Archive

Artist-Author-Educator Faith Ringgold, A Faithful Conjurer of Stories, Dreams, Memories and History

I tried to get an interview with artist-author-educator Faith Ringgold before and during her visit to Omaha a few years ago but her tightly packed schedule just wouldn’t allow it. So, with an assignment due and no interview to draw on I made the best of it by planting myself at the lecture she gave here and liberally borrowing some of her comments to inform my story. I also viewed an exhibition of her work here. At the conclusion of her talk I unexpectedly heard my name intoned over the auditorium’s amplifier system. I was summoned to the stage to meet Ms. Ringgold, who apologized for not being able to speak with me earlier and offered me the opportunity to ride with her to the airport and interview her enroute. I declined because I was already rather time-pressed to get the story in but I thanked her for the offer. I thought that was a gracious and generous thing for her to do and it’s certainly not something most celebrities would think to do in the aftermath of a gig and heading out of town. Her art is sublime. She taps deep roots in her work, which is infused with images of yearning, hope, joy, and life, and some pain, too. You feel the images speaking to you. There is energy in those visuals. You sense life being lived. It’s easy to get lost in the ocean of feeling and memory she evokes.

Artist-Author-Educator Faith Ringgold, A Faithful Conjurer of Stories, Dreams, Memories and History

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Artist-author-educator Faith Ringgold spoke about the power of dreams during an October 8 lecture at Joslyn Art Museum’s Witherspoon Concert Hall, whose nearly filled to capacity auditorium testified to the popularity of her work. The official role of her Omaha appearance was to give the keynote address at the Nebraska Art Teachers Association’s fall conference. But her real mission was to deliver a message of hope and possibility, as expressed in the affirming, empowering tales of her painted story quilts, costumes, masks and children’s books and her life.

Her visit coincided with her 75th birthday, which organizers celebrated in a musical program that moved Ringgold to tears, as well as two area exhibitions of her work. Now through November 20 at the UNO Art Gallery is Art: Keeping the Faith (Ringgold), a selection of illustrations from her children’s book Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad in the Sky, along with examples of her story quilts, tankas and mixed media pieces. Now through December 23 at Love’s Jazz and Art Center is a selection of book art from Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House, along with two of her finest story quilts combining fabric, painting and narrative.

The Harlem native has broken many barriers as an African-American female artist with works in major collections, books on best-sellers’ lists and art embraced by culturally and racially diverse audiences of children and adults.

“My art has been a celebration of my life, my dreams and my struggles and how I learned from other people,” she said.

Much of her work, whether story quilts combining painted canvas on decorative fabric or book illustrations done in acrylic, depict the struggles and contributions of historical black figures. Many are in praise of the Harlem Renaissance artists she came to know, such as Alfred Jacob Lawrence. Many are about strong females like herself, ranging from underground railroad conductor Harriet Tubman to Civil Rights heroine Rosa Parks. She often creates series of works. Coming to Jones Road deals with the trains of refugees on the underground railroad. Her most recent is a jazz series called Mama Can Sing and Papa Can Blow.

“For the image of a people to be celebrated is an important thing for their creative identity,” she said.

Her books often show her child alter ego, Cassie, interacting with men and women of achievement, whose life lessons “of being resourceful, being creative and being strong” offer inspiration. In Ringgold’s award-winning Tar Beach, which began as a quilt, Cassie takes imaginative leaps of faith that enable her to fly over the world and, in so doing, own it. Flight represents the liberation that comes with dreaming.

“That’s what flying is — it’s a determination to do something that seems almost impossible,” Ringgold said. “Cassie is an expression of that feeling — Who said I can’t do it? Unless I say it, it doesn’t mean anything.”

As she reminded her Joslyn audience, many of them teachers, “Every good thing starts with a dream. Children growing up without dreams is really no growing up at all.” The “anyone can fly” and “if she can do it, anyone can” themes from Tar Beach are so closely associated with Ringgold, who also wrote a song entitled Anyone Can Fly , that they’ve become the catch phrases for her vision. After her Joslyn lecture, the Belvedere Bels choir from Belvedere Elementary School in Omaha serenaded Ringgold with a soulful rendition of Anyone Can Fly.

Related to her visit and showings here, Omaha Public Schools students this fall are studying her work, viewing her exhibits and creating their own story quilts.

Her favorite medium, the story quilt, is rooted in two African-American traditions — oral storytelling and quiltmaking — traced to slaves, who created images on quilts that recorded family history, symbolized events and revealed coded messages. She’s the latest in a long line of master quiltmakers in her own family, going all the way back to her great-great grandmother, a slave, and down through her great grandmother, grandmother and her later fashion designer mother, from whose hands she learned the craft and with whom she collaborated on her first quilts.

Beyond the familial and cultural connections, quilts appeal to Ringgold for their practicality and accessibility.

“It’s the most fantastic way of creating paintings. You have it become a quilt by piecing it together, so that it doesn’t have that fragility of one piece of paper or canvas. A quilt is really two-dimensional, but it’s also three-dimensional, and that’s why I really love it,” she said. “You can make it as big as you like it and it doesn’t have weight to it. You can roll it up and carry it around.”

She enjoys, too, the communal aspects of the form.

“Quilting is something a group of people can do. You can have a lot of people engaged in the activity, so that your art doesn’t become such a solitary thing.”

Her impetus for doing story quilts arose when editors balked at publishing her autobiography unless she changed her story to conform to what she considered a stereotypical black female portrayal. She refused and instead found an alternative form, the story quilt and performance art, for charting her life and for sharing her perspectives on the figures, events and issues affecting her and her people.

“It made me really angry to think that somebody else could decide what my story was supposed to be or decide my story’s not appropriate to me, an African American woman. So, I started writing these stories,” she said. “I used performance and story quilts to get my story out there. Writing it in the art, when the art was published in a program — the words would be to, unedited.”

When her work hangs in museums or galleries, her simple or elaborate but always eloquent words can be appreciated by viewers. Often splayed all around the borders, the text acts as a narrative frame that focuses the eye on the central image she paints in her palette of sure brushstrokes and bold colors.

The many influences on Ringgold, who studied at City College of New York and has traveled the world to soak up art, are apparent in her folk-style work, including her rich African-American heritage, the traditions of European masters, the abstract expressionists and Tibetan tankas. A professor of art at the University of California in San Diego, she lives in Englewood, NJ, where she has her studio.

She continues a busy schedule of creating art, lecturing and dreaming.

Related articles

- People who turned their dreams to reality (cnn.com)

- An Artist Ends Ties to Museum in Harlem (nytimes.com)

- Faith Ringgold Paper Quilts (rakarchives.wordpress.com)

Alexander the Great’s Wrestling Dynasty – Champion Wrestler and Coach Curlee Alexander on Winning (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

I first met up with Curlee Alexander for the following story, which appeared about eight years ago as part of my series on Omaha Black Sports Legends titled, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. Alexander was a top-flight collegiate wrestler for his hometown University of Nebraska at Omaha but he really made his mark as a high school coach, leading his teams to state championships at two different schools – his alma mater Technical (Tech) High School and North High School. He is inducted in multiple athletic hall of fames. Then, about three years ago I caught up with him again in working on a profile of his younger cousin Houston Alexander, a mixed martial arts fighter Curlee trains. You can find on this blog most every installment from the Out to Win series as well as that profile I did on Houston Alexander. More recently yet Curlee came to mind when I did a piece on the 1970 NAIA championship UNO wrestling team he helped coach as a graduate assistant and that he helped lay the foundation for as a wrestler under coach Don Benning. You’ll find that story and a profile of Benning, who is one of Alexander’s chief mentors, on this blog. The UNO wrestling program made a great impact on the sport locally, regionally, and nationally but sadly the program was eliminated a year and a half ago and now the legacy built by Alexander, Benning, and later Mike Denney and Co. can only found in record books and memories and news files. My story about the end of the program is also featured on this blog.

