Archive

New plays are discovered at Omaha’s own Great Plains Theatre Conference

New plays are discovered at Omaha’s own Great Plains Theatre Conference

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the June 2018 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

The Great Plains Theatre Conference is more than a collaborative around craft. It’s also a source of plays for theaters, whose productions give GPTC playwrights a platform for their words to take shape.

The May 27-June 2 2018 GPTC included a Blue Barn Theatre mounting of Matthew Capodicasa’s In the City, In the City, In the City. Artistic director Susan C. Toberer booked it after a 2017 PlayLab reading. The piece opened a regular run May 17, Then came a PlayFest performance. The show continues through June 17 to cap Blue Barn’s 29th season.

Toberer said the conference is “a good source” for new material, adding, “I wouldn’t have been aware of City if not for GPTC and it became perhaps the show we most looked forward to this season.”

Susan C. Toberer, ©photo by Debra S. Kaplan

Staging new works from the conference expands the relationship between theaters and playwrights.

“The incredible openness of the process is one of the many joys of working with a script and a playwright with such generosity of spirit. Not only were we able to bring Matthew into the process early and often to offer guidance and support,” she said, “but he invited the artists involved to imagine almost infinite possibilities. We are thrilled to bring his play to life for the first time.”

GPTC producing artistic director Kevin Lawler couldn’t be more pleased.

“This is part of my dream. It’s not really a dream anymore, it’s reality, that local theaters can garner and grab productions, including premiere productions of plays from the scripts that come here to Great Plains. City is a great example of that,” he said.

“Another example is UNO now designating the third slot in their season to fully produce a Great Plains Theatre Conference PlayLab from the previous year.”

“The GPTC-UNO connection goes way back,” said University of Nebraska at Omaha theater professor Cindy Phaneuf. She’s developed alliances with conference guests, even bringing some back to produce their work or to give workshops.

Since conference founder and former Metropolitan Community College president Jo Ann McDowell shared her vision with community and academia theater professionals in 2006, It’s been a cooperative venture, Theater pros serve as directors, stage managers, actors, dramaturges and respondents. Students attend free and fill various roles onstage and off.

The Young Dramatists Fellowship Program is a guided experiential ed immersion for high school students during the conference. It affords opportunities to interact with theater pros.

“The participation of our local theater artists and students is a key sustaining factor of the conference,” Lawler said. “Our national and international guest artists are won over by the talent, generosity and insight of our local theater community and that helps the conference rise to a higher level of engagement and creativity.”

Besides honing craft at the MCC-based conference, programming extends to mainstage and PlayFest works produced around town. Then there are those GPTC plays local theaters incorporate into their seasons.

“We’ve always done plays touched by Great Plains.” Phaneuf said. “Now it’s taking another step up where we’re committing sight unseen to do one of the plays selected for play reading in our season next year. That happens to be a season of all women, so we’re reading the plays by women to decide what fits into our season.”

It will happen as part of UNO’s new Connections series.

“The idea is that UNO will connect with another organization to do work that matters to both of us. This coming year that connection is with the Great Plains.”

Phaneuf added, “We’re also doing The Wolves by Sarah DeLappe. It also started at Great Plains and has gotten wonderful national exposure.”

Additional GPTC works account for some graduate student studio productions in the spring.

This fall Creighton University is producing the world premiere of Handled by CU alum Shayne Kennedy, who’s had previous works read at GPTC.

Elizabeth Thompson, ©photo by Debra S. Kaplan

The Shelterbelt’ Theater has produced a dozen GPTC-sourced plays since 2006, including three since 2014: Mickey and Sage by Sara Farrington, The Singularity by Crystal Jackson and The Feast by Celine Song. It will present another in 2018-2019.

As artistic director since 2014, Elizabeth Thompson said she’s nurtured “a stronger bond with Great Plains, especially since GPTC associate artistic director Scott Working is one of our founders – it’s a no-brainer.”

Omaha playwright Ellen Struve has seen several of her works find productions, including three at Shelterbelt, thanks to Great Plains exposure and networking.

“Some of the greatest advocates of my work have been other writers at GPTC. I’ve helped get GPTC writers productions and they’ve helped me get productions. We are always fighting on behalf of each other’s work,” Struve said. “My first play Mrs Jennings’ Sitter was selected as a mainstage reading in 2008. (Director) Marshall Mason asked me to send the play to companies he worked with on the east coast. Frequent GPTC playwright Kenley Smith helped secure a production in his home theater in West Virginia.

