Archive

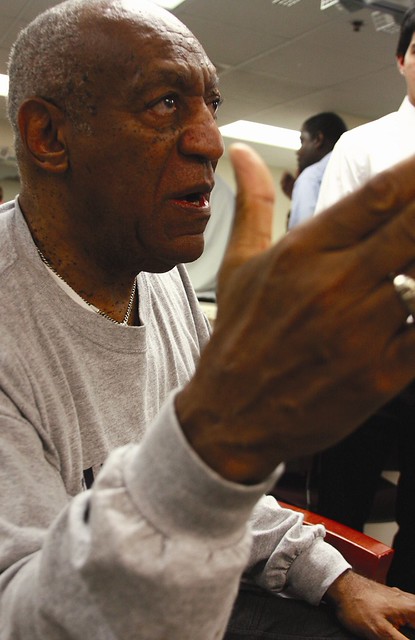

Bill Cosby on his own terms: Backstage with the comedy legend and old friend Bob Boozer

UPDATE: It is with a heavy heart I report that hoops legend Bob Boozer, whose friendship with Bill Cosby is glimpsed in this story, passed away May 19. Photographer Marlon Wright and I were in Cosby’s dressing room when Boozer appeared with a pie in hand for the comedian. As my story explains, the two went way back, as did the tradition of Boozer bringing his friend the pie. This blog also contains a profile I did of Boozer some years ago as part of my Omaha Black Sports Legends series, Out to Win: The Roots of Greatness. For younger readers who may not know the Boozer name, he was one of the best college players ever and a very good pro. He had the distinction of playing in the NCAA Tournament, being a gold medal Olympian, and winning an NBA title.

My Bill Cosby odyssey continued in unexpected ways the first weekend in May.

After interviewing him by phone for two-plus hours in advance of his Sunday, May 6 show, I secured a face to face interview with him in his dressing room. Photographer Marlon Wright accompanied me. Only moments before our meeting, however, it appeared there would be no face time with the legend. Word of our backstage interview somehow hadn’t reached Cosby and as we walked into his Orpheum Theater dressing room he was unsuccessfuly trying to confirm things with his PR handler. That’s when I assured him I was the same reporter who had talked to him by phone at length. When he gave me a look that said, “Do you know how many reporters I talk to?” I blurted out, “I’m the remedial man,” referring to our shared past of testing into remedial English in college, something that became a recurring joke between us during that marathan phone interview. “Why didn’t you say so?” he said, and just like that we were in.

After 15 minutes or so I was prepared to thank him for his time when an assistant came back to announce that Cosby’s old Omaha friend, Bob Boozer, who was a college All-American. Olympic gold medalist and NBA titlist, was outside. Cosby’s face lit up. Marlon and I exchanged a quick look that said, ‘Let’s stick around,” and so we did. What played out next was an intimate look at how a King of Comedy holds court before going on. Boozer brought a sweet potato pie his wife Ella baked.

Cosby was obviously touched and kidded his friend with, “I appreciate you not getting into it.” These two former athletes traded good-natured jibes about each others’ ailments and at one point Cosby placed his hands on Boozer’s knees and intoned, like a faith healer, “Heal.”

Then the assistant popped in again with memorabilia fans had brought for Cosby to sign, which he did, and not long after that a contingent from Boys Town was ushered in to meet The Cos. Family teachers Tony and Simone Jones, along with their son and nine young men who live with them, plus some BT staffers, all filed in and Cosby greeted each individually. What played out right up until his curtain call was a scene in which Cosby peppered the adults and kids with probing questions, sometimes kidding with them, sometimes dead serious with them. It turned into a mini lecture or seminar of sorts and a very cool opportunity for these young people, who might as well have been The Cosby Kids from Fat Albert or from his family sit-coms.

By the time we all said goodbye our expected 15 minutes with Cosby had turned into 45 minutes and we’d gotten a neat glimpse into how relaxed and down to earth the entertainer is and just how well and warmly he interacts with people. I stayed for the show of course and it was more of the same, only a more animated Cosby was revealed.

©photo by Marlon Wright, mawphotography.net

©photo by Marlon Wright, mawphotography.net

Bill Cosby on his own terms: Backstage with the comedy legend and old friend Bob Boozer

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to appear in the New Horizons

Holding court in his Orpheum Theater dressing room before his May 6 Omaha show, comedy legend Bill Cosby was thoroughly, authentically, well, Bill Cosby.

The living legend exuded the easy banter, sharp observations and occasional bluster that defines his comedic brand. He was variously lovable curmudgeon, cantankerous sage and mischievous child.

He appeared tired, having played Peoria just the night before, but his energy soared the more the room filled up.

With his concert start nearing and him blissfully unaware of the time, he played host to this reporter, photographer Marlon Writght, old chum Bob Boozer and the family teachers and youth residents of a Boys Town family home.

By turns Cosby was entertainer, lecturer, father-figure and cut-up as he shook hands, autographed items and told stories.

He’s made the world laugh for 50 years now as a standup comedian, though these days he performs sitting down. He said colleagues of his, including jazz musician Eubie Blake, have accused him of not having an act. Cosby simply tells stories, with occasional clips from his TV shows projected on an overhead screen.

“Eubie wasn’t angry when he said it, he was just jealous. He’s from the days of vaudeville where guys had set ups and then the punchline,” said Cosby. “I think he was looking for the set up and the punchline and all I was doing was the same thing when he’s at my house.”

By that Cosby means talking. He talks about everything and nothing at all. His genius is that he makes none of it seem designed, though his stories are based on written material he writes himself. What makes his riffs seem extemporaneous is his impromptu, conversational delivery, complete with pauses, asides and digressions, just like in real life. Then there are the hilarious faces, voices and sounds he makes to animate his stories. What sets him apart from just anyone talking, he said, “is the performance in the storytelling.”

His enduring appeal is his persona as friend or neighbor, and these days uncle or grandfather, regaling us with tales of familiar foibles. He invites us to laugh at ourselves through the prism of true-to-life missteps and adventures in growing up, courting, parenting and endless other touchstone experiences. Making light of the universal human condition makes his humor accessible to audiences of any age or background.

“That’s the whole idea of the writing – everybody identifying with it,” he said.

That’s been his approach ever since he began taking writing seriously as a student at Temple University in his native Philadelphia. He found his voice as a humanist observer while penning creative writing compositions for class.

“I was writing about the human experience. Who told me to do it? Nobody. I just wrote it. Was I trying to be funny? No. Was I reading any authors who inspired me? No.”

It’s not exactly true he didn’t have influences. His mother read Mark Twain to him and his younger brothers when he was young. Just as she could spin a yarn or two, he was himself a born storyteller amusing friends and teachers. He also admired such television comics as Sid Caesar and Jack Benny, among many others, he drew on to shape his comic alter ego.

He may never have done anything with his gifts if not for a series of events that turned his life around. The high school drop out earned his GED, went to college, then left early to embark on his career, but famously returned to not only finish his bachelor’s degree but to go on and earn a master’s and a Ed.D in education.

He’s sreceived numerous honorary degrees and awards, including the Kennedy Center Honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom and The Mark Twain Prize for American Humor. There have been dark days too. His only son Ennis was murdered in 1997. The comic’s alleged infidelity made headlines.

Through it all, he’s made education his cause, both as advocate and critic. His unsparing views on education and parenting have drawn strong criticism from some but he hasn’t let the push back silence him.

He said growing up in a Philadelphia public housing project he was a bright but indifferent student, devoting more time to sports and hanging out than studying. He recalls only two teachers showing real interest in him.

“I wasn’t truant, I just didn’t care about doing anything. I was just there, man. I was still in the 11th grade at age 19.”

He describes what happened next as “divine intervention.” The high school drop-out joined the U.S. Navy., Cosby hated it at first. “That was a very rude epiphany.” He stuck it out though, working as a medical aide aboard several ships, and obtained his high school equivalency. “I spent four years revamping myself.”

He marveled a GED could get him into college. Despite awful test scores Temple University accepted him on an athletic scholarship in 1960.