Alexander the Great’s Wrestling Dynasty – Champion Wrestler and Coach Curlee Alexander on Winning (from my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness)

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

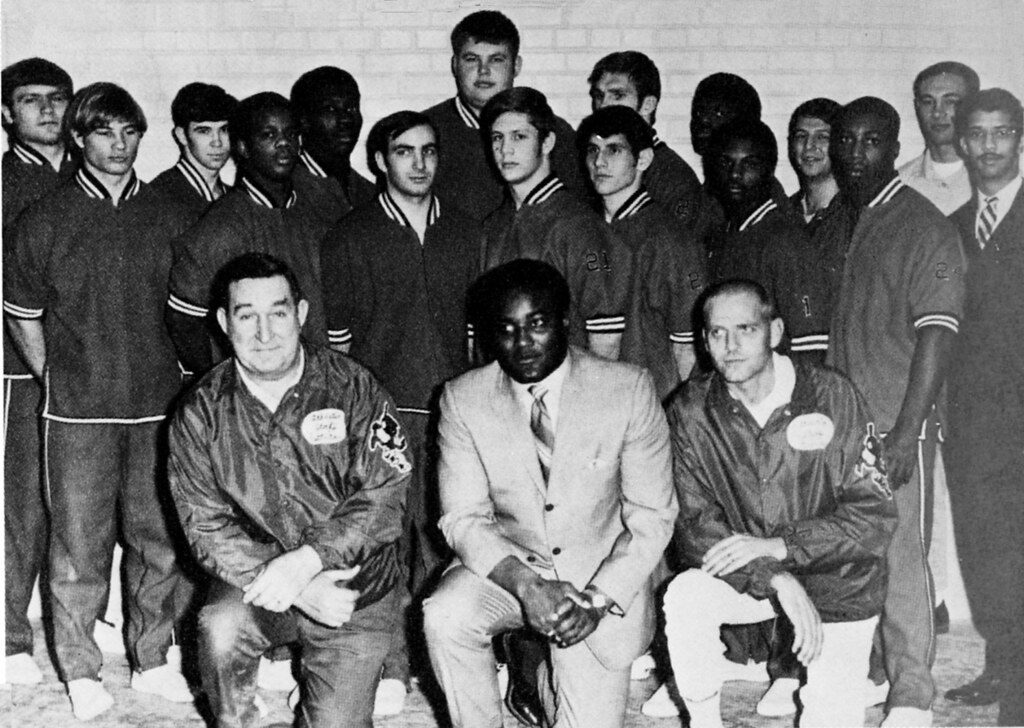

Short in stature and sleek of build, Curlee Alexander still manages casting a huge shadow in Nebraska wrestling circles even though the largely retired educator is now a co-head coach. Seven times as head coach he led his prep teams to state championships, six at Omaha North and one at Omaha Tech. Twice, his North squads were state runners-up. Four more times his Vikings finished third. Dozens of his athletes won individual state titles, including three by his son Curlee Alexander Jr., and many had successful college careers on and off the mat.

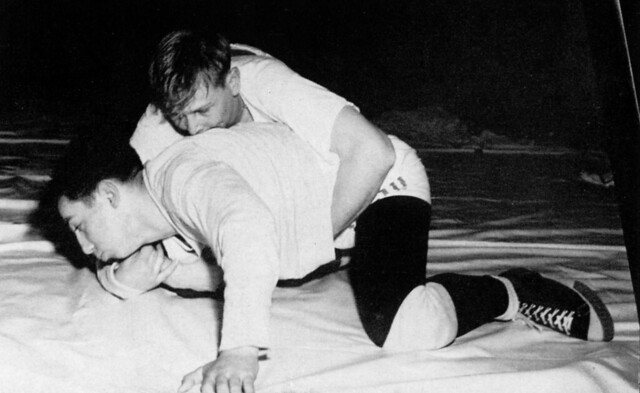

In the wrestling room, Alexander’s word is law because his athletes know this former collegiate national champion wrestler once made the same sacrifice he asked of them. Following an undistinguished high school wrestling career at Omaha Tech, his persistence in the sport paid off when he blossomed into a four-time All-American for then-Omaha University. UNO wrestling’s rise to prominence under coach Don Benning was rewarded when the team won the 1970 NAIA team title and Alexander took the 115-pound individual title in the process.

Like most ex-wrestlers, Alexander’s keeps in tip-top shape and, even pushing 60, he still demonstrates some of his coaching points on the mat with his own wrestlers — going body to body with guys less than a third his age and often outweighing him. In the old days, he pushed guys to the limit and, in wrestling vernacular, “beat up on ‘em,” to see how they responded. It was all about testing their toughness and their heart. It’s the way he came up.

Proving himself has been the theme of Alexander’s life. He grew up in a north Omaha neighborhood, near the old Hilltop Projects, filled with fine athletes. Being a pint-sized after-thought who “was always trying to catch up” to the other guys in the hood, he searched for a sport he could shine in. “I was small and weak and slow. I had to start from scratch to develop my athletic skills,” he said. “Wrestling was about the only thing I could do and I was really not very good.” To begin with.

He learned the sport from Tech coach Milt Hearn. In classic apprentice fashion, he started at the bottom and worked his way up. “When he got me started wrestling, I was used as a doormat,” Alexander said. “All I was required to do was save the team points by not getting pinned. If I could do that, than I did my job. As a junior, I got beat out by two freshmen. I was always fighting an uphill battle. I could never let up. I could never be comfortable. I knew I had to work hard. I knew I had to work harder than most of ‘em just to be successful.” Despite this less than promising debut, Alexander said he “kept getting after it. I started buying a lot of weight training-body building books and started weight lifting. By the time I got to be a senior I didn’t wrestle anybody that was any stronger than me. I finished second in every tournament I entered my senior year. I never won a championship in high school. The first championship I won was when I reached college.”

Sparking his evolution from designated mop-up guy to legitimate contender was the motivation others gave him. “I had a lot of good role models, one of which was my father. He always preached athletics to us.” Where his father encouraged him, his brother dis’d him. “My brother was a much better athlete than I was, so I was always trying to do things, more or less, to impress him. I’d come home after losing and my brother would make comments like, ‘I knew you weren’t going to win,’ and so I picked up the I’m-going-to-show-you attitude. I was never the athlete he was, but I accomplished a lot more in the athletic arena than he ever dreamed of.”

Then there were the studs he grew up with in the hood, guys like Ron Boone, Dick Davis, Joe Orduna and Phil Wise, all of whom went onto college and pro sports careers. If that wasn’t motivation enough to hurry up and make his own mark, there were the reminders he got from friend and Omaha U. classmate Marlin Briscoe, who was making a name for himself in small college football. “I tried out for the wrestling team and there was a returning wrestler who beat me out. I saw Marlin at the student center and he asked, ‘How’d you do?’ I told him I got beat by this guy and he said, ‘Man, that guy’s no good…he got beat all the time last year.’” And that guy never beat me again. All I needed to hear were little things like that.”

Fast forward a few years later to Alexander’s national semi-final match in Superior, Wis. His opponent had him in a good lock and was preparing to turn him when Alexander recalled something former Tech High teammate, Ralph Crawford, told him about the winning edge. “He told me, with emphasis, ‘Give him nothing,’ and because of that little inspiration I knew I had a little extra to do, and it made a difference in my winning that match and going on to be a national champion.”

There was also the example set by his UNO teammates, Roy and Mel Washington, a pair of brothers who won five individual national titles (three by Roy and two by Mel) between them. “Probably the one I learned the most from, as far as determination, was the late Roy Washington,” who later changed his name to Dahfir Muhammad. He was just a great leader. Phenomenal. I watched him. Everything he did I tried to do and it made all the difference in the world. He knew how to work. He knew what it took. He just refused to get beat. He was real mentally tough,” Alexander said. “If you’re weak-minded, you can forget it.”

Finally, there’s Don Benning, whom Alexander credits for giving him the opportunity and direction to make something of himself. “He’s the reason I have a college degree and was able to go on and teach and coach for 30-odd years. He gave me a chance where I had no other chance,” he said. “He made you believe you could achieve. I wouldn’t have been able to achieve nearly as much success if I hadn’t been under his tutelage. As far as coaching, I basically followed his philosophy. Hard work. Refuse to lose. Being the best on your feet. I built on that foundation.”

