Archive

Rosenblatt-College World Series

When the last College World Series was played at Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha the special relationship that that event and venue share, including all the CWS history that’s been made there, got plenty of attention via press reports, fan blogs and forums, books, and films. I wrote my own opus about Rosenblatt and I am posting it now to join all the tributes and memorials pouring in for that most Americana of sports championships and settings.

Much has changed since I wrote the piece and it was published in The Reader (www.thereadercom), like the decision to retire the city owned facility and to replace it next season with a new downtown stadium. Rosenblatt was razed and the property developed by the adjacent Henry Doorly Zoo. A mini replica park was included in the design as a way to memorialize the stadium and its 60 years of hosting the College World Series, an enduring marriage of event and venue unlike any other for a major championship.

If nothing else, my dusted off story, which I call A Rosenblatt Tribute, may give you an added perspective on this slice of baseball culture and history. In this same post I am also sharing a few more of the CWS and Rosenblatt stories I have done over the years, though I still need to put one up called The Boys of Summer.

UPDATE: The summer of 2011 finds Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, Neb. now an empty shell and ghost of a ballpark, its parts being cannibalized and sold off, while the new home of the College World Series, TD Ameritrade Park, is a resounding hit with fans and media.

Eleven years ago or so I wrote this story about Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, the home of the College World Series. As I write this intro, the CWS is a day away from starting play in 2010, the last year the event will be played at the stadium that’s hosted NCCA Division Imen’s baseball championship for 60 years. Rosenblatt is being razed in early 2011, when the series will move into a new downtown stadium now under construction. Rosenblatt has become the symbol for the series because of all the history bound up in it and the special relationship residents and fans have with it and with the blue collar neighborhood surrounding it. My story appeared in The Reader (www.thereader,com).

©Omaha World-Herald

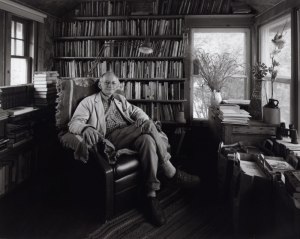

When Rosenblatt was Municipal Stadium. At the first game, from left: Steve Rosenblatt; Rex Barney; Bob Hall, owner of the Omaha Cardinals; Duce Belford, Brooklyn Dodgers scout and Creighton athletic director; Richie Ashburn, a native of Tilden, Neb.; Johnny Rosenblatt; and Johnny Hopp of Hastings, Neb.

A Rosenblatt Tribute

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

It’s baseball season again, and The Boys of Summer are haunting diamonds across the land to play this quintessentially American game. One rooted in the past, yet forever new. As a fan put it recently, “With baseball, it’s the same thing all over again, but it isn’t. Do you know what I mean?”

Yes. There’s a timelessness about baseball’s unhurried rhythm, classic symmetry and simple charm. The game is steeped in rules and rituals almost unchanged since the turn of the century. It’s an expression of the American character: both immutable and enigmatic.

Within baseball’s rigid standards, idiosyncrasy blooms. A contest is decided when 27 outs are recorded, but getting there can involve limitless innings, hours, plays. Stadiums may appear uniform, but each has its own personality — with distinctive wind patterns, sight lines, nooks and crannies.

Look in any American town and you’ll find a ballpark with deep ties to the sport and its barnstorming, sandlot origins. A shrine, if you will, for serious fans who savor old-time values and traditions. The real thing. Such a place is as near as Omaha’s Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium, the site the past 49 years of the annual College World Series.

The city and the stadium have become synonymous with the NCAA Division I national collegiate baseball championship. No other single location has hosted a major NCAA tournament for so long. More than 4 million fans have attended the event in Omaha since 1950.

The 1998 CWS is scheduled May 29-June 6.

In what has been a troubled era for organized ball, Rosenblatt reaffirms what is good about the game. There, far away from the distraction of major league free-agency squabbles, the threat of player/umpire strikes, and the posturing of superstars, baseball, in its purest form, takes center stage. Hungry players still hustle and display enthusiasm without making a show of it. Sportsmanship still abounds. Booing is almost never heard during the CWS. Fights are practically taboo.

The action unwinds with leisurely grace. The “friendly confines” offer the down-home appeal of a state fair. Where else but Omaha can the PA announcer ask fans to, “scooch-in a hair more,” and be obliged?

Undoubtedly, the series has been the stadium’s anchor and catalyst. In recent years, thanks in part to ESPN-CBS television coverage, the CWS has become a hugely popular event, regularly setting single game and series attendance records. The undeniable appeal, besides the determination of the players, is the chance to glimpse the game’s upcoming stars. Fans at Rosenblatt have seen scores of future big league greats perform in the tourney, including Mike Schmidt, Dave Winfield, Fred Lynn, Paul Molitor, Jimmy Key, Roger Clemens, Will Clark, Rafael Palmeiro, Albert Belle, Barry Bonds and Barry Larkin.

The stadium on the hill turns 50 this year. As large as the CWS looms in its history, it is just one part of an impressive baseball lineage. For example, Rosenblatt co-hosted the Japan-USA Collegiate Baseball Championship Series in the ‘70s and ‘80s, an event that fostered goodwill by matching all-star collegians from each country.

Countless high school and college games have been contested between its lines and still are on occasion.

Pro baseball has played a key role in the stadium’s history as well.

Negro League clubs passed through in the early years. The legendary Satchel Paige pitched there for the Kansas City Monarchs. Major league teams played exhibitions at Rosenblatt in the ‘50s and ‘60s. St. Louis Cardinal Hall of Famer Stan Musial “killed one” during an exhibition contest.

For all but eight of its 50 years Rosenblatt has hosted a minor league franchise. The Cardinals and Dodgers once based farm clubs there. Native son Hall of Famer Bob Gibson got his start with the Omaha Cardinals in ‘57. Since ‘69 Rosenblatt’s been home to the Class AAA Omaha Royals, the top farm team of the parent Kansas City Royals. More than 7 million fans have attended Omaha Royals home games. George Brett, Frank White and Willie Wilson apprenticed at the ballpark.

With its rich baseball heritage, Rosenblatt has the imprint of nostalgia all over it. Anyone who’s seen a game there has a favorite memory. The CWS has provided many. For Steve Rosenblatt, whose late father, Johnny, led the drive to construct the stadium that now bears his name, the early years hold special meaning. “The first two years of the series another boy and I had the privilege of being the bat boys. We did all the games. That was a great thrill because it was the beginning of the series, and to see how it’s grown today is incredible. They draw more people today in one session than they drew for the entire series in its first year or two.”

For Jack Payne, the series’ PA announcer since ‘64, “the dominant event took place just a couple years ago when Warren Morris’ two-run homer in the bottom of the ninth won the championship for LSU in ‘96. He hit a slider over the right field wall into the bleachers. That was dramatic. Paul Carey of Stanford unloaded a grand slam into the same bleacher area back in ‘87 to spark Stanford’s run to the title.”

Payne, a veteran sports broadcaster who began covering the Rosenblatt beat in ‘51, added, “There’s been some great coaching duels out there. Dick Siebert at Minnesota and Rod Dedeaux at USC had a great rivalry. They played chess games out there. As far as players, Dave Winfield was probably the greatest athlete I ever saw in the series. He pitched. He played outfield. He did it all.”

Terry Forsberg, the former Omaha city events manager under whose watch Rosenblatt was revamped, said, “Part of the appeal of the series is to see a young Dave Winfield or Roger Clemens. Players like that just stick out, and you know they’re going to go somewhere.” For Forsberg, the Creighton Bluejays’ Cinderella-run in the ‘91 CWS stands out. “That was a real thrill, particularly when they won a couple games. You couldn’t ask for anything more.”

The Creighton-Wichita State game that series, a breathtaking but ultimately heartbreaking 3-2 loss in 12 innings, is considered an all-time classic. Creighton’s CWS appearance, the first and only by an in-state school, ignited the Omaha crowd. Scott Sorenson, a right-handed pitcher on that Bluejay club, will never forget the electric atmosphere. “It was absolutely amazing to be on a hometown team in an event like that and to have an entire city pulling for you,” he said. “I played in a lot of ballparks across the nation, but I never saw anything like I did at Rosenblatt Stadium. I still get that tingling feeling whenever I’m back there.”

