Archive

It’s a Hoops Culture at The SAL, Omaha’s Best Rec Basketball League

This is one of those scene-setting pieces I don’t do as much anymore. I like doing them, but they can take a lot of time and effort for very little return other than the satisfaction of doing these stories. The subject here is a recreational basketball league of the type that can be found in just about any urban neighborhood. The idea was to capture the vibe of this distinct subculture to the extent that I put you as the reader there in the bleachers with me. To make the story a visceral experience. The article originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com). Written as a secondary feature, I was surprised when it ended up on the cover. It’s not the first time that’s happened and I suspect it won’t be the last.

It’s a Hoops Culture at The SAL, Omaha’s Best Rec Basketball League

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Once the hoops get rolling in the Sunday men’s recreational basketball league, the scene turns into the kind of urban soul fest you associate with Chicago, Detroit, Philly or New York. Only this is Omaha. In an intimate, interactive community setting, the best summer ball in town is played in The SAL, Omaha’s version of the Harlem Ruckers League.

Housed until recently in the Salvation Army North Corps center at 2424 Pratt Street, the league, by concensus, draws the area’s best players. Many have serious credentials. A typical game features jocks from the pro and college ranks, past and present, along with former and future legends from The Hood. All strut their stuff before a knowledgeable, appreciative, vociferous throng.

NBA journeyman Rodney Buford, the ex-Creighton star, is a regular, rarely missing a game or a mid-range jump shot. One Sunday, fellow NBA player and ex-Bluejay Kyle Korver showed, raining down 3s to the fans’ delight. The league is so competitive Buford’s teams have never won the title. “That lets you know right there” said team sponsor Talonno “Lon Mac” Wright. “If you can make it through here, you’re a player. It’s the best competition you’re going to get in the city,” league director Kurt Mayo said.

Former UNO Mav Eddie King, who grew up balling in Chicago, said, “I think it’s a staple of north Omaha and I think it’s the best basketball in Nebraska, period. Oh, yes, you’re going to get challenged every game. Every team has good players. You can never get comfortable.” He said the close confines and neighborhood feel create a special environment. “This is the best atmosphere because everyone has family and friends in the stands. It’s a small gym and everyone’s on top of each other. People talk a little smack. That makes it fun. Plus, it’s real competitive. It’s streetball, but at the same time it’s fundamental, because 80 percent of these guys played ball at a four-year college.”

Mayo formed the league with wife Melissa in 2002, reviving a gym fallen into disuse. Before the Salvation Army, the league operated under a differnt name at the LaFern Williams Center in south O and the Butler-Gast YMCA up the street, where it’s back again. Mayo met resistance when he announced plans to move things to the Y at 3501 Ames Avenue. Trading the homey, if dingy, old digs for the gleaming, if cold, new facilities was an issue. But “the grumbling” ceased when the league ended the summer season at the Y on August 7. By all accounts, the new venue’s a hit, even if it lacks character. It does, however, have a nice wood floor, not some tacky mat like the Salvation Army center has. Mayo hopes to reinvent the magic at the Y with an “elite” level men’s Sunday league starting September 11.

But The SAL is where the league gained the rep and made the memories. Where it found a fun yet gritty flavor as a combined sports venue and social club.

James Simpson is among many who come each Sunday. Besides enjoying friends play ball there, he said, “it’s good for the community. I’ll follow it wherever it goes.”

“It’s the thing to do,” Wright said. “It’s like, Let’s get dressed, we’re going to The SAL. Everyone comes to watch the games or to see the women. There’s music. You meet people. You see your friends. On a good day, it’s just wall-to-wall packed. It gets loud. The crowd gets into it. if they like you, they’re cheering on you. If they hate you, they’re booing on you. If someone does something good out on the court, they ‘oooh’ and ‘ahhh.’ Some people might run out on the court, just having fun. It’s just a nice hangout. No problems. Everybody gets along. A little fussing here and there, but no big deal.”

Ex-Husker Bruce Chubick said there’s no dogging it in The SAL: “You can’t really half step your way through because there are too many players that are good. Plus, you get a nice little crowd that comes out, and they’ll let you know about it if you make a bad play. So, you’ve got that motivation going. It’s entertaining.”

The league is a subculture unto itself. The many female fans include spouses, lovers and groupies. Some mothers have children in tow. The guys taking-it-in range from hoop junkies looking for another fix to coaches scouting talent to neighborhood cats looking to escape the weather. The common denominator is a love for the game. It’s why some folks view five or six contests in a single sitting.

The hold basketball has in urban America is a function of the sport’s simplicity and expressiveness. Only a ball and a bucket are needed, after all, for players to create signature moves on the floor and in the air that separate them, their game and their persona from the pack. Not surprisingly, the hip-hop scene grew out of streetball culture, where trash talking equals rap, where a sweet crossover dribble or soaring airborne slam resembles dance and where stylin’ gets you props from the crowd or your crew. Music and hoops go hand-in-hand.

The vast majority of players at The SAL and Butler-Gast Y are black, which makes it ironic that the two-time defending champs, Old School, are an all-white group of former Division I players led by Chubick. In what Mayo considers “a traditional” league, Old School is short on style but long on fundamentals.

Former Omaha South and University of Washington star Will Perkins said to cut it in this league, “you’ve got to be tough…you’ve got to be skilled. You can’t just take your college game or your streetball game here. You’ve got to have a mixture.”

As the action unfolds on the funky, tile-like court everybody complains about, the spectators join in a kind of call-and-response exchange with participants. A player jamming home a thunder dunk will stop, await his fate from the crowd, and then either get their love or take their poison. A guy blowing a dunk or a layup or drawing air on his jumper gets well-deserved catcalls. But here the good-natured smack directed at refs and players is often hurled right back.

“Man, you gotta finish that! What are you doing? You had a wide open layup. Hey, y’all gotta fight for this one, fellas. They’re not going to give it to you. C’mon!”

Unrestrained displays of emotion, usually shouted down from the bleaches, sometimes overflows onto the court. Despite threats and invectives, few incidents ever come to blows. Chest thumping and trash talking is just part of the heat and the edge. It’s all about respect out here. No one wants to be shown up.

As day wends into night, and one game bleeds into another, there’s a constant stream of humanity in and out of the cramped old gym, where music thumps from a boom box during time outs and between games, where burgers, dogs and nachos can be had on the cheap and where vendors hawk newly burned CDs and DVDs.

Amid the hustle and flow, players and fans intermingle, making it hard to tell them apart. There’s no barriers, no admission, no registration. It’s a straight-up come-and-go-as-you-please scene. As the small bleachers hold only a couple hundred people, the rest of the onlookers line both sides and ends of the court. Folks variously stand against walls, sit in folding chairs or sprawl on the floor.

The league serves many purposes. For college programs at UNO and Bellevue, it’s a way to keep teams sharp over the summer and toughened up for the coming NCAA season. Kevin McKenna, UNO head coach the past four years until rejoining the Creighton staff this summer, said, “I got my team to play down there the past few summers because I thought it was the best league. There was another league in town, but I felt this was the most competitive — where’d we get the most out of it.” Bellevue University coach Todd Eisner has recruited there. It helps Omaha Central grad and current Illinois-Chicago player Karl White get ready for the college grind.

For former college mates, like the Still Hoopin’ squad made up of such ex-Bluejays as Buford, Latrell Wrightsell and Duan Cole, it’s a chance to relive old times, stay fit and feed still hot competitive fires. For Buford, it’s one more workout in an off-season regimen before NBA training camps begin. For men pushing 30, 40 or older, it’s also a pride thing — to show they still have some game left. For them and guys not so far removed from the game like Alvin Mitchell, the former NU, Cincinnati and UNO player, or Andre Tarpley, a senior last year at UNO, or Luther Hall, a recent Bellevue U. grad, it’s both an outlet and a place to prep for pro tryouts.

Danai “Ice” Young, whose college hoops career stalled at NU, is using the league as a launching pad to try and make the ABA River City Ballers’ roster. Albert R. went from The SAL to a spot on the pro streetball tour, where he goes by “Memphis.”

For youngbloods, it’s a test to prove they can hang with the old dogs. “If you’re the best talent, or think you’re the best talent, this is where you’re going to be,” said veteran ref Mark LeFlore, Sr. Mayo said few high schoolers have had what it takes to play in The SAL. Two that did, guards Matt Culliver and Brandon McGruder, formed one of the highest scoring duos in the annals of the Metro Conference at Bryan High School last year. Both earned scholarships to play at the next level.