Surrounded by superb tacticians, Alexander drew on this rich vein of knowledge, as well as his own from-the-bottom-to-the-top experience as a wrestler, to inform his coaching. “I took a little bit from everybody and applied it. In dealing with kids I tell them I know what it’s like to be weak and not have any athletic ability, and yet go to the top. I teach kids what they need to do in order to improve, to stay dedicated, to be successful and to be champions. What I strive to do as a coach is lead by example. I work out with them to show I’m not afraid to work.”

Much like Benning, whom he coached under as a graduate assistant, Alexander doesn’t try fitting athletes into a box. He lets them develop their own style. “If I’ve got a kid who’s got some decent ability I don’t tell him he’s got to wrestle this way or that way. We try to get what he’s got and improve on it and try to impress upon him to keep working until he understands what it takes to be a champion.”

A young Curlee Alexander in his UNO wrestling singlet, ©UNO Criss Library

Champions. He’s coached numerous team and individual titlists. As satisfying as the team wins are, he said, they “don’t compare to the individual ones. The kids put so much effort into it.” He said a coach must be a master motivator to figure out what makes each individual tick. “All the time, I’m looking for angles to get into a kid’s head to get him to believe,” he said. “What separates a lot of coaches is getting those kids to believe your philosophy is correct. It boils down to being able to communicate and to have kids want to succeed for you and themselves.”

He makes clear he expects nothing less than champions. “I’ve got a lot of guys that have placed at state, but if they didn’t win a state championship, their picture does not go up on the wall in my office. That might be kind of harsh, but it’s reality. That’s what we’re trying to get our kids to strive for and win. Championships are what it’s all about.” He said his favorite moments come from kids who aren’t talented, yet get it done anyway and claim a championship that lasts a lifetime. North High heavyweight Brandon Johnson is an example. “He wasn’t really a good athlete. Overweight. He had to cut down to 275. But he was a hard worker and he had a big heart,” Alexander said. “And, boy, when he won state in 2001, I had tears in my eyes for the first time. I didn’t even cry when my son won, because it was understood he was going to win. But with this guy, it really wasn’t expected. It was just a culmination of all the hard work he gave.”

The hardest part of coaching is seeing “kids do all that hard work and then, when they get right there to the doorstep” of a championship, “they don’t win it.”

The heralded prep coach began as an assistant at Tech, whose wrestling program he took over in the mid’70s. He remained at Tech until it closed in 1984, when he went to North, where he’s remained until retiring from teaching full-time in 2002. The next year he stepped down as head coach to serve as associate head coach and lately he’s added Dean of Students to his duties. As co-head coach, he’s freed himself from all the red-tape to just work with the wrestlers. When his mentor, Don Benning, recently expressed surprise at how much passion Alexander still has for the sport, the former student replied, “I still enjoy it. I enjoy the strategy. I enjoy the competition. I enjoy working with the kids. They keep you young.” He said matching Xs and Os with coaches during a match never gets old. “I really think I’m very good at it and, boy, when I’m successful at it, it’s exhilarating.”

Alexander’s been a pioneer in much the same way Don Benning was at UNO in the ‘60s and Charles Bryant was at Abraham Lincoln High School (Council Bluffs) in the ‘70s. Each man became the first black head coach at their predominantly white schools, where they established wrestling dynasties. In more than 75 years of competition, Alexander is the only black head coach in Nebraska to lead his team to a state wrestling title (and he’s done it at two different schools). Along the way, he built a dynasty at North, which in all the years previous to his arrival had won but a single state wrestling championship. He had six as head coach. Through it all, he’s defied expectations and overturned stereotypes by doing it his way.

Related articles

- Closing Installment from My Series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From My Series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Can Houston Alexander Break Gilbert Yvel? (mmaggregate.wordpress.com)

Carole Woods Harris Makes a Habit of Breaking Barriers for Black Women in Business and Politics

In the struggle African-Americans have waged to achieve equal footing in education, employment and housing as well as in leadership positions, elected or not, the progress made has not always made banner headlines. In fact many of the gains have happened quietly and largely under the radar. That’s certainly the case with Carole Woods Harris, who achieved one first after another for black women in Omaha, Neb., where she became a leader in business and in local-county government by persistently moving through the ranks, networking, proving herself just as capable as her male counterparts, and along the way gaining a reputation for being a methodical and savvy operator who never lost touch with her roots. This profile I wrote of Harris appeared about a decade ago.

Carole Woods Harris Makes a Habit of Breaking Barriers for Black Women in Business and Politics

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the New Horizons

When former US West executive and current Douglas County Commissioner Carole Woods Harris first applied at the phone company in the late 1950s, the then-Technical High School honors student eagerly sought one of Ma Bell’s long distance operator openings. It was an era when women, regardless of ability, were limited to narrow roles in the workplace. Any job at the fat phone company was prized. A job there meant a steady paycheck and, if one stayed put, the promise of a pension at the end of a long career. There was even the possibility of advancing into a better paying spot. In reality, few women actually did.

Although the precocious Carole, then known by her maiden name Anders, was told by company officials she more than qualified for the job, she was denied it and, instead, got offered an elevator operator slot. The snub was the first bitter taste of racism in this young black woman’s life. A proud Carole rejected the offer on the spot. However, with the Civil Rights Movement beginning to open doors for blacks, she soon found herself called back by the company, which did an abrupt about-face and tendered her the same position she wanted in the first place. She accepted this offer because, one, she deserved it and, two, her family badly needed the money. Carole was the oldest of three children in a single-parent family (her mother and father were separated) and the Anders barely scraped by on what her mother made working as a maid and what the family received in welfare assistance. “Bear in mind,” she said during a recent interview from her northwest Omaha home, “this is the best job that anybody in my family had ever had.”

The same young woman who had enough moxie to say “No thanks” when treated unfairly and enough good sense to say “Thank you” when opportunity knocked, made this bottom-rung job her entry into the business world, where she blazed a trail for other minorities in climbing the corporate ladder over a 30-year career with the communications giant, much of it spent in management.

High achievement is something Harris, a Kellom Grade School and Tech High graduate, was brought up to expect despite growing up in poverty. Her self-confidence and lofty expectations came from the many stalwart women in her life. Chief among them were her mother, Frances, and maternal grandmother, Elizabeth. “I was raised and influenced, you might say, by a number of strong black women. My mother was a very intelligent woman who finished high school with the skills to be a secretary, which was probably the top of the ladder for women at that time. But that was something in Omaha she was not able to do because of her race. Many of the parents of her generation had that experience. My mother could only find work as a house maid all the time I was growing up. She ended up being able to get into a decent job when she got on at the Post Office, which began hiring blacks. But what I got from my mother was the belief that things were going to get better for us. My mother instilled the attitude that I could do whatever I wanted and the importance of being prepared to do it. So, she instilled a lot of hope.”

In her grandmother Elizabeth, Harris found an example of how to persevere and stay true to core beliefs through trying times. “My mother’s mother was a widow who raised nine children. By the time she was in her 40s she lost her sight (due to glaucoma). Yet, she helped to raise her grandchildren. I often consider my grandmother as the most saintly person I’ve known. She had a very strong faith.” The family, led by grandma, regularly attended Morningstar Baptist Church. Today, Harris worships at Clair Memorial United Methodist Church.

While establishing herself as a player in business circles, Harris began making her presence known as a community volunteer and board member. She is the past chair of the Eastern Nebraska Human Services Board of Governors. She still serves on the boards of numerous health and human service agencies, including the United Way of the Midlands. More recently, she has emerged as a savvy politico giving voice to minority concerns. Along the way to becoming a community leader, she raised a family. The twice-divorced Harris has three children from her first husband — sons Vernon and Michael and daughter Kimberly. She is a grandmother of four. Her only regret, she said, is not finishing her college education, something she put on the back-burner to take care of business.