“When my play Mountain Lion was selected (in 2009), Shelterbelt offered to produce the plays together in a summer festival. Then in 2010, (playwright) Kari Mote remembered Mrs. Jennings’ Sitter and asked if she could produce it in New York City.”

In 2011, Struve’s Recommended Reading for Girls was championed to go to the Omaha Community Playhouse, where Amy Lane directed it.

“This kind of peer promotion-support happens every year at Great Plains,” Struve said. “It has been a transformative partner for me.”

Kevin Lawler confirms “a strong history” of “artists supporting each other’s work well beyond the conference.”

Plays come to theaters’ attention in various ways.

“A lot of directors will send me the piece they’re working on at Great Plains and say, ‘I see this at the Shelterbelt and I would love to stay involved if possible.’ That’s definitely something we look at,” Thompson said. “The writer already has a relationship with them and that can make the process a little easier.

“Actors involved in a reading of a script we produce often want to come audition for it. They’re excited about seeing something they were involved with in a small way get fully realized.”

Capodicasa’s City was brought to Blue Barn by actress Kim Gambino, who was in its GPTC reading. She studied theater in New York with Toberer.

Capodicasa is glad “the script made its way to the folks at Blue Barn,” adding, “I’m so honored the Blue Barn is doing the play.” He’s enjoyed collaborating with the team for his play’s first full production and is happy “to “share it with the Omaha community.”

“When I served on the Shelterbelt’s reading committee, I was charged with helping find scripts that could possibly fill a gap in the season,” said playwright-director Noah Diaz. “I remembered The Feast – its humor and beauty and terror – and suggested it. Frankly, I didn’t think it would win anyone over. To my surprise, Beth Thompson decided to program it — something I still consider to be deeply courageous. An even bigger surprise came when Beth suggested I direct it.

“The GPTC is providing an opportunity for the community at large to develop relationships with new plays from the ground up. My hope is by having direct connection to these writers, Omaha-based companies will begin shepherding new works onto their stages.”

“Because we’re a theater that only produces new work,” Thompson said, “these plays have a much better chance of being produced with us than they do with anyone else in Omaha.”

Doing new work is risky business since its unfamiliar to audiences, but Thompson said an advantage to GPTC scripts is that some Shelterbelt patrons “already know about them a little bit because they’re developed with Omaha actors and directors – that helps.”

Twenty plays are selected for GPTC from a blind draw of 1,000 submissions. Thus, local theaters have a rich list of finely curated works to draw from.

“These playwrights are going places,” UNO’s Phaneuf said. “You can be in the room with some of the best playwrights in the country and beyond and you can get to know those writers and their work. It’s wonderful to see them when they’re just ready to be discovered by a lot of people and to feel a part of what they’re doing.”

Whether plays are scouted by GPTC insiders or submitted by playwrights themselves, it means more quality options.

“It just opens up our gate as to what we consider local, and while we have amazing writers that are local, they’re not writing all the time, so it gives us a bigger pool to pick from,” Thompson said.

When theaters elect to produce the work of GPTC playwrights, a collaboration ensues. “They’re definitely involved,” Thompson said. The GPTC playwrights she’s produced at Shelterbelt all reside outside Nebraska.

“Their input is just as valuable as if they were living here and able to come to every rehearsal. We Face-time, Skype, text, email because they do have the opportunity to make some changes throughout the process.”

For Lawler, it’s about growing the theater culture.

“I love that our local theaters are being able to take different scripts from the conference and throw them into their seasons – many times giving a premiere for the play. A lot of productions and relationships are born at the conference.”

Ellen Struve has been a beneficiary of both.

“GPTC has given me access to some of the greatest playwrights alive. It’s a community. Local, national and international. It has invigorated the Omaha writing scene. Every year we get to see what’s possible and imagine what we’ll do next.”

Visit http://www.gptcplays.com.

Read more of Leo Adam Biga’s work at https://leoadambiga.com.

