Archive

Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Don Benning: Man of Steel (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com) as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

Wrestling is a proving ground. In an ultimate test of will and endurance, the wrestler first battles himself and then his opponent until one is left standing with arms raised overhead in victory. In a life filled with mettle-testing experiences both inside and outside athletics, Don Benning has made the sport he became identified with a personal metaphor for grappling with the challenges a proud, strong black man like himself faces in a racially intolerant society.

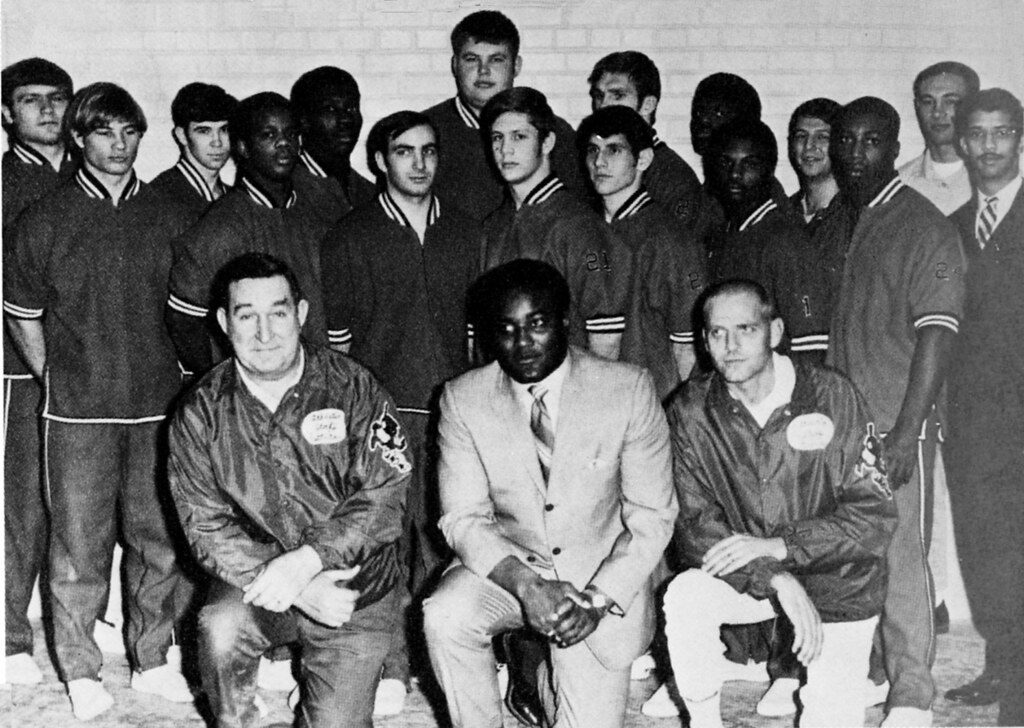

A multi-sport athlete at North High School and then-Omaha University (now UNO), the inscrutable Benning brought the same confidence and discipline he displayed as a competitor on the mat and the field to his short but legendary coaching tenure at UNO and he’s applied those same qualities to his 42-year education career, most of it spent with the Omaha Public Schools. Along the way, this man of iron and integrity, who at 68 is as solid as his bedrock principles, made history.

At UNO, he forged new ground as America’s first black head coach of a major team sport at a mostly white university. He guided his 1969-70 squad to a national NAIA team championship, perhaps the first major team title won by a Nebraska college or university. His indomitable will led a diverse mix of student-athletes to success while his strong character steered them, in the face of racism, to a higher ground.

When, in 1963, UNO president Milo Bail gave the 26-year-old Benning, then a graduate fellow, the chance to he took the reins over the school’s fledgling wrestling program, the rookie coach knew full well he would be closely watched.

“Because of the uniqueness of the situation and the circumstances,” he said, “I knew if I failed I was not going to be judged by being Don Benning, it was going to be because I was African-American.”

Besides serving as head wrestling coach and as an assistant football staffer, he was hired as the school’s first full-time black faculty member, which in itself was enough to shake the rafters at the staid institution.

“Those old stereotypes were out there — Why give African-Americans a chance when they don’t really have the ability to achieve in higher education? I was very aware those pressures were on me,” he said, “and given those challenges I could not perform in an average manner — I had to perform at the highest level to pass all the scrutiny I would be having in a very visible situation.”

Benning’s life prepared him for proving himself and dealing with adversity.

“The fact of the matter is,” he said, “minorities have more difficult roads to travel to achieve the American Dream than the majority in our society. We’ve never experienced a level playing field. It’s always been crooked, up hill, down hill. To progress forward and to reach one’s best you have to know what the barriers or pitfalls are and how to navigate them. That adds to the difficulty of reaping the full benefits of our society but the absolute key is recognizing that and saying, ‘I’m not going to allow that to deter me from getting where I want to get.’ That was already a motivating factor for me from the day I got the job. I knew good enough wasn’t good enough — that I had to be better.”

Shortly after assuming his UNO posts his Pullman Porter father and domestic worker mother died only weeks apart. He dealt with those losses with his usual stoicism. As he likes to say, “Adversity makes you stronger.”

Toughing it out and never giving an inch has been a way of life for Benning since growing up the youngest of five siblings in the poor, working-class 16th and Fort Street area. He said, “Being the only black family in a predominantly white northeast Omaha neighborhood — where kids said nigger this or that or the other — it translated into a lot of fights, and I used to do that daily. In most cases we were friends…but if you said THAT word, well, that just meant we gotta fight.”

Despite their scant formal education, he said his parents taught him “some valuable lessons scholars aren’t able to teach.” Times were hard. Money and possessions, scarce. Then, as Benning began to shine in the classroom and on the field (he starred in football, wrestling and baseball), he saw a way out of the ghetto. Between his work at Kellom Community Center, where he later coached, and his growing academic-athletic success, Benning blossomed.

“It got me more involved, it expanded my horizons and it made me realize there were other things I wanted,” he said.

But even after earning high grades and all-city athletic honors, he still found doors closed to him. In grade school, a teacher informed him the color of his skin was enough to deny him a service club award for academic achievement. Despite his athletic prowess Nebraska and other major colleges spurned him.

At UNO, where he was an oft-injured football player and unbeaten senior wrestler, he languished on the scrubs until “knocking the snot” out of a star gridder in practice, prompting a belated promotion to the varsity. For a road game versus New Mexico A&M he and two black mates had to stay in a blighted area of El Paso, Texas — due to segregation laws in host Las Cruces, NM — while the rest of the squad stayed in plush El Paso quarters. Terming the incident “dehumanizing,” an irate Benning said his coaches “didn’t seem to fight on our behalf while we were asked to give everything for the team and the university.”

Upon earning his secondary education degree from UNO in 1958 he was dismayed to find OPS refusing blacks. He was set to leave for Chicago when Bail surprised him with a graduate fellowship (1959 to 1961). After working at the North Branch YMCA from ‘61 to ‘63, he rejoined UNO full-time. Still, he met racism when whites automatically assumed he was a student or manager, rather than a coach, even though his suit-and-tie and no-nonsense manner should have been dead giveaways. It was all part of being black in America.

To those who know the sanguine, seemingly unflappable Benning, it may be hard to believe he ever wrestled with doubts, but he did.

“I really had to have, and I didn’t know if I had it at that particular time, a maturity level to deal with these issues that belied my chronological age.”

Before being named UNO’s head coach, he’d only been a youth coach and grad assistant. Plus, he felt the enormous symbolic weight attending the historic spot he found himself in.

“You have to understand in the early 1960s, when I was first in these positions, there wasn’t a push nationally for diversity or participation in society,” he said. “The push for change came in 1964 with the Civil Rights Act, when organizations were forced to look at things differently. As conservative a community as Omaha was and still is it made my hiring more unusual. I was on the fast track…

“On the academic side or the athletic side, the bottom line was I had to get the job done. I was walking in water that hadn’t been walked in before. I could not afford not to be successful. Being black and young, there was tremendous pressure…not to mention the fact I needed to win.”

