runices feared, strained her untrained voice, forcing her to speak many of the songs on stage. That opening night is one she both savors and abhors. “That was the best and the worst thing that ever happened to me,” she said. “It was the best thing because if it wasn’t for that experience I’d probably be digging up fossils somewhere, which isn’t bad, but I wouldn’t be fulfilled. And it was the worst because I was so embarrassed.”

In true trouper tradition, Smith and the show went on. “What a responsiblity she carried for someone so young, and she carried it off with all the dignity and aplomb anyone could ever want,” Linda Runice said. Smith even kept the role the entire run. The confidence she gained via this baptism-by-fire fueled her ambition. “I told myself, If I can do this, I can do anything,” Smith said. Runice remembers her “as this bubbly, fresh teenager who was going to set the world on fire, and she has.”

To make her Broadway debut in Les Miz is poetic justice, as that show first inspired Smith’s stage aspirations. She heard songs from it in a North High music class and was really bit after seeing a Broadway touring production of it at the Orpheum.

“It was my introduction to musical theater. I fell in love with it,” she said. “I already had a double cassette of the cast album and I would listen to this song called ‘I Dreamed a Dream’ over and over. It was sung by Patti Lapone. I tried to teach myself to sing like that. When I finally met her last year I told her the story. That song is still in my audition book.”

Smith dreamed of doing Lez Miz in New York. Ribar recalls her telling him soon after they met, “‘One day I’m going to be on Broadway…’ She was bound and determined. Nothing was going to stop her. So, she goes there, and the next thing you know…she’s on Broadway. With her determination and talent, you just knew she was right on the edge of really brilliant things in her life. I brag about her to the kids as someone who’s pursued her dream,” he said. Stardom, he’s sure, isn’t far off. “Once the right role shows up, it’s a done deal.”

A scholarship led her to UNO, where she studied drama two years. All the while, she applied to prestigious theater arts programs back east to be closer to New York. Her plans nearly took a major detour when, after an audition in Chicago, she was accepted, on the spot, by the Mountview Conservatory in London to study opera. Possessing a fine mezzo soprano voice, her rendition of an Italian aria knocked school officials out. She visited the staid old institution, fell in love with London, but ultimately decided against it. “The opera world, to me, isn’t as exciting and as free as the musical theater world is,” she said. “Besides, it was a two or three-year conservatory program, and I really wanted the whole college experience to make me a whole person.”

|

©photo by David Wells

Her musical theater track resumed with a scholarship to Ithaca (NY) College, where she and a classmate became the first black female grads of the school’s small theater arts program. She also took private voice and speech training. At Ithaca, she ran into racial stereotyping. “When I first got there everybody expected you to sing gospel or things from black musicals,” she said. “Everything was black or white. And I was like, It doesn’t have to be like that. I can do more than gospel. I can do more than R&B. I can do legit. I really had to work hard to prove myself.”

Her experience inspired an idea for a book she and her father, Omaha World-Herald photographer Rudy Smith, are collaborating on. She interviews black female musical theater actresses to reveal how these women overturn biases, break down barriers and open doors. “We’re rare,” she said of this sisterhood. “These women are an inspiration to me. They don’t take anything from anybody. They’re divas, honey. Back in the day, you would take any part that came to you because it was a job, but this is a new age and we are allowed to say, No. In college, I would have loved to have been able to read about what contemporary black females are doing in musical theater.” Her father photographs the profile subjects.

She’s had few doubts about performing being her destiny. One time her certainty did falter was when she kept applying for and getting rejected by college theater arts programs. She sought her dad’s counsel. “I said, ‘Dad…how do I know this is for me?’ He was like, ‘Sweetheart, it’s what you breath, right?’ It’s what you go to bed and wake up in the morning thinking about, right?’ I was like, ‘Yeah…’ ‘OK, then, that’s what you should be doing.’ And, so, I never gave up. I kept on auditioning and I finally got accepted to Ithaca.”

Smith has worked steadily since moving to the Big Apple. Her credits include speaking-singing parts in productions of Hair at the Zachary Scott Theatre and The Who’s Tommy at the Greenwich St. Theatre and performing gigs in five touring road shows. Those road trips taught her a lot about her profession and about herself. On a months-long winter tour through Germany with the Black Gospel Singers, which often found her and her robed choir mates performing in magnificent but unheated cathedrals, she got in touch with her musical-cultural heritage. “Gospel is my roots and being part of the gospel singers just brought my roots back,” she said.