“I was the happiest 23-year-old in the world. They put me in remedial everything and I knew I deserved it and I knew I was ready to work for it. I knew what I wanted to be and do. I wanted to become a school teacher. I wanted to jump those 7th and 8th grade boys who had this same idea I had of just sitting there in class.

“Being in remedial English, with the goal set, that’s the thing that began to make who I am now.”

Fully engaged in schoolwork for the first time, he threw himself into creative writing assignments. He wrote about pulling his own tooth as a kid and the elusive perfect point in sharpening a pencil.

The day dreaming that once hampered his studies became his ticket to fame. He said the idea for one of his popular early bits, “The Toss of the Coin,” came during Dr. Barnett’s American History class at Temple.

“I began to drift as he was talking about the Revolutionary War.”

Cosby imagined war as a sporting contest with referees, complete with captains from each team – the ragtag settlers and the professional British army. A coin toss decided sides. In the bit the referee instructs the settlers, “You will wear fur hats and blend into the forest and hide behind rocks and trees.” To the Red Coats, the referee says, “You will wear red and march in a straight line and play drums.”

The day dreams that used to land him in trouble were getting him noticed in the rights way. He recalls the impact it made when the professor held up his papers as shining examples and read them aloud in class to appreciative laughter.

“That was the kickoff. That’s when my mind started to go into another area of, Yes you can do, and I began to think, Gee whiz, I could write for comedians. And all my life from age 23 on, I was born again…in terms of what education and the value is. To study, to do something and be proud of it – an assignment.”

He’s well aware his life could have been quite different.

“Had it not been for the positive influence of this professor, without him reading that out loud and my hearing the class laugh, who knows, I may be at this age a retired gym teacher, well loved by some of his students.”

While a Temple student he worked at a coffee house and he first performed his humorous stories there. Then he began filling in for the house comic at a Philly club and warming-up the audience of a local live radio show.

Those early gigs helped him arrive at his signature style.

“When I was looking for that style I saw it a Chinese restaurant. It was a party of eight white people and there was a fellow talking and everybody was just laughing. Women were folding napkins up to cover their faces. This was not a professional performer. Upon analyzing it I noted three things. First of all, he’s a friend of the other seven. Secondly, he’s talking about something they all know that happened. Thirdly, it happened to him and they are enjoying listening to his experience from his viewpoint

“And so I decided that’s who I want to be, that’s the style, because my storytelling is the same thing, whether I’m talking about pulling my own tooth or sharpening a pencil until it’s nothing but metal and rubber.”

Or the vicissitudes of being a father or son.

Not everyone recognized Cosby’s talents.

“I showed this comedian working in a nightclub a thing I wrote about Clark Kent changing clothes in a phone booth. In the bit a cop shows up and says, ‘What are you doings?’ and Kent says, ‘I”m changing clothes into Superman,’ and the cop says, Look, come out of there.’ ‘No, I’m Superman, can’t you see this red S on my chest?’ And the cop says, ‘You’re going to have a red S and a black eye.’ The comic read it and said, ‘This is not funny’ Within a couple years it was on my first album.”

Cosby ventured to New York City and followed the stand-up circuit. Then came his big break on The Tonight Show. Sold out gigs and Grammy-winning recordings followed.

Along with Dick Gregory, Nipsey Russell and Godfrey Cambridge, Cosby was among a select group of black comics who crossed over to give white audiences permission to laugh at themselves. None enjoyed the breakout success of Cosby. Without his opening the doors, Flip Wilson, Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy would have found it more difficult to enjoy their mainstream acceptance.

“I would imagine it was something brand new for an awful lot of people – to see this black person talking and making a connection and laughing because, Yeah, that happened to me.”

The iconic comic’s raconteur style has translated to best selling albums and books, where he mines his favorite themes of family, fatherhood and children. His warm, witty approach has made him a television and film star.

In his dressing room he appeared fit and comfortable in the same simple, informal attire he wore on stage: gray sweatshirt with the words Thank You printed on it and gray sweatpants with a draw string. The only thing missing from his stage outfit was his flip-flops. He spoke to us in his socks.

Totally in his element, with light bulb-studded mirrors, a soft leather sofa and bottles of Perrier water within easy reach, he captivated the audience of two dozen inside the dressing room just as expertly as he did the 1,500 souls in the auditorium.

For a few minutes photographer Marlon Wright and I had The Cos all to ourselves.

Two weeks earlier I conducted a long phone interview with the comic in which he discussed the “born again” experience that led to his path as a writer-performer. We hit it off and I struck a real chord when I shared that, like him, I tested into remedial English as a college freshman.

“Hey, man, we’re remedial,” became our running private joke.

He agreed to a photo shoot. Only when Marlon and I arrived at the Orpheum his aide informed us the appointment wasn’t booked on “Mr. Cosby’s” schedule. Escorted to his dressing room, I found Cosby trying to reach his publicist to confirm things. I reminded him of our phone interview from a couple weeks back and he shot me an exasperated look that said, Do you know how many reporters I talk to?

Determined not to blow this opportunity, I blurted out, “I’m the remedial man.” “Oh, why didn’t you say so?” he said, smiling broadly and inviting me to sit down. Just then, the phone rang. It was the PR person he’d tried earlier. “Yes, yes, I got him here.” he told her. “He finally said the key word, remedial, so I let him in.”

In the weeks preceding his concert Cosby did a local media blitz to try and boost lagging ticket sales. Sitting across from him in his dressing room, less than an hour before his performance, he expressed disappointment at the low number of tickets sold but pragmatically attributed it to the show’s 2 p.m. Sunday slot.

Asked what it is that still drives him to continue performing at age 74 and he answered, “I am still in the business. I’m still thinking, I’m still writing, I’m still performing extraordinarily well, and in a master sense.” It echoed something he said by phone about going on stage with a plan but being crafty enough to go where his instincts take him.

“Once I pass that threshold from those curtains to come out and sit down I know what I would like to do but I keep it wide open. I don’t know which way it’s going to shift, and a part of it has to do with the audience and the other part has to do with me – where am I at that time and what’s the brain connecting with in terms of being excited about something.

“I did a show in Tyler, Texas and I started out with enthusiasm talking about something and then I didn’t like what I was doing and I shifted the material to nontrends to trends until finally they began to click in. In other words, some audiences are and are not, and you have to go out there and find that, find what keeps and what works. It’s 50 years now. I know exactly where to mine and what to do.”

He knows he’ll eventually hit the sweet spots. As an American Instiution he has the luxury too of having audiences in the palm of his hand.

“Now, we already have a relationship that’s wonderful because people already know I’m funny, so there’s no guessing there, but on a given day, they are or they aren’t. Are they trusting you? Do I feel that way? It’s very complex but because I’m a master at it I think you want me in that driver’s seat to turn you on.”

It takes confidence, even courage to go out on that stage.

“Yes sir, and you need that, no matter what, I don’t care if you’re a driving instructor or what. If your confidence goes bad in comedy…” he said, his voice trailing off at the thought. “Whether you’re writing or getting ready to perform or sitting with friends and talking you have to have that confidence.”

He can’t conceive of slowing down when he still has the physical energy and mental edge to perform in peak fashion. Besides, he pointed out he’s not alone pursuing the comic craft at his age. Don Rickles, Bob Newhart, Mort Sahl. Bill Dana, Dick Gregory, Dick Cavett and Joan Rivers are older yet and still performing at the top of their game.

He said he fully intends returning to Omaha and selling out next time.

“So there I am talking about coming back – see?”

Besides, comics never retire unless their mind goes or body fails. The way he looks, Cosby might be at this for decades more.

Asked if he has any favorite routines or rituals backstage, he said aside from resting and signing memorabilia, he generally does what’s made him famous – talk. He bends the ears and tickles the funny bones of theater staffers, promoters, personal assistants, friends, acquaintances, fans.

Then, as if on cue, his aide Daniel popped in to say Bob Boozer was outside. Cosby immediately lit up, saying, “Ahhhh, all right, bring Bobby in and tell him he cannot come in without my you know what.” Boozer, the hoops legend, lumbered in bearing a sweet potato pie his wife Ella baked.