Win his teams did. In eight seasons at the helm Benning’s UNO wrestling teams compiled an 87-24-4 dual mark, including a dominating 55-3-2 record his last four years. Competing at the NAIA level, UNO won one national team title and finished second twice and third once, crowning several individual national champions. But what really set UNO apart is that it more than held its own with bigger schools, once even routing the University of Iowa in its own tournament. Soon, the Indians, as UNO was nicknamed, became known as such a tough draw that big-name programs avoided matching them, less they get embarrassed by the small school.

The real story behind the wrestling dynasty Benning built is that he did it amid the 1960s social revolution and despite meager resources on campus and hostile receptions away from home. Benning used the bad training facilities at UNO and the booing his teams got on the road as motivational points.

His diverse teams reflected the times in that they were comprised, like the ranks of Vietnam War draftees, of poor white, black and Hispanic kids. Most of the white athletes, like Bernie Hospodka, had little or no contact with blacks before joining the squad. The African-American athletes, empowered by the Black Power movement, educated their white teammates to inequality. Along the way, things happened — such as slights and slurs directed at Benning and his black athletes, including a dummy of UNO wrestler Mel Washington hung in effigy in North Carolina — that forged a common bond among this disparate group of men committed to making diversity work in the pressure-cooker arena of competition.

“We went through a lot of difficult times and into a lot of hostile environments together and Don was the perfect guy for the situation,” said Hospodka, the 1970 NAIA titlist at 190 pounds. “He was always controlled, always dignified, always right, but he always got his point across. He’s the most mentally tough person you’d ever want to meet. He’s one of a kind. We’re all grateful we got to wrestle for Don. He pushed us very hard. He made us all better. We would go to war with him anytime.”

Brothers Roy and Mel Washington, winners of five individual national titles, said Benning was a demanding “disciplinarian” whom, Mel said, “made champions not only on the mat but out there in the public eye, too. He was more than a coach, he was a role model, a brother, a father figure.” Curlee Alexander, 115-pound NAIA titlist in 1969 and a wildly successful Omaha prep wrestling coach, said the more naysayers “expected Don to fail, the more determined he was to excel. By his look, you could just tell he meant business. He had that kind of presence about him.”

Away from the mat, the white and black athletes may have gone their separate ways but where wrestling was concerned they were brothers rallying around their perceived identity as outcasts from the poor little school with the black coach.

“It’s tough enough to develop a team to such a high skill level that they win a national championship if you have no other factors in the equation,” Benning said, “but if you have in the equation prejudice and discrimination that you and the team have to face then that makes it even more difficult. But those things turned into a rallying point for the team.

“The white and black athletes came to understand they had more commonalities than differences. It was a sociological lesson for everyone. The key was how to get the athletes to share a common vision and goal. We were able to do that. The athletes that wrestled for me are still friends today. They learned about relationships and what the real important values are in life.”

His wrestlers still have the highest regard for him and what they shared.

“I don’t think I could have done what I did with anyone else,” Hospodka said. “Because of the things we went through together I’m convinced I’m a better human being. There’s a bond there I will never forget.” Mel Washington said, “I can’t tell you how much this man has done for me. I call him the legend.” The late Roy Washington, who changed his name to Dhafir Muhammad, said, “I still call coach for advice.” Alexander credits Benning with keeping him in school and inspiring his own coaching/teaching path.

After establishing himself as a leader Benning was courted by big-time schools to head their wrestling and football programs. Instead, he left the profession in 1971, at age 34, to pursue an educational administration career. Why leave coaching so young? Family and service. At the time he and wife Marcidene had begun a family — today they are parents to five grown children and two grandkids — and when coaching duties caused him to miss a daughter’s birthday, he began having second thoughts about the 24/7 grind athletics demands.

Besides, he said, he was driven to address “the inequities that existed in the school system. I thought I could make a difference in changing policies and perhaps making things better for all students, specifically minority students. My ultimate goal was to be superintendent.”

Working to affect change from within, Benning feels he “changed attitudes” by showing how “excellence could be achieved through diversity.” During his OPS tenure, he operated, just like at Omaha University, “in a fish bowl.” Making his situation precarious was the fact he straddled two worlds — the majority culture that viewed him variously as a token or a threat and the minority culture that saw him as a beacon of hope.

But even among the black community, Benning said, there was a militant segment that distrusted one of their own working for The Man.

“You really weren’t looked upon too kindly if you were viewed as part of the system,” he said. “On the other side of it, working in an overwhelmingly majority white situation presented its own particular set of challenges.”

What got him through it all was his own core faith in himself. “Evidently, some people would say I’m a confident individual. A few might say I’m arrogant. I would say I’m highly confident. I can’t overemphasize the fact you have to have a strong belief in self and you also have to realize that a lot of times a leader has to stand alone. There are issues and problems that set him or her apart from the crowd and you can’t hide from it. You either handle it or you fail and you’re out.”

Benning handled it with such aplomb that he: brought UNO to national prominence, laying the foundation for its four-decade run of excellence on the mat; became a distinguished assistant professor; and built an impressive resume as an OPS administrator, first as assistant principal at Central High School, then as director of the Department of Human-Community Relations and finally as assistant superintendent.

During his 26-year OPS career he spearheaded Omaha’s smooth desegregation plan, formed the nationally recognized Adopt-a-School business partnership and advocated for greater racial equity within the schools through such initiatives as the Minority Intern Program and the Pacesetter Academy, an after school program for at-risk kids. Driving him was the responsibility he felt to himself, and by extension, fellow blacks, to maximize his and others’ abilities.

“I had a vision and a mission for myself and I set about developing a plan so I could reach my goal, and that was basically to be the best I could be. As a coach and educator what I have really enjoyed is helping people grow and reach their potential to be the best they can be. That’s my goal, that’s my mission, and I try to hold to it.”

His OPS career ended prematurely when, in 1997, he retired after being snubbed for the district’s superintendency and being asked by current schools CEO John Mackiel to reapply for the assistant superintendent’s post he’d held since 1979. Benning called it “an affront” to his exemplary record and longtime service.

About his decision to leave OPS, he said, “I could have continued as assistant superintendent, but I chose not to because who I am and what I am is not negotiable.” A critic of neighborhood schools, he did not bend on a practice he deems detrimental to the quality of education for minorities. “I compromised on a lot of things but not on those issues. The thing I’ve tried not to do, and I don’t think I have, is negotiate away my integrity, my beliefs, my values.”

Sticking to his guns has exacted a toll. “I’ve battled against the odds all my life to achieve the successes I have and there’s been some huge prices to pay for those successes.”

Curlee Alexander

His unwavering stances have sometimes made him an unpopular figure. His staunch loyalty to his hometown has meant turning down offers to coach and run school districts elsewhere. His refusal to undermine his principles has found him traveling a hard, bitter, lonely road, but it’s a path whose direction is true to his heart.

“I found out long ago there were things I would do that didn’t please every one and in those types of experiences I had to kind of stand alone or submit. I developed a strong inner being where I somewhat turned inward for strength. I kind of said to myself, I just want to do what I know to be right and if people don’t like it, well, that’s the way it is. I was ready to deal with the consequences. That’s the personality I developed from a very young age.”

Those who’ve worked with Benning see a man of character and conviction. Former OPS superintendent Norbert Schuerman described him as “proud, determined, disciplined, opinionated, committed, confident, political,” adding, “Don kept himself very well informed on major issues and because he was not bashful in expressing his views, he was very helpful in sensitizing others to race relations. His integrity and his standing in the community helped minimize possible major conflicts.”

OPS Program Director Kenneth Butts said, “He’s a very principled man. He’s very demanding. He’s very much about doing what is right rather than what is politically expedient. He cares. He’s all about equity and folks being treated fairly.”

After the flap with OPS Benning left the job on his own terms rather than play the stooge, saying, “The Omaha Public Schools situation was a major disappointment to me…To use a boxing analogy, it staggered me, but it didn’t knock me down and it didn’t knock me out. Having been an athlete and a coach and won and lost a whole lot in my life I would be hypocritical if I let disappointment in life defeat me and to change who I am. I quickly moved on.”

Indeed, the same year he left OPS he joined the faculty at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where he is coordinator of urban education and senior lecturer in educational administration in its Teachers College. In his current position he helps prepare a new generation of educators to deal with the needs of an ever more diverse school and community population.