New York is clearly where Smith belongs. “I just feel like I’ve always known New York. I always dreamed about it. It was so easy and comfortable when I first came here,” she said. “Walking the streets alone at 1 a.m., I felt at home, like it was meant to be. It’s in my blood or something.”

Until Fame and now Les Miz, New York was where she lived between tours. Her first of two cross-country stints in Smokey Joe’s Cafe proved personally and professionally rewarding. She understudied roles that called for her to play up in age, not a stretch for “an old soul” like Smith. She also learned lessons from the show’s star, Gladys Knight. “She was definitely someone who gave it 100 percent every night, no matter if she was hoarse or sick, and she demanded that from us as well,” Smith said, “and I appreciated that. The nights I didn’t go on, I would go out into the audience and watch her numbers and she just blew the house down every single night. And I was like, I want to be just like that. I learned…about perseverance and about dedication to the gift God has given you.”

For a second Smokey stint, starring Rita Coolidge, Q. was a regular cast member. Then, she twice ventured to Central America with the revues Music of Andrew Lloyd Weber andBlues in the Night. “That’s an experience I’ll never forget,” she said. “We went to a lot of poor areas in Guatemala and El Salvador. People walk around barefoot. Cows are in the road. Guns are all around. We performed in ruins from the civil wars. And there we were, singing our hearts out for people who are hungry, and they just loved it. It was a life-changing experience.”

She loves travel but loves performing more in New York, where she thinks she’s on the cusp of something big. “It’s a dream come true and I truly believe this is just the beginning,” said Smith, who believes a higher power is at work. “I know it’s not me that’s doing all this stuff and opening all these doors so quickly, because it’s taken some people years and years to get to this point. It’s nothing but the Lord. I have so much faith. That’s what keeps me in New York pursuing this dream.”

Connecting with long time friend Jia Taylor

While not a headliner with her name emblazoned on marquees just yet, she’s sure she has what it takes to be a leading lady, something she feels is intrinsic in her, just waiting for the chance to bust on out. “I’m a leading lady now. I’m a leading lady every day. Yes, I say that with confidence, and not because I’m so talented,” she said. “It’s not about having a great voice. It’s not about being a star. It’s about how you carry yourself and connect with people. It’s about having a great aura and spirit and outlook on life… and I think I’ve got that”

Her busy career gives Smith few chances to get back home, where she said she enjoys “chilling with my family and eating all the good food,” but she makes a point of it when she can. She was back in September, doing a workshop for aspiring young performers at the Hope Center, an inner city non-profit close to her heart. She also sang for a cousin’s wedding at Salem. On some breaks, she finds time to perform here, as when featured in her mother’s Easter passion play at Salem in 2004. She’d like one day to start a school for performing arts on the north side, giving children of color a chance to follow their own dreams.

Occasionally, a regional theater commitment will bring her close to home, as when she appeared in a summer 2005 production of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coatin Wichita. Despite lean times between acting-singing gigs, when she works with aspiring youth performers for the Camp Broadway company, Smith keeps auditioning and hoping for the break that lands her a lead or featured part on Broadway, in film or on television. She’s not shy about putting herself out there, either. She went up for a role opposite Beyonce in the film adaptation of Dreamgirls, the other show she dreams of doing on Broadway. She can see it now. “Q. Smith starring in…” She wants it all, a Tony, an Oscar, an Emmy. A career acting, singing, writing, directing, teaching and yes, even performing opera.

Smith’s contracted for the six-month run of Les Miz. Should it be extended, she may face a choice: stay with it or join the national touring company of The Color Purple, which she may be in line for after nearly being cast in the Broadway show.

That said, Smith is pursuing film/TV work in L.A. after the positive experience of her first screen work, a co-starring role in the Black Entertainment Network’s BETJ mini-series, A Royal Birthday. The Kim Fields-directed project, also being packaged as a film, has aired recently on BET and its Jazz off-shoot. A kind of romantic comedy infomercial for Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines, the project also features Gary Dourdan from CSI and gospel artist David Hollister.