A game that’s always mentioned is the ‘73 USC comeback over Minnesota. The Gophers’ Winfield was overpowering on the mound that night, striking out 15 and hurling a shutout into the ninth with his team ahead 7-0. But a spent Winfield was chased from the mound and the Trojans completed a storybook eight-run last inning rally to win 8-7.

Poignant moments abound as well. Like the ‘64 ceremony renaming the former Municipal Stadium for Johnny Rosenblatt in recognition of his efforts to get the stadium built and bring the CWS to Omaha. A popular ex-mayor, Rosenblatt was forced to resign from office after developing Parkinson’s disease and already suffered from its effects at the rededication. He died in ‘79. Another emotional moment came in ‘94 when cancer-ridden Arizona State coach Jim Brock died only 10 days after making his final CWS appearance. “That got to me,” Payne said.

Like many others, Payne feels the stadium and the tourney are made for each other, “It’s always been a tremendous place to have a tournament like this, and fortunately there was room to grow. I don’t think you could have picked a finer facility at a better location, centrally located like it is, than Rosenblatt. It’s up high. The field’s big. The stadium’s spacious. It’s just gorgeous. And the people have just kept coming.”

Due to its storied link with the CWS, the stadium’s become the unofficial home of collegiate baseball. So much so that CWS boosters like Steve Rosenblatt and legendary ex-USC coach Rod Dedeaux, would like to see a college baseball/CWS Hall of Fame established there.

Baseball is, in fact, why the stadium was built. The lack of a suitable ballpark sparked the formation of a citizens committee in ‘44 that pushed for the stadium’s construction. The committee was a latter-day version of the recently disbanded Sokol Commission that led the drive for a new convention center-arena.

With a goal of putting the issue to a citywide vote, committee members campaigned hard for the stadium at public meetings and in smoke-filled back rooms. Backers got their wish when, in ‘45, voters approved by a 3 to 1 margin a $480,000 bond issue to finance the project.

Unlike the controversy surrounding the site for a convention center-arena today, the 40-acre tract chosen for the stadium was widely endorsed. The weed-strewn hill overlooking Riverview Park (the Henry Doorly Zoo today) was located in a relatively undeveloped area and lay unused itself except as prime rabbit hunting territory. Streetcars ran nearby, just as trolleys may in the near future. The site was also dirt cheap. The property had been purchased by the city a few years earlier for $17 at a tax foreclosure sale. Back taxes on the land were soon retired.

Dogged by high bids, rising costs and material delays, the stadium was finished in ‘48 only after design features were scaled back and a second bond issue passed. The final cost exceeded $1 million.

Baseball launched the stadium at its October 17, 1948 inaugural when a group of all-stars, featuring native Nebraskan big leaguers, beat a local Storz Brewery team 11-3 before a packed house of 10,000 fans.

Baseball has continued to be the main drawing card. The growth of the CWS prompted the stadium’s renovation and expansion, which began in earnest in the early ‘90s and is ongoing today.

Rosenblatt is at once a throwback to a bygone era — with its steel-girdered grandstand and concrete concourse — and a testament to New Age theme park design with its Royal Blue molded facade, interlaced metal truss, fancy press box and luxury View Club. The theme park analogy is accentuated by its close proximity to the popular Henry Doorly Zoo.

Some have suggested the new bigness and brashness have stolen the simple charm from the place.

“Maybe some of that charm’s gone now,” Forsberg said, “but we had to accommodate more people as the CWS got popular. But we still play on real grass under the stars. The setting is still absolutely beautiful. You can still look out over the fences and see green trees and see what mid-America is all about.”

Payne agrees. “I don’t think it’s taken away from any of the atmosphere or ambience,” he said. “If anything, I think it’s perpetuated it. The Grand Old Lady, as I call it, has weathered many a historical moment. She’s withstood the battle of time. And then in the ‘90s she got a facelift, so she’s paid her dues in 50 years. Very much so.”

Perched atop a hill overlooking the Missouri River and the tree-lined zoo, Rosenblatt hearkens back to baseball’s and, by extension, America’s idealized past. It reminds us of our own youthful romps in wide open spaces. Even with the stadium expansion, anywhere you sit gives you the sense you can reach out and touch its field of dreams.

NCAA officials, who’ve practically drawn the blueprint for the new look Rosenblatt, know they have a gem here.

“I think part of the reason why the College World Series will, in 1999, celebrate its 50th year in Omaha is because of the stadium we play in, and the fact that it is a state-of-the-art facility,” said Jim Wright, NCAA director of statistics and media coordinator for the CWS the past 20 years.

Wright believes there is a casual quality that distinguishes the event.

“Almost without exception writers coming to this event really do become taken with the city, with the stadium and with the laidback way this championship unfolds,” he said. “It has a little bit different feel to it, and certainly part of that is because we’re in Omaha, which has a lot of the big city advantages without having too many of the disadvantages.”

For Dedeaux, who led his Trojans to 10 national titles and still travels each year from his home in Southern California to attend the series, the marriage of the stadium-city-event makes for a one-of-a-kind experience.

“I love the feeling of it. The intimacy. Whenever I’m there I think of all the ball games, but also the fans and the people associated with the tournament, and the real hospitable feeling they’ve always had. I think it’s touched the lives of a lot of people,” he said.

Fans have their own take on what makes baseball and Rosenblatt such a good fit. Among the tribes of fans who throw tailgate parties in the stadium’s south lot is Harold Webster, an executive with an Omaha temporary employment firm. While he concedes the renovation is “nice,” he notes, “The city didn’t have to make any improvements for me. I was here when it wasn’t so nice. I just love being at the ballpark. I’m here for the game.” Not the frills, he might have added.

For Webster and fans like him, baseball’s a perennial rite of summer.

“To me, it’s the greatest thing in the world. I don’t buy season tickets to anything else — just baseball.”

Mark Eveloff, an associate judge in Council Bluffs, comes with his family. He said, “We always have fun because we sit in a large group of people we all know. You get to see a lot of your friends at the game and you get to see some good baseball. I’ve been coming to games here since I was a kid in the late ‘50s, when the Omaha Cardinals played. And from then to now, it’s come a long way. Every year, it looks better.”

Ginny Tworek is another fan for life. “I’ve been coming out here since I was eight-years old,” the Baby Boomer said. “My dad used to drop me and my two older brothers off at the ballpark. I just fell in love with the game. It’s a relaxing atmosphere.”

There is a Zen quality to baseball. With its sweet meandering pace you sometimes swear things are moving in slow motion. It provides an antidote to the hectic pace outside.

Baseball isn’t the whole story at Rosenblatt. Through the ‘70s it hosted high school (as Creighton Prep’s home field), collegiate (UNO) and pro football (Omaha Mustang and NFL exhibition) games as well as pro wrestling cards, boxing matches and soccer contests. Concerts filled the bill too, including major shows by the Beach Boys in ‘64 and ‘79. But that’s not all. It accomodated everything from the Ringling Brothers Circus to tractor pulls to political rallies to revival meetings. More recently, Fourth of July fireworks displays have been staged there.

Except for the annual fireworks show, however, the city now reserves the park for none but its one true calling, baseball, as a means of protecting its multimillion dollar investment.

“We made a commitment to the Omaha Royals and to the College World Series and the NCAA that the stadium would be maintained at a major league level. The new field is fairly sensitive. We don’t want to hurt the integrity of the field, so we made the decision to just play baseball there,” Omaha public events manager Larry Lahaie said.

A new $700,000 field was installed in 1991-92, complete with drainage and irrigation systems. Maintaining the field requires a groundskeeping crew whose size rivals that of some major league clubs.

Omaha’s desire to keep the CWS has made the stadium a priority.

As the series began drawing consistently large crowds in the ‘80s, the stadium experienced severe growing pains. Parking was at a premium. Traffic snarls drew loud complaints. To cope with overflow crowds, the city placed fans on the field’s cinder warning track. The growing media corps suffered inside a hot, cramped, outdated press box. With the arrival of national TV coverage in the ‘80s, the NCAA began fielding bids from other cities wanting to host the CWS.