Even with the progress he’s seen blacks make, he’s acutely aware of how far America has to go in healing its racial divide.

“This still isn’t a color-blind society. I don’t say that bitterly — that’s just a fact of life. But until we resolve the race issue, it will not allow us to be the best we can be as individuals and as a country,” he said.

As his own trailblazing cross-cultural path has proven, the American ideal of epluribus unum — “out of many, one” — can be realized. He’s shown the way.

“As far as being a pioneer, I never set out to be a part of history. I feel very privileged and honored having accomplished things no one else had accomplished. So, I can’t help but feel that maybe I’ve made a difference in some people’s lives and helped foster inclusiveness in our society rather than exclusiveness. Hopefully, I haven’t given up the notion I still can be a positive force in trying to make things better.”

Related Articles

- Coaching diversity slowly rising at FBS schools (thegrio.com)

- University regents approve Nebraska-Omaha’s D-I move (sports.espn.go.com)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Redemption, A Boys Town Grad Tyrice Ellebb Finds His Way

When I met Tyrice Ellebb about a decade ago he was a young man who had turned his life around in a dramatic way through the aid of many caring individuals and institutions, including Boys Town, but he was also reeling from leaving the powerhouse University of Nebraska at Omaha wrestling program, where he achieved much. He had personal matters to attend to that in his mind at least took precedence over collegiate athletics, even though he was a key cog for a team poised to win a national title. He was also a very good football player. He felt bad about the way things worked out but as my story makes clear the people you may have thought he most disappointed were still in his corner. I lost contact with Tryice after the story but I understand he did get things together in his life and I know he’s excelled at indoor professional football. This story originally appeared in the Omaha Weekly, a paper that is no more, and I offer it here as another example of the kind of sports writing I like to do.

Redemption, A Boys Town Grad Finds His Way

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Omaha Weekly

As the No.1-ranked UNO wrestling team enters the stretch-run in its national championship hunt, the man who should be holding down the heavyweight spot for the Mavericks is no where to be seen. Senior Tyrice Ellebb, projected as a strong title contender, left the team this winter after the latest in a series of personal crises sent him reeling. A sweet, soft-spoken goliath who loves to dance, Ellebb was at his best when he bounced around the mat to the beat of whatever song was in his head. Sadly, he has had his last dance in a UNO uniform.

At only 23, the massive Ellebb (he stands 6’3 and his weight hovers around 300 pounds) has weathered a topsy-turvy life that’s found him both on the side of the angels and the devils. Growing up on Chicago’s south side, he ran with the notorious Gangster Disciples. Looking to escape his hometown’s mean streets, he followed four uncles to the former Boys Town, where he won election as mayor. While he flourished in the nurturing Boys Town setting and, later, in the family-like UNO wrestling program, he also made some bad choices along the way, including fathering three children — all out of wedlock. Still, he applied himself in high school and developed into a standout football player and wrestler — winning two state heavyweight championships (pinning all his opponents as a senior).

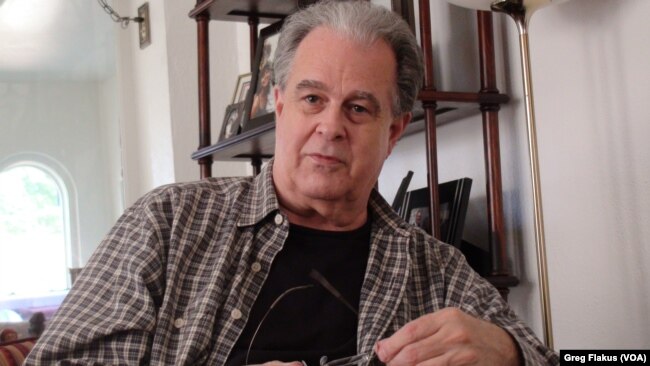

Possessing great size, agility and quickness, he was courted by Nebraska and Kansas State as a walk-on gridiron prospect. When he did not qualify academically he signed with Iowa Central Community College, where he twice garnered junior college All-America honors and earned an associate’s degree. At UNO he fought homesickness, endured the death of a dear aunt and worked with teammates and coaches in managing his complicated life. Although an acknowledged leader on and off the mat, Ellebb’s frequent missed practices and late arrivals were distractions. Allowances were made, but it never seemed enough. “We demand a lot here in our program and it was hard for him to get all that together. We tried to be flexible and to give him some leeway, but you can only do so much,” UNO Head Coach Mike Denney said.

Mike Denney

Despite the distractions, Ellebb proved a force to be reckoned with by winning the North Central Conference heavyweight crown and finishing a solid fourth at last year’s NCAA Division II tournament. Heading into this season he was seen as the linchpin of a dominant UNO squad tabbed as odds-on favorites for the team title. After working so hard and overcoming so much, this was going to be his year. Then, last December, it all came crashing down around him and his dreams of glory vanished. His story can be seen as both an object lesson in overcoming the odds and a cautionary tale of taking on too much-too soon.

To understand just how far he came, one must understand that for the longest time this product of a broken home appeared headed for prison or a violent death — the fate of several friends he hung out with as a youth. Even though his mother, Sharon, was a security officer, she almost found out too late his gangbanging was threatening to destroy him the way it already had one of her brothers. There were street fights, drug dealings, gunshots, threats and reprisals. Through it all, Ellebb avoided incarceration, completed school and remained close to his family.

“I was letting the streets get to me. You always had to worry about looking behind your back. Somebody always wanted to take you out because they wanted your name. It’s just crazy. It got to the point where in my head I felt I needed to kill somebody if people bothered me,” he said.

It took the senseless death of a family friend who was like a favorite uncle for him to rethink the gangster life. “Two rival gangs were involved in something stupid and a gun went off and it instantly killed him. That kind of tore me up real bad. That made me understand I didn’t need to be involved in gangs anymore. I needed to get away before they beat me or before I wouldn’t see my next birthday.”

When his mother found out she was losing him to the streets she promptly saw him off on the next train to Boys Town, where other wayward men in the family had found refuge. “I listened to her and I’m glad I made that choice to come here. I accomplished a lot at Boys Town,” he said. There, he came under the influence of teacher-coach Don Bader, who said, “Tyrice had a lot of issues. He needed a lot of work. But he got on the right track. He’s a great kid.” These days, when Ellebb visits his old stomping grounds in Chicago, he finds little changed. “My friends are still doing the same thing. The only thing different is everyone is older. When I go back there I’m like, ‘God, I’m glad I left there.’ I couldn’t picture myself being that way now. When I tell people, ‘I used to be a thug,’ they say, ‘I couldn’t see you that way.’ And I go, ‘Yeah, I know, I changed. I made myself change.’” UNO’s Denney said despite the baggage Ellebb carries, “he has a lot of good in him.”

Prior to his latest troubles Ellebb’s commitment to wrestling waned at various times, but he always rededicated himself. With the birth of his third child last year, however, his passion lagged. Soon, he fell behind in his classes and was declared academically ineligible the first semester. The only action he saw offered a vivid display of his inner turmoil when, for the only time in his wrestling career, he was disqualified after throwing a punch at an opponent who earlier elbowed him.

According to Ellebb, “When that happened, I said to myself, ‘I can’t do this right now. I need to get my head together.’ Coach Denney told me to work through it. He chose for me not to wrestle the following weekend, but sitting out didn’t help. A lot of stuff was going wrong then. It just started piling up so fast.” The final straw was when his beloved grandmother, Anne, who helped raise him, was stricken with cancer. “She’s the backbone of our family. She keeps us together. She’s the only person I can talk to. She’s the one who makes me keep striving to do right. When I found out about my grandmother being sick, it was more than I could handle.”

Overwhelmed, he retreated into a cocoon. “I was struggling with myself. I just stayed away from everyone. I wasn’t talking to anyone. I felt I was going to have a nervous breakdown.” Finally, on December 15, he left Omaha for Chicago to be with his family. His departure caused him to miss some final exams, resulting in two incompletes. By re-enrolling this semester as a full-time student, he unwittingly used up any remaining eligibility. No matter, Ellebb had already decided he could not continue wrestling. “I felt (quitting) this was probably the best thing for me and for the team because I couldn’t wrestle to my potential if my head and heart wasn’t in it,” he said. His decision has caused him anguish. “I hate that I’m not part of the team now and not out there trying to help them win the national championship. If things didn’t fall out like they did and if I didn’t make my load as heavy it was, I’d probably still be part of it.” Perhaps his biggest regret is abandoning the team without formally giving his coaches or teammates an explanation. “They deserve to hear something,” he acknowledges.