The Royal Birthday shoot, unfolding on two separate Caribbean cruises, whet her appetite for more screen work and revealed she has much to learn. “It was absolutely beautiful. We went horseback riding, para-sailing, jet-skiing. I had never done any of those things,” she said. “I learned a lot about acting for the camera, too. I’m very theatrical, very animated in it. It doesn’t need to be that big.”

Should fame allude her on screen or on stage, she’s fine with that, too, she said, because “I’m doing something I truly love.” Besides, she can always find solace in that “little secret box” inside her, where it’s just her and God listening to the power of her voice lifted on high. Sing in exaltation.

Blacks of Distinction

This set of profiles is from my large collection of Omaha African-American subjects. Read on and you will meet a gallery of compelling individuals who each made a difference in his or her own way. These figures represent a variety of endeavors and expertise, but what they all share in common is a passion for what they do. Along the way, they learned some hard lessons, and their individual and collective wisdom should give us all food for thought. These stories originally appeared in the New Horizons.

Blacks of Distinction

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Frank Peak, Still An Activist After All These Years

Addressing the needs of underserved people became a lifetime vocation for Frank Peak only after he joined the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s.

Today, as administrator of community outreach service for the Creighton University Medical Center Partnership in Health and co-administrator of the Omaha Urban Area Health Education Center, he carries on the mission of the Panthers to help empower African-Americans.

The Omaha native returned home after a six-year (1962-1968) hitch in the U.S. Navy as a photographer’s mate 2nd class, duty that saw him hop from ship to ship in the South China Sea and from one hot zone to another in Vietnam, variously photographing or processing images of military life and wartime action.

The North High grad came back with marketable skills but couldn’t get a job in the media here. He went into the service in the first place, he said, to escape the limited horizons that blacks like himself and his peers faced at home.

“There weren’t a lot of opportunities for blacks in the city of Omaha.”

In the Navy he found what he believed to be a future career path when he was sent to photography school in Pensacola, Florida and excelled. It was a good fit, he said, as he’d always been a shutterbug. “I had always liked photography and I always took pictures with little Brownies and stuff.”

His duty entailed working as a military photojournalist and photo lab technician. Many of the pictures he took or processed were reproduced in civilian and military publications worldwide. In 1965 he prepared the production stills for an NBC television news documentary on the 25th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. He said the network even offered him a job, but he had to turn it down, as he’d already reenlisted. Despite that lost opportunity, he counts his Navy experience as one of the best periods of his life. Not only did he learn to become an expert photographer but he got to travel all over the Far East, much of the time with his younger brother, William, who followed him into the service.

The service is also where Peak became politicized as a strong, proud black man engaged in the struggle for equality.

“Back in the ‘60s there was such a lot of turmoil related to the war, related to the whole race struggle. You know, Malcolm, Martin…It all tied together. There were a lot of riots going on at a lot of the bases and on the ships. There was both bonding and animosity then between whites and blacks. It was a challenging time. ”

A buddy he was stationed with overseas helped Peak gain a deeper understanding of the black experience.

“I had a close friend, Bennie, who was a Navy photographer, too. He was from Savannah, Georgia and he really began to educate me. He was the one that really initiated me into the black experience. That’s when the term black was radical. Coming from Omaha, I was isolated from a lot of things he’d been involved in down South. Interestingly, I ended up a member of the Black Panther party and he ended up a member of the Black Muslims.”

After Peak got out of the Navy and came back to find doors still closed to him, despite the obvious skills he’d gained, he was disillusioned.

For example, he said the Omaha World-Herald wouldn’t even look at his portfolio when he applied there. For years, he said the local daily had only one black photographer on staff and made it clear they weren’t interested in hiring another.

Frustrated with the obstacles he and his fellow African-Americans faced, he was ripe for recruitment into the Black Panthers, a controversial organization that several of his activist friends joined. But he didn’t join right away. He was working as a photo technician when something happened that changed his mind. A black girl named Vivian Strong died from shots fired by a white Omaha police officer. The tragedy, which many in the black community saw as a racially motivated killing, touched off several nights of rioting on the north side.

“I got involved with the Black Panther party after that,” Peak said.