By the late ‘80s Omaha faced a decision — improve Rosenblatt or lose the CWS. There was also the question of whether the city would retain the Royals. In ‘90 the club’s then owner, the late Chicago business magnate Irving “Gus” Cherry, was shopping the franchise around. There was no guarantee a buyer would be found locally, or, if one was, whether the franchise would stay. To the rescue came an unlikely troika of Union Pacific Railroad, billionaire investor Warren Buffett and Peter Kiewit Son’s, Inc. chairman Walter Scott, Jr., who together purchased the Royals in 1991.

Urged on by local CWS organizers, such as Jack Diesing Sr. and Jr., and emboldened by the Royals’ new ownership, the city anteed-up and started pouring money into Rosenblatt to rehab it according to NCAA specifications. The city has financed the improvements through private donations and from revenue derived from a $2 hotel-motel occupancy tax enacted in ‘91.

The makeover has transformed what was a quaint but antiquated facility into a modern baseball palace. By the time the latest work (to the player clubhouses, public restrooms and south pavilion) is completed next year, more than $20 million will have been spent on improvements.

The stadium itself is now an attraction. The retro exterior is highlighted by an Erector Set-style center truss whose interlocking, cantilevered steel beams, girders and columns jig-jag five-stories high. Then there’s the huge mock baseball mounted on one wall, the decorative blue-white skirt around the facade, the slick script lettering welcoming you there and the fancy View Club perched atop the right-field stands. The coup de grace is the spacious thatched-roof press box spanning the truss.

Rosenblatt today is a chic symbol of stability and progress in the blue collar south Omaha neighborhood it occupies. It is also a hub of activity that energizes the area. On game days lawn picnics proceed outside homes along 13th Street and tailgate parties unwind in the RV and minivan-choked lots. The aroma of grilled sausage, bratwurst and roasted peanuts fills the air. A line invariably forms at the nearby Zesto’s, an eatery famous for its quick comfort food.

There’s a carnival atmosphere inside the stadium. The scoreboard above the left-field stands is like a giant arcade game with its flashing lights, blaring horns, dizzying video displays and fireworks. Music cascades over the crowd — from prerecorded cuts of Queen’s “We Will Rock You” and the Village People’s “YMCA” to organist Lambert Bartak’s live renditions of “Sioux City Sue” and “Spanish Eyes.” Casey the Mascot dances atop the dugouts. Vendors hawk an assortment of food, drink and souvenirs. Freshly-scrubbed ushers guide you to your seat.

The addition that’s most altered the stadium is the sleek, shiny, glass-enclosed View Club. It boasts a bar, a restaurant, a south deck, a baseball memorabilia collection, cozy chairs and, naturally, a great catbird’s seat for watching the game from any of its three tiered-seating levels. But you won’t catch serious fans there very long. The hermetically-sealed, sound-proof interior sucks the life right out of the game, leaving you a remote voyeur. Removed from the din of the crowd, the ballyhoo of the scoreboard, the enticing scent of fresh air and the sound of a ball connecting with leather, wood or aluminum, you’re cut-off from the visceral current running through the grandstand. You miss its goosebump thrills.

“That’s the bad thing about it,” Tworek said. “You can’t hear the crack of the bat. You don’t pay as close attention to the game there.”

Even with all the bells and whistles, baseball still remains the main attraction. The refurbished Rosenblatt has seen CWS crowds go through the roof, reaching an all-time single series high of 203,000 last year. The Royals, bolstered by more aggressive marketing, have drawn 400,000-plus fans every year but one since ‘92. Fans have come regardless of the won-loss record. The top single-season attendance of 447,079 came in ‘94, when the club finished eight games under .500 and in 6th place.

Why? Fans come for the game’s inherent elegance, grace and drama. To see a well-turned double play, a masterful pitching performance or a majestic home run. For the chance of snaring a foul ball. For the traditional playing of the national anthem and throwing out of the first pitch. For singing along to you-know-what during the seventh inning stretch.

They come too for the kick-back conviviality of the park, where getting a tan, watching the sun set or making new friends is part of the bargain. There is a communal spirit to the game and its parks. Larry Hook, a retired firefighter, counts Tworek among his “baseball family,” a group of fans he and his grandson Nick have gotten acquainted with at the Blatt. “It’s become a regular meeting place for us guys and gals,” he said. “We talk a little baseball and watch a little baseball.

Once the game’s over everybody goes their separate ways and we say, ‘See ya next home stand.’

The season’s end brings withdrawal pains. “About the first couple months, I’m lost,” Hook said. “There’s nothing to look forward to.” Except the start of next season.

As dusk fell at Rosenblatt one recent night, Charles and Stephanie Martinez, a father and daughter from Omaha, shared their baseball credo with a visitor to their sanctuary above the third-base dugout. “I can never remember not loving baseball,” said Charles, a retired cop. “I enjoy the competition, the players and the company of the people I’m surrounded by.”

Serious fans like these stay until the final out. “Because anything can happen,” Stephanie said. “I like it l because it’s just so relaxed sitting out on a summer day. There’s such an ease to it. Part of it’s also the friends you make at the ballpark. It doesn’t matter where you go — if you sit down with another baseball fan, you can be friends in an instant.”

That familiar welcoming feeling may be baseball’s essential appeal. Coming to the ballpark, any ballpark, is like a homecoming. Its sense of reunion and renewal, palpable. Rosenblatt only accentuates that feeling. Like a family inheritance, baseball is passed from one generation to the next. It gets in your blood. So, take me out to the ball game, take me out to the crowd…

Related Articles

- Rosenblatt Stadium will never be forgotten (mlb.mlb.com)

- New CWS stadium gets good reviews (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Burke gets Rosenblatt scoreboard – Omaha.com (theprideofnebraska.blogspot.com)

- Rosenblatt Stadium memories will live on (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

____________________________________________________________________

Rosenblatt is a magical name in Omaha because of the popular mayor who belonged to it, the late Johnny Rosenblatt, who in his day was quite a ballplayer, and because of the municipal stadium whose construction he speerheaded. That stadium was named after him and became home to the College World Series. The subject of this story is his son Steve Rosenblatt, who inherited his father’s love for the game and followed the old man into politics. Fabled Rosenblatt Stadium is no more, replaced by TD Ameritrade Park as host of the CWS. The stadium, the series, and his honor the mayor are more than just tangential memories to Steve, they are lifeblood and legacy.

Steve Rosenblatt, A Legacy of Community Service, Political Ambition and Baseball Adoration

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Jewish Press

Legacy plays a big part in Steve Rosenblatt’s life.

The Omaha native and his wife, the former Ann Hermen, live in Scottsdale, Ariz.

His late father, Johnny Rosenblatt, became an Omaha icon: first as a top amateur baseball player; than as a sponsor of youth athletic teams through the Roberts Dairy company he managed; and finally as a popular Omaha city councilman and mayor. The elder Rosenblatt, who served as mayor from 1954 to 1961, led efforts to build the south Omaha stadium that became the city’s home to professional baseball and to the College World Series.

The city he loved paid tribute to one of its greatest boosters when Omaha Municipal Stadium was renamed Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium in 1964. The venue and the name have become synonymous with the NCAA college baseball championship played continuously at the stadium since 1950.

In a classic case of the apple not falling far from the tree, Steve Rosenblatt was a ballplayer in his own right and served on the Omaha Chamber of Commerce Sports Commission and the Omaha Royals Advisory Board. He followed his father’s footsteps into politics as well, serving two terms on the city council and three terms on the Douglas County Board of Commissioners.

The stadium that’s forever associated with his father played a key role in Steve’s early life. He was a bat boy for the inaugural Omaha Cardinals game played there, a duty he performed the first years the CWS took up residence. He regrets that the facility so closely tied to his family will be razed after the 2010 CWS in line with the planned construction of a new downtown palace slated to host the Series beginning in 2011. But the pragmatic Rosenblatt knows the decision is driven by the bottom line, which trumps nostalgia every time.

Sports and politics are inheritances for Rosenblatt, who is an only child. Just as his father used sports and charisma to forge a political career, the son used his own passion for athletics and way with people to become a player on the local political scene and to find success as an entrepreneur.

Bearing a name that has such major import in Omaha could have been an issue for Rosenblatt, but he didn’t let it be.

“You can take that and make it a burden,” Rosenblatt said, “or you can take it and have it be an asset, and I wished to take that route.”