During Ellebb’s tailspin Coach Denney said he tried contacting him but could not reach him. “I made attempts to find out what was happening. I even tried to contact some of the people he hangs with, but I could tell he was drifting away from us. I could sense as early as last summer he was struggling again and I tried to be really positive with him. But we just didn’t seem to be able to create enough positive power to hold him. The negative forces just kind of overwhelmed him.”

In gauging how much Ellebb’s absence hurts, Denney said, “Certainly, we miss him. We miss what he could have contributed. We were counting on him. The Lord blessed him with a lot of talent. We went from a senior who, in my mind, was the frontrunner to win a national championship to a redshirt freshman, (Lance Tolstedt). Losing all the experience Tyrice had and all the work and time we put into him is a huge impact on our team.”

To a man, Ellebb’s former teammates say they feel no bitterness. Instead, there is frustration and empathy. For 125-pounder Mack LaRock, Ellebb’s departure “was a big disappointment because we know how much stronger he made our team, but we also realize all the different problems and situations he has in life. He did let us down, but I can’t say I wouldn’t have done the same thing if I was in his shoes. There’s no really hard feelings. Tyrice made his bed and he has to lie in it now.”

Perhaps the most disappointing thing to those who care about Ellebb is that so much effort went into his athletic success that stopping short now seems a waste. Then there is the fact wrestling provided a sometimes uncertain young man a structure and stability he often could not find elsewhere. “Being part of our team gave him a positive force that could really help him, but when he’s away from that he gets into these other forces that aren’t so positive,” Denney said.

As for himself, Ellebb looks forward to making amends with his former UNO comrades and taking care of business with his family. “I have all my priorities in order now and the main ones are being a part of my children’s lives and finishing school. People tell me I’m a good person. I’m just trying to find that person in me and to do what I’m supposed to be doing in life.”

Related Articles

- Revoked scholarships surprise college athletes (thegrio.com)

- Sherwood Ross: Big-Time College Football Depriving Athletes of an Education (grantlawrence.blogspot.com)

- UNO Wrestling Dynasty Built on a Tide of Social Change (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Thomas Gouttierre: In Search of a Lost Dream, An American’s Afghan Odyssey

Thomas Gouttierre’s work with Afghanistan has drawn praise and criticism, moreso the latter as of late given what’s happened there with the war and some of that nation’s top leadership having been befriended and trained by Gouttierre’s Center for Afghanistan Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. The following profile I did on Gouttierre appeared in 1998, long before U.S. involvement there escalated into full military intervention. Regardless of what’s happened since I wrote the piece, the essential core of the story, which is that of Gouttierre’s magnificent obsession with that country and its people, remains the same.

The story originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com).

Thomas Gouttierre: In Search of a Lost Dream, An American’s Afghan Odyssey

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Like a latter-day Lawrence of Arabia, Omahan Thomas Gouttierre fell under the spell of an enigmatic desert nation as a young man and has been captivated by its Kiplingesque charms ever since.

The enchanting nation is Afghanistan and his rapture with it began while working and living there from 1965 to 1974, first as a Peace Corps volunteer teaching English as a second language, then as a Fulbright fellow and later as executive director of the country’s Fulbright Foundation. His duties included preparing and placing Afghan scholars for graduate studies abroad. During his 10 years there, Gouttierre also coached the Afghan national basketball team. Sharing the adventure with him was his wife and fellow Peace Corps volunteer Marylu. The eldest of the couple’s three sons, Adam, was born there in 1971.

Before his desert sojourn, the Ohio native was a naive, idealistic college graduate with a burning desire to serve his fellow man. When he got his chance half-a-world away, it proved a life transforming experience.

“It’s the place where I kind of grew to a mature person,” he said. “I was there from age 24 to 34 and I learned so much about myself and the rest of the world. It gave me an opportunity to learn well another language, culture and people. I love Afghanistan. It’s people are so admirable. So unique. They have a great sense of humor. They’re very hospitable. They have a great self-assurance and pride.”

But the Afghanistan of his youth is barely recognizable now following 19 years of near uninterrupted carnage resulting from a protracted war with the former Soviet Union and an ongoing civil war. Today, the Muslim state lies in shambles, its institutions in disarray. The bitter irony of it all is that the Afghans themselves have turned the heroic triumph of their victory over the vaunted Soviet military machine into a fratricidal tragedy.

Over the years millions of refugees have fled the country into neighboring Pakistan and Iran or been displaced from their homes and interred in camps across Afghanistan. An entire generation has come to maturity never setting foot in their homeland or never having known peace.

The nation’s downward spiral has left Gouttierre, 57, mourning the loss of the Afghanistan he knew and loved. “In a sense I’ve seen what one might call the end of innocence in Afghanistan,” he said, “because for all its deficiencies, Afghan society – when I was living there – was really a very pleasant place to be. It was a quite stable, secure society. A place where people, despite few resources and trying circumstances, still treated each other with a sense of decency and civility. It was a fantastic country. I loved functioning in that Afghanistan. I really miss that environment. Not to be able to go back to that culture is a real loss.”

Through it all, Gouttierre’s kept intact his ties to the beleaguered Asian nation. In his heart, he’s never really left. The job that took him away in 1974 and that he still holds today – as director of the Center for Afghanistan Studies at the University of Nebraska at Omaha – has kept him in close contact with the country and sent him on fact-finding trips there. He was there only last May, completing a tour of duty as a senior political affairs officer with the United Nations Special Mission to Afghanistan. It was his first trip back since 1993 (before the civil strife began), and what he saw shook him.

“To see the destruction and to learn of the deaths and disappearances of so many friends and associates was very, very sad,” he said from his office on the UNO campus, where he’s also dean of the Office of International Studies and Programs. “Much of the country looks like Berlin and Dresden did after the Second World War, with bombed-out villages and cities. Devastation to the point where almost no family is left unaffected.

“Going back for me was very bittersweet. With every Afghan I met there was such despair about the future of the country. The people are fed up with the war…they so want to return to the way things were. People cried. It was very emotional for me too.”

Everywhere he went he met old friends, who invariably greeted him as “Mr. Tom,” the endearing name he’d earned years before. “In every place I visited I wound up seeing people that I have known for most of my adult life. Individuals that have been here at the University of Nebraska at Omaha – in programs that we’ve sponsored – or people I coached in basketball or people I was instrumental in sending to the U.S. under Fulbright programs or people who taught me Persian and other languages of Afghanistan. So, you know, there’s kind of an extended network there. In fact, it was kind of overwhelming at times.”

Colleague Raheem Yaseer, coordinator of international exchange programs in UNO’s Office of International Studies and Programs, said, “I think he’s received better than any ambassador or any foreign delegation official. He’s in good standing wherever he goes in Afghanistan.”

Yaseer, who supervised Gouttierre in Afghanistan, came to America in 1988 at the urging of Gouttierre, for whom he now works. A political exile, Yaseer is part of a small cohesive Afghan community in Nebraska whose hub is UNO’s Center for Afghanistan Studies. The center, which houses the largest collection of materials on Afghanistan in the Western Hemisphere, provides a link to the Afghans’ shared homeland.

Aside from his fluency in native dialects, his knowledge of Islamic traditions and sensitivity to Afghan culture, Gouttierre also knows many of the principals involved in the current war. It’s the kind of background that gives him instant access and credibility.

“I don’t think there’s any question about that,” Gouttierre said. “The Afghans have a phrase that translates, ‘The first time you meet, you’re friends. The second time you meet, you’re brothers.’ And Afghans really live by that – unless you poison that relationship.”

According to Yaseer, Gouttierre’s “developed a skill for penetrating deep into the culture and traditions of the people and places he visits. He’s able to put everything in a cultural context, which is rare.”