“Here’s Ella’s contribution to 2012 Cosby,” Boozer said handing the prized dessert to Cosby, who accepted it with a covetous grin that would do Fat Albert proud.

“I appreciate that you didn’t get in it,” Cosby teased Boozer, who for decades has made a tradition of bringing the entertainer Ella’s home-made sweet potato pie whenever he performs here.

Boozer confided later, “He loves it. I never will forget one time at Ak-Sar-Ben he had the pie on-stage with him and somebody in the crowd asked if they could get a slice, and he he draped his arms over it and said, ‘Heavens no, this pie is going back on the plane with me…'”

The two men go way back, to when Boozer played for the Los Angeles Lakers and Cosby was shooting I Spy. A teammate of Boozer’s, Walt Hazzard, was a Philly native like Cosby and Hazzard introduced Cos to Boozer and they hit it off.

A coterie of black athletes and entertainers would gather at Cosby’s west coast pad for marathon rounds of the card game Bid Whist and free-flowing discussions.

“We usually would have a hilarious time,” Boozer recalled.

When the Lakers were on the road and Cosby was performing in the same town Boozer said he, Hazzard and Co. “would always show up at his performances and visit with him about old times and that kind of thing.”

Together again at the Orpheum the pair reminisced. They share much in common as black men of the same age who helped integrate different spheres of American culture. They were both athletes, though at vastly different levels. Cosby was a fair track and field competitor in high school, the U.S. Navy and at Temple University. Boozer was an all-state basketball player at Omaha Tech High, an All-American at Kansas State, a member of the 1960 gold medal-winning U.S, Olympic team and the 6th man for the 1971 NBA champion Milwaukee Bucks.

When Boozer entered the then-fledgling National Basketball Association in 1960 blacks were still a rarity in the league. When he retired in ’71 he became one of the first black corporate executives in his hometown of Omaha at Northwestern Bell.

Cosby’s such a staple today that it’s easy to forget he helped usher in a soft revolution. At the same time his good friend Sidney Poitier was opening doors for African-Americans on the big screen, Cosby did the same on the small screen. He became the first black leading man on network TV when he teamed with Robert Culp in the groundbreaking episodic series, I Spy (1965-1968).

Cosby broke more ground with his TV specials, talk-variety show appearances and his innovative educational children’s program, The Electric Company (1971-1973). He was the first black man to headline his own series, The Cosby Show (1969-1971). But it was his second sit-com, also called The Cosby Show (1984-1992), that became a national sensation for its popular, positive portrayals of black family life. The series made Cosby a fortune and a beloved national figure.

The two men have know each other through ups and downs. So when these two old war horses reunite there’s an unspoken rapport that transcends time.

Like any ex-athletes of a certain age they live with aches and pains. At one point Cosby placed his hands on Boozer’s knees and intoned, “Heal, heal.” Later, I asked Boozer if it did any good, and he said, “No, I wish it would though.”

Pie wasn’t the only thing Boozer brought that day. The Nebraska Board of Parole member volunteers with youth at Boys Town. A family home there he’s become particularly “attached to” is headed by family teachers Tony and Simone Jones, who at Boozer’s invitation arrived with the nine boys that live with them. Cosby went down the half-circle line of boys one by one to meet them – clasping hands, getting their names, asking questions, horsing around.

Cosby with words of wisdom for Carvel Jones

Cosby with words of wisdom for Carvel Jones

Boozer and Cosby listening to Boys Town guests, ©photos by Marlon Wright, mawphotography.net

Boozer and Cosby listening to Boys Town guests, ©photos by Marlon Wright, mawphotography.net

When told that Tony and Simone are in charge of them all Cosby saw a teachable moment and asked, “You live with them? Why? You were not drafted to look after these boys. OK, then tell me, why are you living there with them?”

“Because we feel it’s our responsibility to take care of the kids, not only our own youth but youth in society,” said Simone.

“But what made that a responsibility for you? They’re not your children,” probed Cosby.

Tony next gave it a try, saying, “Mr. Cosby I’ll answer just very simply: My mom passed when I was 12 years old, and I went to Boys Town to live…” Cosby erupted with, “Oh, really! Now you’re starting to tell me stories, you see what I’m talking about (to the boys), you guys understand me? Huh?” Several of the boys nodded yes. “The story is coming, huh? What did Boys Town do for him?” Cosby asked them. One boy said, “Helped him out, gave him a place to stay.” Another said, “Gave him a second chance.”

“Well, more than a second chance,” Cosby replied. “it took care of him,” a boy offered. “And made him take care of himself, because you can see he’s eating well,” Cosby teased the stout Jones. “And that’s why he’s living with you now – he’s trying to build you,” Cosby told the kids.

The conversation then turned to what Cosby called “the hard knock life” these kids come from. He noted that youth today confront different challenges than what he or Boozer faced growing up and that Boys Town provides healthy mediation.

“We lived with our biological parents. Now my father drank too much and said he didn’t want any responsibility, which left the whole job on my mother, so we lived in a housing project. Yet we didn’t have the pressures these guys have, the insanity that exists today, and by insanity I mean not normal. Yes, there is a normal. What is normal? Normal is, ‘Don’t do that’ – ‘OK.’ Abnormal is, ‘Don’t do that.’ ‘No, I’m going to do it because you said don’t do it.’

“When I was coming up we didn’t have Omaha, Neb. ranked high in teenage boys murdering each other. Am I making sense? We didn’t have the guns being placed in our neighborhoods. We had guys who made guns but you had better than a 70-30 chance that gun would blow up in his hands. But now we have real guns and good ones too. It’s in the home.”

Cosby said it comes down to caring and making good choices.

“The first black to score a point in the NBA, Earl Lloyd, wrote a book and he tells the story of being 14-15 years old and he comes home and his mother says, ‘Where’ve you been?’ He’s stammering, he knows he’s caught with something, avoiding telling her he’s been in a place she doesn’t want him. She says, ‘You were with those boys on that corner.’ and he says, ‘But Mama, I wasn’t doing anything.’ And his mother says, ‘If you’re not in the picture, you cant be framed,’ and if you don’t understand what I just said someone will explain it to you.

“But the idea is where are these boys coming from and what places they may have to get to. There’s a place called Girard College in my hometown. You need to look it up. Forty-three acres. I call it the 10th Wonder of the World.”

The college, where Cosby gave the commencement speech last year, has a largely African-American student enrollment and graduates a high percentage of its students, most of whom come from at-risk circumstances. He said it’s a shining example of what can be.

“What’s missing in this society for black people and people of color is to own something, a small business to build upon. Many of you because of your color you will get the feeling, Yeah I can study and I can be but once I step away from college and go outside of that there are too many people that look at my color and listen to my language and they wont really welcome me. And all of you here know exactly what that feels like.”

Then, turning to Tony and Simone and referring to the boys, he said, “We’ve got to do more with fellows like these for them to do shadowing, to find business people willing to allow the boys to not go get coffee or to tie their shoes but to shadow, and it can happen in hospitals, it can happen in factories, businesses, so that these young males begin to understand what they can do.”

Cosby clearly admires the difference that adults like Tony and Simone make, saying he can see “the joy of these boys knowing that you guys care.”

“It’s about showing them the possibilities,” said Simone.

And with that, the legend bid his guests goodbye. As the entourage filed out with smiles, handshakes and break-a-leg well wishes this reporter was reminded of what Cosby said about the possibilities he began to see for himself once his college English professor took notice.

“I knew I was on track with what I wanted to do.”

Things have come full circle now and Cosby embraces the each-one-to-teach-one position of inspiring young people to live their dreams, to realize their potential.