Another youth, Aaryon “Bird” Williams, is perhaps the most impressive of the pups as he’s only a senior-to-be at Omaha North, where he played in a handful of varsity games last year after moving here with his family from Gary, Indiana. Mayo sees a phenom in-the-making in Williams. “Man, he was dunkin’ on everybody. You have to see it to believe it. He’s definitely a man-child. He reminds me of a young K.G (Kevin Garnett), and I’m not exaggerating,” Mayo said. “He’s a beast.” It’s another example, Mayo said, of how top local talents “find their way” to the league. “I’m already missing The SAL, but I’m recreating it at the Y. The tradition continues.”

Related Articles

- King of the courts: Rucker Park defends its streetball crown (thegrio.com)

- Streetball legend ‘Homicide’ to turn in his kicks (nypost.com)

- Artest returns to streetball roots, wants second ring (nypost.com)

- Omaha Native Steve Marantz Looks Back at the City’s ’68 Racial Divide Through the Prism of Hoops in His New Book, ‘The Rhythm Boys of Omaha Central’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Troy Jackson: Streetballer Nicknamed “Escalade” Dies at 35 (bleacherreport.com)

- Bismack Biyombo Breaks Out At Nike Hoop Summit As NBA-Ready Right Now (sbnation.com)

- Back in the Day, Native Omaha Days is Reunion, Homecoming, Heritage Celebration and Party All in One (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Ties that Bind, One Family’s Celebration of Native Omaha Days (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Ex-Prizefighter and Con Turned-Preacher Man Morris Jackson Spreads the Good News

I knew the name Morris Jackson growing up because my older brother Dan was a boxing fan and I think he saw one of the grudge bouts between Jackson, the slick boxer, and Ron Stander, the Great White Hope slugger. Jackson was undeniably the superior boxer but it was Stander not Jackson who got a title shot against Joe Frazier. As the years went by I lost track of Jackson, only to read one day in the local daily about how he had gotten in trouble with the law and done time behind bars. There, he had a born again experience of such magnitude that after serving his time he went on to become a minister. His chosen ministry is poetic justice, too, as he pastors to incarcerated men. I finally got to meet and profile Jackson a few years ago. The story for The Reader (www.thereader.com) about Jackson and his transformation follows. My stories about Morris’ then-nemesis, Ron Stander, can also be found in this blog site, along with other stories about Omaha boxers, boxing coaches and gyms. Like most writers, I am always down for a good boxing story. There are several yet in me that I wish to tell and I am sure that others will reveal themselves when I least expect it.

Ex-Prizefighter and Con Turned-Preacher Man Morris Jackson Spreads the Good News

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In his best three-piece, GQ-style suit, Morris Jackson looks like just another slick do-gooder to prisoners seeing him for the first time at the Douglas County Correctional Facility, where he’s chaplain with Good News Jail and Prison Ministry. But the large man soon separates himself from the pack when he tells them he used to be a prizefighter. Rattling off the famous names he met inside the ring — Ron Stander, Ernie Shavers, Ron Lyle, Larry Holmes — usually gets their attention. If not, what he says next, does. “My number is 30398.” That’s right, this preacher man did time. The former convict now stands on the other side of the cell as a born-again Christian and International Assemblies of God-ordained minister.

His 1975 armed robbery conviction sent him to the Nebraska Men’s Reformatory for a term of three to nine years. He served 22 months, plus seven more on work release. But being locked away wasn’t enough to reform Morris. His rebirth only happened years later, after squandering his freedom in a fast life leading to perdition. Referring to that transformation, one of several makeovers in his life, is enough to make even hardcore recidivists listen to his message of redemption.

“Then they hang on every word you’ve got to say, because they see a change. They really can’t believe you were there once yourself. Having Christ in your life really makes a big difference. Actually, it’s almost a visible presence — in your eyes, in your demeanor, in your voice, in your conversation — that people can notice,” said Jackson, whose prison ministry work dates back to 1992.

He first returned to the correctional system doing mission work for northwest Omaha’s Glad Tidings Church, where he still worships today. Reliving his incarceration experience behind the secured walls made him anxious.

“The first time I went, it was with fear and trembling because the last place I wanted to be in was anybody’s jail, hearing the doors close behind me,” he said.

To his relief, though, he sensed he had found a calling as an evangelist to cons.

“It was just as if I was right where I was supposed to be. The words were there. The life. The testimony. The word of God. My studies. The first time I did a service in the county jail there were 66 men present and 44 of those professed faith in Jesus Christ when given the opportunity. I said, ‘Man, I like this. I could do this all the time.’ Like I tell people, ‘Be careful what you say, because God is listening.’ I’m exactly where God wants me to be and I’m doing exactly what he wants me to do.”

Jackson’s had many occasions to reinvent himself, stemming back to his Texas childhood. As a youth, he lived with his family in an upper middle class part of Dallas. Then, he found out the man he thought was his father was actually his step-father. His real father was killed when Jackson was a year-old. Soon after this revelation, his mother and step-father split up and his world unraveled again. His mother got custody of him and his sister, but she could only afford a place in the projects. Already distraught over the divorce and the discovery he’d been lied to, he expressed his rage on the streets, where fighting was a rite of passage and survival mechanism in an area ruled by gangs.

“In Dallas, in the projects, you either had to be a good fighter or a fast runner, and I never could run too fast. I went from being a person who would see a fight coming and move away from it, to initiating fights. If you’d so much as look at me wrong, I’d haul off and hit you. I was getting into three-four fights a week. It was crazy. I guess I was an angry young man. Yet, I considered myself a meek person. I describe a meek person as a steel fist in a velvet glove. I would do everything I could to get out of a fight, but when I got cornered and I had to fight, I never lost one. Sometimes, I lost my temper and did something stupid.”

During this time, he lived a kind of double life. He was a star high school football and basketball player and a regular churchgoer, but also a notorious gangsta. His mother had grown up in the church before drifting away. When she found religion again, she made Morris and his sister attend services. He chafed at the fire-and-brimstone admonitions hollered down from the pulpit.

“The church I was raised in, you never heard a lot about grace. It was a lot of dos and donts and laws. You don’t smoke…don’t chew…don’t drink…don’t mess with girls. Of course, when I came of age where I could make my own decisions, there was no way I could live that kind of life when everybody else was having fun and I wasn’t doing anything.”

When his rebellion got to be too much, his mother kicked him out of the house. He went to live with his sister, stealing food to help support themselves.

His mother relocated to Omaha, where she had family, and she sent for her unrepentant son, hoping he’d find himself here. For a time, he did. He even prayed to lose his hair’s-edge temper, and it did leave him. When a neighbor training for the Golden Gloves prodded the strapping Jackson to join him at the old Swedish Auditorium, the newcomer did and soon found a home in the sport. Recognizing his talent, veteran handlers Harley Cooper, Leonard Hawkins, Ronnie Sutton, Don Slaughter and Yano DiGiacomo variously worked with him at the Foxhole Gym.

In his first amateur bout, he laid out cold his hulking opponent in a Lincoln smoker. His very next fight pitted him against the man who proved to be his main nemesis — Ron “The Bluffs Butcher” Stander. From the late 1960s through the early 1970s, they met six times — four as amateurs and twice as pros — in highly competitive, well-attended bouts. “People came out to see us fight,” said Jackson. Their matches drew crowds of 6,000-7,000. Each took the measure of the other, although Stander, Omaha’s then-Great White Hope, usually came out on top. Stander took four of the contests, including one by KO, Morris won a decision and a sixth encounter ended in a controversial draw most felt should have been a Morris win.

“Every time I turned around, there was Morris. He was my biggest, toughest opponent,” Stander said.” “Yeah, we went at it quite a bit. We just happened to come along at the same time,” Jackson said.

The intense rivalry was tailor-made for fans as the fighters embodied the classic adage that styles make fights. Jackson was the boxer, Stander the puncher. Jackson relied on his feet. Stander, on his brawn. One was black, the other white. In the era of militant Muhammad Ali, Jackson was the closest thing Omaha had to a righteous Brother bringing down The Man. Stander, meanwhile, was a real-life Rocky who got his shot at the title in a 1972 bout with champ Joe Frazier.

Morris Jackson in his fighting days

“I don’t know if I patterned myself after Ali, but I was somewhat like him because I would stick, move, think, box. I was light on my feet. But I wasn’t the type of person who talked a lot. I didn’t have any gimmicks or shuffles. I just got in and took care of business,” Jackson said.

The two long retired fighters reside in Omaha, but rarely mix. While their rivalry was too close for them to ever be friends outside the ring during their fighting days, they’ve always maintained the mutual respect warriors have for each other.