Comparisons between he and his father were inevitable. “That’s fine, because we weren’t the same. First of all, he was a better ballplayer than me,” he said with his dry wit. “I was a better golfer than he was. Basketball might have been a toss-up, except he played college basketball — I didn’t.”

Growing up, Rosenblatt couldn’t help but notice what made his father a strong mayor and the sacrifices that job entailed.

“I was aware obviously of it and I learned as time went on how he operated and how he did things. Of course it was intriguing. He was a people-person who had an ability to communicate and to have relationships with his constituency and to make the tough decisions and still maintain a tremendous popularity. He had what I would call a broad-based support. He was well liked all over the community and one of the things that contributed to that — and it was what also helped me — was the background he had in athletics. That benefited him as I think it benefited me.

“He was well known as an athlete long before he was well known as a public official and his abilities as an athlete helped to project him into places.”

Rosenblatt said his father epitomized the “It” factor politicos possess. “All the people you see serve in the public sector as elected officials have in my opinion an attribute that goes beyond the norm,” he said, “in that they have the ability to speak and to be received in a fashion that projects themselves as leaders.”

Being an accessible mayor means never really having any down time.

“What was difficult about it was the fact you learned early on there’s a price to be paid as well,” Rosenblatt said, “because obviously with my dad doing what he did he was not going to be with you doing the things you might like to be doing all the time. He had public obligations to take care of as an elected official.”

The level of commitment required to be an effective, responsible public servant was not enough to dissuade Rosenblatt from seeking a seat on the city council and later on the county board. Even with the cachet of his name, his strong base in the business community and a groundswell of support to make a mayoral bid he never seriously considered running for that office. The same for a Congressional seat.

“I really was never interested in it. It was not aspiring to me. I’m as much a people- person as my dad was but at the same time I’m much more private. You cannot in my opinion be an elected official at that level and be as private as I would have liked to be. I want to do the job I was elected to do and when the day is over I want to go to the golf course, be with my family, watch a ballgame. You can’t do that in certain areas because you’ve given up that right and that time by your election to a particular office.”

He said it all comes with the territory.

“Make no mistake about it, when a person is elected to office, even at the city level, the county level, there’s a sacrifice to be made,” he said. “People may not realize it at the time they do get in but they will find out. I found out and I knew how much I wanted to give and how much I didn’t.

“People thought I should have run for mayor. The thing that used to scare me about that thought was I might get elected. Then I’d have to go do it and, you see, I knew too much about what a mayor had to give up and to do to be successful. I could have done it. I think I could have done a good job at it but it was not appealing to me because my (golf) handicap would have gone up.”

He never discussed with his father prospects for a public life nor went to him for political advice.

“Not really,” he said. “I first got elected in ‘73 and he was stricken with Parkinson’s disease in the latter part of the ‘50s, so he was really not able, but he didn’t have to because I learned from him when he was healthy, vigorous and in office, so I’d already got the lessons.”

Even though he never planned for it, Rosenblatt said he always assumed he would gravitate to public service.

“Well, I’d always thought that as a son of a former mayor and as somebody who had learned that life that perhaps some day I might get involved. I knew how to operate, so to speak. Actually, the way it happened is former MayorEugene Leahy said to me one day, ‘Steve, you need to run for the city council — we need to get some new blood in there.’ I guess he kind of triggered the desire.”

At the time he declared his candidacy in 1972 Rosenblatt was a salesman with Sterling Distributing Company, an alcoholic beverage distributor. He’d done some college work at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Only his mind was more on baseball than higher education.

“I was only interested in athletics and still am to this day as a matter of fact. I really did not have the kind of plan that I would hope my kids would have. I was not academically a good student but I think you could say I was more attuned to the practicalities of life. You might say I was street smart…”

A three-year varsity letter-winner at Omaha Central, he tried to play ball at UNL, he said, “but academically I wasn’t taking care of business and physically I was too young to have an opportunity to be successful.”

While school was hardly a home run, his experience trying to cobble together a college baseball career given him priceless insights. He also gained much from his friendship with two coaching legends — Eddie Sutton and the late Rod Dedeaux.

“I’m fortunate to have been very close to two of the greatest coaches in the history of sports.”

Rosenblatt got to know Sutton when the then-Creighton University head basketball coach and his family moved across the street from Steve and his folks. The families remain close to this day. He got to know Dedeaux when the University of Southern California head baseball coach led his powerhouse clubs at the CWS.

“If I’d have known then what I learned from Rod I would have had a chance to have been a better baseball player,” he said, “but at the time I didn’t have that coaching-mentoring.”

The ability to evaluate talent and to weigh options has made Rosenblatt a kind of scout and adviser for promising young athletes, especially Jewish athletes.

“I’m helping kids to try to get situated within athletics. I had a young Jewish kid and his father from Scottsdale, Ariz. go to Omaha to try to help him get set up collegiately. I’m making calls to some baseball people trying to help a young Jewish kid in Omaha who’s a good ballplayer. People call me. People know that I kind of understand. I try to offer guidance to both the parents and the youngsters as to what could be in their best interests. That, to me, is fun.”

Rosenblatt said it’s not an accident he’s drawn to strong, charismatic men like his father. After losing Johnny in 1979 Rosenblatt drew even closer to Dedeaux.

Rosenblatt said it’s not an accident he’s drawn to strong, charismatic men like his father. After losing Johnny in 1979 Rosenblatt drew even closer to Dedeaux.“He also was a people-person and a great communicator,” Rosenblatt said of Dedeaux. “He learned the baseball business from one of the smartest men in the history of the game, a fella named Casey Stengel. That was his mentor. The two games he played in the major leagues Casey Stengel was the manager.”

By the time Rosenblatt owned his own business — a sales and distribution outfit for corrugated package containers better known as boxes — Dedeaux and he were like father and son. They were also business associates.

“He was not only a good friend but one of my biggest customers. He had a trucking company with warehousing and distribution divisions. Multiple operations. It was really big. Make no mistake, he was a baseball person, but he was also a phenomenon in the world of business.”

Rosenblatt parlayed his background in athletics by serving on the Chamber’s Sports Commission, which had a similar agenda as today’s Omaha Sports Commission.

“It was a matter of trying to do the things that make Omaha an attraction for new athletic environments,” he said.

He described his work on the Omaha Royals Advisory Board as “an opportunity for the Royals management to hear from people that are looking at the franchise from perhaps a different standpoint.” He’s still tight with the Royals today. “The general manager of the Royals, Martie Cordaro, is a good friend. I meet with him literally every time I go back to Omaha to talk about what they’re doing and how we can help them be successful.”

Those enduring ties to the Royals keep Rosenblatt informed on the Triple AAA club’s uneasy status in town. Principal owner Alan Stein is in ongoing negotiations with the Omaha Sports Commission and the Metropolitan Entertainment Convention Authority that will determine if the Royals strike a deal to play in the new downtown stadium or go play ball somewhere else. La Vista and Sarpy County are among the Royals’ in-state suitors and Stein indicates out state communities are courting the team as well. Like any good businessman, he’s playing the field.

“Well, I think he has to have that attitude,” Rosenblatt said. “I’ve met with Alan and Martie. I know what they’re thinking is. I’ve offered them my opinion of the situation. It will be interesting to see what develops.”

Steve’s personal connection to Rosenblatt Stadium and to the pro and college baseball tenants that have occupied it rather uneasily in recent years have put him in a Solomon-like position. He loves the CWS and how it’s grown to become a huge event garnering national media coverage. His long association with the Series and his deep affection for the figures who made it special give him a unique perspective. He knows players, coaches, local CWS organizers and NCAA officials.

He sat in on negotiations between the city and the NCAA as a city councilman. “The city was a cooperative partner with the private sector in the production, basically, of the College World Series,” he said. He played a similar oversight role as a county board member.

On the other hand he appreciates what the Royals offer the community and the compromises they’ve made to placate the city and the NCAA and the proverbial 900-pound gorilla that is the CWS. Just as he still talks with Royals officials, he bends the ear of NCAA officials, acting as a kind of intermediary between the two.

It all came to a head when the political hot potato of the new stadium proposed by Mayor Mike Fahey, and subsequently approved by the city council, sealed the fate of Rosenblatt Stadium. The new downtown stadium is being built expressly for the NCAA and the CWS. If the Royals do play there they’d be the ugly step-child who has to accept the leftovers from the favorite son.