“Hey, hey, hey…”

Related articles

- Bill Cosby Coming to Omaha to Perform Comedy Concert May 6 (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Fat Albert And The Cosby Kids: The Complete Series (werd.com)

- Bill Cosby: “We’ve Got To Get The Gun Out Of The Hands… (alan.com)

- Did Bill Cosby change how America views African American families? (tammymv.wordpress.com)

- Bill Cosby Visits Drexel’s Family Health Services Center Ahead Of Expansion (philadelphia.cbslocal.com)

- Bill Cosby Speaks His Mind on Education (wordpressreport.wordpress.com)

Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them

African-Americans from the town where I live, Omaha, Neb., are often amused when they travel outside the state, especially to the coasts, and people they first meet discover where they are from and invariably express surprise that black people live in this Great Plains state. Yes, black people do live here, thank you very much. They have for as long as Nebraska’s been a state and Omaha’s been a city, and their presence extends back even before that, to when Nebraska was a territory and Omaha a settlement. Much more, some famous black Americans hail from here, including musicians Wynonie Harris, Buddy Miles, Preston Love Sr. and Laura Love, Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson, Hall of Fame running back Gale Sayers, Heisman Trophy winner Johnny Rodgers, the NFL’s first black quarterback Marlin Briscoe, actress Gabrielle Union, actor John Beasley, producer Monty Ross, Radio One-TV One magnate Cathy Hughes, and, wrap your mind around this one, Malcolm X. That’s right, one of the most controversial figures of the 20th century is from this placid, arch conservative and, yes, overwhelmingly white Midwestern city. He was a small child when his family moved away but the circumstances that propelled them to leave here inform the story of his experience with intolerance and bigotry and help explain his eventual path to enlightenment and civic engagement in the fight to resist inequality and injustice. Though the man who was born Malcolm Little and remade himself as Malcolm X had little to do with his birthplace after leaving here and going on to become a national and international presence because of his writings, speeches, and philosophies, some in Omaha have naturally made an effort to claim him as our own and to perpetuate his legacy and teachings. Much of that commemorative and educational effort is centered in the work of the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation based at the North Omaha birthsite of the slain civil rights activist. The following story, soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com), gives an overview of the Foundation and recent progress it’s made. Rowena Moore of Omaha had a dream to honor Malcolm X and she led the way acquiring and securing the birthsite and ensuring it was granted historic status. After her death a number of elders maintained what she established. Under Sharif Liwaru’s dynamic leadership the last eight years or so the organization has made serious strides in plugging MXMF into the mainstream and despite much more work to be done and money to be raised my guess is that it will someday realize its grand plans, and perhaps sooner than we think.

Omaha’s Malcolm X Memorial Foundation Comes into its Own, As the Nonprofit Eyes Grand Plans it Weighs How Much Support Exists to Realize Them

©by Leo Adam Biga

Soon to appear in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Self-determination by any means necessary.

The notorious sentiment is by Malcolm X, whose incongruous beginnings were in this conservative, white-bread city. Not where you’d expect a revolutionary to originate. Then again, his narrative would be incomplete if he didn’t come from oppression.

Born Malcolm Little, his family escaped persecution here when he was a child. His incendiary intellect and enlightenment were forged on a transformative path from hustler to Muslim to militant to husband, father and humanist black power leader.

As it does annually, the Omaha-based Malcolm X Memorial Foundation commemorates his birthday May 17-19. Thursday features a special Verbal Gumbo spoken word open mic at 7 p.m. hosted by Felicia Webster and Michelle Troxclair at the House of Loom.

Things then move to the Malcolm X Center and birthsite. Friday presents by the acclaimed spoken word artist and author Basheer Jones, plus The Wordsmiths, at 7 p.m.

On Saturday the African Renaissance Festival unfolds noon to 5 p.m. with drummers, native attire, storytelling, face painting and Malcolm X reflections. Artifacts from the recently discovered Malcolm “Shorty” Jarvis collection of Malcolm X materials will be displayed. The late musician was a friend and criminal partner of Malcolm Little’s before the latter’s incarceration and conversion to Islam.

It’s a full weekend but hardly the kind of community-wide celebration, much less holiday, devoted to Martin Luther King Jr.

“I tell people, you may still not like Malcolm X, you may have a problem with a revolutionary. Martin was a revolutionary and maybe you came to love him. But I do want you to know brother Malcolm’s whole story and where he came from,” says MXMF president Sharif Liwaru.

“A big portion of what we do is about the legacy of Malcolm X. We go into communities, schools and other speaking environments and we educate people about Malcolm X, what he meant, what his impact was on society. Sometimes people walk away with a different level of respect for him. Sometimes they walk away having a better understanding.”

Using the tenets of Malcolm X, the foundation promotes civic engagement as a means foster social justice.

Nearly a half-century since Malcolm X’s 1965 assassination, he remains controversial. The Nebraska State Historical Society Commission has denied adding him to the Nebraska Hall of Fame despite petition campaigns nominating him. Few schools have curricula about the slain civil rights activist.

From its 1971 start MXMF has struggled overcoming the rhetoric around its namesake. The late activist Rowena Moore founded the grassroots nonprofit as a labor of love. She secured the North O lot where the razed Little home stood and where she once lived. Fueled by her dream to build a cultural-community center, MXMF acquired property around the birthplace. The site totals some 11 acres.

By the time she passed in 1998 the piecemeal effort had little to show save for a state historical marker. Later, a parking lot, walkway and plaza were added. Other than clearing the land of overgrowth and debris, the property was long on promise and short on fruition, awaiting funds to catch up with vision.

Without a building of its own, MXMF events were held alfresco on-site from spring through fall and at rotating venues in the winter. “We felt a little homeless,” says Liwaru. “We were very creative and did a whole lot without a building but we didn’t have a place to showcase and share that.” All those years of making do and staying the course have begun paying off. Hundreds of thousands of dollars in public-private grant monies have been awarded MXMF since 2009. Other support’s come from the Douglas County Visitors Improvement Fund, the Iowa West Foundation, the Sherwood Foundation, the Nebraska Arts Council and the Nebraska Humanities Council.

Most notably a $200,000 North Omaha Historical grant allowed MXMF to acquire its first permanent indoor facility, an adjacent former Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall at 3463 Evans Street, in 2010. Now renamed the Malcolm X Center, it hosts everything from lectures, films, plays, community forums, receptions and fundraisers to a weekly Zumba class to a twice monthly social-cultural-history class. Annual Juneteenth and Kwanzaa celebrations occur there.

Most notably a $200,000 North Omaha Historical grant allowed MXMF to acquire its first permanent indoor facility, an adjacent former Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall at 3463 Evans Street, in 2010. Now renamed the Malcolm X Center, it hosts everything from lectures, films, plays, community forums, receptions and fundraisers to a weekly Zumba class to a twice monthly social-cultural-history class. Annual Juneteenth and Kwanzaa celebrations occur there.MXMF conducts some longstanding programs, including Camp Akili, a residential summer leadership program for youth ages 14-19, and Harambee African Cultural Organization, an outreach initiative for citizens returning to society from prison.

The center is a community gathering spot and bridge to the wider community. Liwaru says it gives the birth site a “public face” and “front door” it lacked before, thus attracting more visitors. Besides hosting MXMF activities the center’s also used by outside groups. For example, Bannister’s Leadership Academy classes and Sudanese cultural events are held there.

“We’re very proud to be a community resource. It legitimizes us as an organization to have that space available. It makes a difference with the confidence of the volunteers involved.””

A recent site development that’s proved popular is the Shabazz Community Garden, where a summer garden youth program operates.

The surge of support is not by accident. The birthsite’s pegged as an anchor-magnet in North Omaha Revitalization Village plans and Liwaru says, “We definitely see ourselves as a viable part of it.” North Omaha Development Project director Ed Cochran, Douglas County Commissioner Chris Rodgers and Omaha City Councilman Ben Gray have helped steer resources its way.

Attitudes about Malcolm X have softened to the point even the prestigious Omaha Community Foundation awarded a $20,000 capacity building grant. Despite working on the margins, Liwaru says “investors could see our mission and work ethic and they supported that.”

Since obtaining its own facility, Liwaru says, “I find more people speaking as if our long-range plans are possible.” Those plans call for an amphitheater and a combined conference-cultural center.