Stander is well aware of the transformation Jackson has undergone and admires his old foe for it. “He turned himself around. Yeah, he went from bad to good in a big way. God blessed him. God grabbed Morris by the neck and said, ‘Come over to me.’ Yeah, he’s a beautiful man now, I’ll tell ya.”

Ron Stander, known as the Butcher, went face to fist with Joe Frazier in Omaha in 1972. CreditUnited Press International

By most measures, Stander’s career surpassed Jackson’s, whose early promise ended in missed chances, bad matches, poor management, and too small takes. The familiar litany of a club fighter who never got his shot the way Stander did. Former Omaha matchmaker Tom Lovgren feels Jackson could have gone farther. Still, the fighter was once in line to join promoter Don King’s stable. He was a main eventer in Omaha’s last Golden Era of boxing. A two-time Midwest Golden Gloves champion, he compiled a 28-5-1 career pro record, including a KO of then-British Commonwealth champion Dan McALinden, a win Lovgren rates as the top by any Omaha boxer in the ‘70s. Jackson was also a sparring partner for ring legends Ron Lyle, Ernie Shavers, Joe Bugner and future champ Larry Holmes.

But then the good times ended. His run-in with the law came during a dry spell when the journeyman “couldn’t get any fights.” As he tells it, “I started running with some old friends who’d been in the joint and I was influenced by them to make some quick money in the hold up a Shaver’s food mart.” Once nabbed, he was almost grateful, he said, “because eventually somebody was going to get hurt.”

His crime spree was brief but telling and foreshadowed a later descent that threatened to land him back in jail or kill him.

While serving his stretch, Jackson studied Islam and became a Black Muslim. His dalliance with spirituality was short-lived, however. After getting out, he tried resurrecting his career but after three fights called it quits. Like many an ex-pug, he had few prospects beyond the ring and, so, he grabbed the first thing offered — bouncing at strip clubs.

“I got caught up in this lifestyle. I got to smoking marijuana and doing all the things that go with that lifestyle. My wife was working days and I was bouncing nights. We hardly ever saw each other. I was just kind of in limbo and that led to the brawls and the drinking and the drugs,” he said.

Morris Jackson today

He never imagined being saved. “No. If someone would have told me, I would have said, ‘Yeah, right, you’re crazy man. Give me some of what you’re smoking.’” It was his mother who finally pulled him from the brink and back into the fold of the church. In March 1983 she staged a one-woman intervention with her wayward son. “My mother came over to my house to talk to me about what my life was like and how Christ was calling me. She shared the gospel with me in such a way as I’d never heard it before. She spoke of God’s grace. How He loves you. How He has a purpose and a plan for your life. And how it’s up to you to accept and follow the path God has for you.” What came next can only be called salvation.

“I had this sense and I heard this voice that said. ‘The line is drawn in the sand and if you don’t make the decision now, you’ll never get another chance.’ I know just as sure as I’m sitting here today that if I wouldn’t have accepted Jesus Christ in my life, I’d be gone. I’d be dead. My mother prayed. We prayed. And the next day I went to church with her.”

Church bible classes led to college religious studies and, ultimately, his ordination. His first ministry was on the streets of north Omaha. Then came the prison gig. In the mid-’90s, then-Nebraska Governor Ben Nelson granted him a full pardon.

Now, he can’t imagine going back to that old life, although he keeps memories of it nearby as a reminder of where he came from. “There’s a peace in my life. Serenity. Stability. Certainty. It makes a difference when you come from darkness to light,” he said. “I know what my life used to be like. The turmoil, the uncertainty. Spinning my wheels. Living for the weekends. No purpose.”

Living his faith, which he loudly proclaims from the inscription above his home’s front door to the message on his answering machine, is his way of telling the good news. As he tells prisoners: “You’ve got to believe in something.” He’s seen enough cons turn their lives around to know his story is not an aberration.

The proud old fighter sees his ministry as his new battleground, only instead of knocking heads, he’s about saving souls and staying straight. “Most of my teaching is biblical principles applied to our lives. I’m still a warrior. Only now when I put on my armor and go to war every day, I don’t feel turmoil. My wars are fought in my prayer closet. I pray before I do anything,” he said.

But once a fighter, always a fighter. He repeated something Ron Stander said: “If they told us to lace ‘em up again, we’d go at it.” The Preacher versus the Butcher. Now wouldn’t that be a card?

Related Articles

- World Heavyweight Boxing Championship 1960-1975 (sportales.com)

- Meldrick Taylor vs. Julio Caesar Chavez: The Greatest Prizefight Ever? (bleacherreport.com)

- James Kirkland: Ex-Convict Will KO Japanese Prizefighter Within 7 Rounds Tonight (bleacherreport.com)

A Good Deal: George Pfeifer and Tom Krehbiel are the Ties that Bind Boys Town Hoops

Here’s another Boys Town sports story. It’s about tradition and legacy and giving back, George Pfeifer played for legendary Boys Town coach Skip Palrang when the school‘s founder, Father Edward Flanagan, was still there. After Pfeifer graduated high school and served in World War II he came back to Boys Town to coach under Palrang. Later, he took over as head basketball coach, leading the hoops program to some of its greatest successes. Now, many years into retirement, he’s back again, this time as a kind of unofficial coach and mentor, at the invitation of current head basketball coach Tom Krehbiel. The old coach and the young coach have bonded like father and son and together they’ve helped Boys Town recapture some of the magic that made the school’s athletic teams juggernauts back in the day.

The story originally appeared in the New Horizons.

A Good Deal: George Pfeifer and Tom Krehbiel are the Ties that Bind Boys Town Hoops

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

When George Pfeifer coached the Boys Town varsity basketball team in the 1960s to great success, he used an adage with his players, “Get a good deal,” as a way of impressing upon them the advantage of working the ball to get an open shot.

The 81-year-old is long retired but a special tie he’s forged with current BT head basketball coach Tom Krehbiel finds Pfeifer offering kids young enough to be his grandchildren the same sage advice he gave players decades before. Krehbiel credits the recent turnaround in BT hoops — culminating in a Class C-1 state title last season — to the input of his unofficial assistant. “Coach Pfeifer is, in my mind, the school’s all-time greatest basketball coach. I wanted to get him involved in the program. I reached out to him and he’s been a big part of our program ever since. I don’t think it’s a coincidence we started winning” once he got involved, said Krehbiel, who previously coached at Omaha Skutt High School.

The association between the men peaked last season when the Cowboys’ won their first state championship in 40 years. Until beating Louisville in the finals, the school hadn’t won a state roundball title since 1966, when Pfeifer was head coach. That ‘66 crown was the second of back-to-back Class A titles won by Pfeifer’s teams, squads considered two of the best ever to play in Nebraska prep history. It was an era of athletic dominance by the Cowboys.

Since the summer before the 2003-2004 season, when he accepted Krehbiel’s invitation, Pfeifer’s worked with BT hoops. When his arthritis isn’t too bad, the tall man with the folksy manner makes his way on campus, over to the Skip Palrang Memorial Field House named after the legendary man he played and coached under and where he toiled away countless hours on drills.

He’ll keenly observe practice from the sideline, noting things he sees need correcting. This recent Nebraska High School Sports Hall of Fame inductee is still a master diagnostician at breaking down systems and plays. He does the same when he goes to see a Boys Town game or analyzes tape of one, as his sharp mind dissects the action with razor precision.

“He’ll notice little technical things that only someone who knows basketball can detect. He really sees and knows the game. It’s amazing,” Krehbiel said.

Pfeifer shares his insights with the players, kids not unlike the ones he coached years ago — boys full of attitude but hungry for love. Krehbiel said Pfeifer knows just how to prod people to improve. “He doesn’t criticize — he kind of suggests.”

Tremayne Hill, a starting guard from last year’s team whom Pfeifer got close to, said the old coach got the most out of him with his “encouraging” words. “He told us to stay positive and to work hard in trying to overcome adversity. He was a lot like a father figure,” said Hill, adding Pfeifer and Krehbiel are like a father-son team.

It doesn’t surprise Pfeifer he can get through to kids weaned on PlayStation and X-Box, not Fibber Magee and Molly. You see, he was a BT resident himself from 1939 to 1943, giving him a bond he feels makes him forever simpatico with kids there. It’s why his reconnection with the institution is more than a former coach returning to the fold. It’s a son or brother coming home to his family. It’s why the vast age difference doesn’t hamper him in talking to today’s kids.

“I talk their language,” Pfeifer said. “I grew up there, so I know. When I first went back out there I said, ‘Yeah, I’m an old fogy, but I used to be out here. I know all the tricks you guys know, so you can’t trick me on anything. You can’t tell me anything I haven’t heard. I was just like you guys. My heart’s with you guys. I know what you’re going through. I’m here to be a friend of yours.’”