It’s what enables Gouttierre to see the subtle shadings of Afghanistan under its fabled veil of bravado. “When people around the world wonder why the Afghans are still fighting, they don’t realize that a society’s social infrastructure and fabric is very fragile,” said Gouttierre. “They don’t realize what it means to go through a war as devastating as that which the Afghans experienced with the Soviet Union – when well over a million people were killed and much of the traditional resources and strengths of the country were destroyed. When the Soviets left, the Afghans tried to cobble together any kind of government and they were unsuccessful.

“Now they’re trying to put this social-political Humpty-Dumpty back together again, and its just very difficult.”

Under Gouttierre’s leadership the center has been a linchpin in U.S.-U.N. efforts to stabilize and rebuild Afghanistan and has served as a vital conduit between Afghans living inside and outside the country and agencies working on the myriad problems facing it. With nearby Peshawar, Pakistan as a base, the center has operated training and education programs in the embattled country, including a new program training adults in skills needed to work on planned oil and gas pipelines.

Gouttierre himself is a key adviser to the U.S. and world diplomatic community on Afghan matters. He’s served as the American specialist on Afghanistan, Tajikistan and South Asia at meetings of the U.S.-Russian Task Force (Dartmouth Conference) on Regional Conflicts. He’s made presentations on Afghan issues at Congressional hearings and before committees of the British Parliament and the French National Assembly.

And last year he was nominated by the U.S. State Department to serve as the American representative on the U.N. Mission to Afghanistan. “It was quite an honor,” said Gouttierre. “And for me to go back and work among the people again was very appealing and very rewarding.”

The aim of the U.N. mission, whose work continues today, is to engage the combating parties in negotiations toward a just peace settlement. German Norbert Holl, a special representative of the U.N. secretary general to Afghanistan, heads the mission, whose other members are from Russia, Japan, England and France.

On two separate month-long trips to Afghanistan, Gouttierre met with representatives of the various factions and visited strategic sites – all in an effort to help the team assess the political situation. His extensive travels took him the length and breadth of the country and into Pakistan, headquarters for the mission. He talked with people in their homes and offices, he visited bazaars, he viewed dams, irrigation projects and opium fields and traversed deserts and mountains.

Marylu Gouttierre said her husband’s involvement with Afghanistan and commitment to its future stems, in part, from a genuine sense of debt he feels. “He feels a responsibility. It is his second home and those are his people. He’s not only given his heart, but his soul to the country.”

He explains it this way: “Afghanistan has a special place in my professional and personal life and it has had a tremendous impact on my career. It’s been so much an instrument in what I’ve done.”

To fully appreciate his Afghan odyssey, one must review how the once proud, peaceful land he first came to has turned into a despairing, chaotic killing field. The horror began in 1978, when Soviet military forces occupied it to quell uprisings against the puppet socialist regime the USSR had installed in the capital city of Kabul. The Soviets, however, met with stiff resistance from rebel Mujaahideen freedom fighters aligned with various native warlords. Against all odds, the Afghans waged a successful jihad or holy war that eventually ousted the Soviets in 1989, reclaimed their independence and reinforced their image as fierce warriors.

The Afghans, whose history is replete with legendary struggles against invaders, never considered surrender. Said Gouttierre, “The Afghans felt they were going to win from the start. They felt they could stick with it forever. They had a strong belief in their own myth of invincibility…and to everyone’s surprise but their own, they did force the Soviets to leave.”

But the fragile alliance that had held among rival factions during the conflict fell apart amid the instability of the post-war period. “The Soviets left someone in charge who had been their ally in power. That was Najeebullah. His government fell in 1992. That only helped exacerbate things. The cycle of fighting continued as the Afghans who had fought against the Soviet army continued their fight against Najeebullah, who was captured, tried and executed by the Taliban (an Islamic faction) in September of 1996 for his crimes against the Afghans, which were considerable.” Gouttierre knew Najeebullah in very different circumstances before the war, when the future despot was a student of his in a class he taught at a native high school.

After Najeebullah’s fall, a mad scramble for power ensued among the Mujaahideen groups. As Gouttierre explains, “The leaders of these groups had become warlords in their own regions. They kind of got delusions of grandeur about who should be in control of the whole country and they began to struggle against each other.”

In the subsequent fighting, one dominant group emerged – the Taliban, a strict Islamic movement whose forces now command three-quarters of the country, including the capital of Kabul – with all its symbolic and strategic importance. A loose alliance of factions oppose the Taliban.

“As the Taliban (Seekers of Islam) grew in strength, they began intimidating and even fighting some of the minor Mujaahideen commando groups, and to a lot of people’s surprise, they were successful,” said

Gouttierre, whose U.N. assignment included profiling the Taliban. “They are very provincial, very rural – and in their own minds – very traditional Muslims and Afghans. They’re not that philosophically sophisticated in terms of their own religion, but they are very sophisticated in terms of what they understand they want for their society, and they’re able to argue and discourse on it at length without giving any quarter. And they’re willing to go to war over it.

“Each region where they’ve gone, they’ve been aided by the fact that the people living there were disenchanted with those in control. Most of the other groups, unfortunately, lost any credibility they had because of their failure to bring about peace, stability, security and reconstruction. The people were willing to support almost anything that came along.”

The Taliban has drawn wide criticism, internally and externally, for its application of extreme Islamic practices in occupied areas, particularly for placing severe restrictions on women’s education and employment and for imposing harsh penalties on criminals. Gouttierre said while such actions elicit grave concerns from the U.N. and represent major stumbling blocks in the Taliban’s quest for full recognition, the movement has effectively restored order in areas it controls.

“I have to say that in the areas of Afghanistan I traveled to which they control, the Taliban had confiscated all the weapons, removed all the checkpoints people had to pass through, eliminated the extortion that was part of the checkpoints and instilled security and stability,” said Gouttierre. “You could travel anywhere in Kabul without having to be in any way concerned, except for the mines that haven’t been cleared yet.”

Conversely, he said, the Taliban has exhibited brutal politics of intimidation and blatant human rights violations, although other factions have as well. “It’s not a question of who’s good and who’s bad,” he adds. “There’s plenty of blame and credit to be shared on all sides.”

He found the Taliban a compelling bunch. “One of the things I was impressed with is that all of the leaders I met were in some ways victims of the war with the Soviet Union. They all exhibited wounds, and they acquired these wounds heroically carrying out the struggle against the Soviet Union, and I respect them for that. That needs to be taken into account.”

In addition to pushing for a ceasefire between the Taliban and its adversaries, Gouttierre said the U.N. mission consistently makes clear that in order to gain credentialing from the U.N. and support from key institutions like the World Bank, the Taliban must do a better job of protecting basic human rights and ensuring gender equity.

He said the main barrier to reaching a cease fire accord is the Taliban’s nearly unassailable military position, which gives them little reason to make concessions or accept conditions. Another impediment to the peace process is the nation’s rich opium industry, whose interests diverge from those of the U.N. And a major complicating factor is the support being provided the warring factions by competing nations. For example, Pakistan and certain Persian Gulf states are major suppliers of the Taliban, while Iran and Russia are major suppliers of the opposition alliance.

Taliban and opposition leaders did meet together at several U.N. sponsored negotiation sessions. The representatives arrived for the talks accompanied by armed bodyguards, who remained outside during the discussions. The tenor of the meetings surprised Gouttierre. “It was far more cordial than I had anticipated. These men got along remarkably well, in part because they all know each other. That’s not to say there weren’t disagreements. When offended, Afghans can be exceedingly formidable to deal with.”

At Gouttierre’s urging, the mission began holding intimate gatherings at which representatives of the warring parties met informally with U.N. officials over food and drinks and “where translators were not the main medium for communication and where everybody wasn’t on guard all the time.” He hosted several such luncheons and dinners, including ones in Kandahar, Baamiyaan and Kabul. The idea was to create a comfortable mood that encouraged talk and built trust. It worked.

“In diplomatic enterprises often the most effective periods are at the breaks or the receptions, because you’re sometimes able to get people off to the side, where they’re able to say off the record what they can’t say officially. And that’s exactly what happened. Those of us in the U.N. mission got a better sense of who the Taliban are. They’re not irrational. They do have a sense of humor. And they got a better sense of who we are – that we’re not just officials, but that we also have a long-term interest in Afghanistan.”