A black woman elevator operator in Virginia in the era Carole Woods Harris worked the same job in Omaha

Upon being the first black promoted into middle management from within then-Northwestern Bell in the 1970s, she became a figure of inspiration for a group of long-time employees who filled the very job the company tried steering her into more than a decade earlier. “There were several black women working as elevator operators then, and these beautiful, special women were so encouraging and supportive of me when I started. They mothered me. They just showed such a sense of pride in me,” she said, her voice breaking at the thought of how much she meant to them and how much they meant to her. Once she made her way into the halls of power, first as a district manager for directory publishing and eventually as director of strategic planning, she knew her double-minority status made her a closely watched symbol inside and outside the corporation. She knew there were those who suspected her rise into the management ranks was due to affirmative action quotas than her own merits. That others scrutinized her every move to see if she really belonged and carried her own weight. And that still others expected her presence to be a gateway for more blacks. All of which made her feel even more pressure then she already put on herself.

“It’s not unusual for people in that situation to always feel they’ve got to make an effort to be twice as good” as their white counterparts,” she said of the awkward position she was in. “So, I guess I pressured myself. I knew it was important that others have the opportunity to follow me, and if I didn’t do well it would adversely impact the opportunities for others and would be used as an excuse” to not hire more minorities. She acknowledges she did sometimes “wonder…if what was happening to me was because I’m black or because I’m a woman. I think my experiences were impacted by a combination of my race and my sex.”

In addition to having to prove herself, she faced the challenge of gaining access into the male-dominated executive suite, essentially a men’s club whose “suits” did a lot of business on the golf course or the local tavern, where women colleagues were unwelcome. “Well, I didn’t golf, so I started inviting myself to lunch with them,” she explained. “It hadn’t occurred to them. I looked for any ways to make myself part of the Old Boys Network.” By all measures, she succeeded, becoming a highly-admired manager who could stand her ground with the boys.

Frank Peterson, a former senior manager with US West, said her ascendancy at the company was “no window dressing,” adding: “She was no showcase. She was a very competent manager and a very well-respected leader that more than held her own in any position she was placed in, and I think that’s a real asset to her. The examples she set were excellent.”

For much of her time in management, Harris oversaw a group “responsible for publishing all of the directories for a five-state region.” She supervised staffs in Omaha, Des Moines and Minneapolis. Near the end of her career (she retired in 1990) her role as a strategic planner found her deeply involved in the merger of the so-called Baby Bells (Northwestern Bell, Pacific Bell and Mountain Bell) that created US West. That meant a lot of streamlining and downsizing to eliminate redundancies and to maximize efficiencies. “When you bring three companies together,” she said, “you have a lot of duplication. My job was basically working through that.” Her dedication to those cost-cutting measures was so complete she even phased-out her own role in the company. “As part of that process, one of the things I did was eliminate my own job. I was in a position to see it coming and as a result I was made less afraid of that change.”

She took early retirement at 50, leaving behind an accomplished legacy. Her old colleague, Peterson, said, “She brought a dignity to her role, whatever it was. She has the ability to say what’s necessary to be said, to say it well and to say it in an unemotional way. It’s a characteristic I witnessed many times. Also, she’s an excellent listener. As a team player she could adapt quickly to any situation. She could always see the big picture, not only her own responsibility, but that of the greater need. The telephone business was filled with a bunch of great people…and when you think about the people you cherished and the people you could count on, she ranks way up in that realm. Her path just leaves people feeling good.”

Once separated from the company she had come of age in, Harris made a frank self-assessment and, when the opportunity presented itself, pursued a life in public service. “If you’ve been with a company for 30 years that publishes directories and provides long distance service, it’s hard to see what value you have outside that context,” she said.”That started me to do a better job of identifying how the skills I gained were transferable to other venues.”

Her attraction to city-county government actually began several years before when, in the early 1980s, she was appointed by then-Mike Boyle to the Omaha Personnel Board. Her tenure on the Board coincided with a tumultuous turn of events when the incumbent Boyle, whom she serves with today on the Douglas County Board, was recalled, Councilman Steve Tomasek filled in as Acting Mayor and Councilman Bernie Simon was elected by the Council to serve out the deposed Mayor’s term. “I chaired one of those major hearings during all the turmoil,” she recalled. It was during that time she mentioned to fellow Democrats she “might be interested in serving in public office” and, sure enough, political operatives approached her a few years later about running against incumbent City Councilman Joe Friend. After some hesitation, she put her hat in the ring and challenged Friend in the 1989 election.

She lost, but valued the chance it gave her to surface issues, the primary one being “the need for the City and its elected officials to pay greater attention to all segments of the community. There were areas that were significantly under-served.” While she admits she “had a lot to learn” about the political process, she considered her failed bid “a very good experience.”

The call to service came again in 1992 when she ran for and was elected to the District 3 Douglas County Commissioner’s seat. Motivating her to seek office, she said, was her “interest in the health and human services areas the county is responsible for and an interest in understanding the budget process and being able to have that process be fair to all areas of the county being served.”

Her victory gave her the distinction of being the first black elected to the Douglas County Board. In a state that falls well behind the rest of the nation in funding services for disadvantaged populations, Harris has used her office as a forum for strengthening existing programs and creating “more community-based services for children-at-risk as well as for mental health and chemical dependency patients.” She sees many needs still going unmet. “In the youth area I see more need in the way of prevention-based services for at-risk youths and their families. We continue to be too heavily dependent on detention.” She also sees “huge gaps” in youth mental health services. “Because the slots aren’t available in Kearney (at the youth rehabilitation center there) and in other county facilities, we are sending too many young people out-of-state at a very high cost for services that we should be able to provide right here locally.” Harris chaired the Nebraska Juvenile Services Grant Committee and helped develop the county’s Community Juvenile Services Plan.

A black woman who shares much in common with Harris, former Omaha City Council member Brenda Council, admires the leadership qualities her friend embodies.

“I think she’s been not only a tremendous representative for her district, but for the county. She’s done a tremendous job on the County Board. Two words that describe her are — integrity and dignity. She makes decisions based on what she believes is right, but she does that after she considers everyone else’s opinion. She brings reason and rationality to her decisions. She’s just a calm-steady presence. That’s her style,” Council said.

Fellow Douglas County Commissioner Clare Duda echoed Council’s observations about Harris. “Carole has a calmness and common sense unlike anybody else I’ve had the pleasure of serving with,” he said. “I can always count on her to not let politics or sensationalism cloud her vision. She’s hard-working, she does her homework and she’s well-connected in the community. She sticks to her guns when she knows what’s in the best interest for her constituents. I have just the utmost respect for her.”

Council, the first black president of the Omaha School Board and the second black to serve on the City Council, also appreciates the example Harris sets: “Carole Woods Harris is certainly someone that young people should look to as a model. She’s paved a path that others can follow.”

As one of two Democrats currently on the seven-member Douglas County Board, Harris carefully selects her battles, preferring to work quietly behind-the-scenes to forge alliances on issues she feels strongly about. “I guess I see myself more as a catalyst or facilitator. The main game that’s played” with a policy-making body like this “is counting votes and sometimes, given the makeup of the Board, it’s more helpful to work out a coalition and have someone else take the lead. If it’s most helpful for me to be out there running in front about something I care about it, I will, but often it’s better just to be a vote and to be less concerned about who gets credit for it.” Harris has been on the other side, too. When she joined the Board she was part of a Democratic majority. “You operate one way if you’re one of five versus if you’re one of two. So, you need to be flexible.”

Her lone Democratic colleague on the Board, Mike Boyle, sees Harris as a steadying influence and as a simpatico voice for the underdog. “She’s able to bring-on discussion of relatively controversial subjects without any acrimony or heated discussion, but she sure gets the point across. She gets right to the core of the problem. She’s a woman of very high standards. Her ethics are uncompromising. There are some fundamental things she believes that she will not yield on. Yet, she’s very easy to get along with. Carole and I do not always vote the same way but we do share some values, including the basic belief in the need for county government to serve its primary purpose — and that is to serve people who really need help. In many cases, we are the government of last resort.”