For most of its life MXMF’s subsisted on small donations. When the building grant stipulated $50,000 in matching funds, says Liwaru, “”it was really the culmination of a lot of little gifts that made it happen.”

The all-volunteer organization depends on contributions of time, talent and treasure from rank-and-file supporters.

“We believe a little bit of money from a lot of people is beneficial,” says Liwaru. “Sometimes that meant we were probably working harder than the next organization that may be able to go to one or two people to get their funds, but it certainly makes us accountable to more people. We’re ultimately responsible to our community because we have so many community members contribute.

“Our organization belongs to the community. The people get the say.”

In tangible, brick-and-mortar terms, the foundation hasn’t come far in 40 years, but all things considered Liwaru’s pleased where it’s at.

“We’ve made a lot of progress. One of the things that makes me confident we’ve turned this corner is there’s still this strong commitment, there’s still passionate people involved.”

Veteran board members and community elders Marshall Taylor and Charles Parks Jr., among others, have carried the torch for decades. “They bring experience and wisdom,” says Liwaru. He adds, “We’ve added strong young people to our board like Kevin Lytle (aka Self Expression), and Lizabet Arellano, who bring a lot of new ideas and a passion for carrying out change in this urban environment.”

However, if MXMF is to become a major attraction a giant leap forward is necessary and Liwaru’s unsure if the support’s there right now.

“Everybody wants sustainability in terms of stable funding and revenue. We put out a lot of funding proposals at the end of last year. Few were approved. We got a lot of nos. Most funders don’t say why. We don’t know if it’s because they’re not wanting to be affiliated with Malcolm X or if it’s not understanding what we do as an organization or if they don’t think we can see projects through to the end.”

He can’t imagine it’s the latter, saying, “Anybody who knows us knows we’re persistent and that what we talk we follow through with.”

His gut tells him the organization still encounters patriarchal, political barriers.

“We always feel we have to come in proving ourselves. I always come in and explain we’re not a terrorist organization or a splinter cell. Most of what we get is a lot of encouragement but it’s a pat on the back and ‘I hope that you guys do really well with that’ versus, ‘I can help.’ I think one of the challenging things is we’re not sure what people think of us. There are many who aren’t sure which Malcolm we’re celebrating.

“If an organization is just completely not interested in covering anything related to Malcolm X it’d be nice to know. So the question from me to philanthropists out there is, ‘What do you think about the Malcolm X foundation and what we do? Do you see it as a worthy cause? What are we missing?”

Answers are important as MXMF is S100,000 away from finishing its planning phase and millions away from realizing the site’s full build-out. It could all take years. None of this seems to discourage MXMF stalwarts.

“We are willing to sacrifice and work diligently for however long it takes,” says Lizabet Arellano. Fellow young blood board member Kevin Lytle takes hope from the momentum he sees. “There’s more and more people at events and rallies and different things we do. People are finally starting to recognize and take pride in the fact Malcolm X was born here,” he says. “We have to start somewhere, and that’s a start. People know that we’re here and that we’re representing something beneficial to the community.”

Liwaru sees a future when major donors ouside Nebraska help the MXMF site grow into a regional, national, even international mecca for anyone interested in Malcolm X.

Besides a House of Loom cover charge, the weekend MXMF events are free. For details, visit http://www.malcolmxfoundation.org or the foundation’s Facebook page.

Related articles

- A Brief History of Omaha’s Civil Rights Struggle Distilled in Black and White By Photographer Rudy Smith (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Malcolm X bio doubts activist was served justice (cbsnews.com)

- Malcolm X artifacts unearthed: Police docs and more found among belongs of ‘Shorty’ Jarvis (thegrio.com)

- Blacks of Distinction II (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- A Synergy in North Omaha Harkens a New Arts-Culture District for the City (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Carolina Quezada leading rebound of Latino Center of the Midlands

The organizations that make a difference in a community of any size are legion and I am always struck by how little I know about the nonprofits impacting people’s lives in my own city. I often find myself assigned to do a story on such organizations and by the time I’m done I feel I have a little better grasp then I had before of what goes on day in and day out in organizations large and small that serve people’s social service and social justice needs. One such institution is the Latino Center of the Midlands, which I profile here along with its executive director Carolina Quezada, who came on board last year in the midst of a tough time for the former Chicano Awareness Center. She and I are happy to report the organization is back on track and that’s good news for the community it serves.

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in El Perico

Carolina Quezada took the reins of the Latino Center of the Midlands last August in the wake of its substance abuse program losing funding, executive director Rebecca Valdez resigning and the annual fund raiser being canceled. Despite the travails, Quezada found a resilient organization.

Overcoming obstacles has been par for the course since community organizers started the former Chicano Awareness Center in 1971 to address the needs of underserved peoples. Its story reminds her of the community initiatives she worked for in her native East Los Angeles. She never intended leaving Calif. until going to work for the Iowa West Foundation in 2009. Once here, she found similar challenges and opportunities as she did back home.

“I’ve come full circle. I see so much of what I encountered growing up in L.A. which is parents with very low levels of education wanting their kids to succeed, graduate high school and go to college but often no plan to get them there.,” she says.

“South Omaha is like this microcosm of East L.A. The moment I drove down 24th Street the first time I thought, This is like Whittier Blvd. I felt an instant connection. There’s so much overlap. This sense of close relationship with the grassroots, the sense of community, and how the organization has its beginnings in activism, in that voice of the community. It’s so indicative of how nonprofits in Latino communities have their base in the grassroots voice and in services and issues having to do with social justice.”

Forged as the center was in the ferment of unrest, she’s hardly surprised it’s persevered.

“I am pretty struck by how the agency continues to respond,. It’s always been responsive to what that emerging need is. I think it’s just an inherent part of its DNA.”

She acknowledges the center was rocked by instability in 2011.

“Currently we are in the process of trying to strengthen that stability. Last year was a very difficult year for the agency. There was a transition in leadership, there was funding lost. The agency was still operating but in a very low key way, and I give credit to the board members and staff in making sure the doors remained open. Their passion continues to drive what we do every day.

“One of our greatest core competencies is that love for community and that connection to our people. When people come through our doors they are greeted by people who look like them and speak their language. It’s their culture. I’m very proud the Latino Center keeps that piece very close to its heart.”

She says in this era of escalating costs and competition for scarcer resources, nonprofits like hers must be adaptable, collaborative and creative “to survive.

“There is much more a need to be strategic. It’s not just about being a charity. Now it’s about being an institution that takes on a lot more of the business model and looks at diversifying funding sources.”

In her view Nebraska offers some advantages.

“Because the economy is better here the environment for nonprofits is a little better. You have funders who are strong, engaged, committed and very informed. I think a lot of it has to do with the strength of their foundations and the culture of the Midwest. People really care about getting involved and building community.

“Last year was very tough. Not having the annual fundraiser really hurt the agency. But there’s been some renewed investment in the organization from funders. There is a very strong interest in collaborating with Latino Center of the Midlands from other organizations and funders and community leaders.”

Omaha’s come to expect the agency being there.

“Because of our 40-plus year history people know to come to us. We get a lot of walk-ins. We convene large groups of people here on a regular basis because of the wide array of classes we offer. We are still making an impact in parent engagement and basic adult education. We work with parents having a difficult time getting their kids to attend school on a regular basis.

“But we also deal with all sorts of other issues that come through our doors. We get requests for assistance with immigration, other legal issues, social services. We do referrals for all sorts of things. We’ve also started inviting partners to come offer their services here – WCA, OneWorld Community Health, UNMC’s Center for Health Disparities, Planned Parenthood. So we become a very attractive partner to other organizations that want to partner in the Latino community.

“We cannot do our work well if we’re not building strong partnerships with others.”

She says she and her board “are formulating some specific directions we want to take the organization in” with help from the Omaha Community Foundation‘s capacity building collaborative. “We have to look at those support networks for how we build capacity and we’re very fortunate to count on the support of the Community Foundation. We’re working with their consultants to look at our strategic initiatives, fund raising, board recruitment, programs and projects. We’re looking at where our impact has been and what the needs are in the community.”