Hill said Pfeifer’s BT roots make a difference as “he knows the type of stuff we go through. He knows how to relate to us. More than another coach would.”

Pfeifer said he and the team developed a strong bond. “When I’d come out there, some of the kids warming up before the game would come over and say, ‘God, we’re glad to see you coach. You feeling alright? We’re going to play hard for you.’ That last night when they accepted the trophy the one kid held it up and said, ‘This is for you coach Pfeifer…’ Those are the kind of kids….” Choked with emotion, Pfeifer’s voice trailed off.

When Pfeifer coached in the ‘60s he did something rare then — starting five African Americans. One morning after a game, a caller demanded, “Why you playing all them n______s?” “Because they’re my five best players,” Pfeifer replied. Ken Geddes, a member of those teams, said race “was never even an issue.” Lamont McCarty, a teammate, said, “If you didn’t perform, you didn’t play… plain and simple. He was a wonderful coach. Same thing with Skip Palrang.”

As is now a custom, Krehbiel had Pfeifer address the assembled 2006-2007 team at a mid-November practice. It was Pfeifer’s first contact with the team. He’d have been there before if not for tending to his terminally ill wife Jean. Gathered round him were about two dozen players, many of them new faces after the loss of so many off last year’s team to graduation. Pfeifer owned their rapt attention.

He told them he was 13 when his father died. Left unsaid was the Depression was on, and with his widowed mother unable to support the poor Kansas farm family she sent him and a brother to Boys Town. There young George blossomed under iconic founder Rev. Edward Flanagan and star coach Skip Palrang..

Pfeifer also didn’t mention he became BT’s mayor (as did his brother) and excelled in football and basketball. That he developed an itch to give back to youth what he’d received. After serving in the U.S, Navy during World War II he coached at Fort Hays State down in Kansas, before accepting an offer to join Palrang’s BT staff. Intending to stay five years, Pfeifer, by then married with children, made it a 30-year career. He was a coach, a teacher and principal of the elementary school.

“I knew I wanted to be there to help those type of kids,” Pfeifer said of BT students past and present. “You know, they come there with a hole in their heart. Nobody cares about them, nobody encourages them –- they just think there’s no way they can make it. We set up goals and objectives. We praise them when they succeed. When a kid comes up to you and says, ‘God, I wish you were my dad,’ well, those kind of grab you. Then you know you made a difference.”

The campus holds a dear place in Pfeifer’s heart. It’s home. The people there, his family. He stays in touch with players by phone, letter, e-mail. He’s a regular at school reunions. But until Krehbiel asked him to come back as a consultant, Pfeifer hadn’t really felt welcome by previous coaches.

“I think he had a desire to get back close to the program, to his home and to this community, and so the timing was right,” said Krehbiel, a Burlington, Iowa native with his own ties to the place. His father worked there and as a youngster Krehbiel spent many a summer day on campus, running about and canoeing in the pond. “So I always knew Boys Town,” he said. “I loved it.”

As Pfeifer spoke to the kids that late afternoon in November, he was every inch the coach again, instilling values and commanding respect.

“There’s nobody working here that doesn’t love you, I guarantee you,” he told them in measured tones.” “So listen to your family teachers, listen to your coaches, work hard, study in school. You have great coaches, good facilities. You’ve got everything you need, except you got to do your part. You gotta keep your nose clean. Don’t get in no trouble. Do what you’re told. Coach is going to tell you what he wants you to learn, how you’re going to do this and he’s going to tell you why. Those are three really important parts of your basketball training.

“It takes a lot of hard work. You have to be focused. No matter what happens outside, you come here and be ready for basketball.”

After Pfeifer wished them good luck and some players responded with, “Thanks, coach,” the huddled team charged back into practice.

“If they know that you care about them and that you’re there for them, they’ll work for you — they’ll work hard. They appreciate you,” Pfeifer said.

“It’s funny. Kids today are real hip-hop, you know, with this Snoop Dog slang and coach uses old school terminology that I cringe at sometimes, assuming the kids think its kind of corny, but the kids like it. I think too he provides a grandfatherly figure,” Krehbiel said. “These kids, more than any kids I’ve ever been around, they want somebody to take an interest.

“He wants to help…It really comes down to his true interest and love for the kids in the program. He’s trying to give them that last tidbit…to help them on the court and help them in life. I think when he looks at our team and he’s rooting for these kids it’s like rooting for his family, his own kids or his own brothers….He gets emotional when he talks about this place. It’s his home.”

It’s that been there-done that experience Pfeifer brings that Krehbiel wanted for his players. Then there’s the “link to success” Pfeifer represents.

“He laid the foundation 40 years ago for all the nice things that have been said about us the last two or three years,” Krehbiel said. “I think we’re all proud to carry on a rich tradition. It’s just an honor to be associated with him. I was always taught to appreciate the people that came before you…You gotta respect the people who built up the history and this place is just full of history.”

What Krehbiel got in the figure of Pfeifer was more than he could have imagined.

“Coach has been a great mentor to me and a great resource for us,” he said. “You know he’s having an impact on our kids when after the state championship one of our starting five interviewed on TV” — Dwaine Wright — “spent his whole time on camera referencing coach Pfeifer, saying, ‘He told me in practice to get the good shots.’ We didn’t prompt him to do that. It just came out of his heart. You realize, Wow, this is an 80-some-year-old man having an affect on an 18-19 year-old kid. I was proud of our kids for the respect they showed coach. I’m proud of coach.”

Pfeifer appreciates that Krehbiel sought his counsel, thus allowing him to be a teacher again. “He was so sincere and open about establishing a good relationship. He was willing to receive me and invest in some of my knowledge,” Pfeifer said. “A lot of guys that coach, they think they know it all. But he’s really receptive. And that’s great for me because I didn’t feel that with some of the other people that were out there. I said, ‘I’ll be happy to help you out anyway I can.’”

When Krehbiel first approached him, he had no clear expectation other than getting some advice on the special demands of being a BT coach.

“This is a unique position,” Krehbiel said, “maybe as unique a position as there is in the country in high school because you’re in a home for boys. There’s not only the athletics parts of it but there’s the home campus part of it, dealing with the troubled youth, the homeless youth, with all the things they present.

“There are very few people who’ve had this position. There’s just a few of us around. There’s even fewer that have had the kind of success coach had.”

Krehbiel did some research in the BT and Omaha World-Herald archives in compiling a school record book and came away duly impressed by just “how successful” Pfeifer was at producing winning teams. In 14 years as head coach — 1959 to 1973 — his teams won 205 games and lost only 82. He led nine teams to the state tourney and guided a pair to state titles. His track and field teams were also a formidable bunch, always a threat at the state meet.

For Krehbiel, welcoming back someone like Pfeifer who’d given the best years of his life to BT was a way of honoring the man.

“My initial intention was to just try to give back to him for all the years he gave to Boys Town. My initial thought was to get him up here to one practice at the beginning of the year, and it’s morphed into a great relationship and friendship,” said Krehbiel, whose wife and five daughters all know Pfeifer.

Still, it took some convincing for Pfeifer to meet with Krehbiel that first time.

“I called him up out of the blue and introduced myself. He was real reluctant but I finally got him to agree to go lunch with me at Big Fred’s. He told stories for hours.

That’s when I told him, ‘You are welcome anytime.’ That fall I asked him to come out to practice. I gave him a pad of paper and a pen and said, ‘Watch me coach practice. Watch our kids. Give me some feedback about our team.’ He did that and from that point on he’s been popping in at practices whenever he feels like it.”

It didn’t happen overnight. Pfeifer eased his way in, not wanting to impose himself, less he undermine Krehbiel’s authority.

“When it first started we’d talk maybe once every couple weeks,” Krehbiel said. “He wouldn’t come to practices much. As he and I became closer and he became closer with all the other coaches, there was a comfort level. Last year he was out here about two or three times a week prior to the season opener, and we’d be talking about offenses and defenses and philosophies back and forth.

“I was reaching out initially to find out, ‘How did you handle the job? How did you handle the kids? What are the issues beyond basketball I should know about?’ Then when he and I started talking I found just how solid his philosophies are in basketball and in life and I really wanted to get to know him more. You just can’t help but sense the way he approached things and did things is probably the best way as well as the right way to have a lot of success. I try to emulate him.”

It doesn’t hurt that the two are cut from the same cloth. “Our personalities are a lot alike, so there’s a bond person-to-person, coach-to-coach,” Krehbiel said. That’s not to say these two see eye to eye on everything.