South Omaha stories on tap for free PlayFest show; Great Plains Theatre Conference’s Neighborhood Tapestries returns to south side

Omaha’s various geographic segments feature distinct charecteristics all their own. South Omaha has a stockyards-packing plant heritage that lives on to this day and it continues its legacy as home to new arrivals, whether immigrants or refugees. The free May 27 Great Plains Theatre Conference PlayFest show South Omaha Stories at the Livestock Exchange Building is a collaboration between playwrights and residents that shares stories reflective of that district and the people who comprise it. What follows are two articles I did about the event. The first and most recent article is for The Reader (www.thereader.com) and it looks at South O through the prism of two young people interviewed by playwrights for the project. The second article looks at South O through the lens of three older people interviewed by playwrights for the same project. Together, my articles and participants’ stores provide a fair approximation of what makes South O, well, South O. Or in the vernacular (think South Side Chicago), Sou’d O.

South Omaha stories on tap for free PlayFest show

Great Plains Theatre Conference’s Neighborhood Tapestries returns to south side

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appearing in the May 2015 issue of The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Perhaps more than any geographic quadrant of the city, South Omaha owns the richest legacy as a livestock-meatpacking industry hub and historic home to new arrivals fixated on the American Dream.

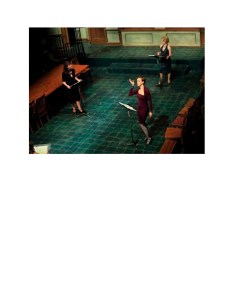

Everyone with South O ties has a story. When some playwrights sat down to interview four such folks, tales flowed. Using the subjects’ own words and drawing from research, the playwrights, together with New York director Josh Hecht, have crafted a night of theater for this year’s Great Plains Theatre Conference’s Neighborhood Tapestries.

Omaha’s M. Michele Phillips directs this collaborative patchwork of South Omaha Stories. The 7:30 p.m. show May 27 at the Livestock Exchange Building ballroom is part of GPTC’s free PlayFest slate celebrating different facets of Neb. history and culture. In the case of South O, each generation has distinct experiences but recurring themes of diversity and aspiration appear across eras.

Lucy Aguilar and Batula Hilowle are part of recent migration waves to bring immigrants and refugees here. Aguilar came as a child from Mexico with her undocumented mother and siblings in pursuit of a better life. Hilowle and her siblings were born and raised in a Kenya refugee camp. They relocated here with their Somali mother via humanitarian sponsors. In America, Batula and her family enjoy new found safety and stability.

Aguilar, 20, is a South High graduate attending the University of Nebraska at Omaha. GPTC associate artistic director and veteran Omaha playwright Scott Working interviewed her. Hilowle, 19, is a senior at South weighing her college options. Harlem playwright Kia Corthron interviewed her.

A Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) work permit recipient, Aguilar is tired of living with a conditional status hanging over head. She feels she and fellow Dreamers should be treated as full citizens. State law has made it illegal for Dreamers to obtain drivers licenses.

“I’m here just like everybody else trying to make something out of my life, trying to accomplish goals, in my case trying to open a business,” and be successful in that,” Aguilar says.

She’s active in Young Nebraskans for Action that advocates restrictions be lifted for Dreamers. She follows her heart in social justice matters.

“Community service is something I’m really passionate about.”

She embraces South O as a landing spot for many peoples.

“There’s so much diversity and nobody has a problem with it.”

Hilowle appreciates the diversity, too.

“You see Africans like me, you see African Americans,, Asians, Latinos, whites all together. It’s something you don’t see when you go west.”

Both young women find it a friendly environment.

“It’s a very open, helpful community,” Aguilar says. “There are so many organizations that advocate to help people. If I’m having difficulties at home or school or work, I know I’ll have backup. I like that.”

“It’s definitely warm and welcoming,” Hilowle says. “It feels like we’re family. There’s no room for hate.”

Hilowle says playwright Kia Corthon was particularly curious about the transition from living in a refuge camp to living in America.

“She wanted to know what was different and what was familiar. I can tell you there was plenty of differences.”

Hilowle has found most people receptive to her story of struggle in Africa and somewhat surprised by her gratitude for the experience.

“Rather than try to make fun of me I think they want to get to know me. I’m not ashamed to say I grew up in a refugee camp or that we didn’t have our own place. It made me better, it made me who I am today. Being in America won’t change who I am. My kids are going to be just like me because I am just like my mom.”