She feels the center is well poised for the future.

“We realize we have a lot of work to do but there’s a lot of optimism and energy about where the agency could go.”

Best of all, the annual fund raiser returns July 23. “I’m so happy it’s going to be back,” says Quezada. Check for details on that and ongoing programs-services at http://www.latinocenterofthemidlands.org.

Related articles

- Evangelina “Gigi” Brignoni Immerses Herself in Community Affairs (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Jose and Linda Garcia Find a New Outlet for their Magnificent Obsession in the Mexican American Historical Society of the Midlands (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- “Paco” Proves You Can Come Home Again (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- African Presence in Spanish America Explored in Three Presentations (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- PBS WIll Air New Documentary On Latinos (huffingtonpost.com)

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

Rudy Smith was a lot of places where breaking news happened. That was his job as an Omaha World-Herald photojournalist. Early in his career he was there when riots broke out on the Near Northside, the largely African-American community he came from and lived in. He was there too when any number of civil rights events and figures came through town. Smith himself was active in social justice causes as a young man and sometimes the very events he covered he had an intimate connection with in his private life. The following story keys off an exhibition of his work from a few years ago that featured his civil rights-social protest photography from the 1960s. You’ll find more stories about Rudy, his wife Llana, and their daughter Quiana on this blog.

A brief history of Omaha’s civil rights struggle distilled in black and white by photographer Rudy Smith

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in The Reader (www.thereader.com)

Coursing down North 24th Street in his car one recent afternoon, Rudy Smith retraced the path of the 1969 summer riots that erupted on Omaha’s near northside. Smith was a young Omaha World-Herald photographer then.

The disturbance he was sent to cover was a reaction to pent up discontent among black residents. Earlier riots, in 1966 and 1968, set the stage. The flash point for the 1969 unrest was the fatal shooting of teenager Vivian Strong by Omaha police officer James Loder in the Logan Fontenelle Housing projects. As word of the incident spread, a crowd gathered and mob violence broke out.

Windows were broken and fires set in dozens of commercial buildings on and off Omaha’s 24th Street strip. The riot leapfrogged east to west, from 23rd to 24th Streets, and south to north, from Clark to Lake. Looting followed. Officials declared a state of martial law. Nebraska National Guardsmen were called in to help restore order. Some structures suffered minor damage but others went up entirely in flames, leaving only gutted shells whose charred remains smoldered for days.

Smith arrived at the scene of the breaking story with more than the usual journalistic curiosity. The politically aware African-American grew up in the black area ablaze around him. As an NAACP Youth and College Chapter leader, he’d toured the devastation of Watts, trained in nonviolent resistance and advocated for the formation of a black studies program at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he was a student activist. But this was different. This was home.

On the night of July 1 he found his community under siege by some of its own. The places torched belonged to people he knew. At the corner of 23rd and Clark he came upon a fire consuming the wood frame St. Paul Baptist Church, once the site of Paradise Baptist, where he’d worshiped. As he snapped pics with his Nikon 35 millimeter camera, a pair of white National Guard troops spotted him, rifles drawn. In the unfolding chaos, he said, the troopers discussed offing him and began to escort him at gun point to around the back before others intervened.

Just as he was “transformed” by the wreckage of Watts, his eyes were “opened” by the crucible of witnessing his beloved neighborhood going up in flames and then coming close to his own demise. Aspects of his maturation, disillusionment and spirituality are evident in his work. A photo depicts the illuminated church inferno in the background as firemen and guardsmen stand silhouetted in the foreground.

The stark black and white ultrachrome prints Smith made of this and other burning moments from Omaha’s civil rights struggle are displayed in the exhibition Freedom Journeynow through December 23 at Loves Jazz & Arts Center, 2512 North 24th Street. His photos of the incendiary riots and their bleak aftermath, of large marches and rallies, of vigilant Black Panthers, a fiery Ernie Chambers and a vibrant Robert F. Kennedy depict the city’s bumpy, still unfinished road to equality.

The Smith image promoting the exhibit is of a 1968 march down the center of North 24th. Omaha Star publisher and civil rights champion Mildred Brown is in the well-dressed contingent whose demeanor bears funereal solemnity and proud defiance. A man at the head of the procession holds aloft an American flag. For Smith, an image such as this one “portrays possibilities” in the “great solidarity among young, old, white, black, clergy, lay people, radicals and moderates” who marched as one,” he said. “They all represented Omaha or what potentially could be really good about Omaha. When I look at that I think, Why couldn’t the city of Omaha be like a march? All races, creeds, socioeconomic backgrounds together going in one direction for a common cause. I see all that in the picture.”

Images from the OWH archives and other sources reveal snatches of Omaha’s early civil rights experience, including actions by the Ministerial Alliance, Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties, De Porres Club, NAACP and Urban League. Polaroids by Pat Brown capture Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. on his only visit to Omaha, in 1958, for a conference. He’s seen relaxing at the Omaha home of Ed and Bertha Moore. Already a national figure as organizer of the Birmingham (Ala.) bus boycott and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he’s the image of an ambitious young man with much ahead of him. Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, Jr. joined him. Ten years later Smith photographed Robert F. Kennedy stumping for the 1968 Democratic presidential bid amid an adoring crowd at 24th and Erskine. Two weeks later RFK was shot and killed, joining MLK as a martyr for The Cause.

Omaha’s civil rights history is explored side by side with the nation’s in words and images that recreate the panels adorning the MLK Bridge on Omaha’s downtown riverfront. The exhibit is a powerful account of how Omaha was connected to and shaped by this Freedom Journey. How the demonstrations and sit-ins down south had their parallel here. So, too, the riots in places like Watts and Detroit.

Acts of arson and vandalism raged over four nights in Omaha the summer of ‘69. The monetary damage was high. The loss of hope higher. Glimpses of the fall out are seen in Smith’s images of damaged buildings like Ideal Hardware and Carter’s Cafe. On his recent drive-thru the riot’s path, he recited a long list of casualties — cleaners, grocery stores, gas stations, et cetera — on either side of 24th. Among the few unscathed spots was the Omaha Star, where Brown had a trio of Panthers, including David Poindexter, stand guard outside. Smith made a portrait of them in their berets, one, Eddie Bolden, cradling a rifle, a band of ammunition slung across his chest. “They served a valuable community service that night,” he said.

Most owners, black and white, never reopened there. Their handsome brick buildings had been home to businesses for decades. Their destruction left a physical and spiritual void. “It just kind of took the heart out of the community,” Smith said. “Nobody was going to come back here. I heard young people say so many times, ‘I can’t wait to get out of here.’ Many went away to college and never came back. That brain drain hurt. It took a toll on me watching that.”

Boarded-up ruins became a common site for blocks. For years, they stood as sad reminders of what had been lost. Only in the last decade did the city raze the last of these, often leaving only vacant lots and harsh memories in their place. “Some buildings stood like sentinels for years showing the devastation,” Smith said.

His portrait of Ernie Chambers shows an engaged leader who, in the post-riot wake, addresses a crowd begging to know, as Smith said, “Where do we go from here?’

Smith’s photos chart a community still searching for answers four decades later and provide a narrative for its scarred landscape. For him, documenting this history is all about answering questions about “the history of north Omaha and what really happened here. What was on these empty lots? Why are there no buildings there today? Who occupied them?” Minus this context, he said, “it’d be almost as if your history was whitewashed. If we’re left without our history, we perish and we’re doomed to repeat” past ills. “Those images challenge us. That was my whole purpose for shooting them…to challenge people, educate people so their history won’t be forgotten. I want these images to live beyond me to tell their own story, so that some day young people can be proud of what they see good out here because they know from whence it came.”

An in-progress oral history component of the exhibit will include Smith’s personal accounts of the civil rights struggle.