With 10 years on the Board, Harris, along with Duda, are the County Board’s senior Commissioners. She considers her duties “a fascinating challenge.” The best thing about it, she said, “is the good feeling you can have when you succeed at making a difference.” Among the most “frustrating” things, she said, is how hard it is to reach an accord. “I describe this Board as being like a seven-headed executive. All these executive decisions are dependent upon these seven people agreeing.” Then, there’s the intrusion it brings in her personal life. “I’m an awfully private person to have run for public office, and so the worst thing is how much you give up in privacy.” Last winter found her uncharacteristically sharing her private life when she spoke to the World-Herald about a trip to South Africa she made as part of a women’s service organization she belongs to, Links Inc., which helped build 32 schools there. Harris and fellow Links members attended dedication ceremonies for the schools and ushered in a South African Links chapter.

In South Africa she found a nation struggling to overcome an oppressive legacy of apartheid that resonates with America’s own racist legacy. In her understated way, Harris expresses some passionate views about the issue of race. She feels predominantly black northeast Omaha is still largely alienated from the majority white culture.

“I think the community is much more separated and divided than it should be,” she said. “I’ve had too many experiences where individuals who live in the western part of the community are afraid or unwilling to venture into the eastern part of the community, where I live, as though it’s a war zone. It’s not what people perceive it to be. The power structure would like to think there are no (racial) problems and in that regard I think they have a head-in-the-sand attitude. There’s been slow progress in building good relationships with the police. At times, I’ve seen that go backwards. There are some real educational challenges. There are way too many children in the disadvantaged areas of the community who’ve been allowed to fall through the cracks.”

In a positive vein, she acknowledges progress has been made on the job and housing fronts and that her own success story offers proof of that.

Not one to look back, Harris looks forward to completing her Commissioner’s term and then moving onto some new challenges. Always looking to improve herself, Harris, a graduate of leadership and management programs, an avid reader and a world traveler, may go back to college for that long-deferred degree. Whatever she does, she will doubtlessly bring her quiet strength and grace to the task.

Related articles

- Black Women – We’re All We Have (theladiesfeed.wordpress.com)

- Honoring the Black Women (afroveg.wordpress.com)

- Black Women Still Battle ‘Mad Men’ (thedailybeast.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Great Migration Comes Home: Deep South Exiles Living in Omaha Participated in the Movement Author Isabel Wilkerson Writes About in Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- North Omaha Champion Frank Brown Fights the Good Fight (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

The Last Hurrah for Hoops Wizard Darcy Stracke

Darcy Stracke was one of those small town wonders in the world of sports. By the end of her freshman year in high school she was already a legend in her hometown of Stuart, Neb. for her prodigous talent in volleyball, basketball, and track and she only added to the legend her last three years in high school in Chambers. Neb. By the time she graduated she held a batch of state scoring records in basketball. A playmaking and scoring guard in one, she spurned offers from big schools to play hoops at Division II University of Nebraska-Kearney, where she dominated once again. Then, in a move that upset her fan base, she transfered to the University of Nebraska at Omaha, and promptly made her mark in her only year there. In a strange twist she set the UNK single game scoring record of 43 points against her future teammates at UNO and then when playing for UNO she broke that school’s single game scroring mark with a matching 43 points against, you guessed it, her former teammates at UNK. She was a multiple all-state performer in high school and a three-time All-American in college. She’s in the athletic hall of fame of every school she competed for. I wrote this piece during her final college season in 2000.

The Last Hurrah for Hoops Wizard Darcy Stracke

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Omaha Weekly

Scene One: Penetration is her game.

Wherever she is with the ball, her first instinct is to take it to the house. Using a crossover dribble, she first measures her opponent. Then, feinting with the ball, her head or both, she jump-stops inside, double-pumps and either banks a shot in off the glass, draws a foul or else dishes off to an open teammate for an assist. What sticks with you is her fearlessness inside and her uncanny knack for weaving through a tangle of bodies to make something happen.

Before some recent struggles, it seemed UNO’s fabulous hoops star, Darcy Stracke, could do no wrong. Time after time, she took over games, racking up points at will and disrupting opposing teams’ offenses. A case in point came in the Mavs’ mid-season 68-50 home win over NCC rival South Dakota. She scored 29 points on 12-of-16 shooting from the field and flashed a variety of take-your-breath-away passes, now-you-see-it-now you-don’t dribbles, pickpocket steals and whirling-dervish drives to the bucket. And all this in only 26 minutes of play.

Afterwards, she stopped by the north bleachers to chat with her star struck fans. There is a definite star quality about Stracke, a 5-foot-7 senior guard whose game intensity belies a quiet off-court demeanor and whose grace-under-pressure endures despite sweaty palms. Among her regular admirers (some sporting her jersey No. 34) are a group from her hometown of Stuart, Neb., including her parents, Marilyn and Del, who have made it to every game but one since her freshman year in high school. She is their small-town-girl-makes-good hoops diva.

That night, Stracke, still dressed in her damp uniform, lingered a long while with the crowd. She seems to savor these moments. Not because she enjoys the attention or adulation (In truth, she’d rather not have all this fuss made about her.), but because she knows the wondrous run she’s been on is finally drawing to a close. For this north-central Nebraska native has enjoyed a legendary athletic career matched by few other Nebraska female athletes. But soon her glory days will be over. The scoring feats, the fancy moves, the late-game heroics relegated to hazy memories or grainy video highlights.

For Stracke, steeped in athletics from an early age (she learned to walk with a basketball) and hooked on competition the way others are on drugs, the thought of not playing (notwithstanding a possible pro stint overseas) is daunting. How could it not be for someone who sleeps with a ball to get “in tune with it”?

“When I step on that court it’s like I’m in another world,” she said. “I get a feeling I can’t get anywhere else. I love that feeling. I don’t feel any aches or pains. It’s just like I’m in a zone. Basketball is probably in my head most of every 24 hours. I watch game films all the time. If basketball’s on TV, I’m going to watch it. If I can get a pick-up game, I’m going to play it. Basketball has always been an outlet for me, so if I’m having a bad day, I always look to basketball to get me out of that funk, even if it means going up to the gym at 10 o’clock at night and shooting. Once I start shooting, everything else is erased.”

More than anything, she’ll miss the competition when she walks away from the game. “I just love to compete.” Then there are the fans who have been there for her all this time. “I have my own little fan section. They expect me to come over and talk. I love the interaction with people after games. It’s those little things I’m going to remember.” Wherever she went the past eight years, her legion of fans followed. They were there at the start, when she led Stuart Public High to the Class D-2 state title as a 14-year-old freshman. Then, after transferring to nearby Chambers Public School, where she played for brother-in-law, John Miller, they saw her spark a 77-game winning streak en route to three more state titles and, in the process, she set the state’s all-time scoring record (boys or girls) with 2,752 points. Along the way she displayed a court savvy beyond her years, anticipating picks, screens and passing lanes for steals and assists and driving the lane for layups.

When she chose nearby Division II powerhouse University of Nebraska-Kearney over several Division I schools, fans kept right on trucking to see how she matched-up at the next level. Just fine, thank you. She broke the school’s single season scoring record (679 points), topped its career steals mark (292), twice led the Lopers’ into the post-season (three times if you count her injury-shortened junior year) and capped off 1998-99 by earning 1st Team All-America honors.

Then the soft-spoken Stracke, 21, surprised everyone last off-season by transferring from UNK (she politely declines discussing why) to UNO for her final year. While rehabbing an injured knee in Kearney over the summer Stracke was deluged with calls, letters and visits from boosters pressuring her to reconsider. The “trauma” all got to be too much. “A lot of people were disappointed I left. I kind of avoided people there for a while, but I stayed because that’s where my friends and family are,” she said. “It was just a better fit here (UNO) for me. I think people who care about me understand it’s something I did for my own happiness.”

Once this season began and the buzz around “the Darcy situation,” as it’s known in Kearney, died down, all was forgiven, and the Stracke bandwagon kept rolling down I-80 as before, only a little farther east, to cheer her on in Omaha, where all she’s done is lead the nation in scoring for much of the year (she is second now with an averages just under 23 points per game) and rejuvenate a program (UNO is 15-10) that had scuffled recently (11-16 last year and 10-17 the year before). Stracke paced the Mavs to a fast start (7-2) and the team held its own in the middle part of the year before slumping down the stretch. Last Saturday’s 74-58 road loss to Northern Colorado dropped the Mavs to 1-4 in their last five games and squashed any remaining hopes of an NCAA regional post-season berth. Stracke, who struggled some herself lately, enjoyed a strong outing with 23 points, 5 boards and 4 steals, although she did have 6 turnovers.