“He believes in zone defense and I believe in man to man,” Krehbiel said. “But that’s the fun of it — debating the merits of each. But,” he added, “as far as what we demand of our players, how we treat our players,” they’re on the same page.

It wasn’t until Krehbiel watched Pfeifer interact with the players that he understood all that the venerable old coach could bring.

“Then when I saw him around the kids and I saw how he still has a lot of viable, valuable contributions…and I saw the kids take to him, it obviously was a great idea to have him around. It’s just kind of matured into what it is today. He’s around quite a bit. As much as he wants to be. The door is always open.”

Along the way, Pfeifer’s shared some coaching secrets, including a list of offensive- defensive Dos and Donts and his mantra for teaching “technique, technique, technique” he got from coaching great Skip Palrang. Pfeifer’s passed along full-court press and matchup-zone tactics that made his teams so hard to beat. Above all, he’s preached taking the high percentage shot and protecting “the hole.”

“He gave me a file folder of his coaching notes and a card with his pregame preparation notes,” Krehbiel said. “I read through it all and I copied it down in my own words and style. That’s the relationship he and I’ve built up. For him to give that to me, I mean, what do you say? That should tell anyone a lot about his willingness to give. I think he really, really wants this program to be successful and those are the lengths he’s willing to go.”

What Pfeifer does for BT hoops can’t truly be measured.

“He doesn’t come out and design plays and run drills. He’s in the background helping the coaches. He’s really helped me in my preparation for games. He talks to players one one one,” Krehbiel said. “The last couple years he’d take some of our better players aside, real fatherly like, and say, ‘Here’s what I see in your game. Take the good shots, not the bad shots.’”

Wishing to remain in the background, Pfeifer chooses not to sit on the bench, but in the stands during games. He’s always watching, however.

As last year’s team stormed through the season, losing only four times, including twice to Wahoo Neumann, Pfeifer noted a tendency for BT players to settle for three-point shots and to play soft in the middle. With his adjustments the Cowboys avenged Neumann in the first round of the state tourney.

When last year’s star player, starting center and then-BT Mayor Vince Marshall, felt good about a game in which he scored well but recorded few rebounds, Pfeifer had a heart to heart talk with him. “I said, ‘I was mayor when I was at Boys Town. You’re the mayor and you got only three rebounds last game. What the hell were you doing? You’re the mayor, you’re going to make me look bad. Get your ass on the boards.’ That’s the way we talked. We were brothers.”

Pfeifer’s known to intervene when emotions run over. Once, after a so-so practice on the eve of state, the admittedly “fiery” Krehbiel lost his cool when he noticed a couple players cutting up. “I lose it. I go up one kid and down another. I was furious they wouldn’t take this seriously,” Krehbiel said. “And here comes coach. He gets off his chair and gets right in the middle of us and says, ‘Wait a minute.’ I immediately shut up. He takes over and says something about not getting a big head and keeping yourself together and staying in the moment.

“He was just that calming influence and that’s what he’s been. I’ve really calmed my demeanor in regards to the sidelines and the game-time stuff in my conversations with him. He’s really helped me with the handling of the kids around here. He reminds me they’re always watching you and they’re going to play off your demeanor. He’s a sounding board. I can pick up the phone and say, ‘Coach, we’ve had this issue with a young man, how would you handle that?’ He gives me tidbits on how to handle certain situations as head coach.”

Pfeifer can still get fired up, as when he pulled his BT athletic jacket out of moth balls for a school pep rally to show how much he bleeds Big Blue. He told the crowd, “I’ve waited 40 years to wear this thing again.”

There’s the sense of a circle being closed. That what Pfeifer got from Palrang is being handed down to Krehbiel. Lessons from 65 years ago live on, no doubt to be carried on by the young men Krehbiel and Pfeifer work with today.

“The greatest thing for me, bar none, is to have my name linked with coach Pfeifer’s name and coach Palrang’s name in the same sentence. To be linked to that history is overwhelming,” Krehbiel said. When Pfeifer couldn’t get away to Lincoln to accept his Hall of Fame induction, he asked Krehbiel to accept in his place. For Pfeifer, Krehbiel was the natural choice. “I love him,” Pfeifer said of his coaching protege. “What an honor to accept for him. That just fortified our relationship. He’s a good old guy,” a tearful Krehbiel said.

Krehbiel met many athletes Pfeifer coached. They were disappointed he couldn’t make it. “They all love him. Guys came in from both coasts and from all over the country to honor him with this induction, which was long overdue,” Krehbiel said. One of Pfeifer’s favorites, Charles ”Deacon” Jones, a standout BT miler and football player who became a University of Iowa All American and two-time Olympic long distance runner, was inducted into the Hall the same night.

“I know it was killing coach not to be able to go and to be on the stage with Deacon,” Krehbiel said. But Deacon and the rest know Pfeifer was there with them in spirit. Like he always has been and will be. A brother under the skin.

Krehbiel never competed for Pfeifer, but considers it a privilege coaching with him and “seeing all he does around kids.” He said it seems he and the players benefit more from the relationship than Pfeifer does. However, he added, “I hope we’re helping keep him active.” It’s clear when Pfeifer talks hoops it takes his mind off, if only a little while, his wife. Krehbiel’s visited Pfeifer at his house during this hard time. Krehbiel’s daughters say prayers for Jean.

Perhaps the old coach’s greatest joy comes from watching his young protege catch the same passion he caught for Boys Town. Pfeifer said, “I’ve told him, ‘Tom, if you stay there long enough you’re going to get what I got.’ It’s a fever.” Krehbiel said the example of Pfeifer is one reason “why I stay here. It’s why I’ll always be here.”

Related Articles

- It took B.C. hoops stalwart Bill Disbrow a while to glean master’s secret (canada.com)

- Legendary Eathorne Touched Countless Lives (kitsapsun.com)

- Remembering John Wooden, the Wizard of Westwood (time.com)

- Legendary basketball coach Wooden dies (cnn.com)

Rich Boys Town sports legacy recalled

If you’re interested in another Boys Town sports story, then check out my story, “A Good Deal: George Pfeifer and Tom Krehbiel are the Ties that Bind Boys Town Hoops” on this blog. More o f my Boys Town stories on this site cover various topics, including the classic 1938 MGM film Boys Town, the friendship of Fr. Edward Flanagan and Jewish attorney Henry Monsky, and the 1972 Sun Newspapers Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation of Boys Town finances.

The following story originally appeared in Nebraska Life Magazine. Look for more Boys Town stories in future posts.

Rich Boys Town sports legacy recalled

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in Nebraska Life Magazine

“I didn’t know a jock strap from a toothbrush,” said alumnus George Pfeifer of his arrival at Boys Town from a Kansas farm in 1939. Like some of the finest athletes at Rev. Edward Flanagan’s home for “lost” boys, the future coach had never played organized sports before coming there. Most of the boys were either poor inner city or rural kids who’d played only sandlot ball or street ball. They came from all parts of the country, boys with different racial, ethnic and religious backgrounds, and on their shoulders was built an athletic dynasty that became the envy of the nation.

From the Great Depression through the 1960s, the Boys Town football team played elite Catholic prep schools and military academies in Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, New York, Miami and other cites. The games attracted dignitaries and made headlines. Playing against the nation’s toughest competition in large stadiums before tens of thousands of fans, the Cowboys won more than twice as often as they lost.

During the same era, Boys Town won multiple state championships in football and basketball, and produced scores of all-state athletes and individual champions, even some high school All-Americans. Its great track-and-field athletes include two-time Olympian Charles “Deacon” Jones (1956 and 1960) and quarter-miler Jimmy Johnson, who won the Pan Am Games only a few years after graduating.

It began with the dream of Boys Town’s founder, Father Flanagan, who was a fair soccer and handball player in his day, and a vocal champion of sports. He made sports an integral, even compulsory part of residents’ experience at Boys Town. Intramural athletics became a big deal. In those days, the boys lived in dorms and staged competitions between their respective buildings to see who were kings of the field or the court. By the mid-1930s, Flanagan hired a coach and pushed for Boys Town to compete in sanctioned interscholastic events.

Born and raised in Ireland, Flanagan made his long-held dream for Boys Town a reality through conviction, blarney and bluff. With his silver-tongued brogue and big sad eyes, he elicited sympathy and loosened purse strings for the plight of America’s orphaned. With his politician’s ability to build consensus, he got people of all persuasions and faiths to contribute to the home.