Related articles

- Carole Woods Harris Makes a Habit of Breaking Barriers for Black Women in Business and Politics (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Blacks of Distinction II (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- The Great Migration Comes Home: Deep South Exiles Living in Omaha Participated in the Movement Author Isabel Wilkerson Writes About in Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Making the Case for a Nebraska Black Sports Hall of Fame (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Part I of a Four-Part Q & A with Pulitzer-Winner Isabel Wilkerson On Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Part II of a Four-Part Series with Pulitzer-Winner Isabel Wilkerson, Author of ‘The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Part III of a Four-Part Q & A with Pulitzer-Winner Isabel Wilkerson on Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Part IV of a Four-Part Q & A with Pulitzer-Winner Isabel Wilkerson on Her Book, ‘The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration’ (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

- Photojournalist Nobuko Oyabu’s Own Journey of Recovery Sheds Light on Survivors of Rape and Sexual Abuse (leoadambiga.wordpress.com)

Abe Sass: A mensch for all seasons

The following profile I did on Abe Sass reminds me that extraordinary individuals are all around us. He’s married to a dynamo named Rivkah Sass, one of the most honored public librarians in the nation and because of her much feted work in that field she is obstensibly the star of this couple. But as I found out and as I hopefully succeed in sharing with readers like you Abe has a story worth knowing and celebrating too. He’s packed a lot of living into his life and because he’s pursued such a wide range of interests and experiences he’s brushed up against all sorts of historic people and places and events that I trust you will find as compelling as I did.

Abe Sass: A mensch for all seasons

©by Leo Adam Biga

Originally appeared in the Jewish Press

When your wife is a force of nature named Rivkah Sass, a recent national librarian of the year honoree and a much-in-demand public speaker, it could be easy to get overshadowed. The Omaha Public Library director’s dynamic personality can take over a room. Abe Sass doesn’t mind. In fact, he loves the attention Rivkah gets. You see, he’s not only her husband, but her biggest fan.

“Rivkah has an incredibly difficult job and I really believe she’s already changed the world in Omaha. She is committed,” he said.

There’s no real chance of him being lost in her limelight though. He’s every bit as accomplished as she and cuts a larger-than-life figure in his own right. A veteran psychiatric social worker, Sass has worked in several hospitals, he’s consulted school districts and he’s maintained his own private practice. No longer a full-time therapist, he volunteers his services to clients these days.

Sensitive and empathic as he may be, he’s no shrinking violet. He’s a charismatic presence at library activities and events with his warm smile, quick wit, hearty laugh and earthy demeanor. His six-foot-plus height and full beard help him stand out from the crowd, as does his animated demeanor, which flashes from dramatic whisper to basso profundo boom, all spiced with expletives and dollops of Yiddish.

This son of militant, immigrant garment workers in New York grew up a progressive thinker and activist. He was a rank-and-file soldier in the civil rights movement of the 1950s-1960s. He was at the historic march on Washington, D.C. in 1963 when Martin Luther King. Jr. articulated his dream for universal brotherhood. He was a member of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality. He took part in his share of demonstrations on behalf of equality and justice.

He’s never lost his social conscience or political fervor, either. He’s remained engaged wherever he roosts, from the tenements of lower Manhattan to the halls of academia to the psychiatric wards at hospitals in California, Washington and Oregon. In Omaha he’s a familiar figure wherever ideas are exchanged, whether a community forum or a book reading or an art opening.

He often conducts therapy sessions in the mid-town home he and Rivkah inhabit. The couple’s place is an expression of their passions. They’re both lovers of literature, art and discussion. They place high value on friends and family. They do puppetry. They tell stories. They champion the underdog. They support causes. They entertain guests. Fittingly, their home is adorned with books, paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, puppets, photographs of loved ones, mementos, keepsakes and campaign buttons emblazoned with liberal slogans, such as “Fight Racism” and “Swords and Plowshares.”

“Everything we do and have done is on our walls,” said Sass, gesturing to the overflow of objects about him in his living room.

He noted a small figurine of a black girl holding a book in one hand and a globe in the other, “which really fits who Rivkah is and who I am,” he said. The figurine is perched at the edge of a table atop which are also an old camera, a pair of cut-outs from artist Wanda Ewing’s black pin-up series and a button that reads “Black Power.” Sometimes there’s a button with a black hand, a brown hand and a white hand coming together that says “Let Us All Be Good Neighbors.” Taken together, he said, the display “is almost like a snapshot of a world that is and a world we could have. In many ways that represents to me where we need to go and, unfortunately, where we haven’t always been.”

Sass traces his humanist bent to his growing up poor in the Chelsea slums of New York City. He never knew his father, an artist, a presser, and Communist Party member who a year after Abe was born in 1938, went to Europe to try and rescue family only to be “swallowed up in the Holocaust.” His mother, Sylvia, endured “a miserable working life,” but sought much more for herself and her only child.

“All of her contemporaries were militant Jewish garment workers and wherever there was a rally there we were. I was just a kid, but everything they did made crystalline sense to me. It’s through her I met Pete Seeger and Paul Robeson. We would go to places where they were singing. We had a dear friend who was a wonderful militant woman. My mom and I would go with her to like a fraternal gathering place, where they would have speakers, singers. Seeger would come. Robeson would come. It was really cool. One of the major moments for me is when Robeson shook my hand and I felt, wow.”

He said he gained an awareness beyond his years “when we marched in the May Day Parade for working people and we’d get hit by rotten eggs and cabbages and comments like, ‘Go back to Russia’ or Dirty Commie.’” If all the protests he’s been a part of — from fair housing to sane nuclear policy to immigration reform– have taught him anything, he said, it’s that “there are people in this world that just don’t get it. I’m not a pessimist but I believe many people just don’t see there’s a big picture, and I believe one of the things we suffer from — all of us — is we only focus on ‘me.’ It’s dangerous…Unless we really see and feel connections we wind up with a perspective that’s very constricted and myopic.”

Action, not apathy. “We have to reach out and do something for people who need an assist up. It’s like that powerful saying, When they came for him, I didn’t say anything, when they came for her I didn’t say anything, and then when they came for me, nobody said anything. It’s still the same. It hasn’t changed,” he said.

The “cruddy” area he came from offered some valuable lessons on human relations and social conditions. Being the only Jewish kid on his block gave him a sense for what minority really mean.

“We lived in a terrible apartment building on West 18th Street,” now the trendy art neighborhood of New York, he said. “It was a little, dinky three-room apartment. I lived there through my 20s. It was tense and tight and loud and crazy. When you’re Jewish and you grow up in an Irish-Catholic neighborhood you’re an oddball by definition. I was more of an oddball because my aura was a softer aura and the softness not only came from enjoying the sanctuary of the orthodox synagogue I grew up in, but also” from being a reader and an art lover among street kids.

“The kids I was desperately trying to fit into I really had a hard time with, because they were busy kicking other people’s asses and that really was not something I felt comfortable with. And when it came to like stick ball and football and all that shit, nuh-uh, it was like, ‘Oh, get out of here, Abe.’ I was totally useless.”

To survive, he had to find his own schtick.

“Everybody had their thing on the block. You gotta have something to get a rep, OK? My rep was on Sunday nights, when we’d gather on a stoop and I would tell stories to these same kids…just make ‘em up out of my head…and I had them, because I could weave a tale, and I loved it. I shined in that moment.”

At PS 11 Elementary School and at Charles Evans Hughes High School he mixed with Jews, Irish, Italians, African-Americans, Greeks, Asians and practically every other nationality-ethnicity. “It was a potpourri of people,” he said. “You talk about a spectrum, it was all there.”

He fondly recalls the summer camps for “underprivileged children” he attended, and later was a counselor at. They further exposed him to a multi-cultural stew.

“My best friends were always Puerto Rican kids, black kids, Asian kids. I used to drive my poor mother crazy because every summer I’d come home from camp talking like I’m a kid from Harlem. She would say, ‘What kind of talking is this?’”

Counselors at camp, he said, “were usually (university) psychology or social work students. They were there because they had a desire to be there to help kids. Every summer I looked forward to it. When I became a counselor it was a joy for me to help a kid who was going through shit clear out and get away from it and say, Bye-bye shit, I don’t need you anymore. I knew I wanted to do this.”