Rosenblatt equates a Royals move from Omaha a loss.

“Well, I would because the original concept of the stadium that has Johnny’s name on it was not initially for the College World Series, it was for professional baseball,” he said, “Because of what has transpired with the emergence of the College World Series, it’s now created what I would refer to as an unfriendly situation for professional baseball. There’s no other professional baseball team in America that has a competitor in town called the College World Series. So it’s awkward.”

Even though he now takes an indirect role in such matters, he’s keeping a wary eye on the downtown stadium project, whose estimated $140 million price tag he considers overly optimistic. He predicts it will end up costing $175-$200 million once all the dust settles.

Like many Omahans he’s concerned that if the Royals don’t play at the new stadium and no minor league franchise is secured in their place, the venue will sit empty 50 weeks a year and not be the economic catalyst or anchor for NoDo it’s intended to be. This longtime proponent of a CWS hall of fame said the stadium would be an apt home for it and an Omaha sports hall of fame.

A CWS hall would acknowledge those who’ve excelled as players or coaches or been responsible for the Series’ success. While he doesn’t feel that venue would be much of a year-round draw he sees an Omaha sports museum as a turnstyle magnet “because so many great athletes have come out of Omaha. That would be very interesting, and if you could incorporate the two, that’s a helluva an idea.”

He also has a vested interest in seeing his father’s name live on in the new stadium.

“In my opinion that would be wise and appropriate given the lengthy association that that name has had with college and professional baseball in Omaha. Hopefully the powers that be will have his name connected in some way,” he said.

The stakes are rarely as high as they are with the stadium issue but he makes a practice of using sports as an ice breaker with people.

“Almost everything I’ve done business-wise, athletics has been a tool of taking care of business. My involvement in athletics is an invitation. If I happen to be calling on new customers and if they’re knowledgeable in athletics, then I’m going to get their business, because I can talk it. If they’re interested in the opera and the theater, I’m in trouble. So athletics is a great tool in communicating.”

Athletics and business were not his only finishing schools for a political life. He gained valuable leadership experience as a Nebraska Air National Guardsman and as chairman of the Midlands Chapter of the Multiple Sclerosis Society.

“That was a very rewarding opportunity,” he said. “Hopefully we did some good there. I had learned, of course, with my dad being afflicted with Parkinson’s and my mother being afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis how devastating that can be. Being associated with the Multiple Sclerosis Society gave me an opportunity to contribute and to try to help people…”

Community service motivated his entry into politics.

“You try to get elected in my opinion to help people who perhaps don’t have the ability to help themselves,” he said, “because everybody needs help. Having the ability to collectively help people is the thing that gives you the most pleasure.”

His political life has taught him some lessons. One is to be “leery” of any candidate who makes promises. “The fact of the matter is there’s very little individually they can do because it takes a collective effort to get something done,” he said. Any rhetoric about reducing taxes is just that. “That’s folly,” he said. “They’ll be lucky if they don’t have to raise taxes.”

His action on some issues elicits satisfaction all these years later. One involved the Orpheum Theatre. Omaha’s then-mayor, Ed Zorinsky, wanted it razed. Rosenblatt, a fellow Jew and key ally, went against Zorinsky to side with preservationists who wanted it restored. The conflict came down to a close city council vote.

“The Orpheum Theatre would not be around today if not for Steve Rosenblatt,” he said. “I felt an obligation to the people of the city of Omaha to ensure that it remained for the use down the road. I was the swing vote on that. If that vote goes the other way it’s gone.”

A controversial decision on his council-county board watch was demolishing Jobbers Canyon to make way for the downtown ConAgra campus. “It was an emotional issue,” he said. “I don’t make decisions based on much emotion. I try to make them based on what I think is right.” He said the project “was an absolute must because we as a community could not afford for ConAgra to go to Lincoln or somewhere out in the suburbs — one of the possibilities at the time. It needed to be downtown to be the initial thrust for the redevelopment of that area.”

He encouraged then-mayor Bernie Simon to have the city match a financial commitment the county was making for the project. The city did. He said, “One of the things I had going for me was having been on the city council I retained a great deal of working relationships with people at city hall. The ability to transcend the workings of city and county government was helpful on a variety of projects.”

He credits ex-mayors P.J. Morgan and Hal Daub with driving forward Omaha’s growth by continuing city-county cooperation and public-private sector synergy. Under current Mayor Mike Fahey Omaha’s makeover has been “phenomenal.”

If Rosenblatt and his wife have their way, they’ll eventually live in Omaha half the year. The Rosenblatt name could once again be center stage in the political arena.

Related articles

- Carole Woods Harris Makes a Habit of Breaking Barriers for Black Women in Business and Politics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Omaha Legends: Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce Business Hall of Fame Inductees Cut Across a Wide Swath of Endeavors (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Linda Lovgren’s Sterling Career Earns Her Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce Business Hall of Fame Induction (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Garry Gernandt’s Unexpected Swing Vote Wins Approval of Equal Employment Protection for LGBTs in Omaha; A Lifetime Serving Diverse Constituents Led Him to ‘We’re All in the Human Race’ Decision (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Outward Bound Omaha Uses Experiential Education to Challenge and Inspire Youth (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the Archives: Peony Park Not Just an Amusement Playground, But a Multi-Use Events Facility (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

____________________________________________________________________

The College World Series underway in Omaha is a major NCAA athletic championship that attracts legions of fans from all over America and grabs gobs of national media attention. With this being the last series played at the event’s home these past 60 years, Rosenblatt Stadium, there’s been more fan and media interest than ever before, although a spate of rain storms actually hurt attendance at the start of this year’s series. Inclement weather or not, the series is a great big love-in with its own Fan Fest. But it didn’t used to be this way. Indeed, for the first three decades of the event, it was a rather small, obscure championship that garnered little notice outside the schools participating. Omaha cultivated the event when few others wanted or cared about it, and all that nurturing has resulted in practically a permanent hold on the event, which has strong support from the corporate community, from the City of Omaha, from service clubs, and from the local hospitality industry. Two key players in securing and growing the series have been a father and son, the late Jack Diesing Sr. and Jack Diesing Jr., and they are the focus of this short story that recently appeared in a special CWS edition of The Reader (www.thereader.com) called The Daily Dugout. I have another story on this site from the Dugout — it features Greg Pivovar, one of the colorful characters who can be found at the series.

The Two Jacks of the College World Series

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

In 1967 the late Jack Diesing Sr. founded College World Series Inc. as the local nonprofit organizing committee for the NCAA Division I men’s national collegiate baseball championship. He led efforts that turned a small, struggling event into a major national brand for Omaha.

When son Jack Diesing Jr. succeeded him as president, the young namesake continued building the brand as Jack Sr. stayed on as chairman.

While the CSW is not a business, it’s a growing enterprise annually generating an estimated $40-plus million for the local economy. More than 300,000 fans attend and millions more watch courtesy ESPN.

Papa Diesing was around to see all that growth, only passing away this past March at age 92. Jack Jr. said his father, who saw the event’s potential when few others did, never ceased being amazed “by how it kept getting bigger and better. The phrase he always said is, ‘This just flabbergasts me.'”

His father inherited a dog back in 1963. Jack Sr. was a J. L. Brandeis & Sons Department Store executive. His boss, Ed Pettis, chaired the CWS. The event lost money nine of its first 14 years here. When Pettis died, Jack Sr. was asked to take over. He refused at first. No wonder. The CWS was rinky-dink. Nothing about it promised great things ahead. The crowds were miniscule. The interest weak. But under his aegis an economically sustainable framework was put in place.

What’s become a gold standard event had an unlikely person guiding it.

“When my father got involved with the College World Series he had never attended a baseball game in his life. He didn’t really want to do it but basically he agreed to do it because it was the right thing to do for the city of Omaha,” said Jack Jr. “Over a period of time he developed a love affair with not only what it meant for the fans but what it meant for the city and what it meant for the kids playing in it. He always was looking to do whatever we could do here to make the event better for the kids playing the games and the fans attending the games and for the community. And the rest is history.”

The son’s affinity for the series started early and by the time the patriarch was ready to pass the torch, Jack Jr. was ready.