It didn’t hurt that Flanagan harbored a bit of P.T. Barnum in his soul. Almost from the start of the home in 1917, he made use of the media to further the cause of children’s care and rights. In the 1920s he hosted a nationally syndicated Sunday radio program, “Links of Love,” broadcast from the old WOW studios in Omaha. On a larger scale, there was the 1938 MGM box office smash “Boys Town,” starring Spencer Tracy and Mickey Rooney. Tracy won the Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of Flanagan.

The movie made Flanagan and BT household names. He used his and the home’s growing reputation to bring national figures, including sports stars, to “the city of little men.” The BT archives detail visits by such sports icons as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis. Hollywood celebrities were also frequent visitors. “Deacon” Jones, then learning the barber trade at BT, recalls being summoned with his clippers to the quarters of Flanagan’s successor, Rev. Nicholas Wegner, where he found Spencer Tracy in need of a haircut. Jones complied.

Coach Skip Palrang had a great influence on the start of Boys Town’s famous sports teams

Just as Flanagan earlier made the school band and choir ambassadors for BT, so he did with football. The same year the movie “Boys Town” was released, the football squad boarded the Challenger super liner at Omaha’s Union Station for a trip west, where they played a benefit game against Black Foxe Military Institute of Los Angeles. The film’s producer, John Considine, Jr., made it happen. Among the 10,000 or so in attendance at Gilmore Stadium were numerous Hollywood stars. Boys Town won, 20-12.

The good turnout seems to have convinced Flanagan to take his football team on the road as a gypsy, bring-on-all-comers sideshow featuring orphans from the world-famous Boys Town. The bigger the stage, the tougher the opponent, the more Flanagan liked it.

He would often wend his way to wherever the football team appeared, posing for photos, making pre-game or halftime on-the-field speeches, and generally getting the Boys Town name in the press. A big banquet, often in his honor, usually preceded or followed the game, giving Flanagan another chance to spread the gospel.

BT alum Ed Novotny of Omaha, who played for Boys Town in the early 1940s, recalls the time Flanagan was on the field during pre-game festivities in New Jersey. Novotny says a press photographer asked to snap a few pictures of the famous priest doing a mock kickoff. Sensing a good photo op, Flanagan obliged. As he lined up for the kick, Novotny turned to an opposing player and said, “He’s in a bad spot” – meaning the photographer crouched in front of the ball, holding a Speed Graphic camera overhead.

BT alum Ed Novotny of Omaha, who played for Boys Town in the early 1940s, recalls the time Flanagan was on the field during pre-game festivities in New Jersey. Novotny says a press photographer asked to snap a few pictures of the famous priest doing a mock kickoff. Sensing a good photo op, Flanagan obliged. As he lined up for the kick, Novotny turned to an opposing player and said, “He’s in a bad spot” – meaning the photographer crouched in front of the ball, holding a Speed Graphic camera overhead.

“What do you mean?” the other player said.

“Father Flanagan can kick. He’ll blast that thing right over the goal post.”

“Really? A priest?”

Novotny will never forget what happened next. “No sooner did I say, ‘Yeah,’ than he kicked that ball and knocked that camera right out of the guy’s hands.”

Novotny recalls Flanagan as an enthusiastic presence on the sideline or in the locker room. The priest stood in the players’ circle to lead pre-game prayers. At basketball games he sat on the end of the bench with players and coaches. He greeted guys by name or with his favorite terms of endearment, “Dear” or “Laddie.”

To compete with the nation’s best, Flanagan hired Maurice “Skip” Palrang, who came to Boys Town after successful stints at Omaha Creighton Prep and Creighton University. Over his 29-year career at Boys Town, he led Cowboy teams to football, basketball and baseball titles. He won National Coach of the Year honors from the Pop Warner Foundation of Philadelphia, Pa., and Nebraska High School coaching plaudits from the Omaha World-Herald.

As athletic director, Palrang oversaw construction of a mammoth field house, modeled after those at Purdue and Michigan State. Its classic brick facade features sculpted panels of Greek-like figures in various athletic poses, stained glass windows and a vast arched metal roof that spans the length of a football field. Great facilities like these helped set BT apart.

Palrang hired coaches to carry BT’s dominance into other sports, but it was best known for football. “It wasn’t like Boys Town would play the weakest teams we could find – we’d play the baddest teams we could find,” said ’50s star halfback “Deacon” Jones. “We knew we played the best teams Skip could get to play. A lot of the players we played against went on to make All-American in college. Some went to the pros. We traveled to play Aquinas in Rochester, N.Y. That was like a Notre Dame prep school. And, whew, they had some tough players.”

Boys Town Bus Travels to Florida for exhibition game

Under Palrang, the Cowboys went 75-33-6 in these intersectional matchups. BT also participated in intersectional basketball and baseball contests, but on a far more limited basis.

Jones said players got “five dollars per trip for eating and fun money.” For some, like him, it was their first time on a train, a big deal for “kids that didn’t have anything,” he added. Seeing the sights was part of the experience – Chicago’s Field Museum, New York’s Rockefeller Center and Radio City Music Hall. But the road trips, which lasted up to three weeks, were not all fun and games. An instructor traveled with the team and made sure they kept up on their schoolwork.

Lessons of another kind came on the few road trips south of the Mason-Dixon Line. “We would go to some areas where they wouldn’t allow the black kids on our team to stay in the same hotel as the whites,” Pfeifer said. “A few times we had to arrange for those kids to stay with some people in the community. It was a terrible blow to Fr. Flanagan. That’s probably why we didn’t play that much in the South.”

Wilburn Hollis was among a black contingent denied access to a hotel. Although from the Jim Crow South, he’d been shielded from the worst of segregation – the same at color-blind Boys Town. “We were buddies, but even more than that we felt like we were brothers and we just lived like that,” said Hollis, a Possum Trot, Miss. native who became a high school All America quarterback at Boys Town and a signal caller for an Iowa University team that won a share of the Big 10 title. “I never heard anything racial.”

“At Boys Town I never thought about ethnicity or race,” said Ken Geddes, who grew up in Florida and went on to play for Nebraska and in the National Football League. “…We were all part of a family.”

Within that family of athletes, Palrang was the unchallenged head of household. “He was about six-four and probably 220 pounds and he was mean as a goat,” Hollis said. “But he was a wonderful coach. He loved the kids, he loved Boys Town….”

Hollis told of an incident involving Flanagan’s successor, Rev. Nicholas Wegner. (Flanagan died in 1948 on a goodwill mission in Berlin, Germany). Like his predecessor, Wegner was a sports booster, but apparently didn’t share Skip Palrang’s competitive philosophy. Once when BT was losing a football game, the priest tried to deliver a halftime pep talk. Wegner advised the team to do their best, Hollis recalls, “and honestly he used that old cliché, ‘It’s not if you win or lose, it’s how you play the game.’ Well, Skip was pretty hot and he said, ‘Bulls__t. We’re going to win this game.’ Monsignor was like, Oh-oh. And we went out and won the game.”

But Palrang’s success was based on more than force of will. Stern but fair, he was known for his precise preparation, a quality that fit his favorite hobby of watch repair. Ex-sportscaster Jack Payne of Omaha recalls Palrang in his field house office “hovered over a well-lighted table…wearing an eye shade, jeweler’s glasses, meticulously at work on a watch.”

An innovator, Palrang used his vast contacts to learn new offensive and defensive schemes from college and professional colleagues, often implementing packages years before anyone else at the prep level. He’d get reels of game or practice film with the latest sets to study. Sought out for his expertise, he often conducted clinics around the country. Pfeifer said that once, at the request of an old buddy, Palrang sent BT quarterback Jimmy Mitchell to Kansas State to help Wildcat signal callers learn the T-formation Skip helped initiate in high school.

The Cowboys often played far from home, so Palrang sent an assistant ahead to scout. Palrang’s protégé, George Pfeifer, inherited the thankless job. In order to see distant teams, he traveled by plane, train, automobile or any available mode of transport. He once flew into Chicago’s Midway Airport on his way to see an opponent that night in Wisconsin. In Chicago he was bumped from the last connecting flight north. With only a few hours until game time and hundreds of miles between him and the stadium, he was stuck. Desperate, he asked, “Is there any other way?” He was directed to a helicopter pad. For $15 and a slight case of nausea, he arrived “just about the time they were kicking off.”

Boys Town graduate Charles “Deacon” Jones competes in the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia, finishing ninth in the 3,000-meter steeplechase. Four years later, he would finish seventh in the same event in the Rome Olympics.

Skip Palrang’s physician son, Art, who played for his father one year at BT, said besides the advantage Palrang got by scouting opponents “the Boys Town kids in those days… were really tough, tough boys. They weren’t very big but they were tough… There weren’t a lot of distractions out there, like girls. He had kind of a captive audience.”