Gouttierre said the mission has overcome “high skepticism” on the part of Afghans, who recall the U.N. granted Najeebulah asylum despite his being a war criminal. He said the Afghans’ estimation of the mission has moved from distrust to acceptance. And he feels one reason for that is that the present mission has “more clout and recognition than any previous mission to Afghanistan.” Supplying that essential leverage, he said, is the “unstinting support of influential countries like the U.S., France, England, Russia and Japan.”

Despite recent news stories of military inroads made by opposition forces, especially around Kabul, the Taliban remain firmly entrenched. Gouttierre believes that unless a major reversal occurs to change the balance of power, the Taliban will continue calling the shots. If the Taliban eventually consolidate their power and conquer the whole nation, as most observers believe is inevitable, the hope then is that the movement’s leaders will feel more secure in acceding to U.N. pressure.

Gouttierre said that despite the failure to gain a ceasefire thus far, “the fact remains the two sides are meeting with each other, and that’s the first step in any peace process. We don’t have agreements on anything yet, but at least the channels for continuing dialogue have been opened.”

As Gouitterre well knows, the process of binding a nation’s wounds can be frustrating and exhausting. He stays the course though because he wants desperately to recapture the magical Afghanistan that first bewitched him. “I guess one of the things that keeps me at this is that I am ever hopeful that somehow, some way those admirable qualities of Afghan culture which I came to love so much will to some degree be restored. So I keep pursuing that.”

Related Articles

- Afghan president criticizes timeline for U.S. withdrawal (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Market bombing in northern Afghanistan town kills 3 police, 2 civilians, wounds 15 (foxnews.com)

- The Challenge of Training Afghan Troops, Police (cbsnews.com)

- An Old Partnership Takes a New Turn: UNO-Kabul University Renew Ties with Journalism Program (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Afghanistan: U.S. Intelligence Failures Led To Civilian Casualties (huffingtonpost.com)

John Sorensen and his Abbott Sisters Project: One man’s magnificent obsession shines light on extraordinary Nebraska women

The following story was published in the June 2009 New Horizons newspaper. The layout and photographs and article all worked harmoniously together to create a great spread. I post the story here because I think it makes a good read and it introduces you to an interesting personality in the figure of Sorensen and to the remarkable accomplishments of two women I certainly never heard of before working on this story. I think you’ll find, as I did, that Sorensen and the Abbotts make a fitting troika of unbridled passion.

NOTE: John has worked closely over the years with Ann Coyne from the University of Nebraska at Omaha‘s School of Social Work, which was recently renamed the Grace Abbott School of Social Work. Coyne’s a great champion of the work of the Abbott sisters, particularly Grace Abbott, and drew on Sorensen’s work to make the case to university officials to rededicate the school in honor of Grace Abbott. John is also nearing completion on a documentary film that ties together the legacy of the Abbotts and their concern for immigrant women, children, and families and a story quilt project he organized that involved Sudanese girls living in Grand Island telling the stories of their families’ homeland and their new home in America through quilting.

My new story about John Sorensen and his magnificent obsession with the Abbotts is now posted, and in it you can learn more about his now completed documentary, which is being screened this fall.

Grace Abbott

John Sorensen and his Abbott Sisters Project: One man’s magnificent obsession shines light on sxtraordinary Nebraska women

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in the New Horizons

Grace and Edith Abbott may be the most extraordinary Nebraskans you’ve never heard of. John Sorensen aims to change that.

Born and reared on Grand Island’s prairie outskirts in the last quarter of the 19th century, when Indians still roamed the land, the Abbott sisters graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. After teaching in Grand Island they felt called to a secular ministry — the then emerging field of social work in Chicago. They earned advanced degrees at the University of Chicago, where they later taught.

No ivory tower dwellers, the sisters worked with Hull House founder Jane Addams at her famous social settlement. There, amid miserable, overcrowded tenement slums, they set a progressive course for the fair treatment of immigrants, women and children that still has traction today. The sisters’ trailblazing paths followed the lead of their abolitionist father, an early Nebraska politico, and Quaker mother, whose family worked the Underground Railroad. The parents were avid suffragists.

The sisters exerted wide influence: Grace as a federal administrator charged with children and family affairs; Edith as a university educator. They were outspoken advocates-muckrakers-reformers-advisers who helped to set rigorous protocols for social work and to craft public policies and laws protecting marginalized groups. Each attained many firsts for women. Both valued their Nebraska roots.

They were feted in their lifetimes but never gained the fame of Nobel Prize-winner colleague Jane Addams. Working in a neglected arena so long ago resulted in the Abbotts receding to the fringes of history. Grace died in 1939. Edith in 1957. Neither married nor bore children, so no descendent was left to carry the torch.

Enter John Sorensen. While it’s true few outside social work circles know the Abbotts, more will if Sorensen, a Grand Island native, has his way. For 17 years the New York-based writer-director has spearheaded the Abbott Sisters Living Legacy Project. The multi-media effort is the vehicle for his magnificent obsession with shining a light on the women and their significant achievements. Why an expatriate Nebraskan living in Greenwich Village is drawn to a pair of largely forgotten Great Plains women can be answered by the affection and affinity he feels for them.

“I simply love the sisters and this love somehow leads to the work I do,” said Sorensen. “I also admire their work for children and women and immigrants, and I feel a family-like connection and perhaps responsibility to them from sharing a hometown. I could no more turn my back on them, their legacy and their story than I could my own family. That love, that sense of faith is unconquerable.”

Just as the Abbotts were mavericks Sorensen goes against the grain. In an era when women were denied the right to vote, excluded from most jobs and treated as chattel, the Abbotts defied convention as working women and social activists who protested injustice. Sorensen’s not an activist per se but a liberal humanist whose youthful interests in film, music and art made him a misfit in rough-hewn Grand Island. His dogged commitment to perpetuate the Abbott story, often in the face of indifference, underscores a determination to do his own thing.

“I do have a high degree of identification with them,” he said. “I empathize with them. In the same way I choose a play to direct or a script to write I look for a character I identify with or something in their story, like in Grace’s story, that is me. There is some part of her that is me.

“The one term that maybe comes up most frequently in Edith Abbott’s memoir about her sister and her family is this word ‘different.’ She said people just looked at the Abbotts as being different — ‘We weren’t like the people in town.’”

Sorensen’s own family stands apart because his parents, who still live in town, are pillars of the community. He feels keenly the expectations that come with that.

Then there’s the whole sibling parallel. “In Grace’s relationship with Edith, two years her elder, I found many things in common with my relationship with my brother (Jeff), who’s four years older,” said Sorensen. “There’s things the younger sibling learned from the older one, felt challenged by, felt threatened by, but all of those things made them develop in very positive ways.”

Jane Addams

The parental factor strikes home, too. “The way Grace and Edith’s parents nurtured and encouraged and challenged them as kids I certainly felt growing up through my mother,” said Sorensen, whose mom worked for Northwestern Bell and served on the board of G.I.’s Edith Abbott Memorial Library.

“So there were a lot of things I could identify with,” he said, “but I would say the deeper I dug into the Abbott story, into their childhoods, I felt a particular attraction to Grace. I found Grace was a very clever, very kind, but very naughty little girl basically. Edith writes that Grace was constantly in trouble at school. She remembered a moment where the teacher stopped Grace and said, ‘I’m going to have to call your mother, I don’t know what to do with you,’ and Grace immediately responded, ‘But Mother doesn’t know what to do with me either. Sometimes I don’t know what to do with myself.’ It’s funny but also very moving.”

That disconnection resonates with Sorensen, who said he had trouble fitting in because he was “strange.” “Being interested in the arts only made my weirdness seem more weird in that town in that time. School didn’t make any sense to me. I just didn’t like it.” He dropped out of college, never earning a degree. “Me and school don’t get along too well,” he said.

Just as it took Grace awhile to figure out where she belonged, it took Sorensen a long time to find his way.

“Like Grace, I stayed in town well after my high school graduation,” he said. “She stayed until she was 29, and I stayed until I was 26. Those challenging, waiting, searching years are something else that I feel I share with her.”

Then there’s the mission work the Abbotts felt compelled to do and “a kind of destiny” that’s led Sorensen to the Abbott story. The more he invests himself in their tale the more duty-bound he feels to be true to it.