The Panther platform was an expression of the black power movement that sought, Peak said, “self-determination and liberation” for African-Americans. “It was about building capacity into the black community. It was working to end police violence in the black community. It was organizing breakfast programs for our children. Tutoring kids. Holding rallies, organizing protests and standing up for our rights.”

What made the Panthers dangerous in the minds of many authorities were the party’s incendiary language, paramilitary appearance — some members openly brandished firearms — and militant attitude.

“Our premise was we wanted our rights by any means necessary,” said Peak, a philosophy he feels was misconstrued by law enforcement as a subversive plot to undermine and overthrow the government. “What we meant by that was we wanted our education, we wanted to be a part of the political process, we wanted to be a part of determining our own destiny. We even asked, as part of our platform, to have a plebiscite, where blacks would vote to directly determine, for themselves, their own fate.”

Instead, the leadership of the Panthers and other radical black power groups were “crushed” and “dismantled” in a systematic crackdown led by the FBI. In Omaha, Peak was among those arrested and questioned when two local Panthers, Ed Poindexter and David Rice, were implicated and later convicted in the 1970 killing of Omaha police officer Larry Minard. The pair’s guilt or innocence has long been disputed. Appeals for new trials or new evidentiary hearings continue to this today. Peak was friends with both men and he believes they’re wrongfully imprisoned. “I don’t believe they got a fair trial,” he said. Ironically, it was his cousin, Duane Peak, who allegedly acted at the men’s behest in making the 911 call that lured Minard to the house where a suitcase bomb detonated. Doubt’s been cast on whether Duane Peak made the call or not and on the veracity of his court testimony.

Frank Peak traces “the roots” of his advocacy career to his time with the Panthers, when he helped set up “a liberation” school and breakfast program for kids. He said the Panther mission has been “very much diversified” in the work being done today by former party members in the political, social, health, education and human service fields. “The struggle goes on.”

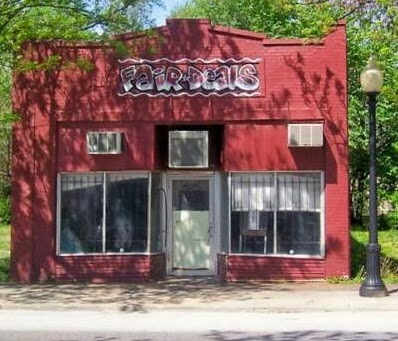

He and other young blacks here were inspired to affect change from within by mentors. “Theodore Johnson put together community health programs. Dr. Earl Persons got us involved in the black political caucus. Jessie Allen got us involved as delegates to the Democratic party. He really brought us around and politicized us to mainstream politics. Dan Goodwin and Ernie Chambers had a great influence on us, too. They made sure we were accountable. They had high standards for us.” There was also Omaha Star publisher Mildred Brown, reporter/activist Charlie Washington and others. Peak’s education continued at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he earned a bachelor’s in journalism and psychology and a master’s in public administration. Lively discussions about black aspirations unfolded at UNO, the Urban League, Panther headquarters, Charlie Hall’s Fair Deal Cafe and Dan Goodwin’s Spencer Street Barbershop.

Frank Peak

The spirit of those ideals lives on in his post-Panthers work, ranging from substance abuse counseling to community health advocacy to he and his wife, Lyris Crowdy Peak, an Omaha Head Start administrator, serving as adoptive and foster parents. He sees today’s drug and gang culture as a major threat. He rues that standards once seen as sacrosanct have “gone out the window” in this age of relativism.

“The only way change is going to occur is if people make it happen,” he said. “If you wait around for somebody else to make it happen, it might not…So, we all have a responsibility to make a contribution and I’m trying to make one.”

He enjoys being a liaison between Creighton and the community in support of health initiatives, screenings and services aimed at minorities. “We just finished glaucoma screenings in south Omaha and we put together the first African-American prostate cancer campaign in north Omaha. We sponsor programs like My Sister’s Keeper, a breast cancer survivors program focused on African-American women.” He said in addition to assessment and treatment, Creighton also provides follow-up services and referrals for those lacking the access, the means, the insurance or the primary care provider to have their health care needs met.