Palrang also had the advantage of working with kids who came out of BT pee-wee, freshman and junior varsity programs imbued with his coaching systems. By the time they made varsity, kids were well-schooled in the Palrang way. It led to potent team chemistry.

Despite offers to leave, Palrang remained loyal to Boys Town. Art Palrang believes this allegiance stemmed from Skip being an orphan himself. “His mother died when he was two and left his father with three boys and three girls,” he said. “He was always sympathetic to the Boys Town kids, although he was typical Irish in that he would not show his emotions.”

Today, Palrang’s accomplishments are commemorated in a big memorial just inside the field house dedicated in his honor. The memorial is next to a long row of display cases reserved for trophies and plaques won by Boys Town coaches, athletes and teams. There are hundreds of items. There’d be more, except Palrang made a habit of giving them away to kids.

By the time Palrang retired in 1972, he was only coaching his main passion, football. Years earlier, he’d entrusted the basketball program to Pfeifer, another coach often described as a “no-nonsense father figure.” Pfeifer’s basketball teams went 202-45 (two state titles), and his track teams (two titles) were always a threat. He recently joined his mentor in the Nebraska High School Sports Hall of Fame.

Like his predecessor, Pfeifer encountered racist attitudes toward his players, as when he started five black players on his state championship basketball teams of 1965 and 1966. One morning after a game, a caller demanded, “Why you playing all them n_____s?”

“Because they’re my five best players,” Pfeifer replied.

Boys Town’s barnstorming era was prompted by publicity and the guaranteed payoff for its football games. But BT was also compelled to travel for another reason. Once it became a winner, it could find only a handful of area schools willing to schedule games.

Despite many attempts, BT was long denied membership in the Omaha Inter-City League, comprised of large Omaha area schools. Pfeifer said Wegner reportedly had to threaten to withdraw funds from local banks to gain admittance. It finally happened when the Inter-City League was disbanded and the new Metropolitan High School Activities Association was created in 1964.

Everyone has a theory about the blacklisting. Speculation ranges from envy over BT’s athletic riches to rumors, denied by BT alums, that it practiced off-season, suited older student-athletes, or recruited prospects. An image of BT suiting up juvenile delinquents, true or not, may have also accounted for schools not wanting to schedule the Cowboys. BT athletic equipment manager and head baseball coach Jim Bayly said that when he was a player at Omaha South, “we were afraid of Boys Town.”

Shane Hankins, quarterback for BT this past season, senses that the “jail” or “criminal” perception still haunts BT. But far from intimidating foes, he said it makes them “want to fight us even harder to prove we’re not tougher.” He concedes BT has some rough players, but points out that the Cowboys win sportsmanship awards.

Even without conference membership, Boys Town had a metro rival. “In the middle ’40s, when Boys Town was really taking off,” Art Palrang said, “Creighton Prep was also in its heyday and they played bitter, bitter battles. Rumor has it the archbishop said, ‘Hey, you guys have got to stop this. We can’t have two Catholic teams fighting each other.’” Adding fuel to the fire was the fact Palrang once coached Prep. There was no one he enjoyed beating more.

Aside from Prep, Palrang said, “Boys Town was obviously cleaning up on everybody and Omaha didn’t want ’em in their league because… Boys Town would have won everything.” By contrast, Prep had long been a conference member. And once let in, BT proved as dominant as feared by soon piling up Metro titles.

Perhaps nothing explains the ostracism better than what one alum called BT being “an island unto itself.” A certain arrogance surely came with all that independence, winning and notoriety. Besides, there was the perception – if not reality – that BT didn’t really need to be in a local athletic league. In fact, cross-country travel was expensive and eventually became cost-prohibitive.

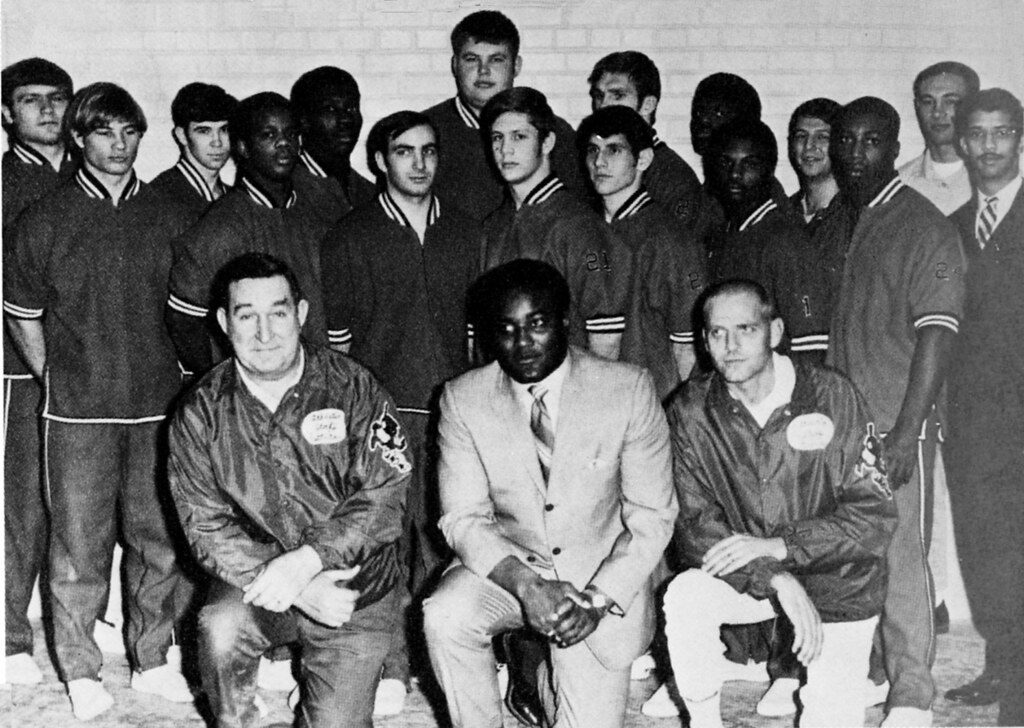

The 1985-1966 Cowboys basketball team wins the school’s second straight state basketball championship.

By the time Boys Town’s reign ended in the mid-1970s, BT had evolved from a place where boys lived in dormitories to a family housing model where residents – girls too – live with teacher parents. Changes in the way BT works with youth lowered the number of residents from a high of about a thousand (elementary and high school combined) to about half that today, and decreased the average stay from six or eight years to about 18 months. The smaller enrollment forced BT to drop from the big school to small school ranks, and the shorter stays gave coaches less time to develop athletes and mold teams. For years, BT athletic prowess declined.

Today’s BT coaches are again turning out winning teams and top athletes, their job complicated by kids who present complex behavioral disorders. BT teams again compete for titles, but in Class C1, not Class A. The football team has its rivals, but a road trip today is an hour by bus, not overnight by train.

Girls and Boys Town (as the institution has been known since 2000) still uses athletics to further its mission of helping at-risk youth develop life skills that prepare them for adulthood. Head football coach Kevin Kush sets a high bar for his players, and makes no exceptions in holding them accountable. By late September 2006, he’d already let a few of his best players go for violating team rules, which brought his varsity squad down to 26. He could have supplemented the varsity by promoting JV players, but he refused, saying, “They haven’t paid the price. I’m not going to change my philosophy. I’m not going to lower my standards. See, these kids have standards lowered for them for their whole lives. We don’t do that. We want our kids to be committed to something and a lot of them have never been committed to anything.”

This past season’s star quarterback, Shane Hankins, said he appreciates that coaches and others care enough to make football special again. “Our goal is to achieve, to shoot for something in our lives some people say is impossible for us to do since we’re here. But we prove them wrong. We want to bring more winning to this campus because before we came here, most of us weren’t recognized as winners.”

All last basketball season, head boys basketball coach Tom Krehbiel relied heavily on an unofficial assistant, the 81-year-old George Pfeifer who, despite health woes, came to practices weekly to distill some of his wisdom to players young enough to be his great-grandchildren. Pfeifer’s championship teams of 1965 and ’66 are still regarded as two of Nebraska’s best high school basketball teams ever.

“I wanted to get him involved in the program,” Krehbiel said of Pfeifer. “I reached out to him. We ate lunch, hit it off and he’s been a big part of our program ever since. I don’t think it’s a coincidence we started winning since then. Coach has been a great mentor to me and just a great resource for us. For our current players he’s a link to success.”

After last year’s team won Boys Town’s first state basketball championship in 40 years, guard Dwaine Wright dedicated the victory to Pfeifer live on Nebraska Educational Television.