“Again, that is where the love and the faith comes into things,” he said.

With great love comes great responsibility to get it right.

“This becomes the obligation. If you don’t know what you’re talking about and if you’re not willing to pay the price in terms of the study, the research, the heavy lifting,” he said, “it’s not enough that you care about it deeply.”

Despite his lack of formal training Sorensen’s assembled an Abbott Sisters project that cuts across academic disciplines and partners with scholars and educators. An outgrowth is a recently published book he edited with historian Judith Selander, The Grace Abbott Reader (University of Nebraska Press). This anthology of writings by and about Grace is the first in a series of planned Abbott books.

He’s nearing completion of a video documentary, The Quilted Conscience, that explores how the sisters’ concern for immigrants resonates today in places like Grand Island. Sorensen and his cameras followed a group of Sudanese refugee girls there who worked with renowned quilt artist Peggie Hartwell in making a mural story-quilt with images representing the girls’ memories of their homeland and the dreams they hold for their future in America.

“For many of the girls it has been a life changing experience,” said Tracy Morrow, a Grand Island teacher who works with the newcomers. “They feel better about themselves. They have the ability to stand in front of a group and tell their stories. It was very emotional for the girls. They put so much work into it. I feel like John’s doing what the Abbott sisters did by educating the Grand Island community about the Sudanese and educating the Sudanese about Grand Island and America.”

University of Nebraska at Omaha School of Social Work professor Ann Coyne said the sisters “really are a living legacy because we’re now dealing with some of the same problems related to children, maternal health and immigrants they dealt with” in the early 20th century. She said most striking is the parallel between the 1910s through Great Depression period with today, two eras marked by war, economic crisis, immigration debates and childhood-maternal issues. Coyne said reading the sisters’ words today reveals how “very contemporary” their philosophies remain.

Coyne said the Abbotts’ focus on immigrants echoes the yearly trip UNO social work students make to Nicaragua to live in family homes, visit orphanages and clinics and the biyearly trip students make to China. Students also work with refugee families in Nebraska. She said UNO social work graduate student Amy Panning “is living the legacy of Nebraska’s most famous social worker, Grace Abbott,” as the new head of international adoptions for Adoption Links Worldwide.

The storyteller in Sorensen knows a good tale when he sees one. In the Abbotts he’s hit upon a saga of women with backbone, compassion and vision engaged in social action. These early independent feminists from pioneer stock were part of the progressive wave that sought to reform the Industrial Age’s myriad social ills. He tells facets of their story in film, video, radio, stage and print. He makes presentations. He organizes special programs that pay tribute to their rich legacy.

He’s not alone in seeing the Abbotts as historic do-gooders whose work deserves more attention and greater appreciation. Coyne holds Grace Abbott in the highest regard. “She is the outstanding social worker in American history, so the fact she came from Nebraska just makes it better,” said Coyne, who’s convinced Abbott would he a household name today if she’d been a man.. “What I admire her for is that she knew how to work the political system in Washington to make sure laws got passed to ensure children really were protected and weren’t just left to the whims of individuals. She was savvy. She got things done. Children were guaranteed a number of things for their care and concern that weren’t in place before.”

Edith and Grace Abbott

Though Sorensen shares the same hometown as the Abbotts it took years before he learned anything about them. His first inkling came not at home but back East. Growing up he was aware a G.I. park and library bore the Abbott name, but he didn’t know the stories of the women behind these monuments and inscriptions.

His work has helped the town and state rediscover two of their greatest gifts to the world. Working with Grand Island public officials, Sorensen promotes community-school events that celebrate the sisters. All part of a pilgrimage he makes to this place where the sisters were born and are buried. Call it fate or karma, but this less than stellar former student now gives Abbott talks before G.I. schoolchildren, making sure they know what he didn’t at their age.

Morrow said, “We really didn’t know the Abbott sisters before John.”

“What started as an idea to call attention to the Abbotts has really morphed into something much larger and much more powerful and that’s a tribute to John,” said Grand Island Public Schools superintendent Steve Joel. “He’s got people working on this thing that I think are stretched far and wide — not only in Nebraska but New York and other parts of the country.”

None of this was on Sorensen’s mind 23 years ago. Ironically, the young man who “never felt at home in Grand Island” often now returns to share his passion for the Abbotts. He left home in ‘86 to study cinema at the California Institute of the Arts, where he ended up a protege of British director Alexander MacKendrick (The Sweet Smell of Success). By the early ‘90s Sorensen did film and theater work in New York. He assisted producer Lewis Allen and his wife, playwright/screenwriter Jay Presson Allen, on Broadway (Tru) and TV (Hothouse) projects.

Sorensen founded a theater troupe in Manhattan and began making short films. The very first book he wrote, Our Show Houses, got published. It explores the unusual history of Grand Island’s Golden Age movie theaters and proprietors, including an “in” the town’s leading theater owner enjoyed with Hollywood royalty that brought unexpected aspects of Tinsel Town glamour there.

S.N. Wolbach, a prominent G. I. businessman in the Roaring Twenties, was a friend of Universal Pictures head Carl Laemmle from their days as New York merchants. The association led Laemmle to send Universal contract stars such as Barbara Stanwyck to appear in the small Midwest town at Wolbach’s Grand Theatre and a studio crew to shoot a silent newsreel of the town. Laemmle also convinced top movie palace architect John Eberson, who designed the Roxy in New York, to design Wolbach’s Capital Theatre, where Lillian Gish and Louis Calhern performed live on-stage in The Student Prince and Sig Romburg led his orchestra.

When in the course of research Sorensen discovered the Universal footage of G.I. he recut it with snippets from other vintage moving pictures of the town for a new film he entitled Hometown Movies. It’s shown on Nebraska Educational Television.

In doing these projects Sorensen was following an edict from his mentor. “MacKendrick was very big on writing things that you knew about or that were unique to your experience,” he said.

“Around ‘91 or ‘92 I started looking for other things connected to Grand Island. About that time I was working on a project for the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Center for Human Rights in New York,” said Sorensen. “I was editing an anthology of speeches that Bobby Kennedy had given. While doing that I came across a copy of the book A Nation of Immigrants that President (John F.) Kennedy had written and that Bobby Kennedy had written the preface to, and the first name in the bibliography was Edith Abbott. It just kind of threw me. I knew the name, my mother had been on the Edith Abbott library board when I was growing up here.But I had no idea who she was or what she’d done.

“I kind of thought, ‘Oh, that’s interesting, I’ll look up something about those women.’ I went to a library in New York, looked in the Encyclopedia Britannica, and there was no entry for Edith but a very interesting article about Grace, and I thought, ‘Oh, maybe there’s a story here.’ It’s something I do — always keeping my eye out for something unique that hasn’t been covered before.”

His interest peaked, Sorensen continued his quest for Abbott information.

“So I guess the next trip out here to Nebraska I went to the Stuhr Museum (Grand Island) to go through their files on the family. They don’t have a lot but they have some interesting things and among them was a copy of a letter that President Franklin Roosevelt had written to Grace. It was so impressive.”

Sorensen used the letter as a preface to a chapter in The Grace Abbott Reader. Here’s an excerpt from FDR’s 1934 note to Grace Abbott:

“My dear Miss Abbott you have rendered service of inestimable value to the children and mothers and fathers of the country, as well as to the federal and state governments…I have long followed your work and been in hearty accord with the policies and plans which you have developed.”

Coming upon JFK’s reference to one sister and FDR’s adulatory letter to the other proved an “Aha” moment for Sorensen, who also discovered Eleanor Roosevelt was an admirer of Grace Abbott. “At that moment I’m thinking, ‘There’s got to be some story here,’ and at that point I did just enough sniffing around to be certain in my heart there was something worth telling.”

Aptly, Sorensen’s search took him home — to the Abbott library. He later expanded his hunt to searching archives and conducting interviews in his roles as scholar, journalist, detective, documentarian, writer.

“So I was beginning to educate myself. At that point I raised just enough to have like a three-month research project. I went to the University of Chicago.”

He recorded interviews with Chicagoans who worked with or studied under the Abbotts. The more data he gathered the bigger the story grew.