“I’m somebody who believes in what he does. People ask me, Do you like your job? I say, Well, if you get paid for doing something you’d do for free, how could you not like it? That’s my philosophy. To think maybe in some small way you’ve been a part of growing a greater society, then that’s all the reward I need.”

Charles Hall’s Fair Deal

As landmarks go, the Fair Deal Cafe doesn’t look like much. The drab exterior is distressed by age and weather. Inside, it is a plain throwback to classic diners with its formica-topped tables, tile floor, glass-encased dessert counter and tin-stamped ceiling. Like the decor, the prices seem left over from another era, with most meals costing well under $6. What it lacks in ambience, it makes up for in the quality of its food, which has been praised in newspapers from Denver to Chicago.

Owner and chef Charles Hall has made The Fair Deal the main course in Omaha for authentic soul food since the early 1950s, dishing-up delicious down home fare with a liberal dose of Southern seasoning and Midwest hospitality. Known near and far, the Fair Deal has seen some high old times in its day.

Located at 2118 No. 24th Street, the cafe is where Hall met his second wife, Audentria (Dennie), his partner at home and in business for 40 years. She died in 1997. The couple shared kitchen duties (“She bringing up breakfast and me bringing up dinner,” is how Hall puts it.) until she fell ill in 1996. These days, without his beloved wife around “looking over my shoulder and telling me what to do,” the place seems awfully empty to Hall. “It’s nothing like it used to be,” he said. In its prime, it was open dawn to midnight six days a week, and celebrities (from Bill Cosby to Ella Fitzgerald to Jesse Jackson) often passed through. When still open Sundays, it was THE meeting place for the after-church crowd. Today, it is only open for lunch and breakfast.

The place, virtually unchanged since it opened sometime in the 1940s (nobody is exactly sure when), is one of those hole-in-the-wall joints steeped in history and character. During the Civil Rights struggle it was commonly referred to as “the black city hall” for the melting pot of activists, politicos and dignitaries gathered there to hash-out issues over steaming plates of food. While not quite the bustling crossroads or nerve center it once was, a faithful crowd of blue and white collar diners still enjoy good eats and robust conversation there.

|

Fair Deal Cafe

Running the place is more of “a chore” now for Hall, whose step-grandson Troy helps out. After years of talking about selling the place, Hall is finally preparing to turn it over to new blood, although he expects to stay on awhile to break-in the new, as of now unannounced, owners. “I’m so happy,” he said. “I’ve been trying so hard and so long to sell it. I’m going to help the new owners ease into it as much as I can and teach them what I have been doing, because I want them to make it.” What will Hall do with all his new spare time? “I don’t know, but I look forward to sitting on my butt for a few months.” After years of rising at 4:30 a.m. to get a head-start on preparing grits, rice and potatoes for the cafe’s popular breakfast offerings, he can finally sleep past dawn.

The 80-year-old Hall is justifiably proud of the legacy he will leave behind. The secret to his and the cafe’s success, he said, is really no secret at all — just “hard work.” No short-cuts are taken in preparing its genuine comfort food, whose made-from-scratch favorites include greens, beans, black-eyed peas, corn bread, chops, chitlins, sirloin tips, ham-hocks, pig’s feet, ox tails and candied sweet potatoes.

In the cafe’s halcyon days, Charles and Dennie did it all together, with nary a cross word uttered between them. What was their magic? “I can’t put my finger on it except to say it was very evident we were in love,” he said. “We worked together over 40 years and we never argued. We were partners and friends and mates and lovers.” There was a time when the cafe was one of countless black-owned businesses in the district. “North 24th Street had every type of business anybody would need. Every block was jammed,” Hall recalls. After the civil unrest of the late ‘60s, many entrepreneurs pulled up stakes. But the Halls remained. “I had a going business, and just to close the doors and watch it crumble to dust didn’t seem like a reasonable idea. My wife and I managed to eke out a living. We never did get rich, but we stayed and fought the battle.” They also gave back to the community, hiring many young people as wait staff and lending money for their college studies.