He credits a camp director with giving him sound career advice. At the time, Sass was weighing what to do after high school. Though he felt called to be a teacher-counselor, he felt stymied by his lack of funds.

“He said, ‘Abe, you’ve got it. If you want it, go for it. The money will show itself. Don’t hold back ‘cause you don’t have the money.’ I totally trusted him and he was right. He was absolutely right. I was lucky enough to go to City College, which didn’t have tuition, and then Columbia University gave me a full tuition scholarship.”

Going from the lower Manhattan ghetto to elite Columbia was quite a leap.

“I was a lucky guy. I was just so happy. I was in fat cat city. That was the best training I could of had and it has helped me right through till now. There just happened to be a confluence of forces that brought these dynamite people to Columbia during those years.”

For him, the core of where the therapeutic focus needs to be was brought home by a case study of a subject with “a mouthful of rotten teeth.” Sass posited, “What would it be like walking around day after day with a pain in your head? Is that going to throw you off balance? Yeah. So, we were like back to Abraham Maslow. Basics, man. I have met a lot of people who have spun their wheels with a lot of therapists and they still haven’t dealt with the basics, and it’s sad.”

University life also fed his activist and culturist sensibilities. The Cold War was at its peak. Vietnam was just getting hot. The civil rights movement already underway.

“In college I hung out with The Beats and we were all counterculture,” he said. “We didn’t see the way it was going as the way it needed to go. We felt there was a world out there of creativity, art, exciting ideas and some of that meant taking a stand and a lot of that meant looking at the fact there are a lot of people who are not free, who have less opportunities than we do. So I started into that and my mother, of course, was very proud of that.”

He participated in sit-ins, some to show support for the activists down south “getting their heads plunked.” He was tempted to be a freedom fighter himself in Jim Crow country, and once “I was all but on my way,” before something came up.

He and a friend did go to the nation’s capital for the famous MLK-led ‘63 mass March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

“We both felt this would be an important thing to do,” he said. “Several of our friends were going…We drove there. It was wild because all these cars were on the road and people were waving at each other. I mean, we all knew where we were going. It was an amazing experience.

“We first gathered at the Washington Monument, where there were singers and all kinds of speakers, and then we walked to the Lincoln Memorial. It was a hot day and…every once in awhile somebody would pass out, but we were all so tight the person would be lifted up with hands and gently moved to the outer perimeter, where medics and assundry volunteers were set-up. It was like pre-mosh pit.”

The impact of the huge, unified crowd, estimated at 250,000, and of the speakers, capped by King’s rousing “I Have a Dream” oration, was “very, very powerful.”

Last month Abe accompanied Rivkah to D.C. for the American Library Association Conference. He retraced the march he made as part of that great procession 44 years earlier. By the end, he had a Mr. Sass Goes to Washington experience.

“I wound up one late afternoon walking the exact same path. It was hot. I went straight to the Washington Monument. It was very spiritual. Half-way between it and the Lincoln Memorial there’s ‘a Kodak moment’ spot where there’s a little display with a photo of the wading pool that day in ‘63 with all those people.

“I continued on to the Lincoln Memorial. I went up where his Gettysburg Address is engraved on one wall and I don’t know what possessed me, but I started saying it out loud. I know it pretty much by heart. And this group of tourists came over and we’re all looking at it together as I’m reading it out loud and they’re like, right there with me, and I just kept on going.”

He’d had some practice with the speech. Back at PS 11 he was selected to portray Lincoln for a school assembly. On his nostalgia trip back to D.C. all those years later, he didn’t stop with “Four Score and Seven Years Ago…”

“When I was done, I turned and I walked to the wall where his second inaugural address is engraved, and this same group of people followed, and I read that out loud. They were right there with me again. The greatest thing was I called our daughter and I told her where I was and I told her how much I loved her.”

Sass said when his daughter Ilana was a young girl she’d have friends over the house and invariably get down from a shelf the book, The Negro Since Emancipation. The back cover has an image of demonstrators in the ‘63 march and there’s the young Sass towering above the throng. His daughter would proudly proclaim to her pals, “That’s my dad.” “It was very special,” Sass said.

The melting pot experiences Sass had the first half of his life gave him an enriched perspective he carries with him to this day.

“I love my roots, I really do. I treasure them. I feel really good about having been introduced to so many wonderful ways of thinking. The weird thing is, even though there were many aspects of it that were very, very uncomfortable, I’m so glad it happened that way. Because thinking about who I am now I really feel like I viscerally can feel, for example, what people in parts of Omaha feel when they’re talking about the kind of shitty conditions they’re living in and have been living in for years and there’s no f___ing excuse for it. There really isn’t.”

Not long after moving with Rivkah to Omaha about four years ago, he attended a north Omaha town hall meeting at which Mayor Mike Fahey and his cabinet responded to issues confronting the inner city. Sass said an older woman pointedly asked how it is the cracked streets and backed-up sewers area residents like her knew as kids are still in disrepair decades later, and, how come residents out west don’t have these problems. No real answers were forthcoming. The gap between black Omaha and white suburbia apparent in the void.

“It’s hard to even try to say what I was feeling as I sat there,” Sass said. “Here we are in 2007 and there’s all this stuff about segregation…The struggle goes on, and you can’t be blind to it. You really can’t be blind to it.”

The poor, old working-class woman kvetching about inequality reminded him of his mother, each asymbol of the proletariat struggling to get by.

“She would go the shop and sit behind a sewing machine all day long busting her chops,” he said of his mom. “And she worked and worked and worked, and when she was 62-years-old she was wasted. It’s very, very sad.”

He was reminded, too, of when he went to California in the mid-’60s, fresh from Columbia, and found an unfriendly climate. En route, he stopped for gas at a roadside filling station, where, he said, “this guy and I got to talking.” When Sass mentioned he was heading for Napa, he recalled “the man saying, ‘Oh, you’re going to love it, there are no niggers in Napa.’ Holy shit, I just about fell down. Could not believe it. That’s one of the things that propelled me to join CORE.”

Once there he was dismayed to discover a form of red-lining being practiced whereby “realtors in the area were knocking on doors and saying, ‘There’s a black family moving in down the street from you — you might want to sell your house now because its value is going to diminish.’ That was going on when I got there,” he said, “so I got involved in the opposite campaign.”

He threw himself into resisting city plans for razing an established residential neighborhood built during the war for shipyards workers and their families and building high-priced condos in its place.

“A lot of the people who lived there were going to get displaced,” he said. “We (CORE) got involved in a big campaign to stop that. We had rallies, marches.

“Also, we started a freedom school in a storefront and kids would come in and we’d help them with whatever their issue was. Helping people connect with their community is very powerful.”

Wherever he saw discrimination he tried meeting it head-on.

“Not too long after I got to Napa I went for lunch with my friend Frank, a black psychiatrist. We were in this local-yokel place. We ordered and we waited. People came in after us and were served while we’re still sitting there. We asked what’s going on and the wait staff said, ‘We’re out of what you ordered.’ So we said, How about such and such? And they said, ‘We’re out of anything you’ll order.’ We really got pissed off and like two days later a shit load of us showed up, black as black can be, man. I was one of the few white guys in the group.

“We were sitting there and we weren’t moving until we got served. We said, ‘If you don’t have it today, we’re coming back tomorrow.’ They just shit in their pants. And the name of the game was they changed their policy. But not because they’re kind-hearted. It’s the pocket book. It’s money.”

He noted another incident that happened when he lived in an apartment complex. Black friends of his from CORE came over and went for a swim in the pool. When they jumped in, the whites jumped out. The next day, Sass said, he found his car’s tires slashed. He had to insist the police treat the matter as a hate crime.

“It’s sad and it’s funny and crazy and pathetic and angry…all that stuff,” he said.

He knows how hard it is for people to change attitudes and behaviors. He’s spent the better part of his life helping people try to do just that. “When somebody is going through a terrible emotional crisis my job is to help them create a revolution within themselves because what they’ve been doing is not working for them. If the revolution is successful they move on and it’s like a different world.”

Abe and Rivkah have endured their own crises, including the loss of a son.