“I certainly grew up behind the scenes. I can’t say he was purposely grooming me into anything. It’s just that I was exposed to the College World Series ever since I moved back into town in 1975. I’d go to the games, I was involved in sports in school and still was an avid sports follower after I got back.”

Diesing said the same sense of civic duty and love of community that motivated his father motivates him.

He still marvels at his father’s foresight.

“One of the things people credited him for was having tremendous vision about how to set up the infrastructure and make sure we had an organization moving forward that would stand the test of time. And he thought it would make sense to carry on a tradition with his son following him, and that was another thing he was right about.”

His father not only stabilized the CWS but set the stage for its prominence by partnering with the city and the local business community to placate the NCAA by investing millions in Rosenblatt Stadium improvements to create a showcase event for TV.

College baseball coaching legend Bobo Brayton admired how Jack Sr. nurtured the CWS. “I think he was the single person that really kept the world series there in Omaha. I went to a lot of meetings with Jack, I know how he worked. First, he’d feed everybody good, give them a few belts, and then start working on ‘em. He was fantastic, just outstanding. It’s too bad we lost him…but, of course, Jack Jr. is doing a good job too.”

As intrinsic as Rosenbatt’s been to the CWS, Jack Jr. said his father knew it was time for a change: “He could see and did see the needs and the benefits to move into the future. Certainly, I’m the first person to understand the nostalgia, the history, the ambience surrounding Rosenblatt. It’s going to be different down at the new stadium, and it’s just a matter of everybody figuring out a way to embrace the different.”

Diesing has no doubt the public-private partnership his father fostered will continue over the next 25 years that Omaha’s secured the series for and well beyond. He’s glad to carry the legacy of a man, a city and an event made for each other.

Related Articles

- Rosenblatt Stadium memories will live on (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- College World Series: The 10 Greatest CWS Legends Omaha Has Ever Seen (bleacherreport.com)

- College World Series is Omaha’s party central (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- 1st game at new Omaha ballpark sells out in hours (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- The One That Got Away Is Still a Yankees Fan (nytimes.com)

UPDATE: Greg Pivovar’s Stadium View Sports Cards store was left high and dry when Rosenblatt Stadium was closed and the College World Series moved downtown to TD Ameritrade Park, but he does have a presence near the new site courtesy a tent set-up. My story below appeared on the eve of the 201o CWS, as Pivovar, whose shop stood directly across the street from Rosenblatt, prepped for his last dance with the old stadium.

As the College World Series enters the stretch run of the 2010 championship, I offer this story as a slice-of-life capsule of the local color that can be found in and around the event and its festival-like atmosphere. The subject is Greg Pivovar, who runs a sports memorabilia shop called Stadium View Sports Cards, across from Omaha‘s Rosenblatt Stadium, the venue where the CWS has been played for 60 years. This is the stadium’s last at-bat, so to speak, as it’s scheduled to be torn down next year, when the event moves to the new downtown TD Ameritrade Park. The ‘Blatt’s last hurrah is inspiring all manner of nostalgic farewells. Pivovar will be sad to see it go too, but he’s not the sentimental sort. In fact, he’s the cynical antidote to the otherwise perpetually cheery facade the city, the NCAA, and College World Series Inc. like to spin about the series, an event that Omaha has catered to to such an extent that there’s a fair amount of skepticism and animosity out there. Pivovar loves the series and the business it brings him, and he loves serving in the unofficial role of CWS ambassador for visitors from out of state, but he’s not Pollyannish about the event or the powers-that-be who run it. He just kind of says it like it is. His blog, stadiumview.wordpress.com, is a hoot for the way he skewers sacred cows.

I have posted another CWS story about a father and son legacy tied to the event.

Greg Pivovar, owner of the Stadium View shop, poses in his store in Omaha, Neb., Thursday, May 27, 2010. Pivovar is a one-man welcoming committee for College World Series fans. The Omaha attorney greets every (legal age) customer with a free can of beer and nudges them toward the barbecue, brats or, when LSU is in town, seafood jambalaya.(AP Photo/Nati Harnik) — AP

The Little People‘s Ambassador at the College World Series

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Stadium View Sports Cards proprietor Greg Pivovar makes a colorful ambassador for the College World Series with his Hawaiian shirt, khaki shorts and blue-streak S’oud Omaha patter. This bona fide character champions “the little people who built” the CWS.

Enter his sports memorabilia shop across from Rosenblatt and his coarse, cranky, world-weary sarcasm greets you, his barbs delivered with a stiff drink in one hand and a cell phone in the other. He talks like he writes on his stadiumview.wordpress.com blog.

“A lot of it is funny and cynical, but a lot of it is from my heart,” he said..

His shop’s a popular way stop for CWS fans craving authentic Omaha. He’s dispensed free beer since opening the joint 19 years ago. “It’s meant as a gesture of friendship and welcome, not as, Hey, you want to stand around and get drunk here? Part of the ritual,” he said. In 2006 he “took a cheap ass plea” on a ticket scalping charge he claims was bogus. He said the company he keeps is what got him in trouble.

“I have a bunch of scalpers who hang around here,” he said. “They’re friends of mine. I like them, they’re an interesting breed of human being.”

The arrest made headlines. A recent AP story that went viral called him a one-man CWS welcoming committee. Ryan McGee profiled him in the book The Road to Omaha.

“Famous…infamous, I’ve been both,” said Pivovar.

His uncensored ways hardly conform to the Norman Rockwell image the NCAA prefers.

Pivovar, who also serves homemade barbecue and enchiladas during the CWS, and cooks up a mean jambalaya whenever LSU makes it, feels he contributes to a “festival atmosphere.” Vendor and hospitality tents dot the blue collar neighborhood, where enterprising residents make a sweet profit charging for parking spots and refreshments.

The NCAA’s tried distancing the CWS from the commercial, party vibe. A clean zone will be easier to enforce with the move to TD Ameritrade Park next year.

“Piv” likes a good time but acknowledges all “the temporary bars” can be “a negative,” adding, “There’s a few too many people coming down here just to get drunk, and that’s not the idea. That sounds hypocritical coming from a guy who’s given 40,000 beers away, but it really isn’t. Most of my beers are given away one, maybe two at a time.”

The Creighton University Law School grad and former Sarpy County public defender has a private practice he puts on hold for the series. This being Rosenblatt’s last year, he’s stocked extra beer for the record hordes expected to say adieu to the stadium.

His own ties to Rosenblatt go back to childhood. His collecting began with baseball cards, sports magazines, game programs, signed balls. He got serious after college, traveling to buy and sell wares. Eventually, he said, “my collection was pretty much overrunning my home. I’m a hoarder. I needed a place to store my hobby.” Thus, the store was born, although he insists: “It’s not a business, it’s never been a business. I don’t make any money at this, I never have. It’s kind of like a museum.”

Most of his million or so cards, he said, “are just firewood.”

What business he does do largely happens during the CWS. Even then he said I “barely pay the bills.” He doesn’t know what he’ll do after the ‘Blatt’s gone and the series moves downtown. “I’d love to carry my hobby down there but…If somebody comes and shits a couple hundred thousand dollars on my face it might happen, but other than that…”

If he closes shop, he’s unsure what will become of his stuff.

“I don’t even want to think about it. I suppose I could throw it all on e-bay and get a mere pittance for it. That’s the way that works. So much of it has zero to such a narrow market, and I knew that going in. It’s not like I was having any allusions of getting rich from this.”

He’s pissed about the “Blatt’s demise and suspects the new site will usher in a sterile, elitist era.

“I’m a conspiracy theorist. What this is all about is developing that north area (NoDo) and wanting to give the zoo what they need. The bastards are taking my ballpark. Like I end a lot of my blogs, I’ve got so many days until my world’s over. It’s kind of like writing your own obituary.”

At least he has his health. He’s cancer-free after a bout with cancer.

The “Save Rosenblatt” t-shirts he carried have been replaced with ones reading: “To Hell with Rosenblatt, Save Stadium View.”

Stadium View is at 3702 So. 13th St.

Related Articles

- College World Series Is Moving On (nytimes.com)

- College World Series is Omaha’s party central (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Rosenblatt Stadium memories will live on (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- Vermont couple ties knot during CWS rain delay (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- 1st game at new Omaha ballpark sells out in hours (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

A Rosenblatt Tribute

UPDATE: The summer of 2011 finds Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, Neb. now an empty shell and ghost of a ballpark, its parts being cannibalized and sold off, while the new home of the College World Series, TD Ameritrade Park, is a resounding hit with fans and media.