What Sorensen’s discovered about Grace Abbott alone comprises a wealth of achievements that seem too vast for any one person to have completed, especially in such a short lifetime. She died at age 60.

A select list of Grace’s early feats:

•Directed Immigrants Protective League in Chicago

•Wrote “Within the City Gates” weekly articles for the Chicago Evening Post

•Worked with the Women’s Trade Union LeagueTraveled to Central Europe to study emigrant working-living conditions

•Testified before Congress

•Served on Mayor’s Commission on Unemployment in Chicago

•Chaired national Special Committee on Penal and Correctional Institutions

•Served as delegate to Women’s Peace Conference at the Hague

•Organized and chaired Conference of Oppressed Nationalities in nation’s capital

•Named director of Child Labor Division with the U.S. Children’s Bureau in D.C.

•Authored book, The Immigrant and the Community

•At President Woodrow Wilson’s behest served as secretary to the White House Conference on Child Welfare

•Served as consultant to War Labor Policies Board

•Represented Children’s Bureau at conferences in Europe

All this by 1919. Amazingly, she’d only begun her social work career in 1908. Others saw her potential early on and put her in key leadership positions she excelled in. Her phenomenal rise was partly being in the right place at the right time but clearly she was a highly capable doer who impressed those around her.

In 1921 President Warren G. Harding named her Children’s Bureau chief. In her 13- year reign she helped ensure the health, safety, education of the most vulnerable among us. Using every tool at her disposal Abbott spread the word about the pressing needs for child labor reform, improved maternal and childcare, et cetera.

A sample of what Grace did the last 18 years of her life:

•Hosted NBC radio series, produced films, published literature on children’s issues

•Worked for U.S. Constitutional “Children’s Amendment” to regulate child labor

•Administered Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act, the first system of federal aid for social welfare in U.S. history.

•Named president of National Conference of Social Workers

•Helped pen League of Nations Committee “Declaration of the Rights of the Child”

•First woman in U.S. history nominated to Presidential cabinet post

•Awarded National Institute of Social Sciences Gold Medal

•Good Housekeeping named her one of America’s 12 “Most Distinguished Women”

•Appointed adviser to U.S. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins

•Served as managing editor of the Social Service Review

•Contributed to drafting and passage of the Social Security Act

•Served on FDR’s Council on Economic Security

•Chaired U.S. delegation to International Labor Organization Conference in Geneva

•Chaired U.S. delegation to Pan American Conference in Mexico City

•Authored book, The Child and the State

Her noteworthy credits would be longer had ill health not forced her to decline opportunities, such as succeeding Jane Addams as Hull House director. A case of tuberculosis slowed Abbott in the 1920s. After rebounding, her health declined again in the 1930s, by which time she’d resigned from the Children’s Bureau and returned to teach at the University of Chicago, where she rejoined her sister.

Edith Abbott’s accomplishments were numerous, too. After Hull House she studied in London and upon returning to the U.S. helped establish the country’s first university-based school of social work at the University of Chicago in 1920. In 1924 she became dean, making her the first woman dean of a graduate school in an American university. The field work and training she mandated for social workers set professional standards. She launched the journal Social Service Review, serving as managing editor. She advised the U.S. government on federal aid relief during the Depression and the International Office of the League of Nations on problems of women in industry, child labor, immigration, legislation, et cetera.

The sisters remained close siblings and colleagues, often consulting each other.

“I think from an early age, the sisters recognized they were each somehow mysteriously ‘made whole’ by the other — that together they could learn things and experience things and do things impossible for either on her own,” said Sorensen.

An indication of how dear their roots remained was a habit of referring to themselves in interviews as “the Abbott sisters of Nebraska.” Grace was the star but instead of envy Edith expressed admiration for her younger sister. Their shared experience on the prairie, in academia, at Hull House and on the front lines of social work gave each a deep understanding of the other. If anyone could appreciate the mounting challenges Grace faced inside the Beltway it was Edith. No doubt Grace’s many run-ins with political foes, including President Wilson, and her tireless work around the world weakened her already compromised health.

Grace described public service as “the strenuous life” and dismissed critics with, “It is impossible for them to understand that to have had a part in the struggle, to have done what one could, is in itself the reward of effort and the comfort in defeat.” Her militant campaigning for human rights criticized America for neglecting its children and demanded the state care for its homeless, orphaned, sick, poor. Her strong stances elicited strong responses. She was called a socialist. She was an ardent humanitarian, a watchdog for the dispossessed, a voice for the voiceless.

Peggy Hartwell and the Sudanese studentd holding the quilt they created

Edith fought the same battles. Early social work was a perilous job not for the faint of heart. Sorensen said Edith writes about how “’sometimes you didn’t know if your next step was going to plunge you off the edge of a cliff or come down on a bridge to take you across the gap’. Many people literally or figuratively died in that process but what distinguished that generation is that they were like pioneers — they were willing to go and a lot of them were willing to die for it.”

Sorensen’s struck by how Grace used the wartime idiom of the day to describe the hard, uphill road of social work as “battle front service” fraught with “casualties.” She equated social workers with “shock troops.” Apt language for this warrior-protector of the underclass. She came by her fierce convictions via nature and nurture. As Sorensen put it in a recent Omaha address he gave about the Abbotts:

“The combative way was nothing new to Grace. It was the life into which she had been born…she had met and kept company with her family’s many unusual house guests, including suffragist heroines Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone. Before she had started school Grace had already given several years of childhood service to the new women’s suffrage movement of the Midwest, working alongside her remarkable mother and father, who were leading activists…”

Standing up for what’s right can take a heavy toll. By the end of her life, said Sorensen, “Grace was so physically debilitated by her work, it was so physically exhausting and she was so vilified, her body was falling apart.”

He’s mined insights about Grace from extensive notes Edith left behind for an intended but never finished biography of her sister. His first attempt at synthesizing Grace’s story was a three-hour radio series he wrote, My Sister and Comrade, that drew on Edith’s recollections. The series aired on Nebraska Public Radio in the mid-’90s. He then adapted the script for a short performance piece.

He always wanted to do a book and film about the Abbotts but found scant interest for projects whose subjects were obscure figures from the past. To build support he spoke about the Abbotts at schools, libraries and anywhere that would have him. His fledgling Abbott project became whatever he could cobble together.

“I just did whatever I could to keep transforming it and keeping it in people’s faces,” he said. “I could see I was having success in raising awareness — that people were slowly getting to know around the state who these women were. I shifted the focus of the project to what I call the living legacy work — to say, ‘Look, this is not just the study of people from a hundred years ago, this is the study about things that can help us to live better today, especially women, children, immigrants.’

“We started a series of projects, including restoration of the Grace Abbott Park. We raised the money to have properly cleaned up a bronze memorial plaque to Grace that was never completed. We also raised funds to have bronze busts of the sisters cast and placed in the Edith Abbott Library. Very beautiful.

“Around that time, too, through a series of lucky accidents I made a connection to the Nebraska Children and Families Foundation.”

Since 2003, the Lincoln-based Foundation has presented the annual Grace Abbott Award in recognition, said executive director Meg Johnson, of “those who have made a difference” in strengthening the lives of children and families “in the courageous spirit of Grace Abbott.” This year’s recipient is Doug Christensen, emeritus commissioner, Nebraska Department of Education.

The Foundation helped get then-Gov. Mike Johanns to proclaim an annual Abbott Sisters Day. Momentum for the Abbott Sisters Project gained steam. “I think it just legitimized things for people,” Sorensen said. “It got the word out more.”

Along the way Sorensen’s project has garnered funding from the Nebraska Humanities Council and other public and private supporters. Some Grand Islanders hope to capitalize on the Abbott name the way Red Cloud has with Willa Cather.

Like a Johnny Appleseed, Sorensen’s planted the kernels, tilled the ground, and now all things Abbott are sprouting. The Dreams and Memories story-quilt is touring the state until a permanent home is found. Sorensen hopes The Quilted Conscience documentary airs statewide, even nationally, on public television. The University of Nebraska Press is planning a sequel to the Abbott Reader with the 2010 publication of Edith Abbott’s memoir, A Sister’s Memories. Children of the Old Frontier, a book about the Abbott sisters with input from G.I. 4th graders, is part of the new Great Peoples of Nebraska children’s book series by the Press.