She and her Mavs will try to play spoiler in season-ending road games this weekend versus ranked league foes North Dakota and North Dakota State.

It is a shame her career will end without one last hurrah in the playoffs, especially after her banner junior year ended prematurely when she suffered a complete ACL tear in her right knee during the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference tourney. And, yes, it seems unfair Omaha hoops fans have had her such a short time. Seeing her go will be tough. Just ask UNO Head Coach Paula Buscher, who took a chance signing her to play for a single year. It was strictly a one-shot deal. No encore season. No promise things might not fizzle for the scoring phenom (they haven’t). No assurance she would recover from her injury (she has). No guarantee her addition might not upset team chemistry (it hasn’t).

“That was the risk that was out there for herself as well as the people recruiting her when she was transferring with one year left,” Buscher said. “We obviously felt and still feel it was a great decision on our part. There was a risk involved, but we felt like with a player of her caliber and her stature, and with the work ethic she brings, that that was a risk we needed to take. Would I love to have her for another two or three years? Oh, heavens, yes. Unfortunately, that’s not the way it works. We knew that going in. A great player’s career always ends too short. I just feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to coach her for one year. I mean, let’s face it, the kid can play. She brings it every night. I think she’s helped develop a different mind-set (winning) and raise expectations with our program, and that’s something we’re looking to carry on.”

Buscher, like UNK Head Coach Amy Stephens before her, knew what she was getting in Stracke all right. She closely followed Stracke’s brilliant prep career and then, while coaching against her in college, saw her her light-up UNO twice, including a 43-point explosion last year. Still, once Buscher got a chance to watch Stracke at work, up close, every day in practice, she realized UNO had gained even more in the bargain than what first met the eye.

“Everyone was aware of her athletic ability and what she could do in games, but the bonus with Darcy was seeing how she trains. From the first day of preseason, all the way throughout every single practice, she’s the first one out there for every sprint, every drill, pushing all the time. Bottom line, she’s a competitor who wants to win. That, more than anything, is what makes her a great player,” Buscher said.

Scene II: Whatever it takes.

A perpetual motion machine on the floor, she never stops competing — regardless of the score. On defense, she creates havoc by hounding ball handlers into errant passes or by swiping lazy dribbles. On offense, she sets the tone by hustling down court, chasing after loose balls and constantly working to get open.

Not a great perimeter shooter, Stracke gets most of her points in or near the paint. Because defenses focus on her, she must often create shots where there are none. Her she-got-game greatness was never more evident than in three early season tests. First, she shook off jitters in a much-anticipated Dec. 1 contest against UNK, when, in a bit of perfect symmetry, she led UNO to an 86-71 victory and, in the process, burned her old mates for a school-record 43 points, the exact total she posted against UNO last year (UNK is having the last laugh, however, as the Lopers are rolling along with a 21-4 mark and high national ranking.).

“Actually, that’s probably the one game I didn’t want to play this year just because I still have a lot of friends on the team there,” Stracke said. “I did want to have a good game, though, because it was against the school I’d been at for three years. And I was a bit more nervous for that game than for others.”

Then, on consecutive nights in mid January, she did something she’s made a habit of during her playing career: hitting buzzer-beaters to defeat Minnesota State-Mankato and St. Cloud State amid a five-game stretch in which she averaged more than 30 points. Ask her what it’s like to have the ball in her hands when the game’s on the line, and how she’s able to deliver the goods, and she answers:

“When it comes down to making free throws at the end or making that game-winning shot, I think, ‘Darcy, you’ve done this tons of times before in the backyard. You can do it again.’ It’s not like I haven’t taken those last-minute shots before. So, I just shoot it with a lot of confidence and play with a lot of confidence. Plus, when I get in those situations I want to do well because I care about my teammates and I know I’d let them down if didn’t make that shot. The feeling after you make it is indescribable. It’s so exciting.”

She fees her success as a clutch performer and multi-faceted player (she leads UNO in scoring and steals and is second in assists) is largely due to all the hard work she’s put in honing her skills, including keeping the neighbors up while shooting past midnight in her backyard. “I may not have as much athletic talent as some players, but what’s been to my advantage is I do put a lot of hours in at the gym, and I think that’s what makes me a better basketball player and what gives me more confidence. I expect the best out of myself.”

In The World According to Darcy Stracke, effort breeds confidence which, in turn, breeds success. “Everything I’ve competed in (she was also a top volleyball, track and softball competitor) I always believed I could win. And, if I didn’t win, I’d go back and make adjustments or try to work on something that was my weakness, and the next time I was going into that competition I wasn’t going to lose.”

She further developed her game by routinely playing against the opposite sex and by challenging older, more experienced, players to one-on-one contests.

“I think it really helps playing against men and boys. It makes you adjust your game because if you don’t you’re going to get your shot blocked or get your pass stolen. Now, when I go against girls in college, I remember to use that extra fake.”

Since entering college she has experienced more losing than she ever did before, and even though it irks her, she long ago came to terms with that and the fact she can’t dominate every game like she did in high school.

“I just hate to lose. Even if its a card game or playing whiffle ball in the backyard. Then, after my teams went 77-0 my last three years in high school, I lost my very first college game. It was really hard because I wasn’t used to losing. But if I’ve learned anything it’s that you’re going to struggle sometimes at the college level. There are lots of ups and downs. The competition is so much better.”

Like many top athletes, she is somewhat obsessive-compulsive preparing for competition. She has game-day rituals she dares not break for fear of throwing her whole rhythm off.

“I have a routine for everything and, if I get out of synch, it just bothers the heck out of me. It ranges all the way from what I eat to when I step on the court to how long I drill in pregame warmups. I mean, it’s to the point where my routine is the same every single second, every single time.”

It’s that kind of attention to detail that’s made her settle for nothing less than being an all-around player. “If I don’t show up in every statistical area, from steals to assists to rebounding to even shooting percentage, I don’t feel like I had a good game. A lot of people look for me as a scorer, but I want to be a complete player because the only way our team is going to get better is if I can be consistent in every category.”

Despite the fact her new team has fallen far short of what her UNK clubs achieved (Kearney went 80-11 her three years there), she has no regrets about leaving such success behind for the mediocrity she found at Omaha. “I knew what I was coming into. I knew they’d (UNO) struggled. But I wanted to come to a program where I could make a difference. I think it’s worked out really well. My teammates have accepted me with open arms. I’m glad I’m here.”

All too aware the clock is fast running out on her playing career, Stracke acknowledges she has been pressing a bit, going a combined 22-of-79 from the field in a five-game stretch before regaining her touch last week (7-of-14 from the field and 8-of-8 from the line) against UNC. Heading into her final collegiate competition, she is poised to earn All-America honors again and owns combined career totals of 2,211 points, 422 rebounds, nearly 400 steals and 373 assists in 114 games.

Sadly, her last hurrah will come far from home. Local hoops fans who missed her in action are the real losers since the next time she (a K-12 physical education major) takes the court again in front of a crowd, will likely be as a coach.

“I love new challenges, If I don’t go over overseas to play ball I’m going to try and be a grad assistant somewhere to get my foot in the door in college coaching. I’m actually pretty excited to see basketball from a coaching standpoint.”

Still, coaching can never replace the thrill playing has given her.

“Basketball’s always been my first love. I’ve always played with a lot of passion. I’ve been struggling a little bit with the fact that I have less than a handful of games left, and then I’m done. I’ve been counting down the games. I’m just going to go out and play like every game is my last because pretty soon it will be.”

Scene III: In synch.

If there is any lasting image of her, it is her streaking down court in transition — her raised arms extended high overhead, her expectant hands just aching to touch the ball once more. You want to yell, ‘Give her the damn ball.’ Give it to her, indeed. The two were made for each other.