Eleven years ago or so I wrote this story about Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, the home of the College World Series. As I write this intro, the CWS is a day away from starting play in 2010, the last year the event will be played at the stadium that’s hosted NCCA Division I men’s baseball championship for 60 years. Rosenblatt is being razed in early 2011, when the series will move into a new downtown stadium now under construction. Rosenblatt has become the symbol for the series because of all the history bound up in it and the special relationship residents and fans have with it and with the blue collar neighborhood surrounding it. My story appeared in The Reader (www.thereader,com).

©Omaha World-Herald

When Rosenblatt was Municipal Stadium. At the first game, from left: Steve Rosenblatt; Rex Barney; Bob Hall, owner of the Omaha Cardinals; Duce Belford, Brooklyn Dodgers scout and Creighton athletic director; Richie Ashburn, a native of Tilden, Neb.; Johnny Rosenblatt; and Johnny Hopp of Hastings, Neb.

A Rosenblatt Tribute

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

It’s baseball season again, and The Boys of Summer are haunting diamonds across the land to play this quintessentially American game. One rooted in the past, yet forever new. As a fan put it recently, “With baseball, it’s the same thing all over again, but it isn’t. Do you know what I mean?”

Yes. There’s a timelessness about baseball’s unhurried rhythm, classic symmetry and simple charm. The game is steeped in rules and rituals almost unchanged since the turn of the century. It’s an expression of the American character: both immutable and enigmatic.

Within baseball’s rigid standards, idiosyncrasy blooms. A contest is decided when 27 outs are recorded, but getting there can involve limitless innings, hours, plays. Stadiums may appear uniform, but each has its own personality — with distinctive wind patterns, sight lines, nooks and crannies.

Look in any American town and you’ll find a ballpark with deep ties to the sport and its barnstorming, sandlot origins. A shrine, if you will, for serious fans who savor old-time values and traditions. The real thing. Such a place is as near as Omaha’s Johnny Rosenblatt Stadium, the site the past 49 years of the annual College World Series.

The city and the stadium have become synonymous with the NCAA Division I national collegiate baseball championship. No other single location has hosted a major NCAA tournament for so long. More than 4 million fans have attended the event in Omaha since 1950.

The 1998 CWS is scheduled May 29-June 6.

In what has been a troubled era for organized ball, Rosenblatt reaffirms what is good about the game. There, far away from the distraction of major league free-agency squabbles, the threat of player/umpire strikes, and the posturing of superstars, baseball, in its purest form, takes center stage. Hungry players still hustle and display enthusiasm without making a show of it. Sportsmanship still abounds. Booing is almost never heard during the CWS. Fights are practically taboo.

The action unwinds with leisurely grace. The “friendly confines” offer the down-home appeal of a state fair. Where else but Omaha can the PA announcer ask fans to, “scooch-in a hair more,” and be obliged?

Undoubtedly, the series has been the stadium’s anchor and catalyst. In recent years, thanks in part to ESPN-CBS television coverage, the CWS has become a hugely popular event, regularly setting single game and series attendance records. The undeniable appeal, besides the determination of the players, is the chance to glimpse the game’s upcoming stars. Fans at Rosenblatt have seen scores of future big league greats perform in the tourney, including Mike Schmidt, Dave Winfield, Fred Lynn, Paul Molitor, Jimmy Key, Roger Clemens, Will Clark, Rafael Palmeiro, Albert Belle, Barry Bonds and Barry Larkin.

The stadium on the hill turns 50 this year. As large as the CWS looms in its history, it is just one part of an impressive baseball lineage. For example, Rosenblatt co-hosted the Japan-USA Collegiate Baseball Championship Series in the ‘70s and ‘80s, an event that fostered goodwill by matching all-star collegians from each country.

Countless high school and college games have been contested between its lines and still are on occasion.

Pro baseball has played a key role in the stadium’s history as well.

Negro League clubs passed through in the early years. The legendary Satchel Paige pitched there for the Kansas City Monarchs. Major league teams played exhibitions at Rosenblatt in the ‘50s and ‘60s. St. Louis Cardinal Hall of Famer Stan Musial “killed one” during an exhibition contest.

For all but eight of its 50 years Rosenblatt has hosted a minor league franchise. The Cardinals and Dodgers once based farm clubs there. Native son Hall of Famer Bob Gibson got his start with the Omaha Cardinals in ‘57. Since ‘69 Rosenblatt’s been home to the Class AAA Omaha Royals, the top farm team of the parent Kansas City Royals. More than 7 million fans have attended Omaha Royals home games. George Brett, Frank White and Willie Wilson apprenticed at the ballpark.

With its rich baseball heritage, Rosenblatt has the imprint of nostalgia all over it. Anyone who’s seen a game there has a favorite memory. The CWS has provided many. For Steve Rosenblatt, whose late father, Johnny, led the drive to construct the stadium that now bears his name, the early years hold special meaning. “The first two years of the series another boy and I had the privilege of being the bat boys. We did all the games. That was a great thrill because it was the beginning of the series, and to see how it’s grown today is incredible. They draw more people today in one session than they drew for the entire series in its first year or two.”

For Jack Payne, the series’ PA announcer since ‘64, “the dominant event took place just a couple years ago when Warren Morris’ two-run homer in the bottom of the ninth won the championship for LSU in ‘96. He hit a slider over the right field wall into the bleachers. That was dramatic. Paul Carey of Stanford unloaded a grand slam into the same bleacher area back in ‘87 to spark Stanford’s run to the title.”

Payne, a veteran sports broadcaster who began covering the Rosenblatt beat in ‘51, added, “There’s been some great coaching duels out there. Dick Siebert at Minnesota and Rod Dedeaux at USC had a great rivalry. They played chess games out there. As far as players, Dave Winfield was probably the greatest athlete I ever saw in the series. He pitched. He played outfield. He did it all.”

Terry Forsberg, the former Omaha city events manager under whose watch Rosenblatt was revamped, said, “Part of the appeal of the series is to see a young Dave Winfield or Roger Clemens. Players like that just stick out, and you know they’re going to go somewhere.” For Forsberg, the Creighton Bluejays’ Cinderella-run in the ‘91 CWS stands out. “That was a real thrill, particularly when they won a couple games. You couldn’t ask for anything more.”

The Creighton-Wichita State game that series, a breathtaking but ultimately heartbreaking 3-2 loss in 12 innings, is considered an all-time classic. Creighton’s CWS appearance, the first and only by an in-state school, ignited the Omaha crowd. Scott Sorenson, a right-handed pitcher on that Bluejay club, will never forget the electric atmosphere. “It was absolutely amazing to be on a hometown team in an event like that and to have an entire city pulling for you,” he said. “I played in a lot of ballparks across the nation, but I never saw anything like I did at Rosenblatt Stadium. I still get that tingling feeling whenever I’m back there.”

A game that’s always mentioned is the ‘73 USC comeback over Minnesota. The Gophers’ Winfield was overpowering on the mound that night, striking out 15 and hurling a shutout into the ninth with his team ahead 7-0. But a spent Winfield was chased from the mound and the Trojans completed a storybook eight-run last inning rally to win 8-7.

Poignant moments abound as well. Like the ‘64 ceremony renaming the former Municipal Stadium for Johnny Rosenblatt in recognition of his efforts to get the stadium built and bring the CWS to Omaha. A popular ex-mayor, Rosenblatt was forced to resign from office after developing Parkinson’s disease and already suffered from its effects at the rededication. He died in ‘79. Another emotional moment came in ‘94 when cancer-ridden Arizona State coach Jim Brock died only 10 days after making his final CWS appearance. “That got to me,” Payne said.

Like many others, Payne feels the stadium and the tourney are made for each other, “It’s always been a tremendous place to have a tournament like this, and fortunately there was room to grow. I don’t think you could have picked a finer facility at a better location, centrally located like it is, than Rosenblatt. It’s up high. The field’s big. The stadium’s spacious. It’s just gorgeous. And the people have just kept coming.”

Due to its storied link with the CWS, the stadium’s become the unofficial home of collegiate baseball. So much so that CWS boosters like Steve Rosenblatt and legendary ex-USC coach Rod Dedeaux, would like to see a college baseball/CWS Hall of Fame established there.