Pfeifer said that after a period of adjustment, he and the team forged a strong bond. “When I’d come out there, some of the kids warming up before the game would come over and say, ‘God, we’re glad to see you coach. You feeling alright? We’re going to play hard for you.’ That last night when they accepted the trophy the one kid held it up and said, ‘This is for you, Coach Pfeifer…’ Those are the kind of kids….” Choked with emotion, Pfeifer’s voice trailed off.

The experience brought him full circle to how as a kid he was welcomed and encouraged by Father Flanagan, Skip Palrang and others, and how he did the same for kids as a BT coach, vocational education teacher and middle school principal. “I knew I wanted to be there to help those type of kids,” Pfeifer said of Boys Town students past and present. “You know, they come there with a hole in their heart. Nobody cares about them, nobody encourages them – they just think there’s no way they can make it. We set up goals and objectives. We praise them when they succeed. When a kid comes up to you and says, ‘God, I wish you were my dad’…then you know you made a difference.”

Note: The Boys Town Hall of History features displays and a film that relive some of BT’s glory years in football.

Related Articles

- Valor Christian’s athletic excellence has arrived quickly (denverpost.com)

- Many college football dynasties have roots in strength training (sports.espn.go.com)

- Top 15 Traditions in All of Sports: A Closer Look at the Best of the Best (bleacherreport.com)

- The George Steinbrenner of junior football (theglobeandmail.com)

- Sun Reflection, Revisiting the Omaha Sun’s Pulitzer-Prize Winning Expose on Boys Town (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Ron Stander: One-time Great White Hope still making rounds for friends in need

I did this follow up story on ex-Omaha heavyweight boxer Ron Stander about seven or eight years after the first story I did on him, which you will also find on this blog. In that earlier piece Stander was still fighting some demons, still in the throes of recovery. In the interim, Stander had come to terms with some things in his life and by the time I did this second story he seemed more at peace with himself and his place in the world. Stander was and is a tough dude, but he’s also a big teddy bear of a man with a heart of gold. That’s one thing that’s never changed about him. This story, which originally appeared in the New Horizons, portrays Stander as the good man he is, just a regular guy who helps his friends, including some fellow ex-boxers who have fallen on various hard times. To a man, his buddies love him. It’s heartening to know that Stander is now happily remarried and writing his life story. It should be a helluva read.

Ron Stander: One-time Great White Hope still making rounds for friends in need

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Far from the spotlight he inhabited when he fought for the world heavyweight boxing title 35 years ago, Ron “The Bluffs Butcher” Stander goes about his daily routine these days in relative obscurity. That’s fine with him. He had his moment in the sun. He’d rather be remembered anyway as a good man, a good father and a good friend than as a good fighter.

“Yeah, right, that’s exactly it,” he said. “I just want to be a good person.”

He lives a simple life, both by choice and circumstance. He may be poor in finances, but he’s rich in friends. Despite his own problems, he aids folks less well-off and able than him, often making the rounds to visit old pals, many of whom he knows “from boxing.” Some, like Tony Novak, Gabe Barajas and Art Hernandez, are ex-fighters. Novak and Hernandez sparred with Stander back in the day.

Fred Gagliola coached a young Stander as an amateur Golden Gloves fighter. Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon is an ex-pro wrestler quite popular here. Stander and Vachon know the highs and lows of life inside and outside the ring. Tom Lovgren was the matchmaker for many Stander fights and at one time managed him.

Each man suffers some kind of health impairment or disability. All befriended Stander at one time or another and he’s never forgotten it.

“They all helped me. Now I attempt to give back in some way. I like to help out. They were in my corner and now I’m in their corner,” said Stander, who variously does chores, runs errands and offers companionship for them.

Lovgren is afflicted with multiple sclerosis. The effects of the advanced disease confine him to a wheelchair. When his wife Jeaninne broke a leg last winter she could not get her large husband out of his chair into bed.

“So I called Ronnie and said, ‘Can you come down and help me into bed every night?’ — and he did,” Lovgren said. “He came down at 10:30 every night and put me to bed. I paid him, because he didn’t have to do that. He’s a good friend.”

Not long ago Lovgren took a fall at home, unable to get up by himself or even with an assist from his petite wife. Enter Stander.

“It was about 10 o’clock at night. I was beat, tired. I worked hard that day and I was all out of gas. I’d just had my first beer of the night when Jeaninne called. ‘Can you help out?’ I went down to their place. He was flat on the floor and I had to pick him up…and put him in his chair. It was a tough lift. Boy, he’s getting heavy. Probably weighs 250. Dead weight,” Stander said. “I about didn’t make it. Jeaninne had to get on his side and grab his pants and pull him up. We got him though.”

Stander’s glad to help the man who so much did for him. Lovgren not only got him fights, but was part of the team that readied him for his May 25, 1972 title bout with champ Joe Frazier in a jam-packed Civic Auditorium. Lovgren prodded Stander to get in fighting trim and stay away from late night beer binges.

“He would always get me to do the road work real good,” Stander said. “He’d take me running, count laps. He was a real disciplinarian. But fun, too. I respected him.”

Before he challenged for the championship, Lovgren arranged what Stander called a “steppingstone” match with future contender Earnie Shavers. Considered one of the hardest punchers in the heavyweight division, Shavers’ blows “felt like getting hit by a night stick or a ball bat,” Stander said. “It was like a whip cracking at the end.” After a slow start that saw him get pummeled, he KO’d Shavers in the fifth. Shavers reportedly had to be carried off by his corner.

That became Stander’s signature win. His most notable loss, of course, came in his title bid. After losing to Frazier, Stander sank into a deep depression and his career nose-dived. “I didn’t have any desire,” he said.

Except when Lovgren got him a marquee match against former contender Ken Norton on the undercard of the Muhammad Ali-Jimmy Young bout. Norton won when the fight was stopped in the fifth due to cuts he opened up on Stander, who was prone to bleed, but to this day “The Butcher” feels he would have had a tiring Norton “out of there in another round or two.”

Coulda’, woulda, shoulda’. “You can’t fight destiny” Stander said.

Away from the ring, the fighter admires how Lovgren has never given up in his own battle with MS. Despite the debilitating disease, Lovgren has raised a family, worked, traveled and maintained his passion for sports, especially boxing.

“He’s been an inspiration,” Stander said. “He’s paid his dues.”

The other men Stander helps are inspirations to him, too.

Former world middleweight contender Art Hernandez lost a leg after a freak fall from a roof, but he hasn’t let it stop him from living a life and enjoying his family. “I’ve got all the respect for him, too,” said Stander, who, like Lovgren, considers Hernandez to have been the best fighter, pound-for-pound, to ever come out of Nebraska. As an undersized but much quicker sparring partner, Hernandez used to frustrate Stander in the gym, confounding and evading the lumbering heavyweight. “I couldn’t hit him with a handful of rice,” Stander said.

Stander admires too how “Mad Dog” Vachon has not allowed the mishap that cost him a leg to embitter him.

“’Mad Dog’s’ a good guy,” he said. “He has a great attitude.”

Through “Mad Dog” Stander met an array of pro wrestling legends, such as Andre the Giant. “When I shook his hand it was like grabbing a pillow,” he said.

When Hernandez first got fitted with his prosthesis Stander brought him over to “Mad Dog’s” place so these two old warriors with artificial limbs would know they were not alone. The gesture touched the two men.

“He did me a favor that day,” Hernandez said.

“He’s got a heart of gold,” Vachon said. “He’s a very nice man. A real softee. He’s the kind of guy who would give you the shirt off his back.”

Since suffering a series of strokes Fred Gagliola, the man who helped show Stander the ropes as an amateur, has trouble getting by.

“I was just weeding in his yard the other day,” Stander said one summer morning outside the south downtown home of the man he calls Coach. “He can’t do much. I sweep and mop the floor for him.” “He cuts the grass, he throws out the garbage,” Coach said. “Whatever it takes,” added Stander. “I just try to help him however I can. He was on my side in the Gloves, you know. He backed me, supported me. He did favors, I do favors. He helped me, I try to help him now. So it’s pay back.”

Although he can use the money, Stander doesn’t lend a hand for the “couple bucks” he earns “here and there.” “Other things,” besides money, “make him happy,” Vachon said. Like doing good deeds.

Friends and family are all that are left once the money runs dry and the glory fades. “Mad Dog” and “The Butcher” made names for themselves in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Vachon reigned as an All-Star Wrestling king on cards at the Omaha Civic Auditorium. That’s where Stander enjoyed his greatest ring success, topped by challenging Frazier for “all the marbles” in what may have been the biggest sporting event Omaha’s ever seen.