Related articles

- Omaha Hoops Legend John C. Johnson: Fierce Determination Tested by Repeated Run-Ins with the Law (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- From the series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness – Black Women Make Their Mark in Athletics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Photojournalist Nobuko Oyabu’s own journey of recovery sheds light on survivors of rape and sexual abuse through her Project STAND

Photojournalist Nobuko Oyabu has dedicated herself to a lifetime project portraying the individual hunanity of persons who have suffered rape or sexual abuse. Her intent is to beyond the label of victim to show who these people are. The work is dear to her for many reasons, not the least of which is her own recovery from rape. She delivers a message to the world in her pictures and in her words that the hurt survivors feel is real and profound but that healing is possible. She lets survivors, their families and friends, and the public know that the assault or the abuse and its aftermath need not define women. She delivers this message through a support organization she formed, through photographs she takes of survivors, through educational presentations she gives, and through writing she does on the subject, including her autobiography (Stand, published in Japan). She has been much honored for her work. I wrote the following profile of Nobuko several years ago, when she still lived in Omaha, Neb., where she’d come to work for the Omaha World-Herald. She and her family have since moved on elsewhere but her work continues, as does the praise for her efforts.

Photojournalist Nobuko Oyabu’s own journey of recovery sheds light on survivors of rape and sexual abuse through her Project STAND

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Omaha City Weekly

Omaha photojournalist Nobuko Oyabu’s work on rape and sexual abuse first made waves in the States. Now it’s stirring things up in her native Japan. On visits there in the last year she’s exhibited her intimate portraits of survivors and given talks about her own story and her subjects’ stories of survival.

She was raped in 1999.

She’s also returned to her homeland to promote her new book, Stand (Forest Press). Published in October, it’s made best seller lists there. The book reveals the trauma of sexual assault through the prism of her personal odyssey and of the men and women she’s chronicled. Her book’s title is drawn from a national project she launched in Omaha to document survivors from across America and in Canada.

Some survivors want to be photographed at the very site they were abused. It isn’t always possible. When it is, it’s an emotional scene. The survivor seeks to reclaim power and control lost in the attack. It’s about closure. In one image a man weeps in the cabin he was molested in as a boy. Some images reveal artifacts of human suffering. A woman shows scars from cuts she makes on herself. Oyabu said self-mutilation is common among survivors as a way of dealing with post-traumatic stress. Another holds a photo of herself as a child made-up as a whore by her abusive dad. Innocence lost. Others choose places and poses that represent their recovery.

Oyabu said Stand is an expression of “how I stood up to the tragedy that happened to me and also of the stands of other survivors. Part of the meaning as well is that sometimes you can’t do anything but just stand there and wait. You can’t always be brave or do something great.”

The fact she’s openly discussing such traditionally taboo subjects in Japan has made her something of a sensation there. Major media outlets in Tokyo, her hometown of Osaka and other cities have profiled her.

“I think I’m the very first person speaking out” on this issue there, she said. In Oyabu’s view Japan harbors, much like the U.S., dysfunctional attitudes about rape and sexual abuse rooted in denial.

“A lot of women tend to be very quiet about it and just suffer silently. It’s really hard for them to be open about it,” she said.

She said a Japanese columnist questioned in print whether she’s actually a survivor after one of her upbeat presentations. Yes, the subject is sober but that doesn’t mean she has to be.

“This particular writer thought that was not appropriate at all. He wrote, ‘I wonder if it really happened to her?’ I wasn’t what he thought a survivor should look like,” she said. “So how should I look? Do I always have to be depressed? I mean, c’mon, I have a daughter. I have a responsibility to make her happy. I can’t be depressed.”

Oyabu said, “It’s kind of hard to attach faces to the issue” amid such perceptions, “It’s kind of hard to see the reality and people don’t really want to see it. But it’s not like all survivors are in depression, stigmatized and bitter. I certainly don’t see myself that way. I’ve found a lot of people don’t see themselves that way.

“If you have a preconceived idea of how a survivor looks, you can never get the real person in the picture.”

Faces of Rape and Sexual Abuse

©photos of survivors by Nobuko Oyabu

Before her own attack, she said, “I admit I had the same attitude toward rape victims. I thought rape belongs to somebody else. I didn’t know there are so many different kinds of survivors until I met them.”

Oyabu’s black and white images express the full spectrum of survivors in terms of education, occupation, income, race, ethnicity, age, shape, size. She said, “I consciously selected these people” to represent they are not just one thing or another. Sexual assault does not discriminate along demographic lines. “It happens to everyone,” she said. Just as survivors are not all rich or poor, black or white, they are not all grim or mad. Many are content, confident, proud, defiant. Count Oyabu among these. Her self-portrait on her book’s cover shows an assertive, ever curious woman poised with camera in hand.

“My resistance was the key for me,” she said.

While large urban papers in Japan gave her positive coverage, reprinting some of her images, she said smaller rural papers displayed a more close-minded attitude and refused to run her pics. She found that “odd” considering her images are in no way graphic but merely portraits. She thinks such reluctance stems from outdated notions that survivors should not be seen or heard — a byproduct of a larger bias that fixes blame or shame on survivors.

“With sexual assault there’s so much gray area still,” she said. “Too many people think it’s the victim’s fault. In this country as well.”

That the blame game should persist in Japan, she said, is ironic given it “is the capital of pornography in the world. There’s so much human trafficking and child porn going on…and somehow the blame is shifted to the victims.” She said sex is right out front in Japan, as it is here, “and yet when it comes to sexual violence people don’t want to acknowledge it,” much less talk about it. Similarly, she said America and Japan don’t want to examine the implications of sex being so pervasive yet rarely discussed at home or school. “Not talking about it,” she said, results in high rates of sexual assault, sexually transmitted diseases, promiscuity, prostitution. This pregnant silence, she said, explains why most sexual assaults go unreported.

“A lot of people are in denial,” she said, “especially parents who grew up in a home where abuse took place. A lot of people have no idea what to say — they just don’t know how to talk about it. Survivors don’t know who to talk to or where to go.”

In lieu of information, she said, some people suffer abuse not realizing they’ve been victimized. She notes a disturbing trend among young people she speaks with who routinely tell her they’ve been molested or raped but pass it off “as no big deal” — as if it’s a rite of passage. “It’s really sad,” she said.

Then there’s the way rape is historically minimized by society, drawing light sentences for actions that have long lasting effects.

Oyabu noted, “One of the survivors put it like this: ‘The rapist gets three to five years, the victims get life.’ And that’s exactly it. It’s not just a one-time incident. For a lot of people it takes a lifetime to get over it. I find it disturbing that society doesn’t see rapists as high risk criminals.”

The reaction her work’s elicited in Japan is not unlike its reception in the U.S. Her STAND: Faces of Rape and Sexual Abuse Survivors Project has been a traveling exhibition across America. Her work with survivors and her personal identification with them and their trauma has made her a sought-after figure. She’s testified before Congress about the issue. She’s spoken to medical, health and law enforcement professionals. She’s presented at women’s and survivors conferences as well as colleges and universities. She’s served as visiting faculty at the Poynter Institute (Fla.) for a seminar on how the media reports rape. She and her work have been part of national awareness campaigns and a Lifetime documentary. She’s written articles for publications here and abroad.

In 2003 she received the Visionary Award from the DC Rape Crisis Center along with comedian Margaret Cho and poet Alix Olsen.

Still, her work is not always appreciated. She said while on staff at the Omaha World-Herald in 2000-2002 senior editors there nixed her doing a photo-essay series on sexual assault survivors. The material, she was told, was too intense for the paper. She said some journalists criticize her for crossing ethical lines as a reporter who documents fellow survivors like herself.

“But if you can use your personal experience to get an exclusive story,” she asks, “then why not use it as a tool?”

Although she defines herself a photojournalist rather than survivor or advocate, her work’s inextricably linked to her experience. Stand centers on the aftermath of her rape — the turmoil she felt and the healing she found. In this light, she said, the images she makes, the talks she delivers, the testimonies she shares serve an educational purpose. “The work of journalism is educating people,” she said. More than anything, she wishes to give survivors names and faces just like her own.