Baseball is, in fact, why the stadium was built. The lack of a suitable ballpark sparked the formation of a citizens committee in ‘44 that pushed for the stadium’s construction. The committee was a latter-day version of the recently disbanded Sokol Commission that led the drive for a new convention center-arena.

With a goal of putting the issue to a citywide vote, committee members campaigned hard for the stadium at public meetings and in smoke-filled back rooms. Backers got their wish when, in ‘45, voters approved by a 3 to 1 margin a $480,000 bond issue to finance the project.

Unlike the controversy surrounding the site for a convention center-arena today, the 40-acre tract chosen for the stadium was widely endorsed. The weed-strewn hill overlooking Riverview Park (the Henry Doorly Zoo today) was located in a relatively undeveloped area and lay unused itself except as prime rabbit hunting territory. Streetcars ran nearby, just as trolleys may in the near future. The site was also dirt cheap. The property had been purchased by the city a few years earlier for $17 at a tax foreclosure sale. Back taxes on the land were soon retired.

Dogged by high bids, rising costs and material delays, the stadium was finished in ‘48 only after design features were scaled back and a second bond issue passed. The final cost exceeded $1 million.

Baseball launched the stadium at its October 17, 1948 inaugural when a group of all-stars, featuring native Nebraskan big leaguers, beat a local Storz Brewery team 11-3 before a packed house of 10,000 fans.

Baseball has continued to be the main drawing card. The growth of the CWS prompted the stadium’s renovation and expansion, which began in earnest in the early ‘90s and is ongoing today.

Rosenblatt is at once a throwback to a bygone era — with its steel-girdered grandstand and concrete concourse — and a testament to New Age theme park design with its Royal Blue molded facade, interlaced metal truss, fancy press box and luxury View Club. The theme park analogy is accentuated by its close proximity to the popular Henry Doorly Zoo.

Some have suggested the new bigness and brashness have stolen the simple charm from the place.

“Maybe some of that charm’s gone now,” Forsberg said, “but we had to accommodate more people as the CWS got popular. But we still play on real grass under the stars. The setting is still absolutely beautiful. You can still look out over the fences and see green trees and see what mid-America is all about.”

Payne agrees. “I don’t think it’s taken away from any of the atmosphere or ambience,” he said. “If anything, I think it’s perpetuated it. The Grand Old Lady, as I call it, has weathered many a historical moment. She’s withstood the battle of time. And then in the ‘90s she got a facelift, so she’s paid her dues in 50 years. Very much so.”

Perched atop a hill overlooking the Missouri River and the tree-lined zoo, Rosenblatt hearkens back to baseball’s and, by extension, America’s idealized past. It reminds us of our own youthful romps in wide open spaces. Even with the stadium expansion, anywhere you sit gives you the sense you can reach out and touch its field of dreams.

NCAA officials, who’ve practically drawn the blueprint for the new look Rosenblatt, know they have a gem here.

“I think part of the reason why the College World Series will, in 1999, celebrate its 50th year in Omaha is because of the stadium we play in, and the fact that it is a state-of-the-art facility,” said Jim Wright, NCAA director of statistics and media coordinator for the CWS the past 20 years.

Wright believes there is a casual quality that distinguishes the event.

“Almost without exception writers coming to this event really do become taken with the city, with the stadium and with the laidback way this championship unfolds,” he said. “It has a little bit different feel to it, and certainly part of that is because we’re in Omaha, which has a lot of the big city advantages without having too many of the disadvantages.”

For Dedeaux, who led his Trojans to 10 national titles and still travels each year from his home in Southern California to attend the series, the marriage of the stadium-city-event makes for a one-of-a-kind experience.

“I love the feeling of it. The intimacy. Whenever I’m there I think of all the ball games, but also the fans and the people associated with the tournament, and the real hospitable feeling they’ve always had. I think it’s touched the lives of a lot of people,” he said.

Fans have their own take on what makes baseball and Rosenblatt such a good fit. Among the tribes of fans who throw tailgate parties in the stadium’s south lot is Harold Webster, an executive with an Omaha temporary employment firm. While he concedes the renovation is “nice,” he notes, “The city didn’t have to make any improvements for me. I was here when it wasn’t so nice. I just love being at the ballpark. I’m here for the game.” Not the frills, he might have added.

For Webster and fans like him, baseball’s a perennial rite of summer.

“To me, it’s the greatest thing in the world. I don’t buy season tickets to anything else — just baseball.”

Mark Eveloff, an associate judge in Council Bluffs, comes with his family. He said, “We always have fun because we sit in a large group of people we all know. You get to see a lot of your friends at the game and you get to see some good baseball. I’ve been coming to games here since I was a kid in the late ‘50s, when the Omaha Cardinals played. And from then to now, it’s come a long way. Every year, it looks better.”

Ginny Tworek is another fan for life. “I’ve been coming out here since I was eight-years old,” the Baby Boomer said. “My dad used to drop me and my two older brothers off at the ballpark. I just fell in love with the game. It’s a relaxing atmosphere.”

There is a Zen quality to baseball. With its sweet meandering pace you sometimes swear things are moving in slow motion. It provides an antidote to the hectic pace outside.

Baseball isn’t the whole story at Rosenblatt. Through the ‘70s it hosted high school (as Creighton Prep’s home field), collegiate (UNO) and pro football (Omaha Mustang and NFL exhibition) games as well as pro wrestling cards, boxing matches and soccer contests. Concerts filled the bill too, including major shows by the Beach Boys in ‘64 and ‘79. But that’s not all. It accomodated everything from the Ringling Brothers Circus to tractor pulls to political rallies to revival meetings. More recently, Fourth of July fireworks displays have been staged there.

Except for the annual fireworks show, however, the city now reserves the park for none but its one true calling, baseball, as a means of protecting its multimillion dollar investment.

“We made a commitment to the Omaha Royals and to the College World Series and the NCAA that the stadium would be maintained at a major league level. The new field is fairly sensitive. We don’t want to hurt the integrity of the field, so we made the decision to just play baseball there,” Omaha public events manager Larry Lahaie said.

A new $700,000 field was installed in 1991-92, complete with drainage and irrigation systems. Maintaining the field requires a groundskeeping crew whose size rivals that of some major league clubs.

Omaha’s desire to keep the CWS has made the stadium a priority.

As the series began drawing consistently large crowds in the ‘80s, the stadium experienced severe growing pains. Parking was at a premium. Traffic snarls drew loud complaints. To cope with overflow crowds, the city placed fans on the field’s cinder warning track. The growing media corps suffered inside a hot, cramped, outdated press box. With the arrival of national TV coverage in the ‘80s, the NCAA began fielding bids from other cities wanting to host the CWS.

By the late ‘80s Omaha faced a decision — improve Rosenblatt or lose the CWS. There was also the question of whether the city would retain the Royals. In ‘90 the club’s then owner, the late Chicago business magnate Irving “Gus” Cherry, was shopping the franchise around. There was no guarantee a buyer would be found locally, or, if one was, whether the franchise would stay. To the rescue came an unlikely troika of Union Pacific Railroad, billionaire investor Warren Buffett and Peter Kiewit Son’s, Inc. chairman Walter Scott, Jr., who together purchased the Royals in 1991.

Urged on by local CWS organizers, such as Jack Diesing Sr. and Jr., and emboldened by the Royals’ new ownership, the city anteed-up and started pouring money into Rosenblatt to rehab it according to NCAA specifications. The city has financed the improvements through private donations and from revenue derived from a $2 hotel-motel occupancy tax enacted in ‘91.

The makeover has transformed what was a quaint but antiquated facility into a modern baseball palace. By the time the latest work (to the player clubhouses, public restrooms and south pavilion) is completed next year, more than $20 million will have been spent on improvements.

The stadium itself is now an attraction. The retro exterior is highlighted by an Erector Set-style center truss whose interlocking, cantilevered steel beams, girders and columns jig-jag five-stories high. Then there’s the huge mock baseball mounted on one wall, the decorative blue-white skirt around the facade, the slick script lettering welcoming you there and the fancy View Club perched atop the right-field stands. The coup de grace is the spacious thatched-roof press box spanning the truss.