Besides his service in the U.S. Army during World War II, when he was an officer in the Medical Administrative Corps assigned to China, India, Burma, Japan and the Philippines, Hall has remained a home body. Born in Horatio, Arkansas in 1920, he moved with his family to Omaha at age 4 and grew up just blocks from the cafe. “Almost all my life I have lived within a four or mile radius of this area. I didn’t plan it that way. But, in retrospect, it just felt right. It’s home,” he said. After working as a butcher, he got a job at the cafe, little knowing the owners would move away six months later to leave him with the place to run. He fell in love with both Dennie and the joint, and the rest is history. “I guess it was meant to be.”

Deadeye Marcus Mac McGee

When Marcus “Mac” McGee of Omaha thinks about what it means to have lived 100 years, he ponders a good long while. After all, considering a lifespan covering the entire 20th century means contemplating a whole lot of history, and that takes some doing. It is an especially daunting task for McGee, who, in his prime, buried three wives, raised five daughters, prospered as the owner of his own barbershop, served as the state’s first black barbershop inspector, earned people’s trust as a pillar of the north Omaha community and commanded respect as an expert marksman. Yes, it has been quite a journey so far for this descendant of African-American slaves and white slave owners.

A recent visitor to McGee’s room at the Maple Crest Care Center in Benson remarked how 100 years is a long time. “It sure is,” McGee said in his sweet-as-molasses voice, his small bright face beaming at the thought of all the high times he has seen. In a life full of rich happenings, McGee’s memories return again and again to the first and last of his loves — shooting and barbering. For decades, he avidly hunted small game and shot trap. In his late 80s he could still hit 100 out of 100 targets on the range. Yes, there was a time when McGee could shoot with anyone. He won more than his share of prizes at area trapshooting meets — from hams and turkeys to trophies to cold hard cash. As his reputation began to spread, he found fewer and fewer challengers willing to take him on. “I would break that target so easy. I’d tear it up every time. I’d whip them fellas down to the bricks. They wouldn’t tackle me. Oh, man, I was tough,” he said.

As owner and operator of the now defunct Tuxedo Barbershop on North 24th Street, he ran an Old School establishment where no fancy hair styles were welcome. Just a neat, clean cut from sparkling clippers and a smooth, close shave from well-honed straight-edge razors. “The best times for me was when I got that shop there. I got the business going really good. It was quite a shop. We had three chairs in there. New linoleum on the floor. There were two other barbers with me. We had a lot of customers. Sometimes we’d have 10-15 people outside the door waiting for us to come in. I enjoyed that. I enjoyed working on them — and I worked on them too. I’d give them good haircuts. I was quite a barber. Yes, sir, we used to lay some hair on the floor.”

McGee’s Tuxedo Barbershop was located in the Jewell Building

A fussy sort who has always taken great pains with his appearance, he made his own hunting vests, fashioned his own shells and watched what he ate. “I was particular about a lot of things,” he said. Unlike many Maple-Crest residents, who are disabled and disheveled, McGee walks on his own two feet and remains well-groomed and nattily-attired at all times. He entrusts his own smartly-trimmed hair to a barbering protege. Last September, McGee cut a dashing figure for a 100th birthday party held in his honor at Clair Memorial United Methodist Church. A crowd of family and friends, including dozens of grandchildren and great-grandchildren, gathered to pay tribute to this man of small stature but big deeds. Too bad he could not share it all with his wife of 53 years, LaVerne, who died in 1996.

Born and raised along the Mississippi-Louisiana border, McGee’s family of ten escaped the worst of Jim Crow intolerance as landowners under the auspices of his white grandmother Kizzie McGee, the daughter of the former plantation’s owner. McGee’s people hacked out a largely self-sufficient life down on the delta. It was there he learned to shoot and to cut hair. He left school early to help provide for the family’s needs, variously bagging wild game for the dinner table and cutting people’s hair for spare change. Just out of his teens, he followed the path of many Southern blacks and ventured north, where conditions were more hospitable and jobs more plentiful. During his wanderings he picked up money cutting heads of railroad gang crewmen and field laborers he encountered out on the open road.

He made his way to Omaha in the early 1920s, finding work in an Omaha packing plant before opening his Tuxedo shop in the historic Jewel Building. People often came to him for advice and loans. He ran the shop some 50 years before closing it in the late 1970s. He wasn’t done cutting heads though. He barbered another decade at the shop of a man he once employed before injuries suffered in an auto accident finally forced him to put down his clippers at age 88. “I loved to work. I don’t know why people retire.” As much as he regrets not working anymore, he pines even more for the chance to shoot again. “I miss everything about shooting.” He said he even dreams about being back on the hunt or on the range. Naturally, he never misses. “I always take the target. Yeah, man, I was one tough shooter.”