She says the same fierce determination that drove her mother to save the family from war in Somalia is in her.

About the vast differences between life there and here, she says, “Sometimes different isn’t so bad.” She welcomes opportunities “to share something about where I come from or about my religion (Muslim) and why I cover my body with so many clothes.”

Aguilar, a business major seeking to open a South O juice shop, likes that her and Hilowle’s stories will be featured in the same program.

“We have very different backgrounds but I’m pretty sure our future goals are the same. We’re very motivated about what we want to do.”

Similar to Lucy, Batula likes helping people. She’s planning a pre-med track in college.

The young women think it’s important their stories will be presented alongside those of much older residents with a longer perspective.

Virgil Armendariz, 68, who wrote his own story, can attest South O has long been a melting pot. He recalls as a youth the international flavors and aromas coming from homes of different ethnicities he delivered papers to and his learning to say “collect” in several languages.

“You could travel the world by walking down 36th street on Sunday afternoon. From Q Street to just past Harrison you could smell those dinners cooking. The Irish lived up around Q Street, Czechs, Poles, and Lithuanians were mixed along the way. Then Bohemians’ with a scattering of Mexicans.”

He remembers the stockyards and Big Four packing plants and all the ancillary businesses that dominated a square mile right in the heart of the community. The stink of animal refuse permeating the Magic City was called the Smell of Money. Rough trade bars and whorehouses served a sea of men. The sheer volume of livestock meant cows and pigs occasionally broke loose to cause havoc. He recalls unionized packers striking for better wages and safer conditions.

Joseph Ramirez, 89, worked at Armour and Co. 15 years. He became a local union leader there and that work led him into a human services career. New York playwright Michael Garces interviewed Ramirez.

Ramirez and Armendariz both faced discrimination. They dealt with bias by either confronting it or shrugging it off. Both men found pathways to better themselves – Ramirez as a company man and Armendariz as an entrepreneur.

While their parents came from Mexico, South Omaha Stories participant, Dorothy Patach, 91, traces her ancestry to the former Czechoslovakia region. Like her contemporaries of a certain age, she recalls South O as a once booming place, then declining with the closure of the Big Four plants, before its redevelopment and immigrant-led business revival the last few decades.

Patach says people of varied backgrounds generally found ways to co-exist though she acknowledges illegal aliens were not always welcome.

New York playwright Ruth Margraff interviewed her.

She and the men agree what united people was a shared desire to get ahead. How families and individuals went about it differed, but hard work was the common denominator.

Scott Working says the details in the South O stories are where universal truths lay.

“It is in the specifics we recognize ourselves, our parents, our grandparents,” he says, “and we see they have similar dreams that we share. It’s a great experience.”

He says the district’s tradition of diversity “has kept it such a vibrant place.” He suspects the show will be “a reaffirmation for the people that live there and maybe an introduction to people from West Omaha or North Omaha.” He adds, “My hope is it will make people curious about where they’re from, too. It’s kind of what theater does – it gives us a connection to humanity and tells us stories we find value in and maybe we learn something and feel something.”

The Livestock Exchange Building is at 4920 South 30th Street.

Next year’s Neighborhood Tapestries event returns to North Omaha.

For PlayFest and conference details, visit http://www.mccneb.edu/gptc.

South Omaha stories to be basis for new theater piece at Great Plains Theatre Conference

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

Historically, South Omaha is a melting pot where newcomers settle to claim a stake of the American Dream.

This hurly burly area’s blue-collar labor force was once largely Eastern European. The rich commerce of packing plants and stockyards filled brothels, bars and boardinghouses. The local economy flourished until the plants closed and the yards dwindled. Old-line residents and businesses moved out or died off. New arrivals from Mexico, Central America, South America and Africa have spurred a new boon. Repurposed industrial sites serve today’s community needs.

As a microcosm of the urban American experience it’s a ready-made tableaux for dramatists to explore. That’s what a stage director and playwrights will do in a Metropolitan Community College-Great Plains Theatre Conference project. The artists will interview residents to cultivate anecdotes. That material will inform short plays the artists develop for performance at the GPTC PlayFest’s community-based South Omaha Neighborhood Tapestries event in May.