Oyabu was a young, single, up-and-coming photographer with the Moline (Ill.) Dispatch in 1999 when she was raped. She had come to the States only a few years before to pursue her post-secondary education. She wanted to write but found her niche with a camera at Columbia College in Chicago. She went on to shoot a diverse range of subjects for newspapers in the Quad Cities.

Her life and career were full of bright promise when she suffered the ultimate violation and everything grew dark. The rape occurred far from her family in Osaka, where her father pastors a Christian church and her mother teaches preschool. It would be six years before she told her parents what happened. She said, “I didn’t want to worry them too much…I didn’t have the courage to tell,” In the wake of her revelation, she said, “my family has been very supportive.”

The violent act took place at night in her own home. She was sleeping in the bedroom of her locked apartment when the male perpetrator, a former neighbor she didn’t know, broke in using a crowbar. The petite Oyabu never stood a chance. As soon as the stranger left she ran to neighbors and called 911. The cops that caught the case treated her with care on the scene and at the hospital ER they took her to. The medical staff respectfully collected what they needed for the “rape kit” that police and prosecutors use to help convict rapists.

While treated well, Oyabu said she did overhear a doctor ask a nurse, Why is she crying? As she’s since discovered, the law enforcement and medical communities are not always as sensitive as they could be. At a 2005 University of Nebraska Medical Center presentation she told doctors, nurses and students that most sexual assaults are committed by a relative, friend, acquaintance or colleague, meaning victims “take a huge risk even to come out to the ER. You are among the first to respond to these victims when they reach out for help,” she implored the audience, “so please be compassionate to these people.”

Care must be taken with victims, she said, as the trauma of rape is exacerbated by the trauma of examination and interrogation and the suggestion — intentional or not — that somehow the victim’s at fault.

Oyabu provided police a description of her assailant, who left behind the crowbar, his hand prints, hair and other incriminating details. He was caught after only three days. The fact her rapist was captured at all, much less so swiftly, is atypical, she said. The remainder of that year is a blur of counseling sessions, depositions, trial proceedings and attempts to get on with her life. Due to the overwhelming evidence she was spared having to testify. The repeat offender was given the maximum sentence by the judge — 20 years — and is currently serving his time in an Illinois state pen. Again, she said, that is not the norm.

Even with some closure, Oyabu endured flashbacks, nightmares, anxiety attacks and depression. She lived in fear. She rarely let her guard down around men.

The counselor she was referred to at a Quad Cities family services center helped Oyabu work through her emotions. “She made sure I understood that it (the rape) wasn’t my fault. That’s one of the biggest steps for healing.”

A counselor friend suggested she keep a journal. Oyabu said journaling provided a healthy release. Later, her entries proved a key resource for her book. That same friend asked Oyabu to participate in a project that had victims’ harsh self-portraits and words printed on T-shirts. “All I saw was shame and anger on them,” she said. “These T-shirts were faceless. I didn’t belong there — I have feeling and hope. I’m not just a statistic.” This picture of bitter fruit was not the image she had of herself or other survivors, a term she prefers to victims.

“Well, I don’t want to be bitter forever,” she said. “Survivors don’t want you to feel sorry for them or see them as some kind of damaged goods.”

She’d already discovered survivors could be anyone. After her rape several friends came forward with their own stories. “It was really a shock to me all these close friends from college were rape survivors. I didn’t know it,” she said. “I guess my friends didn’t know how to start the conversation about it. Once I was victimized they felt like they could talk now.”

Four of the five women she served on a panel with at the Poynter Institute turned out to be survivors. Smart, successful professionals like her. They’re everywhere.

Oyabu came to Omaha not just for a job but to escape the place where she was raped. “I couldn’t really stay in the same city,” she said. Also, Omaha had a lower incidence of sex crimes. The thought of it happening again plagued her. She wanted to feel safe. But that took time and work. It came with the help of Dee Miller, a fellow writer and survivor in Council Bluffs, and Pastor William Barlowe, pastor of Omaha’s Grace Apostolic Church, where she met her husband, IT specialist Patrick McNeal. The couple have a 2-year-old daughter, Ellica.

Another turning point came when she wrote a letter to her rapist. “As soon as I dropped the letter in the mailbox,” she said, “I felt a kind of joy I’d never experienced. I started to smile and laugh again. I felt like I was totally set free.” Forgiveness is a work in progress.

The next piece of her recovery was her faces of survivors work. When the Herald balked at doing anything she bolted in frustration and liberation. “I was like, Forget them, I’ll do it on my own. She did, too, largely self-funding what became the Stand project. Fees from speaking engagements and exhibits helped.

She said the project’s been “part of my healing, It’s been healthy for me.” She’s met some survivors who can’t move on or can’t find closure — still mired in their pain. “That’s totally understandable. I was there.” She’s met others who dedicate themselves to the cause — working to make a difference with survivors and first responders. Others lead fulfilling lives and careers outside the issue. She keeps in contact with many. For herself, she said, “sometimes I just can’t believe how far I’ve come and how much I’ve done the past six, seven years. I’m alive.”

The prospect of writing about her survival scared her until she found she could divorce herself from the emotion of that trauma. The process was cathartic. She’s now translating Stand for an English language edition to be published in the U.S. by year’s end. Her photo project lay dormant the past few years as she worked on the book and adjusted to motherhood. This year she may capture new images for the project on two trips she’s making to Japan, where survivors who surfaced after her last appearances there requested to be part of her archive. In the future she may revisit her original portrait subjects to further chart their journey of recovery.

Meanwhile, she’s contemplating her next project. Exploring sexual assault in Asian countries interests her. Whatever she does, she won’t be afraid to take a stand.

Resources:

NATIONAL SEXUAL VIOLENCE RESOURCE CENTER

Nobuko is a honorary board member of NSVRC. NSVRC serves as the nation’s principle information and resource center regarding all aspects of sexual violence.

Clothesline Project of Japan

a project of survivors and their remained families of sexual abuse express their thought in drawing on T-shrits.(in Japanese)

Parents United of the Midlands

a site whose mission to bring light to the darkness of sexual abuse

Advocate Web

free resource for victims and their families

Welcome to Barbados

a Tori Amos inspired website for rape and sexual abuse survivors

Related articles

- Supporting Survivors of Sexual Assault (healthyheels.wordpress.com)

- April Is Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM) (kcareyinfante.com)

- The Medical Minute: Sexual abuse can have long-term effects (medicalxpress.com)

- Self-esteem, recovery from sexual abuse (gwizlearning.wordpress.com)

- 39 Million Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse (livingstonparentjournal.wordpress.com)

Closing installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An appreciation of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

Here is the closing installment from my 2004-2005 series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness, An Exploration of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends. In this and in the recently posted opening installment I try laying out the scope of achievements that distinguishes this group of athletes, the way that sports provided advancement opportunities for these individuals that may otherwise have eluded them, and the close-knit cultural and community bonds that enveloped the neighborhoods they grew up in. It was a pleasure doing the series and getting to meet legends Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Gale Sayers, Ron Boone, Marlin Briscoe, Johnny Rodgers, et cetera. I learned a lot working on the project, mostly an appreciation for these athletes’ individual and collective achievements. You’ll find most every installment from the series on this blog, including profiles of the athletes and coaches I interviewed for the project. The remaining installments not posted yet soon will be.

Closing installment from my series Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness,

An Appreciation of Omaha’s Black Sports Legends

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally published in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Any consideration of Omaha’s inner city athletic renaissance from the 1950s through the 1970s must address how so many accomplished sports figures, including some genuine legends, sprang from such a small place over so short a span of time and why seemingly fewer premier athletes come out of the hood today. As with African-American urban centers elsewhere, Omaha’s inner city core saw black athletes come to the fore, like other minority groups did before them, in using sports as an outlet for self-expression and as a gateway to more opportunity.

As part of an ongoing OWR series exploring Omaha’s Black Sports Legends, this installment looks at the conditions and attitudes that once gave rise to a singular culture of athletic achievement here that is less prevalent in the current feel-good, anything-goes environment of plenty and World Wide Web connectivity.