Proud, Poised Mary Dean Pearson

A life of distinction does not happen overnight. In the case of Omaha executive, educator, child advocate, community leader, wife and mother Mary Dean Pearson, the road to success began just outside Marion, La., where she grew up as one of nine brothers and sisters in a fiercely independent black family during the post World War II era — a period when the South was still segregated. From as far back as she can remember, Pearson (then Hunt) knew exactly what was expected of her and her siblings– great things. “I grew up in the South during the Crow era and my father instilled in all of his children a very profound sense of obligation to improve on what we were born into. To make it better. Whether that was our immediate economic circumstances or social status or whatever,” she said.

Despite the fact her parents, Ed and Rosa Hunt, never got very far in school they were high achievers. He was a respected landowner and entrepreneur and, together with Rosa, set rigorously high standards for their children. Even the daughters were expected to do chores, to complete high school and, unusual for the time, to attend college. “My father was a very driven, very aggressive man who believed it was our right and our duty to do well everyday. And to do only well. The consequences were quite severe if you didn’t do well. He also instilled a work ethic, which is probably unparalleled, in all of us,” said Pearson, a former Omaha Public Schools teacher and past director of the Nebraska Department of Social Services who, since 1995, has been president and CEO of the Boys and Girls Clubs of Omaha, Inc.

“I was his workhorse from time to time. I call him the father of women’s lib because he never hesitated to say, ‘Baby, do this,’ even if it was a heavy job traditionally reserved for men. I really credit him with helping me understand that anything that needed to be done, I perhaps had the capability of doing it, and so I just approached everything with that can-do sensibility. I got that from him, no doubt.”

Where her father cracked the whip, her mother applied the salve. “My mother was a gentle soul who was the one always to seek peace and to seek a solution. I think my attempt to become a peacemaker and facilitator was my desire to be more like her. She created an absolutely wonderful balance for our family. They were a dynamite team.” For Pearson, the lessons her parents taught her are bedrock values that never go out of style: “Honesty, integrity, loyalty, perseverance.”

Pearson and her siblings did not let their parents down, either. They became professionals and small business owners. She graduated with a liberal arts degree from Grambling State University, hoping for a career in law. Her plans were put on hold, however, after marrying her old beau Tom Harvey, who got a teaching contract in Omaha, where the young couple moved in the late 1960s. She tried finding work here to earn enough money for law school but found doors closed to her because of her color. Then, she joined the National Teacher Corps, a federal teaching training program pairing liberal arts majors with students in inner city schools. She soon found she could make a difference in young lives and abandoned law for education. “I discovered there were some young folks in this world who were absolutely starving for intellectual challenge, and I enjoyed providing that to them.”

As part of the program she earned a master’s degree in education at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where former College of Education dean Paul Kennedy became the strong new mentor figure in her life. “If I ever thought I was going to slack off once I had left my father, I was wrong. Paul Kennedy saw my soul and demanded the very best from me.” After earning her teaching degree at UNO, she embarked on a 20-year education career that included serving as an OPS classroom teacher, assistant principal and principal. She treasures her experiences as an educator and holds the role of educator in the highest esteem.

“As a classroom teacher you can actually see you have touched someone. The satisfaction is immediate. As an administrator, the obligation is to give every child, every learner, the maximum opportunity for success. It is to say, ‘All children can learn.’” She is “proudest” of how successful some of her former students are. “They are carrying on the lessons they were taught to make our society a better one as teachers, lawyers, doctors, ministers.”

By 1986 Pearson was ready for some new challenges. Starting with her term as executive director of Girls Incorporated through her stewardship of the state’s social services agency (at then Gov. Ben Nelson’s request) and up to her current post as head of the Boys and Girls Clubs, she has focused on programs for disadvantaged youths that “improve their life chances.” While Pearson can one day see herself exploring new challenges outside the social service arena, she would miss impacting children. “Of all the groups present in our society, children are the one one group who need an advocate more than any other.”

Mildred Lee , Standing Her Ground