Director Josh Hecht and two playwrights, Kia Corthron and Ruth Margraff, will discuss their process and preview what audiences can expect at a free Writing Workshop on Saturday, January 24 at 3 p.m. in MCC’s South Campus (24th and Q) Connector Building.

Participants Virgil Armendariz and Joseph Ramirez hail from Mexican immigrant clans that settled here when Hispanics were so few Armendariz says practically everybody knew each other. Their presence grew thanks to a few large families. Similarly, the Emma Early Bryant family grew a small but strong African-American enclave.

Each ethnic group “built their own little communities,” says Armendariz, who left school to join the Navy before working construction. “There were communities of Polish, Mexicans, Bohemians, Lithuanians, Italians, Irish. Those neighborhoods were like family and became kind of territorial. But it was interesting to see how they blended together because they all shared one thing – how hard they worked to make life better for themselves and their families. I still see that even now. A lot of people in South Omaha have inherited that entrepreneurial energy and inner strength. I feel like the blood, sweat and tears of generations of immigrants is in the soil of South Omaha.”

Armendariz, whose grandmother escaped the Mexican revolution and opened a popular pool hall here, became an entrepreneur himself. He says biases toward minorities and newcomers can’t be denied “but again there’s a common denominator everybody understands and that is people come here to build a future for their families, and that we can’t escape, no matter how invasive it might seem.”

He says recent immigrants and refugees practice more cultural traditions than he knew growing up. He and his wife, long active in the South Omaha Business Association, enjoy connecting to their own heritage through the Xiotal Ballet Folklorico troupe they support.

“These talented people present beautiful, colorful dance and music. When you put that face on the immigrant you see they are a rich part of our American past and a big contributor to our American future.”

Ramirez, whose parents fled the Cristero Revolt in Mexico, says he and his wife faced discrimination as a young working-class couple integrating an all-white neighborhood. But overall they found much opportunity. He became a bilingual notary public and union official while working at Armour and Co. He later served roles with the Urban League of Nebraska and the City of Omaha and directed the Chicano Awareness Center (now Latino Center of the Midlands). His activist-advocacy work included getting more construction contracts for minorities and summer jobs for youths. The devout Catholic lobbied the Omaha Archdiocese to offer its first Spanish-speaking Mass.

He’s still bullish about South Omaha, saying, “It’s a good place to live.”

Dorothy Patach came up in a white-collar middle-class Bohemian family, graduated South High, then college, and went on to a long career as a nursing care professional and educator. Later, she became Spring Lake Neighborhood Association president and activist, helping raise funds for Omaha’s first graffiti abatement wagon and filling in ravines used as dumping grounds. She says the South O neighborhood she lived in for seven decades was a mix of ethnicities and religions that found ways to coexist.

“Basically we lived by the Golden Rule – do unto others as you want them to do unto you – and we had no problems.”

She, too, is proud of her South O legacy and eager to share its rich history with artists and audiences.

MCC Theatre Program Coordinator Scott Working says, “The specifics of people’s lives can be universal and resonate with a wide audience. The South Omaha stories I’ve heard so far have been wonderful, and I can’t wait to help share them.”

Josh Hecht finds it fascinating South O’s “weathered the rise and fall of various industries” and absorbed “waves of different demographic populations.” “In both of these ways” he says, “the neighborhood seems archetypally American.” Hecht and Co. are working with local historian Gary Kastrick to mine more tidbits.

Hecht conceived the project when local residents put on “a kind of variety show ” for he and other visiting artists at South High in 2013.

“They performed everything from spoken word to dance to storytelling. They told stories about their lives and it was very clear how important it was for the community to share these stories with us.”

Hecht says he began “thinking of an interactive way where they share their lives and stories with us and we transform them into pieces of theater that we then reflect back to them.”

Working says, “This project will be a deeper exploration and more intimate exchange between members of the community and dramatic artists” than previous Tapestries.

The production is aptly slated for the Stockyards Exchange Building, the last existing remnant of South O’s vast packing-livestock empire.

![Mexican pride making strides [JUMP]“I’m not just teaching them dance, I’m teaching them how rich our culture is.” Hector Marino, founder of Omaha’s Xiotal Ballet Folklorico Mexican dance company](https://i0.wp.com/bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/omaha.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/4/96/4967bd2a-2be2-5fb9-8104-d897d4a9ce8f/5474eef0a80d4.image.jpg)